Abstract

Households play an important role in reducing coastal vulnerability through individual and collective action. Information provision is a key strategy adopted by governments to support household adaptation. However, there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of the different types of information and their influence on coastal household response. Drawing on case study research in two Australian coastal communities, we explore the types of information shaping household responses to three hazard scenarios: a heatwave, a severe storm, and sea-level rise. We find that passive information informs action in fewer than half of all households. Furthermore, even current attempts at more action-oriented information only informs coping strategies. If coastal adaptation is to achieve the transformational changes vital to manage the impacts of climate change, information provision must transition from passive and generic delivery via traditional modes, to actively communicating adaptation as the ‘glue’ between hazard management and household resilience through context-relevant and household-driven communication modes. Further research into the types of information that promote more-than-coping responses, such as information to facilitate collective action, is also recommended.

1. Introduction

Coastal areas are at the forefront of the impacts of climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) 6th Assessment Report warns that sea levels will continue to rise for centuries as the ocean continues to warm and ice sheets melt and will remain elevated for thousands of years [1]. In addition, climate change is projected to increase the frequency and severity of rapid onset extreme events [2]. Rising sea levels coupled with extreme events increase coastal impacts such as erosion and inundation [3,4]. These impacts pose significant social, economic, and environmental threats to coastal communities worldwide and necessitate a collective and transformative response.

A collective, or shared, response to the impacts of climate change is advocated in many national adaptation strategies, e.g., [5,6]. For example, the Australian Government’s National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy adopts the principle of shared responsibility [7,8]. As part of the Australian strategy, governments, businesses, communities, and individuals are assigned the same responsibility: comprehend climate change risks and adapt accordingly. To increase communities’ climate change understandings and adaptive capacities, the strategy identified the provision of authoritative climate science and information as one of the most important government interventions [8]. So too, information provision is considered a critical role of government in enabling adaptation in Canada, Europe, and the United Kingdom [5,6,9] and has been identified as the most common adaptation policy response in Europe [10]. Providing information is anticipated to allow communities to better understand climate change, make more informed decisions about the risks they face, and act accordingly.

This approach aligns to early theories of behavioral change, including the Theory of Planned Behavior [11] and Protection Motivation Theory [12], where it is postulated that attitudes and perceptions of individuals are related to, and indeed predictive of, their behaviors. Similar approaches to climate change adaptation have been advocated elsewhere. For instance, the IPCC identified access to information as an important determinant of adaptive capacity [13] and a key principle of [14], and enabling condition for [1], effective adaption. Numerous studies have also identified information provision as a logical way to overcome knowledge deficits within communities and encourage preparatory responses to climatic stimuli [15,16,17,18,19,20].

Yet criticisms of the information deficit model as the cornerstone of adaptation planning abound. While information contributes to capacity, adaptive actions result from a broader suite of practices and processes beyond access to information or knowledge [13,21]. Barriers from physical (e.g., finance and assets) to cognitive (e.g., risk perceptions, perceptions of efficacy, and social norms) inhibit local action [22,23]. In the context of natural hazards, for example, awareness of bushfire risk does not necessarily lead to preparedness due to everyday dilemmas including costs, gender roles, and competing priorities [24]. In the context of heatwaves, information about preventive strategies has little impact on the behaviors of individuals who do not perceive themselves at risk or in need of taking preparatory actions [25].

Furthermore, little is known about the efficacy of different types of information in facilitating climate change adaptation, particularly in the coastal zone. Information can be categorized into three types: passive (hazard and preparedness education material), interactive (information derived through interactions with other people) or experiential (information gleaned from personal life experiences, direct or indirect) [26]. Considerable government intervention has focused on providing passive information to raise awareness and promote sustainable behaviors within the home. Such programs have assumed ‘that more and better science is needed to overcome public ignorance and inertia’ [27] (p. 107), and by addressing the ‘information deficit’, more sustainable behaviors will develop [28]. However, research conducted with householders has revealed that providing information and increasing public awareness of environmental issues is insufficient to change behavior in ways that are more sustainable [29,30,31].

