Abstract

Corporate sustainability evolved in line with the advancement of the concept of sustainable development; thus, it is constituted as a strategy to respond to social and environmental problems. In this context, universities are understood as complex organizations, positioned as a key mechanism for delivering the sustainable development of society. This research aimed to analyze whether the strategic elements of Chilean state universities integrate components of sustainable development. For this purpose, qualitative research was undertaken through a documentary analysis of the strategic plans of the 18 Chilean state universities, focusing analysis on their strategic elements: their mission, vision and strategic institutional objectives. The results revealed that all universities mention at least one concept associated with one of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in their strategic guidelines. They mainly focused on ‘Quality Education’ (SDG 4) and ‘Build resilient infrastructure, promoting inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation’ (SDG 9). Also, the results allow us to visualize how universities address corporate sustainability issues through their strategic plans.

1. Introduction

Universities are complex organizations par excellence, positioned as key drivers for human progress, which means they constituted a critical leverage mechanism for promoting the sustainable development of society [1,2,3]. Sustainable development implies considering the three interdependent environmental, economic, and social dimensions [4]; and developed into a normative concept known as corporate sustainability [5] at the level of organizational systems (institutions and companies).

The need for sustainable development places new demands on higher education, leading, according to Maassen [6], to the redefinition of the social contract between universities and society. This generated several tensions in these educational entities, one of which is linked to the growing expectations regarding their role in global transformations towards sustainable development, which requires internal organizational transformations in what are often conservative institutions [7].

Assuming corporate sustainability in universities implies aligning their mission with the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Within this ambition, University Corporate Governments (UCG) should play a central role in preventing conflict between university objectives and the three dimensions of sustainable development [8]. In the case of the UCG of Chilean state universities, there are no scientific reports on how they address sustainable development in their strategies.

The simultaneous achievement of environmental, economic, and social sustainability aspects implies tensions that must be addressed by University Corporate Governments (Higher Council, in the case of Chilean state universities). Indeed, there is a need to reconcile the guidelines declared by the institution and the quality of the information used to make decisions in these areas.

In this context, the main objective of this paper was to analyze whether the strategic elements of Chilean state universities embrace the components of sustainable development. For this purpose, qualitative research was carried out through a documentary analysis of the strategic plans of the 18 Chilean state universities, focusing analysis on the strategic elements: their mission, vision, and institutional strategic objectives.

2. Theoretical and Contextual Framework

2.1. Corporate Sustainability: A Way of Assuming Sustainable Development

Sustainable development (SD) evolved steadily in conceptual terms [9], founded on practice and strengthened with theory. Its development can be divided into the incipient period (before 1972), the molding period (1972–1987), and the development period (since 1987) [10,11]. The 1987 Brundtland report, entitled ‘Our Common Future’, officially introduced the idea of sustainable development and recognized the interconnectedness of ecological, economic, and social systems [12]. For these systems to be sustainable, they must economically satisfy consumption habits using available resources without compromising future needs; socially, improving people’s quality of life; and ecologically, preserving natural resources [13].

The concept of corporate sustainability evolved in line with the advancement of the concept of sustainable development [14]. Organizations have been operating, and many still operate, to create shareholder wealth and use philanthropy to acquire social legitimacy and prestige. However, philanthropy does not create value or cover society’s costs associated with the organization’s actions, nor does it lead to sustainable efficiency. Subsequently, companies realized that surviving and thriving in the emerging world requires incorporating an expanded set of multi-stakeholder responsibilities into their core value propositions. Finally, there is a move towards sustainability as a competitive advantage. Given this level of evolution, at present corporate sustainability should provide short-term competitive solutions, as well as contribute to the preservation, maintenance and enhancement of natural and human resources that may be needed in the future [15,16].

This new perspective on sustainability is the result of three drivers [17]: (i) increased stakeholder awareness and expectations; (ii) increased transparency; and (iii) decreased resource and environmental degradation. This enables companies to create shared value for all their stakeholders.

In short, corporate sustainability is constituted as a strategy to respond to social and environmental problems. To achieve this, the degree to which an organization integrates environmental, economic social, and other governance-related factors into its operations, as well as the impact they have on society, must be measured and reported [18,19,20,21,22].

2.2. Corporate Sustainability and Universities

Achieving sustainable development is a major societal challenge. University institutions have a role to play in this regard, especially through developing competencies in their students to be effective change agents for sustainability [23,24]. Furthermore, universities that design their operations according to sustainability standards, increase overall economic well-being, and contribute to society’s sustainable development [25]. The creation of smart technologies developed by universities is a good example for achieving sustainable development as long as they positively impact on economic, environmental, and social sustainability. According to Saunila et al. [26], the relationship between intelligent technologies and economic sustainability occurs directly, while the relationship with environmental and social sustainability must be mediated by corporate sustainability.

