Abstract

International markets and digital technologies are considered among the factors affecting business innovation. The emergence and deployment of digital technologies in emerging markets increase the innovation potential in businesses. Companies with an entrepreneurial orientation also strengthen their innovation capabilities. The present study aimed to investigate the impact of international markets and new digital technologies on business innovation in emerging markets, and to estimate the mediating effect of entrepreneurial orientation on this relationship. The present research was applied research in terms of aim and descriptive survey in terms of data collection method and quantitative in terms of the type of collected data. A standard questionnaire was to collect data. The study’s statistical population consisted of all companies providing business services in Tehran, Iran. To analyse the data, the structural equation modelling method with partial least squares method and Smart PLS-3 Software was used. The results revealed that international markets and digital technologies are positively associated with innovation. They also revealed that when a company’s entrepreneurial orientation increases, the digital technologies and international markets will be more involved in mutual relationships.

1. Introduction

The globalisation of international markets has affected businesses over the last decades. Internationalisation is the process by which a company moves from operating in the domestic market to international markets. In addition, the development of digital technologies in businesses affects the expansion of international markets. International business activities can help companies acquire skills and competencies, which may make them more innovative [1]. The world’s economies also experience the process of globalisation, which has opened up more markets for businesses and entrepreneurs to offer their products, created more competition and innovation, and facilitated the process of achieving a higher level of product internationalisation [2]. Studies on emerging market companies have also emphasised the importance of using external knowledge resources to strengthen their internal innovation processes [3]. The importance of innovation in meeting the specific needs of emerging markets is a major source of growth for companies [4]. Accordingly, some studies have analysed the possibility of maximising the desired impact of a business model, while reducing the risks associated with technology development, so as to gain a deeper understanding of the factors determining sustainable and frugal innovations [5].

In this regard, frugal innovation in emerging markets focuses primarily on achieving much lower costs to meet resource-constrained consumer expectations, with a secondary focus on providing sufficient functions and characteristics to meet specific needs [6]. In addition, facilitating the formation of business model innovation influenced by digital technologies [7] has brought tangible and intangible benefits to businesses. It helps businesses make more profit and perform more successfully in delivering the expected results to the customer. However, non-adaptation to technology and rapid change in technology and its high cost impose serious damage to businesses [8]. Emerging markets are in economic, political, social, and demographic transitions from higher levels of volatility to stable institutional commitments. In this regard, innovation is essential for company survival and sustainable economic growth, and for expanding competitiveness in emerging markets (EMs) [9,10].

The first step was taken in the extant study to find the factors and impact of new digital technologies (NDTs) on the creation and increase of business innovation in emerging markets regarding the pandemic outbreak and the rapid growth of new digital technologies in majority markets. Because emerging markets are not separated from international markets, the present study examines the association between EM and international market (IM) based on the literature review, in which frugal innovation (FI) is defined with a higher concentration. According to findings, FI has emerged as a new method to serve consumers in developing countries. The mediating influence of entrepreneurial orientation was examined by considering the effect of two significant factors, including new digital technologies and international markets, on the formation of business innovation in emerging markets. EO can be considered as a key factor used to achieve sustainability, better performance, and survival of businesses in order to provide better solutions through differentiation to increase the acceptance of environmental complexities, because entrepreneurial orientation (EO) introduces new products, services, innovations, markets, and business models that have not existed before.

The present paper has been structured as follows: the next section provides a literature review and research background. Some concepts, including new digital technologies, international markets, entrepreneurial orientation, and business innovation, as well as emerging markets, are examined in this section. Moreover, a research framework is presented herein. Section 3 provides a methodology examining the effect of NDT, IM, and EO. The structural model is analysed based on the findings in this section. Finally, recommendations and research constraints are proposed.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Technologies

The term digital technologies refers to the set of intelligent and innovative technologies, such as big data analytics, IoT, and cloud computing, that make it possible to achieve connection, communication, and automation. Digital technologies enable companies to transform their current product or service model into an intelligent model and to adopt data-driven strategies to become more competitive [11]. The emergence and deployment of digital technology increase the innovation potential of businesses. In a world where companies operate in a highly competitive environment, they are increasingly under pressure to maximise their resources for innovation and to improve their performance. Therefore, companies that adopt innovation using digital technology can increase their performance and become innovative companies [12]. The use of digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, data mining, and IoT in companies leads to major business advances such as increased customer experience and interaction, simplification of operations, and business innovation [13]. Digital technologies, including information and communication technologies, have allowed some small businesses to combine independence and flexibility with larger domains and the accessibility of large companies in order to overcome some commitments [14].

