Abstract

Digital transformation and smartization projects in industrial enterprises have become increasingly prevalent in recent years, aiming to enhance operational efficiency, productivity, and sustainability. Assessing the outcomes of such projects is crucial to determine their effectiveness in enabling sustainability. In this context, a model for evaluating digital transformation smartization projects (DTSP) outcomes can be developed to provide a comprehensive assessment framework. This study aims to develop and test a model for diagnosing the results of implementing digital transformation smartization projects for industrial enterprises. The methodology presented in this article involves using statistical tests to detect multicollinearity and heteroskedasticity in regression models. It also proposes an economic–mathematical model with three objective functions to optimize the implementation of smartization projects, considering cost minimization, deviations from planned business indicators, and production rhythm disruptions. The most important results of the survey are (1) a proposed matrix for the selection of indicators for diagnosing the results of the implementation of digital transformation smartization projects for industrial enterprises, (2) a two-level model for the economic evaluation of diagnosed digital transformation smartization projects, which can be used at any stage of the digital transformation smartization project and based on it, conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of the implementation of both the entire project and its individual stages, objects, or elements. The advantage of the model is the possibility of its decomposition, that is, a division into separate parts with the possibility of introducing additional restrictions or, conversely, reducing the level of requirements for some of them. The results were tested at industrial enterprises in Ukraine and proved their practical significance.

1. Introduction

In an era defined by rapid technological advancements, the concept of digital transformation has emerged as a pivotal force reshaping industries worldwide. As industrial enterprises grapple with the challenges posed by an ever-evolving business landscape, they are increasingly turning to smartization projects to survive and thrive in this digital age. These projects, characterized by the infusion of intelligent technologies such as IoT, AI, and data analytics into industrial processes, promise to enhance operational efficiency, reduce costs, and unlock new avenues for innovation.

While the potential benefits of digital transformation smartization projects are widely recognized, their outcomes still need to be guaranteed. The road to successful smartization is fraught with complexities, ranging from technical hurdles to organizational resistance. Moreover, as the world faces escalating concerns over environmental sustainability, it has become imperative to assess the impact of these projects not only in terms of profitability but also in their contributions to a greener and more sustainable future.

This article delves into the multifaceted realm of digital transformation smartization in industrial enterprises and aims to provide a comprehensive framework for evaluating their outcomes with a particular emphasis on sustainability. It is well-established that sustainability considerations are no longer peripheral concerns but integral to modern organizations’ strategic decisions. As such, any assessment of digital transformation projects must incorporate sustainability as a key performance indicator.

The journey toward digital transformation is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Each industrial enterprise faces unique challenges, opportunities, and environmental contexts, necessitating a nuanced approach to assessing the outcomes of smartization initiatives. This article seeks to address this need by proposing a model that considers the diverse facets of digital transformation and sustainability.

By integrating these components, the model for assessing the outcomes of digital transformation DTSP in industrial enterprises can provide a comprehensive framework to evaluate the projects’ effectiveness in enabling sustainability. The model’s results can guide decision-making processes, identify areas for improvement, and support the development of future projects that prioritize sustainability goals.

To achieve the set goal, the following tasks must be performed consistently:

- –

- To study the essence of the concept of smartization and digital transformation smartization projects;

- –

- To explore the relationship between smartization and sustainable development;

- –

- To develop a system of indicators for evaluating the results of the implementation of DTSP;

- –

- To develop a model for diagnosing the results of implementing DTSP for industrial enterprise;

- –

- To test the proposed model on a sample of industrial enterprises.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. The Concept of Smartization and Digital Transformation Smartization Projects

After the World Economic Forum in 2016, the current state of society began to be called the era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, the scale and complexity of transformations of which will be fundamentally new and unfamiliar to humanity. The response to this challenge must be integrated and comprehensive, involving all actors, from the public and private sectors to academia and civil society. Under such conditions, the questions of the essence and form of the integration of enterprises in the new era, the use of opportunities, and the prevention of risks caused by the Fourth Industrial Revolution are brought into focus. On the one hand, industrial enterprises can take advantage of the opportunities of the new system, eliminate the existing shortcomings of management, and become leaders of the world market—smart (intelligent) factories. On the other hand, the turbulence and riskiness of the new system require new management of this process.

A smart factory is a modern production of a new generation for the production of globally competitive and customized products, as well as for solving the urgent tasks of the development of high-tech export of products based on the application of advanced production technologies with the effective application of the concept of open innovation and the transfer of advanced science-intensive technologies.

Thus, a smart factory is the desired result of the enterprise, but it is necessary to invest in this concept of not only automation but also the characteristic features of smartization; the process of achieving this result is smartization. The achievement of this result is expressed in the management of smartization projects of the enterprise.

Smartization is the targeted introduction of the optimum latest global achievements into the sphere of innovations of the enterprise for the efficient use of resources, increasing the synergetic efficiency of all business processes at the enterprise for the effective achievement of the set goals in the short and long term in the conditions of the constant change in the environment [1].

So, to better understand the author’s vision, the term “smartization” can have the following synonyms: smart factory; smart production; smart industrialization; smart industry, etc., but smartization has a broader interpretation. Smartization is not only the use of information technologies; it is a new approach to the organization of all activities in an industrial enterprise.

The conceptual foundations of various aspects of smartization were considered by the authors in previous works [2,3,4], but the issue of evaluating the results of smartization projects remained unsolved, so the purpose of this study is to develop and test a model for diagnosing the results of the implementation of smartization projects for industrial enterprises.

Digital transformation smartization projects in industrial enterprises can be defined as strategic initiatives that aim to utilize advanced digital technologies and innovative approaches to enhance the efficiency, competitiveness, and adaptability of industrial organizations within the context of the Fourth Industrial Revolution. These projects involve integrating cutting-edge technologies, data-driven decision-making, and comprehensive organizational changes to optimize resource utilization, foster innovation, and achieve sustainable business goals in an ever-evolving industrial landscape.

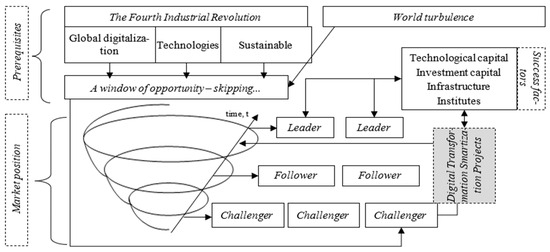

Thus, we define the digital transformation smartization projects as their targeted rethinking and redesigning using information and innovation technologies through the intelligent use of resources; then, it is considered a tool by which industrial enterprises can use the “window of opportunity” (Figure 1) and, saving resources (time, costs) will accelerate the approach to industry leaders.

Figure 1.

Digital transformation smartization projects for using the “window of opportunity” [5].

Thus, these projects will allow the enterprise to quickly and efficiently (due to the depreciation of financial investments) approach the leading position, that is, take the role of a follower. However, the important fact that such enterprises will never be able to become industry leaders (unless the leader leaves the market) should be noted; this requires more breakthrough innovative technologies. Smartization is aimed precisely at effectively optimizing resources (all their kinds), focusing on sustainable development. At the same time, it is pretty challenging to keep leadership positions; leaders usually consist of two or three enterprises, while sustainable, smartized development will allow the enterprise to prosper for many years.

2.2. Linking Smartization and Sustainable Development

Pursuing sustainable development has become an imperative for industrial enterprises in the 21st century [6,7]. Beyond traditional profit-centric models, these enterprises now recognize that their actions have far-reaching consequences for the environment, society, and their long-term viability. In this context, digital transformation smartization projects emerge as a potent catalyst for aligning industrial operations with sustainability principles.

