Abstract

Planning and managing the declining fortunes of shrinking cities are essential in shaping urban policy in post-industrial urban societies, especially in Central and Eastern European states. Many studies emphasize city management and redevelopment as important policy constituencies for driving revitalization. However, there is still a lack of knowledge about policy-making and the underlying political and socio-economic disagreements that impact successful measures to reverse urbanization and regenerate post-industrial cities. This paper provides a case of urban policy-making for Bytom—a severely shrinking city in southern Poland. This article aims to clarify the mismatch between the city’s policy and the socio-economic situation Bytom after 2010. This discrepancy could have weakened effective policy to address shrinkage and revitalization. Statistical and cartographic methods (choropleth maps) helped analyze the socio-economic changes in Bytom and its shrinking. The issues related to the city’s policy were based primarily on free-form interviews and the analysis of municipal and regional documents concerning Bytom. The conducted research shows the need for concerted and coordinated policy direction that considers the real possibilities of implementing pro-development projects. Such expectations also result from the opinions of local communities. Finding a compromise between the idea of active support for projects implemented in a shrinking city and an appropriate urban policy is expected. Such an approach also requires further strengthening of social and economic participation in local and regional governance.

1. Introduction

The de-urbanization cities are essential elements of the discourse on the economic and social transformation in Central and Eastern Europe [1,2,3]. This issue is significant in those shrinking cities, where the demographic decline results from a profound and advanced transformation of the economic system. This phenomenon most often leads to depopulation and economic crisis in the vicinity of such a city [4,5,6]. It then has the character of absolute shrinkage (population decline in the city and its surroundings), which can be opposed to relative shrinkage (population decline in the city and increase in its surroundings) and caused by suburbanization [7]. These issues are considered in various contexts, and one of the most important is the problem of different paths of changes in shrinking cities [8,9,10,11]. Although the scientific achievements in this field are already significant, there are still some research gaps in learning about processes and phenomena accompanying urban shrinkage. Without a doubt, there is still no clear answer to some key questions. The first is more general and focuses on total reflection—what guidelines should create a shrinking city’s urban policy? This way, the question provides the background for further extending the question—whether urban shrinkage is sometimes difficult to solve because it is still not always necessary in the urban agenda. There is also a third case in which urban shrinkage is in the agenda-setting. However, the implementation of revitalizing the city is not entirely in line with the initial social expectations. Finally, one must also ask how long the transformation takes the city on the path of re-urbanization. Is the title decade enough for this?

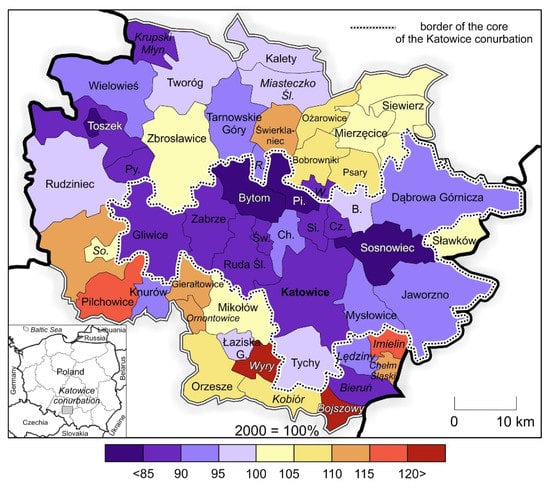

The article attempts to respond to the above research challenges, capturing the ten years of struggle with urban shrinkage in Bytom, located in the Katowice conurbation core (in southern Poland). Figure 1 illustrates the dynamics of depopulation in Bytom and the Katowice conurbation.

Figure 1.

Depopulation in the Katowice conurbation in 2000–2018. Source: By author on the base of data from [12].

The decade’s title time horizon referred to 2000/2010 when Bytom was of particular interest to both the scientific community [13] and politicians (local, regional, national, and even E.U.). The city’s interest was caused not only by the catastrophic situation of Bytom in the demographic, social, economic, and infrastructural dimensions. It was also essential to break the then taboo in local politics, the motto of which was “everything is under control”, “nothing unusual is happening”. The contrast of urban policy in Bytom with the widely used journalistic term “Polish Detroit” was then very significant. However, another ten years passed. It was a period of specific changes in the socio-economic and, above all, the political sphere. Bytom was and is a symbol of all possible problems of socio-economic transformation of cities in the entire Katowice conurbation, but also along with Wałbrzych and Łódź throughout Poland [14]. No other city in the Katowice conurbation has experienced such different problems, often with such intensity. Some other cities, such as Sosnowiec, managed to eliminate economic and social problems [15,16].

Urban policy towards the shrinking city Bytom is taboo and radically different from other European cities [13]. Although urban shrinkage has different dimensions in the agenda-setting in western Europe’s cities, it was noticeable that it was the so-called systemic (macro-) Agenda [17]. In this group of cities, Bytom was a kind of “outsider” in this respect. Simultaneously, the city’s dramatic conditions required particular interventions at the level of both policy and politics.

The research assumptions were referred to in the article to two discourses on urban shrinkage policy. The first of them indicates the need for active and expansive support for shrinking cities. In contrast, the second approach assumes flexible city planning, assuming that it will continue to depopulate in the coming years (right-sizing policy), which is essential when looking to answer the urban policy’s failures in shrinking cities as Bytom. The article attempts to explain this problem, also pointing to the vital role of governance. This city’s governance is specific because it covers a relatively narrow group of stakeholders and the city authorities’ prominent role [16].

Based on these assumptions, the article presents the data and methods used and- the review of research on the issues discussed. Then, the city’s general socio-economic situation is described, with particular emphasis on the deepening depopulation. The following chapters discuss the urban policy issue related to the problem of shrinking cities.

An essential element of the research was also to present the opinions of the residents. The interviews also allowed us to look at this issue from the perspective of the local community. It was discussed for the title decade, pointing to the essential determinants of specific events and phenomena. The final chapters are Discussion and Conclusions.

2. Data and Methods

The article’s data and methods relate directly to urban shrinkage and the question of urban policy. The article’s essential issue is the data on the demographic situation and other dimensions—economic, social, or spatial. Due to the article’s auto-polemic character, focusing more on urban policy issues, only demo-graphic issues are presented in more detail. This type of information is the most common in studies on shrinking cities. Demographic data come from the Local Data Bank of the Central Statistical Office (BDL GUS) [18] and the Bytom Town Hall data. The author monitors the development of Bytom also based on the published Reports on the state of the city of Bytom and the continuous analysis of media information (cf: portal: Bytomski. pl; weekly: “Życie Bytomskie”), which are an essential source of the so-called “soft” information and data as well. Moreover, data from the City Development Strategy of Bytom 2020+ [19] and Study of the Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development in the Bytom Commune [20] were used in the research.

