Abstract

This study uses a random parameters logit (RPL) model to estimate the Taiwanese preference for northern shrimp (NS) products (NSP) with the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) label. The estimated results show that, ceteris paribus, the marginal willingness to pay (MWTP) of Taiwanese consumers for NSP with the MSC label is up to New Taiwan dollar (NTD) 84.86 in comparison to products without the label. Moreover, the price of MSC-labeled NSP has a positive effect on the quantity demanded by Taiwanese consumers. They also prefer products in smaller packages and with shorter certification periods. The positive effect can be explained by the Veblen effect or the fact that sometimes prices are perceived as signals of product quality. However, the effects of preference for smaller packages and shorter certification periods are minimal compared with the effects of preference for MSC-labeled products. When consumers are unfamiliar with products or labels, a high price is a viable marketing strategy. However, the advantage cannot sustain the promotion of products and labels.

1. Introduction

Overfishing of northern shrimp (NS; Pandalus borealis) has threatened the sustainability of fisheries and caused substantial damage to the ecosystem. In Greenland and Canada, the fishable biomass of northern shrimp stock has been declining since 2008 [1], and the resources have been depleting at alarming rates since 2012. In 2014, the United States banned NS fishing in the Gulf of Maine, because the stock was on the verge of collapse [2]. In addition to the threats to fisheries, overfishing also poses risks to the ecosystem. In the Northern Atlantic, NS is a food source for many higher predators, such as cod, flatfish, skate, and seals. The reduced NS biomass would inevitably affect the entire food chain. Furthermore, the by-catch in fishing NS also threatens the existence of some endangered species, such as the leatherback sea turtle and the Atlantic wolffish (Anarhichas lupus) [3,4]. Therefore, the management of NS fisheries is an essential topic in economics and policies on marine environment and resources. One specific management tool is the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Fisheries Standard (MSC Standard). (There are other well-known third party certification and ecolabeling schemes in fisheries, such as Friend of the Sea (FOS), KRAV, and Naturland [5,6,7]. FOS is a voluntary market-driven certification scheme which certifies both farmed and wild-caught products. KRAV is mainly operated in the area of organic food in the region of Scandinavia and has accepted applications for fish stocks outside Scandinavia since 2010. Naturland is formed to provide ecolabeling for organic agriculture. These three ecolabeling schemes are less valid than MSC, applied to wild-capture fisheries only, for NS fisheries.)

The MSC Standard aims to ensure sustainable wild fisheries by applying principles such as “sustainable fish stocks,” “minimizing environmental impact,” and “effective fisheries management.” Bellchambers et al. [8] suggest that fisheries or governments can reduce the impact of NS fisheries on the NS biomass and ecosystem by complying with the MSC Standard. However, note that such benefit comes at a high cost, in the range of USD 15,000–120,000, for complying with the provisions of the MSC Standard, completing the MSC certification process, and acquiring the MSC label. In addition, the cost involved in collecting necessary fishing data, and to conduct the required assessment for certification is significant too. Wakamatsu and Wakamatsu [9] estimate that the initial assessment cost is in the range of USD 2000–20,000, while the complete assessment may cost up to USD 10,000–50,000.

Considering the high extra cost of acquiring the MSC label, fisheries are reluctant to comply with provisions in the MSC Standard if the label fails to generate profits for them [10]. Nevertheless, empirical results show that MSC-labeled products are more competitive than those without the label. Oishi et al. [11] find that consumers are willing to pay higher prices for MSC-labeled products, and the premium is in the range of 10–20% of the total price. Bronnmann and Asche [12], Carlucci et al. [13], Hori et al. [14], and Lim et al. [15] also draw similar conclusions.

Although these studies demonstrate consumer preference for MSC-labeled products, they do have certain limitations. First, the lack of national representation of the samples makes it difficult to estimate the nationwide consumers’ marginal willingness to pay (MWTP) for the MSC label. For example, Bronnmann and Asche [12] investigate using randomly sampled consumers from retail markets, and the sample selection bias is inevitable in their collected data [16]. Lim et al. [15] use an online survey to investigate American consumers’ MWTP for the MSC label. The authors caution that the methodology has selection bias. Hori et al. [14] and Carlucci et al. [13] also use online surveys to investigate Japanese and Italian consumers’ preference for the MSC label, respectively. Once again, their results involve the selection bias, as Lim et al. [15] cautions. Although the sales inventory system of retailers can be used as an input of actual market data to investigate the MSC label premium [17], the database cannot identify whether the purchasers are final consumers and distinguish purchases according to their economic and social characteristics. Therefore, the database cannot be used to estimate consumers’ MWTP for the MSC label.

