Abstract

This study develops a model based on perceived effectiveness of e-commerce institutional mechanisms (PEEIM) and trust-based mechanisms to explain how PEEIM, product monetary value (MV), product evaluation cost (PEC), and enjoyment influence trust online vendor (TV) and how they affect purchase intention (IP) and reuse intention (IR) in e-shopping. The study is based on a survey of 293 online shoppers in Taiwan. Results show that monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment have a positive relationship with trust in online vendors, and a positive indirect and significant relationship on intention to purchase and reuse the products or service in the e-shopping environment. However, PEEIM does not have indirect effects on the customer’s intention to purchase and reuse the products or services through the influence of trust online vendor if the influence of PEEIM on customer trust online vendor is low and no significant effects, but PEEIM does have significant direct effects on a customer’s purchase and reuse intention. In addition, PEEIM has two constantly indirect relationships with a customer to purchase and reuse intention the product or services through the influence of customer enjoyment and customer trust in online vendor relationships. The study contributes important theoretical and practical implications for scholars and e-commerce providers.

1. Introduction

Advanced information technology (IT) has made internet shopping an essential mode of business transactions [1,2], One reason for this is that customers find it more beneficial to purchase from an e-shopping platform than an offline store, due to reduced product evaluation cost and increased product monetary value. While customer enjoyment is one of the unreadable assessments in online purchase behavior that led by customer trust and increasing intention to reuse the on-line vendors [3]. In e-shopping transactions, monetary value, and product evaluation cost is the main concern for customers and online vendors since they are critical factors to determine customer purchase decisions in different settings [4,5,6], and reuse intentions [7,8,9].

With the expansion of online shopping purchasing behavior, customers need to adapt to the e-shopping environment to increase shopping value, and perceived effectiveness of institutional protection increases customer enjoyment and success in online transactions [10,11]. Due to increase fraud in internet shopping [10,11], PEEIM and trust in online vendors have become an important factors for online customers to protects customer from uncertainty risk in online transactions. Previous studied has shown that the moderating effects of PEEIM between trust and intention to repurchase intention is low when the influence of trust and repurchase intention is low. To address uncovering previous study, this study propose direct and indirect influence of PEEIM on customer to purchase and reuse intentions and understanding the influence of monetary value, product evaluation cost, customer enjoyment on trust in online vendors, and their impact on customer purchase intention and intention to reuse the products are critical factors that determine success in e-shopping purchase behavior and retention of existing customers. Draw from the combination of PEEIM and trust in online vendor and conceptualize as e-shopping institutional–trust-based mechanism (EI-TBM).

The present study addresses the following research questions: (1) How do monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment influence the customer purchase intention and intention to reuse the products or service in an e-shopping environment? (2) Are PEEIM and trust in online vendors effective institutional mechanisms to mitigate uncertainty in the e-shopping environment?

Previous studies have shown that trust supports customer purchase intention [12]. Furthermore, customer trust not only affects online purchase behavior but also general trust in online shopping [13]. This study suggests that the positive effect of trust on repurchase intention is higher when the interacting PEEIM relationship between satisfaction and trust is low [10].

We extend the empirical study of [10] to further investigate the influence of trust in online vendors in relation to PEEIM, monetary value, product evaluation cost, customer enjoyment, and their impact on customer intention to purchase and reuse online vendors. Second, to understand the indirect effects of customer shopping value (monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment), and indirect influence of PEEIM on trust online vendor and customer intention to purchase and reuse the products and service in the e-shopping environment. It drowns from a combination of PEEIM and trust.

We conceptualize PEEIM and trust as the e-shopping institutional–trust-based mechanism (EI-TBM). We define EI-TBM as: safeguards exist in the e-shopping environment to protect customers before and after the transaction by independent and interdependent risk mitigation, which benefits both parties. We argue that independence and interdependence mechanisms not only to provide customer protection from a general perspective but also provide specific protection for online shopping. For example, home-payment, it is considering a specific institutional protection since the customers purchase the product on an e-shopping environment, but payment is made when the products reach their home. Home-payment is characterized as “low-risk-taker customer behavior relationship”. Moreover, from the general institutional perspective, the customer have independence relationships with the vendors and the payment provide through the third parties (e.g., credit cards, or convenience stores). This type of customer behavior is characterized as “high-risk-taker customer behavior relationship”. In addition, by introducing monetary value, product evaluation cost, customer enjoyment, and PEEIM as antecedents of trust, the study provides different research model and hope to provide difference research finding from existing studies [10]. Furthermore, PEEIM not only direct and indirect influences customer trust in online vendors but also direct and indirect influences customer purchase intention and intention to reuse the products and services.

First, this study contributes not only to the theoretical literature on customer intention to purchase and reuse online vendors, but also to the long-term sustainability of the e-commerce the institutional, by conceptualize PEEIM and trust online vendor as an e-shopping institutional–trust-based mechanism (EI-TBM), which provides finding different from the existing studies [10,14,15].

Second, this study contributes the role of trust in online vendors as the mediator, and the influence of PEEIM on customer enjoyment, and direct and indirect on customer purchase intention, and customer reuse intention. Third, by examining product monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment factors as antecedents of trust the study provides findings different from previous studies [10].

2. Theoretical and Literature Review

2.1. E-Shopping Institutional Trust-Based Mechanism

The e-shopping institutional trust-based mechanism has been studied over many years, originated with [14], and developed later on to include perceived effectiveness of e-commerce institutional mechanisms [8,13,14]. Those mechanisms act as impersonal structures implemented by third parties to create conditions under which customers feel protected when making an online transactions [10,15]. Institutional mechanism instruments include online credit card guarantees, escrow services, and privacy protection [13,15,16]. Similar studies on financial institutional online shopping find that guarantees provide resources and help customer compensate for the uncertainty and potential risk of online transactions [15,16]. For instance, an online vendor can provide financial instruments such as Pay Pal or ATM that have the authority to make payments after the customer has decided to purchase the products. However, we argue that with the financial institutional instruments provided by third parties, distrust between buyer and vendor may arise [17,18]. Similarly, others studies have tried to divide the first two institutional trust-based mechanisms into specific and general beliefs to mitigate risk in online shopping [19].