The article uses statistical and cartographic methods (choropleth map) to illustrate the city’s demographic changes. The issues related to the city policy were based on free-form interviews, analysis of municipal and regional documents concerning Bytom, and media information. One hundred sixteen free-form interviews with adult residents of Bytom were conducted in the city center; opinions were collected in 2018–2019 as a pilot (preliminary) study based on a case study whose primary purpose was to collect qualitative data (Table 1). Both in the free-form interviews and conversations with the residents of Bytom, the most important three questions were:

Table 1.

Number of respondents by sex and age.

- - assessment of the city’s development in the last ten years,

- - the issue of the city’s future and

- - assessment of the correctness of the implemented urban policy about the fundamental problems.

3. Research Review

3.1. Overview of Urban Shrinkage

The question of shrinking cities has already quite a rich literature and at least several discourses. The first one relates to the scale of the phenomenon—both about the analysis of shrinking cities in individual countries and specific case studies.

This vital issue presented is in publications mainly in terms of overview and statistics [21,22,23,24]. They emphasize shrinking cities’ role in demographically balanced cities and recording an increase in the number of inhabitants [8]. Another topic in this discourse is the relationship between a shrinking city and its hinterland or surroundings [25,26]. This range of information is essential as it allows the phenomenon to be quantified. The relevant facts, in turn, are the starting point for the second meaningful discourse. In this case, the research focuses on trying to explain the essence of shrinking cities. These explanations aim at capturing the relationship between economic, social, demographic, and spatial factors. The result of these explanations is valuable attempts to model the phenomenon, often included in schemas or iconography [10,27,28]. First of all, these studies allow for a synthetic approach to the correlation between urban shrinkage and various factors that may have a local and regional dimension [21,29,30,31]. A vital research achievement in this matter is also paying attention to two types of the phenomenon. In the first case, cities’ shrinkage this as a synonym for population decline resulting from suburbanization. The second type (cf. incl. [32]) is more complex, and most often, economic or socio-economic factors shape its genesis (de-industrialization, functional changes, and unemployment). An essential current of research is the spatial and infrastructural effects (and costs) of shrinking cities. Research focusing on this issue points to derelict lands and vacancies as signs of city crisis. The city’s negative image resulting from numerous brownfields or deserted residential buildings is often a pretext to delve into the essence of the problem of such a city [33,34,35]. The problem of shrinking cities also appears in the discourse defined as urban policy in shrinking cities. The presented article applies to this discourse.

In this discourse, researchers try to answer such fundamental questions: What framework should urban policy have in shrinking cities? Who should constitute it? What is the state’s role? To what extent should local communities be essential stakeholders? [36,37]. However, the answers to these questions assume the desirability of leading shrinking cities out of the crisis. However, this most widespread position stands in opposition to reflection on the legitimacy of creating support policies for this type of city—especially when urban shrinkage is moving towards a significant reduction of demographic, economic, and infrastructural potential. In the literature on the subject, the terms’ place that does not matter’ [38] and “a functionally needless city” appear [7]. Both discourses are linked in turn by the issue of smart shrinkage [39,40]. However, this trend’s message is an attempt to find beneficial changes and smart paths to transform a shrinking city regardless of the scale of the problems. This trend is related to sustainable development in shrinking cities [41,42,43] and issues related to post-socialist cities’ specificity [6,44,45]. There is also a significant problem concerning management in a shrinking city in the literature on the subject. This problem is significant in the shrinking city of Bytom, where the scale of adverse effects of depopulation reaches a critical point (e.g., the collapse of the city budget, collapse of the administrative territory, repulsive economic investments, and spatial enclave).

From the perspective of the urban governance typologies, the most expected seems to be a proportional share of stakeholders representing the following agendas: central government, local government, sector of business, and local communities. There are clear departures from this mode in which, as in China, governmental agencies [46] can play an essential role in Germany’s regional (federal) governmental agencies [47] or many countries the sphere of business [48]. The different roles of individual stakeholders result from various factors (political system, local government traditions of the city’s economic system, size, and others) [48]. However, from the perspective of making decisions about developing a shrinking city, it seems more important to answer whether this may be the expected mode despite one of these stakeholders’ apparent advantages. In cities where the city’s crisis is immensely deepened, such a question is of particular importance. In considering urban policy regarding shrinking cities, there is an attempt to define whether implementing depopulation plans is related to governance or new public management, see [49,50]. This problem in Poland’s dimension is significant because, despite many reforms, it is still impossible to implement such ways of achieving new public management objectives that would meet the requirements of increasingly complex socio-economic relations in a globalizing world (see [51]). The blurring of the border between the managerial mode of governance and new public management results in Poland from the weakness of something defined by the economic attribute in creating urban policy. An economic attribute may be, for example, large private enterprises actively participating in urban policy or the number of funds allocated to pro-development activities. Another example may be the informal economic and political dependencies between local authorities and a large company or the public finance sector’s excessive politicization. Undoubtedly, a particular type of such phenomenon is grant coalitions centered around E.U. and nationally funded projects.

Due to the multiplicity and diversity of problems, Bytom became the research subject in the first decade of the 2000s. Importantly, it was research conducted in international teams [13,52] played a unique role in explaining the shrinking process of Bytom. Regardless of scientific research based on Bytom [15], it is also necessary to mention this phenomenon’s spatial and historical aspects. This information is the subject of two publications about Bytom. The first publication pointed to changes in built-up areas in Bytom as a vital attribute of the shrinking process of cities [53]. The second publication focuses on, among others, explaining the phenomena that perpetuate the later problems of Bytom (mining monofunctional, demolition, and devastation of the intraurban built-up area, and social exclusion) [54].

The research concerned the complete diagnosis of the causes and effects of shrinking cities and, particularly, the possibility of solving problems based on the most favorable urban policy. In this matter, attention was paid in particular to the role of governance, pointing to the imperfect relationship between individual stakeholders and the limitations resulting from the mode of governance existing in the city [55,56]. The diagnosis of the then problems of Bytom allowed for the introduction of essential postulates to the city policy in the following years [19,57,58].

3.2. Urban Shrinkage Policy as a Response to Real Challenges (Review)

Cities that lost their current economic base experienced a crisis [6,59]. The challenges related to this problem appeared mainly in mining and industrial cities, some too specialized in single services (railway junctions, and some secondary spas), and some cities where local agriculture was the basis for their development [60,61]. As mentioned above, a wave of local economic or functional problems overlapped with the second demographic transition factors. Their most significant effect was a sharp decrease in the number of births and an increase in older people in the population’s age structure.

