Abstract

MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Exhibitions/Events) have been established as one of the most important industries. Limited attention, however, has been given to understanding the underlying mechanisms of a sustainable market environment. In order to build such an environment, this research investigates a way to enhance the identity between local businesses and the MICE industry that make up the MICE environment by employing the brand concept in marketing. This study examines the effect of venue name and type of events being exposed on brand formation. The main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between brand identity and the impact on residents’ perceived brand value. The findings of this research suggest that consistent exposure of content-specific brand names and similar types of events increases the identity between local businesses and the MICE industry, and the identity mediates the relationship.

1. Introduction

The Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Exhibitions/Events (MICE) industry has shown continuous growth, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. The MICE industry is expected to continue to grow over the next few decades, and it is one of the fastest-growing sectors in the global tourism industry [].

The MICE industry is recognized to have made an enormous contribution to host destinations in the tourism industry. This is because the MICE industry has inspired community resurgence, economic and cultural growth, as well as the creation and reinforcement of unique destination brands []. The Korean Tourism Organization [] (2016) defined the value of the MICE industry in three ways. First, direct effects include increasing trade volume, playing a major role in the acquisition of foreign currency, and developing the MICE industry. Second, indirect effects entail increases in employment, such as within hotels, distribution and tourism. Third, intangible effects include raising national or city brands and creating new industries. Recently, thus, a great amount of attention and effort has been given to the industry to investigate sustainable strategies, which are an important contributor to a destination’s economic, cultural and social structure []. Previous studies related to “sustainable MICE” have mainly focused on quantitatively analyzing the eco-friendliness, and the economic and social effects of the MICE industry []. However, limited attention has been paid to understanding the underlying mechanism of the sustainability of the MICE. In order to examine what factors contribute to the sustainability of the MICE industry, this research utilizes the concept of social identity theory in building a venue’s brand name.

Globally recognized MICE events such as the CES (Consumer Electronics Show) in Las Vegas, USA, and the MWC (Mobile World Congress) in Barcelona, Spain, have created sustainable success with strong brand identities. However, a large number of MICE events have also failed to create sustainable environments and have disappeared from the market [].

Identity has been considered a fundamental factor for building sustainable market environments in business []. The crucial factor for building a sustainable market is individuals belonging to a business, and pursuing the same goals as them. If residents, merchants and all stakeholders near the MICE venues share similar goals and identities, and if the MICE events are well established based on strong identity, all participants would be motivated to improve the sustainability of the MICE environment. Additionally, the fact that the members of the community share a common identity and similar goals will increase efficiencies in consumption activities. This study focuses on economic and social dimensions rather than on all the dimensions of sustainability [,].

In examining the effect of identity on MICE businesses, this study explores how the implementation of the MICE brand name and events are related to building a brand identity and increasing an individual’s willingness to participate. Further, this study examines the effect of MICE brand names and consistent characteristics of events as factors in increasing identity and an individual’s willingness to participate in MICE events.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. MICE Industry

With the growth of MICE markets in the Asia-Pacific region, the scale of facilities has been getting bigger, with active and aggressive support from governments in terms of building infrastructure and investing large amounts of their budget in marketing [,]. A large portion of previous studies has attempted to identify the factors and characteristics that influence participation in MICE events [], for example, investigated residents’ participation behavior as an important factor for the success of mega-events. They suggested that residents’ interest in athletic events, related to the general characteristics of the businesses, influences the overall engagement behavior in a mega-event. The study also revealed that residents’ positive estimation of the economic, social and cultural impacts influenced their willingness to participate. The results of the study indicated that residents’ positive awareness of the mega event was directly connected to the success of the event. However, this study did not include the important roles of residents toward a MICE event. On the other hand, Kim and Lee [] found that the brand awareness and image of convention centers had a positive impact on the MICE industry. They determined that the brand management of a convention center had an important role in increasing customer satisfaction, which directly influenced the building of a positive and differentiated brand image for the venue. The study was approached from a management perspective. For further strengthening of the image of a venue and building a sustainable MICE environment, it would be ideal if we could strategically endeavor to support a venue’s surrounding communities, including its local community and residents, in order to build a socially-responsible brand image. Building such a brand image is a fundamental component of developing a sustainable MICE industry.

To investigate a way to build sustainable MICE environments, this study included the influence of the identity of residents on the MICE industry, by focusing on the mutual interchange between the MICE industry and residents based on social identity theory.

2.2. Social Identity Theory

Social Identity Theory (SIT) is a broadly used concept in social psychology to describe certain types of intergroup behaviors, perceived from the relevant social group []. More specifically, SIT restores consistency in organizational identification and proposes fruitful effects for organizational behavior []. SIT is related to group situations and begins with the assumption that social identity mainly originates from group membership. It also suggests that people attempt to gain positive social identities, and it stems from a benign comparison made primarily between groups and related groups []. Tajfel defined social identity as “a part of an individual’s self-concept, which is derived from his knowledge of his membership to a social group, together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (p. 63) [].

Positive social identity comes from self-esteem and helps to develop social identity []. The main assumption of SIT is that group biases are motivated by their group and thus by their desire to have a positive outlook. Therefore, it was presumed that there was a causal relationship between group differentiation and self-esteem; Abrams and Hogg, for example, suggested that self-esteem could be enhanced by positive intergroup differentiation []. In addition, the motivation to become a source of positive social identity is to keep the honesty of self-image [], which drives individuals to strive for self-improvement [].

