Abstract

This paper examines the effect of local government debt (LGD) and real estate investment on corporate investment. It finds that the increase in LGD and real estate investment leads to a decline in corporate investment and that the crowding-out effect is mitigated by the interaction of LGD and real estate investment. The effects are channeled by raising corporate costs and reducing corporate financing. This impact is more pronounced for firms in eastern regions and nonresource-based cities, large and private firms.

1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of local government debt (LGD) in China has been of great concern for both academic researchers and policymakers [1], especially since the global financial crisis in 2008. In the wake of the crisis, the State Council of China launched a four-trillion-yuan (≈USD 586 billion) stimulus package, which was mostly spent on infrastructure projects and largely financed by local government financing vehicles (LGFVs) [2], most of which are based on LGD [3,4,5]. The stimulus package and the mounting debt burden of local governments in China were two sides of the same coin. On the one hand, it promoted investment in infrastructure and real estate and then economic growth [6,7]. On the other hand, the stimulus package also increased LGD and then crowded out nonfinancial investment (hereafter referred to as “corporate investment”) by reducing the financing of firms, especially that of private firms [8,9], which also arouse the concern for the continuing systemic risk of hidden debt [10].

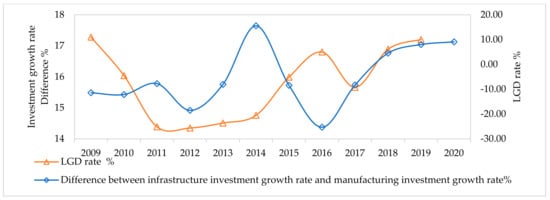

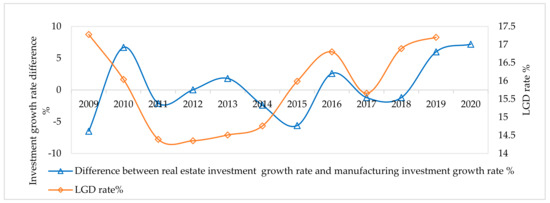

Specifically, LGD is mostly used for constructing urban infrastructure and utility services to provide a sound investment environment and attract human capital inflow [1,11,12], which in turn leads to a boom in the real estate market and fast growth of real estate investment. As observed in Figure 1, there has been a lagged positive correlation between LGD and the growth rate difference between investment in infrastructure and real estate since 2014. Similarly, as shown in Figure 2, a lagged positive correlation between LGD and the growth rate difference between investment in manufacturing and real estate can also be observed. This indicates that the return gap between investment in real estate and manufacturing is likely to cause an outflow of capital from the real economy [13] and then increase the difference between the LGD rate and investment growth rate. Hence, it seems that LGD and real estate may have both a crowding-in effect and a crowding-out effect on corporate investment. What would be the compound effect of them?

Figure 1.

Difference between the LGD rate and difference between the growth rates of infrastructure investment and manufacturing investment (%). Source: iFinD Financial Data.

Figure 2.

Difference between the LGD rate and difference between the growth rates of real estate investment and manufacturing investment (%). Source: iFinD Financial Data.

Regarding the relationship between LGD, real estate investment and corporate investment, there are three strands of literature. The first strand of literature proposes that LGD has a positive impact on the real estate market. LGD is mainly used to meet the needs of industrialization and urbanization [14], which leads to an increase in housing demand and an increase in housing prices, triggering a rapid expansion of real estate investment [15].

The second strand holds that the rapid expansion of real estate investment, triggered by high housing prices, has a crowding-out effect and a credit misallocation effect on the real economy, which intensifies financing constraints on nonreal estate sectors and significantly undermines the improvement of total factor productivity in cities [16]. It is noted that there is a collateral channel through which the real estate market boom can have a positive impact on the firm’s financing capability, thus alleviating corporate financing constraints [17].

The third strand argues that the geographical segmentation and interest rate restrictions of China’s credit market can help identify channels through which LGD crowds out private investment by tightening financing constraints [8]. The local government’s preferential access to capital undermines the overall efficiency of capital allocation, and the expansion of LGD crowds out the investments of listed companies by reducing their short-term and operating liabilities [2,18]. Other studies point out that LGD expansion may improve the infrastructure and investment environment, thus improving the marginal return on capital, encouraging corporate investment, and boosting the long-term sustained growth of the regional economy. In other words, LGD crowds in corporate investment [19].

Most of these studies analyzed the effects of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment separately and have not formed a complete theoretical framework linking LGD, the real estate market and infrastructure investment together to study the relationships among them from a comprehensive perspective. Unlike the previous studies, the possible contribution of this paper is to incorporate the three into a framework and examines the compound impact of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment using data from 295 prefecture-level cities (hereafter referred to as “cities”) and firms. In addition, this study investigates the impact during different periods by sorting out the evolution of local government debt policy, so as to covers a longer time range.

2. Related Literature and Hypothesis

2.1. LGD and Real Estate Investment

Most of the literature attributes the main causes of China’s real estate market volatility to urbanization, technological progress, loose monetary policy or land policy, migration, or excessive real estate investment [20]. Some studies have noted the impact of LGD on the real estate market. LGD is mostly financed by short- and medium-term loans from financial institutions. However, most LGD is used to invest in long-term infrastructure projects. The maturity mismatch between investment and financing means that the majority of the maturing debt will most likely be serviced from debt roll-over or new borrowing and that the local government is highly dependent on proceeds from land transfer. Under such circumstances, LGD risks are closely linked with real estate risks.

Local governments rely on revenues, taxes and fees obtained or collected from land transfer and the real estate sector to repay their debts [21]. A study by Han and Kung [15] indicates that as the debt service pressure compels local governments to find alternative sources of revenue to meet their public finance obligations, local governments began to shift their focus to the real estate sector, which had the effect of motivating regional economic growth while driving up housing prices. Chen et al. [22] conclude that excessive LGD borrowing is associated with a boom in the real estate market. LGD is heavily invested in public goods and infrastructure to meet the needs of urbanization and industrialization. Industrialization elevates the economic development of the region, and urbanization attracts an inflow of people. When the demand for housing exceeds the supply, the subsequent rise in housing prices further encourages real estate investment. Hence, hypothesis 1 is proposed as follows.

