Abstract

This study is the first to perform a focalized analysis on city development, sustainable urban planning, and the negative impact of slum area disamenity on property valuation in suburban and posh areas of the Islamabad region, Pakistan. Slums exist in almost every country in the world. However, in the process of urbanization and city development, researchers have focused merely on the crumbled infrastructure, crimes, and other social problems associated with slums. Studies have covered the adverse effects of these factors on property value, although this unmatched study is the first to examine the negative impact of slum proximity on the valuation of properties in the surrounding areas and on the rental value of houses located in Islamabad. The survey method is applied to obtain feedback from inhabitants, and the study incorporated the hedonic price model to assess rental values within a range of one kilometer from selected slum areas. The findings revealed that slum neighborhoods negatively impact sustainable house rental values, as compared with the rental values of houses located far away. Rents became higher as the distance from the slums increased. The results showed that having slums in the vicinity caused a decline of almost 10% in rent. However, the rental value of a similar house unit, located 500 meters away, was found to be almost 10% higher. In the semi-log model, house rental values increased by approximately 12.40% at a distance of one kilometer from slums, and vice versa. This study will use residents’ feedback to help government officials and policymakers to resolve slum issues, which is essential for maintaining sustainable development and adequate city planning. This study sample’s findings are not generalizable to all slums, as the results are specific to this region.

1. Introduction

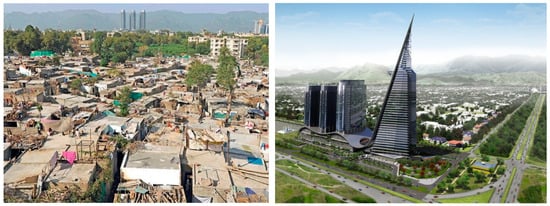

Slums exist in the neighborhood of posh areas and the exterior of big cities because the latter attract people for economic reasons. However, the increasing of slum areas is becoming a challenging issue for urban planning and policymakers around the world [1,2]. Precisely and concretely, around large cities, more opportunities exist. For instance, better localities, with socio-economic, cultural, and pleasant environmental experiences create employment and income, contribute towards local community amenity, and aid in the conservation of the local communities’ socio-cultural infrastructure [3,4]. Ideally, humans desire to settle in a better society, and they choose better living places with improved social services for creating a peaceful and smooth life. Thus, the modern world’s societal and environmental qualities are vital for people, as such factors unswervingly influence people’s day-to-day life [5,6]. Thus, residential areas and societies offering better environmental aspects have higher-quality mental health conditions and social well-being for people seeking such opportunities [7]. In an earlier study, Mahabir et al. (2016) claimed that almost one billion individuals are residing in slums or underdeveloped areas in the neighborhood of large cities around the globe [8]. Thus, it has become a global issue, as according to the findings of the UN-Habitant, (2010), the population of slums is likely to grow by up to three billion worldwide by 2050 [9]. This study is based on the Pakistani context and urbanization, and city planning has been an ignored area, as it has not been in the top priorities of the previous governments [10]. As a consequence, people with a lower income and of a lower labor class have suffered in facing the challenging environment of slums close to big cities in seeking job opportunities and other facilities [11,12]. Henceforth, tenements have increased in all major cities in Pakistan, such as Lahore, Karachi, Faisalabad, Multan, and the twin cities of Rawalpindi and Islamabad [13]. While world leaders and famous consultancy firms well-planned Islamabad before its construction, Doxiadis Associates was consulted in the 1960s, before executing the final master plan of Islamabad city [14]. At present, the capital city, Islamabad, offers state-of-the-art urbane real estate infrastructure, and the elite individuals across the country prefer to settle in this modern city, as they can enjoy current infrastructure, better security, surrounding natural sights, a better environment, and other additional facilities associated with a better quality of life [1,15,16] (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Slums/Katchi abadi’s settlements and city center in Islamabad. Note: Figure 1 displays slum areas and the location of the city center considered in this study (Source: Wikipedia).

There are some helter-skelter residential settlements in the neighborhood, including on the inside and the outskirts of the city, with infrastructure and bedraggled real estate conditions. Since the inception of this modern city, slum (Katchi abadis) infrastructure has been ignored and underdeveloped due to the unskilled labor class and the lower-class individuals residing in such areas who seek employment. During the last few decades, temporary squatter settlements were constructed close to various construction sites [17]. The Doxiadis firm prepared a social segregation plan of occasional follower colonies for workers and the labor class to settle their residential problems. During the development plan of Islamabad in the 1960s, however, the policy of temporary worker colonies failed to assess the real need of residence, public facilities, recreational activities, security staff, waste collectors, road sweepers, domestic service staff, drivers, launderers, and other unskilled workers [18]. Since that time, this gap of residential facilities for such people remained ignored, and these slums grew with time. These people occupied vacant lands owned by the government in areas external to the city and established slums, as it was convenient to reach workplaces and saved transportation costs [1,13]. Currently, two types of slums/Katchi abadis exist in the surrounding areas of Islamabad, such as government-authorized slums and illegal slums (squatter settlements). The government of Pakistan owns only the legal slums and allocates funds for infrastructure development, while unauthorized slums are unlawful and are not considered for development funds. In the current scenario, such types of slums exist in the surroundings of Islamabad city’s residential sectors, and people face a lack of necessities, deteriorated infrastructure, and poor living conditions. The other disamenity associated with slum proximity may include noise, crimes, drugs, prostitutes, air pollution, diseases, poor infrastructure, and gangs [19]. These slums have impacted significantly on rent valuation, as external amenity and disamenity are commonly discussed between the property dealers and house buyers during the property purchase process, which ultimately influences the residential property value [20]. Antisocial land utilization anticipated the numerous risks to the adjacent environment, and it is likely to negatively affect the valuation of surrounding real estate [21]. Previous studies evidenced that neighborhood disamenity, like high-voltage transmission sites [22], remediation sites [23], incineration sites [24], hazardous industrial sites [25], landfill sites [26] and nearby urban villages [27], has an adverse impact on property values. On the other hand, amenities, like parks [28,29,30], public green places [31], professional sports facilities [32] and transportation facilities [33], positively affect nearby property values (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Overview of Islamabad and slum (Katchi Abadi); Note: Figure 2 presents slums, elite areas, and the city center location under this study (Source: Wikipedia).

This study focuses explicitly on examining the externality effects of slum settlements on surrounding residential property values in Islamabad. Researchers fairly covered socio-economic issues in the previous reviews. However, they have not investigated the negative impact of the proximity of slums on the rent and sale values of nearby properties. This study attempts to fill the gap found in the previous literature by covering the impact of the externality of slums on surrounding property values. It is the first study that plans to understand the mechanism of price valuation and aims to identify the critical property determinants that could impact on property values in the neighborhood of slum areas in Pakistan.

