Abstract

Marketing cooperatives are gaining popularity in the supply chain management of fruits and vegetables (F&V) due to consumers’ increasing desire to purchase cooperative products as well as producers’ willingness to reinforce their bargaining power in the market. The main purpose of this empirical study is to investigate the most important factors that motivate Greek producers to participate in marketing cooperatives, as well as those motives that discourage them. The prefecture of Imathia, in the northern part of Greece, was chosen because it is characterized by a high involvement of cooperatives, wholesalers and retailers in F&V trading. A structured questionnaire was answered by 61 producers of Imathia in 2020. The results indicate that producers recognize that they ensure safer financial transactions and direct distribution of their fresh agricultural produce via marketing cooperatives. Moreover, the study showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the motives of participation in a marketing cooperative that has bargaining power and direct distribution of fresh agricultural produce between the three categories of education level. However, producers appeared to agree that (1) the great divergence in members’ reasons for participation in a marketing cooperative and (2) the inability to take collective decisions by the general assembly are the most important disincentives for participation in marketing cooperatives.

1. Introduction

The fruit and vegetable (F&V) market is an extremely widespread, complex and global network. A number of players are involved in the F&V supply chain, such as agricultural input producers, producers, manufacturers, cooperatives, packaging enterprises, transport businesses, storage warehouses, distributors and wholesales, markets and retailers [1,2]. It is characterized by important and dynamic logistics and management systems, which respond effectively and promptly to changes that are both dictated by the market and often determined by consumer-led demands and needs [3,4].

Collective actions in agriculture (cooperatives, producer organizations, producer groups, social-cooperative enterprises) is a remarkable business model that facilitates the presence of small producers in the market [5,6,7,8]. They aim at both boosting the welfare of their members and the added value of agriculture [9,10] Some of their classical weapons in this effort are the empowerment of the bargaining power of producers, the reduction of production cost and the networking among members [11].

In Greece, there are 599 marketing cooperatives. Moreover, there are 1225 recognized Producers Organizations (POs) and 497 Producer Groups (PGs), including 737 (POs and PGs) in the Fruits and Vegetables (F&V) sector [12]. These organizations include the majority of Greek producers (123,249 F&V producers/228,288 producers or 54% of Greek producers). Therefore, it is a major sector of agriculture in Greece. A national Greek report [13] that examined data in the F&V sector from 2005 to 2011 concluded that the producers are the most vulnerable link in the F&V supply chain, while the wholesalers are the most favored.

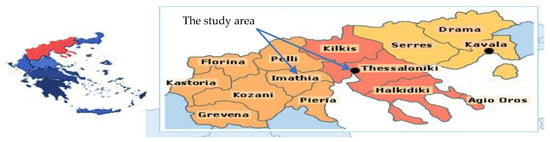

Marketing cooperatives in the F&V sector in Greece are, in general, weak, with only a few exceptions. One of these exceptions is the cooperative Venus Growers located in the prefecture of Imathia in the Northern part of Greece [14] (Figure 1). However, many producers of that area hesitate to join in cooperatives. Despite the internal and external problems that producers and cooperatives face, several research studies have proven that Greek consumers support cooperative agricultural products mostly because they want to assist Greek producers and local economies, secondly because they identify their superior quality and thirdly because they recognize cooperative’s regulatory role in the food supply chain and want to support it [15,16].

Figure 1.

The prefecture of Imathia (study area).

The type of studied cooperative is the marketing cooperative. The goals of a marketing cooperative are [17] (1) to provide the most efficient marketing outlets, (2) to expand demand for their members’ commodities, (3) to provide better coordination between production and consumption, (4) to provide more dependable market outlets, including sometimes the only remaining outlets and (5) to achieve channel leadership including vertical integration and even bargaining power for the members.

The main purpose of this empirical study is to investigate the most important factors that motivate Greek producers to participate through a marketing cooperative into a sustainable supply chain as well as those motives that discourage them. The prefecture of Imathia, in the northern part of Greece, was chosen because it is characterized by the high involvement of cooperatives, wholesalers and retailers in F&V trading. A structured questionnaire was answered by 61 producers of Imathia in 2020 and analyzed using the IBM SPSS STATISTICS program, version 25.0. As far as we know there are no relevant research studies about farmers’ motives and disincentives for participation in Greek marketing cooperatives. The largest marketing cooperative in Greece in the fruit sector (namely Venus Growers) is located in the prefecture of Imathia.

The paper is divided into six sections. After this introductory section, the theoretical framework is discussed. Then is the material and methods followed by research hypotheses, results and discussion. The final section concludes with the limitations of the research and practical implications.

2. Theoretical Framework

The value of the EU’s total agricultural output stood at slightly less than EUR 400 billion for 2019. This food system relies on a complex web of inter-related sectors that bring food to consumers. A large portion of this output gets processed into food and beverages by thousands of enterprises (280,000 in 2017, half of them making baked and farinaceous products, followed by those producing meat and meat products and by those producing beverages). In 2019, EU trade in food and drink represented 8% of all exports and 6% of all imports [18].

