Abstract

The relationship between food and cities has been recognized as an area of interest for urban planning only recently, thanks to measures adopted at various government levels, locally and internationally. Rethinking the processes of food production, distribution, sale, consumption and recycling in a sustainable and socially equitable way can contribute to making cities fairer, healthier and more resilient to climate change. Starting from these premises, our contribution explores, in particular, the hypothesis that rethinking the relationship between food and urban space can provide an opportunity to promote socio-spatial regeneration processes of public housing neighbourhoods, through projects and actions that involve their inhabitants. This hypothesis is argued starting from a project experience developed in Borgo San Sergio, a district of Trieste, Italy, which aims to consolidate and enhance practices of cultivation and distribution of food, but also of environmental education. The aim of the project is to create a short supply chain in which social agricultural enterprises are involved. The critical reflection stemming from the case study outlines some possible fields of intervention for an urban planning practice aimed at bringing the food system back to an urban and local scale—downscaling—with social and environmental justice goals consistent with the European Green Deal.

1. Introduction

The relationship between food and the city began to develop as an urban issue in the 1970s; however, it is only in recent decades that the urgency to consider food as a topic of urban planning [1,2] or urban design has emerged [3,4,5,6]. Starting from the new millennium, surveys and investigations have helped to outline this relationship in terms of a ‘new food equation’ that brings into play issues relevant to urban design such as the ones about the environment, social justice and public health [7,8,9,10]. Furthermore, the launch of intervention programs promoted by governmental bodies, primarily FAO and WHO [11,12], has also led to acknowledge the city as a strategic space for the activation of policies and actions in response to global problems related to food production and consumption [13,14,15,16,17]. In 2015, the adoption of the 2030 Agenda by the United Nations gave a further boost to crediting cities with a fundamental role in the sustainable transformation of food systems: administrative bodies were thus urged to adopt food policies and multi-layered action plans to respond to the Global Goals. At the international and European level, these initiatives are now acknowledged as good practices to be shared and disseminated to help cities adopt integrated food policies, in order to reduce climate-changing emissions, promote public health, and reduce social inequalities [18].

Since 2019, then, with the Green New Deal introduced by the European Commission to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, numerous directives and strategies have been promoted for a sustainable transformation of the agricultural sector [19]. The 2020 pandemic, highlighting the close correlation between health crisis and environmental crisis, has further reinforced the need to speed up the process of transformation of food systems [20,21,22]. As part of the Green New Deal, this has resulted in the promotion of ‘Farm to Fork’ [23] and biodiversity strategies [24]. Overall, this is a framework of guidelines that confirm and reaffirm objectives towards a series of goals: reducing the impact of the food chain on the environment and the consumption of resources; increasing the resilience of soils to climate change; guaranteeing access to food and food security; supporting employment in rural and urban areas.

These initiatives are part of an increased awareness of how urgent it is to intervene both in the spaces meant for the activities of production, distribution, consumption of food and the behaviour and eating habits of individuals to achieve a paradigm change in the food system [25]. Urban spaces play a strategic role in this by favouring accessibility to food, encouraging well-being-oriented behaviours and practices, developing the capacity of fragile subjects to access food resources [26]. Urban plans and projects thus turn out to be decisive tools in implementing urban transformation strategies that can go in this direction. However, it is equally clear that bringing the food system back to an urban and local scale [27]—i.e., downscaling or rescaling—is a complex process that involves the relationships between urban systems and their productive hinterlands [28]. Adopting downscaling or rescaling strategies means, first of all, bringing the agricultural food production closer to the places of consumption, but it also involves making all the steps of the food chain sustainable to ensure urban metabolism efficiency. Making food ‘local’ is a fundamental step in starting to counter the globalization of food systems and the distortions that characterize it. In addition to the aforementioned environmental damage, we must remember the negative effects linked to the commodification of food, food waste in the face of high percentages of people in conditions of food insecurity, the growing productions destined to feed animals and producing biofuels, and the known phenomena of land grabbing that push richer countries to buy land in poorer countries in order to produce food [29].

Reterritorializing the food system involves combining top-down and bottom-up actions within a renewed framework of norms, rules, tools and design strategies in which attention to food processes becomes, in effect, a theme of urban planning. A theme that brings us back to the designing of agro-urban systems developed at different scales and that recalls a multidisciplinary approach where different fields of action are intertwined: landscape care and welfare policies, to which are necessarily accompanied by economic policies in support of sustainable agriculture and small producers necessarily add up, are some of these.

Starting from such premises, our contribution intends to explore more in depth the relationship between the reterritorialization of agrifood systems and the redevelopment projects of urban suburbs, with particular attention to the strategic role that parts of the ‘public city’ can play, that is, to that set of neighbourhoods built by the public operator—in particular during the second half of the twentieth century—to satisfy the housing needs of individuals who cannot access the private housing market [30].

The results of a multi-year research activity on the Italian and European ‘public city’, carried out and coordinated by the authors, have shown how many of its constituent parts are strategic for larger urban redevelopment projects.

More recently, the chances of interweaving the redevelopment of the public city with strategies for enhancing the peri-urban condition that characterizes many of its neighbourhoods, highlighting their proximity to cultivated and natural margins, have multiplied. Specifically, the hypothesis we outline is that rethinking food processes in a resilient key with the tools of urban planning allows to promote socio-spatial regeneration paths of public housing districts through open and flexible projects that involve settled communities [31]. The aim is to demonstrate how initiatives based on the support and dissemination of food cultivation, production, distribution and education practices in neighbourhoods can activate projects that follow and meet the objectives of the Green New Deal, fostering resilient transformations of the city as a whole. Such transformations aim, among other things, at inserting patches of permeable soil into the urban space, enhancing the involvement of the inhabitants in practices of care and maintenance of their territory and inhabited spaces, promoting healthy and outdoor lifestyles, supporting urban agriculture to open up paths of social integration, disseminating initiatives to ensure a healthy diet for weaker groups of people.

After a brief review of some of the approaches adopted so far in the field of urban planning to support a fair and sustainable transformation of food systems, a specific experience carried out in the city of Trieste, Italy, will be illustrated, which intended to spread social agriculture and the establishment of agrifood micro supply chains between the city and its hinterland in order to promote sustainable forms of production and social integration. From the critical reflection on the outcomes of the case study presented, the focus will be broadened again to outline some possible fields of intervention for an urban planning practice aimed at bringing the food system back to an urban and local scale, precisely to set objectives of social and environmental justice that are consistent with the European Green Deal.

2. Food Systems between the Urban and the Agricultural

It may be useful to recall the themes around which the urban planning and urban design debate on ‘food and the city’ has progressively polarized in recent years—and which translated into different policies and projects that have swept over urban spaces—in order to set up the framework where the research experience briefly reported here and the argued hypotheses can find their place.

In recent decades, actions and urban transformation projects promoted by local administrators in many European cities have tried—albeit in different ways—to reconstitute the relationships between urbanized and agricultural spaces. On the one hand, the growing attention to the landscape has prompted us to re-observe the countryside from a perspective that is not only a productive one, urging the implementation of strategies and directions aimed at restoring its peculiar traits and reducing the loss of biodiversity resulting from forms of intensive cultivation and abandonment, making it more resilient to climate change [32]. In particular, the ‘peri-urban’ [33]—the threshold between city and countryside—is increasingly taken up as a space for design experiments aimed both at redeveloping peripheral areas and urban margins, and at enhancing the multifunctionality of agricultural space as a place of food production, playful rediscovery practices of the territory and its resources, and ecological-environmental recomposition between urban and rural areas. In the Italian context, for example, this special attention has been developed in various critical reflections [34,35,36] and has found its translation into concrete experiences of planning [37] and urban design [38].

