Abstract

Recent years have seen the development of numerous innovations in social, constructional, and transportation planning for different forms of communal housing. They illustrate how more sustainable practices in transport and land use can be achieved through the collective provision and use of space and mobility services. The question remains, however, of who needs to be involved in such bottom-up approaches and when in order to ensure their success. What changes are necessary to anchor these approaches in the wider context of urban and transport planning? This paper presents three examples of neighbourhood mobility concepts and the collaborative use of space and land. A research project accompanied the development of these concepts in a real-world laboratory design. The scientists used social-empirical methods and secondary analyses to evaluate social and ecological effects, economic viability and the process of joint development. The results show the high sustainability potential of such neighbourhood concepts: they enable residents to meet their mobility needs, while using fewer vehicles through shared use, reducing the number of journeys and changing their choice of transport. At the same time, promoting and developing community services has been shown to be inhibited by preconditions such as existing planning law. Opportunities and obstacles have been identified and translated into recommendations for action, focusing on municipal urban planning, transport planning, and the housing industry.

1. Background and Motivation

Different forms of co-housing have been emerging from bottom-up approaches for several years [1]. The estimated number of co-housing initiatives in Germany has now grown to over 3000 [2], and while their number is still relatively small, their impact as role models for a more sustainable way of living is of great importance. Bottom-up planning in the housing industry could have the potential to transform the nexus between the housing and transport sectors and therefore the entire urban structure. Shared mobility is skyrocketing in cities worldwide. Most sharing services such as car sharing and the sharing of micromobility (e.g., bicycles, electric scooters) are of commercial character and form a subset of a larger sharing economy [3]. Nonetheless, non-commercial and communal forms of sharing are of crucial importance for enhancing urban sustainability as well [4] and form the research object of this paper. Research on co-housing-based sharing services has been conducted since the early 2000s and services have been systematized and studied in terms of their sustainability potential [5,6]. Numerous studies point to the positive sustainability impacts of these services: from an ecological, social, and economic perspective as they can reduce the number of trips, change the use of transport modes, and facilitate equal access opportunities for residents [7,8,9,10]. Communal forms of sharing are also particularly relevant in the context of the global COVID-19 pandemic. While pandemic prevention measures impose strict limitations on individual mobility [11,12], findings indicate that these restrictions affect low-income households particularly acutely [13]. Communal sharing can be of key importance here [14]: it offers an alternative to commercial services enabling more crisis-resilient forms of mobility through building on existing networks of trust.

The sustainability potential of co-housing initiatives has been proven by a multitude of studies. In a systematic review of quantitative studies on community-based initiatives (also known as intentional communities), Daly [7] compared studies on 23 different co-housing and ecovillage projects, located mostly in Europe and North America. He found that community-based initiatives have a much lower environmental footprint than regional conventional settlements: on average, the ecological footprint was 50% and the carbon footprint around 35% lower. Additional evidence from the vast majority of studies strongly indicates that these community-based initiatives do indeed achieve lower environmental impacts than comparable mainstream communities. The studies agree that two of the most significant factors contributing to the lower ecological footprint of community-based initiatives were housing and transportation. Regarding co-housing, the sharing of communal spaces and shared mobility are the main drivers of a reduced ecological footprint [15,16]. Behavioural patterns also play an important role and are considered by some studies to be more important for ecological sustainability than physical infrastructure [17,18].