Digital transformation smartization projects entail the strategic integration of cutting-edge technologies, data-driven processes, and intelligent systems into the fabric of an industrial enterprise [8]. When thoughtfully designed and executed, this transformative journey can produce many synergies that reinforce sustainable development goals. Here’s how:

- Resource Optimization: At the core of smartization lies the ability to optimize resource utilization [9]. Through real-time data analytics and process automation, industrial enterprises can reduce energy consumption, minimize waste, and enhance resource efficiency. This not only lowers operational costs but also reduces the enterprise’s ecological footprint;

- Emissions Reduction: Smartization empowers industrial enterprises to monitor and control emissions more effectively. Whether through predictive maintenance to reduce emissions from machinery or by optimizing logistics to minimize transportation-related emissions, digital technologies play a pivotal role in advancing sustainability [10,11];

- Circular Economy Integration: Smartization projects enable the transition to a circular economy model, where products and materials are reused, refurbished, or recycled. By tracking product lifecycles, managing returns efficiently, and promoting sustainable product design, enterprises can contribute to a more circular and environmentally responsible economy [12,13];

- Environmental Compliance: Meeting and exceeding regulatory environmental standards is crucial for sustainability. Smart systems provide real-time monitoring and compliance reporting tools, helping enterprises avoid costly penalties and reduce their environmental impact [14,15];

- Supply Chain Transparency: Digital transformation enhances transparency within the supply chain. This transparency is essential for identifying and mitigating social and environmental risks in the supply network, ensuring suppliers adhere to sustainable practices [16];

- Social Responsibility: Sustainable development extends beyond environmental concerns to encompass social responsibility [17]. Smartization projects can include initiatives to improve workplace safety, labor conditions, and employee well-being, contributing to the social pillar of sustainability;

- Innovation and Competitiveness: Sustainability often drives innovation. Digital transformation can spark creativity and new business models, creating opportunities for enterprises to differentiate themselves in the market and tap into sustainable product lines or services [18,19];

- Stakeholder Engagement: Smartization facilitates better engagement with stakeholders, including customers, investors, and the community. Demonstrating a commitment to sustainability through digital transparency and reporting can enhance an enterprise’s reputation and build trust;

- Long-Term Resilience: By optimizing operations and reducing environmental risks, smartization projects enhance an enterprise’s long-term resilience in the face of climate change, resource scarcity, and other sustainability-related challenges;

- Data-Driven Decision-Making: Smartization leverages data analytics to inform decision-making. This data-driven approach allows enterprises to make informed choices that align with their sustainability objectives, from supply chain optimization to energy management.

So, Digital transformation smartization projects hold immense potential for industrial enterprises seeking to advance their sustainability agenda. In an era where sustainability is not only a choice but a necessity, smartization emerges as a strategic imperative for industrial enterprises committed to the long-term viability and responsible global citizenship. By harnessing the power of technology and data, these projects can lead to resource efficiency, emissions reduction, circular economy practices, improved supply chain sustainability, and enhanced stakeholder engagement. These synergies highlight the importance of integrating sustainability considerations into digital transformation strategies and further reinforce the idea that smartization and sustainable development are not mutually exclusive but rather mutually reinforcing pathways to a better future.

2.3. Development of Indicators for Diagnosing the Results of the Implementation of DTSP for Industrial Enterprises

The problem in diagnosing the results of the implementation of DTSP is the impossibility of evenly distributing the efforts of the control subsystem between different objects at different stages of project implementation. Thus, the intensification of the intellectual activity of the staff has its limits, which cannot be crossed due to the threat of “burnout” of employees and the subsequent sharp drop in their productivity. However, such intensification is essential at the beginning of project implementation; without it, it is impossible to evaluate the response of the managed subsystem to management actions, which are the essence of the diagnosed project.

The smartization project, which is ready for implementation, is aimed at changing the given objects of the management system. These changes must be diagnosed dynamically; that is, the result of the project implementation is not only fixed indicators or compliance with the specified criteria but also a study of the stability of the impact over time. The consequence of most implemented DTSP is an impact not only on the target objects but also an indirect impact on other management subsystems of the enterprise. Sometimes, the strength and stability of such influence exceed the corresponding parameters of the target objects of smartization. This means that indirect effects must also be diagnosed and include relevant business indicators in alternative sets of indicators. The diversity of objects of influence, their different importance, complexity, and incomplete hierarchy determine the need to codify the elements of the management system to organize the relevant indicators with their subsequent combination within the limits of the proposed sets. Summarizing the scientific research [20,21,22,23,24,25], we present the groups of elements of the industrial enterprise management system (Table 1).

Table 1.

Codification of the elements of the management system of an industrial enterprise (source: supplemented by the authors based on [2,3,4,20,21,22,23,24,25].

Using such a system of designations, it is possible to form different sets of indicators, to highlight among them the indicators of the impact of the smartization project on various objects of the management system, taking into account whether these objects were the goals of the project or whether the impact on them was a side effect of the project implementation. It is most convenient for further data processing to have the same dimension of the indicator matrix for different objects.

If this cannot be achieved, then the maximum dimensionality of the matrix is taken, and in smaller sets of indicators, a unit is placed on the empty places. The final goal is the formation of two–three sets of indicators that can be considered the indicators of the success of project implementation and contain elements of the initial combinations of indicators for the primary and additional objects of influence:

where —indicators of diagnosing the impact on individual elements of the target object of the smartization project (in this case, S—strategy);

; n—the number of sets of indicators;

; m—the number of indicators in the set;

; l—the number of control object elements;

—indicators of diagnosing the impact on the target object of the project;

—weights of individual indicators in sets for target objects (the same for all sets within the target object);

—aggregated indicators according to the i-th set of indicators for the target object;

—indicators of diagnosing the impact on individual elements of the object of the smartization project, which was not targeted (in this case, C—sales);

—indicators of diagnosing the impact on a non-target object of the project;

—weights of the individual indicators in sets for non-target objects (the same for all sets within a non-target object);

—aggregated indicators according to the i-th set of indicators for a non-target object;

—indicators that simultaneously characterize the impact on target and non-target objects of the smartization project.

As a result of reviewing all possible combinations of indicators, we obtain two sets of indicators that characterize individual elements of target and non-target objects of the smartization project. Next, the project’s impact on these individual elements is diagnosed according to various combinations of indicators, and the convergence of the obtained results is determined. You can use aggregated indicators that reflect changes in individual indicators within the influence objects or their elements. And finally, a combination of target and non-target impact indicators can be used as indicators if, as a result of the implementation of the consulting project, it turns out that the latter have become predominant. Automating the seemingly complicated procedure of forming alternative sets of indicators is easy.

The fragment of the management system, represented by three objects, is described by four groups of indicators, which, according to the BSC technology, characterize the financial condition, work with consumers, personnel, and internal business processes (Table 2). However, although the indicators are not repeated, some simultaneously characterize either two objects or two directions according to the BSC system. Therefore, after the initial identification of the indicators (basic with the base “a” and mediated with the base “b”), one of the two paired indicators for each identified pair is discarded, as well as those that are less informative, if there is a limit on the size of the matrix of input parameters to the simulation modeling. It is advisable to impose restrictions on the structure of the data array because of the number of options for solving the combinatorial problem; i = 2, j = 5 will be optimal as two alternative sets of five indicators for each target object.

Table 2.

Matrix for the selection of indicators for diagnosing the results of the implementation of DTSP for industrial enterprises (source: proposed by the authors based on [2,4,9,10,26,27,28,29,30]).

2.4. Economic Evaluation of the Implementation of Diagnosed DTSP for Enterprises

Developing and implementing DTSP for industrial enterprises is quite complex due to technical and economic reasons. The industry needs technical and technological support, and the level of product innovation determines the competitive position of enterprises in the domestic and foreign markets [31,32]. At the same time, most of Ukraine’s large industrial enterprises are burdened with worn-out fixed assets; their assets are characterized by low liquidity, and their infrastructure is mainly unprofitable. All this complicates the implementation of the smartization of enterprises because, on the one hand, they must improve the elements of the enterprise management system. Still, on the other hand, they cannot recommend drastic measures to reorganize the business because, in the conditions of the deterioration of the economic situation, the loss of a significant part of sales markets and the disruption of relations with counterparties from CIS countries, industrial enterprises need external financing and a long period to adapt to current business conditions based on market competition [33,34].

Conducted preliminary studies [1,5,35,36] clearly proved that projects of smartization of business processes of enterprises have a positive effect not only on the target objects of smartization but also raise other elements of the management system to a higher level due to the activation of the intellectual activity of employees, increasing the responsibility of managers and intensifying control over carrying out separate technological operations and implementing typical business processes. From a managerial point of view, the results of the implementation of DTSP are apparent; they can be measured and controlled. However, deviations inevitably occur, some of which require further participation of the entities that developed and implemented the relevant projects. In this connection, the issue of evaluating the effectiveness of DTSP at the stage of their support after implementation and obtaining the planned result arises again.

