Abstract

City logistics is subject to constant development, generated by new logistics trends and high customers’ expectations. With the aim of creating an effective, acceptable, and sustainable city logistics policy, it is therefore essential to understand logistics trends and their expected impact on the development of urban freight transport in the future. In this paper, we explore and compare the expectations of public authorities, business, and academia regarding the short-, medium-, and long-term impacts of different logistics trends on urban logistics. Following a literature review, the expert survey was used to assess the expected impact and time horizon. According to the respondents, “e-commerce”, “automated vehicles”, “electric vehicles”, “grey power logistics”, “omni-channel logistics”, and the “desire for speed” will have the greatest impact on urban freight transport in the future. An interesting observation concerns some differences of opinion between public and private stakeholders. In general, the business community believes that the identified trends will have a greater impact on urban logistics in a shorter period of time, while public authorities believe that the mentioned trends will have a less strong impact on urban logistics in a longer time scale. This shows the need for more active collaboration between them in the policy-making process.

1. Introduction

Between the 1990s and the beginning of the twenty-first century, studies and pilot tests were carried out in European cities with the aim of reducing urban freight traffic, accidents, and pollution [1,2,3,4,5]. These resulted in various policies and restrictions (Urban Vehicle Access Regulations—UVAR) for urban freight transport [6,7,8,9]: e.g., Low Emission Zones (LEZ), delivery time windows, vehicle weight and/or size restrictions, and congestion charging. Some positive results have been achieved, but the problems in urban freight transport still persist [10].

A possible explanation for this inefficiency is the prevailing approach of policies which target only one specific negative impact (e.g., congestion) and does not consider all different aspects [11]. This leads to certain measures only having an impact on one particular aspect [12]. Moreover, some policies and measures mainly target the city centres and the last mile of traditional supply chains [13,14,15,16]. To understand the opportunities to mitigate urban freight flows and to address the problem in a holistic way, different aspects need to be covered and urban freight transport needs to be considered at the level of the entire supply chain, including business strategies [17,18,19].

The next possible reason is the complexity of urban logistics processes which is mainly due to the numerous and diverse stakeholders with their different and sometimes contradictory expectations [20]. Traditionally, receivers, carriers, and forwarders are seen as the most relevant stakeholders, but they are often not included in the policy-making process. The involvement of all relevant stakeholders is considered a prerequisite for the successful implementation of policies and for reducing potential conflicts between them [21].

Another reason for problems in urban freight transport is the rapid development of new logistics services supported by advanced information technology (IT) solutions [22,23,24]. Policy makers are in many cases not fully aware of these emerging trends and do not recognize the real needs and opportunities. This often leads to a conflict of interest between restrictive policies and commercial needs [25]. To solve this problem, a proactive approach is suggested to develop policies that take into account the expected evolution of logistics and its emerging trends.

As can be seen, today there are still some problems in designing an efficient urban freight transport policy and solutions are being sought for a more efficient approach. A comprehensive solution can only be achieved by addressing the problems holistically (multiple aspects, supply chain level), taking into account the opinion of different stakeholders and users (private and public) and considering new and emerging technological and logistics trends.

The main objective of this article is therefore to comprehensively address the problem of urban logistics, identifying and summarizing existing and emerging trends in order to recognize the most important ones and assess their impact on the future development of urban freight transport. The assessment is based on an international expert survey among different stakeholders to understand their perceptions and expectations.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the logistics trends identified in the scientific literature. Section 3 presents the survey methodology and the analysis/interpretation of results. Section 4 highlights the main elements worth discussing. Section 5 concludes this paper and suggests topics for future research.

2. Review of Logistics Trends

Nowadays, urban logistics faces numerous challenges and demands for faster and more reliable deliveries [26,27]. Customer expectations are rising with the demand for more efficient, environmentally friendly, and cost effective logistics services [28]. To understand the motivation for these demands, we need to look for existing and emerging trends and its potential impact on urban freight transport.

The main source for identifying new trends for this research, was the scientific literature. In addition, trends were identified using business reports of logistics and consulting companies [29,30]. Based on the review, many trends were identified which, for the purpose of this research, were grouped into the following four main categories: changes in consumption and production; spatial organization characteristics; supply chain and distribution; technologies and equipment.

The main trends and the results of the literature review relevant to each selected category are briefly described below.

2.1. Consumption and Production Trends

The growth of e-commerce (electronic commerce) and the increasing range of services provided by retailers (e.g., click and collect) are leading to new patterns of urban freight flows and vehicle movements in urban areas [28,31,32]. Please note that “click and collect” is a purchase where the order and payment is made online, while the customer collects the purchase from a shop.

Several studies predict a significant increase in demand for products and services related to the elderly. Logistics for an aging society, also known as “Grey Power Logistics”, is likely to be a major contributor to urban freight transport in the future. We can assume that home delivery of food and medicines will increase, hospitals will introduce logistics solutions to facilitate patient care, packaging will be adopted for the elderly etc. [33].

In recent years, consumers have become more aware of the environmental sustainability of the products they buy. Companies are doing their best to turn social and environmental challenges into opportunities by producing sustainable solutions that generate social and business benefits [34]. This trend will increase transparency within supply chains, require new concepts of circular economy in logistics, and will impact, or perhaps even disrupt, the logistics industry over the coming years [19,33,35].

In the future, consumers are expected to share access to products or services, rather than owning them individually. Sharing logistics infrastructure and services with competitors is part of collaborative business [36]. Facility and capacity sharing will lead to consolidation and better utilization, which will decrease freight traffic, number of vehicles, and empty runs in collaborative logistics services. Brokerage platforms will bring together customers and logistics service providers for innovative on-demand services in cities [36,37].

Consumer-driven concept will lead to a pull logistics strategy and will require responsive production with highly optimized and streamlined processes.

2.2. Spatial Organization Trends

Most consumers and retailers are located in city centres, while logistics facilities are on the periphery. This phenomenon, referred to as “logistics sprawl”, is expected to continue and consequently increase the distances travelled by freight vehicles serving retail, commercial and residential areas in cities [26,38].

