Abstract

Organizations grow and excel with knowledge sharing; on the other hand, knowledge hiding is a negative behavior that impedes innovation, growth, problem solving, and timely correct decision making in organizations. It becomes more critical in the case of teaching hospitals, where, besides patient care, medical students are taught and trained. We assume that negative emotions lead employees to hide explicit knowledge, and in the same vein, this study has attempted to explain the hiding of explicit knowledge in the presence of relational conflicts, frustration, and irritability. We collected data from 290 employees of a public sector healthcare organization on adopted scales to test conjectured relationships among selected variables. Statistical treatments were applied to determine the quality of the data and inferential statistics were used to test hypotheses. The findings reveal that relationship conflicts positively affect knowledge hiding, and frustration partially mediates the relationship between relationship conflicts and knowledge hiding. Irritability moderates the relationship between relationship conflicts and frustration. The findings have both theoretical and empirical implications. Theoretically, the study tests a novel combination of variables, and adds details regarding the intensity of their relationships to the existing body of literature. Practically, the study guides hospital administrators in managing knowledge hiding, and informs on how to maintain it at the lowest possible level.

1. Introduction

Knowledge is one of the core resources that enables organizations to grow and gain a sustainable competitive advantage to ensure their survival and sustainability. In the past few years, extensive investigations have been conducted within the fields of organizational behavior (OB) and human resource management (HRM) to determine why workers share knowledge [1,2] or deliberately hide their knowledge [3,4]. These studies have additionally examined numerous structural challenges and practices intended to foster knowledge sharing behavior, and tried to find ways to promote knowledge sharing and also the reasons behind knowledge hiding [5,6]. The study of knowledge in an organizational context has deliberately focused on information sharing processes [3,7,8]. Despite these efforts, the hiding of knowledge among employees continues to increase, and has become pervasive [9]. Knowledge hiding behavior is characterized as the “intentional concealment of knowledge requested by another individual” [3,10]. Besides predictors and arguing for the effects of information sharing, research on knowledge hiding will aid organizations in lessening deliberate hiding [11,12].

Hiding knowledge has a detrimental effect on the work. The reasons for hiding knowledge have not been well explored. Knowledge hiding means the planned hiding or withholding of knowledge once requested by another person [3,4]. This kind of behavior has three related aspects and dimensions. Firstly, evasive hiding is identified as a condition where “the hider provides incorrect information or misleading promise of a complete answer in the future, even though there is no intention to provide this”, and secondly, workers who feign naivety have no intention of helping, and hide their knowledge by playacting and pretending they do not understand what the requester wants [10,13,14]. When hiding in a subtle manner, that is, rationalized hiding, workers clarify their inability to provide the required knowledge either by saying that they are incapable of providing the requested knowledge or by blaming others [3,10]. Numerous predictors have been considered and examined by many approaches related to the functioning of knowledge hiding, such as complex information and information-sharing climates, and the notion of distrust [15,16]. Despite this, more work is needed on the antecedents that have not been properly examined. As such, Shrivastava and Pazzaglia [17] have suggested future analyses to spot the triggering events of knowledge hiding behavior. In the same way, Bavik [18] suggested that it might be useful to research the antecedents of knowledge hiding. Semerci [9] further suggested to examine the predicting role of relationship conflicts in knowledge hiding.

There is little evidence on the mechanisms that lead towards knowledge hiding. Škerlavaj and Connelly [19] focused on further research to recognize mediators to explain the mechanism of knowledge hiding.

Furthermore, Huo and Cai [20] studied why individuals hide knowledge differently, and how negative emotions affect knowledge hiding. Moreover, Semerci [9] suggested looking at why people practice knowledge hiding, and the means and tactics by which companies interfere with and limit the undesirable effects of hiding knowledge.

Serenko and Bontis [21] recommended researching personality type as a moderator between two individuals in a team. Additionally, to fill up the research gap, as stated above, we have further explore the references in [3], which delivered future research instructions to discover the dispositional moderators of knowledge hiding, such as trait irritability. Issac and Baral [22] suggest that future scholars should dig deep regarding the moderators that may affect the relationship between subsequent compensatory work behavior, emotional experience, and knowledge hiding. Further Škerlavaj and Connelly [19] clarified the relation using Affective Event Theory to explain the mechanism of hiding explicit knowledge.

