Abstract

In this paper, social capital was analyzed through the lens of the resources and capabilities theory, understanding it as a capability that has a role in the performance of the Smart City. Social capital relates to the technological capabilities and the technological learning process. The objective of this investigation was to build a representation model of the social capital resources and technological learning, taking social capital as a capability of the Smart City. First, on a methodological level, a preliminary exercise that shows the relation and the gaps between the concepts and the process to build the model are presented. Later, the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was used to build the conceptual and measured model. Based on the configuration of the tangible variables, the model was tested with the information provided by the final users of the public urban bicycle system of the Medellín–EnCicla technological system. The impact of technological learning is interpreted by relating it to the sources of social capital, to its resources (trust, social interaction, and shared vision), and to the technological system chosen. As a result, the construction of an exploratory model is presented that interprets the resources of social capital and their relation to technological learning in a smart city. The investigation aims to contribute to the decision-making exercise in the public policies regarding the sustainable mobility of the smart city that was the object of study.

1. Introduction

The common ground throughout specialized literature on the Smart City (hereinafter SC) category is that it is based on theories of the contemporary city. These theories understand the city as an informational, global, and postmodern one [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The review of this literature made visible that the city is configured by a new intelligence [9,11], the consequence of historical processes that have made it possible for the city to be endowed with a nervous, bone-and-skin structure, and to become a body of interconnected networks.

Thus, the SC manifests itself in a complex structure that has a new intelligence residing in the interconnection of resources. This intelligence is applied to the analytical, modeling, optimization, and visualization service processes. It also implies the capability of people to learn, develop, and implement new technologies [12]. At the same time, the SC is not only based on traditional and modern communication infrastructure (transportation and communicational technologies), but it is also developed through Social Capital [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

The representation of the contemporary city is given in an organizational structure that gives way to formal relations and to the coordination of actors for the achievement of goals [3,6,9]. Given this, it is possible to understand and analyze the SC from the point of view of resources and capabilities theory. The comprehension of the city’s resources and capabilities opens the door for recognizing social capital as one of various capabilities. Capabilities are understood as the abilities of an organization to carry out its productive activities efficiently and effectively through the unfolding, combination, and coordination of resources [23]. Social Capital has been conceptualized as the capability through which a social structure obtains benefits [24,25]. The resources of this capital are social interaction, trust, and shared vision [25,26]. As a capability, social capital is a technological one.

In the present research, the technological capability is the ability to make use of technological knowledge [27] and for an organizational structure to develop technological activities [28]. In this sense, capabilities hold technological knowledge, the know-how, the research and development, and the specific technological intellectual capital.

When analyzing social capital in a SC technological system, the technological learning is a process inherent in the analysis. From this perspective, technological learning is conceived as a social and dynamic process of internal and external interaction between actors. This process signals the capabilities building [27] and is an integrated means of information acquisition that boosts the accumulation of knowledge [29,30]. This accumulation is possible when the resources of social capital (social interaction, trust, and shared vision) are implemented trough the promotion of interaction and routines that are part of the learning process. In this sense, the technological learning is a source of social capital.

Up to this point, it has been found the close relationship between the SC, social capital, and technological learning. This proposes the conceptualization of a model that represents the resources of social capital and the technological system in a SC, the relation between the technological learning as a source of social capital, and the possessions final users have on social capital. This is supported on the systematic treatment that Portes [24] gives to the concept of social capital. This gives way to recognize the research gap of the present investigation: there is a breach in knowledge on how to analyze social capital (understood as the capability of the SC manifested in an organizational social structure).

Thus, the main question that arises is how the relation between the resources of social capital, social interaction, trust, and shared vision, and the technological learning process, understood as a source of social capital in a technological system in a SC, is configurated. To give answer to this question, the objective of the investigation was to build a representation model of the resources of social capital and of technological learning based on the analysis of social capital taken as a capability in the SC, parting from the hypothesis that the resources and capabilities theory analysis on social capital in the SC represents the use of the SC resources and the relation with the technological learning in it.

The representative model chosen to satisfy the objective was the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) that, among the classification of other Structural Equations Model (SEM), belongs to the second-generation group of exploratory type. The application of PLS-SEM is on social empirical circumstances. Therefore, this model was elected because it is a method to analyze the complex relation between latent variables, that allows the explanation of observed data and the analysis of theoretical and empirical conditions of the social sciences. The theoretical model built from this PLS-SEM was tested on the public urban bicycle system of Medellín–EnCicla. The city is considered a SC according to the to IMD Smart City Index [31].

2. Materials and Methods

Considering the theoretical value of PLS-SEM and the pre-existent relationship between SEM models, social capital, and SC, it is proposed to give an answer to the research problem through the building of a PLS-SEM Model that represents the behavior of social capital in a technological system of SC and shows the relationship between social capital and technological learning of the SC.

2.1. Literature and Surveillance

SEM are used to establish the relation of dependence between variables [32] p. 16. This means that these models integrate a series of lineal equations and establish which of them are dependent or independent from others; at the same time, inside the model, the independent variables can be dependent from other variables in other relationships.