The distinction between trust-specific beliefs and trust as a general belief has been studied primarily in the context of interpersonal relationships within an organization [10,20]. However, with ongoing economic transformations in the e-shopping environment, this distinction is seldom maintained, especially in e-commerce research. Accordingly, this study extends the empirical [10] study and investigation the study based on a combination of two institutional mechanisms (perceived effectiveness e-commerce institutional mechanisms (PEEIM) and trust-based mechanism) to be appropriate for the present customer purchase behavior in e-shopping environments. Two of these institutional mechanisms (customer trust online vendor and PEEIM), we conceptualize as e-shopping institutional–trust-based mechanism (EI-TBM). EI-TBM implements trust from general and specific perspectives as an advanced institutional mechanism to mitigate risks through independent and interdependent relationships.

Thus, institutional structure is not only strengthens customer intention to purchase and reuse the products or services but also increases long-term sustainability to protect customers in an e-shopping environment. Our model in this study shows that customer trust in online vendors is play important rule between the customer perceives shopping value such as monetary value, customer enjoyment, and product evaluation cost, and customer intention to purchase and to reuse the products or services. Furthermore, PEEIM helps ensure customers enjoy their shopping and thus supports continued intention to purchase and reuse products or service in e-shopping environments.

Interdependence, as an interpersonal relationship, exists when customer and vendor have a specific relationship, such as “home-payment” or “text messenger”, after the transaction takes place. Home-payment is characterized as “low-risk-taker customer behavior”, where customers feel safe to purchase or to pay for the product when the order is delivered to their home. The independent relationship exists when customer and vendor engage in market block-building expansion without doubting the trust relationship between them. We refer to this as customer trust from a general perspective, where customers accept the financial instrument provided by third parties, such as PayPal, Ibon, Visa, and online ATM without uncertainty about financial repercussions. Customer willingness to make the transaction and pay for the product after the transactions, before delivery, we characterize as “high-risk-taker customer behavior”. By developing the concept of an institutional mechanism as EI-TBM, the customer may feel safer in the overall e-shopping environment. That distinguishes this study from previous research [10,15,21].

2.2. Distinguishing, EI-TBM from PEEIM and Related Concepts

The difference between PEEIM and related concepts, including trust from the perspectives of both specific and general institutional mechanisms, has been explained previously by concepts such as institutional structures and structural assurance [15]. Second, PEEIM focuses more on the effect of mitigating risks through a third party, from a general institutional perception [10]. This study considers that when e-commerce institutional mechanisms mitigate risk from general perception, online customers may expect a more interpersonal quality to this mechanism. Therefore, they will expect reduced risk from this mechanism.

EI-TBM is an institutional instrument that combines customer trust in an online vendor and the perceived effectiveness of e-commerce institutional mechanisms. These institutional mechanisms implementing trust from general and specific perspectives to accommodate advanced institutional mechanisms that mitigate risks through independent and interdependent relationships. For example, to reduce customer doubt regarding value in an e-shopping environment, an online vendor can provide protection by providing “home-payment” which is an interdependent relationship with the customer. Home-payment interprets customer relationship with the vendor in a specific way and uses a financial instrument providing by the vendor. However, from a general perspective, this is a financial instrument provided by third parties. We call this an independent relationship, where the customer, online vendor and third parties have an institutional trust relationship. Independence indicates that customers, vendor, and third parties cannot be separated from market expansion (block building) in the e-shopping environment. Thus, distinguishing the PEEIM and EI-TBM developed in this way, we are investigating the influence of trust in an online vendor and the PEEIM relationship between monetary value, product evaluation, and customer enjoyment on one hand, and customer intention to purchase and reuse the product or service in the e-shopping environment on the other hand. Furthermore, this occurs due to relatively strong risk-mitigation through customer relationships from general and specific perspectives, which provides findings different from the existing literature [10].

3. Research Model and Hypotheses Development

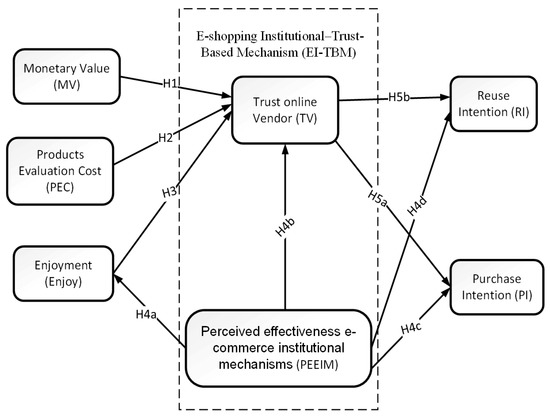

Based on the combination of PEEIM and trust-based mechanism, this study considers how monetary value product evaluation cost and customer enjoyment together influence customer purchase intention or willingness intention to reuse the products or service in an e-shopping environment. Second, the influence of PEEIM on customer enjoyment, trust online vendor, purchase intention and customer intention to reuse the vendor the products or services. Third, the influence of trust in an online vendor on purchase intention and customer continuance intention to reuse the vendor. Last, we introduce constructs that mediate the relationship of trust in online vendors and customer enjoyment. For more detail, please refer to the following hypothesis and research models in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The institutional-trust based model.

3.1. Monetary Value and Trust in an Online Vendor

Previous work has found that products are key to determining customer purchase decisions in different settings [1,7]. Trust is a sense of security, where customers feel confident their transactions will succeed [22]. The theory of mental accounting explains the relationship between monetary value and customer trust by stating that acquisition utility influences a consumer’s choice [7]. Thus, acquisition utility in our study is equivalent to monetary value, considered as an e-shopping benefit with respect to its price of the product or service. In our model, the monetary value indicates that customers perceive the shopping value based on the level of customer trust in the online vendor, and we considering monetary value as customer profit. For example, the function of a consumer notebook application as the expected to the price the customer paid. Accordingly, we propose:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

Product monetary value has a positive relationship to trust in an online vendor.

