Abstract

The danwei system is one of the most important institutional arrangements in the Chinese planned economy era (1950s–1970s). It also offers a clue to understanding China’s urban transformation since the economic reform. This paper aims to explore the spatial prototype of the danwei system and understand the internal logic for the operation of this system by conducting a case study of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory. Focusing on the obligation of the factory to run social welfare services, the danwei system formed a so-called “corporate-run society”. A sustainable mechanism for production and reproduction is conceptually portrayed. The institutional practice of the danwei system is understood as a process that is in accordance with socialist constructions, the public ownership system, and state socialism. This paper argues that it is necessary to reconfigure the legacies of the danwei system and explore its implications for contemporary Chinese society.

1. Introduction

After the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the danwei system was established in urban areas under the planned economy and was generally considered one of the most important institutional arrangements at that time [1]. Relying on state-owned enterprises and public institutes to dominate resource allocation and social management, this system profoundly affected the interactions among the state, social organizations, and individuals and shaped people’s lifestyles in a collective society [2,3]. Although this system has been gradually rolled back since China’s reform and opening up commenced in 1978, many of its economic, social, spatial, and ideological legacies have remained in place in the past 40 years and are still influencing urban transformation and development in contemporary China [1,4]. Hence, the danwei system is recognized as a key to understanding China’s urban transformation [5,6].

Although research from multiple disciplines has continuously explored the danwei system, there is still an absence of a clearly defined spatial prototype of this system, which prevents us from obtaining a deep understanding of its nature and its implications for contemporary society. In the past, some studies have focused on exploring the resemblance, or isomorphic relationships, between the danwei system and other systems. For example, special attention has been paid to a few Western countries’ utopian socialist practices in the 19th Century and early 20th Century. “New Harmony” was an idea originally envisioned by Robert Owen, which was later implemented as a social experiment in a town in Indiana, the Unite States. Similarly, the idea of “Phalanstery” was developed by Charles Fourier, which expected to gather 500–2000 people together in the community. Both cases were designed as a self-contained utopian community, where people could continuously work and live together and obtain everything they need. Moreover, some socialist practices in neighboring countries have also been considered to inspire the establishment of the danwei system directly. The movement of “New Village” that advocated anarchism appeared in Japan in the early 20th Century, which was regarded as another type of utopian socialism [7]. This movement was then spread to China during the early Republic and had a great impact on many young Chinese at that time [8]. More recently, the Soviet model provided a government-led institutional design under which labor movement and labor policies were collectively organized by the Communist Party [9]. In addition, domestic experiences also suggested some clues to the establishment of the Chinese danwei system, such as the experience of collective supply in revolutionary bases during the Chinese revolutionary war [10] and the more traditional ideas of kinship ties and the patriarchal clan system originated in ancient China [11]. However, all these studies failed to present evidence or proof that the danwei system is directly derived from these systems.

On the other hand, another branch of studies has focused on exploring why the danwei system emerged in China’s specific socioeconomic environment. For example, Jianjun Liu [12] applied the concept of the integrity crisis and the increase in aggregate demand and the economy to explain the rationality of the establishment of the danwei system. Duanfang Lu [13] held that the danwei-based special strategy was formed as a result of the material shortage and accumulation insufficiency driven by Chinese modernization. These studies were rooted in exploring the deep impact of the national crisis and the social transformation after the founding of the PRC [14]. However, they did not properly address the fundamental question of why China decided to establish such a danwei system rather than adopting other strategies.

In this paper, we want to investigate the origin and formation of the danwei system as a starting point for the exploration of related research topics in urban China. Existing literature has presented the advantages of the establishment of the danwei system to Chinese urban society right after the founding of the PRC, especially in terms of enhancing the efficiency of resource allocation, providing social welfare and social stability, and strengthening collectivism [10,15]. However, the danwei system also has serious drawbacks. Due to its closed structure, the system only maintained a very low level of production and was unable to mobilize people and the society [12]. Moreover, since it overemphasized organizational management and strict control of the flow of production factors and the mobility of workers, the system deactivated and stagnated the development of urban spaces and social structure [16]. Some other studies also mentioned emerging problems such as adverse selection and soft budget constraints [17]. These abuses of the system have brought about internal conflicts between urbanization and social development and created the need for institutional evolutions. Based on these existing discussions of the advantages and disadvantages of the danwei system, this paper aims to revisit the incentives for the establishment of the danwei system and identify the internal logic of the operation of this system in the early years of the PRC. In addition, the paper also aims to investigate how the system’s institutional arrangement profoundly influenced urban development in Chinese cities in the past and explore how the legacies of the system can be applied to contemporary Chinese society.