According to SIT, the need for positive self-esteem is met with a positive assessment of their group []. It argues that individuals, in part, identify social categories and strengthen their self-esteem [,]. Confirmation and comparison of social identities suggest that an individual can represent a group’s success and status. In fact, the contrast between positive and negative groups has been shown to affect members’ degrees of self-esteem [,]. An individual’s social identity can be derived not only from organizations but also from work groups, departments, trade unions, lunch groups, age groups, fast track groups, etc. Self-esteem is built in the ingroup, such that people can feel that they belong to their own specific group that share similar goals. Thus, the intergroup similarity is another element that raises social identity.

Identification and group collaboration can build a positive relationship. Shamir suggested that identification positively affects the willingness to contribute to collective work []. A social group is made up of a large number of people who feel that they belong to a certain group and belong to a group of others []. SIT is essentially a theory of distinguishing group differentiation. It is a theory of how group members distinguish their own groups and pursue better performance than outgroups [,].

When people finally feel that they belong to their ingroup, they try to socialize and act in accordance with the organization. These actions also cause the development of social identity. Albert and Whetten argued that organizational members have an identity, as long as there is a common understanding of the core, unique and persistent nature or essence of the organization []. This identity can be adopted among its members and can be reflected in shared values, beliefs, goals, organizational structures and environments. The more distinct and stable the organization’s characteristics are and the more consistent they are internally, the greater the internalization will be [].

In terms of sociology and psychology, numerous reports have concluded that self-esteem, intergroup similarity, and superiority are important factors for the development of social identity. Hence, this study links the MICE industry and social identity in order to understand important factors raising MICE stakeholders’ social identities, which will help to build a sustainable MICE industry.

2.3. SIT in the MICE Industry

As previously discussed, SIT focuses on “the group in the individual” []. According to Tajfel and Turner, people classify others as belonging to different social groups and assess these scopes []. Membership is defined by social identity as well as the value given to them. Previous literature in SIT has generally focused on building on the harmonious identity or impact of identity within the internal perspective of companies, such as organizational productivity [], performance [] and motivation []. How then does SIT influence the MICE industry?

Despite the nature of the industry, which emphasizes the importance of the interaction between individuals and groups, limited studies have invested in learning about the impact of SIT on the MICE industry. For example, there have been studies on the influence of the identity, in which people easily identify the in-group and out-group, such as the tattoo industry [], fan conventions [] or within convention workers []. The results showed that congruence of identity between individual and group identities influences the behavior of consumers (attending tattoo events or fan events) and satisfaction of organization members. Furthermore, Ryu and Lee [] found that when convention visitors have a high self-congruence with an event, they show higher satisfaction with the event than visitors with low self-congruence with the event. Despite the high relevance and importance of SIT in the MICE industry, only a few studies have been conducted. Before further investigation, it is necessary to learn more about the characteristics and economic impact of the MICE industry.

Previous literature on MICE has shown that the MICE helps to increase economic benefits to the destination and the local community and also brings about a positive image of the destination []. The principle logic for this assertion is that the building of a convention center will attract more visitors, good hotels will make them stay longer, and other activities such as restaurants, shopping centers, and theatres will create good memories of their business trip []. This, on the other hand, means that the MICE industry cannot solely stand alone. Even though it has firmly built an internal social identity, the MICE industry needs high levels of support from residents and local communities.

SIT assumes full “collective” behavior, such as a sense of solidarity within a group for the purpose of achieving positive self-esteem and self-development, and discrimination against external groups as part of the social identity process []. In the MICE industry, many stakeholders are involved. Not only CEOs, founders, landlords and employees of MICE venues but also residents or merchants near the venues should be connected as a social group, and their influence should be shown as a collaborative effort. With collaboration between stakeholders based on strong social identity, any MICE venues’ MICE event can be held successfully and continue to be held in a sustainable way. Individuals may be motivated to contribute to the collective effort because it is reasonable to do so in a rational way because they can fulfil their moral obligations, or express and identify their valuable identity [].

How then can the MICE industry build social identity with communities consisting of different stakeholders who are pursuing different goals? This study employs the idea of brand building from the marketing literature. In fact, the logic of SIT is consistent with the mechanism of brand identity in that they consider possession of extended self, and are concerned with the relationship between individuals and either society or companies []. Kapferer suggested that the brand is the image of a product and should act as “a long lasting and stable reference” []. For the success of brand building, it is important to deliver integrated communication and consistent messages to customers []. In other words, brand identity should be set up in a long-term way, with a consistent concept, so that intergroup members can feel similarity, superiority and self-esteem.

As the theory of social identity suggests, social group members expect to express their desired identity through the brand community and get confirmation from others [], or they pursue interaction with brands or form a relationship with them []. Therefore, the goal of this study is to investigate how brand, personal and community identities have emerged, and these are described and redefined in the interaction between brands and individual stakeholders in the MICE environment.

Brand identity especially is built on a thorough understanding of customers, competitors and the business environment. Strong MICE brands have a high brand power to gain customer loyalty, high pricing potential and support for new product and service launches. How then can a MICE venue build a brand identity that can be shared with local stakeholders?

As discussed, it is important to share the common understanding of the core value in building on SIT. If all the members in the MICE industry share common core values, the intergroup members would pursue the attainment of common goals, and the feeling of superiority will increase self-esteem, which will result in building a sustainable MICE environment.

