Abstract

Sustainable development requires a shift from traditionally invested assets to socially responsible investing (SRI), bringing together financial profits and social welfare. Private high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) are critical for this shift as they control nearly half of global wealth. While we know little about HNWIs’ investment behavior, reference group theory suggests that their SRI engagement is influenced by their identification with and comparison to reference groups. We thus ask: how do reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs? To answer this question, we analyzed a unique qualitative data set of 55 semi-structured interviews with SRI-oriented HNWIs and industry experts. Our qualitative research found that, on the one hand, the family serves as a normative reference group that upholds the economic profit motive and directly shapes HNWIs to make financial gains from their investments at the expense of social welfare. On the other hand, fellow SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a comparative reference group that does not impose any concrete requirements on social welfare performance, indirectly influencing SRI-oriented HNWIs to subordinate social concerns to financial profits. Our scholarly insights contribute to the SRI literature, reference group theory, and practice.

1. Introduction

A shift from traditionally invested assets to socially responsible investing (SRI), broadly defined as the integration of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) considerations into investment practices, is a crucial driver of sustainable development [1]. Millionaires and billionaires, i.e., private high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), hold a vital role in this shift. The United Nations calculated that investments of USD2.5 trillion per year are missing to finance sustainable development [2]. Thereby, the wealthy top 1% of the world’s population controls about USD 191.6 trillion as of 2020, nearly half of global wealth [3]. It is crucial to understand the investment behaviors of HNWIs to mobilize this substantial source of capital for sustainable development.

To understand whether private investors engage in SRI, the literature tends to put a higher emphasis on proving the financial profitability of SRI (see [4,5,6]) than, for example, its positive impact on social welfare [7,8]. However, since SRI brings together financial profits and social welfare, sustainable investing goes well beyond the question of whether or not SRI is more profitable than traditional investing [6,9,10,11,12,13]. Still, many investors are attracted to SRI due to social welfare reasons (e.g., [14,15,16]). Consequently, the profitability debate around SRI only partially solves the issue of knowing little about sustainable investors [16,17] and SRI-oriented HNWIs [18,19]. To gain deeper insight into the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs, we need to understand their individual dealings with both social welfare issues and financial gains in their SRI investments.

A reference group theory perspective suggests that the individual investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs is fundamentally influenced by the groups for which the wealthy private investor has a membership. The reference group theory operates on the principle that individuals always orient themselves to others, as their attitudes, values, and self-appraisals are shaped by their identification with and comparison to reference groups [20]. To establish or maintain individual identification with the reference group, individuals behave, believe, and perceive as the group does [21]. There are two types of reference groups [22,23,24]. Normative reference groups establish and enforce specific standards which can be considered as norms. Comparative reference groups serve individuals as a point of reference in making evaluations or comparisons without the evaluation of the individual by others in the reference group [23].

Hence, from a reference group theory perspective, SRI-oriented HNWIs’ identification with and comparison to a respective reference group significantly influences whether, how, and to what extent they bring together financial profits and social welfare in their investments. Thus, while the influence of normative and comparative reference groups is central to our understanding of the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs, previous research has not yet addressed this issue. Consequently, our knowledge of HNWIs committed to SRI remains underdeveloped. The main objective of our study is to develop this knowledge, and we thus ask: how do reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs?

To answer this question, we adopt a qualitative research strategy. Such a strategy is advantageous for developing our knowledge of the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs because qualitative research supports the generation of novel insights “at a level of detail and nuance that can be difficult or impossible to achieve using only quantitative methods” [25] (p. 637). We conducted semi-structured interviews with 42 SRI-oriented HNWIs and 13 experts who consult with them and closely monitor the SRI market. Based on our analysis of this unique empirical data, we develop a framework to explain how different reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. Our framework indicates that, on the one hand, the family serves as a normative reference group that holds up economic profit striving and directly influences HNWIs towards generating financial profits in their investments at the expense of social welfare considerations. On the other hand, fellow SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a comparative reference group that places little emphasis on accountability for social issues and indirectly influences SRI-oriented HNWIs to subordinate social welfare issues to financial gain.

Our research makes two contributions to the literature. First, we add to SRI research by providing insights into the hitherto little-researched SRI engagement of wealthy private investors (e.g., [16]). Our framework explains that SRI-oriented HNWIs prioritize financial gains at the expense of social welfare because they are encouraged by reference groups to use their wealth to achieve economic profits, even though they already have immense wealth. Second, we contribute to reference group theory, which suggests different reference groups based on differentiating between a normative and a comparative function of a reference group (e.g., [23]). We show that normative and comparative reference groups can coexist but that the normative reference group suppresses the comparative reference group in conflict. This finding implies different spheres of influence of normative and comparative reference groups.

We proceed by presenting existing SRI research on HNWIs and, on this basis, problematizing the lack of knowledge on the influence of reference groups on the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. We then outline our research context and method and present the results of our study. On this basis, we develop a framework of how reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. We finish by discussing the implications for the literature, some practical implications, the limitations of our study, avenues for further research, and a conclusion.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) and High-Net-Worth Individuals (HNWIs)

Socially responsible investing (SRI) integrates environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues into investment practice and closely links to sustainable development [26,27]. The peculiarity of SRI, especially compared to traditional investing, is that it combines two different and potentially conflicting logics: while the market logic has the primary characteristic of the pursuit of financial profit, the social welfare logic is grounded on communitarianism, altruism, the fulfillment of social needs, and the solving of social misery (see [6]). Regarding the segment of private SRI-oriented investors, some studies address their characteristics, motivations, and barriers and provide comparisons with non-SRI investors (e.g., [28,29,30,31,32]). Among private investors, those with discretionary investable assets of more than USD 1 million, defined as high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs), are of particular interest [33]. While as of 2020, HNWIs represent 1.1% of the world’s population, they hold 46% of global household wealth [3] and can thus contribute significantly to the growth of SRI. HNWIs tend to be interested in incorporating SRI aspects, such as climate change, into their investment decisions, as they “are typically long-term investors whose aim is to preserve capital for the next generations to come” [33] (p. 7). Moreover, HNWIs are in the position where they can invest along with their personal interest because they “have access to investments that are normally closed to smaller retail investors, and the freedom to move funds quickly without having to perform the extensive due diligence required by institutional investors” [33] (p. 7).

To understand whether private investors engage in SRI, the academic literature puts a higher emphasis on the ability to prove the financial profitability of SRI (see [4,5,6]) than, for example, its positive impact on social welfare [7,8]. However, since SRI brings together financial profits and social welfare [6], sustainable investing goes well beyond the question of whether or not SRI is more profitable than conventional investing, as, evidently, “there are more nuanced issues at stake than just profits” [9] (p. 360) (see also [10,11,12]). Similarly, Revelli [34] (p. 711) critically notes that in the course of the efforts around the mainstreaming of SRI, “the original goal of ‘making good’” has transformed “into a quest for profitability”.

Addressing profitability can only help us understand to a limited extent whether investors are committed to SRI, as many investors are attracted to SRI due to altruistic motives [15,16]. For example, a study by Barreda-Tarrazona, Matallin-Saez, and Balaguer-Franch [14] shows that although diversification and return are essential drivers of SRI investment, private investors, who embrace SRI, tend to invest in SRI funds even when the return differential is negative. In their review of the SRI literature, Renneboog, Ter Horst, and Zhang [35] conclude that prior research suggests that SRI investors are willing to accept suboptimal financial profits to contribute to social welfare. The latter research supports the rising voices of scholars questioning the “business case” justification and associated profit maximization arguments for socially responsible business practices (e.g., [36,37]) and SRI (e.g., [6,34]). Juravle and Lewis [38] confirm this by showing that investors often do not engage in SRI because of cognitive patterns and normative belief systems. They note that even experienced investors are susceptible, for example, to herd behavior or fads and are guided in their investment behavior by the belief of the incompatibility of financial profit and social welfare.