The structure of this study is systematically comprised of steps, covering a survey of slums and surrounding residents, a literature review based on the hedonic price model, and a summary of the previous studies that cover the negative external impacts. The methodology section describes the study focus, data, variables selection, and the proposed models. This study has recorded the rent price of the ground-floor portion of houses located in slum areas, whether the residents were house renters, tenants, or the house owners. We executed the survey through self-reported rental values, as a proxy for estimating the hedonic property price function. In the next phase, the data analysis and study results are presented. The last section of this study draws the conclusion, makes recommendations, and indicates policy implications.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Hedonic Price Model

The two main approaches could assess environmental services and the monetary value of goods, such as the revealed preference and stated preferences [34,35]. These two approaches are employed to examine the economic value effects of external amenity and disamenity, for instance, the stated preference and revealed preference methods [36,37,38]. The preferable way to assess property valuation is the contingent valuation model, which is a nonmarket valuation method, as it is the direct method for the economic cost of goods and services [39]. The survey technique elicits people’s preferences, as well as value for the products and services. Typically, individuals are asked about their paying capacity for goods, amenity, and recreational activities [40]. This method is usually used to evaluate the effects of urban planning projects and environmental assets [41]. A revealed preference method is an indirect approach, which is widely used to examine the economic value of an environmental asset, and it relies on the actual preferences of individuals in transactions and accurately explores the market situation. The travel cost and hedonic price model are included in the revealed preference method [42]. The travel cost method is used to examine the value of the resource attraction of landscapes inside and far from the city, as well as the convenience of access to resources [43]. The hedonic price model is the revealed preference method, used widely to evaluate the value of those attributes of goods that are not openly traded in the market. The model has been generally applied for the evaluation and examination of the economic value of external amenity and disamenity, such as public parks, green belts, and landfills [44]. Rosen (1974) presented the theoretical contribution of the hedonic price theory and argued that a single good has various attributes, and each character has a value contributing to the price of the item in an equilibrium market [45,46].

The model was initially employed to evaluate the value of non-spatial composite goods, for instance, refrigerators, automobiles, personal computers, and tires [47,48]. Later, this model was extensively applied in determining house prices to assess the economic effects of environmental and locational externalities [49,50]. The hedonic price method suggests that residential houses are composed of a bundle of heterogeneous characteristics, and each attribute contributes to setting its selling or rent price [51,52]. Thus, the fundamental proposition of this model (HPM) is that residential properties are composite goods that are based on various landscapes, and each characteristic impacts on the sale price [53]. Some characteristics of the houses are physically recognized. However, the elements of the uncertain environment and other external landscapes that could affect the value of the home are essential [54]. Generally, people want to pay more for a home with an attractive design and are also willing to pay more for a beautiful view from the house, and the additional payment is estimated to be the value of the aesthetic service [37,52]. Several characteristics of the housing unit contributed to the sale price. However, a statistical model has been constructed to assess the value of each attribute. Therefore, the hedonic price model serves to determine the implicit cost of each characteristic considered in the function [55]. The HPM is a widely acceptable and reliable valuation approach because it is based on actual transaction data [56,57]. Ample studies on hedonic price studies have been conducted in different geographical locations around the world to evaluate the externality effect of the environmental amenity and disamenity on proximate property values, such as accessibility to public parks and green spaces [29,31], sports facilities [32,58], transportation facility [33], toxic waste sites [23], incineration plants [24], landfill sites [59], proximity to cell phone towers [60], and hydropower dam [61]. A study based on a meta-analysis was conducted by Simons and Saginor (2006), covering 75 research articles and case studies on the influence of various externalities on the adjacent property values by incorporating the hedonic price model [62].

2.2. Hedonic Studies on Externalities

The focus of this section is to review some studies relating to the effects of adverse externalities on proximate property values. The summary of some Hedonic price studies associated with the adverse impact of disamenity is covered in this work. The survey by [27] on the effects of urban villages on surrounding property values was conducted in Shenzhen, the highest per capita income city in China. They employed a hedonic price model to assess the impacts of urban villages on the sale price of a house on the open housing market [63]. They found lower housing prices for buildings closer by one meter to the nearest urban village; all other attributes remaining constant, this reduced the house sale price by approximately $23 for a typical condominium [64]. The hedonic study by [65] on the disamenity impact of open sewers on house rental values was conducted in Rawalpindi, Pakistan. He examined the effect of the public sewer system by investigating the properties of nearby open sewer areas as well as the properties of a closed sewer system, located near the city. The findings showed a negative impact of the open drainage system on surrounding property rental values in the study area. The results revealed that house rent prices decreased by approximately 10% when there was an open drainage line in the area. Furthermore, house rent prices increased as the distance from the housing unit to the main open drain (Nala lai) increased. A house located 400 meters away from the main open drainage line enjoys a 12% increase in the rental value, with other attributes remaining constant [66]. John McCord examined the “Peace walls” impact on house prices and valuation in the Belfast housing marketplace, Northern Ireland, as the “Peace walls” purpose was to provide security to religious communities [66,67].

The results of the hedonic regression analysis of 386 houses revealed that the house value decreased by 29.6% within a distance of 250 meters from the “Peace walls,” while Zabel and Guignet (2012) conducted a hedonic analysis to examine the impact of LUST (petroleum from leaking underground storage tanks) sites on house prices [66]. They used data of single-family home sales transactions from 1996 to 2007. The results revealed that publicized sites could decrease surrounding home values by more than 10%. Hite et al. (2001) investigated the effects of landfill sites on property values in Franklin County, Ohio and found an adverse impact of open landfills on their adjacent property values [59]. Another study explored the relationship between the proximity to a landfill and housing value in the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan, South Africa [68]. The findings showed an average of US$1.81 increase in the cost of properties located 100 meters away from the landfill. They found that wealthier individuals were willing to pay more to live far away from the landfill areas, as compared to the poor. Another study examined the effects of the four state-established landfills on residential property prices in Lagos State, Nigeria [69]. They distributed structured questionnaires among estate surveyors and residents within a 1.2 km radius from landfill sites. The linear hedonic regression results indicated that the property value increased by an average of 6% as the distance between landfill sites and residential house units increased, and they focused on the effects of unmanaged solid waste sites on real estate property rental values in the Surulere Local Government Area of Lagos State, Nigeria [46,53,70]. Administered structured questionnaires collected data among residents and property dealers. The results show that the rental value of properties around solid waste sites was low, as compared to similar properties located away from the waste sites.

