Abstract

Anti-jamming in cognitive radio networks (CRN) is mainly accomplished using machine learning techniques in the domains of frequency, coding, power and rate. Jamming is a major threat to CRN because it can cause severe performance damage such as network isolation, network application interruption and even physical damage to infrastructure simple radio devices. With the improvement in communication technologies, the capabilities of adversaries are also increased. The intelligent jammer knows the rate at which users transmit data, which is based on the attractiveness factor of each user. The higher the data rate for a secondary user, the more attractive it is to the rate-aware jammer. In this paper, we present a dummy user in the network as a honeypot of the jammer to get the jammer’s attention. A new anti-jamming deceiving theoretical method based on rate modifications is introduced to increase the bandwidth efficiency of the entire cognitive radio-based communication system. We employ a defensive anti-jamming deception mechanism of the Pseudo Secondary User (PSU) to as an entice to trap the attacker by providing thus enhanced protection for the rest of the network from the impact of the attacker. Our analytical simulation results show a significant improvement in performance using the proposed solution. The utility of the proposed intelligent anti-jamming algorithm lies in its applications to support the secondary wireless sensor nodes.

1. Introduction

Cognitive Radio (CR) is a promising technology for dealing with the scarcity of the electromagnetic spectrum, a natural resource. Conventional wireless radio communication operates on fixed frequency slots, causing the spectrum to become crowded in certain parts of the electromagnetic spectrum while not being utilized elsewhere. CR is aware of the surrounding radio frequency (RF) environment. It learns, reasons, decides and adapts to external conditions with the goal of efficiently using the spectrum and making reliable and uninterrupted wireless communication.

CR would give opportunistic access to spectrum gaps, allowing machine learning techniques to address intermittent use of the spectrum. To prevent jamming, the CR’s flexibility may provide intelligence in spectrum detection and spectrum decisions [1]. On the other hand, the enemy can proactively use the same attributes to cause more damage to the cognitive radio network (CRN)-based communication system [2,3].

As a result, ensuring network security is critical to the successful deployment of a CRN. Attacks on cognitive radio networks include primary user emulation (PUEA), denial of service, jamming, common control channel security, spectrum sensing data falsification attack (SSDFA), and collaborative jamming [4].

Jamming is an hostile attack in a CRN, in which jammers, by emitting high-power noise, impede wireless transmission causing narrow-band interference on one sub-channel at a time near the transmitting and receiving nodes. Highly intensive jamming noise may result in either complete Denial of Service (DoS) in the channel or a significant drop in Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) that does not allow the SUs to communicate successfully. In traditional wireless communication systems, frequency hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) and direct sequence spread spectrum (DSSS) are commonly used to prevent the jammers from accomplishing their attacks. Because of dynamic spectrum hopping, these techniques can not be directly applied in cognitive radio technology to combat adverse jammers preventing successful communication.

The modulation schemes are flexible to changing states in the sense that the rate adaptation (RA) schemes of desirable interest usually adjust the physical layer transmission rate according to the channel conditions. Such schemes can be made to optimally choose a high data rate by adopting more robust modulation and coding scheme (MCS) for good SNR channels and lower transmission rates for poor channel conditions [5,6]. Transmitting in a higher data rate modulation scheme will increase the potential for jamming, affecting adversely the performance of communication due to the presence of rate-aware jammers in the network. On the other hand, transmission at low rates increases the robustness and reliability against jamming but reduces system throughput. Therefore, a suitable data rate is required for effective transmission while avoiding the jammer [7,8]. The existing naive jammer mostly rely on high power and frequent transmission of jamming signals which is impractical for power constraint jammer. Moreover this kind of high power and frequent transmission jammers also make jamming easy to be detected.

We consider a more powerful intelligent jammer which targets users based on the attraction factor of each user. The attraction factor is proportional to the rate at which the communication is made. Hence targeting the highest-impact communications in cognitive radio networks [8].

Here are the other reasons to consider rate-aware smart jammers by the introduction of an element of intelligence. First, it is easier for an intelligent rate-aware jammer to target a few symbols of higher data rates resulting in highly efficient selective jamming. Second, an effective targeted attack will force the secondary user to communicate at a lower rate by jamming all communication at higher rates as described in [8]. Finally, the lower data rates will saturate the network resulting in a higher collision probability [8].

The game is a mathematical model for an interactive situation in which participants must make strategic decisions based on payoffs. It has the potential to offer an optimal solution under dynamically changing conditions in the form of Nash Equilibrium (NE) as a competitor for an ideal security solution mechanism that does not place a significant pressure on resource restricted nodes in CRNs.

The game theory-based models are to make a logical way to depict hostile and defensive interactions between players. With the Nash equilibrium concept, both the defenders and the attackers seek optimal tactics, and neither has the incentive to deviate from their equilibrium strategies despite their conflict with security objectives [9].

Game theory is widely used in wireless communications to solve many communication problems such as resource allocation [10], packet relaying [1], anti-jamming communication [2,3,11,12]. Very recently, Zhu et al. in [13] has presented state of the art survey on game’s theoretic defensive deception.

2. Related Work

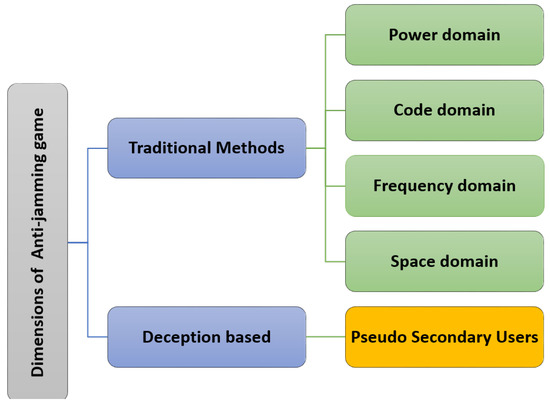

In recent years, game theory has been extensively used to model the dynamic interaction between legitimate users and the jammers. The dimensions of anti-jamming games are power domain [14], code domain [15], frequency domain [16,17], space domain [18] as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Dimensions of anti-jamming game.