3.2. Product Evaluation Cost and Trust in an Online Vendor

Previous research suggests that in complex environments, consumers are often unable to effectively evaluate all of the alternatives available prior to choosing [23]. Instead, they tend to use a two-stage process to reach their decisions, including product screening, and product evaluation [23]. In the product screening stage, consumers screen a large set of relevant products, without examining any of them in great depth, and identifying the most promising alternatives, Subsequently, during product evaluation, the consumer evaluates a set of alternatives in more depth, compares products for important attributes, and then makes a purchase decision [24].

Our model states that product evaluation cost is based on the probability of customer trust [25]. Customers may reduce evaluation costs when the online vendor can reduce the product uncertainty of their reference price [22]. Previous studies have stated that transaction utility refers to the customer perceiving the shopping value based on customer trust relationship. For instance, product uncertainty can be reduced by reducing product evaluation costs such as the actual price and reference price [7]. This enables the vendor to reduce the customer’s processing time and thus lower product evaluation cost, which will increases customer trust in the e-shopping environment. Accordingly, we purpose:

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

Product evaluation cost has a positive relationship with trust in the online vendor.

3.3. Customer Enjoyment and Customer Trust of Online Vendors

Enjoyment can be defined as a stage of customer flow while shopping in a digital marketplace. That enjoyment regard to customer satisfies with the value of the products or the services in the e-shopping environment [7]. Previous studies have shown that customers purchase the mobile application drive according to the value application [3]. Other studies state that increasing the value of information and function from a mobile application increases customer purchase intention to use the products [6,7]. Customers also perceive benefit from digital shopping with increased trust in the particular market [2]. We define enjoyment as the state and degree of the customer’s contentment regarding the value of the products or services that affect activities before and after the transaction takes place in an e-shopping environment. Contentment (enjoyment) can increase customer trust in an online vendor. Our model shows that enjoyment influences customer trust in the products or service in an online shopping environment. We expect that customer enjoyment can drive the value of trust and reduce uncertainty in the online shopping environment. This can increase customer purchase decisions in the digital market, leading to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

Customer enjoyment increases trust in an online vendor.

3.4. PEEIM and Enjoyment, Trust, Customer Intention to Purchase and Reuse a Vendor

Perceived effective e-commerce institutional mechanism develops from trust related to customer purchasing behavior, and those mechanisms create conditions where customers feel protected when making online transactions [10,15]. Institutional trust is also conceptualized as the intuitional distance in the context of the organization [26]. The development of those institutional mechanisms strengthens the interpersonal relationships or inter-organization relationships. From that point of view, our model states that PEEIM not only influences trust in an online vendor, intention to purchase, and reuse the products or services, but also influences customer enjoyment that can be limited by uncertain situations in the digital market environment. This study expects that increasing perceived effective e-commerce institutional mechanisms for customer enjoyment and strengthening trust in the online vendor; thus, the intention to purchase and reuse the vendor enhances a long-term successful and sustainable development of the digital market. Accordingly, we propose:

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

PEEIM has a positive relationship on (a) Customer enjoyment, (b) trust in an online vendor (c) purchase intention, and (d) intention to reuse the vendor’s products or services.

3.5. Trust Online Vendor and Customer Intention Purchase

From a customer purchase behavioral perspective, product loyalty can be characterized as reuse intention [7]. Thus, reuse intention can be defined as the consumer performing a transaction over the internet based on customer loyalty to the brand or vendor [9]. In other hand on the purchase intention situation, it is likely for customers to perform a transaction that has completed the initial transaction with the online vendor at first-hand experience [7]. Our model indicates that trust often is an outcome of customers’ ability to meet one set of obligations [20]. The notion of trust is to help reduce the sense of risk when dealing with an uncertain situation regarding products or services in a digital transaction. it also to encourages customers’ “trust-building customer behavior relationship” with online vendors [20]. Thus, trust has been supported [10]. Based on that theoretical viewpoint, we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

Trust in online vendors has a relationship with purchase intention.

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

Trust in an online vendor has a relationship with customer reuse intention.

3.6. Mediatings Effect of Trust in an Online Vendor

In the digital shopping environment, customers’ trust represents their beliefs about the online vendor, and these beliefs enhance the consumers’ attitude toward repurchase intention [27]. Monetary value is an important factor to determining customer purchasing decisions [7]. A customer considering purchasing a product is likely to assess the product’s value and buy it if the product’s values match the customer’s expectations, and product evaluation cost positively mediates reuse intention [8]. Customer enjoyment is one of the main impacts on customer purchase behavior [28,29].

Our model shows that monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment have a relationship with the intention to purchase and to reuse the products or services as influenced by trust in the online vendor. Trust in online vendors has a mediating role to protect customers by lowering product evaluation costs and increasing monetary value in online transactions. However, customer enjoyment would increase the intention to purchase and reuse products or services depends on customer trust in the online vendor. Accordingly, the current study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 6 (H6).

Trust in an online vendor mediates the relationship between monetary value and (a) intention to purchase, and (b) the intention to reuse products or services from the vendor.

Hypothesis 7 (H7).

Trust in an online vendor mediates the relationship between product evaluation cost and (a) intention to purchase and (b) intention to reuse the products or services in the digital market.

Hypothesis 8 (H8).

Trust in an online vendor mediates the relationship between customer enjoyment and (a) intention to purchase and (b) intention to reuse products or services in the digital market.

3.7. Mediating Effects of Customer Enjoyment and Trust Online Vendor

Customer enjoyment can be considered from various perspectives, such as customer interaction with a stranger in an e-shopping environment for relaxation. Enjoyment can be defined the degree of internal flow that customers when searching for information and perceived shopping value [28]. A perceived effective e-commerce institutional mechanism provides and ensures that customers experience success and enjoy shopping in an e-shopping environment. The influence of trust has a positive relationship with customer purchase intention [15], where trust in an online vendor has no mediating effects between PEEIM and repurchase intention [10]. With a low-level indirect influence between PEEIM and customer intention to purchase from trusted online vendors, consumers may have less trust in their intention to purchase and to reuse the products or services. However, this study further investigates the mediator of customer trust online vendor and customer enjoyment, where PEEIM is a factor with indirect influence on customer intention to purchase and to reuse through customer enjoyment and customer trust in the online vendor. Furthermore, a low-level indirect influence between PEEIM and customer intention to purchase and reuse the products or services in the e-shopping environment may reduce customers’ enjoyment and trust in the online vendors, which may decrease the intention to purchase the products or services. Accordingly, this study proposes:

Hypothesis 9a (H9a).