Previous studies have sought to develop a research model that integrates motivational characteristics [16,23], the big five personality types [12], and leadership styles that influence knowledge hiding [24]. We assume that one of the major causes of knowledge hiding is relationship conflict, which creates aggressiveness in the personality and eventually leads to knowledge hiding. We also assume that frustration bridges the relationship between relational conflicts and knowledge hiding. Our model also contains irritability as a moderator between relationship conflict and frustration. This model is unique in its combination, and the results of testing this model offer valuable additions to the existing body of literature.

Furthermore, we present a summary of the recent literature to further highlight the novelty of the present study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of relevant literature.

In summary, there is greemment in the literature about the adverse effects of knowledge hiding on organizational competitiveness and overall organizational effectiveness. Extenstive studies have been carried out to explain the causes and consequences of knowledge hiding, of which some have been presented in the literature review section and Table 1. Khowledge hiding is the consequence of individual-level, team-level and organizational-level factors. Researchers agree that negative emotions cause employees to incline towards knowledge hiding. Ethical leadership, social capital, distrust, workplace incivility, workplace ostracism, openness to learning, employee cynicism, conflict, social exchange, neuroticism, job insecurity, and history of reciprocity have been identified as some of the causes of knowldeg hiding. Conflict has been idenfided as a potential factor in knowledge hiding; however, this factor has not been investigated in hospital settings and in the context of underdeveloped countries. The contexts wherein such studies have been carried out are different from the context at hand in terms of resources, culture, preferences, structures, and behavior, and the findings of such studies may not be generalized to this context. Apart from this, our study model contains frustration as a mediating variable and irritability as a moderating variable to explain knowledge hiding, which is a novel finding to the best of our knowledge. Thus the context and organization in which we tested the model are well-justified, and have theortical and practical significance.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

Affective Event Theory (AET) [36] has been used to provide a theoretical basis for this study. This theory explains that there are positive and negative occurrences in the workplace that can affect the emotions of employees, and consequently employees behave accordingly. Hence, if AET is paralleled to other theories that try to forecast and describe behaviors in the workplace, then the above-mentioned theory emphasizes the role played by particular events in the workplace (disturbances or enrichments, or both), along with their effects (either positive or negative impacts) on the behavioral responses to both events and emotions in work settings [36,37].

As cited in different research papers where AET is used, the basics of this theory are supported empirically in various studies [38,39], and so this study also employs AET for explaining knowledge hiding behavior. Specifically, we argue that relationship conflict, which explains the incompatibilities among team members and is expanded to social tensions, frictions, and relationship conflicts (event), has direct effects on the employees’ ways of behaving. In the same way it is possible to persuade team members to reposnd with frustration (emotional reaction) to negative events in the workplace, which subsequently provokes team members’ knowledge hiding behaviors (behavioral reaction). The significance of these links or correlations depends on facets of the team members’ personality or disposition [40], and in our case it depends highly on irritability. By definition, individuals with high irritability are likely to show aggressive behaviors very often [41]. Irritability is defined as a lowered threshold for experiencing anger, which can lead to aggression and impairment [42,43,44]. The significant role of irritability in the link between offense and practical offensiveness (personality trait) strengthens the relationship between the conflict (event) and frustrations (emotional reaction), which leads to knowledge hiding (behavioral outcome) [45]. Irritability (personality trait), as a moderator on the first path, is more appropriate givent that, whenever there is relationship conflict, the highly irritable person tends to be more frustrated, and the more they become frustrated, the more they are inclined towards knowledge hiding.

2.1. Definition of Variables

2.1.1. Relationship Conflict

The concept explains the interpersonal incompatibilities among team members, which typically includes tensions and annoyance among members within a group [46].

2.1.2. Frustration

Feeling upset or annoyed as a result of being unable to change or achieve something. It is an emotional response to negative work events [47].

2.1.3. Irritability

Current definitions of irritability include proneness to anger, increased sensitivity to provocation, and increased likelihood of behavioral outbursts that may or may not include aggressive behaviors [43,48].

2.1.4. Knowledge Hiding

Knowledge hiding refers to planned hiding or withholding explicit knowledge once requested by another person [49].