Game theoretic analysis has been done extensively to study anti-jamming power control (PC) communication [14,19,20]. The authors in [14] study PC games for multi-user communication to combat jamming.

Stackelberg’s relay selection is used in [19] for physical layer security in cognitive radio networks. The Stackelberg Single-player Follower Game (OLOFS) is designed to achieve optimal pricing strategy and energy allocation in the presence of two eavesdroppers. The primary source and the selected relay operate simultaneously to achieve a Nash Equilibrium (NE). For the class of two person zero sum games, the Stackelberg equilibrium (SE) is also a NE.

Ibrahim et al. in [17] presented Frequency Hopping (FH) solution-based on anti-jamming game theory-based Q-learning. They considered an intelligent jammer in the communication system, which we classify as first level jammer in Section 3.3. Anwar et al. in [19] present an adaptive approach to defend jamming attacks in cognitive radio networks by controlling the transmission powers of nodes. The network topology is updated adaptively to cancel out the effects of the jammer. The trade-off between jamming immunity and network coverage is seen as an optimization problem that is solved through efficient game decomposition which can be expanded to solve a larger and more practical problem.

There is a continuous version of the game is combining N sub games, one for each access point, via a linear programming (LP) solution to get a unique pure strategy from the Nash Equilibrium. A summary of the literature is tabulated in Table 1. Moreover, the different types of the jammers mentioned in the literature are random jammer, continuous jamming, reactive jamming, sweep jamming and intelligent jamming [21]. This study focuses on combating against intelligent jammer.

Table 1.

Summary of literature in terms of types of anti-jamming games, jammer type, algorithm used, their defense techniques and equilibrium solutions.

2.1. Deception Based Defence Strategies

Ahmed et al. in [11] employed Stackelberg game based deception strategy against the CRN’s deceptive jammer. The authors used the jammers to detect the deceiving jammers and used the jammers’ direction of arrival to put the jammer orientation into antenna zeros. However, the proposed deception strategy has a marked difference in that it detects not only the intruder only, but also to deceive the jammer.

The authors in [33] introduced deceptive attack and defense game in networks that support the attractions of the Internet of Things (IoT). The authors analysed the deceptive attack and defence mechanism using game theory as a dynamic Baysian game for single-shot and repeative games.

More recently, Nan et al. [34] introduced a ground-breaking Stackelberg deception game based on power allocation. They considered two pairs of a transmitter-receiver. The objective of the defender transmitter receiver pair is to maximize the throughput of the legitimate transmitter-receiver pair by deceiving the jammer with another transmitter-receiver pairs.

The jammer divides its limited power budget into two communication channels, thus reducing the power injected to the legitimate tranceiver pair that transmits the real information. They also provided the Sub-game Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE) of the deception game.

The authors in [18] presented a defensive game against reactive jamming attacks in the communication channel. The tranceiver node adjust its power levels with transmission scheduling (TS) scheme, and thus intentionally modifies the real-time information resulting in asymmetric uncertainty to deceive the opponent.

Similarly, Hoang et al. [35] presented a deception strategy against a reactive jammer using Energy Harvesting (EH) and Back Scatter (BS) techniques. Bhunia et al. in [36] presented a queuing theory based on honeypot deception to deceive intelligent jammer. However, the physical nature of communication networks, on the other hand, places constraints on queuing models, pushing them to their useful limits.

2.2. Major Contribution

Deception in cyber security in wireless communication is largely adapted for the following three reasons. (1) To detect the attacker, (2) to obtain information about the intelligence of the attacker, (3) to confuse the adversarial side in making to waste its resources on sweetening. Since detection is not the focus of this article and we assume that the intelligence of the jammer is a posteriori knowledge of the user. Therefore, the main objective of our work is to confuse the attacker between legitimate target and and deceptive sweetener by using the cognitive radio network deception strategy. Furthermore, our proposed work differs from [11] in that we use deception strategy not to detect the intruder, but to deceive the rate-aware intelligent jammer. In contrast to what is suggested by the authors in [36], which proposed a queuing-based deception mechanism in CRN, we suggest a novel physical layer-based deception technique with the freedom to adapt the rate to the target parameter in CRN. The novelty of proposed approach is evident from the comparison as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of the literature as an evidence of novelty presented in this paper.

This paper has focused on combating smart rate-aware intelligent jamming attacks by modulating the transmission rate in cognitive radio networks. In our previous work we considered an intelligent reactive jammer, which we named as infant jammer in Section 3.3. We have extended the work in [16] by considering more intelligent jammer, which we call baby jammers in Section 3.3. The main contribution is enumerated as:

- We consider the cognitive adversarial rate aware jammer as an intelligent attacker who is aware of the communication parameter of the transmission rate that can adopt the dynamics of the sub-channels and SU strategies.

- In line with the [17], we have used the utility function, where the channel conditions may change from one sub-channel to another with near practical channel conditions.

- We have proposed the mathematical model of a novel deception-strategic pseudo secondary user (PSU) by introducing an attraction factor of each user based on the actual transmission rate to deceive intelligent rate aware jammer.

- The simulation results show an improvement in the performance and overall bandwidth efficiency of the cognitive radio network.

The rest of the paper is organised as a typical article structure. The system and attacker models are explained in Section 3. Section 4 presents the game formulation against an intelligent jammer and describes the proposed solution mechanism for the selection of optimal strategies, while Section 5 describes the evaluation and results. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

3. System and Adversary Model

The system model is related to modelling system, channel, Jammer, and cognitive Base Station model consisting of Secondary user and PSU models.

3.1. System Model

For CRN, the interweave paradigm is adopted, with SU accessing the spectrum only if it is not in use by the primary users (PU). After finding a white space, each user searches the available sub-channels and starts its transmission. We assume the network contains PUs, secondary users (SU), and jammers. The channel’s total used bandwidth is , and the whole bandwidth is split into independent sub-channels of equal bandwidth . However, the channel capacity of each sub-channel may differ, depending on the SNR of the received signal strength.

