LEADER Program—An Inclusive or Selective Instrument for the Development of Rural Space in Romania?

Abstract

1. Introduction

Literature Review

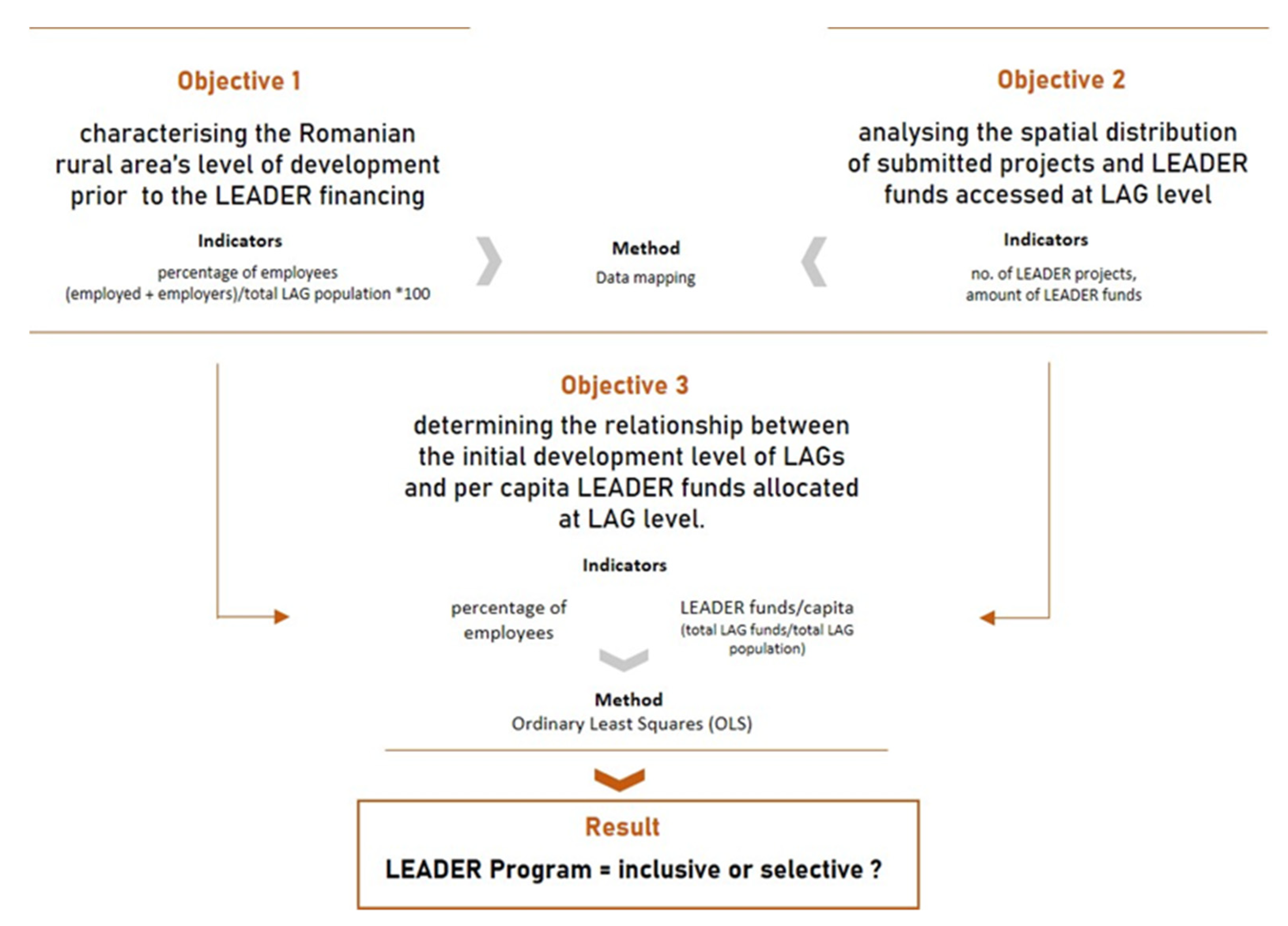

2. Materials and Methods

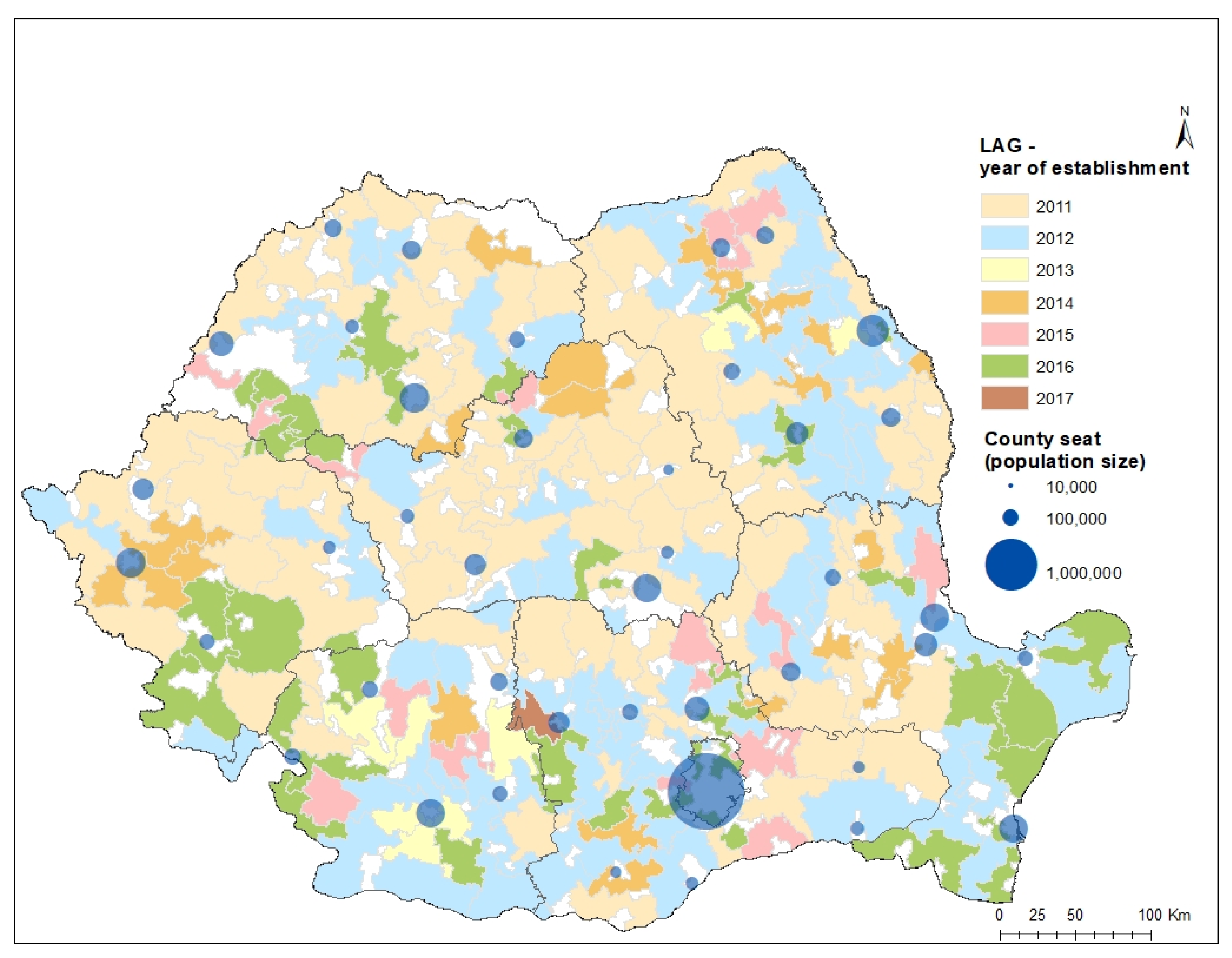

