Abstract

The aim of this study is to investigate the relationship between corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure and financial performance with the consideration of the mediating role of financial statement comparability (FSC) for a sample of Vietnamese listed firms. We used content analysis of the information related to the GRI Standards on annual reports in order to construct CSR disclosure score. We used a dataset of 1125 firm-year observations, covering 225 firms listed on Vietnam’s stock market in the period 2014–2018. Applying OLS and GMM estimation methods, Sobel test, and using different proxies of the mediator variable to increase the robustness, we obtained two remarkable conclusions. First, CSR disclosure has a positive impact on the financial performance of listed companies in Vietnam. Second, there is a complementary mediation effect of financial statement comparability in the above relationship. Our results suggest that it is necessary to develop a legal framework for the practice and disclosure of CSR as well as to apply the international accounting standards in the Vietnamese stock market.

1. Introduction

Originating from developed countries, the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has more than 60 years of history. Recently, research on CSR has been increasingly abundant and is no longer contained to developed markets [1]. The concept of CSR began to pervade Vietnam more than two decades ago through the Sustainability Report of multinational corporations operating in Vietnam, such as Honda, Coca-Cola, or Unilever. Before 2016, only a few large domestic enterprises publicly disclosed their CSR-related activities in their reports. Previously in Vietnam, specific laws regulated the social responsibility of enterprises to relevant stakeholders, such as Labor Law, Contract Law, Environmental Reporting Recommendations, etc., but there is no legal document or unified legal framework. The disclosure of CSR information in the company’s financial statements is optional in this stage. In 2015, for the first time, reporting guidelines were issued in Circular 155/TT-BTC, requiring listed companies to disclose environmental and social information related to sustainable development. After Circular 155/TT-BTC took effect in 2016, the publication of the Corporate Social Responsibility Report is no longer uncommon in the business community in Vietnam.

CSR is in essence a type of corporate investment, and how CSR disclosure affects financial performance has become a topic of great interest. The literature suggests that the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance (CFP) is not simply a direct link but a much more complex one, e.g., the impact of CSR disclosure could be transferred via some mediating factors [2]. Accordingly, instead of trying to clarify whether CSR disclosure is positively or negatively associated with financial performance, it is proposed that intermediate variables be used in the analysis [2]. The mediator variables identified in previous studies are quite diverse, such as competitive advantage, reputation and customer satisfaction, productivity, access to capital, corporate image, stakeholder influence capacity, natural and social resources, and corporate visibility [2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

Our study proposed to use financial statement comparability (FSC) as a mediator variable to understand the mechanism through which CSR disclosure directly and indirectly affects financial performance. There are several reasons for our choice of this mediator variable. First, one of the most important goals of accounting standards, financial statement comparability, has been shown to significantly affect the quantity and quality of the information environment of enterprises. There have been numerous studies on the link between CSR and business performance, but only few studies have been conducted on the link between CSR and FSC. This factor is expected to exert its influence in many aspects of corporate activities, especially in emerging markets, where the local accounting standards have not been in line with the international standards that aim to enhance the comparability of financial statements. However, even though FSC should be more important in emerging markets due to issues of information asymmetry and lack of common accounting standards, little has been done to investigate the role of FSC here.

We aimed to fill this gap by investigating the relationship between CSR, FSC, and CFP in Vietnam, a developing economy. If FSC is found to be conducive to the positive effect of CSR on CFP, then obviously there should be more justifications to advocate the faster adoption of international accounting standards to improve the comparability of financial statements. This implication is meaningful since Vietnam is still struggling to find ways to adhere to the international set of accounting standards. The study would also extend the literature on the benefits of financial statement comparability: previous studies tend to focus on the direct effect of FSC on costs of debt, equity, performance, risk, etc., but the indirect effect of FSC has received little attention.

Furthermore, it is also interesting to note that there might be different requirements regarding the disclosure content between the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the instructions from regulatory bodies. In practice, Vietnamese businesses have many choices between different guidelines related to CSR practices, such as the GRI, ISO26000, SA8000, SMETA, BSCI, and AA1000, due to the lack of formal legal framework for the presentation of CSR activities. Among them, the GRI international standard has been adopted by many large enterprises, especially those participating in free trade agreements, such as EVFTA and CTPPP. In this study, we seek to analyze the impact of the disclosure according to GRI standards on firm performance. Therefore, the study contributes important practical significance in shaping the legal framework for CSR activities in Vietnam.

