Abstract

The 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) adopted by the UN provide a blueprint for a more sustainable future for all. The implementation of the SDGs largely depends on the action taken by national and local governments. The Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area (GBA) is an area in China with special economic conditions and political support. This paper aims at exploring the legal issues concerning the integration and cooperation among different regions in the GBA and the implementation of the SDGs. It concludes that the GBA could perform an important role in the future exploration of sustainable development and opening-up of China. Clearer and systematic legislation is needed to provide more legal instruments and a more solid legal basis for integration and cooperation in the GBA. Chinese policymakers should fill the legal gaps and provide more legal support for the integration. This could shed light on China’s further exploration of sustainable development both domestically and internationally.

1. Introduction

In 2015, the UN adopted 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs), aiming at providing a blueprint for a more sustainable future for all. Issues including poverty, hunger, health and well-being, education, gender equality, sanitation, energy, job opportunities, infrastructure, equalities, sustainability, recycling, climate change, ocean and land environment, justice, and partnerships are all listed in the agenda [1]. Under current circumstances, the implementation and fulfilment of the SDGs largely depend on the action taken by national governments [2]. Therefore, the incorporation of the goals into national and local legislation and the implementation of it are vital. The Chinese government has increasingly paid attention to sustainability issues. In recent years, the Chinese government has adopted development-oriented poverty reduction programs and environmental protection policies to enhance sustainable development [3,4]. In particular, in 2019, the central government proposed a scheme to integrate Guangdong Province, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), and Macau Special Administrative Region (MSAR) to establish a Greater Bay Area. In the Outline Development Plan for the GBA (herein after the Outline Development Plan), several points relating to the SDGs are highlighted, for instance, coordinated regional development, infrastructure support, green and sustainable way of production and lifestyle, the well-being of residents, and ecological environment protection [5]. The central government has high expectations for the GBA to foster new economic drivers, long-term prosperity, innovation-driven development, deeper reforms, further opening-up, and a support area for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The GBA performs as a pilot area for China to explore a better integration and cooperation of societies with different economic, political, and legal structures. It helps to shape China’s practice of pursuing better and more balanced domestic development. It also contributes to China’s practice of encouraging greater involvement and participation of other states on the sustainability issues under China’s geopolitical strategies, such as the BRI.

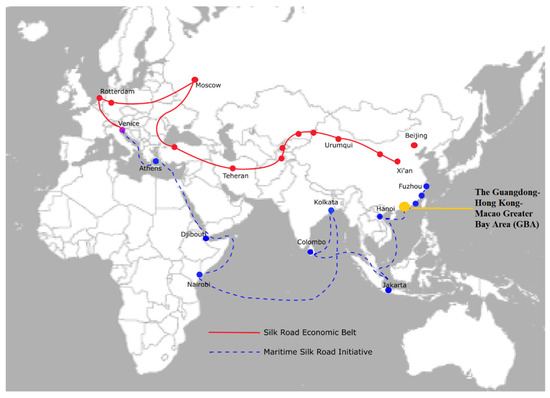

The BRI is a strategy proposed by China in 2013. Inspired by the ancient trade route “Silk Road”, the BRI aims to connect Asia, Europe, and Africa via two networks: the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt (the belt) and the 21st-century Maritime Silk Road (the road) (Figure 1). The strategy pays special attention to five priorities: policy coordination, infrastructure connectivity, unimpeded trade, financial integration, and communication of people. Thus far, more than 100 countries from Europe, Asia, Africa, and Latin America have signed agreements with China to cooperate in BRI projects [6]. The BRI plans to connect the economically developed area (the EU), economically active area (East and Southeast Asia), and the broad area with the great economic potential of the three continents. Duplicating China’s experience of poverty alleviation that “if you want to get rich, build roads first”, the BRI aims at helping the countries along the belt and road to improve infrastructure and open up new opportunities in a sustainable way. It conforms to the SDGs, especially concerning poverty, sanitation, job opportunities, infrastructure, and partnership. The GBA is important for the BRI. Firstly, its location is crucial. The GBA has a close connection with many Southeast Asian countries, both economically and culturally. It owns busy harbors and is important for China’s cross-border trade, connecting China with the world market. Secondly, the GBA has a financial center, Hong Kong, and an active financial market. The implementation of the BRI greatly depends on the investment and financial market. Thirdly, the GBA has long been a pilot area for China’s reform and new policies. In the past decades, China’s development has largely been based on its adoption of the trial-and-error approach. Many policies are firstly applied in the GBA and then adopted nationwide. This tradition helps the GBA to become an important area for the exploration of policies concerning the BRI.

Figure 1.

The GBA and the BRI. Source: adapted from Wang L. et al. (2019) [7].

Despite the excellent location and ambitious plan, the GBA faces both opportunities and challenges. Among them, unbalanced development between different regions and insufficient legal instruments for integration and cooperation are the key issues. Although there are strong and collective political wills of the central and local governments to promote the regional integration and cooperation, solid legal bases and available legal instruments are relatively lacking. China has already realized this problem and has been committed to promoting “law-based governance” [8], particularly in the last decade.

This paper aims at exploring the integration and cooperation among different regions in the GBA and the implementation of the SDGs. In the first section, a brief introduction is given. The second section examines in detail the past, present, and plans for the future of the GBA. It demonstrates that the GBA has always been a special area in China, and it can be an ideal place for China to further explore sustainable development. However, there are also challenges facing the GBA to improve sustainability, especially concerning unbalanced development. The third section firstly explores China’s incorporation of the SDGs into the policies and then elaborates the big challenge faced by the GBA to fully implement the policies: unbalanced development during the urbanization in the GBA. To foster regional high-quality development, integration and cooperation should be encouraged and legal instruments are crucial for it. Therefore, the fourth section examines in detail the current legal framework concerning the integration and cooperation in the GBA. Problems existing in current legal instruments are identified. Based on the above analysis, some policy recommendations are given in the fifth section and a conclusion is given at the end of the paper. It concludes that the GBA could perform an important role in the future exploration of sustainable development and opening-up of China. Although several legal instruments at the national, regional, local, and international levels have been provided, clarification and systematization are needed. Chinese policymakers should fill the legal gaps and provide more legal support for the integration and the implementation of the SDGs in the GBA. This could shed light on China’s further exploration of sustainable development both domestically and internationally.

2. The GBA: Past, Present and Future

As one of the most open and economically vibrant regions in China, the GBA is a good example and experimental region for China to explore high-quality and sustainable development. The GBA has special geographic, economic, and social conditions. Furthermore, history brings this area a unique political structure—leading to both problems and advantages.