In addition, due to the COVID-19 outbreak of 2020, which has had a significant impact on global behaviour, the simultaneous maturity of several key digital technologies in information and communication technology have progressed at an unprecedented speed, and each sector and industry has been affected by evolution and innovation. Digital technologies such as artificial intelligence, IoT, blockchain, and the development of fifth-generation wireless networks (G5) have created an effective ecosystem for identifying and using new opportunities in business and industry [15,16]. Digital technologies and platforms are transforming existing businesses and industries. New business models, new products, new forms of innovation, and transformation in established businesses to adapt their business operations and strategies in the digital era are among the implications of digital technologies for businesses and entrepreneurship [17]. The importance of digital technologies in the twenty-first century has been well perceived. The use of digital technology in business has been a determining factor in helping management, service, and production factors, increasing productivity and innovation [18]. Digital technologies can help small- and medium-sized enterprises achieve growth and innovation. Digital technologies play a major role in any business and facilitate cooperation among companies, information storage and data analysis, and bring innovation to the business [19]. The emergence of a diverse set of new and powerful digital technologies, platforms, and digital infrastructures has transformed innovation into extensive organisational and policy implications. The use of digital technologies has had a major impact on business innovation processes [20].

Researchers argue that digital technologies in business have three aspects: new ways of organising, achieving collective goals, and innovation in processes [21]. Digital technologies as an active element strengthen initiatives for businesses and have a major impact on innovation processes. Accordingly, the existing literature suggests that digital technologies can promote corporate innovation [20,22]. Digital technologies increase the range of opportunities to increase innovation. One of the most important of these is the collection of huge and diverse volumes of data. A large volume of data is generated while the end-user enjoys a digital product [23]. Big data enables companies’ digital platforms to develop complementary technologies and services. For example, user participation is an effective way for organisations to reduce innovation challenges [24]. Big data can be investigated in four management areas: big data and supply chain strategy, big data and customisation strategies, big data and strategic planning and strategic value creation, and big data and knowledge management [25]. Big data analytics capabilities represent vital tools for business competition in highly dynamic markets [26]. With the rapid popularity of big data analytics, academics and professionals are exploring the tools through which they can incorporate the changes these technologies make into their competitive strategies [27].

Companies can use the “data utilisation” strategy to enhance service innovation through an inter-system approach and analyse customers, examine behaviours, assess the needs independently by users online to increase new product development based on their expectations, and address the end-user or other ecosystem actors. In addition, by using the “sell data” strategy, they can increase the company’s value chain from an extroverted perspective [23,28]. Big data enables companies to generate insights that can help enhance their dynamic capabilities, which has a positive impact on the innovation enhancing capabilities [29,30]. Big data analysis has expanded to gain a competitive advantage among companies [31]. Artificial intelligence technology is also used as an effective enabler to increase the value of the business. Increasing attention to artificial intelligence in business is due to technological maturity. From a business point of view, artificial intelligence and data analysis systems systematise information and turn data into business decisions that facilitate corporate decision-making processes [32]. Artificial intelligence changes companies and the way they manage innovation management. Artificial intelligence changes the organisation to an innovative digital organisation by replacing human resources. Companies use artificial intelligence to innovate their processes [33].

In general, research suggests that cloud computing, Internet of Things (IoT), big data, data mining, artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain, and cyber-physical systems are digital technologies that could create winners and losers worldwide. They cause entrepreneurship, change, and innovation in enterprises, especially small enterprises [16,34]. Adoption of digital technologies leads to innovation and entrepreneurial orientation [35]. The use of digital technologies in business leads to entrepreneurial orientation in companies. Companies with entrepreneurial orientation are more flexible, have a high-risk acceptance, and perform more effectively [36].

2.2. International Markets

The rate of internationalisation is a key concept in the international trade literature for businesses, and is often seen as a rapid entry into foreign markets. The importance of this issue creates opportunities and pressures for domestic companies in emerging markets in order to improve their competitive position [37,38]. Previous studies suggest that businesses can use internal networks with internationally experienced partners to accelerate their internationalisation process or they can cooperate with foreign partners to strengthen technological innovation capabilities and to improve international performance [39,40]. Many studies also suggest that internal networks are located in local markets, so a practical option for businesses is to gain foreign market knowledge to coordinate and guide internationalisation activities [41,42].

Relational capital, union activity, and foreign market knowledge are considered key factors in creating international business performance and improving the development of technological innovation capability [39,40]. Internal networks are located in local markets, so they act as a practical option for businesses to gain foreign market knowledge so as to coordinate and direct internationalisation activities [41]. In the internationalisation of businesses, researchers have identified the significant role of foreign market knowledge [43], and stated that gaining such knowledge could accelerate entry into the international arena [44]. A lack of this knowledge leads to experimental decision making, which does not give a clear picture of the business decisions and leads to finding customers through weak links, trade fairs, and unwanted export orders, as well as to the experience of entering and re-entering the market. Acquiring knowledge leads to systematic and program-based decisions and stronger links [45,46]. Relational capital refers to intangible assets that can be acquired through the relationship between foreign companies and customers, and reflects an organisation’s ability to interact with a wide range of external stakeholders (such as customers, suppliers, competitors, and business and industrial associations) and leads to the implicit knowledge gained in these relationships [47,48].

