Abstract

For residents of a city that hosts a mega sport event, sport involvement can be associated with their perceptions of the impacts and quality of life (QoL) gained from that event. The attributes of mega sport events, with multiple sports in one competition, are linked with the level of residents’ sport involvement, specifically their interest in and identification with sports, which can foster more positive perceptions and enhance the anticipated QoL from the games. Despite the importance of sport involvement on the support for a mega sport event, most studies have mainly focused on how perceptions of the impact from the event influence support based on social exchange theory (SET). Hence, this study examined how sport involvement affected the relationships among impact perceptions, QoL, and support for the 2018 PyeongChang Winter Olympic Games. Structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to examine the hypotheses in the proposed model, using a sample of 301 Korean residents. The results revealed that sport involvement had a positive effect on event impact perceptions and QoL, which, in turn, significantly influenced support for the Olympic Games in the pre-stage. The study suggests that sport involvement can leverage support for a mega sport event through the creation of positive perceptions of the impacts of the event.

1. Introduction

As a mega sport event, the Olympic Games can have a significant impact on sustainable community development in the host country, specifically economic, social, and cultural development [1,2]. The success of the Games relies heavily on the local community recognizing the benefits of hosting the Games [3]. In recent years, cities bidding to host the Games have faced opposition from residents despite the potential for sustainable community development.

Residents’ opposition is mainly based on fears about the potential high cost for the host city and nation [4]. Residents’ support for the event is affected by their impact perceptions, which are an important factor in increasing local support for the Olympic Games [3]. Thus, exploring the process of how residents’ support is affected by impact perceptions is more important and relevant than ever before. Residents are an important resource for the Games, providing volunteer services and contributing to the event’s atmosphere through their interactions with spectators, athletes, and other stakeholders [5]. Quality of life (QoL) is affected by these interactions and can serve as a platform for support for the Games [6]. Therefore, scholars have paid attention to the role of QoL in the hosting of a mega sport event. Previous studies have examined the relationships among impact perceptions, QoL, and community support [7,8,9], with most of the research utilizing social exchange theory (SET). Although SET is a useful theory to explore the relationships in terms of perceived benefits and costs for residents, several scholars suggest that using SET in conjunction with another theory can provide a better understanding of the relationship between impact perception and residents’ support [10,11,12].

The Olympic Games are a sporting event in which multiple sporting competitions feature high-level performances in hundreds of different sports. Given these unique characteristics, local interest and personal involvement in sports may affect support for the event [13]. Residents who are highly involved in sports could potentially help to establish a positive link between the sporting events and the attitudes of community members, in terms of behavioral intentions [14]. In other words, residents with the highest level of involvement in sports are likely to accept positive information regarding the sporting event while screening out negative information [15]. Thus, the examination of sport involvement with SET may facilitate a better understanding of residents’ perception of impacts, QoL, and support toward mega sport events. In this respect, sport involvement should be taken into consideration in the comprehensive model to understand how residents’ perceptions of impacts on QoL of mega sport events are related to their support for the Games. Despite several studies that have explored the relationships among impact perception, QoL, and support, the role of local sport involvement in these relationships remains relatively unexplored. Thus, the purpose of this study is to analyze the effect of sport involvement on the relationships at the pre-event stage. More specifically, we will focus on the 2018 Winter Olympic Games in PyeongChang and discuss the following research question: What are the structural relationships among sport involvement, impact perceptions, QoL, and support for the Olympic Games during the pre-event stage? The findings of this study can contribute to understanding the mechanism regarding the effect of sport involvement on support for mega sport events and provide directions for sport event managers and policy makers to enhance strategic planning for sustainable community development through hosting mega sport events.

2. Theoretical Backgrounds and Hypothesis

2.1. Social Exchange Theory and Sport Involvement

SET has been applied as a useful theoretical framework in a number of studies that sought to understand and explain why residents support mega events and how residents react to mega events [16]. SET is predicated on the notion that if individuals receive benefits without any unexpected costs, they will participate in the exchange process and support relevant efforts [14]. If residents perceive benefits, then the degree of support will increase [3]. Because SET can simultaneously explain the positive and negative impacts gained by a mega event, it is helpful toward providing a better grasp of residents’ support of mega events which is a critical component in destination development [15].

