Abstract

Most of Europe’s rivers are highly fragmented by barriers. This study examines legal protection schemes, that specifically aim at preserving the free-flowing character of rivers. Based on national legislation, such schemes are found in seven European countries: Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, France and Spain as well as Norway and Iceland. The study provides an overview of the individual schemes and their respective scope, compares their protection mechanisms and assesses their effectiveness. As Europe’s the remaining free-flowing rivers are threatened by hydropower and other development, the need for effective legal protection, comparable to the designation of Wild and Scenic Rivers in the United States, is urgent. Similarly, any ambitious strategy for the restoration of free-flowing rivers should be complemented with a mechanism for their permanent protection once dams and other barriers are removed. The investigated legal protection schemes constitute a starting point for envisioning a more cohesive European network of strictly protected free-flowing rivers.

1. Introduction

Europe’s last wild rivers and dynamic river landscapes deserve better protection. This study examines existing legal protection mechanisms for free-flowing rivers in Europe in order to draw conclusions for more cohesive European policies for river protection. Over the last fifty years, seven countries have put individual river protection schemes in place through national legislation: Slovenia, Finland, Sweden, France and Spain, as well as in Norway and Iceland.

The last remaining free-flowing rivers are under pressure from various sides, in particular hydropower development. After a relatively calm period, the global boom of hydropower and dam projects is also taking hold in Europe: 8500 new hydropower plants are planned across Europe [1]. It is fair to speak of a “gold rush,” affecting both EU member states and accession countries. This push for hydropower development threatens the last wild rivers from the Balkans to Portugal, Austria, Romania and other countries. Already, Europe’s rivers are fragmented by more than a million barriers that entail widespread ecological consequences [2]. The most fundamental among these effects is the disruption of the free flow of water and sediment, resulting in changes in morphodynamics and loss of connectivity, as well as creating physical barriers to the migration of fish and other organisms. The environmental effects of barriers in watercourses are one of the main reasons why the environmental objectives of the Water Framework Directive (WFD) were largely not met by 2018, with only 40% of the EU’s surface waterbodies reaching “good ecological status” or “good ecological potential” [3].

River fragmentation and flow regulation for hydropower are major drivers of the freshwater biodiversity crisis. Of the countries examined in this study, according to the River Fragmentation Index, most river basins in northern Finland, northern Sweden, most of Norway and Spain as well as the alpine region of France fall into the category “severe,” while river fragmentation in Slovenia is classified “moderate” or “heavy” and in Iceland “moderate” [4]. The impacts of storage on flow regimes are, according to the River Regulation Index classified “high” in some basins of northern Finland, most of northern Sweden, most of Norway and some of Slovenia; regulation impacts in most Spanish basins fall into the categories “high” or “severe”, while Iceland falls into the category “weak” [4].

According to the European Red List of Threatened Species, 37% of European freshwater fish species are considered threatened [5], as well as 44% of freshwater mollusks, making them by far the most threatened group assessed to date in Europe [6]. WWF’s Living Planet Index 2020 clearly shows that Europe does not represent an exception from the global decline of freshwater biodiversity, estimating the average decline of migratory freshwater fish in Europe to be 93% since 1973 [7]. A report on threatened freshwater fish in the Mediterranean Basin highlights the dramatic impact of hydropower, providing alarming estimates for the increased extinction risk for endangered species, in particular by the proliferation of small hydropower projects [8]. In fact, some 2000 hydropower projects are proposed within the boundaries of National Parks, Biosphere Reserves and other protected areas in the Mediterranean Region alone. The report concludes: “There is an urgent need to mitigate the escalating ecological damage triggered by the hydropower binge through preservation and restoration of free-flowing rivers” [8].

Apart from hydropower, serious threats to free-flowing rivers are imposed by large-scale river engineering projects for inland waterways that entail canalization along with the construction of dams and sluices, for example on the Danube and Oder rivers [9]. Highly controversial, the E40 International Waterway project aims to establish a 2000 km inland waterway connection from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea [10]. If created, it would have potentially dramatic effects on the Prypjat and its vast and largely pristine floodplains in the Polesia region of Belarus, where Prypjat National Park was established in 1996.

The EU’s existing water and nature conservation legislation offers potentially effective mechanisms to protect free-flowing rivers. The Water Framework Directive (WFD), with its non-deterioration obligation, along with the requirement to reach good ecological status, could be implemented for this purpose. The WFD also establishes a nexus to the Nature Directives, linking environmental objectives for waterbodies in protected areas to the achievement of the conservation objectives for these areas. The EU’s Nature Directives also include an obligation to prevent deterioration of the designated sites within the Natura 2000 network. Besides the designation of rivers as protected areas, other provisions command river protection, e.g., protections of migratory fishes among the Species of Community Interest. However, implementation of these legal provisions in the EU member states has been insufficient and, in many cases, not able to prevent further degradation of free-flowing rivers, their natural properties and biodiversity. In part, this reflects a well-known shortcoming of the WFD, namely the fact that the hydromorphological quality elements of rivers and streams, such as hydrological regime and river continuity, are only indirectly regarded, i.e., “supporting the biological elements”, when the ecological status of waterbodies is classified, or environmental impacts are assessed. Water bodies assigned to the high ecological status class are an important exception from this rule, as here, the values of hydromorphological quality elements are a part of their classification according to Annex V WFD and must be taken into account when a water body is downgraded. WFD provisions do not fully rule out hydropower development and barrier construction but allow exemptions under Art. 4.7 WFD, even in rivers of high ecological value. A precedent in this regard was set by the ruling of the European Court of Justice on the case of the Schwarze Sulm river in Austria in 2016. The construction of a hydropower plant in a river in high ecological status, although resulting in deterioration, was allowed on the basis of overriding public interest [11]. Overall, barriers are highly relevant to the implementation of two mechanisms in River Basin Management Planning that reduce the environmental ambition for a large share of waterbodies: For the designation of Heavily Modified Water Bodies, the objective for which is not “good ecological status,” but rather “good ecological potential,” and weirs, dams and reservoirs were the most frequent reasons. Secondly, hydropower plants range third among the single reasons for exemptions under article 4.7 WFD [12].

The enormous development pressure on rivers and streams, even in protected areas, was highlighted by the controversial struggle over a guidance document on hydropower and Natura 2000 that was drafted by the EU Commission in 2016. While welcomed by hydropower associations, the document was harshly criticized by a large coalition of environmental organizations such as the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), Friends of the Earth Europe, Rewilding Europe, Euronatur Foundation and Riverwatch, as well as the European Anglers Alliance: “There is very little scope for new hydropower in any of the EU’s water courses and in particular no room for new hydropower plants in Natura 2000 sites or in rivers containing Natura 2000 sites or EU protected species. These sites should rather be the nucleus for a network of free-flowing rivers and streams with high ecological value that should be expanded through the decommissioning and removal of ecologically harmful infrastructure” [13]. It is safe to assume, they argue, that within the Natura 2000 network, the protection of rivers and streams generally may be regarded as the “better environmental option” (Article 4.7 WFD) in comparison to the generation of hydroelectric power.

Finally, as can be concluded from the results of the first and second cycle of River Basin Management under the WFD, European countries and the EU as a community have generally been too timid in applying existing planning tools strategically for the benefit of river landscapes and their ecological restoration. This is particularly true for the removal of dams and other barriers, as well as the urgently needed revitalization of rivers in a regional context with strategic conservation aims. Europe is risking losing outstanding natural heritage and missing great opportunities to regain natural river landscapes. Recent developments, in particular the EU Biodiversity Strategy 2030, address these challenges and provide promising prospects for restoring free-flowing rivers, for which there is an enormous potential through barrier removal. Here, valuable experience might be drawn from countries that already have legal protection schemes for free-flowing rivers in place.

