Abstract

Rural agrarian societies, like Bangladesh, rely substantially on women as primary contributors to crop production. Their involvement covers a broad spectrum, from the first stage of seed sowing to the ultimate phase of marketing agricultural products. Information and communication technology (ICT) in agriculture could be a transformative tool for women’s agricultural involvement. Despite the inherent challenges associated with ICT adoption, it has emerged as an effective catalyst for improving the livelihoods of rural women in Bangladesh. This study investigates the impacts of ICT on the livelihoods of rural women. This study concurrently addresses the challenges that infringe upon its sustainability. The study was conducted within Oxfam Bangladesh’s ICT interventions implemented upon the women farmers in Dimla Upazila, Nilphamari, Bangladesh. We employed a mixed-methods research approach to examine the multilayered impacts of ICT on women farmers’ livelihoods. Our findings indicate that ICT support has improved the livelihoods of rural women through a comprehensive capital-building process encompassing human capital, social capital, financial capital, physical capital, and political capital, facilitated by creating an enabling environment. The study also unfolded several challenges stemming from aspects of ICT integration, including the disappearance of indigenous agroecological knowledge and the disruption of traditional multicropping practices. In light of the study’s outcomes, a key recommendation emerges, emphasizing the importance of integrating indigenous agroecological knowledge in the widescale implementation of ICT initiatives. Acknowledging and accommodating indigenous knowledge can enhance the sustainability of ICT-driven livelihood enhancements for rural women in Bangladesh.

1. Introduction

Women are widely acknowledged as a foundation of the rural economic framework, constituting an equal share of global agricultural producers [1] They concurrently fulfill multidimensional roles including familial nurturing, elderly care, cooking responsibilities, household management, and sociopolitical governance despite their substantial and dedicated involvement in agricultural pursuits [2,3,4]. In the contemporary global agrarian landscape, women constitute a significant workforce, accounting for 43 percent of the total labor force [5]. Within the distinct context of Bangladesh’s national economy, the agricultural sector holds a prominent and crucial role, akin to other developing nations. Delineated as one of the central economic strongholds, this sector contributes approximately 23 percent to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) [6]. Pertinently, women constitute an indispensable cohort within the rural agricultural labor force of the nation, and the involvement of women in rural areas of Bangladesh in the agriculture sector has increased from 54% in 2013 to 60% in 2017 [7].

Within the domain of agriculture, like many other sectors, the primacy of information has become increasingly pronounced, assuming a vital role in the operational paradigm [8]. As a result, ICT has a significant impact on the growth of agriculture [9], enabling farmers to acclimatize knowledge and information, thus constituting a central axis that empowers their responsiveness to emergent prospects capable of enhancing agricultural productivity [10]. In this context, information communication technologies (ICTs) have emerged as a vanguard, holding considerable promise for catalyzing the developmental trajectory of countries in the Global South [11]. In the specific case of Bangladesh, ICT has emerged as a transformative tool that has the potential to enhance various dimensions of women’s participation in agriculture and to enhance sustainable livelihoods [12]. Primarily, ICT platforms have facilitated access to crucial agricultural information and knowledge resources for women farmers in Bangladesh. Through mobile applications, online platforms, and SMS services, women farmers are now equipped with real-time data about weather forecasts and pest management [13].

However, historically, the gendered exclusion of women from the information and communication technology (ICT) domain has been conspicuous. This exclusion has manifested itself as ICT becoming predominantly male-centered, characterized by disparities in accessibility and availability, often intertwined with economic power dynamics. Simultaneously, a pronounced gender disparity persists in access to essential resources such as land, energy, technology, loans, pesticides, and fertilizers. Moreover, women confront significant hurdles in accessing training, information, public services, social protection, and markets, as highlighted by García [14]. A recent investigation conducted by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) established a tangible correlation between conspicuous gender gaps in mobile phone ownership and the limited adoption of the Internet among females. Only 19% of women in least developed countries (LDCs) used the Internet in 2020, compared to 86 percent in the developed world [15]. Exemplifying this dynamic, the GSMA’s Mobile Gender Gap Report for the year 2023 underscores the mobile phone ownership gender divide in Bangladesh, revealing a substantial dichotomy. Remarkably, approximately 67 percent of adult women in Bangladesh own mobile phones; however, a mere 21 percent engage with the Internet. This stark incongruity designates Bangladesh as a prominent epicenter of the mobile ownership gender gap phenomenon, corroborating its standing as one of the most pronounced cases globally [16]. The root of this phenomenon can be traced to a Marxist perspective, which emphasizes the gender-based division of labor and how it perpetuates gender disparities. This issue is further exacerbated by the deeply ingrained cultural perception that associates technology with masculinity. Within this societal framework, technology reflects and reinforces the prevalent male dominance [17,18,19].

In spite of having these challenges, agriculture has emerged as a potent avenue for empowering women, as explicated by Kabeer [20], as the expansion of women’s capabilities in three crucial dimensions: resources, agency, and wellbeing outcomes. However, the journey toward empowerment for rural women in Bangladesh, particularly those living in poverty, is fraught with multifaceted challenges. These challenges include poverty, inequality, inadequate infrastructure, restricted access to education and information, and deeply rooted social factors, prominently the patriarchal structure. Nevertheless, the introduction of information and communication technology (ICT) has catalyzed a significant transformation in the lives of rural Bangladeshi women farmers. Among the transformative elements, the accessibility of smartphones stands out as a potent tool that has improved their access to vital information and communication opportunities. This accessibility has, in turn, mitigated vulnerabilities and enhanced livelihood prospects. ICT has also facilitated improved access to agricultural extension services and local markets, ultimately empowering women and advancing their agency, as elucidated by Biswas et al. [12].

