Abstract

The construction of Nandoni Dam started in 1998 and was completed in 2005. The main promises made to affected communities living around the dam were that they would receive water and there would be economic opportunities for them. Water-based recreation and ecotourism at the dam were seen as the main vehicle for economic opportunities; it was envisaged that these would not only create local employment but would also improve local lives and livelihoods. The paper focuses on the rhetoric of economic opportunities and poverty alleviation and the perceived reasoning that the creation of the dam is the way forward for rural development. To achieve this aim, the study combined qualitative and quantitative methods. The claim that the creation of the dam would result in increased economic benefits for local residents is firmly rooted in business interests. The adoption of business or economic approach by government through the Department of Water and Sanitation has created conditions for segregation within society. The study also found that the creation of Nandoni Dam benefits those who are rich and elite, government officials, and politicians at the expense of the local population, and this has long-lasting detrimental impacts on their lives and livelihoods. The study concludes by giving an overview of lessons learned from the case study and suggestions for best practice that can enhance the long-term sustainability of dam projects.

1. Introduction

The construction of Nandoni Dam started in 1998 and was completed in 2005. The construction of Nandoni Dam was premised by the desire of authorities to upgrade water resource management. This was paired with the wish to improve economic development through water-based recreation and tourism—a resource that had not yet been exploited in the region [1,2]. In other words, expectations were built amongst local communities that economic development would result from recreational utilization of the dam. It was anticipated that water-related recreation and ecotourism development in the study area would not only create employment for local communities but also improve their lives and livelihoods. In addition, the dam was also expected to act as a catalyst for new developments and initiatives in the area to alleviate poverty [1,2]. As a result, the Mulenzhe Development Trust—a community project—was set up as a vehicle for benefits to transfer to the Mulenzhe community comprising the villages of Thondoni, Dovheni, Khakhanwa, Dididi, Tshitomboni, Tambaulate, and Tovhowani/Rotondwa. The trust was conceived in 1999 and was registered with the Master of the High Court during 2001 in terms of its Trust Deed in line with the Trust Property Control Act 57 of 1988. Its vision is to empower the beneficiaries (communities), thereby contributing to a better life for all, and the chairperson of the trust is the chief of Mulenzhe.

The promises made to local communities not only appeared on the development plan but were made public through various platforms by the government through the Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) (at that time known as the Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF)), traditional leaders, and local municipalities. The promises made by various authorities were more appealing to the majority of rural communities who had no access to neither clean water nor jobs. Although the physical displacement of people is not the focus of this study, it should be noted that this had been a prerequisite for construction to proceed. This displacement took place based on the understanding that social and economic benefits would transpire. This is in line with South Africa’s commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals of eradicating poverty and hunger, reducing inequalities and exclusion, and providing employment opportunities to communities, thereby promoting local economic development. The aim of this study is to explore the rhetoric of economic opportunities and poverty alleviation and the perceived reasoning that the creation of a dam is the way forward for rural development. The claim that the creation of a dam will result in increased economic benefits for local residents is firmly rooted in a business model. Unlike studies that have either used a qualitative or a quantitative approach, this study combined qualitative and quantitative methods to argue that the adoption of a business or economic approach by the government benefits the rich and elite, government officials, and politicians at the expense of the local population. Integrating qualitative and quantitative data is important to gain deeper insight into the claim that the creation of a dam is the way forward for economic opportunities and poverty alleviation for local communities. The study contributes to the debate on dams and local communities by highlighting not only how the transformation of rural space through the creation of a dam has disempowered local communities as with other studies, but also how the adoption of a business model has created conditions for inequality within these changing social spaces. This has long-lasting detrimental impacts on the lives and livelihoods of local communities.

2. Literature Review

The construction of dams has a long history dating back to the third millennium B.C., when the first great civilizations evolved on major rivers such as the Tigris–Euphrates, the Nile, and the Indus [3]. By 1949, about 5000 large dams had been constructed, and by the end of the 20th century, there were 45,000 large dams in over 150 countries [4]. More dams continue to be constructed in the 21st century in both developed and developing countries. From early times, dams were constructed to control floods, transport water, and supply water for domestic and irrigation purposes [4,5]. Dams have also been built to produce power and electricity since the industrial revolution [3,6,7]. Electricity production from dams has become significant in the contemporary world. According to Kirchherr and Charles [8], it is estimated that at least 3700 hydropower dams (>1 MW) are either planned or are already under construction. Zarfl et al. [6] predict that this will increase global hydropower production by 73%. Other important benefits associated with the construction of dams includes increased land value and the development of fisheries [3,9]. Wiejaczka et al. [10] noted that local communities are happy to live near dams when they recognize tangible social benefits. In recent years, strong emphasis has been placed on the economic opportunities that dam construction allegedly generates, especially for neighbouring communities [7,11,12]. In particular, it has often been claimed over the past two decades, for e.g., by the World Commission on Dams [4], that water-related industries associated with dams create employment for local communities and improve their lives and livelihoods. This study explores the rhetoric of economic opportunities and poverty alleviation and the perceived reasoning that the creation of a dam is the way forward for rural development.

