Abstract

The principal aim of the present study was to investigate the effect of a differentiated social studies course curriculum on gifted students’ verbal creativity. This study is important in terms of developing verbal creativity in gifted students through the social sciences curriculum. It is important in terms of being the first study to develop verbal creativity through a differentiation study in the field of social studies for gifted students. Differentiation in social studies was carried out by considering the Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM). For this, the study was conducted using a quasi-experimental design with pretest–post-test experimental and control groups. The sample consisted of 24 gifted students, 12 in the experimental group and 12 in the control group, selected from secondary schools in Istanbul. While the experimental group received this curriculum-oriented training to develop their verbal creativity skills, the control group received a standard social studies curriculum. In the study, the verbal creativity skills of gifted students were tested using the “Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal” (TTCT-V) before and after the interventions. In addition, a demographic information form was used to describe the demographic characteristics of the participants. Then, the data were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test and Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test. The findings showed that differentiated activities and instructions showed a significant positive effect on the gifted students’ verbal creativity skills. Therefore, it was concluded that the differentiated social studies curriculum developed for gifted students contributed to students’ verbal creativity skills.

1. Introduction

Gifted children learn differently from their peers. Therefore, they should be taught according to their learning content [1]. Curriculum differentiation is one of the appropriate methods for them. Gifted students should be differentiated in terms of content, process, and product [2]. They have a desire for in-depth and detailed learning in the subjects they want to learn. At the same time, acceleration and enrichment are important for them [3]. The products to be obtained should reveal their creativity. Teaching with these curriculum differentiation strategies makes their education sustainable [4].

Every single society may need creative individuals to follow and adapt to the rapidly developing world of science and technology. Creativity, on the other hand, is covered by a substantial number of definitions for giftedness [5]. According to the federal definition of [6], which is still accepted by the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), gifted individuals are those showing exceptional achievement in intellectual, creative, artistic, and leadership capacities or specific academic fields and needing extracurricular support to improve their such skills. Similarly, as Lee [7] uttered, creativity is among the remarkable characteristics of gifted children. Creativity and intelligence are not inherited traits but can be improved, since not being stable [8]. Miller [9] stated that students’ creative thinking can be improved thanks to creativity education. In addition, Torrance [10] reported that being able to unearth creative products merely depends on the support and development of creative breakthroughs in the first years of life. Therefore, it may be postulated that school curricula are critical in raising creative individuals; instructional models, methods, and strategies covering all dimensions of creativity should be employed to improve gifted creativity. These teaching models can also be designed for gifted social sciences.

Differentiation in social studies is encouraged by the National Council for Social Studies (NCSS) to move beyond the traditional textbook and teacher-centered approach to instruction that offers ready knowledge and understanding. Social studies should provide students with 21st-century knowledge and skills and citizenship virtues so that they can become active citizens [11]. There are three main categories of 21st-century skills: learning and innovation skills (creativity, innovation, critical thinking, problem solving, communication, and collaboration), knowledge, media, and technology skills (media and information literacy), and life and career skills (resilience, adaptability, self-management, and social and intercultural skills, productivity, accountability, leadership, and responsibility) [12]. Creative thinking, working creatively with others, and innovation are core skills among 21st-century skills [13]. It is noteworthy that today’s educators extensively focus on 21st-century skills, especially creativity skills. When it comes to Turkey, the social studies curriculum has recently been adapted to include several skills and outcomes, especially creativity, desired to be acquired by students [14].

Since social studies represent human experiences and skills through concepts relating to humanity, a teacher can systematically enhance learning and address a variety of interests and abilities of their students at different difficulty levels [15]. The subject also brings opportunities for teachers and students to create highly differentiated learning experiences [16]. In the context of gifted education, the subject has some offerings to facilitate gifted students’ higher-order thinking skills in conjunction with their educational needs and experiences in daily life [17]. The curriculum may also introduce several options suitable for the learning capacity of both typically developing and gifted students because the ultimate aim of the subject is to enable students to consider the school environment as an actual community, to raise their awareness that they are active members of society, and to identify problems in daily life and find solutions to them [18]. There is a close relationship between the aims, objectives, and outcomes of gifted education and the aims of social studies. Social studies’ interdisciplinary nature may become attractive to gifted students. Social and global problems, relevant solutions for these problems, and creative projects, workshops, and activities orienting to daily life are some of the areas of interest of gifted students and are also the topics of social studies [19].

