Abstract

The emerging problems of plastic pollution and the mismanagement of plastic waste highlight the need to find a solution that involves adopting a systematic perspective. Capacity development is recognized as an approach that can tackle these problems on a global scale and improve the performance of waste management systems. This paper focuses on the educational and training aspects of capacity development by evaluating available teaching materials and their content regarding training topics and stakeholders. The methodology used for the evaluation of teaching materials was the weighting score method, which provided information about previously defined training topics and the extent to which they were present in the material. The results of the evaluation can be beneficial for all stakeholders involved in plastic waste management, organizations that are actively included in designing and publishing such materials, and groups who are focused on capacity development. The results of the evaluation are structured in such a way to provide easy access to certain material depending on t desired training topic or targeted stakeholder. Thus, the results of the evaluation can be used either directly in the training processes or indirectly as a baseline for the preparation of new teaching materials. The study also contributes to theory by analyzing stakeholders in plastic waste management and defining essential training topics. Moreover, the study has potential to be the benchmark for future research projects in the area of education for plastic waste management.

1. Introduction

Development assistance is recognized as an important tool for the achievement of development goals. These goals can be part of the local agenda, such as creating a more efficient local government, or they can be global, such as improving living conditions on the global scale [1]. Furthermore, goals can be set to improve natural ecosystems and address pollution problems. One of the emerging global issues that requires a systematical approach is plastic pollution; it represents a global threat and affects nearly every marine and freshwater ecosystem in the world. Many countries are struggling to handle the current volume of plastic waste and ongoing plastic pollution. Humanity produces nearly 300 million metric tons of plastic waste every year [2]. Previous studies estimate that nearly 8 million metric tons of macroplastic and 1.5 million metric tons of microplastic end up in the ocean every year [3]. Moreover, it has been estimated that even with a strong commitment from governments to reduce plastic emissions, the amount of ocean plastic pollution may reach 53 million metric tons per year by 2030 [4]. Capacity development (CD) is recognized as an approach that can address the plastic pollution problem by strengthening the capacity of plastic waste management systems.

Different definitions of CD have been proposed: ‘’for some CD is an approach or process of solving a certain problem (example poverty) while others see it as a development objective (example development of individual or organizational capacity)‘’ [5]. CD can be seen more widely as a group of strategies, approaches, and methods used by developing countries or external stakeholders for the improvement of individual, sector, network, and system performance [6].

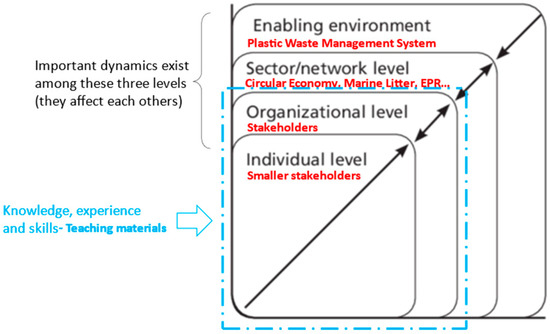

The CD framework varies from one case to another; therefore, its exact definition depends on the organization or the country in which capacity is built and the context in which development occurs [7]. CD frameworks consist of different levels; the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA) proposes a framework with four levels of capacity [5]:

- The enabling environment—This is the level of CD where development takes place. It encompasses a wide range of activities that are tightly connected with other CD levels (Figure 1) [8];

Figure 1. CD framework in the context of PWM (blue lines indicate at which level training takes place).

Figure 1. CD framework in the context of PWM (blue lines indicate at which level training takes place). - Network or Sectoral levels—At the network or sectoral level, the main focus is on sets of policies and strategies. Initiatives at this level can accelerate CD and promote better sector and cross-sector coordination; therefore, this level is interesting for investors and donors [6];

- Organizational level—This level focuses on organizational strengthening, addressing the management of processes and resources. This is the level where investors and donors enter CD with technical assistance or/and financial support [9]. Thus, this is the level where teaching and training materials are actively involved in development assistance, as is shown in Figure 1 [10];

- Individual level—At this level, the abilities of the stakeholders are strengthened through formal training and education or by learning through experience [8]. The development at this level should be synchronized with the other CD levels; if the investment is focused mainly on the individual level, then there is a risk of limiting development at the other levels [11].

Questions such as ‘’whose capacity is to be grown and for what purpose’’ define the orientation and the objectives of CD.

The CIDA [5] underlines three CD objectives:

- The improvement or more effective utilization of skills, abilities, and resources;

- Strengthening understanding and relationships;

- Addressing issues of values, attitudes, motivations, and conditions for sustainable development.