Customer enjoyment mediates the relationship between PEEIM and trust in an online vendor.

Hypothesis 9b (H9b).

Customer enjoyment and trust in an online vendor mediates the relationship between PEEIM and (b1) customer intention to purchase (b2) customer intention to reuse products or services from the vendor.

Hypothesis 10 (H10).

Trust online vender mediates the relationship between PEEIM and (a) customer purchase intention, (b) intention to reuse the products or service in the digital market environment.

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Setting and Participants

The research study used a questionnaire to test the proposed model with 293 participants who made online purchases (e.g., Amazon, PC-Home, MomoShop, or other online vendors) in Taiwan. These platforms are considered the most reputable e-shopping platforms, which can increase customer trust [30]. These websites also keep customers updated on current practices and thereby increase customer trust by conveying fair treatment [31]. The structure of the website and customer service on Amazon, PC-Home, MomoShop, and other website shopping are deriving for all practical purposes. For example, they offer financial instrument guarantees (e.g., Visa card, Line point, and ATM, 7-11 ibon, and arrival-home payment), and offer similar feedback mechanisms.

The questionnaire targeted digital shoppers including students, government workers, and company employees with experience purchasing from a digital vendor in Taiwan (e.g., Amazon, PC-Home, MomoShop, and Alibaba). The products they purchased are for personal or family use only. To minimize bias of the questionnaire distribution, the respondents were contacted by e-mail, Facebook chat or Line chat, and group lunch in the restaurant. The questionnaire items were translated from English to Chinese. A total 437 questionnaires were distributed by random sampling to individuals with experience in digital shopping from 1–30 June 2018. The final response rate analysis was 67% (n = 293 of the total response) and the unusable responses were due to missing or incomplete survey information.

4.2. Measurement Instrument

Most of the constructs in this study were adapted from prior literature see (Appendix A). Wording was modified to fit the research context [32], and all measures used a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from ‘‘1—strongly disagree’’ to ‘‘7—strongly agree’’. To measurement trust in an online vendor, we used four items that reflected consumer beliefs, honesty, dependability, reliability, and trustworthiness in the e-shopping environment [10,15]. PEEIM was measured by four items from previous research [10] to capture the perceived effectiveness of financial service instruments to ensure customer safety in online transactions. Monetary value (MV) adapted five items [7] and with five items measured PEC [8]. Five items were adopted to measure customer enjoyment [7,33], and four items were taken for further data analysis. Five items were adopted to measure customer repurchase intention [34], and four items were taken for further data analysis. Four items to measurement customer purchase intention adopted [9]. Thus, we developed our measurement instruments and followed common advice on wording the questions [32]. Two Ph.D. students management department and one professor from information system management as the expert to validated the content of the questionnaire before to finalize the questionnaires for further study.

Most respondents used digital shopping for their daily personal use products, and 65.5% were female and 34.5% were male. Participants were mostly from the age groups of less or equal to 25 years old and more than equal to 65 years old. In total, 42.7% of the participants mostly student, followed by businessman 28.0%, work in industries 16.4%, and 13.0% work as civil officers. For education, 72.7% of the participants mostly had university education, followed by 13.7% with graduate education, and 13.7% from senior high school. The largest monthly income bracket was 40.3% with US$200–800, followed by 35.5% with $801–1000, 17.7% with $1001–2000, and 6.5% with over $2001. The participants searched for information and shopped using a smartphone 77.5% of the time and a PC 22.5% of the time. They used PC Home (27.0%), MomoShop (16.7%), Amazon (15.4%), Alibaba (11.3%), and other popular shopping platforms (29.7%). The questionnaire asked questions related to general and specific perceptions for general internet experience and transactions, finding that 57.0% had 3 years or less of internet experience. In addition, 52.9% had 3 years or less of e-shopping experience. The validity of data samples were sufficient to identify the customers’ behavior and to accommodate further study the influence of institutional trust-basic mechanism on the digital market. We employed IBM SPSS 20 for descriptive analysis to assess the frequency and the percent range of the population, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics.

4.3. Data Analysis Technique

The research models were tested using partial least squares (Smart-PLS 3.0) for the following reasons. First, as with the structural equation model (SEM), this technique estimates the loadings, weights, construct validity, and reliability among construct relationships in multiple stages [35]. Second, PLS is suitable for models with relatively small samples [36]. Third, the bootstrap procedure [37] can test the significance of various results such as path coefficients, T-value, p-value, Cronbach’s alpha, and R2 values. The model was assessed using bootstrap statistics with 5000 re-samples and a total of 293 cases per sample [37]. Fourth, confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to determine the loadings, discriminant validity, and internal consistency of the internal model. Fifth, to test the mediating relationship we followed a previous approach [38,39].

5. Results

Measurement Model Validity and Reliabilities

First, we assessed the construct validity and reliabilities, including monetary value, product evaluation cost, enjoyment, trust online vendor, PEEIM, customer intention to purchase, and customer intention to repurchase the products or services in the e-shopping environment. Convergent validity can be established by examining standardized path loading items, composite reliability (CR), Cronbach’s alpha, and the average variance extracted (AVE). Discriminate validity determined the square root of AVE should be greater the internal constructs correlation [40]. Second, in Table 2 the composite reliability values are greater than 0.8, Cronbach’s alpha values are greater than 0.7, and the AVE ranges from 0.53 to 0.65, indicating an acceptable value [40]. Furthermore, to evaluate discriminant validity shown in Table 3, represent the diagonal the roots of AVE. The result of cross-factor loading confirms the presence of discriminate validity, as shown in Appendix B.

Table 2.

Construct Reliability and Validity measurement model.

Table 3.

Discriminant validity.