Consequently, the profitability debate around SRI can only partially solve the circumstance of still knowing little about sustainable investors [16,17] and SRI-oriented HNWIs [18,19]. In contrast, a deeper insight into the investment behavior of SRI-oriented wealthy private investors requires that we go beyond this very debate and understand how HNWIs deal with social welfare issues and financial profits in their SRI investments. The point here is to consider that the individual investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs is always shaped by the group in which the wealthy private investor has a membership. Therefore, we introduce the reference group theory, which points out that individuals orient themselves to others, so-called reference groups, and thus individual thinking and acting are fundamentally shaped by others.

2.2. Reference Group Theory Perspective on the Investment Behavior of SRI-Oriented HNWIs

Generally, a reference group has been defined “as a group, collectivity, or person taken into account by an actor and used in such a manner that he identifies himself and uses the group, collectivity, or person as a basis for self-evaluation and as a source of his personal values and goals” [39] (p. 68). As this definition suggests, reference group theory builds on the assumption that human beings desire the feeling of oneness with groups [21]. Such non-formalized memberships give people the confidence that the appropriate strategies to manage one’s life are befitting and valid [20]. To obtain this group identity, one needs to behave, believe, and perceive as the group does [20,21,40,41] and socialize oneself to what one perceives to be the group’s norms [42]. Consequently, an individual’s attitudes, values, and self-appraisals are influenced by the identification with and comparison to reference groups [20]. This includes articulating and reasoning things important to oneself so that others will accept these explanations of what constitutes important [20]. Hence, the reference group influences the behavior of individuals due to anticipation of the responses of the group [43].

Reference group theory distinguishes between normative and comparative reference groups [22,23,24]. Normative reference groups are groups where individuals are motivated to establish or maintain acceptance. To reach that goal, individuals keep their attitudes in conformity with what they perceive to be the consensus of opinions (norms) among their reference group [20,23]. Here, the group establishes and enforces specific standards which can be considered as norms. Consequently, the normative function of a reference group is that it provides individuals with a basis for forming goals and values and expects them to comply with the goals and values of their reference groups [39]. Values are normative beliefs that guide human actions, as they specify “the things that are worth having, doing, and being” [44] (p. 356; see also [45]). Values are particularly central in normative contexts when, as in the case of SRI, it is a matter of conceptualizing the respective possibilities and limits in reconciling economic and social aspects [46].

On the other hand, comparative reference groups serve individuals as a point of reference in making evaluations or comparisons [23]. In a comparative reference group, the evaluations of the individual by others in the reference group are irrelevant. The group serves as a standard or checkpoint that the individual uses to make judgments [23]. The comparative function of a reference group thereby provides a frame of reference that an individual uses for self-evaluation, thus resulting in either a satisfactory or unsatisfactory view of oneself [39]. From a reference theory perspective, SRI-oriented HNWIs seek non-formalized membership in groups to gain the confidence that their investments are befitting and valid. In doing so, SRI-oriented HNWIs align their attitudes and behaviors toward investment with what they think the respective reference group expects of them. For example, in the case of other wealthy private investors, we would assume that HNWIs make economic success observable through their investment activities and behavior to maintain “social prestige” or “social status” within the group [47,48,49]. Financial profit would signal that the individual HNWI is adapting to what she or he thinks is necessary for membership in the reference group (in this case, other HNWIs).

Also, HNWIs regularly discuss their investment decisions with family members [18], suggesting that this group may serve as a basis for HNWIs’ self-assessment and personal values and goals. At the same time, SRI-oriented HNWIs are, of course, also influenced by other like-minded HNWIs. In this reference group, one would assume that members hold up and demand not only financial profit but at least equal claims regarding social welfare and expect that group members meet these standards. Hence, by contributing to social welfare through investments, an individual HNWI portrays that she or he behaves, believes, and perceives as the group of other SRI-oriented HNWIs does.

Unfortunately, there is no research on how reference groups influence HNWIs’ SRI engagement, even though the literature suggests that they would fundamentally influence how SRI-oriented HNWIs deal with social welfare issues and financial gains in their investments. Hence, our knowledge of the investment behavior of HNWIs committed to SRI remains limited, and our research correspondingly asks the following question: how do reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs?

3. Methods

We apply a qualitative inductive research design to gain detailed insights into how reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. Because of the nascent nature of theory in the context of SRI-oriented HNWIs (see, e.g., [18]), it is necessary to take a qualitative approach that ensures a “methodological fit” with our research endeavor [50]. For example, Bettis et al. [25] (p. 637) have indicated qualitative approaches as essential tools to generate new insights that document phenomena “at a level of detail and nuance that can be difficult or impossible to achieve using only quantitative methods” (see also, [51]).

3.1. Sampling Strategy and Data Collection

We use a purposeful sampling strategy aimed at gathering information-rich data sources “from which one can learn a great deal about issues of central importance to the purpose of the inquiry” and that provide “insights and in-depth understanding rather than empirical generalizations” [52] (p. 230). In contrast to approaches such as random sampling, purposeful sampling implies that the selection of data sources runs parallel to the data collection [53]. Simultaneously selecting and collecting the data increases the possibility of generating novel concepts and identifying theoretical relationships with information that either substantiates them or provides divergent examples [54].

We collected our data in the form of 55 semi-structured interviews with HNWIs and industry experts between 2015 and 2019 with the help of wealth owner networks in Europe and the United States. These interviews lasted, on average, 30 min, were recorded, and were fully transcribed. We interviewed 42 SRI-oriented HNWIs with different cultural backgrounds and sources of wealth creation (see Table 1). In the course of these interviews, we asked them about the role of wealth in society, their thoughts around considering ESG criteria in their investments, and their assessment of the importance of SRI for sustainable development. Our questions also addressed their understanding of SRI, the barriers they face, the values and beliefs they hold, and their expectations. Expectations included broader ideas such as overall visions and hopes for the SRI market and particular aspects such as financial return and social welfare contribution regarding their own SRI engagement.

Table 1.

Overview of informants and some background information.

We adopted a range of measures to enhance the reliability of our interview data. We posed “courtroom questions” [55] (p. 41) by asking SRI-oriented HNWIs the same questions to reduce self-reported biases. This technique helps to avoid speculation and enhances the reliability of the informants’ responses. As is standard in qualitative research (e.g., [56]), we granted anonymity to all informants to elicit candid responses [55]. Furthermore, we interviewed 13 experts who regularly consult with SRI-oriented HNWIs and closely monitor the SRI market, including advisors, managers, and researchers. This data was relevant for triangulating the interview data gained from the wealthy private investors.

Table 1 provides an overview of all our informants. The table typifies the informants into wealth owners and industry experts, with the latter further subdivided into advisors, managers, and researchers. In addition, the table includes information on each interviewee’s age, gender, nationality, country of residence, profession, approximate wealth, and highest academic degree.

3.2. Data Analysis

We used grounded theorizing and, more specifically, the “Gioia methodology” [57] to analyze our interview data. The Gioia methodology helps analyze interview data in the context of individuals concerned with social and environmental issues in a business context (see, e.g., [58]). This methodology is tailored to qualitative inductive inquiry and comprises three levels of abstraction [57].