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data and Methods

3. Results

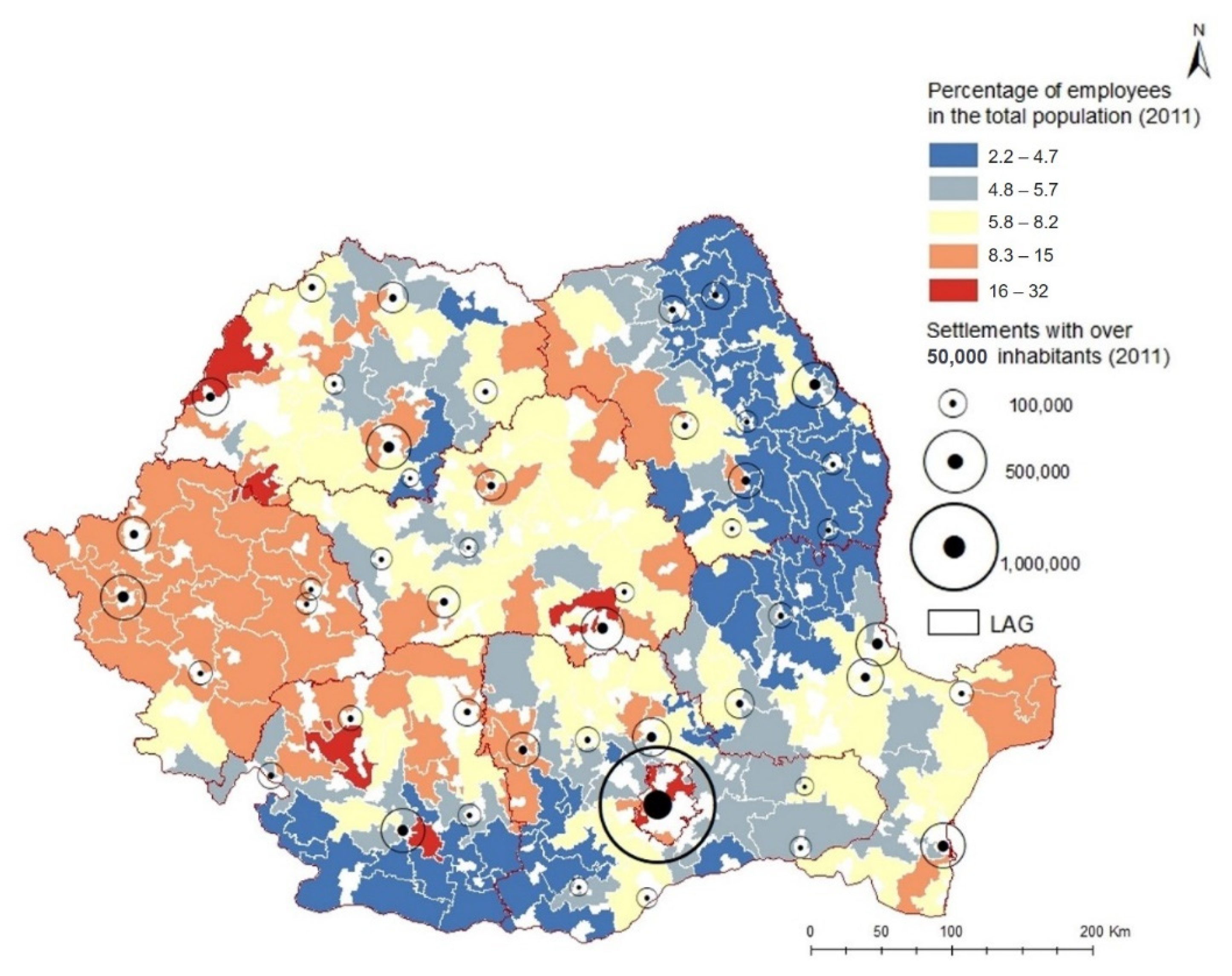

3.1. The Romanian Rural Areas Level of Development before the LEADER Financing

3.2. Quantitative Results of the LEADER Program in Romania