Some researchers have examined why passive information does not promote household action and offered suggestions to improve its efficiency. Head and colleagues, for example, argue householders disregard the rules and practices promoted by government because sustainability education programs often pay ‘little attention to the ways household energy, water and other resource consumption practices are part of the rituals, rhythms, habits and routines of everyday life’ [29] (p. 355). Moser argues that adaptation communication efforts need to ‘relate to people in a way that resonates with their existing values and beliefs … tapping into deep motivations and understanding barriers to action’ [32] (p. 349). Whether this can be best achieved through passive, interactive, or experiential information has been explored, in part, by sustainability scholars [33,34], and with respect to household preparation for earthquakes in New Zealand [26]. However, whether these findings apply to coastal household adaptation is unclear.

Coastal areas are at the forefront of the impacts of climate change and householders will play an important role in responding to the impacts. Scholars seeking to inform urban coastal household adaptation continue to promote the provision of passive information as a key strategy to facilitate household action [35,36,37]. However, the degree to which passive information, as opposed to other information sources, shapes perceptions and actions is unclear. In the absence of research critiquing information use as it relates to coastal household response, a reliance on passive information continues, with limited evidence that this approach delivers the individual and collective responses required for transformative change in coastal communities.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore whether passive information informs coastal households’ responses to climate change and whether those responses reduce vulnerability to the potential impacts. The study enables a critical reflection on the dominant ‘information deficit’ approach of passive information provision and allows recommendations for future research that can broaden the policy toolkit and engage households in adapting to the impacts of climate change in coastal areas.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

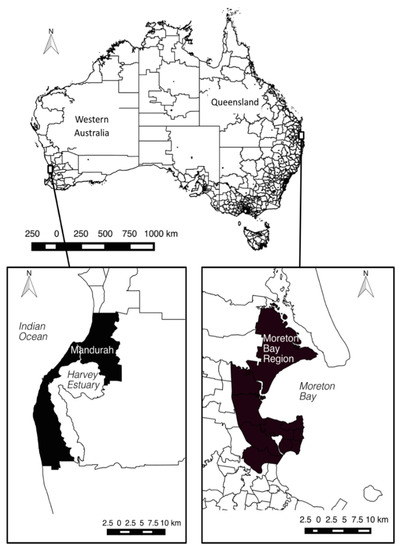

Data were collected as part of a larger research project exploring household adaptive capacity in two Australian coastal communities [38,39,40]: the City of Mandurah, Western Australia and Moreton Bay Coastal Region, Queensland (Figure 1). The case locations were purposefully selected based on a consideration of area-level demographic and socioeconomic data, settlement history, development, and environmental issues. The cases are peri-urban coastal communities, characterized by diverse sociodemographic characteristics, rapid population growth, and competing land uses. They are vulnerable to climate change risks [41,42] and considered to have ‘less [adaptive] capacity than capital city centres’ [42] (p. 7) (see [40] and Supplementary Materials for further detail on case locations). While the cases are not representative of all settlement types and communities, they provide a snapshot of information use as it relates to adaptation responses in a peri-urban coastal context. The results provide observations that can be further explored in other contexts.

Figure 1.

Case study areas (source [43]).

2.2. Data Collection

The research was implemented via a two-phase sequential mixed methods approach. In the first phase, a survey questionnaire was implemented (n = 400), designed based on a concurrent embedded mixed methods approach to identify relationships between household characteristics, perceptions, and adaptive action. In the second phase, semi-structured interviews (n = 17) explored household interpretations of climate hazards, capacity to respond, and adaptive responses [44]. Each phase is discussed briefly in turn, see [40,43] for further detail.

The survey questionnaire was delivered to households randomly selected from a complete list of residential addresses in each case study area [40]. A representative from each household completed the questionnaire on their household’s behalf (referred to as the ‘householder’). Householders were asked how effective passive information covering the following topics would be in reducing future vulnerability and aiding preparation: information related to (i) the exposure of their household to future hazards; (ii) the nature of existing hazards; and (iii) information detailing strategies to prepare. The utility of each topic of information was rated on a four-point scale (from not at all useful to very useful) with an additional option for ‘not sure’. The questionnaires also contained questions on household and respondent characteristics (e.g., homeownership, income, and education), household perceptions of vulnerability and capacity to respond to environmental hazards, and actions taken in the home to address climate change impacts or environmental hazards. The sample of 400 households (from a total of 79,178), gives a relative standard error of 5%, following Krejcie and Morgan [45]. Consequently, if 50% of the surveyed respondents believe information is important in aiding preparation, it can reasonably be expected that if the total household population were surveyed, the proportion of respondents that would agree with the statement would be between 45% and 55%.