Taking ownership of sustainable development creates value for organizations and corporate sustainability concerns operationalize it [27]. The debate on sustainable development and organizational change increasingly gained momentum in higher education. However, the progress of higher education towards sustainability remains an enigma [28,29]. This is because there is little conceptual clarity of corporate sustainability, which creates confusion for its’ implementation; furthermore, it generates ineffective and arbitrary practices in complex organizations, such as universities. However, this does not disqualify the importance of corporate sustainability in universities; on the contrary, it reinforces the need to contribute to increasing understanding of corporate sustainability in such organizations [30,31,32,33,34]. There is agreement in the literature that tensions occur when an organization’s objectives conflict with the three dimensions of sustainable development, namely ecological, social, and economic [35]. In line with the above, six tensions related to the sustainability of Finnish universities have been reported [7]:

- Academic leadership and managerial legitimacy;

- Regional political tensions and university profile;

- Political power over the university system;

- The change of academic work and profession;

- Academic autonomy and the role of the State;

- The future role of the university institution.

In practice, higher education institutions must consider economic, ecological, and social impacts in pursuing sustainable operations [36]. Taking on corporate sustainability implies that universities develop more sustainable organizational practices [7,37]. This involves strategic decisions that must be assumed by the universities’ UCG. The first way to verify the appropriation of sustainable development and the implementation of a corporate sustainability model is if it is reflected in the strategic plans, especially in their mission, vision, and strategic objectives, since the implementation of sustainable development, more than a theory, is a call to action [38]. A second way is to verify whether it is effectively embodied through the university’s activities; this requires the preparation of sustainability reports that can be audited and the construction of corporate sustainability indicators or indices; the latter should make it possible to verify the real impacts of institutions that claim to be organizations embracing responsibility for promoting sustainable development [39,40,41,42]. Lopez and Martin’s [43] report on Spanish schools and universities found that 80% of them did not assume sustainable development in their mission statement; while Nardo, Codreanu, and Roberto [44] provided similar results regarding compliance in the strategic plans of Italian public universities on the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) proposed by the United Nations in 2015 [45].

Considering the case of Chilean state universities, it can be observed that the University Corporate Governance is the Higher Council (HC) or Board of Directors, and according to the legislation, it is responsible for ‘defining the general development policy and the strategic decisions of the institution, ensuring compliance, in accordance with the mission, principles, and functions of the university’ (Law No. 21.094, 2018, art. 13) [46]. The HC ideally should contribute to the creation of value by monitoring and providing strategic advice to the management team (rector, pro-rector, vice-rectors), and propitiating access to resources that enable the strategic plan for institutional development to be implemented [47]. The HC is an important actor in the decision-making process and, in formal terms, is the most central elected or appointed strategic body at the institutional level [48].

In any case, greater clarity is required regarding the HC concerning its roles, leadership, and capacity to guarantee the quality of the academic activities undertaken by the universities [49]. In the case of the HCs of Chilean state universities, there are no scientific reports on their practices, performance, nor the dynamics of their internal processes, except for their composition and structure. The incorporation of stakeholders into university governance has been reflected in changes in the composition of the HCs, which has ensured greater collaboration and engagement of stakeholders [50].

By incorporating different stakeholders in HCs, organizations are expected to be more likely to be responsive to broader societal interests, which is critical as the existence of a state university can be justified through its relationships with stakeholders [51].

2.3. Characterization of Chile’s State Universities

Article 4 of Law No. 21.091 enacted by the Ministry of Education in 2018 [46] states that the Chilean higher education system is of mixed provision and is composed of two subsystems: technical professional centers and universities. The first is made up of three types of institutions: professional institutes (IP) and private technical training centers recognized by the State and state-owned technical CFTs. The second system is made up of state universities created by law, non-state universities belonging to the Council of Rectors of Chilean Universities (CRUCH), and private universities recognized by the State, totaling 58 institutions according to the Chilean Higher Education Information System (SIES). Of the 58 universities identified, only 18 are state-owned.