2.2. Hypotheses

Conflict is a typical situation in organizations, and it is by all accounts going to turn out to be increasingly serious later on [9]. Conflict shapes proficient practices, social influences, and some other deliberate practices. Relationship conflict is identified with relational stress, erosions, and hatred [46,50]. Hence, the goal is to inspect, in the light of the conflict, the predecessors of knowledge hiding practices.

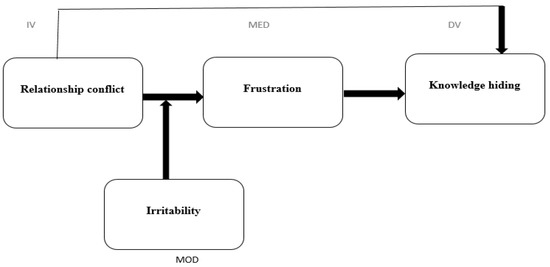

The idea of relationship conflict clarifies the contrary qualities among peers, which normally include enmity, strain, and irritation among team members, as cited in [51]. The impact of relationships with negative feelings will create disagreements between colleagues, interrupting obligations and tasks, and this may reduce the satisfaction of individuals in a team [52,53], limiting group capacities and group practices, the communication of sentiments, and organizational commitment. Keeping in view these facts, we propose the following hypotheses, which have also been shown schematically (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic view.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Employees will be more inclined towards knowledge hiding when they experience relationship conflict.

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Employees will feel frustrated when they face relationship conflict.

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Employees having frustration will be inclined towards knowledge hiding.

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

Frustration will play a mediating role between relationship conflicts and knowledge hiding.

Hypothesis 5 (H5).

The relationship between relational conflicts and frustration will be positively moderated by irritability.

3. Methods

The study is quantitative and explanatory in nature. A survey design has been used to collect data. Data were collected from a public sector hospital with more than three thousand employees. Questionnaires were administered to 500 randomly selected employees and 290 questionnaires were included for analysis, which was complete in all respects. A simple random sampling technique was used to ensure sample representation. Thus we obtained a combined list of doctors, nurses, and paramedics at the hospital as a sample frame that consisted of 1830 employees. A sample of 500 subjects was randomly selected from the sample frame for the administration of survey questionnaires.

Approval for data collection was obtained from the medical superintendent of the hospital, and informed consent was obtained from the respondents for participation in the survey voluntarily. Approval was also obtained from the Ethical Review Committee of Lahore Leads University.

A time-lagged design was followed with questionnaires distributed within the three sections, as indicated by the three time-lags, and data were gathered in a similar manner. At Time 1, data related to relationship conflict and the moderator (irritability) were extracted; at Time 2, the underlying mechanism (frustration) was estimated from a similar respondent, and outcome (Knowledge hiding) was determined at Time 3. All the constructs were self-reported. The surveys each contained an ID to trace the same representative between Time 2 and Time 3. The time interval date was additionally determined to evaluate the gap in each delay appropriately; 500 surveys were distributed, out of which around 290 were returned, comprising a response of about 58%.

3.1. Measures

3.1.1. Knowledge Hiding

We evaluated knowledge hiding with 12 items [3]. To keep away from social allure predispositions, we underscored that it is ordinary for members to differ in their reactions, and that it is not generally conceivable or desirable for workers to share knowledge transparently with colleagues. A 12-item questionnaire was used to quantify knowledge hiding, utilizing a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.1.2. Relationship Conflict

A slightly changed form of Jehn’s [46] four-item scale was utilized to evaluate relationship conflict. Workers were approached to give responses utilizing a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

3.1.3. Frustration

This was measured utilizing a 9-item scale to measure the frustration. A 9-item scale utilizing a 5-point Likert scale was adopted with a range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, from the study of O’Neill and McLarnon [50].

3.1.4. Irritability

This was measured by utilizing a 30-point scale, of which 10 items were controlled items. A 30-item questionnaire utilizing a 5-point Likert scale was adopted with the range from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree, from the investigation of Caprara and Renzi [41].

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Information

Our data have a considerable representation of both genders. The respondents were aged between 18 and 59 years, while the lengths of their experience ranged from 1 to 40 years. In total, 43% doctors, 44% nurses and 13% other staff members (paramedics) filled our questionnaires with an acceptable level of accuracy (Table 2). As far as group analysis is concerned, it is evident that respondents from all the three groups (doctors, nurses, and paramedics) do have knowledge hiding inclinations, as the mean value of each group is higher than 2.75. Knowledge hiding behavior is slightly higher in doctors (2.86) followed by nurses (M = 2.781), while the mean value of the paramedic’s group is 2.777 (Table 3). However, there is no significant difference in knowledge hiding among these groups.