Second, despite solid theoretical support from foundational theories, including Stakeholder Theory, Legitimacy Theory, and Agency Theory that justifies the mediating effect of FSC on the link between CSR and CFP, so far, there have been no empirical attempts to investigate this mediating role of FSC. In this study, we devised a framework that combines the three theories to theoretically explain the mechanism through which FSC could mediate the linkage between CSR and CFP. Examining this link would help to identify a new mediating factor that would help to enrich the literature both theoretically and empirically.

After the introduction, the remainder is structured as follows: Section 2 presents a brief overview of the theoretical basis and empirical studies and proposes research hypotheses; Section 3 describes sample data, research models, and methods; Section 4 discusses the results of the study; and Section 5 concludes and presents policy implications.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. CSR Disclosure and Financial Performance

Agency theory is considered as the foundation theory bridging the relationships throughout this study. Agency theory holds that there is likely to be a conflict of interest between business principals and agent in the enterprise, which gives rise to agency costs [9]. This contradiction is the problem that all joint stock companies are prone to encounter, known as the principal–agent problem. Agency theory provides implications about the mechanisms to address the principal–agent problem and to reduce agency costs. For example, the Stakeholder theory argues that managers should pay attention to all stakeholders, not just the shareholders [10]. The Legitimacy Theory states that companies are expected to seek and remain legitimacy for their operations [11]. According to both theories, CSR disclosure could be considered as a resource or means for enterprises to maintain legitimacy and proper relationships with stakeholders.

From the above fundamental theories, it can be expected that CSR disclosure positively affects corporate financial performance and improves the image and value of a business [12,13]. Firms with higher CSR disclosure scores are more likely to enhance their reputation, thus being able to realize business opportunities and generate profits by differentiating products, attract highly qualified personnel, and uplift the ability to demand a premium for their products [14]. CSR disclosure increases corporate value by balancing the competitive interests of all stakeholders [15]. For this reason, CSR disclosure can improve financial performance [16]. CSR disclosure can be seen as an investment in capabilities that allow a company to differentiate itself from competitors, in terms of stakeholder management and strategic initiatives, thereby improving the corporate performance [17]. CSR disclosure is an important element in building stakeholder relationships and leading to stronger financial performance [18].

On the other hand, within the framework of Agency Theory, there is a negative effect of CSR disclosure on financial performance [19,20]. The existence of this negative relationship is explained under the trade-off theory, which opines that CSR disclosure leads to a decrease in financial performance [21,22]. There are significant, long-term, negative consequences of CSR activities that result in lower profitability [23]. Some authors support this argument and argue that CSR disclosure causes companies to incur additional costs in excess of potential revenue [24], which reduces shareholder returns and wealth [25,26]. Essentially, expenditures related to CSR can be completely seen as costs and thus reduce financial performance.

What complicates the matter is that the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance is not just positive or negative, but it is more complex. In some cases, no (long-term and short-term) relationships between CSR disclosure and financial performance are documented [27]. Furthermore, other studies consider it to impose inconclusive impact, while others emphasize that there appears not merely a direct link, i.e., there could be channels that conduct the impact of CSR disclosure to firm performance [2].

Even though some studies point to negative effects of CSR disclosure, in agreement with the mainstream findings on the positive impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance, we propose research hypothesis H1 as follows:

Hypothesis (H1).

CSR disclosure is positively correlated with financial performance.

2.2. CSR Disclosure and Financial Statement Comparability

To solve the agency problem stated in the Agency theory [9], Stakeholder Theory [10], and Legitimacy Theory [11], managers may use CSR disclosure to build and maintain their reputation or give signal about the image of the company [10,11]. Therefore, companies that disclose socially responsible information also tend to be law-abiding, honest, and trustworthy [28]. Furthermore, earnings management behavior is less common in companies with high CSR disclosure ratings, and managers are strongly motivated by ethical considerations to improve transparency and produce good-quality financial statements [28,29]. The positive relationship between CSR disclosure and the accuracy of earnings management forecasts supports the view that managers try to enhance the quality of their financial disclosure due to ethical reasons [30]. Socially responsible companies are less prone to adjust and re-disclose their financial statements [31]. A direct link between CSR disclosure and the comparability of financial statements is established: firms publishing CSR reports are motivated to establish and maintain a good reputation and limit actions that damage the reputation [32]. Therefore, these enterprises are willing to comply with accounting standards, aiming to improve comparability in accounting. In line with these arguments [32], we establish the testable hypothesis H2 as follows:

Hypothesis (H2).