By definition, universities are created by law to fulfil the functions of teaching, research, artistic creation, innovation, extension, and outreach and engagement with the environment and the territory, to contribute to strengthening democracy, the sustainable and comprehensive development of the country, and to progress society in the various domains of knowledge and culture [46]. In pursuing this mission, universities must contribute to satisfy the general needs and interests of society, collaborating, as an integral part of the State, in all those policies, plans, and programs that contribute to the cultural, social, territorial, artistic, scientific, technological, economic, and sustainable development of the country, at national and regional levels, with an intercultural perspective. Table 1 presents a list and associated information on the 18 state universities in Chile, ordered by their year of creation.

Table 1.

List of the strategic plans of Chilean State Universities reviewed and their period of execution.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data

The theoretical background of this research centers around questions of how higher education institutions should channel sustainable practices and their dissemination. On the one hand, one way of verifying the appropriation of sustainable development at the institutional level is whether it is reflected in the strategic plans of higher education institutions. Thus, this research aimed to analyze whether the strategic elements of Chilean state universities integrate the components of sustainable development. For this purpose, we reviewed what is established in the institutional strategic plans through their strategic elements (mission, vision, and strategic objectives).

For analysis, organization, and presentation of the information, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals adopted by the United Nations are used as proxies for the elements that make up corporate sustainability [53,54]. In this way, information will be displayed on these topics regarding the closeness, inclusion and/or participation of the universities houses of study with the SDGs.

To analyze the universities according to what they establish in their strategic elements, the institutional strategic plans of the 18 universities of the Consortium of State Universities of Chile (CUECH) were reviewed, focusing on studying the missions, visions, and strategic objectives of each one of them (strategic elements). The strategic plans were obtained from the universities’ official web pages, which can constitute reliable resources for obtaining information about the organizations [55,56,57,58]. More specifically, the plans are documents (digital files) that were downloaded from the official websites. The list of universities and the periods covered in each strategic plan were presented in Table 1.

3.2. Method for the Analysis of Missions, Visions, and Strategic Objectives

Once each institution’s missions, visions, and strategic objectives were identified, the next step was to link them to the Sustainable Development Goals. It is worth noting that the adoption of the SDGs by the United Nations took place in 2015. While we operated under the hypothesis that the institutions consider the SDGs in the discussion and development of their strategic plans, some institutions were not influenced by the SDGs. In the case of the Universidad de La Frontera, its strategic plan came into effect two years before that date; in addition, it should also be borne in mind that the universities of La Serena, Playa Ancha, Talca, Metropolitana de Ciencias de la Educación, and Tecnológica Metropolitana began to implement their plans in 2016, so they would likely have been less directly influenced by the SDGs.

To develop the link between that which is established in the institutional strategic elements and in the Sustainable Development Goals, concepts and core ideas advocated for in the SDGs were located within the documents of the universities. To this end, the following procedure was carried out:

- (a)

- Related concepts and core ideas were identified for each SDG, as shown in Table 2. These concepts and ideas were identified through a discourse analysis [59,60] of what was established in the document ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ published in 18 September 2015 [46], which details the contents of each Sustainable Development Goal and its targets. With regard to Table 2, it is necessary to emphasize that the ideas shown here correspond to a translation of the words searched for in Spanish, because the plans of all the universities are written in that language.

Table 2. Concepts and core ideas sought in the missions, visions, and strategic objectives of universities.

Table 2. Concepts and core ideas sought in the missions, visions, and strategic objectives of universities. - (b)

- The strategic plans were obtained from the universities’ official web pages. Subsequently, from every plan, Missions, Visions, and Strategic Objectives were identified.

- (c)

- Thereafter, a search was made in the texts of each mission, vision, and strategic objectives of the 18 Chilean state universities, to establish the institutions’ levels of relationship, linkage, or commitment to the issues covered in the United Nations 2030 Agenda. If a related concept or key idea of an SDG was present in any strategic element, it was assigned a value of 1 in each university’s mission, vision, and strategic objective. This information is presented through three matrices (tables) and a summary table that display whether the different SDGs have been included or not in the institutional strategic elements.

Subsequently, a search was conducted in the texts of each mission, vision, and strategic objectives of the 18 Chilean state universities, to establish the institutions’ levels of relationship, linkage, or commitment to the issues covered in the United Nations 2030 Agenda. This information is presented through a summary table and three matrices that display whether the different SDGs have been included or not in the institutional strategic elements.

3.3. Similarity between Mission, Vision, and Strategic Objectives

When an SDG was identified within one of the university’s strategic elements, it was assigned a value of 1; if no SDG was identified, a value of zero was assigned. Three tables/matrices were created for the mission, vision, and strategic objectives.