Structured telephone interviews (n = 17) were conducted with surveyed households that nominated willingness to participate and who represented the diversity of households in the study areas (e.g., single parent, family households, employed, and unemployed). The sample size meets qualitative research good practice [46,47], and purposive sampling ensures outputs are ‘rich in terms of the constituencies and diversity’ represented [48] (p. 85). Three hazard scenarios (heatwave, severe storm, and sea-level rise) were presented (Table S3, Supplementary Materials) and interviewees were asked: (i) what the impact of each scenario would be on their household, (ii) how they would respond; and (iii) barriers to implementing the chosen response strategies (e.g., financial or human capacity constraints). Interviews averaged 30 min in duration, were recorded, and transcribed verbatim.

2.3. Data Analysis

Questionnaire data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics package. Chi-squared nonparametric tests were conducted to analyze differences in the desire for, and perceived utility of, information and independent variables such as risk perception, trust, and attitude towards climate information, past experience of environmental hazards, perceptions of household efficacy, and household characteristics (e.g., homeownership, income, length of residence in the local area). Proportional differences across each layer were examined using a Z-test. Binominal logistic regression models further analyzed the likelihood of the independent variables in shaping the perceived utility of information. The significance of results was assessed at the 0.05 confidence level.

Interview data were analyzed using a deductive approach. Interview transcripts were qualitatively analyzed, and references to information were coded according to information type: passive, interactive, or experiential information (following [26]). Building on the categories of Becker and colleagues [26], life experience even if not hazard-related (often described as ‘common sense’ by interviewees) was categorized as a form of experiential information. Differences in the type of information used by households were coded by hazard type (i.e., severe storm, heatwave, and sea-level rise) and by the role information played in household perceptions or response. For example, information may have: (i) shaped the choice of action implemented or instigated the implementation of action; (ii) influenced perceptions of risk, the efficacy of coping strategies, and the perceived need for action; and/or (iii) was anticipated to aid future preparation and/or hazard response.

3. Results

3.1. The Importance of Passive Information

Most households placed high importance on passive information that detailed their exposure to climate hazards (41.5% of respondents) and the nature of those hazards (42.1% of respondents) (Table 1). Only a small proportion (13%) did not believe information about their future exposure to climate change impacts was important in helping them prepare.

Table 1.

The perceived importance of information, by content, in helping households prepare for climate hazards.

3.2. Information Types That Resonate with Households

The information that resonated with householders was a function of household perceptions of vulnerability and capacity more so than household attributes (such as length of residence or family type). Householders who wanted more information about their exposure to future climate risks were those that: (i) perceived their local area to be vulnerable to environmental hazards (53.9% compared to 29.0% who did not consider the local area vulnerable, χ2 = 18.16, df4 **); (ii) considered local environmental health important to their households’ wellbeing (50.0% compared to 30.2% that did not believe local environmental health contributed to their households’ wellbeing, χ2 = 15.31, df1 **); and (iii) trusted government to act on climate change (48.9%, compared to 39.5% who did not trust government to act on climate change, χ2 = 21.4, df4 **).

In addition, households that placed a high value on information on how to prepare for climate hazards were those that: (i) believed households in the local area were very capable of managing the impacts of environmental hazards (49.2% compared to 30.2% who did not believe households were very capable, χ2 = 21.64, df4 **); (ii) considered their local council capable of preventing harm from environmental hazards (44.0% compared to 24.6% who believed their council was not capable, χ2 = 15.88, df4 **); and (iii) trusted the government to act on climate change (42.7% compared to 31.6% who did not trust the government to act on climate change χ2 = 11.24, df4 *).

3.3. Information Influencing Perceptions and Informing Adaptive Response

Despite the value assigned to passive information by survey respondents, passive information rarely informed interviewed householders’ response to the scenario hazards. In describing what might be needed to respond to heatwaves, interviewees often reported nothing was required if common sense was adopted: “I don’t think there is [anything] really. You use your common sense. If you do have to go out you don’t go out for very long.” (ID307). Another resident commented that their storm preparedness was a function of household day-to-day planning and common sense: “Paying rent, day-to-day financial management; storm preparation and awareness are part of that preparation. If you are going to have a hazard like that affect your household it is going to affect your budget. So, it is all part and parcel of preparation” (ID 27). Household action to respond to each scenario hazard was primarily informed by experiential information in the form of direct hazard experience or common-sense responses to manage the hazard (Table 2). For example, one Mandurah resident referenced previous experience of storms when describing how prepared their household was for storm impacts: “We did have a scenario here … we had a pretty severe storm and were out of power. So I have lots of candles and you just get by” (ID 275).