Big sellers of agricultural inputs, processors and distributors hold significant market shares (in some EU countries a concentration ratio of more than 80% occurs at the retail level) creating a tremendous imbalance in the bargaining power of each part of the value chain. Producers have become the most vulnerable players in the agri-food chain. Their role remains extremely important, but their contribution to the added value of the agri-food value chain continuously decreases due to their remote position in the market as well as the hyper-concentration in the upstream and downstream parts of the value chain. Producers’ low-income levels have led to a sharp decrease (25%) in the number of farms between 2006 and 2019 in Europe, while the land cultivated remains stable during the same period, indicating that large-holder farmers are concentrating cultivated areas aiming at the higher production concentration.

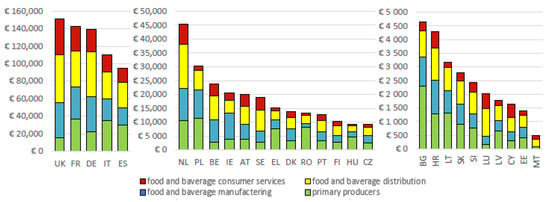

The added value of primary producers in the agri-food chain varies considerably in the EU as shown in Figure 2 There are large differences between EU countries ranging from 61% in Romania to 9% in Luxemburg. In Greece (EL), the added value of primary producers is almost 50% (the average EU level is less than 30%).

Figure 2.

The added value of agriculture in the agri-food chain (in million euros among EU countries). Source: CAP Specific Objectives explained—Brief No. 3 Farmer Position in the Value Chains. European Commission Agriculture and Rural Development.

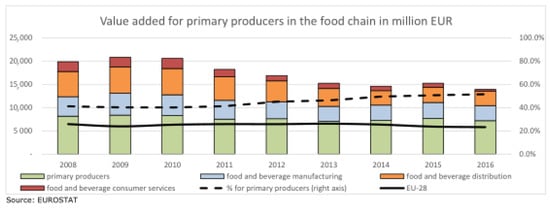

Diachronically, the contribution of primary producers to the added value of the agri-food value chain in Greece is increasing (Figure 3). More specifically, the proportion of added value in agriculture rose from 41% in 2008 to 51.5% in 2016, significantly higher than the EU average (23%). This happened not because of its rise in absolute values but mainly due to the decline in the added value of other sectors. The great recession of the Greek economy in the period 2008–2016 triggered the above-mentioned decline.

Figure 3.

Value added for primary producers in the food chain in Greece (million EUR). Source: CAP Specific Objectives explained—Brief No 3 Farmer Position in the Value Chains. European Commission Agriculture and Rural Development.

To strengthen farmers’ position in the supply chain, the CAP supports producers who wish to work together in collective actions as well as to work with manufacturers or distributors in inter-branch organizations. CAP recognizes the fundamental role of marketing cooperatives that serve as a buffer between their members and the “big economy”. However, in Greece, the rural population has risen to 3,354,612 farmers with average GDP per capita EUR 17,500. The economic size (Euro per hectare) of Greek agricultural holdings is less than EUR 4000, while the age of agricultural holders is more than 64 years (33.5% of rural population). This gloomy situation in the Greek agricultural sector can be overcome with the active participation of farmers in marketing cooperatives, providing motives mainly to young farmers [19]. Below, some of the classical factors that motivate producers to participate in marketing cooperatives as well as those factors that discourage them are briefly presented.

- i.

- Production and transaction costs:

Small producers face high fixed costs and market risks that create fluctuations in the farm income [20,21]. Additionally, they have excessive transaction costs that determine to a great extent their viability. These conditions in relation to the perishability of agricultural products make them vulnerable to the opportunistic behavior of the buyers of agricultural products [22].

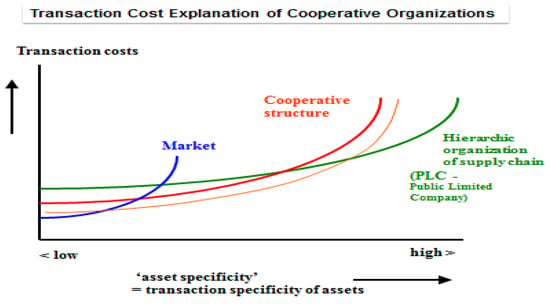

In terms of transaction cost theory, the existence of marketing cooperatives in the agricultural sector can be explained on the basis of the “contract costs” for the marketing of agricultural products. The producer has difficulties in exploring market opportunities alone. The marketing cooperative is a type of hybrid organization that operates in the market. Hybrids are non-standard modes of organization in which the partners pool strategic decision rights and some property rights (frequently substantial) while simultaneously keeping distinct ownership over key assets (they jointly develop new assets without merging together). As shown in Figure 4, markets are characterized by assets with increased transaction specificity. Hybrid organizations (such as marketing cooperatives) are more efficient than (spot) markets. In cases where transaction specificity of assets is very high, hierarchical forms of coordinating the supply chain are most efficient.

