Abstract

The postsocialist process of urban restructuring came with important spatial, social, and economic consequences. This triggered important transformations that remain palpable in the everyday texture of urban life, spatial patterns, and even the internal structures of the city. Every urban settlement was bound to contribute to the state socialist industry so that postsocialist urban transformations also included multiple aspects of dereliction and ruination of the socialist industrial assets. Threatening postsocialist urban formations and sustainability, the most common feature is collective neglect at national, regional, and local scales. The transition from state-socialist forms of production to the current market-based system poses many difficulties. This article specifically investigates the problems of urban industrial ruins in Lugoj—which are typical for medium-sized postsocialist municipalities in Romania. The research draws on qualitative data gathered by the authors through semi-structured interviews, personal communication, and oral histories and continuous infield observation (2012–2019). The findings unveil the production and the reproduction of abandoned spaces in Romanian urban settlements in the absence of specific regeneration programs and policies on urban redevelopment and marginalized areas. The analysis reveals that urban ruins harm the quality of life in local communities, damaging both the urban landscape and local sustainability. Further actions for local urban regeneration are urgently needed.

1. Introduction

In the recent context of postsocialist geographies of de-/reindustrialization, ruin creation, and place making, the present study deals with de-/reindustrialization, urban dereliction, and ruins, a family of topics, both fascinating and omnipresent in cities throughout the world [1,2,3]. The article examines the spatial results of local economic changes with urban ruined sites left in the wake of the transition from the state-socialism to a market economy. Furthermore, the paper draws on the local variables situated in the cities and to the “specific political, economic, social and cultural relations” [4] (p. 43), associated to particular policies required at the local level [5]. The analysis focuses on the municipality of Lugoj in Romania, a postsocialist country, which fills the gap in the present knowledge of the material and institutional dynamics of ruin creation in Eastern European societies [2,6,7]. The purpose of this contribution is to discuss the postsocialist urban ruins in Lugoj, and to explain their presence, 30 years after the collapse of state-socialism. Against the general background of processes creating Romanian urban ruins, this paper investigates the urban dereliction and production of urban ruins as exemplified by a medium-sized city that is categorized as a nonmetropolitan town. This topic is not limited to a singular type of ruin, but can take a myriad of forms. Outlining a variety of ruins in the cities, the empirical data explains the local government’s indifference to the postsocialist ruins production, their consequences in the urban landscapes, and the local impact on the local restructuring [4]. The study emphasizes the postsocialist economic transformations through which urban ruins intensely mushroomed [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Despite a rich body of literature dealing with the postsocialist urban identity formation as well as the social and economic consequences of the cities’ restructuring [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], the issues of urban dereliction remain peripheral at the local level. Against such a background, “scholarly interest in ruins and derelict spaces has intensified over the last decade”, the recent studies being disparate, with no sustained investigation. Furthermore, “research into ruins can inform and energize critical investigations of how expressions of power and resistance, relegation and recuperation, circulate and inhere in all spaces” [6] (pp. 465, 480). Simultaneously, unused urban places are important in the contemporary urbanization models [26] claiming attention in the present scholarly debates under the new capitalist rules and more involvement of local governments in the local urban development in the postsocialist economic contexts [27].

Ruins are products of postsocialist economic transformations that, fundamentally, dramatically, and unevenly, changed the postsocialist communities [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. In the process of postsocialist urban regeneration, the cities from Central and Eastern European Countries went through different stages in their readjustment to the new market-oriented economies. As a result of the postsocialist economic restructuring, some decayed urban places of these cities were partly or completely (re)developed under renewal policies, while other urban sites and industrial districts remained derelict, thus, portraying different stages of urban regeneration [43,44]. Derelict areas expose the local authorities’ neglect or the absence of restoration strategies and policies on the local political agendas in urban postsocialist planning, and the tensions between centralized management and local decentralization, with the state being a “product of antagonisms” [45] (p. 84), and a “sum of multiple divergent projects, rather than a coherent actor” [46] (p. 281). However, urban ruins in the Romanian cities appear as places of indifference during the transition from the centrally planned economy to a post-90 economic capitalism, empowered by globalization, neoliberal rules, and private capitals [21,47,48,49,50]. The material existence of the urban ruins shows the difficulties of economic transition, the spatial inequalities of capitalism [51], controversial actions, and real estate speculation [52]. Furthermore, as Beesley [53] argued, corruption as a feature of the present globalization with multiple and deeply rooted causes in post-90 economic development, generated significant consequences in the local urban regeneration process. The absence of vision in the national policies, with wrong interventions and mismanagement in the postsocialist urban planning regulations, are important contributors in generating urban dereliction in the Romanian postsocialist towns.

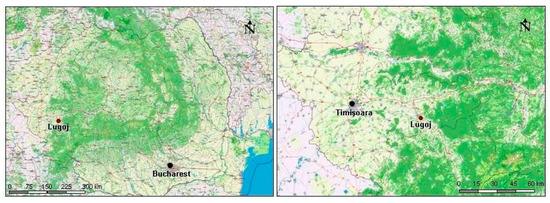

Considering postsocialist formation of the urban landscapes on specific cities and towns, and their neoliberal landscapes of deception [50,54], this paper confirms the recent knowledge, focusing on the Romanian urban dereliction, through a particular local case study on a former state-socialist, nonmetropolitan industrial town: The municipality of Lugoj. The core argument of this sample evolves from the little attention paid to the Romanian small and medium-sized municipalities, with 52.55% of the urban population living in nonmetropolitan areas [55]. The analysis brings to the fore the fact that Lugoj is a third-tier city with de-/reindustrialization and ruin production, generating particular landscapes [56]. This is because nonmetropolitan areas and medium-sized municipalities very often benefited from small interventions, small attention from governments, and little interest for researchers, but generated big opportunities for controversial actions. This could lead to a particular understanding of the understudied or misunderstood piece of knowledge on the topic, with the opportunity to develop new local policies in urban regeneration.