CSR disclosure is positively correlated with financial statement comparability.

2.3. Financial Statement Comparability and Financial Performance

Agency Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and Legitimacy Theory are three foundations that support the link between financial statement comparability and financial performance. Because comparability in accounting is the aim of accounting standards, it is conducive to building legitimacy and maintaining decent relationships with stakeholders. Enterprises are willing to provide accounting comparability through financial statements that are supposed to be transparent about financial information. Because financial statement comparability reduces the cost of information gathering and processing, it increases the overall quantity and quality of information available to information users [33]. In addition, financial statement comparability enhances corporate financial performance by aiding managerial decisions regarding resource allocation [34], improving stock price information [35] and reducing managers’ opportunistic behavior [36,37]. In particular, financial statement comparability provides significant benefits to a firm’s financial performance in both formal and informal capital markets. Comparability in accounting reduces the cost of information processing and undermines uncertainty about a firm’s potential credit risk in both public capital markets [38] and private loans [39]. It helps lower the cost of debt [40] and the cost of equity [41] and assists businesses in accessing trade credit [42]. Thus, comparability capability of financial statements also has an impact on the value created for the stockholders and owners’ equity return [43]. The significant benefits of financial statement comparability suggest a positive association with financial performance, which is stated in our hypothesis H3 as follows:

Hypothesis (H3).

Financial statement comparability is positively related to Financial Performance.

2.4. Mediating Role of Financial Statement Comparability

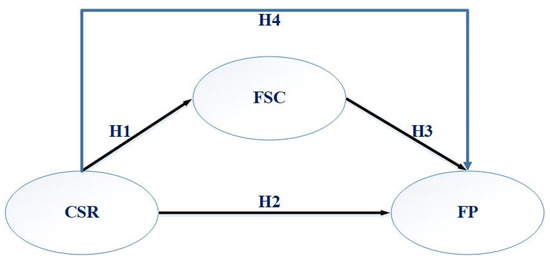

Considering the ambiguity about the correlation between CSR disclosure and financial performance, it seems imperative to adopt a more complex approach to elucidate the transmission mechanism. As mentioned earlier, if CSR disclosure promotes comparability in accounting, accounting comparability in turn has a positive effect on financial performance, that is, CSR disclosure has an indirect effect (via FSC) on financial performance. The existence of this indirect effect would indicate the partial mediation effect of financial statement comparability. Specifically, we built the hypothesis H1, that CSR disclosure leads to an increase in financial performance. This view is based on the idea that CSR disclosure is beneficial for companies in sending positive signals to the market and stakeholders, improving the reputation and value of businesses [12,13]. Notably, such positive information may have a certain impact on financial statement comparability (as in our hypothesis H2). Meanwhile, according to hypothesis H3, the significant benefits of financial statement comparability should allow firms easy access to capital markets at low cost, resulting in a positive correlation between financial statement comparability and financial performance. In addition, a large amount evidence also supports the view that positive signals through CSR disclosure cannot only directly affect financial performance but also indirectly through other mediators, such as competitive advantage, reputation and customer satisfaction [2,4], access to capital [3], productivity [5], visibility [6], natural and social resources [7], or stakeholder influence capacity [8]. Therefore, in agreement with these studies, we hypothesize H4 as follows:

Hypothesis (H4).

A part of the effect of CSR disclosure on financial performance is mediated byfinancial statement comparability.

In Figure 1, we propose the following analytical framework (with hypotheses attached) for the investigation based on the underlying theories and past research:

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Collection

The research sample with 1125 firm-year observations consists of non-financial enterprises listed on Vietnam’s stock market in the period 2014–2018. We centered on these criteria to select firms: (1) Firms belonging to the group of non-financial industries because financial enterprises have different characteristics of business operations and financial statements. Accordingly, we removed companies in the financial sector (100 companies from the total of 730 companies registered on the Vietnamese stock exchange). (2) Not all the listed firms published financial statements, annual reports, sustainability reports, or corporate social responsibility reports in the period examined. Therefore, we had to limit our sample to those that did. (3) The enterprises should be representative of the market. From each industry, we selected the leading enterprises based on the size of total assets so that the selected enterprises could account for at least 90% of the industry in terms of asset scale. As a result, a sample of 225 non-financial listed businesses was deemed sufficient to reflect the Vietnamese market.