Neelawala, Wilson, and Athukorala (2013) examined the effects of mining and smelting activities on nearby property values in Queensland, Australia [71]. The results revealed that properties located away from mining and smelting activities have a higher value, as compared to nearby properties. The study showed an additional AUD$13,947/kilometer, with a marginal willingness to pay to live father from the mining and smelting sites within the four-kilometer radius selected [35,67,72]. The review of the literature revealed that several hedonic price studies had been conducted to access the influence of different neighborhoods and environmental attributes on proximate property values. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to focalize an investigation on house rent values and the impact of slums on surrounding residential property values. Thus, the research contributes to scientific knowledge based on the hedonic price literature.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The Hedonic Method Model Development

The empirical model of the hedonic pricing method: Typically, studies based on empirical models apply the hedonic pricing approach, using different types of equations by combining all the characteristics of the house price that a specific buyer shows a willingness to pay [11,67,72]. Generally, different housing goods prices might be described by a hedonic price model that holds a combination of the housing characteristics. Thus, a housing unit is a bundle of heterogeneous attributes of goods and services. The hedonic price model is being used to determine how various dwelling attributes affect the house price. It determines consumers’ willingness to pay for different characteristics of houses [66,72,73].

where Rp represents the rent price of the house, and X1, X2, X3…., X are the structural, neighborhood and environmental characteristics of the housing unit, respectively. The partial derivative from the dependent variable rent with respect to essential variables gives the marginal willingness to pay for an additional unit from the attributes listed in the function, which results in an implicit measurable value of each characteristic [11,35,74]. The hedonic price model offers various functions for calculating property values, and researchers have the options of various functional forms to determine the suitable and appropriate function, according to the nature of their specific empirical model, for assessing property values. Thus, researchers applied different functional forms of the hedonic pricing technique, such as the linear functional form [69,75], log-linear functional form [76], and log-log functional form [77]. The selection of the functional form is a sensitive matter, because the economic theory does not clearly guide the selection of the best functional form. However, various studies investigated the advantages and limitations of each functional form [39]. Nonetheless, there is no concrete evidence that one functional form is better than the other forms [71]. Henceforth, some researchers believe that the method of Box-Cox transformation allows investigators to choose the proper function of the hedonic regression model based on the best fit for a particular data set [78,79,80]. Davidson and MacKinnon (1993) explained that the complicated transformation processes could generate more random errors [81]. The selection of the functional form could be best served by choosing according to the characteristics of the data received and the nature of the analysis required for the best representation of the results [74].

3.2. Selection of Variables

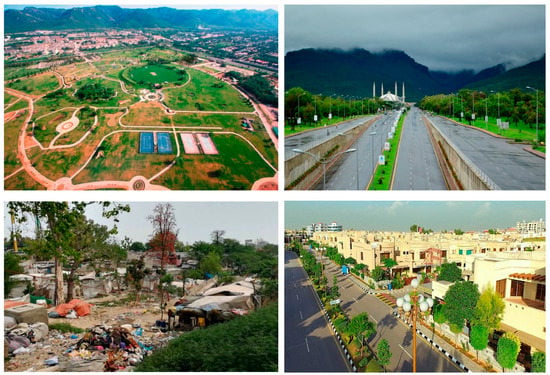

Based on the conceptual framework shown in Figure 3, the variables of model are considered. The house rent price (sustainable rent value) is considered as a dependent variable in this study. The sale price of the property is commonly used in hedonic regression studies, but the unavailability of enough property sale transaction data leads to the use of the rental value of houses, rather than the sale value [39,65]. The survey method based on the self-reported rental value method is used to measure the hedonic regression function [65]. The monthly rent of the ground floor of the house was taken as a rental value to assess whether the occupant was the owner or a tenant. The study determined the rental value of the homes occupied by tenants as well as by owners [82]. Later, it was rechecked and confirmed with property dealers and other tenants to confirm the validity of the recorded rental value of similar houses on the same street. Several previous studies covering the structural characteristics of the house, neighborhood accessibility and environmental variables in the hedonic price function had examined the rental value of homes [65].

Figure 3.

Conceptual Framework.

Table 1 below displays selected variables, with expected (+ or –) signs. The explanatory variable used as a structural characteristic, such as house age (House_age), house size (House_size), number of bedrooms (Bedrooms), and number of bathrooms (Bathrooms), is expected to influence the house rental value positively. The drawing room (Drawing) is a dummy variable that represents the existence of the special room for guests, and the TV lounge (TV_Lounge) is also a dummy variable, indicating the availability of the living room in the house. The Tenant_type is a dummy variable, showing the type of tenants in the house. In Islamabad, most of the housing units are duplexes, and each floor has been rented separately.

Table 1.

Description of study variables.

In an earlier study, Din, Hoesli, and Bender (2001) enlisted (Lawn) as one of the critical dummy variables that demonstrates the outdoor open space [83]. The servant quarter (Servant-QTR) is a separate accommodation unit inside the house for security personnel, such as drivers and servants. Generally, the houses of wealthy people have the facility of separate quarters for the servant staff. The distance to the nearest slum/Katchi abadi (Slums_dist) is the critical variable of interest in this study. It explains and estimates the effect of slum areas/Katchi abadis on the rental value of a nearby house. According to the hypothesis, it is expected that in the neighborhood of slums/Katchi abadis, the rental value of residential houses will be lower, as compared to the houses one kilometer or farther away from slums. There will be a positive correlation between the distance and residential house rent, for instance, and the rental value will increase with increasing distance from the slums and vice versa. Slums_vis show the visibility of slum settlements from the house. According to the proposed hypothesis, they are the residents suffering the most. The central business district (CBD_dist.) is also considered as an essential variable of location. It shows the accessibility of the city center from the housing unit. Generally, property prices decrease as the distance increases from the housing unit to the CBD [84]. In Islamabad, each residential sector has a central point for markets, called the Markaz (Markaz_dist) of shopping markets, and this distance from the house to the Markaz sector would influence the rent of houses in this study area. Since its inception, Islamabad is famous for green, scenic beauty and its greenbelts (Greenbelt), and these exist along the major roads and avenues across the city, which enhances the environmental standards of the area (For the statistical description of the model variables (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics of the model variables.

3.3. The Functional Form of the Model

This study incorporated two functional forms of the Hedonic price model to assess the relationship between the rental value and multiple characteristics of the house. The study examined both the linear functional form (Equation (2)) and Semi-log functional form (Equation (3)). The linear functional form shows constant partial effects, and it is shown below:

where Rp is the dependent variable (Rental value), b1 to b13 are the independent variables that display the buyer’s marginal willingness to pay for each dwelling attribute, and ‘ε’ demonstrates the error term. The possible non-linear effect is measured through the semi-log function, which possibly measures the non-linear impact of the house rent price. This functional form can be used to linearize the non-linear relationship and can also be quite helpful in the interpretation of the independent variable coefficients concerning their elasticity. The equation of the semi-log model is described in the equation below:

Rp = b0 + b1House_age + b2House_size + b3Bedroom + b4Bathroom + b5TV_Lounge + b6Drawing + b7Servant_Qtr + b8Garage + b9Lawn + b10Tenant_type + b11Street + b12Greenbelt + b13CBD_dist. + b14Park_dist. + b15Markaz_dist. + B16Slum_dist. + b17 slum_vis. + ε

LnRp = b0 + b1House_age + b2House_size + b3Bedroom + b4Bathroom + b5TV_Lounge + b6Drawing + b7Servant_Qtr + b8Garage + b9Lawn + b10Tenant_type + b11Street + b12Greenbelt + b13CBD_dist. + b14Park_dist. + b15Markaz_dist. + B16Slum_dist. + b17 slum_vis. + ε