Second, current studies on the MSC label do not address consumers’ preference for the duration of the certificate. For example, Bronnmann and Asche [12], Carlucci et al. [13], Hori et al. [14], Jaffry et al. [18], Lim et al. [15], and Roheim et al. [17] use a dummy variable to indicate whether the products have the MSC label. Such specifications can only estimate consumers’ preference for the MSC label rather than for its certification period. However, the certification period relates to the average cost incurred by fisheries in applying for the MSC label. The longer the period, ceteris paribus, the larger the quantity of total landings in the period, thereby, a lower average cost in acquiring the MSC label is achieved. The lower cost acts as the incentive to fisheries to comply with the MSC standard and acquire the MSC label. If consumers prefer shorter certification periods, a longer period would be less attractive to consumers, even if it can help lower the product cost for fisheries. Insights of consumers’ preference for the certification period can be used to estimate a period that has the maximum benefit to fisheries, and thus, promote the coverage of the MSC label. Therefore, the insights have high practical value, as the MSC can leverage them to set a more appropriate certification period for the label.

Moreover, current studies on MWTP for the MSC label do not cover consumers around the globe in terms of their preference for the label. Current studies on this topic are mostly from countries such as the UK, Germany, Denmark, the US [15], Italy [13], Japan, and Sweden [19], and do not involve the assessment of international consumers’ average preference for the MSC label. Such deficiency may hinder the promotion and development of the MSC label at the international level.

Except for the above issues, the current literature does not specifically provide strong motivation to NS fisheries in applying the MSC label. The crucial issue is the lack of understanding of the premium of NSP with the MSC label. Current studies mostly target cod [12,18,19], haddock [18], pollock, oysters [13], saithe [12], salmon [12,18,20], trout [21], and tuna [15,18]. Some studies on prawn/shrimp, such as Jaffry et al. [18], do not specify whether the prawn/shrimp refers to NSP. Therefore, there is insufficient data to assess the effect of the MSC label on the premium of NSP directly. In economic research on environmental resources, with insufficient direct data, it is still possible to evaluate premium using the benefit transfer method. Nevertheless, because the studies related to market incentives of the MSC label focus on a few countries, and most studies on individual countries are not fully representative, the benefit transfer method cannot be used to transfer results from the MSC label premium on other fishes to the NSP.

Given the potential of applying the MSC standard in improving NS fishing methods, which are the key in safeguarding sustainable NS fishing and biodiversity in the NS habitat, it is crucial to assess the size of the MSC label’s market incentives. The assessment results are instrumental to the design and promotion of NS fishing methods that comply with the MSC standard. Therefore, this study assesses the consumers’ MWTP or the premium of MSC-labeled NSP. As most current studies on MSC label premium concentrate on a few European countries and data for research are limited, Taiwan is selected as the location of study to increase diversity in terms of countries covered and to contribute to cross-country analysis of the international standard. As the MSC label’s certification period is also a factor affecting fisheries’ average cost and willingness to apply for the label, and no other study has addressed this factor, this study also addresses consumers’ preference for the certification period.

2. Research Methods

In terms of research methods, this study adopts discrete choice experiments (DCEs) to investigate and analyze the data. Although market data on actual purchases [17] or questionnaires [13,14,15,18] can be used to assess the premium of the MSC label, they do not contain information on the MSC label’s certification period. Therefore, this study does not consider them, as they cannot be used for assessing consumers’ period preference—one of the targets of this study. The questionnaire data can be analyzed by the contingent valuation methods (CVMs) or DCEs. However, the latter can be used to assess more diversified policy scenarios. The DCEs are more suitable for this study, as they investigate diversified scenarios involving consumers’ preference for certification periods and a combination of other features. Moreover, DCEs derive theoretically from the economic model constructed by Lancaster [22] and are used in many areas. They are often used in investigating consumers’ preference for the MSC label. Considering the above advantages [14], this study uses DCEs.