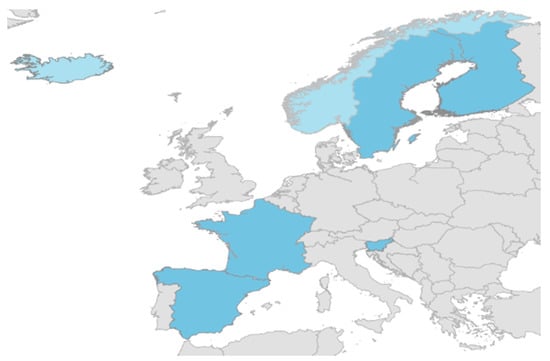

Despite the protection mechanisms for freshwater ecosystems provided by EU legislation, Europe is lacking a cohesive policy for protecting free-flowing rivers, such as the United States Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 that designates selected rivers to be “preserved in a free-flowing condition” [14], while also protecting their “Outstandingly Remarkable Values” that relate to vital ecosystem services of regional and national significance [15]. Without such a policy in place on the EU level, it is important to understand what kinds of national protection schemes for free-flowing river protections do exist in Europe and how they vary across countries, so that they can be considered in the creation of future conservation policies. Notably, a comparative study of European river protection schemes has, until this study, not existed. This study provides an analysis of seven legal protection schemes for free-flowing rivers in Europe, including five European Union (EU) and two non-EU countries (cf. Figure 1), to understand how these policies function, their histories, and their effectiveness. All schemes included here are based on national legislation. These approaches offer many lessons learned and constitute a starting point for envisioning a European policy that would establish a more cohesive system of strictly protected free-flowing rivers.

Figure 1.

European countries with legal protection schemes for free-flowing rivers (EU countries dark blue, non-EU countries light blue).

2. Methods

Legal protection for rivers specifically aiming to maintain their free-flowing character was identified in the seven above-mentioned countries. In several other countries, new protection schemes are being proposed or emerging, e.g., in Portugal, Montenegro and North Macedonia [16]. Most European countries do not provide specific legal protection schemes for free-flowing rivers.

The research for this study consisted of a review of scientific literature, relevant legal texts, policy documents, gray literature, reports and internet resources. To guide the research, help identify relevant documents and support the evaluation of the protection schemes, semi-structured interviews with river conservation experts were conducted in 2019 and 2020. The interview partners were identified following recommendations from environmental organizations and state authorities in the respective EU countries; for the two non-EU countries, Norway and Iceland, no expert interviews were carried out. To structure the interviews, a questionnaire was developed. The experts later kindly supported the research with follow-up email communication. The interview partners represented the following entities.

- -

- Slovenia: Institute of the Republic of Slovenia for Nature Conservation (Zavod Republika Slovenija za varstvo narave—ZRSVN), Nova Gorica Office

- -

- Finland: Finnish Association for Nature Conservation (Suomen luonnonsuojeluliitto—SLL)

- -

- Sweden: River Savers Association (Älvräddarna Samorganisation)

- -

- Spain: New Water Culture Foundation (Fondación Nueva Cultura del’Agua)

- -

- France: Ministry of Ecological Transition, Water & Biodiversity Directorate (Ministère de la transition écologique), DGALN/DEB

Research on the case studies as well as the expert interviews followed a set of guiding questions:

- -

- What is the legal basis of the protection scheme, and when did it enter into force?

- -

- What are the protection mechanisms?

- -

- How many rivers are protected under the scheme, and were rivers added or excluded later?

- -

- Was the protection scheme effective, i.e., were the respective rivers protected against hydropower development, dams and other barriers?

- -

- In which context did the protection scheme emerge, e.g., were immediate threats to rivers averted?

- -

- What is the relation of the protection scheme to the implementation of the Water Framework Directive in the respective country, and does it contribute to achieving the WFD environmental objectives?

Key results are presented in tables for each country examined. Synopses and summaries for existing protection schemes in the seven examined European countries are arranged in chronological order, i.e., according to the year in which strict legal protection for at least one river in these countries first entered into force. However, the two non-EU countries, Norway and Iceland, use very similar approaches to river protection, are therefore grouped together. Key quotes from legal texts are provided in English translation. The numbers of rivers protected under the respective schemes were identified for most countries as far as available.

Limitations for the research resulted from the fact that many sources, especially gray literature, were only available in the respective national languages. Documents in Swedish (also the second official language in Finland) and French were accessible to the author; for other documents, web-based translation tools allowed an approximation. Quotes from legal texts originate from governmental websites, providing translations of the respective laws that serve for informational use only. Detailed information on the respective administrative setup of authorities and agencies in charge of River Basin Management and hydropower permitting was not collected as the mechanisms of the protection schemes can already be understood on the grounds of more basic information. Available geographical information on protected rivers did not allow to provide a European map. The scope of the study is limited to seven legal protection schemes that were in place in European countries in 2019. More recent developments towards river protection schemes on the national level that can be observed in several countries are not included in this review.

3. Overview of Legal Protection Schemes for Free-Flowing Rivers in Seven European Countries

In this section, key elements of each protection scheme are laid out and presented in a synopsis (Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7). Information on the history of each policy creation is included, along with an assessment of the powers, effectiveness and shortcomings of each scheme.

3.1. Slovenia—Law on the Protection of the Soča River of 1976

The “Law on the Protection of the Soča River and Tributaries” of 1976 protects the largely pristine upper Soča river ecosystem in the Julian Alps in a very comprehensive way. It includes physical, chemical and biological characteristics of the river system. The Law established a protected area that “covers riverbeds and water and riverbank lands between the source and the confluence with the Idrijca river” [17]. It can be regarded as the first, strict, legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Europe.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for the Soča River in Slovenia.

Table 1.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for the Soča River in Slovenia.

| Legal Basis | Law on the Protection of the Soča River and Tributaries Slovenian: Zakon o določitvi zavarovanega območja za reko Sočo s pritoki |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 1976 |

| Protection mechanisms | The protection scheme creates a protected area as well as a natural heritage site. It combines legal provisions on the state level as well as the municipal level:

|

| Key quotes from the legal text |

|

| Comments | Potential exemptions are included in the law (Art. 3). The protected area was also included in Triglav national park through the Law on Triglav National Park of 1981. The Tolmin municipal ordinance of 1990 establishes the most stringent protection regime regarding potential exemptions. |

| Number of rivers | 1 (plus tributaries) |

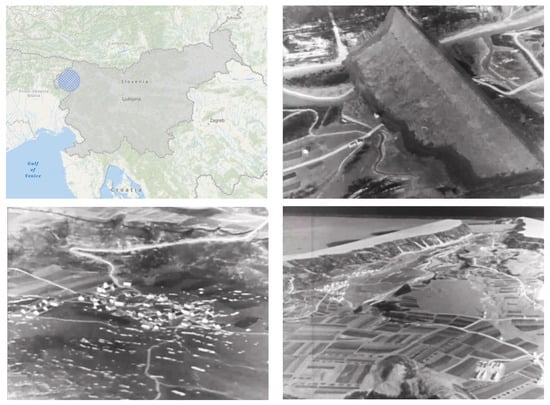

The legal protection scheme for the Soča River predates the national independence of Slovenia and has since remained in force. It resulted from a conflict over hydropower development on this typical alpine river. In the decades after the Second World War, the global “hydropower rush” also took hold in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, of which Slovenia was then part, and threatened some of the most beautiful rivers in the country [18]. In the 1960s, a 120 m high dam was proposed on the Soča at Kobarid, and another hydropower plant with an 85 m high and 780 m wide dam was proposed near Bovec. A tunnel was planned to divert the water to a hydropower plant at Trnovo ob Soči. If completed, the Bovec basin would have disappeared and turned into a reservoir (see Figure 2) [19]. It was also planned to divert water from the Boka spring and waterfall into the reservoir, and in addition, there were plans to dam the Učja river, one of the headwaters of the Soča. Opposition to these projects arose and connected with critical voices against other highly controversial dam projects in Yugoslavia, e.g., on the Tara River in Montenegro [20]. In 1971, local environmental societies merged into the Association for Environmental Protection in Slovenia (AEPS), for which opposition against the construction of hydroelectric power installations on the rivers Soča and Mura was a focus. In this context it is worth mentioning that in the 1970s, new legislation for environmental protection was adopted in Yugoslavia, and new self-government bodies for environmental issues were established [21]. Eventually, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia passed the “Law on the Protection of the Soča River and Tributaries” in 1976 in order to avert any new dam and hydropower projects on this outstanding alpine river.