The spatial centralization of warehousing will continue to be driven by manufacturers and retailers to achieve cost savings in their supply chains. This will lead to an increased use of a few, large national and regional distribution centres serving a much larger geographical area [39]. As a result, urban areas will be increasingly more supplied from these large centres, while smaller distribution centres within urban areas will be reduced.

The establishment of Urban Consolidation Centres (UCCs) on the periphery of urban areas, with new business models that can cover infrastructure investments is expected to continue [40]. Due to the difficulties in reaching a critical mass of users, only a limited impact is expected [41]. In the future, different unattended and attended pick-up points (locker boxes, fuel stations) will be established. Pick-up points will have a very high impact on freight transport, in particular in city centres [42].

Road transport will remain the predominant mode for transporting goods over short distances, with the main problem being low vehicle utilization and empty runs [43]. These problems need to be addressed by the authorities and resolved at the regional level.

The creation of Freight Quality Partnerships (FQP), Living Labs (LL), and other concepts will support local governments, business entities, logistics operators, environmental organizations, local communities and other stakeholders to collaborate in order to solve specific problems in freight transportation [44,45,46]. Note that FQPs are collaborative networks of freight partners that work together on logistics operation issues, share information and experiences, and develop a common freight strategy [44]. A Living Lab, on the other hand, is a dynamic environment where solutions are developed and tested in real contexts (in our case cities) with multiple implementations by different stakeholders in parallel [47].

2.3. Supply Chain and Distribution Trends

As the concept of “Internet of things” (IoT) and even “Internet of everything” (IoE) expands, there are more opportunities to connect supply chains and improve visibility [48]. Third party logistics providers (3PLs) will join together and everyone else will likewise increase their willingness to collaborate [49]. Consolidation of logistics providers will also lead to consolidation of freight and consequently have a positive impact on freight traffic in cities [50].

While globalization has been an ongoing trend for several decades, some companies have begun to consider investing in the opposite direction [51]. In particular, after the COVID-19 period, more and more companies have decided to move production (manufacturing) closer to end users [52]. This already results in less transportation and shorter lead times.

The demand for a trusted local and regional food supply is already growing and is expected to continue into the future. This will change regional supply chains, further increase the need to create alternative and short food networks (AFNs), and affect transportation/logistics processes within and between EU regions [53].

3D printing will enable manufacturing of specialized products at decentralized locations, closer to customers. In the long run, this will reduce freight traffic, especially distribution of goods and the need for reloading of parcels for last mile delivery [13,54]. It will also reduce inventory in warehouses and retail stores as well as packaging waste.

Omni-channel retailing is becoming more widely used. It enables the integration of multiple online and offline channels, so that consumers can purchase, pick up, and/or receive goods through a single system [13]. Logistics is becoming a precondition for the retail industry and will create innovative omni-channel solutions for personalized and dynamic delivery services at competitive prices. As a result, some innovative solutions have been developed in recent years that set new standards also in the field of urban logistics, such as same-day or one-hour deliveries, the introduction of parcel lockers, and even the concept of car–trunk deliveries [14,55]. This increases the need for freight transport, reduces the utilization of freight vehicles and increases the number of empty journeys in urban centres.

2.4. Technologies and Equipment Trends

New technologies are changing existing patterns and leading to new solutions including urban freight delivery. The use of compressed natural gas (CNG) and electric vehicles (EVs) has proven to be an efficient and promising strategy for urban freight transport, especially from an environmental point of view. EVs in particular have proven to be an important alternative for deliveries from urban micro-consolidation centres to customers in inner urban areas, where urban access regulation often apply [56,57]. Improved internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs) will continue to dominate in the short term, while hybrid or electric vehicles will dominate in the long term [58].

The logistics industry is increasingly dependent on information and communication technologies (ICT). The introduction of innovative ICT solutions is already transforming logistics services, leading to consolidation of packages, shorter and optimized journeys, and better utilization of vehicles [28], benefiting both the industry and the environment. The use of ICT enables customers to find the most appropriate services for their needs, and logistics providers to strategically manage freight deliveries [59].

Application of ICT and Intelligent Transport Systems (ITS) enables easy and cost-effective collection of various data on the urban freight movements. The analysis of Big Data (large and complex data sets) of truck movements in urban areas provides insights into driver behaviour and identification of potential for improvement [60]. An unprecedented amount of data can be collected from numerous sources along the supply chain. Harnessing the value of Big Data offers enormous potential to optimize vehicle utilization, enhance customer experience, decrease risk, and develop new business models.

The use of ICT in urban logistics will lead to price reductions and influence the behaviour of individual companies and consumers as well as the city’s logistics system. The Internet and ITS will not only influence the logistics system, but also Business-to-Customer (B2C) and Business-to-Business (B2B) e-commerce, e-logistics, e-fleet management, and cooperation opportunities for customers and logistics providers [24].

In addition to the introduction of new vehicle powertrains, ICT and ITS, the rapid advancement of various technologies has enabled practical use of fully automated road vehicles and this trend intensify in the future [61]. Urban environment systems are expected to follow a path where the application of highly automated vehicles is initially limited to certain environments and then gradually expands to less controlled ambiances. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, e.g., drones), which are designed to deliver parcels from distribution centres directly to customers, also show some promise [62].

2.5. Conclusion of the Literature Review

It can be concluded that most of the trends analyzed were initiated on the basis of advanced technologies that have been developed in recent years and have proven successful in various industries. The rapid development of ICT, ITS, and IoT technologies, followed by advanced (Big) data analytics, plays an important role in the logistics industry today, leading to highly transparent, agile, and automated logistics services. Urban logistics is already taking advantage of some solutions, but an even greater expansion is expected in the future.

Environmental aspects are the second most important driving force of the identified trends. Sustainability is clearly at the heart of many logistics trends, setting new standards for environmentally friendly vehicles and fuels. Shorter (regional) supply chains, planning and bringing production closer to the customer, demand-driven (more flexible) logistics services, and other innovations are becoming the standard for logistics in general and for city logistics in particular.