On the other side, instead, renewed attention has been drawn to the theme of urban agriculture in its many forms, initially recognizing its strategic role, also from an economic point of view and especially for developing countries, to ensure sustenance and independence to the population’s poorest sections [39,40,41,42,43,44]. Similarly, in many European cities shared gardens, community gardens and common spaces for activities linked, for example, to food consumption and education have been increasingly spreading for some time also thanks to the activism of self-organized citizen groups. This has led many local administrators to support and encourage cultivation practices in the city, recognizing their potential for social cohesion, usefulness for ecological and environmental purposes, and their function as a driver of recovery for abandoned urban spaces [36,45,46].

Furthermore, in its broadest sense of ‘food system’, food comes to be linked to the city by urban planners through a new focus on the sphere of the rights of individuals and specifically of a right to the city [47], understood as the right to access the resources and opportunities it can offer. The relationships with the urban planning discipline and its design tools are also easy to understand in this sense, especially if we remember how the protection of these rights has been guaranteed by welfare policies aimed at achievingwider and more widespread habitability of the urban space through the construction of homes, schools, sports and health facilities, green areas, etc. [48,49]. Although food has never been the explicit subject of such policies, it is nevertheless known that some of the most important transformations of the twentieth-century city are linked to studies, research and projects where the living space was rethought starting from the areas destined for food production, even if in a domestic sphere—e.g., family gardens in working-class neighbourhoods—and the rituality of its preparation and consumption—e.g., in the studies on the functional accommodation and the Frankfurt minimal cuisine—helping to ensure better conditions to people’s lives [50,51,52].

The relationship between food and the city read through the lens of rights has gradually found a double unfolding in the context of urban planning. In the first place, the transition from the concept of ‘food safety’ to that of ‘nutritional safety’ [53] has attributed an ever greater centrality to a widely intended factor of accessibility. Food security and foodability are concepts that refer to a concept of accessibility that takes into consideration, in addition to the physical distance from the places of food production and distribution, the economic conditions of users and their individual ability to recognize and secure healthy and appropriate food [54,55]. The debate on nutritional safety thus understood also arises in response to the problem of food deserts: cases of cities in contraction where conditions of economic crisis, demographic decline and reduction of community services have been eventually translated into a condition of ‘inaccessibility’ or limited access by the inhabitants of larger neighbourhoods and areas to healthy and appropriate food at affordable prices. The example of Detroit is well known, where the strategic plan for relaunching this city was conceived starting from the growth of widespread vegetable gardens carried out by the local communities in disused urban spaces [56]. Cases like this today push us to attribute a non-secondary role to food movements—or civic food networks—in rewriting the space of law and citizenship through self-organized and sustainable forms of production, purchase and distribution of food [57].

At the same time, the food question is here entwined with the issues of ‘healthy’ or ‘active’ cities [58,59], particularly present in urban planning research; it is indeed important to observe that urban open spaces do not play a secondary role in encouraging behaviours and lifestyles that, along with a balanced diet, can help ensure the health and well-being of the population. A working prospect is thus outlined that sees the relationship between food and the city reflected spatially not only in the places of production/distribution/consumption, but also in the entire city, that is then interpreted as a potential space for practices and activities that can affect factors such as sedentary lifestyle, ageing, stress linked to environmental conditions and habits which, together with an incorrect diet, may favour the onset of chronic or debilitating diseases and pathologies. Along with parks, cycle paths, pedestrian areas and similar facilities, food spaces in urban contexts can then also improve the capability and health of individuals, especially those who are fragile and in difficulty [60].

Finally, the attention to the relationship between food and cities has recently prompted new city projects that follow up in the wake of an important theoretical and design tradition: to quote the best known, just think of the proposals by John Claudius Loudon for London (1829), by Ebenezer Howard for The garden city (1898) or by Frank Lloyd Wright for Broadacre city (1934–1935). More recently, the futuristic visions for Agronica by Andrea Branzi (1993–1994) and the ideas of rural urbanism proposed by Aldo Cibic are equally interesting [61]. These are just some of the examples of a branch of the urban planning discipline that has placed the relationship between city and agricultural space, interpreted in its many forms, at the centre of design [62,63,64]. The acknowledged intersection of urbanization phenomena and environmental crisis pushes us today to renew our attention to agriculture as an opportunity to formulate proposals for safer, more resilient and more sustainable cities through new urban utopias [65]. The projects for La Grand Pari(s) (2007–2009), Agropolis München by Jorge Schröder and Kerstin Hartig (2009), the many experiments by groups such as Soa Architects and Agence Babylone, offer visions of future cities where agricultural and built spaces are recomposed in new urban forms, even if too often resulting in conciliatory images of peaceful cohabitation and coexistence between humans and nature [66].

Taken together, these ramifications outline possible fields of action for an urban design looking to resilience and the repositioning of agricultural spaces in a new cycle of resources and spaces [67]. They urge us to observe in a new light the multiplicity of abandoned, disused, liminal or interstitial spaces that give the contemporary city its porosity and transformability. From this point of view, settlement porosity lends itself to play a significant design role in terms of climate resilience and urban regeneration: the presence and succession of open and empty spaces, the point-like geography of brownfields, the places of proximity to living, the thresholds between public and private where nature can percolate and infiltrate represent a particularly favourable ecological and social potential for the purposes of adaptation processes to a changing climate. These are, then, potential places where projects, aimed at establishing organizational forms of food production, marketing and consumption in balance with the nature of the places, can at the same time act by increasing biodiversity, creating ecological corridors, making urban metabolism more efficient and improving the quality of the living space [68,69,70]. From this perspective, public housing districts look like the ideal candidates for intervention and experimentation: their frequently peripheral and peri-urban location, in addition to the wide and widespread presence of diversified open spaces, characterize these city parts as permeable and porous, therefore rich in the ecological potential that could be better exploited through cultivation and re-naturalization practices.