The most dramatic socio-economic changes took place in cities where all the adverse effects of the transformation accumulated. Difficulties in cities’ changes can also cause such objective factors as competition between cities for new development impulses, negative image of the city, a growing number of similar cities that required support from the urban policy [62,63].

The development policy of shrinking cities does not always correspond to real challenges. In the literature, we read that it results from a delayed response to existing problems, inadequate tools, methods of solving, or flexible urban policy [5,13]. The presentation of central authorities’ role in solving the problems of shrinking cities is also very diverse. In the USA and some Western European countries (e.g., Great Britain), the liberal model dominates. In this model, local and regional stakeholders play a vital role, not central authorities [4,11,64,65]. However, the situation was different in the first phase of urban shrinkage in East Germany. The central policy was of no less importance than the federal states’ regional policy and city policy [47]. Nowadays, we see the state’s essential role in the development policy of shrinking cities in China [66,67].

In post-socialist countries, urban policy towards shrinking cities has evolved over the past 20 years [6]. The first stage was the policy of “abandonment”. It was related to previously socialist countries’ socio-economic transformation. Urban shrinkage was one of the costs of this transformation, especially for post-industrial cities. The large scale of de-industrialization and limited budget funds made it challenging to implement pro-development projects on a larger scale. Only some cities reindustrialized or changed their functions to specialized services to defend themselves against urban shrinkage and functional crisis. However, the free market and the economy’s globalization played a more significant role than the central authorities’ pro-development activities. Undoubtedly, a new development perspective and changes in urban policy in shrinking cities occurred with Central and Eastern European countries’ entry into the E.U.’s structures. Organizational and financial support was necessary in this case. The private sector also strengthened urban renewal processes. However, despite the new stage and the opportunities it created for the cities in this part of Europe, not everything went well. The example of Bytom in Poland can be almost a model in this matter.

4. The Determinants of Urban Shrinkage in the City of Bytom

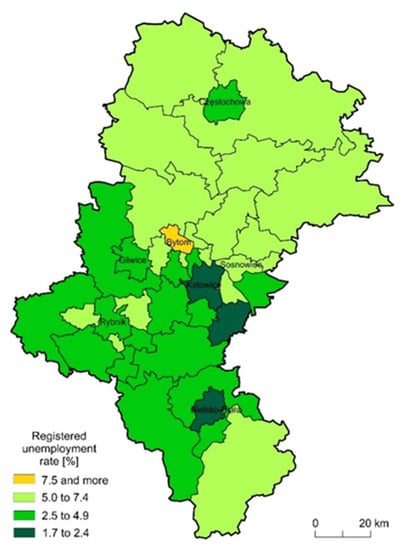

Until the end of the 20th century, Bytom was one of the largest hard coal mining centers in Europe. In addition, six mines employing over 30,000 miners, two ironworks, and several other companies, including the manufacturer of men’s clothing “Bytom”, well-known in Central Europe. The depletion of hard coal resources coincided with the rapid restructuring of the industry during this period. Bytom operated only one medium mine (“Bobrek”), one smaller mine, and a restructured steel mill in 2019. The liquidation of mining and industrial functions caused a dramatic regress of the city’s economic condition and increased social problems. Since the end of the 20th century, the city has continuously recorded unemployment in large Polish cities and record-breaking in counties located in the Silesian province. The registered unemployment rate in Bytom in 2018 was 9.7% (Figure 2). In the city center and peripheral districts of Bytom, there are many residential vacancies and brownfields, deepening the city’s negative image. All these phenomena were among the reasons for the disconnection from the city of Radzionków in 1998 [68].

Figure 2.

The registered unemployment rate in counties of the Silesian Voivodeship in 2018. Source: By author on the base of data from [12].

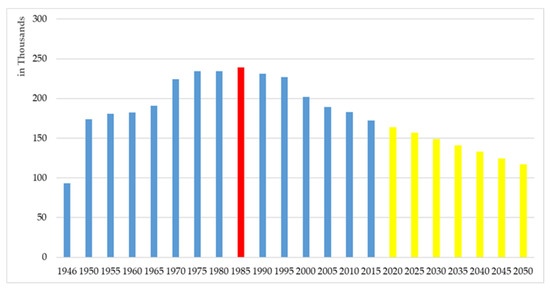

The most significant effect of Bytom’s problems is depopulation. In the years 1985–2015, the city lost 67,000 residents. While 30 years ago, 239,000 people lived here, in 2015, the number of inhabitants was 172,000. In the 2000s, the average annual decrease in population was approximately 2000 people per year. The demographic forecast for Bytom indicates that in 2050 only about 117,000 inhabitants will live in this city (Figure 3). Bytom depopulation results from a more significant number of deaths than births and the advantage of emigration over immigration.

Figure 3.

Population in Bytom in 1946–2015 and the demographic forecast for 2020–2050. Source: By author on the base of data from [12,69].

Another unfavorable Bytom’s development is the city’s inferior economic activation in acquiring significant industrial investments. Despite good transport accessibility, a potentially large sales market, location in a 2-million-strong Katowice conurbation, and the launch of a special economic zone, the city’s reindustrialization is relatively weak. Due to this problematic investment situation, 12,997 people work in neighboring cities (in 2016). In turn, 7186 employees come to work from outside the commune, so the balance of arrivals and departures to work is −5811 [70].

This complicated situation in Bytom is the effect of the problems related to the monofunctional of the city, spatial problems, and for 30 years also economic and social problems, which have been growing for over two centuries. The concentration and intensity of so many different problems caused around 2010 Bytom was the center of attention in Poland’s national urban policy and an E.U. forum [71]. Notably, the problems of Bytom after the political transformation of 1989 did not find a special place in state or regional policy. Practically at the end of 2010, the city was plunging into a multi-faceted crisis. At that time, the acceptance and consent acceptance policy to shrinkage dominated (Table 2). To a large extent, this was because depopulation was an incomprehensible element of the anti-unemployment policy during this period. The latter problem constituted the fundamental element of defining urban policies focused on direct or indirect mitigation of this phenomenon [72].

Table 2.

Policy background of the urban shrinkage in Bytom.

Interestingly, depopulation as a remedy was an unacknowledged method of reducing the unemployment rate and was one of the essential elements of policy taboo, not only in Bytom but also in many cities in the region. Depopulation, as a policy, taboo had another economic dimension. There was no talk about it to avoid deterring potential investors.