Table 2.

Detail of respondents.

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics.

4.2. Reliability Measures

Although we used previously tested instruments to collect responses, we verified the reliability and validity of the scales owing to possible differences in the context and respondents. Cronbach’s alpha established the reliability of the scales, as all the values were greater than 0.70, ensuring that the items were consistent (Table 4).

Table 4.

Reliability.

4.3. Validity

We examined the convergent validity of the variables by estimating a four-factor model with conformity factor analysis. The fit for this model was good. χ2 = 1688.6, CFI = 0.85, NFI = 0.735, RMSEA = 0.50. The suggestion of convergent validity comes from the strongly significant factor loadings for each of the items on their respective constructs (p < 0.001) [54]. Although we used time-lagged and multiple data sources to measure the different constructs, we also performed a series of confirmatory factor analyses to establish discriminant validity, with a particular focus on the constructs that we gathered from the same sources.

4.4. Correlations

The correlation table shows how well constructs are associated with each other (Table 5). This also explains the existence of autocorrelation in the data. The table indicates the relative strength among all of the constructs of the current research. The results reflect that the relationship between relationship conflict and frustration is positive and significant, where r = 0.222 and p < 0.01, and relationship conflict is correlated with irritability in such a way that r = 0.216 and p < 0.01. Similarly, relationship conflict and knowledge hiding are correlated, where r = 0.255 and p < 0.01. Irritability and frustration are correlated, as r = 0.533 and p < 0.01. Likewise, the correlation between frustration and knowledge hiding is positive, with r = 0.374 and p < 0.01. Lastly, knowledge hiding and irritability are positively and significantly correlated, as r = 0.374 and p is <0.01. The correlation between irritability and depression is r = 0.533 (p < 0.01). Depression is associated positively with hidden knowledge, with r = 0.374 (p < 0.01). The correlation between irritability and knowledge hiding is positive and significant at r = 0.359 (p < 0.01). At the same time, all the values of correlation coefficients are below 0.80, which rules out the possibility of autocorrelation in the data.

Table 5.

Means, standard deviations and correlations.

4.5. Hypothesis Testing

The analysis of the path coefficient shows that the data support all the hypotheses (Table 6). H1, indicating the possibility of more knowledge hiding as a result of relationship conflicts, is substantiated (β is 0.210, t is 4.48, p is 0.000). The relationship is significant at p ≤ 0.05, as the t statistic (4.48), which is higher than the threshold value (1.645), indicates the significance of outer loading, and provides sufficient evidence against the null hypothesis. The path coefficient (0.210) shows the reasonable strength of the causal relationship between relationship conflict and knowledge hiding. H2, assuming that relationship conflict creates frustration among employees, has been accepted (β is 0.217; t is 3.69, p < 0.01). The p-value and t value confirm that the relationship is significant, and there is sufficient evidence to reject the null hypothesis. Similarly, H3, claiming that frustrated employees are more inclined towards knowledge hiding, is substantiated (β is 0.240, t is 5.27, p is <0.001).

Table 6.

Path coefficients.

In addition, H4, which declares the mediating effect of frustration on relationship conflict and knowledge hiding, is also accepted, and partial mediation is established. Besides this, the indirect effects of relationship conflict resulting from frustration on knowledge hiding are also verified, as evidenced by the formal two-tailed significance test (Sobel z = 2.99, p < 0.05), and similarly the confidence interval bootstraps results at 95% for knowledge hiding, with indirect effects that do not display zeros between the upper and lower limit values (0.02, 0.09).