Third, variance inflation factor (VIF) values for all of the constructs ranged from 1.27–2.22, the consistencies standard error on the measures path loadings with the t-value were between 12.57 and 48.20, and p-value at the level of all supported [41], as shown in Table 4. Sufficient validity of this model indicates an effective measurement model in this study.

Table 4.

Weights and loadings.

6. Structure Model

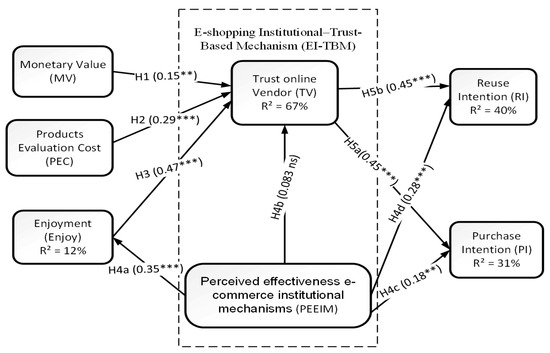

Figure 2 shows the results of structural model analysis, Table 5 summarizes the hypothesis results. First, to test the hypotheses we use the Smart-PLS algorithm, and then perform a complete bootstrapping setting with 5000 subsamples, with a two-tailed test to determine the significance of the hypothesized model relationship. The path of the model confidence and validity presented indicates that the model is valid, except that H4b is not supported, though other hypotheses in the model are supported. Monetary value, products evaluation costs and customer enjoyment have positive relationships with trust of an online vendor, supporting H1–3, H1: (β = 0.15, t = 2.96 ** p < 0.01), H2: (β = 0.29, t = 5.35 *** p < 0.001), H3: (β = 0.47, t = 8.38 *** p < 0.001). PEEIM has no significant influence on trust of online vendors, but there is an opposite finding the relationship of PEEIM on customer enjoyment, purchase intention, and intention to reuse the products or services. These do not support H4b: (β = 0.008, t = 1.56 p < 0.05), and do support H4a,c,d, H4a: (β = 0.35, t = 5.24 *** p < 0.001), H4c: (β = 0.18, t = 2.88 ** p < 0.01), H4d: (β = 0.28, t = 4.62 *** p < 0.001). Trust in online vendors has a positive relationship on customers purchase intention and intention to reuse the products or services in the e-shopping environment, which supports H5a,b, H5a: (β = 0.45, t = 7.23 *** p < 0.001), H5b: (β = 0.45, t = 7.80 *** p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

The result Institutional–Trust Mechanism. Notes: ** p < 0.01 = t > 2.58; *** p < 0.001 = t < 3.29); with one-tailed test.

Table 5.

Construct relationships and hypotheses.

Second, the R-square values for all of these factors taken together PEEIM was significant explain of the variance in customer enjoyment (R2 = 12%), PEEIM and customer enjoyment explain the majority of customer trust in online vendors (R2 = 67%), PEEIM and customer trust in online vendors explains the majority variance of customer purchase intention (R2 = 31%), and where PEEIM and trust in online vendors explains the majority variance of intention reuse intention (R2 = 40%) toward the products or services in the e-shopping environment.

7. Mediating Effects

To test the mediating effects, a bootstrapping procedure was used to ensure that the model had the mediating effects, as recommended for testing the mediating model in the smart-PLS context [42,43]. Table 6 summarizes mediating effects and hypotheses testing, showing no mediating effects except for H10a and H10, so the other hypotheses are all supported. The result of the hypothesis explains that trust in an online vendor significantly mediates the relationship between monetary value, product evaluation, customer enjoyment, and customer intention to purchase and reuse the product or service. This supports H6a to H8b. H6a: (β = 0.07, t = 2.85 ** p < 0.01), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.12%. H6b: (β = 0.07, t = 2.99 ** p < 0.01), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.12%. H7a: (β = 0.13, t = 4.17 *** p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.20%. H7b: (β = 0.13, t = 4.33 *** p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.19%. H8a: (β = 0.21, t = 5.10 *** p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.29%.and H8b: (β = 0.21, t = 5.12 *** p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.29%. Customer enjoyment significantly mediates the relationship between PEEIM and trust in an online vendor, H9a: (β = 0.16, t = 4.67 *** p < 0.001), and upper confidence interval limit size of 0.23%.

Table 6.

Mediating effects and hypotheses.

Furthermore, PEEIM has a mediating effect on customer intention to purchase and repurchase products or services in the e-shopping environment through the continuance influence of customer enjoyment and customer trust in an online vendor, with support the H9b1 and H9b2. H9b1: (β = 0.07, t = 3.66 *** p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size is 0.12%. H9b2: (β = 0.07, t = 3.59 ***, p < 0.001), and the upper confidence interval limit size is 0.12%. In contrast, customer trust in an online vendor does not significantly mediate the relationship between PEEM and customer intention to purchase and reuse products or services in the e-shopping environment, which does not support H10a,b. H10a: (β = 0.04, t = 1.52, p < 0.5), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.09%. H10b: (β = 0.04, t = 1.52, p < 0.05) with the confidence intervals distance value shown nearly minus zero percent (−0.01%), and the upper confidence interval limit size 0.09%.

The study conclude that the results of mediating relationships of customer trust in online vendors has the higher influential relationship between enjoyment and customer intention to purchase and to reuse intention with the upper confidence intervals distance 0.29% and with the lower confidence intervals distance 0.13%. In contrast with the mediating effects of customer trust in online vendor relationship between PEEIM and customer intention to purchase and to reuse the products or services in the e-shopping environment has a higher confidence intervals distance 0.09% and the lower confidence intervals distance nearly minus zero percent (−0.01%).

8. Implications and Conclusions

8.1. Theoretical Implications

First, based on the combination of trust and PEEIM the study investigates the influence of customer shopping value and PEEIM on customer trust and intention to purchase and to reuse products or services in the e-shopping environment. The antecedent factors of customer trust in online vendor has two dimension: shopping value (monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment), and PEEIM. The consequence factors of customer trust online vendor consist of customer intention to purchase and reuse products or services in the e-shopping environment. The study contributes with an important new theoretical design for e-commerce research [44], and also contributes with findings different from previous studies, as outlined below.