We propose that understanding the core of the danwei system means understanding the effects of the model of the “corporate-run society”. Although “society” here has a rich meaning, we think that the essential meaning of the concept of the “corporate-run society” should be understood as corporations undertaking the role of supplying social welfare and public goods that are supposed to be managed by the government or the market due to the latter group’s inability to provide such services. Initially, the formation of the danwei system could be rooted in the insufficient supply of products for the whole society during China’s postwar reconstruction period. Later, this self-sufficient model was solidified and reinforced to form the collective life of the danwei society for the following decades. A case study of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory will be included in this research to explore a spatial prototype of the danwei system and shed light on its functions and impacts. This factory was a typical danwei compound in Beijing constructed in the planned economy era; the spatial arrangement of most of its buildings and facilities is still clearly visible. Accordingly, we will examine its spatial practices and operation mechanisms in detail to help us understand the complex roles of the danwei system in urban governance and social affairs.

2. Corporate-Run Society: The Institutional Logic of Collective Production and Consumption

2.1. Reconceptualizing the Model of the “Corporate-Run Society” in an International Context

The phenomenon of the “corporate-run society” (qiye ban shehui) is commonly discussed in China as an issue of the danwei system when reflecting on the Chinese tradition of state-owned enterprises bearing the heavy burden of the social security system nationwide since the planned economy era [18]. However, the situation of corporations providing public services and welfare products to employees exists not only in socialist China, but also in many socioeconomic and institutional contexts in both Western and Eastern countries. Here, we want to extend our understanding of the model of the “corporate-run society” to describe such situations generally in an international context. In view of the characteristics of many international cases in different contexts, the causes of the emergence of this model are summarized as follows.

First, a corporate-run society may appear at the early stage of industrial revolutions; for instance, the model villages in Britain [19,20], the company towns in the United States that were established by steel and coal companies during the Westward Movement [21], and the mono towns in the Soviet Union during the country’s planned economy era [22]. Second, such a society may appear during war or at a crisis stage, as was the case of the kibbutzim in Israel [23,24] and the revolutionary base areas in the early stage of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) [25,26]. Third, such a society may appear in the era of a faded market under the public ownership economy, which for example happened with the kolkhozy (collective farms) in the Soviet Union during the collectivization of the country’s agricultural sector [27]. Fourth, such a society may appear in an era of market failure, such as the corporate communities built by high-tech companies in California to bail their employees out of the soaring real estate prices in recent years. Under these circumstances, it is deemed the obligation, rather than the philanthropy, of enterprises to provide social welfare as a benefit for their employees.

The above scenarios show that a corporate-run society often emerges when the market is undeveloped or underdeveloped, and therefore, in lieu of a market or before the emergence of a market, enterprises or other nonmarket bodies are forced to provide social services and welfare in a collective and organized manner. Such features, to some extent, tally with the studies on the supply of public goods at the theoretical level. According to Webster [28], the essence of a neighborhood is subject to the contracts for supplying public goods in a club way, which also leads to the emergence of collective consumption. The provision of public goods by neighborhoods or related entities is a third path that sits between the governmental provision of noncompetitive products and the market provision of competitive products. In this context, the model of the “corporate-run society” is understood as corporations serving as suppliers of public goods to their corresponding communities that are exclusively available to the corporations’ members, which is just like the supply of club goods.

It is emphasized that the provision of public goods by enterprises should be understood as a fundamental function in the operation of a corporate-run society. This function plays an important role in facilitating the collective production and consumption in a given space. Thus, such action forms a self-contained society where relevant stakeholders follow the collective lifestyle.

2.2. “Corporate-Run Society” in China under State Socialism

The formation of the danwei system, as Morris L. Bian [18] (p. 142) notes, was closely connected to the early practices of corporate-run society in China, or what he called “the employees’ welfare society”. This can be traced back to the Westernization Movement in the late Qing Dynasty [18]. Due to the insufficient social supply, undeveloped market economy, serious inflation, and social turmoil, the government and a number of entrepreneurs had to provide public and social services as a type of welfare to ensure the ongoing production of modern factories and retain employees. For example, as recorded in the chronicle of the Jiangnan General Manufacturing Bureau, its head factory, which was the largest and most important Chinese ordnance factory in the late Qing Dynasty, had already constructed residential buildings, a mansion house, schools, and guest houses, among others, in the early stages of the factory’s establishment [29]. Another important period that witnessed the development of the “corporate-run society” in China, according to Bian [18], was during the War of Resistance Against Japan. At that time, many factories, especially ordnance factories, chose to locate themselves far away from urban areas for reasons of safety, the supply of raw materials, transportation, and so forth, and thus, they had to build themselves social services and a welfare system. On the other hand, since the safer inland areas in Western China had long been part of an agricultural civilization, there was a serious shortage of skilled workers. Factories thus increased the supply of welfare facilities to attract skilled workers from coastal areas to move inland.