A growing body of literature has demonstrated that the construction of dams can also be highly problematic owing to its environmental and socioeconomic impacts [8,12,13,14,15,16]. A critical question is whether the aims of dam construction and community development can be fulfilled under a single banner. Critiques have focused on the negative consequences of dam construction such as the displacement of people [14,17,18,19]; in the process, they have lost access to the land and its resources [20,21]. The literature demonstrates the global pattern of dam construction having displaced local populations including in Mozambique [22], Iran [11], Indonesia [14,19], China [23,24], India [25], Mexico, the United States of America [13], and Japan [17]. Scudder [13] estimated that out of more than 200 million people who were displaced by infrastructure development, 80 million (40%) were displaced due to dam construction. This has had devastating effects on their lives and livelihoods [13]. The construction of dams has also been criticized because it results in the physical transformation of rivers, altering their natural flow [12], ecosystem destruction [4,15,16], and the loss of cultural heritage such as archaeological remains [26]. In addition, dams have been criticized for the lack of benefits accruing to residents and failure in fostering regional development [27].

3. Methods

3.1. Study Area

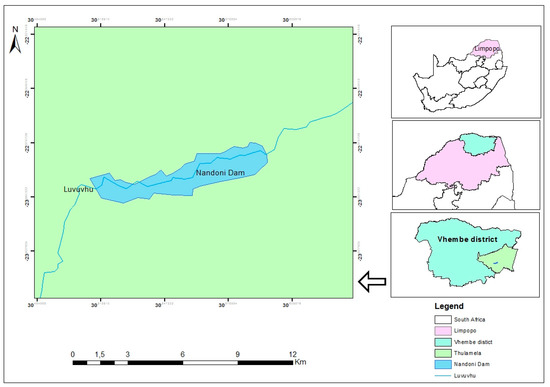

The study area is Nandoni Dam (22°56′45″ S and 30°20′07″ E), which was constructed over the period 1998–2005. The dam falls under Ward 18 and 19 of Collins Chabane Local Municipality and Wards 19, 20, 26, 36, and 41 of Thulamela Local Municipality in the Vhembe District Municipality in Limpopo Province of South Africa (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location of Nandoni Dam falling under the Vhembe region in Limpopo Province of South Africa.

It lies 16 km southeast of the town of Thohoyandou. The Nandoni Dam is an earth-fill and concrete–type dam, which impounds the Luvuvhu River [2]; its catchment area extends from near Louis Trichardt in the west to the Kruger National Park in the east. The dam is substantial, covering 1650 hectares and with a capacity of 166,200,000 m3. According to Mokgoebo et al. [15], the dam has a surface area of 1570 ha. Constructed on state-owned land (Department of Rural Development and Land Reform), the dam is administered by three traditional authority territorial councils. The councils are responsible for the allocation of parcels of land for specific uses by individuals or organizations. The northern shore falls under the Mphaphuli Territorial Council led by Chief Mphaphuli; the southern shore under the Mulenzhe Territorial Council, led by Chief Ramovha; while the western shore falls under the Tshivhase Territorial Council, led by Chief Tshivhase.

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The study was based on both qualitative and quantitative methods. The permission to conduct this research was obtained from the Mulenzhe Tribal Authority. After getting permission from the tribal authority, semi-structured interviews were conducted with key, selected informants including officials from tribal authorities, business owners and managers, committee members dealing with relocation of community members prior to construction, as well as individuals who have plots alongside the dam. A permission letter signed by the official from the tribal authority and an identification card with my affiliation with my university helped to introduce me to key stakeholders in the study area. Respondents were asked their permission before they were interviewed. Participants were briefed about the purpose and scope of the research at the start of both the semi-structured interviews as well as the questionnaires; they were also informed that participation in the research was voluntary and that their individual identities would be kept confidential. They were further notified that they could terminate their participation at any time should they feel that they no longer want to participate. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to find out how the land alongside the dam was allocated, to understand the water-based recreation and tourism activities along the dam and its impacts on communities. The informants who were interviewed for this study were selected using a non-probabilistic purposive sampling approach. As Onwuegbuzie and Leech [28] have noted, the logic and power of purposeful sampling lie in selecting information-rich cases that provide the greatest insight into the research aim and objectives. Respondents were selected until a sample saturation level of 17 was reached [29]. At this point, respondents were giving similar responses regarding allocation of land along the dam and water-based recreation and tourism development and their respective impacts on locals.

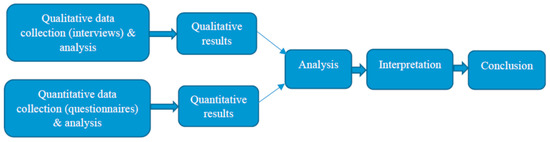

Data obtained from interviews were analysed using thematic analysis. This independent qualitative descriptive approach is defined as “a method for identifying, analysing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” [30]. The respective interview notes were read in the evening in order to gain understanding of the data. The interview excerpts were tabulated on Microsoft Excel, and key phrases and concepts that have some connection with each other were highlighted in different colours according to categories. Following Castleberry and Nolen [31], the data were then classified into groups identified by different codes, and this helped to gain a summary of the main points and common meanings that were repeated throughout the data. The codes were collated into patterns and after reviewing and refining patterns, two major themes emerged, namely, allocation of land and water-based recreation and tourism development around Nandoni Dam and their respective impacts on locals discussed further below (Figure 2). In some cases, episodes were narrated in the write-up, using the exact words of the respondents. This was done to provide a rich description of the situation for the reader.

Figure 2.