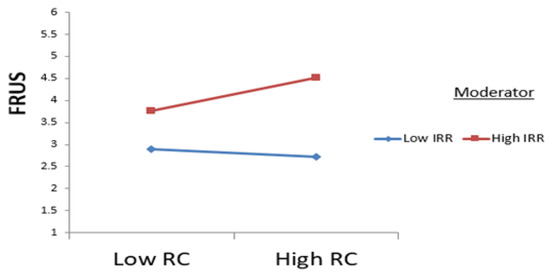

As indicated in H5, the relationship between relationship conflict and frustration is moderated by irritability, thus making this relationship stronger for more irritable people (Table 7). By using the PROCESS technique, results have been obtained that show the significant interaction term (relationship conflict * irritability) (β = 0.233, ΔR2 = 0.3562, p= 0.0006). Similarly, hypothesis 5 is accepted via the bootstrap with a CI of 95%, with lower-limit and upper-limit values (0.15, 0.46) of non-zero. Additionally, at higher levels of irritability, shown in the simple slope test (effect = 0.31, t = 4.03, p = 0.0001), the slope is significant, indicating that the link between relationship conflict and frustration is strengthened when the values are high (Figure 2).

Table 7.

Moderation analysis.

Figure 2.

Interaction plot.

5. Discussion

The data support all our hypotheses, and the hypothesized model has been empirically proven. The inferential statistical analysis established that employees tend to hide knowledge when they experience conflicts in relations and feel frustrated. Frustration mediates the relationship between relationship conflict and knowledge hiding. Irritability moderates the relationship between relationship conflict and frustration. Our first hypothesis appeared statistically significant, while the strength of the relationship was not that strong (β = 0.210). There are many alternative explanations for the occurence of knowledge hiding, but the role of relationship conflict cannot be ignored as a cause of hiding explicit knowledge. Relationship conflict and knowledge hiding both occur in hospitals. Apart from knowledge hiding, relationship conflicts in organizations result in performance disruption, low productivity, low motivation, absenteeism, and turnovers [55,56,57,58]. The findings are consistent with the literature, as Venz and Nesher Shoshan [59] identified that employees would hide their knowledge when they experience interpersonal conflicts. In the same vein, data support hypothesis 2 and confirm that relational conflicts create frustration, which is a counterproductive emotion. This finding is consistent with the literature [51,60,61,62]. Similarly, our findings substantiate employees’ knowledge hiding behavior as a result of being frustrated, which verifies previous studies [63,64,65].

Our findings establish the mediating role of frustration between relationship conflicts and knowledge hiding. This partial mediation denotes that employees get frustrated due to interpersonal conflicts within their organizations, and eventually hide their knowledge as retaliation. The literature exhibits that negative affectivity, including frustration and conflicts in the workplace, will discourage knowledge sharing [57,64]; however, the identification of frustration as a potential mediator is the novel addition of this research to the existing body of literature. Irritability has been found to be a moderator of the relationship between relationship conflicts and knowledge hiding. An increase in irritability strengthens the positive relationship between relationship conflicts and frustration. Uncovering the moderating effect of irritability on the relationship between relationship conflict and frustration is another seminal contribution of the study to the related body of knowledge.

6. Conclusions

In this era of technological advancement, the survival and growth of organizations are contingent upon knowledge-based interventions, including creativity and innovations. Knowledge donating and knowledge collecting explicitly influence innovation in organizations [66]. On the other hand, knowledge hiding is a negative behavior that may produce destructive consequences for organizations. Keeping in view the explanation of Affective Event Theory (AET), we structured a model showing that events such as organizational conflicts create corresponding emotions, such as frustration and irritability, which lead to behaviors such as knowledge hiding. Our data substantiate all the conjectured relationships by highlighting the existence of an alarming situation of knowledge hiding in hospitals. Our findings establish that one of the responses of employees to interpersonal conflicts, frustration, and irritability is knowledge hiding. Since any negative behavior in hospitals can cost human lives, it is a matter of concern for hospital administrators that knowledge hiding is more dangerous in hospitals. Most public sector hospitals are teaching hospitals, where medical students are taught through knowledge sharing. Knowledge hiding disastrously limits students’ learning processes, as well as from affecting patients’ healing processes. Thus hospital administrators can reduce the intensity and frequency of knowledge hiding by improving and managing interpersonal relations and creating a friendly and caring atmosphere within hospitals. This study tests a model in which mediating and moderating relations are somehow novel in nature, and it is an addition to the existing bank of literature. Since public sector tertiary hospitals are homogenous in terms of their structure and functions, we can confidently generalize our results to other public sector hospitals in the country. All the public sector hospitals fall under the administrative domain of the provincial health department, and policies are formulated and implemented in all the public sector hospitals uniformly. Employees are usually rotated among different public sector hospitals. That is why homogeneity always exists among public sector teaching hospitals.