The factories were not alone in establishing a welfare society. According to Wen-Hsin Yeh’s research on the city branch of the Bank of China in Shanghai from the 1930s to the 1940s, the bank provided housing for its employees and built gardens, pavilions, tennis courts, basketball courts, auditoriums, and classrooms nearby [30]. This strategy placed most of the staff’s daily life under the bank’s coordination and control. Yeh [30] holds that this urban lifestyle was strikingly similar to the life in the socialist danwei compound after 1949. Although this corporate community might not be the direct source of the formation of the danwei compound, it showed that a significant part of the middle class in Shanghai had already experienced socialized collective life for many years before the emergence of the danwei system. More importantly, under such a corporate management system, most of the boundaries between the public and the private and between corporations and individuals were blurred.

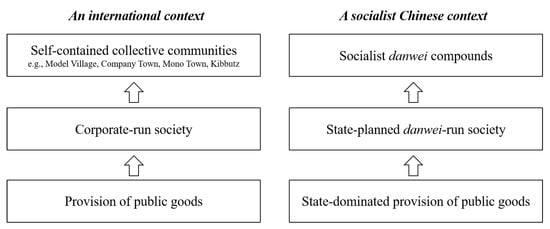

Arguably developed from these previous experiences, the danwei system even strengthened and deepened the practice of the “corporate-run society”, which we also refer to as the “danwei-run society”. The danwei-run society generally matches the model of the “corporate-run society”, though it still has exceptional features that distinguish itself from other cases (Figure 1). First, the formation of the danwei system was a top-down strategy developed at a national level in accordance with the socialist reform to eliminate the role of the market [31]. In this context, the danwei system has become the only path adopted by the state to dominate the distribution of social resources. Most other forms of corporate-run societies emerged in situations of undeveloped market functions whose scale was relatively small. For example, the kolkhozy (collective farms) in the Soviet Union and the kibbutzim of Israel had fewer than 1000 people each. Meanwhile, their degree of collectivization was rather low; most of the collectivization in Israel and the Soviet Union only appeared in the form of collective farms. Different from these societies in Western countries, the Chinese danwei system, to a large extent, was a political initiative that was achieved through quick social transformation and greatly influenced Chinese urbanization and industrialization in the planned economy era. Second, this system was strictly controlled by the top-down political power of the CCP, as well as the administrative management of the government. Therefore, the danwei system not only functioned as a production organization, but also acted as a grassroots party organization and administrative organization [32]. In this system, all types of state-owned enterprises and other public institutes were also deemed administrative entities that managed the people affiliated with them. Meanwhile, party organizations were able to carry out ideological missions and organize political life for grassroots movements through these entities. Third, this system was considered a composite of urban politics, economy, and social life [17,33]. A unique collective urban society, i.e., the socialist danwei compound, developed under this system where urban governance, urban production and consumption, and social welfare services were all highly concentrated.

Figure 1.

Models of a “corporate-run society” in the Chinese and international contexts. Source: drawn by the authors.

Distinguishing from other types of “corporate-run society”, we believe that the most important feature of the “danwei-run society” is the embedded Chinese state socialism. Owing to this feature, the institutional arrangement of the danwei system enabled the country to formulate hundreds of thousands of self-contained danwei compounds nationwide in the planned economy era. Each danwei compound became the basic unit of the institutionalized organization and social structure of Chinese local society. Intrinsically supported and dominated by the state’s ownership of all social resources, the danwei system laid the cornerstone for the country’s planned economy and overall redistribution system.

The danwei system lasted for nearly three decades in China until the end of the planned economy era and the commencement of the reform and opening up in the 1980s. The movement of the dismantling of the danwei system took place under the waves of globalization and the evolution of state socialism. This movement was rooted in the great transformation of China’s social economy from nationalization to a market-oriented economy. The non-public ownership began to emerge, combined with the entry of foreign investments. Such market-oriented forces gradually promoted reforms in state-owned enterprises, government institutions, state-owned asset management systems, housing, and social welfare systems. These reforms triggered the dismantling of the danwei system in all aspects of economic and social dimensions. Therefore, the dismantling of the danwei system in Chinese cities is actually a process of redefining various types of property rights [34]. This process has promoted the transformation of physical spaces, social relationships, and people’s lifestyles. It also led to new spatial and social contradictions in the urban built environment. In particular, previous social functions and welfare provided by the danwei system have been transferred to the market and society. The shortage of public services in cities and urban communities has become one of the most important issues of urban governance. This suggests that the marketization of social functions of original danwei compounds is not an optimal solution. We need to re-examine the danwei system and extract its positive aspects for the benefits of the contemporary Chinese society. Drawing on these insights, the following sections will examine in detail how the danwei system was operated through a case study of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory.