Hypothesis 1.

LGD boosts real estate investment.

2.2. LGD and Corporate Investment

Studies of LGD and corporate investment mainly focus on testing the crowding-out or crowding-in effects from different perspectives. Some scholars believe that there is some substitution effect between LGD and corporate investment [23,24,25]. Cong et al. [6] found that the expansion of LGD had an unpredictable negative impact on credit allocation and even on economic development. Based on empirical results, Cravo et al. [26] found that LGD, private investment and public expenditure have an inverted U-shaped relationship. That is, when LGD is low, private investment and public expenditure increase; conversely, when LGD is high, private investment is crowded out, and public spending decreases. A study by Wu et al. [27] indicates that LGDs may crowd out private investment and reduce economic efficiency in the short and long run. Fan [28] found that issuing government bonds in developing countries crowds out corporate bond issues. Scholars have explored the relationship between the two based on firm-level evidence in China and found that commercial banks, as the main suppliers of credit, were influenced by local governments, which obtained large amounts of funds through administrative intervention and land mortgages. New credit resources were disproportionally allocated to inefficient state-owned enterprises (SOEs), collectively worsening credit misallocation in China [29,30].

Although easy access to credit local governments enjoy plays an essential role in many aspects, such as infrastructure construction and economic development, it also worsens the overall allocation efficiency of the capital market [31]. In addition, the long repayment cycle of infrastructure projects exerts no repayment pressure on those officials who are responsible for borrowing the debt during their tenure. Even if there is a debt service gap, it is still possible to acquire bridging loans from other banks, which leads to an even longer occupation of bank credit. Liang et al. [9] found through empirical tests that LGD expansion significantly crowded out the borrowing of SOEs and non-SOEs alike. This crowding-out effect mainly occurs in upstream firms rather than downstream ones, indicating that the local government is more likely to provide implicit guarantees to the former than the latter.

Some scholars argue that there is both a competing and a complementary relationship between public investment and private investment [19] because tax revenue competition and the risk of capital outflow compel local governments to pursue high-growth policies and strive to attract business by constructing an enabling investment environment. Government debt can increase spending on public goods, improve infrastructure and the investment environment, increase the marginal return on capital, and increase aggregate social demand and business investment opportunities, thus promoting business investment [32]. A study by Cravo et al. [26] indicates that LGD can increase local financial resources and public spending and attract private investment to accelerate regional economic growth. Hence, hypothesis 2 is proposed as follows.

Hypothesis 2.

LGD has an impact on corporate investment.

Hypothesis 2a.

LGD has a crowding-out effect on corporate investment.

Hypothesis 2b.

LGD has a crowding-in effect on corporate investment.

2.3. Real Estate Investment and Corporate Investment

The ultimate impact of real estate investment on corporate investment depends on the magnitude of the wealth effect versus the crowding-out effect [33]. If the wealth effect dominates, then the real estate investment boom will promote corporate investment; otherwise, the boom will suppress corporate investment. Depending on the wealth effect, a rise in real estate investment triggered by asset bubbles can ease financing constraints and promote investment by increasing the collateral value of corporate assets [17]. The reality in China is that a system of financial repression prevails due to the lagging development of the financial market and the dual repression pattern of the indirect financing system dominated by a monopolistic banking structure [34]. Due to the existence of such financial repression, asset bubbles exert a liquidity effect to some extent and have a crowding-in effect on corporate investment. According to capital structure theory, a sustained rise in house prices will substantially increase the value of corporate collateral (land-, plant-, and property-owning firms), thus increasing the financing ability of firms, and commercial banks in particular will instinctively extend credit to real estate firms, pushing them to expand corporate investment.

The profit margin gap between the real estate industry and the manufacturing industry drives credit and capital flow to the real estate industry [13]. This causes a relative shortage of capital, an increase in capital costs in the manufacturing industry, and crowding-out investments in the manufacturing industry and other nonfinancial industries [35,36]. Zheng et al. [37] state that real estate investment promotes the continuous improvement of urban infrastructure and that local governments further increase infrastructure investment, thus weakening financial support for firms [28,38]. Similarly, some scholars argue that the rapid development of the real estate market not only crowds out credit in the real economy but also leads to overinvestment in the real estate market and its inefficiency, which increases financing constraints on nonreal estate sectors and thus leads to credit resource mismatch [22]. Hypothesis 3 is thus proposed.

Hypothesis 3.

Real estate investment has an impact on corporate investment.

Hypothesis 3a.

Real estate investment increases corporate investment due to the wealth effect.

Hypothesis 3b.

Real estate investment suppresses corporate investment due to the crowding-out effect.

2.4. The Compound Effect of LGD and Real Estate Investment on Corporate Investment

Studies have been conducted on the effects of either LGD or the real estate market on corporate investment. There is no complete theoretical framework linking the two to study their impact pathways from a macro perspective. Based on the abovementioned literature, it is reasonable to conclude that the sources and repayment of LGD depend on real estate collateral and land transfer revenue, which further contributes to the boom of the real estate industry. Both the financial resources taken up by borrowing and absorbed by the real estate industry increase simultaneously, while the resources for the real economy continue to decrease. As more borrowing is invested in the public sector and the real estate market, the crowding-out effect on enterprise investment increases. As a result, the development scope of the corporate sector is squeezed even more. The study of Ma et al. [39] indicates that public investment fueled by LGD and real estate investment are two important paths through which LGD crowds out investment in the real economy but that the crowding-out effect is mostly affected by the expansion of LGD. Hou and Tian [40] argue that LGD and investment property demand damage the vitality of businesses through the crowding-out effect and the drain on financial resources, exacerbating the economic downturn and undermining people’s wellbeing. With the accumulation of LGD and the differentiation of regional real estate markets, local debt risks and real estate bubbles are intertwined and affect each other, which could easily trigger systemic risks.