These objectives are adjusted to the context of the development. For example, in the context of plastic waste management (PWM), the objectives would be increasing collection and recycling rates, preventing plastic waste leakage into natural environments, reducing the use of single use plastic, etc. The aforementioned objectives can be achieved if the efficiency of the stakeholders is previously improved through the strengthening of their relationships with other stakeholders by influencing their attitudes, values, and motivations with proper training and education.

There are several most-common approaches for the implementation of CD, which can be applied in many different situations. Some of them are financial and physical support (recognizes the lack of resources as the main cause of lack of capacity), support for the improvement of the organizational and technical capabilities (improves the existing technical and organizational abilities with activities, such as technical assistance, training, and the improvement of working conditions), helping to define clear strategic directions (the organization is not able to define the direction of development due to some internal reasons, solution—policy dialog), support for the innovations and provision of opportunities for learning (provides chances to experiment and learn without thoughts of failure, intervention, or negative reactions). Furthermore, support for strengthening the complex organizational system (the approach frames the capacity development issue in a systemic perspective), support for the establishment of an enabling environment (when the enabling environment is failing to support the development of sustainable capacity, solution-based improvements of institutions, and socio-political frameworks that can shape CD) and the creation of performance initiatives and pressures (redesigning the organization, breaking up public-sector monopolies, enhancing competition, adjusting initiative structure, and making information about performance more accessible to citizens).

The choice of the most appropriate approaches and measures depends on the particular situation in which they will be applied. For this, the questions that should be asked are: “to what end we need to develop certain capacity, what will be the purpose, whose capacity needs to be developed, what kind of capacity needs to be developed to achieve wider CD objectives?” [12].

To analyze teaching and training materials for PWM, a stakeholder analysis is required that includes their roles in the PWM value chain and their training needs. CD in this context engages the above-mentioned approaches—support with financial and technical resources and the improvement of the organizational and technical capabilities, innovations, and provision of opportunities for learning [13].

The objective of this paper is to evaluate available teaching materials for plastic waste management in terms of their content and targeted stakeholders. The results provide an overview and easy access to the teaching materials depending on training topic and stakeholder. Furthermore, the results of the evaluation can the increase utilization of training and education, which are recognized as important approaches in capacity development [14], by simplifying the use of its essential tool—teaching materials. In addition to capacity development, the results of the evaluation can be useful for all stakeholders interested in increasing performances of plastic waste management, such as universities, experts, small- and big-scale businesses, and society in general.

2. Materials and Methods

The baseline of the research was the answer to the following questions—“Whose capacity is to be developed and how?” (In this particular case, the results of the research are to be used by essential stakeholders in PWM. Thus, it was necessary to analyze who these stakeholders are and what their training and educational needs are. Afterwards, the training materials were collected, grouped by stakeholder, and evaluated.

The methodology that derived the results is divided into 5 steps:

- Stakeholder analysis;

- Definition of essential training topics;

- Collection of teaching materials;

- Classification of materials by target group;

- Evaluation of materials with weighting score method.

The 6 essential groups of stakeholders in PWM have been pointed out:

- Manufacturers;

- Government;

- Waste managers;

- Consumers;

- Producer Responsibility Organizations (PROs);

- Informal sector.

What makes these 6 stakeholders crucial factors in PWM is their capacity to not just impact the waste management system with their performances, but also the performance of other stakeholders [15].

Manufacturers—Plastic product manufacturers mold, cast, and assemble products made of different types of polymers for various markets, from the car industry to food packaging and other sectors. Manufacturers have the responsibility to follow standards and regulations to avoid environment pollution during production, and later, during the product’s usage [16].

Government—The role of the national government is to define a legal framework for plastic waste management, while the local government (municipality) is entrusted with the task of waste management services (collection and treatment). However, the responsibility, in some cases, can be shifted to other stakeholders, such as PROs or private waste management companies [17].

Waste managers—Crucial stakeholders in PWM are the operators and managers responsible for the collection, sorting, and recycling of plastic waste. Waste managers work to maintain waste management as efficiently as possible and ensure that all activities comply with laws and regulations. Waste managers can be employed by waste management companies under the control of the local government or by private waste management companies [18].

Consumers—Consumers can be regarded as stakeholders who generate plastic waste with a central role in the PWM chain. A responsible and educated consumer can significantly contribute to an efficient waste management by supporting the prevention and re-use of plastic waste and separation at the source. By applying these principles, consumers contribute to more efficient waste collection and processing. Community-based organizations (CBOs) are also recognized as a part of consumers, due to their social status and activities in society. CBOs can have an important role in communication between the community (consumers), authorities, and the market.