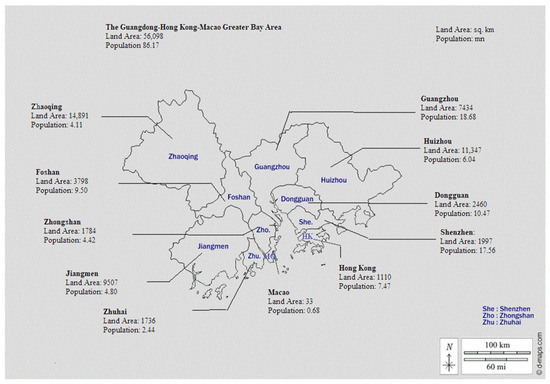

In the 19th Communist Party of China (CPC, the current ruling party in China) National Congress, the Chinese government proposed “high-quality development”, which demonstrates a fundamental change of China’s long-term goal. In the past several decades, the Chinese government has concentrated more on development speed instead of development quality. The proposal of high-quality development marks a shift of focus from “whether or not” to “good or not”. This new development philosophy particularly emphasizes five aspects: innovative, coordinated, green, open, and shared development [9]. Several policies have been adopted correspondingly. The Chinese government has encouraged the development of city clusters to implement the goal of high-quality development, of which sustainable development is an important part [10]. Among the planned city clusters, the GBA is an important one. The GBA enjoys unique favorable conditions to foster sustainable development. From a geographic perspective, the GBA includes two special jurisdictions, the HKSAR and the MSAR, and the “nine Pearl River Delta (PRD) municipalities”, Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Foshan, Huizhou, Dongguan, Zhongshan, Jiangmen, and Zhaoqing in Guangdong Province [11] (Figure 2). The two special jurisdictions are separated jurisdictions because of historical reasons and have considerable autonomy concerning economic, social, and legal issues. The GBA covers a total area of 56,000 square kilometers with a population of approximately 70 million. With good ports and easy access to busy shipping routes such as the Strait of Malacca, economic activities in the GBA have been largely increasing with the opening-up of China. In terms of the economic aspect, the GBA has played leading roles in China. The two SARs have been highly developed. The HKSAR is a free port and international financial, transportation, and trade center. The MSAR is a global tourism and leisure center. Guangdong Province has been the largest province by GDP in Mainland China since 1989 and its economy is highly vibrant. According to a report issued by Beijing University, Guangzhou ranks third concerning the business environment in China in 2020, with Beijing ranking first and Shanghai second [12]. A strong and vibrant economy means better financial, technology, and intellectual support to the implementation of the SDGs. From the social aspect, the GBA has an open environment for innovation and technology development. Guangdong has ranked high concerning the “openness of the society” in the past several decades according to the Openness Index Report of China issued by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) [13].

Figure 2.

Basic information of the GBA. Data Source: Bureau of Statistics of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao; The figure is adapted based on the map at https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=20983&lang=zh, accessed on 1 October 2021.

Other significant factors affecting the adoption and implementation of the SDGs in the GBA are the political and legal aspects. The GBA has always been a special area in China since the late Qing Dynasty. Between 1842 and 1898, Hong Kong was ceded to the British through the Treaty of Nanjing (the Hong Kong Island was permanently ceded to Britain), the Convention of Beijing (the southern tip of the Kowloon Island was permanently ceded to Britain), and the Kowloon Extension Agreement (the New Territories were “leased” to Britain for 99 years). In 1887, the Qing Dynasty gave Portugal perpetual colonial rights to Macau in the Sino-Portuguese Treaty of Beijing. After the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese government took a consistent position that China does not recognize the unequal treaties imposed on it by imperialism. Since the 1980s, the Chinese governments have gone through many rounds of negotiation with the British and Portuguese governments concerning the handover of Hong Kong and Macau, respectively. Two Joint Declarations were concluded in 1984 and 1987. The jurisdiction of Hong Kong and Macau was transferred back to China in 1997 and 1999, respectively [14]. When governed by Britain and Portugal, British and Portuguese Laws were applied in Hong Kong and Macau. From the legal perspective, British law is Common Law and Portuguese Law is Civil Law. Both have significant differences with the socialist law applied in the mainland. Considering this situation, the then Statesman, Deng Xiaoping, proposed the policy of “one country, two systems”. It was believed that adopting this policy not only aimed at providing a leeway for the two SARs but also exploring China’s future path for opening to and integrating with the world. The policy was incorporated in the Chinese Constitutional Law in 1982. As a result, the GBA has a unique characteristic: “one country, two systems, and three jurisdictions”. Under the current structure, the two SARs maintain their economic, social, and legal systems and the governments of the two SARs enjoy the executive, legislative and judicial power.

In 2017, the central government, Hong Kong government, Macau government, and Guangdong government signed the Framework Agreement on Deepening Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Cooperation in the Development of the Greater Bay Area (hereinafter the Framework Agreement), which suggests that to build the city cluster of the GBA is the common will of the central government and the three regions. Briefly speaking, each region faces different problems and has the need to integrate and better allocate the resources. In 2020, affected by the pandemic, the economic activities of the two SARs shrank dramatically, and the unemployment rate rose rapidly [15]. Deeper causes include the limited market, high dependence on the service sector, and lack of physical space and natural resources [16]. In addition, thinking of the bigger picture, the two SARs largely benefit from the opening-up of China to the world, especially Hong Kong. With more competitive metropolis developing and less restrictive policies concerning the market in Mainland China, the importance of the two SARs are decreasing. Guangdong Province, on the other hand, can benefit from the capital and high-educated human resources after the development of the GBA. In addition to the benefit for the two SARs and Guangdong, the central government also considers further exploration of the central–local relations, regional central cities, and cross-border integration.

Therefore, for future development, the GBA has gained consensus from the local governments and special support from the central government to do experiments and innovation to improve the institutional framework of sustainability management. It is required to adopt an “early and pilot implementation approach”, which means that more flexibility is given to the local governments. To be more specific, the two SARs are granted considerable autonomy. They are separate customs territories and have maintained independent finances and taxation systems. Previous laws are mostly maintained, and the two SARs exercise their administrative, legislative, and independent judicial power. Guangdong Province has been a pilot zone for China’s reform and opening-up. In 2015, the State Council issued a Notice to establish the Guangdong Pilot Free Trade Zone, which requires the Guangdong government to “be bold in practice and active in exploration…to give support to the pilot programs of Guangdong Free Trade Zone”. Three pilot zones in three Guangdong cities, Guangzhou (Nansha), Shenzhen (Qianhai), and Zhuhai (Hengqin) were established to promote the legal environment and innovate the regulatory mode. In 2019, the State Council issued Opinions on Supporting Shenzhen in Building a Pioneering Demonstration Zone, in which Shenzhen was expected to be a “model city of the rule of law” and “pioneer of sustainable development”. Shenzhen was required to “make full use of its legislative power as a special economic zone” and was given the power to “make adaptions to laws, administrative laws and regulations, and local laws and regulations under the premises of abiding by the Constitution, laws and administrative laws and regulations”.

