Abstract

Sustainable development is promoted when the system of education provides the learners with an opportunity to equip themselves with moral values, skills, and competences that assist them in effecting personal and community positive changes. For this purpose, teachers play an important role as moral agents, and students consider the teacher a role model. Therefore, the understanding and beliefs of teachers regarding moral education play a pivotal role in grooming the personality of the learners. This comparative study aimed to assess the practices and beliefs of university teachers regarding moral education in China and Pakistan. A mixed-method approach was used and data analysis was performed by using an interactive model and ANOVA. Responses of twelve tertiary teachers were collected from Pakistan and China for qualitative analysis. Seven themes were constructed that categorized teachers’ practice in the classroom and their beliefs regarding moral education. For quantitative analysis, 300 teachers’ responses were collected using a validated questionnaire. The results showed that the majority of Pakistani teachers hold a conservative mindset. According to the Pakistani teachers’ perspective, sovereignty of divine laws, loyalty to the constitution of the state, and a sense of serving society were the ultimate aims of moral education. Chinese teachers were promoting a political ideology that stressed collectivism in a socialist approach, with family and social values being most relevant. Not a single teacher reported using a theoretical or research-based approach while teaching in the class. In the light of the dearth of literature, this study has implications for future research in the field of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) and Islamic Studies in higher education, as it is a longitudinal study that provided insight into how teachers’ beliefs and attitudes are shaped over time and from moral educational experiences.

1. Introduction

Education is complete when it leads to the individual’s entire growth, which includes not only mental but also moral development [1]. Moral education is fundamentally needed in contemporary times, as rapid degeneration of moral values has been witnessed [2]. The aim of moral education for sustainability is to inspire, propel, and equip the learners with adequate skills, awareness, and values, so that a sustainable future can be produced [3]. It was mentioned in the report of United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) that communities today are gradually losing traditional ethics and values. The report also showed concerns about the increasing number of disputes arising in the global contexts, where the disputants refuse to try to resolve the disagreements through peaceful means. Therefore, the purpose of education in the current scenario, inculcating peace and harmony among countries, has become very critical [4]. The role of moral education and the teacher as a moral agent becomes imperative in transforming society with a more sustainable way of living. To this end, the developing of deeper awareness and analytical skills is crucial in making moral decisions with every day exertions. As far as the goals of moral education are concerned, most teachers are not trained and are confused about what moral education is. The teacher plays a key role in developing the values of the students. However, in inculcating such values, the teacher’s views and her/his practice of teaching have a significant impact on the entire process. The teacher’s opinions, guidelines, decisions, and choices of methodology are influenced by his/her beliefs directly or indirectly.

Diversity of opinion was also found among teachers’ approaches towards moral values and obligation. Regarding the beliefs and actions of the teacher, CM Clark and Peterson; Ignatovich, Cusick, and Ray; and Olson [5,6,7] concluded that teachers impart and imply their inherent theories concerning their part, position, and duties, including their teaching behavior, into the classroom settings. A competent teacher is usually encapsulated as a blend of skills such as knowledge, values, and competence [8,9]. Many studies have been conducted to assess teachers’ perceptions about their skills, ability, and knowledge [10], but they did not include values in such studies. However, there is a strong consensus found in educational literature that values play an integral part in teaching morals in the classroom [11].

Every nation in the world has formulated its moral standards and codes in a unique manner [12]. In Pakistan, the foundations of moral education are based on state religion, which includes Islamic values, history, and traditions. The sustainable development in Islamic ideology is to fulfill all human needs in all generations, including a man’s duties, to himself, his fellow human beings, and God [13]. The primary goal of morality is to enable students to conduct their lives according to the morals that Islamic literature preaches [14], which are usually referred as Islamiyat, ethics, or Islamic Studies. Pakistan’s National Education Policy 1998–2010 official document, stressed the importance of inculcating religious and ethical education in to the classroom [15]. In this deem, the role of the teacher is to use various strategies in the classroom to instill religious and moral values into the students. However, the educational system severely lacks the availability of skilled and trained teachers, planning and implementation of training programs, research projects, and curriculum of moral education [14].

In China, the concept of moral education mainly emphasizes the education of citizenship [16]. Moral education is regarded in a wider context as a political philosophy that relates to the transmission of political ideas to the students and the general public at large. The ideological principles are established upon the theories of Marx, Lenin, Mao, and Deng Xiaoping. Chinese students are expected to internalize the cores of this moral education, which is political science focused at the university level [17]. Other courses play a significant role than political ones in shaping the morality of the students [18], such as the course of English as a Foreign Language (EFL). English language class has recently been recognized as the bearer of moral education [19,20]. Therefore, the role of Chinese teachers is to translate moral knowledge to action and equip the students with real life problem-solving skills. However, the awareness among teachers regarding moral education is very low; their major focus is transmitting subject knowledge, rendering moral values absent from the classroom [18].

While research has attempted in recent years to comprehend the role of China and Pakistan on the Asian stage [21,22,23], very few bodies of research have been conducted in the field of moral education and its integration with EFL and Islamic studies to achieve the goal of sustainability. Moreover, studies on moral development and value formation were found from the western perspective, while very few studies were carried out on the perspectives of the east. Eastern societies and their moral education systems face real moral issues such as depression, poor quality education systems, personality disorders, lack of moral awareness, and weak moral will [24]. In this regard, the findings of the previous studies could be rebutted or reaffirmed and the current scenario of teaching values, morals, or ethics in Pakistan and China could be assessed for bringing reforms in the subject of EFL and Islamic Studies.

This study aimed to bridge the existing gap of teachers’ effective role towards sustainable moral education with the comparison of classroom teaching and the views of the university teachers to explore the heterogeneity among the teachers from two different countries. For this purpose, classroom observations and interviews were conducted. EFL classrooms were selected for observation from China. The reason for selecting EFL classrooms was first due to the language barrier, as the researcher was not a Chinese native speaker. Second, educators and experts of linguistics have expanded their interest beyond the acquisition of language and linguistic capability to concentrate on the moral dimension of language instruction [19,20,25,26]. Balciunaitiene et al. [27] contended that the students examined specific topics, addressed concerns, and shared the personal experiences and emotions of sustainable development in the foreign language class. EFL develops basic communication skills with an emphasis on developing competence in sustainability. It has been mentioned above, that according to the education system of Pakistan, the sustainable development in Islamic ideology is to fulfil all human needs in all generations, including man’s duties to himself, his fellow human beings, and God [13], which is why Islamic Studies classrooms were observed in Pakistan.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: background, traditional and constructive approach, and concepts of moral education in Pakistan and China are described in Section 2. Materials and methods, the purpose of the study, research design, and participants’ profiles are presented in Section 3. Results, analysis of classroom observation, interviews and ANOVA are described in Section 4. Discussion on results is presented in Section 5. Finally, the conclusion of the research is given in Section 6.

