Abstract

There has been extensive research on the association between environmental attitudes and outdoor recreation (or nature-based leisure activities) since the 1970s. There is now considerable evidence to support the claim that spending time in nature leads to greater connectedness to nature and thereby greater pro-environmental attitudes and behavior. However, there is an absence of research focused specifically on the association between outdoor recreation and concern for climate change, which is arguably the most pressing environmental problem facing the world today. We build on previous research by using the 2021 General Social Survey and structural equation modeling to analyze the association between frequency of engaging in outdoor recreation and concern for climate change among adults in the United States, with special attention to the role of enjoying being in nature. Controlling for other factors, we find that frequency of outdoor recreation has a positive, significant effect on climate change concern, but only indirectly via enjoyment of nature. Individuals who more frequently engage in outdoor recreation activities tend to report a greater sense of enjoyment of being outside in nature, and this enjoyment of nature is associated with a higher level of concern for climate change.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have initiated a surge in outdoor recreation (i.e., nature-based recreational or leisure activities) among Americans and seems to be driven largely by the pursuit of improved health and well-being [1]. Drawing a connection to another serious global threat, it has been proposed that such increased participation in outdoor recreation may have the added benefit of bringing about greater concern for climate change by increasing a sense of connection to nature [2,3]. Social scientists have studied the individual and contextual factors influencing climate change beliefs and attitudes in depth [4,5,6,7] and have extensively examined the association between outdoor recreation and various environmental attitudes [8]. However, there is little to no empirical research directly examining the association between outdoor recreation and concern specifically for climate change, as noted in a recent review [9]. We build on prior research to investigate, using nationally representative data from the General Social Survey for the year 2021, the association in the United States between frequency of engaging in outdoor recreation and concern for climate change with special attention to the role of enjoying being in nature.

In the mid-1970s, sociologists Dunlap and Heffernan were among the first to empirically examine the relationship between outdoor recreation and environmental concern, which they measured with multiple survey items asking respondents to prioritize government expenditures on various aspects of environmental quality, from natural resource protection to controlling and preventing air and water pollution [10]. They tested three hypotheses: First, that individuals who participate in outdoor recreation activities would more frequently express greater environmental concern. Second, that this relationship would be stronger for appreciative activities (e.g., camping, hiking) than for consumptive activities (e.g., hunting, fishing). Third, that the relationship between outdoor recreation and environmental concern would be strongest for issues most directly related to these activities (e.g., protection of natural resources and areas) and weakest for more distant or abstract issues. They found weak support for the first hypothesis and stronger support for the other two in their analysis of a survey of residents of Washington state administered in 1970. Their main argument was that appreciative outdoor recreation activities lead to greater environmental concern because it exposes people directly to the natural environment and threats to it, promotes commitment or attachment to specific natural areas, encourages development of a subjective preference for a more pristine natural environment, and increases their exposure to environmental education efforts [10].

Over the years, other scholars have sought to confirm Dunlap and Heffernan’s findings or elaborate on them, with mixed results [8,11,12,13,14]. For example, Jackson [15] conducted a survey of residents of Alberta, Canada and determined that outdoor recreation is associated with greater concern for the environment, the relationship is stronger for appreciative activities than for consumptive and mechanized activities (e.g., snowmobiling), and the strongest associations are with concern for environmental issues specific to outdoor recreation (e.g., maintaining and protecting wilderness and public lands) rather than more general environmental concern. In one of the few studies using nationally representative survey data, Teisl and O’Brien’s [16] results suggest that participation in outdoor recreation is positively associated with concern for the environment and pro-environmental behavior and confirmed that the strength and direction of this association varies considerably across different types of outdoor activities. They find that in general appreciative outdoor recreation activities are more strongly associated with pro-environmental attitudes and behavior than other types of outdoor recreation such as consumptive or mechanized [16]. In a recent review of the literature, Rosa and Collado summarize the research on the topic of how experiences in nature influence environmental attitudes and note the following [17] (p. 2): “appreciative activities in nature relate to enjoying the natural environment (almost) without altering it through self-propelled non-mechanized activities (e.g., surfing, birdwatching, hiking, etc.). Research evidence suggests that appreciative experiences in nature are the ones more strongly linked to pro-environmentalism.”