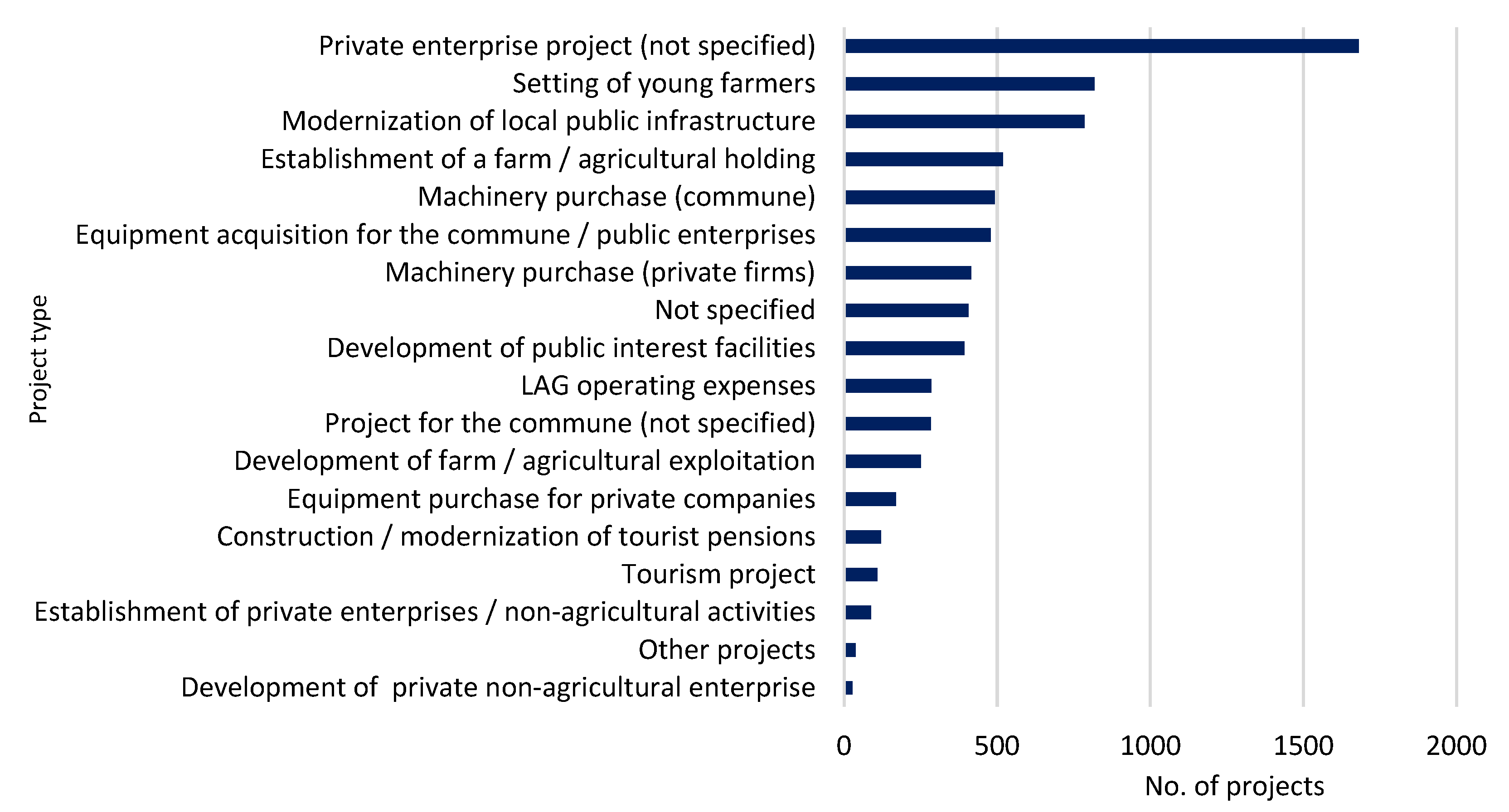

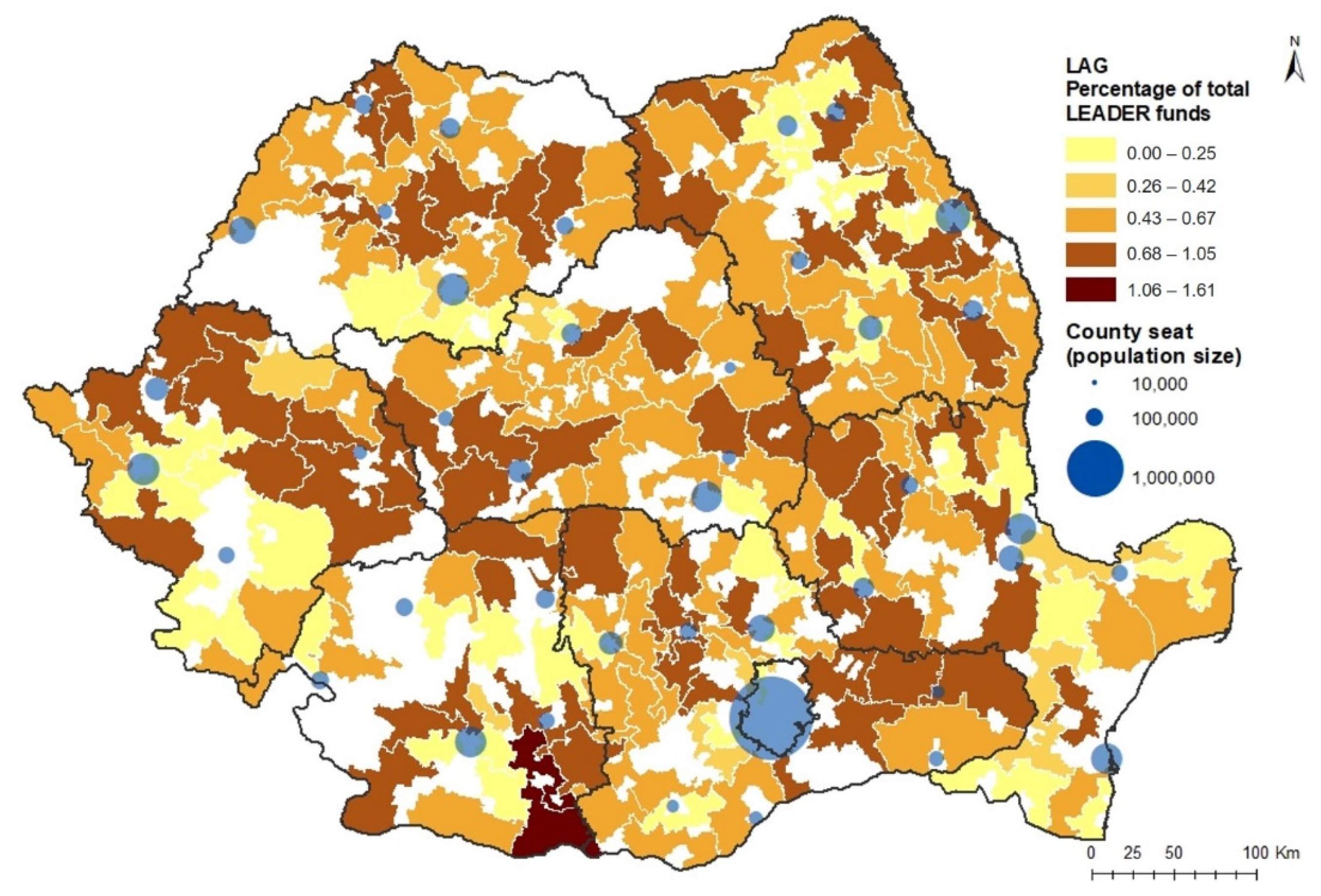

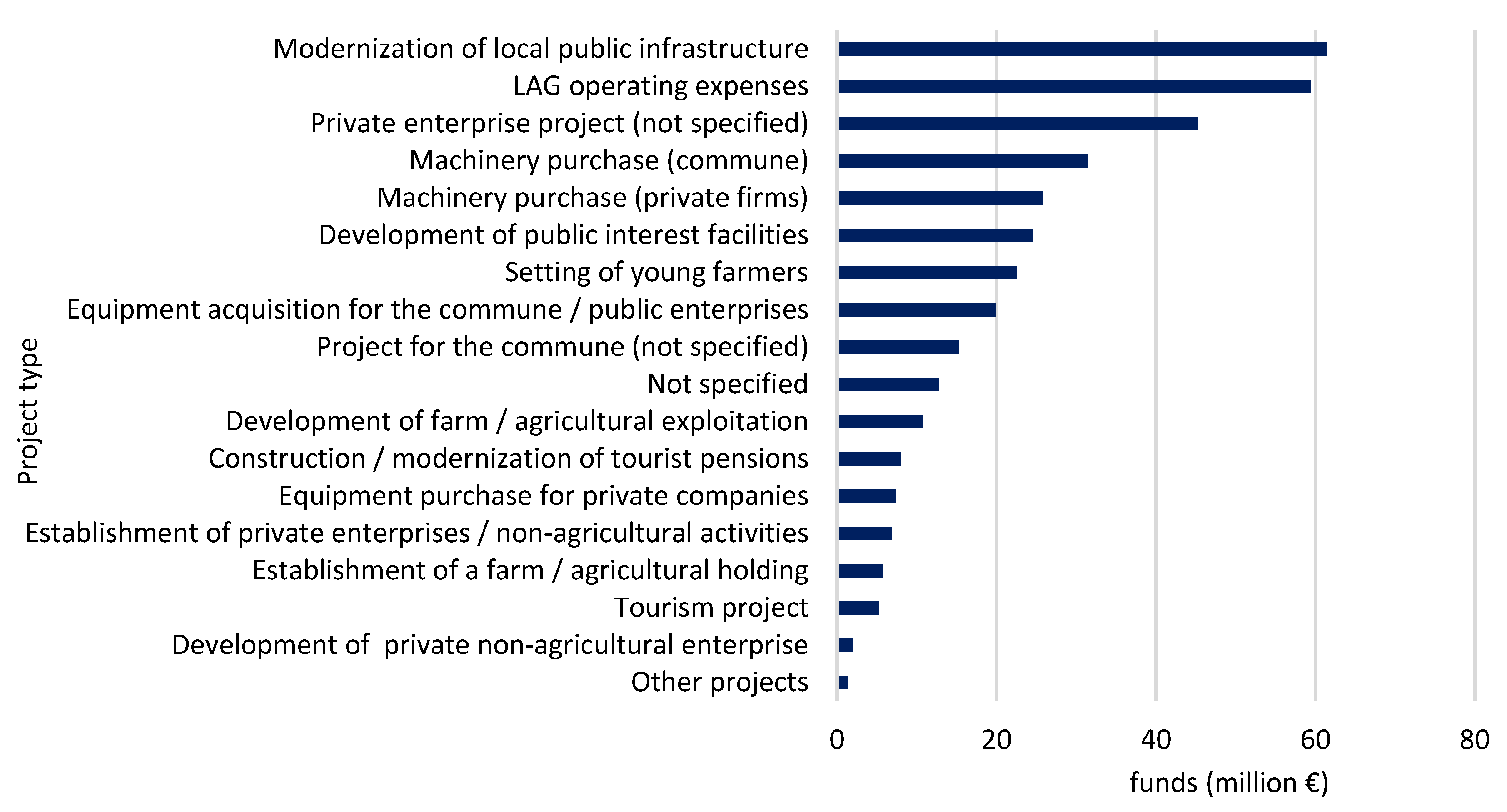

3.2.1. Type and Spatial Distribution of Projects and LEADER Funds Accessed at LAG Level in the 2007–2013 Financing Period

- the agricultural projects predominated along with public projects for the development of the local infrastructure;

- most of the funds were absorbed by public projects;

- agricultural projects managed to absorb a larger amount of funding then non-agricultural projects.