These models allow us to create measurement error models by incorporating abstract and unobservable constructs (latent variables). They model the relationship between multiple predictor variables (independent or exogenous) and criteria variables (dependent or endogenous). Therefore, they work with observable or measurable variables (those which has an input value) and one or several latent or non-observable variables (those which do not have value and can be used as a concept). This strengthens the correlations used and makes more precise estimates of the structural coefficients. Hair, Risher, Sarstedt, and Ringle [33] p. 2 classify the multivariant methods in first- and second-generation techniques, as it is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Multivariant methods classification.

As seen on Table 1, the PLS-SEM (Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling) is a method to analyze complex relationships between latent variables, allowing the explanation of observed data and a predictable analysis. PLS-SEM was developed to reflect the theoretical and empirical conditions of social and behavioral sciences.

Due to the current research nature, the PLS-SEM is chosen as the ideal model for the representation of the relationships between the studied variables. A surveillance exercise was held to identify the link between PLS-SEM or SEM with the central constructs of the investigation: social capital, SC, and technological learning. A series of equations were looked up on SCOPUS, which are shown in Table 2. The review removed works, papers or articles that did not relate at all to the concepts.

Table 2.

Search equations, results, and authors associated to the relationship between SEM models, social capital, and smart city.

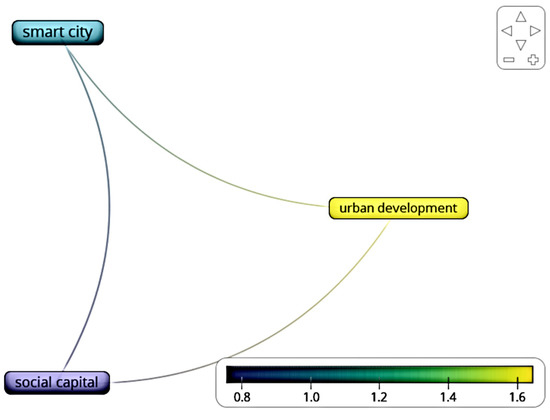

Equation (15) was the one showing more concurrence. It was reduced exclusively to models, SC, and social capital—TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Social Capital” AND model AND “Smart City”), showing 15 articles published between 2013 and 2021. The meta data of these articles was analyzed using VOSViewer, especially the concurrence of key words in which SC, social capital, and urban development are registered mainly. Figure 1 represents the concurrence of words in the works found.

Figure 1.

Concurrence of the key word in VOSViewer of the Works found with the equation: -ABS-KEY (“Social Capital” AND model AND “Smart City”). Source: Own elaboration through VOSViewer.

The equation TITLE-ABS-KEY (“Social Capital” AND “Structural equation modeling” AND “Smart City”), returned two works between 2019 and 2020 with the concurrence of the key words, SC, social capital, urban development, technology transfer, statistical analysis, technology acceptance model, structural equation modelling. Even though the concurrence of key words seems interesting, only two works were related to SEM with the crucial constructs, and no concurrence emerged associating the key words to the theory of resources and capabilities nor technological learning.

Despite there are models built to analyze the link between social capital and the SC, they do not concentrate specifically in the understanding of social capital as a capability of the social structure of the SC. Given this, there is a knowledge gap about the existence of studies that recognize the tripartite relationship between these three constructs through the lens of the resources and capabilities theory.

2.2. Modelling Stages

In a first moment, latent and moderating variables were identified in specialized literature to shape a conceptualization of a model that represented the relationship between them in a technological system of a SC. After, the tangible variables were built from the specialized literature analysis to construct a preliminary-exploratory model and the case was selected to later test the model. Medellín, Colombia, was selected as a SC, given the fact that it is in the IMD Smart City Index, and from 2019 to 2020, it went from position 91 to 72. On its behalf, the technological system chosen was EnCicla, the public urban bicycle system, because for the citizens of Medellin, air pollution, traffic and public transport were top priority among the IMD Smart City Index criteria.

A question was formulated for each tangible variable and validated through a matrix that associated the variable and the corresponding question to literature. The resulting questionnaire allowed to run this preliminary model with 100 registrations. With the data collected, the model was also tested with the main SEM consistency tests: GFI, RMSEA, SRMR, AGF. PLS-SEM passed the three of these four. Baring this in mind, the users’ data of the technological system was requested to EnCicla entity to observe the behavior of the population, giving way to a refinement of the model and to a more qualified sample.

A new syntaxis of the exploratory model was developed and a universe of users from the information handed in by EnCicla entity was segmented in age ranges. A sample of 688 users was configurated, segmented in the same way and surveyed. The percentage of the users per age range of the sample matched the percentage of users per range age from the data provided by EnCicla. With this match, the model was put through the four main SEM consistency tests, and it passed them all.

2.3. Variable Configuration

The SC express itself in a complex structure in which emerges a new intelligence that lies in the resource’s interconnection. Moreover, the SC possesses social capital [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Social Capital has been conceptualized as the capability with which a social structure obtains benefits [24,25].

In the same way, within the theorist of social capital, Portes [49] suggests a systematic treatment that “should distinguish between: (a) the social capital holders (those who make statements); (b) social capital sources (those who agreed on this demands); (c) the resources themselves” [24] p. 6. This systemic treatment that enounces social capital holders, sources, and resources gives place to the constitution of moderating variables, as is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Constituent moderating variables.