Importantly, research shows that it is not just participating in outdoor recreation, but also the emotional and affective aspect of time spent in nature that matters [18,19,20]. For example, Porter and Bright [21] found in their study of Washington state residents that when it comes to predicting environmental concern, the meaning ascribed to non-consumptive outdoor recreation (or motivation for participating) is more important than merely how frequently a person participates in these activities, and fully mediated the effect of participation on concern. They found that participation in outdoor activities for enjoyment of nature or learning were particularly strongly associated with greater concern compared to other aspects of meaning [21]. Furthermore, in the environmental psychology literature, researchers have demonstrated that emotional affinity for nature is an outcome of past and present experiences in natural environments that is also associated with greater willingness to engage in pro-environmental behavior [22,23]. A number of studies have found evidence that spending more time outside in nature is associated with a greater sense of connectedness to nature, especially in an emotional sense, which is in turn associated with greater environmental concern [23,24,25]. Overall, as Deville et al. note in their extensive review of the literature on this topic [9] (p.1), “Substantial evidence from observational and intervention studies indicates that overall time spent in nature leads to increased perceived value for connectedness to nature and, subsequently, greater pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors (PEAB).”

As noted previously, there is little to no existing research explicitly examining the empirical association between outdoor recreation, or time spent in nature, and climate change concern in particular [9]. Some previous studies indicate that outdoor recreation is more strongly associated with concern for environmental problems that directly affect these activities (such as developing natural areas) and to a lesser degree with more abstract or distant environmental threats, such as climate change [10,15,26], so it is not clear if this observed association would hold for climate change concern. However, one recent study indicates this is a promising area of research: Cunningham, McCullough, and Hohensee [27] detected a county-level association in the United States between the proportion of residents engaging in physical activity (not necessarily outdoors) and belief that climate change personally affects them as well as a measure of support for climate policy.

Building on Cunningham et al. [27] and other prior studies discussed above, we primarily hypothesize that concern for climate change is higher among individuals who more frequently engage in outdoor recreation (or nature-based leisure activities). Given that the emotional component of time spent in nature has been found to be especially important when it comes to feeling connected to the environment and thus more concerned about environmental problems, we also examine how individuals’ degree of enjoyment of their experiences and time spent in nature play a role in the connection between outdoor recreation and climate change concern. Thus, our secondary hypothesis is that individuals who more frequently engage in outdoor recreation will report greater enjoyment of being outside in nature and this will also be associated with greater concern for climate change.

Primary Hypothesis.

Outdoor recreation frequency is positively and directly associated with climate change concern.

Secondary Hypothesis.

Outdoor recreation frequency has a positive indirect association with climate change concern via enjoyment of being outside in nature.

2. Materials and Methods

The data for this study come from the 2021 General Social Survey (GSS) Cross-Section, which was administered from December 2020 to May 2021 to a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States as a push-to-web survey, supplemented with phone interviews as a secondary mode of administration [28]. The final sample size for the 2021 GSS Cross-Section was 4032, but the number of valid responses varies by question; for our analysis, the sample size is 1401. This omnibus survey included questions that asked respondents about their concern for climate change as well as questions about feelings and time spent outside in nature. In addition, this survey includes items about one’s political orientation, the perceived impact of extreme weather events, and sociodemographic characteristics. We describe the variables below and more information can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

The dependent variable, climate change concern, is constructed on responses to three survey questions about the perceived impact (good or bad) on the world, the perceived impact (good or bad) on America, and the perceived danger of a rise in the world’s temperature for the environment. For the first two variables, responses range from extremely good (1) to extremely bad (10). The response to the third variable ranges from not dangerous at all for the environment (1) to extremely dangerous for the environment (5). Since there were multiple items in the GSS that tap into different aspects of the commonly studied perceived risk dimension of climate change concern, we use factor analysis to estimate a single latent variable [29]. We use confirmatory factor analysis to test for measurement reliability, and the results show that the standardized factor loadings of all three individual items are statistically significant and the loadings are above 0.6 and significant (p < 0.001); model fit could not be evaluated since this is a just-identified model and thus the degrees of freedom for the χ2 goodness of fit test was zero. However, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient is 0.85, indicating adequate reliability of using these three items as a single measure of one’s climate change concern.

There are three questions related to outdoor recreation. The first question asks: In the last twelve months how often, if at all, have you engaged in any leisure activities outside in nature, such as hiking, bird watching, swimming, skiing, other outdoor activities, or just relaxing? Responses, which we have reverse coded to ease interpretation, include never (1), several times a year (2), several times a month (3), several times a week (4), and daily (5). This measure of outdoor recreation best reflects the category of activities described as appreciative [8,10,17]. The second question asks: How much, if at all, do you enjoy being outside in nature? Responses include not at all (1), to a small extent (2), to some extent (3), to a great extent (4), and to a very great extent (5). The third question asks: Do you or your husband/wife/partner go hunting? We recoded this item to be a dummy variable where 1 = yes, respondent does or both do and 0 = no, neither does or only spouse/partner does. We include this variable on hunting in order to isolate the independent effect of appreciative outdoor recreation, separate from consumptive activities, since these likely have different associations with climate change concern (as discussed above).