In general, studies that utilized SET focused on dimensions such as economic, environmental, and sociocultural factors [16], when examining and explaining the perceptions of mega sport events among residents and the relationship of these dimensions to residents’ support. Most of the studies using SET as their theoretical framework found that the positive and negative impact perceptions of mega events affect in a corresponding manner residents’ support for mega events [8,17,18,19,20]. However, even though SET is widely applied in various research studies [3], SET as applied to research problems related to residents’ perceptions about sport event impacts or other tourism aspects has some limitations. SET is based on the assumption that individuals participate in exchange if they receive more benefits than costs in the exchange; however, the nature of the benefits and costs from the exchange can be ambiguous. For example, residents may prioritize environmental protection over economic gain or may prioritize living standards over environmental concerns [7]. In addition, the type of interaction during the exchange process can be unintentional, involuntary, or even intangible [13]. McGehee and Andereck [21] criticized the application of SET from two perspectives: a) that individuals will always choose what they believe is best for themselves, and b) that residents may change their perceptions of what is most beneficial or what is not beneficial at all. In other words, depending on the timing of the choice, what an individual considers a benefit or cost can change. Látková and Vogt [10] suggested utilizing SET along with another theory to provide a deeper understanding and perspective regarding the attitudes and reactions of residents, and to overcome the limitations of SET. When investigating reasons and factors that can influence the impact perceptions of residents, many researchers have implemented SET with another theory such as the theory of reasoned action [22], social identity theory [23], or Max Weber’s theory of formal and substantive rationality [12]. These theories were used to explain which factors affect residents’ impact perceptions. Based on these theories, many studies used extrinsic factors (e.g., seasonality, density) and intrinsic factors (e.g., demographics, community attachment) to determine the factors that have an effect on residents’ impact perceptions.

In addition, residents’ values and beliefs can affect their perceptions [24]. Involvement theory demonstrates that a person’s involvement with an object of interest is a determinant of how the person’s expectations are formed and the object is evaluated [25]. Beliefs and expectations for objects of interest can be affected by level of involvement with the object [26]. As noted by Zaichkowsky [27], involvement is “a person’s perceived relevance of the object based on inherent needs, values, and interest” (p. 342). The level of involvement is revealed by individual identification towards the object of interest. In addition, the level of involvement affects a series of behavioral decisions and can act as an important moderator that explains the relationships between the variables within the behavioral decisions of individuals [28]. McDaniel and Chalip [29] asserted that a viewer’s enjoyment of the television coverage of the Olympics is affected by that viewer’s level of interest in the sports game that is being played during the Olympics. In addition, visitors who are very involved with the event’s programs and activities can be more satisfied and intent to return to the destination in the future [30]. Involvement can be referred to as the degree of commitment regarding an object, action, or experience [31], perceived personal relevance [32], and level of psychological connection [33]. Therefore, the sports competitions can be the object of involvement in a multi-sport event such as the Olympics and can be used as antecedent to the image, perception, and attitude toward mega sport events [34].

As noted by Beaton et al. [35], “sport involvement is present when individuals evaluate their participation in a sport activity as a central component of their life and provides both hedonic and symbolic value” (p. 128). In their study, sport involvement was separated into multi-faceted constructs, including symbolic value, hedonic value, and centrality. Sport involvement can be regarded as the assessment of how much sport activity is at the center of a person’s life, including watching and participating in various sport events. Therefore, sport involvement can affect the inherent expectation formation and evaluation process of the event’s outcomes (e.g., economic, social, environmental) among residents with different levels of involvement. In addition, the level of sport involvement can influence the perceptions of an individual’s QoL [36]. Much of the existing research has proven that sports activity can play a critical role in improving QoL [37]. Furthermore, the level of sport involvement is closely linked to an individual’s amount of sport activity [38], and sport involvement can affect QoL [36]. If involvement is the level of psychological connection [33] and the degree of a person’s involvement is relative to an experience or object [31], the level of an individual’s involvement developed through a sports activity and experience can be seen as a preliminary predictor of QoL.

2.2. Categories and Classification of Mega Sport Event

Event impacts feature tangible and intangible dimensions, including economic (e.g., increase in employment, increase in tourist attraction), environmental (e.g., promotion of environmental issues, improvement of the local environment), and sociocultural (e.g., improvement in cultural identity, community cohesion) components [39,40]. In addition, knowledge development and sport development have been discussed within the area of sociocultural impacts [41,42,43].

Specifically, studies about economic impacts have examined the interrelationship between economic outcomes and tourism development, which could lead to economic development. From the perspective of traditional sport event studies, economic impacts include an increase in employment, a business investment, or other change that could bring economic growth such as tourism development [44,45]. Environmental aspects include problems that can change the environmental profile of the area, including recycling, improvement in air quality, awareness of the importance of the environment, and the formation of a new environmental policy [22]. According to Prayag et al.’s research [22], positive environmental impacts perception of the 2012 London Olympic Games strengthened residents’ support for the Games. Furthermore, knowledge development can be brought about by community service, as well as engagement in new programs, which can make human capital development possible [1,46]. Recent studies have suggested an increased interest in the effects of intangible benefits from hosting mega events [47], and in the socio-cultural factors that stem from event hosting [39]. Key studies on impact perceptions in sport event studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Studies on the impact or legacy perceptions of mega sport event.