Table 2.

Information source and relationship to adaptive choice and risk perception.

Passive information (brochures and radio warnings) and interactive information (interactions with others) also shaped household response or risk perceptions; however, the influence varied across the three scenario hazards (storms, heatwaves, and sea-level rise) (Table 2). For example, passive information guided households in deciding when to implement coping strategies for severe storms (e.g., securing loose items in the yard), while for heat waves passive information was considered a valuable support tool. For example, when reflecting on what might be needed to help households respond to heatwaves, two Mandurah residents stated: “So I think a warning from local government on the radio or television to tell people to prepare themselves, what the impacts might be and some tips on what they could do” (ID114); “They [the government] should give us advice … not concrete help but advice to people” (ID307). However, passive information rarely informed household responses to heatwaves or sea-level rise (Table 2).

Experiential information also influenced risk perceptions and views on whether proactive action was required. Indirect hazard experience shaped perceptions of vulnerability and household views regarding how they would respond to sea-level rise impacts. One Moreton Bay resident, for example, drew on their past exposure to a storm surge event to justify the limited need for action: “No I do not think it would be relevant for where we are located. The area has never been affected by those sort of floods … it hasn’t stopped us from doing the day-to-day things like getting kids to school” (ID107). However, experiential information was not referred to as an important source of information to guide ‘future’ action.

In contrast, passive information was expected to inform the types of action that would be taken if, or when, a household needed to act. For example, when describing how their household would respond to sea-level rise, two Mandurah residents anticipated their response would be informed by passive information provided by government authorities: “Well I think that they would have to give advice on what is happening… I think it needs to be some sort of government body to look into 40 or 50 years ahead” (ID 328); “I suppose [I would be] seeking advice again from government websites” (ID 206).

Interactive information in the form of face-to-face interactions with familiar or unfamiliar contacts was rarely cited when discussing information needs or household response. However, it was important for a migrant resident with limited experience of summer storm conditions: “Newcomers to Australia like me [living in Australia for 4 years] …… I have never known weather like I have experienced in Australia … So I suppose, and I had never thought of this before, it would have been nice to have had more information and not just rely on people coincidentally telling you … I relied on friends saying you have to tie things down … So they were my source of information. I suppose I could have found information if I looked but I didn’t even think of it” (ID 114).

The information shaping action differed by hazard type based on its availability and the householder’s perceived exposure to the hazard. Householders valued passive information provided by government authorities, particularly for hazards that they were less inclined to prepare for (i.e., heat waves and sea-level rise). However, experiential information most frequently informed household response and was often referred to as ‘common-sense’.

Household responses to the scenario hazards were predominantly coping strategies, such as securing loose items in the yard. Actions classified as adaptive (e.g., installing window protection) or collective (e.g., participation in resident or coastal groups) were limited by comparison. The lack of adaptive and collective action (such as joining local recovery or conservation efforts) to respond to environmental hazards was also evident across surveyed households (see [39] for further detail).

4. Discussion

To promote a shared response to the impacts of climate change, governments are providing information to households to modify their behaviors and their homes. In Australia households can access information on climate risk via Government-supported online communication platforms, such as ‘Climate Change in Australia’ (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au) (accessed on 10 July 2021). This national resource contains information on past climate trends and projections for future climate change across the country. ‘CoastAdapt’ provides another source of information on projected climate change impacts as well as tools for adaptation planning in coastal regions (https://coastadapt.com.au) (accessed 31 June 2021). Australian State governments have also sought to engage households in adaptation via online information platforms (such as ‘AdaptNSW’ https://climatechange.environment.nsw.gov.au (accessed on 1 March 2022)).

Yet while such passive information is valued by households, it is not adopted to inform adaptation response. Households are coping with climate hazards and these coping strategies are informed by common sense. The dominance of coping in contrast to proactive planned adaptation is consistent with evidence from other contexts (e.g., [49,50]). In our case, interviewed households anticipated they would adapt to climate impacts such as sea-level rise ‘in the future’, and that passive information would guide this response. Yet, what promotes the transition from coping to adaptation, and the associated seeking of information to inform that response, is unclear. Evidence would suggest exposure to impact is a driving factor [51,52]. Is proactive planned household adaptation in the absence of experienced threat therefore unachievable, or can adaptation be viewed as ‘common sense’ prior to impact?