Figure 4.

Transaction cost explanation of cooperative organizations.

An important parameter for the reduction of production cost is the existence of economies of scale. “… Economies of scale in processing agricultural products have led to consolidation and oligopolistic competition. Marketing cooperatives came into being as part of the battle of farmers against these developments. Analysis of cooperative developments in various markets has led to the conclusion that the cooperative form is an especially appropriate option to cope with monopsonistic situations. In marketing cooperatives, farmers could internalize transactions in an enterprise that was user-owned and user-controlled…” [23].

- ii.

- Market conditions and bargaining power:

Markets are complex. One link in the chain can have key repercussions for preceding and succeeding links in the chain. Producers often do not have the required knowledge to negotiate with the other partners in the food market chain. Cooperatives can lessen the threat from unilateral competition that would stretch a small producer over the proverbial barrel. [23,24]. When other traders were seen as being too powerful, not transparent, discouraging cheapskates or inexpert, the cooperatives stepped in to take over the supply chain activity. This had two advantages. It united members as stronger players in the market (economies of scale) [25], and it allowed the members to capture the wholesaler’s profit margin. Therefore, marketing cooperatives facilitate producers’ access into a market. The opportunity to serve a particular market or to buy particular products means that marketing cooperatives offer significant added value to producers [26,27]. However, if members cannot meet the standards of the market, they will still fail on a personal level. On such occasions, producers should overcome these shortfalls of the market through the exchange of information from time to time, especially about prices, quality and price–quality ratios.

- iii.

- Price–quality:

Quality is an important factor behind the establishment of marketing cooperatives. It is actually a variation of what has been observed about price and quantity. Cooperatives work towards improving quality as a very first step towards getting a better price. They can discriminate prices among producers in case of heterogeneous deliveries and provide a premium due to higher quality [28,29]. Many well-known regional agricultural products can be traced back to cooperative initiatives. The added value is then distributed over all the products that their members supply, and everyone earns a little extra. The differentiation of quality to fresh agricultural products can create a strong membership, which is typical for highly specialized transactions between producer and marketing cooperative [30]. Conversely, many cooperatives were established for the purpose of ensuring members that they would have access to high-quality products or services. Many marketing and consumer cooperatives have contributed to the raising of average quality standards playing the role of “quality leader” in the market. If they place a premium on quality, the competition would have to follow suit [23].

Although the regulatory role of marketing cooperatives in the market has proven to be significant, many researchers [31,32] report poor performance (and consequently low impact) of many marketing cooperatives worldwide [33], focusing on weak governance, management and market access that subsequently discourage members from entering into cooperatives [21,34,35]. In several cases of inefficient cooperatives, member participation and commitment in cooperatives (crucial for coop sustainability and performance) were identified to be extremely low [8]. This situation may be convenient for some marketing cooperatives as the members do not interfere in CEOs’ decision-making and therefore they can apply their strategies without objections (agency or control problems) from the members (principals).

Regarding inclusion in the decision-making process, Ref. [36] demonstrates that wealthier farmers benefit more from group services than poorer farmers, leading to the unwillingness of the latter to participate in the decision-making process in banana groups in Kenya. A recent research study showed that the probability of being a member of a coffee cooperative significantly increases with household age (up to a certain level) [33]. The strong association of age with the probability of participation can be justified by farming experience that correlates with the age of farmers [37]. A household with a higher education level has, ceteris paribus, about a 7.8% higher probability of participation in a marketing cooperative [18]. Moreover, producers with larger landholdings are more likely to join marketing cooperatives. That is, those households who have one unit more land have about a 35% higher probability of participation in a marketing cooperative. Generally, the estimation results of this research indicated that better-off farmers (in terms of experiences, wealth and access to information) are more likely to join marketing cooperatives.

A factor that discourages members from participating in marketing cooperatives is the strong interpersonal relations of some members with CEOs who manage to ensure favorable conditions in the cooperative (the influence cost problem). Moreover, when marketing cooperatives provide different groups of members with different services, a potential discrepancy of interests may be created and become extremely counter-productive [38,39,40]. In such cases, members at large do not understand the strategies and developments in their marketing cooperatives, have limited information about them, have little experience with them and thus are alienated from them [8,41].

Free-riding behavior and avoidance of investing in the marketing cooperative are common problems of many marketing cooperatives [35] that affect cooperative performance. Additionally, in some cases, the increased quality standards of some marketing cooperatives discourage some members from participating in cooperatives. They prefer to drive their produce to other selling points than to adapt their cultivation methods to the cooperative quality standards, or they occasionally trade with marketing cooperatives. On the contrary, members’ homogeneous motives regarding the participation in cooperative affairs facilitate lower transaction costs and fewer problems of common ownership, stronger social and economic ties, easier consensus building and democratic decision making and better incentives for member provision of equity capital [42].