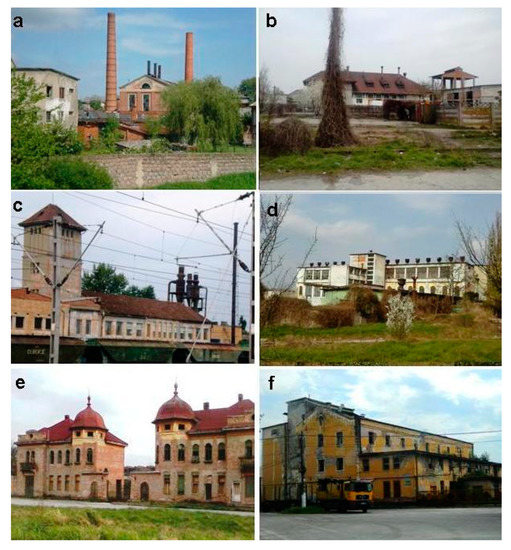

Lugoj was selected for this case study because of its old industrial traditions. Products made in Lugoj’s emblematic factories and workshops were sold in Romania and across Europe. Now, three decades after the breakdown of state-socialism, many of these former factories remain in ruins with no further opportunities to be repurposed or redeveloped. Following trends across Europe for capitalist development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Lugoj’s industry included important manufactures, which provided goods throughout the Austro-Hungarian Empire and acted as a magnet for migration through ample job opportunities. During the state-socialist period, capitalist factories were re-industrialized and nationalized, resulting in a massive surge in industrialization. Lugoj was an emblematic town in the light industry sector, especially well known for its textiles that concentrated female workers. With the socialist heavy industry, this largely female local labor force would be balanced with male laborers brought in to work for the new industrial plants. Postsocialist de-industrialization completely altered the industrial heritage of the town with changing trajectories of its economic and urban geographies. In this process, all of Lugoj’s flagship factories failed. As their production ended they began their decay into marginalized and abandoned places. Three decades after state-socialism’s collapse, these ruins still remain in the local urban landscape as blights in need of attention for regeneration. Although metropolitan and other larger cities tended to have a faster pace of regeneration for their declined places, second-tier and third-tier towns lag behind in their local renewal [56,57].

This study provides critical insight into the shifting landscapes of postsocialist local economic changes tracing the transformation in the local urban patterns associated with the post-90 restructuring and urban ruins, because ruins cannot be left alone to “simply exist in their mute materiality” [58] (p. 692). Furthermore, it is important to understand the manner in which people live with ruins [59], the ways which local governments manage or cope with urban dereliction and how the ruins alter the urban functionality and broader landscapes. Our research raises the issues of recapitalizing these ruins as parts of postsocialist dereliction. Since ruins are often symbolic sites, with important meanings, relating the past with the present urban policies, they are important for our understanding of the circumstances of their abandonment, demolishment, and regeneration, through national and local policies [52] and their “potential directions for future forms of sociality” [13] (p. 1102).

While “transformation of unused urban space follows a global trend” of urban governance [26] (p. 49), experiences of advanced societies, remain less applied in Romania, with ruins standing neglected by the local development agendas. Why and how did the ruins appear in the Romanian cities? What types of ruins appeared? What claim does the voice of the local community have towards ruins and urban dereliction? To what extent do urban ruins alter the inner patterns of the cities and towns? All these are the questions on which this study focuses. To analyze the topics of Romanian urban dereliction, the study proceeds in a few sections. The first concerns the theoretical background of urban ruins, setting the scene for the empirical research, while the second presents research methodology. In the third section, the article focuses on the urban dereliction, including a general overview on the Romanian cities, and the specific sampled case study; the section then explains the rising, the presence, and the consequences of ruined places in the local community. The final part frames the conclusions, outlooks, and some tailor-made recommendations, reflective and applicable for all Romanian nonmetropolitan areas, since urban dereliction appeared as a common feature in the most Romanian urban settlements.

2. Setting Theoretical Background on Urban Dereliction and Ruins

The issue of urban ruins and derelict places is topical and complex within the recent uneven geographies of postsocialism [6,7,8,9,60,61,62]. Oftentimes, studies approach ruins to understand their formation, their sense and their (un)identity in the cities. As “debris of global capitalism” [12] (p. 1037), ruins illustrate the nothingness of order [63] being residual and unproductive sites. Considering ruins as “symbols of failure and abandonment” showing “municipal indifference and social stagnation” [6,8] (p. 475, p. 165), they unveil the mirage of the current capitalism, and neoliberalism as a way of progress, thus, influencing the urban political programs [47,64]. Between creative and brutal destruction [65,66], ruins are collapsed spaces “in a pool of dust, regrets and corruption” [18,20,67] (p. 241), with the latter fuelled by the present globalization [53]. Against such a background, the ruins provide tangible experiences of the past in the current material world and the future [68,69]. Ruins are dead, awkward, loose, and derelict spaces [70,71], where nothing happens. Conceptualized as null places, drosscapes, or urban interstices [72,73,74], urban derelict areas are previously developed industrial or nonindustrial sites that are now vacant, abandoned, or under-used, with opportunities for their further redevelopment [26,75,76]. In line with ruins production, urban dereliction appears as “process” and “object” [77] (p. 6). The process of dereliction, which is fuelled by political and economic changes [26], by the state-socialist industry decline, and by dismantled state-socialist ideologies related to the economic development of the states [16,20,78]. As objects, ruins are part of the ignorance of the local postsocialist governments, unveiling local mismanagement in urban regeneration.