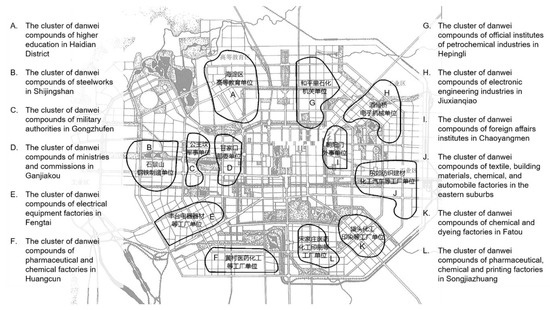

3. The Government-Led Construction of the Danwei Compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory

After the founding of the PRC, the first urban master plan of Beijing followed the mainstream idea of functional zoning at that time, decentralizing the industrial zone and administrative zone into different parts of the city. Meanwhile, in order to avoid the problems of urban sprawl and traffic congestion caused by functional separation, early urban planners of the PRC proposed that people’s workplace and residences should be placed together, which provided the basis for the establishment of the danwei system. Based on these ideas, the construction of danwei clusters in different functional zones eventually formed the spatial pattern of Beijing in the planned economy era (Figure 2). These ideas also affected the planning of other Chinese cities.

Figure 2.

The spatial distribution of the clusters of danwei compounds in Beijing after the founding of the PRC. Source: reproduced by authors according to Beijing’s master plan in 1954.

The Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory is located in the Balizhuang area of Chaoyang District in the eastern suburbs of Beijing, adjacent to the East Fourth Ring. This is a typical danwei compound of state-owned enterprise constructed in the early years of the PRC. In the 1950s, the textile industry was highlighted as one of the leading industries in Beijing to recover the city’s economy, and the Balizhuang area in the eastern suburbs of the city was designated as a textile industrial zone [35]. The Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory was the first large-scale modern factory for cotton textile in China that was fully equipped with original domestic equipment. Under the instruction of the State Planning Commission, the establishment of the factory was approved by the Ministry of Textile Industry and the Beijing Municipal Committee in November 1953. The factory’s construction was completed within a year and a half, and in 1955, it officially started operating [36].

The government-led investment in the construction of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory clearly reflects the features of the Chinese planned economy. Many leaders of the Party Central Committee and the central government inspected the factory (Figure 3). In the initial planning stage, the government was supposed to purchase land from the original land owners of this area to build the factory. After the completion of the socialist land reform movement in 1953, urban land became state property. Therefore, the government acquired the right to allocate land parcels for the construction of the factory according to industrial planning. Another manifestation of the resource allocation was the assignment of cadres and workers, especially the skilled ones [36]. The administrative cadres of this factory were transferred from municipal government officials and demobilized army officers. Those workers with technical and business skills at the beginning of the establishment of the factory were mainly transferred from the traditional textile base in Shanghai. In addition, the government also recruited new workers from secondary and vocational schools in nearby cities.

Figure 3.

Liu Shaoqi, the former Chairman of the PRC, in the factory. Source: Chen, Y. The Textile Industry in Contemporary Beijing; Beijing Daily Press: Beijing, China, 1988. (In Chinese).

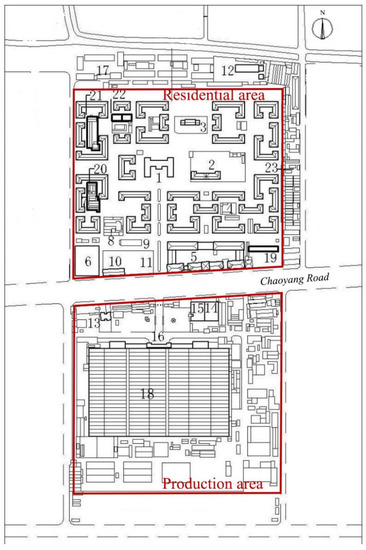

The most prominent spatial feature of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory is that it organized the spaces for the workplace and residences together in a single danwei compound. The compound was divided by Chaoyang Road, with the production area of the compound in the south and the residential area in the north (Figure 4). Factory buildings and office buildings were in the middle of the production area, with auxiliary facilities such as warehouses and garages surrounding them (Figure 5). The residential area was organized according to traditional Chinese neighborhood plans (Figure 6). An auditorium, together with a dining hall, was the center of the living space. Meanwhile, public facilities such as kindergartens and schools were also located in the central areas. Residential buildings were distributed around these public facilities. From the south to the north, factory buildings, office buildings, the main entrance, and the auditorium constituted the axis of this danwei compound.

Figure 4.