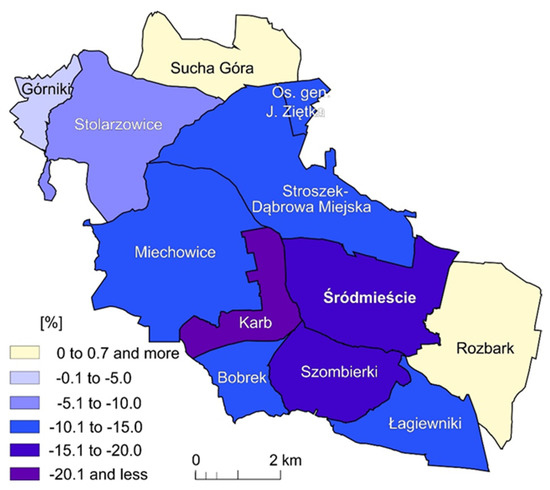

5. Dimensions of Urban Policy in Bytom in the Last Decade

The dramatic situation of the city at the turn of the years 2000/2010 caused a shift in understanding the city’s threats. The city authorities were then aware of the accumulated problems. However, there was a perception that they could not prevent the situation. The decline in the number of people takes place in the vast majority of districts of the city of Bytom (Figure 4), indicating that it is an unstoppable process. The situation is similar in the neighboring cities of the Katowice conurbations. The activities consisted of monitoring the situation and, if necessary, taking small actions that could somehow slow down the demographic decline. The remedy for the city’s development was to be the development of high culture. However, the scale of the problems at that time was more important. At that time, out of 170,000 inhabitants, more than 10,000 adult residents benefited from social assistance. The registered unemployment rate fluctuated around 20–25%.

Figure 4.

Dynamics of the population in Bytom by quarters in 2008–2018. Source: By author.

Additionally, only in Śródmieście were there about 2000 vacant buildings, most of them in old tenement houses from the 19th and early 20th century [73]. The number of post-industrial brownfields also increased every year. During this period, city management dysfunctions were also visible, which can be called the Weber model. Autonomous organizational goals characterize this model, the transfer of power from the political system to the city administration, acceptance of minimalism in officials’ activities, and, most importantly, investment failures [51,74]. The breakthrough in the city authorities’ thinking about the challenges facing the city, and especially the politics and tools to deal with these challenges, comprised three events:

- - Growing social resistance to the helplessness of the city authorities regarding the often collapsing monumental tenements and the destruction of housing estates in the Karb district;

- - The policy of the local mine, which intended to extract coal from under the city center, would probably cause permanent devastation of this historic district; and

- - Activities of participants of the international Shrink Smart project involved supporting the city authorities in saving the city regardless of their scientific purpose.

As a result of these events and actions, the policy of the city authorities changed radically. A special economic zone was created in the city to attract new investors. Since then, public management has aimed to slow down city shrinkage. This change was also clearly visible about three types of urban policy instruments:

- - Development planning instruments;

- - Instruments for organizing the development process of which the element is the creation of appropriate institutions;

- - Policy implementation instruments: legal, financial, control, and evaluation, including the creation of databases as monitoring tools [75].

Important documents of the urban policy of Bytom include the Bytom City Development Strategy 2020+ [19] and the Commune Revitalization Program. Bytom 2020+ [76] and the Bytom City Revitalization Program for 2007–2020 [77]. The second group of instruments primarily creates a special program: Strategic Intervention Area (OSI), the creation of Special Revitalization Zones, and the implementation of the Katowice Special Economic Zone in Bytom. The third group of tools includes increasing monitoring in the City Hall units or a pilot project: Bytom OdNowa [78].

As a result of the events mentioned above and activities, the Bytom authorities’ policy has changed radically. The realization of brownfields’ role in the city has become a significant fact, especially compared to another shrinking city’s remarkable success in this region of Sosnowiec. In Sosnowiec, new investments were made already in 2012 in postmining brownfields. The Shrink Smart project [71] and decision-makers actions in the E.U. made it possible to obtain funds to revitalize the city. Bytom obtained a special fund for revitalization for EUR 100 million (the so-called Strategic Intervention Area Fund) [79,80].

The city authorities also resigned from the previous priority plan to develop high culture as a city development tool and introduced other pro-development solutions. The problem of shrinking Bytom was noticed and became one of the elements of urban policy in Bytom. In 2014, there appeared for the first time the city’s Strategy [19]. This document’s fundamental assumption is that the city’s shrinkage is also the “engine of development” of the city. All strategic and operational assumptions must take into account this fact. The issue of urban shrinkage then became a fundamental element of the Urban Agenda. Although the assumptions were very ambitious in this matter—to adopt solutions characterizing the institutional model according to Cobb and Elder [17]—it finally ended with the systematic model (set of stages and actions for right-sizing) [39]. The problem of depopulation of cities appears in the City Revitalization Program [77]. The pool of funds for Bytom, an area of strategic intervention under revitalization activities, has been provided for the Regional Operational Program of the Śląskie Voivodeship [81]. An important document was the preparation of recommendations for the development strategy of Bytom [82], in which the fundamental role of urban shrinkage in shaping the face of the city—social, spatial, economic, and even political—was highlighted. Unlike other Katowice region cities, the Special Economic Zone authorities or numerous companies’ leaders represent new industries. Although the newly appointed president continued the actions initiated by his predecessor (the first company in the economic zone, the distribution of E.U. funds for revitalization, development of the Commune Revitalization Program. Bytom 2020 + [76]), he did not manage to slow down the city’s recourse significantly. Under his rule, Bytom became one of the leading centers for storing (mostly illegally) harmful waste transported to the city from Poland and other E.U. countries. The media coverage of this topic and the harmfulness of this type of activity per se were undoubtedly among the counterpoints to implementing the city’s investment policy. Bytom, known for mining damage, has also become known for illegal toxic landfills. The environmental threat factor indirectly contributed to the end of the next president’s rule.

The previous president lost in a political struggle against the dangers of mining. On the other hand, in 2018, one reason for not appointing the incumbent president for the next term was quite a conservative policy towards companies contaminating some areas in the city.

6. Assessment of Changes and Urban Policy in the Opinion of Residents of Bytom

An essential element of the research was free-form interviews with Bytom’s inhabitants, making it possible to get to know opinions on evaluating phenomena and changes in the city over the last ten years (Table 3). As mentioned, one hundred sixteen free-form interviews were conducted, sixty-four of which were with women and fifty-two with men.

Table 3.

Respondents’ answers regarding the assessment of the city’s development in the last ten years (by sex and age).

The most critical were people aged 35–54, both women (response rate 72.4%) and men (response rate 76.9%). Although the percentage of critical statements was lower in other groups of the population, it was still high.

Table 4 presents the answers to the next question regarding the assessment of the city’s future. Despite the noticeable predominance of negative opinions about the city’s future, the percentage of such indications was lower than in assessing its development in the last ten years.

Table 4.

Respondents’ answers regarding the assessment of the city’s future (by sex and age).