Relational capital improves access to knowledge resources, builds trust in relationships with partners, and facilitates knowledge exchange by increasing the expectations and motivation for the value of knowledge [49,50]. Alliance proactiveness is defined as the willingness to find opportunities for strategic alliances with potentially valuable companies [51]. Relationships with external partners can have several benefits for companies. To achieve such benefits, companies must develop competencies and capabilities that increase their ability to create and absorb value in inter-organisational collaboration [52]. This orientation helps companies develop relationships with new partners through newly formed alliances. As companies can engage competitors through alliance proactiveness [53], alliance proactiveness is a key in business performance. As a basis for alliance management capability, it enables companies to respond more quickly to emerging opportunities and gain initial benefits [54], and can contact alliances before competitors or better predict the outcomes of alliances, which will lead to the success of alliances [55]. Thus, alliance leadership can be a key tool for creating a suitable environment for alliances among companies and for ensuring competitive advantage through providing sourcing [56]. It can also lead to superior market-based performance, and this impact is stronger for small companies and in unstable market environments [57].

2.3. Entrepreneurial Orientation

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO) is an organisational orientation towards new entry and value creation, and depicts the entrepreneurial decisions, methods, and actions used to create a competitive advantage [58]. EO is one of the most common and well-known research structures in the entrepreneurial literature. It is a strategic orientation implemented at the company level. It includes the methods adopted by the company to develop strategies, administrative philosophies, and behaviours that are inherently entrepreneurial [59]. EO can be observed in the processes of an organisation and the organisational environment. It is considered the key to achieving better performance and helps companies find better solutions through differentiation so as to increase the acceptance of environmental complexities. EO leads to introducing new products, services, innovations, markets, or business models that did not exist before [60]. Entrepreneurial orientation is a structure at the company level that seeks to actively attract and take advantage of every opportunity. It also results in creating organisational culture, practices related to the learning process, and the identification of new opportunities and innovation [61]. EO displays the strategies within the mental framework as well as the perspective on entrepreneurship, which is reflected in the company’s ongoing processes [62].

EO is considered a vital element for companies’ competitive advantage, growth, and performance. Market share, sales volume, and increased earnings indicate high growth, which is related to the entrepreneurial orientation of a company. Studies have indicated that EO leads to innovation, risk-taking, and business performance activity [63]. EO guides innovative strategies towards identifying and exploiting entrepreneurial opportunities, adopting innovative strategies to cope with crisis and environmental uncertainty in order to achieve the desired goals [64]. EO shows the company’s strategic orientation towards innovation and risk-taking. As a structure at an organisational level, it shows a forward-looking orientation that supports innovation and risk-taking behaviour. Studies have identified innovation as the heart of EO [65]. As a structure at the organisational level, it also shows a forward-looking orientation that supports innovation and risk-taking behaviour. EO results are not always positive and can lead to failure and even bankruptcy [66]. Companies tend to participate in entrepreneurship to maintain performance and survive in highly dynamic and competitive environments. A review of the existing literature suggests a relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and innovation [67]. EO is a crucial element for corporate innovation and affects corporate innovation performance [68].

2.4. Business Innovation in Emerging Markets

Innovations are usually created in developed countries and then transferred to developing countries [69]. However, innovation has expanded in resource-constrained environments, mainly in developing countries, in recent decades [70]. Product innovations for low-service customers in developing countries have been identified as an opportunity to create new markets. However, the current literature shows limited studies on the methods of developing innovation capabilities for these poor customers in developing countries [71]. Frugal innovation (FI) has emerged as a new way to serve consumers in developing countries [72]. FI has been defined in various ways and overlaps with other concepts, such as resource-constrained innovation and destructive innovation [71]. The quality and number of innovations developed in businesses from emerging countries is increasing dramatically. Frugal innovation (FI) represents a new entrepreneurial perspective in which resource-constrained small enterprises develop innovations for low-income customers in low-income countries. Frugal innovations also create new markets and contribute to the trade stability of products [72]. Frugal innovation focuses on developing lower-priced but well-performing products that meet the needs of consumers with limited purchasing power in resource-constrained emerging countries [73]. Innovations in desirable products with a high quality that meet the needs of consumers with resource limitations have created an extraordinary demand in emerging markets. Frugal innovations are mainly developed by local R&D subsidiaries of developed companies in emerging countries. A significant degree of independence for the R&D subsidiaries can facilitate the development of frugal innovation [74]. Frugal innovation should meet the basic needs of resource-constrained consumers by providing value improved at an affordable price (cost). Based on whether companies put their main emphasis on reducing costs or increasing value, we identified two types of frugal innovation, namely, cost innovation and valuable cost-effective innovation [6].

Previous studies have emphasised the systemic nature of market innovation. They suggest that a particular change in one market will probably lead to other changes in that market [75]. Markets are not essentially closed systems, but overlaps and interferences among different markets are seen commonly and frequently. Now, the question is how market innovation is done at the intersection of two (or more) existing markets. By combining elements from different markets, innovators may seek to change one of these markets or create a new market. Combined market innovation is increasingly common in the world of modular processes and market intersections, and both conceptual and empirical works are needed to explain such processes and help managers deal with them [76]. It is recommended that Western companies rely on emerging market partners when trying to develop frugal innovations for these emerging markets. This recommendation is based on the idea that emerging market consumer requirements may not be familiar to Western companies and that local developers may better understand local needs [77]. Thus, large Western companies often work with companies in developing countries to develop products to meet local needs [78], allowing them to combine advanced knowledge with local knowledge to develop appropriate solutions [77]. Frugal innovations enable new and unprecedented applications. Companies need to adjust value creation mechanisms to implement frugal business models [79].