2. Background

2.1. Traditional and Constructivist Approaches to Moral Education

The two most widely discussed approaches in the literature regarding moral education are usually opposite to each other [28,29], named traditional [30] and constructivist approaches [31]. The traditional approach stresses the utilization of reward and punishment [30]. It emphasizes the transmission of moral values from older to younger or generation to generation through moral education, character, or value education [32]. The purpose of the traditional approach is to teach the students in a way that they could use to adopt a good character and values, obey the law of the state, and become role models for others. The values, such as honesty, hard work, kindness, patriotism, and sense of responsibility, are important to become a morally strong person [33]. The traditional approach mainly relies on conservative strategies, due to which some contemporary models of moral education are based on the constructivist, or progressive, approach.

In contrast, the constructivist, or progressive, view was promoted by Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg [31]. The term moral education has been strongly associated with this approach. The objective of moral education according to this approach was to develop cognition in children and adolescents in an educational environment. Kohlberg described six levels of cognitive moral development in his theory, which was the sequenced development of a sense of fairness and justice. This approach depends on moral reasoning, moral judgment, participation in solving different problems, and decision making [31,34,35].

2.2. Concept of Moral Education in Pakistan and China

Shafiqua Haq [14] described how moral education in Pakistan mainly builds upon the teachings of religion, and societal and cultural norms. The responsibility of the teacher is to encourage the pupils to understand and adopt the morality for the well-being of themselves, society, and the world at large. The moral education system in Pakistan emphasizes the teachings of the Quran, which holds wisdom for the people of all times, with no demand of blind following; rather the encouragement of inquiry, rationality, observation, and intellectuality through experimentation and exploration. The Holy Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) is a role model and source of inspiration for Muslims, his teachings, in the form of Hadith and Sunnah, are another source of moral education in Pakistan. The interpretations of the Quran and Sunnah by Muslim philosophers like Imam Ghazali and Imam Saadi are also considered a source of moral education in Pakistan. They accentuated the searching of knowledge for the development of a good human being. All the educational policies of Pakistan described the term moral education in the light of Islamic teachings, which is to promote the obedience of law and loyalty towards Islam and Pakistan.

There are two goals of moral education in China. The first is to fulfill the social needs of the students by the application of concepts such as patriotism and encouragement to serve the country, the people, and the society at large. The second goal of moral education is to address the needs of the students for their personality development and prosperity. Hu [36] revealed in his research that in China, socialist values, such as family unity, harmony, prosperity, and honesty, are considered important while teaching in the classroom. Due to political autarchy, government schools, colleges, and universities also promote political ideology. At university level, the moral education curriculum stresses Marxism, Mao Zedong ideology, and Deng Xiaoping theory. Students are taught traditional Chinese values such as self-sacrifice, patriotism, collectivism, honesty, and loyalty.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study was to compare the beliefs and the role of the teachers regarding the aim of moral education for sustainability in China and Pakistan. The study raised three questions concerning the views of teachers and the practice of teaching morals in the classroom. It was important to explore the answers of these questions to solve the societal and ethical issues such as globalization, moral judgment, character education, and citizens’ participation. There are few instances that have opened the door of discussion on ethical decline that has not only affected the moral values in present times but also hampered the sustainable growth of morality. In Pakistan, the most recent incident took place when lawyers attacked a hospital [37], whereas in China, a company was accused of selling substandard, risky, and dangerous immunizations to vaccinate over a quarter of a million children [38]. Therefore, teachers’ perceptions and beliefs about the aim of moral education and the areas that are necessary to be learnt by the students are significant because teachers play a vital role in the moral development of the students. Additionally, this research may contribute to the global, and particularly Asian, literature on university teachers’ professionalism in terms of moral transformers. It is also lucrative for political leaders, policymakers, higher education institutions, curriculum developers, and educators to formulate better plans and curriculum reforms to understand the ideas and patterns of teachers’ practices in the classroom to improve the moral education system in China and Pakistan. According to the purpose, the following research questions were explored:

- What is the concept of moral education and what do teachers think about their practices of moral education for sustainable development?

- What values teachers consider necessary to teach and what methods they usually apply to teach moral education for sustainable development?

- What do the teachers consider as the basis for their choices to select the methods in teaching moral education for sustainable development?

3.2. Research Hypotheses

Based on the theoretical design of the study, a set of hypotheses was formulated to examine through empirical data, as follows:

Hypothesis 1.

There is no significant difference between the perception of Pakistani and Chinese teachers regarding the concept of moral education for sustainability.

Hypothesis 2.

There is no significant difference between the methods that Pakistani and Chinese teachers use in the classroom for sustainable development.

3.3. Research Design

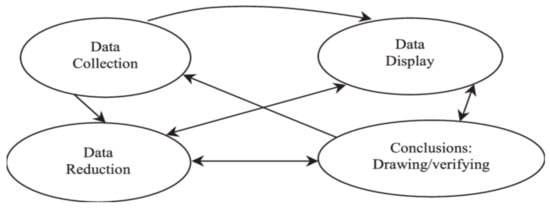

This study adopted a mixed-method approach to draw conclusions. The qualitative analysis of the study used Miles, Huberman, and Saldana’s interactive model, mentioned in Figure 1. This model was used in numerous studies to conduct a qualitative data analysis [39]. It attempts to provide a systemic, rigorous, and accountable framework for qualitative inquiry. It consists of four components, beginning from data collection and concluding by drawing results. According to the model, after the collection of data, the data are reduced to make them simplified by noting down important information related to the research problem. In the next stage, data are presented in the form of tables and graphs, and in the end, conclusions are drawn. This model was suitable for the study as it specified the rich information collected by class observations and interviews.

Figure 1.

Interactive Model: Component of Analysis. Source: Qualitative Data Analysis by Miles et al. [40].

Twelve teachers of EFL and Islamic Studies were selected for classroom observation and interviews. An unstructured observation tool and interview questionnaire was developed. The duration of each class observation was 80 min, during which, teaching practices of these teachers were closely examined and their classroom practices were noted down. The duration of interview of each participant was 15 to 25 min. Classroom observation and interviews were conducted by the researcher personally. The interviews were audio-recorded. Data were coded line by line by using an interactive research model. Themes and concepts were developed to draw conclusions.

