Abstract

Tourism is the economic sector most heavily influenced by COVID-19, and it has suffered unprecedented losses. The competitiveness and resilience of the tourism industry have recently become a topic of great concern for global stakeholders. A series of ambitious recovery strategies have been announced by countries to rebuild the tourism industry, that aim to make “smokeless industry” more resilient and sustainable. The objective of this study is to evaluate and rank the effectiveness of nine recovery strategies in the post-COVID-19 period for Vietnam’s tourism industry. A combined model of the Best–Worst Method (BWM) and the Group Best Worst Method (GBWM), an efficient tool using the multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach, is used to rank the tourism solutions. The assessment process is carried out by six stakeholder groups considered decision makers, including tourism operators, enterprises, scholars, employees, residents, and tourists. In the context of Vietnam, the most influential tourism recovery strategy is using innovative tourism business models (ST2), which is a solid step forward in utilizing potential resources, meeting current tourism needs, and adapting to natural changes. The model results reflect that the tourism model’s restructuring is necessary to provide new types of experiences and entertainment suitable for the new tourism context. The findings illustrate that the priority of strategies depends on the perception of decision-makers, levels of involvement in the tourism industry, and local conditions. The study has contributed a theoretical framework for tourism recovery solutions and decision support in the post-pandemic stage. The model can be applied to other countries worldwide in improving tourism performance or assisting in decision-making for similar issues.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 outbreak has significantly impacted tourism, making it the worst-hit industry. Despite the pandemic having been ongoing for over three years, the tourism industry has yet to reach its pre-pandemic state of 2019. Recent data from UNWTO reveal that over 900 million international tourists traveled in 2022, but this number still remains 37% below the 2019 levels.

Numerous studies have suggested various strategies and approaches for reviving the economy since the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, Wan et al. (2022) recommend employing public–private partnership governance models [1], while Bulchand-Gidumal (2022) proposed developing novel business models for tourism, promoting demand in local markets, training tourism workers, and implementing economic measures [2]. Similarly, Dash and Sharma (2021) suggested that governments should support the ailing tourism sector, encourage local handicrafts and artwork, establish standard operating procedures, and utilize digital media [3]. Additionally, Goh (2021) suggests transitioning from mass tourism to high-value tourism [4]. These suggestions provide valuable insights for policymakers and managers to select suitable solutions based on the specific circumstances of their region. However, selecting effective and prioritized solutions is not an easy task, as it requires the identification of various influencing factors and consultation with numerous stakeholders. The multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) method is a tool that can aid in this process.

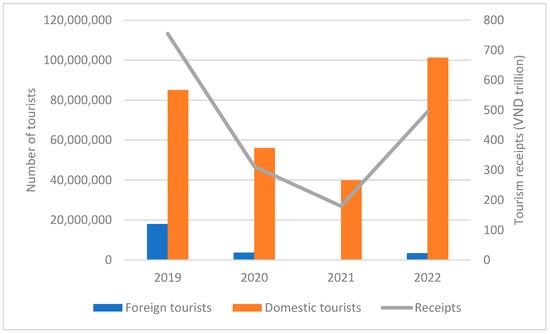

Vietnam is increasingly becoming an attractive destination in the world, with tourism as a spearhead economic sector due to the high rate of tourism revenue, making an outstanding contribution to the country’s GDP growth. Moreover, tourism has contributed to preserving and promoting the value of cultural heritage and natural resources, promoting the image and affirming Vietnam’s position in development and international integration [5]. In the post-COVID-19 period, restoring this potential economy is considered urgent. Starting from November 2021, the Vietnamese government launched a pilot program allowing international visitors to enter the country, which has been fully operational since May 2022 [6]. Under the program, foreign visitors are exempt from COVID-19 testing and quarantine procedures. However, despite these efforts, Vietnam’s tourism industry has not fully recovered from the pandemic’s consequences. In 2022, the number of international visitors was just over 4.4 million, which represents only 19% of the figure recorded in 2019; the industry’s revenue was only 65% of the amount generated in 2019, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Vietnam’s tourist quantity and revenue 2019–2022. Source: prepared by the author based on data from the Vietnam National Administration of Tourism (VNAT), 2023.

Tourism recovery in the post-pandemic period is vital for raising Vietnam’s economy, improving people’s lives, and renewing the tourism industry. However, selecting a feasible solution that matches the trend in the recovery phase is a challenging step. The study aims to assist in the most effective strategic decision-making to restore Vietnam’s tourism industry after COVID-19. This research utilizes an MCDM approach, specifically the Best–Worst Method, to assess and prioritize post-COVID-19 tourism revival strategies in Vietnam. The study employs an extended version of BWM, the Group Best–Worst Method (GBWM), which considers six stakeholder groups: tourism operators, enterprises, scholars, employees, tourists, and residents. A questionnaire was administered to 36 representatives from these stakeholder groups. It is the first study considering multiple stakeholder perspectives to develop practical tourism solutions through a multi-criteria decision-making model. Thus, the study has provided a theoretical framework to support decision-makers and managers in evaluating and choosing a tourism recovery strategy. Focusing on the Vietnamese context, the author has proposed a list of tourism reviving plans to contribute documents on tourism development in the new conditions towards sustainability. Additionally, the findings have practical implications for policymakers in Vietnam and other developing countries facing similar challenges.