The jamming attack is assumed to be the only source of channel degradation in in the network and we ignore any other source of interference including the effects of multi-path fading, etc.

3.2. Channel Model

The idle state and the busy state are the two possible states for each sub-channel. If there is no PU currently using the sub-channel, it is considered idle. Any sub-channel that is in the idle state is available to the SU and the jammer. If the PU is using the channel, it is considered busy. Sub-channels occupied by SU or jammer are not allowed to be used. Prior to the sensing process, the channel states (idle or occupied) are unknown.

- IDLE STATE: If no PU is using the sub-channel, it is considered idle. This area is open to both the SU and the jammer. The idle channel’s state is indicated by .

- BUSY STATE: If any PU is using the sub-channel, it is deemed busy. Both the SU and the jammer are prohibited from transmitting on occupied sub-channels. The busy state of the sub-channel is represented by .

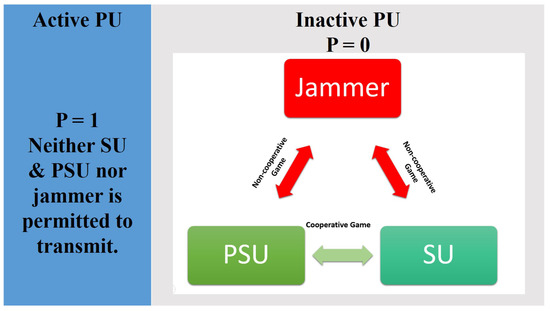

A triangular anti-jamming deception game is presented between SU, PSU and the jammer in the absence of PU as shown in Figure 2, indicating a cooperation in the form of light green arrow between all SUs and the PSUs.

Figure 2.

A triangular anti-jamming deception game is presented between SU, PSU and the jammer in the absence of PU.

We considered sub-channels where the quality of each sub-channel is different from the other sub-channels. Based on the received signal to noise ratio (SNR), each sub-channel has an upper capacity limit, which is given by,

where stands for the capacity of the SU at sub-channel against the jammer decision of , is the identical bandwidth in Hz for all sub-channel and is the received SNR of the SU at sub-channel. Let us first consider the case when there is no jammer in the system, and the communication link between SU and CBS is an Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) sub-channel with fixed noise variance, then the SNR is defined as

where is the signal power received by SU at sub-channel and is the noise power spectral density (PSD) of Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN). The higher the , the more will be the sub-channel capacity , and higher will be the sub-channel quality. The sub-channel capacity of SU at sub-channel becomes,

Moreover, the communication link deteriorates due to the additive jammer, which transmits strong radio signals to degrade the sub-channel’s capacity. Therefore, the SNR in the presence of jammer is given by:

where and are the Power Spectral Density (PSD) and bandwidth of the jammed sub-channel respectively. Since all sub-channels have identical bandwidths of , so the SNR in the presence of jammer becomes,

We get (4) only when . The goal of SU is to carefully transition to the available high-capacity sub-channel in order to optimize spectral efficiency by avoiding possible jamming.

3.3. Jammer Model

Objective of the jammer: The Jammer attempts to reduce the average CBS bandwidth efficiency by injecting noise for users with a high-impact connection. The effect of a jamming attack on the communication sub-channel is to minimise the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of the receiver and thus reduce the channel capacity as a result. We assume a powerful jammer with the following characteristics.

- Level I: Reactive jammer

- Level II: Intelligent jammer with Rate-aware compliance features

The basic assumptions about the jammer model are:

- It is assumed that the jammer is at the physical layer, where the jammer hinders the radio communication by producing high-power noise in the target sub-channel.

- Similar to other secondary users, an intelligent jammer is in essence a secondary user with sensing, perception, and adaptive capabilities as assumed by [12,16,32]. As we already know that the secondary user has the lower priorities to access the spectrum as compared to the primary users, therefore a secondary user has to use its sensing ability to sense its environment for the availability of free spectrum to continue its transmission and to avoid interference to the primary user. In a very similar fashion, a jammer needs to sense its RF environment for the presence of a primary user. Then the jammer will avoid the primary user if detected as the primary user due to the risk of a high penalty. On the other hand, the jammer targets users other than primary users.We are combating against intelligent jammer in CRN in interview paradigm, where the spectrum hole is accessed by secondary user on opportunistic spectrum access (OSA) bases. The intelligent jammer has the cognitive capabilities, means that it is capable of sensing the presence of primary user in the network. The intelligent jammer is deemed as a secondary users with negative intentions to disrupt the communication of other secondary users. In the initial sensing time of a time slotted system, intelligent jammer do also listen to the presence/absence of primary user just as the other secondary users do. So, the intelligent jammer is capable of sensing the RF environment and based on the sensing results it transmit the noise signals on the frequencies vacated by a primary user and utilized by secondary user to jam the communication of secondary users. The jammer can not jam the primary user due to heavy penalty imposed by the law-enforcement agencies.

- Due to the possibility of severe penalty, the jammer does not target the PU communication [2,36]. The jammer monitors the RF environment for a predetermined period of time before transmitting its jamming signals according to the sub-channel conditions and the SU’s strategy. If a PU is identified in one of the sub-channels, the jammer will switch to another sub-channel and starts detecting another SU.