To unify tools for the economic assessment of the implementation of DTSP, it is proposed to establish conditional permanent procedures for identifying the connections of business indicators for diagnosing the performance of DTSP with the general financial results of enterprises. These procedures will be permanent because of the stability of the evaluation objects; however, in the case of business restructuring or diversification of activities, they will still have to be changed.

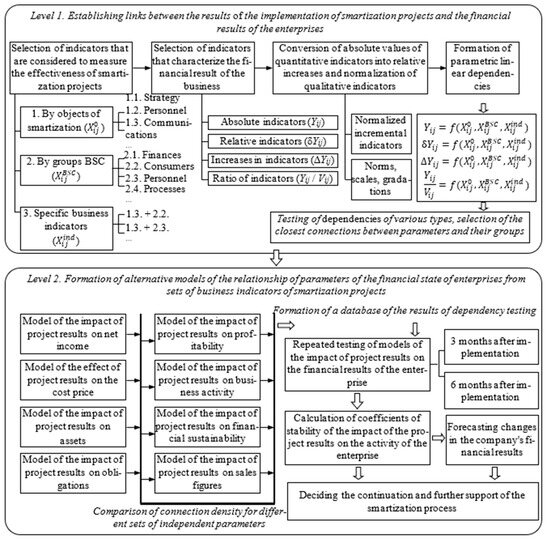

The economic evaluation of the implementation of smartization projects is variable from the point of view of the objects of smartization influence but can be unified in terms of the procedures for calculating indicators and interpreting the obtained results. A two-level approach is proposed for the economic evaluation of diagnosed DTSP (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Graphical model of the economic evaluation of the implementation of DTSP (source: developed by the authors).

At the first level, sustainable relationships between the performance parameters of DTSP and the enterprise’s financial results are identified and described. Stable relationships exist for at least six months after the smartization project was implemented, and the relationship density between parameters is not less than 0.667. Of course, from the point of view of statistics, correlation coefficients should be in the range of 0.75–0.95, but this is hardly achievable in the conditions of the Ukrainian industry. In addition, within six months, the requirements of the internal and external business environment will change, most of which cannot be predicted, and even more so, this impact cannot be separated from the results of the diagnosed smartization project, which also reduces the density of communication between the studied parameters.

At the second stage of the economic evaluation of the implementation of diagnosed DTSP, alternative models of the relationship of the key parameters of the financial state of enterprises with sets of results of DTSP are formed either by objects of influence or by the key business indicators with a universal purpose. The conducted research and calculations show that in most cases, the communication density between parameters is not high; therefore, it is advisable to form an economic–mathematical model for optimizing the implementation of diagnosed DTSP.

The distribution of the indicators, which are measures of the proven effectiveness of DTSP by smartization objects or BCS groups, is conditional; often, we operate with integrated specific business indicators that characterize several objects and/or groups of indicators of a balanced system simultaneously. For example, the indicator “effectiveness of the management system in terms of labor productivity” links the increase in labor productivity and the costs of maintaining the management apparatus; therefore, it simultaneously characterizes the budgetary component of the business and measures to intensify the intellectual activity of the staff along with the improvement in interpersonal communications. The main task is to establish dependencies between the results of the implementation of DTSP (independent variables) and the financial results of enterprises (dependent variables). It is not known in advance which possible dependencies will be characterized by sufficient connection density; therefore, all possible models are formed, their parameters are calculated, and those with the highest correlation coefficients are selected for further research. These models should be used for six months after the end of the implementation of DTSP, and only then can it be asserted that the dependencies exist and are stable enough to conclude the economic efficiency of smartization at the level of the entire enterprise and not its subsystems.

One of the constant technical problems when working with regression models is the partial dependence on individual factor variables. Multicollinearity leads to the fact that the estimates of the model parameters are shifted, the covariances of the estimates increase, and the deterioration of the t-statistics is observed. Multicollinearity cannot be completely avoided, so its influence on model estimates should be minimized. To a lesser extent, heteroskedasticity is still a problem (working with dynamic series). The assumption of the least squares method regarding the invariance of the variance of the residual term is not always fulfilled; one of the reasons is a purely psychological factor: with constant control of the same parameters at different time intervals, staff expectations unknowingly cause disturbances in the interpretation of qualitative parameter estimates.

Suppose the presence of multicollinearity is visible almost immediately (a considerable value of the coefficient of determination against the background of insignificant coefficients of the model and/or significant coefficients of pairwise correlation of factor variables), then detect heteroskedasticity. In that case, it is necessary to additionally test the models using the methods of Breusch–Pagan, Goldfeld–Quandt, Schleser, or Aitken [36,37,38]. The toolkit for detecting and eliminating the effects of multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity is well developed; therefore, standard approaches to testing the specified models were used, based on which a decision was made regarding their suitability for the economic evaluation of the implementation of diagnosed DTSP.

However, despite all attempts to reduce the input data to a normalized incremental form and select regression models with the best relationship density indicators and minimal influence of multicollinearity and heteroscedasticity, decisions have to be made in some cases based on expert judgments. These experts were recruited from among the teaching staff and leading specialists of industrial enterprises. Their decisions were collected and elaborated based on well-known methods and techniques of expert evaluation [39,40,41,42], and based on the obtained results, alternative models of relationships were chosen in those cases when, from a formal point of view, they were either wholly equivalent or had separate reservations for use.

The distribution of the variables of the selected alternative models of the relationship of the parameters of the financial state of enterprises from the sets of business indicators of DTSP (Table 3) was based on the following criteria: the number of factor variables four–six; pairwise correlation of the dependent variable and each of the factors—not less than 0.85, the minimum probability of multicollinearity and the conditional constancy of the variance of the residuals of the free terms. The input data for the modeling was obtained as a result of direct observation of the work of PrJSC “Iskra” and PrJSC “LLRZ” after the implementation of DTSP on them and thanks to computer modeling of the impact of similar projects on five more industrial enterprises from different regions (see Table 4 and Appendix A).

Table 3.

Distribution of factor variable models of the relationship of indicators of the financial condition of enterprises from sets of business indicators of DTSP (source: developed by the authors).

Table 4.

Results of computer modeling of the impact of implemented DTSP on the activities of other industrial enterprises (source: calculated by the authors).

The regression of probable dependencies was studied in two stages: first, “clean” data from seven enterprises were used, and later, those values that were significantly outside the limits of the explained variance of the dependent and factor variables were cut off.

Since the financial indicators according to the BSC system should have been present but were not targeted for the smartization project, they all ended up with the base “b” according to our codification. The same applies to indicator , which characterizes business processes that were not the target object but better reflected the indicators of personnel development in terms of communication skills. At the output, two matrices of indicators are formed, which are indicators of the smartization project and based on which it is possible to diagnose the results of its implementation:

Although only three target objects (strategy, personnel, communications) are considered, due to their connections with other elements of the management system, such objects as business processes, sales, technologies, and economic support will be diagnosed. To simplify perception, it is possible to change the index designations of indicators, introduce aggregated metrics by objects or their groups, and combine elements of smartization objects in different ways. This means that the proposed method of choosing business indicators is universal but does not require further detail within the scope of this study.

3. Research Method

Regression analysis is a convenient tool for researching relationships between variables [43,44], but more is needed to provide an answer to the question of resource allocation in the process of developing and implementing DTSP. In addition, at most enterprises that implemented DTSP, significant violations of the rhythm of production were observed, associated with the need to simultaneously carry out organizational changes and increase the level of staff involvement in management decision-making. These changes provide an impetus for business development in the future. Still, their implementation process is complex, often causes staff resistance, and provokes conflicts between individual employees, structural units, stakeholder interests, etc.