Steps to more sustainable urban living concepts have recently been taken by a variety of community-based initiatives. These initiatives can take on different organisational forms such as building societies and associations, or they can be part of housing companies and co-operatives with a common interest. These initiatives can result from either bottom-up or top-down approaches. Studies comparing top-down and bottom-up approaches in co-housing have shown substantial differences. Top-down interventions aim primarily on technical solutions and individual behavioural change and have had little impact on residents’ mobility and energy consumption patterns. In contrast, bottom-up approaches were much more successful in reconfiguring the daily behaviour of residents to become more sustainable [9]. This difference is due to the specific philosophy and governance structure in community-based initiatives opening up a greater scope for experimenting with novel practices. Distinctive features of community-based initiatives such as co-housing are that members have a shared vision, shared values, and collective decision-making processes. These communities are thus able to define strong collective agreements, standards, or even binding rules in order to reconfigure daily practices towards more sustainable practices. Moreover, measures can be taken in multiple areas (mobility, housing, energy, etc.) and be combined into integrative approaches. This allows for more integral modification of behaviour instead of top-down interventions targeting only single behaviours. By altering housing and mobility routines via a bottom-up approach, co-housing initiatives reconfigure daily practices, develop social innovations, and act as laboratories for social and structural change. Hence, they offer experiences and inspiration for societal transformation on a broader scale [9]. In contrast to this, traditional top-down planning strategies tend to neglect the need to create structures enabling residents to adopt more sustainable behavioural patterns. While top-down planning is appropriate on regional and more strategical levels, bottom-up approaches are described as most suitable on local scales, as pointed out by Pissourios [19]. By embedding planning processes at a neighbourhood level in the context of social relations and the day-to-day practices of its residents, decisions are based on consensus-building practices. They are highly adaptable to local circumstances [19,20] and foster a so-called “participative urbanism” [21].

The core characteristic of a bottom-up approach is therefore the joint decision-making process. The involvement of all residents supports sustainable planning principles that enable short distances between areas such as living, working, leisure, and care work [22]. Diverse forms of co-housing typically combine a broad range of goals such as providing affordable housing for several generations, socio-cultural diversity and the exchange of ideas and experiences between the residents, the promotion of environmentally friendly mobility, the design and creation of an atmosphere of harmony in building and living, and the realisation of high energy and resource efficiency. In order to realise one or more of these objectives, many initiatives offer residential services. These can include jointly organised car sharing services, food co-ops, joint workshops, community gardens, open spaces, or common rooms, depending on the interests and needs of the residents. Schneidewind and Scheck [23] state that such services, if disseminated, can function as system innovations and initiate change processes by establishing new practices in socio-technical systems. However, there are hardly any approaches or case studies to find out how such services emerge and how they work [24]. Moreover, it is often stated by residents in co-housing initiatives that social innovations require a high level of commitment and considerable personal effort, which is difficult to sustain on a voluntary basis in the long run without incurring extra cost. Nonetheless, many municipal housing companies and traditional co-operatives would like to support and renew the idea of community and common good and therefore add some elements to their main business models where they include co-housing.

Many of these approaches have now also been taken up by the commercial housing industry and are marketed under keywords such as serviced housing or micro apartments. Although these housing concepts also offer shared services, this is more likely to come from top-down planning rather than through a joint negotiation and development process. In other words, they offer only isolated elements of integrated co-housing services and are not aiming to strengthen sustainability. Time-intensive bottom-up processes that allow for user participation and reciprocal relationships are mostly ruled out by commercial housing providers for being unprofitable. From their perspective, bottom-up community services are still not particularly marketable nor economically viable. However, it is through those bottom-up processes that progressive planning principles are often implemented [9].

Up-to-date, bottom-up approaches are usually the result of individual efforts and are often out of line with existing planning policies and regulations (such as parking space requirements). This makes implementation challenging and hinders the diffusion of bottom-up practices. Scaling up, in the sense of introducing similar projects to other parts of the housing sector, has proved difficult.

In this paper, we explore the overall research question of how co-housing initiatives can contribute to foster more sustainable mobility and space-use practices. From this overall objective, the following research questions and corresponding hypothesis are deduced: a first research question is how the sustainability of co-housing-related services can be assessed appropriately (Q1). Our hypothesis is that sustainability potentials of participatorily created co-housing initiatives can only be fully understood if their ecological, economic, and social impacts are taken into consideration, applying an integrated evaluation framework (hypothesis H1). The second research question is how transport and urban planning processes can be designed in order to enable and promote sustainable co-housing approaches (Q2). Our hypothesis is that the sustainability impact increases with an early integration of the service design in the overall planning process (H2). In addition, we focus on how actors can be actively involved in each stage of the planning and implementation process (Q3). We assume that contextual factors play an important role, because of strong interrelationships between framework conditions and participating actors. We suppose that the active involvement of all stakeholders potentially involved strengthens the potential of bottom-up approaches to reconfigure the daily practices of residents to become more sustainable. By enhancing this participative element, co-housing can better adapt their residential services to users’ needs (H3). The relationship between user and institutional actors, especially housing providers, is one of the lesser studied aspects of co-housing [1].