A characteristic element of the evaluation of urban policy about urban shrinkage were statements emphasizing: no visible actions are improving the economic and social conditions of the inhabitants (87.7%), inability to solve the most fundamental problems (75.0%), or inappropriate financial decisions (72.3%). Table 5 presents the respondents’ detailed answers concerning the correctness of the implemented urban policy regarding the fundamental problems.

Table 5.

Respondents’ answers regarding assessing the correctness of the implemented urban policy about the fundamental problems (by sex and age).

However, the obtained answers give some picture of the city’s social perception and its authorities. The status quo manifested in these opinions also corresponds to the facts and phenomena presented in Table 2. Notably, Bytom’s urban policy’s relatively critical assessment is different from assessing its inhabitants’ lives. In the report Social diagnosis. The conditions and quality of life of Poles [83], it was indicated that Bytom is the big Polish city whose inhabitants rate their place of residence best. These slightly surprising statements of the respondents should probably be explained by their complete disbelief in the possibility of re-urbanizing the city by local authorities and focusing on their narrow horizon of life. This thesis may be confirmed, for example, by the significant development of NGOs focused on the good of the city. When analyzing the data presented in the tables, one should also consider the accumulation of adverse events in Bytom in recent years, with the simultaneous lack of significant or breakthrough investments or achievements. The fund mentioned, EUR 100 million, is funds that Bytom has to use as a city significantly affected by social and infrastructure problems. Unfortunately, these funds have not been adequately spent so far. Therefore, there are no tangible effects from an economic or social point of view.

The negative image of Bytom’s changes can be explained by the fact that the respondents were residents of the downtown district of Bytom, where there are many social and economic problems.

7. Discussion

In the second half of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, Bytom developed based on hard coal mining and the related consequences. The most important is locked-in on self-reinforcing negative path dependence [84]. In the political and image dimension, Bytom emerged in the last decade of the twentieth century as a vital economic center with a historic building quarter that brought it splendor and metropolitan character. Economic and social changes quickly overturned these views. In the 21st century, the city was already one of the three most declining large Polish cities (the others are Łódź and Wałbrzych). The shock and trauma of transformation in the social dimension manifested itself mainly in the deepening depopulation and centrifugal tendencies leading to the urban territory’s tearing. Such phenomena also occurred in other European cities of a similar size, such as Ostrava or Halle, and larger ones such as Leipzig or Liverpool [71,85,86].

As the authors of these publications point out, the urban policy did not keep pace with these changes in many cases. While in Germany or Great Britain, attention was paid to the insufficient pace of implemented changes, in eastern European cities, including Bytom, there were such elements as “flexible policy”, “grand coalition”, “denial”, “taboo”, and “helplessness”. In the last decade, the last three have become especially visible in Bytom. Their role was also directly or indirectly visible in interviews with residents. For example, at that time, the then city president critically refers to the author of the Ruins of Bytom website [87], presenting the city’s devastated buildings for slandering Bytom’s image, deterring potential investors and tourists [88]. In the cities of eastern Germany, urban shrinkage was at the same time an evident phenomenon [89]. Bytom in urban policy was to have the image of a city with traditions, vibrant, and cultural. It was supposed to have it, but it did not have it anymore at the citizens and NGOs level. This image, preserved from previous decades, was also a cover against the local government’s difficult challenges. Urban shrinkage was then outside the political agenda-setting at the level of the central and regional government. The actions of the city authorities in each such case were somewhat intuitive. After nearly ten years, there has been a significant change in this respect. The city’s shrinking is an open issue in the urban debate, strategic documents, and the local community.

Unfortunately, there are no significant tangible effects got urban shrinkage into the agenda-setting. It is difficult to answer the question of why this is so. Indeed, the initial ambitions to transform it into an institutional program were right, needed, and possible to achieve by including the city in the network of the so-called Special Intervention Areas (OSI) and privileges associated with unique revitalization fund goals. Although these mechanisms still work, their real effect is weak, and many findings are “blurred” at subsequent levels of decisions and what to change in Bytom. Undoubtedly, there is backwardness compared to the euphoria and hopes that accompanied these changes in early 2010. Today, the urban shrinkage agenda is changing in Bytom into a systematic model from the institutional model.

Inappropriate effects of implementing the policy of preventing urban shrinkage in Bytom probably result from several reasons. Their context can be well captured by comparing the city policy of Bytom with the politicians of other European cities. The first issue is that there is a delay of several years in reacting to the phenomena. While in East Germany, this policy was implemented parallel with the problem in Bytom and many other cities with a long delay [47,52,72]. Thus, the city authorities made their decisions when unfavorable phenomena advanced. As the example of Bytom shows, it could cause feedback and synergy of negative phenomena. A simple transfer of patterns and tools of urban policy might not be enough in this situation. As shown by the example of Liverpool, the scale of the intervention was radically different. In 2000–2012, local governance focused on urban shrinkage covering over 20 stakeholders in Bytom only 5–6 [71]. There were also different options for intervention. While in many German cities, plans for revitalization and reconstruction of cities were accompanied by financial resources for implementing these projects, in Bytom and other cities of the Katowice conurbation, financial instability and point action were visible [16,90,91]. Both attributes had a destabilizing effect even on the possibility of revitalizing one district. It was also essential to favor the governing model over governance in Poland. In such a situation, any municipal authorities’ mistake, which implemented the urban policy quite authoritatively, was beyond other stakeholders’ control [92]. The mature model of local/regional governance did not start to take shape in Bytom until 2015–2020.

A favorable factor for this retardation is undoubtedly the stakeholder group’s expansion directly or indirectly in the city’s situation. It is an essential attribute of governance regardless of its mode [93]. Among the stakeholders actively participating in the transformation process are the Polish government, voivodship authorities, and the local Revitalization Committee. There is also the institution “Bytom OdNowa’, signed by the Municipal Office. The governmental research institute Institute of Urban and Regional Development (IRMiR) also joined the research on Bytom. Despite so much support for the idea of city transformation, the city’s situation is still tricky. It seems that the expected organizational and substantive support is not accompanied by resilience in terms of the inflow of funds and strengthening the city’s economic potential. The said EUR 100 million funds were a potent stimulant injection supposed to trigger changes in the city’s face. However, according to the current city authorities and some residents, these funds have been unnecessarily dispersed, which does not guarantee the “snowball effect” that will drive the city’s development. Bytom has also become a hostage to the revitalization provisions’ rigidity and talking about the proportions between spending money on soft projects and challenging projects. As a result, there is not enough money to implement the latter, and a surplus exists for the former.