In summary, the geographic location and unique history have brought the GBA special economic, social and political problems and conditions for pursuing high-quality development. Against the background that China has been paying more and more attention to sustainability development, the GBA performs as an ideal area for policy experimentation and innovation.

3. SDGs in the GBA: Why Legal Instruments Are Important

The goal of high-quality development proposed by the Chinese government largely conforms to the SDGs. Both the central and local governments have realized the importance of it and have incorporated some key points of it into the policies and plans. However, to achieve the goals, the GBA confronts a significant challenge: unbalanced development. Integration of markets and cooperation of governments are needed to remedy the problem. As President Xi Jinping indicated, it is both very important to “make a bigger cake” and “better divide the cake” [17]. Legal instruments can perform an important role in addressing this problem. This section examines the incorporation of the SDGs in the GBA, the challenge faced by the GBA, and the significance of the legal instruments to respond to the challenge.

3.1. Incorporation of the SDGs in the GBA Policies

The SDGs have been explicitly incorporated in the policies developed by the Chinese central and local governments. In the Framework Agreement, to prioritize ecology and pursue green development was included in the principles of cooperation. A specific key cooperation area identified by it emphasizes the promotion of infrastructure connectivity, the coordinated development, and the quality of life, in particular, better education, health, and ecological environment. In the Outline Development Plan, more coordinated development, green development, ecological conservation, and the improvement of people’s livelihood have been adopted as basic principles. It also provides a timetable and specific objectives to implement the sustainable development goals. By 2022, more coordinated regional development, innovation, upgrading of traditional industries, infrastructural support, and a green way of production and lifestyle shall be enhanced. By 2035, the GBA is expected to be a highly connected and coordinated area, with wealthier residents, more efficient use of resources, and a better ecological environment in comparison with today. The above discussion demonstrates that both the central and local governments have devoted much attention to the SDGs in the GBA, especially concerning balanced development, the well-being of the residents, and energy conservation and ecological environment.

3.2. The Challenge to the GBA: Unbalanced Development

Notwithstanding the favorable conditions and strong will of the governments to develop a better community fulfilling the SDGs, a significant challenge confronts the GBA: the unbalanced development during urbanization. The HKSAR and the MSAR were occupied by Western countries in history and developed earlier than Guangdong. The differences between the GDP and GDP per capita of the cities in the GBA are huge. The composition of the GDP also varies. According to the latest statistics, the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors contribute 0.1%, 6.5% and 93.4% to the GDP in HKSAR, respectively [18]. Primary sectors (raw materials) include any industry involved in the extraction and production of raw material, while secondary sectors (manufacturing) take the output of the primary sector and create finished goods and tertiary sectors (services) provide services instead of end products. While in the MSAR, the secondary and tertiary sections count on 4.2% and 95.8%, respectively [19]. In Guangdong, the numbers are 4.0%, 40.2%, and 55.8% [20]. The three jurisdictions are at different development stages. While Guangdong is still developing and modernizing fast quantitively, the HKMSAR and the MSAR have relatively slowed down and need to pay full attention to the quality of the development [21]. Even considering the situation in Guangdong, unbalanced development is obvious. Guangdong has experienced a remarkable urban expansion in the past decades, especially driven by the income increase, infrastructure improvement, and population growth, but the differences among the municipalities are still significant [22] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main Indicators of cities in the GBA (2020).

Unbalanced development and the different degrees of urbanization have a significant impact on the implementation of the SDGs in the GBA. Firstly, barriers in the GBA are still significant, especially concerning the movement of labor and capital. The two SARs enjoy independent jurisdiction and residents of them enjoy different citizen rights associated with the right of abode. These include not only evident rights such as border entry, working permission, social welfare, etc., but also indirect differences such as public services and social environment. Regarding Guangdong Province, because of the Hukou system (the Chinese household registration system), a citizen’s benefit is largely affected by where he or she registers, including housing, children’s education, social security programs, etc. [23]. Pointing out that there are significant barriers in the GBA is not aiming at pursuing a complete removal of all barriers and differences, but rather reminding scholars and practitioners that problems associated with it should be carefully addressed.

Secondly, research concerning the situations in the GBA has proven that urbanization is related to sustainability issues [24]. The past 40 years have seen rapid urbanization in China. However, the degree of urbanization in different districts is different. Except for the central cities, there are still large rural areas in the GBA. In more developed areas, pillar industries are likely to be the service sector, which creates less pollution and causes fewer environmental problems [25]. The situation is the opposite in the less developed areas. Different regions are facing different problems. The regional central cities may face over-urbanization with crowd problems, the rising cost of living, and shortage of land and other resources [26]. In contrast, small cities in this region may face a brain drain, low-efficient usage of resources, and a lack of financial support to foster sustainable development [27]. Gaps between each other and disaccord are unavoidable. In brief, the needs and vital interests of different regions are significantly different.

Thirdly, although authorities are paying increasing attention to the quality and sustainability of the development, the abilities of the authorities to manage the sustainable issues are different. Goals such as health and well-being, education, sanitation, energy, sustainability, recycling, ocean and land environment, and justice are mostly public goods, which largely depend on the capability of the local governments. Authorities in richer areas have a better financial situation based on a bigger population, stronger industries, efficient productivity, higher land sales revenue, and higher tax revenue [22]. They also develop more solid technology and intellectual support from society [28]. As mentioned above, the two SARs have considerable autonomy. Economic, social, and judicial affairs are all managed by the SAR governments. Normally, they neither turn in revenues nor enjoy transfer payments from the central government. In terms of Guangdong Province, central–local relations in Mainland China are an important factor affecting the public service. At present, in general, matters concerning social insurance, education, medical resources, and sanitation largely depend on local finance in the eastern provinces [29]. In short, public services are provided by different regions and the capabilities of governments significantly affect the implementation of sustainable development.

3.3. The Need for Integration and Cooperation in the GBA to Implement the SDGs

The challenge of unbalanced development in the GBA has been examined above. To deal with it, regional integration and cooperation are needed. The need can be analyzed from two aspects, the central government perspective, and the local perspective.

