Abstract

The aim of this paper is to highlight the state of development of tourist ports in the Romanian Black Sea coastal area and their implications for the sustainable provision of quality recreational transport. As indicated by the collected data, both locals and tourists are showing a growing interest in nautical sports and maritime recreational activities, and there are plans to upgrade existing marinas and build new ones. Although the boating activity in the Romanian Black Sea coastal area is not as developed and popular as that in other areas of the Balkan Peninsula, it has particular advantages due to its geographical position close to the Danube and its delta, as well as its historical and cultural heritage. Between 2014 and 2019, the south marinas of Romania’s Black Sea coast experienced a 65% increase in the number of visiting boats. Despite some decreases in traffic during the pandemic, the general trend continues to be upward. An evaluation of the operational capacities and policies implemented by tourist ports and relevant stakeholders identifies the strengths and weaknesses of the current system and provides insights into the current activity and implemented policies of the four most known and developed marinas along the Romanian Black Sea coast. The study’s main objective is to assess sustainable practices in relation to the environmental, social, and economic systems, with a focus on environmental protection, the use of renewable energy sources, and the implementation of quality management standards. The study uses a mix of qualitative and quantitative analyses to achieve this. Interviews with representatives of the four coastal marinas helped gather the data. The size of boat traffic was evaluated by taking into consideration the data from the local harbor master. The research identified gaps and highlighted areas that require improvement, subsequently providing recommendations to enhance sustainability. The findings can guide policymakers and stakeholders in developing practices that can promote the growth of recreational nautical transport in Romania while ensuring the sustainable development of the sector.

1. Introduction

Nautical recreational transport has emerged as a crucial component of the tourism industry, particularly in coastal areas. Water is utilized for transportation and nautical tourism, which depends on safe navigational routes and sustainably managed coastal areas and ports.

While the term “nautical tourism” has traditionally been associated with the concept of navigation, other terms such as sailing, yachting, navigation tourism, and nautical recreational transport are more commonly used today to describe this type of activity. Some scholars define nautical tourism as “the sum of multi-functional activities and relations caused by tourists mooring in or off nautical tourism harbors using vessels or other navigation facilities for the purpose of recreation, sports, or simply the enjoyment of leisure [1]”. Finding a definition of the concept of nautical tourism remains a complex issue, as there are many component factors and elements, and for this reason, some authors have proposed the term “blue tourism” [2].

The Black Sea remains an area with huge potential for the development of blue tourism, which can promote economic growth and create a positive image of surrounding countries [3]. As marinas and ports are the main pillars of recreational nautical transport, their sustainable development can have a significant positive effect on the economy of transport, especially in less developed areas [4].

So far, there has been no published research evaluating the impact of regional marinas on the Romanian coastal waters.

Conducting research on marina development in Romania has the potential to provide valuable insights that can guide the establishment of policies and practices that foster sustainable and conscientious growth, generate economic prospects, and safeguard the environment. Looking at the current data for Europe, the latest numbers show that there are about 6.3 million boats, 4500 marinas, and 1.75 million berths [5]. In Romania, there are about 11,300 boats and a number of small inland tourist ports, as well as 4 developed ports, on the Black Sea [6], but the trend shows an increasing interest for development.

There is an initiative in line with the national strategic development plan that aims to develop and modernize tourist ports on the Black Sea coast. Alongside the existing marinas, they could become transport and recreational hubs for small and medium-sized boats on the Black Sea, creating the necessary basis for cruises along the Romanian coastline and for the development of yachting tourism [7].

- -

- The construction of the Diamant tourist port (Constanța);

- -

- the construction of the Marina Nord tourist port (Constanța);

- -

- the construction of the Năvodari tourist port;

- -

- the construction of the Eforie Sud tourist port;

- -

- the construction of a tourist port in the Tuzla area;

- -

- the modernization and extension of the Eforie Nord tourist port.

The development must comply with the regulatory framework of the EU and the European Directive 2019/883 that states that “the Union’s maritime policy aims to ensure a high level of safety and environmental protection” [8]. At the EU level, there has also been a growing number of leisure ports or marinas built for boats with mainly recreational or leisure purposes [9].

Furthermore, according to the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, “the international community should conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development” [10].

The question is: can the development of these new marinas be carried out in a sustainable manner that ensures adherence to contemporary standards of environmental preservation and activities with minimal impact? Sustainability and a green approach can bring a number of potential advantages to society, the economy, and the environment. Some of these advantages include: reduced environmental impact, improved health of the fauna, improved cost savings, increased innovation, and enhanced business reputation. The timing and priorities for a marina’s green approach investment will depend on a variety of factors, including the marina’s current environmental impact, the availability of funding and resources, and the marina’s goals and priorities. Conducting a thorough assessment of the current operations of established marinas, evaluating their impact on the environment, and identifying areas that need improvement can guide the sustainable development of new marinas.

2. Literature Review

Nautical tourism includes an active human component (skippers and boatmen), a passive component (tourists with different needs), and a management and endowment component (specialized harbors or marinas and various types of boats) [11].

Historically, in academic research, marinas have received less attention than commercial ports, with the latter often encompassing facilities within a specific area of their operation [12]. Nevertheless, marinas are gaining importance due to the positive economic impact generated by the recreational boating sector. However, the existence of marinas may also contribute to maritime pollution in their areas of operation, which can affect both climate change and the health of coastal residents [13].

Deng et al. [14] discuss the concept of green ports and state that an environmentally friendly port can be achieved through the cooperation of the government, port enterprises, and transportation enterprises. This approach can also be adopted when the development of new locations is needed, as is the case with Romania’s future plans. Crowding can be an important factor that needs special attention, mainly in urban marinas. For example, an inefficient allocation of berths based on time of stay and size of the boat can increase marina congestion and introduce delays in traffic. This is predominant during high-peak seasons such as the summer and holidays. An approach to using models and algorithms inspired by the research of commercial ports can help marina managers efficiently allocate berthing places. Tang et al. [15] studied the allocation of berths using a discretization strategy and proposed an algorithm to solve the problem, considering the time spent in port. This approach can also be extended to other practical applications, such as marina scheduling for optimal allocation of space and minimization of crowding.

All over the world, efforts are now being made to develop the marine environment by testing new methods and technologies for environmental protection. According to the industry, the biggest sustainability challenges in the marina industry are carbon footprint, fossil-fuel consumption, heavy use of plastics, and discharge of pollutants into the water [16]. An analysis of the Croatian marinas in terms of SMART technology implementation revealed that “existing solutions are mainly focused on facilitating the process of finding and booking a berth, thus saving the marina staff valuable time that can be spent more productively, dedicating more attention to the clients and insufficient attention is still being paid to sensors that should monitor changes and overall state in the marine environment, as well as indicate pollution problems” [17].