In the present article, the following research hypotheses were investigated:

- Producers participate in marketing cooperatives in order to strengthen their bargaining power.

- Producers participate in marketing cooperatives in order to reduce their production costs.

- Price/Quality ratio is a determinant factor for producers’ participation in marketing cooperatives.

- Members’ inability to take collective decisions is one of the most important factors for non-participation in marketing cooperatives.

3. Material and Methods

The research was conducted during the summer of 2020. The primary objective was to investigate the regulatory role of the Greek collective actions in the F&V supply chain operation. For this purpose, at the beginning of the research, a limitations group was held with twelve producers in order to illustrate the factors that promote the establishment and participation in fruit and vegetables marketing cooperatives. These factors included bargaining power, direct marketing of fresh agricultural products, production cost, the price–quality relationship for fresh agricultural products, economic transactions with the organizations, collective investments to fixed capital, up-to-date technology and technical knowledge [43]. The result of this process was a quantitative questionnaire including closed-ended questions (yes or no, multiple-choice and five-point scale). The structure of the questionnaire consisted of three parts: (1) socio-demographic characteristics (Table 1), (2) motives for participation in marketing cooperatives (Table 2) and (3) the disincentives for members’ participation in marketing cooperatives (Table 3).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents.

Table 2.

Indicate your degree of agreement for the motives that you have pursued to be a member in a marketing Cooperative (1 = Totally Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Totally Agree).

Table 3.

Indicate your degree of agreement for the disincentives that you have not pursued to be a member in a marketing cooperative (1 = Totally Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neither agree nor Disagree, 4 = Agree, 5 = Totally Agree) Percentage (%).

At each stage of the research, two teams of two data collectors visited producers primarily on weekdays between 10 am and 7 pm. The personal interviews with producers were carried out in Imathia prefecture, which is 72 km from the Thessaloniki urban complex in the northern part of Greece. The study area was characterized by a high involvement of collective actions, wholesalers and retailers in F&V trading. The wholesalers supply F&V to the city of Thessaloniki, to other major cities in the country and/or to neighboring countries. However, no official data are available about the number of wholesalers in the region. The questionnaire was answered by sixty-one producers mainly by the surroundings of Veroia, the capital city of Imathia. The respondents’ socio-demographic characteristics are depicted in the following table (Table 1).

The method followed for data collection was the snowball approach [44]. This approach was applied because it elaborates on the motives for cooperation in the F&V supply chain [45]. The sample of the study was a convenience sample. The common interests of Greek producers for marketing fresh agricultural products through the local marketing cooperatives led the researchers to investigate the specific characteristics of these individuals with this method (snowball sampling). The local meetings with the producers gave the impetus to highlight the role of marketing cooperatives in the Greek countryside, increasing the number of producers who wanted to participate in this specialized research.

4. Research Hypotheses

4.1. Producers Pursue via Marketing Cooperatives to Strengthen Their Bargaining

Working with this research hypothesis, an effort was made to explain the economic efficiency of the marketing cooperatives, especially when they have economic transactions with third parties [46]. Particularly, more and more producers are augmenting the countervailing power to traders (wholesalers, retailers), determining the price of their agricultural products at a higher level [47]. For this reason, we examined if the bargaining power operates as a motive power for the accession of producers to marketing cooperatives. In addition, the existence of correlations between bargaining power, producers’ age, producers’ education level and producers’ income were examined (tests of normality, parametric or non-parametric tests).

4.2. Producers Have the Ability through Marketing Cooperatives to Reduce Their Production Costs

Typical costs of membership include the production, transaction and opportunity costs resulting from membership commitments [20,21]. The participation of producers in marketing cooperatives assists them in reducing production costs because they have access to precision agriculture and direct marketing of fresh agricultural products without losses [25]. In addition, the existence of correlations between bargaining power, producers’ age, producers’ education level and producers’ income were examined (tests of normality, parametric or non-parametric tests).

4.3. The Relation between Price and Quality Motivate Producers to Join a Cooperative

A cooperative can discriminate prices among farmers in case of heterogeneous deliveries and provide a premium due to higher quality [28,29]. The differentiation of quality to fresh agricultural products can create a strong membership, which is typical for highly specialized transactions between farmer and marketing cooperative [30]. Here also the existence of correlations between bargaining power, the producers’ age, producers’ education level and the producers’ income were examined (tests of normality, parametric or non-parametric tests).

4.4. Members’ Inability to Take Collective Decisions Is One of the Most Important Factors for Non-Participation in a Marketing Cooperative

The inability of taking collective decisions is what causes the phenomenon of the free-riding problem. Collective actions during their life cycle face five problems: free riding problems, control problems, influence cost problems, and horizon and portfolio investments constraints [48]. These problems stem from member heterogeneity during periods of organizational growth. Homogeneous interests facilitate lower transaction costs and fewer problems of common ownership, stronger social and economic ties, easier consensus building and democratic decision making, and better incentives for member provision of equity capital [42]. The existence of correlations between bargaining power, producers’ age, producers’ education level and producers’ income were also examined (tests of normality, parametric or non-parametric tests).