There has already become a need to organize social studies curricula according to the educational needs of gifted students with natural talent and motivation in social studies [20]. Accordingly, the curriculum may be differentiated for gifted students in three aspects: content-related changes, changes in instruction, and changes in student project/homework products [21]. Since gifted students can learn more in a shorter time compared to their peers, teachers may address and expand the topics in-depth with more knowledge. Instructional differentiation, on the other hand, includes using challenging materials, allowing more critical thinking activities, and planning more creative thinking activities. Gifted students can be provided with more autonomy in the class and more creative projects/assignments according to their orientations. These projects are realized with integrated curriculum models [22].

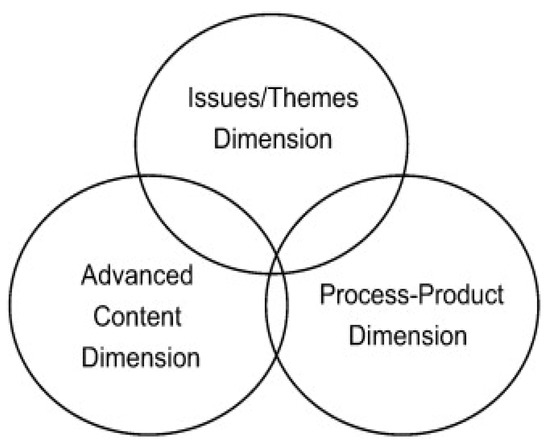

Over the years, it has been the subject of discussion how the teaching model suitable for gifted students should be and various teaching models have been put forward. VanTassel-Baska introduced “The Integrated Curriculum Model” [22]. The model has been supported and revised by numerous studies over time. The Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM) [23] is a model that defines the elements of differentiated learning and unites curriculum, learning and assessment in three overlying dimensions for gifted students: advanced content, process/product, and issues/themes. These dimensions are correlated and equal to each other. The features and the whole structure of the model are dependent on this balanced relationship [22]. The Integrated Curriculum Model organizes the acceleration, project studies, and higher-order thinking skills and development opportunities in a single package. Thus, it enables gifted students to experience a more integrated learning model [23].

1.1. Theoretical Background and Model

Gifted children are fluent, original, and flexible learners. The appropriate programs and instruction reveal the talents of gifted children [24]. The programs designed for gifted children are to meet their educational needs that cannot be met in traditional educational environments. For the education to be effective, it is necessary to know the components of education programs [25]. How the program will be organized should be decided by considering the characteristics of the students. A well-planned program can transform gifted students’ skills in mental activities into competence. They usually learn subjects holistically and see the parts that make up the whole and the connections between them. In this sense, their learning characteristics should be taken into consideration [26]. Teachers should be aware of the characteristics of gifted students. They should include activities for students’ flexibility, fluency, and elaboration abilities based on their creative thinking skills [20].

Curriculum differentiation is used to organize the curriculum content for gifted students. In general, curriculum differentiation is the enrichment, acceleration, elaboration, complication, stretching, and compacting of curriculum content [24]. Reis Peters [27] argues that enrichment and acceleration are necessary in the education of gifted students. Even at a young age, gifted students will be able to receive initial education in line with their needs and then, when their talents become apparent, they will be directed to their field. For the right differentiation, attention should be paid not only to a certain field but also to various fields, and social sciences are the most important of these [26]. However, care should be taken to ensure that the designs are sustainable. Care should be taken to have flexible content that covers primary, middle, and high school. The skills, goals, subjects, and content that students should acquire should be selected according to their characteristics. The strategies used in differentiation vary [28]. The most important of these are strategies such as enrichment, acceleration, grouping, compacting, stretching, etc. [24].

Enrichment: Enrichment is a supportive arrangement provided outside the traditional subject areas, considering the general education program. It is defined as differentiations outside the curriculum for students with advanced learning needs [27]. Enrichment aims to support students’ areas such as creativity and motivation. In this way, it improves creative problem-solving, critical thinking, and analytical thinking skills [25]. Enrichment also plays an important role in helping gifted students achieve success. Acceleration: Acceleration is one of the most effective arrangements in the curricula designed for gifted students [29]. Acceleration includes acceleration types such as starting school early, skipping classes, and having students take upper-level courses [30]. Grouping: Grouping is the opportunity offered to gifted students according to various situations. There are different grouping strategies. These are full-time ability groups, achievement groups, in-class groupings, clustering, and out-of-class groupings [29]. Compacting: These are practices that shorten the training time and accomplish many goals in less time. It is designed according to students’ readiness and gives the desired results [30]. In this study, curriculum differentiation strategies were used by considering the most appropriate age ranges. One of the most appropriate models for the development of gifted students in certain areas is the Integrated Curriculum Model. In the study where content, process, and concept-theme dimensions will be addressed, the Integrated Curriculum Model will be able to meet all dimensions.