Consequently, there has been a surge in marina footprint analyses in recent years, including ecological footprint analyses, tourism carbon footprint analyses, and tourism water footprint analyses, all with the aim of integrating tourism industry development with environmental protection efforts [18,19].

Efforts are made to develop modern methods for assessing the potential environmental risks of marinas. Valdor et al. [20] propose the creation of a global atlas to estimate the potential environmental risks of marinas on water quality using the Marina Environmental Risk Assessment (MERA) procedure. The approach was applied to 105 marinas globally, confirming its utility, versatility, and adaptability as a tool to compare environmental risks, identify best practices, and understand and adjust global risks in future development.

For the Balkan area, there are papers that provide insights into the nautical tourism industry from different regions, such as Croatia and Greece, but there are few for the Black Sea. Kovačić [21] presents a case study of nautical tourism on Croatia’s coast and islands, highlighting the importance of the balanced development of nautical ports and the need to valorize the potential of nautical tourism on the principles of sustainable development. Srećko et al. [22] also examine nautical tourism in Croatia, emphasizing the importance of the efficient management of nautical tourism as a system and the development of complementary activities. Luković [23] discusses the economic development potential of nautical tourism in Europe, while Hall [24] provides a review of the coastal and marine tourism literature, noting the environmental impacts of tourism and strategies for sustainable management.

Regarding the activity of tourist ports on the Black Sea coast, Poddubnaya et al. [25] and Dreizis et al. [26] discuss the potential for transport and the development of infrastructure for coastal sea passengers and yachting along the Black Sea coast of Russia, stating that “creation of infrastructure for coastal sea passenger transport and yachting along the Black Sea coast of Russia is one of the important directions of the development potential of coastal cities.” Kazak et al. [27] discuss the possibilities of developing cruise tourism in the Black Sea regions of Russia. Bekçi [28] examines cruise tourism directed to natural and cultural landscape areas in the Black Sea Basin, proposing a management model for touristic routes that provides opportunities for people to experience different tourism activities and the development of regional tourism. These papers suggest that there is potential for the development of nautical tourism in the Black Sea region and that there are efforts to develop infrastructure and tourism products to attract tourists interested in nautical activities.

The literature field shows that, for the Black Sea coast, there are no clear data on the extent of nautical tourism development, but it recognizes that it is developing and requires an analysis that shows the dimension and impact of these activities [23].

An increased number of articles suggest that yachting and recreational sailing along the Black Sea coast of Romania is a promising activity with great potential [29]. The development of passenger water transport can be closely observed through the evolution of local marinas in the last decade.

Between 2017 and 2021, there was a slow but steady increase of about 5%, as evidenced by the share of tourist traffic (the arrivals and overnight stays in tourist accommodation structures), but we have to also consider the restrictions of the pandemic [30]. However, this potential must be harnessed sustainably to prevent negative impacts on the environment and local communities. Figure 1 shows Marina Limanu’s progress between 2011 and 2021, which led to an increase in berthing places and diversification of activities.

Figure 1.

Limanu Lifeharbour marina expansion between 2011 and 2021. Source: Marius Tudor, Limanu Lifeharbour.

One of the fundamental principles is that the development should align with the unique features of the local environment, encompassing factors such as social, economic, cultural, and environmental characteristics. Pires states that “sustainability indicators are quantitative and/or qualitative measures that aim to interrelate and assess different areas of social, environmental, economic development” [31].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Studied Marinas

Romania is a region with a low number of marinas and is at an early stage of development, which represents a huge advantage within a market that increases every year based on tourists’ appetites for new and engaging activities.

Marinas have the roles of accommodating vessels and their passengers, responding to specific navigation needs, and providing entertainment methods to customers during their stay in the port. Due to its geographic location on the Black Sea coast, Romania has a coastline with a length of 245 km consisting of three geomorphological sectors:

- In the north, the Danube Delta;

- in the middle, the Razim–Sinoe complex with sandbars that separate it from the sea;

- in the south, the Dobrogea coast, which is formed by an alternation of cliffs, beaches, and lagoons lined up between the southern part of the Chituc sandbar and the Bulgarian border.

The south region has the highest number of marinas and is the preferred zone for nautical tourism enthusiasts.

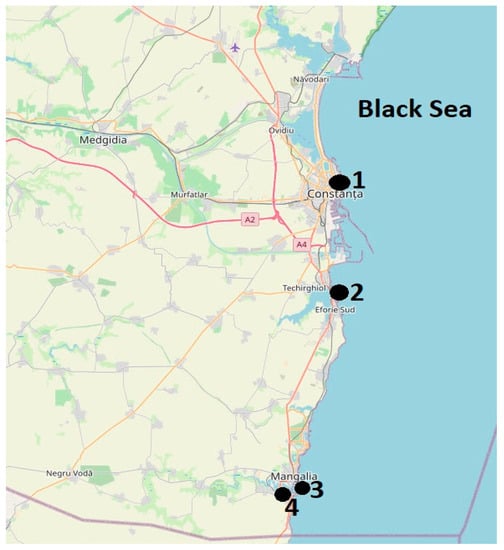

For sailors of the Romanian coastline, vessels can dock at the Tomis tourist port, located in the city of Constanta, a modern port facility for vessels in a natural setting surrounded by urban infrastructure. South of the Tomis port are the Eforie port, the Mangalia port, and the LifeHarbour Limanu marina, which also offer modern docking and maintenance facilities for pleasure craft with a limited accommodation capacity. Figure 2 displays the position of the four marinas on the Black Sea coast (1-Tomis, 2-Eforie, 3-Mangalia, and 4-Limanu).

Figure 2.

Marinas of the Black Sea coast—SE Romania.

- a.

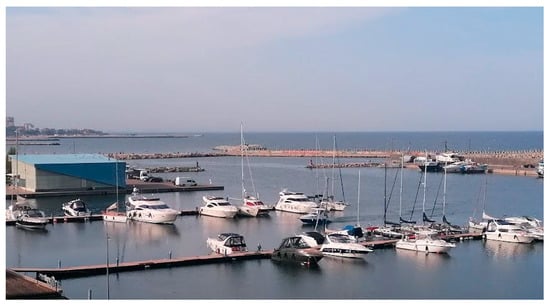

- The tourist port of Tomis, built in 1958 in the former Gulf of Dolphins, has sometimes been associated with the legend of Jason, who, on his journey from Greece to Georgia in search of the Golden Fleece, anchored in the area upon his return, where the city of Tomis was later erected. The Tomis port is the tourist and fishing port of Constanta, located in the historical center of the city (Figure 3). The port basin was created by closing the bay with two jetties:

Figure 3. Tomis port located in the urban area of Constanta city (Romania), surrounded by restaurants and close to the city’s beach. Is an iconic attraction point for tourists and locals, being the oldest coastal touristic port in the region. Source: author.