2.1. Questionnaire Design

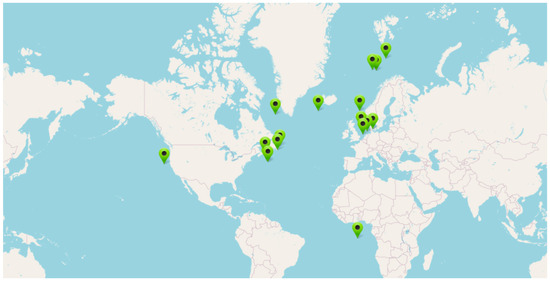

The data needed for DCEs analysis are generated from a questionnaire survey. In designing the questionnaire, the first step is identifying the key factors affecting decision-making and demographic variables, which affect a respondent’s preference [23]. In deciding on the attributes and their respective levels, the results of other studies and qualitative methods (e.g., literature review, focus group study, and participant observation) are valuable to identify the most appropriate attributes and levels for the study [24]. Specifically, this study uses the literature review to discuss current research results and shortcomings. The conclusions are drawn to inform the decisions on the attributes to be covered by the study, including the certification period, unit price, and package size. The potential values of the levels of each attribute are the results of the literature review and participant observation. The specific certification periods are from the MSC website, while the unit prices and package sizes are from observing NSP sold in the Taiwan market (package size is 250 g, and the unit price per 100 g is NTD 50). In line with Ryan et al. [25], other levels were assigned after deciding on the potential values of the levels of each attribute (Table 1, Figure 1). After deciding on all the levels of each attribute, orthogonal design methods were used to generate alternatives. A total of six scenarios were constructed by combining these alternatives randomly, with each scenario containing five alternatives (Table 2).

Table 1.

Status of MSC-certified Northern Prawn (Pandalus borealis) Fisheries.

Figure 1.

Locations of MSC-certified Northern Prawn (Pandalus borealis) Fisheries (Copyright 2021 The Marine Stewardship Council.).

Table 2.

Overview of Attributes and Attribute Levels.

The draft questionnaire developed was put to the test in the form of a one-to-one cognitive interview to ascertain whether the respondent could understand the messages to be conveyed by the questionnaire. The confusing text was revised accordingly [26,27,28,29]. The questionnaire was finalized after the test comprised of three sections. The first section introduced NSP and MSC certification, including the topics of NSP, NS fisheries, MSC certification, cost of the certification, and the size of the current market premium of the MSC label. The second section provided scenarios to be selected (Table 3). The third section covered basic personal data.

Table 3.

An Example of the Questionnaire.

2.2. Method of the Questionnaire Survey

This study uses the “stratified multi-stage probability proportional to size sampling” adopted by the national Taiwan Social Change Survey for random sampling. The interval sampling with probability proportional to size (PPS), for each strata of regions was conducted in three stages for “strata of regions,” “townships and districts,” and “individuals.” A total of 358 townships and districts in Taiwan were divided into seven “strata of regions” according to eight variables. They were the “rural employment as a proportion of total employment,” “non-rural employment as a proportion of total employment,” “professionals and executives as a proportion of total employment,” “population between the ages of 15 and 64 as a proportion of the total population,” “population of age 65 and over as a proportion of the total population,” “population with university education and above as a proportion of the total population,” “population density,” and “population growth in five years.” For details on “strata of regions” and the sampling stages, please refer to the 2018 Taiwan Social Change Survey [30]. The sample was from the population at the age of 18 and above in Taiwan. The survey was carried out during October–December 2019. A total of 608 valid questionnaires were collected.

2.3. Models

The utility value of a specific alternative selected by respondents in a scenario can be represented by the following Equation:

where is the utility when the respondent n selects the alternative i. As the real utility acquired by the respondent cannot be observed, is used to represent the observed utility when the respondent n selects the alternative i, and is a random parameter, representing an error item that cannot be measured in the model. is the set of alternatives that can be selected by the respondent n.

The estimation method of Equation (1) depends on the distribution function of . For an estimated result of Equation (1) implied by the respondent’s decision-making rule of utility maximization, the distribution function that satisfies the conditions of utility maximization must be used. As it is proven that independent and identically distributed type 1 extreme value distribution satisfies the conditions [31], this study assumes that has such distribution. Under the assumption, the respondent n’s selection results adhere to the axiom of independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA). Equation (2) shows the probability that the respondent selects the alternative i, as follows:

The estimation of Equation (2) still requires the understanding of the function form between and attributes. Assuming that is a linear function of the attributes, as the following equation shows:

where represents the Kth attribute when the respondent selects the alternative i, is the parameter of the , and the alternative specific constant () is the indicator variable, which indicates whether the alternative i is selected and encompasses the characteristics not captured by the attributes [32].