To answer these questions, this paper builds on the empirical results of the transdisciplinary research project “WohnMobil”, conducted from 2016 to 2018 [24,25,26,27]. The aim of this research project was to investigate how residential sharing services linking sustainable housing- and mobility-related practices can be fostered and scaled up to contribute significantly to a social-ecological transformation. It investigated three co-housing initiatives in Germany which implemented different forms of shared services.

Drawing on the results and experiences gained in the research project, opportunities and obstacles can be identified and translated into recommendations for community housing groups, housing providers, municipal planners, and bodies at state or federal level. Furthermore, the role of the different actors (community members, internal and external experts, and key players) will be analysed. This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the research framework, the case studies and the theoretical and methodical approach of the “WohnMobil” project. The results relevant to the research question of this paper are presented in Section 3. In Section 4, there follows a discussion that compares the findings and points out similarities and differences. These are then translated into recommendations for action in Section 5.

2. Research Frame (Real-World Laboratories) and Methods

The empirical investigation is based on a research framework, applying a real-world-laboratory (RWL) approach. In a first step, the underlying RWL research concept is described. Subsequently, the design of the research is outlined briefly before going on to describe the method of analysis for the sustainability impact assessment.

2.1. Research Framework

In order to explore how housing-related services evolve from bottom-up and how and by whom these processes can be supported, a RWL approach was chosen as an appropriate research framework. The RWL approach provides a feasible framework for triggering and studying sustainability transformations which is open enough to be developed further together with stakeholders and practitioners enrolled in the research process [28]. A RWL is a research concept that produces transdisciplinary knowledge for sustainability transformations in real-world settings [29,30], for instance by developing solutions to local sustainability problems [31] and studying them under controlled conditions. It therefore refers to “a social context in which researchers conduct interventions (…) to learn about social dynamics and processes (…) There are close links to concepts of field and action research” [32]. An RWL approach is particularly suited to exploring the conditions under which socio-technical innovations evolve in a joint process of science and practice and can be transferred to other contexts. On the one hand, knowledge transfer processes are initiated, and on the other hand, these processes are accompanied and examined with regard to their potential and effects (see Section 2.3). The RWL concept manifests a threefold approach towards research and societal problems: they are normative in character and seek to bring about long-term transformation, they deploy transdisciplinary methods, and they operate under lab-like conditions. Their main outcome is the provision of orientation knowledge to help understand the possibilities and boundaries of potential decisions, and of transformation knowledge fostering sustainable changes [33].

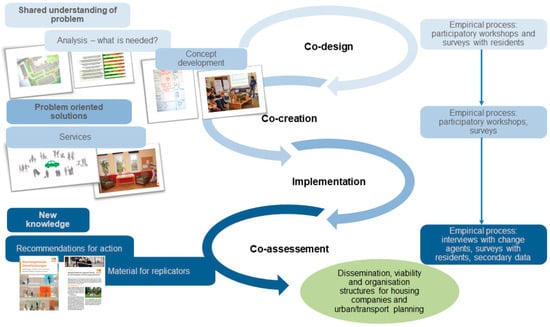

The research structure of the RWL was combined with a sustainability assessment approach (see Section 2.3). Sustainability assessments usually refer to very specific contexts that need to be taken into account and are concretely addressed accordingly when choosing individual sustainability indicators. Assessment concepts on a small-scale (e.g., neighbourhoods) also invoke sustainable development goals (SDGs), such as those outlined by Reyes Nieto et al. [34]. Holistic consideration of ecological, institutional, and economic aspects are the main parameters. In a review on recent urban sustainability assessments, Reyes Nieto et al. [34] concluded that social indicators are considered only to a lesser extent in the analysed literature. They developed their own holistic approach that considers social indicators to be of a higher weight in the analysis. The assessment approach developed and applied in this study addresses these points accordingly (see Section 2.3.1, Section 2.3.2 and Section 2.3.3). Figure 1 shows the schematized research framework.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