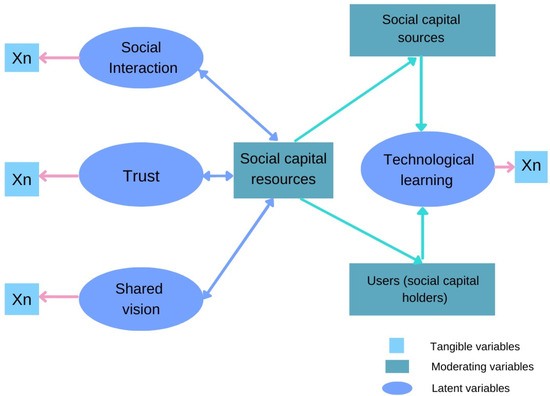

Latent variables are derived from the Social Capital Resources moderating variable and constructed on Kennan and Hazleton [25] and Membiela [26] statements, which understand resources as cognitive, relational, and structural assets. The first one incorporates shared vision [50], among the second ones there is trust [49], and the latter include social interaction [51,52,53].

Technological learning is also a latent variable that represents the sources of social capital. Penrose [54] understood that the growth of an organizational structure derives from the group of resources that it possesses and takes advantage of. The magnitude of the structure is not the most relevant, but rather the talent and learning process of its agents. This offers the achievement of goals and growth; then, the existence and use of the resources has a tight relation to the learning processes. The literature that constitutes all these latent variables can be observed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Constituent literature of latent variables.

After identifying the variables and their relationship with the specialized literature, the theoretical PLS-SEM was built. In Figure 2, the conceptual model is presented.

Figure 2.

Theoretical PLS-SEM. Source: own elaboration.

Considering as an empirical problem the representation of the resources of social capital in the relationship of the users of the public urban bike technological system (Encicla) in Medellín City, and bearing in mind the literature review, a questionnaire of nominal questions based on a Likert scale was constructed to configurate and materialize the tangible variables. A total of 31 tangible variables were built, and for each one of them, a question was formulated. Against each pair of variable and question, the validation was done with authors of the reviewed literature. In Table 5, an example of the theoretical validation exercise is presented with some of the questions, the literature, and the latent and moderating variables.

Table 5.

Example of the theorical validation exercise related with the PLS-SEM variables.

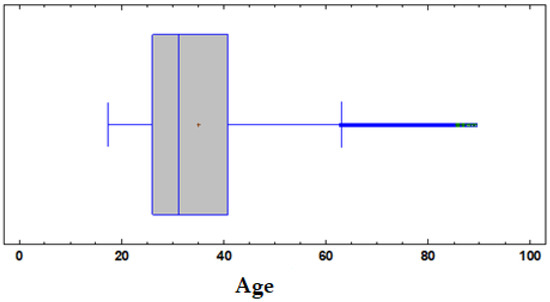

To run the exploratory model, it was important to define the sample, which had to be based on the analysis of final users’ data. This information was requested to EnCicla entity, who provided the information of 106,139 users with age category only because the entity had no wider sociodemographic or a different characterization of the users’ population. This data was analyzed through Statgraphics, and a “Boxes and Mustaches” graph was built with age. This graph is presented below in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Boxes and mustaches of variable in EnCicla users. Source: made in Statgraphics.

As it can be appreciated in Figure 3, the universe behaves according to the age ranges. The ranges that the boxes and mustache graph shows are from 17 to 24, from 25 to 40, from 41 to 62, from 63 and on. The rank with the most concentration is the one from 25 to 60. This can also be seen on Table 6.

Table 6.

Age range of the data of EnCicla.

After the segmentation of users in age ranges, a survey was applied to a group of 824 people, from which 688 were in fact real users of the EnCicla system and whose characteristics were selected for the analysis of the previously explained variables. In Table 7, the age ranges and percentages of final users that are part of the sample are showed and compared with the percent of users per age range from the universe of the data provided by EnCicla entity.

Table 7.

Age ranges from final users surveyed.

The information presented in the previous “Table 7” allowed us to verify that the percentage per age range of the people surveyed as a sample was the closest to the percentage of the same age ranges from the universe. As it can be seen, the data collected was consistent with the data provided by EnCicla entity based on age ranges. This analysis helped shape the representative sample of the total population of final users.

2.4. From the Conceptual Model to the Measurement Model

The information presented above gives place to the generation of the main and secondary hypotheses for the exploratory model of the measurement construction exercise.

Hypothesis:

there is significant relationship between the latent variables (social interaction, trust, and shared vision) with the latent variable technological earning.

Null Hypothesis:

there is no significant relationship between latent variables (social interaction, trust, and shared vision) with the latent variable technological earning.

Secondary Hypotheses with chosen variables:

- First: Social interaction variable is explained through trust and shared vision;

- Second: Trust variable is explained through social interaction and shared vision;

- Third: Shared vision variable is explained through social interaction and trust;

- Fourth: Technological Learning is explained through trust, social interaction, and shared vision.