3. Food Spaces and Suburb Regeneration: A Case Study in Trieste

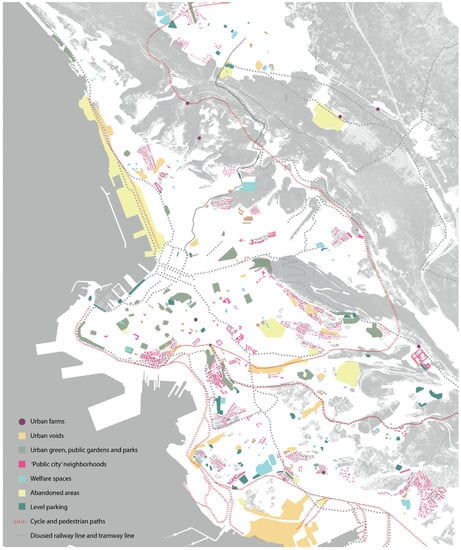

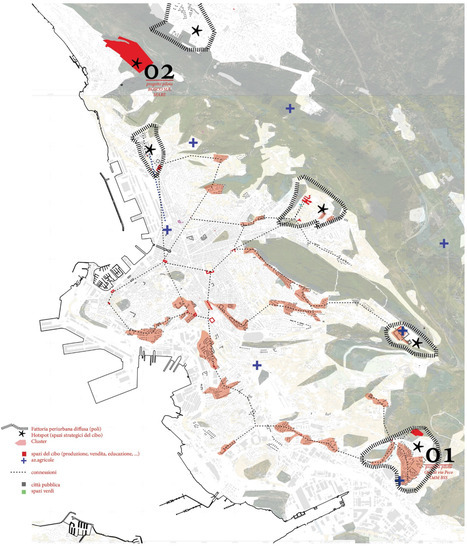

Themes and issues central to this reflection have been raised by the activities carried out in several districts of the city of Trieste by a group of scholars from our University. For over two decades, research programs, field surveys and hands-on field experiences, design laboratories and workshops, which have often involved inhabitants and subjects active in the area as well, have consolidated the belief that public suburbs are a fertile field of reflection and design experimentation on the contemporary city and are the background to urban issues at the centre of the scholarly debate (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A potential food network in the city of Trieste. The poles represent the public housing neighbourhoods, local farms, public green spaces and welfare spaces. Cycle and pedestrian paths, the tramway line and the abandoned railway line form a potential connection network. (Source: Martina Piazzi, MA Thesis, University of Trieste, supervisors: Paola Di Biagi, Sara Basso, Valentina Crupi).

In particular, among the diversified activities carried out in these contexts, the national research entitled ‘La “città pubblica” come Laboratorio di progettualità. La produzione di line guida per la riqualificazione sostenibile delle periferie urbane’ (The “public city” as a planning laboratory. The production of guidelines for the sustainable redevelopment of urban suburbs), coordinated by the University of Trieste—also involving the Milan Polytechnic, La Sapienza University of Rome, “Federico II” University of Naples and the Bari Polytechnic—has led to the drafting of guidelines for projects and actions to regenerate neighbourhoods and more generally urban suburbs.

Trieste, together with other cities of the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, has been a significant case study for the local research unit, a context in which to test the hypotheses set out in the premises to the research project and the guidelines that derived from it [71]. The use of participatory observation tools, qualitative field surveys and map readings has allowed for the assemblage of maps for the identification of resources and potential in the survey contexts. Readings and interpretations of the public city built with the help of local actors were the starting point for experimenting with different forms of an urban and territorial project guided by the principles of resilience and social justice.

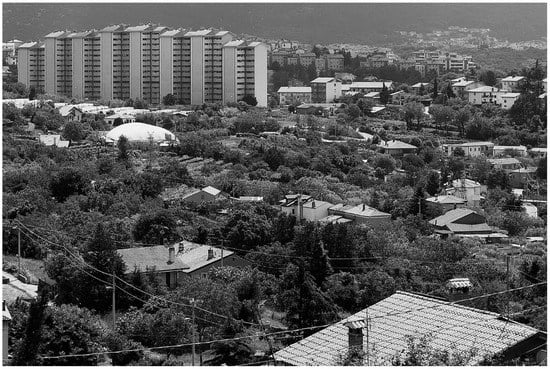

The following experience specifically concerns one of the large neighbourhoods in the south-eastern outskirts of Trieste, Borgo San Sergio [72,73], built between the 1960s and 1970s on a project by the well-known Milanese architect of Triestine origin, Ernesto Nathan Rogers, to respond to the serious housing needs of the second post-war period [74] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Borgo San Sergio neighbourhood in the south-eastern outskirts of the city: patches of the urban countryside and wooded spaces come to touch the built environment.

The district includes constructions of different building typologies (tower houses, block houses, in-line houses), as well as different types of collective services and equipment (schools, libraries, a church, sports equipment, proximity services, etc.); wide is the endowment of open spaces that are seamlessly practicable.

Over time, many apartments have been alienated and only part of the Borgo’s building stock present in the Borgo is now publicly owned (about 580 apartments): included in this property is also a building consisting of several juxtaposed towers ranging from 11 to 15 floors each and located along the Borgo’s north-west edge. It is precisely in this building that particular situations of hardship, marginalization and social fragility are concentrated. The dialogue with the territorial subjects active for years in the district has allowed the research group to identify its critical factors more precisely: compared to the demographics of the whole public property of the city of Trieste, Borgo San Sergio’s percentage of elderly people is not significant, while youth discomfort is more marked here than elsewhere. Its buildings, completed between the 1950s and the 1960s, have a low building quality ascribable to the poor energy efficiency of the building envelopes, the age of the windows and doors, the housing layouts that are not suitable to meet the many demands of one- or two-people family units any longer, the absence of elevators, etc. The inadequacy of the residential offer has led to a high number of vacant homes, increasing the risk of illegal occupations and contributing to the impoverishment of community relations and the weakening of support networks. Furthermore, field investigations and inspections have highlighted further critical elements related to physical and environmental degradation phenomena of open spaces, too: there are many gardens improperly used as parking lots, occupied by cars, abandoned or, again, targeted by unregulated forms of appropriation by the inhabitants. At the same time, the same inspections together with surveys and cartographic studies carried out by the research group using the tools of morphological analysis (readings by layer) have documented that there are important resources of a different nature, which refer above all to the morphological and settlement characteristics of this neighbourhood: wide availability of public open spaces that are broadly accessible; proximity to valuable landscape and environmental areas, such as the Karst plateau surrounding the city of Trieste; the presence of scraps of wilderness along the neighbourhood’s edges, with wooded residues and uncultivated spaces that have become a sanctuary for biodiversity. In sum, a composite set of patterns with different gradients of naturalness that offer an opportunity to redesign new connections between city and nature (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

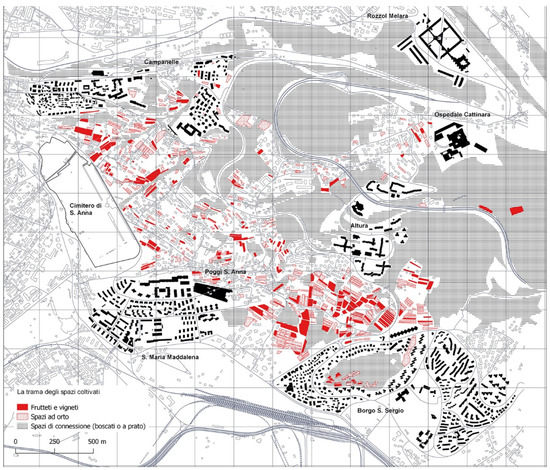

Figure 3.

Trieste, Borgo San Sergio. A system of agro-urban open spaces surrounds the neighbourhood and enhances its permeability (Photo by Mirko Pellegrini).

Figure 4.

Borgo San Sergio and the south-eastern outskirts of Trieste. An articulated system of open spaces insinuates itself into the city’s built south-eastern fringes, made up of orchards and vineyards (full pattern), vegetable gardens (dotted) and private gardens. Wide open wooded spaces and meadows (hatched) integrate and shape a potential connective system of naturalness. (Source: Mirko Pellegrini, Abitare territori intermedi. Declinare urbanità per riconoscere nuove forme di città. Esplorazioni nel Friuli-Venezia Giulia, PHD Thesis, University of Trieste, Trieste, 2015).