It was likely that an SDG would not be identified in the mission but rather be referenced in the vision or strategic objectives. Thus, to understand whether the SDG matrices of each strategic element are similar from a global perspective, the index proposed by Mancilla, Soza-Amigo, and Ferrada [61] was adopted to identify the similarity between pairs of matrices. Originally, this index was called Temporal Similarity Index and was proposed to analyze the similarity of the productive structure and the switching of a territory in two periods of time; however, given the nature of the calculation, it enables comparing any two matrices, with the condition that both matrices must have the same dimension. For this work, the index was termed the Similarity Index (Equation (1)). By performing the calculation, we can determine how similar the two matrices are; in case they are completely equal, the value is 100, while if they are completely different, the value is 0.

where ABS, absolute value; M1 refers to the SDG matrix of Mission, Vision, or Strategic Goals; M2 refers to the SDG matrix of Mission, Vision, or Strategic Goals; Vij refers to the cell value of the row of variable i (in this case, it will be a university) and the column of variable j (which, in this case, refers to one of the SDGs); n refers to the number of rows; k refers to the number of columns.

4. Results

4.1. Mission and SDGs

Considering the sector (or industry) in which the universities operate (educational service), it is possible to partially anticipate results obtained from Table 3. The 18 state universities analyzed mention concepts related to SDG 4 ‘Quality Education’ and SDG 9 ‘Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure’; the latter is linked to generating new knowledge, innovation in scientific areas, and technological improvements.

Table 3.

Analysis of the missions of Chilean state universities according to each Sustainable Development Goal.

By contrast, no university mentioned SDG 1 ‘End Poverty’, SDG 6 ‘Clean Water and Sanitation’, SDG 7 ‘Affordable and Clean Energy’, SDG 12 ‘Responsible Production and Consumption’, SDG 13 ‘Climate Action’, SDG 14 ‘Undersea Life’, or SDG 15 ‘Life of Terrestrial Ecosystems’ in their missions.

Finally, it was possible to analyze the number of SDGs present in the institutional missions of each university. Universidad Arturo Prat took first place, mentioning concepts linked to eight SDGs in total; while Universidad de Playa Ancha and Universidad de Santiago de Chile with six SDGs each came in second; and Universidad del Bío-Bío mentioning five SDGs in its mission was third. It should be noted that all universities mentioned at least two SDGs.

4.2. Vision and SDGs

Focusing the analysis on the vision put forward by the institutions, the pattern observed above was repeated. The data in Table 4 show that the SDGs most frequently mentioned in the visions, correspond again to SDGs 4 and 9, the latter being the one with the highest frequency. The use of the words ‘development’, ‘research’, and ‘sustainable’ give reference to SDG 9 on ‘Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation’, and confirms the previous conclusion on the universities’ focus on scientific and technological innovation.

Table 4.

Analysis of visions of Chilean state universities according to each Sustainable Development Goal.

On the other hand, Table 4 also reflects that a total of eleven SDGs were not mentioned in the vision of any university, and the number of SDGs present in the institutional visions decreased compared to those used in the missions. Universidad de Los Lagos was in first place, whose vision mentions concepts and ideas that encapsulate five SDGs; in second place was the Universidad de Valparaíso and the Universidad de Santiago de Chile with four SDGs mentioned apiece; and in third are eight universities that mention three SDGs. All universities mentioned at least one SDG concept in their visions.

4.3. Strategic Objectives and SDGs

The last analysis related to the strategic elements and SDGs was carried out on the strategic objectives and concluded that the pattern observed in the two previous analyses was repeated. Table 5 shows that SDG 4 and 9, again, were mentioned by all the universities in the study. However, SDG 17 ‘Partnerships to achieve the goals’ was also referenced, where universities referred to regional and international sustainable development through providing financial and technological resources.

Table 5.

Analysis of strategic objectives of Chilean state universities related to each Sustainable Development Goal.

Again, a pattern similar to the previous analyses was observed concerning the SDGs that were not mentioned by the institutions: eight SDGs were not referenced which, again, included SDG 1, SDG 6, SDG 8, SDG 12, SDG 13, and SDG 14.

Finally, Table 5 shows the number of SDGs used in the strategic objectives of state universities, positioning Universidad de Valparaiso in the first place, with six SDGs mentioned; in second place were Universidad de Santiago de Chile and Universidad de Talca, each mentioning five SDGs; and in third place, seven universities mentioned four SDGs. In this analysis, all universities mentioned at least three SDG concepts.

4.4. Strategic Elements and SDGs

A global analysis of the SDGs present in the missions, visions, and strategic objectives is presented in Table 6, allowing for a general analysis of the presence or absence of the SDGs in the universities’ strategic elements. For example, no university explicitly incorporated SDG 1 related to Poverty (reduction; access to basic resources; policies; programs, eradication) in its strategic elements. In the case of SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), two (11%) universities incorporated it in their mission and none in their vision and objectives.