4. The Procedure, Study Area, and Data Collection

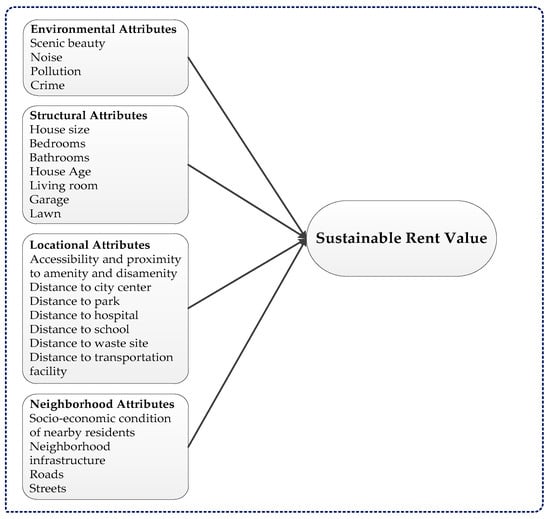

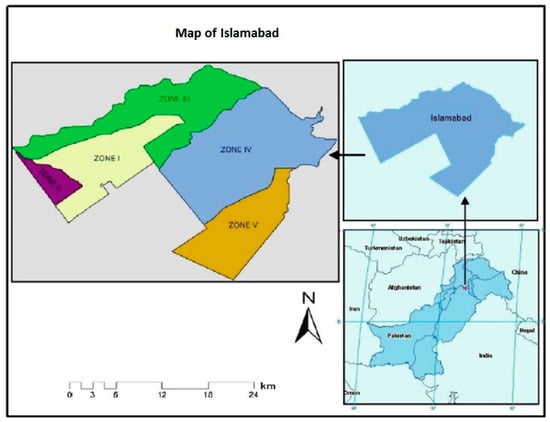

According to the recent census in 2017, the capital city of Pakistan has a population of more than one million, making it the tenth largest city in the country [85]. The city covered 906.50 square kilometers in area, consisting of both urban and rural areas. Urban areas comprise 220.15 km2, the rural area comprises 466.20, and 220.15 km2 of the area consists of parks [86]. The capital city is divided into five major zones, namely, Zone 1, Zone 2, Zone 3, Zone 4, and Zone 5 as shown in Figure 4. Zone 1 is designed for residential purposes, with nine sectors, starting from A, B, C, progressing all the way to ‘I,’ and each sector has a further four sub-sectors [87]. At present, 34 slums and Katch abadis exist in all the localities of Islamabad [86]. However, the Capital Development Authority (CDA) has recognized only 11 settlements/slums as legal residential areas [88]. The slum settlements exist in the residential zone one, which is the target population, and this study has selected six slum inhabitants through random sampling. This study offers a predefined impact of the locality through Google Maps, and it has sorted the selected slums into three ring-based distances. The first ring’s distance was 250 meters, the second ring was from 250 to 500 meters away, and the distance of the third ring ranged between 500 meters and one kilometer away from the selected slums.

Figure 4.

Map of Islamabad showing the study area. Note: Figure above is showing a zone-wise map of Islamabad [89].

We surveyed the targeted sample households during January–March 2018. The designed questionnaire had ten sections, gathering information on the socio-economic background of the household, characteristics of the house, neighborhood values, amenity, and disamenity, etc. We also measured the GPS coordinates of each house by using the Google Maps application, installed on our smartphones. The study did not use the rental value of the entire building. Instead, we used rental information on the ground floor of the house only to ensure the homogeneity, as it is the common practice of the people in Islamabad to sublet different floors to more than one tenant. Another significant reason for renting the ground-floor was based on the facility of a garage and lawn, as houses usually have these facilities on the ground floor only. Through random sampling, we selected 30 single family houses from each ring, and the total sample size was 540.

Further, the study chose single-family dwellings to ensure homogeneity. From the northwest of each slum, we started sampling by selecting the first and the second houses and dropping the next four consecutive houses. We practiced this sequence until data for 540 houses were obtained. After the screening process, we omitted the incomplete responses, and the study received only 511 valid observations to run the analysis. The geographical identification of houses in the target location was identified using ArcGIS software (Esri, Redland, CA, United States) to show sample house points on the map, as shown in Figure 5. The intention of the survey was not just to generalize the effect of slums on rental value, but also emphasize to identify the perspective of homeowners living around slum areas. The respondents were asked to rate the potential nuisance they experience in living in the vicinity of slums. Additionally, the residents’ judgments were questioned regarding the effects of the proximity of slums on the property rental value.

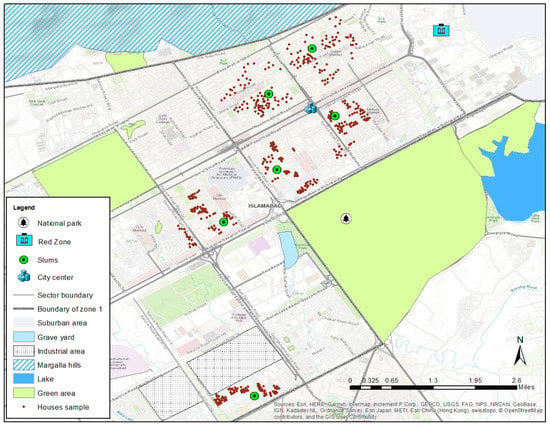

Figure 5.

Map of the sampling points in the study area (Source: Author’s own creation).

5. Empirical Results

The results of the analysis interpreted the ‘t-values,’ statistics, and coefficients, with the significance level of explanatory variables included in both linear and semi-log models, are represented in Table 3. Both linear and semi-log models indicated a high explanatory power of R2 = 0.935 and R2 = 0.906, respectively, and the explanatory variables revealed the approximate effects in both models proposed by this study. The estimated effect of slum areas on property rental values was the key area of interest. Both models’ results indicated that the distance from slums was a positive sign, as rental values increased as the distance increased from the slum areas. In the semi-log model to estimate the premium or discount on rent for a housing unit, an original rental value of PKR 58,036.38 (sample’s mean rental value) was recorded. While keeping other variables constant, a unit change in one of the explanatory variables estimated the change in the rental value by changing one unit in the independent variables in the form of premiums or discounts, as presented in the last two columns of Table 3. Using the ratio of the new rental value to the original, we can compute the exponent 1 by changing X1 to X1 + 1, which is denoted by eβ in the semi-log model shown in Table 3. The value of the discount or premium of a rental price, for a unit with an original price of 58,036.38 PKR, can be determined by changing X1 to X1 + 1, while keeping all other characteristics constant, and computed by exp.β1 − 1 × 58,036.38. The value of the significant variables is listed in the last column of the semi-log model in Table 3.

Table 3.

Showing linear and semi-log models.