Once the instrument to collect information was applied, the data gathered was processed. This made possible the calculation of the simple average and the standard deviation of every column of answer to later create a normalized database. This means, every datum minus its average and that result divided by the deviation: normalized = (datum – average)/deviation. Subsequently, the analysis of data was done in R Software following the next steps:

- 1.

- The structural equations model (SEM) library is charged: library (lavaan).

- 2.

- The data matrix is built based on the correlations’ matrix.

- 3.

- The complete correlation matrix is obtained by first using the getCov to convert the input data matrix (the diagonal above) into a complete matrix. The next conversions were considered: (a) correlations matrix; (b) sds ( ): the typical deviations were represented with NULL because there were none; (c) names ( ): items’ names.

- 4.

- The names of the tangible variables were checked to be correctly filled out in the matrix by using the command: matriz.cov.

- 5.

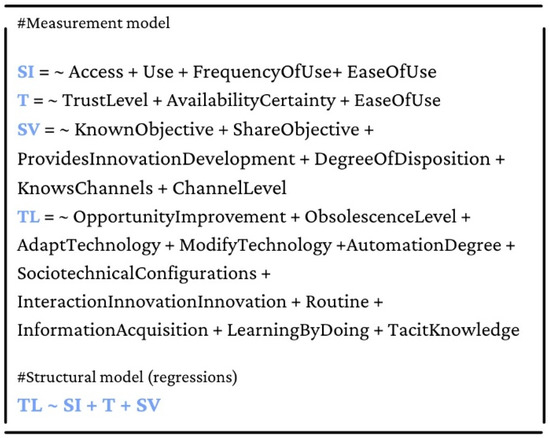

- Once the complete correlation matrix was obtained, the model was specified. This means that the specified conceptual model presented in Figure 2 was translated to build the exploratory measurement model, whose syntax in lavaan was: variable =~ item1 + item2 + item3.

- 6.

- Building the exploratory measurement model considering the relationship between variables was the next step. In this case, it is the direct effects. The syntax for this relationship was: dependent variable ~ var. independent1 + var. independent2. In other words, Technological learning (hereinafter TL) ~ Social interaction (hereinafter SI) + Truth (hereinafter T) + Shared vision (hereinafter SV):TL ~ SI + T + SV

- 7.

- The evaluation and estimation of the model was then done through the development of the software SEMVIZ. v 1.0 [47], which allowed the visualization of SEM analysis and interpretation through the server: http://162.241.38.68:3838/semviz/ (accessed on 21 October 2021). The step-by-step process for the application was:

- The CVS the normalized data file and the labels file were charged in the “Data Gestion SET module” in explicative variables and label sections, correspondingly.

- With the structural measurement model syntaxis, the syntaxis for the software was built. It is important to bear in mind that this latter syntaxis, was constructed in an exploratory manner because there was a tighter relationship between some data and the modeling than other. Some explorations were carried out with groups of tangible variables considered for each group of latent variables. This gave way to the refinement of the syntaxis.

- In the “Specify and Estimate” module, the syntaxis was linked. This one is presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Syntaxis built for the SEMVIZ v 1.0 validation. Source: own elaboration.

Figure 4. Syntaxis built for the SEMVIZ v 1.0 validation. Source: own elaboration.

- 8.

- With the specification and estimation of the syntaxis, it was possible for the software to build a graphic model that represented the relationship between the variables. This graphic model is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Graphical analysis driven SEM. Source: SEMVIZ ® with the data obtained.

Figure 5. Graphical analysis driven SEM. Source: SEMVIZ ® with the data obtained.

3. Results

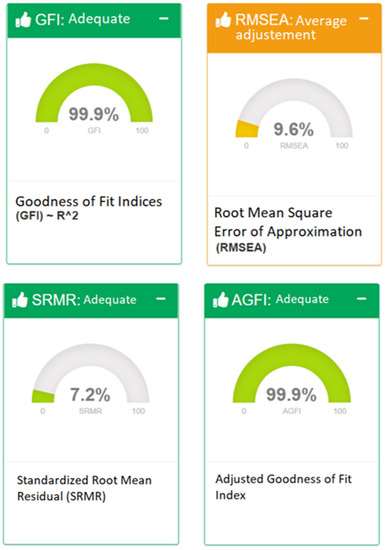

On the “Goodness of Fit Analysis” module, the section “modeling fit” was reviewed. The four principal tests for the SEM modeling were examined. The approval of the principal tests was validated: GFI, RMSEA, SRMR, and AGFI. The syntaxis passed all of them successfully. This is evidenced in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Reference criteria for absolute fit. Source: SEMVIZ ® with the data obtained.

The previous figure shows that the model passed four out of four main tests, meaning it approved the reference criteria for an absolute adjustment, considering the following:

- Goodness of Fit Indices (GFI) ~ R^2. GFI explains the level of variances accounted for by the estimated population variance. In this case, the GFI is adequate as it scored a 0.99, positioning it over 0.95, which is a recommended level [63].

- Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) presented an inferior level to 0.10, which was 0.096, meaning an average adjustment. Even though a level below 0.05 is highly recommended, the model passed the test with the adjustment obtained [64].

- Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) presented a level below 0.08, which is highly recommended, with a score of 0.072. This means the test was approved by the model [65].

- Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) presented a level above 0.90 with 0.99 that allows the model to pass this test [63].

On its behalf, the Chi2 did not score a value near the degrees of freedom. Given this, the ratio (Chi2/DF) was not accepted. This scored a 7.33, when a value near 3 is recommended.

The low values of P(>|z|) in the latent variables mean that the P(>|z|) value in the general model must be 0.000. This value allows us to evaluate the null hypothesis: there is no significant relationship between latent variables (social interaction, trust, and shared vision) with the latent variable technological earning. To not reject this hypothesis, a value of 0.05 was needed. Since the selection of users for the exercise, the tendency to reject it was present as all the information came from an effective user of the system as an effective user of the social capital resources expressed in a relationship with technological learning. In other words, the null hypothesis was expected to be rejected, whereas the main hypothesis was expected to be validated.

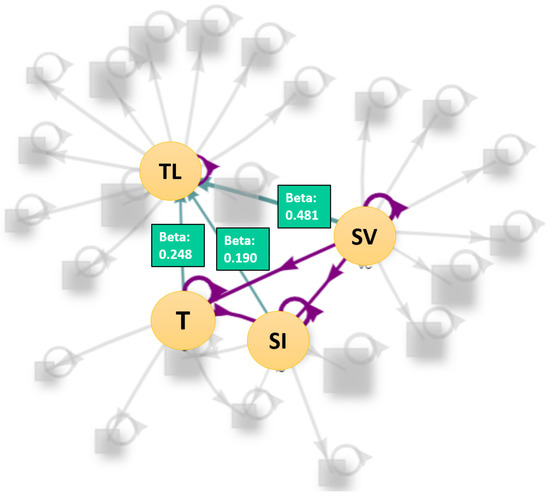

As the exploratory model adjusted itself in major consistency statistics to explain the problem, it can be recognized from the results of this model that the main hypothesis, which establishes that there is a significant relationship between the mentioned variables, is validated. This means that there is, effectively, a significant relationship between the latent variables. The validation of the main hypothesis is also given by the beta values of the latent variables, which are the values of the estimation of the model. These are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Latent variables’. Beta values Source: SEMVIZ ® with the data provided.

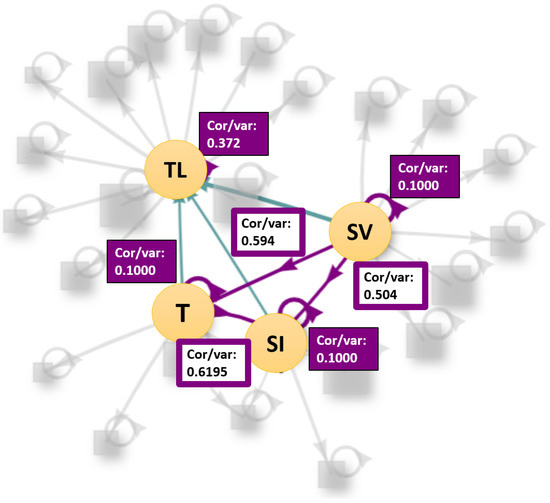

The correlation/variance values show that the interaction between the latent variables of social interaction, trust, shared vision, and technological learning is positive. These values are expressed in Figure 8. The values allow us to validate all secondary hypotheses.

Figure 8.

Correlation/variance values of latent variables. Source: SEMVIZ ® with the data provided.

The analysis of the model demonstrates that there is a relationship between the resources of social capital, as latent variables, with technological learning, also a latent variable, that represents social capital’s sources. One of the most noteworthy aspects in the regressions’ analyses is the greater relationship significance between social interaction and trust to explain technological learning. Shared vision represents, on its behalf, some level of relationship, but the other two resources of social capital tend to be more representative.

This means that social interaction, trust, and shared vision (social capital’s resources) and technological learning (social capital’s source) can be represented through an exploratory PLS-SEM built on the resources and capabilities theory. Given this, it can be concluded that the resources of social capital affect technological learning in the public, urban bicycle system in Medellín.

4. Discussion

In general terms, the model was built based on the categorical configuration derived from specialized literature analysis. From the latent and moderating variables, a conceptual model was constructed and then, with the configuration of the tangible variables and the design of the survey, the exploratory-measurement model was assembled. By surveying EnCicla technological system users, the final exploratory model was built. This one passed the four main tests for SEM models and became a model that represents resources of social capital and technological learning from the social capital analysis as a capability of the Smart City.

The Surveillance and Theorization

From the surveillance and theorization exercises, it was possible to recognize that the SEM is a plausible way to analyze the main categories and their relationships, transcending from the theoretical reflections and a literature review to a measurement model that validates the relationships deduced from said literature review. From an exploratory model, SEM allowed us to understand the importance of the chosen tangible variables and how these have an impact on latent variables. From the configuration of the exploratory model, a contribution to social knowledge about how technological learning represents a source of social capital can be made.

