Abstract

Purpose: The purpose of the research work is to investigate whether micro-level corporate social responsibility (MCSR) plays a positive role in forming and promoting organizational social sustainability (SOS). It further investigates how each of the four dimensions of MCSR are linked with organizational social sustainability. Additionally, the study aims at studying MSCR and SOS within a context where such kinds of studies are scant. Methodology: A quantitative, cross sectional, and explanatory design was used to conduct the study. A sample 516 respondents were drawn from five hospitals in Bahrain through random sampling technique, and 441 questionnaires complete from all aspects were included for analysis. Different reliability and validity tests were carried out to check the goodness of the data. Inferential statistics, including regression analysis, were applied to test the hypotheses. Findings: Data analysis showed a significant relationship between micro-level CSR and organizational social sustainability. Ethical dimensions of MCSR proved to be the most dominant influencer of SOS, followed by environmental dimension of MCSR. However, the relationships of philanthropic and economic MCSR with SOS were statistically significant, but the intensity of relationships was weak. Originality: It is the seminal work in terms of investigating the relationship between MSCR and SOS which, to the best of the researcher’s knowledge, has not been investigated before. Testing the relationship of each dimension of MCSR with SOS is another original value, in addition to the existing body of literature.

1. Introduction

Investing in sustainability is not optional in the present era, and the healthcare sectors in developing countries are well behind in achieving sustainability goals [1]. Healthcare sustainability has gained greater attention from researchers and administrators, particularly because of economic, environmental, and social-related issues deteriorating in developing countries [2]. Hospitals are complex organizations and healthcare outcomes are entangled with well-being, which broadens the phenomenon to environmental, social, mental, and physical aspects [3]. As healthcare is a service industry and labor-intensive in nature, the role of human resources in organizational effectiveness becomes dominant [4]. Sustainability is central to organizational growth and success, and the triple bottom line (TBL) approach has classified sustainability into economic, environmental, and social dimensions [5]. These dimensions play a varying role in organizational effectiveness depending upon internal and external situational factors. In the case of healthcare services delivery where both cure and care are provided with human hands, social sustainability does play a convincing role in providing quality services to the patients [4,6]. Organizational social sustainability reflects the quality of relationships between the organization and stakeholders, particularly for its employees. Socially sustainable organizations gain benefit from the behavioural features of the organization and do not usually suffer from behavioural problems, including lack of motivation, turnover intention, lack of commitment, and loyalty [7].

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is an effective tool to uphold sustainability in an organization by emphasizing its economic, social, and environmental dimensions [8]. Regardless of the increasing popularity of CSR in developed countries, it is in its early phase of life in emerging countries due to the challenges faced by organizations [1]. It is suggested that CSR at a micro- or narrower level can be effective in managing workforce-related issues [9]. Hospitals are labor-intensive units, and the roles of employees are decisive in discharging corporate social responsibilities. Concentration on micro-level CSR can yield a rather more pertinent outcome, since every employee becomes responsible for his/her CSR-related activities [10]. Once CSR undertakings are introduced at an individual level in an organization, it will motivate the employees to engage in the activities that promote CRS-related goals [11]. Therefore, by being familiar with individual-level CSR activities, individuals will be in a better state to realize their CSR-related activities [12]. In the same way, when an organization announces CSR as one of the organizational values and integrates it into their core business objectives, this makes sense for the employees, as their organization is showing serious concern for the environment and the employees [13,14].

Gulf Cooperation Council countries’ healthcare expenditures are less than those of developed countries, although per capita incomes are comparable [15]. The rising healthcare costs are linked to the scarcity of specialties and quality of healthcare services [16]. Healthcare givers are mostly expatriates, and hospitals face a great deal of turnover tendency [16]. According to a survey, 38% of UAE nationals prefer to get treatment from abroad, while 47% of Bahrain nationals and 43% of Oman nationals prefer to travel to other countries to get healthcare services and quality treatment [15]. Although healthcare facilities are provided to both nationals and expatriates in GCC countries to meet the growing demand for quantity and quality of healthcare services, there is a need for an effective and strong healthcare services delivery structure [17].

Since the healthcare sector is a service industry, any lacuna in the quality of service can cost human lives. The problem arises when employees do not give their maximum performance and commitment. Therefore, employees’ lack of behavioural and emotional attachment with the organization can produce devastating results for hospitals and patients. In this regard, social sustainability is considered to be an effective mechanism to overcome these problems. These facts call for research through three dimensions. Firstly, there is a need to understand the strength of and sense of affiliation of the human resource of the healthcare sector. As healthcare is a service delivery sector, the prime role rests with the workforce. Therefore, social sustainability is the defining factor of effective healthcare service delivery. Secondly, the involvement of the employees in corporate social responsibility needs to be investigated. Healthcare organizations are vulnerable to environmental hazards and need proper environmental management and sensitivity. It is frequently observed that some patients deserve philanthropic attention due to marginalized economic and social resources. Thirdly, there is a need to determine whether CSR at the micro-level plays a role in the formation and development of organizational social sustainability. Thus, keeping in view the relative importance of healthcare services and the dependence of healthcare services delivery largely on social capital, the study aimed at (i) investigating whether social sustainability is a matter of concern for hospital administrators, (ii) if micro-level CSR activities exist in the given healthcare setting, (iii) whether micro-level CSR plays a role in strengthening social sustainability, and (iv) to what extent each dimension of micro-CSR affects social sustainability. To the best of our knowledge, the relationship between micro-level CSR and social sustainability has not yet been investigated in general, and in the healthcare setting of Bahrain in particular, the findings can be seminal addition to the existing literature. The study is quantitative, cross-sectional, and explanatory in nature. Data were collected through close-ended questionnaires from randomly selected employees of four hospitals in Bahrain. Inferential statistics were applied to test hypotheses. Findings confirm the distinctive role of micro-level CSR on social sustainability.

