1. Introduction

Urban “regeneration”, “renewal”, and “revitalization” are buzzwords used by the governments, media, and academics to essentially refer to the same process, created in response to urban land shortage and changing economic, social, and/or environmental demands [

1], while taking into account that sustainable urban development requires sustainable land uses [

2]. It denotes a planned transformation of idle, stagnating, and declining city areas that have gone through a period of disinvestment and experienced a considerable degradation of their physical and social substance and/or caused environment issues [

3]. The goals of urban regeneration projects being pursued by local governments on the path to achieving a sustainable urban development are not mutually exclusive but rather complementary, revolving around the following: to redevelop or substantially upgrade a dilapidated area; to assign new functions and make the best possible use of urban land; to shrink the city and halt unnecessary urban sprawl; to attract investments, reenergize urban economy, and enhance the city’s competitiveness; and to assist in place branding and/or reshaping of urban image [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Another objective, often well hidden behind the mentioned ones, is to conceal or dislocate deprivation and poverty [

8]. Built upon these premises and advertised as a path to “urban renaissance”, the regeneration of decaying areas has evolved into a conventional solution to various urban problems, being implemented worldwide to catalyze urban space revalorization [

9] and contribute to social, economic, and environmental sustainability of a city [

2,

10].

The demolition of dysfunctional and obsolete buildings has emerged as an integral component of the urban regeneration strategies [

3,

11], yet its scale depends on the targeted area, i.e., the choice of the approach. While the regeneration of inner-city areas and brownfield having a historic, cultural, and/or architectural significance and tourist appeal is mainly grounded on the preservation and upcycling of derelict assets but often incorporates selective (small-scale) demolition, the demolition-based approach is primarily applied to neighborhoods with substandard housing stigmatized or obsolete brownfield, also serving as a remedy for particular social, spatial, and economic issues [

12].

There are many examples of the latter approach across Northern and Western Europe and plenty of papers analyzing it. Some cities applied it to destigmatize the areas with social problems [

4]. In Amsterdam, for example, the strategy of sustainable “spatial, management and social renewal” was used in several ghettos to deal with urban segregation, replacing high-rise social housing with owner-occupied, single-family houses [

13,

14]. Similarly, the French government initiated the “Rénovation Urbaine” program to physically and socio-spatially transform and stir up economic development of 600 “most fragile” neighborhoods across the country [

15], encouraging the middle-class in-migration and utilizing demolition to “break the ghettos” and disperse “the poor” [

16] (p. 71). Many cities turned to the demolition-based regeneration in order to solve other problems that hamper their sustainable development, particularly those related to urban shrinkage [

17,

18]. For instance, the replacement of high-rise prefab buildings without realistic renovations prospects by less dense housing was performed in eastern Germany to cut down the excessive housing supply and counter high vacancy rates [

19,

20,

21]. Similarly, empty flats and difficulty in finding tenants presented the most common causes of housing demolition in Swedish cities (with the exception of Stockholm) [

22]. These approaches are associated with the sustainable “right-sizing” strategies of shrinking cities, directed towards restructuring the built environment by aligning the housing supply with estimated needs [

23,

24]. In other cases, new housing presented the driver of urban regeneration, stimulating both physical and economic improvement [

25,

26]. For instance, the housing demand in some British, Austrian, west German, French, and Dutch cities poorly matched with the existing offer; hence, the regeneration policies for downward spiraling neighborhoods involving demolition aimed to repair the local residential markets by introducing higher quality housing [

27]. The commonality of these urban regeneration projects, regardless of their formal objectives, is that they are generally initiated by the public sector, but often rely on the entrepreneurial governance model [

28], meaning that property-led private initiatives most frequently act as their driving force [

29,

30]. As urban regeneration “is about land use, particularly ways of improving the [land] value” [

31] (p. 110), the decision to demolish is thus “often influenced by land prices and market demand instead of the technical quality” of buildings [

27] (p. 544).

Central and East European (CEE) cities generally have a shorter tradition of urban regeneration. It has made its way to their policies after the collapse of state-socialism and a centrally planned land-management model, when the market economy and new power relations commenced affecting the production of urban space and reshaping the urban development agendas [

32,

33]. The urban land began being treated as a scarce and valuable resource that should be efficiently (re)allocated, as opposed to the socialist period when the uses had been assigned in the absence of land market, leaving CEE cities with the legacy of misallocated and underutilized urban space [

34]. L. Sýkora was one of the first scholars to foresee the impending trend of urban space recycling while analyzing the “functional gap” created in Prague in the early 1990s: “when centrally planned allocation of resources is replaced by allocation ruled by market forces, freely set rents influence the distribution of functions in space. Thus, functions with an inefficient utilization of space may soon be outbid by more progressive functions” [

35] (p. 287–288). With the transformation of land and property relations, the short-term functional gap was swiftly converted to the longer-term rent gap. It has ignited the urban land marketization, pressuring the local governments to come up with economically viable, investment-attracting, but also sustainable land uses and create policies and strategies for the redevelopment of underutilized, misassigned, and/or dilapidated urban space, setting off urban regeneration.

Although a growing body of literature investigates the post-socialist context of this process, identifying the similarities to the North and West European experience, it is primarily focused on the preservation-based regeneration of inner-city quarters that were underinvested and neglected during socialism [

36,

37,

38,

39], where the “race for space” among the developers was the fastest [

40]. Studies on the demolition-based approach in CEE cities are relatively scarce since in comparison to Western Europe, it has been much less frequently applied and mainly limited to the most fragile tenement dwellings located downtown [

18]. Moreover, the majority of researches comes from the countries that quickly overcame the transitional obstacles and entered the European capital flows (Central European and Baltic countries), which boosted the urban renewal, whereas the regeneration strategies of South and East European cities remain largely unexplored [

33]. This particularly refers to the cities of non-EU Balkan countries that have taken a different transitional path, lagging behind the rest of the region not just economically, with Serbia standing out in its distinctiveness. As regards the urban regeneration projects in Serbian cities, academic attention has been paid to Belgrade, mainly in the development of Belgrade Waterfront involving a wholesale demolition [

41,

42,

43,

44]. Only several researches dealt with this topic on the lower level of urban hierarchy, yet focusing on the preservation-based regeneration of the old city core [

45,

46,

47]. The paper will contribute to filling these voids.

The paper sheds light on a specific, demolition-based urban regeneration strategy wisely named permanent reconstruction, which has been launched in Novi Sad, the second largest Serbian city, to cure a plethora of urban problems that accumulated during socialism, being seen as a step towards sustainable development. It denoted the process of urban land recycling through the replacement of low-density housing by medium- to high-rise apartment buildings and affected the post-socialist development of a vast city area. Owing to rather complex post-socialist circumstances, permanent reconstruction was assigned as one of the urban development priorities and the main regime for multifamily housing construction, evolving into a driver of urban change and becoming a local hallmark and spatial imprint of the distorted transition. Taking into account that the post-socialist urban regeneration projects are context-sensitive [

48], meaning that different socio-economic and spatial contexts produce different forms of urban regeneration, the specific aims of this research are the following: (1) to explain the initiation of permanent reconstruction; (2) to identify the institutional and planning framework of the regeneration process and mechanisms that led it and analyze its dynamics through a case study; and (3) to assess the outcomes of the process from the aspect of functional, physical, spatial, morphological, and aesthetical features of the resulting neighborhood environment, with a special emphasis being put on the residents’ evaluation, and investigate its impacts on the housing market. The main research objective is to pinpoint the issues of a post-socialist entrepreneurial urban governance, primarily deriving from the distorted transition, which hampered the development of a synergistic, integrated, and locale-conscious approach to urban regeneration, as well as the implementation of a strategic control over the process of city building. The research findings suggest that, in order to deploy the concept of sustainable urban development and not only flirt with it, Serbian cities necessitate socially responsible urban regeneration policies and strategies that are developed with the public input and feedback and perceptive of the local (neighborhood) context.

The paper first provides a theoretical framework and overview of the literature on the demolition-based regeneration strategies of CEE cities, identifying their common denominators. It is followed by the outline of the research design, methodology, and materials. The subsequent part presents an in-depth and multifaceted empirical investigation of permanent reconstruction through a case study, which is structured upon the research aims. The paper then summarizes the main research findings and offers interpretative remarks and recommendations for redefining the regeneration approach in Novi Sad and Serbian cities, as well as in other CEE cities, which may contribute to the sustainability of regeneration projects, highlighting the responsibilities of the public sector.