All identified trends are expected to have an impact on urban freight transport and change urban freight flows and vehicle movements in cities, which in turn should lead to a reduction in negative environmental impacts. Therefore, this work aims to contribute to understanding these trends, which can help urban planners and policy makers be proactive and support the development of innovative and efficient solutions.

3. Assessment of Logistics Trends, Impact, and Time Horizon

3.1. Methods and Material

The research was initiated based on the trends identified and described in the previous section, which leads to the main research question: What is the expected impact of a particular trend and when will it be most evident? Since there is little literature on the impact of logistics trends on urban freight transport, we decided to conduct a survey among stakeholders (experts) and ask them for their opinion. The experts were asked to give their opinion on the impact and time perspective using a stated preference method.

The main objective is to review general trends and expectations regarding the impact of logistics trends on urban logistics. Therefore, it is important that the sample includes stakeholders from different countries and cities. In this way, opinions are generalized, and we obtain general trends for urban logistics [63]. This approach required the implementation of an electronic questionnaire. An electronic questionnaire safeguards secrecy, is less invasive, and can reach a larger audience in terms of time and location at a lower cost when compared to other solutions. It has to be noted, however, that validating the respondents’ eligibility is more challenging, and response rates tend to be lower, which can lead to non-response bias [64].

For the survey, the trends (based on the literature review presented in the previous chapter) were categorized into 4 areas, 9 themes and 13 drivers, as shown in the Table 1 below. The term “driver” is used to represent driving force of an identified trend that is expected to change logistics processes in urban areas.

Table 1.

Categorization of logistics trends/drivers.

The survey briefly described each trend and asked participants to qualitatively rate the impact of each driver on a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing very low impact and 5 representing very high impact. Regarding the time frame in which participants believed the respective driver would have an important impact (is likely to occur), the following options could be chosen: “Short-term: 1–5 years”, “Medium-term: 5–10 years”, “Long-term: 10–20 years” and “Never”.

The experts were carefully selected and identified from the list of the most successful scientific authors in the field of urban logistics (WOS and SCOPUS database). These experts were then invited to participate in the survey and were also asked to propose qualified experts from the business community and key representatives of public authorities in their country. For the public authorities’ segment, relevant experts were also identified from the list of most advanced public authorities that have successfully developed Sustainable Urban Logistics Plans (SULP) or similar strategic documents [11].

A total of 415 experts were identified from four categories: business sector; authorities; research; other (mainly associations). A total of 63 responses were obtained (15% respond rate) from 24 countries (Austria; Australia; Belgium; Bulgaria; Croatia; Czech Republic; Denmark; France; Germany; Greece; Hungary; India; Italy; Latvia; Netherlands; Poland; Portugal; Romania; Slovenia; Spain; Sweden; Switzerland; United Kingdom; United States of America). As these are carefully selected experts, we consider this to be a sufficiently large and representative sample. A total of 61 respondents come from Europe, which is why we consider the sample to be homogenous.

The expert survey was uploaded to the EUSurvey portal. The experts were then contacted by mail and asked to participate and complete the online questionnaire.

The results are presented below in tabular and graphical form.

3.2. Results

Results in this section show average values for the entire sample of respondents. This allows to understand predominant opinion concerning a particular trend, its impact, and time horizon.

3.2.1. Impact Assessment

Table 2 shows the drivers sorted in descending order by the value associated with the dimension “impact”. In addition, the percentage deviations from the grand mean are shown for each individual driver.

Table 2.

Impact ranking.

For the “impact” dimension, all drivers range between the minimum value 2.7 (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) and maximum value 4.2 (E-commerce). Experts assessed the overall importance of the 13 drivers positively, with the range being oriented to the higher values (upper side of the Likert scale). The grand mean of all drivers in relation to the “impact” is 3.6 (low to moderate impact).

Another important aspect is the percentage deviations (Δ) of each driver from the grand mean. An impact that is at least 10% higher than the average (high impact) is related to three drivers: “E-commerce”, “Automated vehicles”, and “CNG and EV for urban freight”. A deviation of at least 10% (in fact more than 20%) lower than the average (low to moderate impact) is represented by two drivers: “Environment and sustainability”, and “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”.

3.2.2. Time Horizon Assessment

Table 3 below reports the drivers categorized by the value associated with the “time horizon” dimension. The table shows the expert panel overall assessment of the timeframe in which the driver is likely to occur or have an impact on urban logistics, from the greatest to least temporal proximity.

Table 3.

Time horizon ranking.

With regard to the time horizon scale, all drivers lie between the minimum value 1.7 (“Omni-channel logistics”) and maximum value 2.7 (“Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”). The mean of all drivers in relation to the “time horizon” dimension is 2.2 (i.e., close to the value 2 which means medium term “5–10 years”). This means that the overall assessment of the expert panel points to the medium range of the spectrum rather than the short range (i.e., “1–5 years”) or the long range (i.e., “10–20 years” and “Never”).

Additionally, in this case, percentage deviations of the individual drivers from the grand mean were analyzed. Time horizon that is at least 10% below the average (short-term impact) is related to two drivers: “Omni-channel logistics” and “Desire for speed”. A deviation that is at least 10% above the average (medium- to long-term impact) is related to: “Environment and sustainability”, and “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”.