This research work has been presented in six sections. Section 1 presents the introduction part, Section 2 presents the literature review and hypotheses, Section 3 presents the methodology section, Section 4 presents results, Section 5 presents the discussion, and Section 6 presents the conclusion, recommendations, implications, and limitations of the study.

2. Related Literature and Hypotheses

Sustainability is an attractive phenomenon and is frequently discussed in academic circles, managerial meetings, research events, and political platforms [18]. It is one of the core objectives of the United Nations and it wants to see sustainability in all aspects of life in the world [19]. Deliberation and research are carried out to explain what sustainability is, why it is important, and how it is managed. Sustainable development is a broad concept that balances the need for economic growth with environmental protection and social equity [20]. The concept of organizational success has gone beyond financial positions and profitability, and sustainable organizations are considered to be successful instead [21]. The construct of sustainability has been coined with economic, environmental, and social factors such as the ingredients of its composition. Sustainable organizations are not necessarily financially affluent—rather they balance prosperity, people, and the planet by ensuring a decent equilibrium among these three Ps [22]. Sustainability is now considered a means of potential competitive advantage, differentiation, and integrated value creation [23].

Social sustainability refers to the human side of an organization [7,24]. Social scientists and researchers of human behavior in organizations confirm the profound effect of human behavior, both cognitive and psychological, on overall organizational performance [21]. With the development of financial and technology markets, managers are more inclined toward human resources to gain a competitive advantage [25]. Social sustainability in an organization is the capability of the workforce to perform under any condition faced collectively or individually. Social sustainability is the integration between the workforce and the organization cannot gain sustainability and grow complex when the workforce prefers individuality and fails to be integrated [26]. Similarly, sustainability cannot be ensured when an integration effort within the organization is performed without the proper development of individual employees [27]. This will result in a network of employees where no novelty will take place to share. To do this, firstly, employees should be complex in their ideas and performance and make their performance worthy and contribute to organizational sustainability [27,28]. Secondly, the employees will have the capacity to learn collectively and integrate into teams, groups, departments, and organizations with complex mental and action patterns [29]. Therefore, social sustainability in organizations comes into existence when employees and groups interact with each other and their development happens together [11,30].

In the present era, most organizations around the globe confront growing demands from inside and outside stakeholders to prove not only financial performance but also environmental and social contributions. Corporate social responsibility is dedicated to a broader set of stakeholders, not just shareholders. Contemporary researchers believe that CSR is one of the key strategies that yields multiple outcomes for the organization [31,32]. Since corporate social responsibility is complex and context-specific, which is understood differently by different researchers and practitioners, there is no agreed-upon definition of CSR. However, most of the authors are in line with the most cited definition of CSR by Carroll [33], who defines it as “CSR consists of four types of res possibilities for organizations, including legal, economic, ethical, and philanthropic obligations”. Micro-level CSR is the mechanism to engage employees in the workplace which can create a sustainable future [23]. Eventually, this mechanism can create a sense of collective contribution toward the organization in the employees [21].

This study adopts the definition of MCSR coined by Rupp and Mallory [34], who define micro-level CSR as “Micro-level CSR is the study of CSR effects on individual levels (in any stakeholder group) to attain sustainability”. Literature on CSR presents micro-level CSR as an emerging or new organizational value toward organizational sustainability [10,35,36] and to develop the employees’ pro-organizational behavior [10,37]. This study defines employees’ pro-organizational behavior in line with the definition of Kohan and Mazmanian [38], who defines it as “employees’ pro-organizational behavior is the behavior of all employees at the workplace to advance environmental and social sustainability”.

Presently, researchers and practitioners are diverting their attention to individual-level corporate social responsibility (micro-level CSR) and have linked this to the achievements of different employee-related outcomes [9]. The literature exhibits that employee’s perception regarding his/her organization can profoundly impact their behavior and attitude [39,40,41]. Accordingly, corporate social responsibility (CSR) is considered a determining factor to influence the behavior and attitude of employees in the organization [41]. A significant number of researchers have verified the importance of CSR to gain employee-related outcomes [42,43,44]. However, the connection of micro-level CSR to social sustainability in the context of healthcare is yet to be sufficiently explored. Therefore, the research in hand attempts to investigate the relationship between micro-level CSR and social sustainability in the context of healthcare in Bahrain.

The current study intentionally selects the healthcare sector to test hypotheses. This field was selected for several reasons. First, like other service sectors, healthcare is a labor-intensive industry in which employees’ contribution is crucial to achieve organizational goals [6,9]. The author’s argument here is that employees are expected to demonstrate commitment toward extra roles, such as loyalty, when they are provided with a conducive work environment. In this regard, micro-level CSR practices are the strategic enablers to augment their commitment to organizations [45,46]. Second, micro-level CSR is a relatively new term for researchers and practitioners. Literature on micro-level CSR is not that rich and the majority of this literature has been created in Western countries, while the literature on micro-level CSR in the context of emerging countries is insignificant [10,47,48,49]. To the best of the author’s knowledge, literature does not exist regarding micro-level CSR in the population under study. Third, the healthcare sector further sensitizes towards the need of investigating CSR at the micro-level [50,51] to enable healthcare administrators to translate the benefit of micro-level CSR activities towards social sustainability. These are the research gaps that created the motivation for this study.