Figure 3. Tomis port located in the urban area of Constanta city (Romania), surrounded by restaurants and close to the city’s beach. Is an iconic attraction point for tourists and locals, being the oldest coastal touristic port in the region. Source: author.- The northern one, in the shape of a Y, with an initial length of 400 m, was extended in 2007 with an additional 200 m;

- the eastern one starts from the Casino promenade, over a length of 500 m.

Three out of its four sides (the eastern, southern, and western ones) have been provided with quays. Depths range from only 0.50 m in the southwestern part of the basin to 3 m in the northeastern zone. Tomis is an urban port, close to the beach, surrounded by restaurants, and situated in the most touristic area of Constanta city.

- b.

- Eforie marina, Figure 4, is the first private leisure port in Romania, built in 2004 to European standards, and it is well known among sailors, tourists, and even local residents as the Belona tourist port, which borrowed the name from the nearby hotel and lake, a mythological character from the late Roman period that embodied the wife of the warrior-god Mars, herself a deity that contributed to the wandering of travelers. It is located in Eforie Nord, 4 nautical miles to the west of the entrance to the port of Constanta, covering an area of 2 hectares and capable of accommodating light leisure boats, cruise yachts, sailboats, and sports boats.

Figure 4. Eforie—Belona touristic port. Situated 15 km south of Tomis marina and accessible from the beach of Belona offers boat berthing and facilities, including a restaurant. Source: author.

Figure 4. Eforie—Belona touristic port. Situated 15 km south of Tomis marina and accessible from the beach of Belona offers boat berthing and facilities, including a restaurant. Source: author. - c.

- Mangalia tourist port is a port on the Black Sea intended for small tourist vessels (up to 18 m in length) navigating along the Romanian coastline (Figure 5). It is the most modern tourist port in Romania, built between 2006 and 2008, based on non-repayable financial assistance from the European Union. Under the administration of the Mangalia City Hall, it is an urban port used for sea cruises, and it hosts regattas in partnership with the Varna tourist port, Bulgaria.

Figure 5. Mangalia’s port, situated close to the city center and popular promenade, is a major tourist attraction. It has been upgraded to accommodate boats, restaurant facilities and host nautical competitions [32].

Figure 5. Mangalia’s port, situated close to the city center and popular promenade, is a major tourist attraction. It has been upgraded to accommodate boats, restaurant facilities and host nautical competitions [32]. - d.

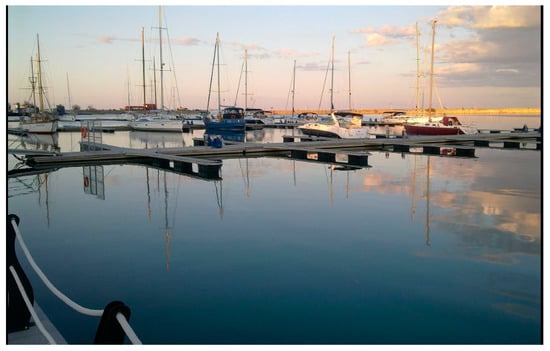

- LifeHarbour Limanu, Figure 6, is a private marina that opened in 2010, and it offers a wide range of services, including the possibility of accommodation in hotel rooms; spaces for organizing private events; concerts and small festivals; a club restaurant; and the hosting of regattas, offered for the first time in Romania.

Figure 6. Lifeharbour Marina, located near Limanu City, is the largest private tourist port in Dobrogea County. It shares an access channel with Mangalia port, providing a natural shelter for sailors. The marina offers services such as berthing, accommodation, restaurants, as well as hosting regattas, sailing school training, and seminars [33].

Figure 6. Lifeharbour Marina, located near Limanu City, is the largest private tourist port in Dobrogea County. It shares an access channel with Mangalia port, providing a natural shelter for sailors. The marina offers services such as berthing, accommodation, restaurants, as well as hosting regattas, sailing school training, and seminars [33].

Boat owners can benefit from the following diversified services:

- A boat integrity check and mooring connection verification every 6 h, 7/7 days, for each boat individually;

- protection against waves and wind, due to the marina’s location between hills;

- special preparation packages for the boat’s voyage: washing, cleaning, and the filling of water and fuel tanks;

- an anti-freezing system that allows boats to stay in the marina throughout the winter;

- room service for those who wish to have meals on board their boats;

- real-time weather information and navigation maps;

- the rental of radio and GPS equipment.

The studied marinas have the main purpose of providing shelter for pleasure boats or yachts. Secondly, they can provide entertainment, accommodation, and organizational spaces for passengers, interested individuals, and travelers.

3.2. Legislative Framework

In Romania, nautical tourism is governed by Government Decision No. 452/2003, which lays down the conditions for carrying out water recreational activities in national navigable waters in order to ensure the safety of tourists and the protection of the environment.

The legislative framework governing the operation of Romanian ports is primarily represented by a series of government ordinances and decisions, including Government Ordinance No. 22 of 29 January 1999, concerning the management of ports and waterways, the use of public domain naval transport infrastructure, the conduct of naval transport activities in ports and inland waterways; Government Ordinance No. 42 of 28 August 1997, concerning maritime and inland waterway transport; Decision No. 245 of 4 March 2003, approving the regulation for the implementation of Government Ordinance No. 42/1997 concerning naval transport; and Decision No. 452 of 18 April 2003, concerning the conduct of nautical recreation activities.

The control of water recreational activity is carried out in accordance with Government Decision 452 [34], and it is attributed to the following:

- (a)

- The Ministry of Tourism—regarding the possession of tourist authorization certificates, compliance with the accuracy of the locations of water recreational areas, and the provisions of the order.

- (b)

- The Ministry of Health and Family—regarding compliance with hygiene and sanitary rules.

- (c)

- The Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Housing, through the Romanian Naval Authority, where appropriate—regarding the existence and maintenance of the good condition of buoys, the observance of the prohibition of carrying out the activity in bad weather, and the observance of the limits of the perimeter intended for recreational navigation.

- (d)

- The Ministry of Water and Environmental Protection—regarding compliance with the legal provisions concerning the delimitation and regime of water source protection areas and protected natural areas; the protection of water, air, and soil quality; and noise levels.

- (e)

- The Ministry of the Interior—regarding compliance with regulations on the border regime.

- (f)

- Persons empowered by the mayors—regarding the holding of operating permits and compliance with the locations of water recreational areas.

It is essential for marinas to adopt sustainable practices in order to ensure the preservation of the environment and the long-term success of the industry [35,36].

The implementation of environmental protection measures should be understood, respected, and applied by marine visitors, as well as by port administrations [37]. By raising awareness of these needs, tourists can contribute to the development of sustainable nautical tourism.

In addition to the regulations imposed on recreational ports through legislative requirements and adherence to environmental protection standards, it is necessary for customers to become more environmentally conscious.