Customers shopping value such as monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment have positive and significant relationships on customer trust of an online vendor, and indirect positive and significant relationship on customer intention to purchase and reuse the vendor products or services through the influence of customer trust in an online vendor, supporting H1–3 and H6a–H8b. Furthermore, PEEIM has positive and significant effects on customer enjoyment, customer intention to purchase, and to reuse products or services in the digital e-shopping environment, supporting H4a,c,d. However, PEEIM has no direct effect on customer trust in an online vendor, which does not support H4b. However, PEEIM has indirect positive and significant effects on trust in an online vendor through the influence of customer enjoyment, which support H9a. The results also show that PEEIM has two constantly indirect positive and significant effects on customer intention to purchase and to reuse the vendor through the influence of customer enjoyment and customer trust online vendor, which supports H9b1,2. All together these findings advance our understanding of the influence of customer shopping value and PEEIM on customer trust in an online vendor, and customer intention to purchase, and reuse the products or services in the e-shopping environment, which supports customer decision-making behavior in an e-shopping environment [7,8], and customers intention to purchase and repurchase [9,10]. Furthermore, the results extend existing predictions [10] in the following sections.

Prior research examines the role of institutional-trust-based mechanisms in the context of an online purchasing [10,15,21,45,46], the results confirm that the effects of PEEIM is higher relationship between customer satisfaction and customer trust in an online vendor though PEEIM has no moderating effects between trust and customer repurchase intention in e-commerce [10]. This study extends previous empirical work by examining customer trust online in vendors and customer enjoyment as a mediator factor, based on theoretical of PEEIM and trust in online vendor and we conceptualized as EI-TBM. The results support most of the hypotheses (Table 5 and Table 6, and Figure 2).

Last, demographics show that 41% of the respondents are 25 years old and 65.5% are female, indicating that the participants especially females are a prime target to shop in the e-shopping environment. In addition, 42.7% of the participants are students, and 28% are business service officers are considering as low-risk-taking customers’ behavior. At least 52.9% of the participants have e-shopping experience and 40.3% of the participants have monthly incomes between US$200 and 800. Furthermore, 77.5% of the participants do online shopping with a smartphone. The study confirms that customers are more mature with the e-shopping activities using advanced technology such as smartphones, and low-income participants can afford e-shopping activities.

8.2. Practical Implications

There are several implications for retailers, vendors, management, and public policymakers. First, this study recommends that online vendors and third party financial providers should more specifically allocate their trust-building customer behavior to enhance long-term sustainability on customer intention to purchase and reuse the product or services in the e-shopping environment. The vendor should maintain e-shopping website such as PC Home and MomoShop that provide various types of customer services up to the date, such as home-payments and third-party financial instrument services.

Second, vendors should develop customer trust through institutional e-commerce mechanisms; for instance, advanced financial services and privacy protection services through EI-TBM (interdependent relationship) such as home-payment. Furthermore, online vendors should focus on customizing websites to make it easier for customers to contact vendors; for example, low-risk-takers (elderly aged people) are one of often to reflect on the vendor services. This positive influence of customer trust and perceived effective e-commerce institutional mechanisms on intention to purchase and reuse products and services generates customer loyalty and thereby builds long-term sustainability of the e-shopping institutional trust-based mechanism.

Third, online policymakers and managers is to not only requiring more advanced services regarding product information, real-reference prices, minimize promotion prices, and more concern to provide protection to the customer such as low customer e-shopping experience, low monthly income, low internet experience, and the young generation.

8.3. Limitations and Future Research

The current study contributes to the in e-shopping institutional mechanism, customer decision process, and customer trust-building literature, as follows: First, our sample size is small relative to our model design. However, according to our observation data evidence enough to support our study. In the future, studies should have a more advanced research design and larger sample size that enable to provide a better finding. Second, by simple questioning (e.g., spit of these two factors: e-shopping experiences, and internet experience as the moderating effects), which can provide more advance funding in future, more the detail regarding the questionnaires refer to Appendix A.

Third, our data was collected in Taiwan, which is considered to have a set of cultural similarities. In the future, research could expand cross-country to provide parsimonious finding with a more comprehensive survey design to improve the research finding by considering replicating the study with alternative methods, such as grouping customer experiences.

9. Conclusions

This study extends previous literature and develops a model combining PEEIM and customer trust online vendor, which originated from the trust-based mechanism in the contact of e-commerce environment [15,46]. We conceptualized PEEIM and trust online vendor as e-shopping institutional trust-based mechanism (EI-TBM), extending the findings from existing studies [8,13,14,22]. Our findings confirm that MV, PEC, and customer enjoyment has a positive and significantly relationship with customer trust in online vendors and an indirect relationship with customer intention to purchase and reuse products or services in the e-shopping environment. However, PEEIM has no relationship with trust in online vendors, though it has high direct effects on customer enjoyment, and customer intention to purchase and reuse products and services in the e-shopping environment, in contrast to previous findings [10]. The finding also shows that PEEIM does have an indirect relationship with customer intention to purchase and reuse products or services through influence of customer enjoyment and trust online vendor. Thus, findings is not only address trust-building customer behavior and risk-mitigation mechanism but also enhance long-term sustainability on the customer purchase behavior in the e-shopping environment.

Second, these study illustrate the paradoxical role the theoretical of EI-TBM, extending the existing literature [10], which provides findings that are more advanced by considering the key role of PEEIM (i.e., direct and indirect effects of PEEIM on research design). Future research can further explore research study related to EI-TBM in different contexts.