The rent discount for the housing unit that is one km closer to slum areas is PKR 7196, all other attributes remaining constant in the semi-log model, and approximately 12.4% of the house rental value increases by increasing the distance between the housing unit and slum area by one km (see Table 3). Thus, interestingly, the houses close enough to slums that they are visible were affected more intensely, with up to 20% decrease in the rental value, according to the semi-log model. On the other hand, according to the linear model, the rental value increased by PKR 7613 for the same house located one kilometer farther away from the slum areas. The house unit size is the strongest explanatory variable to predict the house rent, with the highest ‘t-value’ = 30.90 in the linear model and 20.60 in the semi-log model, among all other independent variables. The findings of the linear model show that by increasing the house size by one square yard, the rental price increases by PKR 150, while the semi-log model results display an increase of PKR 116 with the same house size. Contrary to expectations, the TV lounge does not show a significant effect on the house rental values in both models. Hence, both models place equal importance on the Lawn, with an approximate t-value of 5.08 in the linear model and 5.86 in the semi-log model, as well as a premium of PKR 5184 and 6848, respectively. The houses occupied by single tenants enhance the rental value by 9.90%, as compared to houses occupied by multiple tenants. The wide and concreted street contributes a 4.10% increase in house rental values, and the greenbelt also boosts them by up 9.60%. Furthermore, the distance to the CBD shows adverse effects in both models: The rent decreases by PKR 1521 in the linear and by PKR 2,437 in the semi-log model, when the distance between the housing unit and CBD increases by one kilometer. The distance to the Markaz sector and the distance to the park, as expected, significantly adversely affect rental values in both models.

Distance Rings

The distance rings concept has been applied to estimate the magnitude of the value effect using external amenity and disamenity in the specific areas of slums. The usage of the distance ring helps identify the house unit’s location in each ring, selecting sample houses for study and comparing the results of the property value effects on each ring by increasing the distance from an external disamenity. Several researchers have used the different scale of distance rings to measure the impact of externalities on the property value [66], using distance rings of a distance of 250 m and a range of 250 m, while assessing the externality effects of the peace wall. Muhammad [65] considered four rings with a distance of 200 m each to evaluate the proximity effects of open sewer disamenity in Rawalpindi. This study also applied the method of rings and used three distance rings. The sample houses, located within 250 m, are considered to be in the first ring; the houses at a distance of 250 to 500 meters away are considered to be in the second ring, and houses within a radius of 500 m to 1 km are in ring 3. This study has examined both the linear model and semi-log model to investigate the location and distance effects of slums on rental values. Here, Equations (2) and (3) show the control variables and use dummy variables in both models to replace the distance variable.

Here, Table 4 presents the regression results of the distance ring damage based on the linear and semi-log models. The basis of both models is taken to be ring one, with a distance of 250 m. The results of the linear model demonstrate that ring two houses (250 to 500 m distance) rental values were PKR 3173 greater, as compared with the houses of ring one, which means that residents are willing to pay more rent for the houses situated away from the slum areas. Similarly, the rental prices of houses in ring three were PKR 5613 higher, showing the same trend, i.e., that the higher the house’s distance from slums, the higher the rent, as people are willing to pay more rent for the same kind of house, located away from the slum neighborhoods. Conversely, the semi-log model demonstrates that houses located in ring two receive a PKR 2785 premium on the rental value, and houses located at a distance of 250 to 500 m experience an increase in the rental value of 4% if the other attributes are constant. Additionally, the house rental values increase by up to PKR 5513 in ring three, which means that the house rent increases by 9.50% for being more than 500 m away from the slum areas.

Table 4.

Showing rings of slums/linear and semi-log models.

6. Discussion, Conclusion, and Policy Implications

The primary objective of this research study is to investigate city development and sustainable urban planning, as well as the negative impact of slum area disamenity on the property valuation of suburban and posh areas in the Islamabad region, Pakistan. It is among the few studies in the Pakistani context with the aim of examining the relationships among the selected variables. An upshot of this study is that it is the first to attract the attention of city planners and urban development officials to address problems associated with the external disamenity of slum areas. The hedonic pricing technique’s multivariate scope conveys accurate information on the transacted rental prices of houses about various observable or latent factors [73,85]. The distance of houses from slum neighborhoods and other environmental comforts play a vital role in determining the rental price. It is evident that the slum areas represent ecological problems faced by residents, such as the environment, pollution, crimes, and internal comfort factors [90]. This study has examined the effects of these factors on rental values, which is vital for resolving the problems posed by slum areas in order to achieve the goal of sustainable development in the region [39,91]. The results are helpful for government officials and city planners to address the problems posed by slums, which is vital for sustainable development and urban planning. The findings are useful for the future planning of city development as well. Responsible officials can take advantage of the results of this study to make better decisions about city development and sustainable urban planning. The primary objective of this research study focused on the investigation of city development and sustainable urban planning, as well as the negative impact of slum area disamenity on house rental values in the Islamabad region, Pakistan. It is among the few studies in the Pakistani context with this aim of examining the relationships among the selected variables. The hedonic pricing model provides an alternative and additional holistic method for the analysis of housing prices and valuation structures, as well as property values, by encompassing the environmental externalities [39,54]. This (HP) method typically investigates and interprets the buyer’s utility, which signifies and maximizes the ultimate human aspiration in the market environment [65]. The city developers and government officials might better understand the fundamental determinants of a market and how purchasers decide on whether the house or property is worth acquiring or not. It can bring consumers’ mindsets closer to those of property developers by building a bridge between the purchasers and the developers, and this can be used for obtaining thoughtful feedback on pricing decisions and real estate investments [35,63]. The hedonic pricing model is an advanced technique of real estate valuation in Western housing and urban development markets [43,51,92]. Substantial needs of housing in the neighborhood of underdeveloped areas and slums, and the avoidance of unconcealed asymmetries within the local real estate market might provoke reliable and consistent estimations [18]. Thus, prudently selected population areas and designed explanatory variables could help minimize potential biases by enhancing the power of the explanatory variables of both models’ results. This study’s results indicate that the semi-log model’s estimation provides house pricing that is more accurate than that of the linear pricing model. In this study, house rental pricing and valuation is the structural vector, with multiple attributes associated with the location and environment [40,50,63]. The findings reveal that a bundle of attributes impact on house pricing, such as the green space, proximity to slums, external environment, and location of the dwelling units [39,44,93]. The distance from the surrounding areas of slums is a vital factor in determining house rental prices. Purchasers’ prefer to rent a house away from slum areas, and this vividly portrays the customers’ pragmatic bent.

This research study extends its applicability to the neighborhood of slums and house rental values in the real estate market of Islamabad, Pakistan [1,94]. The results of this study supported a well-established concept in the housing economics literature, and it indicated that poor dilapidated neighborhoods generate negative externality impacts on the property values of surrounding residential properties. In particular, slum areas exerted adverse externality effects on house rental values, by around 12%. The evidence of the hedonic study, conducted by Song. and Zenou (2012) on the disamenity effects of dilapidated urban villages on the property values in Shenzhen, China, showed a house rental price loss of $23 USD for every one meter closer to urban villages [27]. Thus, to identify the reasons for external disamenity effects, a survey is carried out to obtain feedback from the residents of slum areas. Respondents are asked to rate the potential nuisance they experienced as neighbors of slum areas, and 56% of the respondents claimed that the crime rate is high in slum areas, 63% of respondents indicated that the noise level is high, and 66% of respondents perceived that slum areas could negatively affect property value. In conclusion, interpreting the survey results, respondents mostly complained that the externality of slums is causing crime, noise, pollution, and environmental issues.