3.3. Data Collection

Given that no study in the specialized literature addresses the sustainable practices applied by Romanian marinas, a qualitative approach was preferred, as recommended by other authors when clarifications of a phenomenon are needed [38]. An exploratory study’s main goal is to gain a preliminary understanding of the topic or phenomenon being studied, which can then be used to guide further research. The results of exploratory studies are often used to generate hypotheses or research questions for further investigation. They may also be used to inform the development of new theories or concepts.

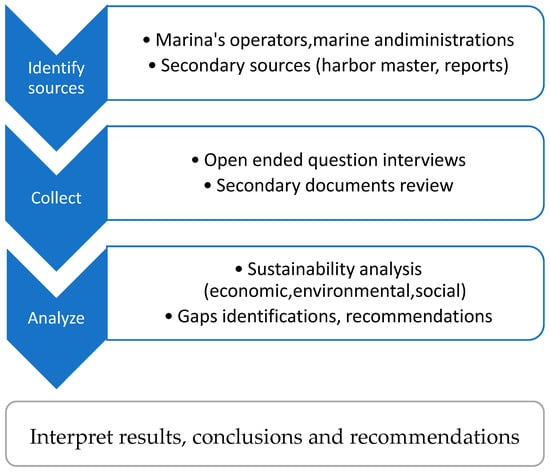

The study was structured in the following manner:

The analysis framework used was prepared by the author, and data were primarily collected through interviews with representatives of the four studied marinas. The structure is shown in Figure 7. The exploratory study used structured interviews as a data collection method, which involved asking all subjects the same open-ended questions in a specific order and wording [39]. This allowed for both free-flowing conversation and the opportunity for the interviewer to clarify any concepts with the informants.

Figure 7.

Research framework.

The interview questions were grouped into three blocks (Appendix A), and the aim was to obtain information covering the core principles of sustainable development commonly described as environmental, economic, and social [40]:

- Waste management policies;

- the use of renewable energy sources and energy efficient equipment;

- local impact;

- workforce and human resources;

- relevant industry certifications.

The author obtained data on the size of nautical activity from the Mangalia harbor master through an interview conducted as a secondary source, where they engaged in an open discussion. The questions are included in Appendix B. The interviews were carried out between May and July of 2022. Representatives from the four locations under study involved a group of fourteen individuals, out of which six were managers and eight were workers associated with the marinas. Most of the inquiries were open-ended questions aimed at obtaining information about the operational capability of the marinas, with some multiple-choice questions. The method used for data processing was centralization, followed by a comparative analysis of the information.

3.4. Analysis of Activities in Romanian Marinas

Most maritime and coastal tourist ports offer similar types of services, and in order to remain competitive, sought after, and appreciated, they must offer the most diversified services possible [41].

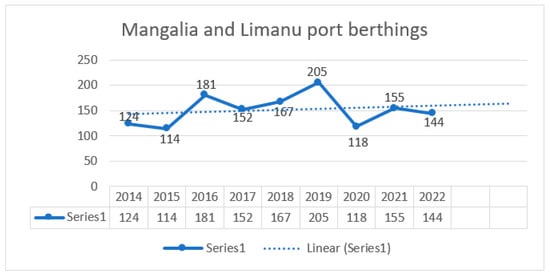

Over the last 20 years, there have been high growth rates related to nautical tourism in Romania. As shown in Figure 8, we can see that, from 2014 up to 2019, there was an increase of 65% in boats berthed in the south region at Mangalia and Limanu marinas, and this represents a positive trend. Even during the pandemic, many chose personal watercraft over staying inside or other types of tourism as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. Overall, there is an uptrend, which confirms periodic positive growth.

Figure 8.

Limanu and Mangalia boat traffic. According to the data, there has been a rising trend in boating activities, particularly between 2014 and 2019, before the pandemic. Source: author’s research.

Providing a variety of services for boats and yachts, marinas are specialized facilities typically situated along coastlines or other bodies of water, offering a secure and safe mooring spot for boat owners. Table 1 showcases the features of the studied marinas, such as their level of equipment, location, entrance, layout, pontoon layout, and berthing types. This information can help boaters and tourists choose the most suitable marina for their needs and preferences.

Table 1.

Marina’s characteristics (author’s adaptation of [36]).

Table 2 shows the variety of activities and services that marinas and nautical tourism centers can offer. The data highlight primary activities such as harboring, training, and boat building, as well as secondary activities such as fishing tourism, boat repair, and research. Other activities include moorings with associated activities such as rafting and charters, renting, and cruises, with extra activities such as sky jet services, diving expeditions, and information services. These activities and services cater to a wide range of interests and needs, providing tourists with enjoyable water-based experiences.

Table 2.

Nautical tourism activities (author’s adaptation from [23]).

3.4.1. Economical Aspect

Based on the findings (Table 3), Tomis has the highest number of berthing spots (300), which represents 44% of the total berthing spots available in all four locations. Mangalia has 22% of the total berthing spots with 146, followed by Eforie Belona with 21% (140) and LifeHarbour Limanu with 13% (60).

Table 3.

Marina operational capacities. Source: author’s own research.

In terms of usable water surface area, Mangalia has the highest area with 41% (17 ha) of the total usable water surface area in all four locations, followed by Tomis with 14% (6 ha), Limanu with 9% (3 ha), and Eforie Belona with 2% (1 ha), as displayed in Table 3.

The maximum boat length allowed also varies across the locations, with 24 m allowed in Limanu and Tomis, 18 m allowed in Mangalia, and 12 m allowed in Eforie Belona.

In terms of management, Eforie Belona and Tomis are managed by public–private partnership (PPr), representing 50% of the locations, while Limanu and Mangalia are managed by private (P) and public (Pr) management, respectively. This may indicate that Eforie, Limanu, and Tomis could be more focused on providing quality services to their customers. In contrast, Mangalia has a different type of management, which may have different priorities and focus on different aspects of the marina’s operation.

When it comes to navigating safely, it is important to know the number of available berthing spots and the maximum boat length allowed in each location. It is important to note that each location has a maximum boat length limit, with Eforie Belona having the smallest limit of only 12 m. The usable water surface area (W/B ratio) is also an important factor to consider when navigating in and out of a marina. This ratio can be used to help determine how much space is available for each boat in the marina, with a higher ratio indicating more water surface area per berthing spot.

Overall, the findings suggest that the marinas in these locations have different strengths and weaknesses, and it is important for boaters to consider their specific needs when choosing a marina. Factors such as berthing spots, usable water surface area, maximum boat length, and management type should all be taken into account to ensure a safe and enjoyable boating experience.

3.4.2. Findings on Environmental Practices

Water supply is available in all locations. All locations have access to shore power for electricity provided by the local electricity company. Waste and garbage, where collected, are further delivered to local recycling companies. The use of renewable energy sources (RESs) and desalination and rainwater recovery systems is not available in any location. None of the studied marinas have fuel-supply-approved facilities.