- Jammer uses attraction factor , , to target HIC, which is defined aswhere is the data rate based on the modulation schemes adapted by the SU/PSUs. The intelligent jammer may acquire the rate/code/modulation information of SU/PSU either using explicit rate information or modulation and code guessing [6]. Moreover, the rate information of a transmission is vulnerable in many communication protocols. In IEEE 802.11 networks, for example, the rate is specified explicitly in the SIGNAL field of the physical layer’s frames. An intruder can easily coordinate with two parties’ communication, evaluate data frames, and derive the rate. As demonstrated in [8], this attack is quite practical. The adversary can evaluate the received signal in complicated I/Q form even if the rate information is not explicitly supplied inside the packet header. The attacker can trace the received constellation pattern and determine the modulation in use after performing carrier synchronization, frequency, and phase offset correction. The frame structure of the protocol is not required for this method. The guessing strategy on USRP can be shown by creating a modulation detector that can identify the modulation of a transmission in real time. It may readily be modified to create a practical rate-aware jammer that jams high-rate packets selectively. An attacker could employ more sophisticated techniques to determine not only the modulation of the message, but also the codes used. One such method is to follow the sequence of received symbols in order to predict the codes based on the fact that various codes cause distinct transitions from one coded symbol to the next. For the attacker, guessing through matching and trial-and-error is efficient since most communication protocols specify a finite variety of modulations and codes [6].

- Jammer calculates for each detected signal in its environment according to (5), and target the SU with the highest attraction factor.

We consider a jammer with multiple intelligence levels.

- Level-I intelligence/Reactive/Infant jammer is an intelligent jammer with cognitive skills is expected to choose the optimal approach in response to the dynamics of sub-channels and SU strategies. It scans its own RF environment and only sends jamming signals if it finds a SU, hence saving its power.

- Level-II Intelligence/Smart/Baby jammer Intelligent jammer targets the highest impact communication (HIC) sub-channels by targeting specific transmission characteristics of the SU, For example, it can target the highest transmission rate , which may be the case in multimedia communications, highest transmission power , the sub-channel with highest bandwidth , packet inter arrival time, and frequency shift etc. [36]. Highest impact communication is quantitatively measured by jammer using attraction factors in (5). We assume the jammer perceives highest impact communication as the communication with highest transmission rate , which is the case for multimedia communications.

With the level-I intelligence, the jammer scans the environment and learns the characteristics of the sub-channel and SUs. While using the level-II intelligence, the jammer determines the highest impact communication of the secondary network using attraction factor in (5).

3.4. Cognitive Base Station (CBS)

The secondary network consists of one central unit called fusion center (FC)/Cognitive Base Station (CBS), several SUs and a PSU.

Objective of CBS: The goal of CBS is to improve overall system’s average throughput through the successful deployment of a deception mechanism using a PSU in the presence of intelligent jammer.

3.4.1. Secondary User Model

- The SUs are forced through Dynamic Spectrum Access (DSA) implemented in CBS to periodically stop its transmission and to sense PU’s activity, to protect the incumbent PU services.

- During the sensing time, the SU senses its environment before starting to transmit any data. Throughout the sensing time, each SU would try to detect the the presence of any PU in the accessible sub-channels. On the other hand, the SU will not be able to determine the existence of an adversary at the beginning of the time slot. Regarding the detection of jamming, the interested readers may see for more details reference [38]. At the end of each time period, the SU will know if its connection was successful or it was jammed by a malicious jammer.

- The SU will receive a positive payoff if the transmission is successful, while a jammed transmission on the other hand, would result in a negative payoff. The utility of the SU denoted as in the sub-channel can be derived as:where and are defined in Equations (3) and (5), respectively. While and are the gain of secondary user and gain of the jammer, respectively. Combining (3) with (6) yields (7).

In other words, the SU utility function as detailed in (7) allows us to incorporate the condition of a practical sub-channel in terms of sub-channel capacity and jamming situations. In the presence of a jammer, the SU’s objective is expected to achieve the sum of the discounted payoff by selecting a good quality sub-channel.

3.4.2. Pseudo Secondary User (PSU) Model

The so-called pseudo secondary user (PSU) is assumed to mimic the legitimate SU characteristics of the jammer’s attraction. The PSU entices the jammer by sending in a higher higher data rate to invite the jammer to attack the PSU. A group of SUs take on the services of a PSU to trick the smart jammer, acting like a honeycomb for jamming.

- The PSU does not send a legitimate signals instead it transmit a garbage data at a greater rate than the other SUs to deceive the jammer. That is why the utility of PSU is not counted in the calculations of CBS throughput.

- The wireless communication system is designed to achieve a defined BER line in an BER-SNR (dB) curve. One has to follow this line for a reliable communication. Moreover, according to the Shannon capacity theorem a certain data rate can tolerate a certain level of jamming power (received SNR) to achieve a reliable communication. If the jamming power is greater than the threshold, the corresponding data transfer rate may exceed the capacity of the sub-channel. The packets are lost resulting in lower system throughput. However, this does not apply to the proposed PSU based deception mechanism, in which the PSU transmits garbage values with a rate higher than the rate of SUs in the vicinity. Since the PSU transmits garbage data, it does not care about packets losses. Hence, the data rate/capacity of PSU is not accounted for in the system throughput.

- A variable called attraction factor is introduced to attract the jammer by attracting the rate-aware jammer towards itself. Our proposed scheme is implemented in such a way that the jammer gets an impression of PSU as the highest impact communication. It plays the role of the Achilles heel in a jammer.

- Since we are focusing on rate adaptation based anti-jamming solution against an intelligent jammer, we assume perfect time and frequency synchronization between all SUs and PSUs.

4. Game Formulation

In this section, a game theoretic problem formulation is presented after giving a brief overview of game theory.

4.1. Preliminaries

Game theory can be described as the science of strategy, in which competing independent players make the optimal decision in strategic situations. Players, strategies, payoffs, information, rationality and Nash Equilibrium (NE) are the key elements of the game theory, which are defined below.

Players are two interacting parties, which in our case are SU and jammer players.

Strategies are rules or plan of action of each player to play the game.

Payoffs/Utility are actually gained by the players after adopting certain strategies, and the optimal strategy is the one that increases the player’s earnings.

Information relates to what the players are supposed to know. Complete information is one in which each player knows every aspect of the game while in perfect information, the player also knows the previous actions of all the other players.