2. Demolition-Based Urban Regeneration in CEE Cities

The urban regeneration projects involving the demolition of obsolete housing frequently presented a segment of the right-sizing strategies, as previously stated, yet many shrinking cities in CEE did not have vacancy issues owing to the housing shortage inherited from socialism, thus they were not in urgent need of extensive demolition to achieve the balance [

49]. Hence, while assigning new land uses, revalorizing urban space, and regenerating their dilapidated neighborhoods, the majority of CEE cities has been mainly focused on the physical rehabilitation and reconstruction and generally more hesitant about utilizing the large-scale demolition approach [

50] that has proven to be a time-consuming, more expensive, and more disruptive option [

51]. When applied, it often reflected the changes in the housing demand, entailing the construction of apartment buildings for the emerging affluent middle- and upper-class homebuyers who were dissatisfied with the existing housing offer and towards whom the local residential markets began orienting [

52]. Hence, the researchers often associate it with new-build gentrification [

32,

53] even if new housing does not exclusively target the upper echelon [

48].

The most radical examples of the demolition-based approach to urban regeneration in the post-socialist Europe may be found in Russia. Moscow and St. Petersburg applied it to root out Khrushchyovkas—prefab five-story apartment buildings mass-produced in the late 1950s, which have long outlasted their planned shelf life—and make room for new high-quality housing in line with new market needs. In 2017, the government of Moscow has launched the program for their replacement, generously subsiding it. Since 7,900 Khrushchyovkas were set to be torn down, displacing 1.6 million people, it was labelled as “the biggest urban demolition project ever” [

54]. Yet, as the residents are being rehoused to newly built and more spacious flats, the majority is supportive of the program [

55]. In St. Petersburg, however, the government’s initiative with the same goal had a more commercial approach and depended on private rather than public investments, offering the land to developers at discounted prices, allowing them to increase the residential densities, and relying on their commitment to relocate the residents, which has caused public dissatisfaction [

56]. Meanwhile, on the other side of the post-socialist world map, the governments of Chinese cities have taken the demolition approach to the extremes, opting for the Pruitt–Igoe model to deal with a persistent urban land shortage and the lack of housing to meet contemporary demands [

57]. Their extensive regeneration projects in many cases have resulted in class change, causing damage to the social urban landscape [

58].

The demolition of obsolete buildings in urban regeneration projects of other CEE cities is generally lesser in scale. In Warsaw, for instance, it presented the only possible solution for the renewal of many urban areas [

53,

59], but there are also examples from other CEE capitals [

39,

60,

61]. New-build gentrification has been identified in Łódź, a second-tier Polish city, where an industrial brownfield and poor-quality municipal tenements were demolished, the locals were relocated on government expense, and the land was sold to a private investor for a middle-class residential development that now juxtaposes with the remaining social housing across the street [

48]. Yet, perhaps the most studied example was the “bulldozer-shaped” regeneration [

62] of attractively located, yet blighted and stigmatized Józsefváros district in Budapest through the Corvin Promenade project [

50,

63,

64], initiated by the municipality and carried out in a public-private partnership, which unlocked the property development potential of this neighborhood, rebranded it, and closed the rent gap, but instigated a class change. More than 1,100 mostly social flats were demolished to clear the land for the construction of middle- to upper-class housing and commercial, leisure, and cultural venues, while the former residents were relocated to nearby neighborhoods and suburbia; thus, the ghettoization was displaced, but nonetheless continued. With regard to the Balkans, large-scale demolition was used in two megaprojects, both declared to be of national significance. One presented the transformation of a dilapidated military shipyard and its surroundings into a “new town” of Porto Montenegro in Tivat, Montenegro, which changed the socio-spatial identity of the whole city, also boosting its economy, yet initiating gentrification [

65]. The other is the state-led Belgrade Waterfront project, advertised by the Serbian president as a new city center to replace the slum, which is currently under construction and garners a great deal of public and academic attention, as previously mentioned. Its implementation was preceded by the adoption of lex specialis, stating that the construction of this mixed-use complex is in the public interest [

66], even though public facilities are almost non-existent. Despite a heavy public and professional criticism regarding the size, architecture, location, and socio-spatial costs of an obviously high-end development, the state violently swept away the site, whereas the public institutions tailored the conditions to match the needs of an Abu Dhabi-based developer.

What would be the common denominator of the CEE demolition-based urban regeneration practices? Hlaváček et al. argue that, despite the divergent paths and mechanisms of urban regeneration projects in CEE cities, they generally display the characteristics of entrepreneurial governance and lack comprehensiveness, i.e., have a weak relationship with the surrounding area and poorly meet the community needs, primarily due to an insufficient level of public involvement [

67]. A special emphasis is most often put on the quality, aesthetics, and appeal of the new environment with the aim of attracting desired businesses and higher-income in-movers; therefore, some academics state that the class replacement is what the majority of regeneration projects covertly advocate, regarding them as a “depoliticized euphemism for gentrification” [

9] (p. 4), and that the “slum clearance” rhetoric is used only to further disguise it [

68]. However, from the viewpoint of local authorities, the economic benefits compensate for the social costs. Holm et al. suggest that new-build gentrification “provided the first real rent gaps” in the CEE residential markets, becoming the target of property-led strategies [

48] (p. 182). Real estate developers were often the first to recognize the optimal land uses and transformation potential of dilapidated urban areas in post-socialist cities, fueling the rent gap and, consequently, urban regeneration [

33], while the role of public sector was to initiate it and make it institutionally possible. It may be said that private investments act as the engine of CEE urban regeneration projects and the residential market as their fuel, whereas the rhetoric of renewing otherwise declining neighborhoods ensures an active governmental support [

69]. Simply stated, many cities opt for “demolishing vast areas in order to present real estate developers with ‘attractive’ (i.e., large) land packages” [

70] (p. 166). All this might question the sustainability of the demolition-based urban regeneration projects in CEE and their impacts on (sustainable) urban development. As far as Serbian cities are concerned, they got caught in the whirlpool of the distorted transition that additionally empowered private investors and increased their appetites, thus fully succumbing to market pressures, which had a significant impact on urban regeneration. The Belgrade Waterfront project clearly revealed that that the actions of the public sector in Serbia related to urban regeneration are emblematic of an extremely high degree of private investors’ involvement in the planning and decision-making process, misuse of planning instruments, and disregard for the public interest [

41].

3. Research Design, Methodology, and Materials

The review of relevant literature on the demolition-led urban regeneration projects of European cities presented in the previous sections was used to identify the practices in both broader and narrower context, providing a theoretical background for the investigation of a specific urban regeneration strategy applied to the downgrading low-density neighborhoods in Novi Sad. This case-study-based research relied on a mixed methodology that combines qualitative and quantitative approaches, as it proved to be efficient in enhancing the reliability and validity of findings [

71]. The data that supported the critical analyses were drawn from wide-ranging sources—planning documentation and guidelines, local statistics and archives, city-commissioned studies, population and housing censuses, and laws, all referenced in the text.

The research structure derived from the research aims stated in the Introduction. Hence, first the context for the analyses was set by elucidating the origins and background of the regime of permanent reconstruction, i.e., the pre-transitional and early transitional backdrop against which it unfolded and grew into the urban regeneration strategy and urban development priority of Novi Sad. Grbavica was selected for the analyses as a representative permanent reconstruction (PR) zone. It presented the first city neighborhood to start extensively transforming in line with this regime, becoming the first one with an almost fully exploited regeneration potential, thus serving as a laboratory for investigating the dynamics and outcomes of the process, but also showcasing post-socialist planning and housing construction practices in Novi Sad. Following a brief description of Grbavica’s socialist development, the process was examined in relation to two phases, differentiated according to the scale and pace of regeneration, and explained through their wider contexts and mechanisms that profiled and led them. The subsequent critical analysis of the outcomes is threefold—first, it focused on the functional, physical, spatial, morphological, as well as social implications of the process (qualitative method); then on the residents’ perception and evaluation of the resulting physical environment of Grbavica and their potential mobility (survey method); finalizing with the impacts of the permanent reconstruction on the housing stock characteristics and local residential market (qualitative and quantitate method). Limitations in this paper refer to the unavailability of numerical data regarding both the pre- and post-transformational state of this neighborhood; however, the assessments were based on available material, on-site research, and survey.