Summary of the whole research process.

Quantitative data were collected through an interview-administered questionnaire conducted with community members in the local villages of Mulenzhe and Dididi. The questionnaire combined both closed- and open-ended questions, the latter primarily used to allow respondents to express themselves in their own words. This is in line with White et al. [32], who argue that incorporating well-designed open questions may provide data of equivalent precision to closed-format ones. The questionnaires were designed to cover the socioeconomic characteristics, attitudes of local people towards the dam, benefits of dam construction, and the impact of water-based recreation and tourism development on the lives and livelihoods of local people (Appendix A). This was in line with the research aim stated in the Introduction (Section 1). They were written in English and then translated into Tshivenda (the local language in which the interviews were conducted) by the bilingual author. The questionnaires were administered to the household head (whoever assumed responsibility for the household, male or female) or any adult member of the household aged more than 18 years [33]. It was assumed that they would be likely to have strong perceptions about any impacts of the dam construction and would, thus, be able to provide relevant information.

The questionnaires were administered until 220 households had been covered (110 in each village). The total response time averaged 30 min per questionnaire. In line with Kothari [34], questionnaires had been pretested on a sample of 20 people from the rural village adjacent to the study area. This was done to ensure that the questions were clear and unambiguous. The pretesting showed it was not necessary to do any rephrasing or reorganizing of the questionnaire. Households that took part in the survey were selected through a systematic random sampling approach. The justification behind using systematic random sampling was to reduce the potential for human bias in the selection of households [35]. The Tshivenda feedback received was translated into English by the author ahead of analysis of the results. The data collected were tabulated using Microsoft Office Excel. The analysis of the data used Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20 for Windows (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the questionnaire response dataset. The interrelationships between the variables were examined using chi-square (X2) tests for goodness-of-fit. Differences were considered to be significant at 1% significance level. The results from questionnaires (open-ended questions) were analysed with the results from interviews after which interpretations (both qualitative and qualitative) were done (Figure 2). Similarly, episodes from open-ended questions (questionnaire) were recounted in the write-up, using the exact words of the respondents to provide a vivid description of the situation for the reader.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Demography

Seventeen semi-structured key informant interviews were conducted, all of which were with married men above 40 years (Respondents interviewed including officials from tribal authorities, business owners, committee members dealing with the relocation of community members prior to construction, as well as individuals who have plots alongside the dam were mostly men. As a result, men who were married and above 40 years became the main respondents.) (mean = 46, standard deviation = 3.48). Sixteen of the interviewees were employed, and one was a pensioner. The villages of Mulenzhe and Dididi were selected as the location for administering interview questionnaires (110 respectively) because they were the most affected by the construction of the dam. The number of people per household in both villages ranged from two to 15 (mean = 4.8 standard deviation = 2.43). The socioeconomic characteristics of respondents such as gender, age, marital status, education, and employment are represented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic profile of the respondents (n = 220) in Nandoni Dam falling under the Vhembe region in Limpopo Province of South Africa.

The study found that 43.64% (n = 96) had an income of <R1000, 33.18% (n = 73) had income of R1000–R2000, whereas the remaining 23.18% (n = 51) had an income of >R2000. The main sources of income included child grants, pension, and professional jobs such as nursing, policing, and teaching. Unemployment rates were high in both villages, with only 19.1% employed. This figure may be an underestimation of employment in general, as those who had formal employment were unlikely to be at home during the administration of questionnaires.

4.2. Allocation of Land Adjacent to the Dam

As we have noted, the land around the dam falls under Mulenzhe, Mphaphuli, and Tshivhase Territorial Councils. Although the land is state-owned, it is administered by various chiefs, who hold the decision-making power to grant permission for a range of land uses. After the construction of the dam in 2005, the chiefs of various tribal authorities allocated residential plots around the dam. The study found that the tribal offices were charging between R10,000 ($684.43) and R100,000 ($6823.74) (particularly Mulenzhe Tribal Authority) for a prime piece of residential area along the dam, depending on the size of the plot. The fact that the tribal authorities were charging exorbitant amounts for residential plots was corroborated by the City Press Newspaper [36]. These prices were too high for the mostly unemployed rural communities, who rely on child and social grants. The residential plots were one hectare and above in size, with sale conditional on the purchaser developing the plot within two years. The analysis of interview material suggests that the residential plots along the shore of the dam were sold only to well-known politicians, senior government officials, and rich people, none of whom were local residents. In other words, local people were sidelined in the allocation of residential plots along the dam, despite the promises made before the construction of the dam noted above [1,2]. Thus, the dam’s serene banks dotted with well-appointed double-storey houses are perceived by the local communities interviewed as a symbol of segregation, inequality, and injustice.