3.2.3. Relative Importance Referring to Impact and Time Horizon (Entire Sample)

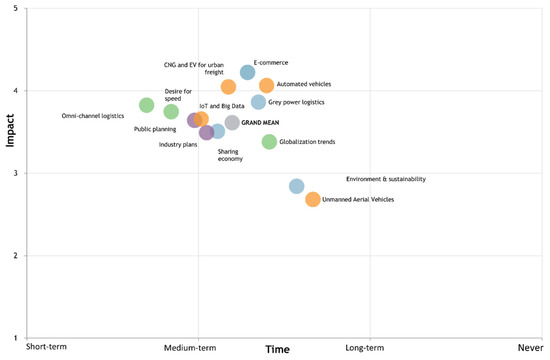

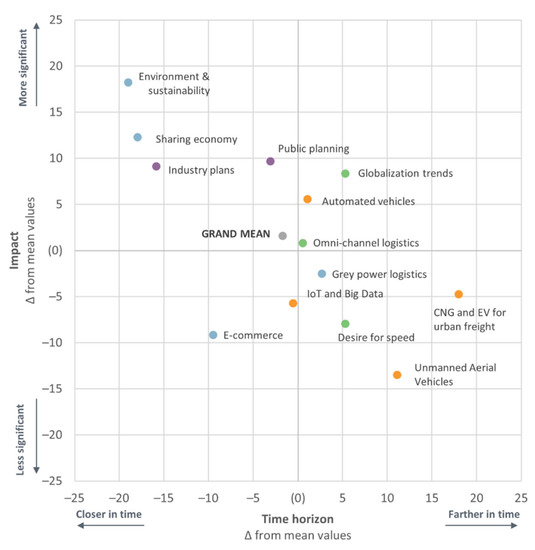

The relative importance of impact related to the temporal dimension is shown graphically in Figure 1. The main category of each driver is represented by the small circles: blue—consumption; purple—spatial planning; green—distribution and supply chain management; orange: technologies and equipment; grey: is used for the grand mean. The same notation applies to Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 1.

Urban logistics drivers’ impact and time positioning (grand mean and mean values).

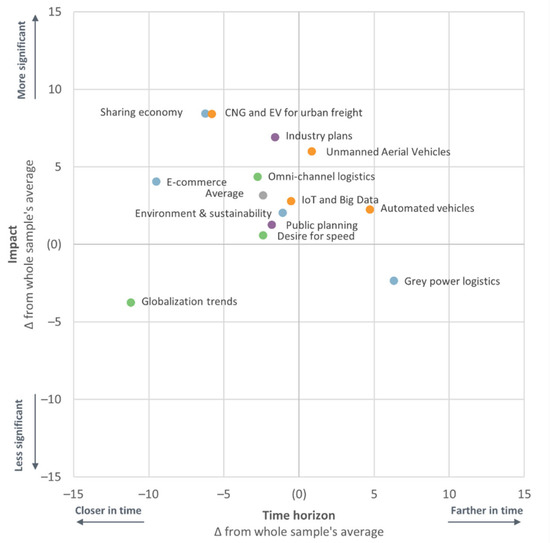

Figure 2.

Business sector—drivers’ impact and time horizon, percentage deviation (Δ) from mean values.

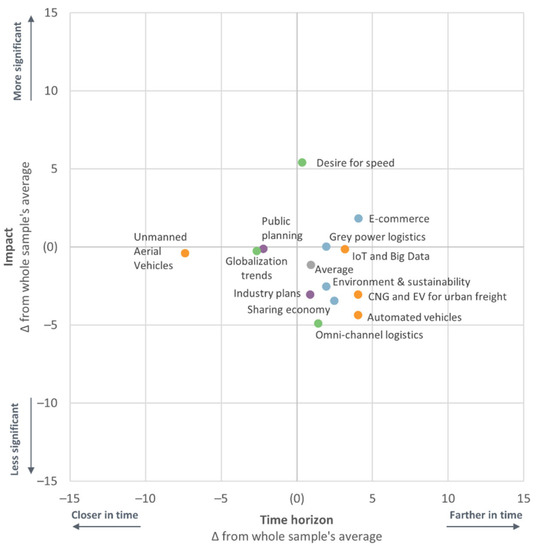

Figure 3.

Authorities—drivers’ impact and time horizon, percentage deviation (Δ) from mean vales.

Figure 4.

Research—drivers’ impact and time horizon, percentage deviations (Δ) from mean values.

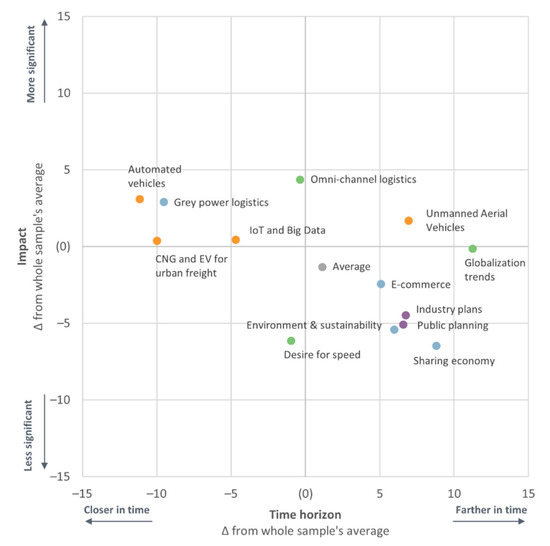

Figure 5.

Others—drivers’ impact and time horizon, percentage deviation (Δ) from mean values.

The analysis of relative importance in terms of impact and time horizon revealed categorization in for clusters: medium to high impact in short to medium term (MH/SM), medium to high impact in medium to long term (MH/ML), high to very high impact in medium to long term (HV/ML) and low to medium impact in medium to long term (LM/ML).

According to the respondents, “Omni-channel logistics”, “Desire for speed”, and “Public planning” belong to the MH/SM cluster. These trends are expected to have a major impact in a relatively short time horizon. Five of the thirteen drivers, “IoT and Big Data”, “Industry plans”, “Sharing economy”, “Globalisation trends”, and “Grey power logistics” belong to the MH/ML cluster. These trends are also expected to have important impacts but in a slightly more distant future than the trends in the previous cluster. “E-commerce”, “CNG and EV for urban freight”, and “Automated vehicles” belong to the HV/ML cluster. These trends are expected to have the greatest impact on urban freight transport, but this impact is only expected in the medium to long term. The last LM/ML cluster consists of “Environment and sustainability” and “Unmanned aerial vehicles”. These trends are expected to have a smaller impact in the medium to long term.