The quantitative and qualitative survey data were collected in May 2021 using a combination of semi-structured paper and e-questionnaire, as web-surveys are found to be less suitable for people aged 65+ [

72]. The e-questionnaire was distributed through social networks, while the paper form was filled out on-site by interviewing randomly selected older residents in person, respecting their privacy and anonymity. In total, 170 residents aged 18+ completed the survey. The sample was pre-selected to target 1% of Grbavica’s population, which is estimated to be approximately 17,000 (publicly available statistics refer to the population size of ‘local residential communities’ [

73] that do not match the city neighborhoods in territorial terms; thus, the estimation was based on the morphology of Grbavica and the nearby neighborhood constituting the same statistical unit). The sample composition in terms of gender and age distribution generally corresponds to the population composition of Novi Sad proper [

74].

The results of mentioned analyses bring new insights on the demolition-based urban regeneration strategies of CEE cities, particularly those in non-EU Balkan countries, and offer ground for the recommendations aimed at avoiding the shortcomings of regeneration projects.

5. Permanent Reconstruction of Grbavica Neighborhood

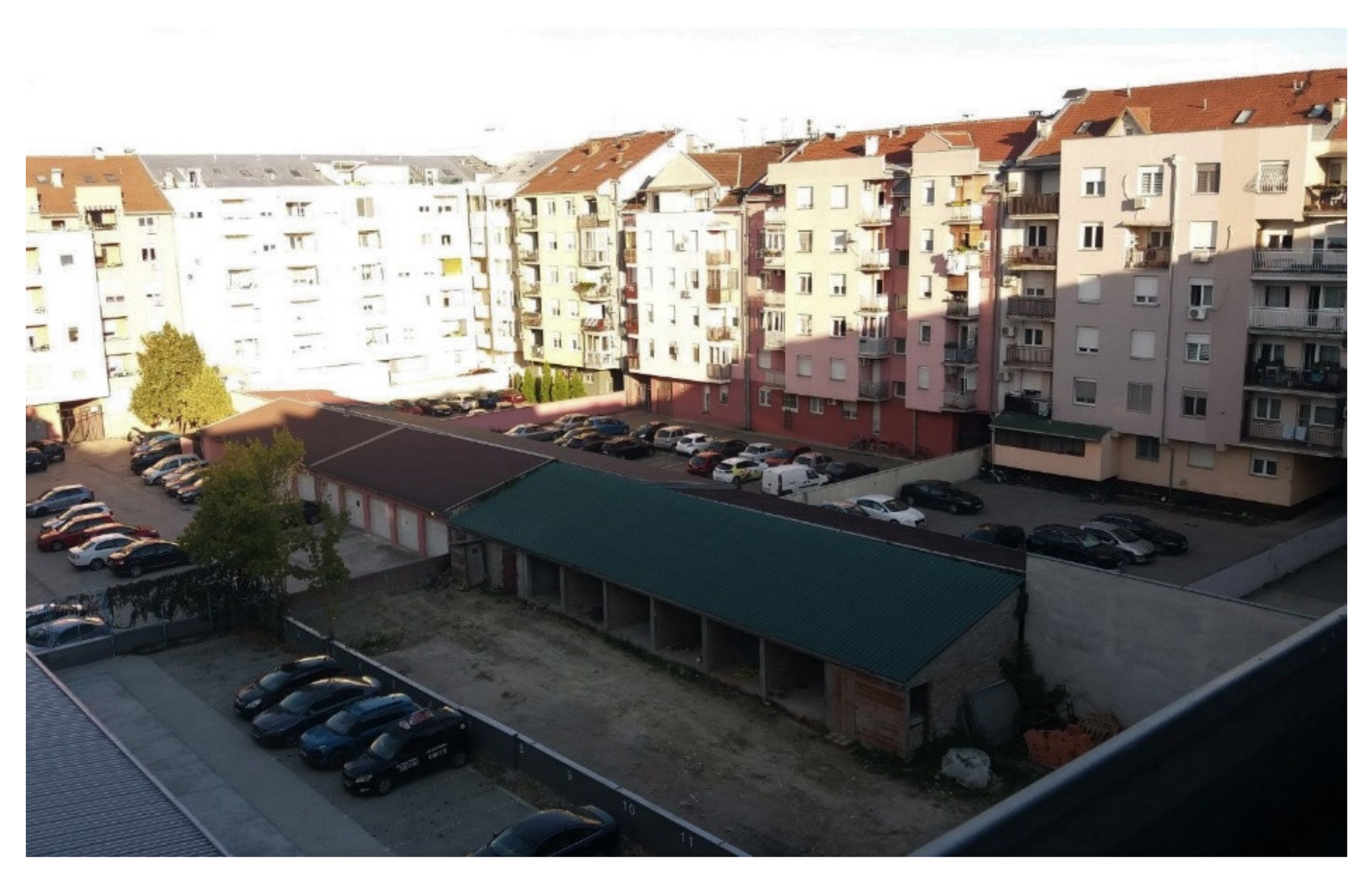

The neighborhood of Grbavica (

Figure 1) is located approximately 1.5 km from the old city core and the Danube River and currently features medium- to high-rise and medium- to high-density housing, with scattered groups of prefab apartment buildings dating back to the 1950s and 1960s and a preserved stretch of detached single-family houses on the west side, also encompassing Catholic and Jewish cemeteries. Its typological, spatial, and morphological transformation in the regime of permanent reconstruction began in the mid-1990s, and the dynamics and outcomes of this process will be analyzed in the following sections, opening with a brief description of Grbavica’s development during socialism.

5.1. Socialist Transformation

At the beginning of the socialist period, Grbavica presented a peripheral low-density and low-rise city neighborhood, conveniently positioned on the outskirts of the downtown area and characterized by the housing heterogeneity, i.e., a combination of detached and row houses of both rural and urban type on accompanied lots [

91] as well as social mix, while a share of its population was engaged with agriculture [

92]. After the 1950 master plan prescribed the “reconstruction” of infrastructurally equipped residential areas through infill development, the first prefab apartment buildings were constructed within the existing housing blocks and along the eastern border, bringing in industrial workers and middle-class members. The most ‘Haussmann-like’ intervention presented the tracing of a new boulevard that cut Grbavica off from the downtown in the mid-1960s (

Figure 2). Once the city began sprawling, the infill development ceased, and the period of disinvestment began. The neighborhood quickly found itself bordered by large housing estates on the east side yet managed to preserve the social mix. The introduction of permanent reconstruction signified that Grbavica as a well-located city district with a share of derelict housing and immense spatial potential would soon be regenerated.

5.2. The 1990s: Phase of Piecemeal Changes

The regime of permanent reconstruction was incorporated into the detailed regulation plan of Grbavica brought in 1992 [

93], stating that a significant number of its ground-floor houses was of poor quality, recommending their demolition and the construction of medium-rise apartment buildings, and thus creating the first rent gap. The plan was revised right after the adoption of the 1994 amendments [

94], stipulating an even greater extent of demolition and allowing higher building coverage and floor area ratios than the original one. The housing stock replacement began in line with this document.

The regime suited the emerging small developers, who just needed to buy a house assigned for demolition in order to lease a fully equipped municipally owned construction. It also suited the homeowners, enabling them to profit from the newly created rent gap. Despite the mutual benefit, the volume of private investments in the housing construction remained low (

Table 2) due to a severe socio-economic crisis that was generating an insufficient market demand. In addition, the regeneration Grbavica was burdened with several investor-related issues. Even though the construction requirements were loosened, the developers seldom complied with the terms of the building permits and often deliberately violated the building codes, not being granted the use permit. Furthermore, some developers would run out of money in the midst of construction, leaving the buildings unfinished. Some others put permanent reconstruction aside and focused on the development of dwelling annexes on top of the existing apartment buildings in exchange for some technical upgrading works, as it required significantly less investment than new construction. Although piecemeal and small in scale, the changes in the built environment of Grbavica became visible. Since the results of permanent reconstruction in terms of the housing output were unsatisfactory, the new regulation plan adopted in 1998 [

95] reencouraged the investors by recommending the quadrupling of dwellings in some housing blocks, enabling the upcoming hyperproduction of apartment buildings.