A review of research in business innovation in emerging markets has formed the conceptual framework of the research. It indicates that in the formation of business innovation in emerging markets, there is probably a significant direct relationship between international market components and new digital technologies, and a mediating relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business innovation. Identifying the contribution of each component and item in the formation of business innovation in emerging markets can help market stakeholders, strategists, and researchers analyse the conditions and requirements of such markets. In addition, by reviewing the research background to identify the theoretical gap, it was found that due to the importance of the use of new digital technologies in the present and future, and the impact of emerging markets from international markets in previous studies, the relationship between these two components in the form of business innovation has not been considered in emerging markets. Thus, the present study investigates the impact of international markets and new digital technologies on business innovation in emerging markets.

3. Research Methodology and Measurement

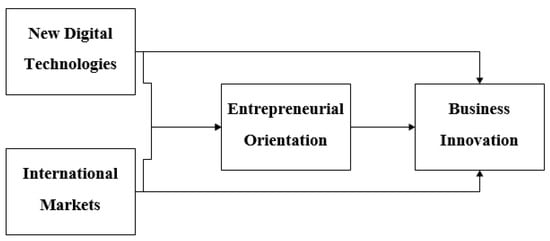

The present study examines the effects of international markets and new digital technologies on business innovation. The theoretical model presented in Figure 1 shows the interrelationships between framework structures by considering the above-mentioned hypotheses in the literature review. The present study is applied research in terms of aim, descriptive-survey in terms of the data collection methods, and quantitative in terms of the type of collected data. The structural equation model method with the partial least squares method and Smart PLS3 software were used to analyse the questionnaire data. The reason for using this method is the ability to analyse complex models with small volumes and a lack of sensitivity to the normal distribution of structures. The variable of new digital technologies and international markets as an independent variable was measured using the standard questionnaire of Hung and Shen (2021) with six questions, and the standard questionnaire of Zahoor and Al-Tabbaa (2021), and Ryu et al. (2021) with six questions; the variable of entrepreneurial orientation as a mediator variable was measured based on the standard questionnaire of Makhloufi et al. (2021) with four questions; and the variable of frugal innovation as a variable dependent was measured using the standard questionnaire of Quan Cai et al. (2019) with seven questions (Table 1). Selecting the appropriate respondents is a major step for obtaining accurate data to test the specific relationships between all relevant variables of the research model. Based on the Statistics Centre of Iran in 2021, the statistical population of the study included all 1206 companies providing business services in Tehran. To access the statistical sample, in 2021, the researcher collected their data electronically through an online questionnaire. As the statistical population was about 1206 active companies, the statistical sample of 292 companies was accepted through Cochran’s formula with a 5% error level. Finally, 300 analysable data were collected and used for analysis by the senior managers of these companies. In this study, a simple (convenience) random sampling method was used. Structures were measured using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from “1” meaning “strongly disagree” to “7” meaning “strongly agree”. Table 2 shows the demographic information of companies and respondents.

Figure 1.

Research framework based on research literature.

Table 1.

Experimental research background.

Table 2.

Information of respondents and companies.

4. Research Hypotheses

In light of the research discussed above, our underlying model was developed by categorising international markets, digital technologies, entrepreneurial orientation, and business innovation. Therefore, the hypotheses of the present study are as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Digital technology has a positive relationship with business innovation.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Digital technology has a positive relationship with entrepreneurial orientation.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

International markets have a positive relationship with business innovation.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

International markets have a positive relationship with entrepreneurial orientation.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

Entrepreneurial orientation has a positive relationship with business innovation.

5. Results

The present study uses the partial least squares structural equation model (PLS-SEM) to predict and evaluate measurement and structural models [81]. In this method, reliability was measured by two criteria: (1) Cronbach’s alpha and (2) Composite reliability (CR). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient indicates the ability of the questions to properly explain the relevant dimensions. The composite reliability coefficient also determines the degree of correlation between the questions of one dimension and another dimension for an adequate fit of the measurement models [82]. The results related to the reliability of the research questionnaire by the two mentioned criteria are shown in the table below.

The validity of the questionnaire was assessed by the convergent validity criterion using the partial least squares method. Convergent validity indicates the degree of ability of one-dimensional indices to explain that dimension. Convergent validity was examined by the AVE criterion (average variance extracted). If this criterion is above 0.5, the convergent validity of the measurement tool will be confirmed [82]. As shown in Table 3, all factor loads of items were above 0.70. In addition, the composite reliability of all structures was higher than 0.70. The AVE values were greater than 0.50, as suggested.

Table 3.

Internal consistency of variables (convergent validity and composite reliability).