However, from a comprehensive perspective, the crowding-out effect can be mitigated, by the wealth effect of the increase of real estate investment and the growth of local economy driving by the expansion of LGD. Specifically, more high-quality infrastructure and public services are provided with the expansion of LGD, which helps promote the rising of local housing price and the revenue of land sales for the local governments, as well as the growth of local economy. Then, the enterprise investment gets improved because of a better economic environment.

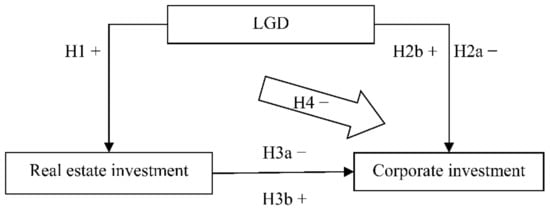

Hence, Hypothesis 4 is proposed and all the four hypotheses are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Hypotheses of this study.

Hypothesis 4.

LGD and real estate investment have a compound crowding-out effect on corporate investment.

3. Data, Variables and Empirical Model

3.1. Data

Given the institutional changes described in Appendix A and the available data, this paper mainly focuses on the analysis of LGD from 2009 to 2019. To ensure that the data are as authentic and robust as possible, the estimates and data collection of this paper are divided into the following two periods.

- (1)

- The data covering the period 2009 to 2013 are mainly based on the estimation method of Huang et al. [8] and are calculated using the data of urban investment bonds and bank loans.

- (2)

- The LGD data covering the period 2014 to 2019 are mainly based on the GO bonds and revenue bonds by region published by the Ministry of Finance; the sum of these two types of bonds is assumed to basically match the amount of LGD for which the local government is liable to repay.

The average value of local government debt ratio in 2013 and 2014 are compared, which indicates that the continuity and comparability of the data are verified. A description of the local government debt ratio is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary for variables: Debtgdp.

The LGD data are obtained from the iFinD database, and the city-level economic data are obtained from the China City Statistical Yearbook, China Statistical Yearbook for Regional Economy, China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook, China Finance Yearbook, iFinD database, and Wind database. We removed the data of municipalities directly under the central government and observations with key variables missing. Ultimately, we collected data on a total of 298 cities.

The firm-level data in this paper are obtained from the iFinD database from 2009 to 2019, but we removed the following samples: ST, *ST and PT firms; financial firms, such as banks, insurance and securities; firms with key variables missing; observations of total assets, fixed assets, or current assets less than or equal to 0; those with abnormal registration; and those with profit margins lower than −100% or higher than 99%. Ultimately, we collected data on a total of 3054 firms.

We categorize these firms into two types: SOEs (including wholly state-owned, state-owned joint ventures and collective firms) and private firms (excluding foreign-funded firms). The continuous variables are winsorized at the 1% level, and observations with missing key variables are removed. Finally, the firm-level data are merged with the city-level data. Due to the limited number of cities that have available LGD data, there are a large number of missing values after matching the firm and city panel data, and the full sample contains a total of 15,061 observations.

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Main Variables

We use corporate investment as the dependent variable. Following Kang et al. [41], corporate investment is measured by dividing the amount of corporate investment by total assets. The core independent variable is the LGD to GDP ratio of cities.

Following Xu [42] and Peng et al. [43], real estate investment is measured by the residential development investment to GDP ratio. We take the natural logarithm as the independent variable (invest_resid).

3.2.2. Control Variables

The control variables at the city level include: housing price (the average sales price of commercial housing) [20]; GDP per capita (taken as a logarithm), population density (taken as a logarithm); urbanization rate (the share of nonagricultural employment in total employment); regional public service level (proxied by per capita fiscal expenditure); tertiary industry output to GDP ratio; the loan balance of financial institutions to GDP ratio; financial institutions’ loan balance to deposit ratio; fixed asset investment to GDP ratio; and public fiscal expenditure to GDP ratio. These variables are used to separate the influence of factors such as urban economic development level, industrial structure, financial resources, investment dependence and financial development [44,45,46].

The control variables at the firm level are: total assets (taken as a logarithm); the age of the firm; current assets ratio (the current assets to total assets ratio); profit ratio (the total profits to industrial sales ratio); and sales growth rate. These variables are used to separate the influence of factors such as firms’ scale, age, asset structure and operating conditions on corporate investment decisions. A description of the main variables is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Variable description.

3.3. Empirical Model

The first question this paper addresses is whether LGD drives up interest rates and thus crowds out corporate investment, since geographic segmentation of China’s credit market leads to LGD having a localized impact. The following equation is adopted in the benchmark regression.

where is corporate investment, is the leverage ratio of local governments, and is the control variable, which includes annual fixed effects, city fixed effects and random disturbance terms.

Second, the following Equation (2) is set to test the hypotheses by combining the expected impact of real estate investment on corporate investment based on the wealth effect or crowding-out effect and the correlation between LGD and real estate investment.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Main Results

The benchmark results of the impact of LGD on real estate investment are reported in Table 3. No control variables are added in column (1), and the results show that for every 1% increase in LGD, real estate investment increases by 0.08%, and the regression coefficients are all significantly positive at the 0.01 significance level. Column (2) shows the result of adding macroeconomic variables to column (1) and performs a cluster regression at the year level. The coefficients of LGD are all significantly positive at the 0.05 significance level. The regression results indicate that LGD will lead to real estate investment growth, verifying Hypothesis 1.

Table 3.

LGD and real estate investment.

The regression results in Table 4 support Hypotheses 2a and 3a. Column (1) shows that corporate investment and LGD are negatively correlated, and the regression coefficient is significant at the 0.05 significance level. Column (2) shows that corporate investment and real estate investment are negatively correlated but not statistically significant. Based on columns (1) and (2), columns (3) and (4), respectively, add the interaction term between LGD and real estate investment and the interaction term between LGD, real estate investment and the year dummy variable (“0” indicates before 2014, otherwise it is “1”). The regression coefficient of the interaction of columns (3) and (4) is significantly positive at the 0.1 and 0.05 significance levels, respectively, reflecting that LGD and real estate investment have a compound mitigation effect on the crowding-out effect. The regression coefficient of the interaction term with the year dummy in column (4) is significantly negative, indicating that the compound mitigation effect of LGD and real estate investment has been weakened since 2014, which is consistent with the correlation between the LGD rate and the difference between the growth rate of real estate investment and corporate investment. The results show that, on the one hand, LGD, with its preferential access to the capital market, deteriorates the overall allocation efficiency of the capital market and crowds out corporate investment and that the crowding-out effect of real estate investment on corporate credit is based on the typical “resource mismatch” found in the financial market. On the other hand, from a comprehensive perspective, the compound effect of real estate investment and local government debt on corporate investment mitigates the crowding-out effect.