This study uses the assumptions of Social Identity Theory (SIT) [52] to develop hypotheses. This theory claims that the self-concept of a person is obtained from his/her perceptions about a social group to which he or she belongs. Certainly, SIT has been extensively employed by researchers to explain individual behavior in a particular situation and context [53,54,55]. The study by Hu, Liu [56] stated that SIT explains why there is value congruence among employees and a socially responsible organization. Certainly, as employees observe that their organization acts ethically in the best interests of the community and society, this creates a strong sense of organizational identity [57]. This strong association and identification of employees make them consider organizational success as their success; therefore, they engage in extra-role behavior that could lead to organizational social sustainability. A socially responsible organization is expected to equip its employees with an environment that is safe and less restricted, and in return, employees ultimately become inclined towards collective contribution to the organizational cause, thus forming social sustainability [43]. As a result, employees gain intrinsic motivation in employees, and this strong intrinsic motivation strengthens their association with the organization [58]. Hur, Kim [59] revealed that micro-level CSR practices positively influence the sense-making ability of employees, which is in turn linked with social sustainability. According to SIT, a positive sense of an employee regarding a socially responsible organization compels a person to contribute to the organization beyond the job description by performing various extra roles [60]. Following SIT, employees are supposed to accomplish extra roles as they identify themselves with the organization, having profound aspirations to increase the goodwill of their organization.

2.1. Variables and Their Definitions

Organizational Social Sustainability (OSS)

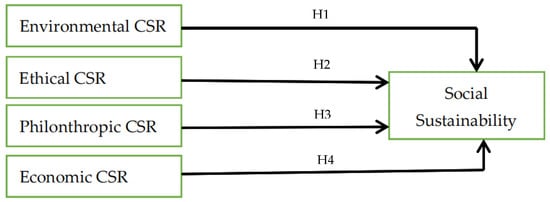

Sustainability is a multidimensional and complex phenomenon. It consists of three basic dimensions: economic, environmental, and social. The social dimension of sustainability relates to the management and serving the interest of internal and external stakeholders including employees. OSS is a dominant dimension of sustainability which covers the employees’ contribution toward organizational sustainability [6]. The collective contribution of employees to overall sustainability and their role in making it is known as social sustainability [61,62]. It is a mutual response, fulfilling employees’ expectations and a conducive work environment, and employees in return fulfil expectations of the organization on a long-term basis [7,63]. Therefore, the construct of social sustainability can be defined as the cordiality of the relationship between an organization and its employees on a relatively long-term basis [6]. OSS is the phenomenon of interest and is taken as the criterion variable, and the four dimensions of micro-level CSR are linked as predictive variables to explain this (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility

Theoretically, CSR refers to the voluntary contribution of an organization towards sustainable development beyond legal and regulatory requirements [62]. CSR at a micro-level also engages in environmental, economic, philanthropic, and ethical performance [47,64,65]. The definition of micro-level CSR is borrowed from Rupp and Mallory [34], who describe micro-level CSR as “Micro-level CSR is the study of CSR effects on individual levels (in any stakeholder group) to achieve sustainability”.

2.2.1. Environmental CSR

It is believed that employees and the organization as a whole should practice environment and employee-friendly ways as much as possible [66]. Organizations can be major contributors to emissions of greenhouse gas, waste, pollution, and depletion of natural resources, but by promising environmental responsibility, an organization accepts the ownership of its effect on the environment [47]. Therefore, it refers to controlling and managing the activities that cause pollution in either form, or contaminating the surroundings, promoting the activities that contribute to green practices and environmentally friendly undertakings.

2.2.2. Economic CSR

When an organization performs while keeping economic social responsibility in mind, it is taking a financial decision in a way that ensures the welfare of the stakeholders and social and environmental sustainability [67]. Economic CSR is a mechanism to minimize negative externalities and maximize positive externalities. In this study, economic CSR refers to all the decisions that augment employees’ financial benefits and maintain a standard of fairness in rewards among a diverse workforce in the organizations. Economic CSR presents meritocratic financial decisions, and the consequences of these decisions impact beyond the described patterns of financial returns.

2.2.3. Philanthropic CSR

In the contemporary world, it is believed that organizations will return back to the environment where they exist and donate to the causes that align with the vision of the organization [68]. In this way, organizations perform their philanthropic responsibility. In this study, philanthropic CSR refers to the activities which are directed to financially, physically, mentally, and socially support marginalized stakeholders and the members of society.

2.2.4. Ethical CSR

Ethically responsible organizations engage in impartial and merit-based organizational practices across the board. This includes fairly treating all stakeholders, particularly employees and customers, with respect [69]. It refers to creating an environment of justice where all the stakeholders feel that things are happening as per desired values and norms. Stakeholders are not discriminated against treatment and distribution of resources based on socioeconomic backgrounds.

2.3. Hypotheses

The work environment is one of the determining factors of employee satisfaction, performance, and positive responses towards organizations. The work environment is predominantly composed of physical facilities, including technology, rooms, furniture, and the like [70]. According to the Two Factor theory, favorability of the work environment reduces employee job dissatisfaction, while other researchers consider environmental ambience as one of the major causes of work motivation [71]. It has also been concluded that the conduciveness of the work environment significantly reduces employee turnover rate and turnover intentions [72]. Companies are bound to fulfill their economic responsibility because awareness of environmental issues is growing largely among the consumers, and today they want businesses to take necessary steps to save our planet and preserve all the lives on it [73]. Organizations that are concerned with reducing environmental pollution have earned good social standings as good corporate figures for serving society [74]. The performance of healthcare professionals is dependent on tangibles, including medical and surgical equipment, diagnostic labs, operation theatres, outdoor and indoor layouts, beds, study rooms, and the like. Thus, the desired workplace tangibles enable healthcare professionals to perform their best and move forward toward self-actualization. Based on these reviews, it is hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Environmental CSR at the micro-level will positively affect the social sustainability of that hospital.

Ethical CSR activities are moral obligations and are intensely linked with the responsibilities that organizations have to the individuals or groups to whom they might cause harm during their performance [75]. This responsibility exceeds the established legislative framework. The ethical element of CSR is related to actions that are permissible or forbidden in the organization without any binding by the law [20]. Ethical CSR focuses on looking after the employees and caring about their welfare through fair labor practices and also for other stakeholders, including suppliers [76]. Ethical labor practices for suppliers mean that the companies will ensure the use of products that have been certified as meeting fair trade standards [77]. Ensuring fair labor practices for employees ensures that there is no gender, race, or religious discrimination among the employees, and that each employee will be given equal pay for equal work and better living wage compensation. Therefore, the following hypothesis is framed:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Ethical CSR at the micro-level will positively influence the social sustainability of that hospital.