Under the above assumptions, the marginal rate of substitution (MRS) between the attributes s and k can be expressed as shown in Equation (4):

Set s as the attribute that represents price (such as cost), then Equation (4) donates the respondent’s MWTP for the attribute k (or as shown in Equation (5)):

If a respondent’s behavior does not adhere to the IIA axiom, the issue of heterogeneous preference arises, which a random variable can capture. The can be rewritten as in such cases, where denotes the respondent n’s heterogeneity. The model also transforms from a multinomial logit (MNL) model to an RPL model [33] and Equation (2) needs to be rewritten as Equation (6), as follows:

The results estimated in Equation (6) can still be applied to Equations (4) and (5).

There is no prescriptive requirement in an RPL model on which variable should incorporate random effects. To avoid specification error in terms of the random effects and its implications on the results and policy recommendations, this study specifies four models based on whether random effects are present in the attributes and personal characteristics. Model 1 does not incorporate personal characteristics, and only price is specified as encompassing the random effects. Model 2 does not incorporate personal characteristics, but all the variables are specified as encompassing the random effects. Model 3 is an extension of model 1, by incorporating personal characteristics in model 1. Model 4 is an extension of model 2, by incorporating personal characteristics in model 2, and all the attributes and personal characteristics are specified as encompassing the random effects. The effects of personal characteristics are represented by the cross terms between each characteristic and the ASC. Table 4 presents the results of analyzing the four models. The sign of the estimated value for each variable does not change for different models. Except for ASC, the estimated value also does not change substantially for different models. Model 2 has the best fit against the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Moreover, all the values for variables in model 2 are statistically significant at the level of 0.01. For concision, only the results from model 2 are discussed below.

Table 4.

Summary Statistics of Sample.

3. Results

The results (model 2, Table 5) show that Taiwanese consumers have positive preference, and the conclusion is derived from the estimates of ASC. The ASC indicates whether the consumers prefer the certification. When a consumer selects the certification, the value is 0; otherwise, it is 1. The estimated value of −8.486 means that, ceteris paribus, the utility value, when there is no certification is lower by 8.486 than when there is certification. The results indicate that consumers prefer MSC-labeled NSP. The estimated MWTP of consumers for MSC-labeled NSP is NTD 84.86, meaning that, ceteris paribus, the MWTP of Taiwanese consumers for NSP products with the MSC label is up to NTD 84.86 than for those without the label.

Table 5.

Results of Random Parameter Logit Models.

In terms of the certification period, the estimated value of −0.020 indicates that consumers prefer a shorter certification period. Consumers’ benefit drops by 0.020 for every extra year of the certification period. Given the current certification period of 5–10 years, the utility value would drop by 0.1–0.2 for the shorter certification period. Although the value is statistically significant, it is only about 0.2% of the ASC value. The policy implications of the results are that while a longer certification period is undesirable to consumers, they are nevertheless more concerned about certification. Therefore, the certification period should be extended to reduce the annual average cost of certification, to motivate fisheries to acquire the certification. This measure is beneficial to both fisheries and consumers.

The estimated value of −0.002 for package size indicates that consumers prefer smaller packages. However, the package is a factor affecting the average cost. The smaller the packages, the higher the average cost. Although consumers prefer smaller packages, assuming the same average cost for both smaller and larger packages, the smaller ones bear the higher average cost of the MSC label. This would erode the profits earned by the fisheries and discourage them from providing the option of smaller packages. Therefore, larger packages could lower average production costs for fisheries and have minimal adverse effects on Taiwanese consumers. Therefore, it is advisable to sell the products in larger packages.

4. Discussion

As to the effects of price, economic theories suggest that the price elasticity of normal goods is negative, or that a higher price correlates to smaller quantities purchased by consumers. Nevertheless, the theories do not always hold; that is, some goods have positive price elasticity. Therefore, the relationship between price and purchasing quantity must be ascertained by empirical analysis. In this study, the estimated value for the price is positive (0.101) and significant, indicating that consumer utility increases with the upward movement of price, or that price elasticity is positive. According to economic theories, the positive price elasticity of goods can be explained by the Veblen effect [34] or the fact that sometimes prices are perceived as signals of product quality [35]. Both factors, which are discussed in detail below, may be present in Taiwan’s NSP market.