As a way of developing SIT (brand identities of MICE venues), we take a two-perspective approach, considering the exposure of venue names and holding of consistent events. In general, meaningful names bring favorable evaluations in building brand identity compared to non-meaningful brand names []. A meaningful product name mainly represents the important features or main characteristics of the product. The congruent image between a meaningful product name and important product attributes make consumers have a favorable perception of the product [,]. Kohli et al. repeatedly exposed meaningful and non-meaningful brand names and compared the evaluation of the products []. Through the whole experimental process, they found that a meaningful name was always favorably evaluated by the consumers. The study also suggested that meaningful brand names influenced quality evaluations and other overall attributes of the products.

Similarly, in building the brand identity of a MICE venue, it is important to deliver core value through a meaningful name, in a repeated manner. A product has certain important attributes, and the meaningful name should deliver an image congruent with these features. It is, however, difficult to deliver the main attribute or categories through the MICE venue itself, but it is possible by holding events with similar characteristics.

In the present study, residents and stakeholders near MICE venues were usually heterogeneous (i.e., different businesses with different management philosophies). In order to ensure that these diverse members have a common identity, it is important to educate the members with clear goals based on a congruent image of the venue, by setting a meaningful venue name and holding similar types of events. It is hypothesised that a meaningful name, with repeated exposure to its characteristics, provides all members with a clear guideline and congruent image of the MICE venue. When the identity of each MICE venue and individual is firmly established, it naturally connects to social identity and likely influences positive evaluation of the MICE venue.

The main objects in this study with regard to brand identity are that when a specific MICE brand name is determined, it naturally connects to the brand identity and helps MICE stakeholders to act positively and has loyalty, which is measured by the willingness to participate (WTP). Thus, the specific hypotheses we consider are as follows:

Hypotheses 1 (H1).

A context-oriented venue name positively influences WTP.

Hypotheses 1a.

When people face a context-oriented MICE brand name, they are more likely to participate in the MICE event compared to a general MICE brand name.

Hypotheses 1b.

When people continuously face similar types of events, they are more likely to participate in the MICE event compared to the inconsistently held events.

Hypotheses 1c.

As people are exposed to a meaningful MICE brand name and event, they are more likely to participate in the event.

Hypotheses 2 (H2).

Similar characteristics of events positively influence brand identity.

Hypotheses 2a.

When people face a context-oriented MICE brand name, they are more likely to identify with the brand compared to a general MICE brand name.

Hypotheses 2b.

When people continuously face similar type of events, they are more likely to identify with the MICE events compared to the inconsistently held events.

Hypotheses 2c.

As people are exposed to a meaningful MICE brand name and event, they are more likely to identify with the brand.

Hypotheses 3 (H3).

Increased identification mediates the effect of the MICE venue name on WTP.

3. Method

In order to investigate the way to build a sustainable MICE environment, this research employs the concept of SIT and conducts two experiments that investigate the effect of social identity on residents’ willingness to participate. In these experiments, we use venue names, as well as routines of exposure (consistent events vs. random events), and investigate whether the name and exposure influence the building of brand identity and increases the willingness to participate in the events.

Specifically, the purpose of study 1 was to understand the relationship between the MICE industry and social identity. The study used a between-subject experimental design to investigate the overall group effects of venue names and routines of exposure on social identity and the willingness to participate of residents. Based on the findings of study 1, we conducted study 2 to replicate the findings and increase the reliability. Compared to study 1, the second experiment employed a repeated within-subject design. Through the process of selecting preferred schedules depending on different venue names, the study strengthened the reliability of the findings of study 1.

We find that the brand name and exposure influence both social identity and willingness to participate. Taken together, these studies illustrate the mediating effect of social identity on willingness to participate. The following section discusses the conducted experiments to investigate the effect of identity building on sustainable MICE environments, as well as our findings.

4. Study 1

In order to test the proposed hypotheses, we recruited respondents from an online Korean panel. This study employed two types of venue names (context-oriented vs. not context-oriented) and two types of events (consistent vs. inconsistent) between-subject design. Respondents (female = 34%, median age 49.33, SD = 0.475) who agreed to participate in the experiment were randomly assigned to one of four different groups (see Table 1). The questionnaire consisted of two sections: (1) demographic questions and (2) new convention center scenarios. At the beginning of the experiment, all participants were asked to answer basic demographic questions and questions related to their experiences of events operated by convention centers. Respondents who were assigned to the “not context-oriented” venue name group were presented with a newspaper article about a new convention center named “Seoul Big Sight”, while participants assigned to the context-oriented venue name group were presented in the article with a context-specific name—“Korea Art Complex”. The news contained general information about the new convention center such as the location, size of the center, and date it was built. The only difference was the name of the convention center. After participants had read the article, we asked general attitude questions about the name of the convention center as well as whether they were residents in the area or owned a business near the center.

Table 1.

Demographic factors.

On the following page, we manipulated the consistency of the events. All participants found an annual schedule for the convention center. Participants assigned to the consistent event group were presented with a list of events with similar themes, while participants assigned to the inconsistent events group were presented with randomly themed events. After they had looked at the list of the events, participants were asked to answer questions about their opinions of the events, their willingness to participate in the events, and answered social identity questions, and debriefed.