The recognition of information and communication technology’s (ICT’s) capacity to enhance agricultural productivity has garnered extensive acknowledgment within scholarly discourse. The revitalizing potential of information and communication technology (ICT) within agriculture is undeniable, as evidenced by its far-reaching impact on the sustainable livelihoods of women farmers [12]. This happened with the deployment of ICT for augmenting the capabilities, knowledge, and skills of women farmers, collectively referred to as human capital. These investments in human capital have yielded substantial dividends, resulting in the development of social, financial, physical, and political capital. Consequently, women’s roles have transcended the confines of their households, bestowing upon them significant importance in the broader societal context. Further, the emergence of digital platforms has facilitated unprecedented knowledge exchange and networking opportunities among experts from diverse regions [21]. While fostering innovation, this global connectivity simultaneously introduces challenges that influence local and indigenous knowledge, particularly agroecological knowledge dynamics. However, this fundamental imperative requires a thorough investigation of the predominant ICT adoption by women farmers. Unfortunately, these concerns often receive limited attention in scholarly domains. Based upon these concerns, this study aimed to identify the impacts of ICT on the livelihoods of women farmers and uncover the challenges impeding their sustainability. To achieve these objectives, we conducted a study within the context of ICT users at South Kharibari village in Dimla Upazila. This study employed a mixed research approach, encompassing both qualitative and quantitative methods, to comprehensively explore the nuances of ICT usage for agricultural purposes among women farmers.

This study emphasizes the importance of considering invaluable insights derived from indigenous and local agricultural knowledge to successfully integrate ICT to improve women’s livelihoods. It seeks to achieve a harmonious synergy between modern technological interventions and the time-tested wisdom embedded within traditional knowledge systems. Such an approach could enhance the efficacy and sustainability of ICT-driven agricultural advancements, fostering a more holistic and contextually relevant renovation.

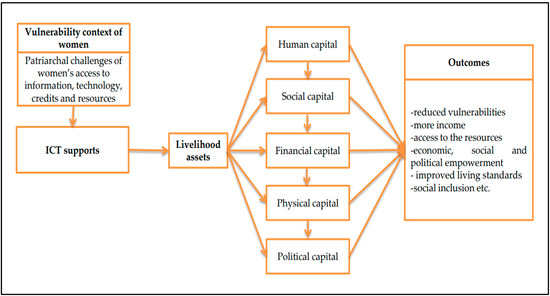

Conceptual Framework for Understanding the Impacts of ICT on Women’s Livelihoods

The adoption of the sustainable livelihood framework provides a complete analytical foundation for this study. The concept of “sustainable rural livelihoods” has progressively assumed a central role in the discourse on rural development, poverty alleviation, and environmental stewardship. Livelihoods, within this framework, represent a composite of capabilities, assets—encompassing both tangible and intangible elements—and activities requisite for sustaining one’s means of subsistence. Importantly, a livelihood attains sustainability when it exhibits the capacity to effectively endure and improve from various stressors and shocks while concurrently preserving or enhancing its inherent capabilities and assets, all without compromising the integrity of the natural resource base [22,23]. Those individuals who find themselves unable to effectively cope with short-term changes or adapt to longer-term shifts in livelihood strategies inevitably fall into the category of vulnerability and are less likely to realize sustainable livelihoods [22]. Within the specific context of this study, women emerge as a vulnerable demographic concerning access to information and communication technology (ICT) and other essential resources. They encounter formidable obstacles when seeking access to training, information, public services, social protection, and markets. This vulnerability is intricately tied to the existence of structural barriers, prominently exemplified by the entrenched patriarchal social structure within society (see [14,17]).

The emergence of information and communication technology (ICT) stands out as a transformative catalyst, significantly augmenting women’s capacity to engage in various livelihood strategies (see Figure 1). This ability to pursue diverse livelihood strategies is contingent upon the possession of foundational material and social assets. Drawing upon an economic analogy, these resources underpin livelihoods, functioning as the “capital” base from which an array of productive streams emanate, thereby constructing and sustaining livelihoods.

Figure 1.

Sustainable Livelihood Framework modified from DFID (2001) [24].

Human capital encompasses various capacities that enable individuals to pursue diverse livelihood strategies and contribute to community objectives [24]. This includes a spectrum of attributes such as skills, knowledge, labor capabilities, and physical health, all of which are essential for the effective pursuit of livelihood strategies [22].

Social capital revolves around the concept of social resources, including networks, social ties, affiliations, and associations that individuals can leverage when engaged in livelihood strategies that require coordinated actions [22].

Financial capital constitutes various economic assets, including cash, credit/debt, savings, and other financial resources, all of which are indispensable for the pursuit of livelihood strategies [22].

Physical capital includes tangible goods and objects that support individuals’ livelihoods, including vehicles, homes, tools, and work-related assets [25].

Political capital serves as a testament to women’s empowerment, highlighting their heightened awareness of rights, roles, and active participation in addressing societal issues and injustices. This dimension emphasizes their engagement in challenging detrimental customs and combating violence against women, as well as their increased involvement in decision-making processes, both within the family unit and at the societal level.

However, the Sustainable Livelihood Framework provides a nuanced and comprehensive understanding of how ICT adoption empowers women within the agricultural sector, encompassing personal and social transformations, economic gains, and political empowerment. This framework places women as active agents of change, contributing to the development of sustainable rural livelihoods while transcending the barriers imposed by traditional gender norms and structural inequalities (see Figure 1).