The paper’s subsequent sections comprise a comprehensive review of the literature on BWM and measures for post-crisis tourism recovery. Section 3 outlines the methodology used to calculate the weights and strategies’ priority. Section 4 outlines the case study, while Section 5 reports on the study’s results. The paper concludes with Section 6, which includes a discussion of the results and the paper’s overall conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Strategies for Post-COVID Tourism Recovery

The worldwide tourism sector has been significantly affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, as the world slowly recovers from the pandemic, industry is actively seeking ways to revive itself. Numerous academics have conducted research on this subject, as indicated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of strategies for post-COVID tourism recovery.

One of the primary strategies proposed to recover tourism activities post-pandemic is to prioritize health and safety measures [2,3,7,11]. This includes implementing social distancing measures, providing adequate personal protective equipment, and promoting contactless technologies such as mobile check-ins and cashless transactions. According to Sigala (2020), enhancing public trust in the tourism industry’s health and safety measures can help rebuild travel confidence [15].

Another highly suggested strategy for tourism revival is to implement sustainable tourism practices [3,4]. The pandemic has forced tourism into sustainable development, assisting in reducing the environmental impact of tourism activities, promoting responsible tourism, and supporting local communities [3,16,17].

Besides this, domestic tourism has emerged as a potential solution for tourism revival post-COVID-19 to boost the tourism industry’s recovery due to international travel restrictions [2,7,12].

Evidently, technology has played a crucial role in tourism revival post-COVID-19 [3,8,10,12,13,14]. The use of digital platforms, such as virtual tours, online booking systems, and mobile apps, can help to promote contactless travel and enhance the customer experience. According to Seshadri, Kumar, and Ndlovu (2023), digital technology, such as virtual reality, can enhance supplier–customer relationships and influence tourism product choices [14].

In addition, numerous experts view collaboration and cooperation between stakeholders in the tourism industry as viable approaches essential for tourism revival post-COVID-19 [1,2]. Although this action is not directly linked to post-COVID-19 management, it has been frequently emphasized that joint efforts among all entities and stakeholders in the destination will be crucial for successfully navigating the crisis, as stated by Yeh (2021) [18].

2.2. Best–Worst Method Application

The MCDM method is popular for use in decision-making problems due to the continuous development of new tools to support the fastest and most optimal results. It allows for dealing with complex issues based on quantitative, qualitative, and possibly contradictory factors [19,20]. The appropriate tool selection depends on the information, input data, and method parameters [21]. The paper aims to score and prioritize the identified strategies in tourism restoration. The authors select the BWM method proposed by Rezaei [22] due to its capturing of human perceptions with fewer comparisons, simplifying the evaluation process, and increasing the research results’ accuracy [23]. According to an integer scale of 1–9, decision-makers make a pairwise comparison of the best criterion with the other, and compare another criterion with the worst criterion [24]. As a result, evaluation analysis becomes more efficient and more consistent, and allows comparisons with multiple criteria and decision-makers [21]. The BWM method has been widely applied in various fields, including in setting priorities for vaccine introduction [25], identifying strategies to tackle COVID-19 outbreaks [24], evaluating factors for intervention strategies in handling COVID-19 attacks [26], implementing clean hospital strategies [27], assessing supply chain issues affected by pandemic preventive initiatives [28], developing a resilience strategy to improve the agri-food industry after COVID-19 [29], and selecting the most efficient commercial practices for biomedical waste [30].

Many scholars have also used the BWM technique to clarify different tourism aspects, as shown in Table 2. A study on the ecotourism development strategy was carried out using the BWM method and strength–weakness–opportunity–threat (SWOT) analysis. The primary survey and expert evaluation are conducted through four main criteria and ten sub-criteria. The study results will significantly assist decision-makers in choosing the most appropriate strategy to enhance the ecological landscape value in parallel with tourism exploitation in Masouleh village, Iran [23]. Fadafan also studied another aspect of ecotourism development by assessing Iran’s natural resources’ quality. After fitting nine main criteria into two anthropogenic and natural clusters, the experts investigated ecotourism destinations using the BWM method. The study shows Iran has a high biological value with great potential for exploiting the ecotourism model [31]. In addition, tourism combined with sport is another attractive mode because of the variety of recreational activities and the promotion of local culture. Yang integrated the Bayesian Best–Worst Method (Bayesian BWM) and the Visekriterijumska Optimizacija I Kompromisno Resenje (VIKOR) technique to evaluate the productivity and prioritization of sports tourism destinations in Taiwan. Considering visitor experience and health factors, this framework provides a valuable reference for governments and regulators towards sustainable sports tourism development [32]. Moreover, the combination of Bayesian BWM and grey Preference Ranking Organization Method for Enrichment Evaluations based on Aspiration Level (grey PROMETHEE-AL) models has been applied in medical tourism, bringing high economic value for businesses. A set of four key factors and nineteen sub-criteria was constructed to estimate the performance and feasibility of medical tourism operators [33].

Table 2.

The summary of the BWM method’s application in the tourism sector.

Moreover, the BWM technique is used in various problems of hospitality and tourism management. Kumar used BWM and VIKOR to rank potential airports for sustainability and environmental friendliness based on green performance evaluation criteria [34]. Jian Wu has developed an evaluation framework including the RFMP model, BWM, and TOPSIS method to assist travelers in choosing the most satisfactory hotel [38]. A study of tourism planning initiatives and development was accomplished by Yamagishi [35]. It is considered a complex group decision-making process, and the author has combined the PROMETHEE II and BWM methods to determine the most prioritized initiative. In the development of sustainable farm tourism, Absalon has established sustainability indicators and assessed farm performance by systematically approaching the fuzzy Delphi-fuzzy BWM-fuzzy SAW methods [36]. Furthermore, Haqbin developed the most suitable solution among twenty-one solutions to restore tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic for small and medium enterprises using the BWM approach [37].