5.3. Post-2000 Regeneration: The Hyperproduction of Multifamily Housing

5.3.1. Context of the Delayed Transition

The authoritarian regime of Slobodan Milošević was overthrown in October 2000, initiating the delayed transition. It brought democracy, political pluralism, government decentralization, and economic recovery. However, it has also brought “proto-capitalist laissez-faire privatization and marketization,” marked by little respect for regulations [

96] (p. 440) and an extreme asymmetry of power [

97], resulting in a neoliberal transformation without social responsibility [

98]. As the investment rationale became a decisive factor in urban development, public institutions began serving the interests of private investors as financially superior, ergo the most powerful actors, and turning to clientelism [

97].

The close cooperation between the private sector and governmental bodies also started to flourish in the spatial planning domain [

99], bringing about a neoliberal planning paradigm labeled as the investor urbanism. It refers to a developer-led versus public-led planning practice that adapted and subordinated urban space to the dictates of capital, pushing the public interest into the background [

100,

101,

102]. Its mechanisms were simple—they involved either the ad-hoc adoption of new plans and amendments to the existing ones, with modifications introduced to match the investors’ needs [

100,

103] (pp. 76–80), or turning of a blind eye on non-compliances with building regulations, in both cases showing little sensitivity towards the local context. The new developer-oriented planning approach had a profound impact on the permanent reconstruction. Still, the Master Plan of the City of Novi Sad until 2021, brought in the aftermath of the hectic 1990s (2000), did not recognize it on time. This ‘umbrella’ document was created in the anticipation of the delayed transitional changes but could not have truly comprehended their complexity or foreseen how the altered socio-economic relations would have affected the urban space. During the blocked transition, Novi Sad struggled to understand the role of public policy in shaping urban future, abandoning the socialist tradition of involving the local community in the formulation of the planning objectives. The city’s spatial development has thus been guided by the investor urbanism, while the local authorities lacked awareness or simply did not care about the long-term repercussions of this approach, which became apparent as the regeneration of Grbavica progressed.

5.3.2. Influence of the Planning Guidelines and the Dynamics of Regeneration

With reference to the residential developments from the 1990s, the new master plan highlighted that the main cause of the “destruction of urban structure” was “general discontinuity (…) in compliance with the regulations” as well as that the reconstruction of Grbavica generated “great contrasts in heights and architectural expressions (…), which should be discouraged” in future [

104]. Even though in this way it acknowledged some shortcomings of the former approach to the regeneration of low-density neighborhoods, this document did not introduce any substantial changes aimed at avoiding the same scenario, assigning the permanent reconstruction as one of the urban development priorities and defining the “permanent reconstruction (PR) zones” (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, it did stipulate the minimum lot size (600 m

2) and its street front width within the zones and classify the urban parameters (maximum floor area and building coverage ratios, building heights, etc.) according to the projected residential densities but increased them in comparison to the 1994 amendments. Accordingly, the upgraded regulation plan adopted in 2003 [

105] corrected its guidelines and prescribed the preservation of the street network, overlapping of building and street lines, extensive demolition of low-rise housing almost regardless of its technical quality, and construction of apartment buildings on the accompanied lots and in closed blocks (

Figure 3). It also pointed out that the terms of the building permits had been frequently violated during the 1990s yet authorized all disputed residential developments. These updated regulations, combined with the absence of non-compliance penalties, presented both formal and informal construction incentives, acting as catalysts for further regeneration of Grbavica.

The political and macro-economic stabilization on the national level and unexpectedly swift revival of the local economy but most importantly the sale of several giant breweries in northern Serbian cities, in which the local population held valuable stocks, all aided in increasing the housing demand in Novi Sad and generating a critical mass of small private investors needed to spur permanent reconstruction. As a result, in 2004, the housing output finally exceeded the 1980s annual average [

88].

In order to additionally stimulate the housing construction industry, the 2006 amendments to the city’s master plan [

107] increased the projected population in the PR zones by 10 to 15%. They also reduced the minimum lot size by 15 to 20%, depending on the stipulated residential density, yet enlarged the lot floor area ratios and building heights, thus enabling a greater densification. However, the amendments brought some improvements to the regulations. With the aim of preventing the mistakes made with dormitory-like large housing estates from happening again, a share of new developments was required to have non-residential uses in the ground floor. Furthermore, this document provided more strict lot arrangement instructions. It acknowledged the issues of parking availability and lack of greenery on the lots, obliging the investor to provide one on-site parking spot per 70 m

2 of gross dwelling area (previously per dwelling unit) as well as to submit a landscaping proposal when applying for the building permit. All the adjustments from the amendments were incorporated into the updated plans of detailed regulation adopted in 2006. Although recognizing that the volumes of some newly constructed apartment buildings were larger than prescribed and that certain housing blocks were on the verge of becoming overbuilt, they further increased the projected population densities for some blocks, setting them even higher than in the large housing estates (e.g., 525 inhabitants per hectare [

108]).

Since the ‘appeal of living in a city’ deriving from the socialist times endured, the demand for flats in the PR zones kept increasing, being additionally boosted by the introduction of mortgage loans; thus, the construction of apartment buildings guaranteed fast return on investments, becoming the most yielding economic activity in the Vojvodina province. Due to an extremely (neo)liberal investment climate, Novi Sad experienced a housing boom [

46], and by the end of the decade, its housing output reached almost 50% of the total in the province (

Table 2). Meanwhile, Grbavica evolved into the city’s top real estate investment destination, primarily owing to its attractive location, which increased the investors’ demand for houses assigned for demolition, widening the rent gap. The homeowners in Grbavica also benefited from the redefinition of land property rights introduced by the 2006 Constitution, as their lots were not burdened with unresolved ownership and delayed restitution. These new circumstances put them in the position to overprice their houses, similarly to the landlords in CEE cities with land shortages, who were charging developers a “private tax” of up to 50% of the housing price [

109] (p. 79). As bank loans had high interest rates, the private investors frequently lacked financial resources to cover both the costs of housing/land acquisition and housing construction. Hence, the homeowners were most often compensated in kind, while the flats were pre-sold, meaning that the largest share of housing developments in Grbavica was co-financed by the future dwellers. With all these stimulants, the housing production in the PR zones intensified to the extent that the housing output surpassed the demographic growth until the end of the decade—the city’s total housing stock enlarged by nearly 50% since 2002 and had an almost 20% surplus (

Table 2), meaning that the residential market was oversupplied. Such discrepancy between housing supply and demand often induces market crash [

110], which was omitted solely due to a subsequent sharp reduction in the housing output.

As regards the official analyses at this point, the city-commissioned housing study published in 2009 shyly stated that the number of completed dwellings in Grbavica was greater than stipulated [

111]. Some new housing blocks already featured “extremely high population densities” of over 500 inhabitants per hectare (p. 12), and some lots had “extreme values of urban parameters” (p. 70). While this implied that the approach to permanent reconstruction needed to change, the study explicitly stated that “there is no room for planned interventions to decrease the densities and improve the dwelling conditions” in the PR zones, adding that any increase in the prescribed urban parameters “should be avoided” (p. 110). Although all the plans relevant to the regeneration of Grbavica also criticized the spatial outcomes of the regime, the use permits for newly constructed buildings were granted regardless of their non-compliance with the regulations.

After 2011, when 2122 dwellings were completed, the housing output began decreasing because of the extended impacts of the global economic crisis and accompanied national recession, plummeting to 705 in 2015 [

88], which significantly reduced the overall intensity of permanent reconstruction. By that time, Grbavica was almost completely typologically, morphologically, and spatially transformed.

Following a five-year slowdown, 2016 finally brought about an upturn. Compared to 2015, the housing output surged by 44%, and the local housing market recorded a 73% increase in the sales volume [

112], which marked the beginning of another, still ongoing housing boom (

Table 2). In 2019, 3,282 dwellings entered the market [

88], and the sales volume reached 5,691 (the COVID-19 pandemic decreased the 2020 volume by 5%, yet the construction sites remained active during the lockdown) [

112]. The second housing boom is now being driven by the extensive economic rural-to-urban migrations, easing of the ‘Belgradization’ process, introduction of affordable mortgage loans, and major boost in short-term rentals but most importantly by ‘tele-urbanization’ (i.e., remote purchase of housing [

113]) from the Republic of Srpska and rapid growth of the local IT sector that provides highly paid jobs. Recent housing construction trends point to a single-investor or corporate financing and a gradual shift to more high-end, large-scale developments, either greenfield or within the former moderate intensity PR zones, as the regeneration potential of Grbavica and other high intensity zones has been almost entirely exploited.