1.2. Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM)

VanTassel-Baska [22,23] developed the Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM) (Figure 1), which aims to meet the needs of gifted students. The Integrated Curriculum Model is an eclectic synthesis of the components of curriculum models whose effectiveness has been demonstrated in the literature. Advanced content, product-process, and topic-theme dimensions constitute the basic components of BMM. These dimensions are linked to learning characteristics called early development, intensity, and complexity. Theoretically, all the dimensions of CBM are interrelated and can therefore form the basis for curriculum development efforts in all disciplines [22,23].

Figure 1.

Integrated curriculum model (ICM) for gifted learners.

The advanced content dimension is based on extensive research [22] that demonstrates the effectiveness of using acceleration in gifted education. ICM is based on using acceleration practices in the content of the developed programs. First, the objectives and outcomes of the advanced content dimension are determined according to the compared grade level. Second, the ICM curriculum units are developed using a diagnostic-expository approach. In the third step, assessment, similar to instruction, is developed to be above the benchmarked grade level. This aims to ensure in-depth learning. Finally, all these steps are carried out and evaluated in collaboration with educators and field experts [23].

The process–product dimension is based on the ICM components of developing thinking skills, product development, and independent work on areas of interest [22]. In the process–product dimension, the Renzulli Schoolwide Enrichment Model’s Type II and Type III activities are used in which students first learn basic thinking skills and then use them to create a product. Problem-based learning is also used extensively in the process–product dimension of ICM curriculum units [23].

Concept–theme is the epistemological concept dimension of ICM. It argues that gifted students should be organized around deep ideas and thoughts that will enable them to understand people and the nature of knowledge [22]. This dimension involves the development of the curriculum around fundamental concepts in the relevant discipline. In the literature, it is an important fact that conceptual thematic approaches are effective in gifted education programs [23].

Therefore, the present study investigated a differentiated social studies curriculum in association with creativity. A differentiated social studies curriculum, which will be further revised considering the findings, allows the enhancement of verbal creativity skills among gifted children. Considering the low number of counters of research interest in such curricula and creativity in gifted students, the contribution of the present study to the relevant field becomes more eminent. In addition, the findings may draw a detailed roadmap for further studies aiming at improving the verbal creativity of gifted students. The development of verbal creativity in gifted students through differentiation of social studies is of great importance as it has not been carried out before. It is also important in terms of conducting the research under pandemic conditions in a metropolis such as Istanbul, where it is difficult to implement. It is also important in terms of finding the significant difference results by controlling the self-learning processes of gifted students in the field of social studies. This general framework aims to develop verbal creativity skills in gifted students through the social studies curriculum. For this purpose, the following questions were sought to be answered.

1.3. Purpose

The principal purpose of the study was to test a differentiated social studies curriculum prepared to improve gifted students’ verbal creativity skills. The study sought answers to the following questions:

What is the effect of the differentiated social studies curriculum on the verbal creativity skills of gifted secondary school students?

- Are there significant differences between the pretest TTCT-V scores of the experimental and control groups?

- Are there significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V test scores of the experimental group?

- Are there significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V test scores of the control group?

- Are there significant differences between the post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental and control groups?

Considering the research purpose and questions, the following hypotheses were formulated:

- The pretest TTCT-V scores of the control and experimental groups do not significantly differ.

- There are significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental group.

- There are no significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the control group.

- The post-test TTCT-V scores of the control and experimental groups significantly differ.

2. Materials and Methods

In this section, the description of the research group, selection of groups, formation of experimental and control groups, research design, data collection tools used in the research, statistical methods used in data analysis, the program applied to the experimental group, and the experimental procedure applied to the control group are mentioned. The research is in a quantitative research method. It is an experimental design study.

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a quasi-experimental design with experimental and control groups to test the effect of a differentiated social studies curriculum on gifted students’ verbal creativity. While the dependent variable is secondary school students’ scores on the “Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal” (TTCT-V), the independent variable is receiving differentiated social studies education.