Producer responsibility organizations (PROs)—extended producer responsibility (EPR) is an environmental policy approach in which the producer responsibility for a commercialized product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle [19]. EPR schemes typically allow producers to shift their responsibility for collection and recycling to a third party, a so-called producer responsibility organization, which is paid by the producers for end-of-life product management. Moreover, all the environmental costs of the product and the costs of end-of-life product management are added to the product market price [20].

Informal sector—Informal waste pickers are collectors of secondary materials from municipal and industrial waste streams which are suitable for re-use and recycling. Informal waste pickers are involved in activities such as the collection, sorting, trading, and sometimes even processing of waste materials. This can lead to increasing the financial income of the informal sector, but also to the recovery of a remarkable share of municipal waste in countries in which the informal sector has a prominent role [21]. Waste pickers can be regarded as a sensitive social group because, for many of the poorest people around the globe, waste picking represents the only source of financial income [22].

Based on stakeholder’s roles in the PWM value chain, as taken from the literature, the training needs and training topics have been defined. 8 training topics have been identified:

- Regulations;

- Collection;

- Sorting;

- Recycling;

- Recyclability;

- Occupational health and safety;

- Awareness raising;

- Economic aspect.

Regulations—Regulations are essential for the establishment of successful and efficient waste management, defining the roles, obligations, and responsibilities of different actors in PWM [23]. Moreover, regulations influence other training topics in a direct or indirect way. Legislation also defines quality standards in plastic production; therefore, it can influence the way that the plastic products, and later, plastic waste will affect public and environmental health [24]. In Table 1, the training needs of different stakeholders in the context of establishing or following the legal requirements are presented.

Table 1.

Specific training needs for different stakeholders in the context of regulations.

Collection—Waste collection is a multidimensional topic, covering management and operation processes, information delivery, fulfilling collection targets, and economic feasibility [25]. In Table 2, the training needs for waste collection in the context of different stakeholders are presented. Importantly, it should be noted that separation at the source is also included with collection (grouping waste by different waste streams—plastic, paper, glass, etc.) to simplify the classification of training topics.

Table 2.

Specific training needs for different stakeholders in the context of waste collection.

Sorting—Sorting is a process in the PWM value chain that has huge importance for effective recycling [27]. Sorting operations derive materials which fulfil quality standards for recycling. In this process, in addition to quality, the goal is to sort materials by polymer types (PP, HDPE, PET, etc.). The process of sorting takes place in treatment facilities and includes manual labor and automatized techniques. In Table 3, the training needs regarding sorting for waste managers, the informal sector, and PROs are shown.

Table 3.

Specific training needs for different stakeholders in the context of waste sorting.

Recycling—Recycling is an essential phase of PWM because, in this phase, waste is converted into new materials or products [28]. Furthermore, energy recovery from plastic waste management is included in the recycling training topic. This is completed with the intention to simplify training topic classifications, since energy recovery from waste includes a mix of waste streams and not just plastic waste. Recycling, for different stakeholders, has different aspects; see Table 4.

Table 4.

Specific training needs for different stakeholders in the context of recycling.

Recyclability—Designing products for recyclability is driven by environmental and economic goals. Moreover, recyclability can be designed into products by choosing materials and modularity [29]. Therefore, eco-design plays a crucial role in the manufacturing of products that will be easier to manage in post-treatment (sorting and recycling). Manufacturers are especially interested in this training topic because of their role in the PWM value chain. They require guidance on the design of plastic products which will increase the recyclability of the product and reduce the negative impact on the environment. Guidance for eco-design includes chemical aspects of product composition and recommendations for different types of materials for various products. Moreover, this training topic should include recommendations and guidance for the design of supplemental items for products, such as plastic films for labels, closures, and other small parts.

Occupational Health and Safety—Occupational Health and Safety (OHAS) is a crucial training topic for the protection of human health and life. It includes a set of measures and recommendations which tend to keep participants in PWM safe from risks that are present in their job [30]. In addition to recommendations, this training topic should provide information about risks to locate and point out possible accident situations. The OHAS training topic should cover the training needs of the workers involved in plastic manufacturing, waste management operators engaged in the field and at a treatment facility, and informal waste pickers by providing technical guidance and recommendations for activities in which they are involved. Additionally, this topic should cover the management aspect in such way that will provide the people who are in charge of OHAS management with tools to help them recognize risk in their organization and facility. Manufacturers, waste managers, and the informal sector are recognized as three stakeholders who have interest in this training topic, and their needs are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Specific training needs for different stakeholders in the context of OHAS.