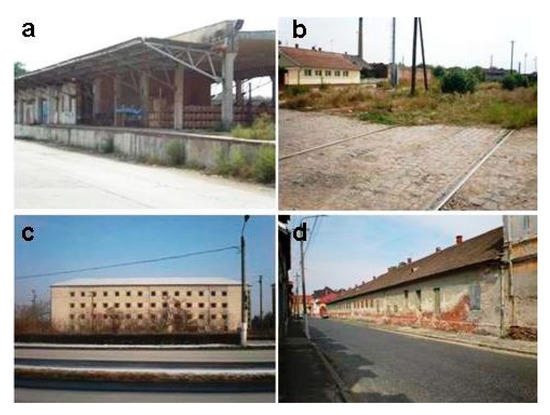

Consequently, derelict places appeared as ruined and abandoned factories. Related industrial or nonindustrial facilities appeared also as ruined sites in the cities [2,76,79,80,81]. Urban dereliction is obvious in vacant military sites, in urban wastelands places, in blank areas, in ruined rail places, and in collapsed buildings in residential districts [79,82,83,84,85]. All these are connected to the historical, social-economic, and political contexts that appeared in Romania, under the postsocialist umbrella of transition from the state-socialist policies to a global market economy and neoliberal policies [49,86,87]. Dereliction reveals negative relations and tensions between de-/reindustrialization and the post-90 market reforms [48], and between centralized state power and local government decentralization. These tensions in urban governance are responsible for the production of the local urban dereliction of the medium-sized towns. They had to face multiple changes, consequences, and opportunities. While some towns that relied on a particular heavy industry encountered massive declines, shrank, and even collapsed after they closed, some small-sized towns with complementary industrial branches closely related to old manufacturing traditions had the chance to survive urban dereliction and spark local processes of de-/reindustrialization.

3. Data, Materials, and Methods

To explain the Romanian urban dereliction, multiple data sources and methods were used all through this study. A mixed-method approach and a combination of data gathering, based on the history of the sites and interviews with local residents, city planners, and stakeholders to propose solutions to the city’s problems, were helpful in investigating the local urban dereliction. The starting point of the research as Mah [1] suggests was an infield, participatory, and ethnographic observation of ruins in different Romanian cities and in a sampled site investigated in-depth. Empirical sources include: (1) Primary literature review, media analysis—press and documentaries, from national to local [88] and old monographs of the former productive state-socialist factories; (2) The authors’ direct experience [89] of ruins, and infield and participatory observation, with investigated sites repeatedly visited, between 2012 and 2019, were useful in gaining important accounts on ruins’ reproduction under post-90 economic changes at the local level; (3) Since statistical data on ruins are unavailable, an ethnographic approach to ruins were used, together with first-person accounts of places analysis [12]; (4) Qualitative research was conducted based on interviews, personal conversations and talks with local key actors in the local government, residents and ex-workers in ruined factories (fifteen in each study area); (5) An in-depth analysis of a case study with specific investigated sites was considered; (6) To assess the local urban dereliction, an inventory of the ruined sites was made, categorizing the various urban derelict places; (7) Empirical data provided meaningful insights in understanding the postsocialist reproduction of ruins and the local ways of life of residents in/with those derelict places.

To investigate the general background of the processes that led to Romania’s urban ruins, media analysis was used including newspapers, magazines, and three documentaries from Romanian national television. Understanding the production of ruins was informed by participant observation in large cities (Timişoara, Braşov, Craiova, and Bucharest) and medium- and small-sized towns (Făgăraş, Buziaş, Făget, Ilia, Azuga etc.). The study builds on previous research on postsocialist derelict spaces conducted by the co-authors in addition to a thorough literature review.

Against this general context, the municipality of Lugoj was selected as a case study to find out the specificities of its urban dereliction, but also the similarities with other small- and medium-sized municipalities. Regarding the selected case-study, the municipality of Lugoj (a nonmetropolitan area) was sampled, because one of the authors live in this town, witnessing the local urban degradation and the emergence of different derelict places and wondering how long these ruins will continue to exist in their ‘mute materiality’ [58] (p. 692). These former productive state-socialist sites are ghosts of a community’s heritage [9], confirming that 30 years after the state-socialism collapse, they are still present and, as Schönle [58] observed, it is important to know how long from now on these ruins will be ignored, with local authorities doing nothing. To understand the issues of local ruins and urban regeneration programs, an in-depth interview was conducted with the director of Urban Planning Directorate from the City Hall of Lugoj. Then, three interviews were conducted with three former directors/managers of the local flagship factories to understand the local decline of the industrial plants from the inside. These interviews represent valuable proof on the entire process of dereliction from the standpoint of the actors involved in the process before and after the decline of the facilities. In addition, discussions, personal conversations, and oral histories of local residents were useful to capture the local residents’ perception of these ruined and abandoned sites. In this regard, two lines of questioning were followed. On one hand, we were interested in how the former workers living in the neighborhoods of the ruined sites perceived ruins and if they affectively identity themselves with these abandoned places. On the other hand, we extended our inquiry to the pragmatic position of the residents as persons who only live in the proximity of ruined sites without any emotional attachment. To determine this, we addressed the question related to life quality in these areas. The types of data collected in relation to the particular investigated places are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details on the qualitative methods used in the sampled case study analysis.