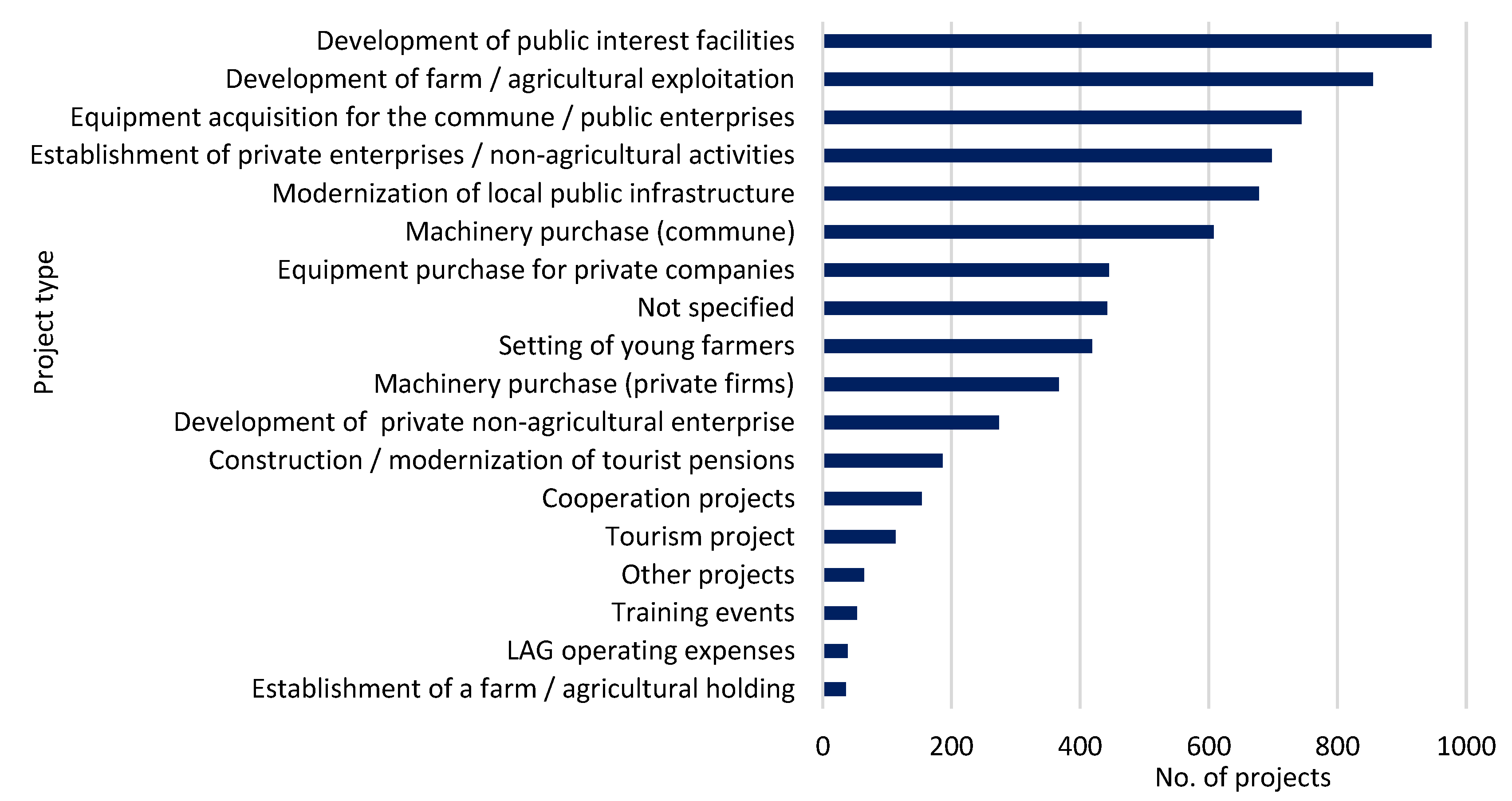

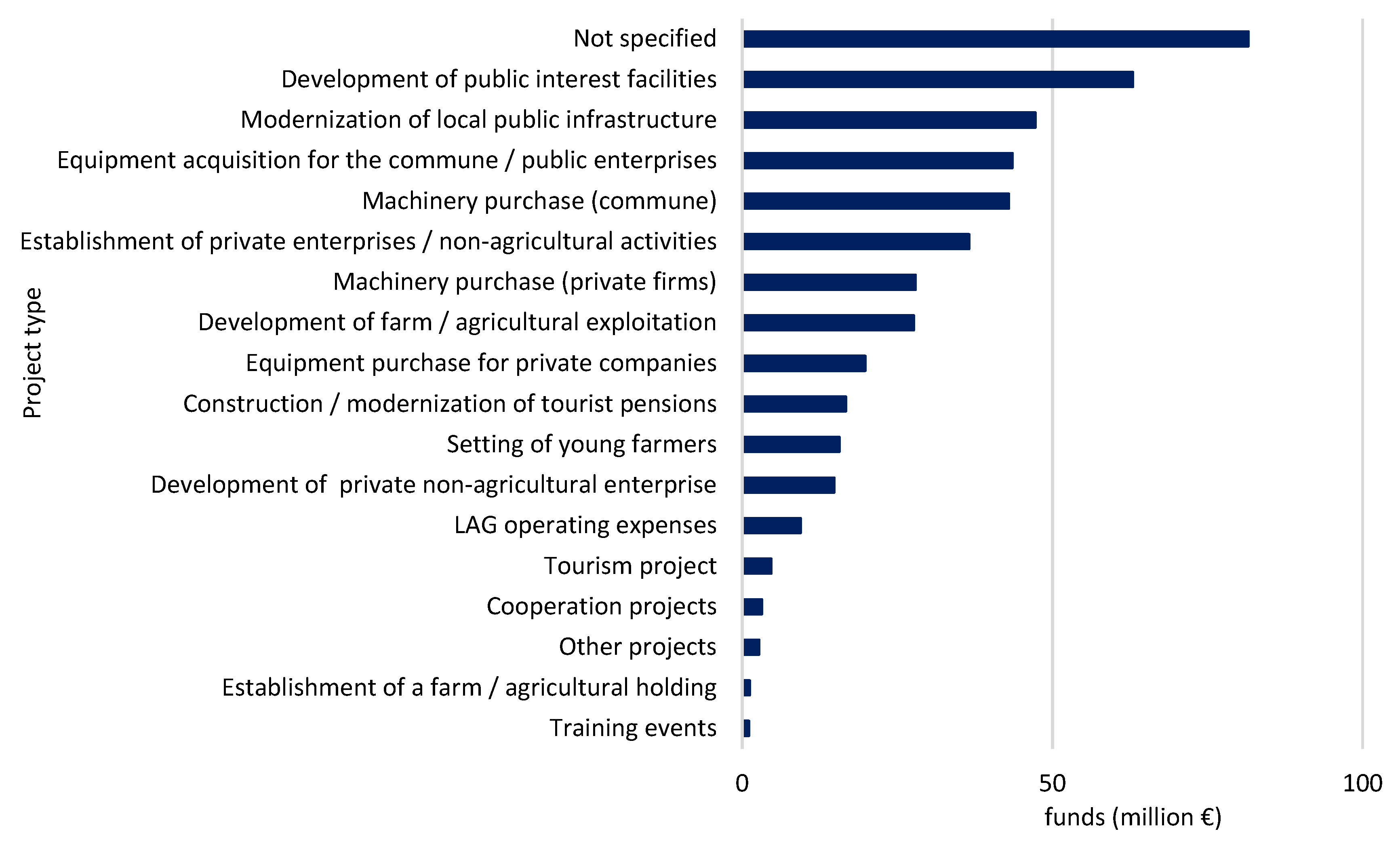

3.2.2. Type and Spatial Distribution of Projects and LEADER Funds Accessed at LAG Level in the 2014–2020 Financing Period