Results

The Effect of a Context-Oriented Brand Name and Type of Event on Willingness to Participate (WTP)

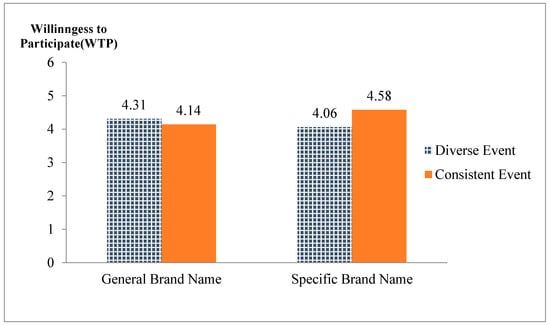

In order to investigate the effect of a MICE venue’s name and the characteristics of a MICE event on WTP, a two (MICE venue name) by two (type of event) between-subject ANOVA was conducted. Past experience of events was included as a covariate to control for the experiences. The measures of residents’ WTP were analyzed as the dependent variables. The results demonstrated insignificant main effects of the venue’s brand name (F(1, 202) = 0.483, n.s.), as well as the consistency of the type of MICE events (F(1, 202) = 0.634, n.s.). The two-way interaction effect between the MICE venue’s brand name and the consistency of the type of MICE events on WTP, however, was significant (F(1, 202) = 4.203, p < 0.05) (see Figure 1). The results indicated that the type of the MICE venue name (not context-oriented name vs. context-oriented name) and the type of events (consistent type of events vs. inconsistent type of events) did not individually affect WTP. However, the two-way interaction demonstrated the importance of venue name and consistent event type. As we expected, as the brand name became more context-oriented, and as the venue held more similar types of events, residents became more likely to participate in the events.

Figure 1.

The effect of brand name and event type on willingness to participate (WTP).

The Effect of Context-Oriented Brand Names and Type of Events on Identity

The results of our previous analysis suggested that there was no main effect of venue name and types of events on participants’ WTP; however, the significant effect of the two-way interaction suggested that when both the MICE brand name and event were considered, it influenced the residents’ WTP. Our next logical question was to understand the underlying mechanism of the interaction effect of venue name and event type on WTP. As a possible influencer, this study hypothesized that identity would mediate the effect of brand name and type of event exposure on peoples’ WTP. To investigate the effect of identity, this study approached the investigation from two perspectives: (1) understanding whether the venue name and type of event also influence the building of identity and (2) understanding whether identity was associated with participants’ WTP.

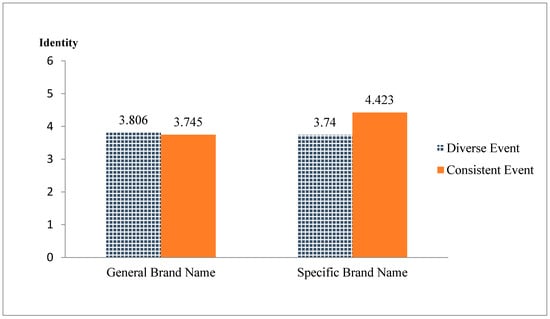

To examine the effect of a MICE venue’s type of name and the characteristics of the MICE event consistency in building the identity of the MICE venue, this study executed its analysis based on a two (MICE brand name) by two (MICE event) between-subjects ANOVA on identity. There were marginally significant main effects for the type of MICE venue’s name (F(1, 202) = 2.961, p < 0.1) and event consistency (F(1, 202) = 3.060, p < 0.1) in building identity. The two-way interaction between the type of MICE venue name and event consistency on identity was significant (F(1, 207) = 4.379, p < 0.05) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of brand name and event on identity.

The marginally significant main effect and interaction effect of brand name and type of event on identity supported H2, H2a, H2b, and H2c. The results showed that a specified brand name and exposure to the type of event positively influenced the building of a common identity among participants. In order to investigate the effect of identity on WTP, this research conducted a mediation test. As the results of the ANOVA suggested, the interaction between the brand name and the type of event significantly influenced participants’ WTP. In order to understand the underlying mechanism of the interaction effect on WTP, this research employed identity as a possible factor mediating the relationship.

To test the mediation effect, a bootstrapping method (Heys model 4; 5000 iterations) was used []. The results showed that the mediation through identity was positive and significant (β = 0.438, 95% CI = 0.165 to 0.731); however, the direct effect was not significant (β = −0.008, 95% CI = −0.3280 to 0.3117), which indicates that there was indirect-only mediation [] (see Table 2). The results suggested that a commonly shared identity was easily formed when the venue name was specific, and the shared identity mediated residents to participate in the event.

Table 2.

Indirect analysis: mediation test for Meetings, Incentives, Conventions and Exhibitions/Events (MICE) name and event on WTP.

5. Study 2

In study 1, the research suggests that context-oriented venue names, consistent types of events and identity play an important role in understanding the residents’ willingness to participate in the event. We, however, noticed some power issues, which could be due to the relatively small number of participants as well as the fact that only one type of venue name was considered in study 1. In order to strengthen the reliability and validity of this research, study 2 was conducted.