Useful photographs, repeatedly taken [90] in the ruin research, related to the results of qualitative research in urban areas, triangulate the findings of the study. In all, the recommended methodology on urban ruin research [1,2,6,8] was followed to understand the (re)production of urban derelict places, their main consequences as well as their social and cultural implications in the local community.

5. Conclusions

Considering different impacts of postsocialist changes in Romania [132], the paper discussed the issue of Romanian postsocialist urban dereliction, with a nonmetropolitan area as a case study, explaining how the city’s government mismanagement on postsocialist economic transition led to the cities’ derelict places. The research portrayed the perspectives of the municipality, presumably driven by growth discourses, of the local residents and of the ex-workers, accusing them of faulty privatization and urban mismanagement in local regeneration. Such an approach pinpoints tension and the conflicting interests of involved actors, in the local ruins production [18]. The article has shown that, similarly to other European urban settlements, the (re)reproduction of urban dereliction, as a consequence of the new postsocialist economic rules in urban restructuring, is a common feature in the process of the Romanian postsocialist urban identity formation. They occurred in the post-90 economic decline and urban restructuring, governed by the global capitalism [12,18], and wrong privatization, illustrating the illusions of the progress [6] in the local urban planning. Although in other Eastern European Countries, some derelict and ruined sites were restored [7,44], in Romanian cities and towns, the ruins still stand as proofs of the transition to a market economy. Against such a background, the national context of de-/reindustrialization, demilitarization, and postsocialist shifts in urban restructuring, framed by mismanagement in urban and economic restructuring and in postsocialist urban regeneration, is the main contributor to the present urban dereliction. Whether they are industrial, residential, rail, or military ruined sites, they are consequences of deliberate interventions managed by different local, regional, or national actors, stakeholders and policies, with speculative actions in the context of urban restructuring. In addition, urban mismanagement accompanied by ignorance of local communities led to the urban dereliction with urban ruins remaining spaces of indifference [18]. For that reason, this topic remains a “slippery subject” [6] (p. 467), grounded in the scene of post-90 politics and economic transformations.

Urban derelict places, 30 years after the state-socialism collapse, are ubiquitous scenes in the Romanian cities and towns, illustrating ignorance, failure, and abandonment. Many urban ruins appeared due to the post-socialist industrial decline, framed by the new market economy. Against such a background, both the former state-socialist plants and the traditional factories with importance for the national culture, failed. The national and local industrial decline turned into derelict places, swirling other related places and damaging the inner patterns of the cities. Rail transport areas were the first, because of their close relationship with the former state-socialist industries. Places of residential districts turned to ruins because of their state-socialist design, only to reproduce the working class [93]. During postsocialism the people living in these districts became the owners of the flats and were associated with the home improvement actions, the old state-socialist infrastructure became redundant and turned to ruins. Demilitarization of Romanian urban areas was another driving force in the urban dereliction appearance. The case developed in this narrative is applicable to Romanian nonmetropolitan areas and to the municipality of Lugoj. The local industrial restructuring generated many derelict places, with important traditional plants for the national culture that was turned to ruins [123].

The findings of the study illustrate conflicting postures between the voice of the local community and the local government arguments. On one hand, there are voices blaming the local government’s indifference, at periods when the town needs important interventions in local regeneration. On the other hand, local government shifts the responsibility to the new owners of the current derelict sites, and for those ruined places under the state’s ownership, motivating the absence of the financial resources. However, this argument contrasts with the postsocialist opportunity in using the EU funding programs in local urban development. Such projects could regenerate the ruined sites, especially those with cultural significance for the local and national culture. Meanwhile, totally blaming one another, the local community remains the main victim. Besides theoretical projects, strategies and large aspirations of the local government in urban regeneration, [133], many important sites remain abandoned with their ruins harming the local community. Furthermore, the tensions between the local decentralized ambitions on urban development and the centralized management on urban postsocialist planning, maintain local urban dereliction. Therefore, the Romanian urban decentralization in local policies is rather theoretic with no positive feedbacks.

Thirty years since the Romanian state-socialism collapse, it is a time of reflection on what needs to be done to adjust the Romanian urban communities to the European urban welfare. Consequently, this study calls for both urban regeneration (because ruins could still be restored, serving the local community and its culture), and for further fertile research in the field. Such derelict places and their related decayed neighborhoods are common features in the locally ruined sites. Such groups and species pushed toward such marginal spaces generate usage and activities that deserve to be further studied in their own rights. Assessing local urban dereliction, and an in-depth analysis of its damages in the local community connected to the above mentioned issues, studying the risk potential of urban ruins [123], and applying for EU funds in local urban development, are actions in the local urban regeneration that have to be immediately kick-started, for timely recuperation of urban dereliction. Apportioning blame on the former state-socialism with artificial industrialization, and the current postsocialism governed by speculations, corruption, wrong interventions, and policies [18] without sustainable visions is not enough. Now it is time for sustainable action for the cities’ benefit, for their culture and to their postsocialist identity formation [134]. The past could be blamed, but not destroyed. Does the past have any future in the further postsocialist urban identity formation? If yes, it is time to act before destroying the local urban identities. In other words, 30 years after the state-socialism collapse is a worthy time for good reflections and critical research on further urban regeneration strategies, in order to solve the current urban dereliction. In doing so, as Jayne (2012) [4] argued, the local government and the current public–private actors in urban development, have to (re)design more progressive alternatives and politics on the local agendas, regarding the capitalization of the local urban ruins. After two decades of postsocialist urban change, the urban ruins unveil the ignorance of national and local governments and communities, being places of failure and abandonment.