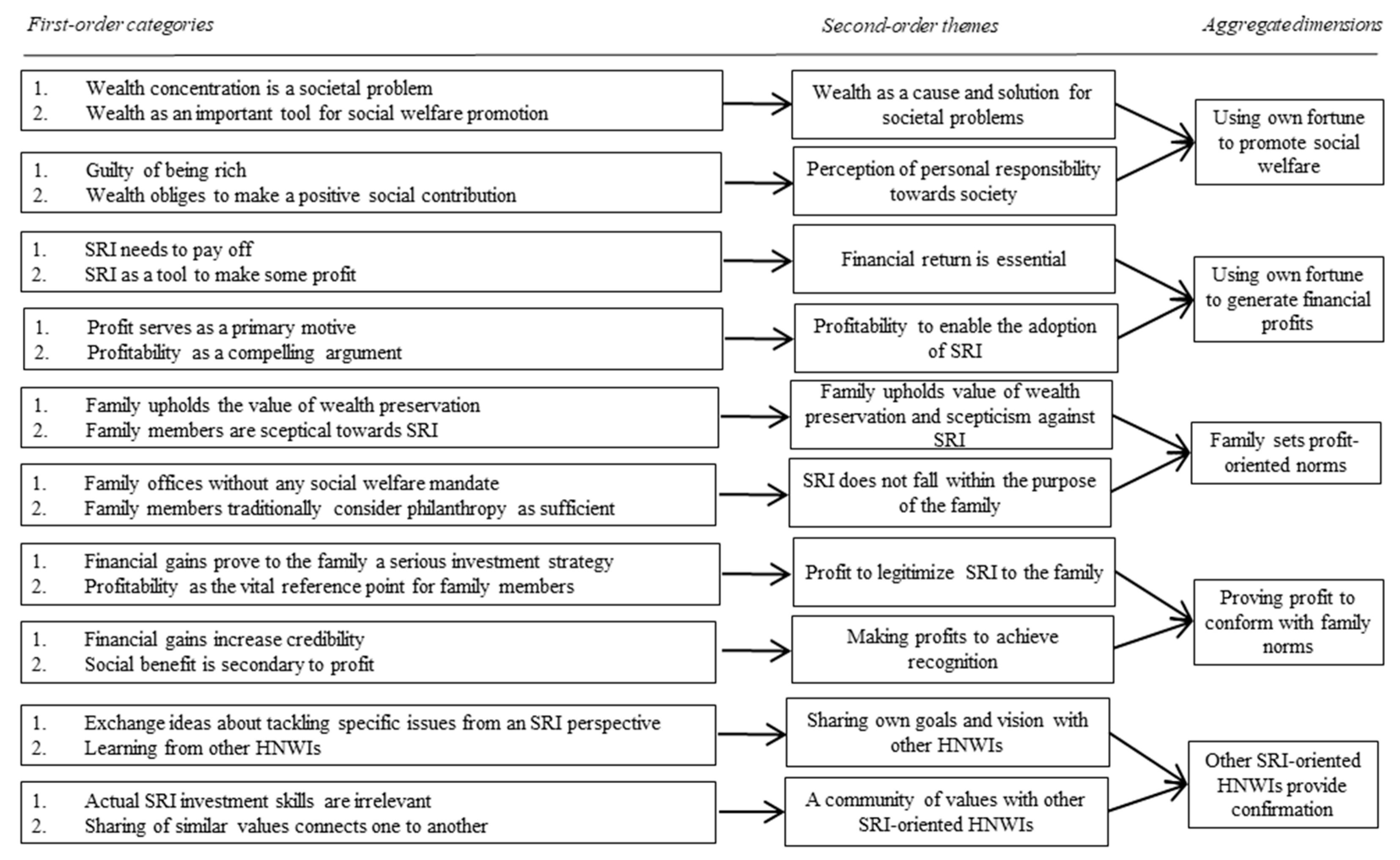

The first-order analysis is about processing the raw interview data to identify a primary set of codes. We classified those codes into different groups of descriptions that our informants provided. This initial assessment provided insights into what SRI-oriented HNWIs consider the prevalent problems that modern societies face and the potential ways to solve them, from political actions to philanthropy and sustainable investing. We have learned what role private wealth plays in this discussion, what opportunities wealthy persons have for adding to social welfare, and what responsibility they ascribe to themselves in this context. Moreover, we obtained preliminary knowledge of what role fellow HNWIs and their family members play in their SRI engagement. The result of this initial stage of analysis were several first-order category codes.

We then engaged in a second-order analysis. We analyzed additional data and studied the literature to incrementally move from the first-order insights toward more theoretical second-order themes. We continuously iterated back and forth between data and literature and gradually developed theory [59]. At this stage, we particularly noticed that SRI-oriented HNWIs see wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems and feel personally responsible to society. Furthermore, we learned how the latter use SRI to make financial profits, what their families expect from them, and how SRI-oriented HNWIs try to meet these exact expectations. Moreover, we realized the importance of their peers with whom they share the same values, goals, and visions. The importance of like-minded wealthy private investors and families prompted us to review the literature on reference theory in-depth, stimulating a related oscillation between theory and empirical data. The result of this analysis was a set of second-order themes.

We processed additional data to identify the interaction between key constructs on the highest level of analysis leading to aggregate dimensions. More specifically, we categorized raw data, linked first-order categories to second-order themes, and aggregated them into third-order dimensions. The result was five aggregate dimensions: first, using one’s own fortune to promote social welfare; second, using one’s own fortune to generate financial profits; third, one’s family sets profit-oriented norms; fourth, proving one’s profit to conform with family norms; and fifth, other SRI-oriented HNWIs provide confirmation.

Throughout the data analysis, we ensured intercoder reliability. To this aim, we used the data analysis software NVivo. This software helps organize large amounts of qualitative data and provides the basis for performing data analysis in a team. The authors held regular meetings to cross-check the coding and ensure the development of the same understanding of the emerging categories, moving from open coding over more theoretical categories to aggregate dimensions. Figure 1 shows our data structure and, thereby, provides an overview of the three levels of abstraction in line with the Gioia methodology. In this vein, the figure depicts our inductive reasoning process from empirical raw data in the form of first-order categories over second-order themes to more abstract theoretical categories in the form of aggregate dimensions.

Figure 1.

Data structure.

In the following findings section, and according to conventions in qualitative research (e.g., [60]), we offer power quotes throughout the text and, per subsection, provide additional interview data supporting our empirical analysis in Tables 2–11.

4. Findings

We structure the empirical results as follows: first, we outline how HNWIs use their own fortunes to promote social welfare. Second, we show that they use their fortunes to generate financial profits. Third, we depict how the family sets profit-oriented norms. Fourth, we demonstrate that SRI-oriented HNWIs engage in proving profit to conform with family norms. Finally, we present how other SRI-oriented HNWIs provide confirmation.

4.1. Using Own Fortune to Promote Social Welfare

When asked about their motives for SRI, HNWIs often pointed out that they strive to use their fortune to promote social welfare. In the following, we will discuss two aspects of our data supporting this insight.

Wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems. Wealth has an essential role in society in that it functions equally as a cause of and solution to societal problems such as inequality. Firstly, many HNWIs describe wealth as the cause by pointing out that wealth concentration is a societal problem. One informant (HNWI 12), for example, problematizes wealth concentration by arguing that “wealth distribution is definitely something that I adhere to” in my investment decisions because “I just feel like opportunities are a little bit skewed at this point.” Further, the wealth owner problematizes wealth concentration by contrasting it with an equal society that is much more beneficial for all involved, as it ensures equal opportunities, i.e., “a much more balanced society is extremely beneficial for all”.

Secondly, HNWIs emphasize that ample financial resources may serve to tackle social problems. One wealth owner (HNWI 16) illustrates wealth as an important tool for social welfare promotion by the example of an investment strategy aimed at combating climate change and all its resulting societal consequences. According to this informant, investing wealth through this strategy serves “to bend emissions and create opportunities to generate land that we are able to move back towards a healthy planet.” In this regard, the strategy goes far beyond combating climate change by securing that “people are going to be less hungry, be better fed, have better sanitation, and all those things that potentially come with making better use of the resources we have”.