2.3. The Relationship between Sport Involvement, Impact Perceptions, QoL, and Support

A range of factors can affect the event impact perceptions of residents [55]. According to SET, demographic variables can affect residents’ impact perceptions because these characteristics cause individuals to have different experiences regarding the impacts of mega events [21]. Furthermore, individuals may oppose development through mega events that go against their beliefs and values, considering the attitudes of residents based on SET [56]. For example, residents who think highly of cultural heritage and environmental protection tend to have a negative perception of development through mega events [24]. Therefore, individual beliefs and values have an important effect on the perception of sport event impacts. From a psychological perspective, individual beliefs and values can influence an individual’s interest and relevance with that object alluding therefore to the importance of those factors in any evaluation of that object [57]. Since sports is a primary component of the Olympics, an individual’s sport involvement may influence that individual’s perception of the Olympics. Furthermore, the Olympic Games is not a single sport event but a combination of several sport events, leading it to be classified as a multi-sport event. Therefore, general sport involvement can be related to an individual’s level of psychological connection to a multi-sport event like the Olympic Games [33] and can influence one’s expectations toward the Olympic Games as an object of interest.

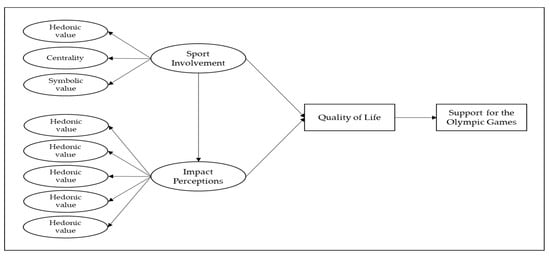

Previous studies also indicate that people with high level of sport involvement are likely to participate in habitual sport activities and thus enhance QoL from physical, mental benefits through activity in sports [58]. Additionally, individual’s involvement with leisure activity participation can also lead to enhance QoL as the activity can be an important factor in the meaning of the individual’s life [59]. Some previous research into the association of impact perceptions with support, makes the general assumption that support is a direct outcome of positive and negative impacts [60]. Positive impact perceptions can increase support among residents. Even though there has been much research within the sport event domains into residents’ perception of impacts and support for events [22,60], the studies using QoL as an outcome of event impact perceptions and a predictor of event support have been limited [6]. Hiller and Wanner [42] found that the potential effect of QoL perception on event support. In addition, Ma and Kaplanidou [6] noted the influence of resident evaluations of event impacts on QoL and the positively influence of QoL on event support. Looking at the latter studies and examining the findings from an SET perspective, QoL can act as an exchange platform between impact perceptions and support [2,39]. For example, if residents perceive that event impacts influence their QoL, then residents will recognize improved QoL as a benefit, and residents’ support for the event will increase as a result [6]. Using empirical and theoretical evidence, a research model with the following hypotheses was formulated (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Proposed research model.

Hypothesis 1.

Sport involvement will be positively associated with event impact perceptions.

Hypothesis 2.

Sport involvement will be positively associated with QoL perceptions.

Hypothesis 3.

Impact perceptions will be positively associated with QoL perceptions.

Hypothesis 4.

QoL perceptions will be positively associated with resident support for the Olympic Games.

Hypothesis 5.

Impact perceptions will mediate the relationship between Sport Involvement and QoL.

Hypothesis 6.

QoL will mediate the relationship between sport involvement and support for the Olympic Games.

Hypothesis 7.

QoL will mediate the relationship between event impact perceptions and support for the Olympic Games.

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

This study used Survey Korea, an online market research company, to e-mail the questionnaire to potential participants/residents in South Korea. The survey company has a panel membership of more than 18,000 members in South Korea. The members are a diverse group intended to reflect the South Korean population. The initial English-language questionnaire was translated into Korean. Accuracy of the translations was checked by Korean professors with both English and Korean language proficiency. After confirming the correspondence of meaning between the two versions, the survey company emailed it to a randomly selected sample of 1000 panel members. All data was collected in March, 2017, and the research procedures and surveys received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval. There were 301 respondents to the e-mail survey. Of the 301 respondents, 181 were male (60.1%) while 120 were female (39.9%). The average age of respondents was about 41 years of age (SD = 9.83). Most of the respondents (78%, n = 235) were between 21 and 40 years of age. The subjects of this study were mainly residents of South Korea’s six big cities: Seoul, Incheon, Daejeon, Daegu, Gwangju and Busan. The subjects of past studies on the relationships among impact perceptions, QoL and support for the Olympic Games were residents of the host city. The reason, however, that subjects of this study were not limited to residents of the host city, but rather reflected the host country, was that South Korea is a very small country, and the support, desire to host, and decision-making of the central government toward the host city have greatly helped the small city of PyeongChang in Gangwon-do province. Furthermore, the opinions and support of the entire South Korean population were an important deciding factor in the decision to host the Olympics.