Finally, the article highlighted that urban ruins are still a common feature in Romania. Urban dereliction and their related ruins in urban space are results of the present capitalist expansion, relating to uneven geography of capitalist development [135]. Although ruins are “never static objects” [58] (p. 3) this contribution showed that Romanian postsocialist urban dereliction and the local urban ruins are—three decades after the state-socialism collapse—quiescent spaces both in the face of the post-1990s capitalist development, and of the local municipal ignorance of the contemporary Europeanization trends on urban sustainability, from which we all have to learn.

Author Contributions

The authors of this article have equal contribution. Conceptualization I.S.J. and S.V.; methodology I.S.J. and S.V.; investigation I.S.J. and S.V.; data creation I.S.J.; writing original draft preparation I.S.J. and S.V.; writing review and editing S.V. and I.S.J.; visualization and supervision S.V.; funding acquisition I.S.J. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. Parts of the findings and results of this study have been presented by the authors at the 6th International Urban Geographies of Post-Communist States Conference 25 Years of Urban Change, CATference 23–26 September 2015, Prague, Czech Republic. Title of the presentation: Living in/with dereliction: The case of small and medium sized towns in Timis County, Romania. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC fee for this article is funded by the Project CNFIS-FDI-2020-0253, West University of Timisoara.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their thanks to: West University of Timisoara, DCSCU, Romania for the APC fee support; the anonymous reviewers for their comments on the earlier manuscript and to Margareta Lelea, for the last proofreading of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- Mah, A. Memory, uncertainty and industrial ruination: Walker riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2010, 34, 398–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, A. Industrial Ruination, Community and Place Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Turok, I. Redundant and marginalized spaces. In Cities and Economic Change; Paddison, R., Hutton, T., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 2015; pp. 74–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jayne, M. Mayors and urban governance: Discursive power, identity and local politics. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2012, 13, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, S.; Lobato, I.R. Social exclusion: Continuities and discontinuities in explaining local patterns. Local Econ. 2015, 30, 765–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeSilvey, C.; Edensor, T. Reckoning with ruins. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 465–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilov, K. (Ed.) The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, T. Industrial Ruins. Space, Aesthetics and Materiality; Berg: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Edensor, T. The ghosts of industrial ruins: Ordering and disordering memory in excessive space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2005, 23, 829–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. From derelict industrial areas towards multifunctional landscapes and urban renaissance. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2007, 3, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. Sustainable Reclamation of Industrial Areas in Urban Landscapes; Wit Press: Southampton, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. Introduction: Towards a political understanding of new ruins. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1037–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Translating space: The politics of ruins, the remote and peripheral places. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strangleman, T.; Mah, A. Industrial Ruination, Community, and Place: Landscapes and Legacies of Urban Decline; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2014; Volume 38, pp. 1126–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck, K.A.; Stevens, Q. Tying down loose space. In Loose Space: Possibility and Diversity in Urban Life; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- González-Ruibal, A. Time to destroy: An archaeology of supermodernity. Curr. Anthropol. 2008, 49, 247–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirt, S.A.; Stanilov, K. Twenty Years of Transition: The Evolution of Urban Planning in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union, 1989–2009; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kideckel, D. Getting by Post-Socialist Romania: Labor, the Body and Working-Class Culture; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kovácz, Z.; Weissner, R.; Zischner, R. Urban renewal in the inner city of Budapest: Gentrification from a postsocialist perspective. Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puşcă, A. Industrial and human ruins of postcommunist Europe. Space Cult. 2010, 13, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.; Timár, J. Uneven transformations: Space, economy and society 20 years after the collapse of state-socialism. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2010, 17, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L. New socio-spatial formations: Places of residential segregation and separation, Czechia. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 2009, 100, 417–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sýkora, L. Post-socialist cities. In International Encyclopedia of Human Geography; Kitchin, R., Thrift, N., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Stanilov, K.; Sýkora, L. Planning markets and patterns of residential growth in post-socialist metropolitan Prague. J. Archit. Plan. Res. 2012, 29, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.; Kaczmarek, S. The socialist past and postsocialist urban identity in Central and Eastern Europe: The case of Łódź, Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2008, 15, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefs, M. Unused urban space: Conservation or transformation? Polemics about the future of urban wastelands and abandoned buildings. City Time 2006, 2, 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, A.C.; Barros, M.J. Local municipalities’ involvement in promoting the internationalisation of SMEs. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M.J.; Stenning, A.C. (Eds.) East Central Europe and the Former Soviet Union: The Post Socialist Economies; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dunford, M.; Smith, A. Catching up or falling behind? Economic performance and regional trajectories in the ‘New Europe’. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 76, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.; Young, C. Reconfiguring socialist urban landscapes: The’left-over’ of state-socialism in Bucharest. Hum. Geogr. J. Stud. Res. Hum. Geogr. 2010, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Marcińczak, S.; Sagan, I. The socio-spatial restructuring of Łódź, Poland. Urban Stud. 2011, 48, 1789–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S. The evolution of spatial patterns of residential segregation in Central European Cities: The Łódź functional urban region from mature socialism to mature post-socialism. Cities 2012, 29, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Musterd, S.; Stepniak, M. Where the grass is greener: Social segregation in three major Polish cities at the beginning of the 21st Century. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2012, 19, 383–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcińczak, S.; Gentile, M.; Rufat, S.; Chelcea, L. Urban geographies of hesitant transition: Tracing socioeconomic segregation in Post-Ceausescu Bucharest. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1399–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nădejde, Ş.; Pantea, D.; Dumitrache, A.; Braulete, I. Romania: Consequences of small steps policy. In Rise and Decline of Industry in Central and Eastern Europe. A Comparative Study of Cities and Regions in Eleven Countries; Muller, B., Finka, M., Lintz, G., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Pickles, J. The spirit of post-socialism: Common spaces and the production of diversity. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2010, 17, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenning, A. Placing (post-) socialism. The making and remaking of Nowa Huta, Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2000, 7, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenning, A.; Smith, A.; Rochovská, A.; Swiatek, D. Domesticating Neoliberalism: Spaces of Economic Practice and Social Reproduction in Post-Socialist Cities; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chelcea, L. Bucureştiul Postindustrial, Memorie, Dezindustrializare şi Regenerare Urbană; Polirom: Bucharest, Romania, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Iancu, S. Ruine Industriale ale Epocii de Aur (industrial ruins of the golden age). România Liberă. 28 May 2007. Available online: http://www.romanialibera.ro/actualitate/fapt-divers/ruine-industriale-epocii-de-aur-96496 (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Ivanov, C. Cum pot fi Transformate Ruinele Industriale în Minuni Arhitecturale (How Industrial Ruins Could Turn to Architecture Wonderlands). 29 November 2010. HotNews.ro. Available online: http://economie.hotnews.ro/stiri-imobiliar-8079922-cum-pot-transformate-ruinele-industriale-bijuterii-arhitectonice.htm (accessed on 12 July 2018).