A number of plots along the shores of the dam were sold for development as recreational businesses. In line with the resource management plan of Nandoni Dam [1,2], this was done to promote water-based recreation and ecotourism development. Whilst business premises within the Mulenzhe Tribal Authority area were awarded 99-year leases, on the Mphaphuli Tribal Authority land, business owners successfully bought the land from the tribal authority. Leaseholders pay annual royalty fees; this study also revealed that some business owners were paying about R4000 ($262.10) with an annual increase of 10%. It is important to note that all the money paid for residential plots and for leasing business land along the dam on the Mulenzhe Tribal Authority was paid into the Mulenzhe Development Trust. The Mphaphuli Tribal Office was also charging exorbitant amounts for a prime business plot around the dam, depending on the size. Analysis of evidence gathered during fieldwork suggests that some businesspeople had gone to the lengths of buying gifts (bribes) in the form of cars for the chief to secure business plots along the dam. Furthermore, business plots were allocated only to outside businesspeople, politicians, and senior government officials rather than to residents. In other words, local businesspeople and local communities were not afforded an opportunity to buy a piece of land along the dam even though they had been intended as the main beneficiaries of the area. Without access to, and use of, the land along the dam, they are unable to benefit economically. As a result, the creation of the dam, which was supposed to be the window of opportunity for local people, has been turned into a closed door of continued exclusion. In a similar study, Braun and McLees [37] also found that the construction of the Katse Dam in Lesotho privileged external people and elite interests over the local Basotho. The growing inequality and the pattern of inclusion and exclusion at Nandoni Dam can best be explained by influence and power [38,39,40] that people have in a society.

Whilst the powerful, privileged minority have secured space and property rights along the dam and are able to benefit economically, this is sadly not the case for the powerless and disadvantaged majority (local communities). Displacement has been combined with loss of livelihoods and access to resources as local communities can no longer cultivate in the area, following the inundation of their land. Similarly, the areas of pasture for breeding livestock have significantly decreased because of the dam. Material gathered during interviews indicates that local communities’ livestock are unable to access drinking water at the dam because landowners along the dam do not allow livestock to pass through their property. As a result, livestock, particularly cattle, are, inter alia, reported to break taps in villages in search of water. The results of this study are in line with the findings of Manyanhaire et al. [41] and Chen [42], who found that local communities in Zimunya Communal Lands in Zimbabwe and Yunnan China, respectively, faced limitations on access to their land, compared to the situation before dam construction. Such economic impacts on their lives and livelihoods are long lasting.

4.3. Water-Based Recreation and Tourism Development around Nandoni

The study found that Nandoni Dam has indeed been transformed into a water-based recreation and tourism destination area, as in the case of Tehri Dam in India [10] and Katse Dam in Lesotho [37]. Various places around the Nandoni Dam have been developed for lodging and recreational purposes. The most popular places situated on the shores of the dam are the Nandoni Villa, Royal Gardens, Nandoni Fish Eagle Lodge, Nandoni Waterfront, Kalahari Waterfront, Lira Boutique Lodge and Spa, Kingsgate Nandoni Dam, and Mulenzhe Development Trust. Most of these places have websites and are marketed internationally. It is important to note that all these destinations are privately owned whereas the Mulenzhe Development Trust is the only community development project.

The year-round warm weather at Nandoni Dam is an added attraction, and visitors are able to enjoy the area as a prestigious outdoor wedding venue and host music festivals, corporate functions, and private celebrations. Picnic areas and various viewing points provide visitors with breathtaking views of the water and surrounding areas. Over the past eight years, the Royal Gardens Leisure Park has become the home of the Phalaphala FM Royal Heritage Festival annual music event attended by 15,000–21,000 people. This festival, held during heritage month (September), has become the most important event at the dam. Day visitors are also allowed access on payment of a gate entrance fee of R50 ($3.31) irrespective of whether you are a local resident or not; this fee is unaffordable for local communities as articulated by one informant: “Most of us cannot afford to pay the gate entrance fee because we rely on a child grant. It is too much for us and nobody wants to employ us”. At weekends, fishing enthusiasts and speedboat lovers frequent the dam whereas local communities remain outside the perimeter fence, as most of them cannot afford to pay gate fees and boat tours in the dam.

This has reinforced the divide, whereby the dam has become the playground for the rich while local communities remain economically disempowered. This is in line with studies conducted in the Jordan Valley in Jordan [25], Lesotho [37], Ghana [43], and China [44] that also found that the construction of dams neither benefits local residents nor fosters rural empowerment. As a result, the reorganization of space through the creation of large-scale dams not only undermines the local communities but also has devastating effects on their lives and livelihoods. This is because remote spaces are expropriated (in some cases without compensation) to construct dams, and locals lose access to and ownership of their lands and resources. Thus, the construction of the dam serves to restructure ownership and reorganize resources such that local communities lose ownership of their lands for the projects of the state (dam) and for the profits of well-connected private landowners who have tourism businesses around the dam [37].

Nandoni Dam was founded on the logic that water-based recreation and ecotourism would not only be the main vehicle for development and economic opportunities but would also create local employment and improve local lives and livelihoods. It was anticipated that this would alleviate poverty in the surrounding villages. However, the founding logic constitutes a powerful paradox because local communities remain on the edge. The emphasis on economic opportunities at Nandoni Dam legitimizes denying access to local communities because as Bologna and Spierenburg [45] have noted, creating a sense of exclusivity has a higher value for ecotourism operations and is the most effective way of generating sufficient income for private landowners (external) to realize profit. The construction of the Nandoni Dam and subsequent tourism development reflect the priorities of capital and development in privileging the external, revenue-generating potential of space over the subsistence livelihoods of local residents [37].