4.1. Veblen Effect

In global studies on shrimp markets, consumers often perceive shrimp as luxury goods in comparison to other seafood [36]. NSP distinguish themselves as wild and cold-water shrimp, unlike shrimp farmed in the tropics and commonly available in Taiwan. Such a distinction makes it possible to sell NSP at high unit prices in Taiwan with marketing concepts such as the Arctic, pure water area, and wild fishing. Moreover, common consumers perceive NSP as an ingredient for delicate cuisines, such as sashimi, sushi, and salad, and thus, they perceive it as different from other shrimps. Similar to luxury goods, the willingness to purchase them would increase with higher prices. Even when the higher price is due to the cost of acquiring the MSC label, consumers are more willing to purchase NSP because of the Veblen effect [37].

4.2. Prices as Signals of Product Quality

Without sufficient information, consumers assess product quality based on price [35]. The issue of incomplete information (Incomplete information (or asymmetric information) can cause “adverse selection” or “moral hazard”, which leads to a market failure [38]. However, ecolabeling schemes, which provide full information [39], could be a suitable market-based instrument to adjust asymmetric information effects between consumers and producers [40]. Furthermore, a high cost of labelling can improve overall welfare [41]. Please refer to the reference for economic models of asymmetric information) may originate from food quality or certification quality. In terms of food quality, Taiwanese consumers are unfamiliar with NSP in comparison with other shrimps. Therefore, they may rely on price to assess NSP quality when purchasing the product. The phenomenon is consistent with the results of experiments by Valenzi and Andrews [42]. Consumers believe that prices are positively correlated to food flavor/quality. In terms of certification quality, consumers may perceive price as a signal of label quality. Taiwanese consumers are very unfamiliar with the MSC label. Therefore, they may prefer products at higher prices and with certification, expecting that high prices relate to high certification quality. This is in line with the findings of Jaafar et al. [43] that when unfamiliar with new labels, consumers expect labels at higher prices to have higher quality.

5. Conclusions

This study aims to provide some insight into NS fisheries complying with the MSC standard by discussing Taiwanese consumers’ preference for MSC-labeled NSP. This study has three distinguishing features. The first is a national representative sample. The data for the study were obtained by nationwide “stratified multi-stage probability proportional to size sampling” of the population at the age of 18 and above in Taiwan. The second is providing practical information to the MSC in setting the certification period duration by examining consumers’ preference for the period. The third is expanding empirical case studies on the MSC certification of NSP. Moreover, this study also offers guidelines on market pricing and packaging.

This study finds that Taiwanese consumers prefer MSC-labeled NSP and the product has a positive price effect in the market. Consumers’ preference for MSC-labeled NSP implies that the label can increase market competitiveness in Taiwan and the profits of fisheries. Facing a price difference within NTD 84.86, consumers would choose products with the MSC label between two otherwise identical products. In addition, a positive price effect for the MSC-labeled products means that consumers are more willing to buy NSP products at a higher price [5,37], or the MSC label quality, represented by higher prices, would increase Taiwanese consumers’ willingness to purchase certified NSP.

Consumers’ preference for certification periods and package sizes is also valuable information for NSP fisheries in market competition. In terms of packages, consumers’ preference for smaller packages may increase the costs borne by fisheries. In terms of certification periods, consumers’ preference for shorter periods would also increase the costs borne by fisheries. However, the effects of such a preference are minimal compared with the effects of preference for MSC-labeled products. Therefore, the MSC may extend the certification period to lower average certification costs and provide more incentives to NS fisheries to acquire the MSC label. NS fisheries can also leverage the market attractiveness of the MSC label to offset disadvantages associated with larger packages, which can lower the average cost and reduce the adverse effects of higher average costs from the MSC label on product competitiveness.

The results of this study support the conclusions of Valenzi and Andrews [42] and Jaafar et al. [43]. When consumers are unfamiliar with products or labels, a high price is a viable marketing strategy. However, the advantage cannot sustain the promotion of products and labels. Ultimately, the key is the consumers’ evaluation of the labels. Therefore, on the one hand, the MSC can help fisheries sell products at high unit prices in emerging and less-developed markets. The profits generated can provide more incentives to fisheries to apply the MSC standard. On the other hand, the MSC should improve consumers’ evaluation of the MSC to maintain the market competitiveness of the MSC label. Based on the results, we believe the Taiwan NS market consumers are willing to continue to pay to support the NS fishermen to implement the MSC standard to reduce negative impacts of NS fishing activities, such as overfishing and the related impacts. The market will provide incentives to help restore populations of NS and the entire food chain. Cod, flatfish, skate, seals, and some endangered species, such as the leatherback sea turtle and the Atlantic wolffish, can benefit from restoration of the food chain. The MSC should maintain the credentials of the MSC certification process and give convincing information to the consumers.