Figure 2.

Location of the projected dam and reservoir near Bovec on the upper Soča in Slovenia. Stills from historic TV footage (1964) presenting a 1:1250 model of the site [19]. Views on the model clockwise from upper right: Dam (780 m wide, 85 m high), aerial view of the Bovec basin with dam site at the far end, the inundated village of Česoča in the flooded model.

Additional steps later complemented the legal protection scheme for the Soča river: In 1981, the protected area was included in Triglav National Park, which, however, did not introduce elements strengthening the protection scheme for the river. More importantly, in 1990, the local government of the municipality of Tolmin passed an ordinance based on the “Law of Natural and Cultural Heritage” of 1981. Through this ordinance, the Soča, from the source to the confluence with the Tolminka river and along with its tributaries, was designated as a natural monument of national importance (cf. Figure 3). This municipal ordinance added the most stringent elements to the protection scheme for the Soča and its tributaries [19]. In addition, most parts of the protected river system today are also part of the Natura 2000 network. The Government of the Republic of Slovenia, as well as mayors and municipal administrations of Bovec, Kobarid and Tolmin, oversee compliance with the protection scheme for the Soča.

Figure 3.

Soča River, protected as free-flowing river since 1976, near Bovec with Mt. Javoršček in the background (upper left). Corresponding photos to sites in Figure 2: Dam site, calm reach of the Soča downstream Česoča, Bovec basin with village Česoča in front. Photo credits: Daniel Rojšek (3), Seon Crockford-Laserer/Packraft Europe (lower right).

The legal protection scheme has been effective, as no dams were built in the protected river stretches. Still, the pressure to develop hydropower on the Soča and its tributaries remains high, with surreptitious pushes for the construction of power plants. The hydropower company SENG, Soške elektrarne Nova Gorica, still keeps two potential dam sites on the upper Soča as well as one on the Učja on their long-term project list. However, it appears that public opinion remains strongly in favor of the protection of the river [19]. In the case of the Soča, it cannot be overestimated that the natural beauty of the river and its nature as a prime whitewater destination in the Alps has, until today, inspired individuals to stand up for its protection. This was effectively captured in the simple response given by a river conservationist in a telephone conversation with the author in spring 2019, swiftly answering the question of why the Soča was protected: “Because she is beautiful!”

3.2. Finland—River Protections under the Rapids Protection Act of 1987

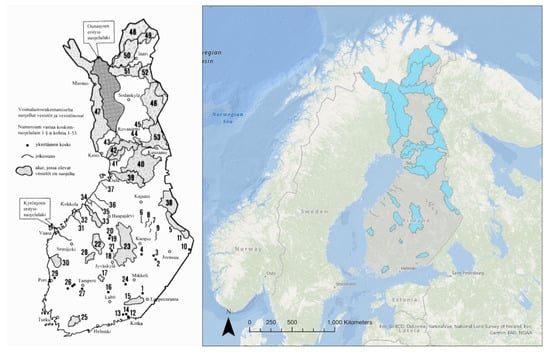

Finland established a legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in the 1980s. It is comprised of three individual laws, of which the Rapids Protection Act of 1987 is the central piece [22]. The legal protection scheme was established specifically to prohibit hydropower development in selected rapids, rivers or river systems (cf. Figure 4). The mechanism behind the Finnish legislation consists of two elements: (1) according to the law, it is impossible to obtain a license as required by the Water Act for a hydropower facility in the designated rivers; (2) the law also provided compensation payments to the owners or those who had the rights to exploit the sites for hydropower. The payments were based on the economic benefit forgone, calculated by the land register office, and given out as a single payment. Ownership and other circumstances remained as they were: “The total number of compensation processes was around 270. Decisions were made on the prerequisites and amount of compensation in almost 1300 separate cases. Compensation was ordered for the heads of about 700 potential hydropower plant sites. About 600 sites or parts of river systems were estimated to be unfavorable for hydropower construction because of an insignificant amount of water or small head, and no compensation was ordered for them in the processes. Altogether, about 400 million marks (67 million Euros) of state funds allocated for the protection of rapids was used for the implementation of these Acts” [23]. There were several court cases where the calculations for individual payments were challenged, but in most cases, the courts upheld the ordinances. By 2004, 17 years after the Rapids Protection Act came into force, all compensation payments were completed.

Figure 4.

Overview maps of legally protected rivers in Finland. Left: Water bodies and parts of water bodies protected from power plant construction [23]. Individual rapids are indicated as dots, river stretches as lines, and areas in which water courses are protected are coloured grey. The numbering follows the list of designated rivers in the Rapids Protection Act (35/1987). Arrows refer to two rivers protected by individual laws. Right: Overview map of protected rivers in Finland. Data source: Koskiensuojelulailla suojellut vesistöt, last edited 22 January 2021, Suomen ympäristökeskus—SYKE (https://www.avoindata.fi/data/en_GB/dataset/koskiensuojelulailla-suojellut-vesistot, accessed on 19 May 2021).

Table 2.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Finland.

Table 2.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Finland.

| Legal Basis | Rapids Protection Act, Act. No 35/1987 Finnish: Koskiensuojelulaki |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 1987 (1983) |

| Protection mechanisms | The Finnish protection scheme consists of two components: 1. Permitting of hydropower projects is prohibited in the designated river stretches 2. Compensation payments to the owners of the respective water rights were made by the state. Payments were based on the economic benefit forgone, calculated by the land register office, and given out as a single payment). All compensation payments were completed by 2004. |

| Key quote from legal text |

|

| Comments | The Rapids Protection Act is the central piece of the Finnish protection scheme, designating 53 river stretches. Two other laws complement the scheme, each designating one river: Laki Ounasjoen erityissuojelusta (703/1983), on the Ounasjoki river Laki Kyrönjoen erityissuojelusta (1139/1991), on the Kyrönjoki river |

| Number of rivers | 55 |

Finland has a long and controversial history of river exploitation for electricity generation. In large parts of the country, rivers and lakes are dominating elements of the landscape, but today, only 10% of the Finnish rivers >50 km remain without dams and are considered to be in a natural condition [24]. It belongs to Finland’s early hydropower history that the scenic Imtra rapids in Southeast Finland, which had been purchased by the state as early as 1883 in order to protect them, were dammed in 1929. Similarly, the Oulujoki rapids, one of Finland’s first nature conservation sites, which the state had bought in between 1913 and 1917 in order to protect their scenic beauty, was sacrificed to hydroelectricity generation in the 1940s [24].