In sum, our empirical analysis of the interview data shows that HNWIs see wealth as both a cause of and an opportunity to solve societal problems. On the one hand, HNWIs localize the concentration of wealth as the cause of the unfair distribution of opportunities in society; on the other hand, they describe wealth as the central means of solving current social problems, such as the unfair distribution of resources. In Table 2, we provide further evidence of wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems.

Table 2.

Wealth as a cause and solution for societal problems.

Perception of personal responsibility towards society. The interviewed HNWIs deal in detail with the connection between wealth and the potential responsibility that comes with it and how this very connection affects them personally. Firstly, HNWIs often mentioned the issue of being guilty of being rich. For example, after being asked by the interviewer about the fairness debate around inherited wealth and first-generation wealth and how the respective generation and the family as a whole deal with this debate, one informant (HNWI 2) responded that “we know [about the fairness debate around inherited wealth], and it’s something that my mom, I think, makes a big effort of reminding us about.” Furthermore, the informant explicitly points out the feelings of guilt that come along with being wealthy: “but yes, I do think there’s a big element of unfairness there”.

Secondly, our data on HNWIs suggest that wealth obliges one to make a positive social contribution. The interviewees clearly express a personal desire to do something about the inequality in today’s world and the lack of social mobility. This includes straightforward measures such as the intention to redistribute financial resources but also to use one’s own capital to promote projects that increase social mobility. One wealth owner (HNWI 25) clarifies this further by pointing out that “there’s this fundamental discomfort with the inequality that exists in the world” and that driving the investment of wealth “at the portfolio level but also the deal level is this sense of how can we create more equality in the world”.

To summarize, the interviewed HNWIs see themselves, primarily because of their wealth, as bearing a personal responsibility to society. This sense of personal responsibility is based both on feelings of guilt, which originate from their own wealth, and on the conviction that wealth obliges one to solve social problems such as the increasing inequality between the rich and the poor. In Table 3, we provide further evidence of the perception of personal responsibility towards society.

Table 3.

Perception of personal responsibility.

4.2. Using Own Fortune to Generate Financial Profits

The interviewed SRI-oriented HNWIs expressed that they aim to use their own fortune for generating financial profits, as evidenced by the profit orientation of their sustainable investment activities. We found two aspects supporting this insight that we will detail in the following.

Financial return is essential. HNWIs generally regard SRI as a financial instrument that not only has a positive social impact but also generates an economic return. Firstly, this circumstance is shown by the aspect that SRI needs to pay off. One wealth owner (HNWI 34) illustrates the importance of making money with SRI by the example of impact investing, which can be understood as a synonym of SRI. This informant notes that people “confuse it [impact investing] with philanthropy” while instead “impact investing is about making a positive impact and make a lot of money”.

Secondly, HNWIs often consider their sustainable investing activities as a way of making a financial profit. Hence, wealthy sustainable investors see SRI as a tool to make some profit. For example, the following informant (HNWI 1) clarifies the importance of earning money as follows: “The argument is that we don’t want to lose money [with SRI]. We don’t want this to be an expense. We want to earn money, make investments that are profitable”.

In conclusion, our analysis indicates that the interviewed HNWIs conceive SRI as an investment vehicle to contribute to society and generate financial profits. In each case, financial gain is emphasized, for example, when HNWIs point out that SRI should help “make a lot of money” and serve as a tool to generate a financial surplus. In Table 4, we provide further evidence that financial return is essential.

Table 4.

Financial return is essential.

Profitability to enable the adoption of SRI. Profitability has often been expressed under the umbrella of building the field of sustainable investing. Many wealthy private investors mention the need to prove the established idea that SRI should be as equally profitable as traditional investments. This is, firstly, because HNWIs suggest that profit serves as a primary motive. One wealth owner (HNWI 31) points out that “the thesis of impact investing is that you can achieve the same returns.” Moreover, the informant states that the confirmation of this thesis is critical for whether investors go into impact investing at all: “at the performance of portfolios, there’s very little evidence. (…) If you say that to people, they’ll be like, ‘hell no, I’m not putting that money into impact’”.

Secondly, the interviewed SRI-oriented HNWIs consider profitability as a compelling argument to encourage the adoption of sustainable investment practices by third parties. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 32) explains this by the case of convincing the board of their own family office to adopt SRI: “I had to look at it from the perspective of where can I get some wins, where can I get the leverage going. And it’s honestly just about proving that we can make market returns or better”.

In sum, the analysis of the interview data suggests that HNWIs consider the financial profitability of SRI relevant for establishing the field of sustainable investing and for promoting its adoption among wealthy private investors in particular. This insight is grounded on the circumstances that profit motives dominate the investment behavior of HNWIs and that profitability is the most compelling argument for adopting SRI or not. In Table 5, we provide further evidence of profitability to enable the adoption of SRI.

Table 5.

Profitability to enable the adoption of SRI.

4.3. Family Sets Profit-Oriented Norms

Families and their members who surround the HNWIs set profit-oriented norms that the wealthy sustainable investors interviewed perceive as standards and expectations they must adhere to. Below, we detail two aspects of the insight that families demand financial profit and claim this demand toward SRI-oriented HNWIs.

Family upholds the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI. HNWIs repeatedly mention the relevance of their family members for their investments. Firstly, their family upholds the value of wealth preservation that is an essential guideline for them. Our data suggest, at least in the context of investing, that wealth preservation is the most prominent value in wealthy families. For example, in response to whether there are any particular values or principles regarding financial investments that the HNWI has adopted from their own family, the informant (HNWI 15) mentions values related to “wealth preservation” that many wealthy families have to “set up expectations for family members in order to access funds”.

Secondly, the interviewed HNWIs repeatedly point out that family members are skeptical towards SRI. Families are often unfamiliar with the underlying idea of SRI, of combining financial investment with a positive social and environmental contribution, and therefore cannot imagine how this would work. One wealth owner (HNWI 8) further explicates this skepticism by “an added level of skepticism that the family office brings whenever we put forth something with the knowledge that it is impact.” This informant locates this skepticism in the technical terms and expressions associated with impact investing, as “they (family office members) themselves put an added level of skepticism on the investments we put forward because of the impact investment terminology”.

In conclusion, our informants emphasize that their families uphold the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI. On the one hand, such wealth preservation provides the interviewed HNWIs with a basis for their value formation and presents a critical normative framework against which they align their investment behavior. On the other hand, families are skeptical about SRI and the associated sustainable investment behaviors because, according to the HNWIs interviewed, their family members are often unacquainted with SRI. In Table 6, we provide further evidence of the issue that the family upholds the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI.

Table 6.

Family upholds wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI.

SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family. HNWIs themselves often face the circumstance that their family does not see the point of linking their financial investments to socially and environmentally positive contributions. Firstly, this circumstance can be explained by the fact that there usually are family offices without any social welfare mandate. The following statement by a wealth owner (HNWI 15) illustrates that most family offices lack any mandate for making a positive social or environmental contribution as part of their investment activities: “I know many family offices, and I always ask if they have an impact mandate or something, and a lot of them still don’t”.

Secondly, SRI-oriented HNWIs mentioned that their families often uphold that they already are engaged in philanthropic activities and therefore do not see any need for SRI. Hence, family members traditionally consider philanthropy as sufficient. The extent to which this very attitude can hinder SRI illuminates an informant (HNWI 6) who is appropriately committed to such investments outside the family and its wealth because family members only focus on philanthropy, as explicated by the family foundation: “they (family members) have a very traditional sort of foundation setting. (…) So the foundation is purely about giving philanthropic capital, not capital but the income generated from it”.