5. Results and Discussion

The main motives for F&V producers pursued to be members in a marketing cooperative are the following (Table 2): (1) they ensure safer financial transactions (53.7%), (2) they have direct distribution of fresh agricultural produce (41.5%), (3) they benefit from collective investments in fixed capital via the marketing cooperative (41.5%), (4) the relation of price–quality that the cooperative offers is a determinant factor for the entrance into the marketing cooperative (36.6%). The above results are in line with the results of [49]. However, in this research, respondents showed lower a percentage of preference for the classic motives to participate in a marketing cooperative, such as: (1) bargaining power (29.3%) and (2) production cost (29.3%) (Table 2).

Moreover, the results of the statistical analysis for the correlation between the motives for which producers pursued to be members in a marketing cooperative and producers’ education level indicated that quantitative variables do not follow a normal distribution (test of Normality: Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk, p-value < 0.05) (Table 4). The results of a non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the motives of participation in an agricultural cooperative, that is, bargaining power and direct distribution of fresh agricultural produce between the three categories of education level (sig < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Tests of Normality Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk for the motives that producers have pursued to become members in a marketing cooperative.

Table 5.

Non-parametric test, Kruskal–Wallis, between the motives that producers have pursued to become members in a marketing cooperative and producers’ education level.

The results of the statistical analysis for correlation between the motives for which producers aimed to be members in a marketing cooperative and producers’ gross annual agriculture income indicated that the quantitative variables do not follow a normal distribution (test of Normality: Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk, p-value < 0.05) (Table 4). The results of the non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) showed that there is a statistically significant difference in the reason for participation in a marketing cooperative (collective investments in fixed capital) between the three categories of gross annual agriculture income (sig < 0.05) (Table 6). Similar research for the producers’ participation in marketing cooperatives in Armenia proved that for the producers, a major statistical factor was the level of education, which gives them the potential to have access to new technology [50]. A research study in north China [51] showed that the producers participate in marketing cooperatives in order to increase their financial prosperity since they reduce the risks in the commerce of their agricultural products (safer financial transactions). Another research in the production of watermelons in China [52] proved that significant factors for the producers’ participation in marketing cooperatives are the adoption of new technology methods by them and the fickleness of the agricultural production in the field of fruits.

Table 6.

Non-parametric test, Kruskal–Wallis, between the motives that producers have pursued to become members in a marketing cooperative and producers’ gross annual agriculture income.

At the other end of the spectrum, the reasons for which the producers in this research do not participate in collective actions are the following: (1) the great divergence of the reasons for the members’ participation in a marketing cooperative (45%), (2) the inability to take collective decisions by the general meeting (40%), (3) the ensuring of more satisfactory prices through the wholesalers (35%).

The results of the research prove that the lack of homogeneity among the cooperative members is an obstacle that creates the great divergence in the reasons for the members’ participation in them [6]. The results of this heterogeneity are what lead the producers-members to not pursue investing in those cooperatives and simultaneously to create a more laissez-faire commitment to them and other members [53]. In addition, the decisions made by the marketing cooperatives for engagement in different fields of agriculture (e.g., cotton, fruit and vegetables, and legumes), in a short term from their establishment, increases the complexity of communication and taking collective decisions [54] by the members (producers) and the administration. The inability to take collective decisions is also what causes the phenomenon of free riding [55], after which many members distribute a large part of their agricultural produces out of the marketing cooperative, enjoying the benefits (e.g., better prices with tax avoidance in some cases) from the wholesalers (Mediators) [56].

The results of the statistical analysis for correlation between the reasons for which producers did not pursue being members in a marketing cooperative and producers’ gross annual agriculture income indicated that the quantitative variables do not follow normal distribution (Test of Normality: Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk, p-value < 0.05), except for the quantitative variable (I do not trust cooperative movement) (Table 7). For this reason, for the quantitative variable (I do not trust cooperative movement), a parametric test was performed (variance analysis one-way ANOVA), while for the other quantitative variables, non-parametric tests were followed (Kruskal–Wallis), since the producers’ gross annual agriculture income has more than two categories. After a one-way ANOVA test, it was found that there is no statistically significant difference to the quantitative variable (I do not trust cooperative movement) between the three categories of producers’ gross annual agriculture income (Table 8). A non-parametric test (Kruskal–Wallis) indicated that there is a statistically significant difference to the quantitative variable (The cooperatives’ requirements for high quality fresh produce are a suspending factor for my participation to them) between the three categories of producers’ gross annual agriculture income (sig < 0.05) (Table 9). According to research in Thessaly and Western Macedonia regions, [57] the factors affecting the decision of farmers to invest in cooperatives were: (1) the farmer’s commitment to the cooperative, (2) the member’s perceptions of past managerial failures and 3) the member’s perception of the cooperative’s future strategies.