The RWL approach offers a flexible and adaptive research framework to generate transdisciplinary knowledge on enablers and inhibitors of sustainability transformation processes, fostering social learning among researchers and stakeholders. In many cases, the RWL approach is used in an explorative way. In our study, the RWL approach is combined with sustainability assessment methods (see Section 2.2). This methodology is applied for a structured and cross-cutting investigation of three RWL processes, drawing on the research questions and hypotheses which were developed in the previous chapter.

2.2. Development of Shared Residential Services in Real-World Laboratories

The project focused on new forms of co-operation among residents, and between residents, housing suppliers, and service providers. A major task was therefore to develop and integrate various types of knowledge (on residents’ needs, scientific and expert input on sustainability services, and economic constraints).

Embedded in the RWL design, three co-housing initiatives were selected for the WohnMobil project. During a one-and-a-half-year process, the research team supported the development of residential sharing services, which were subsequently evaluated for their sustainability impacts. The specific services were planned and implemented together with the residents of a housing association complex in the city of Pirmasens (34 housing units, approximately 50 residents) and two co-housing initiatives, one located in Berlin and one in its surrounding area (henceforth referred to as Greater Berlin), each having approximately 70 housing units and 120–150 residents. The residents of the co-housing initiative in Pirmasens moved in between 2015 and 2017, while those of the initiative in Greater Berlin took up residence during the period 2016–2017. In contrast, the residents of the co-housing initiative in Berlin had already been living there since 2014, prior to the start of the RWL.

All initiatives offered various shared services adapted to the respective residents, but for each RWL one service was selected as the focal point of implementation and analysis. In the case of the Pirmasens co-housing initiative, this was the creation of a multifunctional common room, equipped by the participants as a fitness room with an area for handicrafts/DIY (see Figure 2, left). Concepts for neighbourhood mobility services were installed at the co-housing initiatives in Greater Berlin and Berlin itself. These included institutionalised, flexible, and unbureaucratic neighbourhood car sharing via a booking and billing platform that integrated usage fees, jointly regulated insurance, and jointly agreed terms of use (see Figure 2, right). The service also extended to bicycles and cargo bikes, handled via informal sharing.

Figure 2.

Examples of the multifunctional room (used as a fitness room) and the mobility-sharing tool used for the neighbourhood sharing services (Source: WohnMobil project, otua.de).

The set of co-housing initiatives selected covers a range of different conditions in terms of organisational and legal structures and the composition of tenants. Furthermore, the different settings included urban and sub-urban locations and very different preconditions regarding mobility patterns and car ownership. For more detailed information about the three co-housing initiatives, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of the co-housing initiatives investigated.

2.3. Sustainablity Impact Assessment

The researchers analysed and evaluated the use of the services and their effects over several months during the establishment, use, and further development of the shared residential services. Figure 3 shows an abstract model of the process of the RWL.

Figure 3.

Idealised process for the real-world laboratories in the WohnMobil project.

2.3.1. Review of Sustainability Indicators

The review and inclusion of existing sustainability indices (SDG, German Sustainability Strategy, OECD Better-Life Index) initially served as a theoretical basis for the criteria to be considered in the assessment. Inductive derivation from the everyday life of the residents and practice partners was necessary to take account of the respective RWL-specific differences in terms of the spatial setting, various processes, and actors. Findings in this regard were validated through focus group discussions with the residents and community delegates. The sustainability indicators developed in this combined approach could then be validated via empirical surveys and—if necessary—put into an overall context. The evaluation framework that was subsequently developed included social, ecological, and economic impact criteria for the selected services in the three RWLs. The dimensions and indicators for the evaluation are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Criteria of the evaluation framework. The elaboration of each criterion differs according to the specific RWL/service.