- Kiss, E. Restructuring in the industrial areas of Budapest in the period of transition. Urban Stud. 2002, 39, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E. Spatial impacts of post-socialist industrial transformation in the major Hungarian cities. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2004, 11, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, E. The evolution of industrial areas in Budapest after 1989. In The Post-Socialist City: Urban Form and Space Transformations in Central and Eastern Europe after Socialism; Stanilov, K., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The state and society. In State, Space, World: Selected Essays by Henri Lefebvre; Brenner, N., Elden, S., Eds.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2009; pp. 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Chelcea, L. The ‘Housing Question’ and the state-socialist answer: City, class and state remaking in 1950s Bucharest. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2012, 36, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, J.D. Rescuing critique: On the ghetto photography of Camilo Vergara. Theory. Cult. Soc. 2008, 25, 285–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mickiewicz, T.; Zalewska, A. Deindustrialization. Lessons from the Structural Outcomes of Post-Communist Transition; Working Paper 463; William Davidson Institute: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Muir, J. Neoliberalising a divided society? The regeneration of Crumlin Road Gaoland and Girdwood Park, North Belfast. Local Econ. 2014, 29, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, B.; Mitchell, D. Neoliberal landscapes of deception: Detroit, Ford Field and the Ford Motor Company. Urban Geogr. 2004, 25, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golubchikov, O.; Badyina, A.; Makhrova, A. The hybrid spatialities of transition: Capitalism, legacy and uneven urban economic restructuring. Urban Stud. 2013, 51, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. The political economy of urban ruins: Redeveloping Shanghai. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1081–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beesley, C. Globalization and corruption in post-Soviet countries: Perverse effects of economic openness. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2015, 56, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D. Cultural Geography: A Critical Introduction; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- NIS. National Institute of Statistics of Romania, Bucharest. 2015. Online Database TempoOnline. Available online: www.tempoonline.ro (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- Jucu, I.S. Romanian post-socialist industrial restructuring at the local scale: Evidence of simultaneous processes of de-/reindustrialization in the lugoj municipality of Romania. J. Balk. Near East. Stud. 2015, 17, 408–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jucu, I.S. Lugoj the municipality of seven women to a man. From myth to post socialist reality. An. Univ. Vest Timis. Ser. Geogr. 2009, 19, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schönle, A. Ruins and history: Observations on Russian approaches to destruction and decay. Slav. Rev. 2006, 65, 649–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, A.L. Imperial debris: Reflections on ruins and ruination. Cult. Anthropol. 2008, 23, 191–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto, M.; Brito, M. Aparecida de. os Vazios Urbanos e o Processo de Redefinição Socioespacial em Dourados. (Assessing Urban Processes of Spatial Redefining); MS. UFMS: Campo Grande, Brazil, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Millington, N. Post-industrial imaginaries: Nature, representation and ruin in Detroit, Michigan. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voiculescu, S.; Jucu, I.S. Producing urban industrial derelict places: The Case of the Solventul petrochemical plant in Timişoara. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2016, 23, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somers-Hall, H. The concept of ruin: Sartre and the existential city. Urbis Res. Forum 2009, 1, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Theodore, N.; Peck, J. Framing neoliberal urbanism: Translating ‘Commonsense’ urban policy across the OECD Zone. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2011, 19, 20–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Theodore, N. Neoliberalism and the Urban Condition. City 2005, 9, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Zanocea, C. Singur pe Ruinele Industriei Comuniste. (Alone on the Communist Ruins). 4 February 2014. Ziarul de Roman. Available online: http://www.ziarulderoman.ro/singur-pe-ruinele-industriei-comuniste/ (accessed on 20 July 2018).