Table 7.

Tests of normality Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk for the disincentives that producers have not pursued to become members in a marketing cooperative.

Table 8.

Parametric test variance analysis one-way ANOVA between the quantitative variable “I do not trust cooperative movement” and producers’ gross annual agriculture income.

Table 9.

Non-parametric test Kruskal–Wallis between the disincentives that producers have not pursued to become members in an agricultural cooperative and producers’ gross annual agriculture income.

6. Conclusions, Suggestions for Further Research and Limitations

Cooperatives could play a significant regulatory role in the F&V supply chain in Greece. However, due to several obstacles and weaknesses, only a few of them manage to respond to this role. As a consequence, many producers avoid their participation in marketing cooperatives while others insist on supporting them. Identifying the motives of producers to participate or not in a marketing cooperative are the main aims of this research.

The research results reveal that the most important motives for participation in collective actions of the F&V sector are the safe financial transactions, the direct distribution of fresh agricultural produce, the benefits from collective investments in fixed capital and the price/quality ratio. Respondents showed lower percentage preferences for the classical motives of “increased bargaining power” as well as of “production cost reduction”. These preferences reveal that producers have greater expectations from their marketing cooperatives and seek specialized services in order to compensate for their vulnerable position in the supply chain. A recent research study in a neighboring area revealed that the main reasons for participation in agricultural cooperatives in the fruit sector are the family tradition, the safer financial transactions as well as the increased bargaining power [12]. The “bargaining power” as well as the “direct distribution of fresh agricultural products” were differentiated in the three categories of education level. The results show that well-educated producers appreciate these functions more in Greek marketing cooperatives.

The incentive for “collective investments in fixed capital via marketing cooperatives” was differentiated into the three categories of producers’ gross annual agriculture income. This differentiation supports the aspect that poorer producers avoid participation in collective ventures, increasing their transaction costs in F&V supply chain.

At the other end of the spectrum, the reasons for not participating in collective actions of the F&V sector are the “great divergence of the reasons of the members’ participation”, the “inability of taking collective decisions in the General Assembly” and the “more satisfactory direct prices that producers ensure from wholesalers/traders”.

These motives reveal the lack of the “cooperative spirit” as well as of the appropriate education background to understand the reasons that marketing cooperatives exist in the market. Therefore, policymakers should invest in the change of these attitudes in order to reverse the free riding mood of the cooperatives that undermines their viability. Another element of our research that proves this tendency is the fact that the factor “the cooperatives’ requirements for high quality fresh produce are a suspending factor for participation” showed statistically significant difference in the three categories of producers’ gross annual agriculture income.

This differentiation indicates that agricultural collective actions of the F&V sector impose on their members particular international standards of quality in order to confront the high requirements of food retailers in the F&V market globally. The Greek producers with downgraded quality of their fresh agricultural products will receive lower prices. The separation of quality in fresh agricultural products is able to create higher competitiveness in the supply chain for Greek marketing cooperatives, eliminating the free riding problem. The elimination of the free riding problem gives the opportunity to cooperatives to apply branding strategies, creating strong brand names for fresh F&V in the market.

What seems to be an important future research topic is the retailers’ choices to allocate resources to train lower quality producers in order to raise product quality to a higher level. That is, despite starting with greater heterogeneity in terms of producers’ capacity to produce high-quality products, marketing cooperatives may achieve high-quality products through superior coordination and technology adaptation support. Moreover, it is worth investigating whether the producers–wholesalers relationship characteristics are able to mitigate agency problems related to information asymmetry in the production of quality attributes in the agri-food sector, as well as the impact of short food supply chains (social, economic and environmental) on the relationships between producers and consumers.

This study has some limitations. First, the sample consists of producers located in a specific area of northern Greece. A fruitful direction of future research is to examine whether F&V producers located in other regions of Greece confirm these empirical findings. Second, it would be helpful to include in future research the CEOs’ opinion about the motives that encourage or discourage producers to participate in marketing cooperatives.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B. and A.K.; methodology, A.B.; software, A.B.; validation, A.K., F.C. and P.S.; formal analysis, A.B.; investigation, A.B.; data curation, A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K. and P.S.; writing—review and editing, F.C.; visualization, F.C. and P.S.; supervision, P.S.; project administration, A.K., and P.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rossi, R. Protecting the RU Agri-Food Supply Chain in the Face of COVID-19. European Parliament Research Service. Think Tank. Available online: www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Ton, G.; Bigman, J.; Oorthuizen, J. Producer Organizations and Market Chains. Facilitating Trajectories of Change in Developing Countries, 1st ed.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2007; p. 321. ISBN 978-90-8686-048-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlino, V.M.; Borra, D.; Bargetto, A.; Blanc, S.; Massaglia, S. Innovation towards sustainable fresh-cut salad production: Are Italian consumers receptive? AIMS Agric. Food 2020, 5, 365–386. Available online: http://www.aimspress.com/article/10.3934/agrfood.2020.3.365 (accessed on 30 October 2020). [CrossRef]