After the Second World War, Finland experienced massive large-scale hydropower development. In part, this was a consequence of the loss of large Finnish territories with high economic potential to the Soviet Union as well as obligations to pay war reparations. Hydropower development planning proceeded on the basis of technical and economic feasibility, while environmental and social impacts were given minor or no attention. The three large river basins draining into the Bothnian Bay of the Baltic Sea, the rivers Oulujoki, Iijoki and Kemijoki-Ounasjoki, supported most of the important remaining Baltic salmon rivers in Finland. All were harnessed for hydropower development with cascades of dams starting in the 1940s. It is worth noting that at this point in time, these same basins were already exposed to significant pressures from other economic activities: The rivers, their tributaries and effectively, most of the catchments, suffered from massive transformation as they were reshaped to serve as floatways for timber in the 19th and 20th century. The hydromorphological degradation of the river channels resulted in the loss of spawning and nursing habitats for fish. In addition, an increased harvest of sea fishing contributed to the decline of catches of anadromous fish as early as the 1900s [25]. The development of hydropower, in combination with existing pressures, resulted in a complete collapse of the naturally reproducing populations of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), Sea trout (Salmo trutta), migratory whitefish (Coregonus lavaretus) and river lamprey (Lampetra fluviatilis). Previously, these populations supported extensive fisheries in the rivers, estuaries and the nearby coastal areas. The loss of salmon in particular meant a dramatic change for local people in terms of loss of economic revenue as well as the cultural heritage of these iconic species [25].

In the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, a series of environmental conflicts over hydropower, the so-called “Rapid Wars,” erupted. Besides nature conservationists, other relevant stakeholders in these conflicts included local citizens, recreational and professional fishermen and artists such as the Finnish poet Reino Rinne, who engaged in one of the conflicts known as the “Kuusamo hydropower wars” [26]. Ultimately, the breakthrough for protecting the remaining wild river stretches came with the development of the “Memorandum of the Committee on the Protection of Rapids” in 1982 [27]. In a first step, this memorandum led to the “Ounasjoki Protection Act” in 1983, Finland’s first legal river protection scheme. It prohibits hydropower development on the Ounas River, its tributaries and the streams flowing into Lake Ounasjärvi in northern Finland. The Ounas River is the largest tributary of the Kemijoki. The scheme was extended by the main “Rapids Protection Act” (Koskiensuojelulaki) in 1987. The members of the Committee represented the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation (Suomen luonnonsuojeluliitto—SLL), Nature and Environment (Natur och Miljö), the environmental administration, the Sami people, and anglers. For their memorandum, the Committee agreed on an explicit listing of sites designated for protection. After a previously assigned working group had failed to come to an agreement, Finland’s first Environmental Minister, Mr. Matti Ahde (Socialdemocrats), played a key role in the success of the proposal. The list of protected rivers was not amended after the third rapids protection law was passed in 1991, on which fact the former president of the Finnish Association for Nature Conservation, Esko Joutsamo, commented that “nobody from our side wanted to open the Act later because if some sites could have been added, some others could have been removed!” [26].

The provisions of the Rapids Protection Act have proven effective: Not a single hydropower facility was built in the designated rivers. Essentially, building a dam in the designated rivers would require a change to the law. Many attempts were made to exempt parts of the Iijoki river from protection in order to build the Kollaja dam and reservoir but did not succeed under multiple governments. The general opinion seems to be that no political coalition should (or could) ever be able to open the laws on Finland’s river protection schemes [26].

The protection scheme of the respective river stretches is not directly linked to any other legally binding management objectives. However, the benefits of river protection can be taken into account in the context of river basin management under the WFD, as well as Finland’s strategy for the restoration of fishways. In this context, it is worth noting that, outside the scope of the Rapids Protection Act, several hydropower projects in Natura 2000-rivers were terminated, most recently a proposal for the hydropower development in the Kemijoki in April 2019.

3.3. Sweden—River Protections under the Swedish Environmental Code of 1999 (Based on Protections under the Natural Resources Act of 1987)

Sweden established a legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in 1987. Four large northern rivers, Torneälv, Kalixälv, Piteälv and Vindelälv, along with a set of 22 other rivers or river stretches were protected from new hydropower development through the Resources Management Act (Naturresurslag). The term “national rivers” (nationalälvar) was introduced for the four above-mentioned rivers, apparently alluding to National Parks but carrying a rather symbolic value. All rivers listed enjoy the same level of protection. In 1999, when the Resources Management Act was repealed, the protection scheme was integrated into the newly established Environmental code (Miljöbalk) [28]. The purpose of the river protection scheme under the Environmental Code is specifically to ensure that these rivers or river stretches are not exploited for hydropower and are not regulated or diverted for this purpose: “Hydroelectric power plants and water regulation or water transfer for power purposes shall not be carried out” [28]. Notably, since 1999 these provisions also include source streams and tributaries, increasing the reach of the protection regime to the upstream river system (cf. Figure 5). Surprisingly, however, many of the protected rivers under this scheme were already affected by dams before their designation. The Torne River with its Swedish tributaries and the Kalix River remain the only rivers with no dam and no hydroelectric facility. On the Pite River, a large-scale dam located fifteen kilometers from the mouth was relicensed, and the power plant was rebuilt in 1990. The Vindel River is a free-flowing tributary to the Umeälv, in which Sweden’s second-largest hydropower plant is located just a few kilometers downstream from the confluence [29].

Figure 5.

Overview map of legally protected rivers under the Swedish Environmental Code. River basins of Sweden’s four national rivers Torneälv, Kalixälv, Piteälv and Vindelälv in dark blue. Data sources: LST Riksintresse Skyddade Vattendrag MB4kap6, Länsstyrelserna, last edited 14 May 2021, revision pending (https://ext-geodatakatalog.lansstyrelsen.se/GeodataKatalogen/, accessed on 19 May 2021) and European river catchments (ERC), last modified 28 June 2016, European Environment Agency—EEA (https://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/european-river-catchments-1, accessed on 19 May 2021).

Table 3.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Sweden.

Table 3.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Sweden.

| Legal Basis | Resources Management Act, Act No. 1987/12 Swedish: Lag om hushållning med naturresurser (Naturresurslag) since 1999: Environmental Code, Act No. 1998/808 Swedish: Miljöbalk |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 1987 |

| Key quote from legal text |

|

| Protection mechanisms | Under the Swedish protection scheme, hydropower plants, including water regulation or water diversion for energy purposes, are prohibited in the designated river stretches and their floodplains as well as tributaries and source streams. |

| Comments | The Swedish river protection scheme was first introduced into the Natural Resources Act in 1987. The scheme was transferred to the Swedish Environmental Code, which replaced the Natural Resources Act and entried into force in 1999. The protection of tributaries and source streams was first included in 1999. |

| Number of rivers | 26 (plus tributaries and source streams) |

It is fair to say that Sweden is a hydropower-focused country. There are some 2100 hydropower stations in Sweden, 1900 of which are considered small (<10 MW) and 210 large (>10 MW). The latter produces 94% of Sweden’s hydroelectricity while in comparison, 1030 very small (<125 W) facilities produce less than 0.5% of all electricity. A total of 1570 dams are in place for regulating water flows related to hydropower. This development has caused dramatic effects on river ecosystems as well as fisheries: “Today, there are only 16 wild salmon rivers left in Sweden that support self-sustaining populations, compared to at least 28 before the development of rivers for hydropower. In those rivers with hydropower and wild salmon, reproduction rates are low. Most of the largest salmon rivers have been fully developed, and there is no natural salmon population left. This is true e.g., for Luleälv, Skellefteälv, Umeälv, Ångermanälv, Ljusnan, and others” [30].

Most of Sweden’s hydroelectricity is generated in complex systems of large dams and reservoirs in the northern rivers. In the process, their flow regimes were entirely transformed, resulting in dramatic changes in the rivers and their floodplains. With the hydrographs flattened, “the water system loses its annual rhythm” [31]. Until the 1960s, when nuclear power come into play, nearly all of the country’s electricity was generated from hydropower. This share has continuously decreased and remains at roughly 40% today [32]. It is a noteworthy aspect of the historic background of river policies in Sweden that, not unlike Finland, the country’s rivers not only suffered from hydropower development but also from activities related to the development of the export-oriented forest industry in the 19th and 20th century, when northern Sweden’s rivers were changed into floatways for timber. These activities have resulted in a fundamental transformation of the rivers and their ecological characteristics, so that the period of log driving, which, for example, in the case of the Vindelälv, ended in 1976, “has left an almost indelible imprint” [33].