Other important resources in the neighbourhood are linked to the existing welfare services and facilities. This neighbourhood, in fact, is involved in the Habitat-Microaree project, active in the Trieste suburbs since 1998. Habitat-Microaree stemmed from a collaboration between the local Azienda Territoriale per l’Edilizia Residenziale (ATER—Area Corporation for Residential Housing), which manages the public housing heritage, the Municipality of Trieste and the local Healthcare Service Agency, to promote well-being and social cohesion in neighbourhoods with conditions of social hardship through integrated actions involving health, job placement and the improvement of housing conditions. In the neighbourhoods where it has been implemented, facilities have been created and located inside publicly owned buildings, where operators assist the inhabitants and act as social porters [75].

Starting from the reading and interpretation of such contextual conditions, the work of researchers from the University of Trieste in Borgo San Sergio has focused on the hypothesis that urban regeneration paths can be based on the valorization of welfare and agro-urban resources in this neighbourhood and its immediate vicinity (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Trieste, Borgo San Sergio. A potential system of food spaces between the neighbourhood and its surroundings (image by the students of the Urban Planning Laboratory 1, Paola Di Biagi, Sara Basso with Mirko Pellegrini and Valentina Crupi).

This hypothesis has been verified by resorting to action research tools: qualitative field investigations (perceptual readings, surveys, mapping of spaces and their uses) were aimed at reading the potentialities and criticalities of open and built spaces in greater detail, while analyses and cartographic readings at the various scales supported them and returned interpretative images of this neighbourhood and its territorial role. The research and project method adopted has led to outline transformation scenarios for Borgo San Sergio, where its role as a permeable margin between the city and peri-urban spaces is enhanced. Starting from this, the idea of strengthening its agro-urban vocation has been gradually clarified through processes of empowerment of local communities.

This has been the goal of a special collaboration between the Department of Engineering and Architecture at the University of Trieste (research group leader Paola Di Biagi; research group members: Valentina Crupi, Sara Basso, Elena Marchigiani, Mirko Pellegrini) and the InterLand social cooperative (chair: Dario Parisini), long active in the Trieste area also in the field of social integration and job placement for disadvantaged citizens [76], which created and gave shape to the ‘Orti di Massimiliano’ (OdM) project [77], partly financed by the Friuli Venezia Giulia Region. The aim was to consolidate and enhance—also via design explorations—the practices of cultivation-distribution of food in the neighbourhood and its vicinity through forms of social agriculture (according to the Italian law 141/2015).

Configuring a sustainable ‘short chain’ of on-site cultivation and sale of products thus attributes to social agricultural enterprises the role of bringing the agricultural space closer to the city, producing healthy food and ensuring its fair distribution, while developing practices of care of open spaces and generating relationships and social cohesion (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Borgo San Sergio: the neighbourhood features a high permeability of the spaces between the buildings, which inhabitants adapt to their different needs.

Since 2015, other cooperatives and associations that had developed further activities have been involved in the OdM project, too: in addition to fruit and vegetable production they have promoted environmental education initiatives—e.g., the “La Sapienza della Terra” project—, personal and community services—e.g., the “Viviana social farm” project—, activities related to well-being and health—e.g., the “Imaginal Mindfulness” project—, projects dedicated to people with mental disadvantages—the “Hubility” and “Artemisia” projects—, and actions targeting people at risk of social exclusion—UEPE–Bando devianza.

This set of initiatives provides as well for the strengthening and networking of spaces, where the facilities of the Habitat-Microaree project are based in the district. Consolidating these facilities and connecting them to wider networks, as advocated by the OdM project, also means imagining them as common spaces open to the entire community and not only to residents of public buildings, where activities related to food distribution, consumption and education connected with social agriculture may take place. Reconfiguring these social spaces by acting, for example, on the thresholds of mediation and relationship with their immediate context and inserting them into a wider local agricultural circuit made up of farms and small and widespread distribution hubs for cultivated products, can not only reduce the distance and the stages lying between food producers and consumers but create additional opportunities for integration in the neighbourhood and between neighbourhood and city.

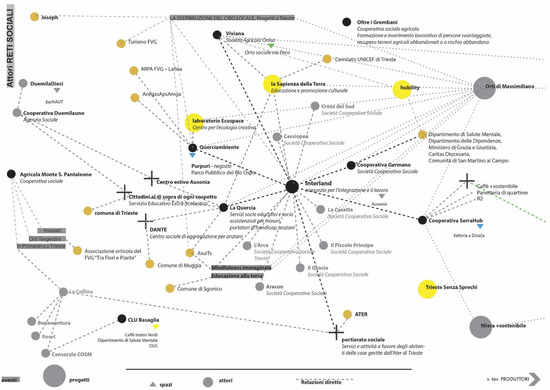

In order to work on all the hypotheses set forth by the OdM project, some research steps were fundamental. A first step was aimed at reconstructing and reading the existing food network of this context. To observe the ‘food network’ meant to recompose the system of relationships between actors of the agrifood system on an urban scale (in this case, the city of Trieste) and to verify whether there were chances to reorganize this system using innovative resilient models able to adapt to sudden changes, as has happened with the recent pandemic, thus creating the conditions for the consolidation of short food cultivation-distribution chains (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Trieste, Interland Cooperative. The ‘Orti di Massimiliano’ supply chain: reconstitution of the food network between the co-op and the local actors involved in the agricultural and social welfare system (source: Valentina Crupi, HEaD Higher Education and Development Project. Per un modello innovativo di agricoltura urbana [For an innovative model of urban agriculture], University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy, 2019. Research report).

As in many other national contexts, the Trieste area has seen the spread of new ways of producing (and self-producing), buying and consuming healthy and local food in the last decade. Solidarity buying groups, Community Supported Agriculture, community gardens and other forms of critical consumption represent organizational methods with significant civic and social as well as territorial repercussions, with consequences on the local production system [78]. Interlinking all these practices to consolidate a typical and local agri-food production economy, however, appears difficult also due to the almost total absence of urban and local food policies. In addition, we must consider the pulverization of agricultural micro-enterprises which for organizational, cultural and logistical reasons are not inclined to make investments in Civic Food Networks (CFNs).

One of the greatest difficulties in the OdM project was precisely to maintain the collaboration network between the subjects involved (local farms, social cooperatives, associations, catering and distribution companies, public institutions and the University of Trieste), a network particularly sensitive to external influences—such as has been with the pandemic—and local demands. If in recent years these difficulties have led to a downsizing of its initial targets—leading, for example, to the closure of a sales point of agricultural products in town—, the pandemic crisis has however urged to resume talks with institutions, in particular with the schools. The request for open-air teaching classes has been seen as an opportunity for greater involvement of the school population in the project and fulfilment of teaching goals. An opportunity to further enrich the meanings attributed to social agriculture, as well as to think about new ways of sharing public space at the time of Covid-19.

A second research step, conversely, was aimed at drafting a project masterplan (Figure 8), starting from the identification of spaces in the neighbourhood, and more generally in the peripheral context, where the food network finds visibility on the local scale in terms of cultivated land, points of sale, spaces for food processing, distribution, consumption, etc.