Table 4.

Local government leveraging, real estate investment and corporate investment.

4.2. Further Analysis

4.2.1. Possible Mechanisms

Through which intermediate mechanisms do LGD and real estate investment affect corporate investment? First, can local governments regulate the crowding-out effects of LGD and real estate investment? We further examine the impact of local government capacity on the impact of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment. We use local government capacity (focusing on their economic management capacity) as the moderating variable for the validation analysis. Following Hou and Song [47], local government capacity (edc) is expressed as the regional GDP to fiscal expenditure ratio. If we examine the features of the debtor, we find that local governments in China vary greatly in terms of their capacity for economic management, and that this variation in capacity affects the external macroeconomic environment as well as the role of firm characteristics in corporate investment.

Therefore, this paper introduces the interaction variables of local government capacity with LGD and real estate investment (debt_edc, invest_edc and debt_invest_edc) to further analyze the moderating role of local governments in crowding out corporate investment. Table 5 presents the regression results of the moderating effect. From the regression results in Table 5, it can be seen that local government capacity (edc) plays a positive moderating role in LGD and real estate investment.

Table 5.

Intermediate mechanisms of the impact of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment.

Columns (1) to (3) in Panel A show the moderating role of local governments’ economic management capacity. The results show that the interaction variable coefficients of local governments’ economic management capacity with local government leverage and real estate investment are 16.924 and 82.712 and 10.458 and 171.716, respectively, and are significant at least at the 0.05 significance level, except for column (2). Generally, the stronger the economic management capacity of the local government is, the weaker the crowding-out effect on corporate investment.

Second, we further explore the mechanisms underlying the crowding-out effect of LGD and real estate investment. Based on previous analysis, this paper argues that the increased financial costs of the firm may be a major reason for declining corporate investment. Local government bonds are usually more secure than corporate bonds, thus attracting investors away from corporate bonds. Therefore, firms have to raise their bond yields or even borrow from informal sources, which leads to an increase in the cost of corporate financing, thus crowding out corporate investment. Excessive investment in real estate distorts resource allocation and causes inflation, which leads to an increase in investment and production costs to the detriment of SMEs [48]. The rapid development of the real estate market likewise crowds out corporate credit funds, and during the period under study, capital was increasingly concentrated in the real estate sector in China, fueling asset bubbles and further squeezing corporate investment [49].

Thus, this paper further analyzes the relationship between LGD, real estate investment and corporate financial costs. Columns (1) and (2) in Panel B show that LGD and real estate investment reduce corporate financial costs, respectively, but they are not statistically significant. The results displayed in column (3) show that LGD and real estate investment significantly increase corporate financial costs, with regression coefficients of 0.044 and 0.256, respectively, which are significant at least at the 0.05 level. The regression coefficient of the interaction term in column (3) is −0.549, which is significantly negative at the 0.01 level, reflecting that an increase in LGD and real estate investment will have a compound mitigation effect on corporate costs, which corresponds to the compound mitigation effect on the crowding-out effect discussed earlier.

Are there any other pathways through which LGD and real estate investment crowd out corporate investment? LGD is mainly used for infrastructure construction involving huge capital requirements and a long construction cycle; in a sense, bank credit is held hostage to these projects. In addition, the long repayment cycle of infrastructure projects exerts no repayment pressure on those officials responsible for borrowing the debt during their tenure. Even if there is a debt service gap, it is still possible to acquire bridging loans from other banks, which leads to an even longer occupation of bank credit. As mentioned above, the concentration of capital brought about by the booming real estate market contributes to asset bubbles, which also crowds out corporate credit resources.

To test this hypothesis, we analyze the relationship between LGD, real estate investment and corporate indebtedness. Column (3) of Panel C in Table 5 shows that LGD significantly reduces corporate indebtedness with a regression coefficient of −0.144, which is significantly negative at the 0.05 level. The regression coefficient of real estate investment is also negative but not statistically significant. The regression coefficient of the interaction term is 1.338, which is significantly positive at the 0.05 level, reflecting that LGD and real estate investment have a compound positive effect on corporate leverage, which corresponds to the compound mitigation effect on the crowding-out effect discussed earlier.

Overall, the results of the pathway analysis on the negative correlation between LGD and real estate investment on the one hand, and the corporate leverage ratio on the other, verify that when the bank lends more to the local government, it lends less to firms, which negatively affects corporate investment.

4.2.2. Heterogeneity Analysis

The relationship between LGD, real estate investment and corporate investment has been verified above, and the impact mechanisms have been explored. Next, we explore the heterogeneous crowding-out effects due to the significant differences in the macroeconomic environment and intrinsic characteristics of firms in different regions of China. We empirically investigated the effects of the local government leverage rate and real estate investment on corporate investment in eastern and central regions (there are too few samples from the western region to conduct an analysis), on the corporate investment of resource-based cities and nonresource-based cities (classified according to the definition in the National Sustainable Development Plan for Resource-based Cities), of large enterprises and MSMEs (classified according to the Standard for Classification of Small and Medium-sized Enterprises), of private enterprises and SOEs (classified according to the actual controller of the enterprises), and of enterprises of positive growth and negative growth (based on the growth rate of business revenue).