- the trend from one funding period to another has been to supplement the number of projects benefiting the entire local community, so that public initiatives have come to outnumber the private ones;

- if the first financing period had, in general, the role of supporting the primary sector by financing a larger number of agricultural projects, the second financing period completes it with an orientation towards non-agricultural projects;

- the distribution of funds by project categories in the 2014–2020 period reaffirms the existence of a transition from predominantly agricultural initiatives to non-agricultural activities and the increasing interest in public projects between the two periods

3.3. The Relation between the Development Level Prior to the Implementation of the LEADER Program and the Funds Allocated at LAG Level

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mihai, F.C.; Iațu, C. Sustainable Rural Development under Agenda 2030. In Sustainability Assessment at the 21st Century; Bastante-Ceca, M., Fuentes-Bargues, J.L., Hufnagel, L., Mihai, F.C., Iațu, C., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nationes. Governing Council of the United Nations Development Program, Report on the Twenty-Sixth Session (6 June–16 July 1979); United Nationes: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Erskine, J.M. Rural development: Putting theory into practice. Dev. S. Afr. 1985, 2, 368–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commision. Fact Sheet—The LEADER Approach (A Basic Guide); European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Macken-Walsh, A. Partnership and subsidiarity? A case study of farmers’ participation in contemporary EU governance and rural development initiatives. Rural Soc. 2011, 21, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopolito, A.; Nardone, G.; Sisto, R. Towards a comprehensive evaluation of local action groups in LEADER programs. New Medit 2011, 1, 43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Böcher, M. Regional Governance and Rural Development in Germany: The Implementation of LEADER+. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, O.; Sutter, O.; Wohlgemuth, S. Learning to LEADER. Ritualised Performances of ‘Participation’ in Local Arenas of Participatory Rural Governance. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menconi, M.A.; Artemi, S.; Borghi, P.; Grohmann, D. Role of Local Action Groups in Improving the Sense of Belonging of Local Communities with Their Territories. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esparcia, J.; Escribano, J.; Serrano, J. From development to power relations and territorial governance: Increasing the leadership role of LEADER Local Action Groups in Spain. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Arnason, A.; Nightingale, A.; Shucksmith, M. Networking: Social capital and identities in european rural development. Sociol. Rural. 2005, 45, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. From post-productionism to reflexive governance: Contested transitions in securing more sustainable food futures. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 29, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thuesen, A.A. Is LEADER Elitist or inclusive? composition of Danish LAG boards in the 2007–2013 rural development and fisheries programs. Sociol. Rural. 2010, 50, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, C. The EU LEADER program: Rural Development Laboratory. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacquement, G.; Chevalier, P.; Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E. Public Action and Territorial Development: The LEADER Approach in the Recomposition of Rural Spaces in Languedoc-Roussillon (France) and Andalusia (Spain). In Neoendogenous Development in European Rural Areas; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 63–87. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete, J.A.; Nieto, A.; Cejudo, E.; Cárdenas, G. Territorial Distribution of Projects Within the LEADER Approach (2007–2013) in Extremadura and Andalusia. In Neoendogenous Development in European Rural Areas; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Maroto-Martos, J.C.; Voth, A.; Pinos-Navarrete, A. The Importance of Tourism in Rural Development in Spain and Germany. In Neoendogenous Development in European Rural Areas; Cejudo, E., Navarro, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 181–205. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete, J.A.; Navarro, F.; Cejudo, E. Territorially unequal rural development: The cases of the LEADER Initiative and the PRODER program in Andalusia (Spain). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 726–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulakis, N.; Kalyvitis, S. Achieving convergence within the European Union: The role of structural funds in the case of Greece. Eur. Plan. Stud. 1998, 6, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, E. Assessing Territorial Impacts of the EU Cohesion Policy: The Portuguese Case. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2014, 22, 1960–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakucs, Z.; Fertő, I.; Varga, A.; Benedek, Z. Impact of European Union development subsidies on Hungarian regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2018, 26, 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlin, M.; Brandt, D.; Elbe, J. Tourism as a vehicle for regional development in peripheral areas—Myth or reality? A longitudinal case study of Swedish regions. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 1788–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cardenas Alonso, G.; Costa Moreno, L.M. Principal Component Analysis of the LEADER Approach (2007–2013) in South Western Europe (Extremadura and Alentejo). Sustainability 2019, 11, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cardenas Alonso, G. Método LEADER como política de desarrollo rural en Extremadura en los últimos 20 años (1991–2013). Boletín De La Asoc. De Geógrafos Españoles 2015, 69, 139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Hudečková, H.; Lošťák, M. LEADER in the Czech Republic and the farming sector. Agric. Econ.—Czech 2008, 54, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechrova, M.; Boukalova, K. Differences Among Czech Local Action Groups in Using Selected Principles of LEADER. Sci. Agric. Bohem. 2014, 46, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, J.; Tuzova, M. Factors Affecting Development of Rural Areas in the Czech Republic: A Literature Review. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 220, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, A.; Fiore, M.; Caruso, D.; Conto, F. Explaining Local Action Groups heterogeneity in a South Italy Region within Measure 311 Axis III notice of LDP. Agric. Agric. Sci. Procedia 2016, 8, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olar, A.; Jitea, M.I. Enabling Factors for Better Multiplier Effects of the LEADER Programme: Lessons from Romania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shucksmith, M. Endogenous Development, Social Capital and Social Inclusion: Perspectives from LEADER in the UK. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D.; Möllers, J.; Buchenrieder, G. Social Networks and Rural Development: LEADER in Romania. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 398–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.A.; Woods, M.; Cejudo, E. The LEADER Initiative has been a Victim of Its Own Success. The Decline of the Bottom-Up Approach in Rural Development programs. The Cases of Wales and Andalusia. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capros, P.; Karadeloglou, P. Macroeconomic Impacts of Structural Funds on the Greek Economy; Institute of Economic and Industrial Research: Athens, Greece, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Shucksmith, M.; Brooks, E.; Madanipour, A. LEADER and Spatial Justice. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 322–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. 25 Years of the Leader Initiative as European Rural Development Policy: The Case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Eur. Countrys. 2017, 9, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osti, G. LEADER and partnerships: The case of Italy. Sociol. Rural. 2000, 40, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, P.; Maciulyte, J.; Razafimahefa, L.; Dedeire, M. The LEADER programme as a model of institutional transfer: Learning from its local implementation in France and Lithuania. Eur. Countrys. 2017, 2, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, P.; Maurel, M.; Polá, P. Experiments with the LEADER approach in Hungary and the Czech Republic: Two different political rationales. Rev. d’Etudes Comp. Est-Ouest 2012, 43, 91–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teilmann, K.A.; Thuesen, A.A. Important Types of LAG–Municipality Interaction When Collaborating on Rural Development: Lessons from Danish LEADER LAGs. Int. J. Rural Manag. 2014, 10, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, A.; Tătaru, A.; Subić, J.; Kuzman, B. The Local Action Group, Local Sevelopment Model based on Community. Case Study-LGA “Land of Vineyards and Wine” Vrancea. Procedia Econ. 2015, 22, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pocol, C.B.; Moldovan-Teselios, C.; Cavicchioli, D.; Cordea, M.I. Has the LEADER programme been effective in promoting local rural development? An evaluation on two Romanian regions. AgroLife Sci. J. 2017, 6, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- European Commision. Commission Staff Working Document: Country Report Romania 2020; European Commision: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cristea, M.; Mare, C.; Moldovan, C.; China, A.M.; Farole, T.; Vințan, A.; Park, J.; Garrett, K.P.; Ionescu-Heroiu, M. Magnet Cities: Migration and Commuting in Romania; World Bank: Bucharest, Romania, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Török, I.; Benedek, J. Spatial patterns of local income inequalities. J. Settl. Spat. Plan. 2018, 2, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaba, E.; Ionescu, A.M.; Iațu, C.; Balan, C. The evaluation of the regional profile of the economic development in Romania. In Proceedings of the ASDRL Colloque, Dynamiques Territoriales, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 7 June–7 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrică, B.; Șerban, P.; Mocanu, I.; Grigorescu, I.; Damian, N.; Dumitrașcu, M. Social Development and Regional Disparities in the Rural Areas of Romania: Focus on the Social Disadvantaged Areas. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 152, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bański, J. Suburban and peripheral rural areas in Poland: The balance of development in the transformation period. Geogr. Cas. Slov. Akad. Vied. 2005, 57, 117–130. [Google Scholar]