Figure 8.

Orti di Massimiliano, masterplan. Hypothesis for a local, sustainable and fair food system. Urban farms and farms spread across the territory are networked with the hotspots for the sale, distribution and consumption of food envisaged in public residential housing districts. Articulated connections between the neighbourhood and the territorial scale ensure the network efficiency (source: Valentina Crupi, HEaD Higher Education and Development Project. Per un modello innovativo di agricoltura urbana [For an innovative model of urban agriculture], University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy, 2019. Research report).

Referring to public districts located in peri-urban areas, we can try to define these ‘food spaces’ as places in which food production, processing and consumption, together with places where to develop food education activities, become an opportunity to activate (or support) processes of urban regeneration and to promote stable and temporary forms of sociality [79]. The forms of sociality alluded to are aimed at guaranteeing the right to the city, favouring the consolidation of support and aid networks for fragile people, encouraging forms of use and care to improve the ‘life cycles’ of urban spaces and reduce resource consumption.

The Borgo San Sergio masterplan developed for the Orti di Massimiliano project has tried to translate this definition of ‘food spaces’ through design, formalizing a set of areas that at different scales configure a sort of ‘peri-urban farm’ widespread in the city’s Karst hinterland. The farm is structured through a set of poles and connections that link and systematize them. These poles, or nodes, are represented by the places dedicated to the production, sale and consumption of local food—such as, for example, the local markets and osmize, traditional informal places in the Karst between Italy and Slovenia where wines and local products are sold and consumed directly in the premises of the businesses that produce them. We need to add some buildings to these, in particular, those where the activities of the Habitat-Microaree programme take place, redesigned as ‘food clusters’ where to develop agro-services and welfare spaces—for example, the ‘agrinido’, a country kindergarten.

These connections are articulated on a double scale: the territorial scale, where connections, including those with the quarters, are guaranteed by the existing and planned cycle and pedestrian paths, which include a nearby disused railway line; and the proximity scale of the neighbourhood’s inhabited areas, where the redesign of the internal pedestrian paths emphasizes and enhances their permeability, embracing the variety of open spaces and their ecological potential in terms of in-betweenness, thresholds, margins, etc. Nodes and paths can strengthen the relations between the rural territory of the Karst plateau and this part of the city exactly through neighbourhood spaces.

In summary, the Masterplan refashions Borgo San Sergio as a ‘hinge space’ where physical and functional transitions between the city and the peri-urban countryside surrounding Trieste can be redesigned. By exploiting the porosity of the neighbourhood and its many open spaces, it is possible to configure space systems between urban and rural areas with a high ecological-environmental value. Precisely in these systems, it will be possible to experience agricultural multifunctionality [80] and, more specifically, the potential of peri-urban cultivated areas in producing ‘civil food’ through the construction of inclusive and sustainable micro-supply chains [57,81] to promote greater social integration and improve the quality of living and open spaces.

The project strategies that the Masterplan implicitly suggests are strongly tied to the context and therefore difficult to apply in other situations. However, the process that has accompanied its construction may suggest a replicable method to involve the various territorial subjects in suburban regeneration paths. In such paths, as the experience presented here demonstrates, the University can play an important role in suggesting, using design tools and shared visions where neighbourhoods take on a strategic role as presidia of a territorial welfare system based on the enhancement of the agricultural multifunctionality of the peri-urban fringes in contact with the public city.

4. Discussion

The case study described and, more generally, the practices experimented with by the authors in recent years in the Triestine and Italian contexts, while responding to the drive to bring together suburb regeneration and food cycle reform, have highlighted the difficulty of consolidating firmly and durably even in such an innovative context as that of Trieste, a town of solid tradition in the field of welfare and social policies.

In the light of these difficulties, we can today identify possible strands of work to support the reterritorialization of the food system consistent with the objectives of the Green New Deal and, at the same time, promote shared regeneration paths in the public suburbs. At least four areas of reflection and action seem relevant to us.

4.1. Promoting Resilient Transformations of Agriculture as Opportunities to Renew the Welfare System

From a design perspective, the theme of suburb regeneration through social farming practices refers, more generally, to the issues of welfare territorialization, or to how policies aimed at the well-being of the community and the protection of the most fragile subjects translate into spaces where their related (social) services are provided [82].

We can therefore think of urban agriculture practices as an opportunity to outline new strategies for the spatialization of public policies aimed at improving the living and housing conditions of vulnerable subjects in contexts of social fragility. Areas intended for social or civic farming practices should therefore be considered as part of a more complex system in which more traditional food and welfare spaces—such as schools, social and health care centres, spaces for sport, cultural centres, etc.—are mutually integrated and connected [83]. Such a system requires the implementation of a diversified set of design devices aimed, for example, at improving sustainable mobility—public transport and cycle and pedestrian paths—, accessibility to service spaces and the quality of their relations with the public space and the city. Taken together, such actions can help strengthen urban resilience, both in social and ecological terms.

In the Italian context, however, there is still a lack of structural convergence between processes of welfare territorialization and urban regeneration strategies through forms of social agriculture. In social agriculture, as well as in other food policy initiatives, there is still a certain sectorial thinking that prevents its entering a systemic vision of the food system [13], and the possibility of linking its reterritorialization with the regeneration of urban areas affected by fragility such as the districts of the public city. Adopting a systemic vision means, for example, considering the opportunity to graft social farming practices onto other projects that impact the ways people live in neighbourhoods more transversally, interfacing with the spheres of home, work, health and instruction. It is necessary to imagine complex paths in which the care and sharing of agricultural spaces, and the ensuing forms of socialization, can ‘leverage’ more structured paths that involve other spaces in the public city—housing being the first among them—and other relational spheres [84]. The ways to do this are numerous, and even in the Italian context some interesting experiences try to experiment with the intertwining between food-related initiatives and home policies. In Milan, for example, job placements have been offered to diners in a solidarity restaurant open to people in difficult situations, who have been involved in the renovation of public housing apartments assigned to them and other families in need [85].

4.2. Reorganizing the Framework of Actors between the Public, the Private, the Inhabitants and the Third Sector

Forms of social agriculture that involve empowerment paths for fragile subjects require a careful review of the framework of the actors involved. In addition to the public entity and the third sector, the participation of private individuals can be equally decisive for strengthening the welfare system in conditions of scarcity of public resources and guaranteeing network stability at the same time [81]. Unfortunately, national and local regulatory frameworks do not always facilitate a transversal involvement of an increasingly articulated and complex actors’ framework, especially in the third sector [86]. Organizing a debate arena where subjects with different skills and spheres of action can collaborate and express their potential to the fullest, becomes an indispensable premise in such complex regeneration processes. It also responds to the need to identify a ‘pivot subject’ [87] capable of coordinating these actors within a vision that is as shared as possible and where spaces and their uses can be effectively questioned.

Furthermore, reorganizing the actors’ framework within a food network can be an opportunity to enhance skills that can give agriculture a new life; for example, by giving a new impetus to young and/or female entrepreneurship. Concerning the gender perspective, Tornaghi and Dahene (2019) [5,7,88], taking up the positions expressed by Nancy Fraser and Silvia Federici, underline the need to reaffirm a concept of ‘productive care’. It is a question of recognizing the (economic) value that activities related to food supply, children and elderly care at home, family management and the like have in the processes of social reproduction, or in the processes that are functional to the well-being of society [89]. Women’s contribution can be decisive in guaranteeing the maintenance of care practices linked to the land, its cultivation and the processing of its products in perpetuating knowledge and traditions that can support local productions. Supporting female entrepreneurship and work, as is being done in some Italian contexts [90], can contribute to a paradigm shift in the food system.