To sum up, the analysis points towards the circumstance that HNWIs’ families do not see why striving for financial returns should link to a positive societal contribution. This insight reflects the fact that family offices, officially entrusted with managing the family’s assets, traditionally do not have a social welfare mandate. Moreover, the circumstance that family members traditionally consider philanthropy to be sufficient, where any economic activity is usually separated from social welfare engagement, supports the insight that SRI does not fall under their families’ purpose. In Table 7, we provide further evidence that SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family.

Table 7.

SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family.

4.4. Proving Profit to Conform with Family Norms

Our data shows that HNWIs are engaged in proving the economic profitability of SRI to conform with family norms, suggesting that a “good” investor is an economically successful investor. This, however, differs from the above-described striving for financial return in that HNWIs primarily aim for economic profit to prove their conformity with family norms. We detail the two aspects related to this insight below.

Profit to legitimize SRI to the family. HNWIs often mention financial success as a source of legitimacy. Firstly, the informants said that financial gains prove to the family a serious investment strategy. For example, an interviewed HNWI (HNWI 15) explicates how generating financial returns built the necessary approval from the family hedge fund for adopting an SRI strategy: “my hedge fund, this email I got was, ‘oh it (SRI) sounds just like charities, and no problem, you can be on the board’”. However, this wealth owner seeks to demonstrate that SRI is not charity, but allows for the generation of financial gains, to convince family members that SRI is a serious investment strategy: “they (members of the family hedge fund) approached me to be on the board, but it’s actually not okay like I want people to realize that it can be very profitable, and it is important for me to generate returns so that again you can prove this concept”.

Secondly, our interview partners render financial return and the proof of profitability as the vital reference point for family members and a known and appreciated measure for assessing individuals within the family. Suppose the individual HNWI can provide evidence that an investment decision generates enough profit. In that case, influential family members, such as the grandfather, acknowledge this as sufficient to let the individual (i.e., in our example here, the grandchild) proceed with their own ideas. It thus justifies the position of a capable, independent decision-maker. This is illustrated in the following statement by a wealth owner (HNWI): “I decided to talk to my grandfather, and I told him that I wanted to work with education and that it was something that would change the world. The only thing that he said was, ‘but how are you going to pay your bills?’”.

In a nutshell, the interviewed HNWIs indicate that they use financial success as a source for legitimizing SRI to their family members. This approach is explained on the one hand by the circumstance that HNWIs draw on economic profits to prove a serious investment strategy; for example, to receive approval from their family hedge fund for adopting an SRI strategy. On the other hand, financial success is the vital reference point for assessing family members and thus for whether an individual family is considered appropriately competent to invest the family capital in SRI. In Table 8, we provide further evidence of financial success as a means of legitimization within the family.

Table 8.

Profit to legitimize SRI to the family.

Making profits to achieve recognition. SRI-oriented HNWIs strive to gain recognition as investors, for example, from their families, by making financial profits. Firstly, next-generation wealth owners born into their societal position point out that they need to find ways to show that their actions are credible. A ubiquitous way to achieve this goal is profit because financial gains increase credibility. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 5) describes the importance of bringing proof to the family as a financially successful investor using the following comparison: “you’re expected to shape your life so that you can become a good steward (of your inherited wealth), versus, ‘oh I have this, great, I just found out, so I don’t have to work as hard, I don’t have to find a job, I can just rely on my family’”. Thus, recognition in the family is obtained by distinguishing oneself as a financially successful steward of inherited wealth.

Secondly, because wealthy sustainable investors often consider making profits essential for achieving recognition, they usually suggest that the social benefit is secondary to profit. HNWIs often do not show their ambition to prove the impact case of SRI to meet the initial intention of a social or environmental purpose. One interviewed HNWI (HNWI 31) illustrates this by pointing out that the measurement of any positive social or environmental impact merely distracts from the central goal of making a financial profit: “this whole discussion about impact measurement, I think, is diverting maybe too much resources from thinking about how to make this financial success first”. Hence, in the case of SRI engagement, the social benefit is systematically subordinated to financial profit.

In summary, our analysis of the interview data suggests that SRI-oriented HNWIs strive to gain recognition as investors from their family members by making financial profits. This insight is evidenced first by HNWIs aligning their investments primarily with financial performance to make their actions more credible, and second by making the measurement of any positive societal impact secondary to proving financial performance. In Table 9, we provide further evidence for the role of making profits to achieve recognition.

Table 9.

Making profits to achieve recognition.

4.5. Other SRI-Oriented HNWIs Provide Confirmation

The HNWIs in our data frequently pointed out other SRI-oriented HNWIs whom they admire and who serve as a reference for them. We detail two aspects related to this insight in the following.

Sharing one’s own goals and vision with other HNWIs. Our informants often praise the community of other SRI-oriented HNWIs and how they thrive on being surrounded by like-minded private investors who share their goals and visions. Firstly, other SRI-oriented HNWIs are necessary for a wealthy sustainable investor to exchange ideas about tackling specific issues from an SRI perspective. An investment advisor (Expert 12) who regularly consults with HNWIs further elaborates on this very issue by pointing out the relevance of “a community of like-minded investors”. Such a community allows SRI-oriented HNWIs “to deep-dive into a specific issue area” and how to “tackle that from a sustainable investing standpoint”.

Secondly, our informants frequently emphasize the importance of learning from other HNWIs. One HNWI (HNWI 25) explains the importance of learning from others in the context of a global network of impact investors as “being part of a more global community of impact investors was extremely helpful.” According to the informant, this worldwide network of SRI-oriented HNWIs derives its importance, particularly in representing a community, “from that you can learn”.

To sum up, the interviewed HNWIs point out the relevance of sharing their goals and visions with other SRI-oriented wealthy private investors. This relevance stems from the fact that like-minded investors provide an individual HNWI with the opportunity to share ideas on approaching specific issues from an SRI perspective and learn more about SRI from other HNWIs. In Table 10, we provide further evidence for the role of sharing one’s own goals and vision with other HNWIs.

Table 10.

Sharing goals and vision with other HNWIs.

A community of values with other SRI-oriented HNWIs. In contrast to their families, other HNWIs do not demand anything from our informants. While family members claim their demands for a financial profit, other SRI-oriented HNWIs do not make any demands, either in terms of economic gain or contribution to social welfare. Firstly, this becomes evident by the circumstance that actual SRI investment skills are irrelevant to participation. One wealth owner (HNWI 26) accordingly points out that every HNWI is welcome to the community of SRI-oriented HNWIs regardless of where the person is on the SRI journey: “it’s very nice to be welcomed by a group that says, ‘if you want us to support you on your journey,’ that term is used a lot, the impact journey that we’re on here”. Thereby, it is more about experiencing the journey toward making a positive social impact with a group of like-minded SRI-oriented HNWIs than actually about achieving the goal of creating a positive impact. “I don’t feel as pressed to come up with something perfect, but rather to have a full journey with a group of like-minded individuals” (HNWI 26).

Secondly, our informants frequently mentioned that sharing similar values connects one to another. One informant (HNWI 10) clarifies the importance of being surrounded by like-minded HNWIs who share the same goals and visions and how such a community serves as a source for inspiration and support because “you will feel alone, and also, you will not be able to scale if you are alone (…). And here comes a certain belief, that of conviction.” The shared set of values among SRI-oriented HNWIs creates a sense of community, which is a crucial source of guidance for the individual wealth owner. In fact, according to the same informant, “it’s always important to be a part of a community that you share with a grandiose ambition”.