The research period is 2014–2018, corresponding to the period before and after the Circular 155/2015/TT-BTC was issued. The study chose this period to cover the period when applying both mandatory and voluntary disclosures. Before 2014, very few firms chose to disclose CSR activities. CSR-related data were manually retrieved from sustainability reports and/or annual reports. The financial data of the same firm were provided from Refinitiv Eikon.

3.2. Research Model

To analyze the impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance (hypothesis H1), based on previous studies [2,12], we propose the following model:

To examine the association between CSR disclosure and financial statement comparability (hypothesis H2), the following regression model was built based on the previous research [32]:

Then, to test hypothesis H3 about the link between financial statement comparability and financial performance, we constructed the following regression model based on previous study [43]:

In the examination of mediation role of FSC (hypothesis H4), we formed model (4). In model (4), we put both CSR and FSC in the same model with financial performance as the dependent variable. The model (4) is part of the system of equations (that also contains the previous 3 models) used to test the mediating role of a particular factor [44,45,46,47]:

where:

FPit = α + βCSRit + γFSCit + θXit + INDUSTRYi + εit

- FP is the dependent variable representing the financial performance of the enterprise, measured by the ratio between earnings before tax and total assets (ROA);

- CSR represents CSR disclosure, measured by an index reflecting the level of social responsibility information disclosure. We used the content analysis method and the GRI Standards (2016) to build the CSR variable;

- FSC_1 and FSC_2 are measures of financial statement comparability, in accordance with previous research [33];

- X is a vector including control variables in consistence with previous studies to control for possible effects of firm characteristics on financial performance [2,12,32]. Specifically, LEV, SIZE, TANG, FOR, GROW, and AGE are variables that represent financial leverage, firm size, tangible assets, foreign ownership, revenue growth, and listing age, respectively. LEV is calculated as the ratio of total liabilities to total assets; SIZE is the logarithm of total assets; TANG is measured as the ratio between tangible fixed assets and total assets; FOR represents for foreign ownership; GROW represents growth opportunities through revenue growth; and AGE is the logarithm of the company’s number of years since being listed;

- INDUSTRY is a vector consisting of dummy variables to account for industry effects on financial performance. These are eight non-financial industry dummy variables covering Basic Materials, Consumer Cyclicals, Consumer Non-Cyclicals, Energy, Healthcare, Industrials, Technology, and Utilities (Thomson Eikon Reuters Industry Classification Scheme). Each industry dummy variable is a binary variable, taking the value of 1 if the firm belongs to one of the above industry groups; otherwise, its value is 0.

See Appendix A.

3.3. Methodology

The study uses the Ordinary Least-Squares method (OLS) to estimate the regression results. Furthermore, we use the System Generalized Method of Moments (GMM) estimator to deal with potential endogenous problems as well as to overcome the autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity issues that are common with panel data [48]. In addition, to ensure the robustness of the results on the mediating role, we added the Sobel test [49], which further provides information on the relative sizes of the direct and indirect effects. Finally, to enhance the robustness, we used two different proxies of the mediator variable.

4. Research Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

From Table 1, the average value of the variable FP is 0.099, which means that the average earnings before tax is about 10 percent. Both variables FSC_1 and FSC_2 have negative mean values and are approximately the same, indicating the relatively low accounting comparability of the listed firms in the sample. CSR has a mean value of 0.255 with a standard deviation of 0.145, suggesting that the level of CSR disclosure in Vietnam is still low compared to the criteria outlined in GRI Standards. The average value of the LEV is 0.246, which means that total debt accounts for almost a quarter of total assets. TANG receives an average value of 0.301, indicating that tangible fixed assets account for nearly a third of corporate assets. FOR represents foreign ownership, having an average of 7.004, meaning that foreign shareholders account for an average ownership ratio of 7%. GROW has an average value of 0.223, implying a relatively strong revenue growth of the firms in the sample. AGE has an average value of 2.760, which translates to an average listing age of approximately 15 years.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of variables.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