The quantitative analysis of the study was performed using one-way ANOVA and t-test. The data for analysis were gathered using a questionnaire (Appendix A). Five percent of the sample was selected for pilot testing and the reliability of the questionnaire was tested through SPSS version 20. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated, which was r = 0.81. For validation, the opinion of the experts of EFL and Islamic Studies were taken. Initially, 23 items were developed, but after experts’ feedback, 4 items were omitted. The questionnaire was distributed among 150 Chinese and 150 Pakistani teachers. However, the total amount of responses received was 239. According to the literature, there are the following kinds of t-test available: (1) single t-test, (2) independent t-test, and (3) paired t-test.

Since the information in this research was acquired from two independent groups, the independent t-test was selected for this study. One-way ANOVA was an add-on of the t-test, which differentiated the sample means of the groups and depicted whether or not the numbers of groups differ numerically across the groups. The present article used ANOVA, which compared the moral education existence and methodology between Chinese and Pakistani teachers.

3.4. Participants’ Profile

In the present study, tertiary teachers were selected as a sample from two countries China and Pakistan. For a quantitative analysis, 300 teachers from both countries were selected, while for qualitative analysis, the unstructured interviews were conducted from 12 teachers. The teachers were randomly selected from the population of 40 teachers who were teaching at Shanghai University, China and International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan. The Pakistani sample consisted of 6 teachers (3 males and 3 females). The teachers were teaching the Islamic Studies subject to undergraduate students in International Islamic University in Islamabad, Pakistan. The Chinese sample consisted of 6 teachers (3 males and 3 females) from Shanghai University. Teachers from the faculty of EFL were selected with the following considerations:

- The common teaching language between Pakistan and China is English. In Pakistan, all subjects are taught in English, whereas in China only faculty of English has English language competency. Therefore, the faculty of EFL was the only option for selection of participants.

- Chinese universities have well-defined criteria for induction of their faculty according to age, qualification, and experience. Therefore, these factors have already been embedded in teachers’ selection.

The respondents’ profile was developed in Table 1, due to the confidentiality of data, the researcher assigned numbers to participants

Table 1.

Respondents’ Profile.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of Observations and Interviews

In the presentation of results, the researcher focused on themes that were based on classroom observations and interviews. The results showed that teachers from both countries used traditional methods to teach morals in the classroom. They did not consult the theoretical basis and empirical research to enhance their teaching skills. Moreover, they were found to be confused in their views when asked about the aim of moral education, what methods they used, and what basis they had in selecting methods for teaching morals for sustainable development.

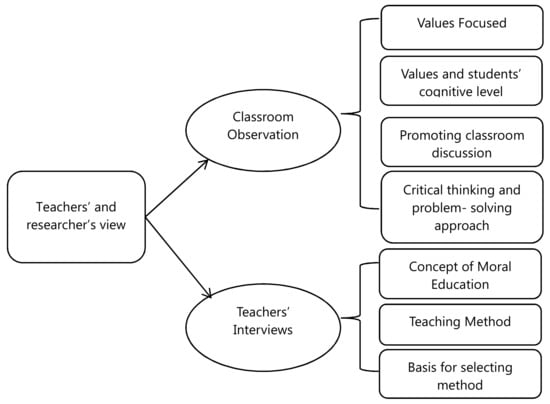

The researcher used an interactive model to collect data from university teachers and divided them into seven themes based on the objectives of the study. The themes are presented in Figure 2. These themes were also considered in developing the survey questionnaire (Appendix A). The first four dominant themes were observed during class observation, while three themes were focused on when teachers were interviewed. The researcher personally checked the adequacy of the themes to ensure internal validity with the assistance of experts in the field of EFL and Islamic Studies, who reviewed them to avoid the researcher’s bias and improved the reliability of the themes [40].

Figure 2.

Themes of Observation and Interview.

4.2. Classroom Observation Analysis

Classroom observation is often used to assess the standard of teaching [41] and teaching–learning process, including classroom procedures, teaching practices, methodology, strategy, and teacher–student relationship [42,43]. It is one of the considerable teacher assessment techniques because it provides abundant information about the actual classroom performance of the teachers, which can later be used for summative and formative assessment [44,45]. In this section, four themes related to classroom observation were discussed in detail. The notes were taken when teachers were teaching in the classroom and their practices of teaching moral education were analyzed critically by the observer.

4.2.1. Values Focused

In China, a variety of topics were discussed in the classroom that could be justified as it was an EFL classroom. The values that assimilated with lessons were sympathy, responsibility, unity, success, courtesy, self-esteem, rationale, logics, victory, achievement, patriotism, leadership, harmony, and peace. During the lecture, teachers stressed on cultural and political values, while universal values were less identified. Here is an example of one of the classroom lectures delivered by the male participant:

- Teacher:

- Today we will discuss the Rhetorical Perspective on Human Action. A basic concept of identity will be discussed how a man should be? A man, who must share the knowledge, a man with good morals, friendly with others, shows sympathy and intelligence. In this regard, three appeals will be thoroughly learnt. The first is the appeal to ethos; second, the appeal to pathos and the last one is the appeal to logos (then used the board and drew a triangle to explain three appeals). Ethos or the ethical appeal means to convince others by your personality and character (linked it with a good moral human) whereas pathos or the emotional appeal means to convince people by appealing their emotions (gave the example of sympathy and empathy). Try to feel the emotions of people and the appeal to logos mean persuade others by using logics (linked it with unity and gave the example of birds that fly in a flock).

In Pakistan, most of the teachers were promoting religious values and emphasis was placed on the cultivation of spiritual life. According to the teachers, Islam was the religion that promoted peace instead of violence. The values identified during observations were peace, charity, equality, honesty, sacrifice, devotion, patience, rationality, wisdom, modesty, obedience, mercy, and pious. Here is an example of one of the female teachers:

- Teacher:

- Today the topic we are going to discuss in the class is “The System of Morality in Islam” (wrote the topic on the board). There are three major categories of men: (1) the one who is good by nature, (2) those who are incorrigible, (3) those who come between both categories 1 and 2 are called intermediary groups. Most of the humans are laid under the third category, the other 2 categories are considered extreme categories and very few individuals are found. The very first category humans are like angels and they don’t require any direction to do good actions. They follow the principles of God Almighty, believe in sacrifice, devotion, charity and have a good soul by birth. The second category needs great attention and they must be controlled by doing evil. They are extremists by nature and ready to harm themselves as well as others. The third category is large in number and they required all time direction to prevent evil and do good actions.