In terms of the central government, integration in the GBA is pursued to fulfil the strategic need, both domestic and international. Domestically, it fits the goal of high-quality development proposed by the central government. “Regional coordinated and balanced development” have been involved in the recent five-year plan. In the past several decades, urbanization in China has been significantly improved and economics has been growing fast. The development, however, features massive quantity rather than high quality [30]. It may lead to interest conflicts, incompatible policies, and difficulties in coordination. Competition prevailed over coordination in China [31]. Competition exists among cities, provinces, and regions. Local governments in China compete for capital, human resources, public goods, investment, tax, and payment, etc. [30] Motivations for the competition include both economic incentives (financial revenue and personal income) and political incentives (personal promotion) [32]. Research has shown that instead of the quantity and quality of the public goods provided, local governments cared more about the efficiency of resource allocation and economic performance [33]. This type of competence may cause many problems, such as parallel construction, inefficient industry distribution, local protectionism, and a larger amount of local government debt [30]. More importantly, if competition instead of integration and cooperation dominate the relations between governments, bigger differences among regions may occur, which is called the Matthew effect [34]. Emphasis on integration and cooperation instead of competition and speed with appropriate policies help to better allocate resources and solve problems that are commonly faced, especially problems mentioned above: barriers between regions, gaps between urbanized and rural regions, and different abilities and resources of local governments.

Internationally, China’s global influence has significantly increased in the past several years. However, China’s ability and available instruments of participating in global governance and dealing with global affairs still need improvement. In recent years, China has been dedicated to regional cooperation and market integration in the Asia-Pacific area. However, lack of experience may be a disadvantage for the Chinese government to deal with issues involving various societies with different economic, political, social, and cultural conditions. The GBA can be an area for the Chinese government to explore integration in a sustainable way with a trial-and-error approach considering the complicated economic, social, and political differences of the three jurisdictions. This helps China to enhance its ability to deal with international and regional affairs and better participate in international cooperation. With the development of the GBA, China wants to establish an international city cluster and set an example of an integrated and coordinated area consisting of societies with different economic and political structures.

Regarding the local level, there are also incentives for the HKSAR, MSAR, and Guangdong governments to promote integration and cooperation in the GBA. For the two SARs, the development of the GBA contributes to the solution of their problems. Firstly, the two SARs have limited markets, populations, resources, and land. These factors decided that the development of the two SARs depends on their accessibility to larger markets and resources. Secondly, the economy of two SARs largely depends on the service sectors and has relatively fallen behind compared with some mainland cities concerning technological development. In addition, the special advantages of the two SARs compared with other regions in Mainland China are less over time. The two SARs have long been an open gate for China to the world because of their special statuses. They used to enjoy significant advantages especially because of the different legal and financial policies. With the market-oriented reform and openness of Mainland China, as well as the growing competition with mainland cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, the two SARs need to take a more active position to facilitate regional integration to fully utilize the market and resources in the GBA for their future development. Thirdly, the changing policies of the central government also require the SARs to better integrate with the neighboring regions. The two SARs have enjoyed some one-sided preferential policies from the mainland, for example, housing, education, labor market accessibility, etc. [35]. This is so not only because of the special advantages and conditions of the SARs but also because of the historical and political factors. From a long-term perspective, however, one-sided preference is not sustainable. With more resources and policy preferences given to other regions such as Hainan, the two SARs have to relocate their positions. In a word, all the above physical, economic, and political factors create incentives for the two SARs to integrate into the GBA.

For Guangdong Province, the regional integration of the GBA can also produce huge benefits. Firstly, Guangdong has a close connection with the two SARs. It enjoyed great benefit from the two SARs during its development in the last several decades, especially concerning investment and intelligence. Its future development also largely depends on the investment it gains and China’s integration into the world. Therefore, its long-term and sustainable development are largely influenced by the integration in the GBA. Secondly, the problem of unbalanced development among regions is particularly serious in Guangdong. Therefore, making comprehensive plans and better allocating resources are important for Guangdong. In this regard, the local government should concentrate on further unlocking the potential of the less-developed regions and using technologies and market-based measures to pursue sustainable, balanced, long-term, and high-quality development. Integration of the GBA and cooperation among local governments can contribute to the removal of market barriers, and further urbanization and capacity building of the governments.

In short, the unbalanced development may significantly affect sustainable development of the GBA. The old style of development, in which competition is more emphasized, is no longer in line with China’s goal of pursuing high-quality development. According to Perroux’s growth pole theory, regional growth poles can promote regional economic growth with spill-overs to neighboring areas [36]. However, only with a healthy regional competition environment and long-term plan can the theory be realized [37,38]. The need has been recognized by not only the central government but also the local governments in the GBA. The governments should look for tools to foster integration and cooperation among different regions in the GBA. Among them, legal instruments are of great significance.

3.4. Use Legal Instruments to Encourage Integration and Sustainable Development

The above section examines the incentives and benefits for the central government, HKSAR, MSAR and Guangdong to engage in the integration and cooperation in the GBA. Legal instruments should play important roles to encourage regional integration and sustainable development. The following two reasons deserve special attention. First, currently, legal instruments constitute a weak point for further integration in the GBA. China has less-developed legislation concerning the relations between public authorities [39]. While China has developed more systematic private laws and criminal laws, the exploration of rules regulating relations between private parties and public authorities is relatively lagging, not to say legal cooperative mechanisms between public authorities [40]. In Mainland China, a vertical structure has been established concerning the executive authorities where the higher-level bodies perform a leading and monitoring role. The system guarantees the effectiveness of the executive activities [41]. Where the two SARs are involved, however, a loophole was created. As the two SARs are granted autonomy and most of the administrative regulations are not applied in the two SARs, this vertical administrative system creates fewer political incentives for the local governments to take active positions promoting integration and cooperation, especially when the two SARs are more developed than the mainland cities. Current Chinese constitutional and administrative law involves no legal instruments encouraging and monitoring the implementation of the GBA integration and cooperation.

Second, the special situation in the GBA calls for an improvement of the legal tools. Generally speaking, the central government has given considerable autonomy to the two SARs and executed observation rather than direct intervention [42]. The GBA faces a complicated situation as there are three jurisdictions involved the “one country, two systems”, uniquely designed based on the historical and then-situation in Hong Kong and Macao. It was an invention of China, which has helped to effectively solve Hong Kong/Macao’s historical reunification problem and guaranteed a smooth transition from Britain/Portugal to China [43]. However, although the change of legal status can be done immediately, the economic, social, and cultural integration has to be done step by step. Both the two SARs have more mature legal cultures, and the spirit of the law is highly respected. On the other hand, in Mainland China, the development of the socialist legal system is still under exploration, and the “rule of law” has been consistently emphasized by the central government [8]. Compared with high-sensitive political tools, legal instruments can better help the regions in the GBA to find common interests, establish a cooperation framework, and guarantee the implementation.