The beginnings of river development for hydroelectric power generation date back to the late 19th century. The majority of all existing facilities (mainly smaller hydropower plants) were built in the early 20th century. Around the same time, the exploitation of the large northern rivers, i.e., their rapids and waterfalls, commenced. The state-owned enterprise Vattenfall, founded in 1909 as the Royal Waterfall Board (Kungliga Vattenfallsstyrelsen), was a major player in the process of harnessing Sweden’s rivers. Also, the Water Act of 1918, with its provisions on reasonable use, made the exploitation of hydropower a priority, supported by the newly established water courts [31]. Regulated rivers in Sweden were developed with little consideration of the ecological impacts, with most dams lacking migration pathways or minimum flow releases and aligned in consecutive cascades [34]. The case of the Suorva dam epitomized the aggressive character of these large-scale projects from the very beginning when a dam was built in the Lule river in Lappland in 1919 to create Sweden’s first large storage reservoir. The Surva dam site had been part of Stora Sjöfallet National Park, one of the first nine Swedish national parks that were established in 1909, but, only ten years later, the site was carved out again from the national park by decision of the Swedish Parlament Riksdag in order to allow dam construction. The dam and water diversion effectively wiped out Sweden’s largest waterfall Stora Sjöfallet, the park’s name-giving Great Waterfall [35].

In the second half of the 20th century, growing controversies around the massive development of new hydropower became one of the main concerns for the growing environmental movement in Sweden. As the country’s hydropower sector grew immensely, many struggles to defend rivers were lost. Among the important milestones for river protection in Sweden were the successful fight for the Vindelälv in the 1970s, as well as protests against a hydropower project for the Sölvbacka strömmar rapids in the Ljungan river in Jämtland in 1980, when the Swedish parliament decided to cancel the controversial project (with a remarkably close margin of just one vote), and instead purchased the respective water rights [36]. The advocacy work of Sweden’s River Savers Association (Älvräddarna Samorganisation) is seen as a key factor in the long political debate and the eventual protection of the remaining free-flowing rivers in Sweden. Älvräddarna is an environmental civil society organization devoted to river protection that was founded in 1974 [29].

The struggle over Sweden’s rivers has gone on for decades, with a complex history including environmental, social and human rights aspects. For reindeer husbandry in Sápmi, the region of northern Fennoscandia traditionally inhabited by Sámi, “the consequences and cumulative effects of this large-scale landscape conversion, and the societal changes it entailed are still largely a story to be told” [37]. Under the title “Hydropower: For and Against,” a comprehensive summary of the arguments that over the past decades have been brought forward in favor and against hydropower development in Sweden provides a useful overview of this long and arduous dispute [38].

Regarding the effectiveness of river protection under the Environmental Code, it can be concluded that the scheme has worked well since the law was adopted by the Swedish Parliament in 1999. At their hearings, concerned parties have a right to speak, including Älvräddarna, Recreational Fishermen (Sportfiskarna), the Swedish Association for Nature Conservation (Naturskyddsföreningen), and WWF Sweden. An exemption was added to the Swedish scheme in 2018, mandating that measures necessary for the maintenance, upkeep, or alteration of an installation or activity may be taken if they do not result in any increased negative impact on the environment or only in a temporary increase of such impact. Relicensing or applications for new hydropower projects in these designated rivers are handled by one of five environmental courts in Sweden. Hydropower companies had always aimed to challenge the scheme with applications for new or refurbished hydropower plants in the protected rivers, but only one such application—a small-scale facility that had been in place since the beginning of the 20th century—was approved by the respective environmental court [29]. Nearly all of the 26 protected rivers were later also designated as Natura 2000 sites.

New prospects for ecological improvements of Sweden’s protected rivers were provided through an amendment of the Environmental Code that came into force in 2019. It requires the re-evaluation and relicensing of all existing hydropower facilities in Sweden within a period of twenty years (2020–2040) under a national plan for the revision of hydropower plant licenses [39]. In this context, Älvräddarna points out that, currently, only an extremely small proportion of the hydropower plants adhere to environmental requirements: barely 5% (100 out of 2100) are in line with environmental laws, i.e., relicensed or rebuilt under the Environmental Code, and about 30% lack any license whatsoever. Älvräddarna and partners advocate a prioritization: rivers protected under the Environmental Code “priority rivers” should be regarded in the first decade. Related to the 2019 amendment, a new funding scheme, the Hydroelectric Environmental Fund (Vattenkraftens Miljöfond), endowed with approximately 10 billion SEK, was set up by eight hydropower companies. Intended for environmental upgrading or dismantling of hydropower facilities, it was recently introduced to accompany the new legal requirements. The fund will cover up to 85% of the costs for the license revision in court, for implementing the environmental adaptions required to fulfill modern environmental conditions, or for decommissioning the plant, based on the decisions taken by the owner [40]. The 2019 law might also offer a chance to reinvestigate and address the negative impacts of hydroelectric projects on Sámi lands and culture in Sweden [41].

3.4. Spain—River Nature Reserves under the Water Law of 2006

In Spain, a legal protection scheme for River Nature Reserves (Reservas Naturales Fluviales) was introduced into the Spanish Water Law (Ley de Aguas) in 2005, mandating that all River Basin Management Plans designate such river reserves in order to preserve rivers and streams in pristine or near-natural condition [42]. The scheme aims to protect the best rivers in the country (cf. Figure 6). These rivers serve as reference rivers under the WFD and, as such, play an important role in the management and ecological restoration of other rivers.

Figure 6.

Overview map of rivers protected as River Nature Reserves (Reservas Fluviales Naturales) under the Spanish Water Law. Data source: Reservas Naturales Fluviales declaradas, last edited 2 March 2021, Ministerio para la Transición Ecológica y el Reto Demográfico (https://sig.mapama.gob.es/geoportal/, accessed on 19 May 2021).

Table 4.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Spain.

Table 4.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Spain.

| Legal Basis | Water Law Spanish: Ley de Aguas |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 2005 |

| Protection mechanisms | The Spanish river protection scheme establishes River Nature Reserves (Spanish: Reservas Naturales Fluviales) as freshwater protected areas. |

| Key quote from legal text |

|

| Comments | The Law on the National Water Plan in 2001 introduced the rather general option to create “hydraulic reserves.” The Water Planning Regulation in 2007 specified objectives and functioning of the River Nature Reserves scheme. |

| Number of rivers | 135 |

In 2001, the Law on the National Water Plan had already introduced the rather general option to create “hydraulic reserves.” Advocacy work and a proposal for a legal scheme by the environmental organization Ecologistas en Acción played a decisive role in the introduction of the new scheme of River Nature Reserves into the Water Law 2005 in Article 42 (Content of the river basin management plans):

“1. The river basin management plans shall compulsorily include:

(b) The general description of the uses, pressures and significant anthropic impacts on the waters, including: …

(c’) The allocation and reservation of resources for present and future uses and demands, as well as for the conservation and recovery of the natural environment. For this purpose, the following shall be determined: …

river nature reserves, with the purpose of preserving, without alterations, those sections of rivers with little or no human intervention. These reserves will be strictly limited to the public hydraulic domain”.[42]

Ever since, environmental groups maintain pressure to further develop and implement the scheme [43]. The Water Planning Regulation of 2007 further developed the protection scheme of River Nature Reserves, establishing their objectives, identifying authorities responsible for their oversight, defining criteria for their designation, etc. The central aim of the reserves is to ensure that river stretches showing no or little human alterations maintain their high natural status. The protection regime provides that no new water concession can be granted (except in case of emergency for urban water supply), and that no activities shall be permitted that might affect the hydromorphological conditions and other natural properties of the river [44]. Though not specifically mentioned, this would include the free-flowing character of the river. The protection scheme applies only to the so-called public hydraulic under Spanish law: River Nature Reserves include the river channel, water flow and banks of five meters on each side. The public hydraulic domain is administered by Water Offices, while the administrative responsibility for adjacent lands belongs to the Autonomous Communities [44].