Table 6 shows the test results of the heterogeneity effect. Columns (1) to (10) are analyzed based on Equation (2), and the results show that the crowding-out effect of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment is mainly concentrated in the eastern region, firms located in nonresource-based cities, large firms and private firms. Specifically, the regression coefficients of LGD on the investment of the abovementioned types of firms are −0.197, −0.196, −0.244 and −0.170, respectively, which are significant at least at the 0.1 significance level. The regression coefficients of real estate investment are −0.893, −0.856, −0.882 and −0.727, which are significant at least at the 0.1 significance level. The regression coefficients of the interaction term of the two are 2.041, 1.967, 2.675 and 1.690, which are significant at least at the 0.05 significance level.

Table 6.

Heterogeneity analysis of the impact of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment.

This suggests that the possible reasons are that the cities in the eastern region have a higher level of economic development and more investment in infrastructure in recent years, so the urbanization level is higher and the real estate market develops faster. Due to the lack of sustainable development resources, nonresource-based cities have a greater dependence on fixed asset resources, such as infrastructure construction and real estate. Large firms tend to borrow more money. In addition, the property right of enterprises is also an important factor influencing the crowding-out effect of investment. The business operation mode of government debt and real estate investment complementing each other can stimulate the investment vitality of private enterprises [9].

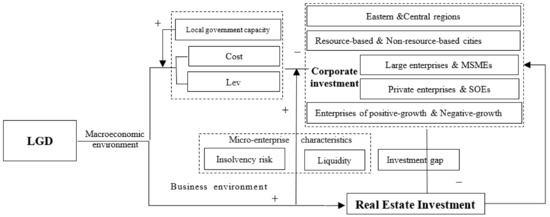

Based on the heterogeneity test in the previous section, we analyze the crowding-out/crowding-in effect of LGD and real estate investment in the full sample as well as in different types of firms. Table 7 analyzes the impact of LGD and real estate investment on firms’ risk and liquidity. The results in columns (1) to (11) show that LGD crowds out investment mainly by increasing the risk of insolvency and reducing the liquidity of the firm; however, real estate investment plays the opposite role. Overall, the increase in the value of collateral assets will enhance the liquidity of the firm. To avoid the risk of bankruptcy, management tends to allocate those resources generated by the increase in the value of collateral assets to the bubble industries that are less risky and can yield higher profits in the short term, such as the real estate industry [50], which will enhance the liquidity of the firm and reduce its bankruptcy risk. Therefore, real estate investment can mitigate the crowding-out effect of LGD. Base on the empirical results, the empirical mechanism diagram is illustrated in Figure 4.

Table 7.

Heterogeneity analysis of the formation paths of the compound effects of LGD and real estate investment.

Figure 4.

The empirical mechanism diagram.

4.3. Robustness Checks

To check the robustness of the findings, we conduct robustness checks in the following aspects. The estimated results are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Robustness tests.

First, debt stock is increasing over time (as is the case in China), and cumulative debt stock may have an expanding negative effect [51]; real estate residential investment has a significant time lag and plays an important role in the investment network [43]. Given the above two facts, we lag the previous independent variables by two periods for robustness testing.

Second, we use two GMM estimations for the dynamic panel [52]: the difference-GMM; and the system-GMM. The estimation results of the system-GMM are consistent with those of the difference-GMM and are statistically significant. This indicates the robustness of our regression results.

Third, based on the principle and logic of constructing the instrumental variable, it is necessary to find an exogenous variable that is only intrinsically related to LGD but not directly related to corporate investment as the corresponding instrumental variable. It is believed that the supply of urban construction land as a proportion of urban area (%) in Chinese cities is a suitable instrumental variable for LGD. This is because the proportion, which is closely related to LGD to an extent, represents the fiscal capacity of the local government, but it does not have a direct impact on corporate investment. Additionally, drawing on other relevant studies, the first-order lagged term of real estate investment is used as an instrumental variable of real estate investment [53]. Finally, we test whether the crowding out effect and compound mitigating effect are consistent with the above when focusing on manufacturing, non-manufacturing and non-real estate industries, so as to verify the universality of macro thinking. The estimated results are presented in Table 9. We can see that there is always a significant crowding-out effect of LGD and real estate investment on corporate investment. In addition, the compound mitigating effect remains significant, and these results are consistent with those of the benchmark regression.

Table 9.

Robustness testing in different industries.

5. Conclusions and Implications

Based on theoretical and empirical studies, this paper finds that LGD and real estate investment reduce the overall allocation efficiency of the capital market and crowd out corporate investment and that these two factors have a compound mitigating effect on the crowding-out effect. The results of the mechanism analyses show that local government capacity enhancement will mitigate the crowding-out effect on corporate investment, while the main transmission paths of the crowding-out effect on corporate investment cause corporate costs to rise, constraining financing channels and reducing corporate leverage. Heterogeneity analysis finds that the above crowding-out effect and the compound mitigation effect are more pronounced for firms in eastern regions, nonresource-based cities, and large firms and private firms. In addition, LGD crowds out corporate investment mainly by enhancing bankruptcy risk and reducing the liquidity of firms in the above categories, but real estate investment plays the opposite role, so it mitigates the crowding-out effect of LGD.

Based on the above findings, the following policy implications are provided.

- (1)

- Establishing a supporting assessment matrix to motivate local governments to pursue high-quality development; giving full play to the government’s regulatory role and its role in leveraging private investment; stimulating the vitality of private investment; and promoting stable growth of corporate investment.

- (2)

- Maintaining a reasonable rate of growth in real estate investment and giving full play to its key role in optimizing the supply structure. The positive interaction between the local government and the real estate market should be strengthened so that more funds from the financial sector flow into the real economy and form an endogenous growth mechanism for market-led investment.

- (3)

- Facing the slacking-off of the local government, rising corporate costs, difficult and expensive financing, and other prominent problems, it is imperative to stimulate the enthusiasm of local governments and firms and to establish a multilevel capital market to improve the business environment. The government should improve the market mechanism, support all entities to innovate, and create positive externalities for businesses.