In addition, we control for a number of other factors that have been identified as important in the literature on climate change concern [6]. We include three indicators to measures one’s political orientation, since this is the strongest and most consistent correlate of concern for climate change [6]. First, the political ideology variable includes responses from extremely liberal (1) to extremely conservative (7). Second, the political party affiliation variable covers categories ranging from strong Democrat (1) to strong Republican (7). The third item indicates whether the respondent voted for Donald Trump or Hilary Clinton (or another candidate) in the 2016 presidential election, and it is recoded with two categories: Trump (1) and not Trump (0).

We also control for five variables having to do with one’s sociodemographic characteristics: income (measured in 26 deciles that group annual household income from the lowest to the highest), education (highest year of school completed), age (in years), sex (female = 1, male = 0), and race (White = 1). Finally, there is one item in the survey that allows us to control for exposure or vulnerability to the negative consequences of climate change. This question asks respondents to report the extent to which their neighborhood was affected over the last twelve months by extreme weather events such as severe storms, droughts, floods, heatwaves, cold snaps, etc. Responses range between not at all (1) and to a very great extent (5).

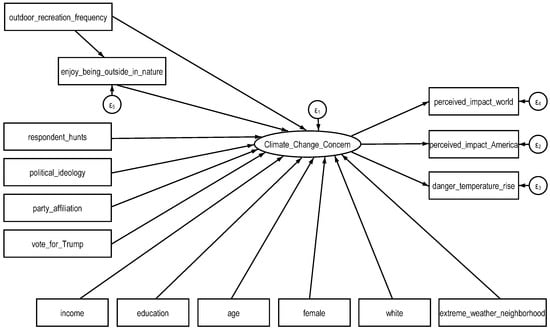

We use the structural equation modeling (SEM) technique for statistical estimation. SEM allows us to specify a conceptual model to investigate connections between latent variables and estimate both direct and indirect effects from predictors to the dependent variable. In our study, climate change concern is the dependent variable, and is a latent factor that is measured by three indicators. We specify a model in which outdoor recreation frequency, enjoyment of being in nature, and the other control variables have direct pathways to climate change concern. We also test an indirect pathway from outdoor recreation frequency to climate change concern via enjoyment of being in nature. The SEM diagram is displayed in Figure 1 [30,31]. We have weighted the data when performing SEM analysis by using the post-stratification weight with non-respondents adjusted (WTSSNRPS). The standardized SEM coefficients are presented in Table 2 and the analyses are performed by using Stata 17. We adopt the maximum likelihood approach for SEM estimation on 1401 respondents. Instead of listwise deletion, this approach makes it possible to use all the information available in the presence of missing values on one or more variables. The model fit statistics (reported in Table 2) are within acceptable ranges: the comparative fit index (0.930) is more than 0.9 and the root mean square error of approximation (0.076) is below 0.1.

Figure 1.

Structural equation modeling diagram.

Table 2.

Structural equation modeling results (standardized coefficients) predicting climate change concern (N = 1401).

3. Results

The estimates from the structural equation model, reported in Table 2, yield several interesting findings. Contradicting our primary hypothesis, there is no significant (p > 0.05) direct effect of outdoor recreation frequency on climate change concern when controlling for the other variables in the model. This suggests that engaging in nature-based leisure activities more frequently is, on its own, not predictive of a person’s concern for climate change, when controlling for these other factors. However, the indirect effect of outdoor recreation frequency on climate change concern via enjoyment of nature is positive and significant (p < 0.05), which supports our secondary hypothesis. What this indicates is that individuals who more frequently participate in nature-based leisure activities are more concerned about climate change but only if they also enjoy being outside in nature to a greater extent. Additionally, whether or not one goes hunting has no significant direct effect on concern for climate change. This finding suggests that individuals’ level of concern for climate change is not influenced by whether or not they hunt, when taking into account the variables that are controlled for in this model.