A proposal from the National Catalog of Reservas Naturales Fluviales compiled 357 river reaches with an approximate length of 3000 km. This was reviewed by the basin district committees, with regard to fish communities and invasive species as well. The final results for each basin were included in the respective River Basin Management Plans. The first list of 53 such reserves was designated in 2015 by the Agreement of the Ministers Council, followed by another 82 in 2017, totaling 135 reserves with 2669 km of rivers under protection. The reserves are designated in two ways: In river basins belonging to more than one Autonomous Community by the Council of Ministers, and in river basins belonging to only one Autonomous Community by their respective authorities. In 2018, one of these basins, the Balearic Islands, designated nine reserves. River Nature Reserves are typically located only in the first kilometers of the river, in the headwaters, and many of them are quite small [44].

The designation of River Nature Reserves has not met much opposition from economic sectors as in most cases, as uses of the respective watercourses were already quite limited. The effectiveness of the Spanish river protection scheme has not been reviewed at this early stage. The success of the approach will also depend on whether a good coordination scheme between the state and the Autonomous Communities can be established in order to achieve more comprehensive protection, including not only the rather narrow river reserve corridors but also wider riparian zones and floodplains [43]. Furthermore, as management plans for the designated river stretches have not been developed yet, an important building block of the scheme is still missing. Most reserves are also part of Natura 2000 sites. Environmental groups, particularly Ecologistas en Acción and the New Water Culture Foundation, push for the expansion of the network. In order to assist river basin authorities in expanding the network of River Nature Reserves, methodological guidelines were elaborated [45].

3.5. France—River Protection under the Environmental Code and the Law on Water and Aquatic Environments of 2006

In France, River Basin Management Plans include lists of rivers in which hydropower development is excluded, and free flow is protected. The protection scheme is complemented by a systematic planning approach to prioritize the removal of barriers in rivers in order to restore continuity, river dynamics and free flow. France has made the ecological continuity of rivers a central element in river policy and planning. Accordingly, continuity is also a parameter for environmental quality in river monitoring programs. Strict protection of free-flowing rivers in France is implemented through legal requirements for River Basin Management Planning in the Environmental Code, based on the Law on Water and Aquatic Environments [46]. In 2006, this law transposed the Water Framework Directive and motivated extensive initiatives on river continuity. It required the French river basin authorities to identify rivers according to a two-category classification system: “List 1” lists rivers or river stretches protected in order to protect their very good ecological status, achieve good status, because of their importance as a biological reservoir, or for migration of diadromous fish. In these rivers, “no authorization or concession can be granted for the construction of new works if they would represent an obstacle to ecological continuity” [46]. Relicensing of existing facilities is subject to the same set of environmental objectives. “List 2” identifies rivers or river stretches to be restored.

Table 5.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in France.

Table 5.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in France.

| Legal Basis | Code de l’Environnement Environmental Code, modified by the Law on Water and Aquatic Environments, Law No. 2006-1772 French: Environmental Code and Loi sur l’eau et les milieux aquatiques, |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 2006 |

| Protection mechanisms | France follows a planning approach obliging River Basin Authorities to established lists of rivers as part of River Basin Management Plans under the WFD (so-called “list 1” rivers). River protection is established in three steps: 1. For each basin, “list 1” compiles a selection of rivers or river stretches that should be protected in order to maintain their very good ecological status or achieve good status or because of their importance as a biological reservoir or for migration of diadromous fish. 2. Legally binding protection for these rivers is established through prefectural decrees on the basin scale. 3. Permitting is prohibited for any project that would constitute an obstacle to river continuity. |

| Key quotes from legal text |

|

| Comments | Relicensing of existing facilities is subject to the same set of environmental objectives. |

| Number of rivers | There is no number of rivers available. In total, “list 1” rivers account for approximately 30% of all French rivers under WFD reporting requirements. |

For the restoration of rivers on “list 2,” the legal framework requires sufficient flow of both water and sediment in the river for its healthy functioning and aims to do so within the next 5–10 years. Both lists were finalized for all French river basins by 2012/13 and became legally binding through prefectural decrees on the basin scale. In total, “list 1” rivers accounted for approximately 30%of all French rivers, and “list 2” rivers accounted for 11%.

It is still too early to summarize the effectiveness of the French protection scheme. With almost a third of all rivers protected, the protection scheme has since been challenged in a number of legal cases. Similarly, with some 20,000 barriers identified in “list 2” rivers, the requirements to refurbish existing hydropower facilities and barriers in order to achieve ecological continuity within 5 years met frequent opposition. A national reconciliation action plan was launched in 2018 to facilitate solutions involving all stakeholders. It aims at finding case-by-case solutions for conflicts of interest, considering local contexts and issues. A second prioritization was finalized in 2020 as to which dams and barriers to remove with the aim of realizing the required improvements for ecological continuity on 5000 weir sites by 2027 [40]. Requirements from the French Eel Management Plan (implementing the EU’s Eel Regulation) of 2009, which identified around 1500 barriers country-wide to be erased or equipped in order to allow eel migration by 2015, were integrated in this exercise. In order to assess the impact of obstacles to flow on the movement of the main fish species in continental France, a protocol was elaborated and has been applied since 2015 [47].

With regards to the historic context of the French protection scheme, it is worth noting that over the last decades, France has seen quite remarkable successes in protecting free-flowing rivers and restoring them through dam removal, most notably on the Loire and Allier rivers in the 1990s as well as on the Sélune in 2020. This process is embedded in a conceptual shift in river management in which, again, the Loire basin has played a prominent role. At the same time, France is the largest hydropower producer among the EU countries, and new hydropower development is a serious environmental conflict.

The French approach of labeling wild rivers based on an ambitious set of 47 socio-ecological criteria deserves to be mentioned in this context [48]. Starting from an initiative of the French NGOs European Rivers Network (ERN) and WWF France in 2013, the French Wild Rivers Foundation (Fondation Rivières Sauvages) created a Wild Rivers label and is currently exploring how to apply the certification scheme to rivers in other countries in the Alps region. The idea of certifying wild rivers is advocated by ERN and Fondation Rivières Sauvages as a stepping stone for achieving permanent protection of wild rivers or river stretches by building a constituency and gaining public support and visibility for the idea of protecting wild rivers. While quite successful in the country-specific context and tied to the well-established French system of River Basin Management, it is a private initiative not intrinsically linked to the establishment of legal protection schemes. Legal protection status is not part of the certification criteria.

3.6. Norway—River Protection under the Water Resources Act of 2000 and the National Protection Plan for Water Courses

The Norwegian approach aims to balance the country’s ongoing massive hydropower development with the protection of selected rivers: While the “Master Plan for Water Resources” aims at bringing groups of hydropower projects forward for licensing, the associated “Protection Plan for Watercourses” designates rivers for protection. Licensing procedures were adapted accordingly. Before, decisions on hydropower development were made on a case-by-case basis. In the light of increasing conflicts over river exploitation, the need for a broader perspective became apparent.

Table 6.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Norway.