4.4. Window of Economic Opportunity or Door of Exclusion

Generally, it was agreed among business owners and managers that water-based recreation and tourism at the dam is seasonal. It was indicated that the area is busiest during Easter, June/July school holidays, September (Heritage month), and December holidays. It was further observed that weekends can be busy, whereas the area remains visitor-free during the week. Feedback from interviews with business owners and managers revealed that even though they are not busy throughout the year, their dam-side businesses have contributed to job creation in the area. For instance, two such business owners (identities withheld) have permanently employed three and four people each. It was revealed that jobs such as boat operators, security guards, receptionists, cleaners, administrators, gardeners, and managers have been created. However, 92.27% (significant at 1%) of the local community members interviewed indicated that of the few jobs that have been created, a high proportion of those employed are not from local villages. Rather, the employees generally are either related to business owners or were employed by them prior to the owners moving to the area. As a result, instead of empowering local communities through jobs, local communities were of the view that they are being disempowered. Most of the local community members interviewed thus indicated that fishing at the dam has become their main sources of income. This is witnessed as you drive on the R524 and the D3756 roads linking Thohoyandou and Malamulele, where local communities sell raw and grilled fish along the roadside.

When asked about the benefits from water-based recreation and tourism at Nandoni Dam, the majority of respondents (95%; n = 209) indicated that their families do not benefit from the recreational and tourism activities happening at the dam; the results are statistically significant at 1%. They do not have a stake in the recreational activities, and despite being neighbours of the dam, they are expected to pay full price for gate entrance fees when there are music festivals or any other events in the area. As a result, they were of the view that there is no benefit and their living standards remain the same as before the dam was constructed. The remaining 5% who indicated that they benefit from water-based recreation and tourism have either worked, are working, or have relatives who are working at the dam. In all, 98.18% of respondents (significant at 1%) reported that water-based recreation and tourism are only benefiting rich people who have businesses alongside the dam whereas the majority of local community members are largely dependent on child and social grants, fishing, and subsistence agriculture. In other words, a higher proportion of people continue to live in poverty, as they are unemployed. When asked whether some of the profit made from water-based recreation and tourism at the dam is used to improve local development, all respondents said “no”. It was pointed out that roads in the local communities are not tarred and they are in bad condition. It was further indicated that the taps in the villages remain dry and no effort is made either by local businesspeople or government to help improve the situation. Thus, local communities rely on water from boreholes, and at times, they use raw water from the dam for domestic purposes. This is despite the intention that the primary aim of building the dam was to supply water to communities [1,2]. Fieldwork evidence demonstrates that fresh water from Nandoni Dam is enjoyed in Thohoyandou—a town 30 km away from the dam.

As noted above, Mulenzhe Development Trust was established to build a community capable of working with the government and other stakeholders for the improvement of the area and its people. The mandate of the trust, as appears on their business profile, is to ensure that (1) human and financial resources at its disposal are utilized towards the upliftment of the living standards of all beneficiaries; (2) all structures in the Mulenzhe Forum Area are capacitated to perform their duties efficiently; (3) local economic development initiatives are created, implemented, and sustained; and (4) the Mulenzhe Forum Area is developed to become a tourism destination. The Mulenzhe Territorial Council has allocated 100 ha of land for the development of the Mulenzhe Project; a portion of that land is currently used for water-based recreation and tourism whereas another portion is reserved for Nandoni Golf Estate along the dam. Nandoni Golf Estate is a mixed development consisting of 2140 residential (500–2300 square meters) and 13 commercial erven. At the time of writing this article, the stands were on sale. According to Nandoni Golf Estate website, residential stand purchase prices per square meter ranged from R700 ($47.91) to R1000 ($684.47) irrespective of whether you are a local resident or not. In order to reserve a stand, interested individuals were required to deposit a non-refundable amount of R10,000 ($684.43) [46]. These prices are too high for the mostly unemployed rural communities who rely on child and social grants to afford. This means that only businesspeople and the rich can afford the plots.

When respondents were asked whether they were familiar with the Mulenzhe Development Trust, all of them said “yes”. When asked about the benefits they get from the Mulenzhe Development Trust, all of them said they were no benefits. Whilst the project is marketed as a community project, fieldwork evidence suggests that the main beneficiary of the Mulenzhe project is the chief and his associates. Thus, all the revenues that are generated through water-based recreation, ecotourism, selling of land, and leasing of the land benefit the Royal House. As one informant commented: “Mulenzhe Development Trust is the chief’s baby. He is the main trustee, and he is not accountable to anyone. How can the chief be the main trustee if it is a community project? Nobody knows how much goes into the trust account, and no one knows how it is spent. Ever since Mulenzhe Development Trust was created, no one has benefited from it. We are afraid of him. If you question him, you may receive death threats, and nobody wants that.” As a result, 20 years after the Mulenzhe Development Trust was established, no community project has been developed to empower beneficiaries (communities), and as a result, poverty and unemployment remain a reality in the study area. Numerous other authors also note how development projects continue to marginalize and disempower local populations all over the world [37,45,47,48,49].