This study is not free from limitations. First, a limitation of this study is the possibility of a moderator variable. Our study did not address effects of gender, age, income, and education on MWTP for the MSC label. Therefore, future research is recommended to examine the effect of these variables on the MSC label. Second, in our analysis, we specified a RPL model. However, a nested MNL (NMNL) model may be appropriate in analyzing respondents’ first decision as to whether or not choose the MSC label. Third, we did not test choice models allowing for a sequential decision-making process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I-J.C.; Data curation, I-J.C. and H.-C.J.Y.; Formal analysis, T.-M.L.; Funding acquisition, T.-M.L.; Investigation, T.-M.L., I-J.C. and H.-C.J.Y.; Methodology, T.-M.L.; Project administration, T.-M.L.; Resources, T.-M.L.; Software, T.-M.L.; Supervision, T.-M.L.; Validation, T.-M.L.; Writing—original draft, T.-M.L. and I-J.C.; Writing—review & editing, T.-M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, under Grant MOST 109-2410-H-110-084, and MOST 109-2420-H-110-003-MY2 programs.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to guidelines of MOST, Taiwan.

Informed Consent Statement

This was an anonymous study and the researcher cannot trace the data to an individual participant. In this case, informed consent statement were waived for this study, due to guidelines of MOST, Taiwan.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, which helped us to improve the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Carruthers, E.H.; Parlee, C.E.; Keenan, R.; Foley, P. Onshore benefits from fishing: Tracking value from the northern shrimp fishery to communities in Newfoundland and Labrador. Mar. Policy 2019, 103, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.; Glenn, R.; Whitmore, K.; McBane, C.; Idoine, J.; Spear, B. Assessment Report for Gulf of Maine Northern Shrimp—2018. Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission’s Northern Shrimp Technical Committee. Available online: http://www.asmfc.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2020).