The same question is asked of property dealers, and they replied that it is difficult for them to sell or rent a house near slum areas, because of the fear; people are reluctant to live near slum areas. The respondents are further asked for the reason why slums emerged in Islamabad, and 23% of respondents mention the poor planning in the construction of the city, 20% indicate encroachments on state land, and 20% of residents expressed that it was due to the poor policy adopted by the local government. At last, the respondents are asked for suggestions to deal with slum areas in the city. Almost 30% of respondents suggested the relocation of the slum areas to another place, 25% believed that the government should upgrade the existing slums by providing better infrastructure facilities, and 23% of respondents mentioned that the government should shut down the slum areas. The local government authorities should implement policies to deal with the problems arising from the slum externalities, and the socio-economic aspects of house rental values and residents’ behavior should be addressed through the survey process. This study also recorded the opinions of local experts on city development and urban planning to address issues associated with slum areas. This study placed a high priority on the documentation of the feedback of the officials from capital development authorities, who are responsible for city development and urban planning in Islamabad, Pakistan. The need to resolve problems associated with slums was brought to their attention, as it is critical for city development. The government officials replied that they have plans to solve slum issues in the future, and the government is allocating funds to resolve such issues for sustainable development in Islamabad, as it is the capital city. The government officials admitted that it is essential to address the slum problems in the city for sustainable development.

It is an important debate in the context of Pakistan. Some researchers [17,95] believed that the government officials should revitalize the underdeveloped slum areas, as people are living under poor conditions, and it is the responsibility of the government to provide better living conditions for their residents to have a secure and better quality of life. These measures will have a positive impact on nearby residents, and it will negate the wrong image of the externalities of such slums/Katchi abadis. As displayed in the survey of this study, these impoverished/slum areas are the primary concern of the local population and residents, as they dislike the nearby slum localities. Typically, people do not like to rent a house there, as it has crime, noise, pollution, energy issues, and other environmental problems, and house rental prices are negatively affected [90]. However, rural slums near Islamabad have little capability of being able to adjust and accommodate rural workers and migrants [96]. The capital government should improve the infrastructure of slum localities, instead of demolishing it in response to their negative spillover impacts. Alternatively, the officials of the government should take steps to develop the slums and temporary residential areas, to improve their living conditions of slum residents and also of the population of Islamabad city.

The slums’ negative externalities could be reduced by separating the areas of slums from residential areas. The City Development Authority (CDA), working on city development projects, should relocate slums from residential sectors to MUSP (modern urban shelter project) sites, developed in suburban areas in Islamabad. In such areas, they could have property rights and other necessary facilities, such as a door-to-door water supply connection, sanitary and sewerage system, and pavement of the existing street network. A study conducted by Timpanaro et al. (2017) examined urban agriculture as a tool to check the metropolitan sustainable social recovery of slum areas in Italy [97]. Urban garden construction enhances the environmental, social, and economic aspects of urban slum area residents. Duchemin, Wegmuller, and Legault (2008) carried out research in Montreal, Canada on urban agriculture using multi-dimensional tools on the development of poor neighborhoods [98]. Community gardening projects and the program of collective gardens in various geographical locations resulted in collective social developments and a substantial gain for economically underprivileged population groups in the city. The findings of this study suggested that the government should relocate the slums to MUSP sites, and they should start projects of urban agriculture to boost up the slum areas. The government should improve slum residents’ socio-economic conditions for sustainable urban development.

There are a great deal of vacant land areas in the suburbs of Islamabad near MUSP sites, which could be utilized for agriculture as a tool to upgrade the multidimensional aspects of slum areas [97,98]. This study evidenced that the greenbelt and quality of the street significantly reduce the adverse impact of slums and enhance the rental value of proximate houses. Another study also supported these research finding on the greenway in Indianapolis, Indiana, showing an increase of 10% in residential property values, while this proposed study evidenced a 9.6% increase of greenbelts. An earlier study of Heckert and Mennis (2012) examined the effects of urban green sites on the value of properties in Philadelphia city, Pennsylvania, and it revealed that properties with green belts had a sharp increase in values, unlike properties in non-green zones [99]. A previous study examined the effects of trails and greenbelts on housing values nearby San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas and revealed an increase of 5% on house values, with greenbelts and trails [100]. Hence, this study suggests that the authorities of city planning and development consider more greenbelts and wide concreted streets, as these things would enhance the environmental effects, rental values, and scenic beauty around residential areas. These measures would be helpful for sustainable city development and reduce the adverse impacts of slum areas on neighborhood property values.

The findings of this study might address the issues of poor urban planning in the context of the external disamenity effects of urban slums on the housing market. This study examined the mechanism of slum effects on the urban housing market and elaborated the determinants to reduce the adverse impacts of slums on the housing market, and it also provided precise tools to improve urban slum areas to achieve the goal of sustainable urban development. A productive research direction might be the monitoring of individuals’ understanding and feedback on an external environmental amenity that increase housing prices in Pakistan. The feedback of residents of slums and Katchi abadis at various developmental stages can be investigated to learn the essential and pleasant endowments in the vicinities of such housing areas. Another research direction, which might be intensely explored, could be the examination of how individuals of diverse socio-economic background exercise their decision to purchase a house that might have an environmental value.

Author Contributions

T.H. has conceptualized, drafted methodology, collected data and analyzed, while J.A. has written literature and edited original manuscript, Z.W. supervised this study, and M.N. has reviewed the edited manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Nanjing Agricultural University, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are well informed about the objectives of this current study, and they have provided consent and declared that they have no competing interest.

Data Availability Statement

This study has used primary data to support the findings of this proposed research study, and this current research has included data in this. This data is primary in nature and data received and analyzed to support the findings of this research study can be approached/available upon request from the corresponding of this article.