Overall, the high-quality development proposed by the Chinese government is consistent with the SDGs, and both the central and local governments have incorporated some important points into the plans and policies. However, unbalanced development is a big challenge for the implementation of the SDGs. Integration and cooperation rather than competition should be emphasized in the future development in the GBA. Legal instruments are of great significance to the integration and cooperation of the GBA, as it has been a weak point that needs substantial improvement and the special situation in the GBA calls for better legal instruments. In the next section, available legal instruments and their current problems are explored.

4. An Examination of the Legal Instruments

The existing legal framework for the integration and cooperation in the GBA is examined in this section, including legislation and policies at different levels: constitutional legislation, national legislation and policies, interregional cooperation arrangements, local legislation, and international law. Generally speaking, constitutional laws are the Basic Laws, which provide fundamental principles for the governments. National laws mostly concern different issues and can provide more detailed rules and indications for the relations of the central government, the SARs, and Guangdong Province. Interregional cooperation arrangements can perform an important role in addressing regional issues and specific matters concerning different regions. However, this form of rule has not gained a clear legal basis in Chinese law. Local laws are adopted by local governments to implement high-level laws and policies and better address local issues. Some international laws can be applied considering the special status of the SARs, especially international trade law, the cases of which are mostly initiated by private parties.

4.1. Constitutional Legislation

The GBA covers the two SARs and Guangdong Province in Mainland China. The legal status and competence of the regions are stipulated in the constitutional legislation. The “one country, two systems” policy is an innovative institutional design based on the specific situation in the two SARs. Article 31 of the Constitution provides the constitutional basis for it: “The State may establish special administrative regions when necessary. The systems to be instituted in special administrative regions shall be prescribed by law enacted by the National People’s Congress in the light of specific conditions.” In accordance with this provision, the HKSAR and MSAR Basic Laws are established by the People’s Congress. According to the Basic Laws, the two SARs have a high degree of autonomy and enjoy executive, legislative, and independent judicial power, including that of final adjudication. The socialist system and policies are not practiced in the two SARs and the previous capitalist system and way of life shall remain unchanged for 50 years. The laws previously in force in the two SARs are maintained if not contravene the Basic Laws. It is provided that national laws shall not be applied in the two SARs except for those listed in Annex III. In a word, the Constitution grants considerable autonomy to the two SARs.

The local government of Guangzhou also has legislative, executive, and judicial power granted by the Constitution. According to Article 100 of the Constitution, the legislature at the provincial level is able to adopt local regulations which do not contravene the Constitution and other laws and administrative regulations. Article 72–74 of the Legislation Law provides that legislature at the provincial level, of the comparatively larger cities, and of the provinces and cities where special economic zones are located may formulate regulations subject to certain conditions. The legislative power is limited to “matters requiring the formulation of specific provisions in light of the actual conditions of an administrative area for implementing the provisions of laws or administrative regulations”, “matters of local character that require the formulation of local regulations” and some matters for which “the State has not yet formulated any laws or administrative regulations”. Subject to certain procedures, the legislature at the municipal level has the competence to make rules on matters concerning urban and rural development and management, environment protection, historical culture protection, and so on.

In summary, all administrative regions in the GBA have certain competency to adopt legislation concerning local affairs. However, the degree of autonomy is different. Under the current vertical system, Guangdong has less autonomy, as the legislature can only make rules concerning certain matters subject to certain conditions and certain procedures. They must not contradict the Constitution, the law, and the administrative regulations. By contrast, the two SARs have more autonomy on economic, administrative, social, and cultural issues. This leads to unequal competence and power for the three regions.

4.2. National Legislation and Policies

As mentioned above, national laws are generally not applied in the two SARs. There are basically two categories of national legislation. The first category includes the laws promulgated by the People’s Congress concerning the SARs’ affairs, for example, the laws on measures for the election of deputies to the National Congress and the decision authorizing the HKSAR and the MSAR to exercise jurisdiction over Port Zones in Shenzhen and Zhuhai. The number of such laws is small, and the subject matter is limited.

The second category covers regulatory documents issued by the central government or its departments. As mentioned above, the two SARs are vested with executive power to conduct administrative affairs on their own. In practice, however, the central government has involved the two SARs in several arrangements and policy documents. In particular, after the proposal of the GBA in 2015, several department documents have been issued. Among them, the most relevant authority concerning the planning of development in the GBA is the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). In 2017, the Framework Agreement in the development of the GBA was signed among the NDRC and the governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao. In 2018, the arrangements for supporting Hong Kong/Macao in fully participating in the Belt and Road Initiative were signed between the NDRC and the governments of the two SARs. Several other departments, such as the Ministry of Finance, the State Taxation Administration, the People’s Bank, the Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission, the Securities Regulatory Commission, the Ministry of Transportation, and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, have also issued documents supporting and facilitating the development of the GBA on issues concerning their competence. The most important document issued at the national level concerning the GBA is the Outline Development Plan issued by the CPC Central Committee and the State Council. It is a programmatic document for the GBA. It includes 11 Chapters: background, overall requirements, spatial layout, developing an international innovation and technology hub, expediting infrastructural connectivity, building a globally competitive modern industrial system, taking forward ecological conservation, developing a quality living circle for living, working, and travelling, strengthening cooperation and joint participation in the Belt and Road Initiative, jointly developing Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Cooperation Platforms, and implementation of the plan. It provides a blueprint for the development of the GBA and includes specific guidelines and techniques.

Based on different leading authorities, cooperation in the GBA can be divided into three types. In the first one, the central government is the leading authority. It performs as a higher-level institution and the three local governments as participants and implementing institutions. The national legislation and policies can be seen as this type. The other two types are examined in the next two sections. The current system is an embodiment of the “one country, two systems” policy. Under this system, there is debate on the legal basis of the national legislation in relation to the GBA. Because it is provided in the Basic Laws that national laws do not apply in the two SARs except for those listed in the Annex III, the documents issued by the central administrative authorities do not create a binding force on the two SARs. Some scholars argue that the non-objection or active participation of the SARs concerning the GBA policies or plans has provided ground for the central government to involve the two SARs in the plan [44]. The current system causes another problem, which is the different political pressures and incentives given by the central government to the local governments. In the mainland, the local governments are a part of the vertical institutional system. They are greatly influenced by the policies adopted by the central government and have more political incentives to implement the strategy of the GBA. In addition, the different economic systems may also lead to an unequal devotion to regional integration and cooperation as the Hong Kong government is a limited government.