2. Materials and Methods

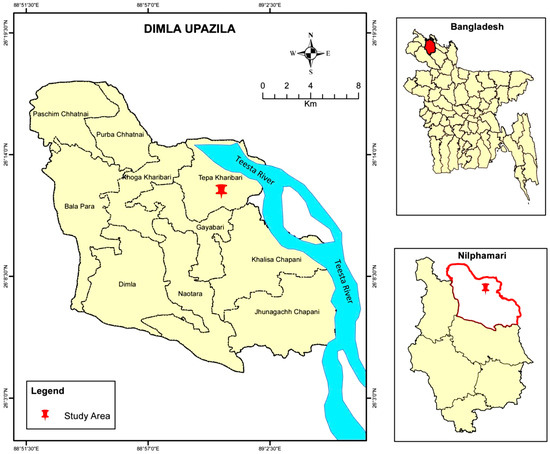

2.1. Study Area

This research was undertaken within the South Khoribari village, located in the Dimla upazila of Nilphamari District in Northwestern Bangladesh (see Figure 2). The study site exemplifies the characteristics of a prototypical char land, a term denoting “sandbars that emerge as islands within the river channel or as attached land to the riverbanks” [26,27]. The population of this area totals approximately 3500 individuals, with a substantial proportion of the villagers actively engaged in agricultural pursuits [27]. Noteworthy is the direct and active participation of women in agricultural pursuits, alongside their concurrent management of household responsibilities. Additionally, in select households, women assume the complete mantle of agricultural responsibilities, while male members of these families are occupied in diverse occupational pursuits in other regions of the country.

Figure 2.

Location map of study area (South Khoribari village under Tepa Kharibari union, located in the Dimla upazila of Nilphamari District in Northwestern Bangladesh).

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The research was conducted among the beneficiaries of Oxfam’s PROTIC (Participatory Research and Ownership with Technology, Information and Change) project employing a mixed research approach, referring to the use of two or more methods in a single research, including qualitative and quantitative approaches to increase the accuracy and level of confidence [28,29,30,31] at South Kharibari village of Dimla upazila located on the Teesta river basin of Northwestern Bangladesh. Data were collected from women farmers provided with ICT equipment, including smartphones, Internet, and online supports through household surveys and focus group discussion (FGD) from October 2019 to January 2020.

In 2015, a targeted intervention involving the provisioning of ICT support was implemented for a cohort of 100 woman-headed households by Oxfam Bangladesh in collaboration with Monash University. Oxfam provided mobile phones (smartphones), monthly Internet services (package), and training to the women who were known as animators. The selection of animators was involved in satisfying a set of three specific criteria. These criteria included (1) the status of heading a family by a female, (2) the presence of a disability within the individual, and (3) a correspondence with the prevailing economic profile observed within the broader demographic composition of the village populace [13,27]. These women farmers were furnished with ICT resources to facilitate their access to essential agricultural information encompassing aspects such as crop cultivation, water management, and weather forecasts. The dissemination of this information was facilitated through diverse communication channels, including mobile phone short message service (SMS), outbound dial (OBD), interactive voice response (IVR), applications, and call center services specializing in agriculture and agrometeorology, incorporating early warning systems into their operational framework. The adoption of these services empowered women farmers to proactively mitigate potential losses and detriments incurred by unforeseen meteorological events such as floods, dense fog, abrupt rainfall, crop afflictions, and pest incursions, thus enhancing their adaptive capacities and bolstering agricultural productivity [13].

In order to comprehensively evaluate the impacts of information and communication technology (ICT) on the livelihoods of women farmers, a systematic approach was adopted to gather insights acquired from five years of ICT usage. This process encompassed several vital stages, commencing with a stakeholders’ consultation involving women farmers who had benefited from ICT support. This initial consultation served a dual purpose: firstly, to obtain a preliminary understanding of the effects of ICT on rural women’s livelihoods; secondly, to refine and finalize the subsequent household survey questionnaire. Following the stakeholders’ consultation, a semistructured questionnaire was designed to address the research questions and was subsequently utilized in a comprehensive household survey involving 42 women farmers. The data collected from the household survey formed a foundational layer upon which additional validation and context enrichment were achieved through three distinct focus group discussions (FGDs). These FGDs were instrumental in corroborating the insights from the household survey and delving into the multifaceted dimensions of changes that transpired over the preceding five years. Moreover, the FGDs served an additional critical purpose of unearthing the diverse challenges of integrating ICT in rural areas. Each FGD, consisting of 12 to 15 women participants, was conducted under the guidance of a skilled facilitator, accompanied by an assistant responsible for accurately recording the discussions. The selection of respondents for both the household surveys and FGDs was deliberately differentiated, contributing to a holistic and well-rounded perspective on the subject matter.

The data obtained from the focus group discussions (FGDs) were precisely documented through recordings and comprehensive notes, and underwent subsequent transcription into textual format. These textual data were thoroughly analyzed through traditional qualitative data analysis software, specifically N-Vivo, a recognized tool in this field, hailing from Melbourne, Australia. This analytical process was grounded in an inductive approach, enabling the systematic identification and extraction of noteworthy emergent themes inherent within the FGD data. Concurrently, the data stemming from the household surveys followed a distinct analytical trajectory. Leveraging computer software, specifically Microsoft Excel, the data from the household surveys underwent thorough analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Implications of ICT on Livelihoods