Philanthropic or altruistic CSR activities are linked to a utilitarian standpoint (social care, justice, equity), and this is beyond an organization’s economic and financial benefits [75]. These practices are advantageous for employees, suppliers, customers, collaborators, and society at large. The philanthropic dimension of CSR calls for companies to donate to society in uplifting the quality of life [20]. Thus, serving humanity is the essence of philanthropic social responsibility. This dimension takes care of the well-being of the marginalized and underprivileged or poor people who seriously need others’ support to sustain themselves on earth [78]. Organizations realize their philanthropic responsibilities by offering their money, time, and other resources to welfare organizations at domestic or global levels [79]. These contributions are mostly provided to various worthy causes, including disaster relief, human rights, treatment of poor patients, and education programs in poor countries. In the same vein, the current study tests the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Philanthropic CSR at the micro-level will positively influence the social sustainability of that hospital.

Economic CSR practices enable an organization to be distinguished from its rivals by offering responsible products and services [75]. The economic aspect of CSR refers to the fair allocation of limited resources needed to produce goods and services [20]. Economic CSR is an interrelated field that emphasizes maintaining harmony among environmental, business, and philanthropic activities [80]. Economic CSR stands by the defined ethical standards and moral values. In this way, organizations’ efforts to arrive at a solution may provide a solution to the business problem as well as benefit the community and society.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Economic CSR at the micro-level will positively influence the social sustainability of that hospital.

3. Methods

The design of the study is quantitative, cross-sectional, and explanatory. Previously developed and validated instruments were used to tap the focal constructs of the research model. The scale, developed by Cella-De-Oliveira [81], was used to measure Organizational Social Sustainability (OSS). The author borrowed ready-made scales from the literature to measure the variables of the study to avoid validity and reliability concerns. For instance, the items for CSR were adapted from Turker [53]. A five point Likert type scale was attached to each item of the questionnaire (see questionnaire in Appendix A).

Data were collected from a tertiary hospital in Bahrain. This hospital has over 1200 beds for inpatients and over 2000 health professionals working in it. Doctors, nurses, and paramedics were educated and could respond to the questionnaire in English. After having the list of doctors, nurses, and paramedics, a sample of 516 subjects was selected through a stratified random sampling method. A team was formed and trained to collect data, and it took two months to collect data, starting in the first week of February 2022. Approval for data collection was obtained from the concerned authority of the hospital. Consent was obtained from each respondent for participation in data sharing voluntarily, and ethical standards were followed during data collection. Overall, 516 questionnaires were distributed to the randomly selected sample, of which 441 were included for analysis. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test hypotheses with SmartPLS-3. The sample profile is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample profiles.

4. Results

4.1. Reliability

Cronbach’s Alpha and Composite Reliability values were used to determine the reliability of the instrument (Table 2). All the Cronbach’s alpha values are greater than 0.70, which establishes the internal consistency of the instrument [82,83]. In addition to this, all the values of composite reliability also confirm the reliability of the instrument.

Table 2.

Reliability.

VIF values confirm that the data used are free of multicollinearity and common method bias. The occurrence of VIF greater than 10 indicates the existence of multicollinearity [84], while VIF values greater than 3.3 are proposed as an indication that a model may be contaminated by common method bias. Therefore, if all the VIFs resulting from a full collinearity test are equal to or less than 3.3, the model will be considered free of common method bias [85]. All the VIFs extracted from our data have values of less than 3.3, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Variance inflation factor.

4.2. Validity

The values of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were used to determine convergent validity (Table 2). All the AVE scores are higher than the threshold value (0.5), thus convergent validity is ensured. Fornell and Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio were used to measure discriminant validity. Assessment of discriminant validity is a must in any research that involves latent variables for the prevention of multicollinearity issues [86,87,88]. Fornell and Larcker criterion is the most widely used method for this purpose [87,88]. It compares the square root of the value of each average variance extracted (AVE) in the diagonal, with the coefficient of correlation of latent variable (off-diagonal) for each variable in the related columns and rows [87,88]. A variable must explain the variance of its indicators better than the variance of other latent variables. Thus, the square root AVE of each construct must have a greater score than the correlation coefficient of other latent variables. In our case, the square root of each AVE of a construct is greater than the correlation coefficients of other constructs. Therefore, discriminant validity is established as per the Fornell Larker criterion. Discriminant validity is also measured by Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio. To meet this criterion, values should be 0.9 or less. For this study, all the values are less than 0.9 (shown in Table 4), hence the criteria is met.

Table 4.

Discriminant validity (Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio).

4.3. Structural Model

Latent Variable Correlation explains indicator reliability [87]. Beta values indicating a correlational relationship among variables are significant (Table 5). Physical and chemical are moderately correlated, while other variables show relatively strong relationships. As no coefficient of correlation is greater than 0.8, the possibility of auto-correlation is ruled out.

Table 5.

Latent variable correlation.

The value of R Square explains that 42.8 percent variation in criterion variable is explained by exogenous variables included in (Table 6).

Table 6.

R Square.

According to the analysis of the path-coefficient (Table 7), all the hypotheses have been substantiated, however, with the varying degree of intensity of the relationship. The first hypothesis is barely accepted. The effect of economic CSR accounts for a 12% variation in organizational social sustainability, which is quite weak. However, the T value substantiates the outer model loading and provides evidence against the null hypothesis. P value also signifies the relationship. The second hypothesis has been substantiated. Philanthropic CSR has a positive effect on social sustainability. The coefficient value (0.173) is not that strong in nature, however, T statistics (4.807) exhibit the significance of outer model loading. p-Value (0.000) confirms the significance of the relationship also. The third hypothesis is accepted, and the statistical evidence shows the strongest relationship between ethical CSR and social sustainability. The path coefficient (0.649) indicates a strong impact of ethical CSR on organizational social sustainability. p Values and T values provide strong evidence in favor of the hypothesis. The last hypothesis is proved, and the path coefficient (0.250) denotes a moderate impact of assurance on social sustainability. T statistics (5.657) present that the outer model loading is significant, and p values also signify the relationship.