In fact, instead of improving the lives and livelihoods of local communities, most respondents (75%; n = 165) indicated that water-based recreation and tourism development at Nandoni Dam has contributed to the rise in crime rate in the area. The results are statistically significant at 1%. One community member from Mulenzhe commented that “Crimes such as robbery and theft usually occur when there are festivals at Nandoni Dam. Other people are beaten and stabbed when there are events at the dam.” In addition, 95% (significant at 1%) of respondents were of the view that this development has increased the level of noise in the villages surrounding the dam. As one elder from Mulenzhe village narrated: “When there are music festivals and on weekends, loud music is played during the day and throughout the night and as a result, we are unable to sleep.” It was also noted that noise makes it difficult for pupils to study, and this has serious implications on their future. A study by Mbaiwa [50] in Okavango Delta, Northwestern Botswana, and another by Gu and Wong [51] in Dachangshan Dao, Northeast China, have also identified noise pollution as another impact associated with recreation and tourism development. Overall, 71.81% of respondents (significant at 1%) were of the view that the construction of the dam has become a death trap for not only visitors but also local community members. Since the dam was constructed, 37 people have been reported to have died in its deep waters while fishing or swimming [52]. In addition, an increase in the number of local people involved in fishing has also increased the risk of drowning. This has become a source of great concern, with residents blaming the authorities for not having security measures in place that the general public should adhere to while fishing or swimming. The concern is contributed to by the increasing number of personal boats, which owners can use at will, which has increased the risk and incidence of drownings.

South Africa’s post-apartheid reintegration into global markets was heavily influenced by an international focus on sustainable development. The idea is to help combat the urgent environmental, political, and economic challenges facing the world. Some of the sustainable development goals include eradication of poverty and hunger, reducing inequality, and improving the standards of living of communities, thereby promoting local economic development [53,54]. However, rather than improving the lives and livelihoods of local communities, the construction of Nandoni Dam has created conditions for segregation within society [40,47]. This finding corroborates the results of Braun and McLees [37] in Katse Dam in Lesotho. As a result, rather than reducing inequality and improving the standards of living of the majority of local residents around the dam, the gap between the minority rich and the majority poor local communities is becoming wider. Essentially, the situation in Nandoni Dam does not help South Africa to achieve sustainable development goals.

5. Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that the Nandoni Dam’s development was premised on the objective of providing economic empowerment opportunities to the communities living around the dam. Water-based recreation and tourism at the dam were seen as the main vehicle for economic opportunities that would not only create employment for local people but also improve their lives and livelihoods. However, the study results show reality falls far short of the promises. Rather than benefiting and empowering local communities, this study has, on the contrary, shown that the development of Nandoni Dam has disregarded, disempowered, alienated, and marginalized local communities. The window of economic opportunity was supposed to have benefited local communities but was never opened to them, and thus, they remain on the periphery. For instance, local communities have been excluded from land allocated along the shore of the dam. Without this land, they are unable to benefit economically from the existence of the dam. The study also found that the few jobs that have indeed been created by new business at the dam do not benefit the majority of local communities but rather relatives of business owners and people from outside.

In addition, communities do not benefit from the Mulenzhe Development Trust, which was created as a community project. Evidence from this study suggests that the politicians, senior government officials, businesspeople, chiefs, and rich people are the main economic beneficiaries of Nandoni Dam. This can be attributed to the adoption of a business or economic approach that has successfully excluded locals and impoverished the majority while securing space, property rights, and economic benefits for the privileged minority. Thus, whilst the privileged minority can benefit economically, unfortunately this is not the case for local communities. This contradicts the claims made before the construction of the dam; rather, its development highlights how those interests are not the route, as the rhetoric falsely suggests, to a sustainable future. The Nandoni Dam case study is shaped by economic interests mainly by private individuals and not by village-based priorities as anticipated. Thus, the state facilitates the transformation of rural space (through the creation of a dam) to better meet the needs of private businesses at the expense of local population. This status quo will have long-lasting detrimental impacts on the lives and livelihoods of local communities.

The fact that most local communities are ignored when such large infrastructure projects are undertaken calls for a more meaningful social impact analysis study for dams and other construction projects affecting communities. Social impacts analysis should not be a formality as it is the case with many development projects, rather, it should be grounded in best practices that seeks to empower the local population, particularly those who are affected. In other words, social impact assessment should help to promote development strategies that address the most important concerns for the local population.

Local communities should not only be informed about the creation of development projects such as dams but should also be involved from the beginning in the planning, design, and construction (before, during, and after) of these initiatives. Importantly, authorities should ensure that all promises (social and economic benefits) made to communities before the construction of dams are fulfilled. Thus, instead of allowing politicians, senior government officials, businesspeople, chiefs, and rich people to be the main economic beneficiaries, local people should be the main beneficiary during and after the construction of dams. In addition, they should be compensated for the damage caused by the development of dams. This will help to enhance the long-term sustainability of dam projects and reduce the inequality gap.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived because this study was conducted as part of a mini-honours research project that do not require ethical review.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge all the respondents in Mulenzhe and Dididi villages who participated in this study. I also want to thank Fhatuwani Makherana, who helped with data collection in both Mulenzhe and Dididi villages. I acknowledge Mbuela Laura Mashau for helping me with the drawing of a map.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares there are no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Questionnaire Survey

My name is Dr. Ndidzulafhi Innocent Sinthumule. I am a lecturer at the University of Johannesburg under the Department of Geography, Environmental Management, and Energy Studies. The topic of my research is Window of economic opportunity or door of exclusion? Nandoni Dam and its local communities. The study focuses on the rhetoric of economic opportunities and poverty alleviation and the perceived reasoning that the creation of the dam is the way forward for rural development. The personal data collected will be processed anonymously and handled exclusively by the researcher. The data collected for this study will be exclusively used for academic purposes.