5.4. Physical, Spatial, Morphological, and Architectural Implications

The introduction of permanent reconstruction signified a fundamental shift from the socialist concept of large housing estates to the revival of the pre-war, closed-block structure, which could have been categorized as a positive change in the city’s spatial (re)development policy. The regime initially seemed as a well-thought-out and sustainable urban regeneration strategy that would halt the urban sprawl, recycle the underutilized land, bring compactness, redefine the land use and management model, eliminate the obsolete housing stock, propel the housing construction, and improve the dwelling quality in disinvested low-density neighborhoods. It also seemed as a tool for the articulated production of new urbanism and new architecture to reorganize the urban space and reenergize the monotonous and dispersed socialist urban fabric.

In general, permanent reconstruction did densify the urban fabric, making it more compact, revalorizing the urban space, erasing the urban-rural dichotomy, and achieving efficient and sustainable land uses. However, multi-story apartment buildings developed upon relatively narrow lots inherited from predominantly ground floor and single-story housing, which determined the morphology of regenerated Grbavica (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). Even when the investors were obliged to join lots (if “the area and street front width” of a lot “does not meet the criteria and conditions” for permanent reconstruction [

108]), this was seldom the case; thus, their sizes and shapes did not fit the new housing typology. As investor urbanism is solely profit-driven (pp. 91–93, [

103]), the developers were guided by the imperative of fully exploiting the available space; hence, the resulting physical structure of Grbavica is characterized by overbuilt lots, i.e., larger than optimal floor area and building coverage ratios, as well as building higher than planned.

In reference to the dwelling quality, the investors were generally disobeying the basic designing principles related to the spatial organization and functionality of dwellings or room sizing (e.g., offering “comfortable” two-bedroom apartments of 60 m

2 or “spacious” four-bedroom ones of 85m

2 [

115]), as well as the building codes (e.g., interior wall thickness) and frequently applying cheaper materials (e.g., for cladding, thermal insulation, and soundproofing). Simply put, they were more concerned with fitting in more flats and lowering the costs of construction than meeting the dwelling standards, let alone raising them. In addition, the city had no physical upgrading program for the infill housing deriving from the socialist period and their technical condition kept worsening.

The regime additionally aimed at redefining the socialist ownership, management, and maintenance model for inner-block open spaces. The undefined lots in large housing estates formed an abundance of open public spaces; yet, they were progressively decaying due to the lack of adequate management and maintenance in the jurisdiction of public utility companies that run on tight budgets [

116]. Permanent reconstruction re-introduced the pre-war concept of “multifamily housing on the accompanied (semi-private) lots,” putting investors in charge of the lot arrangement and leaving the maintenance to new homeowners, in line with the principles of condominium ownership. However, the landscaping and on-site parking requirements were too demanding for the unoccupied area of lots. The developers primarily opted for neglecting the former and partially complying with the latter since there were no penalties for not meeting the landscaping minimum, whereas a fine of 1,700 euros was charged per each unsupplied parking spot—cumulatively still way below the cost of basement garage construction (the local government increased it to 17,000 euros recently, in 2019). Hence, unoccupied areas of already overbuilt lots became organizationally and functionally subordinated to parking provision, leaving the majority with scarce greenery (or almost without it, as in the case of other PR zone,

Figure 6), while the ratio of registered cars and parking spots in the majority of housing blocks was far above 2:1. With the aim of solving the evident parking issue, in 2019, the local government authorized the demolition of several vacant buildings in municipal ownership for the construction of public garages but also a kindergarten and cultural and educational center; yet, these projects have been put on hold.

In comparison to the rigid CIAM urbanism that promoted detached and almost randomly distributed apartment buildings within large housing estates, denying the traditional concept of a street, the reinstatement of the pre-war urbanism could have been considered as an attempt to give the street back its former significance. Nevertheless, permanent reconstruction advocated the overlapping of building and inherited street lines, producing canyon-like corridors with profiles that can barely meet the needs of motor traffic, let alone provide space for cycling infrastructure, greenery, and wide sidewalks to upheave the neighborhood social life (

Figure 7). The street sections also delayed the development of the public transport line that would run through this neighborhood and the solution was found as late as 2014. On the plus side, in contrast to large housing estates that still have a shortage of daily venues, Grbavica’s main streets host a multitude of shops, services, hospitality venues, and small businesses, meaning that the requirement related to incorporating non-residential spaces in the ground floors of new buildings appeared to be profitable for the investors.

In addition, as the existing parcellation was mainly preserved, the fragmented inner-block structure consisting of fenced semi-private courtyards, primarily intended for parking, hampered the development of an auxiliary network of pedestrian pathways. The plans also omitted to allocate land for outer-block open public spaces, including playgrounds and sports fields, as well as green spaces. Their larger patches still enclose the modernist infill housing that remained unaffected by permanent reconstruction, presenting green public “islands” within a densely built urban fabric (

Figure 5 and

Figure 8). Consequently, in the city-funded study on green spaces, Grbavica was singled out as one of the “most problematic” city neighborhoods that lacks open public spaces and “every type of greenery” [

117] (p. 32).

With regard to the production of new architecture and new aesthetics, the local architects began abandoning the socialist formalism and minimalism in the 1980s [

118]. The change in the architectural expression continued with the transition; however, it went in the wrong direction. Style-wise, the attempt to redeem the city for neglecting its tradition during socialism has created an architectural euphemism for “citing [its] history” through postmodernism [

115] (p. 66). The apartment buildings constructed in Grbavica in the late 1990s are characterized by the imitation or misinterpretation of the pre-war architecture and production of quasi-historical artifacts. Although the master plan of 2000 emphasized that such architectural expressions should be averted, the relevant institutions showed no interest in stylistically regulating or controlling the designs. Hence, the post-2000 architecture of Grbavica represents merely a by-product of the developers’ race for square meters. It incorporated a cacophony of colors and architectural styles originating from the aesthetic preferences of numerous developers involved with the regeneration, fitting to the definition of “turbo-folk” style [

119] or giving rise to mediocre postmodernism (

Figure 9). On the one hand, such architecture resulted from the architects being almost completely excluded from the designing process and degraded to draughtsmen. On the other hand, the architects themselves were impatient to embrace the “more is better” concept yet were unable to effectively import the contemporary Western styles similarly as in Bulgarian cities [

120], frequently becoming accomplices to the architectural failures. As in all CEE cities, the architecture of new neighborhoods did bring variety and color to monochromatic and dull socialist urban fabric [

121]; however, Grbavica’s multicolored street fronts, enriched with a spectrum of redundant decoration (locally known as “parrot buildings”), have created a cheerful, but overbearing chaos that soundly contrasts with the repetitiveness of the nearby socialist housing stock, leading to the loss of architectural and visual identity.

5.5. Social Aspects of Regeneration: New-Build Gentrification?

As stated, the studies frequently associate the demolition-based regeneration in CEE cities with slum clearance, followed by new-build gentrification, even when involving the construction of middle-class housing; yet, the case of Grbavica slightly differs.

Although a share of its housing stock was of relatively poor quality, this neighborhood did not present a ghetto but featured social mix, having the families of blue-collar workers and middle-class members living side by side. Furthermore, permanent reconstruction has caused only temporary displacement since a vast majority of the landlords was compensated in kind, as a rule extremely generously, and later returned to the same location. According to Gentile et al., this is what any regeneration project encompassing demolition inevitably brings about until the new buildings get completed, “by which time the existing community structures will have broken down anyway” [

113] (p. 142). In addition, the regeneration of Grbavica did not require beautification of the new environment—quite the opposite, it showed no concern for the aesthetic component of the designs. This may be attributed to the limited financial resources of private investors and the majority of homebuyers at the time. Finally, when discussed against the backdrop of new-build gentrification, there is a difference in the real estate target audience between the two post-socialist housing booms in Novi Sad. The majority of recent demolition-based developments (some under construction) comes in the form of residential and mixed-use complexes that have “green” and luxury-sounding buzzwords in their names (e.g., park, garden, avenue, and palace), used to market a kind of suburban dwelling quality mixed with upscale housing and emphasize a “value-conscious distinction” [

48] (p. 178). They nowadays feature the most expensive flats in the local market [

122] and target the upper echelon of homebuyers, meaning that these high-priced, large-scale projects will eventually truly gentrify the neighborhoods hosting them, if not already done. In contrast, the small-scale developments in Grbavica or other PR zones, which date back to the first housing boom, catered to all types of housing demand, offering modestly equipped studio apartments located right across the hall from luxurious and spacious dwellings. Whereas there is no official data on the social composition of Grbavica, it may be assumed that its current population consists of the former landlords and their inheritors, first-time homebuyers belonging to different social classes, including the ones who sold a larger privatized flat to purchase a smaller one, as well as those who were in search of more comfort during the first housing boom, but also students, newlyweds, and young professionals as tenants, as a significant share of smaller flats has been bought for renting. The permanent reconstruction did bring new residents, mostly belonging to younger age groups, thus changing the social landscape of the neighborhood; yet, in the context of new-build gentrification, this process in Grbavica might be referred to as preliminary or foreshadowing, even pioneering, especially when compared to more recent demolition-based residential developments in the city.