Awareness raising—Public awareness about the importance of recycling, avoiding single-use plastic products, and proper plastic waste management are important for the achievement of environmental goals (no plastic leakage into marine environments, resource prevention, etc.). The consumers are targeted as stakeholders that should be educated about these topics because, in case of knowledge and positive attitude, they can significantly contribute to sustainable waste management [31].

Economic aspect—The economic aspect as a training topic addresses the financial aspects of waste management operations (collection, sorting, and recycling), cost calculations, feasibility assessment, and tools for cost optimization [32]. These elements have significant value for waste managers, and they can help them to increase revenue and minimize costs. Furthermore, PROs also have interest in this topic due to the economic aspect of EPR scheme management, as do governments, due to the economic part of waste management (such as fees, taxes. etc.) [20].

During the process of the materials collection, a total of 128 different materials were collected and processed. From the 128 collected materials, only 51 qualified for final evaluation. More than half did not pass the preliminary evaluation, mostly due to insufficient content related to PWM. Out of these 51 materials:

- A total of 11 of them target policy and decision makers. In most cases, these materials address regulations as a training topic and give support to the establishment of legal frames for PWM. Therefore, they are classified as materials that target government and policy makers in general;

- Additionally, 12 training materials address the production of plastic products and recognize regulations and recyclability as their main training priorities. These are classified as teaching materials for manufacturers;

- Teaching materials for consumers aim to spread awareness regarding issues that arise from plastic waste mismanagement and offer information for the separation of waste at the sources. In total, 10 of these are identified. They target almost all spheres of society, from large-scale groups, such as the younger population and students, to specific groups such as communities in coastal areas;

- Teaching materials that address the training of people and organizations in charge of managing waste are classified as materials for waste managers. In total, 10 of these are identified. Collection, sorting, recycling, and OHAS are the main topics of these publications. Additionally, the economic aspect of waste management and regulation guidance can be a significant part of the content;

- Five teaching materials discuss the extended producer responsibility (EPR), which makes them usable for PROs. Their content offers guidance for the establishment the EPR scheme (collection, sorting, and recycling) and advice for fulfilling legal requirements. Furthermore, some materials have an economic aspect included, for example, management costs;

- The availability of materials that target informal waste pickers was limited. Therefore, only three were evaluated in this research. The topics discussed in these publications are collection, sorting, and OHAS.

A major constraint in the research was the availability of ‘’free’’ materials. Many private companies and organizations, which are professionally involved in the design and creation of teaching content for PWM, are not willing share them, or are, but not for free. This fact turned the search for materials towards the relevant international and local organizations and institutions who offer these materials for free. Among these organizations are the World Bank, United Nations (UN), International Labor Organization (ILO), Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), World Health Organization (WHO), European Union, and many others.

Since different stakeholders have different training priorities it is understandable that it is impossible to have a one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to teaching materials. To approach the evaluation of multidimensional features of teaching materials and to apply a prioritization of them depending on stakeholders, the weighting score method (WSM) was used in this study. WSM is a prioritization framework that allows for making decisions based on how to arrange features in situations when there are several alternatives to evaluate. WSM is based on the principle that features are scored according to a set of criteria which is prioritized and then ranked by their final scores. The goal of WSM is to give an objective and quantitative value for each object of evaluation [33]. Moreover, the possibility to provide quantitative information on the content of the teaching materials was an additional motivation for choosing WSM. This dimension of the method provides the answer to the important question—to what extent is the certain training topic present in the material? The structure is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Structure of WSM.

Part of the structure are nine criteria introduced for evaluation. Eight criteria are the previously defined training topics, and one additional criterion is the presence of illustrative content (graphical presentations—multimedia, PowerPoint presentations, etc.) that tend to simplify knowledge and derive it in a creative way. The weighting of criteria is based on the training priorities of each stakeholder. Weight 1 is given when the importance of a certain criterion (training topic) for a specific stakeholder is low. Weight 3 applies when the criteria are not crucial for the training interests of stakeholders, but are beneficial for the learning experience. Finally, weight 5 is given for criteria that have essential importance for a stakeholder. However, the weight is modified from one stakeholder to another; for example, the criterion of ‘’collection’’ will have a different value for two different stakeholders. This is also the case for manufacturers of plastic products who do not have an interest in waste collection, and waste managers for whom waste collection is one of the essential topics. In this case, the weight of collection for manufacturers will be 1 and for waste managers 5.

