Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Understanding Domestic Food Waste via Ambivalence

1.2. How Ambivalence May Affect Food Waste

1.3. The Present Investigation

2. Experiment 1

2.1. Method

2.1.1. Participants and Design

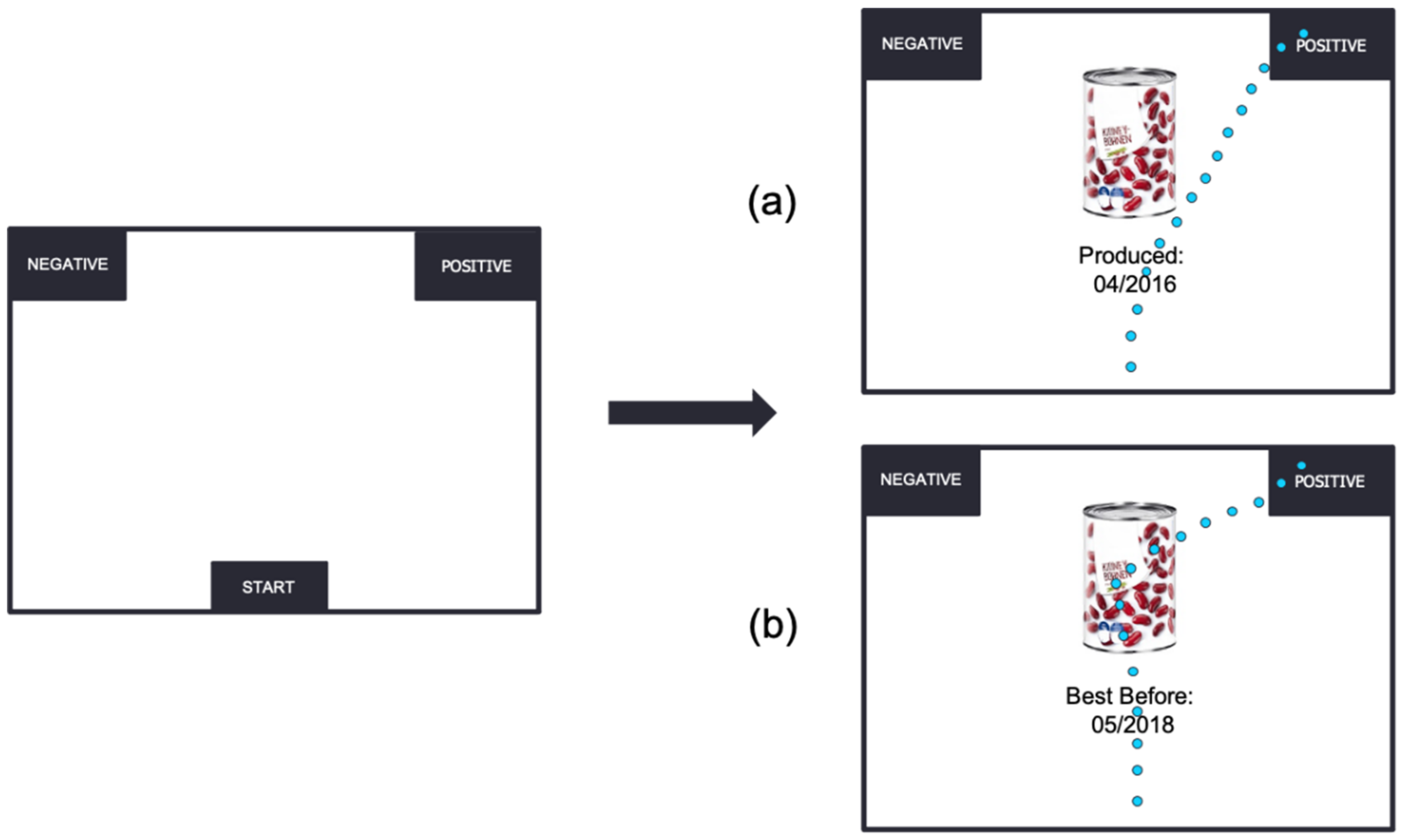

2.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Ambivalence

Willingness to Pay and Premeditated Waste

Labeling Knowledge and Demographics

2.2. Results

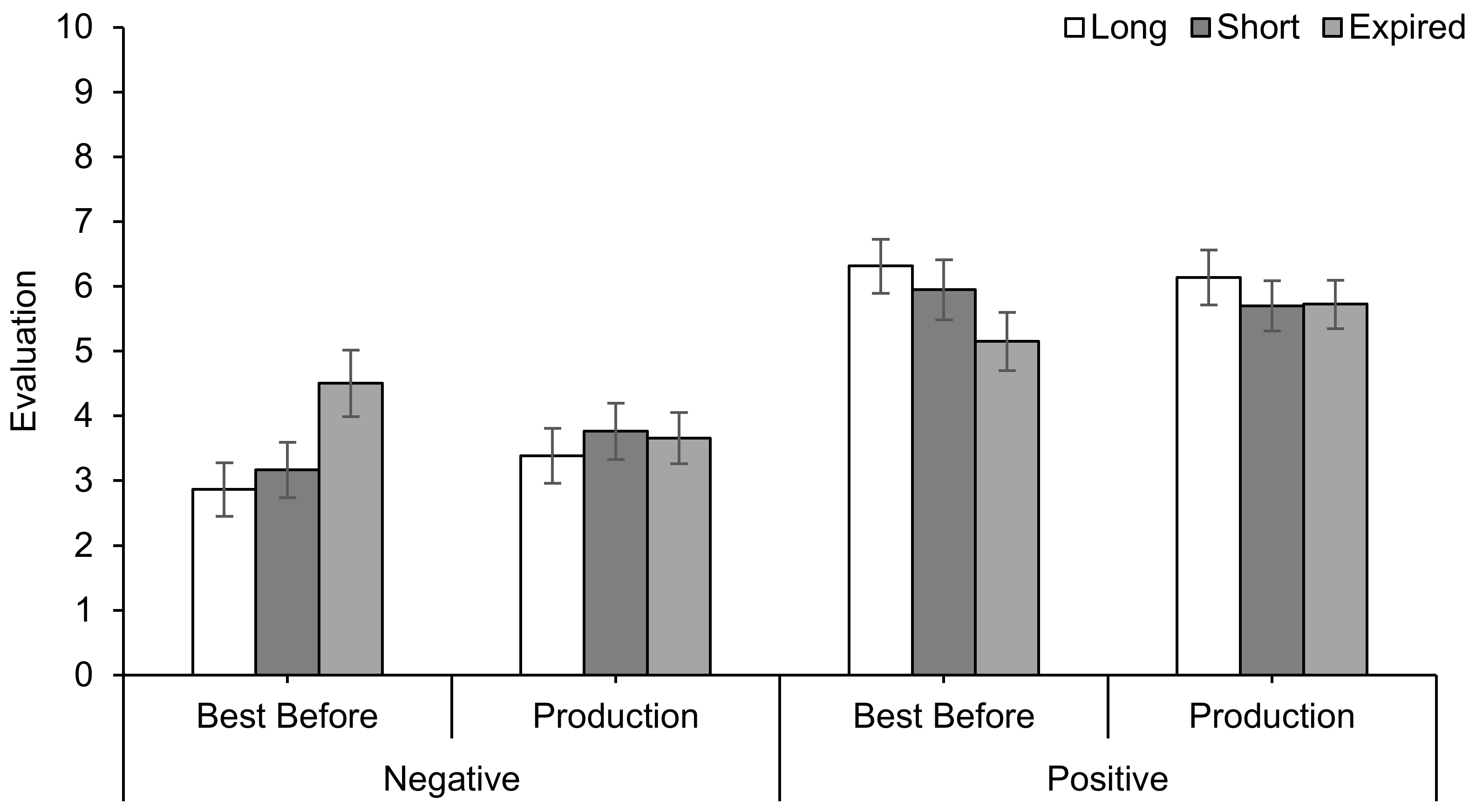

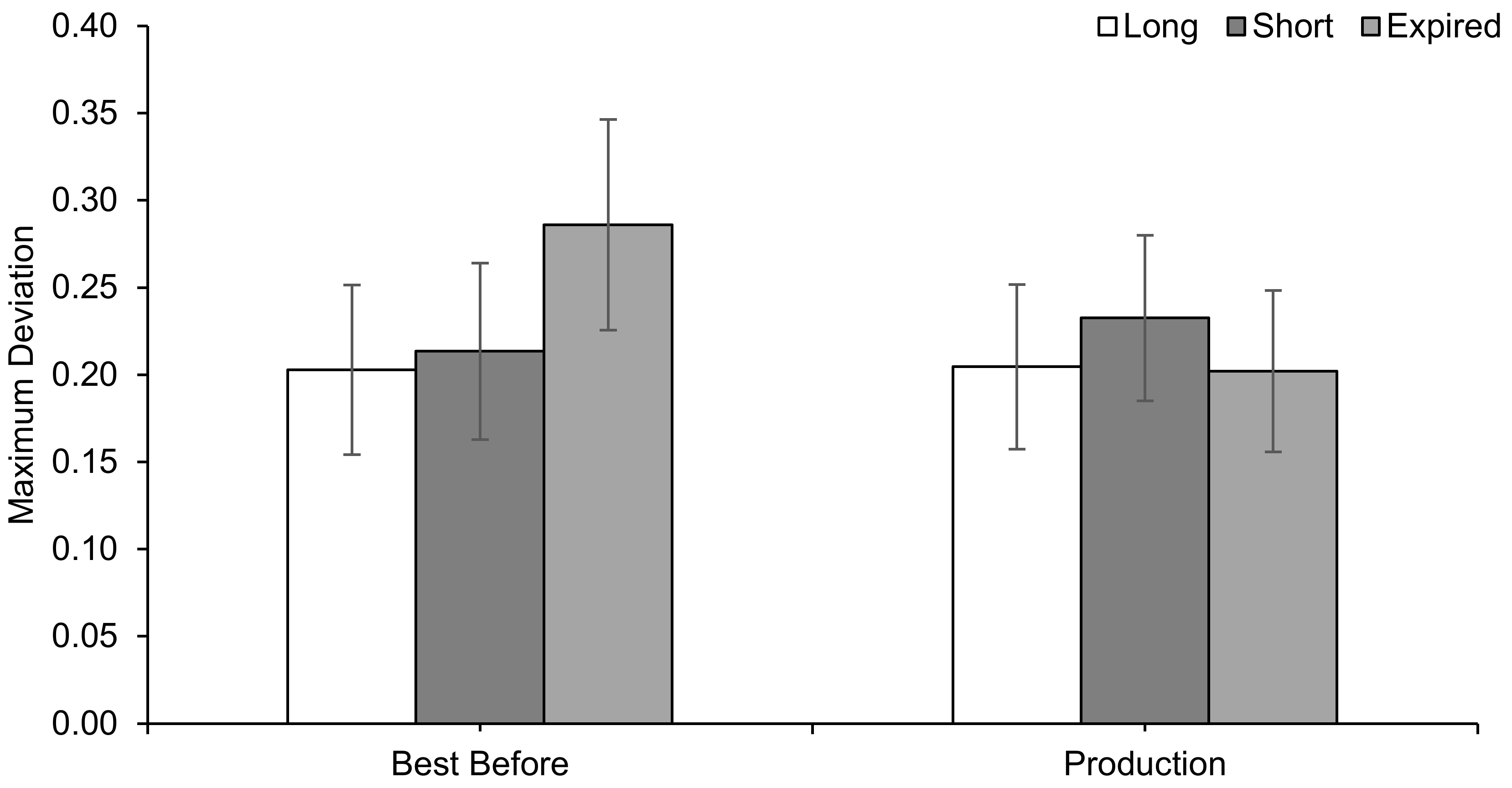