Further, she presented examples of different souls, like a noble soul, intelligent soul, ordinary spirit, and obtuse soul. Thus, the part that was focused on was becoming a good human being who offers sacrifices and devotion to help other members of society.

4.2.2. Values and Students’ Cognitive Level

Most of the values were embedded appropriately within lectures in China and Pakistan. Chinese teachers’ stress was on success, achievement, patriotism, unity, and leadership that supported their cultural and political ideology. Pakistani teachers focused on spirituality, sacrifice, and obedience of divine laws. As the university students were prepared to step in practical life, these moral values were quite suitable to their cognitive level. However, some valuable moral traits were neglected too in their teachings, such as honesty, care, fairness, and respect for others in China, while in Pakistan they were the sense of responsibility, attaining knowledge, use of logic, and leadership.

4.2.3. Promoting Classroom Discussion

In Pakistani classrooms, most of the teaching methodology was the lecture method, in which teachers were reading and explaining text. No use of multimedia was observed in the classroom. Students were just passive listeners. Although a few students gave their routine presentations in the classroom, which indicated their good confidence level, open classroom discussion was lacking. In China, teachers promoted discussions and group work. However, the discussions were mostly focused on recalling the content instead of multidimensional ideas. Generally students were found to be hesitant in sharing their opinion. Most of the boys were less interested in the lecture and were playing games on laptops or mobile phones. Female students were somehow participating and sharing their views, but were not articulate due to the language barrier. All the teachers were using the lecture method and multimedia in the classroom, and planned their lesson by keeping a few minutes at the end for a question–answer session. The following is the extract of a discussion on the justification of war.

- Teacher:

- Give the reason to justify war?

Another question asked by the teacher was:

- Teacher:

- Are terrorists the justification of war for America? Give your opinion.

The teacher also showed a slide on multimedia and asked for the comments. The slide had these lines:

There is a scene in the TV series “Operation Iron Eagle”: the “Knife” of the railway criminal police and the female college students pursuing him take a walk in the middle of the rail to say goodbye. The rail behind them crisscrosses. The scene is very beautiful, but it seriously violates the railway safety regulations. Because walking or walking in the middle of the railway track is easy to be knocked down by the train coming from behind. Do the railway criminal police have such a common sense?(Six Jianxiang, Xinmin Evening News, 4 August 2000)

4.2.4. Critical Thinking and Problem-Solving Approach

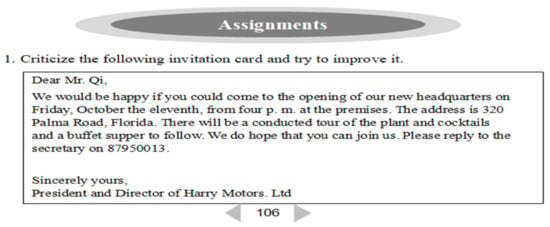

It was observed during evaluation in China that critical thinking and problem-based activities were part of the EFL textbook, while there was no activity found related to critical thinking and the problem-solving approach in the textbooks of Islamic Studies. Therefore, it was seen in China that students were involved in solving assignments. Here is the example of the activity conducted during one of the classroom observations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Image from an EFL Textbook.

- Teacher:

- Open page number 106 of your book. There is an assignment, make a group of 4 students and discuss it with each other. Each group will present the improved version of the invitation card in front of the class. I am giving you 10 min to complete this activity. Your time starts now.

Students improved the invitation card in the assigned groups and the teacher was a facilitator. In Pakistan, there was no culture of critical thinking and problem-based learning approaches in the classroom. Teachers were using a traditional approach of delivering a lecture with recapping at the end. They gave topics for upcoming lectures to be prepared by the students at home and a few students were selected for classroom presentations, which was the only activity in the lesson plan.

During classroom observation, Chinese teachers were found better comparatively, as they were more equipped, more organized and well-prepared, and their qualification level was higher than Pakistani teachers, but it was observed in both countries that teachers were promoting their political and religious ideologies. China, being a communist country, was promoting socialist values in the classroom, while in Pakistan, Islamic values were focused on more in teaching morality.

4.3. Interview Analysis

4.3.1. Concept of Moral Education

In both countries, Pakistan and China, teachers reported that moral education is complex in nature. It generally refers to the moral values and conduct of society. It helps students to socialize from the early phase of life. It supports developing a character that obeys the law and has courage, loyalty, honesty, and a kind heart towards others. Mostly, teachers described the concept of morality as the transmission of relational values, values related to others, how to treat others in respect of being kind and humble, showing empathy, and treating others in the same way as you want to be treated.

Another view, according to the teachers, was to help students to understand the meaning of life and one’s mission and purpose. According to the female teachers of Pakistan and China, stress has been given to love, respect, empathy, and tolerance. A female teacher reported “I think emotions play an important role when we discuss morality. Showing kindness, love, sympathy and respect were most identified moral values for me”.

Another important concept of morality according to the teachers was to teach the students about the concept of self-responsibility, for example, taking the responsibility of actions, being organized and creating self-awareness. Male teachers reported in these words: “for me, moral education teaches students to be responsible. It helps in creating the courage to take responsibility for their actions and how to behave in different situations and with different people.”

Among Chinese and Pakistani teachers, the vital aim of moral education was to socialize the students with other members of the school, community, society, and the world at large. Moral education supports an adaptation of appropriate behavior that obeys the law, self-responsibility, treats everyone equally, and creates patriotism and peace in society instead of violence. Most of the Pakistani teachers stressed on religious education, according to them, moral education meant to develop a personality who obeys God and His principles and makes the students spiritual beings.

It was perceived by the responses of the teachers that relational values, self-awareness, and self-responsibility were a functional, as well as a narrow, view of teaching moral education. It provides awareness about how the societal norms, their responsibilities, and showing good behavior are actually to maintain the law, peace, and harmony in society.

- Interviewer:

- What do you think about moral education?

- Chinese Teacher:

- China is a socialist country and emphasis is always given on collectivism so I think family and community values are most important when we talk about moral education. Creating unity and harmony in society is extremely important.

- Pakistani Teacher:

- I think the most important about moral education is to teach pupils to behave appropriately according to the rule of God Almighty as He wanted to see His people pious, devotional, and sympathetic for others. Moreover, it helps students to behave adequately as you should behave as a part of school and society.