The correlation matrix in Table 2 shows that, at the 5% significance level, the variables FSC_1, FSC_2, CSR, and AGE are positively correlated, while SIZE, LEV, and TANG variables are negatively correlated with FP. The pairwise correlation coefficient between two variables FSC_1 and FSC_2 is 0.935 and is statistically significant at the 5% level, showing that these two proxies of financial statement comparability are strongly correlated. The positive and statistically significant correlation coefficients of two pairs of variables (FSC_1 with CSR, FSC_2 with CSR) suggest that there is a positive relationship between CSR disclosure and financial statement comparability. This implies that there may be a mediating role of financial statement comparability as in hypothesis H4. In addition, Table 2 implies that there should be no serious multicollinearity in the model because none of the pairwise correlation coefficients (except FSC_1 with FSC_2, which are not used in the same model) have absolute values greater than 0.9.

Table 2.

The correlation matrix.

4.3. Main Results

The central theme of this study was to answer the question of whether CSR disclosure affects financial performance and whether financial statement comparability acts as a mediator in this relationship. The correlation analysis was not able to determine the impact of the factors that can interact with other variables. Therefore, we conducted regression analysis to examine the hypotheses in a more reliable manner. Table 3 presents the regression results, and columns 1–4 indicate the estimation results of models (1), (2), (3), and (4) using the OLS method, respectively.

Table 3.

Regression results.

Hypothesis H1 proposes that CSR disclosure has a positive effect on financial performance. Based on the estimation result of model (1), we confirm this positive relationship (Table 3, column 1). Specifically, the coefficient of the CSR variable is positive and statistically significant (0.092, p < 0.01), implying that the higher the level of CSR disclosure, the more financially efficient the business is. This result corroborates the findings of earlier studies [12,13]. Therefore, research hypothesis H1 is confirmed.

Consistent with hypothesis H2, Table 3 (column 2) shows a positive correlation between CSR disclosure and financial statement comparability. The coefficient of the CSR variable is positive and statistically significant (0.006, p < 0.01), suggesting that the improvement in the CSR disclosure level increases accounting comparability in their accounting. This result is similar to the previous study [32]. Therefore, our hypothesis H2 is supported.

With regard to the model analyzing the relationship between financial statement comparability and financial performance (Table 3, column 3), the coefficient of the variable FSC_1 is positive and statistically significant (2.057, p < 0.01), confirming the positive relationship between financial statement comparability and financial performance, consistent with the findings of previous studies [43]. This link could be explained by Stakeholder Theory and Legitimacy Theory: financial statement comparability brings many significant benefits to the financial performance of the business. This also validates our hypothesis H3.

To test the mediating role of financial statement comparability under hypothesis H4, we used the three-step method: first, determine the correlation between the dependent variable and the independent variable; second, determine the correlation between the mediator variable and the independent variable; and the third step is to determine the correlation between the dependent variable, the independent variable, and the mediator variable. The results in Table 3 (columns 1, 2, and 4) show that the coefficients are all positive and statistically significant (0.092, p < 0.01; 0.006, p < 0.01; 0.112, p < 0.01; 1.749, p < 0.01), i.e., both CSR and FSC_1 have a positive effect on FP, and when FSC_1 is controlled, the effect of CSR on FP changes (from 0.092 to 0.112). Therefore, there is an indirect relationship between CSR and FP, and FSC_1 serves as the mediator variable. In addition, the direct and indirect effects of CSR on FP are both positive and statistically significant, suggesting that the variable FSC_1 plays a complementary role. Therefore, hypothesis H4 is confirmed, indicating that part of the effect of CSR disclosure on financial performance is mediated by financial statement comparability.

4.4. Robustness Tests

4.4.1. Alternative Measures of Mediator Variable

We used another proxy of financial statement comparability according to the previous study [33] to increase the robustness of the results on the mediating role of financial statement comparability. Specifically, the proxy FSC_2 is used to replace the proxy FSC_1 in the regression models (2), (3), and (4). The results of this regression are presented in Table 4; columns 1–4 indicate models (1), (2), (3), and (4), respectively.

Table 4.

Regression results when using an alternative measure of mediator variable.