Mangalia and LifeHarbour Limanu have systems for waste oil and ballast water disposal, as well as pollution prevention equipment. Tomis and LifeHarbour Limanu provide boat maintenance services and have green spaces. No location has ISO14001 or Blue Flag environmental certifications.

Based on the data displayed in Table 4, it can be concluded that the availability of certain services varies between locations, and some locations have a more comprehensive set of services than others. The lack of fuel supply facilities, use of renewable energy sources, and environmental certifications may be areas for improvement in all locations. The presence of waste disposal and pollution prevention equipment is important for safety and environmental protection. The availability of boat maintenance services and green spaces may be a factor that attracts boaters to certain locations.

Table 4.

Comparison of the different services available in four different locations. Source: author’s survey based on own research.

The assessment of carbon impact involves an evaluation of the potential sources of carbon release, followed by the quantification of their respective magnitudes. It is customary for tourist ports to have a comparatively minor impact on carbon emissions since the quantity of fuel consumed for the provision of services to sailboats is generally lower. However, it is important to note that the ecological context in which these ports operate is exceedingly delicate, and carbon emissions can inflict significant harm to the environment.

Factors affecting the carbon footprint:

- Energy consumption (electricity and fuel based);

- number of workers in the marina, distance traveled and type of vehicle used;

- number of visitors, distance traveled and type of vehicle used;

- activities carried out by boats;

- production of hot water;

- number of suppliers, frequency of visit, and type of vehicle used;

- frequency of waste collecting truck visits.

The primary objective of this study was not to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the carbon footprint. Nevertheless, the study provides a valuable basis for future research in this area.

Such research could provide critical insights into the environmental impact of these activities and identify strategies to reduce their carbon footprint.

3.4.3. Social Assessment

Based on the given data, we can analyze the social impact of the marinas on their respective communities. The collected data is displayed in Table 5. Firstly, we can see that all marinas provide some level of recreational facilities and have the capability of hosting various events and regattas, which can contribute positively to the social life of the surrounding area. This is also a strong point for sailors to visit the ports and can create a lot of traction for nautical sports enthusiasts.

Table 5.

Social characteristics. Source: author’s own research.

In terms of Internet connection, all marinas, except for Mangalia and Tomis, have this service, which can be important for communication and staying connected. Additionally, road access and parking are available in all marinas, which makes them accessible to visitors and locals alike. All marinas have boat ramps or cranes, which are crucial for launching and retrieving boats, making it easier for people to enjoy water activities.

In terms of security, only Eforie Belona and Limanu have CCTV cameras, which can improve safety for visitors and their boats. However, all marinas have received positive review scores, indicating that visitors are generally satisfied with their experiences.

Lastly, the absence of mobile app access for reservations and real-time status updates could be seen as a negative impact on the convenience of the marinas. Overall, the social impact of these marinas appears to be positive, with various facilities and services available for visitors to enjoy, but there is room for improvement in certain areas.

4. Results

According to several scholars, “sustainable marina management is related, first and foremost, to the environmental impact generated by marina operations, thus to the pollution sources” [42].

Protecting the environment is particularly important in coastal natural areas, such as the Romanian Black Sea coast, which has been classified by the IMO’s MARPOL convention as a special navigation area and is a Natura 2000 protected natural area [43,44]. The operation of port facilities for the delivery of waste from ships is regulated by EU Directive 2019/883, adopted by the Romanian government through Ordinance 9/2022 [45]. In the maritime industry, the closer a vessel is to the shore, the stricter the environmental protection rules, which means that recreational nautical tourism, mainly operating in the coastal zone, requires careful organization and complete acceptance and compliance with the rules by all participants.

Due to the activities carried out in the studied marinas, various pollutants can be produced that require specific treatment to maintain a clean and healthy environment. Poor planning by tourist port administrations regarding boating activities can lead to the deterioration of the marine environment and the quality of the water in the port basin [46].

Typically, each marina administration must develop its own programs for waste management, and these must be tailored to their specific needs and circumstances. This requires resource management in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be met while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biodiversity, and life support systems [47].

The waste resulting from the mooring of recreational boats in the studied marinas can be classified as follows:

- Combustibles and hydrocarbons;

- hazardous materials;

- dirty water;

- solid waste.

Combustibles, oils, and other hydrocarbon-based wastes primarily come from bilges, tanks, containers, or maintenance operations on boats. Generally, refueling operations represent the primary sources of hydrocarbon contamination, and there is a real risk of accidental spills that cause serious environmental hazards. For example, gasoline spills can lead to explosions and fires.

Engine repair and maintenance work presents another possible source, involving the removal of oil from the crankcase and the handling of environmentally harmful substances like solvents, anti-freeze, paint, detergents, and residues during ship hull cleaning.

Following the analysis of the responses received, marina administrators comply with environmental protection policies imposed by national legislation. Although the vast majority have adopted minimal environmental protection measures, there are also cases where there is a heightened concern for and interest in protecting nature, as we could see in the Limanu marina.

The case of Mangalia port offers an interesting example of contemporary development initiatives aiming to enhance the quality of services while concurrently safeguarding the environment. In 2011, the project received a significant investment of approximately EUR 4 million from European funds, resulting in the creation of 146 berths, 10 of which accommodate large ships measuring 18 m in length, in addition to roadways, parking spaces, and terraces. Funds were prioritized to improve environmental protection through the installation of new, environmentally friendly floating quays, cleaning the water basins of old structures, green landscaping, installing energy-efficient lighting systems, and improvements to the waste collection systems.

The modernization efforts led also to generating revenues of more than EUR 100,000 in its first year, a sum that has contributed to the local budget. Furthermore, the improvements have facilitated the growth of the water sports sector by promoting the attraction of regatta organizers and developing supplementary sources of income via rental or user fees.

Household waste is stored and sorted in separate containers, which are subsequently taken over by local waste management companies. Waste and recyclable materials are stored in bins or specially labeled containers located in designated areas within the port. The policies and regulations for waste management are posted on site, as seen in Figure 9. Tourist port administrations provide customers with spaces for collecting household waste from boats. Toxic, polluting materials, such as paints, oils, gasoline, and flammable substances, can be deposited in special containers made available to customers (in Mangalia and Limanu) and collected by sanitation services. Within all marinas, the discharge of domestic, sewage, bilge, toilet, and collector tank water is prohibited. There are no facilities for collecting this type of water provided by the port administrations surveyed.

Figure 9.

Display of marina policies. Source: author.

Boat washing is permitted within tourist ports and must be carried out with fresh water through hoses equipped with mechanical shut-off valves, infrequently, and using only biodegradable cleaning products. Washing should be carried out no more than once a week and only for the removal of dust. Maintenance work on boats or the cleaning of marine organisms is not allowed in any of the surveyed marinas. It is noteworthy that, in the case of Mangalia and Tomis port, located in an urban area, there are specified legal restrictions on the use of boat engines, radio equipment, and other machinery that can produce loud noise, thereby limiting noise pollution during the nighttime.