5.1. Method

In order to test the proposed hypotheses and replicate the findings in study 1, a 2-venue-name (context-oriented vs. not context-oriented) × 2-schedule (consistent events vs. random events) mixed-factorial design was employed. Venue name was a between-subject factor, while schedule was a within-subject factor. In order to strengthen the generalization of the findings, study 2 was conducted amongst U.S. residents. A total of 300 respondents were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk (male: 61%; average age: 44.5; college graduates: 76.6%). As the subjects agreed to participate in the experiment, they were randomly assigned into two different conditions: either context-oriented venue name or not context-oriented venue name conditions. In this experiment, they were informed that this research was about understanding people’s attitude towards small business. After they answered demographic and small business-related questions, they were informed that a new convention center would open in 2021 and the coordination with the convention center would be important because the participants were willing to open local restaurants in that area. As they clicked the next page button, they would find the information of the venue name and two different types of prospective event schedules, one schedule consisted of similar type of events and the other schedule consisted of random events. They were asked to choose which schedule would benefit their business the most. If the participants were assigned into context-oriented conditions, they were given the context-oriented venue names (World Art Complex, Sands Business Meeting Center and Global Design Exposition Center). On the other hand, if participants were assigned into non-context-oriented conditions, they were given general names of venue names (World Complex, Sands Meeting Center, and Global Exposition Center) and were asked to choose preferred event schedules for their business. For example, the context-oriented group had the venue name “World Art Complex” and two schedule options: one was an art-related schedule, but the other option was a random-events schedule. The not context-oriented group found the venue name “World Complex”, and two same schedule options as the context-oriented group. Continually, all participants would find two more different venue names either context or not context-oriented conditions and were asked to choose either similar type of event or non-similar type of event schedules for their businesses. After they were asked social identity questions, they were debriefed.

5.2. Results

5.2.1. Choice of Schedule

Of 300 responses, 10 were not included in the analysis because they were unfinished responses. As discussed, in order to replicate the findings and generalize the results in study 1, study 2 was designed. In study 1, group comparison was used to understand participants’ WTP under the fictional convention center scenarios. Measuring attitudes towards fictional convention centers with a Likert scale, however, is bound to have limitations when it comes to participants’ involvement and judgment. To compensate for these limitations, study 2 was employed to choose preferred schedule choices according to the MICE venue name. In addition, the pattern of selection was also measured through three different repetitive choices. In order to investigate repeated choices between the context-oriented and not context-oriented group, this research analyzed the collected data using Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) methodology with a logit link function to accommodate the binary nature of dependent variables (0 for consistent event schedule, 1 for inconsistent event schedule with venue names). This study used GEE for two reasons: to understand the pattern of repeated choices between context and not context-oriented venue name groups and to calculate the predicted value of schedule choices for further mediation analysis. As study 1 suggested and our hypothesis, the estimated regression coefficients show a significant difference in the choice patterns between context-oriented group and not context-oriented group (context-oriented group: 0.58 vs. not context-oriented group: 0.50; Wald χ2(1, n = 870) = 5.88, p < 0.05). There was no significant interaction effect between context type and repeated questions (Wald χ2(2, n = 870) = 2.131, p = ns). We also used linear link function to estimate the effects on social identity. Consistent with the findings in study 1, there was a significant main effect of venue name on identity (context-oriented name group: 3.79 vs. not context-oriented name group: 3.58; Wald χ2(1, n = 870) = 18.161, p < 0.01); however, no interaction effect between venue name and questions was found (Wald χ2(2, n = 870) = 0.001, p = ns). Thus, the results indicated that the context-oriented venue name group and not context-oriented venue name group clearly indicated different patterns of schedule choices and building of social identity. The context-oriented venue name group was willing to choose the option that consisted of similar events that related to the characteristics of the context-oriented venue name, and they acutely felt the importance of social identity. Additionally, the results of the insignificant interaction effect indicated that no particular venue name caused the main effect of the venue name in the analysis.

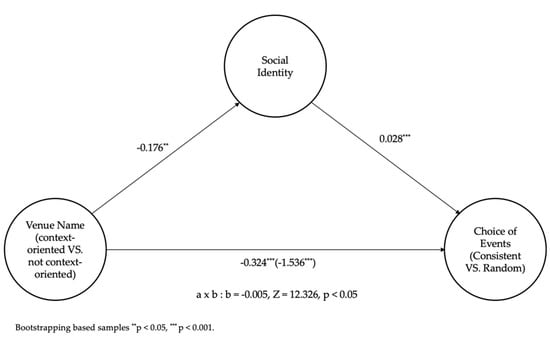

5.2.2. Mediation Test

In order to investigate whether social identity mediated the effect of venue name on schedule choices, we used predicted values of schedule choices as dependent variables which were calculated through GEE. We used a bootstrapping method (Hayes model 4; 5000 iterations) []. As hypothesized, the social identity mediates the effect of venue name on the predicted value of schedule choices (β = −0.005, 95% CI = −0.0088 to −0.0018). The significant but negative indirect effect with 95% confidence interval suggested that as the venue names become general, the social identity decreases (a = −0.176, t = −3.696, p < 0.01), which would positively influence choosing the option consisting of context-oriented event schedules (b = 0.028 t = 4.51, p < 0.01). The direct effect was also significant (β = −314, 95% CI = −0.3313 to −0.2973) (see Figure 3). Similar to the findings of study 1, the results showed that as the MICE venue name was context-oriented, shared social identity was easily shaped, which mediates participants to choose context-based event schedules for their business.

Figure 3.

The mediation analysis.