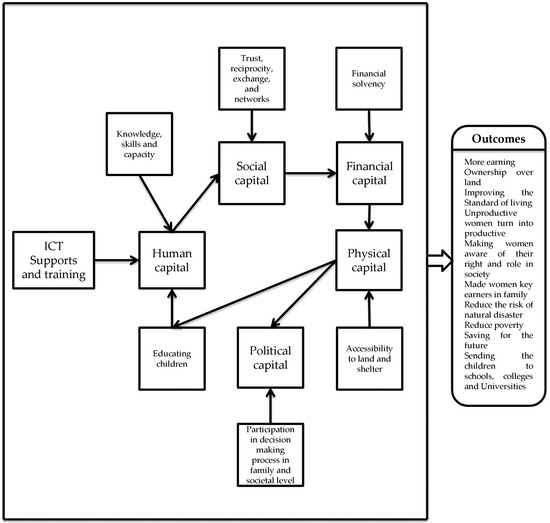

The findings of our study demonstrate that the integration of ICT, such as smartphones, Internet services, and mobile applications, along with the provision of relevant training programs, enhanced the skills, knowledge, and capabilities in the field of agriculture. This implies a positive impact on the development of human capital in this agriculture. The influence of human capital extends to other dimensions, including social, financial, physical, and political capital (see Figure 3 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Implications of ICT in the livelihoods of women farmers.

Table 1.

Impacts of ICT among women farmers.

3.1.1. Human Capital

The study revealed that within the domain of women involved in agricultural pursuits, the deliberate utilization of information and communication technology (ICT) tools, specifically smartphones, in combination with the provision of relevant training on their usage and access to the Internet, has exhibited a vital capacity to enhance knowledge and competencies which is referred to as human capital [32]. The utilization of Internet resources has emerged as a transforming factor for women, serving as a crucial catalyst for empowerment. Engaging in capacity-building programs and seminars focused on successfully deploying information and communication technology (ICT) has facilitated persons in improving their knowledge and understanding of agriculture, resulting in a deeper comprehension of the agricultural domain.

The reliance on diverse technological avenues, including social media platforms, mobile applications, and call centers, enhances women’s knowledge and skills in agricultural settings. ICT has concomitantly bolstered women’s self-confidence, amplifying their decision-making processes and communication proficiencies.

One FGD respondent expressed her transformative experience, noting,

“I couldn’t move, the touch of ICT equipment (smartphone) taught me to move, I couldn’t say, the use of ICT gave me language and I couldn’t see, ICT gave me sight. The use of ICT has changed my life.”

In the same way, the household data show that 100% of the respondents claimed that the ICT support and its training have improved their knowledge and skills in the agricultural sector and they can now effectively utilize them in this sector.

3.1.2. Social Capital

The field data revealed that the advancement of the utilization of ICT has exerted a transformative influence on societal connectivity, particularly among ICT users. During the emerging stages of the project, individuals sought assistance from nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to access ICT support. However, their current approach utilizes government-sponsored applications such as Krishoker Janala (Govt. intervened app supporting the farmers) to access pertinent information to address agrarian challenges. Adopting ICT equipment has yielded positive outcomes for women, leading to augmented self-confidence, heightened productivity, heightened interaction with governmental and nongovernmental entities (GOs and NGOs), and enriched domain knowledge in agroproduction. Additionally, this cohort actively disseminates their accrued knowledge to fellow women farmers within their local community. These interwoven networks, structured organizational involvements, relationships rooted in trust, and reciprocal exchanges established by ICT interventions are referred to as social capital [32]. Reflecting upon this transformation, FGD respondents commented,

“Earlier we got information from the NGO supported services but now we get them using GO oriented services.” They further elaborated, “Not only we alone, our neighbors are also getting helped to solve the problem in cultivation, rearing livestock and farming fishes by our acquired knowledge.”

Similarly to the FGD respondents, 34 respondents of the household survey expressed that notable improvements in cooperation, trust, and reciprocal relationships among neighboring individuals are visible in the community. These findings underscore instances where neighboring farmers, when confronted with challenges in their agricultural practices, proactively extend assistance to ameliorate the difficulties faced by their neighbors. Furthermore, in the realm of information and communication technology (ICT), users who receive preemptive notifications regarding impending food shortages or other extreme natural events through diverse applications exhibit a discernible tendency to disseminate this crucial information to their neighboring peers selectively. This dissemination practice indicates an augmented sense of trust nurtured within the village community, cultivating a more resilient social fabric.

3.1.3. Financial Capital

The adeptness demonstrated by women in employing Internet-enabled cell phones has yielded tangible advantages in mitigating the risks of natural adversities, such as floods and excessive rain during the rainy season and dense fog in winter, as well as the detrimental impact of pests on crop production. The cultivation of knowledge pertaining to these challenges has culminated in augmented agricultural output, facilitated by insights into impending natural disasters, judicious employment of insecticides and fertilizers, tailored problem-solving strategies for crop cultivation, and the adept management of crops through smartphone applications. This augmented productivity has been directly mirrored in increased income levels and financial comforts. FGD respondents illustrate this transformative change, recounting,

“Few years back, we faced a great financial loss due to the less production of maize and other money making crops because of the harmful insects. Potatoes were damaged due to fog. We did not know what to do. We faced a great financial crisis due to the damages of crops by floods, rains, fogs and insect’s attack. But now we are aware of the insects and weather due to digital apps and early warning systems. We are being informed through SMS and phone calls in some cases. We are producing double crops as we produced before.”

Financial losses resulting from natural events have been minimized with the supports of ICT equipment that brought economic solvency. On the other hand, as this area is on the riverbank and in an erosion-prone area, farmers, particularly women farmers, did not receive any financial loans either from microfinance organizations or financial organization, because those organizations considered the women farmers economically vulnerable and they might fail to repay the loans. As women are financially empowered, which augments the financial prominence of women within both familial and societal spheres trust between village women and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), this has streamlined access to microfinance institutions and loans. This economic gain from minimizing the crop losses of extreme natural events and microfinance institutions is termed as financial capital [33].