To test the model and hypotheses, structural analysis method and Smart PLS software-3 were used. The results show that the average variance extracted for all structures is higher than 0.5, which confirms the validity of the structures. Cronbach’s alpha for structures was above 0.7, and the composite reliability was also higher than 0.7. Also, the reliability of the structures is confirmed. According to Table 4, divergent validity is confirmed, and the following results show that the research tool has acceptable validity and reliability.

Table 4.

Divergent validity measurement matrix.

Structural Model Analysis

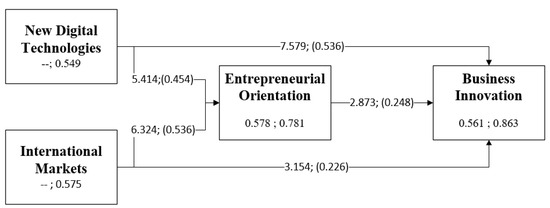

The structural path in Figure 2 and the results of Table 5 showed a positive and significant relationship between digital technology and business innovation (β1 = 0.536, t = 7.579, p < 0.001), indicating that H1 is supported. Also, the results showed a positive and significant relationship between digital technology and entrepreneurial orientation (β4 = 0.454, t = 5.414, p < 0.001), indicating that H2 is supported. Also, international markets have a positive and significant effect on business innovation (β3 = 0.226, t = 3.514, p < 0.001), meaning that H3 is supported. Also, the results showed a positive and significant relationship between international markets and entrepreneurial orientation (β4 = 0.536, t = 6.324, p < 0.001), indicating that H2 is supported. The path of entrepreneurial orientation in business innovation was positive and statistically significant (β2 = 0.248, t = 2.873, p < 0.001), so H5 hypothesis is supported.

Figure 2.

Research model in the modes of standard coefficients and significant numbers.

Table 5.

Communality and R2 values.

Model Fit: The general fit of the model was evaluated using the goodness of fit or the GOF index, which was calculated using communality and R2 indices (Table 5). The goodness of fit obtained was 0.681, which is higher than the acceptable minimum value of 0.36. Therefore, the research model has a good fit. According to Table 6, all cases indicated a strong fit for the research model, and its numerical value was more than 1.96. The results of the path analysis to test the research hypotheses are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Quantitative model fit evaluation.

6. Conclusions

Various factors necessitate business profitability in today’s business environment [83]. We aimed to identify the business innovation process regarding the high importance of sustainability and survival of the business and its vital role in the economic development of emerging markets. To do so, new digital technologies and the effect of international markets on these technologies were examined. Business sustainability is difficult and impossible without considering innovation. Therefore, the extant study was conducted to investigate the impact of international markets, new digital technologies, and entrepreneurial orientation on business innovation in emerging markets. Accordingly, two independent variables of IM and NDT, as well as the mediating variable of EO, were measured based on the factors extracted from the literature review, and then proposed hypotheses were tested. The findings indicated a significant effect of all three variables on the dependent variable (business innovation in emerging markets). The following are the results obtained from the confirmed hypotheses.

This study aimed to investigate the impact of international markets and new digital technologies on business innovation in emerging markets. The present study results indicate that international markets and new digital technologies can lead to the entrepreneurial orientation of businesses, and can lead to business innovation in emerging markets. Confirmation of the first hypothesis suggests that digital technology impacts business innovation. Digital technology provides new ways to organise economic activities, reduces costs and time associated with intermediaries, strengthens trust in the ecosystem of actors, and influences business innovation [84]. Digital technology results in changes in business processes, transformation, and innovation in business [85]. Confirmation of the second and fourth hypotheses suggests that entrepreneurial orientation strengthens the impact of digital technology and international markets on business innovation, and that entrepreneurial orientation positively impacts business innovation. Innovation, being active, and risk-taking are three main dimensions that create the entrepreneurial orientation [86]. Companies tend to participate in entrepreneurship to maintain performance and survival in highly dynamic and competitive environments.

The existing literature suggests a relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and innovation [67]. Entrepreneurial orientation is a key element for corporate innovation and affects the company’s innovation performance [68]. Confirmation of the third hypothesis suggests that internationalisation impacts business innovation. Early internationalisation of companies is a complex process that results from uncertain market conditions, entrepreneurial perspective, and strategic entry decisions that will shape innovations. The companies operating based on new technologies, such as new digital technologies, are more successful in achieving innovation [87,88]. These companies approach international business structures. In addition, gaining knowledge of specific regional aspects and customer behaviour is important in order to achieve success in foreign market needs in a modern business environment; existing big data support decisions, enhance performance, and contribute to innovative business models [89,90,91,92].

According to the obtained results, it is necessary to consider business innovation in emerging markets by improving entrepreneurial orientation, interacting with international markets, and acquiring new digital technologies in target countries. Such attention can contribute to business sustainability and survival in developing countries. The following recommendations are presented based on the research findings.