PLS-SEM was helpful to analyze complex relationships between latent variables, to explain the data observed, and to demonstrate the theoretical and empirical conditions of the suggested research gap. The knowledge gap on how to analyze the social capital of a smart city capability manifested in a social structure was reduced.

The survey was theoretically validated and related to the tangible variables. Each one of these was represented by a question, and every group of questions was as well related to a latent variable, just as these ones were linked to moderating variables. This led to the conclusion that for a PLS-SEM to have consistency, the theoretical validation is highly significant. In relation to an empirical problem, said validation allows for a greater refinement of the model.

Finally, the multivariate analysis made possible the study of the universe of the users and, therefore, allowed the sample understanding of the data. Analyzing the universe by age ranges and configuring these ranges by percentages helped reach a collection of data from the sample’s information based on the behavior of the total population. On the other hand, the estimation and evaluation of the model through SEMVIZ. v 1.0 [66] enabled a high-level visualization for the analysis and interpretation of the structural model and the exploratory ones. The data analyses are the consequence of this tool as a possibility to understand social models and concepts that share resemblance to the ones in the resulting model of this investigation.

5. Conclusions

One of the main contributions of this work is the design of a PLS-SEM that enables the representation of the resources of social capital and technological learning of technological systems in a smart city. Namely, they are not only abstract concepts translated into measurable variables, but ones that represent social capital’s resources (social interaction, trust, and shared vision) with its source (technological learning) in a Smart City. There is a direct relationship between theory and the identified empirical problem. A system of measurement and interaction between variables is configured which dialogs with the perceptions of users in the Smart City studied.

Theoretically speaking, this investigation contributes to the construction of knowledge associated with a Smart City and allows its conceptual expansion. The Smart City is described as an organizational structure, and this establishes a theoretical link between theories about organizations (especially those related to resources and capabilities) and social capital. Thus, if social capital is understood as a capacity of organizational structures and Smart Cities are expressed in organizational structures, then social capital is a capacity of Smart Cities. This advance in the theoretical consolidation on organizations and the Smart City allows the resources of social capital and technological learning to be studied as part of the configuration of smart cities and, therefore, to the achievement of the model that represents them.

Methodologically, the design enabled the construction of a PLS-SEM and its validation. Through this investigation, the possibility of replicating the model in subsequent studies is evidenced. The selection of the methodology contributed to closing the existing knowledge gap previously mentioned. Likewise, it revealed variables that were only evidenced after the systemic literature review was carried out. An exploratory model was necessary to translate the theoretical model since the tangible variables required data of the identified casuistry.

Given this, the designed methodology for this investigation could be replicated in other analysis processes of technological systems in a Smart City when it becomes necessary to represent social capital resources and their relationship with technological learning since the methodology not only allowed the construction of the model proposed, but also its expansion and subsequent description after the establishment of the relationship between the qualitative and the quantitative.

Smart Cities possess diverse elements in which aspects of environmental and economic sustainability stand out. This is how it is considered that the main cities in the world choose as a public policy: (1) those smart cities that require an integrated use of diverse information and communication technologies, among which mobile IP networks, clouding, big data, and Internet of Things stand out, and (2) those that are a sustainable model to grow at the rate that urban population does [67]. Thus, this makes technology integrate with daily activities and with all sectors of society, which requires a general vision in the macro level in a city to embrace technology as a fundamental element of development in a way that serves to improve the management of the government and the quality of life of the citizens.

In order to achieve the implementation of Smart City projects, it is necessary to apply new technologies and tools in an integrated way in the participation of different stakeholders, bringing together the efforts and initiatives within a collaborative decision-making process [67]. It is from the interaction between stakeholders that deployment models of the Smart City emerge where the role of each one of them is established and the balance needed between them to achieve the city’s objectives. The present built model contributes to this challenge that includes technologies and sustainability as configuration elements of the Smart City.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M. and S.Q.; methodology, J.M. and E.C.M.; validation: J.M. and E.C.M.; formal analysis, J.M.; investigation, J.M.; resources, J.M.; data curation, J.M. and E.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, J.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M.; visualization, J.M.; supervision, S.Q.; Project administration, S.Q.; funding acquisition: S.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. It was funded with personal resources.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved.