In conclusion, our analysis of the interview data indicates that other SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a community of values that does not impose concrete requirements on an individual HNWI, neither in terms of financial gain nor of positive social impact. Namely, on the one hand, whether an individual HNWI has SRI skills and thus actual knowledge of how to link economic and social aspects is irrelevant to belonging to the community of SRI-oriented HNWIs. On the other hand, as a community of values that does not impose any concrete requirements on an individual HNWI, it is mainly about sharing the same goals and visions. In Table 11, we provide further evidence of a community of values with other SRI-oriented HNWIs.

Table 11.

A community of values with other SRI-oriented HNWIs.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Influence of Reference Groups on the Investment Behavior of SRI-Oriented HNWIs

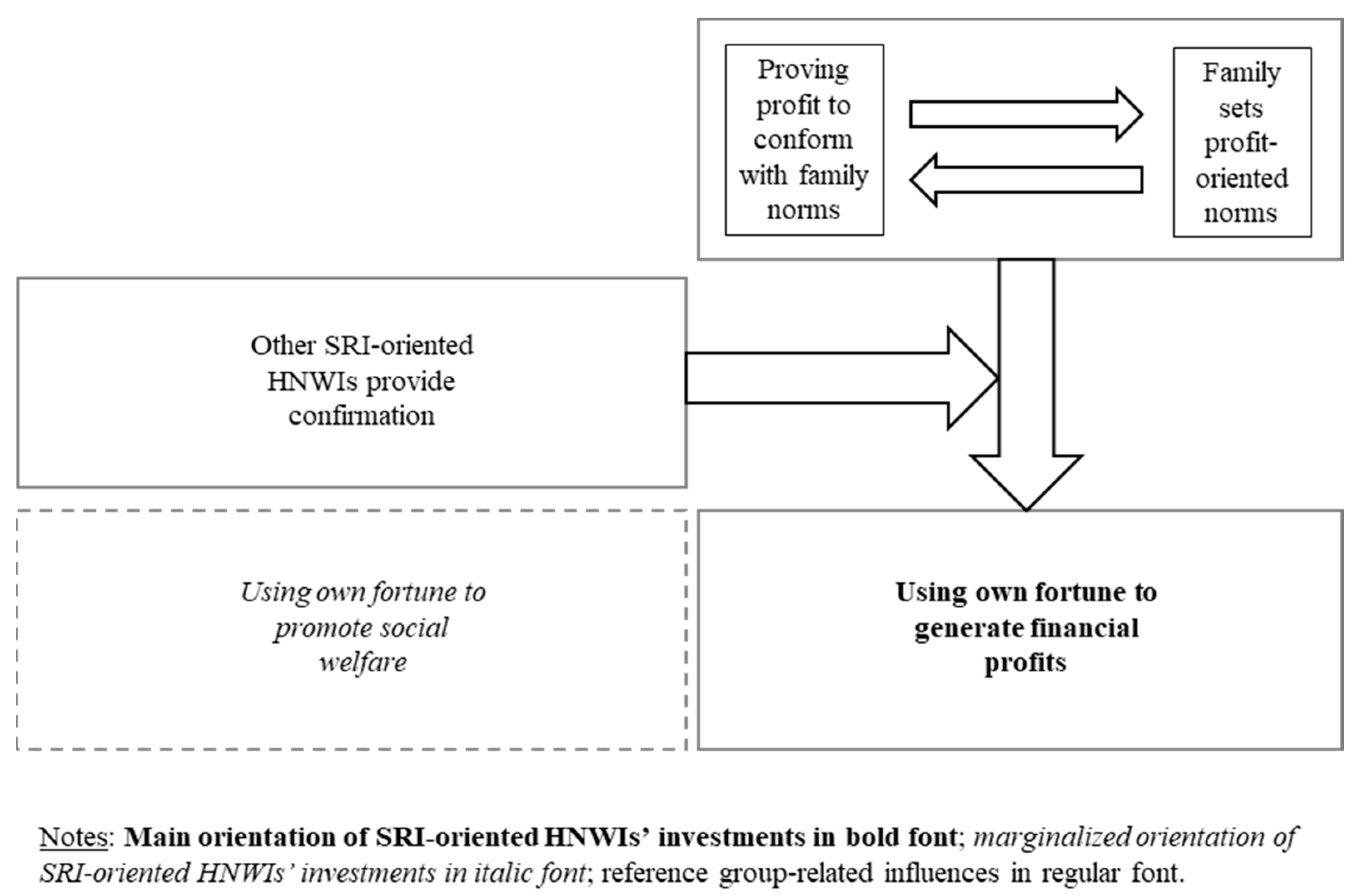

While we know little of the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs, reference group theory suggests that such behavior is centrally dependent on their identification with and comparison to a respective reference group. For this reason, we have set the objective of developing knowledge on the influence of reference groups on the SRI engagement of HNWIs. Based on an inductive qualitative investigation of 55 semi-structured interviews with HNWIs and industry experts, we developed a framework to explain how reference groups influence the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs. Our framework indicates that the family directly influences and other SRI-oriented HNWIs indirectly influence SRI-oriented HNWIs towards generating financial profits in their investments at the expense of social welfare considerations. On the one hand, the family serves as a normative reference group that upholds the economic profit motive and directly urges HNWIs to make financial gains from their investments at the expense of social welfare. On the other hand, other SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a comparative reference group that shares the same values but does not impose any concrete requirements on social welfare performance. This indirectly influences SRI-oriented HNWIs to subordinate social concerns to financial profits. Figure 2 provides an overview of our explanations.

Figure 2.

How reference groups influence the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs.

Our framework shows that SRI-oriented HNWIs are open to the idea of combining social welfare and economic aspects in their investments (see the two boxes with dashed and solid lines at the bottom of Figure 2). On the one hand, they intend to use their own fortune to promote social welfare. SRI-oriented HNWIs regard wealth both as a cause for the imbalance between rich and poor and a solution to overcome this very inequality. The latter explains the personal responsibility HNWIs ascribe to contributing to social welfare by placing their wealth into SRI. On the other hand, HNWIs intend to use their own fortune to generate financial profits. They regard financial return as essential, considering SRI as a financial vehicle to contribute to social welfare but also to make an economic profit. Moreover, HNWIs argue that financial gain serves the cause of SRI, considering profitability as a prerequisite for spreading SRI amongst mainstream investors.

However, while SRI-oriented HNWIs are open to the idea of combining social welfare and economic aspects in their investments, they strive towards making a financial profit at the expense of social welfare considerations even though they already hold great fortune (see the box with the solid line at the bottom of Figure 2). The influence of two particular reference groups explains this profit-oriented investment behavior of wealthy private investors.

First, a push-and-pull effect between the family setting profit-oriented norms and the HNWIs proving profit to conform with family norms directly promotes SRI-oriented HNWIs’ ventures for financial return (see the box at the top right and the corresponding vertical arrow in Figure 2). The push consists of the family that serves as a normative reference group [23], setting profit-oriented norms that wealthy sustainable investors perceive as standards and expectations they must adhere to. Family members tend to have traditional investor mindsets, suggesting that lent or invested capital needs to generate financial profits to compensate the risk that the investor takes by giving the money away. From this normative group’s perspective, the only reasonable explanation for taking such a risk is a financial profit. Consequently, the family upholds the value of wealth preservation and skepticism against SRI and suggests that SRI does not fall within the purpose of the family. The pull is that SRI-oriented HNWIs strive for financial profit to conform with the norms of their families, upholding the importance of economic profits. They try to make profitable investments to legitimize SRI to their family members and to achieve their recognition. However, by these activities, SRI-oriented HNWIs reinforce and further consolidate family norms, countering the underlying idea of SRI, which brings together financial profits and social welfare (e.g., [6]).