Turning to the control variables, we find, consistent with the literature, that political ideology, party affiliation, and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election are all significant predictors of climate change concern [6]. Respondents who are more conservative, identify more strongly as a Republican, and voted for Donald Trump in 2016 reported significantly lower concern. Among the sociodemographic controls, education is positively and significantly associated with climate change concern while the effects of the other four variables (income, age, sex, and race) are non-significant. This is consistent with prior research indicating the declining significance of these sociodemographic characteristics as predictors of climate change concern in the United States [32]. Finally, respondents who reported that their neighborhood was affected by extreme weather events to a greater extent reported higher levels of concern for climate change, which is consistent with previous studies of how greater exposure or vulnerability to climate change increases concern for the issue [33,34].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In this study of nationally representative data for the United States, we found that individuals who more frequently engage in appreciative outdoor recreation activities (e.g., hiking, camping, birdwatching) are more concerned about climate change but only if they enjoy being outside in nature to a greater extent. This is consistent with prior research suggesting that it is not about how much time is spent in nature, but how it is experienced and the motivation behind it; the emotional aspect of the nature experience is critical when it comes to the development of pro-environmental attitudes [21,22,23,24,25,35]. Here is an example to illustrate this finding: a person who frequently goes rock climbing but is motivated by and focused on improving their skills and fitness would likely not become as concerned about climate change as a frequent rock climber who is motivated by and focused on exploring nature and enjoying the scenic beauty. Our findings are important because they may indicate the usefulness of promoting meaningful and enjoyable nature-based leisure activities as a means of generating greater public recognition of the threat of climate change and support for climate policies to address this global problem. While scholars and others have suggested that increased time spent in nature and connectedness to nature could prompt stronger efforts to address climate change, no previous study has empirically tested the association between outdoor recreation and concern for climate change [2,3,9,35].

Much previous research on the individual-level predictors focuses on characteristics that are not malleable and thus do not point to any feasible means of encouraging attitudes and perceptions favorable to addressing climate change as an urgent problem [36]. In contrast, the findings of the present study suggest at least one potential fruitful path for fostering greater concern for climate change (and perhaps pro-climate behaviors, although we did not test this). Increasing the frequency of meaningful, enjoyable nature-based recreation activities is, at least in theory, more attainable than trying to change one’s political opinions, for example. However, one complicating factor is that there are clearly barriers and constraints to outdoor recreation that reduce opportunities to engage in these activities for marginalized and vulnerable groups [37].

The present study does have some limitations. The methodological design is neither experimental nor longitudinal and thus the results establish an empirical association rather than causal relationship; it is also possible that the causal direction is opposite of what we have hypothesized [17]. Furthermore, while a great strength of our analysis is that we use a nationally representative survey and thus have strong generalizability, we are also limited by the available questions on outdoor recreation in the General Social Survey. Additionally, it is important to note that our study is geographically limited and should be understood only in terms of the context of the United States. Future research can build on our work and previous studies by exploring the applicability of our findings to other social, cultural, and environmental contexts, especially in less-developed countries, further examining different types of outdoor recreation and ways of experiencing nature, analyzing additional aspects of connectedness to nature, considering the sociodemographic factors that shape access to and experiences of nature-based recreation and leisure activities, and employing research designs that could better establish causality.

In conclusion, individuals who more frequently engage in appreciative outdoor recreation activities tend to report a greater sense of enjoyment of being outside in nature, and this enjoyment of being in nature is associated with a higher level of concern for climate change. Future research is needed to better understand this connection and to determine if or how it could serve as a basis to foster stronger concern regarding climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.W.K.; methodology, K.W.K. and F.H.; formal analysis, F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, K.W.K. and F.H.; writing—review and editing, K.W.K.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The 2021 General Social Survey Cross-Section dataset used in this study is publicly available at: https://gss.norc.org/Get-The-Data (accessed on 30 December 2021).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Taff, B.D.; Rice, W.L.; Lawhon, B.; Newman, P. Who started, stopped, and continued participating in outdoor recreation during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States? Results from a national panel study. Land 2021, 10, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.; Olsson, M.R.; Vitestam, M. COVID-19 and outdoor recreation management: Increased participation, connection to nature, and a look to climate adaptation. J. Outdoor Rec. Tour. 2021, 36, 100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantz, C.M.; Mayer, F.S. The emergency of climate change: Why are we failing to take action? Anal. Soc. Issues Public Pol. 2009, 9, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Liu, X.; Michaels, J.L. Social capital, carbon dependency, and public response to climate change in 22 European countries. Env. Sci. Policy 2020, 114, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W.; Givens, J.E. Gender and climate change views in context: A cross-national multilevel analysis. Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M.; Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Shwom, R.L.; Brechin, S.R.; Allen, S. Ideology, capitalism, and climate: Explaining public views about climate change in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 21, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, W.; Hao, F. Approval of political leaders can slant evaluation of political issues: Evidence from public concern for climate change in the USA. Clim. Chan. 2020, 158, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berns, G.N.; Simpson, S. Outdoor recreation participation and environmental concern: A research summary. J. Exper. Ed. 2009, 32, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- DeVille, N.V.; Tomasso, L.P.; Stoddard, O.P.; Wilt, G.E.; Horton, T.H.; Wolf, K.H.; Brymer, E.; Kah, P.H., Jr.; James, P. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Heffernan, R.B. Outdoor recreation and environmental concern: An empirical examination. Rur. Soc. 1975, 40, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Geisler, C.C.; Martinson, O.B.; Wilkening, E.A. Outdoor recreation and environmental concern: A restudy. Rur. Soc. 1977, 42, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Pinhey, T.K.; Grimes, M.D. Outdoor recreation and environmental concern: A reexamination of the Dunlap-Heffernan thesis. Leis. Sci. 1979, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liere, K.D.; Noe, F.P. Outdoor recreation and environmental attitudes: Further examination of the Dunlap-Heffernan thesis. Rur. Soc. 1981, 46, 505–513. [Google Scholar]