Last, the demographics show that younger people, especially female participants, became a target to access the e-shopping activities with the advanced technology such as smartphones. The study concludes that based on present theoretical background, research design and the research findings, the study not only contributes to parsimonious theoretical literature outcome of EI-TBM and shopping value (monetary value, product evaluation cost, and customer enjoyment), but also enhances the long term sustainability of the customer intention to purchase and reuse the products or service the e-shopping environment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.W.M. and S.-C.C.; methodology, S.-C.C. and A.R.; formal analysis, N.W.M.; investigation, N.W.M.; resources, A.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.W.M. and S.-C.C.; writing—review and editing, N.W.M., S.-C.C. and A.R.; visualization, A.R.; supervision, S.-C.C. and A.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for this study on human participants 302 in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent from the patients/participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Survey Items

| Demographic (N = 293) Respondents Participating the Study | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Gender | 1□Female | 2□Male | ||||||||||

| 2 | Age | 1□below 25 | 2□26–30 | 3□31–35 | 4□36–40 | 5□40 above | |||||||

| 3 | Occupation | 1□Student | 2□Business | 3□Industry | 4□Civil servant | ||||||||

| 4 | Education | 1□Senior high school | 2□University | 3□Graduate above | |||||||||

| 5 | Monthly Income | 1□Less than 200–800$ | 2□801–1000$ | 3□1001–2000$ | 4□More than 2001 | ||||||||

| 7 | E-Shopping website | 1□Alibaba | 2□Amazon | 3□MomoShop | 4□PC Home | 5□Others | |||||||

| 8 | Internet Experience | 1□≥3 years | 2□<3 years | ||||||||||

| 9 | E-Shopping experiences | 1□≥3 years | 2□<3 years | ||||||||||

| 10 | Instrument | 1□PC | 2□Smart phone | ||||||||||

| Please fill the option 1–7 from strongly disagree to strongly agree, when you are shopping on the internet. A vendor could either be a company that produces or provides the product or service (e.g., Alibaba, PC home, and others), (1. Strongly disagree 2. Disagree 3. Somewhat disagree 4. Neutral 5. Somewhat agree 6. Agree 7. Strongly agree) | |||||||||||||

| Monetary Value [7] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | MV1The product is a good value for money. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | MV2 At the price shown, the product is economical. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | MV3 The product has a good performance. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | MV4 The product is a good value for time. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 5 | MV5 The product is real produce. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| Product Evaluation Cost [7,8] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | PEC1 It was very easy for me to make this purchase decision. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | PEC2 I had no difficulty deciding which item would be best for me. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | PEC3 Making this purchase decision was easy for me. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | PEC4 I had no difficulty deciding which products are of value to me. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 5 | PEC5 The product prices make sense with the items. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| Trust in Online Vendor [8,15,22,46] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | TV1 I believe that this vendor is keen on fulfilling my needs and wants. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | TV2 I believe that this vendor is honest. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | TV3 I believe that this vendor is trustworthy. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | TV4 I believe that this vendor has high integrity. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| Perceived the Effectiveness of E-commerce Institutional Mechanisms (PEEIM) [10,15] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | PEEIM1 When buying online, I am confident that there are mechanisms in place to protect me against potential risks. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | PEEIM2 I have confidence in third parties. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | PEEM3 I am sure that I cannot be taken advantage by the vendor. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | PEEM4 I believe that there are other parties who have an obligation to protect me against potential risks. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 5 | PEEIM5 This vendor always protects me. | ||||||||||||

| Intention to Reuse [34] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | IR1 I would consider reusing the vendor within one month. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | IR2 I would consider reusing the vendor within 2 months. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | IR3 I am willing to reuse product/service within 2 Months. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | IR4 The likelihood of my to reuse product/service within 2 Months is high. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 5 | IR5 There is a high probability that I will consider reusing the vendor within the next 3 months. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| Purchase Intention [9] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | IP1 There is a high probability that I will consider buying a product within a month. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | IP2 There is a high probability that I will consider buying a product within the next 3 months. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | IP3 I am very willing to buy a product within the next 3 months. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | IP4 Likelihood of my purchasing a product within the next 3 months is high. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| Enjoyment [7,33] | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Enjoy1 I feel in shopping in the digital market is enjoying. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 2 | Enjoy2 I find that digital shopping after tiring working is pleasant. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 3 | Enjoy3 I find very fun while shopping in digital market. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 4 | Enjoy4 I felt relaxed doing digital shopping. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

| 5 | Enjoy5 I feel shopping is interesting. | 1□□ □□ □ □□7 | |||||||||||

Appendix B. Cross Loadings

| Construct Items | Enjoy | IP | IR | MV | PEC | PEEIM | TV |

| Enjoy1 | 0.79 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.50 | 0.27 | 0.61 |

| Enjoy2 | 0.78 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.37 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.64 |

| Enjoy3 | 0.80 | 0.51 | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.44 | 0.22 | 0.50 |

| Enjoy4 | 0.85 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.60 |

| Monetary value1 | 0.40 | 0.37 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| Monetary value2 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.23 | 0.48 | 0.32 |

| Monetary value3 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.31 |

| Monetary value4 | 0.31 | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.32 | 0.45 | 0.32 |

| Monetary value5 | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.47 |

| PEEIM1 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.30 | 0.73 | 0.27 |

| PEEIM2 | 0.26 | 0.34 | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.75 | 0.32 |

| PEEIM3 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.40 | 0.83 | 0.45 |

| PEEIM4 | 0.28 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.75 | 0.45 |

| Product Evaluation Cost1 | 0.39 | 0.31 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.78 | 0.31 | 0.56 |

| Product Evaluation Cost2 | 0.47 | 0.35 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.54 |

| Product Evaluation Cost3 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.33 | 0.45 | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.46 |

| Product Evaluation Cost4 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.37 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.51 |

| Product Evaluation Cost5 | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.66 | 0.36 | 0.47 |

| Purchase intention1 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.30 | 0.38 |

| Purchase intention2 | 0.49 | 0.84 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| Purchase intention3 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.46 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.36 |

| Purchase intention4 | 0.46 | 0.79 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.38 |

| Reuse Intention1 | 0.49 | 0.44 | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Reuse Intention2 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.34 | 0.43 | 0.50 |

| Reuse Intention3 | 0.44 | 0.53 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.45 |

| Reuse Intention4 | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 0.36 | 0.38 | 0.42 |

| Trust evendor1 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.32 | 0.72 |

| Trust evendor2 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.69 |

| Trust evendor3 | 0.60 | 0.51 | 0.45 | 0.53 | 0.60 | 0.44 | 0.80 |

| Trust evendor4 | 0.64 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.33 | 0.81 |

References

- Baishya, K.; Samalia, H.V. Extending unified theory of acceptance and use of technology with perceived monetary value for smartphone adoption at the bottom of the pyramid. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 51, 102036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds-McIlnay, R.; Morrin, M. Increasing Shopper Trust in Retailer Technological Interfaces via Auditory Confirmation. J. Retail. 2019, 95, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Galliers, R.D.; Shin, N.; Ryoo, J.-H.; Kim, J. Factors influencing Internet shopping value and customer repurchase intention. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisstein, F.L.; Kukar-Kinney, M.; Monroe, K.B. Determinants of consumers’ response to pay-what-you-want pricing strategy on the Internet. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4313–4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Factors Influencing Internet Shopping Value and Customer Repurchase Intention. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1567422312000270 (accessed on 24 December 2020).