4.3. Reviewing the Regulatory Framework to Further Include Agriculture in the Urban Context and Encourage the Development of Skills and Planning

The lack of convergence between urban planning tools at the local level (primarily municipal) and territorial policies (for example, at the regional scale) once again exposes the difficulty of considering management strategies for the agricultural and food production sector—i.e., the so-called ‘food systems’—at the urban scale [91]. In Trieste, for example, the city’s general urban planning instrument (Regulatory Plan) does not allow to use urban land for agricultural purposes and this is precisely what has prevented the promoters of the Borgo San Sergio district project described above from accessing important regional funding sources for rural areas, funding that could have let the project itself grow.

What lies heavy on this is not only the sectorial nature of policies and instruments, which still do not consider forms of integration between rural and urban dimensions, but also the absence of an intermediate regulatory level that would allow to manage peri-urban areas through more flexible and inclusive projects [70]. In the peri-urban area, multi-sectorial and multilevel projects linked to agriculture and inserted in regeneration processes could find an adequately active dimension, as well as regulatory legitimacy and support—including economic support—without necessarily having to be the exclusive burden of the third sector. Fostering the development of farms and urban farms, for example, could help ensure network stability. To do this, however, it is necessary to release small local enterprises from the often too restrictive regulations imposed by the European Union, as some regions in Italy are trying to do to protect and enhance local production and small businesses [92,93].

There are, however, some signs that indicate greater attention to including the use of land for agricultural purposes even in urban contexts. This is the direction taken by the Measures for urban regeneration (March 2021), a national bill that aims to subsume the Green Deal guidelines into ordinary planning. Among others, there are measures for the agricultural conversion of land on which there are constructions that have not been used for more than 10 years (article 24), as well as the new ‘figure of the farmer guardian of the environment and the territory’ (article 25), tasked with supporting functional activities such as, for example, the arrangement and maintenance of agricultural soils, the protection of the agricultural and forest landscape or the care and maintenance of the hydraulic and hydrogeological systems.

In the NRPR, the National Recovery and Resilience Plan outlined in response to the pandemic crisis, on the other hand, Measure 2 proposes some lines of action aimed at developing a sustainable agrifood chain [94]. Our impression is, however, that the planned measures are concentrated more on the energy efficiency of facilities and equipment, less on the redesign of the relations between the agrifood system and the city. Greater attention to the ongoing experiences would rather invite us to push more on the redesign of systems by focusing, for example, on new forms of food service and consumption, also to recover “fragile” spaces with an agro-logical vocation through environmentally friendly cultivation techniques. Equally important would be to further support social inclusion through urban agriculture, as well as to seek new alliances between subjects for territorial enhancement through a network as stable and extensive as possible [78].

4.4. Hypothesizing a Territorial Development Project in Terms of Services and Equipment to Support the Resilient Transformation of Agro-Urban Landscapes

A final consideration should be dedicated to the opportunity that processes of food system rescaling and suburb regeneration offer us to rethink the relationships between built and open spaces through the design and organization of an innovative service frame between city and countryside [95] whose effects can extend to larger parts of the city, too. The frame figure refers to the designing of a light, continuous and flexible infrastructure, which, starting from the peri-urban areas, can infiltrate the city by exploiting public districts’ porosity. The main role of this infrastructure is to support the maintenance of urban and peri-urban forms of agriculture through fixed and mobile equipment that includes places of storage, processing, distribution, consumption, education, etc. At the same time, this seamless system made up of paths and open and built spaces in support of agrifood micro-chains can also respond to social and welfare needs if existing or planned welfare spaces are included in it. The frame is configured as a set of places in which more and less fragile subjects can find their chances for social cohesion and concrete opportunities to improve their health conditions.

This frame spreads over and reorganizes the open spaces, enhancing their potential as a multifunctional public web. Articulated in forms with different ecological gradients—obtained through planting, depaving strategies, water collection tanks, permeabilizations, etc.—[96], the frame supporting the food system territorialization processes can at the same time improve the resilience of urban spaces and guarantee accessibility to wider territories [97,98]. It is about rethinking the web of public open space and its relationship with the built environment in terms of complex ecological-social devices, through which to integrate social and environmental issues with new service management methods. In this perspective, the frame articulation acquires complexity through urban materials that enrich its equipment range: new “species of spaces”—for example, urban gardens, ecological corridors, playgrounds, and so on—respond to needs of health and movement, accessibility, comfort, and at the same time offer the opportunity to associate proactive dimension with soil care and maintenance practices based on the involvement of inhabitants or third parties.

5. Conclusions

Reterritorializing the food system through urban farming and social farming is a complex process. It requires articulated planning; it implies a renewal of policies, tools and action strategies; it entails full participation and constant commitment by all those involved.

The experiences and reflections performed in Trieste urge us to recognize the relationship between two operational levels as a critical node: the one aimed at building and maintaining the food network to support food cycle redesign and the one intended to reorganize the food space system within a territorially widespread infrastructure at the service of the suburbs and the city. Keeping these two planes in tension is not easy.

Building and maintaining such a network often involves changing established regulatory frameworks in an effort that individual operators cannot bear. For this reason, building alliances among different subjects to give the network visibility, for example through local labels, can allow actions that make it possible to undermine the rigidity of regulatory and administrative structures that are not always ready to welcome change. From this perspective, a nationwide network (Rete italiana politiche locali del cibo—Italian Network for Local Food Policies) that collects and shares experiences and projects to support the planning of sustainable territorial food systems should be taken as an important opportunity to enhance visibility and support initiatives even when locally circumscribed [99]. This step is accompanied by the need to work to build a fruitful dialogic relationship between institutional actors and civil society and to break the consolidated mistrust that, especially in public housing districts, people have towards the public entity. An equally fundamental node, which on the one hand calls for a mutual responsibility principle, on the other for the need for patient work to address the problems linked to forms of asymmetrical communication and even profound cognitive disparities that, in such widely shared decision-making processes, can make it difficult to share choices.

At the same time, it is necessary to make interests converge so that the interaction between the subjects involved in the network can generate participatory strategies of urban resilience that have concrete spatial repercussions [100]. Working for small projects, adaptively and incrementally, where resilience goals are combined to urban regeneration and social justice, as we are trying to do in the Orti di Massimiliano project in Trieste, appears to be a viable method to bring the food system back again to a local dimension starting from fragile contexts, such as those of the public city. These contexts, however, lend themselves to becoming a laboratory of experimentation where policies for the enhancement of agricultural production in the city, spatial transformation projects and practices of land care can converge with the goals of the Green Deal and, more generally, of food democracy.