Second, other SRI-oriented HNWIs provide confirmation and thereby indirectly promote SRI-oriented HNWIs’ ventures for financial profits (see the box in the middle and the corresponding horizontal arrow in Figure 2). These like-minded individuals allow SRI-oriented HNWIs to share goals and vision with their peers and serve as a community of shared values. Within this group, an SRI-oriented HNWI finds validation for own ideas of using financial capital for social welfare and acceptance that the consideration of ESG criteria is appropriate and reasonable. In this vein, other SRI-oriented HNWIs build a comparative reference group, as they serve as a standard or checkpoint which the individual uses to make judgments [23]. However, this reference group does not enforce any standards, as can be seen, for example, in that actual SRI investment skills are irrelevant for membership. Consequently, those judgments are decoupled from the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs. For this reason, the comparative reference group has at least an indirect positive effect on profit-oriented investing by reinforcing the influence of the normative reference group on the profit-seeking of SRI-oriented HNWIs.

5.2. Contributions to the Literature

Our study adds to SRI research. To achieve sustainable development, we need a shift of traditionally invested assets into SRI. HNWIs hold a vital role in this shift, controlling nearly half of global wealth [3]. However, we know little about wealthy sustainable investors [16,17] and SRI-oriented HNWIs [18,19]. To understand whether, how, and to what extent HNWIs engage in sustainable investing, we need to go well beyond whether or not SRI is more profitable than traditional financing because the former brings together financial profits and social welfare [6,9]. We showed that SRI-oriented HNWIs use their fortune to generate economic gains at the expense of social welfare in their investments and unpacked the reasons behind their profit-oriented investment. While they support the idea of mobilizing their wealth to promote social welfare, they let this goal fall short because of reference groups that encourage them to use their wealth to generate financial profits, even though they already hold great fortune. The insight that the SRI engagement of HNWIs is, in effect, primarily profit-driven due to the direct influence of family members and the indirect effect of other SRI-oriented HNWIs, suggests that such engagement could contribute less to social welfare and more to further boosting wealth inequality. This finding is accentuated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has again exacerbated existing wealth inequalities [61].

We further contribute to the reference group theory literature. As mentioned above, the literature differentiates two types of reference groups [22,23,24]. While normative reference groups establish and enforce standards considered norms, comparative reference groups serve individuals as a point of reference in making evaluations or comparisons without the evaluation of the individual by others in the group. By focusing on how different reference groups influence the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs, we can comparatively show how different reference groups each affect the profit and welfare orientation of wealthy investors. This lets us derive an exciting finding for reference group theory. In the case of conflict, normative reference groups suppress the beliefs, values, and perspectives of the comparative reference groups. Suppose that the reference group does not enforce its values or does not even seek to do so. In that case, this space is occupied by a reference group that does, while the comparative reference group at least indirectly supports the standards of the normative reference group. This insight implies the different spheres of influence of normative and comparative reference groups. In addition, understanding how different reference groups influence values, which then, in turn, shape the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs, echoes the relevance of values for studying contexts where, as in the case of SRI, it is a matter of conceptualizing the interactions between economic issues and social aspects [46,62].

5.3. Contributions to Practice

The knowledge gained into the influence of reference groups on the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs demonstrates that it is critical for market participants to be highly aware of the specific social setting that their HNWI clients or constituents are in when they receive their messaging. That is because the social setting in that moment will serve as a critical contextual aspect in determining what types of arguments about SRI—financial or social welfare arguments—will resonate more or be more helpful for HNWIs to move ahead with an investment decision. More specifically, in a shared ownership setting, as in families, financial arguments are more likely to support an investment decision. In contrast, social welfare arguments are more likely to support an investment decision in the setting of an SRI-interested HNWI community.

For the managers and members of communities of SRI-interested HNWIs, our findings suggest that to drive the primary goal of social welfare more effectively and to overcome the dominance of the financial performance-seeking of other family members, it might be crucial to put more specific emphasis within their community on the actual achievement of social goals, to drive more specific goal-setting in that regard, or to set certain standards and minimum requirements within their community.

Our research insights point out that mobilizing private wealth, at scale, for a positive social impact requires a deep understanding of the underlying social contexts that HNWIs are embedded in and which substantially influence their investment decision-making. Specifically, for the crucial intermediaries of banks and SRI funds, our findings indicate that to mobilize private wealth into SRI products, it is relevant for financial intermediaries to carefully consider and shape the social settings in which their HNWI communication activities occur. Depending on the settings of their specific activity, either financial or social welfare arguments might impede, rather than support, unlocking the substantial latent demand for their SRI products. It is these social setting considerations, and them not being considered carefully, that so far might have been the crucial stumbling block for SRI in private wealth management.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Our research is not without limitations—many of which are linked to its qualitative nature (see [63]). However, we believe that it opens up a broad range of future research opportunities that can add nuance and clarity to the possibilities and limitations of HNWIs’ contribution to a shift of traditionally invested assets into SRI and the influence of different reference groups in this process. Our qualitative research strategy allowed for more accurate insights into the context of SRI-oriented HNWIs’ investment behaviors, which would have been challenging to obtain through quantitative approaches. However, this also means that qualitative research develops generalizations that “are often less parsimonious because of the large number of variations possible and the difficulty of predicting which ones will occur and why” [64] (p. 703). Future research could use a quantitative method to test the generalization of our study statistically and enrich the boundary conditions of our work—for instance, linked to geographic or personal aspects.

While our data allowed us to theorize the influences of different reference groups on the investment behavior of SRI-oriented HNWIs, more research is needed to examine the gradual transition of these influences and potential shifts in them over time. Longitudinal studies could further decipher the temporal dynamics behind the influences of reference groups on individual investment behaviors and any measures individual investors take to counter the influence of third parties. Examining the influence of such groups over different points in time could explain how and why a particular group manages to assert itself over others, what the associated influence strategies are, and why they are particularly assertive with the respective investors. Such research could also reveal whether, how, and why investors evade the influence of third parties and what the respective preconditions are for escaping the influence of a particular reference group (e.g., social embeddedness, individual strategies against influence). In addition, future research could examine the individual capabilities of private investors who positively impact social welfare through their investments, even in a context where financial gain is preferred over social welfare engagement.