8. Conclusions

The process of urban shrinkage in Bytom developed in two stages. In the first stage (1989–circa 2010), this phenomenon, although noticeable by local authorities, was not subject to unusual urban policy reactions. In the second stage (after 2010), urban shrinkage entered the agenda-setting, but the real effects of implementing depopulation policies and other problems are weak. Paradoxically, the scale of depopulation in both of these stages was similar. So, was the urban shrinkage problem not relevant to local authorities? After 2010, the idea of redeveloping the city gained importance, which proves the changes that have taken place in Bytom in the last decade. However, this did not affect the practical policy of redevelopment of the city. In the process of revitalizing a shrinking city, especially as rapidly as Bytom, the distinction between the idea and the policy of redevelopment, unfortunately, results in stagnation and further depopulation. What can be seen, analyzing, on the one hand, local politics and the other socio-economic and spatial phenomena after 2010, is that:

- (a)

- the activity of local authorities was aspirational rather than actively involved and, what could result from it, practical

- (b)

- relationships with key stakeholders were specific.

The poorly visible and ineffective relations of city authorities with large companies, which could break the negative path of dependence in Bytom, were replaced by relations based on a grant coalition resulting from the external E.U. funds. Unfortunately, this policy model was ineffective and, as indicated, highly unsuitable for such a shrinking city as Bytom. These facts are also confirmed by the opinions of the city residents presented in the article.

Considering the discourse on urban policy and public management towards shrinking cities, emphasizing the need for active strengthening of such cities on the one hand, and the right-sizing concept, on the other hand, it can be stated that both of these ideas existed in Bytom. It testifies means that the idea of active empowerment dominates in urban policy, strategies, or master plan, while real changes in the city have a right-sizing dimension.

This discrepancy is due to the ineffective support rules for shrinking cities at the initial support stage and subsequent coordination of redevelopment activities.

The Bytom case study emphasizes that the concept of comprehensive support for shrinking cities is realistic only when it is coordinated with an adequately effective urban policy and supported with considerable financial resources for the implementation of the adopted plans and strategies. If this does not happen, the changes are based only on selected projects (not always the most important ones). In the context of the discussion on the urban governance role, it seems reasonable to pay attention to the importance of its stakeholders’ opinions. Each of their weaknesses can suppress even the most worthwhile project of changing a shrinking city. This conclusion was important a decade ago, and, as current research shows, it was also relevant in 2020.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Sailer-Fliege, U. Characteristics of post-socialist urban transformation in East Central Europe. GeoJournal 1999, 49, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Maas, A.; Kabisch, S.; Steinführer, A. From long-term decline to new diversity: Sociodemographic change in Polish and Czech inner cities. J. Urban Regen. Renew. 2009, 3, 31–45. Available online: https://www.ufz.de/index.php?en=20939&ufzPublicationIdentifier=222 (accessed on 24 July 2020).

- Haase, A.; Rink, D.; Grossmann, K. Shrinking Cities in Post-Socialist Europe: What Can We Learn from Their Analysis for Theory Building Today? Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2016, 98, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiechmann, T.; Pallagst, K. Urban shrinkage in Germany and the USA: A Comparison of Transformation Patternsand Local Strategies. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Weyman, T.; Fol, S.; Audirac, I.; Cunningham-Sabot, E.; Wiechmann, T.; Yahagi, H. Shrinking cities in Australia, Japan, Europe and the USA: From a global process to local policy responses. Prog. Plan. 2016, 105, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stryjakiewicz, T. (Ed.) Kurczenie się Miast w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej [Urban. Shrinkage in Towns of the Central and East. Europe]; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I. Systematyka Procesu Depopulacji Miast na Obszarze Polski od XIX do XXI Wieku [Systematics of the Depopulation Process. of Cities in Poland from the 19th to the 21st Century]; Uniwersytet Śląski: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Mykhnenko, V.; Turok, I. East European Cities—Patterns of Growth and Decline, 1960–2005. Int. Plan. Stud. 2008, 13, 311–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckien, D.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. Why Do Cities Shrink? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 1375–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bănică, A.; Istrate, M.; Muntele, I. Challenges for the Resilience Capacity of Romanian Shrinking Cities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Wiechmann, T. Urban growth and decline: Europe’s shrinking cities in a comparative perspective 1990–2010. Eur. Urban. Reg. Stud. 2017, 25, 122–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Województwo Śląskie. Podregiony, Powiaty, Gminy [Śląskie Voivodship. Subregions, Powiats, Gminas]; Urząd Statystyczny w Katowicach [Statistical Office in Katowice]: Katowice, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bernt, M.; Haase, A.; Großmann, K.; Cocks, M.; Couch, C.; Cortese, C.; Krzysztofik, R. How does(n’t) Urban Shrinkage get onto the Agenda? Experiences from Leipzig, Liverpool, Genoa and Bytom. Int. J. Urban. Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1749–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroszewska, E.; Stryjakiewicz, T. Kurczenie się miast w Polsce [Shrinking cities in Poland]. In Kurczenie się Miast w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej [Shrinking Cities in Central and Eastern Europe]; Stryjakiewicz, T., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2014; pp. 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I. Paths of Shrinkage in the Katowice Conurbation. Case Studies of Bytom and Sosnowiec Cities; WNoZ Uniwersytet Śląski: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I. An Introduction to Governance of Urban Shrinkage. A Case of Two Polish Cities: Bytom and Sosnowiec; WNoZ Uniwersytet Śląski: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cobb, R.W.; Elder, C.D. Participation in American Politics: The Dynamics of Agenda Building; Allyn and Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Danych Lokalnych [Local Data Bank]. Główny Urząd Statystyczny w Polsce [Statistics Poland]. Available online: https://bdl.stat.gov.pl/BDL/start (accessed on 29 July 2020).

- Strategia Rozwoju Miasta Bytom 2020+ [City Development Strategy of Bytom 2020+]. Available online: https://www.bytom.pl/download/Strategia-Bytom-2020,44.pdf/view (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Studium Uwarunkowań i Kierunków Zagospodarowania Przestrzennego Gminy Bytom [Study of the Conditions and Directions of Spatial Development in the Bytom Commune], 2011. Available online: https://i-biip.um.bytom.pl/wydzial-architektury-studium-uikzp-gminy-bytom.html (accessed on 10 September 2020).