- Interviewer:

- What do you mean by behaving appropriately as you should behave? Can you elaborate?

- Pakistani Teacher:

- Sure, we have hundreds of rules around us such as rules to behave in a school, religious principles and societal norms, and conducts. Students need to behave accordingly. They have to learn these rules to create equilibrium in their personality as we humans are biological and spiritual beings. If they don’t obey the rule it would simply harm others as well as collapse the structure of the society.

- (From an interview with a Pakistani and Chinese male teacher)

On the contrary, a few Chinese and Pakistani teachers also stressed on developing psychological strength within the pupil that could be defined as self-enhancing moral character. Teachers talked about assisting pupils in building positive self-esteem and self-confidence. According to a few Pakistani teachers, democratic participation was also described as an integral part of moral education. Democratic participation includes decision making, freedom of the individual, critical discourse, and the problem-solving approach. Last but not the least, a few Chinese teachers reported patriotism as an important value in moral education, to love the country, fostering nationalism and unity.

4.3.2. Application of Teaching Methods in the Classroom While Teaching Morals

According to most Pakistani and Chinese teachers, the important method to teaching morals is becoming a role model for the students, as students always get inspired by the character of the teacher. The students try to adopt the behavior of the teachers. According to a Pakistani female teacher, “teachers need to show tolerance and good character in the class to inspire their students; they do not use offensive language while instructing the pupils, show equality towards students, and listen to them carefully”. Additionally, some of the Pakistani and Chinese teachers admitted that their teaching of moral education mostly or partly depended on their unconscious, as they did so many things unconsciously that are not planned or followed by the curriculum.

The teachers from both countries described their views that their practice of moral education could not remain static and planned. They had to change and modify it according to the environment of the classroom. Teachers had to react to counter the behavior of the students daily, which sometimes included bullying, peer harassment, group conflicts, and disruptive character. Teachers had to talk about how to behave adequately instead of showing violence and bad behavior.

Moreover, Chinese teachers reported that teachers were generally considered moral agents because they needed to become role models for effective learning. Moral education appeared to be integrated with classroom management that supports maintaining institutions and classroom principles to develop the appropriate behavior of students. One of the Chinese teachers shared his view on moral education in these words:

- Interviewer:

- Would you like to share your views about teaching moral education in the classroom?

- Chinese Teacher:

- Teaching moral education is the necessity of the current time. Teachers have to be like leaders who give vision to the students. They need to be confident and clear in their views about moral education and act as a role model. They have to be distinguished from others to conquer the heart and minds of the students and become an inspiration for them. If I talk about me as a teacher so I am clear in my views and instruction. I react where I feel I have to respond to mold the behavior of disruptive children. Eventually, it depends on the situation and classroom settings where they have to confront it.

In other words, it might be called a reactive approach, as identified by a few Chinese teachers who stressed on proactive teaching strategies. Chinese and Pakistani teachers discussed the examples of reactive and proactive moral education, for example, working with principles. At the beginning of the new class, the teacher needed to create a democratic environment and lead the students by inspiring them with their prosocial behavior: “As a teacher I allow my students to assess themselves and their peers in a free and friendly environment so they may easily accept their mistakes and correct them. Pakistani male teacher reported that I allow my students to freely discuss their ideas, with no hesitation in asking questions, and critically analyze the situation before taking any decision.”

However, Pakistani and Chinese teachers reported rarely, on specific occasions, delivering moral education into the classroom, like showing movies, acting role-plays, focal group discussion based on the topic of current affairs, and discussing moral dilemmas in the classroom. According to the views of a Chinese male teacher, moral dilemmas were an affective technique and valuable method because they developed critical thinking and problem-solving skills in the students. It was easy to distinguish what was right and what was wrong, but the most difficult task occurred when one had to pick one more beneficial or less harmful option from two positives and two negatives, respectively. In the same way, group discussions provide an opportunity for the students to develop skills in raising arguments, listening to other’s points of view patiently, and creating a democratic mindset.

A Pakistani male teacher responded that the class council system in the modern education system was becoming the source of developing democratic values that were related to moral education. However, this type of belief and ideology of teachers was found to be uncommon in the interview responses. Moreover, Chinese teachers associated moral education to particular subjects, such as ideological and political education, sociology, and languages.

4.3.3. Basis for Selecting Methods for Teaching Moral Education

Both Pakistani and Chinese teachers responded that they used their general ideas when they described moral education. Some teachers even found themselves confused and had difficulty verbalizing their teaching during the interview. Females were found more ambiguous as compared to male teachers. A Pakistani female teacher said that “I think it is difficult to describe I usually explain what I feel will be effective, mostly I talk about those moral values that I feel more important for students to learn and then I start to talk about it and take the views of the students too”. In response to questions about teaching pupils the appropriate moral values, both Pakistani and Chinese teachers responded that their personal experiences, parents, and teachers’ instruction in their childhood were important in selecting teaching material, instead of specific curriculum guidelines. The curriculum was not much explicit in guiding what moral values were important to teach into the classroom. Moral education was not offered as a separate course. However moral values were embedded with other disciplines in both countries. Another set of data reported that they used common sense while selecting the method for teaching moral values. It was asked what they meant by common sense, the response was to take wise decisions followed by social conduct and norms.

- Interviewer:

- What do you mean by common sense?

- Chinese Teacher:

- Sometimes we consider common sense as a feeling or inner voice that guides you what is wrong or what is right, you must not take this way or like stop here and don’t go further it would harm you or I should not discuss with my friend she/he will feel sad.

- (An interview with a Chinese female teacher)

Most of the teachers from Pakistan and China were the followers of political, religious, cultural, and societal customs. They were transferring the moral values that they acquired from their parents, religion, political affiliations, and society. However, the researcher didn’t find a single case that reported that he/she used a theoretical basis or research while selecting a method for teaching morals in the classroom. They even didn’t consult any psychological research that could benefit them in their teaching. Almost every teacher had his unwritten principles and dogmas, which were based on their own experiences.