Data Availability Statement

The data of that study was provided by the public bicycle system EnCicla of the Metropolitan Area of Medellín city. The data is public but must be requested to the entity EnCicla. The data of the citizens that participated in the study was archived by the authors to guarantee the declaration of confidentiality.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana for the funding and to GTI Research Group of the Doctoral Program in Technology and Innovation Management for the participation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Castells, M. The Informational City: Information Technologies, Economic Restructuring and The Urban Process (La Ciudad Informacional: Tecnologías de La Información, Reestructuración Económica y El Proceso Urbano); Alianza Editorial: Madrid, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sassen, S. The global city: An introduction to the concept and its history. Brown J. Word Aff. 1995, 11, 27–43. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P.; van Kempen, R. Globalizing Cities. A New Spatial Order; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Veltz, P. Mondialisation, Villes et Territoires. L’economie D’archipe; Presses Universitaires de France: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Amendiola, G. The Postmodern City. Magic and Fear of the Contemporary Metrópolis (La Ciudad Postmoderna. Magia y Miedo de La metrópolis Contemporánea); Celeste ediciones: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- De Mattos, C.A. Metropolization and suburbanization (Metropolización y suburbanización). EURE 2001, 27, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Postmetropolis: Critical Studies of Cities and Regions; Blackwell of World Affairs: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Heineberg, H. Metropolis in the Globalization Process (Las Metrópolis en el Proceso de Globalización) Revista Bibliográfica de Geografía y Ciencias Sociales; Universidad de Barcelona: Barcelona, 2005; pp. 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W. Smart Cities (Ciudades Inteligentes); Uocpaper, Universitat Oberta de Catalunya: Barcelona, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, T. City Bran; Paidos: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Naam, T.; Pardo, T. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people, and institutions. ACM Int. Conf. Proceeding Ser. 2011, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, J.R. (October–January) The human component of smart cities (El componente humano de las smart cities). Rev. TELOS 2017, 105, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Giffinger, R.; Gudrun, H. Smart cities ranking: An effective instrument for the positioning of the cities? ACE Arch. City Environ. 2010, 4, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollands, R.G. Will the real smart city please stand up? City 2008, 12, 303–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.; Eckman, B.; Hamilton, R.; Hartswick, P.; Kalagnanam, J.; Williams, P. Foundations for Smarter Cities. IBM J. Res. Dev. 2010, 54, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; Del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart Cities in Europe. J. Urban Technol. 2021, 18, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffers, H.; Komninos, N.; Pallot, M.; Trousse, B.; Nilsson, M.; Oliveira, A. Smart cities and the future internet: Towards cooperation frameworks for open innovation. In The Future Internet Assembly; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2011; pp. 431–446. [Google Scholar]

- Chourabi, H.; Nam, T.; Walker, S.; Gil-Garcia, J.R.; Mellouli, S.; Nahon, K.; Pardo, T.A.; Scholl, H.J. Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 45th Hawaii International Conference on System Science, Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 January 2012; pp. 2289–2297. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission: Digital Agenda for Europe. Smart Cities: A Europe 2020 Initiative. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/eu-regional-and-urban-development/topics/cities-and-urban-development/city-initiatives/smart-cities_en (accessed on 8 March 2022).

- Mocholí, A. Smartcities’ for Smart Citizens. 2016. Available online: http://anamocholi.com/smartcities-paraciudadanos-inteligentes/ (accessed on 4 October 2019).

- Sikora-Fernández, D. Smart city development factors (Factores de desarrollo de las ciudades inteligentes). Rev. Univ. De Geogr. 2017, 26, 135–152. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318662037_Factores_de_desarrollo_de_las_ciudades_inteligentes (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Valderrama, N. Smart Cities. Basic Concepts; Universidad de Manizales: Manizales, Colombia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Renard, L.; St-Amand, G. Capacité, capacité organisationnelle et capacité dynamique: une proposition de définitions. Les Cah. Du Manag. Technol. 2003, 13, 43–56. [Google Scholar]

- Portes, A. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennan, W.R.; Hazleton, V. Internal public relations, social capital, and the role of effective organizational communication. In Public Relations Theory II; En, C.H., Botan, V.H., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 311–338. [Google Scholar]

- Membiela, M.E. Social Capital, Relational Goods and Revealed Subjective Well-Being. A Contrast of Lin’s Model (Capital Social, Bienes Relacionales y Bienestar Subjetivo Revelado. Una Contrastación del Modelo de Lin); Universidade da Coruña: Coruña, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cimoli, M.; Dosi, G. Tecnología y Desarrollo. Algunas Consideraciones Sobre Los Recientes Avances en La Economía de La In-Novación. El Cambio Tecnológico Hacia El Nuevo Milenio, Debates y Nuevas Teorías; Icaria-Fuhem: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dollinger, M.J. Entrepreneurship: Strategies and Resources; Irwin: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Malerba, F. Learning by Firms and Incremental Technical Change. Econ. J. 1992, 102, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hippel, E.; Tyre, M.J. How learning by doing is done: Problem identification in novel process equipment. Res. Policy 1995, 24, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Institute for Management Development. Smart City Index; IMD ORG: Suiza, Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Escobedo, M.T.; Hernández, J.Á.; Estebané, V.; Martínez, G. Structural Equation Models: Characteristics, Phases, Construction, Application and Results. (Modelos de Ecuaciones Estructurales: Características, Fases, Construcción, Aplicación y Resultados); Universidad Autónoma de ciudad Juárez: Chihuahua, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, N.; Oliveira, T. Factors affecting behavioural intention to adopt e-participation: Extending the UTAUT 2 model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on IS Management and Evaluation (ECIME), Evora, Portugal; 2016; pp. 322–325. [Google Scholar]