6.1. Recommendation

It is recommended that business managers and companies review the operational processes and practices in the area of the business model considering the impact of new digital technologies and international markets on business innovation in emerging markets, and take advantage of new digital technologies and pay attention to international markets in these processes. In addition, given the impact of entrepreneurial orientation on the creation of business innovation, it is recommended that managers identify the entrepreneurial capability of employees and use the entrepreneurial opportunities to create innovation for the company. It is also recommended that researchers examine the relationship of digital technologies and international markets with business model innovation by using other mediating variables such as knowledge management, market capability, and so on. In addition, it is recommended to conduct similar research in this area due to the lack of studies on the effective factors and the implications of paying attention to business innovation.

6.2. Limitations

Any researcher may face constraints and limitations. The limitation of the present paper was the newness of business innovation in the studied country and the different perceptions of innovation concepts among Iranian business owners compared to global standard concepts [93]. Because the data were collected from Iran, caution must be taken in generalising the results to all emerging markets while interacting with international markets. If this model is tested on other emerging markets, the external validity of results will be increased.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.-P.D. and A.S.; methodology, L.-P.D. and A.S.; software, S.M. and M.H.; validation, S.M. and M.H.; formal analysis, L.-P.D., A.S., S.M. and M.H.; investigation, L.-P.D., A.S., S.M. and M.H.; writing—original draft preparation, L.-P.D., A.S., S.M. and M.H.; writing—review and editing, L.-P.D., A.S., S.M. and M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ding, Q.; Khattak, S.I.; Ahmad, M. Towards sustainable production and consumption: Assessing the impact of energy productivity and eco-innovation on consumption-based carbon dioxide emissions (CCO2) in G-7 nations. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 254–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, M.S.; Méndez, M.T.; Galindo, M.Á. Innovation, internationalisation and business-growth expectations among entrepreneurs in the services sector. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badir, Y.F.; Frank, B.; Bogers, M. Employee-level open innovation in emerging markets: Linking internal, external, and managerial resources. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 891–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M.; Ernst, H.; Dubiel, A. From the special issue editors: Innovations for and from emerging markets. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2015, 32, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Conesa, I.; Soto-Acosta, P.; Carayannis, E.G. On the path towards open innovation: Assessing the role of knowledge management capability and environmental dynamism in SMEs. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1367–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W. Innovating with limited resources: The antecedents and consequences of frugal innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loock, M. Unlocking the value of digitalisation for the European energy transition: A typology of innovative business models. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 69, 101740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhe, B.O.; Hamid, N.A. The Impact of Digital Technology, Digital Capability and Digital Innovation on Small Business Performance. Res. Manag. Technol. Bus. 2021, 2, 499–509. [Google Scholar]