- Hagen, N.T.; Mann, K. Functional response of the predators American lobster Homarus americanus (Milne-Edwards) and Atlantic wolffish Anarhichas lupus (L.) to increasing numbers of the green sea urchin Strongylocentrotus droebachiensis (Müller). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1992, 159, 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novaczek, E.; Devillers, R.; Edinger, E.; Mello, L. High-resolution seafloor mapping to describe coastal denning habitat of a Canadian species at risk: Atlantic wolffish (Anarhichas lupus). Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2017, 74, 2073–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thrane, M.; Ziegler, F.; Sonesson, U. Eco-labelling of wild-caught seafood products. J. Clean. Prod. 2009, 17, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasa Gopal, T.; Boopendranath, M. Seafood ecolabelling. Fish Technol. 2013, 50, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Giacomarra, M.; Crescimanno, M.; Vrontis, D.; Pastor, L.M.; Galati, A. The ability of fish ecolabels to promote a change in the sustainability awareness. Mar. Policy 2021, 123, 104–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellchambers, L.M.; Fisher, E.A.; Harry, A.V.; Travaille, K.L. Identifying and mitigating potential risks for Marine Stewardship Council assessment and certification. Fish. Res. 2016, 182, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakamatsu, M.; Wakamatsu, H. The certification of small-scale fisheries. Mar. Policy 2017, 77, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyert, W.; Sagarin, R.; Annala, J. The promise and pitfalls of Marine Stewardship Council certification: Maine lobster as a case study. Mar. Policy 2010, 34, 1103–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, T.; Ominami, J.; Tamura, N.; Yagi, N. Estimates of the potential demand of Japanese consumers for eco-labeled seafood products. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi 2010, 76, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronnmann, J.; Asche, F. Sustainable seafood from aquaculture and wild fisheries: Insights from a discrete choice experiment in Germany. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlucci, D.; Devitiis, B.D.; Nardone, G.; Santeramo, F.G. Certification labels versus convenience formats: What drives the market in aquaculture products? Mar. Resour. Econ. 2017, 32, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, J.; Wakamatsu, H.; Miyata, T.; Oozeki, Y. Has the consumers awareness of sustainable seafood been growing in Japan? Implications for promoting sustainable consumerism at the Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.; Nayga, R.M., Jr. Is Marine Stewardship Council’s ecolabel a rising tide for all? Consumers’ willingness to pay for origin-differentiated ecolabeled canned tuna. Mar. Policy 2018, 96, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M. Testing on-site sampling correction in discrete choice experiments. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roheim, C.A.; Asche, F.; Santos, J.I. The elusive price premium for ecolabelled products: Evidence from seafood in the UK market. J. Agric. Econ. 2011, 62, 655–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffry, S.; Glenn, H.; Ghulam, Y.; Willis, T.; Delanbanque, C. Are expectations being met? Consumer preferences and rewards for sustainably certified fisheries. Mar. Policy 2016, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, J.; Bartolino, V.; Waldo, S. Price premiums for providing eco-labelled seafood: Evidence from MSC-certified cod in Sweden. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 66, 690–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Nielsen, M.; Nielsen, R. Price premium of organic salmon in Danish retail sale. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 122, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ankamah-Yeboah, I.; Jacobsen, J.B.; Olsen, S.B.; Nielsen, M.; Nielsen, R. The impact of animal welfare and environmental information on the choice of organic fish: An empirical investigation of German trout consumers. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2019, 34, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, K.J. A new approach to consumer theory. J. Political Econ. 1966, 74, 132–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M.; Tien, C.-M. Assessing Tourists’ Preferences of Negative Externalities of Environmental Management Programs: A Case Study on Invasive Species in Shei-Pa National Park, Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.; Gerard, K.; Amaya-Amaya, M. Discrete choice experients in a nutshell. In Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care; Amaya-Amaya, M., Gerard, K., Ryan, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.; Gerard, K.; Amaya-Amaya, M. Using Discrete Choice Experiments to Value Health and Health Care; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jobe, J.B. Cognitive psychology and self-reports: Models and methods. Qual. Life Res. 2003, 12, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lew, D.K.; Layton, D.F.; Rowe, R.D. Valuing enhancements to endangered species protection under alternative baseline futures: The case of the Steller sea lion. Mar. Resour. Econ. 2010, 25, 133–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.-M. Using RPL Model to Probe Trade-Offs among Negative Externalities of Controlling Invasive Species. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, S.; Couper, M.P.; Lessler, J.T.; Martin, E.; Martin, J.; Rothgeb, J.M.; Singer, E. Methods for testing and evaluating survey questions. Public Opin. Q. 2004, 68, 109–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.-C. 2018 Taiwan Social Change Survey (Round 7, Year 4): Globalization and Culture (D00170_2). In Taiwan Social Change Survey; Center for Survey Research: Taipei, Taiwan; RCHSS, Academia Sinica: Taipei, Taiwan, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mcfadden, D. Econometric Models of Probabilistic Choice; The MIT Press: London, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyos, D. The state of the art of environmental valuation with discrete choice experiments. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1595–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Train, K.E. Recreation demand models with taste differences over people. Land Econ. 1998, 74, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, P.R.; Mcclure, J.E. Toward an economic theory of fashion. Econ. Inq. 1993, 31, 595–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinsky, A. Prices as signals of product quality. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1983, 50, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maradiah, A.R.; Lau, T.K. World overview of the shrimp market. J. Bur. Res. Consult. 1994, 1, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhart, Y.; Ayalon, O.; Puterman, H. The effect of an environmental claim on consumers’ perceptions about luxury and utilitarian products. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 53, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dari-Mattiacci, G.; Onderstal, S.; Parisi, F. Asymmetric solutions to asymmetric information problems. Int. Rev. Law Econ. 2021, 66, 105–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltzer, K. Standards vs. labels with imperfect competition and asymmetric information. Econ. Lett. 2012, 114, 61–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, K.; Hutchinson, W.G.; Longo, A. Willingness-to-Pay for Eco-Labelled Forest Products in Northern Ireland: An Experimental Auction Approach. J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 2020, 87, 101–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marette, S.; Crespi, J.M.; Schiavina, A. The role of common labelling in a context of asymmetric information. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 1999, 26, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenzi, E.R.; Andrews, I.R. Effect of price information on product quality ratings. J. Appl. Psychol. 1971, 55, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, S.N.; Lalp, P.E.; Naba, M.M. Consumers’ perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards private label food products in Malaysia. Asian J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).