Common sense is one’s ‘ability to think about things in a practical way and make sensible decisions [Oxford dictionary]; and can be informed by a range of information sources (passive, interactive, or experiential). Over time information is gathered through either practical application or social interactions (observation or conversation) and is engrained in the social practices of the household. While common-sense can be informed by multiple information types, the timeframe between exposure to information and acceptance as ‘common sense’ is uncertain. Thus, when information is advocated as the solution to supporting household adaptation a question rarely asked is, ‘What types and content of information resonate with coastal households?’

We found that not all information relating to climate risk resonates with households equally. Differences are a function of household experience and perceptions of exposure and capability. Thus, providing information regarding how to adapt, in the absence of building perceived capability to act, is unlikely to deliver sought after adaptation outcomes [53]. Based on a review of coastal household adaptation and its drivers, Koerth et al. [35] recommended communicating the efficacy of household-level adaptation in addition to information regarding hazard risk. In other contexts, perceived capability alone has not been sufficient to support anticipatory adaptation. Ung et al. [54], for example, found that while perceived capability was a key driver of coping strategies (or reactive adaptation responses), education had the greatest effect on anticipatory adaptation in Cambodia. Thus, the relative importance of information differs by context and will have differential effect on households based on their unique situation.

By design, passive information seeks to reach a wide audience through, for example, online communication, pamphlets, or radio communication. It therefore rarely contains targeted information that can capture the interest of all households [55]. As such, there is value in moving beyond passive communication approaches. Interactive techniques have been adopted in environmental hazard and sustainability contexts, such as climate mitigation or reducing water use, with reportedly effective outcomes. Workshops, demonstrations, community events [56] and harnessing opinion leaders [57] are two-way communication tools that provide opportunities for collective discussion where participants can share experiences, beliefs, and values, building trust and collaboration. However, they are not a panacea. For example, one-off information dissemination in a workshop setting has proved ineffective in changing an indigenous communities’ perceptions of climate change [58].

Furthermore, the passive information communication mechanisms adopted by the Australian government target households as a key end user; however, they also count local governments and the business sector amongst their target audience. As a result, the content households can access tends to include information on risk exposure at regional scales, sector-specific climate hazards and responses, and potential adaptation strategies proposed by, and for, local governments. Information that guides household-scale responses to a changing climate is limited by comparison and is provided on a hazard-by-hazard basis by relevant authorities (e.g., emergency management authorities, health authority, and water authority). This approach is not unique to Australia. For example, in the Netherlands, communication regarding one climate risk, flooding, is delivered through dedicated ‘flood risk’ campaigns [59].

Thus, adaptation information is delivered to households in a manner that promotes itemized and individualized risk management. Consequently, households are viewed as individual agents who will act to reduce their personal risk, rather than as integral actors within a broader system whose responses (individual and collective) contribute to the vulnerability and sustainability of coastal areas.

Householders mitigate and adapt to climate change in the home and contribute to social change via participation in collective action. Yet these multiple roles are rarely captured in empirical assessments of coastal adaptation—where focus is placed on individual responses to discrete hazards [53]. So too, in this study, collective action and adaptation were rarely considered nor implemented by coastal households. Therefore, the types of information (passive, integrative, and experiential) informing different categories of household response (coping, adaptation, and collective action) is unclear. This remains an important area for future research, particularly in the global north where assessments rarely examine collective responses and associated drivers (although, see [60] for a discussion on information delivery to support collective mitigation responses), compared to assessments of coastal household adaptation in the global south (e.g., [61,62]).

Passive communication is not obsolete. Some households value passive information, as do researchers who advocate the adoption of multiple communication approaches (e.g., [56,63]). The challenge is determining what combination of information types (and content) have resonance with households (e.g., [19,64]) and how delivery (passive, experiential, or interactive) influences uptake and subsequent adaptive response. For example, Tran et al. [65] found informal communication was the dominant learning approach in rural Cambodia. As new strategies are implemented globally to engage citizens in adaptation, such as joint knowledge gathering (see the European Union’s Climate Resilient Europe mission [9]), there will be additional opportunities to explore diverse communication and engagement approaches on civil society’s climate change response.