- Camanzi, L.; Malorgio, G.; Azcárate, G.T. The role of Producer Organizations in supply concentration and marketing: A comparison between European Countries in the fruit and vegetables sector. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2011, 17, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergaki, P.; Michailidis, A. Small-Scale Food Producers: Challenges and Implications for SDG2. In Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Iliopoulos, C.; Valentinov, V. Member preference heterogeneity and system—Life world dichotomy in cooperatives: An exploratory case study. JOCM 2017, 30, 1063–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benos, T.; Kalogeras, N.; Verhees, F.; Sergaki, P.; Pennings, J.M.E. Cooperatives’ Organizational Restructuring, Strategic Attributes and Performance: The Case of Agribusiness Cooperatives in Greece. Agribusiness 2016, 32, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhees, F.; Sergaki, P.; Van Dijk, G. Building up active membership in cooperatives. New Medit. 2015, 14, 42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Wassie, S.B.; Kusakari, H.; Masahiro, S. Inclusiveness and effectiveness of agricultural cooperatives: Recent evidence from Ethiopia. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2019, 46, 614–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Lin, D.; Liu, J.; Li, Y. Quantifying the effects of non-tariff measures on African agri-food exporters. Agrekon 2019, 58, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokchea, A.; Culas, R.J. Impact of Contract Farming with Farmer Organizations on Farmers’ Income: A Case Study of Reasmey Stung Sen Agricultural Development Cooperative in Cambodia. Australas. Agribus. Rev. 2015, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S. Economic Cooperative Models: Agricultural Cooperatives in Greece and the Need to Modernize their Operation for the Sustainable Development of Local Societies. IJARBSS 2020, 10, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD Competition Assessment Reviews: Greece. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/daf/competition/Greece-Competition-Assessment-2013.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Efthymiou, P. New type Business Cooperatives. Research and Analysis Organization. Available online: https://www.dianeosis.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/11/Agro_Synetairismoi_29.11.17_Upd.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Koutsou, S.; Sergaki, P. Producers’ cooperative products in short food supply chains: Consumers’ response. Br. Food J. 2019, 122, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, M.; Paschou, M. Alternative Forms of Resilience: A Typology of Approaches for the Study of Citizen Collective Responses in Hard Economic Times. Partecip. Confl. 2017, 10, 136–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, V.J.; Dauve, J.L.; Parcell, J.L. The Agricultural Marketing System, 6th ed.; Holcomb Hathaway: Scottsdale AZ, USA, 2007; pp. 253–254. [Google Scholar]

- Abate, G.T. Drivers of agricultural cooperative formation and farmers’ membership and patronage decisions in Ethiopia. J. Co-Oper. Organ. Manag. 2018, 85, 257–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Statistical Factsheet Greece. 2020. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/food-farming-fisheries/farming/documents/agri-statistical-factsheet-el_en.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Sykuta, M.E.; Cook, M.L. A new institutional economics approach to contracts and cooperatives. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2001, 83, 1273–1279. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1244819 (accessed on 30 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fulton, M.; Giannakas, K. Organizational commitment in a mixed oligopoly: Agricultural cooperatives and investor-owned firms. JSTOR 2001, 83, 1258–1265. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23883785 (accessed on 30 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.L. The labour utilization problem in European and American Agriculture. J. Agric. Econ. 1960, 14, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, G.; Sergaki, P.; Baourakis, G. The Cooperative Enterprise. Practical Evidence for a Theory of Cooperative Entrepreneurship, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 1–204. [Google Scholar]