2.3.2. Empirical Methods for the Impact Assessment

The specific situations in the three RWLs required a combination of qualitative and standardised social research methods to ask the residents about the services and assess the evaluation indicators. Focus groups and surveys via the internet or telephone were used as a primary source of information (see Figure 3). In addition, further quantitative data on the structure and use of the services was collected and supplied directly by the contact persons in the RWL and through the analysis of secondary data [26]. The process evaluation was achieved by methods such as interviews with the delegates and focus group discussions. Not all survey methods were applied equally in all RWLs. In the initial phase of the RWL, it became evident that some of the residents (especially in the Pirmasens co-housing initiative) were more easily activated and creative when the survey formats were integrated into regular meetings and resident interactions, since the focus here was more on the routines of the more elderly residents. For this reason, the survey methods were adapted gradually. In the initial phase, a focus group and a survey via the internet or telephone were chosen to find out about the residents’ interests and the potential use of various services. However, the low response to the telephone survey indicated that for later surveys face-to-face interviews would enjoy greater acceptance among the residents. This was taken into account in the surveys towards the end of the RWL phase.

The different empirical steps were integrated into a comprehensive analysis for evaluation. The qualitative results were categorised according to the evaluation criteria and supplemented with quantitative evaluations. Quantitative data, such as frequency of use, were particularly relevant for the economic evaluation. Where both standardised and qualitative data were available, the qualitative results were categorised/content-analysed according to the evaluation criteria and supplemented with quantitative evaluations. At the same time, the results of the qualitative surveys were included to extend the findings, show differentiations, and explain the background of the distributions.

With regard to the validity and transferability of the standardised survey findings, it is important to point out that they are the results of individual case studies. Although the aim was to conduct comprehensive and representative surveys in all case studies, all three communities consist of a relatively small number of residents (34–65 households), who in turn did not all participate in the surveys (response rate of approximately 60%).

The empirical data generated in the WohnMobil project provides the only data source of this paper. No further (social) empirical data were used in this paper.

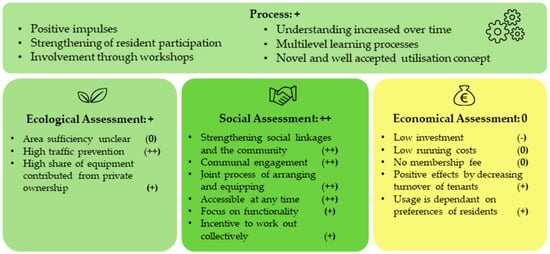

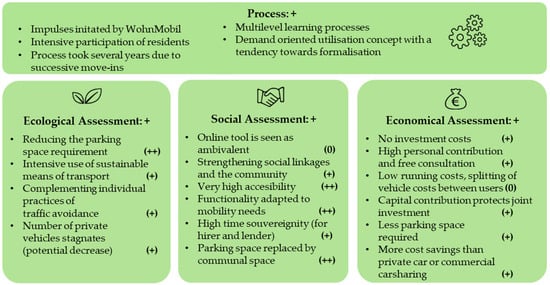

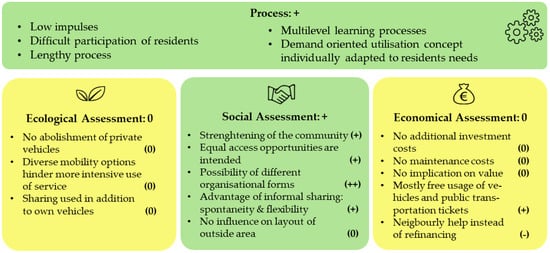

2.3.3. Content Analysis and Scaled Assessment

The survey and evaluation of the empirical steps was followed by an assessment of the sustainability impacts. For this purpose, an analysis concept was developed to relate the empirical results to the previously developed sustainability indicators and criteria. First of all, the qualitative and quantitative statements from the empirical data were interpreted, structured, and assigned to the respective sustainability criteria. The next step was to derive statements on development trends, i.e., the extent to which services can trigger sustainability effects from an ecological, social, and economic perspective. Only after the results had been assigned to the evaluation categories could evaluative statements on the ecological, social, and economic sustainability impacts of the services be made. The impact assessment thus began by taking up these statements and conclusions and condensing them for each sustainability criterion—separated according to RWL and service—before assigning them a rating for their sustainability impact. To support this, the following five-tier scale was used to assess the sustainability impact of residential services.