Author Contributions

Translation, software and data analysis, X.L. and J.D.; Conceptualization, resource preparation, data analysis, and writing—original draft, G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) funded programs: Emergency Management Program “Real estate market and financial risk prevention” (Grant No. 71850014); Key Program “Research on the formation, transmission, and prevention of financial risks in the real estate sector in the context of the big data age” (Grant No. 71532013); General Program “Aging, decision making on housing rent vs purchase and household financial asset allocation” (Grant No. 71974180); Special Program “Research on the fundamental system development of PPP” (Grant No. 71950009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

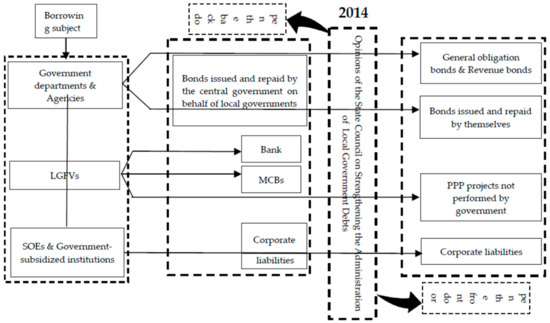

To better understand the development of LGD, we introduce the institutional background of LGD in China and a two-stage accounting model of LGD with 2014 as the watershed year in the appendix.

Appendix A.1. Institutional Evolution

There are two milestones in the development of LGD in China. The first is the introduction of the Budget Law in 1994, which gave rise to LGFVs. The Budget Law stipulates that local governments are not allowed to issue local government bonds (LGBs). However, municipalities are allowed to borrow through LGFVs. The second milestone was the revision of the Budget Law in 2014, which allowed provincial governments to issue bonds in accordance with the law and detailed strict regulations on the subject, use, scale, procedure, supervision and accountability of bond issuance.

On 2 October 2014, Opinions of the State Council on Strengthening the Administration of Local Government Debts (known as the “No. 43 Document”) was issued as a supporting document of the new Budget Law. It prohibits local governments from providing guarantees for LGFV bond issuance or issuing bonds through LGFVs. It also requires local governments to restructure their existing debt and replace it with municipal bonds. The implementation of the new Budget Law provides a legal basis for local governments to issue bonds and requires better debt management with a debt cap and other measures. The new Budget Law also laid the legal basis for financial information disclosure.

Appendix A.2. Categories of LGD

LGD refers to debts assumed by local governments (local governments refer to the general name of the governmental organization that manages administrative affairs of a country). Its full name is local people’s government. In China, it refers to people’s governments at all levels relative to the central people’s government, including the people’s governments established by provinces, municipalities directly under the Central Government, counties, cities, municipal districts, townships, ethnic townships and towns at all levels of government as debtors. Zhong and Lu [54] categorized LGD into “broad-sense LGD” and “narrow-sense LGD” according to the subject scope. Narrow-sense LGD refers to debt borrowed directly by the local government and backed by the “full faith and credit” of the local government as part of local government on-budget liabilities to perform its functions and meet the needs of local economic and social development. Broad-sense LGD refers to debts assumed by local governments as public entities, in addition to traditional legitimate or contract-binding loans and bonds, including debts of local governments and institutions at all levels, local state-owned enterprises and implicit debts, such as pensions. Broad-sense LGD constitutes off-budget borrowing and mainly includes bank loans, BT (build-and-transfer), bond loans, trust loans, borrowing from other organizations and individuals, and other types of borrowing.

Local government-backed debt refers to debts directly borrowed, defaulted on, or supported with guarantees, buybacks or other credit by local governments (including government departments and agencies), government-subsidized institutions, public utilities, LGFVs, etc., for public welfare projects. According to the Audit Results of Nationwide Governmental Debts released by the National Audit Office of China at the end of 2013, local government-backed debt is categorized into three types: governmental responsibility for debt payment, governmental guarantee responsibility and governmental rescue responsibility. All three types are required to be incorporated into budget management, and it is clear that “government-backed debts” do not include implicit debt.

The term “implicit LGD” first appeared at a Central Political Bureau meeting held on 24 July 2017. On paper, so-called “implicit LGD” is not part of local government-backed debt but rather a product of noncompliant operations (e.g., guarantees, issuance of commitment letters, etc.) or disguised debt (pseudo-public–private partnership, debts packaged as government purchases, etc.). At present, there is no uniform standard or defining criteria for implicit LGD, and it is unclear how to dispose of it in the future and whether it can be transformed into explicit LGD through a new round of screening.

LGBs are bonds issued by local governments. Specifically, they refer to bonds issued and repaid by the central government on behalf of local governments between 2009 and 2014 (there are also some pilot programs where bonds were issued by local governments themselves and repaid by either the central government or by themselves) and bonds issued and repaid by local governments themselves since 2015. LGBs have gone through three stages, as shown in Table A1.

Table A1.

Three stages of LGBs.

Table A1.

Three stages of LGBs.

| Stage | Issuing Scope | Issuer | Obligor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Provincial governments (including the governments of municipalities listed separately in the state plan) | Ministry of Finance | Ministry of Finance |

| 2 | Six pilot regions: Shanghai, Guangdong, Zhejiang, Shenzhen, Jiangsu and Shandong | The six pilot regions | Ministry of Finance |

| 3 | Ten pilot regions: Shanghai, Beijing, Guangdong, Jiangsu, Shandong, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Ningxia, Shenzhen and Qingdao | The 10 pilot regions | The 10 pilot regions |

Municipal corporate bonds (MCBs) refer to debt financing instruments issued by qualified (i.e., eligible for standardized business) LGFVs. They include corporate bonds, debt financing instruments for nonfinancial enterprises in the interbank bond market (medium-term notes, short-term financing, asset-backed notes, principal protected notes, etc.), private placement bonds and asset securitization. As the data of MCBs are openly available (e.g., from the Wind database), the term is frequently used in LGD studies.

The new Budget Law explicitly categorizes LGBs into general obligation (GO) bonds and revenue bonds. GO bonds are issued by local governments to relieve financial constraints or address temporary funding shortfalls. Usually, they are secured by the region’s fiscal revenue, so defaults are rare. The funds raised are often used to build highways, airports, parks, municipal facilities and other public welfare projects, which generally do not generate revenue. GO bonds are payable from and managed under the general public budget (that is, revenue mainly collected from taxes and spent on social, security and local institutional improvements).