Table 6.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Norway.

| Legal Basis | Law on River Systems and Groundwater (Water Resources Act), Act No. 82/2000 Norwegian: Lov om vassdrag og grunnvann (Vannressursloven) |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 2000 |

| Protection mechanisms | Norway applies a strategic planning approach to balance hydropower development and river conservation on the national level through the National Protection Plan for Water Courses. Through the Water Resources Act, the Protection Plan for Water Courses became statutory. |

| Comments | Provisions for protected rivers are specified in Chapter 5, Sections 32–35. The protection plan adopted by plenary resolution of the Norwegian parliament Storting. |

| Key quotes from the legal text |

|

| Number of rivers | 390 |

The hydropower development side of the Norwegian strategic planning approach can be summarized as follows: “The scope of the Master Plan is to present a priority grouping of hydropower projects to be brought forward for licensing. The priority grouping is the final result of an evaluation of development costs versus conflicts with other interests. In order to investigate the professional basis for the Master Plan a total of 16 user interests were defined: Hydropower, nature conservation, outdoor recreation, wildlife, water supply, protection against pollution, cultural monuments and cultural environments, agriculture and forestry, reindeer husbandry, prevention of flooding, prevention of erosion, transport, formation of ice and water temperature, climate, mapping and data, and the regional economy” [49]. For every project considered in the Master Plan, these interests are evaluated and included in a report on each river basin. Work on the Master Plan is headed by the Ministry of the Environment (MOE), in collaboration with the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (OED), the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE), the Directorate for Nature Management (DN) and other relevant institutions. The Master Plan for Water Resources was originally presented to the Norwegian Parliament Storting in 1985 and has been updated in 1988 and in 1993 [49].

On the conservation side, the Watercourse Protection Plan was elaborated on the national level, in close cooperation between the energy and water authorities and the environmental authorities. The plan is administered by the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy (OED) and the Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (NVE), in cooperation with the Ministry of the Environment (MOE) and the Directorate for Nature Management (DN). The plan is based on an evaluation of different conservation values and other interests related to the watercourses, including cultural heritage, fish, wildlife, outdoor recreation, pollution control, agriculture, forestry and husbandry. It resulted from a collaboration between NVE, DN and the Ministry of Agriculture that started in 1968, supervised by a committee. The conclusions were presented in four reports (the first in 1970 and the last in 1991). The parliament adopted four protection plans between 1973 and 1993, with supplements in 2005 and 2009. Collectively, these plans are referred to as the Protection Plan for Watercourses. Following decades of negotiations, the Protection Plan for Water Courses became statutory through the Water Resources Act in 2000 [49].

In total, 390 river systems, or parts of river systems, with a hydropower potential of 49.5 TWh/year (roughly 25% of Norway’s total hydropower potential) are excluded from development and other types of encroachment that could counteract the protection targets [50], In theses localities, protection aims are given “preponderant weight” according to the Water Resources Act, allowing authorities to deny hydropower licensing [51]. A designated locality may be a whole river basin system, a part of a river basin system, or an area including many small river basins [49]. While Norway has formally protected a large set of rivers from hydropower development by implementing its Protection Plan, the country is massively pushing new hydropower in others. Far from a strict implementation of the non-deterioration obligation of the Water Framework Directive (which Norway has enacted), the Protection Plan merely aims to direct hydropower development toward low-conflict rivers and away from high-conflict rivers. Moreover, the 2005 supplement to the Protection Plan decreed that hydropower projects with a capacity below 10 MW are exempt from the Master Plan: “Licensing for projects between 1–10 MW are reviewed and granted directly from [the] Water Resources and Energy Directorate and those <1 MW are delegated to county authorities. The 2005 supplement also permitted licensing of projects <1 MW in protected rivers, however only if the development is not contradictory to any of the protection criteria. Responding to increasing demand for renewable energy, small hydropower development has increased with more than 350 plants of 1–10 MW built in Norwegian rivers between 2001 and 2014” [50]. In light of the exemptions, the Norwegian protection scheme appears substantially less strict than those of other European countries.

Norway is the largest producer of hydroelectricity in Europe and among the largest in the world. Industrial exploitation of rivers for hydroelectricity generation began in the early 20th century. Two important laws of 1917, the Industrial Licensing Act or Waterfall Rights Act and the Watercourse Regulation Act, are still part of the legal basis for hydropower development. In the history of Norwegian hydropower development, the violent conflict over the construction of the Alta River hydropower plant with a 110 m high dam completed in 1981 might be regarded as the most controversial hydropower project. This project heavily affected the livelihoods of Indigenous Sámi people in the Finnmark region, particularly regarding reindeer herding and fishing [52]. Following the conflict, Norway began to redefine the state’s relationship to Sámi culture and the legal position of the Sámi people.

3.7. Iceland—River Protection under the Master Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization and the Master Plan Act of 2011

Iceland is legally protecting selected free-flowing rivers while opening others to exploitation by means of considerable new hydropower development. The decisions are based on a planning approach on the national level: The Icelandic Master Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization (áætlun um vernd og orkunýtingu landsvæða) or short Master Plan (rammaáætlun) is an attempt to rank all major potential energy projects in order to prepare parliamentary decisions on either the protection or the development of the sites [53]. In its earlier phase, the plan was also referred to as Framework Plan for the Use of Hydropower and Geothermal Energy (Rammaáætlun um nýtingu vatnsafls og jarðvarma) [53]. Iceland is following a similar path as Norway, and in fact, the Norwegian approach is seen as a role model. The idea for such a plan was already outlined in a parliamentary resolution of the Icelandic Parliament Alþingi in 1989 that mandated the government to draft a plan “concerning the conservation of rivers and geothermal areas, waterfalls and hot springs” [53]. The first actual plan was initiated in 1997, when the Icelandic Government published a white paper on sustainability in the Icelandic society that stressed the need for the development of a long-term Master Plan for energy use, which “should specifically cover the conservation value of individual basins and the conclusions then to be aligned with zoning plans” [53]. Work on the Master Plan started in 1999. Since 2011, the Master Plan is based on the new legal framework of the Master Plan Act (Act No. 48/2011) [53].

Table 7.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Iceland.

Table 7.

Synopsis of the legal protection scheme for free-flowing rivers in Iceland.

| Legal Basis | Act on the Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization (short: Master Plan Act), Act No. 48/2011 Icelandic: Lög um verndar- og orkunýtingaráætlun |

|---|---|

| Year of origin | 2011 |

| Protection mechanisms | Iceland applies a strategic planning approach to balance hydropower development and river conservation on the national level through the Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization (short: Master Plan); Icelandic: Áætlun um vernd og orkunýtingu landsvæða (short: Rammaáætlun) River protection is established in four steps: 1. Evaluation of all hydropower projects with an installed capacity >10 MW is mandatory under the Master Plan; public as well as privately owned lands are covered. 2. Rivers are classified into categories development, protection or on hold in the Master Plan. 3. Binding legal protection is granted through the parliamentary decision on the Master Plan. 4. For rivers in the protection category, no hydropower permitting is allowed. |

| Key quotes from legal text |

|

| Comments | The Master Plan is revised on a recurring basis every 5 years and underwent four phases since 1999. Since 2011, it is based on the Master Plan Act. As of 2021, only one decision resulting in strict legal protection of selected rivers has been taken by the Icelandic Parliament Alþingi, categorizing the rivers from the Master Plan’s phase 2: Parliamentary resolution on the Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization of 2013 (Resolution No. 13/141). |

| Number of rivers | 11 |

Objectives of Iceland’s Master Plan Act, as stated in article 1, are “to ensure that the utilization of geographical areas where there are power plant options, is based on long-term views and a comprehensive evaluation of the interests involved, taking into account the conservation value of nature and of cultural-historical relics, the cost-effectiveness and profitability of various different options for utilization and other values that affect the national interest, as well as the interests of those who use these same resources having sustainable development as a guide” [53]. The Act covers both privately owned land and public lands and applies to hydropower projects with an installed capacity of 10 MW or more. A steering committee plays a central role in evaluating the projects and recommending the protection or development of the rivers under consideration.