- Kim, H.-W.; Kankanhalli, A.; Lee, H.-L. Investigating decision factors in mobile application purchase: A mixed-methods approach. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 727–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Agarwal, R.; Lucas, H.C., Jr. The value of IT-enabled retailer learning: Personalized product recommendations and customer store loyalty in electronic markets. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 859–881. [Google Scholar]

- Benlian, A.; Titah, R.; Hess, T. Differential Effects of Provider Recommendations and Consumer Reviews in E-Commerce Transactions: An Experimental Study. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 237–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Qureshi, I.; Sun, H.; McCole, P.; Ramsey, E.; Lim, K.H. Trust, Satisfaction, and Online Repurchase Intention: The Moderating Role of Perceived Effectiveness of E-Commerce Institutional Mechanisms. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 407–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemons, E.K.; Wilson, J.; Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Ren, F.; Jin, F.; Koh, N.S. Global differences in online shopping behavior: Understanding factors leading to trust. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 1117–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbous, A.; Aoun Barakat, K.; Merhej Sayegh, M. Social Commerce Success: Antecedents of Purchase Intention and the Mediating Role of Trust. J. Internet Commer. 2020, 19, 262–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, N.; Nguyen, T. The effect of trust on consumers’ online purchase intention: An integration of TAM and TPB. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2019, 9, 1451–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.P. The social control of impersonal trust. Am. J. Sociol. 1987, 93, 623–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; Gefen, D. Building Effective Online Marketplaces with Institution-Based Trust. Inf. Syst. Res. 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharthey, B. The Role of Online Trust in Forming Online Shopping Intentions. Int. J. Online Market. (IJOM) 2020, 10, 32–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.-K.; Ramsey, E.; McCole, P.; Chen, H. Repurchase intention in B2C e-commerce—A relationship quality perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.D.; Lowry, P.B.; Galletta, D.F. It’s complicated: Explaining the relationship between trust, distrust, and ambivalence in online transaction relationships using polynomial regression analysis and response surface analysis. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Benbasat, I. Empirical assessment of alternative designs for enhancing different types of trusting beliefs in online recommendation agents. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2016, 33, 744–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthuysen, K.; Teunis, I.; Reusen, E.; Slabbinck, H. Initial trust and intentions to buy: The effect of vendor-specific guarantees, customer reviews and the role of online shopping experience☆. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 27, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An Examination of the Nature of Trust in Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 62, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-W.; Xu, Y.; Gupta, S. Which is more important in Internet shopping, perceived price or trust? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.C.; Tseng, Y.-D. Quality evaluation of product reviews using an information quality framework. Decis. Support Syst. 2011, 50, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, L.; Gupta, S. The role of online product recommendations on customer decision making and loyalty in social shopping communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 150–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, K.L.; Lin, J.C.C.; Wang, X.Y.; Lu, H.P.; Yu, H. Antecedents and consequences of trust in online product recommendations. Online Inf. Rev. 2010, 34, 935–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.C.; Fang, Y.; Straub, D.W. The impact of institutional distance on the joint performance of collaborating firms: The role of adaptive interorganizational systems. Inf. Syst. Res. 2017, 28, 309–331.28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghazi, P.; Karlsson, S.; Hellström, D.; Hjort, K. Online purchase return policy leniency and purchase decision: Mediating role of consumer trust. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 41, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, S.; Tata, S.V.; Parsad, C.; Banerjee, A.; Sahakari, N.; Chatterjee, S. Clustering E-Shoppers on the Basis of Shopping Values and Web Characteristics. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. (JGIM) 2019, 27, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Ye, Q. Understanding consumers’ loyalty to an online outshopping platform: The role of social capital and perceived value. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, R.; Wilcox, H.D.; Grover, V. The role of system trust in business-to-consumer transactions. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2003, 20, 197–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, D.L.; Novak, T.P.; Peralta, M. Building consumer trust online. Commun. ACM 1999, 42, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.K.; Wieman, C.E. Development and validation of instruments to measure learning of expert-like thinking. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2011, 33, 1289–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveena, K.; Thomas, S. Continuance intention to use Facebook: A study of perceived enjoyment and TAM. Bonfring Int. J. Ind. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2014, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.C. The influence of social presence on customer intention to reuse online recommender systems: The roles of personalization and product type. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2011, 16, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-T.; Bagozzi, R.P. Contribution Behavior in Virtual Community: Cognitive, Emotional and Social Influences. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Hollingsworth, C.L.; Randolph, A.B.; Chong, A.Y.L. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P. Construct measurement and validation procedures in MIS and behavioral research: Integrating new and existing techniques. MIS Q. 2011, 35, 293–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Smith, D.; Reams, R.; Hair, J.F., Jr. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): A useful tool for family business researchers. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrión, G.C.; Nitzl, C.; Roldán, J.L. Mediation Analyses in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Guidelines and Empirical Examples. In Partial Least Squares Path Modeling; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-T.; Wang, Y.-S.; Liu, E.-R. The stickiness intention of group-buying websites: The integration of the commitment–trust theory and e-commerce success model. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Choudhury, V.; Kacmar, C. The impact of initial consumer trust on intentions to transact with a web site: A trust building model. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A. Institution-based trust in inter-organizational exchange relationships: The role of online B2B marketplaces on trust formation. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2002, 11, 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).