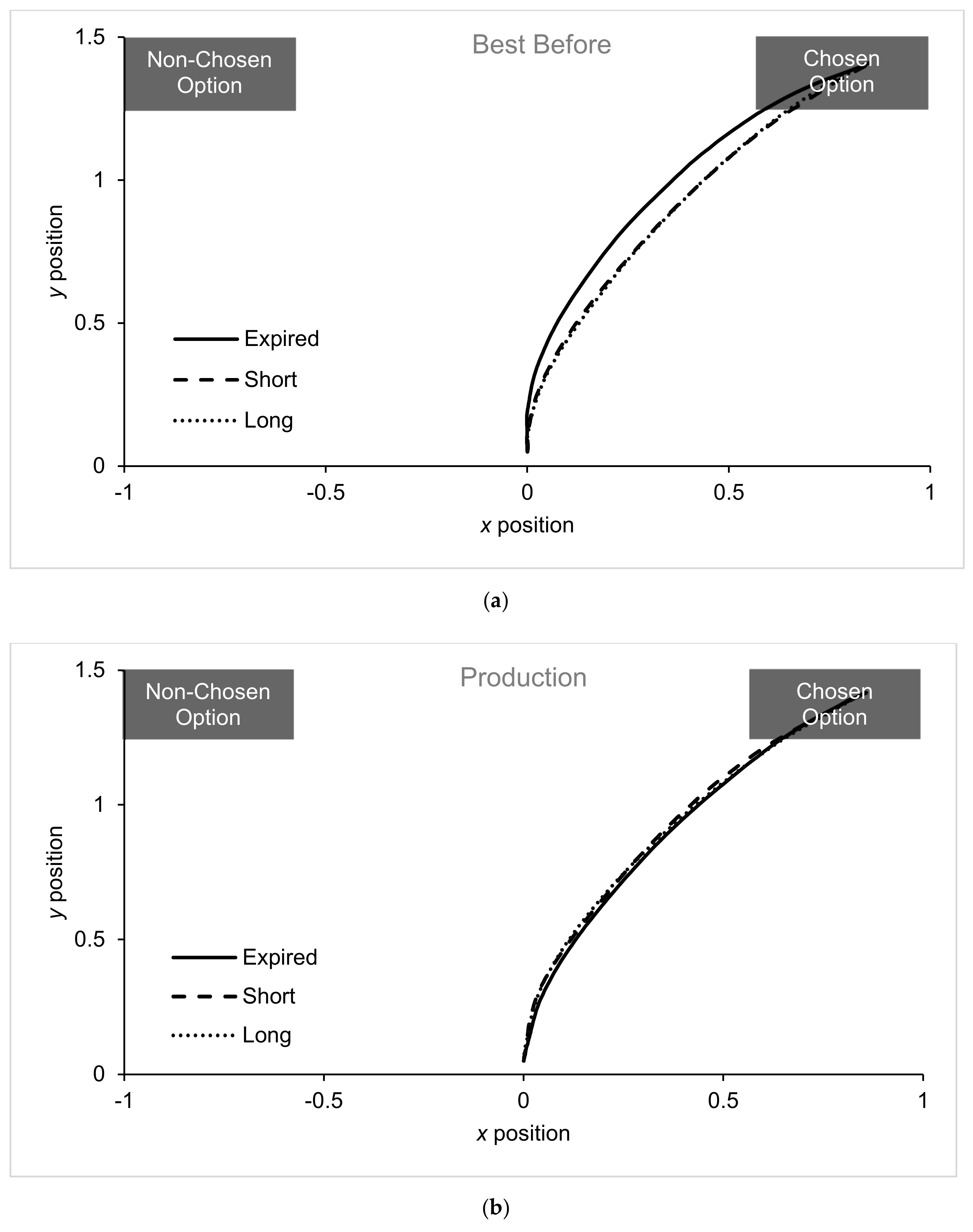

2.2.1. Hypothesis 1: The Effect of Date Labeling on Food-Related Ambivalence

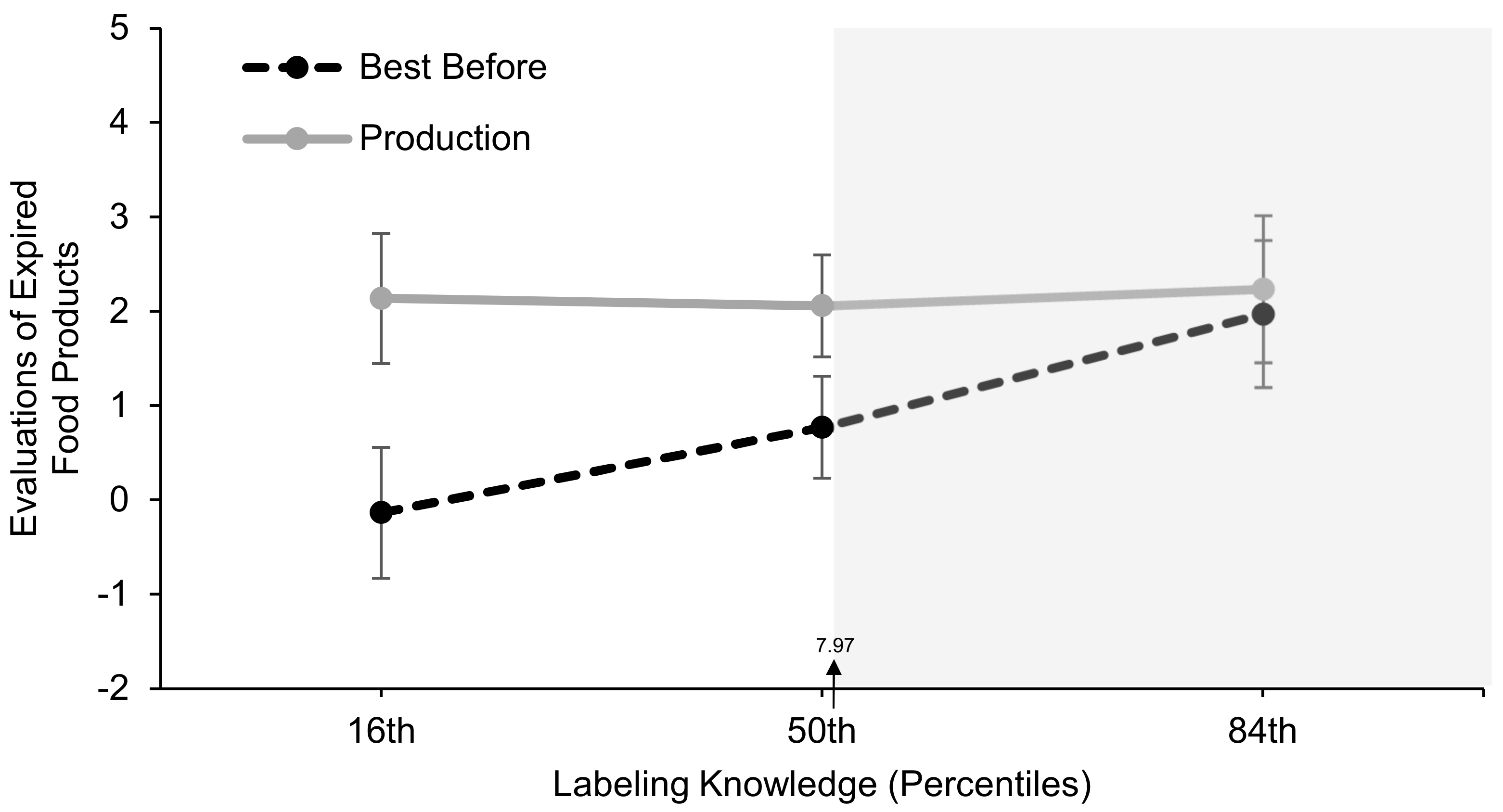

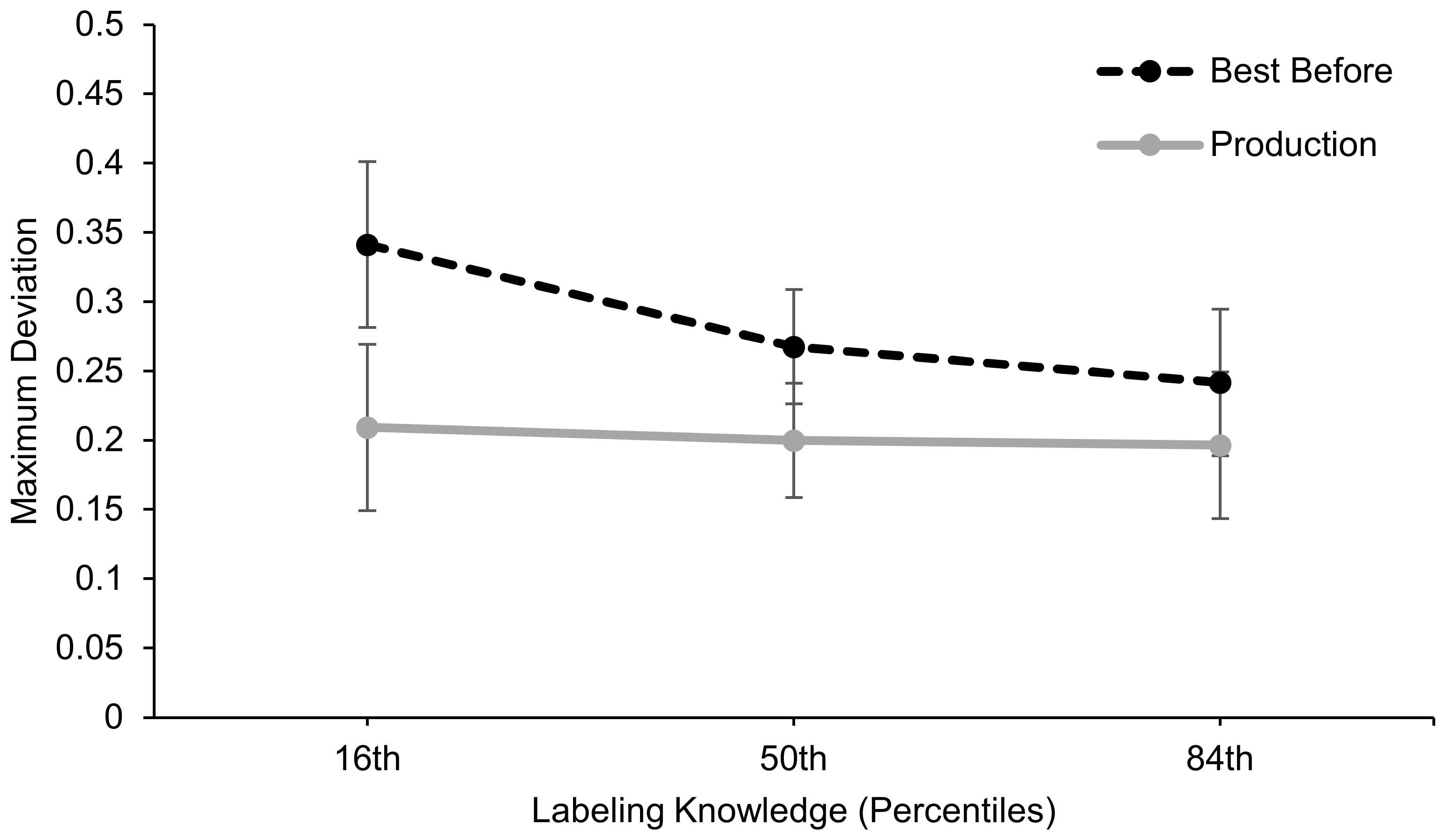

2.2.2. Hypothesis 2: Labeling Knowledge as a Moderator