6. Discussion

In recent years, the MICE industry has seen an upsurge in interest surrounding sustainable development. A significant proportion of the previous literature on sustainability caused an interest in investigating the economic benefits for the industry, rather than to simply understand the fundamental underlying mechanisms of sustainability in the MICE industry. The MICE industry is expected to gradually grow in the future, and the growth could continue to get stronger based on the physical, social and natural environment of its destination. However, previous research on the sustainability-based perspectives of participants has been limited.

This research focused on identifying essential factors that could be practically helpful for individuals when sustainably designing a MICE event, to connect to stakeholders near the MICE venue. Study 1 and study 2 suggested that residents’ WTP increased when a MICE venue name became more context-specific and as MICE events held shared similar characteristics. For instance, the results in study 1 for MICE events with consistent characteristics, such as “Seoul Design Week”, “Seoul Fashion Week”, “Fashion Culture Festival for Citizens”, “Design Protection Forum”, and “Exhibition for Illustration”, all held at the “Korea Art Complex” (a specific MICE venue name), positively affected the WTP of residents and merchants near this venue. The essence of this result is that a specific MICE venue name and consistent MICE events should be considered together to increase stakeholders’ WTP. Secondly, the result proves that when the MICE venue name is a context-oriented specific name and the MICE events have consistency, it is meaningful to social identity. As the conducted studies suggest, the MICE brand name and event should both be considered to build a strong identity. For instance, inconsistent MICE events in study 1, such as “Travel Fair”, “VR Summit”, “Asia Pacific Cancer Conference”, and “Construction and Interior Fair”, organized at “Seoul Big Sight” (a general MICE venue name) would be difficult to showcase a meaningful effect on social identity. The findings of this study also provide implications for specific MICE members.

Firstly, this study suggests that appropriate actions should be taken when planning to build a MICE venue in a certain area. It is already well-proven that the MICE industry should consider the information available regarding the dimensions of the two bottom lines in setting up a sustainable MICE environment. The first concerns the MICE brand name and event, and the other concerns the social identity. In the early meetings on the establishment of the MICE venue, as many stakeholders as possible, including nearby shopping malls and residents, participated as members. Therefore, social identity can be reflected in the venue name and event from the beginning. Secondly, the study’s results suggest the importance of SIT education. To create a sustainable environment, participation of various stakeholders is essential. However, among workers in the MICE industry, a clear understanding of the meaning of SIT and the intention to revitalize it should be prioritized. To achieve these goals, training the MICE industry workers is necessary. An effective SIT education program will help build a sustainable market environment by building a strong identity within the industry and local community. Lastly, this study proposes to improve the existing MICE business system. In the event selection process of the MICE industry, profitability is prioritized over consideration of event characteristics, and various events are held in the form of rentals. This study, however, suggests that the venue manager and event organizers meet before final confirmation so that the association between the venue brand image and the event characteristics can be matched, rather than the conventional random event method.

These three points improve the identity created by the collaborative work between residents and merchants (referred to as stakeholders) near the MICE venue. The results of this study might stimulate greater interest in sustainability issues among individuals working in the MICE industry.

This paper presents an argument to include sustainability in social identity theory. This is only the first step in developing sustainable practices in the MICE industry. Much research is needed to develop this field. The proposed focus for further study is to assess how effectively the MICE organizers adopt sustainability, identify the current technology of the individuals working in the MICE industry and how they can continue to manage and identify innovative industry data practices. Academia can also look to integrate sustainability management across all aspects of the MICE industry.

Academically, this research also contributes to the literature on sustainability and MICE. Previous studies have been conducted to figure out effective ways to construct a sustainable MICE environment. However, the main principles of these studies tended to focus on MICE destination competitiveness compared to other MICE regions, price structure or service quality, such as restaurants, shopping areas, accommodation, and transport near the MICE venue. These studies were related to MICE tourism and stakeholders’ loyalty, or attractiveness towards the MICE venue’s brand identity or personality, which could usually be explained by customer relationship management (CRM) from marketing theory or supply chain management (SCM) theory. In other words, these studies suggested some theoretical methods but did not show detailed examples to those working in the MICE industry. Specifically, venue name and event consistency should be considered at the same time, and during this consideration by those in charge, identity plays a critical role as a mediator between the above factors on WTP, which could be established with positive collaborative work between stakeholders. In other words, this study provided a step-by-step guideline to building a sustainable MICE environment in both a theoretical and practical way.

The proposed model seeks to expand on existing knowledge by developing the theoretical direction to understand and predict the behavior of residents and traders, in accordance with MICE location name ambiguity and MICE event consistency, and provides a basis for identity involved in measuring residents’ perceptions of the MICE brand name and events. In addition, this paper indicates applications for social identity theory to be used in the MICE industry setting.

The development and proposal of the theoretical direction of MICE’s establishment of sustainable environments are expected to give positive stimulus for future research and development from the actions of residents and merchants’ based on collaborative work for identity, consistent identity for a MICE venue area being built as well as the brand image as a MICE venue, and it provides the opportunity to increase residents and merchants’ satisfaction and income. This situation creates an actual sustainable MICE environment. According to Ap [], residents’ attitudes towards certain MICE events played a significant role in developing current and future events, and to organize and open a successful and sustainable MICE event, residents’ active support and positive collaborative work were essential. After all, the development of the region and the development of the convention center are not separate, and it is important to create a sustainable environment through the establishment of cooperative relationships with each other. Therefore, this study contributes to filling the gap between residents and stakeholders, and provides an actual way that can connect the development of a sustainable MICE environment by figuring out the concept of “social identity”.