4.3. Interregional Arrangements

Another important legal source for the integration and cooperation in the GBA is interregional legislation. In 2003, the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA) was signed between the HKSAR/MSAR and the mainland, which is an “FTA-like arrangement” but between “two separate customs territories of a single sovereign state” [45]. As the original CEPA only provides a general guide for the cooperation, a series of Supplement to CEPA were signed in the following several years. Under the CEPA framework, agreements concerning the liberalization of trade in services in Guangdong, trade in services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, trade in goods, and the amendment to CEPA were signed in 2014, 2015, 2017, 2017, 2018 and 2019, respectively. CEPA framework covers broad areas of trade in goods, trade in services, investment, and economic and technical cooperation, including rules of origins, tariffs, services suppliers, mutual recognition of professional qualification, investors, investment disputes, key areas of cooperation, and sub-regional cooperation. Except for agreements on economic affairs, the two SARs and the mainland have also concluded several judicial cooperation arrangements. These are mainly concerning civil and commercial proceedings, mutual services for judicial documents, mutual enforcement of arbitral awards, reciprocal recognition and enforcement of judgments, mutual taking of evidence, and mutual assistance in court-ordered interim measures.

In 2010, the Framework Agreement on Hong Kong/Guangdong Cooperation was signed by the governments of the HKSAR and Guangdong. In 2011, the Framework Agreement on Macao/Guangdong Cooperation was signed by the governments of the MSAR and Guangdong. These two Framework Agreements were directly signed between the regional governments and provide detailed and concrete provisions concerning the cooperation. In the following years, the governments have issued annual work plans or major tasks of the Framework Agreements to implement the framework with detailed measures. In addition to the agreements mentioned above, the governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao have also signed a series of cooperation agreements on cultural issues, environmental protection, intellectual property rights, customs, youth development, etc. In summary, in the GBA, interregional agreements signed by the local governments have established a comprehensive system, from general principles and guidelines to specific measures and annual work plans.

The interregional cooperation arrangements are the second type of cooperation mechanism based on agreements between local governments. The problem with the interregional arrangements is that there is no clear legal basis in the constitutional and administrative law [46]. As mentioned above, the Chinese administrative system is vertical with an obvious hierarchy. In the US, there are inter-state compacts as each state enjoys relatively independent legislative, administrative and judicial power. The institutional design in China leads to less exploration of agreement or arrangement between local governments. This further leads to a lack of monitoring mechanisms concerning the cooperation arrangements. Existing interregional agreements include both general provisions and specific measures, but there are neither strong political constraints nor legal mechanisms to guarantee the implementation of the agreements.

4.4. Local Legislation and Policies

The last domestic important legal source concerning the integration and cooperation in the GBA are laws and policies adopted by the local governments concerning the integration and cooperation in the GBA. As mentioned in Section 4.1, local governments in all three jurisdictions have legislative power subject to certain conditions and procedures. Local governments in Guangdong have issued several administrative regulations and policy documents, including the Outline of the Reform and Development Plan for the Pearl River Delta Region (2008–2020), Overall Development Plan of Hengqin, Overall Planning for the Development of the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone, Regulations on the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone, etc.

Incorporation of cooperation intension into local legislation is the third type of cooperation mechanism. However, the current situation of the local regulations adopted by the three regions demonstrate the problem mentioned above; that is, the governments in the mainland have more incentives to adopt laws facilitating the integration and cooperation in the GBA, while the Hong Kong government and the Macao government have less motivation to actively take actions. With the development of the mainland, this kind of unequal cooperation may lead to more and more problems.

4.5. International Law

Under the “one country, two systems” policy, the two SARs gain special status as separate customs territories and are able to participate in some international inter-governmental organizations with the name of Hong Kong/Macao, China. The two SARs are able to maintain signature parties of international agreements applied to them before the reunification if the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is not a party. If the PRC is a party to the international agreements, the central government of China decides whether the two SARs can maintain or become a party of international agreements. In this regard, the two SARs are able to participate in international organizations concerning sustainability issues such as the WTO and the IMO. Relevant international laws are therefore binding to the three jurisdictions and theoretically can be the legal basis for regional integration and cooperation. International law can provide important guidance for cooperation on some issues concerning sustainable development. Theoretically, some provisions of international law can be applicable for the integration and cooperation issues in the GBA. For example, the three jurisdictions can resort to the WTO dispute mechanisms if there are disputes on tariffs, etc. In practice, however, international law is rarely applicable. Its effect on the integration of the GBA is invisible since the three jurisdictions are in “one country”.

4.6. Summary

In summary, the current framework provides several legal instruments for the integration and cooperation in the GBA. The table below summarizes the available legal instruments and the existing problems (Table 2). However, some problems exist concerning these legislation and policies. Further clarification and systematization of the legal instruments are needed, and the Chinese policymakers should pay attention to these problems. In the next section, some policy recommendations are provided concerning the facilitation of integration and cooperation in the GBA.

Table 2.

Available Legal Instruments and Problems.

5. Policy Recommendations

Based on the discussion above, this paper gives several policy recommendations for the policymakers.

5.1. Improve the Implementation of the SDGs through Integration and Cooperation in the GBA

In the past several years, competition among municipalities has prevailed over coordination and collaboration in the GBA. Without an overall plan, the Matthew effect may lead to larger differences between regions [34]. To implement the SDGs, the potential of the 11 cities must be unlocked at the different development stages, facilitating the central cities’ spill-overs to benefit the neighboring areas, and improving a balanced development, integration and cooperation are necessary. The GBA covers three jurisdictions and two systems, but there are no effective regional higher-level authorities that can directly coordinate the three regions yet. Therefore, the design and planning of the regional integration and cooperation mechanisms are crucial. First, sufficient intellectual support is important. Scientific advice from different areas should be collected and assessed, especially concerning the long-run sustainability. Second, institutional construction is important. Some experience in China has shown that the establishment of a regional joint committee of the governors is a way to coordinate legal and administrative issues [47]. Periodical meetings and the exchange of information are also important. Third, equal and long-term mechanisms are needed. It has been pointed out that the incentives and activities concerning regional integration and cooperation among the three regions are unequal. This may decrease the effectiveness and outcome of the cooperation in the long run. To introduce a benefit-sharing and compensation mechanism may be a good method of addressing these issues [48].

5.2. Provide More Legal Instruments for the Integration and Cooperation

It has been more than 20 years since the reunification of the two SARs. The further legal exploration of the “one country, two systems” policy has been little. With the fast development of the mainland, especially the two big cities in Guangdong Province, both China and the GBA are facing a new stage and different challenges. With an emphasis on “law-based governance”, the development of the rule of law has been improved in China especially in the last decade. The construction of private laws and criminal law has made big progress. The development of administrative law, however, is relatively lagging. The GBA, undertaking the responsibility of “early and pilot implementation”, can significantly contribute to China’s legal construction.