3. Methodology

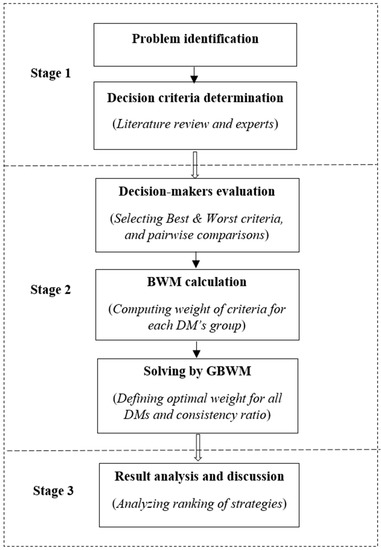

The Group Best–Worst Method (GBWM) [39] is one of the tools of the MCDM approach, extending from the Best–Worst Method (BWM) [22] to rank criteria by collecting opinions from a group of experts. In this study, the author has combined BWM and GBWM methods to determine the priority of tourism recovery strategies. First, the preliminary criteria weights for each assessment group are implemented by the BWM technique. Next, GBWM has been used to identify the best strategy from all decision-makers in six stakeholder groups. Figure 2 illustrates the proposed model’s process below.

Figure 2.

Research methodology structure.

Step 1: Problem identification

After defining the problem, a list of decision criteria is established through literature reviews and expert opinions.

Step 2: Decision-maker evaluations

The decision-makers are asked to evaluate the decision criteria based on the scale of linguistic terms from 1 = “Equally important” to 9 = “Extremely important” in Table 3.

Table 3.

The BWM terminology scale for pairwise comparisions.

Step 3: Modeling and solving using the BWM and GBWM method

In this stage, the decision-maker chooses the best and worst criteria. Then, the comparison is implemented, including comparing between the best criterion and other criteria, and between other criteria and the worst criterion, as follows in Equations (1) and (2).

where OBj is the best criterion compared to the other criterion j, and Ojw is the other criteria j compared to the worst criterion

OB = (OB1, OB2, OB3,…, OBn), Ɐ j = 1,2,…n

Ow = (O1W, O2W, O3W, …, OnW), Ɐ j = 1,2,…n

The optimal weights (W1*, W2*, …, Wn*) of each criterion are calculated using the GBWM model, presented in Equations (3)–(10).

Subject to

where

- WB is the weights of the most important criteria,

- WW is the weights of the least important criteria,

- is the weight of criterion j,

- is the inconsistency in pairwise comparisons obtained by the kth decision-maker.

The consistency of comparisons is checked by following , where is the preference for the best criterion over the worst criterion.

The consistency ratio for each decision-maker (CRk) and group decision-markers is estimated in Equations (11) and (12), respectively.

where is the weight given to the kth DM based on expertise level, CI is the consistency index values given in Table 4. The value of decreases as the consistency increases, and is entirely consistent.

Table 4.

Consistency index (CI).

4. Case Study

The COVID-19 outbreak has significantly affected Vietnam’s tourism sector. The nation implements stringent controls on the virus’s propagation, including travel restrictions and quarantine requirements, and these have led to a sharp decline in domestic and international tourism. According to the Vietnam National Administration of Tourism, in 2021, there were just 3500 foreign visitors to Vietnam, compared to almost 18 million in 2019. This represents a decline of 99.98%, which is a staggering drop. The decline in international visitors has also significantly impacted the tourism industry’s revenue. In 2019, Vietnam’s tourism industry generated total receipts of USD 31.2 billion, but in 2021, that figure dropped to just USD 7.4 billion, a decline of 76.2% [40].

The decline in tourism revenue has had a knock-on effect on the people who participate in tourism supply chains. Many workers have lost their jobs, and those still employed have seen their incomes significantly reduced. This has dramatically impacted people’s lives and the broader economy. The Vietnamese government has implemented a range of policies to boost the tourism sector, such as financial assistance for businesses and workers, and initiatives to promote domestic tourism. However, it may take some time for the industry to recover fully, and the ongoing global pandemic remains a significant challenge. Many scholars, policymakers, and social economists have proposed various solutions, strategies, and actions in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it is not feasible for governments to blindly adopt another country’s epidemic prevention strategy. Each country has unique economic, social, political, cultural, and capacity contexts that must be considered. Therefore, governments must prioritize and carefully select their strategies.

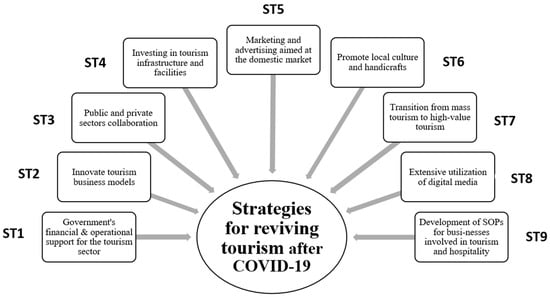

Since examining the relevant literature, we have identified over 30 solutions/strategies/actions for restoring the tourism sector after the COVID-19 pandemic. We then narrowed down the list to thirteen key criteria. Additionally, we consulted with industry experts in the Vietnamese context, such as business owners, tour operators, and university professors, to further refine the list. Finally, a list of nine criteria was formed, as shown in Figure 3, which is based mainly on studies by Bulchand-Gidumal (2022) [2], Dash and Sharma (2021) [3], Gossling et al. (2020) [41], and Wan et al. (2022) [1], regarding the recovery and change of the tourism perspective during the post-pandemic period. Each criterion is described in detail in Table 5.