Rationality refers to when the players are assumed to be rational to take best alternative in the set of possible choices. It helps narrow down the range of possible decisions.

Nash Equilibrium (NE) is an action vector from which no player can profitably unilaterally deviate.

Definition 1.

If the following two inequalities are fulfilled, a set of strategies {i for row player, and j for column player} result in a non-cooperative Nash equilibrium solution to a bimatrix game (), where and are reward matrices for each player, for all and states.

Furthermore, the pair () is regarded as the bimatrix game’s non-cooperative Nash equilibrium outcome. Where represents the payoff matrix for Player I and is payoff matrix for Player II. The payoff matrix of standard matrix game represent the objective of each player.

4.2. Utility Functions with and without PSU

Utility without PSU: The utility function of SU network can be written as the overall gain of the secondary network, which is being controlled by Cognitive Base Station (CBS) having a number of SUs in the network, and is determined by

where and which satisfy the requirements given in Equation (9)

Utility with PSU: The utility function of secondary network in the presence of PSU can be written as the overall gain of the secondary network, which is being controlled by Cognitive Base Station (CBS) having a few SUs and a PSU, and is determined by . Since the PSU does not take part in the useful communication, so the utility of PSU is not counted for the calculations of throughput. Therefore, the ultimate utility of CBS is as given by Equation (10)

where and satisfies,

where is the attraction factor for user in the presence of PSU in the network and is the data rate of deceptive PSU transmission. The attraction factor of a PSU is kept slightly higher than all other legitimate SUs in the network. i.e., , so that the jammer is more attracted towards PSU as compared to legitimate SU. In general, the probability of the attacker to fall in the trap of PSU is given by .

The objective of the secondary network is to maximize the network utility by successfully deploying PSU to deceive the jammer while increasing the throughput of the system. We get throughput of the system by adding the throughput of every individual successful user i.e.,

The problem can be formulated as an optimization problem. The optimal strategy of the CBS is the maximizer of the following problem

subject to

5. Simulations and Results

The simulation results are shown in bandwidth efficiency. The bandwidth efficiency can be calculated in bits per second per Hertz (bps/Hz) as follows:

We compare our results with and without the PSU in the network i.e., the comparison is made for N SUs against the SUs plus 1 PSU. For simplicity, the sub-channel conditions are considered in ascending order i.e., . Alternatively, it means that the sub-channel is the best sub-channel among all.

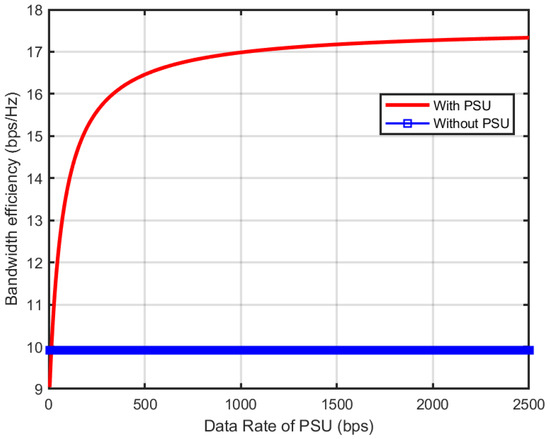

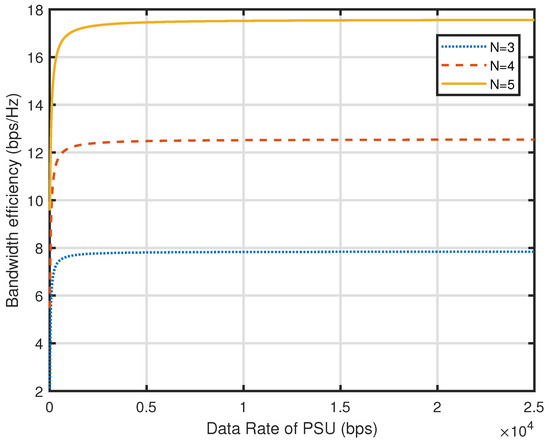

Figure 3 depicts the impact of increasing data rate of the PSU against a rate-aware intelligent jammer. It is shown that increasing the data rate of a PSU results in increasing its attraction factor and becomes more attractive target for an intelligent jammer. Hence it helps in protecting the other SUs from being jammed. The successful communication of the rest of SUs increase the overall utility of the system. Specifically, it is shown that the utility almost remains constant after the data rate exceeds 1000 bps. Moreover, data rate of PSU-based system should be at least greater than 15 bps to get higher utility as compared to the system without PSU.

Figure 3.

Impact of increasing PSU data rate against a rate ware jammer.