For now, if resilience is indeed the objective sought through household’s participation in a shared approach to adaptation [8], communications to promote household response must transition from independent and itemized passive delivery via distinct streams. This could be achieved, for example, by communicating adaptation as the ‘glue’ between hazard management and resource sustainability practices within the home. Under this approach, adaptation communication would focus on demonstrating households’ role in progressing towards sustainable futures, promoting a stronger look inward, ‘how can we build our households capacity for change’, to build on the already growing focus outward, ‘how can we ensure governments implement change’. This may entail communicating attributes of capability and how they can be developed. There remains a role for action-oriented guidance. However, if households are to play a more integral role in transitioning to sustainable coastal futures, they cannot solely be viewed as stop gap responders to isolated impacts.

5. Conclusions

We explored a knowledge gap relating to information provision and effects on adaptation action. We found that passive information was used by less than half of households for adaptation responses, and of those, it only informed coping strategies in most cases. While experiential information informed action in most households, it similarly mainly informed coping strategies. Consequently, passive information rarely promotes adaptive action by coastal households. This research was conducted in peri-urban coastal settings prior to the global pandemic and future research should extend to other coastal contexts (rural and city areas).

As the impacts of climate change continue to be felt, the importance of civil society’s engagement in adaptation will intensify, with authorities continuing to investigate the most appropriate ways to support household adaptation. Current emphasis on passive information provision as the tool to facilitate adaptation across the global north is unlikely to deliver sought-after outcomes. Decision makers need to consider novel and diverse information channels if households are to transition from coping to adaptation. The utility of communication approaches will differ by context, highlighting a need for further research investigating the influence of information delivery modes (passive, experiential, and interactive) on adaptation response (e.g., coping, adaptation, private action, and collective action).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su14052904/s1, Table S1: Socio-demographic characteristics, City of Mandurah, Table S2: Socio-demographic characteristics, Moreton Bay Coastal Region; Table S3: Scenario hazards presented to interviewees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.E.-B.; formal analysis, C.E.E.-B.; methodology, C.E.E.-B.; resources, T.F.S.; writing—original draft, C.E.E.-B.; writing—review and editing, T.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the support of the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Projects Funding Scheme (Projects FT180100652 and DP1093583).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of University of the Sunshine Coast (Approval Number is A/12/351).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data is confidential in accordance with Ethics approval (A/12/351).

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Stephanie Toole for initial collaboration and discussions regarding household information use and its relationship to adaptation in Australia. This work contributes to Future Earth Coasts, a Global Research Project of Future Earth. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Australian Government, the Australian Research Council, or Future Earth Coasts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.C.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Nicolai, M.; Okem, A.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC Summary for Policymakers. In IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–765. [Google Scholar]

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Nicholls, N.; Easterling, D.; Goodess, C.M.; Kanae, S.; Kossin, J.; Luo, Y.; Marengo, J.; McInnes, K.; Rahimi, M.; et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Dokken, D.J., Ebi, K.L., Mastrandrea, M.D., Mach, K.J., Plattner, G.K., Allen, M., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; pp. 109–230. [Google Scholar]

- Vousdoukas, M.I.; Ranasinghe, R.; Mentaschi, L.; Plomaritis, T.A.; Athanasiou, P.; Luijendijk, A.; Feyen, L. Sandy coastlines under threat of erosion. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 260–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, P.R.; Widlansky, M.J.; Hamlington, B.D.; Merrifield, M.A.; Marra, J.J.; Mitchum, G.T.; Sweet, W. Rapid increases and extreme months in projections of United States high-tide flooding. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government. The National Adaptation Programme and the Third Strategy for Climate Adaptation Reporting; UK Government: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 9781528607582.

- Government of Canada Federal Adaptation Policy Framework. 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/adapting/plans.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Commonwealth of Australia National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy; Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2015.

- Department of Agriculture Water and the Environment National Climate Resilience and Adaptation Strategy 2021–2025: Positioning Australia to Better Anticipate, Manage and Adapt to Our Changing Climate. 2021. Available online: https://www.awe.gov.au/science-research/climate-change/adaptation/strategy/ncras-2021-25 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- European Commission Proposed Mission: A Climate Resilient Europe; Brussles. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/climate-resilient-europe_en (accessed on 20 December 2021).