Table 7.

Path coefficient.

5. Discussion

Social sustainability is an extensively studied organizational phenomenon and one of the dominant factors that defines organizational success. However, in some regions like Gulf Cooperation Council countries, it has become popular in the present time [89,90]. The cognitive and affective embeddedness of employees in organizations forms social sustainability. It is a relatively stable relationship between the organization and the employees, while employees develop and share their knowledge and skills. Contemporary managers seek growth and competitive advantage through their committed and loyal workforce instead of other resources. It is a highly subjective and painstaking process for an organization to establish and improve social sustainability as many known and unknown factors affect it.

The data substantiated all the hypotheses, and some interesting findings were revealed in this study. The findings are in line with Social Exchange Theory [91], Norm of Reciprocity [92], and Two Factory theory [73]. Employees’ collective contribution to the organization rises when their expectations are met. The hypothesis showing the impact of physical facilities on social sustainability is proved but the relationship is moderate and not that strong. Hospitals are bound to provide physical facilities to healthcare workers, otherwise patients cannot be treated. The hypothesis regarding economic CSR and social sustainability is accepted, however, the relationship is weak. The reason behind this is employees are not involved in economic decision-making. The economic activities and decisions flow according to preestablished structures, and funding is generally provided by the top cluster of management or government agencies. Therefore, employees have very little say in financial decision-making. On the other hand, individual employees do have a role in managing externalities which fall under economic CSR. Since hospitals cause negative externalities [93], employees endeavor to minimize these externalities and positively affect organizational social sustainability.

Philanthropic CSR impacts the collective contribution of employees according to the findings. The statistical indicators show greater support in favor of philanthropic CSR as compared to economic CSR. A considerable portion of the patient population in hospitals are deficient in resources and face affordability issues [4]. Apart from this, vulnerable employees who usually belong to low-level workforce clusters usually look for certain philanthropic activities to get out of problems. The culture of micro-level CSR in terms of philanthropic activities creates a sense of belongingness and affiliation with the organization among the workforce.

The strongest variable to affect social sustainability in our model is ethical CSR. It consists of creating a conducive environment where employees get a comfortable and fearless atmosphere to perform their jobs. Since hospitals are labor-intensive units, workforce diversity is high where the possibility of discrimination is obvious. However, these issues can be better handled by acting upon ethical standards. Medical and ethical standards are usually violated in hospitals [94], and maintaining privacy, minimizing ethnicity, race, gender, religion, and nationality-based discrimination and ensuring fair work practices significantly contributes to organizational social sustainability [35]. Employees feel that the hospital administration is always willing to help employees in solving their job-related issues, as well as their personal needs. Employees’ requests and needs are addressed immediately most of the time, and healthcare professionals do not complain of delays. Finally, employees feel comfortable, as hospital administrators usually respond to employees in a polite manner and have great respect for them. Therefore, responsiveness is statistically the most significant cause of employees contributing to the organization meaningfully.

Employees associate considerable importance with environmental CSR. Data analysis shows that environmental CSR is the second most influential predictor of social sustainability after ethical CSR. Hospitals produce waste which pollutes the external environment. Hospitals accounted for a large portion of environmental pollution and negative externalities. Therefore, more responsibility rests with hospitals to be careful regarding environmental CSR. Environmental degradation makes the workplace hazardous and employees vulnerable to health hazards. A hazardous workplace is one of the major factors of employee turnover intention. When environmental CSR, particularly at the micro-level, is effective, the workplace will be safe and employees will prefer to work therein.

The findings of the study revealed that the variables in hand account for around half of the composition of the criterion variable. The coefficient of determination exhibits that 42% making of social sustainability in the hospital is due to the nature of the relationship between employees and the organization. All the variables influence social sustainability, while ethical CRS is the most influential. It can be inferred that organizational social sustainability can be further strengthened by emphasizing micro-level CSR activities.

6. Conclusions

As employees enter into the employment contract with the organization, they do have certain expectations, and employee satisfaction is always the outcome of the realization of these expectations. Similarly, employment contracts have certain promises on behalf of the employer, and fulfillment of these promises directly influences employees’ intensity of affiliation with the organization. Findings from the healthcare sector of Bahrain revealed that corporate social responsibility at the micro- or individual level is a major determinant of social sustainability. Ethical CSR including a fair and just workplace environment is the most influential variable in affecting social sustainability, followed by environmental CSR, philanthropic CSR, and economic CSR, respectively. The findings revealed that CSR at a micro-level exists in the healthcare sector, and employees attach more importance to ethical CSR. The employees are well attached to the hospital and willing to contribute collectively and think of the long-term association. It is evident that this social sustainability is mainly due to the expectations that are generally met consistently, and they have an environment where they experience something extra from the individuals and organization as a whole beyond profit-earning motives. Thus, the experience of corporate social responsibility at the micro-level proved to be the major determinant of social sustainability.

6.1. Recommendations

Organizational success is directly dependent upon the overall contribution of its employees. The findings of the study confirmed that employees consistently contribute to organizational effectiveness when they see social responsibilities are met with a sense of devotion by employees. Based on the findings, the following recommendations are extended:

- Findings reveal that ethical practice has the highest influence on employees’ behavior. Employees produce positive behavior when they believe that fairness prevails and that employees are being treated equally. Therefore, it is recommended that managers to maintain fairness and equity within the organizations through ethical CSR practices, particularly at the micro-level.

- It is also evident from the findings that employees are concerned about environmental issues. In the healthcare setting, workplace hazards cause physical and psychological damage to employees. Under such circumstances, employees cannot maintain cordial and long-term relationships with the organization that forms social sustainability. That is why healthcare administrators need to pay serious attention to environmental CSR practices and make each individual involved in these practices.