The weights of criteria depending on each stakeholder are shown in Table 7. It is important to notice that graphical presentation has weight 5, regardless of the stakeholder, due to the positive impact on the learning outcome.

Table 7.

Weights of criteria depending on stakeholders training priorities.

Once the weighting of criteria for each stakeholder was defined, the teaching material was evaluated with WSM.

An example of scoring with WSM is presented with Equation (1):

∑Score ∗ Weight = Number of points that materials received

During the process of evaluation, the score (depending on the presence of the topic in the material) is multiplied by the weight of the criterion, and this is done for each criterion. Finally, these values were added and each training material obtained a quantitative value. Based on this result, teaching materials were listed from the lowest to the highest value. In Table 8, an example of the evaluation process for one teaching material developed for manufacturers is presented (Eco-Design of Plastic Packaging). This process is conducted among all teaching materials for every stakeholder.

Table 8.

Example of evaluation of teaching material with WSM.

3. Results

In order to simplify the visual presentation of the results, scores (2, 1, and 0) are replaced in the tables with colored symbols. Green stands for score 2 (content is present, and it includes all relevant parts of the topic), yellow for 1 (content is present but does not include all relevant parts of the topic), and white for 0 (no content related to the topic).

3.1. Manufactures

Teaching materials and their content in terms of training topics for manufacturers of plastic product are presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Teaching materials for manufacturers.

3.2. Government

In Table 10 teaching materials for decision makers and different levels of government are presented.

Table 10.

Teaching materials for government.

3.3. Waste Managers

Teaching material designed for waste managers are presented in Table 11.

Table 11.

Teaching materials for waste managers.

3.4. Consumers

Teaching materials for consumers and their content are presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Teaching materials for consumers.

3.5. PROs

Teaching materials designed for PRO’s are presented in Table 13.

Table 13.

Teaching materials for PROs.

3.6. Informal Sector

Teaching materials for informal sector are presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

Teaching materials for informal sector.

4. Discussion

4.1. Methodology

Although the WSM is commonly used for the prioritization of actions in projects, ranking strategic initiatives against benefits and cost categories, or choosing the best item, it was found to be very useful for this research due to the possibility of deriving subjective, quantitative information on the content of the materials. Alternatively, or as a next step, the evaluation could be conducted based on expert interviews of stakeholders in the PWM value chain. In this work, we evaluate the materials in a subjective way based on a review of the literature. The same holds true for the definition of the stakeholders needs; in this case, experts in the field of waste management could be consulted instead of the literature. When it comes to the criteria of evaluation, additional criteria can be added, extending the scope of research and providing more information on materials. This could address additional training topics, such as plastics from e-waste, biodegradable plastics, marine debris, specific aspects of EPR, circular economy aspects, and others.

4.2. Representation of Results

The majority of materials are accessible in a PDF format. Many of them are supported with a graphical presentation of teaching content, which significantly influences their efficiency when it comes to the transfer of knowledge. In addition to written presentations, there is content available in the form of video guidance and lectures. Almost all teaching materials under the scope of this research are written and presented in English (48), except for a few of them, which are in Spanish (two) and Italian (one). However, some of them are published by the European Union (EU), and therefore, are available in all official languages of the EU.

An important note regarding the results of the evaluation and the format in which they are presented is that ranking the teaching materials as a sum of points does not mean that a certain material is the best or better than others. Rather, the ranking format is pointing out the materials that cover most of the previously defined training topics in plastic waste management. This evaluation approach provided quantitative information about the extent to which certain training topics are present; this is visible in the Tables, where each training topic has a numerical value (0, 1, or 2). In terms of material types, they can be dominantly found in written forms (PDF). However, some of them are in the form of video lectures (GIZ Webinar for E-waste Plastic Recyclers, 2019) or a combination of these two formats (video material as supplementary content to written) (Trash Academy, 2018). The results of the research can be used as a baseline for training and education activities because they provide easy access to training materials depending on interest in a certain training topic or class of stakeholder. It can be used as a part of small-scale training projects in waste management, covering topics such as waste collection and sorting. On the other hand, the results can be beneficial for large-scale projects in terms of the development of the capacity of a developing country or organization. A recommendation for the use of these materials is to combine more of them when there is an interest in a certain topic; this should offer a wider scope of information on the topic. The reason for this is the fact that training topics are covered to different extents in each of the evaluated training materials. Moreover, the materials are very suitable to be used for the creation of new teaching materials because they summarize all relevant parts of plastic waste management.