Based on the evaluation framework (Table 2), it was possible to link the results from our empirical study to the sustainability indicators. The next step was to assess the extent to which the services exert sustainability effects in ecological, social, and economic terms. Using the categorisation scheme (Table 3), each indicator could then be assessed separately. Subsequently, the results per service were aggregated at the level of the sustainability dimensions. The score for each sustainability dimension was derived from the average value of its indicators. This procedure enabled an overall evaluation for each service developed in the co-creation process compounded of the three sustainability dimensions. The composition of the detailed evaluation scores for each sustainability indicator allowed a deeper examination of the services established by the three RWLs.

Table 3.

Categorisation scheme to assess the sustainability impact.

5. Conclusions

This paper presented the socio-ecological evaluation of three examples of neighbourhood mobility concepts and collaborative uses of space and land in co-housing initiatives that were developed in a co-design between residents and scientists in an RWL. The evaluation used social-empirical methods and secondary analyses. The results show the high sustainability potential of neighbourhood concepts: they enable residents to meet their mobility and housing needs, to use fewer vehicles through shared use, reduce the number of journeys, and to change their choice of transport mode.

However, developing and promoting shared community services has shown to be very pre-conditional and inhibited by factors such as existing planning law, planning/building processes, and actor constellations. This has to be considered by housing companies and initiatives, but as well as—or even more so—by municipal planning administrations, private planning consultancies, and in planning legislation, if the potentials of such services is to be fully exploited.

For a final conclusion, the authors emphasise that urban and transport planning as well as housing companies are called upon to better integrate these insights in planning and developing practices as to systematically use the potential to change, re-design, and re-constellate practices and patterns that affect mobility related behaviour. Bottom-up approaches have the potential to change practices and patterns both for self-organized and institutionally initiated participation processes. In summary, our recommendations for these key actors and their role are as follows:

Housing companies and associations act as developers or redevelopment agencies in urban development and are used to provide housing related services. They are thus key actors in sustainability transformations. By developing, establishing, and operating shared community services, they contribute to sustainability goals and thereby achieve better resident loyalty and satisfaction as well as image enhancement. Housing companies can play an important role in strengthening bottom-up initiatives. They can encourage and support residents to participate in the development and organisation of shared community services in order to create solutions that are more user oriented and better suited to the residents’ needs.

Municipalities are actors in land allocation and transportation planning. Their practices should be strongly oriented toward the common good. To ensure that innovative concepts can be implemented in a time-effective framework, land or leases should not be awarded on the basis of the best-price principle but by means of so-called concept awarding, as already practiced by some cities in Germany. This instrument could also be used in larger redevelopments and urban renewal processes. In addition, local regulations, such as parking space regulation (German Stellplatzverordnung), should better promote sustainability aspects and allow for new concepts that target lower car ownership rates and must not act as inhibiting factors for more sustainable concepts.

Furthermore, municipalities play a key role as actors that can drive integrated settlement and transport development: mixed-use, small-scale built-spatial structures are considered a core element of planning that avoids traffic and enhances quality of life [22]. This applies not only to new developments but also to the redevelopment of existing areas. The municipalities and the commissioned planners therefore should acknowledge that they have a core task and a core competence to reconfigure housing and mobility practices sustainably.