Our household survey data revealed a similar finding to that obtained through FGDs. A total of 34 respondents claimed that the use of ICT reduces the chances of crop destruction or damage, resulting in financial gains.

3.1.4. Physical Capital

Physical capital embodies basic infrastructures including sanitation, energy, transport, communications, housing, and the means and equipment of production [34]. In the context of cultivation and agroproduction, land constitutes an indispensable prerequisite. However, a significant proportion of women farmers lacked personal landholdings for cultivation prior to their involvement in the project. These land deficiencies stemmed from factors such as river erosion and financial constraints, which hindered their ability to procure land.

One of the FGD respondents appropriately encapsulates this situation, stating,

“I have nothing of my own except my house. Even my husband cultivated crops in the land leased from other persons. However, crop production often faced setbacks due to adverse weather, pest infestations, and flooding.”

As financial empowerment gradually takes root after the usage of ICT, there emerges a burgeoning interest among women to acquire land holdings. Utilizing their newfound financial prominence, women are investing in the purchase of agricultural land, while concurrently channeling surplus income into the construction of residences for improved living conditions. An FGD respondent presented testimony,

“Eight years ago, my land was swept away by river erosion, leaving me without any personal property. Since then, I have managed to acquire a new plot of land using my hard-earned income, which I had saved from the proceeds of my agricultural activities.”

Notably, by mitigating vulnerabilities to crop damage and destruction brought about by natural forces, the strategic integration of information and communication technology (ICT) has engendered a tangible enhancement in the financial stability of women farmers. This enhanced stability, in turn, has prompted a notable proportion, precisely 25 women, to proactively engage in savings practices, thereby paving the way for more secure economic trajectories. Utilizing their savings, these economically empowered women have made major investments in acquiring land for both housing and crop cultivation purposes (either purchased or leased lands). Moreover, they spent money saved for renting mercenaries to accelerate their agricultural activities. These salient developments are categorized as examples of physical capital [34,35].

3.1.5. Political Capital

Engagement with diverse government organizations (GOs) and nongovernment organizations (NGOs) has facilitated a nuanced understanding among women regarding their familial and societal roles, rights, and obligations. This newfound awareness has translated into active participation in remedying injustices and eradicating violence targeting women and girls, both within the familial and broader social contexts. Their agency is prominently demonstrated by their crucial involvement in addressing prevalent customs such as child marriage and the deeply rooted dowry system, which were widely prevalent in the village around six to seven years ago. A participant in the focus group discussion (FGD) embodies this profound transformation, articulating,

“Just five years ago, child marriage and dowry were pervasive occurrences. I myself was wed at the tender age of 14, with my family bestowing a dowry upon my husband’s family. However, we have since gained a heightened awareness of these detrimental societal norms, and we now unite in fervent protest against them.”

All the respondents of FGD then echoed, “Our collective voice also vehemently opposes acts of violence directed towards women.”

Within the familial sphere, decision-making dynamics have undergone a notable shift, culminating in the equitable prioritization of women’s opinions alongside those of men. A FGD respondent claimed that

“My family earlier thought that ‘Woman is inferior to man and she has no power. Man holds all the power in family and society. Women were born to perform household chores. She will take care of my father, mother, and children, nothing else. Why should I listen to her? What value does her opinion hold? Man is to earn, and woman is to cook.’ Now, my husband understands the value of my works. He prioritizes my opinions.”

Eleven additional participants in the focus group discussion (FGD) corroborated her assertion by recounting similar occurrences. This acknowledgment of women’s agency within both family and society has been fundamentally bolstered by their substantial financial and economic contributions within the familial unit. Furthermore, this recognition has transcended into the political domain, signifying an important transformation in their societal standing, which is labeled as political capital [36]. The heightened awareness has galvanized their participation in various social mobilizations, exemplified by their collective resistance against deeply entrenched practices such as child marriage, dowry systems, and diverse forms of violence perpetrated against women, encompassing physical and psychological dimensions. Moreover, this proactive stance has manifested in their active involvement in rural arbitration processes, underscoring a palpable departure from the scenario witnessed five years ago.

Our household surveys reflect the similar implications of ICT for enhancing the political capital. It shows that ICT made women aware of their rights and responsibilities in the society, which enhanced their active participation in rural arbitration and enlarged acceptance in decision-making processes in the family.

However, the introduction and implementation of ICT initiatives within the South Kharibari village have been directed towards augmenting human capital through a strategic emphasis on skill enhancement and capacity building. This concerted effort has fostered an enabling environment that empowers women within the community. The process of transforming nonproductive women into productive contributors involves a multifaceted approach encompassing the augmentation of capacities, skills, and knowledge. In this endeavor, the exploration of social capital, complementing the strides in human capital, often entails the establishment of robust networks that link women with diverse entities, including government organizations and nongovernment organizations (NGOs). A profound consequence of this holistic approach is discernible financial progress, which, in turn, has spurred an upsurge in women’s investments in settlement and land purchasing, leveraging their self-earned resources. This financial empowerment translates into an elevated stature within the familial framework, positioning these women as pivotal stakeholders in the decision-making processes that significantly shape family dynamics. Furthermore, women’s roles extend beyond the confines of their households, assuming a profound significance in the broader societal context. Their active involvement in curbing instances of violence and injustice targeted at them stands as a testament to their agency. This engagement extends to proactive efforts in combating entrenched practices such as dowry and child marriage, reflecting their commitment to effecting transformative change within their community.