The danwei compound of Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory. 1–the dining hall; 2–primary school; 3–kindergarten; 4–garden house; 5–dormitories, a hospital, and a canteen; 6–retail store; 7–residential buildings; 8–the textile training school; 9–nurseries; 10–post office; 11–playground; 12–Balizhuang No. 2 Middle school; 13–mother and baby rooms; 14–bathrooms; 15–garage; 16–office buildings; 17–unused land; 18–factory workshops; 19, 20–newly built buildings; 21–neighborhood factory; 22–bathrooms. Source: reproduced from Zhang, Y.; Chai, Y.W.; Zhou, Q.J. The Spatiality and Spatial Changes of Danwei Compound in Chinese Cities: Case Study of Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 5, 20–27. (In Chinese).

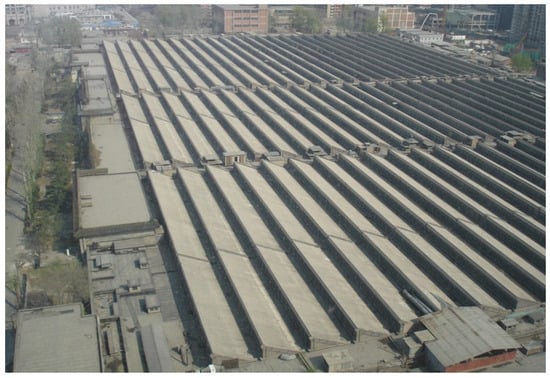

Figure 5.

The production area of the compound. Source: Zhang, Y.; Chai, Y.W. Interpreting the Cultural Connotation of Beijing’s Modern Industrial Heritages: from the Perspectives of Danwei in Urban China. Urban Dev. Stud. 2013, 20, 23–28. (In Chinese).

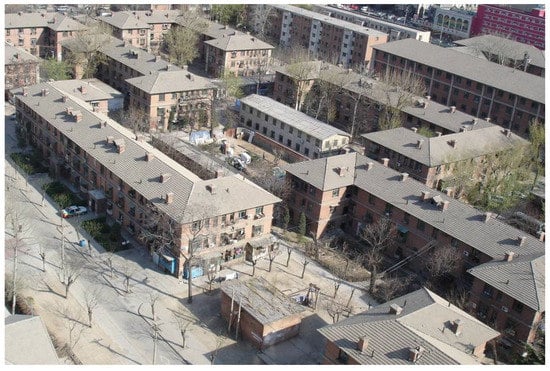

Figure 6.

The residential area of the compound constructed in the 1950s. Source: Zhang, Y.; Chai, Y.W. Interpreting the Cultural Connotation of Beijing’s Modern Industrial Heritages: from the Perspectives of Danwei in Urban China. Urban Dev. Stud. 2013, 20, 23–28. (In Chinese).

The construction of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory is a typical example of the government actively and dominantly engaging in nationalized industrial development. Such state-owned enterprises were all contained in hundreds of thousands of cell-like gated danwei compounds in Chinese cities in the planned economy era. The spatial form of the danwei compound was a reflection of the urban spatial organization of production and residential life under the danwei system. Furthermore, the construction of danwei compounds was also a major driving force for urban growth during that period.

Significantly, the danwei system was a crucial determinant of the formation of the “corporate-run society” in the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2. Textile Factory during the planned economy period. Evidence can be found in the large-scale construction of living and welfare facilities in this compound (see Figure 4). It is worth mentioning that the compound’s residential area was even larger than the production area. At the beginning of the establishment of the factory in the 1950s, the compound was already equipped with educational facilities, medical facilities, canteens, and other living facilities. Since then, these facilities have been continuously improved. Until the 1970s, welfare facilities in the living area included an auditorium, a large dining hall, a kindergarten, a primary school, a middle school, a textile industry school, a staff hospital, a post office, a retail store, baby care rooms, bathrooms, and a large number of residential buildings. Moreover, in the production area, in addition to the factory buildings, there were also welfare facilities such as bathrooms, canteens, and nurseries.

In line with all these observations, we want to summarize some main features of the danwei system that facilitated the model of the “corporate-run society”. Drawing from the case study of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory, attention was paid particularly to the process of the system that supported the productivity and people’s daily life. First, relying on a combination of administrative power and its right to state property, the government controlled the resource allocation of the whole society under a centrally planned economy and determined the construction of factories by adopting the danwei system. The danwei system was, in fact, a production-oriented system and played a crucial role in boosting urban and industrial development, through which the government dominated the organization of production and employment mobilization and gained products and profits from it. Second, the workplace and residences were often constructed together in the danwei compound. This enabled the government to manage its social members and social affairs comprehensively through danwei authorities, and a systematically organized social order was thus realized to maintain social stability. Third, the provision of satisfying living and welfare facilities boosted and sustained labor productivity in the danwei compound. With these qualities, danwei-dominated collective life in the compound was eventually formed.