Further research was carried out in order to find out whether there were significant deviations in relation to mean values for certain groups of respondents (“business”, “authorities”, research”, and “others”). The results obtained are presented below.

3.3. Results—Business Sector

Table 4 shows the values for “impact” and “time horizon” on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 and 1 to 4 respectively, and for each driver, the percentage deviation (Δ) of the business sector expert opinion from the mean values is reflected in the entire sample.

Table 4.

Impact and time horizon mean values and deviations for each diver—business sector.

The values for impact and time horizon deviations reported in Table 4 are presented in Figure 2. It shows the perception of the business sector compared to the mean vales of the entire survey sample.

The majority of the deviations related to business sector presented in Figure 2 are located in the upper left quadrant of the diagram. In particular for “Sharing economy” “CNG and EV vehicles”, “Industry plans”, “Omni-channel logistics” and “E-commerce” are expected to have a greater impact in expected in narrower time frame.

“Grey power logistics” is the only driver located in the lower right quadrant of the diagram (less significant impacts are expected in longer time frame). “Globalization trends” is the only driver located in the lower left quadrant (less significant impacts are expected in a shorter time frame). “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” and “Automated vehicles” are in the upper right quadrant (significant impact is expected in a longer time frame).

3.4. Results—Public Authorities

Table 5 shows the values for “impact” and “time horizon” on a Likert scale of 1 to 5 and 1 to 4 respectively, and for each driver the percentage deviation (Δ) of the authorities’ opinion from the mean values of the entire survey sample.

Table 5.

Impact and time horizon mean values and deviations for each diver—Public authorities.

The values for impact and time horizon deviations reported in Table 5 are presented in Figure 3. It shows the perception of the authorities compared to the mean vales of the entire survey sample.

The majority of the deviations related to the authorities presented in Figure 3 are located in the lower right quadrant of the diagram. In particular “Automated vehicles”, “CNG and EV for urban freight”, “Omni-channel logistics”, “Industry plans”, and “Environment and sustainability” are expected to have less significant impacts in a longer time frame.

“Desire for speed” is expected to have a much higher impact, close to average opinion referring to time horizon, whereby impact of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” is expected to be much closer in time.

3.5. Results –Research

Table 6 shows the values for “impact” and “time horizon”, on Likert scales of 1 to 5 and 1 to 4, respectively, and for each driver the percentage deviation (Δ) of the researcher’s opinion from the mean values of the entire survey sample.

Table 6.

Impact and time horizon mean values and deviations for each diver—research.

The values for impact and time horizon deviations reported in Table 6 are presented in Figure 4. It shows the perception of the researchers compared to the mean vales of the entire survey sample.

Deviations presented in Figure 4 indicate a broader range than for the previous groups. The other important observation is that the deviations of the impact are less significant than for time horizon. Despite that, the average opinion of researchers is placed in a lower right quadrant.

In particular “Sharing economy”, “Public planning”, “Environment and sustainability”, “Industry plans” and “E-commerce” are expected to have less significant impacts in a longer time frame. On the other hand, “Automated vehicles”, “Grey power logistics” and “CNG and EV for urban freight” are expected to have a more significant impact in a shorter time frame.

3.6. Results–Others

Table 7 shows the values for “impact” and “time horizon”, on Likert scales of 1 to 5 and 1 to 4, respectively, and for each driver, the percentage deviation (Δ) of the group “Other” opinion from to the average values of the entire survey sample.

Table 7.

Impact and time horizon mean values and deviations for each diver–others.

The values for impact and time horizon deviations reported in Table 7 are presented in Figure 5. They show the perception of the “other” group compared to the mean vales of the entire survey sample.

Deviations presented in Figure 5 are even more intense than in the group of researchers. In general, average opinion of the “other” group is placed in an upper left quadrant, which indicates slightly more significant impact of trends closer in time.

The following two extremes are worth mentioning: “Environment and sustainability” and “Sharing economy” are perceived of having much higher impact on urban logistics closer in time, whereby “CNG and EV for urban freight” and “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”) are considered likely to have a much smaller impact on urban logistics further in time.

3.7. Statistical Relevance of the Results

To assess statistical relevance of the results, we conducted several statistical tests using SPSS (version 28.0, IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). To test the reliability of all 13 drivers, we used Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. In this study, a value of 0.577 was obtained for “impact” (if driver 8 is excluded, the value increases to 0.621), while a value 0.701 was obtained for ‘‘time’’. Please note that the results are considered reliable if the Cronbach’s Alpha is above 0.6 [65,66].

One of the most important results is the relationship between ‘‘time’’ and ‘‘impact to selected ‘‘drivers’’ (time–driver and impact–driver relation was obtained as significant with the Chi-squared test with p < 0.05 for corresponding contingency tables).

Next, we considered the dependencies between ‘‘impact’’ and ‘‘time’’. The dependence was confirmed as significant by the Chi-squared test with p < 0.001. Note that this is the most important relation from a professional (logistics) point of view and at the same time, it is the goal of this paper. Note that the ‘‘impact’’ vs. ‘‘time’’—dependence is also significant, if the data are divided into four groups: authority, business, research, and others. This confirms the assumption that there is a time–impact relationship for all groups (also partially). At the same time, this justifies that we look for possible differences in the existing relations between groups.

To assess the differences between the groups, we used the ANOVA test. The results are not confirming statistically significant differences between the groups (with p = 0.204 for impact and p = 0.576 for ‘‘time’’). Probably, the only reason for this is a rather large variance in the sample.

Please also note that the results of this study are based on a sample of 63 respondents and a response rate of 15%, which is more than expected in online surveys [64]. If the entire pool of experts would have responded, we would be able to understand this as a population. Therefore, some care must be taken to generalize the results to the population (which is also a limitation).