Table 6.

Percentage of strategic elements of Chile’s state universities that are linked to the SDGs.

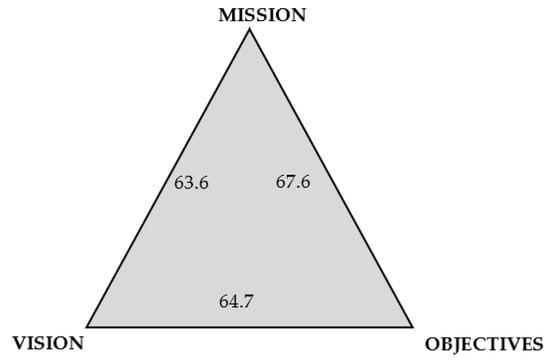

Previous analyses revealed some degree of similarity between the SDGs and the strategic elements of Chilean state universities. The Similarity Index explained in the methodology section was calculated to quantify this similarity. Figure 1 shows the similarity data between the institutions’ missions, visions, and strategic objectives, where a figure close to 100 is higher similarity and close to 0 is lower similarity. The results showed a high similarity between the three variables, with a greater relationship between the missions and the strategic objectives, exhibiting a closeness of 67.6. On the other hand, the lowest visible closeness is between what the missions and visions state, showing 63.6.

Figure 1.

Similarity index between missions, visions, and strategic objectives. Source: Elaborated by the authors.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Corporate Sustainability in universities requires the alignment of the institution’s main strategic guidelines with sustainable development, so that the University’s Corporate Governance makes decisions that incorporate them into the organization’s objectives and their implementation. However, this is not the only relevant dimension, since the information they receive is also necessary to make decisions that contribute to this process.

In this sense, the strategic guidelines, mission, vision, and strategic objectives declared by the universities and their relationship with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) espoused by the United Nations, were analyzed.

In general, all universities mentioned in their strategic guidelines at least one concept associated with one of the 17 SDGs, concentrating mainly on SDGs 4 and 9—which are related to quality education (4) and to industry, innovation, and infrastructure. The mission defined by the different universities all incorporate elements of SDG 4, and SDG 9 in almost all of them. This concentration showed that universities are positioned in the education industry, but they also incorporated aspects such as diversity, equity, quality, and lifelong learning; in the same sense, they revealed elements associated with scientific research and innovation, by incorporating SDG 9. Therefore, what the universities revealed in their definitions of their mission are a focus on areas that directly impact academic work, namely, teaching, extension, outreach and engagement, and research. On the other hand, regarding the similarity index, it was stronger between the mission and the strategic objectives, which was coherent, considering that the strategic objectives are the operationalization of the mission.

In relation to the vision, most universities incorporated elements of SDGs 4, 9, and 17, which is consistent with the analysis of the mission. However, SDG 17, which refers directly to sustainability, was added. It is noteworthy that in the vision, there is a higher percentage of linkages with industry, innovation, and infrastructure than with quality education. This could apply to the challenges that universities face in terms of greater links with industry to provide sustainability in innovation projects and scientific production, areas that are lacking in institutions in general and that need to be strengthened by bringing the university closer to industry.

Regarding the strategic objectives declared by the universities, all 18 universities explicitly declared aspects related to SDGs 4, 9, and 17, from which it can be inferred that higher education institutions associate with sustainability in explicitly less abstract strategic terms. Concerning the similarity index, no major substantial differences were observed in the relationship of the three strategic guidelines, which could be interpreted as a certain alignment among them.

Disclosure of SDG compliance information at the university level is still in its early stages; moreover, the literature on the subject is patchy [54,62,63]. Therefore, sustainability reports or the participation of institutions in university rankings with a focus on the SDGs have been used as a way to obtain a general idea of their commitment to this issue [64,65]. In the Latin American context, one study analyzed the integration of Sustainable Development Goals in Colombian public universities [66], which was measured through a questionnaire given to individuals. In agreement with the present research, this study confirmed the relevance of institutional development plans as the instrument used by universities to articulate the United Nations 2030 agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals.

UCG managers must make decisions based on the strategic guidelines provided by universities. In addition to the above, they must account for how they are taking charge of sustainable development at the strategic levels through the dissemination of information. Regarding the disclosure of information, this must comply with the principle of materiality, which is when the contents are useful for the decisions made by stakeholders.