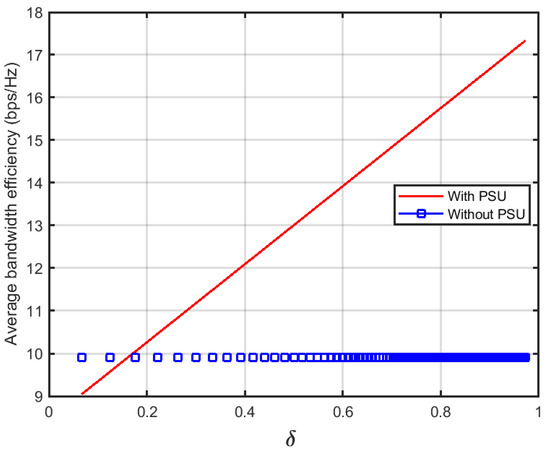

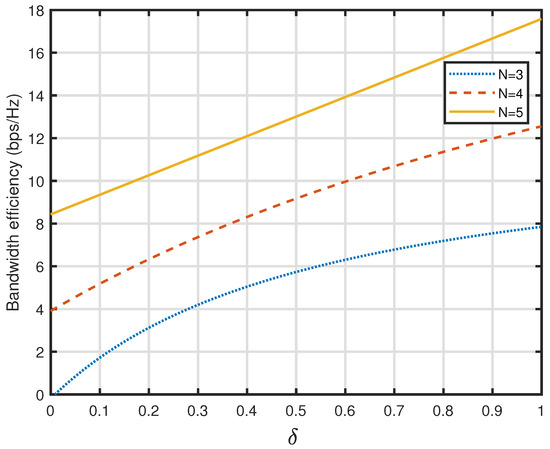

In Figure 4 the impact of increasing jamming probabilities of PSU is studied against a rate-aware intelligent jammer. It is shown that increasing the jamming probability of the PSU will secure the overall system by increasing the overall utility of the CBS. More precisely, it is evident that the jamming probability of PSU should be at least 0.18 to get the benefit of deploying PSU in the system. It should be kept in mind that the curve with PSU is considered for users. The user excluded being PSU itself, because it does not transmit legitimate signal and does not take part in overall throughput of the system as mentioned in (11). It is to be noted that the straight line of utility of the CBS without PSU (blue rectangles) is due to the fact that it is independent of PSU probabilities.

Figure 4.

Impact of increasing PSU data rate and attraction factor against a rate ware jammer.

If we assume equal resource utilization for SU/PSU, then the network with one SU and one PSU is consuming of its resources to protect the one SU. Similarly, when we have seven SUs and one PSU, the resources are wasted. It is better to use PSU for a bigger network of larger number of SUs.

In Figure 5 the curves for different values of N are shown. It has been demonstrated that when N increases, bandwidth efficiency is improved. Similarly, the curves in Figure 6 show an improvement in bandwidth efficiency as N increases from 3 to 5. The similar behaviour can be also observed for N greater than 5.

Figure 5.

Comparison of data rate of PSU in terms of average bandwidth efficiency for different values of N.

Figure 6.

Comparison of attraction factor of PSU in terms of average bandwidth efficiency for different values of N.

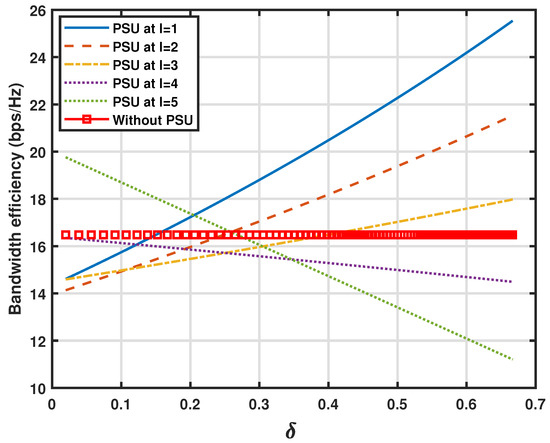

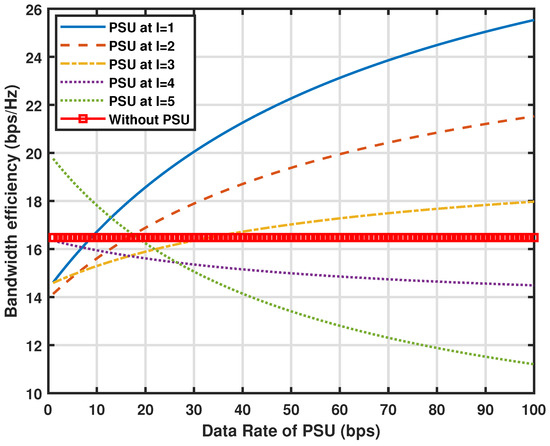

The change in the position of PSU is portrayed in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 7 shows the curves for bandwidth efficiency when the position of PSU is changed from 1 to L. For simplicity, . Keep in mind the assumption that the SNR1 of sub-channel 1 is minimum while SNRL is maximum. The overall bandwidth efficiency of the CBS is highest when PSU is deployed at the sub-channel with lowest sub-channel quality as shown by the solid line for l = 1. Furthermore, from the Figure 8 it is evident that for l = 1 the PSU is effective only after the attraction factor exceeds 0.15 probability. However from both Figure 7 and Figure 8 it is visible that when the PSU moves to the next sub-channel with higher sub-channel qualities, it may result in wasting its resources to deceive the jammer resulting in less bandwidth efficiency. For total of sub-channels, when PSU is at the bandwidth efficiency curve of PSU crosses the curve without PSU at around 0.43 probability with lowest productive bandwidth efficiency. The PSU at and , the bandwidth efficiency gets even worse, which decreases with increase in data rate.

Figure 7.

Comparison of data rate of PSU in terms of bandwidth efficiency for different locations of PSU from 1 to L.

Figure 8.

Comparison of attraction factor of PSU in terms of bandwidth efficiency for different locations of PSU from 1 to L.

5.1. Cost Analysis

The cost is paid in terms of bandwidth loss which is incurred by adopting a fake user called as a pseudo secondary user (PSU). The loss is higher when the PSU occupies a sub-channel with higher SNR values, further reducing throughput reduction as shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8 and the discussion hereafter. Since the PSU does not participate in the bandwidth efficiency of CBS, therefore, as the PSU transitions to the high-quality sub-channel, the data rate that would otherwise be utilised is wasted by adopting the PSU to deceive the jammer.

5.2. Comparison with the Previous Work

We compare our results with [17,25] to show the bandwidth efficiency of our proposed approach as listed in Table 3. Since the work presented previously have used FH and FH + RA, respectively, using reinforcement learning to maximize bandwidth efficiency of the system, therefore, for the fair analysis of the result we tabulate the result for easy comparison of the three papers.

Table 3.

Comparison of performance evaluations of our proposed scheme.

As depicted in Table 3, all other parameters are the same except for jammer type. The jammer type used in [17,25] are a reactive jammer, which commences its transmission upon the detection of SU activity in the cognitive radio enabled network. We call this type of jammer as Level I jammer in Section 3.3. In our proposed work, we consider a more challenging jammer which is not only a reactive jammer but also targets the SU based on the attraction factor of each user making, it more harmful to the highest impact communication.