Regarding water and electricity supply systems for boats, appropriate facilities are available within the marinas. On floating pontoons or on the quay, boat installations can be connected to sources of water and electricity. In all the studied marinas, electricity is delivered by the local network and is not produced from green sources.

The fueling of vessels is carried out with canisters, as no marina has special fueling facilities for boats. In some cases, there are special docks where refueling is carried out, as is the case in Mangalia, but even then, there are no fixed pumping installations for bunkering. Within marinas, harmful, toxic, and environmentally damaging substances cannot be introduced without the administrator’s approval and only if stored in specially sealed containers. Certain chemicals, such as acetylene and methyl sulfate, are strictly prohibited.

Limanu marina has specialized equipment that can be used in the case of accidental hydrocarbon pollution in the port basin, thus ensuring a rapid response until competent authorities intervene. Customers are informed through various methods, especially posters and signs in the port area. They are informed about environmental protection rules, conduct, and conditions for staying in the port. Approved regulations containing information on stay rules are also available when concluding contracts with the port administration.

Aside from compliance with national regulations and in order to demonstrate high levels of quality, safety, and environmental care, operators of tourist ports rely on independent classification organizations recognized at the European level. The most important certifications in the field are: Blue Flag, Gold Anchor, ISO9001, and ISO14001.

These certifications serve as evidence of the commitment of tourist port operators to providing high-quality services while also protecting the environment. They also provide assurance to customers that the ports that they visit meet recognized standards for quality, safety, and environmental responsibility.

None of the surveyed marinas holds any internationally renowned accreditations or is affiliated with any international organizations in the field. Based on the interview response, the marina representatives have future plans to obtain certification classes, but a definitive timeline was not given. However, according to customer evaluations based on reviews given through Google, the quality of services is appreciated, with the scores of all marinas in this study being similar and exceeding 4.3 stars.

Regarding waste management from recreational activities, no more attentive waste recycling policies were encountered, and waste management is entirely left to the local sanitation operator. There are no mobile or fixed facilities for collecting dirty water, toilet water, oils, or batteries from boats.

For the sustainability of resources, such as freshwater consumption, the only source is the local network. No facilities are used to desalinate seawater or collect rainwater. Although the need for renewable energy is recognized, solar systems are not used to produce it, even though the need for electricity is highest during the summer when we have plenty of sunny days. Instead, low-consumption LED lighting systems are used.

Financing should be encouraged for the installation of renewable energy production systems, of which the most suitable for this specific marine activity are solar panels. These sustainable marketing practices can make a difference in the quality of services offered by marinas and can help build a serious and solid reputation. Those who manage marina activities need to understand that investments in renewable systems to save natural resources can bring a significant commercial advantage and can be a serious element of competitive commercial differentiation.

The study found that all marinas provide some level of recreational facilities and have the capability of hosting various events and regattas, which can contribute positively to the social life of the surrounding area. This is also a strong point for sailors to visit the ports and can create a lot of traction for nautical sports enthusiasts.

5. Conclusions and Implications

The goal of this research was to identify the features of the Romanian Black Sea coast marinas and evaluate aspects of sustainable management.

The environment, the natural landscape, and accessibility are elements that primarily determine the success of such an economic activity. The lack of interest in protecting the environment and respecting nature in the area of tourist ports can have an extremely negative impact on the business and can lead to the withdrawal of the necessary operating permits. Conversely, a continuous concern for environmental protection over a long period of time builds a reputation of good practice and increases the public’s interest in the respective tourist port.

This research employed a mixed-methods approach, utilizing both qualitative and quantitative analysis methods. The qualitative method employed thematic analysis as the primary means of data analysis. Data were primarily collected through interviews conducted with representatives from marinas. Secondary data collection methods included observation and the collection of data from naval authorities or public documents.

The analysis of nautical tourism and Black Sea marinas led to the identification of key factors for their future development and opportunities.

The research findings suggest the presence of the following deficiencies:

- There exists a potential for standardization and awarding systems that has yet to be fully utilized, as they can serve as a beneficial standard for establishing a sustainable assessment system, as can be seen in similar studies [48].

- Slow energy transition: the transition to renewable sources of energy should be made rapidly, especially since companies in the European Union can receive substantial assistance for the transition to producing energy from solar panels. The main obstacle identified was the lack of information on how to access the funding.

- There is an absence of desalination systems or rainwater recovery systems, which have been identified as natural resource conservation methods.

- There is a lack of active online presence detailing the activities of the marinas, policies, and programs.

- There is a lack of new technological resources, such as apps for berth reservations and live data visibility. In other similar studies, Gracan et al. [49] highlight the importance of digital services in the yacht charter segment by stating that “advertising on the Internet is the most important form of advertising for charters in nautical tourism, with a share of over 50%”, indicating the importance of digital channels and indirect digital business models for charter activities in nautical tourism. In Kalči’s study, it was revealed that “most participants indicated that they prefer to book a yacht charter over the Internet rather than via telephone or face-to-face contact” [50].

- Studies regarding the sustainability of the marinas and methods of becoming more energy efficient revealed that insufficient information and difficulty in accessing investment funds are the main obstacles [51]. This could be seen also in the studied local marinas.

Based on the research data, a SWOT analysis was conducted on the marinas’ activity and nautical tourism development, and the results are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

SWOT analysis. Source: author’s research.

While the locations under consideration have several strengths, they also present several weaknesses that need to be addressed to attract more tourists interested in nautical activities. One of the primary weaknesses of the locations is their limited capacity for accommodating large vessels. This can limit the number of tourists who would like to visit the location, especially those who prefer to travel on large ships. Another significant weakness is the insufficient information for tourists about offers, which can deter potential tourists. Tourists often require detailed information about the facilities and services available, including the types of activities they can participate in, the costs, and the equipment provided. Without this information, tourists may not feel confident in choosing the location for their nautical tourism activities. A clear and defined strategy for the development of nautical tourism is another significant weakness. A lack of a clear and defined strategy can lead to confusion and inefficiency in attracting tourists.

The absence of certifications for services and facilities is another weakness. Certifications are essential for ensuring that services and facilities meet specific standards, and they provide a measure of quality assurance to tourists. The lack of certifications can create uncertainty about the quality of the facilities and services provided, leading to a negative impact on the tourism industry. One of the most significant opportunities is the untapped potential for nautical tourism. The involvement of tourism agencies can help raise awareness about the potential for nautical tourism and attract more tourists. Hosting international regattas is another opportunity that can bring a large number of tourists and promote the location as a top destination for nautical tourism.