Table A1.

Demography.

Table A1.

Demography.

| Gender | Female | Male | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Village name | |||||

| Age group | 21–30 | 31–40 | 41–50 | 51–60 | >60 |

| Highest education level | Illiterate | Primary | Secondary | Tertiary | |

| Employment status | Unemployed | Employed | Self-employed | ||

| Marital status | Single | Married | Widow | ||

| Total monthly income (R) | <R1000 | R1000–R2000 | >R2000 | ||

| Sources of household income | Pension | Child grant | Formal employment | Other (specify) | |

| Number of people in the household | 0–5 | 6–10 | 11–15 | 16–20 | >20 |

Table A2.

Impacts of the Construction of the Dam and Water-Based Recreation and Tourism Development on Local Communities.

Table A2.

Impacts of the Construction of the Dam and Water-Based Recreation and Tourism Development on Local Communities.

| + | 0 | − | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The creation of Nandoni Dam has contributed to water-based recreation and tourism development. | |||

| 2. Water-based recreation and tourism development at Nandoni Dam benefits my family. | |||

| 3. I am employed or have once been employed OR a family member is employed or has once been employed in tourism enterprises around the dam. | |||

| 4. My living standard has improved because of the construction of the dam and tourism development. | |||

| 5. Some of the profit made from water-based recreation and tourism development at the dam is used to improve local development (roads, schools, etc.). | |||

| 6. Tourism development around the dam benefits the rich people, government officials, and politicians who have businesses around the dam. | |||

| 7. We now have clean water because of the construction of Nandoni Dam. | |||

| 8. I am familiar with the Mulenzhe Development Trust. | |||

| 9. The Mulenzhe Development Project is a community project. | |||

| 10. I have benefited from water-based recreation and tourism income (or any other income) made by the Mulenzhe Development Trust. | |||

| 11. Tourism development at Nandoni Dam has contributed to the rise in crime rate in my village. | |||

| 12. Tourism development has increased the level of noise in my village. | |||

| 13. The construction of the dam has contributed to the death of people. |

Appendix A.2. Open-Ended Questions

Who are mostly employed in tourism enterprises around the dam? ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What is the role of the Mulenzhe Development Trust (which is a community project) in improving the lives and livelihoods of local communities? -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

How has the construction of the dam improved the lives and livelihoods of local communities? ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What are the positive and negative impacts of tourism development in this area? ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Who are the main beneficiaries of the construction of Nandoni Dam in this area? ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Any other information regarding Nandoni Dam and tourism development that you want to share with me: --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

References

- Department of Water Affairs and Forestry. Sustainable Utilisation Plan: For the Nandoni Dam in the Thohoyandou District of the Limpopo Province; Department of Water Affairs and Forestry: Pretoria, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Water and Sanitation. Nandoni Dam Final Draft Resource Management Plan, Volume 4 of 5; Department of Water and Sanitation: Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Altinbilek, D. The role of dams in development. Water Sci. Technol. 2002, 45, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Dams. Dams and Development: A New Framework for Decision-Making; Earthscan: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, B. Role of dams in irrigation, drainage and flood control. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2002, 18, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarfl, C.; Lumsdon, A.E.; Berlekamp, J.; Tydecks, L.; Tockner, K. A global boom in hydropower dam construction. Aquat. Sci. 2015, 77, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Sardinha, I.; Ross, D. Perceived impact of the Alqueva dam on regional tourism development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2015, 12, 362–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K.J. The social impacts of dams: A new framework for scholarly analysis. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 60, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.K.; Tortajada, C. Development and large dams: A global perspective. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2001, 17, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiejaczka, Ł.; Piróg, D.; Soja, R.; Serwa, M. Community perception of the Klimkówka Reservoir in Poland. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2014, 30, 649–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosayni, A.M.; Mirakzadeh, A.A.; Lioutas, E. The Social Impacts of Dams on Rural Areas: A Case Study of Solaiman Shah Dam, Kermanshah, Iran. J. Sustain. Rural Dev. 2017, 1, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naithani, S.; Saha, A.K. Changing landscape and ecotourism development in a large dam site: A case study of Tehri dam, India. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, T. 2012. Resettlement outcomes of large dams. In Impacts of Large Dams: A Global Assessment; Tortajada, C., Altinbilek, D., Biswas, A.K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Sisinggih, D.; Wahyuni, S.; Juwono, P.T. The resettlement programme of the Wonorejo Dam project in Tulungagung, Indonesia: The perceptions of former residents. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2013, 29, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokgoebo, J.M.; Kabanda, T.A.; Gumbo, J.R. Assessment of the Riparian Vegetation Changes Downstream of Selected Dams in Vhembe District, Limpopo Province on Based on Historical Aerial Photography. Environ. Risks 2018, 65–84. [Google Scholar]