4. Discussion and Implications

The objective of this research was to identify key logistics trends and assess their likely impact on urban logistics. A hypothesis about the different perceptions of stakeholder groups regarding the future development of logistics trends and their impact on urban freight transport was formulated and tested. The following conclusions can be made:

- The business community apparently regards the “Globalization trends” as already present and evident, and therefore does not expect any additional important impact on urban areas. On the other hand, important impacts are expected in a shorter time frame, especially in the areas of “Sharing economy”, “CNG and EV for urban freight”, “Industry plans”, “E-commerce”, and “Omni-channel logistics”. Technological solutions such as “Unmanned Aerial vehicles”, “Automated vehicles” and the use of “IoT and Big Data” will play an important role in their opinion, but in a somewhat more distant future. In general, most trends are found in the upper left quadrant of the scatter plot. This means that the business community believes that the trends mentioned will have a greater impact on urban logistics, and in shorter period of time than the other stakeholder groups.

- The stakeholders of the authority group consider the “E-commerce” as the most important trend that will influence urban freight transport in the medium-term future. “Omni-channel logistics” and “Desire for speed” are on the other hand perceived as highly influential already on a short term. Another very interesting observation is their expectation that “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” (e.g., drones) will influence urban freight transport much earlier than the expectations of the other stakeholders’ groups. In general, most of the trends are in the lower right quadrant of the scatter plot, which means that the authorities believe that the indicated trends will have less significant impacts on urban logistics, and over a longer period of time.

- In the research community, almost all trends belonging to the core area of “Consumption” and “Land use and planning” are located in the lower right quadrant of the scatter plot (less important). In contrast, almost all drivers belonging to the “Technologies and Equipment” domain are in the upper left quadrant of the scatter plot (more important). This could be explained by the fact that researchers are predominantly dealing with technological innovations and prefer these kind of solutions.

In sum, the results show that stakeholders groups indeed have some different views on the importance of certain logistics trends and their impact on urban freight transport in the future. Of particular importance is the difference between public and private stakeholders, who in some cases have slightly different perceptions. This could well be one of the reasons why urban freight transport policies have had limited impact despite the enormous efforts made by the public sector in recent years.

The results clearly point to the need for a different approach in future urban freight transport policy planning. On the one hand, policies and measures should be designed in line with the latest trends that announce the development of activities and solutions. So, not only to solve current problems, but also to look into the future. This should be conducted on the basis of identified trends, which experts believe will have an important impact in the medium and long term. Since this is rarely the case today, the logistics industry is often ahead of politics, which often leads to disagreements [48].

The different perceptions between public and private stakeholders suggest that various interest groups and actors need to be involved in the policy planning process. In this way, there is an exchange of knowledge, best practices, and views that will lead to more efficient urban freight transport [2]. Such solutions can be found in the literature under the terms Freight Quality Partnership (networking of logistics companies) and Living Lab (testing of innovative solutions in collaboration between stakeholders and actors) [45,46,67]. In this way, the diametrically opposed goals of business and the public sector could be overcome, resulting in economically viable solutions that simultaneously address environmental constraints.

Given that many of the identified trends are closely linked to modern technological solutions based on the analysis and advanced processing of Big Data, greater consideration should be given to the principles of evidence-based policy making as expressed in some European Commission guidelines [68]. This is the principle of closely monitoring the progress of an activity before a measure is introduced, which can provide a benchmark for determining the impact after the measure is introduced. In this way, we obtain feedback on the success of the measure. In the past, advanced data processing (artificial intelligence, data mining) was not possible due to lack of technological solutions and systems [26,69]. In our opinion, this is the last key element that should be upgraded in order to create an efficient service for all stakeholders and, ultimately, for the city’s residents.

5. Conclusions

The rapid change in demand for more efficient urban logistics, faster, and more reliable deliveries, requires a corresponding adaptation of logistics practices, and consequently, urban freight transport policies. As the pace of change accelerates, it is not enough to just adapt to emerging trends, but we need to anticipate them and be proactive. Indeed, this is only possible if we identify and recognize the key trends in logistics and assess their potential impact on urban freight transport in the future.

To this end, we conducted an extensive literature review and selected the most promising trends to evaluate. A comprehensive questionnaire was created to identify the expected impact and the time period in which the impact of a particular trend is likely. An international pool of experts from academia, business, and public authorities was identified and selected to provide the most relevant and reliable results possible. A total of 63 experts from 24 countries participated in the survey and gave their valuable opinion.

The trends that the experts believe will have a major impact in the short term are addressed first, in particular, the “Desire for speed” and “Omni channel logistics”. Both trends can already be observed in urban areas today and, in some cases, already have a significant impact on urban freight transport. The demand for faster deliveries, for example, leads to a fragmentation of urban freight flows, which is why collaborative, flexible, and environmentally friendly solutions should be pursued. The combination of traditional and e-commerce channels on the other hand has a positive impact on urban freight transport, especially through the introduction of the hybrid channel, BOPS (Buy Online, Pick Up in Store) and other similar strategies.

In addition, the focus should also be on the trends that will influence urban freight transport in the medium term, especially those that are expected to have a major impact. Besides “E-commerce” which is strongly linked to “Omni channel logistics”, the experts attach the greatest importance to “CNG and EV for urban freight” and “Automated vehicles”. These trends are perceived by the experts as the most influential. The goal of policy makers is first to understand these new technologies and then, for example, to support the purchase of environmentally friendly vehicles and give them some priority in accessing urban areas. This role is particularly underlined by the high ranking of the following two trends “Public planning” and “Industry plans”. Both are expected to have an important impact on urban freight in a relatively short time.