Table 4 shows that even when replacing the financial statement comparability variable with another proxy, CSR disclosure still has a positive (direct and indirect) impact on financial performance. Specifically, in Table 4, the coefficient of CSR variable (Column 2) is positive and statistically significant (0.021, p < 0.01), implying a positive correlation and supporting hypothesis H2. The coefficient of the variable FSC_2 is also positive and statistically significant (1.337, p < 0.01) in Table 4, column 3. This also confirms the positive association and supports the research hypothesis H3. At the same time, the data in Table 4, columns 1, 2, and 4 shows that the coefficients are all positive and statistically significant (0.092, p < 0.01; 0.021, p < 0.01; 0.100, p < 0.01; 1.143, p < 0.01), i.e., both CSR and FSC_2 have a positive effect on FP, and when FSC_2 is controlled, the effect of CSR on FP changes (coefficient from 0.092 to 0.100). This result supports the hypothesis H4, which confirms that CSR disclosure has a positive effect on financial performance with a complementary mediation of financial statement comparability. Thus, the robustness of the findings is attained because the results remained unchanged when we substituted FSC_1 with another proxy of the mediator variable (FSC_2).

4.4.2. Sobel Test

Table 5 presents the Sobel test on the mediating effect. It can be seen that the mediator variable is statistically significant with both FSC_1 and FSC_2 proxies. This confirms that financial statement comparability is a mediator variable in the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance [49].

Table 5.

Sobel test.

We further calculated the size of the direct and indirect influence of CSR disclosure on financial performance, following the previous study [47]. Accordingly, the influence of CSR on FP mediated through FSC_1 and FSC_2 is 9% and 19% of the total effect, respectively; the indirect influence through the mediator variable is 0.1 to 0.2 times larger than the direct effect. At the same time, Table 6 also confirms that CSR disclosure has a positive effect on financial performance with a complementary mediation of financial statement comparability (Table 6).

Table 6.

The indirect effect of mediator variable.

4.4.3. Robustness to Endogeneity Issue

We further controlled for the issue of endogeneity using System GMM. The lagged variables of dependent variables are all positive and statistically significant (0.414, p < 0.01; 0.358, p < 0.01; 0.461, p < 0.01; 0.376, p < 0.01; 0.434, p < 0.01; 0.609, p< 0.01; 0.656, p < 0.01). The Hansen test and AR(2) test are satisfactory because the p-value is greater than 10% in both tests [48]. In addition, the control variables included in the model all showed an effect on financial performance, consistent with previous studies [2,12,32].

The results in Table 7 confirm the positive impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance and the mediating role of financial statement comparability. Financial statement comparability’s mediating role also highlights the need for the faster adoption of international financial reporting standards for listed companies in Vietnam. Research findings point to the need to encourage CSR practice and disclosure since this is expected to facilitate firm performance. The above directions help to achieve the benefits of all stakeholders, including regulators, investors, and listed companies.

Table 7.

Regression results according to GMM.

There have been a considerable number of studies on the link between CSR disclosure and firm performance (CFP), but there are only a few that examine both direct and indirect effects (through mediator variables). We are the first to investigate the mediating effect of financial statement comparability on the link between CSR and CFP. The findings also add to the literature on the favorable effect of financial statement comparability.

5. Conclusions

Numerous previous studies have focused on clarifying the direct link between CSR disclosure and financial performance. Recently, scholars tend to believe in a more complex nature of the above association, suggesting the examination of both direct and indirect effects of CSR disclosure and the clarification of the role of mediator variables. In response to this call, we conducted this study using a sample of 225 enterprises listed on the Vietnamese stock market in the period 2014–2018. The objective of the study was to analyze the impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance and to examine whether financial statement comparability acts as a mediator variable in the above link.

The study documents two notable findings. Firstly, the results confirm the positive impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance of listed companies in Vietnam. This positive association is consistent with the explanation from Agency Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and Legitimacy Theory that CSR disclosure helps construct a trustworthy image with the stakeholders of the business, enhance reputation, and bring customers to the business. At this point, the presentation and disclosure of corporate social responsibility information is seen as a resource that generates higher revenue and/or reduces costs. The issue of increasing revenue or reducing costs has a positive effect on the financial performance of the business. Second, our study confirms for the first time that there is a complementary mediation effect of financial statement comparability in the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance. Research results are still robust when using an additional proxy of mediator variable and additional estimation method (System GMM to control for the potential endogeneity problem). We also provided Sobel calculation, which quantifies the ratio of indirect effect to direct effect. Our results suggest that it is advisable to develop a legal framework for the practice and disclosure of CSR as well as applying the international accounting standards to facilitate better accounting comparability because this would create synergy that improves significantly corporate performances.