References

- Hasan, A.; Raza, M. The Pakistan Context; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2009; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Adnan, M.N.; Safeer, R.; Rashid, A. Consumption based approach of carbon footprint analysis in urban slum and non-slum areas of Rawalpindi. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.J.M.; Aslam, M.; Othman, N. Sustainable Tourism in the Global South: Communities, Environments and Management; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.-H. Can community-based tourism contribute to sustainable development? Evidence from residents’ perceptions of the sustainability. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 368–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttenheim, A.M. The Sanitation Environment in Urban Slums: Implications for Child Health. Popul. Environ. 2008, 30, 26–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D′Souza, V.S. Socio-Cultural Marginality: A Theory of Urban Slums and Poverty in India. Sociol. Bull. 1979, 28, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredemeier, K.; Berenbaum, H.; Brockmole, J.R.; Boot, W.R.; Simons, D.J.; Most, S.B. A load on my mind: Evidence that anhedonic depression is like multi-tasking. Acta Psychol. 2012, 139, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahabir, R.; Crooks, A.; Croitoru, A.; Agouris, P. The study of slums as social and physical constructs: Challenges and emerging research opportunities. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2016, 3, 399–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-HABITAT. State of the World’s Cities 2010/2011—Cities for All: Bridging the Urban Divide; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, I.A.; Khan, M.S. Developing Sustainable Agriculture in Pakistan; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyan, C. Life in the Slums. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 1976, 11, 1450–1451. [Google Scholar]

- Laurent, G. Guns, Slums, and “Yellow Devils”: A Genealogy of Urban Conflicts in Karachi, Pakistan. Mod. Asian Stud. 2007, 41, 515–544. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Triana, E.; Afzal, J.; Biller, D.; Malik, S. Greening Growth in Pakistan through Transport Sector Reforms: A Strategic Environmental, Poverty, and Social Assessment; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ruback, R.B.; Begum, H.A.; Tariq, N.; Kamal, A.; Pandey, J. Reactions to Environmental Stressors: Gender Differences in the Slums of Dhaka and Islamabad. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2002, 33, 100–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, B.; Stoker, T.; Suri, T. The Economics of Slums in the Developing World. J. Econ. Perspect. 2013, 27, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleemi, A.R.; Khaliqui, H.; Faisal, A. Challenges and Patterns of Seeking Primary Health Care in Slums of Karachi: A Disaster Lurking in Urban Shadows. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2018, 30, 479–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreutzmann, H. Islamabad, living the plan. Südasien-Chronik-South Asia Chronicle 2013, 3, 136. [Google Scholar]

- Olthuis, K.; Benni, J.; Eichwede, K.; Zevenbergen, C. Slum Upgrading: Assessing the importance of location and a plea for a spatial approach. Habitat Int. 2015, 50, 270–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, G.; El-Shimy, H.; Ragheb, A. Land for Poor: Towards Sustainable Master Plan for Sensitive Redevelopment of Slums. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 216, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawadzki, S.J.; Mainzer, S.; McLaughlin, R.A.; Luloff, A.E. Close, but not too close: Landmarks and their influence on housing values. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doss, C.R.; Taff, S.J. The influence of wetland type and wetland proximity on residential property values. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 1996, 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, C.; Welke, G. The Effect of HVTLs on Property Values: An Event Study. Int. Real Estate Rev. 2017, 20, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, P.M.; Gill, G.L.; Hanning, A.; Cox, C.A. Estimating the Effects of Brownfields and Brownfield Remediation on Property Values in a New South City. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2017, 35, 143–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Simons, R.A.; Li-jun, F.; Fen, Z. The Effect of the Nengda Incineration Plant on Residential Property Values in Hangzhou, China. J. Real Estate Lit. 2016, 24, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Grislain-Letrémy, C.; Katossky, A. The impact of hazardous industrial facilities on housing prices: A comparison of parametric and semiparametric hedonic price models. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2014, 49, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichert, A.; Small, M.; Mohanty, S. The impact of landfills on residential property values. J. Real Estate Res. 2009, 7, 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Zenou, Y. Urban villages and housing values in China. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2012, 42, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, E.; Choi, Y.; Yoon, H. The impact of the Gyeongui Line Park project on residential property values in Seoul, Korea. Habitat Int. 2016, 58, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.H.; Wu, C.; De Sousa, C. Examining the economic impact of park facilities on neighboring residential property values. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 45, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, D.K.; Park, C.; Kim, H.G.; Jung, T.Y.; Kim, S. Park accessibility impacts housing prices in Seoul. Sustainability 2017, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.; McCord, M.; McCluskey, W.; Davis, P.T.; McIlhatton, D.; Haran, M. Effect of public green space on residential property values in Belfast metropolitan area. J. Financ. Manag. Prop. Constr. 2014, 19, 117–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Humphreys, B.R. The impact of professional sports facilities on housing values: Evidence from census block group data. City Cult. Soc. 2012, 3, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojanek, R.; Gluszak, M. Spatial and time effect of subway on property prices. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2018, 33, 359–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, R.C.; Berger, M.C.; Blomquist, G.C. Measuring Amenity Benefits from Farmland: Hedonic Pricing vs. Contingent Valuation. Growth Chang. 2006, 28, 438–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Y.; Sohngen, B.; Babb, T. Valuing urban wetland quality with hedonic price model. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 84, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, A.M., III; Herriges, J.A.; Kling, C.L. The Measurement of Environmental and Resource Values: Theory and Methods; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Impacts of urban environmental elements on residential housing prices in Guangzhou (China). Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 422–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L. Assessing amenity effects of urban landscapes on housing price in Hangzhou, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaitham, S.; Fukuda, A.; Vichiensan, V.; Wasuntarasook, V. Hedonic pricing model of assessed and market land values: A case study in Bangkok metropolitan area, Thailand. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamowicz, W.; Louviere, J.; Williams, M. Combining Revealed and Stated Preference Methods for Valuing Environmental Amenities. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 1994, 26, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, R.; Flores, N. Contingent Valuation: Controversies and Evidence; Department of Economics: San Diego, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Arrondo, R.; Garcia, N.; Gonzalez, E. Estimating product efficiency through a hedonic pricing best practice frontier. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, D. Using a spatial hedonic analysis to evaluate the effect of sea view on hotel prices. Tour. Manag. 2018, 65, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidoye, R.B.; Chan, A.P.C. Critical review of hedonic pricing model application in property price appraisal: A case of Nigeria. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, S. Hedonic Prices and Implicit Markets: Product Differentiation in Pure Competition. J. Polit. Econ. 1974, 82, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J. The value of a south-facing orientation: A hedonic pricing analysis of the Shanghai housing market. Habitat Int. 2018, 81, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griliches, Z. Price indexes and Quality Change: Studies in New Methods of Measurement; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Nazir, N.N.M.; Othman, N.; Nawawi, A.H. Role of Green Infrastructure in Determining House Value in Labuan Using Hedonic Pricing Model. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jang, S.; Kang, S.; Kim, S. Why are hotel room prices different? Exploring spatially varying relationships between room price and hotel attributes. J. Bus. Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanfranco, B.A.; Castaño, J.P. Hedonic Pricing of Grass-Fed Cattle in Uruguay: Effect of Regional Resource Endowments. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 70, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housing, U.S.D.O.; Development, U. Housing in the Seventies Working Papers 1 [and] 2: National Housing Policy Review; Department of Housing and Urban Development: Washington, DC, USA, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu-Ansah, A. Construction and Application of Property Price Indices; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lemons, J.; Brown, D.A. Sustainable Development: Science, Ethics, and Public Policy; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pagourtzi, E.; Assimakopoulos, V.; Hatzichristos, T.; French, N. Real estate appraisal: A review of valuation methods. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2003, 21, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champ, P.A.; Boyle, K.J.; Brown, T.C. A Primer on Nonmarket Valuation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hidano, N. The Economic Valuation of the Environment and Public Policy: A Hedonic Approach; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J.M.; Wu, J.J. The Oxford Handbook of Land Economics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, S.; Crompton, J.L. The Impact of a Golf Course on Residential Property Values. J. Sport Manag. 2007, 21, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, D.; Chern, W.; Hitzhusen, F.; Randall, A. Property-Value Impacts of an Environmental Disamenity: The Case of Landfills. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2001, 22, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippova, O.; Rehm, M. The impact of proximity to cell phone towers on residential property values. Int. J. Hous. Mark. Anal. 2011, 4, 244–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, C.; Lewis, L.Y. Examining the economic impacts of hydropower dams on property values using GIS. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90 (Suppl. 3), S258–S269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, R.; Saginor, J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Environmental Contamination and Positive Amenities on Residential Real Estate Values. J. Real Estate Rese. 2006, 28, 71–104. [Google Scholar]