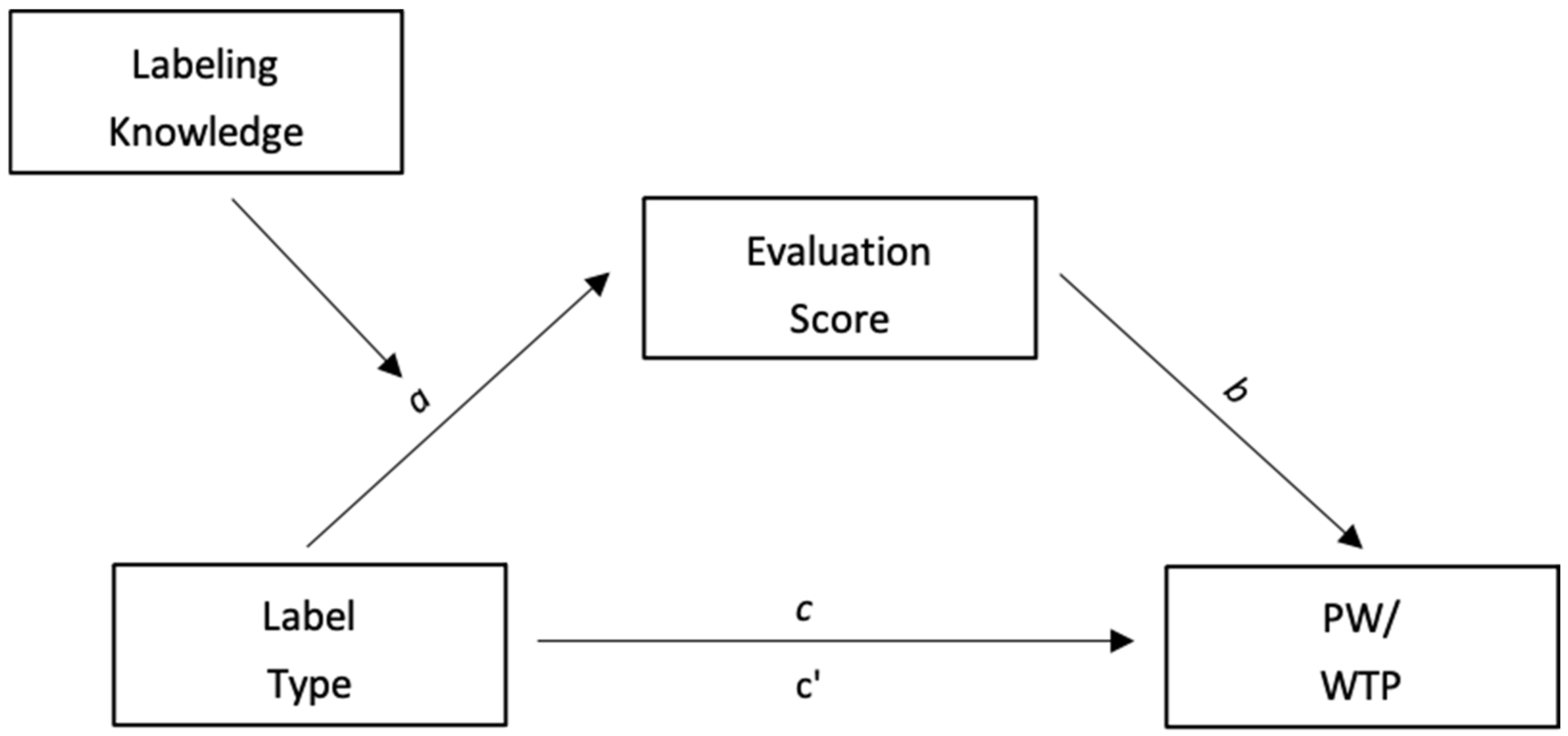

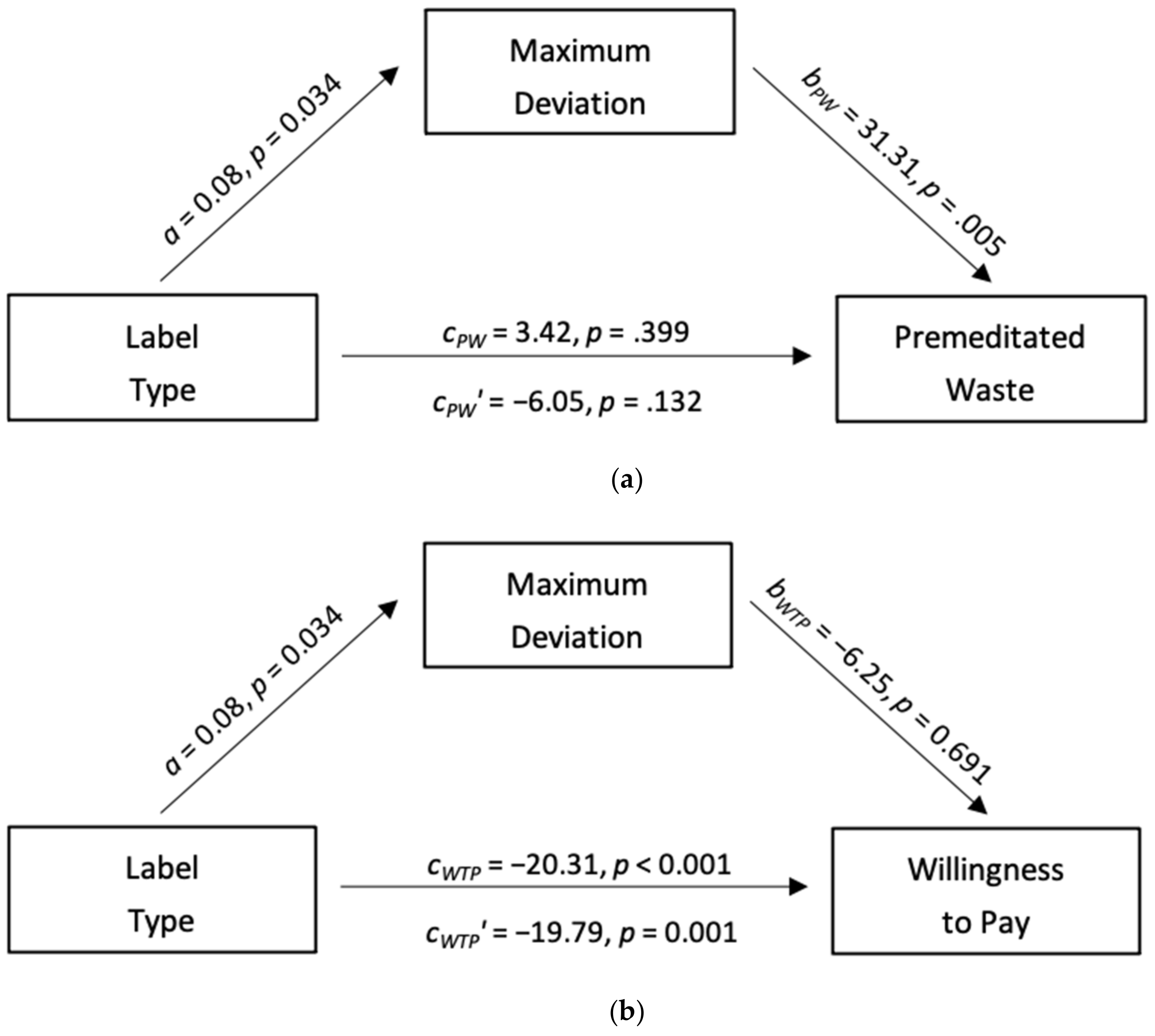

2.2.3. Hypothesis 3: How Evaluations Affect Premeditated Waste and Willingness to Pay

2.3. Discussion

3. Experiment 2

3.1. Method

3.1.1. Participants and Design

3.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Ambivalence

Willingness to Pay and Premeditated Waste

Labeling Knowledge and Demographics

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Hypothesis 1: The Effect of Date Labels on Food-Related Ambivalence