Accessing the strategic elements of the universities has been a consequence of the disclosure of information by the institutions. This allowed us to identify the presence or absence of an SDG within the available information provided.

The related concepts and keywords that were used in this work can be employed to analyze other institutions and make similar comparisons. Furthermore, the similarity index proved to be a simple and appropriate tool for calculating and interpreting and can, therefore, be helpful in further work.

The results present insights that could be discussed in further studies, which includes the finding that not all SDGs are addressed by universities. Thus, the question arises as to which SDGs should be effectively addressed by universities. In other words, which SDGs should be taken on board in their mission aspects. In this regard, it seems important to consider the appropriate context (local, national, or international) for universities, as there may be institutions whose context requires them to make a more significant contribution in some dimensions and less in others.

This work also presented some limitations. Firstly, our analysis used only cross-sectional data and did not consider the evolution of the plans. A second limitation was that it did not analyze the degree of compliance with the strategic elements. In other words, many organizations are moving towards declaring or writing a mission, vision, and strategic objective. However, the degree of compliance with these elements must be evaluated. A third aspect was that this research only considered state-owned universities and did not include private universities. This is mainly explained by the fact that some of these institutions do not disclose their strategic plans and are not obliged to do so; by contrast, all state-owned universities disclose their strategic plans.

In terms of future research, our findings could be deepened by analyzing university sustainability reports, since they can account for university activities where more SDGs are identified. At the same time, it should be determined whether these sustainability reports provide material information, i.e., information that effectively allows the different stakeholders of the universities to make decisions. Moreover, these reports should be auditable. Therefore, the challenge is proposing appropriate indicators to measure corporate sustainability in universities.

Some remaining challenges relate to carrying out a comparative analysis over time, thus observing how the strategic elements of the universities evolved. In this way, it would be possible to analyze how institutions expand or incorporate (or not) some other SDGs to contribute to sustainable development.