5.6. Residents’ Evaluation of the Resulting Dwelling Environment and Their Potential Mobility

The subjective perception and the “objective reality” in terms of actual condition, state, and presence of neighborhood attributes frequently do not match [

123], the former being more relevant [

124,

125]. Hence, the survey involving 170 respondents aimed to determine how the residents, as the end-users of a renewal that significantly affects their daily life [

2], evaluate specific features of the resulting physical environment and what they see as the advantages and disadvantages of regenerated Grbavica and to disclose potential mobility but primarily to check if their perception corresponds to previously analyzed physical and spatial outcomes of the process.

The questionnaire was based on the previous surveys of residents’ satisfaction with their neighborhood environment [

125,

126], with the addition of questions aimed at revealing what the respondents particularly appreciate or see as problematic in Grbavica and disclosing their relocation intentions [

127], as residential (dis)satisfaction and mobility are found to be closely linked [

128]. It was divided into four sections. The first section provided relevant data on the respondents’ profile—gender, age, length of residence, and tenure status. In the second section (14 close-ended questions), the respondents were asked to score 13 specific physical features of their neighborhood using a five-point Likert scale, with 1 being the lowest and 5 the highest grade, as well as to give it an overall grade (one item). In the third section, they were asked to state major pros and cons of dwelling in Grbavica (two open-ended questions to avoid suggestiveness), while in the fourth section, they needed to answer whether or not they would move out and if yes, to which neighborhood and why (one close-ended and two open-ended questions).

The sample composition was as follows: (1) gender—females participants were more prevalent than males (54.7% and 42.4%, respectively; 2.9% did not specify); (2) age—with the exception of 26–40 age group that constituted 31.2% of the sample, other groups were more evenly distributed: 18–25 (11.8%), 41–50 (17.1%), 51–65 (21.2%), and 65+ (17.6%), while 1.1% of the respondents did not specify; (3) length of residence—1.2% of the dwellers surveyed reside in Grbavica less than 5 years, 37% between 5 and 15, 25.3% between 16 and 25, and 14.1% more than 25 years (2.4% did not specify); (4) tenure status—72.9% of the respondents own their flat or have a household member who is a homeowner, while 22.9% are tenants (4.2% did not specify).

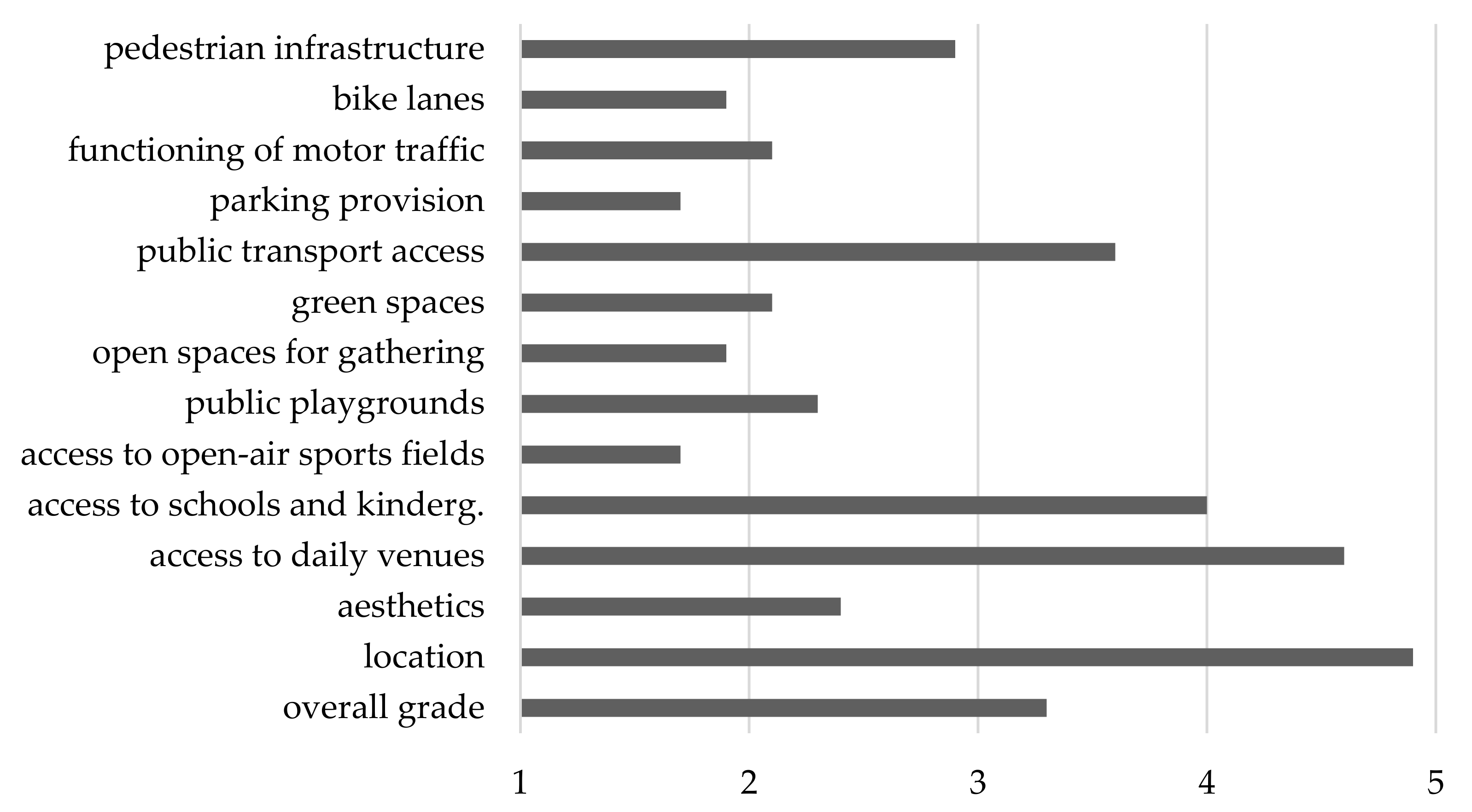

Expectedly, location and access to daily venues scored the highest among all itemized features (

Figure 10), also being seen as the key advantages of Grbavica (30.6 and 84.7% of the respondents, respectively, for location including those who answered with “proximity of” or “walking distance to” the city center/university/shopping mall/Danube). The participants were also highly satisfied with the ease of accessing kindergartens and schools; the access to public transport scored slightly lower.

The subjective evaluation of other planning- and design-related features corresponds to the disadvantages of Grbavica that the respondents were profusely enumerating (open-ended question). Even though some answers were more particular and descriptive, the prevalent cons may be categorized in the following way: traffic volume (jams) and noise—57%; parking availability—53,6%; lack of open public and green spaces—48.2 and 71.8%, respectively; lack of cycling infrastructure—27.1% and safety from crime—11.2%. The safety aspect, although not expected to be problematic, may be associated with recent incidents in Grbavica (shooting and car bomb explosion). The respondents also referred to some other issues, such as narrow streets and sidewalks, overcrowding, small distance between neighboring buildings, and illegal construction as well as “ugly architecture” and poor quality of buildings. On the other hand, they were much more restrained while stating the advantages of their neighborhood (open-ended question). Apart from its location and a variety of commercial venues, the other pros that described it as a peaceful (8.2%), green (5.3%), or appealing (4.1%) neighborhood were far less represented. Actually, the vast majority of the respondents stated just one advantage, and for 4.7%, Grbavica did not have any.