Author Contributions

Sara Basso and Paola Di Biagi have developed Section 1; Sara Basso developed Section 2, Section 4 and Section 5; Valentina Crupi developed Section 3. Conceptualization, S.B., P.D.B.; methodology, S.B., P.D.B. and V.C.; software, V.C.; validation, S.B., P.D.B. and V.C.; formal analysis, S.B., V.C.; investigation, S.B., V.C.; resources, S.B., V.C.; data curation, S.B., V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B., P.D.B. and V.C.; writing—review and editing, S.B., P.D.B. and V.C.; visualization, V.C.; supervision, S.B.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, P.D.B., S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy, Università di Trieste, InterLand Consorzio per l’Integrazione e il lavoro. Cooperativa Sociale, Trieste, Italy, grant number 22 of the call for applications “HEaD Higher Education and Development” funded by Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia, on the POR FSE 2014–2020, Strand 3, Specific Plan 25/15, Regional Code FP1896212001”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the people who participated and made this project possible. Special thanks go to Dario Parisini and Mirko Pellegrini.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pothukuchi, K.; Kaufman, J.L. The Food System. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2000, 66, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. Feeding the city: The challenge of Urban Food Planning. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viljoen, A.; Schlesinger, J.; Bohn, K.; Drescher, A. Agriculture in Urban Planning and Spatial Design. In Cities and Agriculture. Developing Resilient Urban Food System; de Zeeuw, H., Drechsel, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 88–120. [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, A.; Wiskerke, H. (Eds.) Sustainable Food Planning: Evolving Theory and Practice; Wageningen University Press: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lohrberg, F.; Lička, L.; Scazzosi, L.; Timpe, A. (Eds.) Urban Agriculture Europe; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A Review of Experiences is in Carrot City. Designing for Urban Agriculture. Available online: https://www.ryerson.ca/carrotcity/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- HLPE. Food Security and Nutrition: Building a Global Narrative Towards 2030; High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Climate Change Adaptation in the Agriculture Sector; Europe EEA Report No 04/2019; EEA: København, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.; Sonnino, R. The urban foodscape: World cities and the new food equation. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedore, M. Just urban food systems: A new direction for food access and urban social justice. Geogr. Compass 2010, 4, 1418–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Food for the City. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fcit/fcit-home/en/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- WHO. Healthy Cities. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/urban-health/who-european-healthy-cities-network (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Sonnino, R.; Tegoni, C.L.S.; De Cunto, A. The challenge of food systemic food change: Insights from cities. Cities 2019, 85, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansero, E.; Pettenati, G.; Toldo, A. Il rapporto fra cibo e città e le politiche urbane del cibo: Uno spazio per la geografia? Boll. Della Soc. Geogr. Ital. 2017, 10, 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Pettenati, G.; Toldo, A. Il Cibo tra Azione Locale e Sistemi Globali; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Calori, A.; Magarini, A. (Eds.) Food and the Cities. Food Policies for Sustainable Cities; Edizioni Ambiente: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sonnino, R. The new geography of food security: Exploring the potential of urban food strategies. Geogr. J. 2014, 182, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C40 Cities. Available online: https://www.c40.org/networks/food_systems (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- The European Green Deal. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/agriculture-and-green-deal_it (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Un-Habitat. Cities and Pandemics: Towards a More Just, Green and Healthy Future; United Nations Human Settlements Program (UN-Habitat): Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Urban Food Systems and COVD-19: The Role of Cities and Local Governments in Responding to the Emergency; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altieri, M.A.; Nicholls, C.I. Agroecology and the reconstruction of a post-COVID-19 agriculture. J. Peasant. Stud. 2020, 47, 881–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, Farm to Fork Strategy. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/horizontal-topics/farm-fork-strategy_en (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Biodiversity Strategy for 2030. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/strategy/biodiversity-strategy-2030_en (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Marino, D.; Antonelli, M.; Fattibene, D.; Mazzocchi, G.; Tarra, S. Cibo, Città, Sostenibilità. Un Tema Strategico per L’Agenda 2030; ASVIS: Roma, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. FAO Framework for the Urban Food Agenda; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnaghi, A. Il Progetto Locale: Verso la Coscienza di Luogo; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N.; Katsikis, N. Operational landscapes. Hinterlands of the Capitalocene. AD 2020, 90, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K.; Marsden, T.; Murdoch, J. Worlds of Food. Place, Power, and Provenance in the Food Chain; Oxford University Press: Cry, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biagi, P. (Ed.) La Grande Ricostruzione; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, S.; Di Biagi, P. Gli ‘spazi del cibo’ per nuove abitabilità delle periferie urbane. Territorio 2016, 79, 17–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planes de Acción Territorial Huerta de Valencia. Available online: https://politicaterritorial.gva.es/es/web/planificacion-territorial-e-infraestructura-verde/pat-horta-de-valencia (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Donadieu, P. Campagnes Urbaines; Actes sud École Nationale Supérieure du Paysage de Versailles, Arles: Versailles, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mininni, M. Approssimazioni Alla città. Urbano, Rurale, Ecologia; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mininni, M. Dallo spazio agricolo alla campagna urbana. Urbanistica 2005, 128, 7–37. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll, R. Urban Agricolture. Il paesaggio degli orti urbani. Lotus Int. 2012, 149, 104–117. [Google Scholar]