To take into account these aspects of the smartization practice, an economic–mathematical model is proposed for calculating the efficiency and optimizing the process of implementing DTSP, which will be able to reconcile the costs of implementing project solutions with the requirements of minimizing the deviations of the fundamental values of business indicators from the planned ones and at the same time ensure the slightest possible disturbances to the rhythm of production. The named conditions are reflected in three corresponding objective functions, which are transformed into a general model using the method of uniform linear optimization:

1. Minimization of uncovered costs for the design, implementation, and maintenance of the smartization project. Uncovered are the costs incurred at all stages of the implementation of the smartization project but not compensated by future savings on administrative costs or increased productivity of managerial labor.

where xij—uncovered costs for creating and implementing the smartization project under the i-th article at the j-th stage of implementation, thousand UAH.

where υij—the costs incurred directly for the smartization project under the i-th article at the j-th stage of implementation, thousand UAH;

ωij—savings under the i-th article at the j-th stage of the implementation of the smartization project, which will occur in the following periods as a result of the implementation of smartization, thousand UAH;

tj—coefficient that takes into account the depreciation of money at the jth stage (depends on the interest rate on the borrowing market);

; n—the number of expenditure items that change;

; m—the number of stages of the smartization project.

The implementation of the first function of the goal is subject to budgetary restrictions, namely,

where sj—the coefficient of unplanned costs, admissible due to compensation at the later stages of the implementation of the smartization project;

Vj—the budget of the smartization project at the j-th stage, thousand UAH.

where —the average annual interest rate on loans available to the enterprise; at the time of this study, ; i.e., the considered enterprises were, on average, lent at 21.5% in UAH.

where d—the marginal level of admissible savings in administrative costs; in this case, d = 0.25, limiting the maximum level of projected savings in administrative costs to 25%, because attempts at further savings will lead to abuses and attempts to distort actual data, i;

Wj—the fund for the maintenance of administrative personnel and general corporate expenses, operating at the jth stage of the smartization project.

where Kmax—the maximum lending rate that was effective for the enterprise last year, %;

τj—the time during which the j-th stage of the smartization project lasts, months;

2. Minimization of negative deviations of the actual values of business indicators from the planned ones:

where —the planned and actual values of the i-th business indicator, which characterizes the impact of the smartization project on the j-th object;

Θij—a Boolean variable that takes a single value only in case of negative deviation of the i-th business indicator from the plan; if the deviation is positive, then the Boolean variable takes a zero value, thereby excluding such a deviation from consideration;

; n—the number of business indicators that characterize the object;

; m—the number of objects of the smartization project;

3. Minimization of production rhythm violations during the implementation of the smartization project:

where —he planned and actual values of the rhythmicity coefficients of production of the i-th type of the j-th object (subdivision);

; n—the number of types of rhythmicity coefficients that characterize the object;

; m—the number of objects (subdivisions) that are subject to changes as a result of the implementation of the smartization project.

In contrast to the second function of the goal, positive deviations of the coefficients of rhythmicity are not cut off because their excess from the planned indicators also negatively affects the work of the enterprise: if the underestimation of the indicators of rhythmicity leads to losses due to the underloading of part of the production capacities, then the overestimation of these indicators, on the contrary, overloads individual subsystems management, which later begins to deteriorate their effectiveness. We are talking not only about production units, the rhythmic execution of all technological and control operations but also the maintenance of all business processes and communications.

The formed economic–mathematical model contains three equivalent objective functions F1(x), F2(y), F3(z), which, in the general formulation of the problem, have the same significance. Hence, it is possible to use the scheme of uniform optimization. In practice, it may turn out that budget constraints are not critical, and most control subsystems are not loaded to design capacity, so the priority will be the function F2(y)—minimization of deviations of business indicators. If the enterprise has financing problems, we focus on function F1(x)—minimizing the uncovered costs associated with implementing the smartization project. The rarest case is when the control system is really overloaded; then the F3(z) function will become critical, minimizing disruptions to the rhythm of business processes.

So, according to the scheme of uniform optimization, an additional problem is constructed, the objective functions are translated into constraints, and the basic economic–mathematical model is obtained:

where φ is the relative deterioration of the best value of each objective function, which is obtained during the partial solution for each function (assuming that the weights of all three functions F1(x), F2(y), F3(z) are the same);

—the optimal values of the target functions F1(x), F2(y), F3(z), which are obtained by solving three partial cases (one by one for each function separately, that is, the value of are exemplary, obtained under conditions where the other two functions do not exist, as well as their inherent limitations).

In expanded form, the economic–mathematical model will look like this:

This model can be used at any stage of the smartization project. Based on it, conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of the implementation of the entire project and its individual stages, objects, or elements. The advantage of this model is the possibility of its decomposition, that is, a division into separate parts with the possibility of introducing additional restrictions or, conversely, reducing the level of requirements for some of them. For example, when budget conditions change, adjusting the variable Vj (budget of the smartization project at the j-th stage) and/or the coefficient of unplanned expenses sj is enough. Often, there is a need to consider changes in credit conditions; then, we adjust the coefficients (average annual interest rate on loans available to the enterprise) and Kmax—the maximum lending rate of the previous year).

It is most difficult to change the conditions related to calculating the optimal value of the second objective function F2(y), which reflects the minimization of negative deviations of the actual values of business indicators from the planned ones. The fact is that the planned values of business indicators are mostly set at the level of the implemented smartization project after it has been created, but the customer often wants to see the forecast results for the objects vital to him, even at the project development stage. In this case, it is proposed to carry out a computer simulation of the reaction of the production and management subsystems of the enterprise to the “intervention” of smartization in its business processes. For such simulation results to be significant, it is possible to calculate the Model (19) in partial forms several times, setting the planned values of business indicators at the minimum permissible and desired levels. At the output, we obtain not unit values of deviations, but their ranges, which becomes a criterion for the ineffectiveness of the smartization project.

4. Results

The proposed scheme for selecting indicators for diagnosing the results of DTSP was tested at PJSC “Odeskabel” and PJSC “Lviv Locomotive Repair Plant” (hereinafter PJSC “LLRP”) since these enterprises had practice in similar directions, namely, smartization of business processes related to the improvement in strategic planning, personnel work, or the communication system. Simulation modeling of the impact of a similar smartization project on the results of operations was carried out at five more enterprises (based on the hypothesis that these enterprises will develop stably even without smartization within the limits of the increases in indicators that they demonstrated in previous periods). The influence of external environmental factors is excluded, and the deviations in demand, prices, exchange rates, and the consequences of state regulation are neglected. In such conditions, a computer simulation was carried out, which involved reproducing the impact of real DTSP of PJSC “Odeskabel” and PJSC “LLRP” on the input data of the other five enterprises in the same time intervals.

Technologically, the hypothetical impact of the standardized project of smartization on the work of enterprises was diagnosed according to the following mechanism:

- (1)

- For each indicator from the selected sets, the structure and dynamics of changes during the calendar year 2021 are monitored, and attention is paid to the smoothness of changes in indicators and the connections between them;

- (2)

- As far as possible, the influence of price indexation, exchange rate fluctuations, and the influence of state regulation is eliminated;

- (3)

- A dynamic model of indicator increments is formed, i.e., the trends of changes in each indicator are monitored in the absence of additional influences;

- (4)

- The hypothetical impacts of the smartization project are superimposed on each indicator (in proportion to those that actually occurred at PJSC “Odeskabel” and PJSC “LLRP”);

- (5)

- Parameter differences are monitored, and the “net” impact of the diagnosed smartization project is calculated.

We calculate the parameters of the models of the relationship of indicators of the financial condition of enterprises and the resulting business indicators on the primary data obtained from the implemented DTSP of PJSC “Odeskabel” and PJSC “LLRP” and simulated for five more industrial enterprises (Table 4). In some cases, the list of indicators can be expanded due to those not included in the basic sets of business indicators (see Table 2 and Appendix B) but are informative in the context of individual DTSP.

The results of such simulation (Table 4) indicate a high level of convergence of diagnostic indicators, which proves the effectiveness of the proposed indicator selection scheme. The input data of the computer simulation are given in Appendix A.