- Employees, to some extent, value philanthropic practices. Some stakeholders are vulnerable in the healthcare settings and look for certain philanthropic activities. Since the influence of philanthropic practices on social sustainability is statistically significant, managers should ensure these kinds of activities in the organization.

- Economic CSR activities are weakly connected with social sustainability; however, it is more important for administrators to maintain fairness in economic CSR practices. When economic CSR practices are aligned with ethical CSR practices, this will cast a greater impact on organizational social sustainability.

- Hospital administrators need to create awareness regarding practicing CSR at the micro-level and its importance, which most employees do not know.

6.2. Implications

The findings of this study enrich the existing literature in many ways. For instance, the study in hand is a pioneering research work in the healthcare sector of Bahrain, considering the micro-foundation of CSR to augment the extra-role of employees like their collective contribution towards organizational objectives. The existing literature in the field presents that CSR has been largely investigated at the macro-level. The previous studies in the domain of CSR were largely conducted in the domain of macro-CSR [95,96,97].

Likewise, the piece of research adds to the existing treasure of literature on organizational behavior by introducing micro-level CSR as an enabler to better involve employees in forming social sustainability. Another valuable contribution of this research activity is highlighting the importance of micro-level CSR in the field of the healthcare sector, where employees’ collective contribution is necessary to achieve organizational goals.

Apart from theoretical relevance, the research work in hand has some significant implications for practitioners. First, the findings help improve the understanding of the policymakers, particularly those belonging to the healthcare sector in Bahrain to realize micro-level CSR as an enabler for social sustainability. It is important to mention that presently, CSR practices in the given population in general and in the healthcare sector, in particular, are philanthropic in nature [62,98]. Therefore, CSR is usually considered for donations and charity purposes. Thus, there is a need for managers to take CSR beyond charitable and even philanthropic purposes and extend it to economic, ethical, and environmental orientations. Yet another significant implication of this study is the claim that well-executed micro-level CSR practices in the healthcare sector can generate an emotional association among employees loyal to a socially responsible healthcare setting for a longer period. It is very important for managers to realize CSR as a tool to minimize turnover, which has direct negative bearings on organizational performance. Thus, by practicing micro-level CSR strategies, healthcare organizations are likely to minimize not only employee turnover but involve employees in indulging in extra roles to improve their group performance. Likewise, the findings of the study can be helpful for policymakers and practitioners to realize that they can survive and grow in the competitive business environment through social sustainability as the outcome of CSR.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study bears certain limitations and at the same time, these limitations open venues for further research. A single hospital was selected for data collection. Although sufficient data were collected, problems regarding the generalization of findings cannot be ruled out. Data were collected from the three strata of employees, including doctors, nurses, and paramedics, and other categories such as medical students, administrators, pharmacists, etc. We suggest future research should include other stakeholders to get more detailed results. Yet another limitation is cross-sectional data, which may limit the causality of the variables. Therefore, future research is suggested to collect longitudinal design to see temporal effects. Lastly, the study did not include control variables (age, gender, etc.). Therefore, future researchers are suggested to include control variables for better results.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Because of the observational nature of the study, and in the absence of any involvement of therapeutic medication, no formal approval of the Institutional Review Board of the local Ethics Committee was required. Nonetheless, all subjects were informed about the study and participation was fully on a voluntary basis. Participants were ensured of confidentiality and anonymity of the information associated with the surveys. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire Used for Data Collection

Responses were recorded along a 5-point Likert type scale (Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree).

| Our company participates in activities which aim to protect and improve the quality of the natural environment. |

| Our company makes investment to create a better life for future generations. |

| Our company implements special programs to minimize its negative impact on the natural environment. |

| Our company targets sustainable growth which considers future generations. |

| Our company contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of the society. |

| Our company encourages its employees to participate in voluntarily activities. |

| Our company emphasizes the importance of its social responsibilities to the society. |

| Our company policies encourage the employees to develop their skills and careers. |

| The management of our company is primarily concerned with employees’ needs and wants. |

| Our company implements flexible policies to provide a good work and life balance for its employees. |