4. The Production and Reproduction Mechanism in the Danwei Compound

The cell-like danwei compounds constituted a major component of the urban space during the Chinese planned economy period. They also manifested, from a spatial perspective, how the danwei system was operated. The case of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory demonstrated that all social resources were integrated into this system, which promoted the country’s industrial production and simultaneously supported a welfare society. Relying on its functional unity, its noncontractual relationship between production factors, and the immobility of resources, the danwei system shaped a communal living style centered on product production and labor reproduction [10]. In this section, we elaborate this production and reproduction mechanism in detail to articulate the collective life in the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory.

4.1. The State’s Resource Distribution System

The construction of the danwei compound was originally initiated by the state’s investment decision based on the arrangement of social resources [37]. This arrangement was subject to the deployment of industries and resources nationwide, driven by the Chinese modernization course. According to a document released in 1956 titled “The State Council’s Decision on a Few Questions of Strengthening the Construction of New Industrial Zones and Industrial Cities”, the workplace and residential area of the danwei compound should be planned in the same place, and their construction should be synchronized. The upper direct construction management acted as a superior governing body and directed the municipal government and relevant departments to arrange land allocation and dispatch resources and staff from other danwei compounds. Leaders of a danwei compound were normally assigned by upper management, while other workers were typically selected through either recruitment or labor dispatch. Their status was confirmed uniformly according to an authorized headcount. Daily production and management, including raw material allocation and delivery, product distribution, and profit management and expenditure, were also incorporated into the whole production system.

Therefore, once the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory was established, it became a part of the danwei system and was involved in the national socioeconomic circumstance. Its initial objective, resources, workers, products, and services all participated in the state’s resource distribution system. It should also be noted that due to differences in affiliation and administrative levels, different levels of danwei compounds often obtained differentiated access to resources between the state and danwei compounds. Higher level compounds or those affiliated with crucial departments tended to obtain more crucial resources and enjoy better development and living conditions.

4.2. The Sustainable Mechanism for Production and Reproduction Inside the Danwei Compound

Under the Chinese planned economy, the mandatory instruction by the state promoted production activities in the danwei compound [38]. The production activities took place in the production space of the danwei compound. The production space of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory consisted of factory buildings and office buildings, as well as the production-supporting spaces such as warehouses, shower rooms, maintenance rooms, and garages. The production space was located in the center of the compound, while the supporting spaces were on the fringe. The objective of the production process was to accomplish the production task and profit making assigned by the factory’s superior department. This production process was the result of the interactions of workers, factories, and raw materials. The process included transforming raw materials into industrial products according to industrial procedures and was a reflection of the interactive coupling of machine features and human psychological traits. In addition, this mechanism was supported by the maintenance of devices and facilities, which manifested the interaction of supporting space and production space.

Labor reproduction activities took place in the residential area of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory. The facilities that constituted this space included those that met the workers’ needs for residence, recreation, education, and health care, which facilitated labor reproduction from different aspects. Among them, auditoriums, canteens, primary schools, and kindergartens centered the residential area, while other facilities, such as residential buildings, recreational facilities, and hospitals, were often located on the fringes. This reproduction process can be divided into three parts: intragenerational labor reproduction, intergenerational labor reproduction (including workers and their children), and facility maintenance. The first two parts were the main body of labor reproduction, while the third served as support and assistance. The space for labor reproduction inside the danwei compound offered a rather full range of facilities, so much so that public facilities in other urban areas were just supplementary. This space could satisfy not only the demands for labor reproduction of one generation, but also the need to raise the next generation. In addition, compound residents were able to foster strong bonds because of their geographical and career relationships, which also enhanced their social interactions. This played a significant role in the formation of the cultural complex of the danwei compound and the sense of belonging to the space.

4.3. Interactions between Resource Distribution, Production, and Reproduction

The state’s control over the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory can be observed not only in the initial formation stage, but also from the direct intervention of the superior department for the daily operation of the danwei compound, including production orders, living standards, codes of conduct, ideology, and education guidance. This also reflects the relationships between the national modernization system and specific functional modules. Each danwei compound functioned as an integral part of the planned economy. It was the planned economy that facilitated the sustainable mechanism for production and reproduction.

Meanwhile, in this mechanism, product production interacted with labor reproduction. From the perspective of time-space usage, workers scheduled their daily lives around the plan for working hours. Three time-space usage modes were formed according to a pattern of “three shifts per 24 hours” (sanbandao) to ensure that the factory operated 24 h a day. From the perspective of labor-material exchange, laborers were compensated with salaries and welfare from production activities. In addition to providing necessities and sustenance, these benefits also served as the material foundation for the cultivation of future generations. This fostered the reproduction of workers in both the present generation and the next generation. Despite a small proportion of workers’ children who moved away to find jobs in other danwei compounds or went to college, the majority took over their parents’ jobs. Thus, in this production and reproduction mechanism, each member of the danwei compound acted in accordance with his or her position and fulfilled his or her duty in production and life practices, which, in turn, helped realize social responsibility and sustainability.