The assessment of the respondents’ potential mobility also pointed to a rather moderate residential satisfaction. Grbavica was perceived as the neighborhood of preference by 51.2% of the dwellers surveyed. Those willing to move out (48.8%) would primarily opt for the nearby (47%) or peripheral (10.8%) large housing estates, seeing them as greener, less crowded, and well planned; the downtown area because of the location (19.3%); and single-family neighborhoods because of the housing typology (15.7%). The potential mobility was the highest in the 26–40 age group and lowest in the 65+ group (

Table 3), which confirms the thesis that older residents are less likely to move out than younger ones even when being rather unsatisfied with the neighborhood environment, primarily due to generally lower expectations and difficulties in getting accustomed to changes [

124].

In reference to the length of residence, the respondents who moved in during the first housing boom or after were more willing to relocate than those dwelling in Grbavica for more than 15 years. This implies that the long-term residents have more successfully adapted to the new physical environment and dwelling concept than the newcomers, confirming that neighborhood attachment strengthens over time, i.e., length of residence positively influences residential satisfaction [

129], diminishing relocation intentions. As regards the tenure status, the homeowners were more likely to continue dwelling in Grbavica than the tenants (55.6 and 35.9%, respectively), for whom it serves as a housing market springboard, which is in line with the findings that renters are frequently less attached to both the flat and the neighborhood [

130].

In general terms, the survey results correspond to the to the observations outlined in the

Section 5.4, meaning that the respondents were well aware of the condition, state, quality, and (un)availability of certain physical features of their neighborhood. The overall grade that the dwellers surveyed gave to Grbavica diverged from other scores (

Figure 10), being slightly higher than anticipated; however, this discrepancy may be attributed to the psychological phenomenon of “sunk cost fallacy,” defined as a greater tendency to pursue an option once an investment in time, money, or effort has been made [

131], in this case, dwelling-related. It might have affected the respondents’ perception, making them more biased towards their neighborhood when separately grading it. Yet, the stated disadvantages and the potential mobility revealed the level of residential (dis)satisfaction, additionally highlighting the issues arising from permanent reconstruction and pointing out that Grbavica has not been strategically regenerated.

5.7. Impacts on the Housing Stock and Residential Market

As previously mentioned, Novi Sad (city proper area) has entered the transition with 66,257 housing units (383 per 1000 inhabitants) and an insignificant housing surplus, while the average size of dwellings was 58.6m

2 (21.4m

2 per inhabitant,

Table 1). Its residential market up until the early 2000s would have been classified as “tight” according to Kovács’s and Herfert’s typology [

132], meaning that the housing stock was undifferentiated and characterized by a minimal nimiety and immense share of dwellings dating back to the socialist period (80%,

Figure 11), that the housing options were limited, and that the residential mobility was extremely low.

In the course of the blocked transition, the number of dwellings increased by 7504 (21%), primarily because of a high volume of illegal construction, whereas 55,000 housing units (69%) that entered the market between 2002 and 2021 presented as a direct result of the permanent reconstruction (

Table 1). More than 65% of them were completed by 2011, during the first housing boom. This considerable enlargement of the housing stock halved the socialist share (

Figure 11) and raised the number of dwellings per 1000 inhabitants, with which Novi Sad has even surpassed some CEE capitals. In addition, as the tax revenues collected from the developers were directed towards improving the communal infrastructure, 99% of the housing stock nowadays has access to piped water and sewage (2011 Census data). The permanent reconstruction has also produced flats of various sizes and levels of equipment to meet all budgets and demand types, differentiating the housing stock, diversifying the housing offer, and thus substantially relaxing the market, also significantly increasing the residential mobility. The peak in the dwelling area per inhabitant (28.6 m

2 in Novi Sad proper, 36.6 m

2 in Grbavica [

111], p. 75) in comparison to the average dwelling size (dropped to 52.6 m

2, in Grbavica 48 m

2, p. 75) solely confirms that the housing output, boosted by the permanent reconstruction, exceeded the demographic growth during the first housing boom. The subsequent reduction in the housing output aided in stabilizing the residential market and prevented its collapse.

As the residential market was relaxing, the perception of large housing estates as the “dwelling ideal’” [

127] began changing, and their popularity, especially of those more peripherally located, decreased. In contrast, the demand for dwelling in the PR zones kept increasing, reinforcing their market position. According to the data on the asking prices of flats in June 2021 [

122], they hover around the city average (1542 €/m

2), while in line with the real estate mantra “location, location, location,” Grbavica is the most expensive one, ranking right behind the downtown area, with the average of 1645 €/m

2. Even though the survey results cannot justify its market position—in fact, quite the opposite, with the exception of the location criterium—the attractiveness and appeal of Grbavica may still be explained: (1) Newly constructed apartment buildings are generally perceived as of higher quality in comparison to socialist developments. (2) Newer flats do not require renovation investments. (3) Grbavica and other PR zones provide much more dwelling options than large housing estates. Although the average size of dwellings completed during the 2000s in these zones fell below 50m

2 [

111] (p. 58), indicating a considerable share of studio- and one-room apartments in the new housing stock and revealing the profile of the then market needs, the ongoing housing boom is propelled by a demand for more spacious and better equipped dwellings (

Table 2; this will presumably have an impact on the housing stock characteristics; yet, the calculations require new Census data. (4) The PR zones consequently have a greater supply of small flats that are appealing to young first-time homebuyers but can also be easily rented out, thus being seen as “concrete gold” [

48]. In 2011, almost 21% of the city’s housing stock was tenant-occupied versus 8% in 2002 (2002 and 2011 Census data), which unveils the popularity of the “buy-to-let” model, recently additionally encouraged by Airbnb rentals. (5) In comparison to large housing estates, these neighborhoods are far better equipped with daily shops, services, and third places, while also providing the ease of access to kindergartens and schools. (6) Finally, the price of flats in Grbavica and other PR zones has almost constantly risen over the years, which is why homebuyers see them as good investment destinations.

The market position of Grbavica and the geography of differences in the residential real estate prices expose the location preferences of homebuyers as well as the residential mobility patterns but also reveal that in the post-socialist Novi Sad, the priority is to reside as close to the downtown as possible, regardless of the neighborhood’s shortcomings. It might be thus said that, on a wider scale, the permanent reconstruction has succeeded in inversing the pattern of socio-spatial stratification inherited from socialism—now, the farther away the neighborhood is from the city center, the cheaper and less affluent it gets.

6. Discussion

When evaluated solely on the macro-level, it may be concluded that the regime of permanent reconstruction was highly successful, especially given its initial objectives set by the 1985 master plan. It boosted the housing construction, quickly resolved the housing crisis, reduced the urban sprawl, and significantly decreased the volume of illegal construction. By recycling the land of attractively located, yet sparsely built city neighborhoods, it drastically increased their residential and building density and closed the rent gap, achieving more efficient land uses, making the urban fabric more compact, and redistributing the local population. Furthermore, it supplied the local residential market with dwellings of various types, substantially relaxing it, while the resulting myriad of housing options increased the residential mobility. Permanent reconstruction also rejuvenated and diversified the housing stock, improved its overall technical quality, and leveled up the dwelling conditions in the city. Finally, one should not omit mentioning the additional economic benefits and the boost that the regime provided to the local economy. It recovered the housing construction industry, generated employment opportunities and new jobs, and increased the local economic activity, while also providing large tax revenues further invested in various infrastructural upgrading projects. Taking all this into account, one might argue that permanent reconstruction provided Novi Sad with a though-out and well-designed regeneration strategy that would effectively re-allocate the underutilized urban land, gradually change the urban morphology, and aid the city in achieving sustainable development.

However, as the case study disclosed, the micro-level outcomes make it a double-edged sword. The regime transformed Grbavica into an overbuilt and overcrowded neighborhood characterized by the lack of open public spaces and greenery, fenced inner-block courtyards mainly intended for parking, canyon-like streets, and parking availability issues but also by postmodern “unaesthetics,” which substantially influences the daily life of its residents as the end-users of regeneration. Simply put, by subordinating every square meter of available space to profit-making, investor urbanism showed little concern for the quality of the resulting dwelling environment, evolving into a pattern and shaping the physiognomy, physical and spatial structure, morphology, and architecture all PR zones in the same manner.