3.2. ICT, Women, and Agriculture: Challenges for Sustainability

ICT has generated a visibly positive influence on the livelihoods of female agrarian practitioners, rectifying the challenges inherent to crop cultivation due to natural adversities, such as droughts, floods, excessive fog, and heavy rainfall. Nonetheless, this technological intervention has concurrently engendered certain challenges within the purview of local women farmers. Our empirical inquiry, rooted in survey data, reveals a significant assertion made by 71 percent of respondents, affirming their substantial reliance on ICT. When confronted with impediments to optimal crop production, these women have consistently turned to ICT-enabled solutions to ameliorate the prevailing challenges. Particularly, antecedent to the extensive acclimatization of ICT into their operational settings, these farmers traditionally drew upon intergenerational agroecological knowledge to address and mitigate such challenges. Evident from our findings is the revitalized impact of excessive ICT reliance, which has hastened distinct shifts of traditional agroecological knowledge in conceptions and operational modalities within the agricultural domain. This assertion is substantiated by a participant in a focal group discussion (FGD):

“My spouse and I engaged in agricultural practices based on our personal expertise prior to the advent of ICT. After the commencement of its utilization, my complete focus was directed towards the management of agricultural techniques, encompassing the preparedness for flood, high rain, and pest control. I have lacked confidence in my past expertise and knowledge within the agroproduction process.”

Furthermore, despite receiving training in the utilization of ICT in agriculture, a number of woman farmers encounter difficulties in effectively utilizing these tools. This issue can primarily be attributed to the prevailing lack of literacy among these women. This literacy gap, in turn, leads to a situation where the comprehension and proper application of ICT tools remain elusive. When farmers were provided informative messages alerting them to potential attack of insects and natural occurrences such as floods, and heavy rainfall, these women depend on their school-going children to verbally convey and elucidate the contents of the messages. These children effectively function as intermediaries, undertaking the role of information translators for their parents. However, this translation process is conducted without any formal training or guidelines, thereby introducing the possibility of misinterpretation or incomplete conveyance of the message’s essence. Consequently, this reliance on untrained intermediaries engenders a set of challenges within the domain of agricultural practices. The inherent lack of proper training and guidance in message translation leads to the potential distortion of critical information. This distortion, in turn, has cascading effects on the decision-making processes of farmers, impeding the effective execution of agricultural strategies for preparing against natural events and insects.

As reasoned by an FGD respondent,

“My partial educational level prevents me from comprehending the textual communications received from service providers. Consequently, I habitually engage my daughter or another proficient reader to assist me in perusing these messages. However, instances arise wherein the conveyed content proves challenging for them to convey with optimal clarity.”

All surveyed households unanimously asserted that financial constraints act as significant barriers to accessing ICT and its associated services. As claimed by FGD respondents,

“We, one hundred women farmers, were equipped with smartphones and received comprehensive training for operating. The initiative also encompassed provisions for monthly Internet connectivity. Consequently, a notable increase in technological utilization was observed amongst the participants. However, it is worth highlighting that financial constraint affects the acquisition of smartphones for the people who are not included in the project. In several instances, the acquisition necessitates a monetary outlay equivalent to the cumulative earnings of two to three months. This financial strain considerably complicates the procurement of high-cost mobile devices. Furthermore, it is imperative to highlight that the ongoing utilization of these devices is contingent upon consistent access to the Internet, which experiences an additional cost exceeding 200 taka per month. For impoverished rural inhabitants, these financial burdens engender substantial challenges to purchase a phone along with internet.”

Two cases have come to light involving individuals who were beneficiaries of ICT support but, unfortunately, their phones were damaged. As a result of this, they were unable to avail further ICT assistance from the sponsoring organization due to the loss of their devices. Regrettably, they have been unable to make progress in enhancing their skills through ICT, and their limited incomes have posed a barrier to acquiring replacement mobile phones.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the impacts of information and communication technology (ICT) on the livelihoods of women farmers, as well as to identify the challenges that hinder their sustainability.

The results of the research indicate that ICT has a substantial impact on the development of sustainable livelihoods among women farmers in the study area. This study provides evidence to support the findings of prior studies. For example, Biswas et al. [12], Sarker et al. [37], and Tithi et al. [13] investigated the effect of information and communication technology (ICT) on the livelihoods of women cultivators. Our research revealed that the implications of ICT are comprehended through the facilitation of capital accumulation processes, including human, social, financial, physical, and political capital. The study’s findings suggest that ICT has had multifaceted impacts on the livelihoods of women farmers. It has not only enhanced the economic wellbeing of women farmers but has also fostered the creation of networks and the sharing of knowledge among farmers, both men and women, who occupy similar socioeconomic positions within their respective communities. Furthermore, our study shows that ICT plays a substantial role as a catalyst in promoting women’s social, economic, and political empowerment. These findings align with prior research, exemplified by Biswas et al. [12].

Despite its commendable noteworthy contributions to enhance the wellbeing of rural women farmers, ICT has concurrently given rise to some intricate challenges. Throughout history, the diffusion of farming knowledge has primarily occurred orally and experimentally. This approach has not only imparted valuable information but also nurtured strong interpersonal bonds and a sense of togetherness within communities. Various investigators have been involved in debates about the nature of farmers’ experiments, contending that they differ fundamentally from formal scientific trials. These distinctions are rooted in unique categories and backgrounds that deviate from the conventions of Western science, as supported by Chambers and Jiggins [38], Salas [39], Kronik [40], and Saad [41]. Salas [39] emphasized the community aspect of knowledge creation, stating that it is a collaborative endeavor involving the entire community rather than an individual pursuit. However, our study discovered an intriguing observation: the persistent reliance on digital resources has considerably diminished the necessity for direct interactions and direct knowledge sharing within the community. This shift has led to a decline in the eminence of indigenous knowledge networks within the local community. As a result, the once-vibrant exchanges of traditional wisdom are gradually fading, potentially impacting the cohesion and richness of the community’s collective knowledge.