- Sepasgozar, S.M.; Hawken, S.; Sargolzaei, S.; Foroozanfa, M. Implementing citizen centric technology in developing smart cities: A model for predicting the acceptance of urban technologies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 142, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Guimarães, J.C.F.; Severo, E.A.; Júnior, L.A.F.; Da Costa, W.P.L.B.; Salmoria, F.T. Governance and quality of life in smart cities: Towards sustainable development goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, G.; Mordonini, M.; Tomaiuolo, M. Adoption of Social Media in Socio-Technical Systems: A Survey. Information 2021, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattarai, K.; Conway, D. Urban Growth. In Contemporary Environmental Problems in Nepal; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 201–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, S. Using multivariate statistical methods to assess the urban smartness on the example of selected European cities. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortino, G.; Fotia, L.; Messina, F.; Rosaci, D.; Sarné, G. A meritocratic trust-based group formation in an IoT environment for smart cities. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 108, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhametov, D. Smart city: From the metaphor of urban development to innovative city management. TEM J. 2019, 8, 1247–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israilidis, J.; Odusanya, K.; Mazhar, M.U. Knowledge Management in Smart City Development: A Systematic Review. In Proceedings of the 20th European Conference on Knowledge Management, Universidade Europeia de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal, 5–6 September 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmalian, A.; Ramaswamy, M.; Rasoulkhani, K.; Mostafavi, A. Agent-Based Modeling Framework for Simulation of Societal Impacts of Infrastructure Service Disruptions during Disasters. ASCE Comput. Civ. Eng. Workshop 2019, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, S. Community informatics tools relating to smart city developments: Social software, online participation, crowdsourcing. [Az okos város fejlesztesekhcz kapcsolódó közösségi i n form at i kai eszközök: Társadalmi szoftver, online participáció, crowdsourcing]. Inf. Tarsad. 2016, 16, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tawalbeh, L.A.; Basalamah, A.; Mehmood, R.; Tawalbeh, H. Greener and Smarter Phones for Future Cities: Characterizing the Impact of GPS Signal Strength on Power Consumption. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valetto, G.; Bucchiarone, A.; Geihs, K.; Büscher, M.; Petersen, K.; Nowak, A.K.; Rychwalska, A.; Pitt, J.; Shalhoub, J.; Rossi, F.; et al. All Together Now: Collective Intelligence for Computer-Supported Collective Action. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Self-Adaptive and Self-Organizing Systems Workshops, Cambridge, MA, USA; 2015; pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannella, C.; Iosue, A.; Tancredi, A.; Cicola, F.; Camusi, A.; Moggio, F.; Coco, S. Scenarios for active learning in smart territories. Interact. Des. Archit. 2013, 16, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Perillo, G. Smart models for a new participatory and sustainable form of governance. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 179, 1227–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzi, B. The Sources and Consequences of Embeddedness for the Economic Performance of Organizations: The Network Effect. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, A.; Sensenbrenner, J. Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action. Am. J. Sociol. 1993, 98, 1320–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, M.S. Problems of Explanation in Economic Sociology. In Networks and Organizations: Structure, Form, and Action; Nohria, N.R.E., Ed.; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 25–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S. Constitutionalism versus Relationalism: Two Views of Rational Choice Sociology; Falmer Press: London, UK, 1996; pp. 299–311. [Google Scholar]

- Hakansson, H.; Snehota, I. Developing Relationships in Business Networks; Routledge: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, J.S. Foundations of Social Theory; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Dutrénit, G. Learning and Knowledge Management in the Firm. From Knowledge Accumulation to Strategic Capabilities; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, S.; Giraldo, D.P. El Aprendizaje en Los Sistemas Regionales de Innovación Desde la Perspectiva de la Modelación Basada en Agentes; Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana: Medellín, Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rafi Khan, S. Learning from South Asian Successes: Tapping social Capital. South Asian Econ. J. 2006, 7, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, M.; Kleinman, D.L. Bringing Pierre Bourdieu to Science and Technology Studies. Minerva A Rev. Sci. Learn. Policy 2011, 49, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, A.S.; Holionko, N.G.; Tverdushka, T.B.; Olejarz, T.; Yakymchuk, A.Y.; Kiev National Economic University named after Vadim Hetman; International Institute of Business (IIB); Rzeszow University of Technolog y Rzeszow; National University of Water and Environmental Engineering. The Strategic Management in Terms of an Enterprise’s Technological Development. J. Compet. 2019, 11, 40–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.; Ghoshal, S. Social Capital and Value Creation. The role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 464–476. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero, S. Resources and Capabilities as Key Elements of Learning. Ph.D. Dissertation, Universidad Nacional, Medellín, Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog, K.G.; Sörbom, D. LISREL V: Analysis of Linear Structural Relationships by Maximum Likelihood and Least Squares Methods; National Educational Resources: Chicago, IL, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, J.H.; Lind, J.C. Statistically Based Tests for the Number of Common Factors; Psychometric Society Annual Meeting: Iowa City, IA, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M. Theory and Implementation of EQS, a Structural Equations Program; BMDP Statistical Software: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez, M. Aplicación SEMVIZ. 2019. v 1.0. Available online: http://162.241.38.68:3838/semviz/ (accessed on 21 October 2021).

- Zona-Ortiz, A.T.; Fajardo-Toro, C.H.; Pirachicán, C.M.A. Propuesta de un marco general para el despliegue de ciudades inteligentes apoyado en el desarrollo de Iot en Colombia. Rev. Ibérica Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2020, 28, 894–907. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).