3.2.2. Hypothesis 2: Labeling Knowledge as a Moderator

3.2.3. Hypothesis 3: How Ambivalence Affects Premeditated Waste and Willingness to Pay

3.3. Discussion

4. Experiment 3

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants and Design

4.1.2. Materials and Procedure

Intervention

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Hypothesis 1: The Effects of the Information Interventions on Food-Related Ambivalence

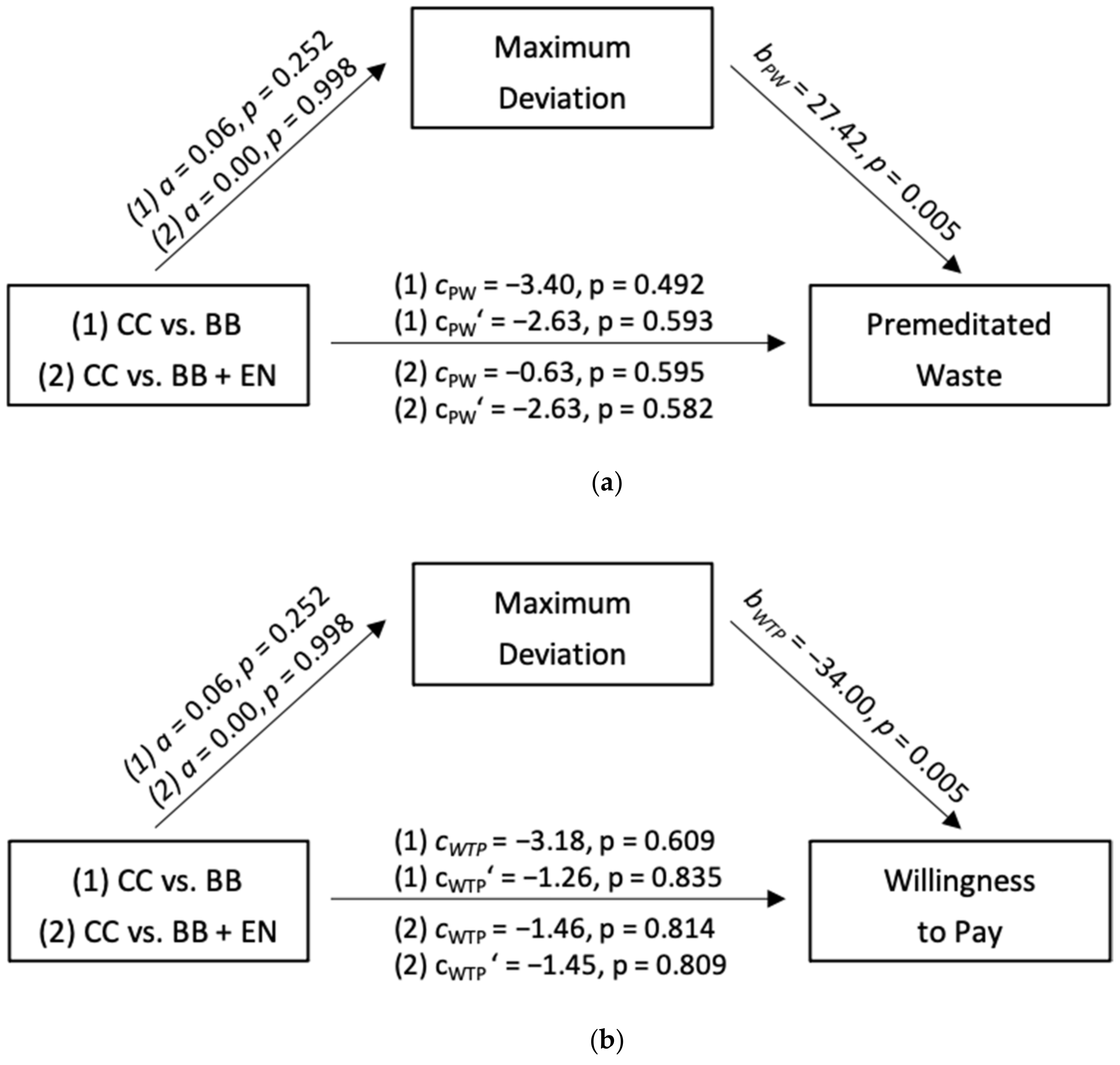

4.2.2. Hypothesis 2: How Ambivalence Affects Premeditated Waste and Willingness to Pay

5. General Discussion

5.1. Implications for Interventions on Food Waste

5.2. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No | Item |

|---|---|

| 1 | I would not eat food past its best before date. a |

| 2 | It is important, that even imperishable food like rice, pasta, coffee or tea are labeled with a best before date. a |

| 3 | Food can still be eaten when its best before date has expired even though it probably is not at its best quality anymore. |

| 4 | Imperishable food like rice, pasta, or sugar can be eaten even though its best before date has expired. |

| 5 | The best before date is the same as the use-by date. a |

| 6 | As soon as the best before date has expired, food should not be eaten anymore. a |

| 7 | Best before means that the food will be safe to eat up to this date but should not be eaten past this date. a |

| 8 | I would eat food even though its best before date has expired if the packaging is not damaged and the food still looks all right. |

| 9 | I would throw away a pack of spaghetti if it is not labeled with a best before date and I can not remember when I bought it. |

| 10 | I would use a package of rice even though it is not labeled with a best before date and I can not remember when I bought it. a |

Appendix B

- -

- In Germany, the best before date is generally mandatory. However, there are exceptions for certain foods. The best before date is determined by the responsible food business operator to the best of his knowledge and belief on the basis of studies or with the help of experts.