Revenue bonds are issued by the governments of provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities directly under the central government (including the governments of municipalities listed separately in the state plan) for public welfare projects with specific revenue streams. Revenue bonds are payable from earmarked government funds or proceeds from the bonds. Revenue bonds are managed under the government’s fund budget. The Notice on the Pilot Local Government Revenue Bonds with Self-balancing Revenue and Financing, issued in 2017, stipulates that pilot revenue bonds are to be repaid by earmarked government funds or fees collected from the users of the services associated with the project financed through the bond issue. The Notice specifies the sources of funds for debt servicing of the projects. It also explores the “closed” operation and management of different types of local government revenue bonds, which is conducive to locking the risk of revenue bonds and effectively protecting the legitimate rights and interests of investors.

Public–private partnership (PPP) is a project operation model involving collaboration between a government agency and a private-sector company that can be used to finance public infrastructure. PPP was introduced in China in 2013. Over the years, it has achieved remarkable results in strengthening weak links, improving quality and efficiency in the public sector, bridging the investment and financing gap in the infrastructure sector, and encouraging the development of intensive and innovative industries. The central government of China requires that the operating subsidies of PPP projects be fully linked to an evaluation of their performance. The government shall not be an “unconditional obligor” of PPP debts, and standardized PPP contracts signed according to the law will not increase LGD. If the government were to fail to fulfill its expenditure responsibility, in part or in whole, then this would constitute a default of government expenditure responsibility; however, this is not an implicit LGD. However, if the government has no extra financial resources, then fulfilling the expenditure responsibility of a new PPP poses a threat to financial sustainability and the government’s credibility. Under such circumstances, the government would not have the ability to fulfill the PPP contract and would not meet the legal attributes of the contracted expenditure responsibility; therefore, such a case would constitute implicit LGD. In addition, if the total amount of PPP projects were to get out of control or the expenditure responsibility fail to match the current financial capacity leading to delayed payment or default and PPP project failure, then the government would have to bail the project out. Such cases would add to implicit LGD [24]. In summary, this paper defines “implicit LGD caused by PPPs” as being the result of government default due to the mismatch between expenditure responsibility and current financial resources.

Many local governments set up LGFVs to raise funds, largely because the reform of the tax-sharing system and the restrictions on LGDs imposed by the former Budget Law limited local governments’ financial resources. The bonds issued by LGFVs in the name of corporate bonds add to implicit LGD. To control the scale of implicit LGD and prevent systemic risks, the central government issued details in the No. 43 Document, which for the first time proposed to “repair the open channel, block the back channel, and give local governments the authority to borrow in accordance with the law”. The No. 43 Document specified that to “distinguish the responsibilities of the government and the business, local governments shall not borrow via LGFVs, and corporate debt shall not be repaid by local governments. He who borrows shall repay”. Since the No. 43 Document was issued, a series of policies have been adopted to “open the front door” and “block the back door”. In addition to putting strict controls on implicit LGD in place to avoid irrational borrowing, the Chinese government has also stepped up its countercyclical adjustment efforts to draw a clear line between the government and the market, encourage market-based financing in accordance with the law, increase effective investment, promote a virtuous cycle for economic growth, and enhance the quality and sustainability of economic and social development.

Figure A1 presents the impact of the changes introduced by the No. 43 Document on the accounting of LGD. The nature of the LGD entirely changed over the five years to 2014. Before 2009, only the “back door” was open, and LGD was mainly borrowed through LGFVs, which included debts for which local governments had repayment responsibilities and debts for which they had guarantee and rescue responsibilities. From 2009 to 2014, both the “front door” and the “back door” were open; while pilot LGBs were extensively issued, corporate bonds issued by LGFVs were increasing rapidly. After 2014, the “front door” remained open, while the “back door” was gradually closed. The issuance of the No. 43 Document, therefore, made 2014 a watershed year.

Figure A1.

Schematic diagram of the accounting basis for LGD under different institutions.

This overview of the institutional changes and categories of LGD provides theoretical support for a comprehensive and deep understanding of the LGD issue and for scientific calculation of LGD in China. However, for a long time, local governments in China did not have legitimate debt raising claims and could not explicitly incorporate financial deficits, so accurate statistics were not available (Zhong and Lu, 2015) [54]. Existing studies are mainly based on estimates or substitute indicators; this is insufficient for accurately understanding and managing LGD and does not provide a solid scientific basis for future research. We need accurate and authoritative data to inform studies of LGD.