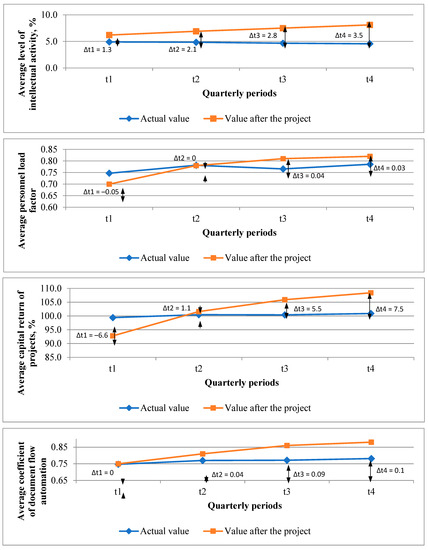

For presenting the results of DTSP to the management of customer enterprises, graphic constructions that reflect the comparative dynamics of changes in indicators are well-suited. Such graphs are built automatically; they can be grouped by objects of influence, the composition of indicators, the structure of changes, etc. For example, a visualization of the impacts of the smartization project averaged according to the data of those enterprises that were the objects of this study, is given. Since most DTSPs are implemented annually, four quarterly periods are taken as a basis (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graphical interpretation of individual results of the implementation of the smartization project diagnosed at the investigated enterprises (source: calculated by the authors).

The obtained results, among other things, demonstrate the deterioration of individual indicators and highlight the need for situational relaxation of requirements for individual results of the smartization project. For example, in the first quarter, the average staff utilization ratio is reduced because, due to innovations, part of the employees cannot perform some types of work on time (software is changed, technical means are updated, part of the functional duties undergo changes, rotations occur, etc.). Also, in the beginning, the average return on capital of projects of a strategic nature, which were started before the implementation of smartization proposals, is sharply reduced because financial and human resources are diverted to other works. However, later, the values of these indicators level off and reach levels that would be attainable with the implementation of the smartization project.

Separate results of modeling the impact of implemented DTSP on the activities of some industrial enterprises also demonstrate a relative deterioration (for example, —wage intensity of products or —costs of maintaining the communications system). This is quite natural since the wage fund increases to stimulate the intellectual activity of employees and communication costs increase, without which it will not be possible to increase the automation of business processes. At individual enterprises, the situation is significantly different from the average trend; in particular, PJSC “Iskra” has a much higher initial level of development of information and technological work support; therefore, the growth of its indicators is much more modest. On the other hand, due to the economic and political circumstances of the region, JSC “Ekvator” is losing its production capacity, which cannot be eliminated in the modeling (see Table 2).

In the first stage, nine multivariate regression equations were obtained, five of which were characterized by an insignificant coefficient of determination (R2 < 0.33). The regression analysis results (Appendix B, Table A25, Table A26, Table A27, Table A28, Table A29, Table A30, Table A31, Table A32 and Table A33) show that the weak connection between the indicators is short-term peak changes in parameters caused mainly by force majeure circumstances at individual enterprises. Indeed, PJSC “LLRP”, PJSC “Odeskabel”, PJSC “Iskra”, PJSC “Azot” Sich”, and PJSC “KZR” demonstrated a sharp increase in net income (over 100%); then, this indicated the receipt of advance payments for large contracts at the beginning of the year, and not about the general trend of income growth. In subsequent quarters, the increase in net income did not exceed 40% due to its cumulative reflection in the financial statements of enterprises. This gives reason to exclude from consideration or additionally normalize extreme changes in individual parameters at the second stage of the regression analysis, provided that their sharp differences are compensated for in the following quarters (on average, linear deviations in the sum are insignificant). The same applies to the modeling of changes in the cost of production: in specific periods, enterprises purchased large batches of material resources or energy carriers, so in some quarters, there was a sharp increase in direct costs, and in others—their proportional reduction to the average annual value.

The operating profit of enterprises was also characterized by peak fluctuations associated with non-production activities (purchase and sale of financial assets, investments, currency transactions, etc.). On the one hand, enterprises in the east of Ukraine had significant violations of the rhythm of activity, but on the other hand, there was a situational increase in orders related to the production and repair of military equipment. Much more minor fluctuations characterized the market value of enterprises and the number of liquid assets; however, some sharp fluctuations of the parameters were also observed here. As for the relative indicators of the financial condition of enterprises (profitability of sold products, autonomy coefficient, total liquidity coefficient, return on capital), they are derived values that characterize several parameters at the same time; therefore, the requirements for the density of communication for them are lower by default.

After eliminating the influence of extreme changes in parameters, a repeated regression study was conducted, which demonstrated a significantly higher degree of density of the connection between the features (Appendix B, Table A34, Table A35, Table A36, Table A37, Table A38, Table A39, Table A40, Table A41 and Table A42). However, several regression equations still revealed the insufficient density of connections to conclude the impact of specific business indicators on indicators of the financial condition of enterprises. As a result of the comparison of regression equations at two stages, answers to the feasibility of further analysis were obtained (Table 5).

Table 5.

The results of the regression analysis of the relationship between indicators of the financial condition of enterprises from sets of business indicators of DTSP.

At the first stage of regression analysis, the highest degree of relationship density (R2 = 0.9999) was observed for indicators of net income (Y1), operating profit (Y3), and market value (Y5). A more or less significant degree of connection density is based on the cost of goods sold (Y2) with an indicator of R2 = 0.5260. According to the rest of the indicators, the coefficient of determination is R2 < 0.5, so the models based on the parameters of the volume of liquid assets (Y4), the profitability of sales (Y6), autonomy coefficients (Y7), total liquidity (Y8), and return on capital (Y9) are unsuitable for further work. As a result, increases in all relative indicators of financial stability in a “pure” form do not depend on gains in business indicators of DTSP. Relative indicators are significantly more affected by extreme but short-term changes in input parameters, which have different directions of change according to various factor characteristics.

After excluding from consideration all extreme values of the input data, related either to force majeure circumstances at the enterprises or to disproportionate changes in performance indicators in individual quarters, a much better result of the regression analysis was obtained. In particular, in addition to net income (Y′1), operating profit (Y′3), and market value (Y′5), the coefficients of determination for which remained at the level of R2 = [0.9988 ÷ 0.9999], the dependencies became significant: profitability of sold products (Y′6) with R2 = 0.9145; coefficient of autonomy (Y′7) with R2 = 0.7186; coefficient of total liquidity (Y′4) with R2 = 0.7048. Three indicators of financial condition did not reach a level of connection density sufficient for further analysis—the cost of goods sold, Y′2 with R2 = 0.365, volume of liquid assets, Y′4 with R2 = 0.3646, and return on capital (Y′9) with R2 = 0.4087.

If we are guided by the limiting criteria of aij ≥ 0.001 and R2 ≥ 0.667, then the regression models will remain significant for the economic evaluation of the implementation of diagnosed DTSP:

Based on the decoding of the variables (see Table 4), it is evident that the business indicators of consumer capital had the most significant impact on the financial results of enterprises—customers of DTSP (return on capital of client capital X11; effectiveness of marketing communications X13, X56; share of regular consumers X36; level of reliability of the customer base X55; level of quality of consumer capital X64); business indicators of management quality (staff load ratio X32; level of managers’ competencies X14, X83; share of operational time X16; long-term goal realization ratio X35, X84; effectiveness of the management subsystem in terms of labor productivity X51, X81; level of intellectual activity X15, X66, X76; correspondence of the number of managers to the normative X82), business indicators of the effectiveness of expenses for the development of intellectual capital (profitability of communication expenses X53; labor remuneration fund X54, X61; volume of social costs X72; costs for the communication system X73), and indicators of internal processes (coefficient of business automation of processes X31; capital return on projects x71; production rhythm X85; labor productivity X86).