- Patache, L.; Chiru, C.; Bebeșelea, M. Rural employment and decent work in Romania. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2018, 18, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D.; Mőllers, J.; Buchenrieder, G. Why Do We Need Networking for European Rural Development Policies? The implementation of LEADER and the National Network for Rural Development in Romania. EuroChoices 2011, 10, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, G.; Fintineru, G.; Kohler, A. Effects of EU rural development funds on newly established enterprises in Romania’s rural areas. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2020, 29, 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinho, C.; Varum, C.; Antunes, M. Structural Funds and European Regional Growth: Comparison of Effects among Different Programming Periods. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1302–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Opria, A.-M.; Roșu, L.; Iațu, C. LEADER Program—An Inclusive or Selective Instrument for the Development of Rural Space in Romania? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112187

Opria A-M, Roșu L, Iațu C. LEADER Program—An Inclusive or Selective Instrument for the Development of Rural Space in Romania? Sustainability. 2021; 13(21):12187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112187

Chicago/Turabian StyleOpria, Ana-Maria, Lucian Roșu, and Corneliu Iațu. 2021. "LEADER Program—An Inclusive or Selective Instrument for the Development of Rural Space in Romania?" Sustainability 13, no. 21: 12187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112187

APA StyleOpria, A.-M., Roșu, L., & Iațu, C. (2021). LEADER Program—An Inclusive or Selective Instrument for the Development of Rural Space in Romania? Sustainability, 13(21), 12187. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112187