| The managerial decisions related with the employees are usually fair. |

| Our company supports employees who want to acquire additional education. |

| I want to live in this region for more years. |

| I feel a sense of belonging as member of community. |

| Friendship in my neighborhood is important for me. |

| I usually chat with people in my region. |

| The majority of the people in the region are trustable. |

| I am willing to work with people to improve my region. |

| I would like to have a voice in the decisions affecting my region. |

| I am satisfied with maintenance of neighborhood. |

| I feel a sense of belonging to the region that I am living. |

| I feel a sense of belonging to the house that I am living. |

| I like to spend time with my neighbors in my garden/veranda/balcony. |

| I am happy with the area that I am live in. |

References

- Karamat, J.; Shurong, T.; Ahmad, N.; Afridi, S.; Khan, S.; Mahmood, K. Promoting healthcare sustainability in developing countries: Analysis of knowledge management drivers in public and private hospitals of Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamat, J.; Shurong, T.; Ahmad, N.; Waheed, A.; Mahmood, K. Enablers supporting the implementation of knowledge management in the healthcare of Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratnapalan, S.; Lang, D. Health care organizations as complex adaptive systems. Health Care Manag. 2020, 39, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.Z.; Khan, M.A. Towards service quality measurement mechanism of teaching hospitals. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2021, 14, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, L. Relevance of triple bottom line reporting to achievement of sustainable tourism: A scoping study. Tour. Rev. Int. 2005, 9, 79–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Álvarez-Otero, S.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Sial, M.S.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Omhand, K. Achieving organizational social sustainability through electronic performance appraisal systems: The moderating influence of transformational leadership. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Sulaiman, M.A.B.A.; Ali, S.B.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. The effect of work safety on organizational social sustainability improvement in the healthcare sector: The case of a public sector hospital in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bux, H.; Zhang, Z.; Ahmad, N. Promoting sustainability through corporate social responsibility implementation in the manufacturing industry: An empirical analysis of barriers using the ISM-MICMAC approach. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1729–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Han, H.; Araya-Castillo, L.; Ariza-Montes, A. Fostering Hotel-Employee Creativity through Micro-Level Corporate Social Responsibility: A Social Identity Theory Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 853125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; Waqas Kamran, H.; Scholz, M.; Han, H. Relationship between corporate social responsibility at the micro-level and environmental performance: The mediating role of employee pro-environmental behavior and the moderating role of gender. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1138–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.S.; Wu, C.; Ullah, Z. The Inter-Relationship between CSR, Inclusive Leadership and Employee Creativity: A Case of the Banking Sector. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, F.; Khan, N.R. National Culture, Employee’s Engagement and Employee’s CSR Perceptions in Technology Based Firms of Pakistan. J. Manag. Sci. 2019, 6, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Schönfeld, J.; Bilan, Y.; Dudáš, T. Study of the differences in the perception of the use of the principles of corporate social responsibility in micro, small and medium-sized enterprises in the V4 countries. J. Compet. 2022, 14, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Cherian, J.; Zaheer, M.; Sial, M.S.; Comite, U.; Cismas, L.M.; Cristia, J.F.E.; Oláh, J. The Role of Healthcare Employees’ Pro-Environmental Behavior for De-Carbonization: An Energy Conservation Approach from CSR Perspective. Energies 2022, 15, 3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoja, T.; Rawaf, S.; Qidwai, W.; Rawaf, D.; Nanji, K.; Hamad, A. Health care in Gulf Cooperation Council countries: A review of challenges and opportunities. Cureus 2017, 9, e1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram, P. Management of Healthcare in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries with special reference to Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2014, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A. The development of the Qatar healthcare system: A review of the literature. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2015, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Ullah, Z.; Arshad, M.Z.; Sabir, R.I.; Khan, W.A. The nexus of CSR and co-creation: A roadmap towards consumer loyalty. Sustainability 2021, 13, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexell, M.; Jönsson, K. Responsibility and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. In Forum for Development Studies; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017; pp. 13–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, A.; Bashir, J. How does corporate social responsibility transform brand reputation into brand equity? Economic and noneconomic perspectives of CSR. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2020, 12, 1847979020927547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, M.S.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; Iqbal, M.; Ismail, M. Establishing a corporate social responsibility implementation model for promoting sustainability in the food sector: A hybrid approach of expert mining and ISM–MICMAC. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 8851–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koshy, K.C. Sustainability Models for a Better World; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R. The five strategic building blocks of mandated corporate social responsibility (CSR). In Mandated Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wals, A.E. Shaping the Education of Tomorrow: 2012 Full-Length Report on the UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Ahmed, B.; Ahmad, I.; Usman, M. Perceived accuracy of electronic performance appraisal systems: The case of a non-for-profit organization from an emerging economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social sustainability: A new conceptual framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schönborn, G.; Berlin, C.; Pinzone, M.; Hanisch, C.; Georgoulias, K.; Lanz, M. Why social sustainability counts: The impact of corporate social sustainability culture on financial success. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. An exploration of measures of social sustainability and their application to supply chain decisions. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1688–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colantonio, A. Social sustainability: A review and critique of traditional versus emerging themes and assessment methods. In Proceedings of the SUE-Mot Conference 2009: Second International Conference on Whole Life Urban Sustainability and its Assessment, Loughborough, UK, 22–24 April 2009. [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute, University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Doh, J.P.; Lawton, T.C.; Rajwani, T. Advancing nonmarket strategy research: Institutional perspectives in a changing world. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2012, 26, 22–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantrell, J.E.; Kyriazis, E.; Noble, G. Developing CSR giving as a dynamic capability for salient stakeholder management. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantos, G.P. The boundaries of strategic corporate social responsibility. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 595–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, D.E.; Mallory, D.B. Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacinello, E.; Tontini, G.; Alberton, A. Maturity in sustainable innovation and corporate social responsibility: Implications in business performance. Braz. J. Manag./Rev. Adm. UFSM 2019, 12, 1293–1308. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Nazim, Z.; Ramzan, M. Impact of CSR on corporate reputation, customer loyalty and organizational performance. Gov. Manag. Rev. 2020, 5, 195–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Naveed, R.T.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Hamid, T.A.; Han, H. Towards making an invisible diversity visible: A study of socially structured barriers for purple collar employees in the workplace. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohan, A.; Mazmanian, D. Police work, burnout, and pro-organizational behavior: A consideration of daily work experiences. Crim. Justice Behav. 2003, 30, 559–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Wright, T.A. When a “happy” worker is really a “productive” worker: A review and further refinement of the happy-productive worker thesis. Consult. Psychol. J. Pract. Res. 2001, 53, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.-M.; Moon, T.-W.; Ko, S.-H. How employees’ perceptions of CSR increase employee creativity: Mediating mechanisms of compassion at work and intrinsic motivation. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 153, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Cherian, J.; Ahmad, N.; Scholz, M.; Samad, S. Conceptualizing the Role of Target-Specific Environmental Transformational Leadership between Corporate Social Responsibility and Pro-Environmental Behaviors of Hospital Employees. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khaskheli, A.; Jiang, Y.; Raza, S.A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Khan, K.A.; Salam, J. Do CSR activities increase organizational citizenship behavior among employees? Mediating role of affective commitment and job satisfaction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 2941–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Yin, X.; Lee, G. The effect of CSR on corporate image, customer citizenship behaviors, and customers’ long-term relationship orientation. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSuwaidi, M.; Eid, R.; Agag, G. Understanding the link between CSR and employee green behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 46, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afridi, S.A.; Afsar, B.; Shahjehan, A.; Rehman, Z.U.; Haider, M.; Ullah, M. Retracted: Perceived corporate social responsibility and innovative work behavior: The role of employee volunteerism and authenticity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1865–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work: Role of employees’ CSR perceptions and evaluations. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 2024–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Proactive CSR: An empirical analysis of the role of its economic, social and environmental dimensions on the association between capabilities and performance. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 115, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Glavas, A. When corporate social responsibility (CSR) meets organizational psychology: New frontiers in micro-CSR research, and fulfilling a quid pro quo through multilevel insights. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamali, D.; Carroll, A. Capturing advances in CSR: Developed versus developing country perspectives. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2017, 26, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannarakis, G. The determinants influencing the extent of CSR disclosure. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, H.M. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance in the healthcare Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Northcentral University, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. Social categorization, social identity and social comparison. In Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Ashraf, S.; Sarfraz, M. The organizational identification perspective of CSR on creative performance: The moderating role of creative self-efficacy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Ullah, Z.; AlDhaen, E.; Han, H.; Scholz, M. A CSR perspective to foster employee creativity in the banking sector: The role of work engagement and psychological safety. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. The impact of employees’ perceived CSR on customer orientation: An integrated perspective of generalized exchange and social identity theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, A.; Kashif, U.R.; Syed, I.A.; Jamil, Y.; Maria, Z. Corporate social responsibility influences, employee commitment and organizational performance. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 2796–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Skudiene, V.; Auruskeviciene, V. The contribution of corporate social responsibility to internal employee motivation. Balt. J. Manag. 2012, 7, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.K. Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, N.; Livuza, L.; Zhou, N. Employees’ perceptions of corporate social responsibility and creativity: Employee engagement as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2019, 47, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The social dimension of sustainable development: Defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tarawneh, K.I. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practice in Bahrain. J. Bus. Econ. Policy 2018, 5, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missimer, M.; Robèrt, K.-H.; Broman, G. A strategic approach to social sustainability–Part 2: A principle-based definition. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxi, C.V.; Ray, R.S. Corporate Social Responsibility; Vikas Publishing House: Mumbai, India, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Johns, R. The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currás-Pérez, R.; Dolz-Dolz, C.; Miquel-Romero, M.J.; Sánchez-García, I. How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pala, B. Communicating philanthropic CSR versus ethical and legal CSR to employees: Empirical evidence in Turkey. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2020, 26, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, A.K. Ethical corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the pharmaceutical industry: A happy couple? J. Med. Mark. 2009, 9, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, H.A. Building a workplace of choice: Using the work environment to attract and retain top talent. J. Facil. Manag. 2003, 2, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshmemri, M.; Shahwan-Akl, L.; Maude, P. Herzberg’s two-factor theory. Life Sci. J. 2017, 14, 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kurniawaty, K.; Ramly, M.; Ramlawati, R. The effect of work environment, stress, and job satisfaction on employee turnover intention. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate social responsibility during COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frederiksen, C.S.; Nielsen, M.E.J. The ethical foundations for CSR. In Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, K. Ethical concerns at the bottom of the pyramid: Where CSR meets BOP. J. Int. Bus. Ethics 2009, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- von Schnurbein, G.; Seele, P.; Lock, I. Exclusive corporate philanthropy: Rethinking the nexus of CSR and corporate philanthropy. Soc. Responsib. J. 2016, 12, 280–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C. Corporate philanthropic giving and sustainable development. J. Manag. Dev. 2020, 39, 837–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, A.; Luo, J. An economic case for CSR: T he comparative efficiency of for-profit firms in meeting consumer demand for social goods. Strateg. Manag. J. 2018, 39, 1650–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cella-De-Oliveira, F.A. Indicators of organizational sustainability: A proposition from organizational competences. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2013, 2, 962. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R.H. The structural equation modeling approach: Basic concepts and fundamental issues. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Sage Publications, Inc.: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.Z.; Siddique, M. Analysis of employees’ perception of workplace support and level of motivation in public sector healthcare organization. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook; Sage Publications: Southern Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. E-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, R.; El-Zaemey, S.; Dorji, N.; Fritschi, L. Reliability and Validity ofan Adapted Questionnaire Assessing Occupational Exposures to HazardousChemicals among HealthCare Workers in Bhutan. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2020, 11, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ab Hamid, M.; Sami, W.; Sidek, M.M. Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017, 890, 012163. [Google Scholar]