Finally, other aspects or gaps should be further investigated, including the heterogeneity in the participation of stakeholders; the contents to be disclosed (economic, social, environmental, or governance); the role played by teaching and research; the evaluation tools, reflected in indicators, indexes, or standards; the variables that affect their disclosure; the opportunity in which they should be disclosed; and the impacts on the organization and stakeholders [23,67,68,69,70].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.-R. and F.G.-C.; data curation, W.S.; formal analysis, J.A.-R. and C.M.; funding acquisition, J.A.-R.; methodology, J.A.-R., C.M. and W.S.; supervision, J.A.-R.; validation, C.M.; writing—original draft, J.A.-R., C.M., W.S. and I.D.-S.; writing—review and editing, J.A.-R. and C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Científico, Tecnológico y de Innovación Tecnológica (FONDECYT 1220740—Project “Sostenibilidad corporativa y el rol de los consejos superiores de las universidades estatales: importancia de la materialidad de la información”) from Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile (ANID).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used (the strategic plans) were obtained from the websites of Chilean state universities. This is public information, and anyone can get the information by accessing the websites.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Instituto Interuniversitario de Investigación Educativa de Chile (IESED) for its support and for developing this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ganga-Contreras, F. The bureaucratic flipper in Universities. Interciencia J. 2017, 42, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Ganga-Contreras, F.; Pedraja-Rejas, L.; Quiroz-Castillo, J.; Rodriguez-Ponce, E. Organizational Isomorphism (OI): Brief theoretical approaches and some applications to higher education. Rev. Espac. 2017, 38, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Findler, F.; Schönherr, N.; Lozano, R.; Stacherl, B. Assessing the impacts of higher education institutions on sustainable development-An analysis of tools and indicators. Sustainability 2018, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCED. World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Hahn, T.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L.; Figge, F. Tensions in Corporate Sustainability: Towards an Integrative. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maassen, P. A New Social Contract for Higher Education? In Higher Education in Societies; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattu, A.; Cai, Y. Tensions in the sustainability of higher education- the case of Finnish universities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Diaz, P.; Polanco, J.; Escobar-Sierra, M.; Leal, W. Holistic integration of sustainability at universities: Evidences from Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 305, 127145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer-Raniga, U.; Treloar, G. FORUM: A Context for Participation in Sustainable Development. Environ. Manag. 2000, 26, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Han, L.; Yang, F.; Gao, L. The evolution of sustainable development theory: Types, goals, and research prospects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wass, T.; Hugé, J.; Verbruggen, A.; Wright, T. Sustainable Development: A Bird’s Eye View. Sustainability 2011, 3, 1637–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinakou, E.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Van Petegem, P. Exploring the concept of sustainable development within education for sustainable development: Implications for ESD research and practice. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2019, 21, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askoy, F.; Bayram, N. Evaluation of sustainable happiness with sustainable development goals: Structural equation model approach. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsalis, T.; Malamateniou, K.; Koulouriotis, D.; Nikolaou, E. New challenges for corporate sustainability reporting: United Nations’ 2030 Agenda for sustainable development and the sustainable development goals. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1617–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmine, S.; De Marchi, V. Reviewing Paradox Theory in Corporate Sustainability toward a Systems Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2022, 184, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.J.; Curi, D.; Bandeira, A.M.; Ferreira, A.; Tomé, B.; Joaquim, C.; Santos, C.; Góis, C.; Meira, D.; Azevedo, G.; et al. Literature Review and Theoretical Framework of the Evolution and Interconnectedness of Corporate Sustainability Constructs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanda, U.; Shrotryia, V. Corporate sustainability: The new organizational reality. Qual. Res. Organ. Manag. 2021, 16, 464–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranvgrahaning, A.; Donovan, J.; Topele, C.; Masli, E. Corporate sustainability Assessments: A systematic literature review and conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasal, S.; Al Mamun, A.; Wahab, S.; Mohiuddin, M. Host-Country characteristics, corporate sustainability, and the mediating effect of improved knowledge: A study among foreign MNCs in Malaysia. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2017, 25, 328–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beske, F.; Haustein, E.; Lorson, P. Materiality analysis in sustainability and integrated reports. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 11, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrobback, P.; Meath, C. Corporate sustainability governance: Insight from the Australian and New Zealand port industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 255, 120280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, A.; Costa, R.; Levialdi, N.; Menichini, T. Materiality analysis in sustainability reporting: A tool for directing corporate sustainability towards emerging economic, environmental and social opportunities. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2019, 25, 1016–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez, S.; Uruburu, A.; Moreno, A.; Lumbreras, J. The sustainability report as an essential tool for the holistic and strategic vision of higher education institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 207, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesselbarth, C.; Schaltegger, S. Educating change agents for sustainability e learnings from the first sustainability management master of business administration. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 62, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, E.; Harder, M. What lies beneath the surface? The hidden complexities of organizational change for sustainability in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunila, M.; Nasiri, M.; Ukko, J.; Rantala, T. Smart technologies and corporate sustainability: The mediation effect of corporate sustainability strategy. Comput. Ind. 2019, 108, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Serafeim, G.; Yoow, A. Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. Account. Rev. 2016, 91, 1697–1724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, M.; Bormann, I.; Kummer, B.; Niedlich, S.; Rieckmann, M. Sustainability Governance at Universities: Using a Governance Equalizer as a Research Heuristic. High. Educ. Policy 2018, 31, 491–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, A.; Macdonald, A.; Dandy, E.; Valenty, P. The state of sustainability reporting at Canadian universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antolín-López, R.; Delgado-Ceballos, J.; Montiel, I. Deconstructing corporate sustainability: A comparison of different stakeholder metrics. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136 Pt A, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, E.; Ponomarenko, T.; Tesovskaya, S. Key corporate sustainabilty assessment methods for coal companies. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobo-Hernandez, C.; Jaimes-Valdez, M.A.; Ochoa-Jimenez, S. Benefits, challenges and opportunities of corporate sustainability. Management 2021, 25, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meseguer-Sánchez, V.; Abad-Segura, E.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Molina-Moreno, V. Examining the Research Evolution on the Socio-Economic and Environmental Dimensions on University Social Responsibility. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazienza, M.; de Jong, M.; Schoenmaker, D. Clarifying the Concept of Corporate Sustainability and Providing Convergence for Its Definition. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T.; Figge, F.; Pinkse, J.; Preuss, L. Trade-Offs in Corporate Sustainability: You Can’t Have Your Cake and Eat It. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2010, 19, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hueske, A.-K.; Guenther, E. Multilevel barrier and driver analysis to improve sustainability implementation strategies: Towards sustainable operations in institutions of higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, M.; Khalil, U.; Khan, Z. Sustainability in higher education: What is happening in Pakistan? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2021, 22, 681–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Puig, N.; Sanz-Casado, E. Sustainability practices in Spanish higher education institutions: An overview of status and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docekalova, M.; Kocmanová, A. Composite indicator for measuring corporate sustainability. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 61, 612–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engert, S.; Baumgartner, R. Corporate sustainability strategy-bridging the gap between formulation and implementation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 822–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngay, E.; Chau, D.; Lo, C.; Lei, C. Design and development of a corporate sustainability index platform for corporate sustainability performance analysis. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 34, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazienza, M.; de Jong, M.; Schoenmaker, D. Why Corporate Sustainability Is Not Yet Measured. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Y.; Martin, W. University Mission Statements and Sustainability Performance. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2018, 132, 341–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardo, M.; Codreanu, G.; Roberto, F. Universities’ Social Responsibility through the Lens of Strategic Planning: A Content Analysis. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ares70d1_en.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Ley Chile—Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional. LEY 21094 Sobre Universidades Estatales. Available online: https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1119253 (accessed on 25 March 2023).