5. Conclusions

The study addresses an important issue—plastic waste mismanagement—and offers a solution through education and training. Training and education play important roles in the development of individuals, organizations, regions, and society in general. Therefore, they are recognized as important elements for the success of sustainable waste management. This can be explained by the fact that education, as with training, has the great potential to change people’s attitudes toward plastic waste problems by improving their knowledge. Moreover, education in CD has an important role because the objectives of CD can be achieved if the efficiency of the stakeholders is previously improved through strengthening their relationships with other stakeholders by influencing their attitudes, values, and motivations with proper training and education.

This research reviewed the available teaching materials for plastic waste management in the context of their content. The content was evaluated in terms of the training needs of stakeholders, which were defined beforehand, based on the literature. The evaluated training and teaching materials have been provided by relevant national and international institutions who have experience in producing educative content for waste management. WSM was chosen for evaluation due to the possibility of acquiring quantitative information on content.

The results of the evaluation provide easy access to teaching materials depending on desired training topic or targeted stakeholder to all interested parties in plastic waste management. Furthermore, the results provide information about the extent to which the training topic is present in a given material.

During the research process, the collection, and the evaluation of materials, no similar research was noticed, which opens a space for improvement in this area—namely, training materials, training methods, and their compatibility. Furthermore, this fact points out the value of the study and its contribution to theory and practice. Regarding the contribution to theory, this study can be seen as benchmark for future research projects in the area of education for plastic waste management; the reasons for such claims can be found in the stakeholder analysis which was made and the definition of the essential training needs of the stakeholders. The contribution to practice consists in fact that the study simplifies the usage of training materials by providing information about content and targeted groups.

The further development of research can go in few directions. Some of the possibilities are:

- The inclusion of plastic from E-waste. E-waste is, today, the fastest growing waste stream in the world, with an annual growth rate of 3–4% and a share of plastic in e-waste accounting for almost 20% [84];

- The inclusion of biodegradable plastic or even other waste streams such as paper, glass, or bio-waste;

- The development of a database for the evaluated materials with a user-friendly interface which will provide not only experts but also all other people who are interested in topic of waste management with easy access to materials;

- The further development of the methodology and the inclusion of new criteria will provide more detailed information about materials’ content and cover topics which are not covered in this research.

The combined use of evaluated teaching materials is recommended; this approach will provide wider range of information about the required training topic or stakeholder.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S. (Slobodan Stojic) and S.S. (Stefan Salhofer); methodology, S.S. (Slobodan Stojic); assessment, S.S. (Slobodan Stojic); writing—original draft preparation, S.S. (Slobodan Stojic); writing—review and editing, S.S. (Slobodan Stojic) and S.S. (Stefan Salhofer); supervision S.S. (Stefan Salhofer). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Evaluated teaching materials are available on pwmteachingmaterials.com (accessed on 11 February 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sachs, J. The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time; The Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; ISBN 1-59420-045-9. [Google Scholar]

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Woerden, F. Van What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050e; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, W.W.Y.; Shiran, Y.; Bailey, R.M.; Cook, E.; Stuchtey, M.R.; Koskella, J.; Velis, C.A.; Godfrey, L.; Boucher, J.; Murphy, M.B.; et al. Evaluating scenarios toward zero plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1455–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelle, S.B.; Ringma, J.; Law, K.L.; Monnahan, C.C.; Lebreton, L.; Mcgivern, A.; Murphy, E.; Jambeck, J.; Leonard, G.H.; Hilleary, M.A.; et al. Predicted growth in plastic waste exceeds efforts to mitigate plastic pollution. Science 2020, 369, 1515–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, J. Capacity Development: Why, What and How; Canadian International Development Agency: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2000.