Understanding these global logistics trends is crucial for all urban logistics stakeholders, especially city authorities. Feedback from the business community and researchers is very useful, as it can create a system of mutual support for the design and adoption of policies and, consequently, the implementation of new measures. With the development of new technologies, an even faster progress and, consequently, a more flexible urban transport policy, can be expected

The constant development of new trends makes it necessary to repeat this research and update the results to keep up with the innovations that may affect urban freight transport in the near future. Furthermore, we would recommend bringing even more experts on board to make additional comparisons in terms of differences between countries, between small and large cities, and for cities with different GDPs and levels of development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L., M.M. and G.L.; methodology, T.L., M.M. and G.L.; validation, T.L. and K.H.; formal analysis, T.L. and K.H.; investigation, T.L., M.M. and K.H.; data curation, G.L. and T.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L.; writing—review and editing, T.L. and M.M.; visualization, T.L. and G.L.; supervision, M.M.; project administration, T.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially funded by Interreg CENTRAL EUROPE, project CE222-SULPITER and ARRS (Slovenia), Research program No P1-0288.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University of Maribor, Faculty of Civil Engineering, Transportation Engineering and Architecture (approval code 001-TT/2022 and date of approval: 28 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

According to the statement of the contributors, the data are not publicly available, but are kept by the authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere thanks to the many experts who responded to our survey and made this research possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ville, S.; Gonzalez-Feliu, J.; Dablanc, L. The Limits of Public Policy Intervention in Urban Logistics: Lessons from Vicenza (Italy). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2013, 21, 1528–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, U.; Geiger, C.; Pöting, M. Hands-on Testing of Last Mile Concepts. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, A.; Marzano, V.; Mauriello, F.; Vitillo, R.; Fasanelli, R.; Pernetti, M.; Galante, F. Development of Macro-Level Safety Performance Functions in the City of Naples. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, M.R.; Mauriello, F.; Sarkar, S.; Galante, F.; Scarano, A.; Montella, A. Parametric and Non-Parametric Analyses for Pedestrian Crash Severity Prediction in Great Britain. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rella Riccardi, M.; Mauriello, F.; Scarano, A.; Montella, A. Analysis of contributory factors of fatal pedestrian crashes by mixed logit model and association rules. Int. J. Inj. Contr. Saf. Promot. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quak, H.; De Koster, R. The Impacts of Time Access Restrictions and Vehicle Weight Restrictions on Food Retailers and the Environment. Eur. J. Transp. Infrastruct. Res. 2006, 6, 131–150. [Google Scholar]

- Muñuzuri, J.; Cortés, P.; Grosso, R.; Guadix, J. Selecting the location of minihubs for freight delivery in congested downtown areas. J. Comput. Sci. 2012, 3, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, C.; Montenon, A. Implementation and Impacts of Low Emission Zones on Freight Activities in Europe: Local Schemes Versus National Schemes. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgün, E.Z.; Monios, J.; Rye, T.; Fonzone, A. Influences on urban freight transport policy choice by local authorities. Transp. Policy 2019, 75, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussier, J.; Cucu, T.; Ion, L.; Breuil, D. Simulation of goods delivery process. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 913–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnik, T.; Marksel, M.; Luppino, G.; Bardi, A.; Božičnik, S. Review of policies and measures for sustainable and energy efficient urban transport. Energy 2018, 163, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindholm, M.; Behrends, S. Challenges in urban freight transport planning—A review in the Baltic Sea Region. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 22, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, J.; Hellström, D.; Pålsson, H. Framework of Last Mile Logistics Research: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.F.W.T.; Jin, X.; Srai, J.S. Consumer-driven e-commerce: A literature review, design framework, and research agenda on last-mile logistics models. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2018, 48, 308–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, F.N.; Cherrett, T.J.; Bektas, T.; Allen, J.; Martinez-Sykora, A.; Lamas-Fernandez, C.; Bates, O.; Cheliotis, K.; Friday, A.; Piecyk, M.; et al. Quantifying environmental and financial benefits of using porters and cycle couriers for last-mile parcel delivery. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 82, 102311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnik, T.; Farina, A.; Mencinger, M.; Lupi, M.; Božičnik, S. Dynamic management of loading bays for energy efficient urban freight deliveries. Energy 2018, 159, 916–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielis, R.; Valeri, E.; Rotaris, L. Performance Evaluation Methods for Urban Freight Distribution Chains: A Survey of the Literature. In Proceedings of the URBE conference, Rome, Italy, 1–2 October 2015; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Browne, M.; Gomez, M. The impact on urban distribution operations of upstream supply chain constraints. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2011, 41, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Weinzettel, J.; Bigano, A.; Källmén, A. Low carbon cities in 2050? GHG emissions of European cities using production-based and consumption-based emission accounting methods. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiba-Janiak, M. Key Success Factors for City Logistics from the Perspective of Various Groups of Stakeholders. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banister, D.; Hickman, R. Transport futures: Thinking the unthinkable. Transp. Policy 2013, 29, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, S.; Coimbra, R.; Costa, Á.; Baptista, P. Analyzing the Effects of Routing in the Sustainability of the City and on the Operational Efficiency of Urban Logistics Services. In Proceedings of the URBE conference, Rome, Italy, 1–2 October 2015; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schrampf, J. ILOS—Intelligent Freight Logistics in Urban Areas: Freight Routing Optimisation in Vienna; BESTFACT: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Certomà, C.; Corsini, F.; Rizzi, F. Crowdsourcing urban sustainability. Data, people and technologies in participatory governance. Futures 2014, 74, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buldeo Rai, H.; van Lier, T.; Meers, D.; Macharis, C. Improving urban freight transport sustainability: Policy assessment framework and case study. Res. Transp. Econ. 2017, 64, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, E.; Thompson, R.G.; Yamada, T. New Opportunities and Challenges for City Logistics. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducret, R. Parcel deliveries and urban logistics: Changes and challenges in the courier express and parcel sector in Europe—The French case. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 11, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Esposito, E. Environmental Sustainability and Energy-Efficient Supply Chain Management: A Review of Research Trends and Proposed Guidelines. Energies 2018, 11, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy, J.; Gesing, B.; Ward, J.; Noronha, J.; Bodenbenner, D.P. The Logistics Trend Radar, 5th ed.; DHL Customer Solutions and Innovation: Troisdorf, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gartner Hype Cycle for Supply Chain Strategy. Available online: https://blogs.gartner.com/power-of-the-profession-blog/hype-cycle-for-supply-chain-strategy-2021/ (accessed on 27 October 2022).