- Wolff, M.; Fol, S.; Roth, H.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking cities: Measuring the phenomenon in France. Cybergeo Eur. J. Geogr. 2013, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, D.; Barreira, A.P.; Guimarães, M.H.; Panagopoulos, T. Historical trajectories of currently shrinking Portuguese cities: A typology of urban shrinkage. Cities 2015, 52, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döringer, S.; Uchiyama, Y.; Penker, M.; Kohsaka, R. A meta-analysis of shrinking cities in Europe and Japan. Towards an integrative research agenda. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1693–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audirac, I. Shrinking cities: An unfit term for American urban policy? Cities 2018, 75, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heider, B. What drives urban population growth and shrinkage in postsocialist East Germany? Growth Chang. 2019, 50, 1460–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagopoulos, T.; Barreira, A.P. Shrinkage Perceptions and Smart Growth Strategies for the Municipalities of Portugal. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D.; Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K. Addressing Urban Shrinkage Across Europe—Challenges and Prospects, Shrink Smart Research Brief No. 1. 2010. Available online: https://www.ufz.de/export/data/400/39030_D9_Research_Brief_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Haase, A.; Rink, D.; Grossmann, K.; Bernt, M.; Mykhnenko, V. Conceptualizing Urban Shrinkage. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2014, 46, 1519–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubarevičienė, R.; van Ham, M.; Burneika, D. Shrinking Regions in a Shrinking Country: The Geography of Population Decline in Lithuania 2001–2011. Urban. Stud. Res. 2016, 2016, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Gao, S. (Eds.) Shrinking Cities in China. The Other Facet of Urbanization; Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Batunova, E.; Gunko, M. Urban shrinkage: An unspoken challenge of spatial planning in Russian small and medium-sized cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1580–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K. Shrinking cities in the United States of America: Three cases, three planning stories. In The Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context; Wu, T., Rich, J., Eds.; Monograph 2009-01; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schetke, S.; Haase, D. Multi-criteria assessment of socio-environmental aspects in shrinking cities. Experiences from eastern Germany. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2008, 28, 483–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Spórna, T.; Dragan, W.; Szymonowicz, T. Why and how central Europe’s largest logistics complex developed on a brownfield site. Acta Geogr. Slov. 2020, 60–62, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathey, J.; Rink, D. Greening Brownfields in Urban Redevelopment. In Built Environments. Encyclopedia of Sustainability Science and Technology Series; Loftness, V., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallagst, K.; Wiechmann, T.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. (Eds.) Shrinking Cities. International Perspectives and Policy Implications; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechmann, T.; Bontje, M. Responding to Tough Times: Policy and Planning Strategies in Shrinking Cities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.B.; Németh, J. The bounds of smart decline: A foundational theory for planning shrinking cities. Hous. Policy Debate 2011, 21, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, J.; Russo, J. Shrinking ‘Smart’?: Urban Redevelopment and Shrinkage in Youngstown, Ohio. Urban. Geogr. 2013, 34, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, D.L.; Shuster, W.D.; Mayer, A.L.; Garmestani, A.S. Sustainability for Shrinking Cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toura, V. Shrinking Cities and Sustainability De-Industrialization and Urban Shrinkage. Achieving Urban Sustainability in Former Industrial Cities in France: The Case Studies of Nantes and Saint-Ouen; AESOP: Venice, Italy, 2019; Available online: https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02190090/document (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Slach, O.; Bosák, V.; Krtička, L.; Nováček, A.; Rumpel, P. Urban Shrinkage and Sustainability: Assessing the Nexus between Population Density, Urban Structures and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegedus, J. The future of re-invented/post-socialist cities in Europe: A reflection on the State of European Cities Report (2007). Urban Res. Pract. 2009, 1, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinescu, I.P. Shrinking Cities in Romania: Former Mining Cities in Valea Jiului. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Tochen, R.M. Shifts in governance modes in urban redevelopment: A case study of Beijing’s Jiuxianqiao Area. Cities 2016, 53, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzimski, A. Programy Miejskie. Polityczny Wymiar Kształtowania Przestrzeni Zurbanizowanej w Świetle Doświadczeń Niemieckich [Programs for Cities. The Political Dimension of Shaping Urbanized Space in the Light of German Experiences]; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- DiGaetano, A.; Strom, E. Comparative Urban Governance: An Integrated Approach. Urban. Aff. Rev. 2003, 38, 356–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, L.E., Jr. Public Management: A Concise History of the Field. In The Oxford Handbook of Public Management; Ferlie, E., Lynn, L.E., Jr., Pollitt, C., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 27–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bevir, M. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Governance; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Anders-Morawska, J.; Rudolf, W. Orientacja Rynkowa we Współrządzeniu Miastem [Market Orientation in City Governance]; Akademia Samorządowa, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego: Łódź, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rink, D.; Couch, C.; Haase, A.; Krzysztofik, R.; Nadolu, B.; Rumpel, P. The governance of urban shrinkage in cities of post-socialist Europe: Policies, strategies and actors. Urban Res. Pract. 2014, 7, 258–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, J.A.; Nadolski, P. Atlas Geograficzny Bytomia [Geographical Atlas of City of Bytom]; Rococo—J. Krawczyk: Bytom, Poland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Drabina, J. Historia Bytomia od Średniowiecza do Współczesności 1123–2010 [The History of Bytom from the Middle Ages to the Present Day 1123-2010]; Towarzystwo Miłośników Bytomia: Bytom, Poland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I. Governance of urban shrinkage: A tale of two Polish cities, Bytom and Sosnowiec. In Contemporary Issues in Polish Geography; Churski, P., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2012; pp. 201–224. [Google Scholar]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; Spórna, T. Problemy zarządzania miastem kurczącym się na przykładzie Bytomia [Problems of governance shrinking city for the example of Bytom]. In Społeczna Odpowiedzialność w Procesach Zarządzania Funkcjonalnymi Obszarami Miejskimi [Social Responsibility in the Processes of Governance Functional Urban Areas]; Markowski, T., Stawasz, D., Eds.; Biuletyn KPZK PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 162–175. [Google Scholar]

- BYTOM 2020+ Uwarunkowania Społeczno-Gospodarcze Rozwoju Bytomia Jako Obszaru Strategicznej Interwencji, Wymagającego Kompleksowej Rewitalizacji [BYTOM 2020+ Social and Economic Conditions for the Development of Bytom as an Area of Strategic Intervention, Requiring Comprehensive Revitalization]; Urząd Miejski w Bytomiu: Bytom, Poland, 2013.

- Drobniak, A.; Goczoł, L.; Kolka, M.; Skowroński, M. The Urban Economic Resilience in Post-Industrial City—The Case of Katowice and Bytom. J. Econ. Manag. Univ. Econ. Katow. 2012, 10, 87–104. Available online: https://www.ue.katowice.pl/fileadmin/_migrated/content_uploads/7_Drobniak_Goczol_Kolka_Skowronski_The_Urban_Economic_Resilience.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2020).