- Austrian Development Agency. Manual Capacity Development: Guidelines for Implementing Strategic Approaches and Methods in ADC; Austrian Development Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ubels, J.; Acquaye-Baddoo, N.-A.; Fowler, A. Capacity Development in Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781844077427. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Capacity Development Practice Note; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNDESA. Report of the Capacity Building Workshop and Expert Group Meeting on Integrated Approaches to Sustainable Development Planning and Implementation; UNDESA: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, J. Training and Beyond: Seeking Better Practices for Capacity Development; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alaerts, G.; Maarten, B.; Hare, M.; Kaspersma, J. Capacity Development for Improved Water Management; CRC Press: Delft, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wignaraja, K. Capacity Development: A UNDP Primer; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, J.A.; Agamuthu, P. Universities in capacity building in sustainable development: Focus on solid waste management and technology. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2007, 25, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Virji, H.; Padgham, J.; Seipt, C. Capacity building to support knowledge systems for resilient development—Approaches, actions, and needs. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ODA. Guidance Note on How to Do Stakeholder Analysis of Aid Projects and Programmes; ODA: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, E.; Romagnoli, V.; Kirhensteine, I.; Ruckley, F.; Kreißig, J.; Mitsios, A.; Pantzar, M. Support to the Circular Plastics Alliance in Establishing a Work Plan to Develop Guidelines and Standards on Design for Recycling of Plastic Products; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, K. Stakeholder participation for sustainable waste management. Habitat Int. 2006, 30, 863–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, G. Waste Management Practice: Literature Review; Dalhousie University: Halifax, NS, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Extended Producer Responsibility Updated Guidance for Efficient Waste Management; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Draft Practical Manuals on Extended Producer Responsibility and on Financing Systems for Environmentally Sound Management; UNEP: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gerdes, P.; Gunsilius, E. The Waste Experts: Enabling Conditions for Informal Sector Integration in Solid Waste Management:Lessons Learned from Brazil, Egypt and India; GTZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ILO; WIEGO. Cooperation among Workers in the Informal Economy: A Focus on Home-Based Workers and Waste Pickers; PRODOC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shahnawaz, M.; Sangale, M.; Ade, A. Policy and Legislation/Regulations of Plastic Waste Around the Globe; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Alabi, O.; Ologbonjaye, K.; Awosolu, O.; Alalade, O. Public and Environmental Health Effects of Plastic Wastes Disposal: A Review. Toxicol. Risk Assess. 2019, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, A.; Martinho, G.; Rodrigues, S.; Gomes, M. Sustainable Solid Waste Collection and Management; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-93199-9. [Google Scholar]

- Snel, M.; Ali, M. Stakeholder Analysis in Local Solid Waste Management Schemes; WELL: Leicestershire, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ruj, B.; Pandey, V.; Jash, P.; Srivastava, V.K. Sorting of plastic waste for effective recycling. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. Res. 2015, 4, 564–571. [Google Scholar]

- Shent, H.; Pugh, R.; Forssberg, E. A review of plastics waste recycling and the flotation of plastics. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 1999, 25, 85–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Patel, D.; Morkos, B. Development of Product Recyclability Index Utilizing Design for Assembly and Disassembly Principles. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2018, 140, 031015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, Y.R. Waste Workers and Occupational Health Risks. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Health 2018, 2, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desa, A.; Kadir, N.A.; Yusooff, F. Environmental Awareness and Education: A Key Approach to Solid Waste Management (SWM)—A Case Study of a University in Malaysia. In Waste Management—An Integrated Vision; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2012; pp. 101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Cossu, R.; Masi, S. Re-thinking incentives and penalties: Economic aspects of waste management in Italy. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 2541–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, S. Standardized Technology Evaluation Process (STEP) User’s Guide and Methodology for Evaluation Teams; The MITRE Corporation: Bedford, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Round Table. Eco Design of Plastic Packaging; German Association for Plastic Packaginings and Films: Bad Homburg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CEFLEX. Designing for a Circular Economy: Recyclability of Polyolefin-Based Flexible Packaging; CEFLEX: Bergschenhoek, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- RECOUP. Plastic Packaging: Recyclability by Desing; RECOUP and British Plastics Federation (BPF): Cambridgeshire, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- CONAI Guidelines to Facilitate the Recycling of Plastic Packaging. Available online: http://www.progettarericiclo.com/en/docs/guidelines-facilitate-recycling-aluminium-packaging (accessed on 9 December 2021).

- OECD. Considerations and Criteria for Sustainable Plastics from a Chemicals Perspective and Technical Tools and Approaches in Design of Sustainable Plastic; OECD: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Plastic New Zealand. Design for the Environment; Plastics NZ: Manukau City, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- CITEO. Sorting info Guide Making Sorting Simpler; CITEO: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- COTREP. Recyclability of Plastic Packaging: Eco-Design for Improved Recycling; COTREP: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- FH CAMPUS WIEN. Circular Packaging Design Guideline Design Recommendations for Recyclable Packaging; FH Campus Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Network for Circular Plastic Packaging. Reuse and Recycling of Plastic Packaging for Private Consumers; Plastindustrien: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WRAP. Design of Rigid Plastic Packaging for Recycling Guidance; WRAP: Banbury, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Der Grüne Punkt. Design 4 Recycling; Der Grüne Punkt: Köln, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nation Environment Program. Technical Guidelines for the Identification and Environmentally Sound Management of Plastic Wastes and for Their Disposal; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trash Free Seas Alliance and Ocean Conservancy. Plastic Policy a Playbook: Strategies for a Plastic-Free Ocean; Ocean Conservancy: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Association of Cities and Regions for Recycling. Good Practice Guide on Waste Plastic Recycling, a Guide by and for Local and Regional Authorities; ACRR: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP; World Resources Institute. Tackling Plastic Pollution: Legislative Guide for the Regulation of Single-Use Plastic Products; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Plastic ZERO. How to Prepare a Road Map for the Management of Plastic Waste; Plastic ZERO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa. Guidelines on Separation of Waste at Source; Government of Republic of South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018.