- Boym, S. Ruins of the avant-garde: From Tatlin’s tower to paper architecture. In Ruins of Modernity; Hell, J., Schönle, A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010; pp. 58–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tonnelat, S. ‘Out of frame’: The (in) visible life of urban interstice. Ethnography 2008, 9, 291–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J. Everyday afterlife: Walter Benjamin and the politics of abandonment in Saskatchewan, Canada. Cult. Stud. 2011, 25, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, G. The dead zone and the architecture of transgression city: Analysis of urban trends. City 2000, 4, 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. Exploring the creative possibilities of awkward space in the city. J. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 83, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, A.; Tylecote, M. Ambivalent landscapes—wilderness in the urban interstices. Landsc. Res. 2007, 32, 443–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A. Drosscape: Wasting Land in Urban America; Architectural Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bagaeen, S. Redeveloping former military sites: Competitiveness, urban sustainability and public participation. Cities 2006, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barndt, K. Memory Traces of an Abandoned set of Futures Dustrial Ruins in the Post-Industrial landscapes of East and West Germany. In Ruins of Modernity; Hell, J., Schönle, A., Eds.; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2007; pp. 270–293. [Google Scholar]

- Hell, J.; Schönle, A. (Eds.) Ruins of Modernity; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lahusen, T. Decay or endurance? The ruins of socialism. Slav. Rev. 2006, 65, 736–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristiaanse, K. The City as a Loft; Berlin: Top 38; ETH Zurich: Berlin, Germany.

- Loures, L.; Horta, D.; Panagopoulos, T. Strategies to reclaim derelict industrial areas. WSEAS Environ. Dev. 2006, 5, 599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Unt, A.L.; Travlou, P.; Bell, S. Blank space: Exploring the sublime qualities of urban wilderness at the former fishing harbor in Tallinn, Estonia. Landsc. Res. 2014, 39, 267–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S. Military landscapes and secret science: The case of Orford Ness. Cult. Geogr. 2008, 15, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farley, P.; Roberts, M.S. Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness; Jonathan Cape: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, B. Infrastructure and indeterminacy: The production of residual space. In Proceedings of the CRESC Conference ‘Framing the City’, Manchester, UK, 6–9 September 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qviström, M. Network ruins and green structure development: An attempt to trace relational spaces of a railway ruin. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadolu, B.; Lucheş, D.; Dincă, M. The patterns of depopulation in Timişoara—Research note. Sociol. Românescă SR 2011, 9, 76–89. [Google Scholar]

- Nadolu, B.; Dincă, M.; Lucheş, D. Urban Shrinkage in Timişoara, Romania; Research Report; West University of Timişoara: Timisoara, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger, M.H. Media tools for urban design. In Companion to Urban Design; Banerjee, T., Loukaitou-Sideris, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- Rossiter, W.; Price, L. Local economic strategy development under Regional Development Agencies and Local Enterprise Partnership. Applying the lens of the multiple streams framework. Local Econ. 2013, 28, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S. Rising from the Ruins. The Aestheticization of Detroit’s Industrial Landscape; Lewis and Clark College: Portland, OR, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andreşoiu, B.; Bonciocat, Ş.; Ioan, A.; Oţoiu, N.A.; Chelcea, L.; Simion, G. Kombinat. Ruine Industriale ale Epocii de Aur; Igloo Patrimoniu: Bucharest, Romania, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P. Regional identities and regionalization in East Central Europe. Post Sov. Geogr. Econ. 2001, 42, 235–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovici, N. Workers and the city: Rethinking the geographies of power in post-socialist urbanization. Urban Stud. 2012, 49, 2377–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesalon, L.; Cretan, R. “Little Vienna” or “European avant-garde city”? Branding narratives in a Romanian City. J. Urban Reg. Anal. 2019, 11, 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Cojocar, A.; Industria Trece Printr-un val de Inchideri care Afecteaza Cresterea Economica. Care sunt Cauzele Dezindustrializarii de dupa 89 si unde s-a gresit? Am Privatizat Destul sau Prea Putin? De ce nu am Atras Destui noi Investitori? Ziarul Financiar. 7 March 2013. Available online: https://www.zf.ro/analiza/industria-trece-printr-val-inchideri-afecteaza-cresterea-economica-cauzele-dezindustrializarii-dupa-89-unde-s-gresit-privatizat-destul-prea-putin-atras-destui-investitori-10648895 (accessed on 10 August 2018).

- Creţan, R.; O’Brien, T. Corruption and conflagration: (in) justice and protest in Bucharest after the Colectiv fire. Urban Geogr. 2020, 41, 368–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preda, C.C. Ministerul Economiei Caută Potenţialul Nevalorificat Printre Ruinele Industriei, Ziarul Hunedoreanului. 2013. Available online: http://zhd.ro/ministerul-economiei-cauta-potentialul-nevalorificat-printre-ruinele-industriei (accessed on 6 June 2018).

- DIGI 24. Business Club. Industria Sticlei în România în ruine. Ultima Suflare a Sticlei de Pădurea Neagră. 2014. Available online: http://www.digi24.ro/Stiri/Digi24/Economie/Stiri/BUSINESS+CLUB+Industria+sticlei+din+Romania+in+ruine+Ultima+suflonline (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Deșteptarea. Prin Ruinele Industriei Băcăuane. 2013. Available online: athttp://www.desteptarea.ro/prin-ruinele-industriei-bacauane/ (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Kotz, D.M. Globalization and neoliberalism. Rethink. Marx. 2002, 14, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soederberg, S. The Politics of New Financial Architecture: Re-Imposing Neoliberal Domination in the Global South; Zed Books: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein, M.A. What happened in East European (political) economies?: A balance sheet for neoliberal reform. East Eur. Politics Soc. 2009, 23, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickles, J.; Smith, A. (Eds.) Theorising Transition: The Political Economy of Postcommunist Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Avram, C. În Premieră (In First Run). 2014. Available online: http://www.antena3.ro/romania/romania-otravita-ruinele-industriei-comuniste-ne-baga-in-pamant-cu-trei-ani-mai-devreme-230163.html (accessed on 10 June 2016).