- Biesbroek, R.; Delaney, A. Mapping the evidence of climate change adaptation policy instruments in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 083005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, R.W. A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change. J. Psychol. Interdiscip. Appl. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, N.; Agrawala, S.; Mirza, M.M.Q.; Conde, C.; O’Brien, K.; Pulhin, J.; Pulwarty, R.; Smit, B.; Takahashi, K. Assessment of Adaptation Practices, Options, Constraints and Capacity. In Climate Change 2007, Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Parry, M.L., Canziani, O.F., Palutikof, J.P., van der Linden, P.J., Hanson, C.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Field, C.B.; Barros, V.R.; Dokken, D.J.; Mach, K.J.; Mastrandea, M.D.; Bilir, T.E.; Chatterjee, M.; Ebi, K.L.; Estrada, Y.O.; Genova, R.C.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bird, D. Future Change in Ancient Worlds: Indigenous Adaptation in Northern Australia; Charles Darwin University, National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF): Goldcoast, Australia, 2013.

- Füssel, H.-M. Vulnerability: A generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2007, 17, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poussin, J.K.; Botzen, W.W.; Aerts, J.C. Factors of influence on flood damage mitigation behaviour by households. Environ. Sci. Policy 2014, 40, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretikos, M.; Eastwood, K.; Dalton, C.; Merritt, T.; Tuyl, F.; Winn, L.; Durrheim, D. Household disaster preparedness and information sources: Rapid cluster survey after a storm in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health 2008, 8, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Armstrong, C.L.; Cain, J.A.; Hou, J. Ready for disaster: Information seeking, media influence, and disaster preparation for severe weather outbreaks. Atl. J. Commun. 2021, 29, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, M.; Nursey-Bray, M.; Rudd, D. Perception and Vulnerability of Slum Communities to Climate Change in Accra, Ghana. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2019, 19, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mortreux, C.; Barnett, J. Adaptive capacity: Exploring the research frontier. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson-Easey, S.; Bi, P.; Hansen, A.; Williams, S.; Nitschke, M.; Saniotis, A.; Zhang, Y.; Hodgetts, K. Public Understanding of Climate Change and Adaptation in South Australia; National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF): Gold Coast, Australia, 2013.

- Lo, A. The role of social norms in climate adaptation: Mediating risk perception and flood insurance purchase. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, C.; Gill, N. Bushfire and everyday life: Examining the awareness-action ‘gap’ in changing rural landscapes. Geoforum 2010, 41, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, J.; Adger, W.N.; Lorenzoni, I.; Abrahamson, V.; Raine, R. Social capital, individual responses to heat waves and climate change adaptation: An empirical study of two UK cities. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2010, 20, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.S.; Paton, D.; Johnston, D.M.; Ronan, K.R. A model of household preparedness for earthquakes: How individuals make meaning of earthquake information and how this influences preparedness. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 107–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, K. Thinking Habits into Action: The Role of Knowledge and Process in Questioning Household Consumption Practices. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 95–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G.; Roggeveen, K.; Gordon, R.; Butler, K.; Cooper, P. Tyrannies of thrift: Governmentality and older, low-income people’s energy efficiency narratives in the Illawarra, Australia. Energy Policy 2016, 90, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, L.; Farbotko, C.; Gibson, C.; Gill, N.; Waitt, G. Zones of friction, zones of traction: The connected household in climate change and sustainability policy. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 20, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strengers, Y. Negotiating everyday life: The role of energy and water consumption feedback. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 319–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; O’Neill, S.; Lorenzoni, I. Public engagement with climate change: What do we know and where do we go from here? Int. J. Media Cult. Political 2013, 9, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C. Communicating adaptation to climate change: The art and science of public engagement when climate change comes home. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2014, 5, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. A reexamination on how behavioral interventions can promote household action to limit climate change. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisa, C.F.; Bélanger, J.; Schumpe, B.M.; Faller, D.G. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials testing behavioural interventions to promote household action on climate change. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koerth, J.; Vafeidis, A.; Hinkel, J. Household-Level Coastal Adaptation and Its Drivers: A Systematic Case Study Review. Risk Anal. 2016, 37, 629–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaller, N.L.; Kelmenson, S.; BenDor, T.K.; Spurlock, D. From abstract futures to concrete experiences: How does political ideology interact with threat perception to affect climate adaptation decisions? Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 112, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycoo, M.A. Autonomous household responses and urban governance capacity building for climate change adaptation: Georgetown, Guyana. Urban Clim. 2014, 9, 134–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Thomsen, D.C.; Preston, B.L.; Smith, T.F. Perceptions matter: Household adaptive capacity and capability in two Australian coastal communities. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Smith, T.; Preston, B.; Thomsen, D.C.; Baum, S. How are coastal households responding to climate change? Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 63, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Smith, T.; Thomsen, D.C.; Preston, B. Perceptions of Risk among Households in Two A ustralian Coastal Communities. Geogr. Res. 2015, 53, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Burton, D.; Mallon, K.; Taygfeld, P.; Laurie, E.; Bowra, L. Scoping Climate Change Risk for MBRC; Climate Risk Pty Ltd: Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- DCCEE. Climate Change Risks to Australia’s Coast: A First Pass National Assessment; Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2009.