In this research, a 2 × 2 mixed design including pretest and post-test with the experimental and control group was used. In mixed designs, also called split–plot factorial designs, there are at least two variables whose effects are sought on the dependent variable. While one of them defines the different experimental conditions with neutral groups, the other refers to the repeated measurements of the subjects at different times, pretest and post-test [31]. In this study, the between-group variable defines the “experimental and control groups,” and the within-group variable corresponds to “pretest and post-test.” The research design is illustrated in the Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Research design.

Implementation: According to the declaration of Helsinki, this study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, AU with COMS protocol/human subjects approval number 20191120-218 and clearance number 55578142-050.01.04-E.151248. The academic staff of the ethics committee are from the social sciences and natural sciences. The committee considered the research permission forms, contracts, etc. when making its decision. The decision was taken by consensus.

Then, the implementation of the research was started. Initially, all subjects in both groups were administered the TTCT-V as a pretest. The pretest measurements were taken and analyzed 1 week before the implementation of the curriculum. In the implementation phase, the experimental group received social sciences education based on a differentiated curriculum for 18 weeks (18 units). Simultaneously, the control group attended 18 classes performed with a standard curriculum. The implementations in both groups were finalized simultaneously, and the post-test measurements were taken by readministering TTCT-V to the groups. At the beginning of the study, the pretest measurements were taken from the subjects and no significant difference was found between the groups. One week later, the programs (differentiated and standard curriculum) with the groups started. After 18 sessions, each lasting 30–55 min, post-test measurements were taken from the participants to test the hypotheses.

2.2. Participants

The sample consisted of a total of 24 gifted secondary school students, 12 in each group. The research group consisted of 12 students from the experimental group and 12 students from the control group. The inclusion–exclusion criteria for participants in the study were considered. The inclusion criteria were an IQ score of 130 and above, a score above their age norm on the Torrance Test of Creative Intelligence, being middle-school age, motivation for social studies lessons, living in Istanbul, and attending classes. The exclusion criteria were bright and normal IQ, and not attending classes.

The age means and standard deviation of the students in the experimental and control groups are given in Table 2. The youngest age of the male experimental and control groups and the youngest age of the female experimental and control groups was 12 years and the oldest age was 13 years. Students of similar ages were selected so that the experimental and control groups were equal. Therefore, age means are given.

Table 2.

Distribution of students.

Sample Selection: The curriculum was implemented through online classes for students attending different gifted programs in public and private institutions in Istanbul in 2021. Secondary school students were included in the study considering their previous educational background and creativity potential. While forming the groups, homogeneity, gender of the students, and their intelligence quotient (IQ) scores in tests such as TTCT-V and WISC-4 were taken into consideration. Therefore, the groups consisted of an equal number of students regarding gender and IQ score (130).

The Hawthorne effect, which is considered to be an important confounding variable that may affect research findings and their generalizability in experimental studies, was controlled. The Hawthorne effect refers to that subjects tend to show positive behavior, knowing they are in an experiment and assuming that the researcher(s) expects a positive behavior change from them. Therefore, a control group was formed to match the experimental group and the subjects in this group were presented with activities other than those in the differentiated curriculum.

2.3. Data Collection Tools

“The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal” (TTCT-V) and “Demographic Information Form” were used in the study. The Demographic Information Form was used to determine variables such as the age of the students. The students were divided into experimental and control groups of similar ages. “The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal” (TTCT-V) was used to measure the students’ verbal creativity skills.

2.3.1. Demographic Information Form

A demographic information form was created to obtain information about the demographic characteristics of the subjects (e.g., gender, age, etc.). This form was used to equalize the groups in terms of age, etc. The experimental and control groups were divided into two equal groups according to these data.

2.3.2. The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal (TTCT-V)

This is among the popular tests to measure creativity and consists of two forms: Figural A-B and Verbal A-B. Torrance administered the test to groups of different ages and occupations in his studies at the University of Minnesota and made it available [32]. Although it is often utilized to identify gifted children, it also serves to design individualized education for students by their creativity scores [33]. While creating the test, the developer made assumptions such as creativity as a natural ability, inconsistency in activities, awareness of incompleteness, and problem solving were accepted. The validity and reliability study of the test was replicated five times with participants with diverse backgrounds. While the current version of the test was validated in 1984, its 50th-year validity study was carried out in 2010 [34].