- Dochia, A. Despre Soarta Tristă a Industriei Chimice Româneşti. Ziarul Financiar. 2012. Available online: http://www.zf.ro/opinii/despre-soarta-trista-a-industriei-chimice-romanesti (accessed on 21 October 2018).

- Ianoş, I. Dinamică Urbană; Tehnică: Bucharest, Romania, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ianoş, I.; Heller, W. Spaţiu, Economie şi Sisteme de Aşezări; Tehnică: Bucharest, Romania, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jigoria, L.; Popa, N. Industrial brownfields: An unsolved problem in post-socialist cities. A comparison between two mono-industrial cities: Resita (Romania) and Pancevo (Serbia). Urban Stud. 2016, 54, 2719–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dima, A. România te Iubesc. Available online: http://romaniateiubesc.stirileprotv.ro/stiri/romania-te-iubesc/romania-te-iubesc-industria-romaneasca-marire-si-decadere.html (accessed on 10 June 2015).

- Savu, C. Cine a pus ARO pe butuci. In România te Iubesc; Herlo, P., Năstase, R., Dima, A., Savu, C., Angelescu, P., Eds.; Humanitas: Bucharest, Romania, 2018; pp. 210–229. [Google Scholar]

- Domanski, B. Industrial change and foreign direct investments in the post socialist economy: The case of Poland. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2003, 10, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gafiuc, J. Platforma Iadului. Rulmentul Brasov pe Vremuri Mandria Socialismului a Devenit o ruină. 23. Libertatea, Iunie. 2019. Available online: https://www.libertatea.ro/stiri/platforma-iadului-cum-arata-azi-rulmentul-brasov-mandria-socialismului-romanesc-2673705 (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Chowdhury, S.; Kain, J.H.; Adelfio, M.; Volkhko, Y.; Norrman, J. Greening the brown. A bio-based land-use framework for analyzing the potential of urban brownfields in an urban circular economy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamju, M. Magneții s-au Întors pe Ruinele Fostelor Platforme Industrial. Actualitate. Mesagerul hunedorean, Hunedoara. 2013. Available online: https://www.mesagerulhunedorean.ro/magnetii-s-au-intors-pe-ruinele-fostelor-platforme-industriale (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- National Institute of Statistics Romania (NIS). Breviar Statistic al Municipiului Lugoj, 2009–2010; NIS: Timisoara, Romania, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jucu, I.S. Analiza Procesului de Restructurare Urbană în Municipiul Lugoj; Universităţii de Vest: Timisoara, Romania, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wẹc1awowicz, G. From egalitarian cities in theory to non-egalitarian cities in practice: The changing social and spatial patterns in Polish cities. In Of States and Cities: The Partitioning of Urban Space; Marcuse, P., van Kempen, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 183–199. [Google Scholar]

- Egresi, I. Foreign direct investment in a recent entrant to the EU. The case of the automotive industry in Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2007, 45, 134–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariş, C. Unde e textila de altă dată? Actualitatea 2010, 708, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Toma, D. În prag de sărbători locuitorii din Mondial se luptă cu frigul şi foamea (In winter the inhabitants of Mondial face with cold and hungry). Actualitatea 2013, 1176, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Niţoiu, C. Fabrica de lapte din Lugoj cumpărată de fiica fostului director CFR Timişoara. Redeşteptarea 2007, 1180, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gaidoş, C.O. Complexul industrial Abatorul şi Fabrica de gheaţă 1911–1912. Monitorul de Lugoj 2005, 77, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jucu, I.S.; Pavel, S. Post-communist urban ecologies of Romanian medium-sized towns. Forum Geogr. 2019, 18, 170–185. [Google Scholar]

- Dawidson, K.E. Redistribution of land in post-communist Romania. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2005, 46, 618–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiv, N. Beating the Bounds: A Walking Exploration of the Capital Corridor Rail Line. 2011. Available online: http://beatingthebounds.typepad.com (accessed on 15 March 2018).

- Hananel, R. Can centralization, decentralization and welfare go together?: The case of Massachusetts affordable housing policy (Ch. 40B). Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 2487–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opris, P. Rachete Balistice Sovietice in Romania (1961–1998). 2018. Available online: https://www.contributors.ro/rachete-balistice-sovietice-in-romania-1961-1998-2/ (accessed on 25 July 2019).

- Lugoj Tion. La Lugoj se Inființează un nou Cartier Militari. 22 June 2011. Available online: https://www.tion.ro/lugoj/la-lugoj-se-infiinteaza-un-nou-cartier-militari-342246/ (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Obeadă, C. Cele mai Multe clădiri Emblem ale Lugojului Sunt în Ruină de ani de zile. Redeșteptarea. 18 June 2013. Available online: https://redesteptarea.ro/galerie-foto-cele-mai-multe-cldiri-emblem-ale-lugojului-sunt-in-ruin-de-ani-de-zile/ (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Creţan, R. Mapping protests against dog culling in post-communist Romania. Area 2015, 47, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandi, M. Urban nature and ecological imaginary. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Imaginaries; Lindner, C., Meissner, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Matichescu, M.L.; Drăgan, A.; Lucheș, D. Channels to West: Exploring the Migration Routes between Romania and France. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1861. [Google Scholar]

- City Hall of the Municipality of Lugoj. The Strategy of Urban Development of the Municipality of Lugoj; Nagard: Lugoj, Romania, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ilovan, O.R.; Jordan, P.; Havady-Nagy, K.X.; Zametter, T. Identity matters for development. Austrian and Romanian experiences. Transylvanian Rev. 2016, 25, 261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Neoliberalization: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development; Franz Steiner Verlag: Munich, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).