It is worth noting that the input data were very heterogeneous because of the specifics of industrial enterprises, their territorial location, economic problems of recent years, military operations in Donbas, etc. Suppose a group of enterprises is selected more precisely, or it is about one enterprise. In that case, the mentioned models of Relationships (20)–(25) will have an even greater density of connections, and the coefficient of determination of regression models excluded from consideration will increase significantly. Thus, we argue the practical significance of the developed methodology of cross-selection of business indicators for the study of relationships between the results of implemented DTSP and the current financial results of enterprises. Similar multifactor regression models can be built to diagnose the impact of smartization at the stages of development and implementation of project solutions. The results of comparing the forecast regression values of indicators with their actual changes may well become the basis for adjusting the process and tools of DTSP.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

We consider the following developments as the most important results of this study:

- –

- A two-level graphical and analytical model for diagnosing the results of the implementation of DTSP (Figure 2), which allows for taking into account the interests of the project participants regarding the choice of diagnosis methods and techniques for identifying alternative sets of business indicators for each object of influence of the smartization project, to establish economic and non-economic criteria for evaluating the effectiveness of consulting, as well as perform monitoring of indicators and automated processing of diagnostic results to regulate deviations from the optimal values of project results. At the first level, sustainable relationships between the project effectiveness parameters of DTSP and the financial results of the customer enterprise are identified and described. At the second stage of the economic evaluation of the implementation of diagnosed DTSP, alternative models of the relationship of key parameters of enterprises’ financial state with sets of DTSP results are formed either by objects of influence or by crucial business indicators with a universal purpose. Conducted research and calculations show that in most cases, the density of communication between parameters is not high; therefore, it is advisable to form an economic–mathematical model for optimizing the implementation of diagnosed DTSP, which will be able to reconcile the costs of implementing the project solutions with the requirements for minimizing deviations of the actual values of business indicators from the planned and at the same time ensure the slightest possible disturbances in the rhythm of production. The formed economic–mathematical model contains three equivalent functions of the goal: F1(x)—minimization of uncovered costs for the design, implementation and maintenance of the smartization project; F2(y)—minimization of negative deviations of the actual values of business indicators from the planned ones; F3(z)—depreciation of violations production rhythms in the process of implementing the smartization project, which in the general formulation of the problem have the same significance; therefore we can use the scheme of uniform optimization. This model can be used at any stage of the smartization project. Based on it, conclusions can be drawn regarding the effectiveness of the implementation of the entire project and its individual stages, objects, or elements. The advantage of this model is the possibility of its decomposition, that is, a division into separate parts with the possibility of introducing additional restrictions or, conversely, reducing the level of requirements for some of them;

- –

- A matrix for selecting indicators for diagnosing the results of the implementation of DTSP for industrial enterprises (Table 2), which showed its effectiveness when tested at industrial enterprises;

- –

- Simulation modeling of the impact of a smartization project on the performance of industrial enterprises was carried out (based on the hypothesis that these enterprises will develop stably even without smartization within the limits of the increases in indicators that they demonstrated in previous periods). The influence of external environmental factors is excluded, and the deviations in demand, prices, exchange rates, and the consequences of state regulation are neglected. In such conditions, a computer simulation was carried out, which involved reproducing the impact of real DTSP of PJSC “Odeskabel” and PJSC “LLRP” on the input data of the other five enterprises in the same time intervals.

6. Limitations of this Study

For clarity of presentation of the results and ease of approbation of this study, the authors set certain limitations:

- –

- Definition of smartization as a process in its essence;

- –

- Management of the smartization process is defined as a project management process, that is, one that has a clear time frame, resources, executors, etc.;

- –

- The smartization project is carried out by a third-party organization (not by the enterprise itself) for an industrial enterprise.

Therefore, if there are other conditions (considering smartization as a phenomenon or the company carrying out smartization on its own), then it will be necessary to make corrections both in the methodology and assessment indicators and to conduct an approbation once again.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. and M.B.; Methodology, I.B., Y.M. (Yuliia Malynovska) and M.B.; Validation, I.B., S.M., Y.M. (Yuliia Malynovska), M.B., M.S. and Y.M. (Yuriy Malynovskyy); Formal analysis, S.M. and M.S.; Investigation, S.M. and Y.M. (Yuliia Malynovska); Resources, Y.M. (Yuriy Malynovskyy); Data curation, Y.M. (Yuliia Malynovska), M.B. and M.S.; Writing—original draft, Y.M. (Yuliia Malynovska) and M.B.; Writing—review & editing, I.B., M.S. and Y.M. (Yuriy Malynovskyy); Supervision, I.B.; Project administration, I.B. and Y.M. (Yuriy Malynovskyy). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

This study analyzed publicly available datasets. The data can be found here: https://databank.worldbank.org (accessed on 15 March 2022), http://www.ukrstat.gov.ua (accessed on 15 March 2022), https://saee.gov.ua (accessed on 15 March 2022). Other data were collected by the authors. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Input data for computer modeling of the impact of implemented consulting projects on the activities of other machine-building enterprises.

Table A1.

Balance indicators regarding the structure of enterprise assets, thousand UAH.

Table A1.

Balance indicators regarding the structure of enterprise assets, thousand UAH.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance Sheet Assets | Non-Current Assets | Intangible Assets | Current Asset | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 245,002 | 247,574 | 247,968 | 268,576 | 131,864 | 131,500 | 130,340 | 134,035 | 4312 | 4357 | 4488 | 4740 | 113,138 | 116,074 | 117,628 | 134,541 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 1,093,358 | 1,109,748 | 1,108,564 | 1,117,976 | 139,584 | 141,252 | 144,281 | 144,885 | 13,978 | 14,520 | 15,218 | 15,332 | 953,774 | 968,496 | 964,283 | 973,091 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 21,444,785 | 23,528,546 | 25,235,330 | 25,245,657 | 6,066,133 | 6,142,107 | 6,288,825 | 6,852,489 | 1800 | 1782 | 5705 | 5266 | 15,378,652 | 17,386,439 | 18,946,505 | 18,393,168 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 419,589 | 422,159 | 431,580 | 434,835 | 79,859 | 78,443 | 80,564 | 80,229 | 785 | 748 | 756 | 762 | 339,730 | 343,716 | 351,016 | 354,606 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 518,966 | 497,832 | 528,238 | 530,632 | 312,197 | 311,966 | 311,813 | 333,823 | 215,829 | 215,843 | 215,894 | 240,025 | 206,769 | 185,866 | 216,425 | 196,809 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 337,973 | 336,390 | 332,448 | 329,975 | 300,954 | 300,745 | 300,912 | 309,999 | 1392 | 1392 | 1253 | 1253 | 37,019 | 35,645 | 31,536 | 19,976 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 1,068,497 | 1,066,798 | 1,069,577 | 1,069,979 | 924,458 | 924,980 | 925,948 | 927,017 | 1200 | 1236 | 1249 | 1199 | 144,039 | 141,818 | 143,629 | 142,962 |

Table A2.

Balance indicators regarding the structure of enterprises’ liabilities, thousand UAH.

Table A2.

Balance indicators regarding the structure of enterprises’ liabilities, thousand UAH.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance Sheet liabilities | Own Capital | Long-Term Liabilities | Current Liabilities | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 245,002 | 247,574 | 247,968 | 268,576 | 153,283 | 141,103 | 132,795 | 131,230 | 826 | 670 | 662 | 393 | 90,893 | 105,801 | 114,511 | 136,953 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 1,093,358 | 1,109,748 | 1,108,564 | 1,117,976 | −294,938 | −297,955 | −285,970 | −273,887 | 111,068 | 113,189 | 113,189 | 116,781 | 1,277,228 | 1,294,514 | 1,281,345 | 1,275,082 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 21,444,785 | 23,528,546 | 25,235,330 | 25,245,657 | 14,128,146 | 15,517,954 | 16,500,510 | 16,342,312 | 1,257,610 | 4,199,314 | 4,176,924 | 3,376,012 | 6,059,029 | 3,811,278 | 4,557,896 | 5,527,333 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 419,589 | 422,159 | 431,580 | 434,835 | 324,205 | 324,205 | 324,205 | 324,205 | 786 | 759 | 795 | 771 | 94,598 | 97,195 | 106,580 | 109,859 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 518,966 | 497,832 | 528,238 | 530,632 | 414,570 | 405,708 | 428,102 | 452,871 | 681 | 692 | 692 | 637 | 103,715 | 91,432 | 99,444 | 77,124 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 337,973 | 336,390 | 332,448 | 329,975 | 304,453 | 293,214 | 290,549 | 290,090 | 415 | 1605 | 1800 | 1992 | 33,105 | 41,571 | 40,099 | 37,893 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 1,068,497 | 1,066,798 | 1,069,577 | 1,069,979 | −415,928 | −428,458 | −436,190 | −447,158 | 205,259 | 204,869 | 206,171 | 207,377 | 1,279,166 | 1,290,387 | 1,299,596 | 1,309,760 |

Table A3.