Moreover, the bandwidth efficiency comparison results demonstrate that employing the deception-based anti-jamming technique proposed in our study has an advantage over the work in [17]. The bandwidth efficiency of our suggested approach is more than 3 times that of [17]. The bandwidth efficiency of our proposed approach is more than 4 times that of [25]. To be very accurate the results in [25] show bandwidth of 21 bps for 5 number of sub-channels (see Figure 7 in [25]). To get bandwidth efficiency for each sub-channel we divide 21 by 5 to get the bandwidth efficiency equal to 4.2 bps/Hz. Furthermore, all results were obtained with the help of the MATLAB simulation environment.

6. Conclusions and Future Works

In this study, we have presented a unique game-theoretic deception anti-jamming strategy to improve the overall bandwidth efficiency of a cognitive radio-based communication system. To deceive the attacker and protect the remainder of the network from hostile influences, we have used a defensive deception anti-jamming method based on rate adjustments. To lure the jammer, we have introduced a counterfeit user within the network as a trap for the attacker. The higher a secondary user’s data rate is, the more attractive it is to a rate-aware intelligent jammer.

Simulation results show that the bandwidth efficiency of the network adopting the proposed deception strategy crosses the bandwidth efficiency curve of the network without PSU at around attraction factor of 0.16. Which is consistent with our claim that the CBS with the PSU perform well even with the attraction factor of 0.20 compared to a system without deception strategy. Moreover, compared to a system that does not use the deception method, our proposed solution can increase bandwidth efficiency by up to 1.7 times. Similarly, since the PSU does not participate in the legitimate communication, allocating the PSU a highest-quality sub-channel will reduce the bandwidth efficiency hence demanding an optimal sub-channel selection for better bandwidth efficiency which is evident from the results shown.

The research presented in this paper can be extended as future work in the following three ways. Firstly, the deception strategy can be improved further if we change the role of a secondary user, keeping it dynamically adjustable. Maintaining the secondary user role constant will make the jammer conscious of the PSU, and will lead to the counter-deception strategy by the intelligent jammer. Inspired by the changing of the guard ceremony with the transition between SU and PSU will lead to more confusion for the jammer. Secondly, a dynamic assignment of PSU based on the current dynamics of the environment will lead to more complexity in the deception mechanism. Thirdly, using FH with RA for decoy mechanism used for attracting the jammer will enhance the deception further. Enabling PSUs to hop to other available sub-channels along with rate adaption will give the PSU freedom of efficient spectrum utilization while deceiving jammer. Finally, a PSU with higher attraction factor can also be used to detect the jammer and to predict the level of intelligence from guessing its fingerprints.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.I. and A.N.M.; methodology, K.I., A.N.M. and S.K.; writing-original draft preparation, K.I., A.N.M. and A.W.; writing-review and editing, K.I., A.W., A.M.A. and S.K.; project administration, A.M.A., S.A., M.I. and S.K.; supervision, A.N.M. and S.K.; funding acquisition, A.M.A., S.A., S.K. and M.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge Onaizah College of Engineering and Information Technology for funding the publication charges.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Higher Education Commission (Pakistan) and Deputy-ship for Research & Innovation, Ministry of Education (Saudi Arabia) for supporting this research work. The authors acknowledge receiving the technical support from International Islamic University Islamabad (Pakistan), and Onaizah College of Engineering and Information Technology (Saudi Arabia).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AWGN | Additive white Gaussian noise |

| BS | Back Scattering |

| CR | Cognitive Radio |

| CRN | Cognitive Radio Networks |

| DoS | Denial of Service |

| DSSS | Direct sequence spread spectrum |

| EH | Energy Harvesting |

| FH | Frequency hopping |

| FHSS | Frequency hopping spread spectrum |

| GSG | General sum game |

| HIC | Highest Impact Communication |

| HLA | Hierarchical Learning Algorithm |

| IL | Independent Learner |

| JAL | Joint Action Learner |

| MCS | Modulation and Coding Scheme |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MARL | Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning |

| MLE | Maximum Likelihood Estimation |

| NE | Nash Equilibrium |

| OLOFS | One Leader One Follower Stackelberg Game |

| PC | Power Control |

| PSD | Power Spectral Density |

| PSU | Pseudo Secondary User |

| PU | Primary User |

| PUEA | Primary User Emulation Attack |

| RA | Rate Adaptation |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| SSDFA | Spectrum Sensing Data Falsification Attack |

| SU | Secondary User |

| SG | Stochastic Game |

| SLMFS | Single Leader Multiple Follower Stochastic Game |

| SE | Stackelberg Equilibrium |

| SNR | Signal to Noise Ratio |

| TS | Transmission Scheduling |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

References

- Bastami, A.H.; Kazemi, P. Cognitive Multi-Hop Multi-Branch Relaying: Spectrum Leasing and Optimal Power Allocation. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2019, 18, 4075–4088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, Y.; Liu, K.R.; Clancy, T.C. An anti-jamming stochastic game for cognitive radio networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2011, 29, 877–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aref, M.A.; Jayaweera, S.K.; Yepez, E. Survey on cognitive anti-jamming communications. IET Commun. 2020, 14, 3110–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahdine, F.; Kaabouch, N. Security threats, detection, and countermeasures for physical layer in cognitive radio networks: A survey. Phys. Commun. 2020, 39, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, K.; Zhao, J.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Y. A practical SNR-guided rate adaptation. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2008—The 27th Conference on Computer Communications, Phoenix, Arizona, 13–18 April 2008; pp. 2083–2091. [Google Scholar]

- Vo-Huu, T.D.; Noubir, G. Mitigating rate attacks through crypto-coded modulation. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Symposium on Mobile Ad Hoc Networking and Computing, Hangzhou, China, 22–25 June 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Hanawal, M.K.; Abdel-Rahman, M.J.; Krunz, M. Game theoretic anti-jamming dynamic frequency hopping and rate adaptation in wireless systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 12th International Symposium on Modeling and Optimization in Mobile, Ad Hoc, and Wireless Networks (WiOpt), Hammamet, Tunisia, 12–16 May 2014; pp. 247–254. [Google Scholar]