The development of auxiliary services such as boat repair, equipment sales, and maintenance can also provide a more complete nautical tourism experience for tourists. This can attract sailors interested in longer stays and increase their spending, contributing to the local economy. Organizing thematic tours, dolphin watching, and scuba diving can also help attract a diverse range of tourists interested in different types of nautical activities.

Finally, the lack of modern IT facilities such as apps for reservations and real-time data can make the location less attractive to tech-savvy tourists. Modern tourists rely heavily on technology to plan their trips and activities.

The study evaluated the operational capacities and policies implemented by tourist ports and relevant stakeholders, identifying the strengths and weaknesses of the current system. The study also assessed sustainable practices in relation to the environmental, social, and economic systems, with a focus on environmental protection, the use of renewable energy sources, and the implementation of quality management standards.

The research identified gaps and highlighted areas that require improvement, subsequently providing recommendations to enhance sustainability. The findings can guide policymakers and stakeholders in developing practices that can promote the growth of recreational nautical transport in Romania while ensuring the sustainable development of the sector. In general, the growth of Romanian marinas should be pursued responsibly, considering the economic, social, and environmental effects of their operations.

This study has various limitations that can reduce the potential generalization of the results and scope of its conclusions. Firstly, it is based on four marinas of small to medium size with a limited number of visitors, who mainly come during the summer. Secondly, the survey was focused on the predominant factors, which generally show the status quo. A limited amount of data is available and shared by the involved parties, but it would be worthy to analyze in depth the revealed factors of this study since achieving sustainability is clear and will be the main challenge in the upcoming years.

Funding

This work has been funded by the European Social Fund from the Sectoral Operational Programme Human Capital 2014–2020, through the Financial Agreement with the title “Training of PhD students and postdoctoral researchers in order to acquire applied research skills—SMART”, Contract no. 13530/16.06.2022—SMIS code: 153734.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. This research used an anonymous questionnaire survey in public places. No personal data that could directly or indirectly identify the participants were obtained during the research process.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Interview questionnaire:

The interview was structured to cover the three core principles of sustainable development and to gather data about the size of the marina’s activity. The following questions focus on the:

- Economical capacity data

- Measurement of the nautical activity

- Impact on the environment

- Protection measures to minimize the environmental damage

- Social awareness

- Q1.

- What is the capacity of marina and the size of boats that can accommodate?

- Q2.

- What investments has the marina made in facilities and amenities, and how have these investments impacted revenue and customer satisfaction?

- Q3.

- What plans does the marina have for future growth and expansion, and how will these plans impact its economic performance?

- Q4.

- What measures has the marina taken to minimize its carbon footprint and reduce its impact on the local environment, such as using renewable energy sources or implementing recycling programs?

- Q5.

- What steps has the marina taken to minimize noise pollution and other forms of disturbance?

- Q6.

- How does the marina manage its waste disposal, and what steps has it taken to ensure that hazardous or toxic materials are handled and disposed of safely and responsibly?

- Q7.

- What are the environmental practices and policies used by the marina?

- Q8.

- What steps has the marina taken to minimize noise pollution and other forms of disturbance to local wildlife?

- Q9.

- What steps has the marina taken to reduce light pollution and preserve the natural nighttime environment, such as using energy-efficient lighting fixtures or implementing policies to minimize outdoor lighting at night?

- Q10.

- Do you have knowledge about methods to decrease energy expenses and enhance energy effectiveness?

- Q11.

- Do you have knowledge about the measures and funds in the European Union that aim to encourage energy efficiency?

- Q12.

- How does the marina engage with the local community, and what steps has it taken to promote social responsibility and community involvement?

- Q13.

- What is the marina’s impact on local businesses, and how has it contributed to the local economy in terms of job creation and revenue generation?

- Q14.

- How does the marina ensure the safety and security of its customers and employees, and what steps has it taken to promote a safe and welcoming environment for all?

Appendix B

These questions were used to gather data about the size and type of sailboats entering Mangalia port:

- Q1.

- How many recreational boats are recorded as per a monthly bases?

- Q2.

- What is the size of the boats?

- Q3.

- Type of boats?

- Q4.

- Can you share some opinions about the development of nautical tourism in the region?

- Q5.

- Can you share your opinion on the legislation and regulatory frameworks for the regulation of nautical recreational transport?

References

- Luck, M. (Ed.) Nautical Tourism: Concepts and Issues, Chapter III; Cognizant Communication Corporation: Elmsford, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 1-882345-50-9. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Vázquez, R.M.; Milan Garcia, J.; De Pablo Valenciano, J. Analysis and Trends of Global Research on Nautical, Maritime and Marine Tourism. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryzhak, O.; Akhmedova, O.; Aldoshyna, M. The Prospects of the marine and coastal tourism development in Ukraine. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 153, 03009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizielewicz, J.; Luković, T. The Phenomenon of the Marina Development to Support the European Model of Economic Development. TransNav. Int. J. Mar. Navig. Saf. Sea Transp. 2013, 7, 461–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facts & Figures. Available online: https://www.europeanboatingindustry.eu/about-the-industry/facts-and-figures (accessed on 16 July 2022).

- Available online: http://publications.europa.eu/resource/cellar/ab0bfa73-9ad1-11e6-868c-01aa75ed71a1.0001.01/DOC_1 (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Available online: http://www.cjc.ro/dyn_doc/turism/Strategia_jud.Constanta_Faza2.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- EU. Directive (EU) 2019/883 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019. March 2019. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, 62, 116–142. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačić, M.; Silveira, L. Nautical tourism in Croatia and in Portugal in the late 2010′s: Issues and perspectives. Pomorstvo 2018, 32, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Conserve and Sustainably Use the Oceans, Seas and Marine Resources for Sustainable Development; Department of Economic and Social Affairs. 2022. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal14 (accessed on 21 January 2023).

- Paker, N.; Altuntas, C. Customer segmentation for marinas: Evaluating marinas as destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Pérez, N.; Rodríguez-Martín, J.; García, C.; Ioras, F.; Christofides, N.; Vieira, M.; Bruccoleri, M.; Santamarta, J.C. Comparative study of the environmental footprints of marinas on European Islands. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiev, M.; Winebrake, J.J.; Johansson, L.; Carr, E.W.; Prank, M.; Soares, J.; Vira, J.; Kouznetsov, R.; Jalkanen, J.-P.; Corbett, J.J. Cleaner fuels for ships provide public health benefits with climate tradeoffs. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, Q. Influence mechanism and evolutionary game of environmental regulation on green port construction. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Ji, B.; Fang, X.; Yu, S.S. Discretization-Strategy-Based Solution for Berth Allocation and Quay Crane Assignment Problem. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DockMaster Software. Six Sustainability Practices for Marinas to Follow in 2023. DockMaster Marine Software. 2022. Available online: https://www.dockmaster.com/blog/six-sustainability-practices-for-marinas-to-follow-in-2023 (accessed on 7 May 2023).