2.4. Data Analysis

First, it was checked whether the test scores of the groups met the assumptions of the parametric tests. Performing parametric tests, for example, highly relies on a normal distribution of the data in the sample observations. To test this assumption, both the skewness and kurtosis values and Shapiro–Wilk test results for the pretest and post-test scores of both groups were taken into consideration. Accordingly, since it was determined that the skewness and kurtosis values exceeded the acceptable range and the Shapiro–Wilk test gave a significant result, it was decided that all scores of both groups did not show a normal distribution.

Following the normality tests, homogeneity of variance, another assumption of parametric tests, was tested with Levene’s test. The results showed that the variances of all variables in both groups were not homogeneous. In general, relevant nonparametric tests were performed on the data using SPSS and a p-value < 0.05 was considered significant in all statistical analyses. The results that are significant are specified with an asterisk: *** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05.

3. Results

The findings obtained as a result of testing the hypotheses are given below.

3.1. Testing Hypothesis 1

“Hypothesis 1—The pretest TTCT-V scores of the control and experimental groups do not significantly differ.” To test the hypothesis, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied to the pretest TTCT-V scores of both groups. The result is summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Comparison of the pretest Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores of the groups.

As in Table 3, there was no significant difference between the pretest TTCT-V scores of the groups (fluency: U = 59.50, z = −0.75; p > −0.05). However, originality: U = 19.50, z = −3.11; ** p < −0.01; flexibility: U = 3.00, z = −4.10; *** p < −0.001; total score: U = 5.50, z = −3.92; *** p < −0.001 results were also found. Considering the mean ranks for the total and subtest scores on the TTCT-V, it was determined that the average scores of the experimental group were lower than the control group before the application. Yet, the groups did not significantly differ by the pretest fluency scores, and Hypothesis 1 is partially confirmed (originality, flexibility, and total score are significantly higher in the control group).

3.2. Testing Hypothesis 2

“Hypothesis 2—There are significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental group.” To test the hypothesis, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test was applied on the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental group, and the results are given in Table 4 and Table 5.

Table 4.

Pretest and post-test Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores of the experimental group.

Table 5.

The comparison of the experimental group’s pretest and post-test Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores.

The pretest fluency of the experimental subjects was found to be lower M = 74.75, SD = 0.96), originality (M = 73.16, SD = 1.40), flexibility (M = 72.50, SD = 0.50), and total (M = 73.50, SD = 0.90) scores than their post-test fluency (M = 85.00, SD = 4.55), originality (M = 80.41, SD = 1.92), flexibility (M = 84.41, SD = 1.03), and total (M = 83.33, SD = 1.92) scores.

As in Table 5, after the 18-session implementation, significant differences were found between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental group (z = −2.99 p < 0.01 for fluency; z = −3.07 p < 0.01 for originality, z = −3.06 p < 0.01 for flexibility, and z = −3.07 for the total score; p < 0.01 for all). Since the said differences were in favor of the post-test scores, it is confidently claimed that Hypothesis 2 is confirmed: gifted students’ verbal creativity significantly improved after the implementation.

3.3. Testing Hypothesis 3

“Hypothesis 3—There are no significant differences between the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the control group.” To test the hypothesis, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks test was performed on the pretest and post-test TTCT-V scores of the control group. Table 6 and Table 7 present the results.

Table 6.

Pretest and post-test Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores of the control group.

Table 7.

The comparison of the control group’s pretest and post-test Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores.

Table 6 reveals that the pretest fluency (M = 74.58, SD = 1.37), originality (M = 75.83, SD = 1.27), flexibility (M = 76.91, SD = 1.63), and total (M = 75.83, SD = 0.93) scores of the control subjects were lower that their post-test fluency (M = 78.66, SD = 2.42), originality (M = 74.08, SD = 1.78), flexibility (M = 75.41, SD = 1.50), and total (M = 75.75, SD = 1.60) scores. The post-test scores are lower than pretest scores in all tests. Only the fluency score differs from others.