- Na, K. The Effect of On-the-Job Training and Education Level of Employees on Innovation in Emerging Markets. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkizhinov, B.; Gorenskaia, E.; Nazarov, D.; Klarin, A. Entrepreneurship in emerging markets: Mapping the scholarship and suggesting future research directions. Int. J. Emerg. Mark. 2021, 16, 1404–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y. Digital twin in industry: State-of-the-art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astuti, E.S.; Sanawiri, B.; Iqbal, M. Attributes Of Innovation, Digital Technology and Their Impact on SME Performance in Indonesia. Int. J. Entrep. 2020, 24, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, M.; Kruschwitz, N.; Bonnet, D.; Welch, M. Embracing digital technology: A new strategic imperative. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2014, 55, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista, R.; Guerrieri, P.; Meliciani, V. The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2014, 23, 802–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, D.; Zhu, L.; Benwell, B.; Yan, Z. Digital technology use during COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 3, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-P.O.; Liu, H.; Ting, D.S.J.; Jeon, S.; Chan, R.V.P.; Kim, J.E.; Sim, D.A.; Thomas, P.B.M.; Lin, H.; Chen, Y.; et al. Digital technology, tele-medicine and artificial intelligence in ophthalmology: A global perspective. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2021, 82, 100900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuschke, D.; Mason, C.; Syrett, S. Digital futures of small businesses and entrepreneurial opportunity. Futures 2021, 128, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.T.; Chen, J.S. How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 20, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D. Understanding the relationship between ICT and education means exploring innovation and change. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2006, 11, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S.; Lyytinen, K.; Majchrzak, A.; Song, M. Digital Innovation Management: Reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Q. 2017, 41, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstegen, L.; Houkes, W.; Reymen, I. Configuring collective digital-technology usage in dynamic and complex design practices. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nambisan, S. Information technology and product/service innovation: A brief assessment and some suggestions for future research. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2013, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabucchi, D.; Buganza, T.; Dell’Era, C.; Pellizzoni, E. Exploring the inbound and outbound strategies enabled by user generated big data: Evidence from leading smartphone applications. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2018, 27, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindström, D.; Kowalkowski, C.; Sandberg, E. Enabling service innovation: A dynamic capabilities approach. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1063–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Marzi, G.; Demi, S.; Faraoni, M. The big data-business strategy interconnection: A grand challenge for knowledge management. A review and future perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 1157–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Demi, S.; Magrini, A.; Marzi, G.; Papa, A. Exploring the impact of big data analytics capabilities on business model innovation: The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Boura, M.; Lekakos, G.; Krogstie, J. Big data analytics capabilities and innovation: The mediating role of dynamic capabilities and moderating effect of the environment. Br. J. Manag. 2019, 30, 272–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.H.; Abu, N.H.; Abdul Rahim, M.K.I. Relationship of Big Data Analytics Capability and Product Innovation Performance using SmartPLS 3.2. 6: Hierarchical Component Modelling in PLSSEM. Int. J. Supply Chain. Manag. (IJSCM) 2018, 7, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Makhloufi, L.; Laghouag, A.; Sahli, A.A.; Belaid, F. Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Innovation Capability: The Mediating Role of Absorptive Capability and Organizational Learning Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, L.P.; Tajpour, M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Hosseini, E.; Zolfaghari, M. The impact of entrepreneurial education on technology-based enterprises development: The mediating role of motivation. Adm. Sci. 2021, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Luo, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wei, Y. Big data analysis adaptation and enterprises’ competitive advantages: The perspective of dynamic capability and resource-based theories. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2019, 31, 406–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestino, A.; De Mauro, A. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence in Business: Implications, Applications and Methods. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefner, N.; Wincent, J.; Parida, V.; Gassmann, O. Artificial intelligence and innovation management: A review, framework, and research agenda. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. Artificial Intelligence and Business Innovation. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on E-Commerce and Internet Technology (ECIT), Zhangjiajie, China, 22 April 2020; pp. 237–240. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Gupta, S.D.; Upadhyay, P. Technology adoption and entrepreneurial orientation for rural women: Evidence from India. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2020, 160, 120236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Octavia, A.; Indrawijaya, S.; Sriayudha, Y.; Hasbullah, H. Impact on E-Commerce Adoption on Entrepreneurial Orientation and Market Orientation in Business Performance of SMEs. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2020, 10, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorodnichenko, Y.; Svejnar, J.; Terrell, K. Globalization and innovation in emerging markets. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2010, 2, 194–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V.; Dana, L.-P.; Han, M.; Welpe, I. Internationalisation of SMEs: European comparative studies. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2007, 4, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, D.; Baek, K.H.; Yoon, J. Open Innovation with relational capital, technological innovation capital, and international performance in SMEs. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, N.; Al-Tabbaa, O. Post-entry internationalisation speed of SMEs: The role of relational mechanisms and foreign market knowledge. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milanov, H.; Fernhaber, S.A. When do domestic alliances help ventures abroad? Direct and moderating effects from a learning perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2014, 29, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Gilbert, B.A.; Oviatt, B.M. Effects of alliances, time, and network cohesion on the initiation of foreign sales by new ventures. Strateg. Manag. J. 2011, 32, 424–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J.C.; Barbero, J.L.; Sapienza, H.J. Knowledge acquisition, learning, and the initial pace of internationalisation. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casillas, J.C.; Moreno-Menéndez, A.M. Speed of the internationalisation process: The role of diversity and depth in experiential learning. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2014, 45, 85–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vissak, T.; Francioni, B.; Freeman, S. Foreign market entries, exits and re-entries: The role of knowledge, network relationships and decision-making logic. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviatt, B.M.; McDougall, P.P. Defining international entrepreneurship and modeling the speed of internationalisation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2005, 29, 537–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J. Measuring customer capital. Strat. Leadersh. 2000, 28, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejati, M.; Salamzadeh, Y.; Salamzadeh, A. Ecological purchase behaviour: Insights from a Middle Eastern country. Int. J. Environ. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 10, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, J.; Ghoshal, S. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organisational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 242–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setini, M.; Yasa, N.N.K.; Supartha, I.W.G.; Giantari, I.K.; Rajiani, I. The passway of women entrepreneurship: Starting from social capital with open innovation, through to knowledge sharing and innovative performance. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, M.; Urbano, D.; Salamzadeh, A. Evolving Entrepreneurial Universities: Experiences and Challenges in the Middle Eastern Context. In Handbook on the Entrepreneurial University; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Leischnig, A.; Geigenmüller, A. When does alliance proactiveness matter to market performance? A comparative case analysis. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2018, 74, 79–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothaermel, F.T.; Boeker, W. Old technology meets new technology: Complementarities, similarities, and alliance formation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Meyer, K.E. Alliance proactiveness and firm performance in an emerging economy. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 82, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, S.; Kandemir, D.; Eng, T.-Y. The role of horizontal and vertical new product alliances in responsive and proactive market orientations and performance of industrial manufacturing firms. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 64, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlin, C.; Ellegaard, C. Conceptualizing competition and rivalry in a networking business market. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 51, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.B.; Echambadi, R.A.; Harrison, J.S. Alliance entrepreneurship and firm market performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting high-impact entrepreneurial orientation research: Some suggested guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 43, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaher, A.T.Q.; Ali, K.A.M. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation on innovation performance: The mediation role of learning orientation on Kuwait SME. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3811–3820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Rumman, A.; AI Shraah, A.; Al-Madi, F.; Alfalah, T. Entrepreneurial networks, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance of small and medium enterprises: Are dynamic capabilities the missing link? J. Innov. Entrep. 2021, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Entrepreneurial orientation-as-experimentation and firm performance: The enabling role of absorptive capacity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1739–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, R.A. Entrepreneurial orientation and the fate of corporate acquisitions. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meekaewkunchorn, N.; Szczepańska-Woszczyna, K.; Muangmee, C.; Kassakorn, N.; Khalid, B. Entrepreneurial orientation and SME performance: The mediating role of learning orientation. Econ. Sociol. 2021, 14, 294–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Ronteau, S. Towards an entrepreneurial theory of practice; emerging ideas for emerging economies. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2017, 9, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.; Gupta, V.K.; Marino, L.; Shirokova, G. Entrepreneurial orientation: International, global and cross-cultural research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2019, 37, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemand, T.; Rigtering, J.C.; Kallmünzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Maalaoui, A. Digitalization in the financial industry: A contingency approach of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic vision on digitalisation. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troise, C.; Dana, L.P.; Tani, M.; Lee, K.Y. Social Media and Entrepreneurship: Exploring the Impact of Social Media Use of Start-Ups on Their Entrepreneurial Orientation and Opportunities; J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhoushi, M.; Sadati, A.; Delavari, H.; Mehdivand, M.; Mihandost, R. Entrepreneurial orientation and innovation performance: The mediating role of knowledge management. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; McGahan, A.M.; Prabhu, J. Innovation for inclusive growth: Towards a theoretical framework and a research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 661–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, N.; Grottke, M.; Mishra, S.; Brem, A. A systematic literature review of constraint-based innovations: State of the art and future perspectives. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2016, 64, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Fujimoto, T. Frugal innovation and design changes expanding the cost-performance frontier: A Schumpeterian approach. Res. Policy 2019, 48, 1016–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation: Conception, development, diffusion, and outcome. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boons, F.; Lüdeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeschky, M.; Widenmayer, B.; Gassmann, O. Frugal innovation in emerging markets. Res. Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, D.; Kjellberg, H. How users shape markets. Mark. Theory 2016, 16, 445–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, J.; Braga, V.; Correia, A.; Salamzadeh, A. Unboxing organisational complexity: How does it affect business performance during the COVID-19 pandemic? J. Entrepr. Pub. Policy. 2021, 10, 424–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altmann, P.; Engberg, R. Frugal Innovation and Knowledge Transferability: Innovation for Emerging Markets Using Home-Based R & D Western firms aiming to develop products for emerging markets may face knowledge transfer barriers that favor a home-based approach to frugal innovation. Res. Technol. Manag. 2016, 59, 48–55. [Google Scholar]