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There were limited main effects in both WTP and identity analyses in study 1; no main effect of venue name and type of events on WTP as well as marginally significant main effects of venue name and type of event on identity. Thus, study 1 failed to support H1a and H1b. Regarding the limited main effect, we suspect that weak manipulation and a relatively small sample size caused the problem. Influencing people’s behavior and forming an identity usually takes a lot of time and effort. The limited experimental time with fictional venue names and events may not provide strong enough manipulation. The direction of the consumer tendency, however, showed the same pattern as that which this study hypothesized. In particular, the purpose of this study was to understand the simultaneous effects of venue name and type of events on the residents’ attitude changes and forming identity, rather than their independent effects. On the contrary, the significant two-way interaction effect on WTP and identity under relatively weak manipulation indicated the importance of the effect. Additionally, in order to complement the limitations in study 1, study 2 was designed. First, the study aimed to strengthen reliability and validation by recruiting more samples from the U.S. online panel. Second, mainly one-factor design was employed to increase the involvement in this study. Participants were guided into one of the context-oriented or not context-oriented MICE venue name conditions, and continually asked to choose preferred event schedules for the assigned venue name conditions. Even though study 2 also employed fictional venue names and events, the repetition of similar questions would increase involvement in the study. Moreover, the study was designed to reduce the gaps between the lab and the real world. Empirically, the MICE venue name is decided at the beginning and goes through the process of creating a brand by holding diverse events. Study 2, thus, focused on supporting the findings in study 1 rather than in testing new hypotheses.

Despite the important contribution of this research, there are some limitations. First, to find out residents’ or merchants’ perceptions of MICE venues, an imaginary situation was created that did not use real field data. No actual transactions were employed in this study. In particular, as this research investigated people’s perception caused by assumed situations of the MICE venue construction, there will be a gap between imaginary situations and the real life of residents or merchants. In addition, only the MICE brand name and event have been handled to determine factors that can increase WTP and identity amongst many other elements, for example, the period of MICE events, the infrastructure of MICE venues and geographical location of MICE venues. Real field data from residents and merchant’s perceptions of real MICE venues should be investigated, along with various factors that could moderate or challenge the effects of increasing the WTP towards the MICE venue, increasing identity and finally building a sustainable MICE environment.

Second, this research was conducted with a small sample size to reflect accurate industry trends and consumer opinions. However, various efforts were made to compensate for the limited sample size. First, consistent results were derived through two different study designs: survey and experiment. Despite the different methodological approaches and small number of samples, consistently significant results were obtained. Second, Study 2 was designed to reduce external validity through experimental design. Particularly, by carrying out repeated designs for 300 samples for a one-factor design and by analyzing through the bootstrapping method, this study tried to increase the reliability of the results.

Third, for sincere consideration of building a sustainable MICE environment, an overly specific MICE brand name can be a challenge for a MICE venue’s business management. Some MICE venue owners or CEOs can be concerned with creating profits with an overly specific MICE brand venue name, such as “Korea Art Center” or “Seoul Design Complex” because these kinds of names can create a stereotype for organizers or investors that suggests that only MICE events with specific characteristics are able to be organized at the venue, which means the ability to generate more profit from various kinds of events can be limited. On the other hand, if the target of development is not limited to the convention center and the focus is on the development of the whole community, it will be possible to build a system that allows the center and the community to grow mutually in the long term. Therefore, for the sustainable development of the MICE industry, cooperation with the local community would be a crucial factor that will bring sustainable success for the MICE industry and the local community.

Last, this study focused on limited dimensions of sustainability rather than to investigate all dimensions such as economic, environmental, social, ethical, and technological dimensions [,]. Research on MICE and sustainability, unfortunately, has been scarce, and this research concentrated on understanding the underlying mechanisms of sustainable environment in MICE industry. In particular, this research proposed the sustainable business model based on economics and the social dimensions of sustainability that is the most fundamental element in a business environment. Despite the weaknesses of this study, we believe that this research contributes to the MICE industry by showing the way to build a sustainable business model for both community and the industry and by suggesting a future direction. It will be crucial to investigate ways to build a sustainable environment considering all dimensions of sustainability in further studies.

Author Contributions

K.K. and D.K. conducted literature review, conceptualized the study and contributed to writing of all sections. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Hankuk University of Foreign Studies South Korea Research Fund & This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2019S1A5A2A03036591)

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Dwyer, L.; Mistilis, N.; Forsyth, P.; Rao, P. International price competitiveness of Australia’s MICE industry. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, J. The role of events in the promotion of cities. In Proceedings of the International Conference-Events and Place Making, Sydney, Australia, 15–16 July 2002. [Google Scholar]