Following the implementation of the 18-session standard curriculum, the pretest and post-test TTCT-V (only total) scores of the control group showed no significant differences (z = −0.15 for the total score; p > 0.05). However, z = −2.92 for the fluency score; ** p < 0.01; z = −2.37 for the originality score; ** p < 0.05; z = −2.91 for the flexibility score; ** p < 0.01 were also found. In other words, the activities in the standard social studies curriculum did not create a significant difference in the creativity levels of the control subjects. Hence, Hypothesis 3 was confirmed: gifted students in the control group did not have a significant improvement in their total score verbal creativity skills at the end of the 18-session standard social studies program.

3.4. Testing Hypothesis 4

“Hypothesis 4—The post-test TTCT-V scores of the control and experimental groups significantly differ.” Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare the post-test TTCT-V scores of the experimental and control groups. Table 8 presents the findings.

Table 8.

Comparison of the post-test Torrance Test of Creative Thinking-Verbal scores of the groups.

The findings suggested significant differences between the experimental and control groups by the post-test TTCT-V scores (U = 13.50, z = −3.39 for fluency; U = 22.00, z = −4.10 for originality; U = 1.00 z = −4.16 for flexibility, and U = 0.00 z = −4.18 for the total score; *** p < 0.001 for all). Considering the mean ranks for the total and subtest scores on the TTCT-V, after the application it was determined that the experimental group had higher average scores than the control group. Therefore, the final hypothesis was confirmed: the differentiated social studies curriculum led to an improvement in the gifted students’ verbal creativity skills.

4. Discussion

In this study, it was attempted to develop the creative skills of gifted students through activities in social studies subjects through differentiated instructional strategies considering their learning needs. Since instructional practices have an important place in gifted education, various instructional strategies should be adapted to successfully differentiate the curriculum. In this study, we found that the activities created in a differentiated curriculum were effective in developing the overall creativity among the participating gifted students.

Curriculum differentiation for gifted students was carried out with the Integrated Curriculum Model (ICM). A similar theoretical background is realized in the Purdue and William and Mary Curriculum Differentiation Models. Differentiation dimensions include content, process, and product differentiation. Strategies such as enrichment, acceleration, compacting, etc. are effective in teaching gifted students. Similar theoretical studies carry parallel constructs.

Our findings are in line with previous findings in the literature. There have been studies conducted in Turkey with similar results. Atalay [20] implemented a differentiated social studies curriculum based on the integrative curriculum model for a group of students and concluded that the experimental group had higher creativity scores than the control group. These findings seem to overlap with our findings. Moreover, Ateş [21] argued that creativity-boosting methods and techniques, such as multiple intelligence, creative writing, asking creative questions, and creative problem solving, should be included in social studies teaching. In addition, emphasizing the need for differentiated curricula for gifted students, he created a program differentiating secondary school social studies curriculum to improve students’ thinking and creativity skills. Çetinkaya [35] found that curriculum differentiation improved creative thinking skills. In the study, a curriculum for gifted students was developed. With the developed curriculum, gifted and normal students were given education. The creativity skills of gifted students improved. Kahveci and Atalay [36] examined the views of gifted students on education with the Integrated Curriculum Model. The opinions of the students regarding the social studies units were taken. The positive opinions of the gifted students towards a model were revealed. Karataş and Ozcan [37] discovered that creative thinking activities had substantial impacts on the creative skills of the gifted. Similarly, Kadayıfçı [38] developed a creative thinking-based teaching model for gifted students and found that the model had positive impacts on their creativity skills.

Studies supporting the findings have also been conducted outside Turkey. Mildrum [39] implemented a program aiming to flourish creativity in students and concluded significant improvements in the students’ creativity skills and attitudes. In that research, the author considered the increase in the awareness of cognition and creativity sufficient for an improvement in creativity skills. There is limited research interest in social studies education aimed at improving gifted students’ verbal creativity through a differentiated curriculum. Troxclair [40] reported that differentiated social studies instruction contributes to the quality of learning among gifted students. Mason [41] argued that creative thinking is a skill that should be acquired by students, even through educational programs. The study utilized analogies during the sessions to contribute to improving creativity skills among the participants, which yielded positive results on the scores on the creativity dimensions.

5. Conclusions

In this study, it is believed that a differentiated social studies curriculum for gifted students can improve their verbal creativity skills. This effect is only valid for the small sample of the research. The same effect may not be observed for general education groups. There is very little research in the field of giftedness in Turkey. There are no studies in the field of social studies education and verbal creativity. The results obtained in this way are very valuable. The difficulty of reaching gifted students and the coincidence of the applications with the pandemic period made it difficult to carry out the research. Despite all the difficulties, the hypotheses of the study were confirmed.