- Noubir, G.; Rajaraman, R.; Sheng, B.; Thapa, B. On the robustness of IEEE 802.11 rate adaptation algorithms against smart jamming. In Proceedings of the Fourth ACM Conference on Wireless Network Security, Hamburg, Germany, 14–17 June 2011; pp. 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Rass, S. Game theory meets network security: A tutorial. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Toronto, ON, Canada, 15–19 October 2018; pp. 2163–2165. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, A.; Ahmad, S.; Rehmani, M.H.; Hassan, N.U. A Survey on Radio Resource Allocation in Cognitive Radio Sensor Networks. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2015, 17, 888–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.K.; Fapojuwo, A.O. Stackelberg Equilibria of an Anti-Jamming Game in Cooperative Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Trans. Cognit. Commun. Netw. 2018, 4, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, K.J.R.; Clancy, T.C. Anti-jamming games in multi-channel cognitive radio networks. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2012, 30, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, M.; Anwar, A.H.; Wan, Z.; Cho, J.H.; Kamhoua, C.; Singh, M.P. A survey of defensive deception: Approaches using game theory and machine learning. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2021, 23, 2460–2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Wu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Ding, G.; Jia, L. Power control games for multi-user anti-jamming 543 communications. Wirel. Netw. 2019, 25, 2365–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Hao, X.; Kong, Z.; Yan, X. Anti-Sweep-Jamming Method Based on the Averaging of Range Side Lobes for Hybrid Modulation Proximity Detectors. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 33479–33488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Ng, S.X.; Qureshi, I.M.; Malik, A.N.; Muhaidat, S. Anti-Jamming Game to Combat Intelligent Jamming for Cognitive Radio Networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 137941–137956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, K.; Qureshi, I.M.; Malik, A.N.; Ng, S.X. Bandwidth-Efficient Frequency Hopping based Anti-Jamming Game for Cognitive Radio assisted Wireless Sensor Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 93rd Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2021-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 25–28 April 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, K.; Ren, X.; Quevedo, D.E.; Dey, S.; Shi, L. Defensive deception against reactive jamming attacks in remote state estimation. Automatica 2020, 113, 108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.H.; Atia, G.; Guirguis, M. Adaptive topologies against jamming attacks in wireless networks: A game-theoretic approach. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2018, 121, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Feng, S.; Anpalagan, A. Stackelberg game approaches for anti-jamming defence in wireless networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2018, 25, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lichtman, M.; Poston, J.D.; Amuru, S.; Shahriar, C.; Clancy, T.C.; Buehrer, R.M.; Reed, J.H. A communications jamming taxonomy. IEEE Secur. Priv. 2016, 14, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Xue, G.; Zhang, J.; Richa, A.; Fang, X. Coping with a smart jammer in wireless networks: A Stackelberg game approach. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2013, 12, 4038–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namvar, N.; Saad, W.; Bahadori, N.; Kelley, B. Jamming in the internet of things: A game-theoretic perspective. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), Washington, DC, USA, 4–8 December 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, S.; Wang, J.; Yao, H.; Jiang, C.; Han, Z.; Ren, Y. Colonel blotto games in network systems: Models, strategies, and applications. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawal, M.K.; Abdel-Rahman, M.J.; Krunz, M. Joint adaptation of frequency hopping and transmission rate for anti-jamming wireless systems. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2015, 15, 2247–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, M.; Xiao, M.; Shao, J. Game theory-based anti-jamming strategies for frequency hopping wireless communications. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2018, 17, 5314–5326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnaev, A.; Petropulu, A.P.; Trappe, W.; Poor, H.V. A jamming game with rival-type uncertainty. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 5359–5372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhou, W.; Kou, B.; Wang, Y. Dynamic spectrum access with physical layer security: A game-based jamming approach. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 12052–12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Oro, S.; Galluccio, L.; Morabito, G.; Palazzo, S.; Chen, L.; Martignon, F. Defeating jamming with the power of silence: A game-theoretic analysis. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2014, 14, 2337–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altman, E.; Avrachenkov, K.; Garnaev, A. A jamming game in wireless networks with transmission cost. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Network Control and Optimization, Avignon, France, 5–7 June 2007; Springer: Avignon, France, 2007; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, L.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.; Feng, S.; Yu, L.; Anpalagan, A. A multi-domain anti-jamming defense scheme in heterogeneous wireless networks. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 40177–40188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Song, M.; Xin, C.; Backens, J. A game-theoretical anti-jamming scheme for cognitive radio networks. IEEE Netw. 2013, 27, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, Q.D.; Quek, T.Q.; Lee, J.; Jin, S.; Zhu, H. Deceptive Attack and Defense Game in Honeypot-Enabled Networks for the Internet of Things. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016, 3, 1025–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, S.; Brahma, S.; Kamhoua, C.A.; Leslie, N.O. Mitigation of Jamming Attacks via Deception. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 31st Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor and Mobile Radio Communications, London, UK, 31 August–3 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, D.N.; Alsheikh, M.A.; Gong, S.; Dutkiewicz, E.; Niyato, D.; Han, Z. “Borrowing Arrows with Thatched Boats”: The Art of Defeating Reactive Jammers in IoT Networks. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2020, 27, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhunia, S.; Sengupta, S.; Vázquez-Abad, F. Performance analysis of CR-honeynet to prevent jamming attack through stochastic modeling. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2015, 21, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firouzbakht, K.; Noubir, G.; Salehi, M. On the performance of adaptive packetized wireless communication links under jamming. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2014, 13, 3481–3495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osanaiye, O.; Alfa, A.; Hancke, G. A Statistical Approach to Detect Jamming Attacks in Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2018, 18, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).