- KTO, Korea National Tourism Organization. The Economic Impact of Korea MICE Industry Report; Korea Mice Industry Outlook 2019 and Beyond; KTO: Seoul, Korea, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Presbury, R.; Edwards, D. Incorporating sustainability in meetings and event management education. Int. J. Event Manag. Res. 2005, 1, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Buathong, K.; Lai, P.-C. Perceived Attributes of Event Sustainability in the MICE Industry in Thailand: A Viewpoint from Governmental, Academic, Venue and Practitioner. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, H.T. Convention Myths and Markets: A Critical Review of Convention Center Feasibility Studies. Econ. Dev. Q. 2002, 16, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, J.M. Identity based views of the corporation: Insights from corporate identity, organisational identity, social identity, visual identity, corporate brand identity and corporate image. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 879–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. A blueprint for sustainability marketing: Defining its conceptual boundaries for progress. Mark. Theory 2016, 16, 232–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, W.M. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 78, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commonwealth Department of Tourism. National Strategy on the Meetings Incentives Conventions and Exhibitions Industry; Australian Government Printing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Muqbal, I. Market Segments The Asian Conference, Meetings and Incentives Market Travel and Tourism Intelligence. Travel Tour. Anal. 1997, 2, 38–56. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. Determinants of Residents’ Participation Behavior for the Success of Mega-Event—The Case of IAAF World Championships Daegu 2011, 2010. J. Tour. Manag. Res. 2014, 1, 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-W.; Kim, B.-S.; Lee, S.-Y. The Impact of brand awareness and image of an exhibition and convention center on brand equity of the venue—Focused on KINTEX employees and experienced users. Korea Trade Exhib. Rev. 2014, 9, 61–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C.; Oakes, P.J. The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 25, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social Identity Theory and the Organization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.-W. Promoting Consumer Engagement in Online Communities through Virtual Experience and Social Identity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An Integrative Theory of Inter-Group Conflict. In The Social Psychology of Inter-Group Relations; Williams, J.A., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole Pub. Co: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ellemers, N.; Kortekaas, P.; Ouwerkerk, J.W. Self-categorization, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 23, 371–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A.; Abrams, D. Comments on the motivational status of self-esteem in social identity and intergroup discrimination. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 18, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Cognitive Aspects of Prejudice. J. Soc. Issues 1969, 25, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H. Social Categorization (English Translation of “La Cat6gorisation Sociale”). In Introduction a La Psychologie Sociale; Moscovici, S., Ed.; Larousse: Paris, France, 1972; Volume 1, pp. 272–302. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J.C. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Worchel, S., Austin, W.G., Eds.; Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 2004; pp. 276–293. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel. H. Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes, P.J.; Turner, J.C. Social categorization and intergroup behavior: Does minimal intergroup discrimination make social identity more positive? Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 10, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, U.; Lampen, L.; Syllwasschy, J. In-group inferiority, social identity and out-group devaluation in a modified minimal group study. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 25, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamir, B. Calculations, Values, and Identities: The Sources of Collectivistic Work Motivation. Hum. Relat. 1990, 43, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajfel, H.; Turner, J. An integrative Theory of Social Contact. In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Austin, W., Worchel, S., Eds.; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.J. The effects of intergroup similarity and cooperative vs. competitive orientation on intergroup discrimination. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 23, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social Comparison, Similarity and Ingroup Favoritism. In Differentiation between Social Groups: Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations; Tajfel, H., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 235–250. [Google Scholar]

- Albert, S.; Whetten, D.A. Organizational Identity. In Research in Organizational Behavior; Cummings, L.L., Staw, B.M., Eds.; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1985; Volume 7, pp. 263–295. [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth, B.E. Climate formation: Issues and extensions. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 837–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovsky, B.; Hogg, M.A.; Abrams, D. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes. Contemp. Sociol. A J. Rev. 1990, 19, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worchel, S.; Rothgerber, H.; Day, E.A.; Hart, D.; Butemeyer, J. Social identity and individual productivity within groups. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 37, 389–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.E.; Aicher, T. Follow the Leader: A Relational Demography, Similarity Attraction, and Social Identity Theory of Leadership Approach of a Team’s Performance. Fem. Issues 2013, 30, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.J.; McQuitty, S. Attitudes and Emotions as Determinants of Nostalgia Purchases: An Application of Social Identity Theory. J. Mark. Theory Pr. 2007, 15, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, S.; Childs, M.L.; Kim, Y.-K. Attending a tattoo convention: To seek or escape? J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 36, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reysen, S.; Chadborn, D.; Plante, C.N. Theory of planned behavior and intention to attend a fan convention. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2018, 19, 204–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Ladkin, A. Career Identity and its Relation to Career Anchors and Career Satisfaction: The Case of Convention and Exhibition Industry Professionals in Asia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, 16, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Lee, J.-S. Understanding convention attendee behavior from the perspective of self-congruity: The case of academic association convention. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 33, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Convention destination images: Analysis of association meeting planners’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D.A. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for OCD; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, S.K.; Ahearne, M.; Hu, Y.; Schillewaert, N. Resistance to Brand Switching when a Radically New Brand is Introduced: A Social Identity Theory Perspective. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapferer, J.N. The New Strategic Brand Management: Creating and Sustaining Brand Equity Long Term; Kogan Page: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ghodeswar, B.M. Building brand identity in competitive markets: A conceptual model. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2008, 17, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algesheimer, R.; Dholakia, U.M.; Herrmann, A. The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European Car Clubs. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloutsou, C. Brands as relationship facilitators in consumer markets. Mark. Theory 2009, 9, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, C.S.; Harich, K.R.; Leuthesser, L. Creating brand identity: A study of evaluation of new brand names. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1506–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, R.A.; Ross, I. How to Name New Brands. J. Advert. Res. 1972, 12, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).