- Maglić, L.; Grbčić, A.; Maglić, L.; Gundić, A. Application of Smart Technologies in Croatian Marinas. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2021, 10, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antequera, P.D.; Jaime, D.; Abel, L. Tourism, transport and climate change: The carbon footprint of international air traffic on Islands. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annis, G.M.; Pearsall, D.R.; Kahl, K.J.; Washburn, E.L.; May, C.A.; Taylor, R.F.; Cole, J.B.; Ewert, D.N.; Game, E.; Doran, P.J. Designing coastal conservation to deliver ecosystem and human well-being benefits. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdor, P.F.; Juanes, J.A.; Kerléguer, C.; Steinberg, P.D.; Tanner, E.; Macleod, C.; Knights, A.M.; Seitz, R.D.; Airoldi, L.; Firth, L.B.; et al. A global atlas of the environmental risk of marinas on water quality. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovačić, M. Sustainable development of nautical tourism in Croatia. In NewTrends Towards Mediterranean Tourism Sustainability, 1st ed.; Rosalino, L., Silva, A., Abreu, A., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers, Inc.: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Srećko, F.; Gržetić, Z. Nautical tourism—The advantages and effects of development. Sustain. Tour. III 2008, 115, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, T. Nautical Tourism and Its Function in the Economic Development of Europe, Visions for Global Tourism Industry—Creating and Sustaining Competitive Strategies; Kasimoglu, M., Ed.; InTech: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; ISBN 978-953-51-0520-6. Available online: http://www.intechopen.com/books/visions-for-global-tourismindustry-creating-and-sustaining-competitive-strategies/nautical-tourism-in-the-function-of-the-economicdevelopment-of-europe (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Hall, C.M. Trends in ocean and coastal tourism: The end of the last frontier? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2001, 44, 601–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddubnaya, T.N.; Zadneprovskaya, E.L. Yacht Tourism on the Azov-Black Sea Coast of Russia as a Factor of Tourist Attractiveness of the Region. Regionology. Russ. J. Reg. Stud. 2022, 30, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreizis, Y.; Potashova, I. Yachting and coastal marine transport development in Black Sea coast of Russia. MATEC Web Conf. 2018, 170, 05007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, A.; Oleinikov, N.; Selivanov, V.; Nekhaychuk, D.; Borovsky, V.; Filimoshkina, I.; Galstyan, A.; Ilyasova, A. Research of the possibilities of the development of cruise tourism in the Black Sea regions of Russia. E3S Web Conf. 2022, 363, 01045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekci, B. Cruise tourism directed to natural and cultural landscape areas in the Black Sea Basin. J. Multidiscip. Acad. Tour. 2022, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musteaţa, M.P.; Simon, T. Promoting Nautical Tourism in Romania. Rev. Roum. Géogr./Rom. J. Geogr. 2013, 57, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Bogan, E.; Simon, T.; Cercleux, A. Sea-coast Tourism Activity in Romania during the Pandemics. Ann. Univ. Buchar. Geogr. Ser. 2022, 1, 84–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno Pires, S. Indicators of sustainability. In Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research; Michalos, A.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 3209–3214. ISBN 978-94-007-0752-8. [Google Scholar]

- Source: Gratian Alinei. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portul-Turistic-Mangalia-1.jpg (accessed on 24 February 2023).

- Source: Marius Tudor. Available online: https://www.mangalianews.ro/2022/10/23/save-the-date-18-20-noiembrie-2022-winterization-party-la-marina-limanu-event-de-get-together-la-finalul-sezonului-2022/ (accessed on 21 December 2022).

- HG 452 18/04/2003—Portal Legislativ. Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocumentAfis/43366 (accessed on 18 January 2023).

- Poletan Jugović, T.; Agatić, A.; Gračan, D.; Šekularac-Ivošević, S. Sustainable activities in Croatian marinas—Towards the “green port” Concept. J. Marit. Stud. 2022, 36, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tselentis, V.; Dragović, B.; Nikitakos, N.; Škurić, M.; Ćorić, A. Integrative model of sustainable development for marinas and nautical ports. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Shipping, Intermodalism & Ports–ECONSHIP, Chios, Greece, 24–27 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Martín Rojo, I. Economic development versus environmental sustainability: The case of tourist marinas in Andalusia. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2009, 2, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCutcheon, D.M.; Meredith, J.R. Conducting Case Study Research in Operations Management. J. Oper. Manag. 1993, 11, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragović, B.; Tselentis, B.S.; Škurić, M.; Meštrović, R.; Papan, S. The Concept of Sustainable Development to Marina. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference RaDMI 2014, Topola, Serbia, 18–21 September 2014; Volume 1, pp. 340–345. [Google Scholar]

- Purvis, B.; Mao, Y.; Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: In search of conceptual origins. Sustain. Sci. 2019, 14, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, J.C.; Raga, G.B.; Arévalo, J.; Baumgardner, D.; Córdova, A.M.; Pozo, D.; Calvo, A.; Castro, A.; Fraile, R.; Sorribas, M. Properties of Particulate Pollution in the Port City of Valparaiso, Chile. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 171, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houy, C.; Reiter, M.; Fettke, P.; Loos, P. Towards Green BPM—Sustainability and Resource Efficiency through Business Process. In Proceedings of the Business Process Management Workshops: BPM 2010 International Workshops and Education Track, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 13–15 September 2010; Revised Selected Papers 8. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 501–510. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/index_en.htm (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- International Maritime Organization. Marpol Consolidated Edition 2011: Articles Protocols Annexes and Unified Interpretations of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships 1973 As Modified by the 1978 and 1997 Protocols, 5th ed.; IMO: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Directive 2019/883 of November 2000, as Adopted to the Romanian Government by the Ordinance No.9/01/2022 (OFFICIAL MONITOR No 94 of 31 January 2022). Available online: https://legislatie.just.ro/Public/DetaliiDocument/245908 (accessed on 12 January 2023).

- Dolgen, D.; Alpaslan, M.N.; Serifoglu, A.G. Best Waste Management Programs (BWMPs) for marinas: A case study. J. Coast. Conserv. 2003, 9, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Sustainable tourism development: A critique. J. Sustain. Tour. 2003, 11, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, R.; Benevolo, C. Sustainability in the Mediterranean tourist ports: The role of certifications. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracan, D.; Gregoric, M.; Martinic, T. Nautical Tourism in Croatia: Current Situation and Outlook. In Proceedings of the 23rd Biennial International Congress, Tourism and Hospitality Industry 2016, Trends and Challenges, Opatija, Croatia, 28–29 April 2016; pp. 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kalcic, N. Yacht Charter in Portugal-Developing a Business Model for a Sailing Charter Company; NOVA—School of Business and Economics: Carcavelos, Portugal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Trstenjak, A.; Žiković, S.; Mansour, H. Making Nautical Tourism Greener in the Mediterranean. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).