- Cardenas, I.D.; Vanelslander, T.; Dewulf, W. The E-Commerce Parcel Delivery Market: Developing a Typology from an Urban Logistics Perspective. In Proceedings of the URBE Conference, Rome, Italy, 1–2 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Viu-Roig, M.; Alvarez-Palau, E.J. The Impact of E-Commerce-Related Last-Mile Logistics on Cities: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, E.; Thompson, R.G.; Yamada, T. Recent Trends and Innovations in Modelling City Logistics. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shee, H.K.; Miah, S.J.; De Vass, T. Impact of smart logistics on smart city sustainable performance: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2021, 32, 821–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiore, G.M. Space for Cities: Satellite Applications Enhancing Quality of Life in Urban Areas. In Studies in Space Policy; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 22, pp. 251–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hensher, D.A.; Brewer, A.M. Developing a freight strategy: The use of a collaborative learning process to secure stakeholder input. Transp. Policy 2001, 8, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozzi, G.; Iannaccone, G.; Maltese, I.; Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E.; Lozzi, R. On-Demand Logistics: Solutions, Barriers, and Enablers. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardrat, M. Urban growth and freight transport: From sprawl to distension. J. Transp. Geogr. 2021, 91, 102979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.; Allen, J.; Leonardi, J. Evaluating the use of an urban consolidation centre and electric vehicles in central London. IATSS Res. 2011, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, P.; Macharis, C.; Mierlo, J.; Van Janjevic, M. Implementing an Urban Consolidation Centre: Involving Stakeholders in a Bottom-up Approach. In Proceedings of the URBE Conference, Rome, Italy, 1–2 October 2015; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dreischerf, A.J.; Buijs, P. How Urban Consolidation Centres affect distribution networks: An empirical investigation from the perspective of suppliers. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2022, 10, 518–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjevic, M.; Ndiaye, A.B. Development and Application of a Transferability Framework for Micro-consolidation Schemes in Urban Freight Transport. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 284–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balm, S.; Browne, M.; Leonardi, J.; Quak, H. Developing an Evaluation Framework for Innovative Urban and Interurban Freight Transport Solutions. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jedliński, M. The Idea of “FQP Projectability Semicircle” in Determining the Freight Quality Partnership Implementation Potential of the City. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 16, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lindholm, M. Successes and Failings of an Urban Freight Quality Partnership—The Story of the Gothenburg Local Freight Network. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 125, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijewska, K.; Jedliński, M.; Iwan, S. Ecological utility of FQP projects in the stakeholders’ opinion in the light of empirical studies based on the example of the city of Szczecin. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatta, V.; Marcucci, E.; Le Pira, M. Smart urban freight planning process: Integrating desk, living lab and modelling approaches in decision-making. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2017, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesterova, N.; Quak, H. A city logistics living lab: A methodological approach. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 16, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Cai, X.; Hall, N.G. Cost Allocation for Less-Than-Truckload Collaboration via Shipper Consortium. Transp. Sci. 2022, 56, 585–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordtømme, M.E.; Bjerkan, K.Y.; Sund, A.B. Barriers to urban freight policy implementation: The case of urban consolidation center in Oslo. Transp. Policy 2015, 44, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzzenenti, F.; Basosi, R. Modelling the rebound effect with network theory: An insight into the European freight transport sector. Energy 2017, 118, 272–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyarmathy, A.; Peszynski, K.; Young, L. Theoretical framework for a local, agile supply chain to create innovative product closer to end-user: Onshore-offshore debate. Oper. Supply Chain Manag. 2020, 13, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, L.; Mayer, A.; Matej, S.; Kalt, G.; Lauk, C.; Theurl, M.C.; Erb, K.-H. Regional self-sufficiency: A multi-dimensional analysis relating agricultural production and consumption in the European Union. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letnik, T.; Mencinger, M.; Bozicnik, S. Dynamic Management of Urban Last-Mile Deliveries. In City Logistics 2; John Wiley and Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schliwa, G.; Armitage, R.; Aziz, S.; Evans, J.; Rhoades, J. Sustainable city logistics—Making cargo cycles viable for urban freight transport. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2015, 15, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumboutsos, A.; Kapros, S.; Vanelslander, T. Green city logistics: Systems of Innovation to assess the potential of E-vehicles. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2014, 11, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahani, P.; Arantes, A.; Melo, S. A portfolio approach for optimal fleet replacement toward sustainable urban freight transportation. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 48, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Chen, K.; Hao, H.; Liu, Z. Challenges, Potential and Opportunities for Internal Combustion Engines in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, E. Concepts of City Logistics for Sustainable and Liveable Cities. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 151, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehmke, J.F.; Campbell, A.M.; Thomas, B.W. Data-driven approaches for emissions-minimized paths in urban areas. Comput. Oper. Res. 2016, 67, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, M. Advanced urban transport: Automation is on the way. IEEE Intell. Syst. 2007, 22, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorio, A.; Pinto, R.; Golini, R. Research in urban logistics: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forza, C. Survey research in operations management: A process-based perspective. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2002, 22, 152–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sax, L.J.; Gilmartin, S.K.; Bryant, A.N. Assessing response rates and nonresponse bias in web and paper surveys. Res. High. Educ. 2003, 44, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What Is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quak, H.; Lindholm, M.; Tavasszy, L.; Browne, M. From Freight Partnerships to City Logistics Living Labs—Giving Meaning to the Elusive Concept of Living Labs. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 12, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Woensel, L. Evidence for Policy-Making: Foresight-Based Scientific Advice|Think Tank|European Parliament. Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)690529 (accessed on 1 December 2022).

- Lin, C.; Choy, K.; Pang, G.; Ng, M.T.W. A data mining and optimization-based real-time mobile intelligent routing system for city logistics. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 8th International Conference on Industrial and Information Systems, Kandy, Sri Lanka, 17–20 December 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 156–161. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).