Figure 3.

The proposed strategies for tourism revival after COVID-19.

Table 5.

The description of criteria for tourism recovery.

The data were collected from 36 samples comprising six groups: tourism operators, enterprises, scholars, employees, tourists, and residents. The scholars and residents groups were part of Ahmad et al.’s (2021) research [24], while the enterprises group was from Wang et al.’s (2022) study [26]. These selected groups were directly affected by the pandemic’s impact on tourism. As they come from diverse backgrounds, their post-pandemic tourism recovery strategiy assessments are expected to provide governments with realistic insights.

The Tourism operators group consists of Vietnam’s six largest travel service providers, namely Vietravel, Euro Travel, Saigon Tourist, BenThanh Tourist, Hanoi Tourist, and Dat Viet Tour. The enterprises group comprises restaurants, hotels, and entertainment establishments. The scholars group includes researchers and university lecturers in the tourism industry. The employees group consists of salaried individuals working in the tourism sector. The residents group comprises people living in Nha Trang city, one of the major tourist destinations affected by the pandemic. Finally, the tourists group consists of individuals who are enthusiastic about travel and have a high frequency of travel.

Representatives of different groups were given a questionnaire in three parts. The first part aimed to gather demographic information, while the second part inquired about the impact of the pandemic on individuals and/or their organizations. The third part asked respondents to rate the importance of specific criteria, choosing the most and least important and assigning relative levels to the strategies on a scale of 1–9. The research team flexibly used either online or face-to-face interviews, depending on favorable conditions. Finally, the criteria weights for each stakeholder group were calculated using the BWM solver software (Rezaei, 2015) [22].

5. Result Analysis

This study established groups of decision-makers representing stakeholders in the tourism sector, including scholars, enterprises, tourism operators, employees, residents, and tourists. The data were collected by constructing six mathematical models, with G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, and G6 corresponding to six stakeholder groups, and the weight k is considered equal in each group, as shown below. After the survey, the results contained 36 valid answers out of 40 responses, and each group consisted of six decision-makers. The variables of the proposed model are denoted as follows.

the weight of criterion j;

the set of decision-makers, j index for criteria;

the weight of decision-maker k;

: the inconsistency in pairwise comparisons obtained by the kth decision-maker.

5.1. Model for Scholars

The proposed model of the Scholars group is represented below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies used by scholars is demonstrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

The comparison of strategies used by scholars (DMs, D1–D6).

5.2. Model for Enterprises

The proposed model of the Enterprises group is represented below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies by enterprises is described in Table A1 (Appendix A).

5.3. Model for Tourism Operators

The proposed model of the Tourism Operators group is represented below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies by tourism operators is described in Table A2 (Appendix A).

5.4. Model for Employees

The proposed model of the Employees group is shown below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies by employees is described in Table A3 (Appendix A).

5.5. Model for Residents

The proposed model of the Residents group is descritbed below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies by residents is described in Table A4 (Appendix A).

5.6. Model for Tourists

The proposed model of the Tourists group is demonstrated below.

Subject to

The comparison of strategies by tourists is described in Table A5 (Appendix A).

5.7. Criteria Weights by Group

After solving the mathematical models of the six groups of stakeholders, the priorities of the strategies of each group are obtained, as shown in Table 7. These rankings are reliable in defining the consistency ratio, including CR, CI and ξ for each group, and CRG for the group, as presented in Table 8. The results show that all CRG values are acceptable, where the lowest value of consistency is for residents with CRG = 0.2321, and the highest consistent value is for tourism operators with CRG = 0.3571.

Table 7.

The strategies’ rankings by stakeholder group (G1–G6).

Table 8.

Consistency ratio (CR) for stakeholder groups (G1–G6).

5.8. The Final Ranking Criteria Weights

This step aims to consider the preferences of all groups together to determine the most productive strategy for tourism recovery [24,26]. After obtaining the importance level of the criteria in each group, the combined weights of criteria for all decision-maker groups are derived. A GBWM mathematical model is proposed below to estimate the overall weight of the strategy.

Subject to

λ1, λ2, λ3, λ4, λ5, and λ6 are the weights assigned to stakeholder groups, such as scholars (G1), enterprises (G2), gourism operators (G3), employees (G4), residents (G5), and tourists (G6), respectively. The values of all weights equal 1 (λ1 + λ2 + λ3 + λ4 + λ5 + λ6 = 1). For the reliability of rankings, sensitivity analysis is implemented with four different scenarios corresponding to the weights WSI, WSII, WSIII, and WSIV for each group, as shown in Table 9. These weights are generated based on the knowledge and expertise of each group in related fields combined with an understanding of COVID-19’s effects on the tourism industry. Thus, the group of tourism operators (G3) has the highest weight (λ1 = 0.35–0.4), and enterprises (G2) have the second highest weight (λ2 = 0.25–0.2) because of their expertise in tourism industry operations and management.

Table 9.

The four scenarios of weight set (WS) values (, , , ).