6.1. Implications

Knowledge hiding is a behavior that an organization cannot afford for a longer period. As such, it has implications for researchers and managers. In this connection, the study in hand comes up with the following implications:

- Knowledge hiding does exist in hospitals and is partially caused by relationship conflicts, frustration, and irritability. Knowledge hiding becomes dangerous in hospitals when such behavior affects human lives, and it becomes more dangerous when the hospital is affiliated with a medical education institution for teaching and training purposes;

- Previous researchers admit that employees tend to hide knowledge due to interpersonal conflicts and frustration. However, the role of frustration as a mediator between interpersonal conflicts and knowledge hiding is newly illuminated through this study. Similarly, the moderating effect of irritability on the relationship between relationship problems and frustration is another addition to the literature;

- This study invites researchers to investigate the causes and consequences of knowledge hiding in healthcare settings. To the best of our understanding, studies investigating the bearings of knowledge hiding on patient outcomes and the learning of medical students are scant;

- The study guides hospital administrators to focus on relationship problems in order to reduce knowledge hiding. Ensuring a friendly and conducive environment will improve the quality of relations at the workplace, which in return will reduce frustrations and irritability in employees. As such friendly workplace relations will enhance the knowledge sharing culture within the organization.

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

This research work has certain limitations, and we take these limitations as avenues for future research. Firstly, our data do not represent the entire healthcare industry, as they have been collected from a single teaching hospital. Keeping in view the homogeneity of public sector teaching hospitals, we are optimistic about the generalizability of results to other public sector teaching hospitals; however, the findings may not work for public sector primary and secondary hospitals, private sector hospitals, and hospitals abroad. Secondly, due to certain constraints, some important variables could not be included in this model. For example, the literature indicates that culture, knowledge as power, lack of trust, differences in language, and tolerance of mistakes have impacts on knowledge hiding. However, these variables need to be considered for future research undertakings and the representation of samples from other contexts, including private sector hospitals, and primary and secondary hospitals. In future, studies will enhance the generalizability of findings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A.; methodology, Z.U.; validation, N.A., F.S.A. and Z.U.; formal analysis, M.S. and F.S.A.; investigation, E.A.; resources, M.S.; data curation, T.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted as per the ethical guidelines given in Helsinki Declaration. The authors also got approval from the ethical committee of Lahore Leads University, Pakistan (LLU/ERC/Res/21/34).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the respondents of the survey.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ghobadi, S. What drives knowledge sharing in software development teams: A literature review and classification framework. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Despres, C.; Hiltrop, J.M. Human resource management in the knowledge age: Current practice and perspectives on the future. Empl. Relat. 1995, 17, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Zweig, D.; Webster, J.; Trougakos, J.P. Knowledge hiding in organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2012, 33, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, G.A.; Bhatti, Z.A.; Ashraf, N.; Fang, Y.-H. Top-down knowledge hiding in organizations: An empirical study of the consequences of supervisor knowledge hiding among local and foreign workers in the Middle East. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 164, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zahedi, M.; Shahin, M.; Babar, M.A. A systematic review of knowledge sharing challenges and practices in global software development. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 995–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D. Linking human resource management and knowledge management via commitment: A review and research agenda. Empl. Relat. 2003, 25, 182–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosselin, P.A.; Gagné, J.-P. Use of a dual-task paradigm to measure listening effort utilisation d’un paradigme de double tâche pour mesurer l’attention auditive. Inscr. Répert. 2010, 34, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Anand, P.; Hassan, Y. Knowledge hiding in organizations: Everything that managers need to know. Dev. Learn. Organ. Int. J. 2019, 33, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerci, A.B. Examination of knowledge hiding with conflict, competition and personal values. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2019, 30, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; De Clercq, D.; Fatima, T. Organizational injustice and knowledge hiding: The roles of organizational dis-identification and benevolence. Manag. Decis. 2020, 59, 446–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, P.; Jain, K.K. Big five personality types & knowledge hiding behaviour: A theoretical framework. Arch. Bus. Res. 2014, 2, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, W.; Zhang, Q.; Teo, T.S.; Lim, V.K. The dark triad and knowledge hiding. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 42, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, A.C.; Baral, R.; Bednall, T.C. Don’t play the odds, play the man: Estimating the driving potency of factors engendering knowledge hiding behaviour in stakeholders. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2020, 32, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.; Saeed, H.; Zaigham, S.; Jahangir, S.; Ahmed, H.R.; Ullah, Z. Relationship of communication, mentoring and socialization with employee engagement. Eur. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- GÜRLEK, M. Antecedents of knowledge hiding in organizations: A study on knowledge workers. Econ. Bus. Organ. Res. 2020, 3, 20–32. [Google Scholar]