Accordingly, the danwei system was continuously built and strengthened upon each existing danwei compound, such as the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory. All resources were monopolized by this system for the whole country’s production and consumption. The elimination of market power because of the socialist reform further necessitated the role of the “corporate-run society”. At the national level, the guidelines for the development of the danwei system were formed, emphasizing that all resources were devoted to this system, all necessities depended on this system, and all urban residents were required to live and work in a danwei compound. However, because the allocation of resources was centralized and cyclical only among danwei compounds, this led to the paternalism of public ownership, soft budget constraints, and a lack of production incentives. Consequently, involution arose due to a low level of repetitive production, which failed to stimulate social and economic growth and thus led to a new round of social crisis.

Such a crisis gave rise to the movement of the dismantling of the danwei system, accompanied by Chinese economic reform since the 1980s [5,39,40]. However, it should be emphasized that the strategy for the supply of public goods under the danwei system is still of practical significance to the contemporary society. For example, we have observed that many urban communities, especially those in suburban areas, tend to receive inadequate public facilities because the local government is unable to provide support or the market finds that it is not profitable. Such a situation has forced many companies (especially developers) to explore new approaches to providing public products in these communities. This is once again the emergence of “corporate-run society” with new conditions. Therefore, we call for a return to the examination of the Chinese danwei system that existed a few decades ago, exploring its production, reproduction, and distribution mechanisms in the provision of public goods and incorporating these experiences into current practices of community governance and management.

5. Conclusions

This paper delineated the spatial order of the danwei compound of the Beijing No. 2. Textile Factory in Beijing to shed light on the fundamental paradigm of the Chinese danwei system. As a typical state-owned danwei compound constructed after the foundation of the PRC, the factory’s workplace and residences were organized together, forming a particular socialist collective society of production and consumption. The state socialism and the mentality of prioritizing production and postponing consumption enforced the danwei system for organizing society and allocating resources, constantly weakening, replacing, and even invalidating the role of the market. In the case of the Beijing No. 2 Textile Factory, the danwei system bonded with the planned economy and formed a sustainable mechanism for product production and labor reproduction inside this danwei compound. This mechanism can be viewed as a fundamental operation pattern of the danwei system in the Chinese institutional environment and context during that special period. Nevertheless, in its most basic sense, the danwei compound was essentially an organization or a place for people to work. The danwei system provided all kinds of public services and social welfare and held the functions and attributes of social organizations, which were closely related to a person’s whole life. From our point of view, the model of the “corporate-run society”, which applies an organizational supply of public goods, was the fundamental prototype of this danwei system. Based on this, we depicted the dynamics of the evolution of the danwei system in practice and pinpointed key issues from the internal logic of urban transformation.

It is worth noting that the organizational supply model of public goods is reasonable at both the theoretical and empirical levels. In their processes of social transformation and the governance of public affairs, Western countries have developed the theories of multicenter, club goods and the private production of public goods to determine the causes of market failure and government failure. For China, in the era of the planned economy, the construction of danwei compounds played an important role in providing urban public services, which actually developed a decentralized supply of resources and provided support for state-owned enterprises, government agencies, and institutes. This system arguably overcame the supply shortage at the national level and enhanced the supply of public services. Opportunistic behaviors appeared in a post-danwei period after the economic reform, and the private production of public goods in a community was commonly found in China [17,39,41]. With the deepening of the dismantling of the danwei system, the social functions of the danwei system and the government have been decoupled and transferred to the market and society at large, which often leads to the shortage and chaotic supply of public services [42]. Therefore, we need to find a better solution to providing public goods through multiple channels involving the government and the market. Scholars have called on the government, community residents, community organizations, companies, authorities, non-authorities, and other social and market entities to manage public affairs jointly in the community in order to improve community autonomy and actively respond to public issues [43,44]. Therefore, it is important to unveil the myths of the danwei system and draw on the experience of this system in the organizational supply of public goods under the current Chinese urban institutional environment to contribute to solving key problems of today’s urban development, as well as those that will arise in the near future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.X., T.L. and Y.C.; Investigation, Z.X. and T.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.X., T.L. and M.Z.; Writing—Review & Editing, M.Z.; Supervision, Y.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number: 41571144.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bray, D. Social Space and Governance in Urban China: The Danwei System from Origins to Reform; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.L. Integration Mechanism of Chinese Danwei Phenomenon and Urban Community. Sociol. Res. 1993, 5, 23–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Zhou, F.Z.; Li, K. Danwei: The Inside of the Institutionalized Organization. Chin. Soc. Sci. Q. 1996, 16, 135–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bray, D. Building ‘community’: New strategies of governance in urban China. Econo. Soc. 2006, 35, 530–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.W.; Zhang, Y. Introduction: Research on the Transformation of Danwei in urban China. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 24, 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ta, N.; Chai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, D. Understanding job-housing relationship and commuting pattern in Chinese cities: Past, present and future. Transp. Res. Part D: Transp. Environ. 2017, 52, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.Y. The Last Oasis: Atarashiki-mura in Today’s Japan. Twenty-First Century Bimon. 2005, 88, 113–121. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, G.J. Workers’ New Village: Eternal Happiness–an Interpretation of Workers’ New village in Shanghai in 1950s and 1960s. Ph.D. Thesis, Tongji University, Shanghai, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lü, X.B.; Perry, E.J. Danwei: The Changing Chinese Workplace in Historical and Comparative Perspective; M.E. Sharpe: Armonk, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, F. Danwei: A Special Form of Social Organization. Soc. Sci.China 1989, 1, 71–88. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.L. Research on Danwei Studies. Sociol. Res. 2002, 5, 23–32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.J. Danwei in China: Individuals, Organizations and Countries in the Social Regulation System; Tianjin People’s Press: Tianjin, China, 2000. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lu, D.F. Remaking Chinese Urban Form: Modernity, Scarcity and Space, 1949–2005; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.P.; Liu, J. Reevaluation of the historical status of the “Danwei society”. Study Explor. 2010, 4, 41–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Walder, A.G. Communist Neo-Traditionalism: Work and Authority in Chinese Industry; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.P.; Qi, S. The Termination of the Unit Society: The Community Construction under “Typical State-unit System” of Northeastern old Industrial Bases; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2005. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.H.; Yang, X.M. The Chinese Danweii System; China Economy Press: Beijing, China, 1999. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bian, M.L. The Making of the State Enterprise System in Modern China: The Dynamics of Institutional Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, M. Bournville: Model Village to Garden Suburb; The History Press: Stroud, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Havinden, M. The model village. In The Rural Idyll; Mingay, G.E., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Green, H. The Company Town: The Industrial Edens and Satanic Mills that Shaped the American Economy; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Russian Economic Report, No. 22, June 2010: A Bumpy Recovery. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/27777 (accessed on 2 December 2019).