- Territorial Landscape Plan of the Puglia Region (PPTR). Available online: https://pugliacon.regione.puglia.it/web/sit-puglia-paismi/struttura-del-pptr (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Ingersoll, R.; Fucci, B.; Sassatelli, M. Agricoltura Urbana. Dagli orti Spontanei all’Agricivismo per la Riqualificazione del Paesaggio Periurbano; Quaderni sul Paesaggio/02; Centro Stampa della Giunta Regione Emilia Romagna: Bologna, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cheema, G.S.; Smit, J.; Ratta, A.; Nasr, J. Urban Agriculture: Food Jobs and Sustainable Cities; United Nations Development Program (UNDP): New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- de Zeeuw, H.; Van Veenhuizen, R.; Dubbeling, M. The role of urban agriculture in building resilient cities in developing countries. J. Agric. Sci. 2011, 149, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zeeuw, H.; Drechsel, P. Cities and Agriculture. Developing Resilient Urban Food Systems Food and Agriculture; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot, L.J.A. Urban Agriculture: Definition, Presence, Potentials and Risks, and Policy Challenges; Cities Feeding People Series Report 31; International Development Research Centre (IDRC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot, L.J.A. Agropolis. The Social, Political, and Environmental Dimensions of Urban Agriculture; International Development Research Centre (IDRC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mougeot, L.J.A. Growing Better Cities: Urban Agriculture for Sustainable Development; International Development Research Centre (IDRC): Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- In Italy, Exemplary is the Experience of Some Cities such as Turin, OrtiAlti. Available online: https://ortialti.com/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Ortipertutti, Comune di Bologna. Available online: https://www.fondazioneinTecnologiaurbana.it/2-urbancenter/menulateral/1241-03-ortipertutti-nuovi-orti-a-bologna (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Lefebvre, H. Le droit à la ville. L’Homme Société 1967, 6, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Officina Welfare space (Ed.) Spazi del Welfare. Esperienze, Luoghi, Pratiche; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Secchi, B. La Città del XX Secolo; Laterza: Roma, Italy; Bari, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarisse, C. Cuisine, Recettes D’architecture; Les Éditions de L’imprimeur: Besançon, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, S. Food and Urbanism: The Convivial City and a Sustainable Future; Bloomsbury Academic: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biagi, P. Cibo, spazi, corpi. Spunti per una riflessione sull’abitare quotidiano nella città pubblica, e oltre. Territorio 2016, 79, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018. Building Climate Resilience for Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodotà, S. Il Diritto al Cibo; RCS MediaGroup, S.p.A.: Milano, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daconto, L. Città e Accessibilità alle Risorse Alimentari; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Detroit Strategic Future Plan. Available online: https://drestefuturecity.com/strategic-framework/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Marino, D. (Ed.) Agricoltura Urbana e Filiere Corte: Un Quadro Della Realtà Italiana; Franco Angeli: Roma, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw, E.; Simos, J. Healthy Cities: The Theory, Policy, and Practice of Value-Based Urban Planning; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dorato, E. Preventive Urbanism. The Role of Health in Designing Active Cities; Quodlibet Studio: Macerata, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, S.; Marchigiani, E. Accessibile non è solo barrier-free. Per una città proattiva, palestra di salute e inclusione. In L’Urbanistica Italiana di Fronte all’Agenda 2030. Portare Territori e Comunità Sulla Strada Della Sostenibilità e Della Resilienza, Proceedings of XXII Conferenza Nazionale SIU, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2020; Planum Publisher: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cibic, A. Rethinking Happiness. Fai Agli Altri Quello che Vorresti Fosse Fatto a te. Nuove Realtà per Nuovi Modi di Vivere/ Do unto Others as You Would Have Them do Unto You. New Realities for Changing Lifestyles; Corraini: Mantova, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Steel, C. Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives; Vintage: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Haney, D.H. When Modern was Green: Life and Work of Landscape Architect Leberecht Migge; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parham, S. Food and the garden city. Territorio 2020, 95, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadieu, P. Dall’utopia alla realtà delle campagne urbane. Urbanistica 2005, 128, 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, M. Abitare Territori Intermedi. Declinare Urbanità per Riconoscere Nuove Forme di città. Esplorazioni nel Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Trieste, Trieste, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparrini, C.; Terracciano, A. (Eds.) Dross City. Metabolismo Urbano, Resilienza e Progetto di Riciclo dei Drosscape; List: Trento, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen, A.; Bohn, K.; Howe, J. Continuous productive urban landscapes; Routledge, Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grulois, G.; Tosi, M.C.; Crosas, C. (Eds.) Designing Territorial Metabolism. Barcelona, Brussels, and Venice; Jovis: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mininni, M. MateraLucania2017. Laboratorio Città Paesaggio; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- LaboratorioCittàPubblica, Eds. Città pubbliche. Linee Guida per la Riqualificazione Urbana; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biagi, P.; Marchigiani, E.; Marin, A. (Eds.) Trieste ’900. Edilizia Sociale, Urbanistica, Architettura: Un Secolo Dalla Fondazione dell’Ater; Silvana Editoriale: Cinisello Balsamo, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biagi, P.; Marchigiani, E.; Marin, A. (Eds.) La Città Della Ricostruzione: Urbanistica, Edilizia Sociale e Industria a Trieste, 1945–1957; Comune di Trieste: Trieste, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Di Biagi, P. Abitare sociale e comunità: Borgo San Sergio a Trieste. In Ernesto Nathan Rogers 1909–1969; Baglione, C., Ed.; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2012; pp. 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Habitat Microaree. Available online: http://habitatmicroaree.comune.trieste.it/il-progetto/ (accessed on 27 January 2022).

- InterLand. Consorzio per L’integrazione e il Lavoro. Cooperativa sociale. Available online: https://www.interlandconsorzio.com/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Orti di Massimiliano. Available online: http://www.ortidimassimiliano.it/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Crupi, V. Progetto HEaD Higher Education and Development. Per un Modello Innovativo di Agricoltura Urbana; Research Report; Università degli Studi di Trieste: Trieste, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, S. Rethinking public space through food processes: Research proposal for a “public city”. Urban Izziv 2018, 29, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. From ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ multifunctionality: Conceptualising farm-level multifunctional transitional pathways. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iacovo, F. L’agricoltura sociale in Italia e in Europa: Modelli a confronto e scenari. In La vera Agricoltura Sociale fa bene all’Italia. 1° Rapporto Coldiretti Sull’agricoltura Sociale; DigitaliaLab, Fondazione Campagna Amica: Coldiretti, Italy, 2020; pp. 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco, L. Il Welfare Locale. Processi e Prospettive; Carocci: Roma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Caravaggi, L.; Imbroglini, C. Paesaggi Socialmente Utili. Accoglienza e Assistenza Come Dispositivi di Progetto e Trasformazione Urbana; Quodlibet: Macerata, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cognetti, F.; Padovani, L. Perché (Ancora) i Quartieri Pubblici. Un Laboratorio di Politiche per la Casa; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fondazione Cariplo, Programma QuBi La Ricetta Contro la Povertà Infantile. ‘Oltre il cibo’. Available online: https://ricettaqubi.it/portfolio-articoli/oltre-il-cibo/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Maino, F.; Maurizio, F. Nuove Alleanze per un Welfare che Cambia. Quarto Rapporto sul Secondo Welfare in Italia; Giappichelli Editori: Milano, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Iaione, C. Il Governo Condiviso dei beni Comuni per un Welfare Urbano. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/PDS3/allegati/il%20governo%20condiviso%20dei%20beni%20comuni.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Tornaghi, C.; Dehaene, M. The prefigurative power of urban political agroecology: Rethinking the urbanisms of agroecological transitions for food system transformation. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2019, 44, 594–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tronto, J. Moral Boundaries. A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Creditagri—Progetto Donne. Available online: https://www.coldiretti.it/servizio/donne-in-agricoltura (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Lazzarini, L. Urbanistica e sistemi alimentari locali: Una riflessione sull’architettura del divario. In L’urbanistica Italiana di Fronte All’agenda 2030 per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile, Proceedings of XXI Conferenza Nazionale SIU, Matera-Bari, Italy, 5–7 Giugno 2019; Planum Publisher: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Friuli Venezia Giulia Region, Piccole Produzioni Locali. Available online: http://ppl.regione.fvg.it (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Veneto Region, Piccole Produzioni Locali Veneto. Available online: https://www.pplveneto.it (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- National Recovery and Resilience Plan. Available online: https://www.governo.it/sites/governo.it/files/PNRR.pdf (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Basso, S.; Marchigiani, E. Attrezzare piccoli e medi centri urbani. Pianificazione in Friuli Venezia Giulia. Territorio 2019, 90, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- For Example, See the Work Done by the Dreiseitlconsulting Studio. Available online: https://www.dreiseitlconsulting.com/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Caravaggi, L.; Carpenzano, O. Roma in Movimento. Pontili per Collegare Territori Sconnessi; Quodlibet: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, S.; Marchigiani, E. Questioni di accessibilità: Gli standard per un progetto di formazioni urbane più sane e inclusive. In Diritti in Città; Laboratorio Standard Eds.; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2021; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rete Italiana Politiche Locali del Cibo. Available online: https://www.politichelocalicibo.it/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

- Atelier d’Architecture Autogérée. Public Works. R-urban ACT. Une Stratégie Participative de Résilience Urbaine; aaa/peprav. 2015. Available online: http://r-urban.net/press/ (accessed on 5 December 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).