4.4. Quantitative Analysis

This section discusses the quantitative part of the research. The data for this analysis were obtained through the questionnaire (Appendix A), which was divided into seven sections. The first two sections (i—Values Focused, and ii—Values and Students’ Cognitive Level) were concerned with Hypothesis 1. Whereas the remaining five sections (iii—Promoting Classroom Discussion, iv—Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Approach, v—Concept of Moral Education, vi—Application of Teaching Methods in the Classroom during Teaching Morals, and vii—Basis for Selecting Method for Teaching Moral Education) were related to Hypothesis 2. The t-test was used for hypothesis validation. Afterward, one-way ANOVA was used for analysis to determine statistically significant differences between groups of Pakistani male teachers and Pakistani female teachers, and Chinese male teachers and Chinese female teachers

4.4.1. Hypotheses Validation

The hypotheses validation was performed using independent t-tests. Hypothesis 1 was validated using the teachers’ responses for the first two sections. Table 2 shows the responses collected for Hypothesis 1. The table shows that 34% of participants generally agreed over a neutral response; the equal majority agreed with the statement. However, only 3.67% of the respondents were not in favor of the statement. The mean of the table (3.51) provides support to the statement.

Table 2.

Response of Hypothesis 1.

To test Hypothesis 1, an independent t-test was conducted, which figured out if there were disagreements between groups regarding the similar concept of moral education in China and Pakistan. The result of the independent t-test indicated that there was no significant difference found between groups (95% CI, −0.37980 to 0.00927, t (237) = −1.773 p = 0.060). The results are mentioned in Appendix B. Hence, the null hypothesis was accepted and the alternative was rejected, showing the concepts of moral education of Pakistani and Chinese teachers are similar.

Hypothesis 2 was validated using the teachers’ responses for the last five sections. Table 3 shows the response collected for Hypothesis 2. The table shows that 28.67% of participants generally agreed over a neutral response; while 46.34% agreed to the statement. However, only 4.66% of the respondents were not in favor of the statement. The mean of the table (3.82) provides support to the statement.

Table 3.

Response of Hypothesis 2.

To test Hypothesis 2, an independent t-test was conducted to check disagreements between groups in similar teaching methods of teachers in China and Pakistan. The result of the independent t-test indicated that there was no significant difference found between groups (95% CI, −0.40113 to 0.00831, t (237) = −1.881 p = 0.060), and results are listed in Appendix B. Hence, the null hypothesis was accepted and the alternative was rejected, showing the concept of teaching methods for Pakistani and Chinese teachers are similar.

4.4.2. One-Way ANOVA Analysis

This section states details about an analysis that statistically deduced significant differences between groups—differences between Pakistani male teachers, Pakistani female teachers, Chinese male teachers, and Chinese female teachers are presented. For testing hypotheses, the variables for the questionnaire were determined by ANOVA. Table 4 shows the one-way ANOVA analysis. The variables were grouped into seven sections, detail of which has already been described in Section 4.4. The results show an interesting phenomenon i.e., the p values for each of the sections were found to be absolute 0.000, which is lesser than the usual percentile of 0.05, which shows there is a statistically significant difference between means of groups. When we closely examined another important factor mean square, it was found that mean square between the groups for two sections “Values and Students’ Cognitive Level” and “Promoting Classroom Discussion” was comparatively less than mean squares of other sections. Further, mean squares of the rest of the sections were surprisingly close. This clearly shows that aforementioned sections have less priority as compared to the rest of sections. In addition, participants emphasized the rest of the sections. In short, the calculated mean result showed significant differences among all groups, so it can be concluded that the mean scores of both groups were not the same.

Table 4.

One-way ANOVA analysis.

5. Discussion

5.1. Concept and Practice of Moral Education

According to the first question of the study, the concept of moral education according to the teachers of EFL and Islamic Studies was to socialize the students, to teach them the purpose of life, and to make them responsible members of society who follow the laws of the state. A study conducted in Australia reviewed 76 studies, based on the teaching techniques for increasing the moral development of the learner, and half of the studies reported that the aim of moral education was to develop students in a way that could enable them to participate positively in society [46]. Female teachers in both countries reported that emotions were important when a person had to make moral decisions or actions, and that is why it was important to keep equilibrium in emotion. Whereas, male teachers pointed out that the ultimate aim of moral education was to make students responsible for their actions. In the classroom, teacher-centered teaching was recorded where the traditional lecture method was in practice. The finding of the first research question was consistent with the findings of Carr, who concluded that teachers play a paternalist role in the traditional approach to education. They are considered authoritative custodians, who have higher wisdom, values, knowledge, and ability. This concept is found in traditional and culturally homogenous communities [47].

5.2. Values and Methods Used in the Teaching–Learning Process

The findings of the second question of the study revealed that in China, political values were instilled greatly. China is a socialist country and has a rich culture and history. Teachers were promoting collectivist and socialist values in the classroom. Unity, love for family, nationalism, achievement, and self-esteem were dominant values during the lecture. Although, classroom teaching was teacher-centered, Chinese teachers were encouraging classroom discussions and practicing critical analysis in the classroom. Lind emphasized in his research that the use of the moral dilemmas technique is best for teaching morals to the students as it enhances their problem-solving approach, which ultimately helps in developing moral judgment [48]. Similar views were given by Schuitema et al. [46], who concluded that teaching methods for moral education had the elements of group discussion, role play, problem-solving learning, and dilemmas techniques, but the most chosen technique was problem-based instruction. Unfortunately, in China and Pakistan, there is a lack of adequate knowledge related to the moral dilemma, so they were unable to incorporate such activities in their lectures. Their views of moral education were reflected in the views of the research of Jones [33], who described moral education as the transmission of dominant societal values that were considered to be part of a conservative moral education that was passive in nature. Similar views were found in another study that was conducted in China, concluding that ethical education in China remained unsuitable to fulfill the needs and interests of university students [49]. In comparison with China, Pakistani teachers were promoting Islamic values such as empathy, devotion, sacrifice, honesty, and respect. There was no culture of discussion and critical thinking in the classroom. The environment of the classroom was conservative and authoritative, as compared to the Chinese one. The findings of the second research question were consistent with Kizilbash [50], who described that the present teaching practice of morals in Pakistan as promoting the socialization of dutiful, passive, and aloof citizens who need cognitive skills such as decision-making, inquiry or questioning, and the problem-solving approach, but they are were narrow-minded and lacking the quality of being independent and learned citizens.

5.3. The Basis for Selecting the Methods in Teaching Moral Education

According to the last question of the study, teachers from both countries discussed that they brought into consideration their general ideas, common sense, personal experience, and parents’ and teachers’ instruction of their childhood, instead of any specific curriculum guidelines, while selecting the method for teaching morals. Females were found more confused as compared to males. There was not a single teacher in Pakistan and China who reported that they consulted any theory, model, or research to prepare their lesson. The curriculum was less explicit. The majority of the teachers were using their unwritten principles based on their own experiences and dogmas. The results of the study supported the research of Abebe and Davis; Fenstermacher; and Jackson, et al., who mentioned that today’s teachers were confused in articulating the meaning of moral education [51,52,53].