The final rankings of strategies are obtained by aggregating all the evaluations of six stakeholder groups, as shown in Table 10. In sum, “Innovative tourism business models” (ST2) is the most preferred strategy across four scenarios for restoring tourism after the COVID-19 pandemic. Next, “Promoting local culture and handicrafts” (ST6) and “Extensive utilization of digital media” (ST8) are other priority strategies to be considered for implementation. At the bottom of the rankings is “Government’s financial and operational support for the tourism sector” (ST1), “Development of SOPs for businesses involved in tourism and hospitality” (ST9), and “Investment in tourism infrastructure and facilities” (ST4). In summary, the model results show that the stakeholders’ opinions are relatively similar despite different functions and roles played in the tourism industry. Most decision-makers desire to innovate tourism models regarding destinations, environments, and tourism services in order to meet travel need changes. Development strategies for taking advantage of available resources from agriculture, traditional culture, and biodiversity with little investment are prioritized. Minimizing costs and rationally exploiting tourism activities will suit the challenging context, and greatly assist in recovering business activities after the pandemic.

Table 10.

The strategies’ rankings by weight sets (WSI–WSIV).

6. Discussion and Conclusions

6.1. Discussion

Tourism has been one of the most vulnerable economic sectors during the COVID-19 pandemic on account of isolating, and the ceasing of all entertainment and recreational activities [53]. The tourism industry’s unprecedented difficulties include declining market demand, businesses shutting down or changing actions, and workers losing their jobs or changing jobs [40]. According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), the global GDP lost USD 4.5 trillion and more than 60 million jobs in 2020 [54]. In the post-COVID-19 period, restoring the tourism industry has been essential, and entrepreneurs have faced significant challenges in finance and human resources. Therefore, all countries have been pursuing resilience by developing a sustainable development strategy and improving the competitiveness of their tourism industry.

In the case of Vietnam, the government is also developing policies to support tourism activities, and is setting up a new tourism product system in line with recent trends. However, choosing an appropriate and practical strategy is a complicated process as it directly affects resources and stakeholders’ interests. It is considered a multi-criteria decision-making problem, and the Best–Worst Method has become a widely used tool amongst scholars in recent times because of the advantages it offers in human cognitive comparison, and it allows the inclusion of the group of decision-makers. Therefore, the Group Best–Worst Method (GBWM) has been proposed to determine Vietnam’s most optimal strategy for tourism restoration. According to literature reviews and expert opinions, a set of nine potential strategies is established to outline practical actions for adapting and increasing current tourism demand, including governmental financial and operational support for the tourism sector (ST1), innovative tourism business models (ST2), public and private sector collaborations (ST3), investment in tourism infrastructure and facilities (ST4), marketing and advertising aimed at the domestic market (ST5), promoting local culture and handicrafts (ST6), transitioning from mass tourism to high-value tourism (ST7), the extensive utilization of digital media (ST8), and the development of SOPs for businesses involved in tourism and hospitality (ST9). The assessment process has been carried out by six groups of stakeholders related to the tourism industry: scholars (G1), enterprises (G2), tourism operators (G3), employees (G4), residents (G5), and tourists (G6).

At the initial stage, the evaluation process employs the BWM model to identify the most important strategies for each stakeholder group. In relaiton to their different points of view, perceptions, and degrees of involvement in tourism recovery, the assessments of each group are presented. Specifically, the scholars (G1) and tourists (G6) rated the innovative tourism business models (ST2) criteria as the most important. After the COVID-19 pandemic, tourists seek safe and secure travel destinations with health care systems, and favor experiencing nature and learning about local culture. Considering environmental and human factors, new tourism models will be a solid step forward in meeting current tourism needs and adapting to natural changes. With that in mind, academics are also studying new alternative tourism models that match this trend and ensure sustainable development, such as ecotourism, agritourism, and community tourism. In addition, promoting local culture and handicrafts (ST6) is the most important criterion for residents (G5). As they represent a unique cultural tourism resource, restoring traditional craft villages and local cultural activities such as festivals and cuisine creates favorable conditions for residents to increase their income, and promotes the local image after a long period of closure. For the groups of enterprises (G2) and tourism operators (G3), public and private sectors collaboration (ST3) is the most important element of a tourism recovery strategy. Businesses have suffered the most from the pandemic because of increased costs, as well as loss of revenue and labor, thus posing a massive obstacle in the recovery period. Cooperation for mutual development is necessary to raise competitiveness and diversify resources. Meanwhile, public–private partnerships based on financial support and reduced risks are leveraged to enhance the attractiveness of a destination in the region, increase productivity, and improve market efficiency. Finally, employees (G4) are the most interested in the extensive utilization of digital media (ST8) criteria. In the current technological era, digital transformation in tourism has become an inevitable trend, allowing employees to interact directly with each customer quickly, providing information and understanding their needs. Some new technologies are often applied in the digital transformation process, such as big data (Big Data), artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and virtual reality (VR).