References

- He, Z.; Jia, G. Rethinking China’s local government debts in the frame of modern money theory. J. Post Keynes. Econ. 2020, 43, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.-E.; Hsieh, C.-T.; Song, Z. The Long Shadow of China’s Fiscal Expansion. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2016, 2, 129–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Fan, J.; Ye, C.; Zhang, Q. Government debt, land financing and distributive justice in China. Urban Stud. 2020, 58, 2329–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, J. Land financing and economic growth: Evidence from Chinese counties. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 50, 218–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, K.Y. China’s Infrastructure Investment Boom and Local Debt Crisis. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2011, 52, 686–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, Z.; Liu, C. The financing of local government in China: Stimulus loan wanes and shadow banking waxes. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 137, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Peng, Y. The treatment-effect estimation: A case study of the 2008 economic stimulus package of China. J. Econom. 2015, 188, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pagano, M.; Panizza, U. Local Crowding-Out in China. J. Financ. 2020, 75, 2855–2898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Shi, K.; Wang, L.; Xu, J. Local Government Debt and Firm Leverage: Evidence from China. Asian Econ. Policy Rev. 2017, 12, 210–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Yao, H.; Mear, F. New development: Is China’s local government debt problem getting better or worse? Public Money Manag. 2021, 41, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, N.; Yao, S. How Does Low-Density Urbanization Reduce the Financial Sustainability of Chinese Cities? A Debt Perspective. Land 2021, 10, 981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Tian, Y.; Lei, A.; Boadu, F.; Ren, Z. The Effect of Local Government Debt on Regional Economic Growth in China: A Nonlinear Relationship Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yao, L.Z. Will High House Prices Inhibit the Investment Scale of Private Enterprises. J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 44, 88–100. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhong, S.; Wu, L. Land Financialization, Uncoordinated Development of Population Urbanization and Land Urbanization, and Economic Growth: Evidence from China. Land 2020, 9, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Kung, J.K.-S. Fiscal incentives and policy choices of local governments: Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2015, 116, 3340–3356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleck, A.; Liu, X. Credit expansion and credit misallocation. J. Monet. Econ. 2018, 94, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaney, T.; Sraer, D.; Thesmar, D. The Collateral Channel: How Real Estate Shocks Affect Corporate Investment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2012, 102, 2381–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.W.; Gao, H.; Ponticelli, J.; Yang, X. Credit Allocation Under Economic Stimulus: Evidence from China. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2019, 32, 3412–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J.; Lind, R.C. Uncertainty and the Evaluation of Public Investment Decisions. Am. Econ. Rev. 1970, 60, 403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, C.; Li, Q.; Ouyang, M. Property taxes and home prices: A tale of two cities. J. Econom. 2014, 180, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. Fiscal Decentralization and Revenue/Expenditure Disparities in China. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2010, 51, 744–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yang, B.; Qi, T.X. The Impact of House Price Volatility on the Scale of Local Debt—An Empirical Study Based on Provincial Data. Public Financ. Res. 2016, 6, 86–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Graham, J.R.; Leary, M.T.; Roberts, M.R. A century of capital structure: The leveraging of corporate America. J. Financ. Econ. 2015, 118, 658–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.R.; Leary, M.T.; Roberts, M.R. The Leveraging of Corporate America: A Long-Run Perspective on Changes in Capital Structure. J. Appl. Corp. Financ. 2016, 28, 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Vissing-Jorgensen, A. The Aggregate Demand for Treasury Debt. J. Political Econ. 2012, 120, 233–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravo, T.A.; Becker, B.; Gourlay, A. Regional Growth and SMEs in Brazil: A Spatial Panel Approach. Reg. Stud. 2015, 49, 1995–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wang, B. Local Government Debt, Factor Misallocation and Regional Economic Performance in China. China World Econ. 2018, 26, 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.Y. The Root of Land Finance: Fiscal Pressure or Investment Impulse. China Ind. Econ. 2015, 6, 18–31. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, S.; Wang, X. Excess liquidity and credit misallocation: Evidence from China. China Econ. J. 2017, 10, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Woo, W.T. Zombie Firms and the Crowding-Out of Private Investment in China. Asian Econ. Pap. 2016, 15, 32–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lin, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, F. China’s Growing Government Debt in a Computable Overlapping Generations Model. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2018, 23, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, D.A. Does public capital crowd out private capital? J. Monet. Econ. 1989, 24, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Hui, E.C.M.; Jia, S. How does housing price affect consumption in China: Wealth effect or substitution effect? Cities 2017, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.; Yao, Y. The Rule of Law, Financial Development and Economic Growth under Financial Repression. Soc. Sci. China 2004, 1, 42–55, 206. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Miao, J.; Wang, P. Sectoral bubbles, misallocation, and endogenous growth. J. Math. Econ. 2014, 53, 153–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Liu, P.; Han, G. The Influence of Housing Investment on Urban Innovation: An Empirical Analysis Based on City-Level Panel Data in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Kahn, M.E.; Liu, H. Towards a system of open cities in China: Home prices, FDI flows and air quality in 35 major cities. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2010, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.Q.; Sun, W.Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, Y. To Make Money with Land, and to Support Land with Money’ Research on the Investment and Financing Model of Urban Construction with Chinese Characteristics. Econ. Res. J. 2014, 49, 14–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.C.; Hua, X.; Han, Y.H. How does Local Government Debt Squeeze out the Credit Financing of Entity Enterprises?–Microevidence from Chinese Industrial Enterprises. Stud. Int. Financ. 2020, 5, 3–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Hou, W.F.; Tian, X.M. Local Debt Expenditure, Investment Real Estate Demand and Macroeconomic Fluctuations. Stat. Decis. 2021, 37, 33–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kang, M.; Khaksari, S.; Nam, K. Corporate investment, short-term return reversal, and stock liquidity. J. Financ. Mark. 2018, 39, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Is there causality from investment for real estate to carbon emission in China: A cointegration empirical study. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2011, 5, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peng, Z.; Yu, Z.; Nong, H. Inter-Type Investment Connectedness: A New Perspective on China’s Booming Real Estate Market. Glob. Econ. Rev. 2020, 49, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borck, R.; Fossen, F.M.; Freier, R.; Martin, T. Race to the debt trap?—Spatial econometric evidence on debt in German municipalities. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2015, 53, 20–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Levine, R. Finance and Inequality: Theory and Evidence. Annu. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2009, 1, 287–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Financial development and economic growth: Recent evidence from China. J. Comp. Econ. 2012, 40, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.Y.; Song, L.R. Fiscal Decentralization, Local Government Actions and High-quality Economic Development. Inq. Econ. Issues 2020, 9, 33–44. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lai, P. China’s Excessive Investment. China World Econ. 2008, 16, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, F.H.; Fu, C.Y. Structural Evolution, Induced Failure and Efficiency Compensation. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 4–19. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. A New Measure of Government Intervention-based on the Perspective of the Ultimate Controller’s Investment Portfolio. J. Financ. Res. 2016, 9, 145–160. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Li, N. Research on the Multiplier and Double Crowding Effect of the Rising Local Debt Intensity. Manag. World 2021, 37, 51–66, 160, 165. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Arellano, M.; Bover, O. Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.C.; Huang, X.J.; Shen, J. Real Estate Investment and Financial Efficiency-regional Differences in Financial Resources. J. Financ. Res. 2018, 8, 51–68. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.Y.; Lu, M. How Fiscal Transfer Payments Affect Local Government Debt? J. Financ. Res. 2015, 9, 1–16. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).