This study was conducted to compare moral education insight in China and Pakistan, where the philosophy varied from one another. China follows Marx, Lenin, and Mao’s political ideology, while Pakistan sets moral values on the basis of Islamic teachings and philosophy. This is why the present study might be applicable in the countries of socialist republics, like Russia, Laos, and Muslim states such as Iran, Turkey, Malaysia, and Indonesia, who follow Islamic values and traditions. However, moral education is likely to be relevant for the rest of the world because moral education for sustainability has become a global issue.

6. Conclusions

This study, on the comparison university teachers’ perception in China and Pakistan about moral education for sustainable development, revealed that the institution and most teaching and learning practices are not conducive to the preparation of morally developed persons that contribute to the sustainable development of country. The EFL classroom is an appropriate place for supporting the goal of moral education for development. However, the integration of moral education into EFL textbooks and classrooms is still in its early stages. Hence, it is necessary to include cultural, universal, and moral values in language teaching and Islamic Studies classes, as it promotes globalization as well as intercultural and international communication. Therefore, it is of high necessity for university teachers to take time from core subjects to focus on embedding the blend of values in the lecture, and to train their students in morally sustainable values. There is also a need to integrate the moral models and theories with the teacher training programs in both China and Pakistan, such as the Konstanz method of dilemma discussion (KMDD), developed by German psychologist Georg Lind, which has been proven effective in students’ moral growth. The teachers must be trained and equipped with modern methods and models while teaching moral education into the classroom following their sociocultural needs. The adaptation of such methods and programs would enhance socialization and critical moral reflections in learners. The findings of this study have implications for future research—both experimental and longitudinal studies on university EFL and Islamic Studies teachers could provide insight into how attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs are formed over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.A. and O.G.; methodology, T.A. and S.K.; software, T.A. and N.u.A.; validation, T.A.; formal analysis, T.A.; investigation, T.A.; resources, O.G.; data curation, T.A. and M.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, T.A.; writing—review and editing, T.A., M.A.H and J.C.; visualization, T.A.; supervision, O.G.; project administration, O.G.; funding acquisition, O.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by center of strategic and discourse studies of China, N.59-E142-19-103.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

| S.No | Statement | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Values Focused | ||||||

| 1. | I focus on ideological values in the classroom | |||||

| 2. | I think universal values are more important to teach to the students | |||||

| 3. | Cultivation of spiritual life is essential to develop a moral person so my priority is to teach religious values to the students | |||||

| Values and Students’ Cognitive Level | ||||||

| 4. | University students are prepared for the practical life so the values like leadership, success, and achievement are considered necessary and suitable for the cognitive level of student | |||||

| 5. | Instead of preparing them for future life my concern is to make them a good human being, so adoption of basic values are important rather than instilling values according to their cognitive level | |||||

| Promoting classroom discussion | ||||||

| 6. | I don’t think classroom discussion helps in students’ ethical development | |||||

| 7. | The best way to enhance the moral competency of the students is to participate in classroom discussion | |||||

| Critical Thinking and Problem Solving Approach | ||||||

| 8. | Promotion of critical thinking leads to moral development | |||||

| 9. | The problem-solving approach teaches students how to solve the moral situation in real life | |||||

| 10. | Critical thinking and the problem-solving approach do not play any role in the ethical development of students | |||||

| Concept of moral education | ||||||

| 11. | Moral education refers to the moral values and conduct of society. | |||||

| 12. | Moral education means helping students to understand the meaning of life and one’s mission and purpose. | |||||

| 13. | The concept of moral education is to teach the students about the concept of self-responsibility | |||||

| Application of Teaching Methods in the Classroom during Teaching Morals | ||||||

| 14. | Teachers are considered a role model for students so the best method is being a role model. | |||||

| 15. | I adopt methodology according to the student behavior, that is called a reactive approach | |||||

| 16. | I use blends of different methods such as role-play, group discussion, and moral dilemmas to teach moral education. | |||||

| Basis for Selecting Method for Teaching Moral Education | ||||||

| 17. | I do not prefer to use my general ideas to teach moral education in the classroom. | |||||

| 18. | My personal experiences and parents’ and teachers’ instruction in my childhood are important in selecting teaching method besides the curriculum guidelines. | |||||

| 19. | I consult theories and latest research to select a methodology to teach moral education | |||||

Appendix B

Table A1.

Independent T-Test for Research Hypotheses.

Table A1.

Independent T-Test for Research Hypotheses.

| Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t-Test for Equality of Means | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | t | df | Sig. (2-Tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | |||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

| The concept of moral education of Pakistani and Chinese teachers are similar | Equal variances assumed | 0.794 | 0.249 | −1.877 | 237 | .060 | −0.1773 | 0.10002 | −0.37980 | 0.00927 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.940 | 177.556 | .054 | −0.18803 | 0.09729 | −0.37975 | 0.00426 | |||

| The teaching methods of Pakistani and Chinese teachers in the classroom are similar | Equal variances assumed | 0.819 | 0.241 | −1.711 | 237 | 0.060 | −0.1881 | 0.11185 | −0.40113 | 0.00831 |

| Equal variances not assumed | −1.748 | 177.286 | 0.043 | −0.97879 | 0.10041 | −1.17669 | 0.00090 | |||

significant difference <0.05.

References

- Ozturk, I. The role of education in economic development: A theoretical perspective. SSRN Electron. J. 2008. [CrossRef]

- Mariaye, M.H.S. The Role of the School in Providing Moral Education in a Multicultural Society: The Case of Mauritius. Ph.D. Thesis, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Merritt, E.G.; Hale, A.; Archambault, L. Changes in pre-service teachers’ values, sense of agency, motivation and consumption practices: A case study of an education for sustainability course. Sustainability 2018, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. International, Moral and Value Education; United Nations Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2006; Available online: http://www.unescobkk.org/index.php?id=598 (accessed on 25 October 2019).