6. Conclusions

A reference group theory perspective suggests that SRI-oriented HNWIs’ investment behavior is shaped by their identification with and comparison to reference groups. To close the existing knowledge gap regarding HNWIs’ SRI engagement, we adopted a qualitative interview approach to examine how reference groups influence the investment behaviors of SRI-oriented HNWIs. We found that the family members of SRI-oriented HNWIs form a normative reference group that prioritizes financial returns and directly shapes HNWIs to subordinate social concerns to financial profits. Our study also indicated that fellow SRI-oriented HNWIs serve as a comparative reference group that does not impose any concrete requirements on social welfare performance, indirectly influencing SRI-oriented HNWIs to generate financial gains from their investments at the expense of social issues. Our scholarly insights contribute to the SRI literature and reference group theory and have practical implications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; methodology, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; software, D.R. and A.K.; validation, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; formal analysis, D.R. and A.K.; investigation, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; resources, D.R. and F.P.; data curation, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, D.R., F.P. and A.K.; visualization, D.R. and F.P.; supervision, not applicable; project administration, D.R.; funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- SSF. Swiss Sustainable Investment Market Study 2019; Swiss Sustainable Finance: Zurich, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UNCTAD. World Investment Report 2014—Investing in the SDGs: An Action Plan; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shorrocks, A.; Davies, J.; Lluberas, R. Global Wealth Report 2021; Credit Suisse: Zurich, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and Financial Performance: Aggregated Evidence from More than 2000 Empirical Studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Revelli, C.; Viviani, J.-L. Financial Performance of Socially Responsible Investing (SRI): What Have We Learned? A Meta-Analysis. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2015, 24, 158–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, D. Time and Business Sustainability: Socially Responsible Investing in Swiss Banks and Insurance Companies. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 1410–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Heeb, F.; Paetzold, F.; Busch, T. Beyond Returns: Investigating the Social and Environmental Impact of Sustainable Investing. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kölbel, J.F.; Heeb, F.; Paetzold, F.; Busch, T. Can Sustainable Investing Save the World? Reviewing the Mechanisms of Investor Impact. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 554–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peifer, J. The Institutional Complexity of Religious Mutual Funds: Appreciating the Uniqueness of Societal Logics. Res. Sociol. Organ. 2014, 41, 339–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, J.H.; Hirschmann, M.; Fisch, C. Which Criteria Matter When Impact Investors Screen Social Enterprises? J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.; Holzhauer, H.; Dai, Y. Finance or Philanthropy? Exploring the Motivations and Criteria of Impact Investors. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017, 13, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollenda, P. Financial Returns or Social Impact? What Motivates Impact Investors’ Lending to Firms in Low-Income Countries. J. Bank. Financ. 2021, 106224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, J.-L.; Maurel, C. Performance of Impact Investing: A Value Creation Approach. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2019, 47, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda-Tarrazona, I.; Matallín-Sáez, J.C.; Balaguer-Franch, M.R. Measuring Investors’ Socially Responsible Preferences in Mutual Funds. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzmark, S.M.; Sussman, A.B. Do Investors Value Sustainability? A Natural Experiment Examining Ranking and Fund Flows. SSRN Electron. J. 2019, 74, 2789–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedl, A.; Smeets, P. Why Do Investors Hold Socially Responsible Mutual Funds? J. Financ. 2017, 72, 2505–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hafenstein, A. Nachhaltigkeitsinformationen in Der Anlageentscheidung—Eine Analyse Der Nicht-Professionellen Anleger; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold, F.; Busch, T. Unleashing the Powerful Few: Sustainable Investing Behaviour of Wealthy Private Investors. Organ. Environ. 2014, 27, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schrader, U. Ignorant Advice—Customer Advisory Service for Ethical Investment Funds. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2006, 15, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, E.M.; Chatman, E.A. Reference Groupt Theory with Implications for Information Studies: A Theoretical Essay. Inf. Res. 2001, 6. Available online: http://InformationR.net/6-3/paper105.html (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- French, J.R.; Raven, B. The Base of Social Power. In Studies in Social Power; Cartwright, D., Ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbot, MI, USA, 1959; pp. 150–167. [Google Scholar]

- Hyman, H.H. The Psychology of Status. Arch. Psychol. 1942, 269, 5–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, H.H. Two Funtions of Reference Groups. In Readings in Social Psychology; Swanson, G., Newcomb, T., Hartley, E., Eds.; Holt: New York, NY, USA, 1952; pp. 410–414. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif, M. An Outline of Social Psychology; Harper & Brothers Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Bettis, R.A.; Gambardella, A.; Helfat, C.; Mitchell, W. Qualitative Empirical Research in Strategic Management. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á. Sustainable Development and the Financial System: Society’s Perceptions About Socially Responsible Investing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 410–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, B.J. Keeping Ethical Investment Ethical: Regulatory Issues for Investing for Sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 555–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheah, E.-T.; Jamali, D.; Johnson, J.E.V.; Sung, M.-C. Drivers of Corporate Social Responsibility Attitudes: The Demography of Socially Responsible Investors. Br. J. Manag. 2011, 22, 305–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J.; Nordvall, A.-C.; Isberg, S. The Information Search Process of Socially Responsible Investors. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2010, 15, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, J. Segmenting Socially Responsible Mutual Fund Investors: The Influence of Financial Return and Social Responsibility. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009, 27, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Juravle, C.; Hedesström, T.M.; Hamilton, I. The Heterogeneity of Socially Responsible Investment. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, J.; Nilsson, J. Conflicting Intuitions about Ethical Investment: A Survey among Individual Investors; Sustainable Investment Research Platform; Mistra: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Eurosif. HNWI & Sustainable Investment 2012; Eurosif: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Revelli, C. Socially Responsible Investing (SRI): From Mainstream to Margin? Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2017, 39, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennebog, L.; Ter Horst, J.; Zhang, C. Socially Responsible Investments: Institutional Aspects, Performance, and Investor Behavior. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 1723–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickert, C.; Risi, D. Corporate Social Responsibility; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, S. Beyond the Business Case for Social Responsibility. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2020, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juravle, C.; Lewis, A. Identifying Impediments to SRI in Europe: A Review of the Practitioner and Academic Literature. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 17, 285–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeis, J.; Albert, C.R.; Acuff, F.G. Reference Group Theory: A Synthesizing Concept for the Disengagement and Interactionist Theories. Int. Rev. Sociol. 1971, 1, 66–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, J.K.; Beeghley, L. The Infleunce of Religion on Attitudes Towars Nonmarital Sexuality: A Preliminary Assessment of Reference Group Theory. J. Sci. Study Relig. 1991, 30, 45–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R. Role-Taking, Role Standpoint, and Reference-Group Behavior. Am. J. Sociol. 1956, 61, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R.; Kitt, A. Contributions to the Theory of Reference Group Behavior. In Continuities in Social Research: Studies in the Scope and Method of “The American Soldier”; Merton, R.K., Lazarfeld, P., Eds.; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Gould, J.; Kolb, W.L. A Dictionary of the Social Sciences; Free Press Glencoe: New York, NY, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Kraatz, M.S.; Flores, R. Reinfusing Values. In Institutions and Ideals: Philip Selznick’s Legacy for Organizational Studies; Kraatz, M.S., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bradford, UK, 2015; pp. 353–381. [Google Scholar]

- Risi, D.; Vigneau, L.; Bohn, S. The Role Values Play for Agency in Institutions. Proceedings 2019, 2019, 10558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, D. Institutional Research on Business and Society: Integrating Normative and Descriptive Research on Values. Bus. Soc. 2020, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudon, R. L’Inégalité des Chances; Armand Colin: Paris, France, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Boudon, R. Education, Opportunity and Social Inequality; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Piketty, T. Theories of Persistent Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility. In Handbook of Income Distribution; Atkinson, A.B., Bourguignon, F., Eds.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; pp. 430–476. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Mcmanus, S.E. Methodological Fit in Management Field Research. AMR 2007, 32, 1246–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gephart, R.P., Jr. Qualitative Research and the Academy of Management Journal. Acad. Manag. J. 2004, 47, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Nag, R.; Gioia, D.A. From Common to Uncommon Knowledge: Foundations of Firm.Specific Use of Knowledge as a Resource. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 421–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallen, B.L.; Eisenhardt, K.M. Catalyzing Strategies and Efficient Tie Formation: How Entrepreneurial Firms Obtain Investment Ties. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 35–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gioia, D.A.; Chittipeddi, K. Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gioia, D.; Corley, K.; Hamilton, A. Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, D.; Wickert, C. Reconsidering the ‘Symmetry’ Between Institutionalization and Professionalization: The Case of Corporate Social Responsibility Managers. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 54, 613–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locke, K.D. Grounded Theory in Management Research; Sage: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.G. Fitting Oval Pegs Into Round Holes: Tensions in Evaluating and Publishing Qualitative Research in Top-Tier North American Journals. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldin, I. How Rising Inequalities Unfolded and Why We Cannot Afford to Ignore It. Available online: https://theconversation.com/covid-19-how-rising-inequalities-unfolded-and-why-we-cannot-afford-to-ignore-it-161132 (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Paetzold, F.; Busch, T.; Chesney, M. More than Money: Exploring the Role of Investment Advisors for Sustainable Investing. Ann. Soc. Responsib. 2015, 1, 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.; Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, A. Strategies for Theorizing from Process Data. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 691–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).