Creative thinking skills hold an inevitable position among 21st-century skills. They may be needed to adapt to information, communication, and change in today’s fast-changing world. In addition, social studies are a subject believed to contribute to the verbal creativity of gifted students the most. In this respect, the differentiated social studies curriculum developed in this study will guide further research, experts, curriculum developers, and teachers as a unique model for improving creativity skills among gifted students.

Gifted creativity is a rare topic in the education community. Curriculum differentiation studies in social studies are limited compared to science and mathematics. The introduction of a curriculum differentiation model, especially in social studies, makes it easier for educators and students. Students can learn at their learning level. Strategies such as acceleration and enrichment facilitate their learning. The model is designed to be easily applicable in teachers’ classrooms. Practices such as these theoretical applications should also be taken into consideration. In the study, effective results were obtained in a field such as verbal creativity with an easy and applicable flexible model. There are many institutions providing education in the field of giftedness. Their teaching models are very suitable for these research results. They are easily understandable and applicable to teachers and students.

The education community will apply the findings to their settings in a useful way. In the National Education curriculum, there are almost no acquisitions that develop creative thinking skills. Elective courses that develop creative thinking skills can be added to the curriculum. For this course, the results and activities of the research can be used as ready-made materials. Fluency, originality, and flexibility are important subdimensions of verbal creative thinking. These skills are great opportunities for the development of verbal creative thinking in students. These activities can be developed for teachers and students. It is considered to develop a nationwide teacher training program with a model whose effectiveness can be tested in a larger sample. With expanding rings, a sustainable model can be implemented throughout the country.

However, this study has several limitations. The research can also be conducted in different age groups. It is especially necessary to conduct research at the primary school-age level. Samples were selected from Istanbul to be generalized to the population. Istanbul is a very large and crowded city. In this sense, it was difficult to create experimental and control groups. Transportation and time problems of the students prevented the selection of more qualified groups. This sample selection should be increased by selecting more samples from different provinces. Since the study took place during the pandemic, motivation was not as high as in the natural environment. This also affected the findings of the study. Financial opportunities should be provided to increase the number and quality of the research. It should also be implemented in other provinces than Istanbul. A national gifted social studies curriculum should be developed from the findings. The research implementation process took several months. Reliability can be increased by increasing this period. After the implementation, no significant difference was found in some of the verbal creativity subtests. This can be explained by the rapid self-learning of gifted students. It is suggested that the content of these subtests should be differentiated more comprehensively.

Funding

The research was supported by AU in Turkey, grant number SBA5272.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by Research Ethics Committee, AU with COMS protocol/human subjects approval number 20191120-218 and clearance number 55578142-050.01.04-E.151248.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the research.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the author, without undue reservation. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions on their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kaplan, S.N. Differentiated Curriculum and Instruction for Advanced and Gifted Learners; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- VanTassel-Baska, J. Curriculum in gifted education: The core of the enterprise. Gift. Child Today 2021, 10, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.M.; Renzulli, S.J.; Renzulli, J.S. Enrichment and gifted education pedagogy to develop talents, gifts, and creative productivity. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sak, U.; Ayas, B. EPTS curriculum model: Optimum curriculum differentiator for the education of gifted students. Gift. Educ. Int. 2020, 36, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagné, F. Transforming gifts into talents: The dmgt as a developmental theory. In Handbook Gifted Education; Colengelo, N.N., Davis, G., Eds.; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 66–74. [Google Scholar]

- Marland, S.P. Education of Gifted and Talented; US Office of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.E.; Meyer, M.S.; Crutchfield, K. Gifted classroom environments and the creative process: A systematic review. J. Educ. Gift. 2021, 44, 107–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, Ç. The effect of gifted students’ creative problem-solving program on creative thinking. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 116, 3722–3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L. Conceptualizations of creativity: Comparing theories and models of giftedness. Roeper Rev. 2012, 34, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E.P. Guiding Creative Talent; US Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Maxim, G.W. Dynamic Social Studies for Elementary Classrooms, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Zarillo, J. Teaching Elementary Social Studies: Principles and Applications; Pearson Education: Boston, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Piirto, J. Creativity for 21st Century Skills: How to Embed Creativity into the Curriculum; Sense Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sağlam, S.; Yalçınkaya, E. The evaluation of Turkish republics in the grade social studies textbook. J. Int. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2022, 8, 413–449. [Google Scholar]