First, the legislature should take a more active position adopting legislation encouraging the SARs to integrate into and collaborate with the mainland. In the past, the SARs not only performed as China’s opening windows to the world but also a proving ground for different systems. They have benefited from the reunification and the integration [49]. The situation in the GBA and emphasis of the governments have changed. On the one hand, China has been opened up more than ever and the unique advantages of the two SARs are reducing. On the other hand, the prime need of the GBA has become the promotion of integration to unlock the potential of the region as a whole. Half of the time (50 years) provided in the Basic Laws of keeping the social system unchanged has passed. An early discussion and exploration of further integration of the two SARs should be put on the agenda. Second, the legislature should provide a clarification of the status and competence of the central government and the local governments, including those of the SARs. The People’s Congress has the power to interpret legislation including the constitutional and administrative law. Clear laws and legal interpretation help to reduce ambiguity and improve applicability. Third, the legislature should explore interregional cooperation mechanisms and encourage participation of local governments [50]. Several cooperation agreements and arrangements have been concluded by the three governments. The legal basis for them, however, is not clear. There is no stipulation concerning the interregional cooperation arrangements in Chinese law and therefore neither legal basis nor monitoring mechanisms for the behavior of the participating governments can be found. Fourth, the local legislature should take more active actions to adopt local laws promoting integration and cooperation. The legislature of all three regions is granted legislative power, although to different degrees. Local governments have the most knowledge of the specific situation, local needs, and problems to be addressed. With the support of the central governments, extensive exploration of legal issues concerning integration and cooperation should be carried out in the GBA. A summary of the instruments is provided below (Table 3).

Table 3.

Recommendations concerning different legal instruments.

5.3. Establish a Complementary and Effective System Improving the Regional Integration and Cooperation

The 2019 Outline Development Plan has provided a guidance for the GBA. Its implementation, however, depends on the establishment of an effective system and the actions taken by the governments. First, different characteristics of the governments’ institutional structures should be taken into consideration. In Mainland China, the government is still exploring functional transformation and institutional reform to seek a balance between government interference and market mechanisms [51]. That being said, the mainland governments generally enjoy more power than the governments of the two SARs. The integration and cooperation in the GBA must take the different roles and competence of the governments into consideration. Second, key areas and major tasks concerning the integration and cooperation must be identified. Some issues are essential and vital, and some other issues need a long-term and step-by-step effort. The necessity of integration and cooperation on specific matters should be examined. A proportional examination should be given to assess the number of resources that need to be dedicated. For example, issues such as environmental protection and financial regulation are both important and commonly faced, and therefore should be identified as prime issues. Third, a timetable and evaluation mechanism should be established. From the experience of the integration in the EU, it can be learned that annual tasks and evaluations are very important for the implementation. The central government or a joint committee of the GBA could perform this function.

6. Concluding Remarks

At the 19th National Congress of the CPC, President Xi Jinping declared that China is facing a “new era” and is at a time point where China’s economy is transitioning from a phase of rapid growth to a stage of high-quality development [10]. This is consistent with the proposal of the SDGs of the UN. The GBA has location advantages, a vibrant economy, and special political support from the Chinese central government to explore better and sustainable development based on urban agglomeration. It is of special significance for China’s future development and opening-up. Domestically, the unbalanced development confronting the GBA is an epitome of the whole country. Many reforms and experiments are conducted first in this region and then are being adopted nationwide. Internationally, the exploration in the GBA gains China precious experience in the promotion of regional integration and cooperation. In particular, China has proposed geopolitical strategies such as the BRI and needs to seek international cooperation with societies with different economic, political, and legal structures. In this process, legal instruments are very important, as embodied in China’s recent emphasis on the “rule of law”.

This paper illustrates the integration and cooperation in the GBA and the implementation of the SDGs, with a detailed examination of the existing legal framework and identification of its problems. Based on the analysis, it gives several policy recommendations. Firstly, integration and cooperation should be promoted to facilitate sustainable development. Sufficient intellectual support, wisely-designed institutional arrangements, and equal and long-term mechanisms are needed. Secondly, more legal instruments should be adopted to support the integration and cooperation in the GBA. A more active stance on the integration of the two SARs into the mainland, a clarification of the competence and relationships between the governments at different regions and different levels, an introduction of interregional cooperation mechanisms, and better incorporation of relevant rules into local laws should be adopted by the legislature. Third, a complementary and effective system improving the integration and cooperation in the GBA should be established. Differences among regions should be considered, major cooperation areas should be identified, and a practical schedule and assessment mechanism should be introduced. China’s exploration implementing the SDGs in the GBA can shed light on high-quality development both domestically and internationally.

Funding

This research was funded by Shenzhen Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project, “Research on the Legal Path of Market Integration in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area”, No. SZ2020B027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the paper are obtained from the websites of governments of Guangdong, Hong Kong, and Macao.

Acknowledgments

The field work is supported by the following projects: China’s National Social Sciences Foundation (18VHQ002); Shenzhen Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project, “Research on the Legal Path of Market Integration in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area”, No. SZ2020B027; Economic and Social Development Research, Base General Project, Liaoning Province, China, “Research on the Legal Issues regarding Northeast Asian Energy Market Integration”, No. 20211sljdybkt-005.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- UN. Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Gustafsson, S.; Ivner, J. Implementing the Global Sustainable Goals (SDGs) into Municipal Strategies Applying an Integrated Approach. In Handbook of Sustainability Science and Research. World Sustainability Series; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, C. (Ed.) The Evolution of China’s Poverty Alleviation and Development Policy (2001–2015); Springer: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- MacGregor, S. (Ed.) Routledge Handbook of Gender and Environment; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Outline Development Plan of the Central Government and the State Council for the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, Issued by the State Council and the CPC Central Committee, Issued and Effective Date 18 February 2019. Available online: https://www.bayarea.gov.hk/filemanager/en/share/pdf/Outline_Development_Plan.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Information of the Countries Which Have Signed Cooperation Agreement with China. Belt and Road Portal. Available online: https://www.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/xwzx/roll/77298.htm (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Wang, L.; Zou, Y.; Zhu, X.; Bottazzi, M.E.; Hotez, P.J.; Zhan, B. China’s Shifting Neglected Parasitic Infections in an Era of Economic Reform, Urbanization, Disease Control, and the Belt and Road Initiative. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0006946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xi, J. The Law-Based Governance of China; Central Compilation & Translation Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency. Communique of the Fifth Plenary Session of the 18th CPC Central Committee; Xinhua News Agency: Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua Net. Xiplomacy: Xi on China’s Pursuit of High-Quality Development. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-03/04/c_139783843.htm (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- The Cities. HK Constitutional and Mainland Affairs Bureau. Available online: https://www.bayarea.gov.hk/en/home/index.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z. Report on Chinese Business Environment. 2020. Available online: https://www.gsm.pku.edu.cn/zhongguoshengfenyingshanghuanjingyanjiubaogao2020wanzhengbaogao.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Chinese).