- -

- The best before date indicates the minimum date up to which a packaged food can be stored and consumed without losing specific properties, i.e., smell, taste, texture, nutritional value, and color. If stored correctly, food can be consumed beyond this date—after checking the smell and taste.

- -

- A distinction must be made between the best before date and the use-by date. The use by date indicates the date at which a food product should be disposed of; it concerns perishable foods such as minced meat and poultry. After this use by date, these foods may no longer be offered for sale and should not be consumed due to existing health hazards caused by germ contamination.

Appendix C

- -

- Looking at the entire value chain including the consumer, over 18 million tons of food are lost in Germany.

- -

- According to recent estimations, 10 million tons of this waste could be avoided; and with almost 5 million tons, the greatest avoidance potential lies with the end consumer.

- -

- Thus, in Germany, it is mainly private consumers who are responsible for food waste: Every person disposes of an average of 80 kg edible food per year.

- -

- The production of the 10 million tons of lost food, takes up an agricultural area that is larger than Mecklenburg-Vorpommern [a German federal state].

- -

- Agricultural land is scarce. Therefore, natural and often unique habitats are converted into farmland or pasture. This way, food waste threatens biodiversity.

- -

- By reducing their food waste, individuals could save about 227 kg CO2 equivalents. This corresponds approximately to a distance of 1360 km that could be covered by a middle-class car.

References

- FAO. Global Food Losses and Food Waste: Extent, Causes and Prevention; Study Conducted for the International Congress Save Food! In Proceedings of the Interpack 2011, Düsseldorf, Germany, 16–17 May 2011; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2011. ISBN 978-92-5-107205-9. [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa, H.; Williams, I.; Shaw, P.; Watanabe, K. Food waste prevention: Lessons from the love food, hate waste campaign in the UK. In Proceedings of the 16th International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium, Margherita di Pula, Sardinia, Italy, 2–6 October 2017; pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Stenmarck, Å.; Jensen, C.; Quested, T.; Moates, G.; Buksti, M.; Cseh, B.; Juul, S.; Parry, A.; Politano, A.; Redlingshofer, B.; et al. Estimates of European Food Waste Levels; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-91-88319-01-2. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Food Wastage Footprint: Impacts on Natural Resources: Summary Report; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2013; ISBN 978-92-5-107752-8. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions. Food Losses and Food Waste; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2016.

- FAO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World: Safeguarding against Economic Slowdowns and Downturns; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-92-5-131570-5. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Sustainable Development Goals 12.3. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-consumption-production/ (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Reynolds, C.; Goucher, L.; Quested, T.; Bromley, S.; Gillick, S.; Wells, V.K.; Evans, D.; Koh, L.; Carlsson Kanyama, A.; Katzeff, C.; et al. Review: Consumption-Stage Food Waste Reduction Interventions—What Works and How to Design Better Interventions. Food Policy 2019, 83, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging Pro-Environmental Behaviour: An Integrative Review and Research Agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanes, K.; Dobernig, K.; Gözet, B. Food Waste Matters—A Systematic Review of Household Food Waste Practices and Their Policy Implications. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 978–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckli, S.; Niklaus, E.; Dorn, M. Call for Testing Interventions to Prevent Consumer Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Jörissen, J.; Bräutigam, K.-R. Food Waste Prevention in Europe—A Cause-Driven Approach to Identify the Most Relevant Leverage Points for Action. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 109, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Matthies, E. Where to Start Fighting the Food Waste Problem? Identifying Most Promising Entry Points for Intervention Programs to Reduce Household Food Waste and Overconsumption of Food. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 139, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collart, A.; Interis, M. Consumer Imperfect Information in the Market for Expired and Nearly Expired Foods and Implications for Reducing Food Waste. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham-Rowe, E.; Jessop, D.C.; Sparks, P. Identifying Motivations and Barriers to Minimising Household Food Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2014, 84, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T.; Schneider, F.; Claupein, E. Food Waste in Private Households in Germany—Analysis of Findings of a Representative Survey Conducted by GfK SE in 2016/2017. Thünen Work. Pap. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harreveld, F.; Nohlen, H.U.; Schneider, I.K. The ABC of Ambivalence. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 52, pp. 285–324. ISBN 978-0-12-802247-4. [Google Scholar]