Indicators of financial results of enterprises, thousand UAH.

Table A3.

Indicators of financial results of enterprises, thousand UAH.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Income from Product Sales | Cost of Goods Sold | Gross Profit | Net Profit | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 27,356 | 59,413 | 82,628 | 116,924 | 26,425 | 59,522 | 83,638 | 178,490 | 931 | −109 | −1010 | −61,566 | −11,158 | −22,979 | −33,083 | −35,944 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 115,984 | 235,959 | 408,887 | 526,259 | 107,998 | 203,187 | 355,287 | 428,836 | 7986 | 32,772 | 53,600 | 97,423 | −3195 | −10,958 | −16,352 | −20,931 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 2,111,134 | 5,058,087 | 7,541,346 | 10,496,206 | 747,833 | 1,809,703 | 2,915,451 | 4,220,240 | 1,363,301 | 3,248,384 | 4,625,895 | 6,275,966 | 310,665 | 1,279,660 | 1,860,610 | 1,955,441 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 113,085 | 197,750 | 312,287 | 514,113 | 98,580 | 166,095 | 253,811 | 407,132 | 14,505 | 31,655 | 58,476 | 106,981 | 6618 | 23,098 | 42,610 | 51,504 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 28,690 | 73,445 | 146,267 | 205,106 | 22,450 | 60,493 | 121,056 | 168,047 | 6240 | 12,952 | 25,211 | 37,059 | 896 | 1456 | 18,988 | 21,652 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 7811 | 14,803 | 21,636 | 29,421 | 5738 | 11,847 | 28,774 | 28,394 | 2073 | 2956 | −7138 | 1027 | −3081 | −10,610 | −12,375 | −13,234 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 59,852 | 105,787 | 155,190 | 223,545 | 60,198 | 108,284 | 163,457 | 235,873 | −346 | −2497 | −8267 | −12,328 | −599,124 | −613,248 | −694,941 | −666,757 |

Table A4.

Indicators of the structure of functional costs of enterprises, thousand UAH.

Table A4.

Indicators of the structure of functional costs of enterprises, thousand UAH.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administrative Expenses | Sales Expenses | Labor Costs | Deductions for Social Events | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 8878 | 16,885 | 24,424 | 33,745 | 226 | 434 | 552 | 833 | 16,669 | 31,765 | 45,332 | 64,402 | 3667 | 6988 | 9973 | 14,168 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 7668 | 15,861 | 23,681 | 30,216 | 5237 | 9668 | 14,580 | 21,236 | 17,945 | 37,985 | 54,510 | 71,688 | 3948 | 8357 | 11,992 | 15,771 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 248,238 | 508,166 | 752,166 | 1,052,515 | 58,858 | 98,352 | 245,153 | 378,887 | 444,220 | 879,171 | 1,362,583 | 1,835,975 | 97,728 | 193,418 | 299,768 | 403,915 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 10,259 | 21,689 | 30,457 | 41,975 | 3038 | 6648 | 8970 | 12,535 | 33,158 | 65,884 | 95,702 | 132,289 | 7295 | 14,494 | 21,054 | 29,104 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 3457 | 7160 | 11,307 | 15,241 | 724 | 1536 | 2370 | 3283 | 9119 | 20,322 | 32,680 | 46,326 | 2006 | 4471 | 7190 | 10,192 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 1188 | 2493 | 3077 | 3781 | 223 | 499 | 732 | 926 | 1198 | 2579 | 3238 | 3816 | 264 | 567 | 712 | 840 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 14,491 | 29,212 | 43,578 | 60,246 | 1068 | 2267 | 3522 | 4686 | 17,442 | 33,689 | 52,247 | 70,291 | 3837 | 7412 | 11,494 | 15,464 |

Table A5.

Indicators of the structure of management costs of enterprises, thousand UAH.

Table A5.

Indicators of the structure of management costs of enterprises, thousand UAH.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expenditures on R&D | Expenses for Professional Development | Expenses for Communication Needs | Expenditures on Strategic Projects | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 1412 | 2698 | 3187 | 7345 | 223 | 468 | 621 | 942 | 661 | 1618 | 2610 | 3031 | 164 | 201 | 222 | 231 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 6308 | 12,607 | 18,932 | 28,901 | 2309 | 4608 | 7801 | 8506 | 6204 | 10,608 | 16,007 | 23,290 | 2004 | 2208 | 3197 | 4398 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 42,308 | 99,702 | 163,923 | 240,955 | 23,051 | 52,087 | 84,707 | 122,922 | 46,601 | 92,608 | 166,038 | 217,084 | 3600 | 5207 | 9796 | 11,614 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 4191 | 7498 | 9880 | 11,591 | 2795 | 4292 | 7590 | 11,602 | 3308 | 4209 | 5000 | 6607 | 664 | 1000 | 1314 | 1500 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 850 | 2208 | 3609 | 5500 | 520 | 1705 | 2207 | 2500 | 1000 | 1607 | 2707 | 3124 | 138 | 200 | 220 | 230 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 293 | 520 | 1404 | 1492 | 50 | 320 | 720 | 1000 | 160 | 550 | 670 | 790 | 60 | 90 | 99 | 111 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 3795 | 6607 | 10,607 | 16,701 | 1895 | 2208 | 3000 | 4095 | 1198 | 2000 | 2100 | 4501 | 160 | 674 | 998 | 1307 |

Table A6.

Indicators of the number of personnel, persons.

Table A6.

Indicators of the number of personnel, persons.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Number of Employees | The Average Number of Managers | The Average Number of Engineering and Technical Personnel | The Average Number of Active Employees | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 1297 | 1319 | 1293 | 1249 | 320 | 320 | 309 | 310 | 350 | 340 | 342 | 333 | 109 | 110 | 111 | 109 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 1598 | 1595 | 1693 | 1695 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 400 | 420 | 419 | 430 | 431 | 200 | 172 | 190 | 200 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 27,080 | 27,089 | 27,206 | 26,920 | 4609 | 4602 | 4608 | 4612 | 6298 | 6345 | 6391 | 6408 | 1309 | 1408 | 1504 | 1303 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 2012 | 2045 | 2087 | 2056 | 320 | 321 | 330 | 331 | 420 | 430 | 440 | 432 | 120 | 130 | 140 | 150 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 1100 | 1102 | 1109 | 1110 | 207 | 199 | 200 | 201 | 270 | 260 | 262 | 264 | 100 | 101 | 103 | 99 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 89 | 92 | 91 | 89 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 17 | 20 | 19 | 20 | 18 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 13 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 2900 | 2902 | 2905 | 2911 | 499 | 499 | 489 | 500 | 699 | 699 | 702 | 711 | 300 | 288 | 295 | 299 |

Table A7.

The total cost price of shares of functional costs of enterprises, %.

Table A7.

The total cost price of shares of functional costs of enterprises, %.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of Administrative Costs | The Share of Sales Costs | Share of Labor Costs | Share of Social Deductions | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 33.60 | 28.37 | 29.20 | 18.91 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 63.08 | 53.37 | 54.20 | 36.08 | 13.88 | 11.74 | 11.92 | 7.94 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 7.10 | 7.81 | 6.67 | 7.05 | 4.85 | 4.76 | 4.10 | 4.95 | 16.62 | 18.69 | 15.34 | 16.72 | 3.66 | 4.11 | 3.38 | 3.68 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 33.19 | 28.08 | 25.80 | 24.94 | 7.87 | 5.43 | 8.41 | 8.98 | 59.40 | 48.58 | 46.74 | 43.50 | 13.07 | 10.69 | 10.28 | 9.57 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 10.41 | 13.06 | 12.00 | 10.31 | 3.08 | 4.00 | 3.53 | 3.08 | 33.64 | 39.67 | 37.71 | 32.49 | 7.40 | 8.73 | 8.30 | 7.15 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 15.40 | 11.84 | 9.34 | 9.07 | 3.22 | 2.54 | 1.96 | 1.95 | 40.62 | 33.59 | 27.00 | 27.57 | 8.94 | 7.39 | 5.94 | 6.06 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 20.70 | 21.04 | 10.69 | 13.32 | 3.89 | 4.21 | 2.54 | 3.26 | 20.88 | 21.77 | 11.25 | 13.44 | 4.59 | 4.79 | 2.48 | 2.96 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 24.07 | 26.98 | 26.66 | 25.54 | 1.77 | 2.09 | 2.15 | 1.99 | 28.97 | 31.11 | 31.96 | 29.80 | 6.37 | 6.84 | 7.03 | 6.56 |

Table A8.