- Saif-ur-Rehman, M.A.K. The Psychometric Impacts of Karasek’s Demands and Control Scale on Employees’ Job Dissatisfaction. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 3794–3806. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava, S.; Pazzaglia, F.; Sonpar, K. The role of nature of knowledge and knowledge creating processes in knowledge hiding: Reframing knowledge hiding. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 136, 644–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavik, A. A systematic review of the servant leadership literature in management and hospitality. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 347–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škerlavaj, M.; Connelly, C.E.; Cerne, M.; Dysvik, A. Tell me if you can: Time pressure, prosocial motivation, perspective taking, and knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 22, 1489–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, W.; Cai, Z.; Luo, J.; Men, C.; Jia, R. Antecedents and intervention mechanisms: A multi-level study of R&D team’s knowledge hiding behavior. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 880–897. [Google Scholar]

- Serenko, A.; Bontis, N. Understanding counterproductive knowledge behavior: Antecedents and consequences of intra-organizational knowledge hiding. J. Knowl. Manag. 2016, 20, 1199–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issac, A.C.; Baral, R. Knowledge hiding in two contrasting cultural contexts: A relational analysis of the antecedents using TISM and MICMAC. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2019, 50, 455–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, X.; Ding, X. Enterprise social media usage and knowledge hiding: A motivation theory perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2149–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, G.A.; Hameed, I.; Umrani, W.A.; Khan, A.K.; Sheikh, A.Z. Consequences of supervisor knowledge hiding in organizations: A multilevel mediation analysis. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 1242–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, M.I.; Dechun, H.; Ali, M.; Usman, M. Ethical leadership and knowledge hiding: A moderated mediation model of relational social capital, and instrumental thinking. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abubakar, A.M.; Behravesh, E.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Yildiz, S.B. Applying artificial intelligence technique to predict knowledge hiding behavior. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 49, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljawarneh, N.M.S.; Atan, T. Linking tolerance to workplace incivility, service innovative, knowledge hiding, and job search behavior: The mediating role of employee cynicism. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2018, 11, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, X. Knowledge hiding as a barrier to thriving: The mediating role of psychological safety and moderating role of organizational cynicism. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 800–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly, C.E.; Kelloway, E.K. Predictors of employees’ perceptions of knowledge sharing cultures. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2003, 24, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, J.; Wang, C. Does abusive supervision always promote employees to hide knowledge? From both reactance and COR perspectives. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1455–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, J.K.; Varkkey, B. Are you a cistern or a channel? Exploring factors triggering knowledge-hiding behavior at the workplace: Evidence from the Indian R&D professionals. J. Knowl. Manag. 2018, 23, 1455–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Khalid, M.; Gulzar, A.; Khan, A.K. When and how the psychologically entitled employees hide more knowledge? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 89, 102413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moh’d, S.S.; Černe, M.; Zhang, P. An exploratory configurational analysis of knowledge hiding antecedents in project teams. Proj. Manag. J. 2021, 52, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Xu, Y.; Hussain, S. Workplace ostracism and knowledge hiding: The mediating role of job tension. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davenport, T.H.; Prusak, L. Information Ecology: Mastering the Information and Knowledge Environment; Oxford University Press on Demand: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H.M.; Beal, D.J. Reflections on affective events theory. In The Effect of Affect in Organizational Settings; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, H.M.; Cropanzano, R. Affective events theory. Res. Organ. Behav. 1996, 18, 1–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ashton-James, C.E.; Ashkanasy, N.M. Affective events theory: A strategic perspective. In Emotions, Ethics and Decision-Making; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glasø, L.; Vie, T.L.; Holmdal, G.R.; Einarsen, S. An application of affective events theory to workplace bullying. Eur. Psychol. 2010, 16, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegge, J.; Dick, R.v.; Fisher, G.K.; West, M.A.; Dawson, J.F. A test of basic assumptions of Affective Events Theory (AET) in call centre work 1. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Renzi, P.; Alcini, P.; Imperio, G.D.; Travaglia, G. Instigation to aggress and escalation of aggression examined from a personological perspective: The role of irritability and of emotional susceptibility. Aggress. Behav. 1983, 9, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, P.C.; Holtzman, S.; Cunningham, S.; O’Connor, B.P.; Stewart, D.E. Building a definition of irritability from academic definitions and lay descriptions. Emot. Rev. 2016, 8, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Toohey, M.J.; DiGiuseppe, R. Defining and measuring irritability: Construct clarification and differentiation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 53, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal-Ribas, P.; Brotman, M.A.; Valdivieso, I.; Leibenluft, E.; Stringaris, A. The status of irritability in psychiatry: A conceptual and quantitative review. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2016, 55, 556–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodionova, V.I.; Shvachkina, L.A.; Kuznetsova, L.E. Family psychological violence influence on adolescent aggressive behavior formation. Mod. J. Lang. Teach. Methods 2018, 8, 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Jehn, K.A. A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Adm. Sci. Q. 1995, 40, 256–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushman, B.J. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 28, 724–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holtzman, S.; O’Connor, B.P.; Barata, P.C.; Stewart, D.E. The brief irritability test (BITe) A measure of irritability for use among men and women. Assessment 2015, 22, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zutshi, A.; Creed, A.; Bhattacharya, A.; Bavik, A.; Sohal, A.; Bavik, Y.L. Demystifying knowledge hiding in academic roles in higher education. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, T.A.; McLarnon, M.J.; Hoffart, G.C.; Woodley, H.J.; Allen, N.J. The structure and function of team conflict state profiles. J. Manag. 2018, 44, 811–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, M.; Medina, F.J.; Munduate, L. Buffering relationship conflict consequences in teams working in real organizations. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2018, 29, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, A.M. Influencing Factors of Consumer Behaviour in Retail Shops. 2018, pp. 1–18. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3151879 (accessed on 4 October 2021). [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.Z.; Khan, M.A. Towards service quality measurement mechanism of teaching hospitals. Int. J. Healthc. Manag. 2020, 14, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, N.; Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.Z. Impact of ethical conflict on job performance: The mediating role of proactive behavior. Asian J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 7, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.D. Managing Conflict in the Workplace. In Women in Ophthalmology: A Comprehensive Guide for Career and Life; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Başoğul, C. Conflict management and teamwork in workplace from the perspective of nurses. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, Z.; Khan, M.Z.; Siddique, M. Analysis of employees’ perception of workplace support and level of motivation in public sector healthcare organization. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2017, 9, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venz, L.; Shoshan, H.N. Be smart, play dumb? A transactional perspective on day-specific knowledge hiding, interpersonal conflict, and psychological strain. Hum. Relat. 2021, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguegbe, T.M.; Ezeh, L.N.; Iloke, S.E. Organisational based frustration in manufacturing companies: A correlational study of innovative behaviour and work family conflict. Br. Int. J. Educ. Soc. Sci. 2020, 7, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Marineau, J.E.; Hood, A.C.; Labianca, G. Multiplex conflict: Examining the effects of overlapping task and relationship conflict on advice seeking in organizations. J. Bus. Psychol. 2018, 33, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onedibe, G. Perceived organizational support and role conflict as predictors on organizational frustration among health workers in imo state. Nnadiebube J. Soc. Sci. 2019, 2, 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zakariya, R.; Bashir, S. Can knowledge hiding promote creativity among IT professionals. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. 2020, 51, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Clercq, D.D.; Fatima, T. Bridging the breach: Using positive affectivity to overcome knowledge hiding after contract breaches. J. Psychol. 2020, 154, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzeb, S.; Fatima, T.; Bouckenooghe, D.; Bashir, F. The knowledge hiding link: A moderated mediation model of how abusive supervision affects employee creativity. Eur. J. Work. Organ. Psychol. 2019, 28, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamaşak, R.; Bulutlar, F. The influence of knowledge sharing on innovation. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2010, 22, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).