- Loerzel, J.; Gorstein, M.; Rezzai, A.M.; Gonyo, S.; Fleming, C.S.; Orthmeyer, A. Economic Valuation of Shoreline Protection Within the Jacques Cousteau National Estuarine Research Reserve; U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2017.

- Yinger, J. Housing and Commuting: The Theory of Urban Residential Structure: A Textbook in Urban Economics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, I. Disamenity impact of Nala Lai (open sewer) on house rent in Rawalpindi city. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2017, 19, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCord, J.; McCluskey, M.; McIhatton, W.; Haran, M.; Davis, P.; McCord, W.J. Belfast’s iron(ic) curtain: “Peace walls” and their impact on house prices in the Belfast housing market. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2013, 6, 333–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.; McGrattan, C. The Northern Ireland Conflict: A Beginner’s Guide; Oneworld Publications: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Preez, M.D.; Balcilar, M.; Razak, A.; Koch, S.F.; Gupta, R. House Values and Proximity to a Landfill in South Africa. J. Real Estate Lit. 2016, 24, 133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Akinjare, O.A.; Ayedun, C.A.; Oluwatobi, A.O.; Iroham, O.C. Impact of Sanitary Landfills on Urban Residential Property Value in Lagos State, Nigeria. J. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 4, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewusi, A.; Onifade, F. The effects of urban solid waste on physical environment and property transactions in Surulere local Government area of Lagos state. J. Land Use Dev. Stud. 2006, 2, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Neelawala, P.; Wilson, C.; Athukorala, W. The impact of mining and smelting activities on property values: A study of Mount Isa city, Queensland, Australia. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2013, 57, 60–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinar, Y. From Conflict to Peace. Rehabilitation Process in the Phase of Transforming Conflict—The Case of Northern Ireland; Anchor Academic Publishing: Surrey, BC, Canada, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Qu, X. Spatial interactive effects on housing prices in Shanghai and Beijing. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpezzi, S. Hedonic pricing models: A selective and applied review. Hous. Econ. Public Policy 2002, 67–89. [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist, R.B. Estimating the Demand for the Characteristics of Housing. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1984, 66, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, D.A.; Cloutier, N.R. The Impact of Small Brownfields and Greenspaces on Residential Property Values. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2006, 33, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Thibodeau, T.G. Analysis of Spatial Autocorrelation in House Prices. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 1998, 17, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y. Hedonic Housing Price Theory Review. In Urban Morphology and Housing Market; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 11–40. [Google Scholar]

- Soler, I.P.; Gemar, G. Hedonic price models with geographically weighted regression: An application to hospitality. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicego, M.; Baldo, S. Properties of the Box–Cox transformation for pattern classification. Neurocomputing 2016, 218, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.; MacKinnon, J.G. Estimation and Inference in Econometrics; OUP Catalogue: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Zelenak, L. Figuring Out the Tax: Congress, Treasury, and the Design of the Early Modern Income Tax; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Din, A.; Hoesli, M.; Bender, A. Environmental variables and real estate prices. Urban Stud. 2001, 38, 1989–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Bu, X.; Qin, Z. Spatial effect of lake landscape on housing price: A case study of the West Lake in Hangzhou, China. Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, M.S. Government of Paper: The Materiality of Bureaucracy in Urban Pakistan; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CDA. Facts & Statistics. Available online: http://www.cda.gov.pk/about_islamabad/vitalstats.asp (accessed on 14 November 2018).

- Riddell, K. Islam and the Securitisation of Population Policies: Muslim States and Sustainability; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rehman, A.; Shaikh, B.T.; Ronis, K.A. Health care seeking patterns and out of pocket payments for children under five years of age living in Katchi Abadis (slums), in Islamabad, Pakistan. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butt, M.J.; Waqas, A.; Iqbal, M.F.; Muhammad, G.; Lodhi, M.A.K. Assessment of Urban Sprawl of Islamabad Metropolitan Area Using Multi-Sensor and Multi-Temporal Satellite Data. Arabian J. Sci. Eng. 2012, 37, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, S.; Wu, F.; Webster, C. Urban villages under China’s rapid urbanization: Unregulated assets and transitional neighbourhoods. Habitat Int. 2010, 34, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.-M. The Housing Market and Tenure Decisions in Chinese Cities: A Multivariate Analysis of the Case of Guangzhou. Hous. Stud. 2000, 15, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, M.; Kiel, K. A Survey of House Price Hedonic Studies of the Impact of Environmental Externalities. J. Real Estate Lit. 2001, 9, 117–144. [Google Scholar]

- Garrod, G.D.; Willis, K.G. Valuing goods’ characteristics: An application of the hedonic price method to environmental attributes. J. Environ. Manag. 1992, 34, 59–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sander, H.A.; Polasky, S. The value of views and open space: Estimates from a hedonic pricing model for Ramsey County, Minnesota, USA. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Wahid, J. Rapid urbanization: Problems and challenges for adequate housing in Pakistan. J. Sociol. 2014, 2, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zenou, Y.; Ding, C. Let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water: The role of urban villages in housing rural migrants in China. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timpanaro, G.; Foti, V.; Scuderi, A.; Toscano, S.; Romano, D. Urban agriculture as a tool for sustainable social recovery of metropolitan slum area in Italy: Case Catania. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Greener Cities for More Efficient Ecosystem Services in a Climate Changing World 1215, Bologna, Italy, 12–15 September 2017; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Duchemin, E.; Wegmuller, F.; Legault, A.-M. Urban agriculture: Multi-dimensional tools for social development in poor neighbourhoods. Field Actions Sci. Rep. J. Field Actions 2008, 1, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckert, M.; Mennis, J. The Economic Impact of Greening Urban Vacant Land: A Spatial Difference-In-Differences Analysis. Environ. Plan. A 2012, 44, 3010–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asabere, P.K.; Huffman, F.E. The relative impacts of trails and greenbelts on home price. J. Real Estate Financ. Econ. 2009, 38, 408–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).