- Martinez-Fernandez, C.; Audirac, I.; Fol, S.; Cunningham-Sabot, E. Shrinking Cities: Urban Challenges of Globalization. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, S.; Reid, N. Dealing with Decline in Old Industrial Cities in Europe and the United States: Problems and Policies. Built Environ. 2014, 40, 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P. Population Shrinkage in Resource-dependent Cities in China: Processes, Patterns and Drivers. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rink, D.; Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Couch, C.; Cocks, M.; Rumpel, P.; Tichá, I.; Slach, O.; Krzysztofik, R.; Runge, J.; et al. Specification of Working Model, Work Package 1; Helm-holtz Centre for Environmental Research: Leipzig, Germany, 2009; Available online: https://www.ufz.de/export/data/400/39013_WP1_Paper_D1_D3_FINAL300909.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Sousa, S.; Pinho, P. Planning for Shrinkage: Paradox or Paradigm. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, A.; Bernt, M.; Großmann, K.; Mykhnenko, V.; Rink, D. Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2013, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, S.; Grossmann, K. Challenges for large housing estates in light of population decline and ageing: Results of a long-term survey in East Germany. Habitat Int. 2013, 39, 232–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Y.; Wu, K. Shrinking cities in a rapidly urbanizing China. Environ. Plan. A 2016, 48, 220–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z. Sustainability of Urban Development with Population Decline in Different Policy Scenarios: A Case Study of Northeast China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmytkie, R.; Krzysztofik, R. The processes of incorporation and secession of urban and suburban municipalities: The case of Poland. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. Nor. J. Geogr. 2019, 73, 110–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prognoza dla Powiatów i Miast na Prawie Powiatu Oraz Podregionów na Lata 2014–2050 [Forecast for Poviats and Cities with Poviat Law and Subregions for 2014–2050]; Główny Urząd Statystyczny w Warszawie [Central Statistical Office in Warsaw]: Warszawa, Poland, 2014.

- Bytom w Liczbach [Bytom in Numbers]. Available online: https://www.polskawliczbach.pl/Bytom (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Project: Shrink Smart, Governance of Shrinkage within a European Context. Available online: https://www.ufz.de/shrinksmart/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Runge, A.; Runge, J.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Krzysztofik, R. Does urban shrinkage require urban policy? The case of a post-industrial region in Poland. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2020, 7, 476–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Machowski, R. (Eds.) Przemiany Przestrzenne Oraz Społeczne Bytomia i Jego Centrum. Studia i Materiały [Spatial and Social Changes of Bytom and Its Center. Studies and Materials]; Wydział Nauk o Ziemi Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Sosnowiec, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Morawski, W. Socjologia Ekonomiczna [Economic Sociology]; WN PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek, T. Krajowa polityka miejska i jej implementacja na poziomie regionu [National urban policy and its implementation at the regional level]. In Rozwój Regionalny i Polityka Regionalna [Regional Development and Regional Policy]; Churski, P., Ed.; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2013; Volume 24, pp. 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gminny Program Rewitalizacji. Bytom 2020 +[Commune Revitalization Program. Bytom 2020 +], 2017. Available online: http://bytomodnowa.pl/uploads/files/content/Gminny_Program_Rewitalizacji%20_Bytom_2020+_luty_2017.pdf (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Program Rewitalizacji Miasta Bytomia na Lata 2007–2020 [Bytom City Revitalization Program for 2007–2020]; Urząd Miejski w Bytomiu: Bytom, Poland, 2009.

- Internet Information Service of the City of Bytom. Available online: https://www.bytom.pl/ (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- 105 milionów dla Bytomia. Co Władze z Nimi Zrobią? [105 Million for Bytom. What will the Authorities do with Them?]. Available online: https://bytom.naszemiasto.pl/105-milionow-dla-bytomia-co-wladze-z-nimi-zrobia/ar/c3-1951254 (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- 100 mln euro dla Bytomia już blisko. Teraz Trzeba Umieć je Wydać [EUR 100 Million for Bytom is Close. Now You have to be Able to Spend Them]. Available online: https://bytom.naszemiasto.pl/100-mln-euro-dla-bytomia-juz-blisko-teraz-trzeba-umiec-je/ar/c3-2081876 (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Regionalny Program Operacyjny Województwa Śląskiego na lata 2014–2020 [Regional Operational Program of the Śląskie Voivodeship for the years 2014–2020]; Urząd Marszałkowski Województwa Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2019.

- Krzysztofik, R. Uruchomienie Mechanizmów Zmieniających Dotychczasową Ścieżkę Rozwoju Bytomia. Rekomendacje do Strategii Rozwojowej Bytomia [Initial Mechanisms Changing the Current Path Development of Bytom. Recommendations for the Development Strategy of Bytom]; Urząd Miejski w Bytomiu: Bytom, Poland, 2012.

- Czapiński, J.; Panek, T. (Eds.) Diagnoza Społeczna. Warunki i Jakość Życia Polaków [Social Diagnosis. The Conditions and Quality of Life of Poles]; Rada Monitoringu Społecznego [Social Monitoring Council]: Warszawa, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gwosdz, K. Ewolucja Rangi Miejscowości w Konurbacji Przemysłowej. Przypadek Górnego Śląska (1830–2000) [Evolution of the Rank of Settlements in an Industrial Conurbation. The Case of Upper Silesia (1830–2000)]; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego: Kraków, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rumpel, P.; Slach, O. Governance of Shrinkage of the City of Ostrava; European Science and Art Publishing Praha: Prague, Czech Republic, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Couch, C.; Karecha, J.; Nuissl, H.; Rink, D. Decline and sprawl: An evolving type of urban development—Observed in Liverpool and Leipzig. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2005, 13, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studziński, P. Przyczyny—Teraźniejszość [Causes—The Present]. Available online: http://www.ruiny.bytom.pl/ (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Prezydentowi nie Spodobały się Zrujnowane Kamienice [The President did not Like the Ruined Tenement Houses]. Available online: https://katowice.wyborcza.pl/katowice/1,35063,7578806,Prezydentowi_nie_spodobaly_sie_zrujnowane_kamienice.html (accessed on 28 August 2020).

- Bartholomae, F.; Nam, C.W.; Schoenberg, A. Urban shrinkage and resurgence in Germany. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 2701–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartholomae, F.W.; Nam, C.W.; Schoenberg, A. Urban Shrinkage in Eastern Germany. CESifo Working Paper Series No. 5200. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2573575 (accessed on 30 September 2020).

- Rink, D.; Haase, A.; Grossmann, K.; Couch, C.; Cocks, M. From Long-Term Shrinkage to Re-Growth? The Urban Development Tra-jectories of Liverpool and Leipzig. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swianiewicz, P. Poland. In The Second Tier of Local Goverment in Europe: Provinces, Counties, Departments and Landkreise in Com-parison; Heinelt, H., Bertrana, X., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Swianiewicz, P. An Empirical Typology of Local Government Systems in Eastern Europe. Local Gov. Stud. 2014, 40, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).