In the next stage, GBWM is used to aggregate the assessments of the proposed strategy by all groups, and rank them. Different scenarios are generated to estimate the weight values given by stakeholders based on experience and involvement in the tourism sector. The final ranking results indicate that innovate tourism business models (ST2) represent the most important criterion across all stakeholders. It shows that tourists are increasingly choosing new types of experiences and entertainment, and the current concern of scientists and businesses is to restructure the tourism model. Many alternative forms of tourism have been established to attract tourists, such as ecotourism, agritourism, cultural tourism, and community tourism [19,55,56]. With the characteristics of exploiting tourism based on natural energy sources, local culture, the prioritization of environmental protection, and the participation of local people, these models are considered practical solutions for tourism businesses and developers seeking to restore tourism activities. According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), the number of tourists globally participating in rural and ecological tourism will account for 10%, with a revenue of about USD 30 billion by 2030, while traditional tourism (resort, sightseeing, entertainment, meeting) only increases by 4%/year on average. The criteria at the bottom of the rankings are development of SOPs for businesses involved in tourism and hospitality (ST9), investment in tourism infrastructure and facilities (ST4), and governmental financial and operational support for the tourism sector (ST1). This is consistent with the current context of stakeholders suffering heavy economic losses after the pandemic, leading to limited solutions related to finance and investment costs.

6.2. Conclusions

Tourism recovery is an urgent process in every country aiming to improve its economy and revive its peoples’ cultural life. The proposed model suggests that the best recovery strategy in Vietnam is the use of innovative tourism business models (ST2). Vietnam features a long-standing tradition of wet rice cultivaiton and biodiversity, offering a significant advantage in the creation of new tourism types such as rural tourism, ecotourism, and agritourism. Exploiting tourism in rural areas is a suitable way to utilize inherent potential, promote inherent traditional culture and improve the local economy. Moreover, innovation towards green tourism aligns with the current preferences of tourists for being close to nature, and gives opportunities for sustainable tourism development in Vietnam. In conclusion, this article presents specific policies relevant to the context of innovation after the COVID-19 pandemic, and proposes decision-making tools that will enable managers and policymakers to select the most effective policies. These findings provide valuable guidance for investors and practitioners in optimizing and restructuring the tourism industry. Furthermore, the proposed research framework fills an important gap by demonstrating the application of multi-criteria models in the field of tourism, effectively addressing existing research needs and contributing significantly to the knowledge base available for academics and researchers.

However, some limitations of the study remian, and must be addressed in future research. Under the proposed research framework, the survey was conducted with a sample size of only 36 participants in six groups. As a result, the findings may not fully capture the diverse perspectives of all stakeholders within the tourism value chain. To obtain a more comprehensive understanding, future studies should expand the sample size and include a broader range of stakeholders, such as government officials, local authorities, restaurant owners, and hotel managers. Additionally, while this paper presents nine strategies, it is important to recognize that these strategies may not fully address the complexities of the changing natural environment and the dynamic needs of tourists. Therefore, future research should explore additional development strategies that offer comprehensive actions for post-pandemic tourism recovery, and consider supporting other regions featuring different conditions. Furthermore, to obtain more accurate and reliable results, further comparisons of the here-described multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) techniques, such as TOPSIS, DEMATEL, VIKOR, and PROMETHEE, are recommended.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, W.-C.L., C.K.W. and T.K.T.L.; software and validation, T.K.T.L. and N.A.N.; formal analysis and investigation, C.K.W. and W.-C.L.; resources, C.K.W. and W.-C.L.; data curation, T.K.T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, W.-C.L., N.A.N. and T.K.T.L.; writing—review and editing, T.K.T.L. and N.A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by 2022 Departmental Quality Upgrade Grand—National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology (NKUST), grant number 111TSD00-2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

The comparison of strategies by enterprises (DMs, D7–D12).

Table A1.

The comparison of strategies by enterprises (DMs, D7–D12).

| Decision-Makers (DMs) | Strategies | Comparison | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST7 | ST8 | ST9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D7 | Best | 8 | Obj | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 2 | |

| D8 | Best | 6 | Obj | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| D9 | Best | 3 | Obj | 4 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Worst | 7 | Ojw | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | |

| D10 | Best | 2 | Obj | 4 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 5 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 3 | |

| D11 | Best | 5 | Obj | 5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| Worst | 7 | Ojw | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| D12 | Best | 8 | Obj | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 | |

Table A2.

The comparison of strategies by tourism operators (DMs, D13–D18).

Table A2.

The comparison of strategies by tourism operators (DMs, D13–D18).

| Decision-Makers (DMs) | Strategies | Comparison | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST7 | ST8 | ST9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D13 | Best | 5 | Obj | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 |

| Worst | 6 | Ojw | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | |

| D14 | Best | 2 | Obj | 6 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| D15 | Best | 6 | Obj | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 4 | 5 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 4 | |

| D16 | Best | 8 | Obj | 7 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 6 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3 | |

| D17 | Best | 3 | Obj | 6 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | |

| D18 | Best | 3 | Obj | 5 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 4 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 2 | |

Table A3.

The comparison of strategies by employees (DMs, D19–D24).

Table A3.

The comparison of strategies by employees (DMs, D19–D24).

| Decision-Makers (DMs) | Strategies | Comparison | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST7 | ST8 | ST9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D19 | Best | 6 | Obj | 6 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 3 | |

| D20 | Best | 7 | Obj | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Worst | 3 | Ojw | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 2 | |

| D21 | Best | 8 | Obj | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 2 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 | |

| D22 | Best | 8 | Obj | 7 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 5 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 7 | 3 | |

| D23 | Best | 8 | Obj | 6 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 7 |

| Worst | 7 | Ojw | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 2 | |

| D24 | Best | 2 | Obj | 5 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Worst | 6 | Ojw | 3 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

Table A4.

The comparison of strategies by residents (DMs, D25–D30).