Notably, this is the first empirical study to confirm the mediating role of the financial statement comparability in the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance. We contribute theoretically by using the Agency Theory, Stakeholder Theory, and Legitimacy Theory in an intertwined framework to explain the linkages throughout the research model.

The research also offers several important and practical implications for Vietnam. The purpose of these findings is to assist investors in carefully considering and analyzing the status of each firm based on annual reports and levels of financial statement comparability. An investment that is appropriate and reasonable should assemble crucial financial and non-financial data to obtain a complete picture of the organization. Furthermore, regulatory bodies should consider and implement a more stringent monitoring framework for information disclosure obligations, including CSR disclosure.

Besides the obtained results, the study also has some limitations. First, the study is conducted with a sample of non-financial listed companies from a developing country. As the institutional environment varies from country to country, results may not be generalizable to other developing countries. Second, the impact of CSR disclosure on financial performance can be influenced by other variables. However, this was not mentioned in the study. Future studies could extend by analyzing the regulatory influence of state ownership or firm growth on the relationship between CSR disclosure and financial performance, for example.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, and writing and editing the original draft, C.T.M.T., N.V.K., N.T.C. and N.T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by Vietnam National University- Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCM) under grant number NCM2019-34-01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from secondary data via Eikon Refinitive.

Data Availability Statement

The data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Definition of research variables.

Table A1.

Definition of research variables.

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| FP | The ratio between earnings before tax and total assets; |

| CSR | The index showing the level of social responsibility information disclosure is built according to the content analysis method; |

| FSC_1 FSC_2 | The average accounting comparability for each combination form of the four firms with the highest comparability to firm;The median accounting comparability for each combination form for all firms in the same industry as firm; |

| SIZE | The logarithm of total assets; |

| LEV | The ratio of total liabilities to total assets; |

| TANG | The ratio between tangible fixed assets and total assets; |

| FOR | The proportion of foreign holding in firm at the beginning of the year; |

| GROW | The revenue growth rate; |

| AGE | The logarithm of the company’s listing age; |

| INDUSTRY | A vector of binary variables, taking the value of 1 if the enterprise belongs to one of the eight industry groups, covering Basic Materials, Consumer Cyclicals, Consumer Non-Cyclicals, Energy, Healthcare, Industrials, Technology, and Utilities; otherwise, its value is 0. |

References

- Baxi, V.C.; Ray, R.S. Corporate Social Responsibility; Vikas Publishing House: India, Noida, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Saeidi, S.P.; Sofian, S.; Saeidi, P.; Saeidi, S.P.; Saaeidi, S.A. How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- Agyemang, O.S.; Ansong, A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance of Ghanaian SMEs: Mediating role of access to capital and firm reputation. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.Y.; Danish, R.Q.; Asrar-ul-Haq, M. How corporate social responsibility boosts firm financial performance: The mediating role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 166–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, I.; Kobeissi, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, H. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial performance: The mediating role of productivity. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 671–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. Corporate social responsibility, visibility, reputation and financial performance: empirical analysis on the moderating and mediating variables from Korea. Soc. Responsib. J. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, P. The mediating role of natural and social resources in the corporate social responsibility—Corporate financial performance relationship. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2021, 42, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaye, Y.I.; Ishak, Z.; Che-Adam, N. The mediating effect of stakeholder influence capacity on the relationship between corporate social responsibility and corporate financial performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 164, 528–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.C.; Meckling, W.H. Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. J. Financ. Econ. 1976, 3, 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Strategic Management A Stakeholder Approach. J. Hum. Resour. Sustain. Stud. 1984, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran, P.L.; Wood, R.A. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1984, 27, 42–56. [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens, B. A note on the interaction between corporate social responsibility and financial performance. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 68, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, S.; Zameer, M.N. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability: Evidence from Indian commercial banks. Pac. Bus. Rev. Int. 2017, 9, 39–47. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate social and financial performance: A meta-analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyeadi, J.D.; Ibrahim, M.; Sare, Y.A. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance nexus: Empirical evidence from South African listed firms. J. Glob. Responsib. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torugsa, N.A.; O’Donohue, W.; Hecker, R. Capabilities, proactive CSR and financial performance in SMEs: Empirical evidence from an Australian manufacturing industry sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 109, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusoff, W.F.W.; Adamu, M.S. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from Malaysia. Int. Bus. Manag. 2016, 10, 345–351. [Google Scholar]