The Plan for Nature Protection and Energy Utilization as defined by the Master Plan Act in article 2 “contains the formulation of a strategy … for whether a land area where there are power plant options should be utilized for energy generation, or whether there is a reason to protect these areas or if they should be explored further. Power plant options in the relevant areas are accordingly classified into an energy utilization category, a protection category, or an on hold category” [53]. Regarding the legal protection of free-flowing rivers, Article 6 of the Master Plan Act is key, because it prohibits the licensing of energy projects or related surveys. Article 6 also obligates the government to elaborate protection regimes for the respective areas, whereby protection for nature conservation purposes is carried out according to the Act on Nature Protection, and protection with respect to cultural-historical relics is subject to the National Museum Act.

Under the Master Plan, the legally binding categorization of selected Icelandic rivers as protected to date applies only to the eleven rivers that were included in the “parliamentary resolution on the Plan for nature protection and energy utilization” (resolution No. 13/141 of 2013) [53]. In this resolution, eleven rivers were included in the protection category, two rivers were included in the development category, and twenty-two rivers were included in the “on hold” category (with one river shifted into the development category in 2015).

A distinct difference from its Norwegian role model is that Iceland’s Master Plan is foreseen to under regular revisions and parliamentary decisions. Under the Master Plan Act, the minister responsible for the environment, in consultation and collaboration with the minister responsible for energy, has the duty to present to the Icelandic Parliament Alþingi, at a minimum every four years, a proposal for a resolution concerning the Plan for nature protection and energy utilization [53]. The implementation of Iceland’s Master Plan has so far occurred in four phases:

- The first part of the Master Plan (1999–2003) concluded with a report that discussed 19 power plant options for ten glacial rivers as well as 22 options for the exploitation of geothermal energy. Most of the work was carried out by four expert committees, one of which evaluated and ranked the alternatives based on considerations of the natural environment and cultural heritage. Recommendations for legal categorization were further developed in the second phase.

- In the second phase of the Master Plan (2004–2013), 35 hydropower projects along with 48 geothermal projects were submitted for assessment. On 14 January 2013, the Icelandic Parliament Alþingi passed a parliamentary resolution on these projects, by which the Master Plan came fully into force for the first time.

- The third phase of the Master Plan (2013–2017) was the first to be carried out according to the Master Plan Act of 2011. In total, 88 projects (hydropower, geothermal and for the first time also wind energy) were initially submitted to be evaluated by the steering committee. While the main task in this phase was to complete the evaluation of the projects that had not been appropriately categorized in the second phase, a number of new projects were also introduced. Eventually, only 26 projects were selected for detailed evaluation. A proposal for the categorization was presented to the Icelandic Parliament in the fall of 2016 and again in the spring of 2017. However, neither of those proposals was fully processed by the Parliament and thus never came up for a vote.

- The fourth phase of the Master Plan (2017–2021) began with the formation of a new steering committee. It appears unclear what projects will be evaluated in the fourth phase. The recommendations of the steering committee of the third phase are not yet reflected in the current Master Plan [53].

The Master Plan, although not officially termed a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA), can be regarded as comparable to and does contain key elements of an SEA. A policy-level exercise that “aims to foster sustainable development by considering the environmental, economic and societal consequences of different alternatives, and provides for public participation” [54]. Besides nature conservation, the steering committee and its expert committees have to take into account a number of further aspects: cultural-historical relics; travel industry; tourism and outdoor life; hunting and fishing; grazing resources and other soil resources; macroeconomic issues, economy and regional development as well as public health [53]. The method developed to evaluate and rank projects in the 2003 report (Master Plan phase 1), based on the impact upon the natural environment and cultural heritage, built on the example of the Norwegian Plan for Watercourses. “The three-step procedure involved assessing (i) site values and (ii) development impacts within a multi-criteria analysis, and (iii) ranking the alternatives from worst to best choice from an environmental–cultural heritage point of view. The natural environment was treated as four main classes (landscape + wilderness, geology + hydrology, species, and ecosystem/habitat types + soils), while cultural heritage constituted one class.” Values and impacts were assessed regarding diversity/richness, rarity, size (area), completeness/pristineness, information (epistemological, typological, scientific and educational) as well as symbolic value, international responsibility and scenic value [54].

Information on the effectiveness of the protection scheme was notaccessible. In an evaluation of the Icelandic approach, the OECD’s third Environmental Performance Review on Iceland in 2014 concluded that in adopting the Master Plan, Iceland took an important step towards addressing the trade-offs between power production, tourism and nature conservation. Illustrating the enormous development pressures on Iceland’s rivers and rugged landscapes, the report stresses that “the country’s electricity output has more than doubled since 2000 to nearly five times the amount needed by the population of 320,000, mainly to fuel three foreign-owned aluminium smelters,” and recommends “reinforcing the scientific and economic analysis in the next phase of the Master Plan and reassessing the prices Iceland sells electricity for to factor in the costs of caring for the environment” [55].

4. Discussion

A compilation of seven national legal protection schemes for free-flowing rivers in Europe was provided in Chapter 3. It allows, as a first such overview, a comparison of these protection schemes and an evaluation. This chapter examines three aspects that reflect the leading questions introduced in the methods section: How do the various elements of the protection schemes relate to each other? What can be said about their effectiveness? How do the protection schemes relate to the implementation of the Water Framework Directive? Lastly, future research needs are identified. The evaluation and findings provided underlie the same limitations outlined in the methods section.

4.1. Legal Basis and Mechanisms of the Examined River Protection Schemes

The seven case studies, along with the synopsis in Table 8, outline all core elements that are relevant to understand the functioning of the examined river protection schemes. In all cases, the legally binding character of the protection schemes results from legal provisions on the national level. Additional executive or parliamentary decisions are needed in France, Spain and Iceland, determining that rivers identified in a prior planning process are included in the respective protection scheme. In the case of France, this process involves regional executive competence on the prefectural level. Spain’s Autonomous Communities, i.e., regional authorities, designate river reserves in certain cases, namely if the respective river basin lies entirely in one such region. Municipal decrees play a special role only in the case of the Soča river in Slovenia, complementing a national law and adding components to the protection scheme.

Table 8.

Legal basis and mechanisms of protection schemes for free-flowing rivers in seven European countries in overview.

Objectives of environmental policies are often implemented and enforced through a combination of mechanisms or a mix of instruments. In the case of the examined schemes, such elements include, on the basis of legal provisions, the establishment of protected areas in order to protect river integrity, the prohibition of hydropower permitting, compensation payments to owners of water rights, as well as the use of planning instruments. While the schemes in Finland and Sweden are focused on the prohibition of hydropower permitting, the wider concept of river integrity protection as provided by protected areas in Slovenia and Spain should effectuate such prohibitions. In Iceland, the designation of rivers precludes hydropower permitting and, in addition, mandates the establishment of protected areas for the respective rivers. Only the Finnish scheme includes compensation payments to owners of water rights, based on the economic benefits forgone. The preclusion of hydropower development is thus safeguarded, not only because permitting is prohibited, but also because by being compensated, the owners give up their claims. Similar to a Strategic Environmental Assessment, Norway and Iceland identify candidate rivers for strict protection while carrying out master planning for new hydropower development. Spain and France integrate the identification of candidates into River Basin Management Planning (cf. Section 4.3).

As a matter of principle, the scope of environmental protection schemes is, to a large degree, also determined by the exemptions they include, i.e., to which aspects of the protection scheme exemptions apply and to what extent. With the exception of Finland, all schemes do include exemptions to varying degrees. While it is beyond this study to evaluate all exemptions, it is, however, noteworthy that in the Slovenian case, the municipal decree reduces the range of exemptions by defining stricter preconditions than the national law. In Sweden, exemptions in the designated rivers apply only to preexisting hydropower facilities and their renewal. In France, barriers lower than 50 cm may be newly erected in designated rivers after an exemption was introduced by governmental decree. On the range of exemptions in the Norwegian scheme, further investigation is needed.

4.2. Effectiveness and Geographical Scope of the Examined River Protection Schemes