- UN Environment. Single-Use Plastics: A Roadmap for Sustainability; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Marine Litter Legislation: A Toolkit for Policymakers; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment Program. Marine Plastic Debris & Microplastics: Global Lessons and Research to Inspire Action and Guide Policy Change; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Plastic ZERO. Green Public Procurement Manual on Plastic Waste Prevention; Plastic ZERO: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Canada. Guidance for the Reduction of Plastic Waste in Meetings and Events; Government of Canada: Ottawa, Canada, 2018.

- SEA-PLASTIC-EDU Consortium SEA-PLASTIC EDU. Available online: http://plasticedueprints.io1cus.co.uk/%0A (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- Western Cape Government. A Guide to Separation of Waste at Source; Western Cape Government Department of Environmental Affairs: Cape Town, South Africa, 2019.

- International Labor Organization. Work Adjustment for Recycling and Managing Waste; International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- GiZ Germany GIZ Webinar Series for E-Waste Plastic Recyclers. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DoopWyYfZkM&list=PLE-AQTsQB0uMOrJadvRbCKpwvdAquE__e&index=1&ab_channel=StEPInitiative%0A (accessed on 12 December 2021).

- StEP and SERI. Processing of WEEE plastics: A practical handbook; StEP: Vienna, Austria, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. Start Your Waste Collection Service; International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- International Labor Organization. Start Your Waste Recycling Business: Trainers Guide and Technicals Handouts; International Labor Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Health & Safety Laboratory. Manual Handling in Refuse Collection; HSL: Sheffield, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa. Recycling Training Manual; Department of Environmental Affairs Republic of South Africa: Cape Town, South Africa, 2017.

- UN Habitat. Strategy Guidance: Solid Waste Management Response to COVID-19; UN Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Waste Management Mixed Curbside Residental Recycling Myths and Free Your Recyclables. Available online: https://www.wm.com/location/california/sacramento-valley/_documents/2019/RevisedMyth-busters_RecyclingMyths1_31_19FINAL.pdf%0A (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- UN Environment; Government of India. Towards Responsible Use of Plastics Reduce, Reuse, Recycle Centre for Environment Education, India a Manual for Schools; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- WWF. Stop the Flood of Plastic Effective Measures to Avoid Single-Use Plastics and Packaging in Hotels; WWF Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Asociacion Colombiana de Industrias Plasticas. Manual on Plastic Recycling; Asociacion Colombiana de Industrias Plasticas: Bogota, Colombia, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5GYRES Trash Academy. Available online: https://www.5gyres.org/trash-academy (accessed on 11 December 2021).

- UN Environment; Celan Seas. Tide Turners Plastic Challenge; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Waste Management Recycling Resource. Available online: https://www.wm.com/us/en/recycle-right/recycling-resources (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- 5GYRES. The Plastic Journey A K-5 Plastic Pollution Curriculum; 5GYRES: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- UN Environment; Celan Seas. The Back to School Plastic Challenge: Start the Second School Year by Breaking Up with Single-Use Plastic; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 5GYRES. TrawlShare STEM to Stern Marine Plastic Pollution Educational Units for Students Learning at Sea; 5GYRES: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- PREVENT Waste Alliance. EPR Toolbox | Know-How to Enable Extended Producer Responsibility for Packaging; PREVENT: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Extended Producer Responsibility: A Guidance Manual for Governments; OECD: Paris, France, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Development of Guidance on Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Institute for European Environmental Policy; WWF. How to Implement Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR); WWF Germany: Berlin, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio del Ambiente del Perú. Training Guide for Waste Pickers for Their Inclusion in Municipal Formalization Programs; Government of Peru: Lima, Peru, 2010.

- GiZ and StEP. E-Waste Training Manual; GIZ Germany: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP. Health and Safety Guidelines for Waste Pickers in South Sudan; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sahajwalla, V.; Gaikwad, V. The present and future of e-waste plastics recycling. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2018, 13, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).