- Elouidani, A.; Faical, Z. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance. In African Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance; Inderscience Enterprises Ltd.: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Gatsi, J.G.; Anipa, C.A.A.; Gadzo, S.G.; Ameyibor, J. Corporate social responsibility, risk factor and financial performance of listed firms in Ghana. J. Appl. Financ. Bank. 2016, 6, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Brammer, S.; Brooks, C.; Pavelin, S. Corporate social performance and stock returns: UK evidence from disaggregate measures. Financ. Manag. 2006, 35, 97–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.P.; Ainscough, T.; Shank, T.; Manullang, D. Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investing: A global perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 70, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortez, M.C.; Silva, F.; Areal, N. The performance of European socially responsible funds. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Does it pay to be different? An analysis of the relationship between corporate social and financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 1325–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callan, S.J.; Thomas, J.M. Corporate financial performance and corporate social performance: an update and reinvestigation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 61–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.G.; Kohers, T. The link between corporate social and financial performance: Evidence from the banking industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2002, 35, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aupperle, K.E.; Carroll, A.B.; Hatfield, J.D. An empirical examination of the relationship between corporate social responsibility and profitability. Acad. Manag. J. 1985, 28, 446–463. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Li, H.; Li, S. Corporate social responsibility and stock price crash risk. J. Bank. Financ. 2014, 43, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Strategic communication of corporate social responsibility (CSR): Effects of stated motives and corporate reputation on stakeholder responses. Public Relat. Rev. 2014, 40, 838–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. Corporate social responsibility and management forecast accuracy. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 353–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wans, N. Corporate social responsibility and market-based consequences of adverse corporate events: Evidence from restatement announcements. J. Account. Audit. Financ. 2020, 35, 231–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, L. Corporate social responsibility and financial statement comparability: Evidence from China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Franco, G.; Kothari, S.P.; Verdi, R.S. The benefits of financial statement comparability. J. Account. Res. 2011, 49, 895–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.W.; Collins, D.W.; Kravet, T.D.; Mergenthaler, R.D. Financial statement comparability and the efficiency of acquisition decisions. Contemp. Account. Res. 2018, 35, 164–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Choi, S.; Myers, L.A.; Ziebart, D. Financial statement comparability and the informativeness of stock prices about future earnings. Contemp. Account. Res. 2019, 36, 389–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, B.C. The effect of accounting comparability on the accrual-based and real earnings management. J. Account. Public Policy 2016, 35, 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh Liem, N. Accounting comparability and accruals-based earnings management: Evidence on listed firms in an emerging market. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1923356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kraft, P.; Ryan, S.G. Financial statement comparability and credit risk. Rev. Account. Stud. 2013, 18, 783–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, Y.; Xin, B.; Zhang, W. Financial statement comparability and debt contracting: Evidence from the syndicated loan market. Account. Horiz. 2016, 30, 277–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Yang, Z.; Dutta, A. Accounting information comparability and debt capital cost empirical evidence from Chinese listed companies. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2018, 8, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-B.; Shi, H.; Zhou, J. International Financial Reporting Standards, institutional infrastructures, and implied cost of equity capital around the world. Rev. Quant. Financ. Account. 2014, 42, 469–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ng, J.; Saffar, W. Financial reporting and trade credit: Evidence from mandatory IFRS adoption. Contemp. Account. Res. 2021, 38, 96–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourabdollah-e-Sofehsan, Z.; Badavar-e-Nahandi, Y.; Baradaran-e-Hassanzadeh, R. Studying the effect of comparability capability of financial statements on the value created for the stockholders and owners’ equity return. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2013, 7 (Suppl. 1), 2718–2727. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, D.Y.; Qi, G.Y.; Wang, J. Corporate social responsibility, internal controls, and stock price crash risk: The Chinese stock market. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Su, K.; Zhang, M. Water disclosure and financial reporting quality for social changes: Empirical evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 166, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G., Jr.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roodman, D. How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J. 2009, 9, 86–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmetoglu, M. Medsem: A Stata package for statistical mediation analysis. Int. J. Comput. Econ. Econom. 2018, 8, 63–78. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).