- Piróg, D.; Fidelus-Orzechowska, J.; Wiejaczka, Ł.; Łajczak, A. Hierarchy of factors affecting the social perception of dam reservoirs. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2019, 79, 106301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takesada, N. Japanese experience of involuntary resettlement: Long-term consequences of resettlement for the construction of the Ikawa Dam. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2009, 25, 419–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafsaas-Tsakos, H. Ethical implications of salvage archaeology and dam building: The clash between archaeologists and local people in Dar al-Manasir, Sudan. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2011, 11, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunardi, G.B.; Manatunge, J.; Pratiwi, F.D. Livelihood status of resettlers affected by the Saguling Dam project, 25 years after inundation. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2013, 29, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrajoula, M.T.; Al Zayed, I.S.; Elagib, N.A.; Hamdi, M.R. Hydrological, socio-economic and reservoir alterations of Er Roseires Dam in Sudan. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, F.M.; Nordensvard, J.; Saat, G.B.; Urban, F.; Siciliano, G. The Limits of Social Protection: The Case of Hydropower Dams and Indigenous Peoples’ Land. Asia Pac. Policy Stud. 2017, 4, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacman, A.F.; Isaacman, B.S. Dams, Displacement, and the Delusion of Development: Cahora Bassa and Its Legacies in Mozambique, 1965–2007; Ohio University Press: Athens, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Wolf, S.A.; Lassoie, J.P.; Dong, S. Compensation policy for displacement caused by dam construction in China: An institutional analysis. Geoforum 2013, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galipeau, B.A.; Ingman, M.; Tilt, B. Dam-induced displacement and agricultural livelihoods in China’s Mekong Basin. Hum. Ecol. 2013, 41, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asthana, V. Forced displacement: A gendered analysis of the Tehri Dam project. Econ. Political Wkly. 2012, 1, 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, N.; Curci, A.; Gatto, M.C.; Nicolini, S.; Mühl, S.; Zaina, F. A multi-scalar approach for assessing the impact of dams on the cultural heritage in the Middle East and North Africa. J. Cult. Herit. 2019, 37, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kheder, S.; Haddad, N.; Jaber, M.A.; Al-Shawabkeh, Y.; Fakhoury, L. Socio-spatial planning problems within Jordan Valley, Jordan: Obstacles to sustainable tourism development. Tourism Hospit. Plann. Dev. 2010, 7, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Leech, N.L. A call for qualitative power analyses. Qual. Quant. 2007, 41, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pidgeon, N.; Henwood, K. Grounded theory. In Handbook of Data Analysis; Hardy, M., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 625–648. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.C.; Jennings, N.V.; Renwick, A.R.; Barker, N.H. Questionnaires in ecology: A review of past use and recommendations for best practice. J. Appl. Ecol. 2005, 42, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthony, B. The dual nature of parks: Attitudes of neighbouring communities towards Kruger National Park, South Africa. Environ. Conserv. 2007, 34, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, C.R. Research Methodology: Methods and Techniques; New Age International: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- City Press. Dam the Rich. 6 April 2014. Available online: https://www.news24.com/Archives/City-Press/Dam-the-rich-20150429 (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- Braun, Y.A.; McLees, L.A. Space, ownership and inequality: Economic development and tourism in the highlands of Lesotho. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2012, 5, 435–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Resistance against conservation at the South African section of Greater Mapungubwe (trans) frontier. Afr. Spectr. 2017, 52, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, F. Power battles on South African trophy-hunting farms: Farm workers, resistance and mobility in the Karoo. JCAS 2016, 34, 165–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramutsindela, M.; Sinthumule, I. Property and difference in nature conservation. Geogr. Rev. 2017, 107, 415–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manyanhaire, I.O.; Svotwa, E.; Sango, I.; Munasirei, D. The Social Impacts of the Construction of Mpudzi Dam (2) in Zimunya Communal Lands, Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe. J. Sustain. Dev. Africa 2007, 9, 214–230. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Contradictions in dam building in Yunnan, China: Cultural impacts versus economic growth. China Rep. 2008, 44, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, J.L.; Murray, G.; Rollins, R.; Dearden, P.; Stahl, A. Differential impacts of dam construction on livelihoods in Ghana. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Lin, W.; Li, S.; Ning, Y. Social impacts of dam-induced displacement and resettlement: A comparative case study in China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bologna, S.A.; Spierenburg, M. False legitimacies: The rhetoric of economic opportunities in the expansion of conservation areas in Southern Africa. In Institutional Arrangements for Conservation, Development and Tourism in Eastern and Southern Africa; Van der Duim, R., Lamers, M., van Wijk, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 119–137. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://www.nandonigolfestate.co.za/stands.html (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Sinthumule, N.I. Unfulfilled Promises: An Exposition of Conservation in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier. Afr. Today 2017, 64, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Land Use Change and Bordering in the Greater Mapungubwe Transfrontier Conservation Area. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sinthumule, N.I. Multiple-land use practices in transfrontier conservation areas: The case of Greater Mapungubwe straddling parts of Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Bull. Geogr. Socio Econ. Ser. 2016, 34, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E. The socio-economic and environmental impacts of tourism development on the Okavango Delta, north-western Botswana. J. Arid Environ. 2003, 54, 447–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Wong, P.P. Residents’ perception of tourism impacts: A case study of homestay operators in Dachangshan Dao, North-East China. Tour. Geogr. 2006, 8, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshikhudo, E. Yet another drowning at Nandoni. Mirror Newspaper. 9 November 2018. Available online: https://www.limpopomirror.co.za/articles/news/48623/2018-11-09/yet-another-drowning-at-nandoni (accessed on 12 November 2020).

- WCED. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Kimbu, A.N.; Tichaawa, T.M. Sustainable development goals and socio-economic development through tourism in Central Africa: Myth or reality? Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2018, 23, 780–796. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).