- Vorley, B. The chains of Agriculture: Sustainability and the Restructuring of Agri-Food Markets. World Summit on Sustainable Development, International Institute for Environment and Development. 2001. Available online: https://pubs.iied.org/pdfs/11009IIED.pdf (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- Fikar, C.; Leither, M. A decision support system to facilitate collaborative supply of food cooperatives. Product. Plan. Control 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J. Agricultural cooperatives and market orientation: A challenging combimation? In Market Origination: Transforming Food and Agribusiness Around the Customer, 2nd ed.; Lindgreen, A., Hingley, M., Harness, D., Custance, P., Eds.; Gower Publishing: Aldershot, UK, 2016; Volume 7, pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Cavicchi, A. Market orientation. Transforming food and agribusiness around the customer. J. Cons. Mark. 2011, 28, 388–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, R. Ownership Structure and Endogenous Quality Choice: Cooperatives versus Investor-Owned Firms. J. Agric. Food Ind. Organ. 2005, 3, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.A.; Spreen, T.H. Co-ordination strategies and non-members’ trade in processing. JAE 1985, 36, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, E. Farmers’ willingness to invest in new cooperative instruments: A choice experiment. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2019, 90, 161–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giagnocavo, C.; Galdeano-Gómez, E.; Pérez-Mesa, J.C. Cooperative Longevity and Sustainable Development in a family farming system. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, G.F.; King, R.P. Agricultural Cooperatives I: History, Theory and Problems. Agrekon 2007, 46, 40–68. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03031853.2007.9523760 (accessed on 30 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Mojo, D.; Fischer, C.; Degefa, T. The determinants and economic impacts of membership in coffee farmer cooperatives: Recent evidence from rural Ethiopia. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 50, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaddad, F.R.; Iliopoulos, C. Control Rights, governance and the cost of ownership in agricultural cooperatives. Agribusiness 2013, 29, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Österberg, P.; Nilsson, J. Members’ Perception of Their Participation in the Governance of Cooperatives: The Key to Trust and Commitment in Agricultural Cooperatives. Agribusiness 2009, 25, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, E.; Qaim, M. Smallholder farmers and collective action: What determines the intensity of participation? J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 65, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesconi, G.N.; Ruben, R. The Hidden Impact of Cooperative Membership on Quality Management: A Case Study from the Dairy Belt of Addis Ababa. JEOD 2012, 1, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeras, N.; Pennings, J.M.E.; van der Lans, I.A.; Garcia, P.; Van Dijk, G. Understanding Heterogeneous Preferences of Cooperative Members. Agribusiness 2009, 25, 90–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.L.; Iliopoulos, C.; Chaddad, F. Advances in cooperative theory since 1990: A review of agricultural economics literature. In Restructuring Agricultural Cooperatives, 1st ed.; Hendrikse, G.W.J., Ed.; Hendrick Martenszoonsorgh, De Groentemarkt, 1662; Rijksmuseum: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 5, pp. 65–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, O.D.; Moore, J. Cooperatives vs. Outside Ownership; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998; Available online: https://www.nber.org/papers/w6421 (accessed on 30 December 2020). [CrossRef]

- Iiro, J.; Byrne, N.; Tuominen, H. Affective commitment in Co-operative organizations: What make members want to stay? IBR 2012, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohler, J.; Kühl, R. Dimensions of member heterogeneity in cooperatives and their impact on organization-a literature review. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2018, 89, 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngamjan, P.; Buranasiri, J. An Investigation of the Factors Influencing the Financial Performance of Agricultural Cooperatives in Thailand. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2020, 28, 2343–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumaran, R. Enablers for Economically Viable Agricultural Cooperatives: A Case Study on Chile. Master’s Thesis, Master Sustainable Business and Innovation. Universiteit Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2020. Available online: https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/397817 (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Stewart, D.W.; Kamins, M.A. Conducting Case Studies: Collecting the Evidence. In Case Study Research Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; (Applied Social Research Methods Series; Volume 5); Yin, R.K., Ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003; Volume 4, pp. 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Alho, E. Assessing the willingness of non-members to invest in new financial products in agricultural producer cooperatives. Agric. Food Sci. 2017, 26, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alho, E. Farmers’ self-reported value of cooperative membership: Evidence from heterogeneous business and organization structures. Agric. Econ. 2015, 3, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, M. A life cycle explanation of cooperative longevity. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, K.; Yu, X. Direct intervention or indirect support? The effects of cooperative control measures on farmers’ implementation of quality and safety standards. Food Policy 2019, 86, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyulgyulyan, L.; Bobojonov, I. Factors influencing on participation to agricultural Cooperatives in Armenia. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2019, XI, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, S.; Wang, Z.; Awokuse, T.O. Determinants of producers’ participation in agricultural cooperatives: Evidence from Nothern China. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2012, 34, 167–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, J.; Bao, Z.; Su, Q. Distributional effects of agricultural cooperatives in China: Exclusion of Smallholders and potential gains on participation. Food Policy 2012, 37, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraud-Didier, V.; Henninger, M.C.; El Akremi, A. The Relationship between Members’ Trust and Participation in the Governance of Cooperatives: The Role of Organizational Commitment. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Kneer, G.; Nassehi, A. Niklas Luhmanns Theorie Sozialer Systeme; Wilhelm Fink: Paderborn, Germany, 2000; ISBN1 -10 3825217515. ISBN2 -13 978-3825217518. Available online: https://www.worldcat.org/title/niklas-luhmanns-theorie-sozialer-systeme-eine-einfuhrung/oclc/878401297 (accessed on 30 December 2020).

- Hendriske, G.W.J.; Feng, L. Interfirm cooperatives. In Handbook of Economic Organization, Integrating Economic and Organization Theory, 1st ed.; Grandori, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2013; Volume 26, pp. 501–521. [Google Scholar]

- Giannakas, K.; Fulton, M.; Sesmero, J. Horizon and Free-Rider Problems in Cooperative Organizations. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 41, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorgos, A.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Theodossiou, G. Willingness to Invest in Agricultural Cooperatives: Evidence from Greece. J. Rural Coop. 2014, 42, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).