- Gavron, D. The Kibbutz: A wakening from Utopia; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Amit-Cohen, I.; Sofer, M. Cultural heritage and its economic potential in rural society: The case of the kibbutzim in Israel. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 368–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, E. Red Star Over China: The Classic Account of the Birth of Chinese Communism; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1938; pp. 220–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.B.; Lin, B.J. The History of the Central Soviet Area of China; Jiangxi People’s Press: Nanchang, China, 2001. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Laird, R.D. Kolkhozy, the Russian achilles heel: Failed Agrarian reform. Europe. Stud. 1997, 49, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C. On the nature of neighborhood. Urban Stud. 2003, 40, 2591–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Institute of Economics of Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. The History of Jiangnan General Manufacturing Bureau; Jiangsu People’s Press: Nanjing, China, 1983. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, W.H. Corporate Space, Communal Time: Everyday Life in Shanghai’s Bank of China. American Historical Rev. 1995, 100, 97–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L. Decentralization as a mode of governing the urban in China: Reforms in welfare provisioning and the rise of volunteerism. Pac. Aff. 2013, 86, 835–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Everyday Power Relations in State Firms in Socialist China: A Reexamination. Mod. China 2017, 43, 288–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.W. From socialist danwei to new danwei: A daily-life-based framework for sustainable development in urban China. Asian Geogr. 2014, 31, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.N.S. The Economic System of China; CITIC Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Chai, Y.W.; Zhou, Q.J. The Spatiality and Spatial Changes of Danwei Compound in Chinese Cities: Case Study of Beijing No.2 Textile Factory. Urban Plan. Int. 2009, 5, 20–27. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. The Textile Industry in Contemporary Beijing; Beijing Daily Press: Beijing, China, 1988. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, T. ‘Newness’ in social entrepreneurship discourses: The concept of ‘danwei’ in the Chinese experience. J. Soc. Entrep. 2011, 2, 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.F. Everyday Modernity in China: From Danwei to the “World Factory”. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2019, 12, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Housing privatization and the return of the state: Changing governance in China. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Ley, D. Residential relocation and the remaking of socialist workers through state-facilitated urban redevelopment in Chengdu, China. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2480–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.H.; Liu, W. Community Public Goods Production from the Perspective of Institution Transformation: From “Danwei System” to “Community System”. Urban Dev. Stud. 2006, 13, 64–70. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S. Social Networks in the Workplace in Postreform Urban China. SAGE Open 2017, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.G. The Analysis of the Totalism of Chinese Political Party System and its Political Modernization. Soc. Sci. Res. 2006, 2, 57–63. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Kleinhans, R.; Van Ham, M. Ambivalence in place attachment: The lived experiences of residents in danwei communities facing demolition in Shenyang, China. Hous. Stud. 2019, 34, 997–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).