- Lewthwaite, S.; Nind, M. Teaching research methods in the social sciences: Expert perspectives on pedagogy and practice. Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2016, 64, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, E.A. The use of independent study as a viable differentiation technique for gifted learners in the regular classroom. Gift. Child Today 2008, 31, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilburn, D.; Nind, M.; Wiles, R. Learning as researchers and teachers: The development of a pedagogical culture for social science research methods? Br. J. Educ. Stud. 2014, 62, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbiss, J. Social sciences and ‘21st century education’ in schools: Opportunities and challenges. N. Z. J. Educ. Stud. 2013, 48, 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Taş, G.; Akoğlu, K. The effect of cooperative learning approach in social studies teaching: Meta-synthesis study. J. Turk. Educ. Sci. 2020, 18, 956–983. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, Z.Ö. The Effect of Differentiated Social Studies Instruction on Gifted Students’ Academic Achievement, Attitudes, Critical Thinking and Creativity. Ph.D. Thesis, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ateş, H. An Enriched Program Proposal in Teaching Social Studies for Gifted Children. Master’s Thesis, Yildiz Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- VanTassel-Baska, J.; Wood, S. The integrated curriculum model (ICM). Learn. Individ. Differ. 2010, 20, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanTassel-Baska, J. Introduction to the integrated curriculum model. In Content-Based Curriculum for High-Ability Learners, 3rd ed.; VanTassel-Baska, J., Little, C., Eds.; Prufrock Press: Waco, TX, USA, 2017; pp. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Çetinkaya, Ç. Project-based curriculum differentiation example of gifted students. Ank. Univ. Fac. Educ. Sci. J. Spec. Educ. 2021, 22, 419–438. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-R.; Chen, M.-F. Practice and evaluation of enrichment programs for the gifted and talented learners. Gift. Educ. Int. 2020, 36, 108–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eikeland, I.; Ohna, S.E. Differentiation in education: A configurative review. Nord. J. Stud. Educ. Policy 2022, 8, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.M.; Peters, P.M. Research on the schoolwide enrichment model: Four decades of insights, innovation, and evolution. Gift. Educ. Int. 2021, 37, 109–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziernwald, L.; Hillmayr, D.; Holzberger, D. Promoting high-achieving students through differentiated instruction in mixed-ability classrooms—A systematic review. J. Adv. Acad. 2022, 33, 540–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neihart, M. The socioaffactive impact of acceleration and ability grouping. Gift. Child Q. 2007, 5, 330–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, S.I. Challenges and opportunities for students who are gifted: What the experts say. Gift. Child Q. 2003, 47, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüköztürk, Ş. Data Analysis Handbook for Social Sciences, 28th ed.; Pegem Akademi Pub: Ankara, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Torrance, E.P. Torrance Test of Creative Thinking. Verbal Tests Forms A and B. (Figural A&B); Scholastic Service Inc.: Bensenville, IL, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.H. Can we trust creativity tests? a review of the torrance tests of creative thinking (TTCT). Creat. Res. J. 2006, 18, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runko, M.; Miller, G.; Acar, S.; Cramond, B. Torrance tests of creative thinking as predictors of personal and public achievement: A fifty-year follow-up. Creat. Res. J. 2010, 22, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, Ç. The Effect of Unusual Topics Study Activities on Creativity. Ph.D. Thesis, Canakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Canakkale, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kahveci, N.G.; Atalay, Ö. Use of integrated curriculum model (icm) in social studies: Gifted and talented students’ conceptions. Eurasian J. Educ. Res. 2015, 59, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş, S.; Özcan, S. The effects of creative thinking activities on learners’ creative thinking and project development skills. Ahi Evran Univ. J. Fac. Educ. 2010, 11, 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Kadayıfçı, H. The Effect of An Instructional Model Based on Creative Thinking on Students’ Conceptual Understanding of Separation of Matter Subject and Their Scientific Creativity. Ph.D. Thesis, Gazi University, Ankara, Turkey, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mildrum, N.K. Creative workshop in the regular classroom. Roeper Rev. 2000, 22, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troxclair, D.A. Differentiating instruction for gifted students in regular education social studies classes. Roeper Rev. 2000, 22, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, L. Fostering understanding by structural alignment as a route to analogical learning. Instr. Sci. 2004, 32, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).