Table A4.

The comparison of strategies by residents (DMs, D25–D30).

| Decision-Makers (DMs) | Strategies | Comparison | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST7 | ST8 | ST9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D25 | Best | 6 | Obj | 4 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 7 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 2 | |

| D26 | Best | 5 | Obj | 5 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |

| D27 | Best | 3 | Obj | 8 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 7 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 2 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| D28 | Best | 6 | Obj | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 6 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | |

| D29 | Best | 3 | Obj | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Worst | 8 | Ojw | 3 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| D30 | Best | 2 | Obj | 7 | 1 | 5 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 8 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 3 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 2 | |

Table A5.

The comparison of strategies by tourists (DMs, D31–D36).

Table A5.

The comparison of strategies by tourists (DMs, D31–D36).

| Decision-Makers (DMs) | Strategies | Comparison | ST1 | ST2 | ST3 | ST4 | ST5 | ST6 | ST7 | ST8 | ST9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D31 | Best | 3 | Obj | 7 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 7 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| D32 | Best | 3 | Obj | 6 | 4 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 3 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |

| D33 | Best | 2 | Obj | 4 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 |

| Worst | 4 | Ojw | 4 | 7 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |

| D34 | Best | 2 | Obj | 7 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Worst | 1 | Ojw | 1 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | |

| D35 | Best | 6 | Obj | 6 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| Worst | 7 | Ojw | 5 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |

| D36 | Best | 8 | Obj | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Worst | 5 | Ojw | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | |

References

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Li, X.; Lau, V.M.-C.; Dioko, L.D. Destination governance in times of crisis and the role of public-private partnerships in tourism recovery from COVID-19: The case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulchand-Gidumal, J. Post-COVID-19 recovery of island tourism using a smart tourism destination framework. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 23, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.B.; Sharma, P. Reviving Indian Tourism amid the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and workable solutions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 22, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, H.C. Strategies for post-COVID-19 prospects of Sabah’s tourist market—Reactions to shocks caused by pandemic or reflection for sustainable tourism? Res. Glob. 2021, 3, 100056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VNAT. A High Rate of Visitor Growth Makes an Important Contribution to Socioeconomic Development. Available online: https://www.vietnamtourism.gov.vn/post/32527 (accessed on 21 May 2023).