- Foreign Investment in China. Report on the Openness Index of Chinese Regions Have Been Published: Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou Rank the Top Three. Available online: http://www.ficmagazine.com/root/11396/category3 (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Chinese).

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. The Chinese Government Resumed Exercise of Sovereignty over Hong Kong. Available online: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/ziliao_665539/3602_665543/3604_665547/t18032.shtml (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Hong Kong Trade Development Council. Economic and Trade Information on Hong Kong. Available online: https://research.hktdc.com/en/article/MzIwNjkzNTY5 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Australia Government. Chapter 5: The Hong Kong Economy. Available online: https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House_of_Representatives_Committees?url=jfadt/hongkong/hk_ch5.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- CPCNEWS. Xi Jinping: Make a Bigger Cake and Divide It Wisely. Available online: http://theory.people.com.cn/n1/2017/0608/c40531-29327169.html (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Chinese).

- HK Census and Statistics Department. Table 36: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by Major Economic Activity-Percentage Contribution to GDP at Basic Prices. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/web_table.html?id=36 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Macao Statistics and Census Service. Yearbook of Statistics 2019. Available online: https://www.dsec.gov.mo/en-US/Home/Publication/YearbookOfStatistics (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Guangdong Government. Composition of GDP (2019). Available online: http://stats.gd.gov.cn/gdp/content/post_3277949.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Zhang, J.; Yu, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, C.; Shi, T.; Wu, X.; Yang, C.; Gao, W.; Li, Q.; Wu, G. Exploring Annual Urban Expansions in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area: Spatiotemporal Features and Driving Factors in 1986–2017. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, K. Managing Subnational Liability for Sustainable Development: A Case Study of Guangdong Province. In Fiscal Underpinnings for Sustainable Development in China; Ahmad, E., Niu, M., Xiao, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. What Should Economists Know about the Current Chinese Hukou System? China Econ. Rev. 2014, 29, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, Z.; Zeng, H. Using Remote Sensing Data to Study the Coupling Relationship between Urbanization and Eco-Environment Change: A Case Study in the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shan, Y.; Liu, G.; Guan, D. Emissions and Low-Carbon Development in Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area Cities and Their Surroundings. Appl. Energy 2018, 228, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Govada, S.S.; Rodgers, T. Towards Smarter Regional Development of Hong Kong Within the Greater Bay Area. In Smart Metropolitan Regional Development: Economic and Spatial Design Strategies; Vinod Kumar, T.M., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 101–171. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, J.; Xiao, G.; Wu, C. Urban Green Transformation in Northeast China: A Comparative Study with Jiangsu, Zhejiang and Guangdong Provinces. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Du, M.; Wang, B.; Yu, Y. The Impact of Educational Investment on Sustainable Economic Growth in Guangdong, China: A Cointegration and Causality Analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, K. Central and Local Financial Relationships. Available online: http://www.npc.gov.cn/npc/c30834/202008/08bd6bb3168e4916a2da92ac68771386.shtml. (accessed on 15 June 2021). (In Chinese)

- Chen, M.; Sui, Y.; Guo, S. Perspective of China’s new Urbanization after 19th CPC National Congress. Geogr. Res. 2019, 38, 181–192. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, E. Yardstick Competition in a Federation: Theory and Evidence from China. China Econ. Rev. 2012, 23, 878–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zheng, P.; Tao, Y.; Li, Z. Competition between Local Governments and Regional Economic Development in Today’s China: A Literature Review. Rev. Ind. Econ. 2020, 5, 15–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Song, Z. Competition of Chinese Local Governments in 30 Years. Teach. Res. 2009, 11, 28–36. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rigney, D. The Matthew Effect: How Advantage Begets Further Advantage; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bank of China. 16 Provisions of the Preferential Measures for Hong Kong to Construct the Greater Bay Area and Their Impact. Available online: https://research.hktdc.com/sc/article/MzE2NDgzNjQ5 (accessed on 7 November 2021). (In Chinese).

- Perroux, F. Investigación Económica. Teorema Heckscher-Ohlin-Samuelson 1970, 30, 621–645. [Google Scholar]

- Ke, S.; Feser, E. Count on the Growth Pole Strategy for Regional Economic Growth? Spread–Backwash Effects in Greater Central China. Reg. Stud. 2010, 44, 1131–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.W. Growth Pole Spillovers: The Dynamics of Backwash and Spread. Reg. Stud. 1976, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Constitutional Issues concerning the Interregional Collaborating Legislation. China Law Rev. 2019, 4, 62–75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Haibo, H. Litigations without a Ruling: The Predicament of Administrative Law in China. Tsinghua China L. Rev. 2010, 3, 257–282. [Google Scholar]

- Mu, R.; de Jong, M.; Koppenjan, J. Assessing and Explaining Interagency Collaboration Performance: A Comparative Case Study of Local Governments in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 581–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, P.T.Y. The Changing Relations between Hong Kong and the Mainland Since 2003. In Contemporary Hong Kong Government and Politics; Lam, W., Lui, P.L., Wong, W., Eds.; Hong Kong University Press: Hong Kong, China, 2012; pp. 325–347. [Google Scholar]

- So, A.Y. “One Country, Two Systems” and Hong Kong-China National Integration: A Crisis-Transformation Perspective. J. Contemp. Asia 2011, 41, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. the Constitutional Character of the Basic Laws. Peking Univ. Law J. 2020, 1, 61–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Introduction, Overview of CEPA, Economic and Technological Development Bureau of the MSAR. Available online: https://www.cepa.gov.mo/front/eng/itemI_1_1.htm (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Ye, B. Legal Governance of Regional Integration. Chin. Soc. Sci. 2012, 8, 112–114. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Liu, J. Regional Collaborating Legislation in the Nine Pearl River Delta Cities. Nomocracy Forum 2019, 4, 223–236. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Song, W.; Deng, X. Progress in the Research on Benefit-Sharing and Ecological Compensation Mechanisms for Transboundary Rivers. J. Resour. Ecol. 2017, 8, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.; Steve Ching, H.; Ki Wan, S. A Panel Data Approach for Program Evaluation: Measuring the Benefits of Political and Economic Integration of Hong Kong with Mainland China. J. Appl. Econom. 2012, 27, 705–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Wu, F. The Transformation of Regional Governance in China: The Rescaling of Statehood. Prog. Plan. 2012, 78, 55–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. China to Further Transform Government Functions and Invigorate Market Vitality. The State Council of the PRC. 2020. Available online: http://english.www.gov.cn/premier/news/202008/26/content_WS5f46795cc6d0f7257693b1ab.html (accessed on 15 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).