- Elrick-Barr, C.E. Understanding Household Adaptive Capacity: Case Studies from Coastal Australia; University of the Sunshine Coast: Sippy Downs, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fontana, A.; Frey, J.H. Interviewing: The Arts of Science. In Handbook of Qualitative Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume I, pp. 361–376. ISBN 0803946791. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How Many Interviews Are Enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namey, E.; Guest, G.; McKenna, K.; Chen, M. Evaluating Bang for the Buck. Am. J. Eval. 2016, 37, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Lewis, J. Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, F.A.; Ahmad, M.M. Effect of climate finance on adaptation in the southwestern coastal region of Bangladesh. Dev. Pr. 2020, 30, 905–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.J.; Dessai, S.; Tompkins, E.L. What do we know about UK household adaptation to climate change? A systematic review. Clim. Chang. 2014, 127, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koerth, J.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Hinkel, J.; Sterr, H. What motivates coastal households to adapt pro-actively to sea-level rise and increasing flood risk? Reg. Environ. Chang. 2013, 13, 897–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, J.; Quade, D.; Becker, J. Integrating the effects of flood experience on risk perception with responses to changing climate risk. Nat. Hazards 2014, 74, 1773–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdlenbruch, K.; Bonté, B. Simulating the dynamics of individual adaptation to floods. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ung, M.; Luginaah, I.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Campbell, G. Perceived Self-Efficacy and Adaptation to Climate Change in Coastal Cambodia. Climatie 2016, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCaffrey, S. Fighting Fire with Education. J. For. 2004, 102, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen, C.; Prior, T. The art of learning: Wildfire, amenity migration and local environmental knowledge. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2011, 20, 612–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keys, N.; Thomsen, D.C.; Smith, T. Adaptive capacity and climate change: The role of community opinion leaders. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fernández-Giménez, M.E.; Batkhishig, B.; Batbuyan, B.; Ulambayar, T. Lessons from the Dzud: Community-Based Rangeland Management Increases the Adaptive Capacity of Mongolian Herders to Winter Disasters. World Dev. 2015, 68, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haer, T.; Botzen, W.W.; Aerts, J.C. The effectiveness of flood risk communication strategies and the influence of social networks—Insights from an agent-based model. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 60, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.F.; Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Seekamp, E.; Strnad, R. Evaluating climate change behaviors and concern in the family context. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.B.; Jacobs, B.C.; McKenna, K.; Kuruppu, N. Female contribution to grassroots innovation for climate change adaptation in Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 2019, 12, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, L.; Brander, L.; van Beukering, P.; Dijkstra, H.; Franco, C.; Hughes, L.; Gilders, I.; Segal, B. Community-based adaptation to climate change in small island developing states: An analysis of the role of social capital. Clim. Dev. 2019, 11, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCaffrey, S. Community Wildfire Preparedness: A Global State-of-the-Knowledge Summary of Social Science Research. Curr. For. Rep. 2015, 1, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raile, E.D.; Shanahan, E.A.; Ready, R.C.; McEvoy, J.; Izurieta, C.; Reinhold, A.M.; Poole, G.C.; Bergmann, N.T.; King, H. Narrative Risk Communication as a Lingua Franca for Environmental Hazard Preparation. Environ. Commun. 2021, 16, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.A.; James, H.; Pittock, J. Social learning through rural communities of practice: Empirical evidence from farming households in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 2018, 16, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).