- Theodori, G.L.; Luloff, A.E.; Willits, F.K. The association of outdoor recreation and environmental concern: Reexamining the Dunlap-Heffernan thesis. Rur. Soc. 1998, 63, 94–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L. Outdoor recreation participation and attitudes to the environment. Leis. Studs. 1986, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teisl, M.F.; O’Brien, K. Who cares and who acts? Outdoor recreationists exhibit different levels of environmental concern and behavior. Envir. Behav. 2003, 35, 506–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, C.D.; Collado, S. Experiences in nature and environmental attitudes and behaviors: Setting the ground for future research. Front. Psych. 2019, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Richardson, M.; Passmore, H.A.; Barbett, L.; Lumber, R.; Thomas, R.; Hunt, A. The green care code: How nature connectedness and simple activities help explain pro-nature conservation behaviours. People Nat. 2020, 2, 821–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junot, A.; Paquet, Y.; Martin-Krumm, C. Passion for outdoor activities and environmental behaviors: A look at emotions related to passionate activities. J. Env. Psych. 2017, 53, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumber, R.; Richardson, M.; Sheffield, D. Beyond knowing nature: Contact, emotion, compassion, meaning, and beauty are pathways to nature connection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, R.; Bright, A. Non-consumptive outdoor recreation, activity meaning, and environmental concern. In Proceedings of the 2003 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium; Murdy, J., Ed.; US Department of Agriculture Forest Service: Newtown Square, PA, USA, 2004; pp. 262–269. [Google Scholar]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. J. Env. Psych. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional affinity toward nature as a motivational basis to protect nature. Envir. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, R.R.Y.; Fielding, K.S.; Nghiem, L.T.P.; Chang, C.C.; Carrasco, L.R.; Fuller, R.A. Connection to nature is predicted by family values, social norms and personal experiences of nature. Glob. Ecol. Cons. 2021, 28, e01632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Tabanico, J. Self, identity, and the natural environment: Exploring implicit connections with nature. J. App. Soc. Psych. 2007, 37, 1219–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, E.L. Outdoor recreation participation and views on resource development and preservation. Leis. Sci. 1987, 9, 235–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.; McCullough, B.P.; Hohensee, S. Physical activity and climate change attitudes. Clim. Chan. 2020, 159, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davern, M.; Bautista, R.; Freese, J.; Morgan, S.L.; Smith, T.W. General Social Survey 2021 Cross-Section; Machine-Readable Data file and Codebook; NORC at the University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kellstedt, P.M.; Zahran, S.; Vedlitz, A. Personal efficacy, the information environment, and attitudes toward global warming and climate change in the United States. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2008, 28, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acock, A.C. Discovering Structural Equation Modeling Using Stata; Stata Press: College Station, TX, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, K.A. Structural Equations with Latent Variables; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Driscoll, D. Assessing sociodemographic predictors of climate change concern, 1994–2016. Soc. Sci. Quart. 2019, 100, 1699–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, K.W. Public awareness and perception of climate change: A quantitative cross-national study. Env. Soc. 2016, 2, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahran, S.; Brody, S.D.; Grover, H.; Vedlitz, A. Climate change vulnerability and policy support. Soc. Nat. Res. 2006, 19, 771–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Dobson, J.; Abson, D.J.; Lumber, R.; Hunt, A.; Young, R.; Moorhouse, B. Applying the pathways to nature connectedness at a societal scale: A leverage points perspective. Ecosyst. Peop. 2020, 16, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, A.C.; Hodges, H.; Oliver, S.; Smith, E.R. Confidence in local, national, and international scientists on climate change. Sustainability 2021, 13, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, R.; Green, G.T.; Poudyal, N.C.; Cordell, H.K. An analysis of perceived constraints to outdoor recreation. J. Park. Rec. Admin. 2014, 32, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).