- Afthanorhan, W. A comparison of partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) and covariance based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) for confirmatory factor analysis. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Innov. Technol. 2013, 2, 198–205. [Google Scholar]

- Daher-Nashif, S.; Bawadi, H. Women’s health and well-being in the united nations sustainable development goals: A narrative review of achievements and gaps in the gulf states. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, L.A.; Hashim, H.B. A century of Saudi-Qatari food insecurity: Paradigmatic shifts in the geopolitics, economics and sustainability of Gulf states animal agriculture. Arab World Geogr. 2017, 20, 261–281. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, P.M. Social exchange. Int. Encycl. Soc. Sci. 1968, 7, 452–457. [Google Scholar]

- Gouldner, A.W. The norm of reciprocity: A preliminary statement. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1960, 25, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutkan, M.N.; Kara, O.; Eraslan, İ.H. An implementation on the social cost of hospital acquired infections. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 4433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y. Patient privacy and autonomy: A comparative analysis of cases of ethical dilemmas in China and the United States. BMC Med. Ethics 2021, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.S.; Baasandorj, S. Exploring CSR and financial performance of full-service and low-cost air carriers. Financ. Res. Lett. 2017, 23, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, S.; Caroli, M.G.; Cappa, F.; Del Chiappa, G. Are you good enough? CSR, quality management and corporate financial performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 88, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Mohammad, S.J.; Nawaz, N.; Samad, S.; Ahmad, N.; Comite, U. The Role of CSR for De-Carbonization of Hospitality Sector through Employees: A Leadership Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).