In addition, municipalities can engage in knowledge transfer to support and promote sustainability transformations and provide targeted advice to redevelopment and construction clients. In this way, concept awarding processes and successful implementation can be well linked. This can be done through funding strategies for investments in shared community services or, as is emerging in some places, through support structures for participatory planning and collaborative forms of living.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D. and I.S.; methodology, J.D., M.W.; validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, M.W., J.D., I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.-M.J., J.D.; writing—review and editing, J.D., I.S., M.W., J.-M.J.; visualization, J.D., J.-M.J.; supervision, I.S.; project administration, J.D.; funding acquisition, J.D., I.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) on the thematic priority “Sustainable management”, funding code 01UT1224A-C.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical review and approval was done in the project WohnMobil in 2016 and 2018 by a board comparable to an Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The main data sources were data collected during the research project at actors and residents of the co-housing initiatives. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data due to anonymity reasons. The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all involved residents of the research project WohnMobil. Without their “new living” we wouldn’t have been able to investigate the transformation processes. We thank all research and practice partners in this exiting project and our funding agency BMBF and DLR for making the project possible. In addition we wish to thank Maxine Demharter for editing our English and eliminating our mistakes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Czischke, D. Collaborative housing and housing providers: Towards an analytical framework of multi-stakeholder collaboration in housing co-production. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2018, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, D. Hamburg: Housing movements and local government. In Contemporary Co-Housing in Europe: Towards Sustainable Cities? Hagbert, P., Larsen, H.G., Thörn, H., Wasshede, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen, S.; Cohen, A.; Chan, N.; Bansal, A. Sharing strategies: Carsharing, shared micromobility (bikesharing and scooter sharing), transportation network companies, microtransit, and other innovative mobility modes. In Transportation, Land Use, and Environmental Planning; Deakin, E., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 237–262. [Google Scholar]

- Boyko, C.; Clune, S.; Cooper, R.; Coulton, C.; Dunn, N.; Pollastri, S.; Leach, J.; Bouch, C.; Cavada, M.; de Laurentiis, V.; et al. How Sharing Can Contribute to More Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2017, 9, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonuschat, H.; Scharp, M. Sustainable Home Services in Germany: An Overview on Preconditions, Frameworks and Offers; Werkstattbericht (72); IZT—Institut für Zukunftsstudien und Technologiebewertung: Berlin, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hohm, D.; Jonuschat, H.; Scharp, M.; Scheer, D.; Scholl, G. Innovative Dienstleistungen‚ Rund um das Wohnen’ Professionell Entwickeln. Service Engineering in der Wohnungswirtschaft. Leitfaden; GdW Bundesverband deutscher Wohnungsunternehmen e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, M. Quantifying the environmental impact of ecovillages and co-housing communities: A systematic literature review. Local Environ. 2017, 22, 1358–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacke, U.; Müller, K.; Dütschke, E. Cohousing - social impacts and major implementation challenges. GAIA—Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2019, 28, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäfer, M.; Hielscher, S.; Haas, W.; Hausknost, D.; Leitner, M.; Kunze, I.; Mandl, S. Facilitating Low-Carbon Living? A Comparison of Intervention Measures in Different Community-Based Initiatives. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagbert, P. Co-housing as a socio-ecologically sustainable alternative? In Contemporary Co-Housing in Europe: Towards Sustainable Cities? Hagbert, P., Larsen, H.G., Thörn, H., Wasshede, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Anke, J.; Francke, A.; Schaefer, L.-M.; Petzoldt, T. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 on the mobility behaviour in Germany. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2021, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.S.; Skillman, S.W. Mobility Changes in Response to COVID-19. arxiv 2020, arXiv:2003.14228. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccorsi, G.; Pierri, F.; Cinelli, M.; Flori, A.; Galeazzi, A.; Porcelli, F.; Schmidt, A.L.; Valensise, C.M.; Scala, A.; Quattrociocchi, W.; et al. Economic and social consequences of human mobility restrictions under COVID-19. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 15530–15535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buheji, M. Sharing Economy and Communities Attitudes after COVID-19 Pandemic—Review of Possible Socio-Economic Opportunities. Am. J. Econ. 2020, 10, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marckmann, B.; Gram-Hanssen, K.; Christensen, T.H. Sustainable Living and Co-Housing: Evidence from a Case Study of Eco-Villages. Built Environ. 2012, 38, 413–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J. Sun, surf and sustainable housing—Cohousing, the Californian experience. Int. Plan. Stud. 2005, 10, 145–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moos, M.; Whitfield, J.; Johnson, L.C.; Andrey, J. Does Design Matter? The Ecological Footprint as a Planning Tool at the Local Level. J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 195–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraldsson, H.V.; Ranhagen, U.; Sverdrup, H. Is Eco-living more Sustainable than Conventional Living? Comparing Sustainability Performances between Two Townships in Southern Sweden. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2001, 44, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pissourios, I.A. Top-down and Bottom-up Urban and Regional Planning: Towards a Framework for the Use of Planning Standards. Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2014, 21, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healey, P. Collaborative Planning. Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Tummers, L. Understanding co-housing from a planning perspective: Why and how? Urban Res. Pract. 2015, 8, 64–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, C. The 15 Minutes-City: For a New Chrono-Urbanism! Available online: http://www.moreno-web.net/the-15-minutes-city-for-a-new-chrono-urbanism-pr-carlos-moreno/ (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Schneidewind, U.; Scheck, H. Die Stadt als “Reallabor” für Systeminnovationen. In Soziale Innovation und Nachhaltigkeit: Perspektiven Sozialen Wandels; Rückert-John, J., Ed.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2013; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Deffner, J. Wohnbegleitende Dienstleistungen in Gemeinschaftlichen Wohnformen: Systematisierung, Fallbeispiele und erste Überlegungen zur Verallgemeinerung. Werkstattbericht. 2017. Available online: http://www.wohnmobil-projekt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Geschaeftsmodelle_Werkstattbericht_Rubik_Hummel.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Rubik, F.; Hummel, T. Überblick über Geschäftsmodelle und Anwendung auf Wohnungsunternehmen und Wohninitiativen. Werkstattbericht. 2016. Available online: http://www.wohnmobil-projekt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/WohnMobil_Broschuere.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Schönau, M.; Kasten, P.; Birzle-Harder, B.; Kurzrock, B.-M.; Rubik, F.; Deffner, J. Nachhaltigkeitswirkungen Wohnbegleitender Dienstleistungen in Gemeinschaftlichen Wohnformen. Analyse von Drei Praxisbeispielen Gemeinschaftlicher Flächennutzung und Mobilitätsangebote. Werkstattbericht. Available online: http://www.wohnmobil-projekt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/Nachhaltigkeitswirkungen_Werkstattbericht.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Deffner, J.; Kasten, P.; Rubik, F.; Schönau, M.; Stieß, I. Wohnbegleitende Dienstleistungen. Nachhaltiges Wohnen durch Innovative Gemeinschaftliche Angebote Fördern. 2018. Available online: http://www.wohnmobil-projekt.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Downloads/WohnMobil_Broschuere.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2020).