The full cost price of shares of management costs of enterprises, %.

Table A8.

The full cost price of shares of management costs of enterprises, %.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Share of R&D Expenditures | The Share of Qualification Costs | Share of Communication Costs | The share of Costs for Strategic Projects | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 5.34 | 4.53 | 3.81 | 4.12 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 2.50 | 2.72 | 3.12 | 1.70 | 0.62 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.13 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 5.84 | 6.20 | 5.33 | 6.74 | 2.14 | 2.27 | 2.20 | 1.98 | 5.74 | 5.22 | 4.51 | 5.43 | 1.86 | 1.09 | 0.90 | 1.03 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 5.66 | 5.51 | 5.62 | 5.71 | 3.08 | 2.88 | 2.91 | 2.91 | 6.23 | 5.12 | 5.70 | 5.14 | 0.48 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.28 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 4.25 | 4.51 | 3.89 | 2.85 | 2.84 | 2.58 | 2.99 | 2.85 | 3.36 | 2.53 | 1.97 | 1.62 | 0.67 | 0.60 | 0.52 | 0.37 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 3.79 | 3.65 | 2.98 | 3.27 | 2.32 | 2.82 | 1.82 | 1.49 | 4.45 | 2.66 | 2.24 | 1.86 | 0.61 | 0.33 | 0.18 | 0.14 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 5.11 | 4.39 | 4.88 | 5.25 | 0.87 | 2.70 | 2.50 | 3.52 | 2.79 | 4.64 | 2.33 | 2.78 | 1.05 | 0.76 | 0.34 | 0.39 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 6.30 | 6.10 | 6.49 | 7.08 | 3.15 | 2.04 | 1.84 | 1.74 | 1.99 | 1.85 | 1.28 | 1.91 | 0.27 | 0.62 | 0.61 | 0.55 |

Table A9.

The total number of shares of employees of different groups of enterprises, %.

Table A9.

The total number of shares of employees of different groups of enterprises, %.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Share of Workers in the Total Number of Workers | The Share of Managers in the Total Number of Employees | The Share of Engineering and Technical Personnel in the Total Number of Employees | The Share of Active Workers in Their Total Number | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 48.34 | 49.96 | 49.65 | 48.52 | 24.67 | 24.26 | 23.90 | 24.82 | 26.99 | 25.78 | 26.45 | 26.66 | 8.40 | 8.34 | 8.58 | 8.73 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 48.69 | 48.65 | 50.97 | 50.97 | 25.03 | 25.08 | 23.63 | 23.60 | 26.28 | 26.27 | 25.40 | 25.43 | 12.52 | 10.78 | 11.22 | 11.80 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 59.72 | 59.59 | 59.57 | 59.06 | 17.02 | 16.99 | 16.94 | 17.13 | 23.26 | 23.42 | 23.49 | 23.80 | 4.83 | 5.20 | 5.53 | 4.84 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 63.22 | 63.28 | 63.10 | 62.89 | 15.90 | 15.70 | 15.81 | 16.10 | 20.87 | 21.03 | 21.08 | 21.01 | 5.96 | 6.36 | 6.71 | 7.30 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 56.64 | 58.35 | 58.34 | 58.11 | 18.82 | 18.06 | 18.03 | 18.11 | 24.55 | 23.59 | 23.62 | 23.78 | 9.09 | 9.17 | 9.29 | 8.92 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 55.06 | 58.70 | 57.14 | 60.67 | 22.47 | 20.65 | 20.88 | 19.10 | 22.47 | 20.65 | 21.98 | 20.22 | 11.24 | 7.61 | 13.19 | 14.61 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 58.69 | 58.72 | 59.00 | 58.40 | 17.21 | 17.20 | 16.83 | 17.18 | 24.10 | 24.09 | 24.17 | 24.42 | 10.34 | 9.92 | 10.15 | 10.27 |

Table A10.

Indicators of the use of labor resources.

Table A10.

Indicators of the use of labor resources.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salary Intensity of Production | Labor Productivity, Thousand Hryvnias/Individual | Coefficient of Intellectual Activity | Staff Turnover Rate | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 21.09 | 24.30 | 17.95 | 27.46 | 0.041 | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.041 | 0.0118 | 0.0085 | 0.0099 | 0.0170 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 72.58 | 75.22 | 102.14 | 69.25 | 0.039 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.037 | 0.0108 | 0.0009 | 0.0307 | 0.0006 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 77.96 | 108.79 | 91.28 | 109.76 | 0.059 | 0.07 | 0.073 | 0.062 | 0.0025 | 0.0002 | 0.0022 | 0.0053 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 56.21 | 41.40 | 54.88 | 98.16 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.048 | 0.042 | 0.0086 | 0.0082 | 0.0103 | 0.0074 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 26.08 | 40.61 | 65.66 | 53.01 | 0.039 | 0.05 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.0015 | 0.0009 | 0.0032 | 0.0005 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 87.76 | 76.00 | 75.09 | 87.47 | 0.046 | 0.04 | 0.045 | 0.047 | 0.0111 | 0.0169 | 0.0054 | 0.0110 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 0.29 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 20.64 | 15.83 | 17.01 | 23.48 | 0.049 | 0.04 | 0.042 | 0.045 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.0005 | 0.0010 |

Table A11.

Indicators of intensity of use of working time.

Table A11.

Indicators of intensity of use of working time.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Share of Operative Time of Managers | Staff Utilization Ratio | Coefficient of Information Loading | Qualification Ratio of Managers | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.94 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.93 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 0.76 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.72 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.75 | 0.71 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.88 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 0.89 | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 0.69 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.84 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.85 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 0.79 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.76 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.73 | 0.22 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.91 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.91 |

| PJSC “KBVP” | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.94 |

Table A12.

Time spent on working with consumers, person-hours.

Table A12.

Time spent on working with consumers, person-hours.

| Enterprises | The Value of Indicators | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Work with Consumers | Average Time of Communication with the Client | Response Time to Information Requests | Complaint Response Time | |||||||||||||

| t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | t1 | t2 | t3 | t4 | |

| PJSC “LLRP” | 2179 | 1885 | 1754 | 1942 | 45.5 | 43.8 | 49.2 | 47.5 | 7.9 | 8.3 | 9.7 | 9.2 | 25.8 | 25.3 | 27.2 | 29.8 |

| PJSC “Odeskabel” | 4177 | 4258 | 4048 | 4335 | 19.3 | 20.8 | 24.2 | 22.3 | 14.2 | 15.3 | 14.3 | 15.2 | 16.8 | 15.2 | 15.3 | 16.8 |

| PJSC “Iskra” | 32,618 | 31,490 | 30,628 | 31,482 | 185.2 | 193.8 | 180.6 | 199.1 | 33.6 | 35.4 | 42.8 | 41.2 | 71.3 | 75.5 | 76.3 | 76.3 |

| PJSC “Azot” | 1835 | 1664 | 1794 | 1875 | 23.8 | 33.9 | 29.5 | 30.5 | 16.2 | 16.8 | 15.2 | 15.8 | 20.2 | 22.6 | 24.5 | 23.6 |

| PJSC “Radar” | 1068 | 1028 | 1164 | 1189 | 20.3 | 23.9 | 20.3 | 24.8 | 10.2 | 12.5 | 14.5 | 13.1 | 15.8 | 16.2 | 17.5 | 17.9 |

| JSC “Ekvator” | 665 | 528 | 655 | 694 | 43.3 | 36.8 | 39.4 | 40.1 | 15.2 | 18.8 | 16.3 | 17.7 | 26.6 | 28.5 | 30.1 | 29.3 |