- Abello, J.; Mancilla, C. Multi-Theoretical analysis of university corporate governance on information disclosure. Rev. Opción 2018, 34, 358–392. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, I.M. The role of the governing board in higher education institutions. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2001, 7, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, J. Taking it on board: Quality audit findings for higher education governance. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2007, 26, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langrafe, T.; Barakat, S.; Stocker, F.; Boaventura, J. A stakeholder theory approach to creating value in higher education institutions. Bottom Line 2020, 33, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donina, D.; Meoli, M.; Paleori, S. The new institutional governance of Italian state universities: What role for the new governing bodies? Tert. Educ. Manag. 2015, 21, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directorio Instituciones Educación Superior. Ministry of Education of Chile. Available online: https://educacionsuperior.mineduc.cl/directorio-instituciones-ed-superior/ (accessed on 12 May 2023).

- Pérez-Esparrels, C. Impacto de los objetivos de desarrollo Sostenible (ods) en las instituciones de Educación superior: Un análisis de las Universidades españolas en el Times Higher Education university impact ranking. In Rentabilidad Individual y Social de la Educación Superior; Studia XXI, Fundación Europea Sociedad y Educación, Santander Universidades: Madrid, Spain, 2020; pp. 59–78. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/696179 (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- De La Poza, E.; Merello, P.; Barberá, A.; Celani, A. Universities’ Reporting on SDGs: Using THE Impact Rankings to Model and Measure Their Contribution to Sustainability. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, V.; Raghupathi, W. Leveraging the Web for Corporate Sustainability Disclosure. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. (IRMJ) 2020, 33, 24–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatanartıran, O. Goals and Practices in Corporate Sustainability Communication: Doğuş Otomotiv Case. Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi Halkla İlişkiler Sürdürülebilirlik Özel Sayısı 2022, 39, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Cañizares, P. “Corporate Sustainability” or “Corporate Social Responsibility”? A Comparative Study of Spanish and Latin American Companies’ Websites. Bus. Prof. Commun. Q. 2021, 84, 361–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menicucci, E. Exploring forward-looking information in integrated reporting: A multi-dimensional analysis. J. Appl. Account. Res. 2018, 19, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erlingsson, C.; Brysiewicz, P. A hands-on guide to doing content analysis. Afr. J. Emerg. Med. 2017, 7, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancilla, C.; Soza-Amigo, S.; Ferrada, L.M. A methodological proposal for intertemporal analysis of labor commutation: The case of Chilean Patagonia. Estud. Demográficos Urbanos 2021, 36, 149–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáez de Cámara, E.; Fernández, I.; Castillo-Eguskitza, N. A Holistic Approach to Integrate and Evaluate Sustainable Development in Higher Education. The Case Study of the University of the Basque Country. Sustainability 2021, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanellato, G.; Tiron-Tudor, A. Toward a Sustainable University: Babes-Bolyai University Goes Green. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Iorio, S.; Zampone, G.; Piccolo, A. Determinant Factors of SDG Disclosure in the University Context. Adm. Sci. 2022, 12, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorani, G.; Di Gerio, C. Reporting University Performance through the Sustainable Development Goals of the 2030 Agenda: Lessons Learned from Italian Case Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Campo, C.H.; Ico-Brath, D.; Murillo-Vargas, G. Integración de los objetivos de desarrollo sostenible (ODS) para el cumplimiento de la agenda 2030 en las universidades públicas colombianas. Formación Univ. 2022, 15, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasi, S.; Rahdari, A.; Rexhepi, G. Developing a sustainability reporting assessment tool for higher education institutions: The University of California. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 672–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrán, M.; Andrades, F.; Herrera, J. An analysis of university sustainability reports from the GRI database: An examination of influential variables. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019, 62, 1019–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepasi, S.; Braendle, U.; Rahdari, A. Comprehensive sustainability reporting in higher education institutions. Soc. Responsib. J. 2019, 15, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzner, A.; Stucken, K. Reporting on sustainable development with student inclusion as a teaching method. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).