Furthermore, ICT also influenced farming decisions by favoring certain high-yield crops or commercial varieties, ignoring the historically existing intergenerational cropping practices. As claimed by the FGD respondents, maize cultivation has become popular in the areas over the last couple of years, replacing their popular traditional multicropping practices, including jute and wheat. For augmenting the maize production, as Tithi et al., [13] mentioned, an app, “Bhutta” (Bengali name of maize), was developed rather than emphasizing the traditional crop production. However, field data revealed that the digital platforms have overlooked the cultivation of diverse indigenous crops adapted to local environments for many years. This shift towards monoculture farming may accelerate the loss of traditional plant varieties and associated knowledge of their cultivation and utilization.

One of the greatest challenges in designing applications for developing communities is that potential users may have limited literacy [42]. As reported by Banglapedia, the average literacy rate of Dimla upazila is 36.2% [43]. As mentioned by Sarker et al. [37] at the outset of the project, the challenges included the limited functional literacy among women and their unfamiliarity with the capabilities of smartphones. Our study reveals that women farmers who lack literacy struggle to use these tools. They use their children as intermediates, but their lack of formal training and guidance led to misinterpretation and incomplete message transmission, influencing decision making and impeding effective agricultural measures against natural disasters and insects.

The involvement of people in ICT is dependent upon factors such as socioeconomic status, education, and resources, which is termed the “digital divide” [44]. Moreover, the statistic indicates that women’s access to mobile phones and the Internet is very limited in Bangladesh [16]. In light of the research findings, it becomes evident that financial limitations impose formidable barriers that inhibit agrarian stakeholders from unfolding the potential of ICT, resulting from its considerable associated costs. Additionally, a consensus emerged from the discourse within focus group discussions (FGDs) whereby respondents uniformly verified the conspicuous absence of personal mobile communication devices among a number of woman farmers residing within the village, thereby aggravating their inability to even contemplate venturing into the realm of Internet accessibility.

The study, however, acknowledges the positive implications of ICT on the livelihoods of rural farmers. It emphasizes the effective integration and institutionalization of ICT services to ensure the long-term sustainability of these positive impacts obtained. The study suggests that in the institutionalization process of ICT supports, women’s indigenous agroecological knowledge should be taken into consideration. This study also suggests that ICT support should be centered on the popular traditional multicropping practices; rather focusing on commercial monocrop production practices.

5. Conclusions

The findings of the study brought to light the substantial role that ICT plays in enriching the livelihoods of women farmers residing in the study area. This is achieved through the facilitation of diverse forms of capital, encompassing human, social, financial, physical, and political capital, by establishing an enabling environment and alleviating impoverishment among women farmers. On the contrary, the disappearance of agroecological knowledge, displacement of traditional cropping by high-yielding varieties, illiteracy, and financial constraints of buying ICT equipment creates serious obstacles for its sustainability dimensions. In order to effectively integrate ICT into rural communities, it is of utmost importance to incorporate invaluable indigenous and local agroecological knowledge. This approach combines modern technological interventions with traditional wisdom, enhancing the efficiency and long-term sustainability of ICT-driven advancements in agriculture. Negligence in addressing these challenges could result in ICT principally fostering market-oriented economic growth while disregarding the wellbeing and concerns of local communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.R. and H.H.; methodology, M.M.R. and H.H.; software, M.M.R.; validation, M.M.R. and H.H.; formal analysis, M.M.R. and H.H.; investigation, M.M.R. and H.H.; resources, M.M.R. and H.H.; data curation, M.M.R. and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, H.H.; visualization, M.M.R.; supervision, M.M.R. and H.H.; project administration, M.M.R. and H.H.; funding acquisition, M.M.R. and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This collaborative research endeavor was undertaken with joint financial support from the Institute for Advanced Research (IAR) at United International University, Bangladesh, and Oxfam, Bangladesh, under the auspices of project code IAR/01/19/BE/08.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- FAO. The Future of Food and Agriculture: Trends and Challenges. 2017. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i6583e/i6583e.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2023).

- Rahman, M.M.; Huq, H.; Hossen, M.A. Patriarchal Challenges for Women Empowerment in Neoliberal Agricultural Development: A Study in Northwestern Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Roles of Women in Agriculture; Prepared by the SOFA Team and Cheryl Doss. FAO: Rome, Italy. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/am307e/am307e00.pdf (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Damisa, M.A.; Samndi, R.; Yohanna, M. Women participation in agricultural production: A probit analysis. J. Appl. Sci. 2007, 7, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- World Bank. World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.TOTL.FE.ZS (accessed on 22 April 2023).

- Tabassum, N.; Rezwana, F. Bangladesh Agriculture: A Review of Modern Practices and Proposal of a Sustainable Method. Eng. Proc. 2021, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S.; Alam, M.J.; Bell, R.W.; Boyd, D.; Hutchison, J.; Miah, M.M. Fertilizer use gaps of women-headed households under diverse rice-based cropping patterns: Survey-based evidence from the Eastern Gangetic Plain, South Asia. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musungwini, S.; Gavai, P.V.; Munyoro, B.; Chare, A. Emerging ICT Technologies for Agriculture, Training, and Capacity Building for Farmers in Developing Countries: A Case Study in Zimbabwe. In Applying Drone Technologies and Robotics for Agricultural Sustainability; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Chandio, A.A.; Gokmenoglu, K.K.; Sethi, N.; Ozdemir, D.; Jiang, Y. Examining the impacts of technological advancement on cereal production in ASEAN countries: Does information and communication technology matter? Eur. J. Agron. 2023, 144, 126747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kountios, G.; Konstantinidis, C.; Antoniadis, I. Can the Adoption of ICT and Advisory Services Be Considered as a Tool of Competitive Advantage in Agricultural Holdings? A Literature Review. Agronomy 2023, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamba, S.Y.; Mlozi, M.R. Factors influencing the use of mobile phones in communicating agricultural information: A case of Kilolo District, Iringa, Tanzania. Int. J. Inf. Commun. Technol. Res. 2012, 2, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, M.; Anwar, M.; Stillman, L.; Oliver, G. Understanding information and communication opportunities and challenges for rural women through the sustainable livelihood framework. In International Conference on Information; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 175–191. [Google Scholar]