- Selke, S. Gesellschaft als Labor. 2018. Available online: http://blog.soziologie.de/2013/11/gesellschaft-als-labor/#more-3061 (accessed on 4 February 2021).

- Jahn, T.; Keil, F. Reallabore im Kontext transdisziplinärer Forschung. GAIA—Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2016, 25, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäpke, N.; Stelzer, F.; Bergmann, M.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Wanner, M.; Caniglia, G.; Lang, D.J. Reallabore im Kontext Transformativer Forschung: Ansatzpunkte zur Konzeption und Einbettung in den Internationalen Foschungsstand; IETSR Discussion papers in Transdisciplinary Sustainability Research; Leuphana University of Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ukowitz, M. Transdisziplinäre Forschung in Reallaboren: Ein Plädoyer für Einheit in der Vielfalt. GAIA—Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2017, 26, 9–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidewind, U.; Singer-Brodowski, M. Transformative Wissenschaft. Klimawandel im Deutschen Wissenschafts- und Hochschulsystem, 2nd ed.; Metropolis Verlag: Marburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Beecroft, R.; Parodi, O. Reallabore als Orte der Nachhaltigkeitsforschung und Transformation. Einführung in den Schwerpunkt. Technikfolgenabschätzung—Theorie und Praxis 2016, 25, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes Nieto, J.E.; Rigueiro, C.; Da Simões Silva, L.; Murtinho, V. Urban Integrated Sustainable Assessment Methodology for Existing Neighborhoods (UISA fEN), a New Approach for Promoting Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 564–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).