- Clark, C.; Peterson, P. Teachers’ thought processes. In Handbook of Research on Teaching; Wittrock, M., Ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 255–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatovich, F.R.; Cusick, P.A.; Ray, J.E. Value/Belief Patterns of Teachers and Those Administrators Engaged in Attempts to Influence Teaching; Institute for Research on Teaching, Michigan State University: East Lansing, MI, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, J. Teacher influence in the classroom: A context for understanding curriculum translation. Instr. Sci. 1981, 10, 259–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J.; Wagenaar, R. Tuning Educational Structures in Europe; University of Deusto Bilbao: Bilbao, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pantic, N.; Wubbels, T. Teacher competencies as a basis for teacher education—Views of Serbian teachers and teacher educators. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2010, 26, 694–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fives, H.; Buehl, M.M. What do teachers believe? Developing a framework for examining beliefs about teachers’ knowledge and ability. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2008, 33, 134–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanger, M.N. What we need to prepare teachers for the moral nature of their work. J. Curric. Stud. 2008, 40, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almani, A.S.; Soomro, B.; Abro, A.D. Impact of Modern Education on the Morality of Learners in Pakistan: A Survey of Sindh. Indus J. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2012, 2, 99–107. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrettin, P. Innovation and global issues in social sciences 2017. J. Econ. Libr. 2017, 4, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Haq, S. Moral education in Pakistan. J. Moral Educ. 1980, 9, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Khanam, A.; Dogar, A.H. A comparative study of moral development of students from private schools and Deeni Madrasah. J. Res. Reflect. Educ. 2017, 2, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, L.; Minghua, Z.; Bin, L.; Hongjuan, Z. Deyu as moral education in modern China: Ideological functions and transformations. J. Moral Educ. 2004, 33, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.O.; Ho, C.H. Ideopolitical shifts and changes in moral education policy in China. J. Moral Educ. 2005, 34, 413–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maosen, L. Moral education in the People’s Republic of China. J. Moral Educ. 1990, 19, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, H.D. The place of moral and political issues in language pedagogy. Asian J. Engl. Lang. Teach. 1997, 7, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shaaban, K. A proposed framework for incorporating moral education into the ESL/EFL classroom. Lang. Cult. Curric. 2005, 18, 201–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.Y.; Leung, P. The effects of accounting students’ ethical reasoning and personal factors on their ethical sensitivity. Manag. Audit. J. 2006, 21, 436–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Thomas, S. A cross-cultural comparison of the deliberative reasoning of Canadian and Chinese accounting students. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 82, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.M. How Leadership May Affect Attrition: Lived Experiences of Executive Chefs; Northcentral University: Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jarrar, A. Moral values education in terms of graduate university students’ perspectives: A Jordanian sample. Int. Educ. Stud. 2013, 6, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, B. Values in English Language Teaching; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, B.; Buzzelli, C.A. The moral dimensions of language education. Encycl. Lang. Educ. 2008, 1, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Asta, B.; Margarita, T.; Daiva, T. Challenges of foreign language teaching and sustainable development competence implementation in higher education. Vocat. Train. Res. Real. 2018, 29, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, J.M. Values and values education in schools. In Values in Education and Education in Values; Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc.: Bristol, PA, USA, 1996; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, D.; Watson, M.S.; Battistich, V.A. Teaching and schooling effects on moral/prosocial development. Handb. Res. Teach. 2001, 4, 566–603. [Google Scholar]

- Killen, M. Handbook of Moral Development; Informa UK Limited: Colchester, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Power, F.C.; Higgins, A.; Kohlberg, L. Lawrence Kohlberg’s Approach to Moral Education; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ottaway, K.; Durkheim, E.; Wilson, E.K.; Schnurer, H. Moral education. Br. J. Sociol. 1962, 13, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T. Framing the framework: Discourses in Australia’s national values education policy. Educ. Res. Policy Pract. 2008, 8, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killen, M.; Smetana, J.G.; Smetana, J. Thought, emotions, and social interactional processes in moral development. In Handbook of Moral Development; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2006; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Nucci, L. Classroom management for moral and social development. In Handbook of Classroom Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G. The Moral Education Curriculum and Policy in Chinese Junior High Schools: Changes and Challenges; University of Alabama: Tuscaloosa, AL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, R.; Malik, K.; Riaz, W. 3 Patients Die as Lawyers’ Protest Outside Lahore Hospital Turns Violent. DAWN Home Page. Available online: https://www.dawn.com/news/1521675 (accessed on 16 November 2019).

- Hancock, T.; Wang, X. China Drug Scandals Highlight Risks to Global Supply Chain. Financial Times Home Page. Available online: https://www.ft.com/content/38991820-8fc7-11e8-b639-7680cedcc421 (accessed on 18 November 2019).

- Burhanuddin, B.; Majid, N.; Hikmawan, R. Implementation of character education using Islamic studies in elementary school teacher training. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Teacher Training and Education, Surakarta, Indonesia, 20–21 July 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Huberman, M.A.; Huberman, M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, S. Teacher Evaluation: Global Perspectives and Their Implications for English Language Teaching: A Literature Review; British Council: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hinchey, P.H. Finding Freedom in the Classroom: A Practical Introduction to Critical Theory; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.C.; Farrell, T.S. Practice Teaching: A Reflective Approach; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alshehri, E. Classroom Observation for Professional Development: Views of EFL Teachers and Observers. Arab World Engl. J. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goe, L.; Bell, C.; Little, O. Approaches to Evaluating Teacher Effectiveness: A Research Synthesis; National Comprehensive Center for Teacher Quality: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schuitema, J.; Dam, G.T.; Veugelers, W. Teaching strategies for moral education: A review. J. Curric. Stud. 2008, 40, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, D. Moral values and the teacher: Beyond the paternal and the permissive. J. Philos. Educ. 1993, 27, 193–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, G. How to Teach Morality: Promoting Deliberation and Discussion, Reducing Violence and Deceit; Logos Verlag Berlin GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Moral Education in the Emerging Chinese Society; McGill University Libraries: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kizilbash, H. Pakistan’s Curriculum Jungle: An Analysis of the SAHE Consultation on the Undergraduate Curriculum in Pakistan; SAHE Publication: Karachi, Pakistan, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Abebe, S.; Davis, W. Transcendence in the public schools: The teacher as moral model. J. Coll. Character 2004, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenstermacher, G.D. Some Moral Considerations on Teaching as a Profession; Jossy-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1990; pp. 130–151. [Google Scholar]

- Oser, F.K.; Jackson, P.W.; Boostrom, R.E.; Hansen, D.T. Ethnographic inquiries into the moral complexity of classroom interaction the moral life of schools. Educ. Res. 1995, 24, 33. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).