- Tithi, K.T.; Chakraborty, T.R.; Akter, P.; Islam, H.; Khan Sabah, A. Context, design and conveyance of information: ICT-enabled agricultural information services for rural women in Bangladesh. AI Soc. 2021, 36, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, M.M.H. The Role of Women in Food Security; Cuadernos de Estrategia: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Volume 161, pp. 82–96. [Google Scholar]

- ITU. New ITU Data Reveal Growing Internet Uptake but a Widening digital Gender Divide. 2019. Available online: https://www.itu.int/en/mediacentre/Pages/2019-PR19.aspx (accessed on 25 November 2022).

- GSMA. Connected Women the Mobile Gender Gap Report 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/r/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 11 August 2023).

- Sarker, A. ICT for Women’s Empowerment in Rural Bangladesh. Ph.D. Thesis, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gurumurthy, A. Gender and ICTs: Overview Report; University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studie: Brighton, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, P. Putting Beijing Online: Women Working in Information and Communication Technologies: Experiences from the APC Women’s Networking Support Programme; Association for Progressive Communications: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kabeer, N. Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev. Change 1999, 30, 435–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, J.; Zaman, S. Connecting local and global technological knowledge sourcing. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2018, 28, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis; IDS: Brighton, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Conway, G. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: Practical Concepts for The 21st Century; IDS Discussion Paper 296; IDS: Brighton, UK, 1992; Volume 33, pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Sustainable Livelihoods Guidance Sheets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- DFID. Achieving Sustainability: Poverty Elimination and the Environment, Strategies for Achieving the International Development Targets; Department for International Development: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.M.; Rahman, M.M. Char formation process and livelihood characteristics of char dwellers of alluvial river in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the ICSE6 Paris, Paris, France, 27–31 August 2012; pp. 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Sarrica, M.; Denison, T.; Stillman, L.; Chakraborty, T.; Auvi, P. “What do others think?” An emic approach to participatory action research in Bangladesh. AI Soc. 2017, 34, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Sociological Explanations between Micro and Macro and the Integration of Qualitative and Quantitative Methods. Hist. Soc. Res. 2001, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, V.D.; Thomas, H.; Cronin, A.; Fielding, J.; Moran-Ellis, J. Mixed methods. Res. Soc. Life 2008, 3, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Knappertsbusch, F.; Langfeldt, B.; Kelle, U. Mixed-Methods and Multimethod research. In Soziologie—Sociology in the German-Speaking World; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Huq, H.; Mukul, S.A. Implications of Changing Urban Land Use on the Livelihoods of Local People in Northwestern Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Application of the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework in Development Projects. 2017. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/latinamerica/UNDP_RBLAC_Livelihoods-Guidance-Note_EN-210July2017.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2020).

- Lontchi, C.B.; Yang, B.; Su, Y. The Mediating Effect of Financial Literacy and the Moderating Role of Social Capital in the Relationship between Financial Inclusion and Sustainable Development in Cameroon. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majale, M. Towards Pro-Poor Regulatory Guidelines for Urban Upgrading. Regulatory Guidelines for Urban Upgrading; Schumacher Centre for Technology and Development: Bourton-on-Dunsmore, UK, 2002; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.; Caihong, Z.; Ekanayake EM, B.P. Livelihood improvement through agroforestry compared to conventional farming system: Evidence from Northern Irrigated Plain, Pakistan. Land 2021, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, P.; Sinha, S. Linking Development with Democratic Processes in India: Political Capital and Sustainable Livelihoods Analysis; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sarker, A.; Biswas, M.; Anwar, M.; Stillman, L.; Oliver, G. Empowering women through smartphones in rural Bangladesh. In Technology and Women’s Empowerment; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R.; Jiggins, J. Agricultural Research for Resource Poor Farmers—A Parsimonious Paradigm Division; Institute of Development Studies, University of Sussex: Brighton, UK, 1986; Volume 38, p. 220. [Google Scholar]

- Salas, M.A. The technicians only believe in science and cannot read the sky’: The cultural dimension of the knowledge conflict in the Andes. In Beyond Farmer First: Rural People’s Knowledge, Agricultural Research and Extension Practice; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1994; pp. 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kronik, J. Investigating Local Knowledge of Plant Genetic Resources: A methodology based on the case of Laguna La Cocha in the Colombian Andes. Cespedesia 1996, 21, 219–243. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, N. Farmer Processes of Experimentation and Innovation: A Review of the Literature; CGIAR: Cali, Colombia, 2001; p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- Medhi, I.; Menon, S.R.; Cutrell, E.; Toyama, K. Beyond Strict Illiteracy: Abstracted Learning among Low-Literate Users. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development, London, UK, 13–16 December 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Banglapedia. Dimla Upazila—Banglapedia. Available online: https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php/Dimla_Upazila#:~:text=Literacy%20rate%20and%20educational%20institutions,education%20centre%2016%2C%20madrasa%20102 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Torero, M.; Von Braun, J. (Eds.) Information and Communication Technologies for Development and Poverty Reduction: The Potential of Telecommunications; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).