- Quested, T.; Parry, A. Household Food Waste in the UK, 2015; Wastes & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiros, M.; Heilman, C.M. The Effect of Expiration Dates and Perceived Risk on Purchasing Behavior in Grocery Store Perishable Categories. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, G.; Phillips, C. Food Waste and Domestic Refrigeration: A Visceral and Material Approach. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2016, 17, 359–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K. Predicting the Consumption of Expired Food by an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Harreveld, F.; van der Pligt, J.; de Liver, Y.N. The Agony of Ambivalence and Ways to Resolve It: Introducing the MAID Model. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D. Beyond the Throwaway Society: Ordinary Domestic Practice and a Sociological Approach to Household Food Waste. Sociology 2012, 46, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German Research Foundation FAQ: Informationen Aus Den Geistes- Und Sozialwissenschaften [FAQ: Information for Humanities and Social Sciences]. Available online: https://www.dfg.de/foerderung/faq/geistes_sozialwissenschaften/index.html (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, I.K.; van Harreveld, F.; Rotteveel, M.; Topolinski, S.; van der Pligt, J.; Schwarz, N.; Koole, S.L. The Path of Ambivalence: Tracing the Pull of Opposing Evaluations Using Mouse Trajectories. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D.; Evers, E.R.K. Sailing From the Seas of Chaos Into the Corridor of Stability: Practical Recommendations to Increase the Informational Value of Studies. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 9, 278–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. Sample Size Justification. PsyArXiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.M.; Zanna, M.P.; Griffin, D.W. Let’s not be indifferent about (attitudinal) ambivalence. In Attitude Strength: Antecedents and Consequences; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1995; Volume 4, pp. 361–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, N.L.W.; Rickard, B.; Saputo, R.; Ho, S.-T. Food Waste: The Role of Date Labels, Package Size, and Product Category. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 55, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, D. Mit Unschönem Lauch Geht’s Auch [It Works, Even with Imperfect Leeks]. Taz, 18 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Flash Eurobarometer 425—September 2015. Food Waste and Date Marking. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/FLASH/surveyKy/2095 (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Girden, E.R. ANOVA: Repeated Measures; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8039-4257-8. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, P.O.; Neyman, J. Tests of Certain Linear Hypotheses and Their Application to Some Educational Problems. Stat. Res. Mem. 1936, 1, 57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4625-3465-4. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, J.B.; Ambady, N. MouseTracker: Software for Studying Real-Time Mental Processing Using a Computer Mouse-Tracking Method. Behav. Res. Methods 2010, 42, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- German Bundestag Mindesthaltbarkeitsdatum. Nationaler Regelungsspielraum Und Fachwissenschaftliche Diskussion [Best before Dates. National Regulatory Leeway and Scientific Discussion]. Available online: https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/659870/1265fe4efbc90aa1ca13ac6dd1c7820b/WD-5-077-19-pdf-data.pdf (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Noleppa, S.; Cartsburg, M. Das Große Wegschmeißen, Vom Acker Bis Zum Verbraucher: Ausmaß Und Umwelteffekte Der Lebensmitteverschwendung in Deutschland [The Big Throw-Away. From the Field to the Consumer: Extent and Environmental Effects of Food Waste in Germany]; WWF Deutschland: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buttlar, B.; Rothe, A.; Kleinert, S.; Hahn, L.; Walther, E. Food for Thought: Investigating Communication Strategies to Counteract Moral Disengagement Regarding Meat Consumption. Environ. Commun. 2020, 15, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, M.C.; Scheufele, D.A. What’s next for Science Communication? Promising Directions and Lingering Distractions. Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: Reactions and Reflections. Psychol. Health 2011, 26, 1113–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, R.; Sheeran, P. Moderation of Cognition-Intention and Cognition-Behaviour Relations: A Meta-Analysis of Properties of Variables from the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 43, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Sparks, P.; Povey, R.; James, R.; Shepherd, R.; Armitage, C.J. Moderator Effects of Attitudinal Ambivalence on Attitude–Behaviour Relationships. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 705–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Povey, R.; Sparks, P.; James, R.; Shepherd, R. Moderating Role of Attitudinal Ambivalence within the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 42, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, M.; Armitage, C.J. Attitudinal ambivalence. In Attitudes and Attitude Change; Frontiers of Social Psychology; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 261–286. ISBN 978-1-84169-481-8. [Google Scholar]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Attitudinal Ambivalence: A Test of Three Key Hypotheses. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2000, 26, 1421–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.M.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out Food Waste Behaviour: A Survey on the Motivators and Barriers of Self-Reported Amounts of Food Waste in Households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappellini, B. The Sacrifice of Re-Use: The Travels of Leftovers and Family Relations. J. Consum. Behav. 2009, 8, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why Do People Act Environmentally and What Are the Barriers to Pro-Environmental Behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quested, T.; Johnson, H. Household Food and Drink Waste in the UK: Final Report; Wastes & Resources Action Programme (WRAP): Banbury, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

| Evaluations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | 0.029 * | |||

| Label Type | −1.42 | 0.55 | −0.17 | |

| Step 2 | 0.018 * | |||

| Label Type | −1.42 | 0.55 | −0.17 | |

| Labeling Knowledge | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.13 | |

| Step 3 | 0.037 * | |||

| Label Type | −1.42 | 0.55 | −0.17 | |

| Labeling Knowledge | 0.48 | 0.20 | 0.16 | |

| Interaction | 1.19 | 0.40 | 0.19 | |

| Premeditated Waste (PW) | Willingness to Pay (WTP) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditional Indirect Effect | ab | 95% CI | ab | 95% CI |

| Low Knowledge | 3.38 | [1.05, 6.51] | −2.78 | [−6.11, −0.17] |

| Medium Knowledge | 1.60 | [0.89, 3.61] | −1.32 | [−3.26, 0.01] |

| High Knowledge | −0.32 | [−2.60, 1.83] | 0.26 | [−1.47, 2.45] |

| Ambivalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | |

| Step 1 | 0.051 * | |||

| Label Type | 0.083 | 0.04 | 0.227 | |

| Step 2 | 0.025 | |||

| Label Type | 0.083 | 0.039 | 0.225 | |

| Labeling Knowledge | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.160 | |

| Step 3 | 0.012 | |||

| Label Type | 0.083 | 0.039 | 0.226 | |

| Labeling Knowledge | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.114 | |

| Interaction | −0.001 | 0.001 | −0.111 | |

| Control Condition | Date Labeling | Date Labeling + Environmental | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD M(SD) | PW M(SD) | WTP M(SD) | MD M(SD) | PW M(SD) | WTP M(SD) | MD M(SD) | PW M(SD) | WTP M(SD) | |

| Long | 0.20(0.15) | 48.78(24.06) | 81.29(17.83) | 0.15(0.14) | 44,08(27.48) | 78.33(19.35) | 0.17(0.19) | 40.78(21.95) | 74.73(21.22) |

| Short | 0.17(0.14) | 50.34(23.07) | 71.80(21.78) | 0.18(0.17) | 44.73(26.69) | 71.12(20.14) | 0.18(0.22) | 43.64(22.18) | 69.32(20.37) |

| Expired | 0.25(0.17) | 58.35(17.74) | 52.98(25.19) | 0.30(0.24) | 54.95(23.87) | 49.80(28.33) | 0.25(0.21) | 55.73(20.71) | 51.52(25.18) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buttlar, B.; Löwenstein, L.; Geske, M.-S.; Ahlmer, H.; Walther, E. Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073971

Buttlar B, Löwenstein L, Geske M-S, Ahlmer H, Walther E. Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073971

Chicago/Turabian StyleButtlar, Benjamin, Lars Löwenstein, Marie-Sophie Geske, Heike Ahlmer, and Eva Walther. 2021. "Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073971

APA StyleButtlar, B., Löwenstein, L., Geske, M.-S., Ahlmer, H., & Walther, E. (2021). Love Food, Hate Waste? Ambivalence towards Food Fosters People’s Willingness to Waste Food. Sustainability, 13(7), 3971. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073971