- Baochinhphu.vn. Fully Open to Tourism, Vietnam Attracts International Visitors. Available online: https://baochinhphu.vn/mo-cua-hoan-toan-du-lich-viet-nam-hut-khach-quoc-te-102220530140930452.htm (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Manhas, P.S.; Nair, B.B. Strategic role of religious tourism in recuperating the Indian tourism sector post-COVID-19. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2020, 8, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Van, N.T.T.; Vrana, V.; Duy, N.T.; Minh, D.X.H.; Dzung, P.T.; Mondal, S.R.; Das, S. The role of human–machine interactive devices for post-COVID-19 innovative sustainable tourism in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grofelnik, H. Assessment of acceptable tourism beach carrying capacity in both normal and COVID-19 pandemic conditions–Case study of the Town of Mali Lošinj. Hrvat. Geogr. Glas. 2020, 82, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulungen, F.; Batmetan, J.R.; Komansilan, T.; Kumajas, S. Competitive intelligence approach for developing an e-tourism strategy post COVID-19. J. Intell. Stud. Bus. 2021, 11, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orîndaru, A.; Popescu, M.-F.; Alexoaei, A.P.; Căescu, Ș.-C.; Florescu, M.S.; Orzan, A.-O. Tourism in a post-COVID-19 era: Sustainable strategies for industry’s recovery. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, E.A.; Boakye, K.A. Conceptualizing post-COVID 19 tourism recovery: A three-step framework. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 20, 37–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving tourism industry post-COVID-19: A resilience-based framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seshadri, U.; Kumar, P.; Vij, A.; Ndlovu, T. Marketing strategies for the tourism industry in the United Arab Emirates after the COVID-19 era. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 15, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising tourism for social and ecological justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagosa, F. The COVID-19 crisis: Opportunities for sustainable and proximity tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 690–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.-S. Tourism recovery strategy against COVID-19 pandemic. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milošević, I.; Voza, D.; Nikolić, I.; Ðorðević, P.; Arsić, M. The model of prioritization of strategies for regional developement of ecotourism in Eastern Serbia. In Proceedings of the Management, Enterprise and Benchmarking in the 21st Century, Budapest, Hungary, 27–28 April 2018; pp. 279–292. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, F.; Asadabadi, M.R.; Janjua, N.K.; Hussain, O.K.; Chang, E.; Saberi, M. An MCDM method for cloud service selection using a Markov chain and the best-worst method. Knowl. Based Syst. 2018, 159, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Nemery, P. Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis: Methods and Software; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, J. Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method. Omega 2015, 53, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajer, E.; Demir, S. Ecotourism strategy of UNESCO city in Iran: Applying a new quantitative method integrated with BWM. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Hasan, M.G.; Barbhuiya, R.K. Identification and prioritization of strategies to tackle COVID-19 outbreak: A group-BWM based MCDM approach. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 111, 107642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooripussarakul, S.; Riewpaiboon, A.; Bishai, D.; Muangchana, C.; Tantivess, S. What criteria do decision makers in Thailand use to set priorities for vaccine introduction? BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-N.; Nguyen, H.-P.; Huang, C.-C.; Wang, Y.-H. Evaluating Interventions in Response to COVID-19 Outbreak by Multiple-Criteria Decision-Making Models. Systems 2022, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadinejad, B.; Shabani, A.; Jalali, A. Implementation of clean hospital strategy and prioritizing COVID-19 prevention factors using best-worst method. Hosp. Top. 2021, 101, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grida, M.; Mohamed, R.; Zaied, A.N.H. Evaluate the impact of COVID-19 prevention policies on supply chain aspects under uncertainty. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 8, 100240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Kumar Singh, R. Strategic framework for developing resilience in Agri-Food Supply Chains during COVID 19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 1401–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangre, J.; Hameed, A.Z.; Srivastava, M.; Prasad, K.; Patel, D. Prioritization of factors and selection of best business practice from bio-medical waste generated using best–worst method. Benchmarking Int. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadafan, F.K.; Soffianian, A.; Pourmanafi, S.; Morgan, M. Assessing ecotourism in a mountainous landscape using GIS–MCDA approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2022, 147, 102743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.-J.; Lo, H.-W.; Chao, C.-S.; Shen, C.-C.; Yang, C.-C. Establishing a sustainable sports tourism evaluation framework with a hybrid multi-criteria decision-making model to explore potential sports tourism attractions in Taiwan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-C.; Shen, C.-C.; Mao, T.-Y.; Lo, H.-W.; Pai, C.-J. A Hybrid Model for Assessing the Performance of Medical Tourism: Integration of Bayesian BWM and Grey PROMETHEE-AL. J. Funct. Spaces 2022, 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Aswin, A.; Gupta, H. Evaluating green performance of the airports using hybrid BWM and VIKOR methodology. Tour. Manag. 2020, 76, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamagishi, K.D.; Abellana, D.P.M.; Tanaid, R.A.B.; Tiu, A.M.C.; Selerio, E.F., Jr.; Medalla, M.E.F.; Ocampo, L.A. Destination planning of small islands with integrated multi-attribute decision-making (MADM) method. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2021, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Absalon, J.A.T.; Blasabas, D.K.C.; Capinpin, E.M.A.; Daclan, M.D.; Yamagishi, K.D.; Ocampo, L.A. Impact assessment of farm tourism sites using a hybrid MADM-based composite sustainability index. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 2063–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haqbin, A.; Shojaei, P.; Radmanesh, S. Prioritising COVID-19 recovery solutions for tourism small and medium-sized enterprises: A rough best-worst method approach. J. Decis. Syst. 2022, 31, 102–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.; Cao, M.; Liu, Y. A novel hotel selection decision support model based on the online reviews from opinion leaders by best worst method. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2022, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzadeh, S.; Khansefid, S.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. A group multi-criteria decision-making based on best-worst method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 126, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.K.; Nguyen, N.A.; Dang, T.Q.T.; Nguyen, M.-U. The Impact of COVID-19 on Ethnic Business Households Involved in Tourism in Ninh Thuan, Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateljevic, I. Transforming the (tourism) world for good and (re) generating the potential ‘new normal’. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graci, S. Collaboration and partnership development for sustainable tourism. Tour. Geogr. 2013, 15, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, P. Tourism governance in the aftermath of COVID-19: A case study of Nepal. Gaze: J. Tour. Hosp. 2021, 12, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shubtsova, L.V.; Kostromina, E.A.; Chelyapina, O.I.; Grigorieva, N.A.; Trifonov, P.V. Supporting the tourism industry in the context of the coronavirus pandemic and economic crisis: Social tourism and public-private partnership. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2020, 11, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketter, E. Bouncing back or bouncing forward? Tourism destinations’ crisis resilience and crisis management tactics. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2022, 31, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawabreh, O. Management of tourism crisis in the Middle East. In Public Sector Crisis Management; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J.C. Tourism Crises: Causes, Consequences and Management; Routledge: England, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Rebuilding Tourism for the Future: COVID-19 Policy Responses and Recovery. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/rebuilding-tourism-for-the-future-co%20vid-19-policy-responses-and-recovery-bced9859/ (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Brouder, P.; Teoh, S.; Salazar, N.B.; Mostafanezhad, M.; Pung, J.M.; Lapointe, D.; Higgins Desbiolles, F.; Haywood, M.; Hall, C.M.; Clausen, H.B. Reflections and discussions: Tourism matters in the new normal post COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Chen, P.-J.; Lew, A.A. From high-touch to high-tech: COVID-19 drives robotics adoption. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 724–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Z.; Huimin, G.; Kavanaugh, R.R. The impacts of SARS on the consumer behaviour of Chinese domestic tourists. Curr. Issues Tour. 2005, 8, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.K.; Ho, M.-T.; Le, T.K.T.; Nguyen, M.-U. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Factors Influencing the Destination Choice of International Visitors to Vietnam. Sustainability 2022, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vietnam Ministry of Cultural, S.a.t. Tourism Is the Economic Sector That Suffers the Most from the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://bvhttdl.gov.vn/du-lich-la-nganh-kinh-te-chiu-thiet-hai-nang-ne-nhat-vi-dai-dich-COVID-19-20211216090147038.htm (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Varolgüneş, F.K.; Çelik, F.; Del Río, M.d.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J. Reassessment of sustainable rural tourism strategies after COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 944412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Dosquet, F. Mountain tourism and second home tourism as post COVID-19 lockdown placebo? Worldw. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 12, 485–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).