Although all the micro-level outcomes of permanent reconstruction were clearly visible in 2016, when the opposition won the local elections and changed the entire administration, instead of assessing them to redefine the demolition-based regeneration strategy, the public sector opted for a complete capitulation to neoliberal market forces. Whereas recent large-scale residential projects may be interpreted as a sign that Novi Sad is developing into a contemporary second-tier CEE city with a mature residential market, their background point to an advanced version of investor urbanism. In contrast to the previous period, when the regulations were being changed incrementally, yet not essentially, with the aim of attracting small investors and thus accelerating the regeneration, the plans are nowadays being fundamentally altered to fit perfectly the needs of particular large developers despite sometimes strong opposition of the non-governmental experts and several civil initiatives. To illustrate with two examples—the plan for the downtown area was changed to authorize the construction of a luxurious mixed-use complex named Pupin’s Palace (43,000 m2 net area), increasing its footprint and volume, doubling its height, and allowing the demolition of a protected building. In order to clear the site for the development of King’s Park (600 flats), the local government abolished the cultural heritage status of 250-year-old reed houses and tore them down even though the previous plan instructed their conservation and creation of an ethno-park. This does not imply that the former approach is justifiable but that it fully absorbed wild neoliberalism, giving certain investors almost unlimited power in decision making and mutating into a new planning practice that may leave much deeper scars in the urban tissue. With these recent “advancements” in the approach, it appears that real estate developers would soon be given a carte blanche to “permanently reconstruct” any urban space, regardless of what was planned for it, what needs to be purged, what the public interest is, what the needs of local community are, or how the new construction will affect the host neighborhood or the city as long as the project involves large-scale private investments.

Same as Belgrade, Novi Sad is not shrinking; on the contrary, its population is continuously increasing (e.g., by more than 40% during the post-socialist period,

Table 1), which generates a constant housing demand. The city still suffers from land scarcity yet still features large pockets of underutilized, misallocated, and decaying urban space within certain low-density neighborhoods that have been moderately affected by permanent reconstruction. The local authorities will continue capitalizing on it, catalyzing its revalorization, and closing the rent gaps, meaning that the regime of permanent reconstruction will most likely be incorporated into the new master plan. Yet, in order to omit the double-edged sword effect, some crucial changes need to be made in the planning domain, whereas the role and duties of the public sector should be redefined. Adding to the findings of the researchers who explored the common planning issues in Serbian cities [

41,

44,

47], general requirements in these terms may be summarized as follows: (1) abandoning the practice of catering to developers’ needs, ignoring the public interest, and blindly accepting the neoliberal philosophy; (2) implementing public policies and unambiguously defining the public interest; (3) avoiding rigid, top-down approaches; (4) unfettering the planning profession and making it as independent from politics as possible; (5) ensuring that the planning process is democratic, adaptive, participative, inclusive, and pro-active as well as evaluation- and feedback-based; (6) fostering transparent decision-making procedures; (7) enabling synergy between the stakeholders, i.e., local governments, private developers, and local community, and collaborative decision making; and last but not least, (8) developing new forms of urban governance to facilitate active and meaningful public engagement.

However, it would be naïve to suggest that effective and not just cosmetic implementation of any of these recommendations is possible without creating a persistent public pressure to put an end to investor urbanism. Hence, the starting point is mobilizing the public to participate in the planning process. Although a two-level participation has been prescribed by the law [

133,

134], it is often simulated through public presentations of adoption-ready plans, representing a mere formality. When a remark is made, it either gets rejected straightaway or later stumbles upon a perpetual transfer of responsibility from one institution to another, indicating that the local authorities do not perceive the public as a partner but rather an obstacle to their agenda. All this disempowers and discourages those willing to contribute, leaving them with the impression that there is no benefit from or point in participating. Yet, the main cause of an extremely low level of participation in all Serbian cities derives from the fact that citizens consider themselves as “extras” in urban development. They are generally ignorant of their civil rights, particularly in relation to the planning procedure, and this is precisely what the public sector has been and still is taking advantage of to maintain the status quo. The additional cause relates to the “not in my backyard” syndrome, meaning that the residents are sometimes ready to stand up for their neighborhood but not for any other, thus being unable to generate a critical mass of public dissatisfaction. Therefore, in order to pressure the public sector to enable a meaningful public involvement in the planning and decision-making process, the civil initiatives need to be directed towards teaching the citizens how to exercise their civil rights and encouraging them to come together, take action, and jointly defend the public interest. They need to be aware of pervasive and long-term impacts that investor urbanism will have on the urban development, especially in terms of undermining its sustainability prospects, and take responsibility for shaping the urban future. Once the citizens begin considering themselves as the key actors, the local authorities will treat them accordingly. This is the number one prerequisite for creating a sound and sustainable regeneration policy.

7. Concluding Remarks

Urban regeneration presented one of the principle processes of post-socialist urbanism [

33], and this paper discussed its origins, planning and institutional framework, dynamics, and outcomes in the case of Novi Sad. The demolition-based regeneration strategy named permanent reconstruction, which implied the replacement of low-density housing with medium- to high-rise apartment buildings, has evolved into the main driver of urban change, substantially altering the city’s socio-spatial structure, morphology, and landscape.

If simplified, leaving the contextual factors, as well as the scope and the scale of permanent reconstruction aside, the transformation of Grbavica neighborhood bears resemblance to demolition-based urban regeneration projects in other CEE cities. They were essentially market- and property-led, favored private interests, relied on the top-down approach, and depicted the entrepreneurial governance practices. The mechanisms of transformation may also be remotely associated with the lot-based urbanism that refers to lot-based piecemeal and inadequately controlled changes in the urban fabric, conducted without taking into account their impacts on the surroundings [

135]. However, as the case study revealed, what makes permanent reconstruction distinctive is a set of its inextricably linked determining factors that derive from the differed and distorted post-socialist transition and expose both the modus operandi and the attitude of public sector in Serbian cities not just towards urban regeneration, but also towards (sustainable) urban development. Adding to the findings of Backović for Belgrade [

41], they are as follows: (1) entrepreneurial, but laissez-faire urban governance; (2) partnership between politicians and developers; (3) unvisionary, non-strategic, and ad-hoc planning; (4) adoption of investor-tailored regulations; (5) permissive and lenient actions of relevant public institution; (6) lack of control over the regeneration process and urban development in general; (7) utterly non-transparent planning and decision-making processes; and finally, (8) disregard for the public opinion. Although some of these factors have certainly influenced and profiled both preservation- and demolition-based urban regeneration projects in other CEE countries, particularly non-EU Balkan ones, the extent of their interference is lower than in Serbia. Here, it important to mention that insufficient public engagement has been recognized as one of their major common denominators [

67,

136]; yet, in the case of Serbian cities, it is practically non-existent. In addition, the distinctiveness of permanent reconstruction also relates to its outcomes (even when compared to the renewal of Belgrade), meaning that it has been almost exclusively focused on the macro-level benefits, showing little concern for the quality of the dwelling environment and daily life of the residents. The identified dichotomy between macro- and micro- level results disclosed the shortcomings of this strategy, questioning the sustainability aspects of such urban regeneration.

The case study presented in this paper pointed out the weakness of post-socialist urban planning and the effects of investor urbanism in Novi Sad, common to all Serbian cities, which hamper their sustainable development and substantially affect their regeneration projects. The shift to a systematic approach to permanent reconstruction as a demolition-based urban regeneration strategy first requires fundamental changes in the domain of public sector’s practice highlighted in the discussion. There are some more specific recommendations for the policy and decision makers drawn from this research to be considered in the conjunction with the general requirements, which may substantially contribute to the sustainability of urban regeneration projects and also be applied to other CEE cities, particularly since their projects are primarily market-led. In summary, they relate to the following: (1) developing context-sensitive, tailor-made regeneration strategies both place- and people-focused instead of using an off-the-shell or one-size-fits-all recipe, as in the example of Novi Sad, with the aim of creating a genuine relationship with a concrete urban space; (2) involving local community in all phases of a regeneration project; (3) making wise use of spatial resources; (4) redefining the role of market in assigning new land uses and enhancing the role of residents as the ultimate stakeholders; (5) grounding housing provision on the demand to avoid market oversaturation and collapse; (6) taking into account that certain demands, conditions, and circumstances might change and facilitating adaptiveness; (7) guiding private investments and coordinating, supervising, and controlling the regeneration process; and finally, (8) recovering the balance between social and economic objectives and constantly assessing it while also including the environmental impacts into the equation in order for the regeneration to be successful and sustainable from all aspects. As for Novi Sad, the development of new master plan opens an opportunity to reexamine and rethink the regeneration strategy for low-density neighborhoods, which has been utilized for more than two decades. The depth and complexity of scars left by permanent reconstruction in the urban environment will depend on whether it will take advantage of or miss this opportunity.