- Immelt, J.R.; Govindarajan, V.; Trimble, C. How GE is disrupting itself. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Winterhalter, S.; Zeschky, M.B.; Neumann, L.; Gassmann, O. Business models for frugal innovation in emerging markets: The case of the medical device and laboratory equipment industry. Technovation 2017, 66, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Baghdadi, E.N.; Alrub, A.A.; Rjoub, H. Sustainable Business Model and Corporate Performance: The Mediating Role of Sustainable Orientation and Management Accounting Control in the United Arab Emirates. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulland, J. Use of partial least squares (PLS) in strategic management research: A review of four recent studies. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gomez, H.; Guerola-Navarro, V.; Vicedo, P. Is It Possible to Manage the Product Recovery Processes in an ERP? Analysis of Functional Needs. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4380. [Google Scholar]

- Weking, J.; Mandalenakis, M.; Hein, A.; Hermes, S.; Böhm, M.; Krcmar, H. The impact of blockchain technology on business models—A taxonomy and archetypal patterns. Electron. Mark. 2020, 30, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Radovic Markovic, M.; Masjed, S.M. The effect of media convergence on exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. AD-Minister 2019, 34, 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, H.I.; Luka, J.; Daniel, M. Entrepreneurship Orientation, Innovation and Firm Performance in North-East Nigeria. Nigerian. J. Account. Financ. 2021, 13, 123–149. [Google Scholar]

- Baier-Fuentes, H.; Guerrero, M.; Amorós, J.E. Does triple helix collaboration matter for the early internationalisation of technology-based firms in emerging Economies? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 163, 120439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Sinisi, C.I.; Serbanescu, L.; Păunescu, L.M. Towards sustainable digital innovation of SMEs from the developing countries in the context of the digital economy and frugal environment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behse, M. Data assets in digital firms and ICTs: How data strategy shapes the process of internationalization. Master’s Thesis, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden, June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Azimi, M.A.; Kirby, D.A. Social entrepreneurship education in higher education: Insights from a developing country. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2013, 20, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamzadeh, A.; Tajpour, M.; Hosseini, E. Corporate entrepreneurship in University of Tehran: Does human resources management matter? Int. J. Knowl. Based Dev. 2019, 10, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajpour, M.; Hosseini, E.; Salamzadeh, A. The effect of innovation components on organisational performance: Case of the governorate of Golestan Province. Int. J. Public Sect. Perform. Manag. 2020, 6, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).