3.2. Measurement Scales

This study used the existing literature’s scales to measure sport involvement, impact perceptions, QoL, and support, for the Olympic Games. A five-point Likert scale was employed, as recommended by Beaton et al. [35], to measure nine sport involvement items. Those nine items were categorized into three aspects of involvement (e.g., hedonic value, symbolic value and centrality). In order to measure the impact perceptions of the Olympic Games, five sub-domains (e.g., economic impacts, sociocultural impacts, environmental impacts, tourism impacts, sport development impacts) were used, and 15 items were used based on the existing literature [6,8]. All items were presented on a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.” QoL was also measured with one statement from Kaplanidou et al. [6] that measured overall QoL perceptions. The reason for using a single item to measure overall QoL is that the main interest was in the overall quality of life evaluation. In addition, the multi-dimensional scales of QoL feature high correlation among the sub-dimensions of items and the holistic evaluation item used in this study [6]. In addition, an overall QoL rating using a single item that reflects individuals’ diverse value and preference is useful when the purpose of measuring QoL is to assess in a broad perspective rather than in the detailed description of the constructs [61]. Support for the Olympic Games was also measured on a five-point Likert scale using one item adapted from Prayag et al. [22] and Kaplanidou et al. [6].

3.3. Data Analysis

To examine the hypothesized model, the collected data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 and AMOS 25.0. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using AMOS 25.0 was utilized to test the reliability and validity of the constructs. The hypothesized relationships in the model were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM). Descriptive statistics, internal consistency, and Pearson bivariate correlation coefficients were computed before testing the proposed model. The average variance extracted (AVE) and the significant factor loadings were used. When the AVE value for the construct was higher than the squared correlations between the respective constructs, the discriminant validity was achieved. The multiple fit indices were used to assess the goodness of fit and parsimony of the structural model, including a chi-square (χ2) value with related degrees of freedom (df), mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI) [62]. CFI should exceed 0.90 and the RMSEA value in the range of 0.05 to 0.08 indicates a reasonable error of approximation although a closer fit is smaller than 0.05. [62,63].

4. Results

The internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, indicating and all variables had a Cronbach’s alpha level over 0.70, which indicates high internal reliability. Descriptive statistics for the sport involvement, impact perceptions, QoL, and support for the Olympic Games are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

4.1. Measurement Model

As noted by Hair [64], the hierarchical component model allows the researcher to utilize a more parsimonious model with better goodness of fit indices. Thus, the hierarchical component model was employed to achieve the purpose of this study: identify the structural relationships among sport involvement, impact perception, QoL, and resident support. The data analysis was conducted on the basis of Rindskopf and Rose [65].

A hierarchical approach using a CFA model fit comparison for the second order factor structures was followed for the test procedure. Results are presented in Table 3. First, the analysis of sport involvement indicated that both model 3 and 4 had slightly better fit indices than model 1, although all were acceptable except for model 2. In selecting the best model, the second order factor was a better fit to consider than other models if it had acceptable fit indices compared to a first order factor model’s correlated structure that could present problems with discriminant validity [66]. In choosing the best model from an equivalent model we took into account theoretical backgrounds [67]. Considering the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the best model overall was the second order structure since the lower the AIC, the better the model [68].

Table 3.

Model fit comparison.

Second, the analyses of the impact perceptions revealed that models 1, 3, and 4 were acceptable. The AIC of model 4 was 233.116, which indicated the best model. Given the above evidence and criteria for the best model, the second order structures of the impact perceptions from conceptual and empirical evidence could be considered a better model than others. Thus, we considered the second order structure as the best model to test the structural model. Table 4 shows that discriminant validity is appropriate between constructs because the square root of the AVE for each construct in the pair was larger than the correlations between the pairs of constructs [65].

Table 4.

Discriminant validity and correlations.

The convergent validity was assessed using standardized factor loadings, AVE values, and construct reliabilities. Table 5 shows standardized factor loadings, standard error, AVE values, and composite reliability. All standardized factor loadings greater than 0.50, and all AVEs exceeded 0.50. Composite reliability was greater than 0.70, which confirmed convergent validity of measurement scale [65].

Table 5.

Convergent validity.

4.2. Construct Relationships

One of main purposes of the study was to explore the relationship between sport involvement, event impact perceptions, QoL and support for the Olympic Games. Table 6 exhibits the goodness of fit measures of the model with χ2, CFI, and RMSEA, and indicates acceptable values for the structural model validity [65,69]. H1 and H2 postulated that sport involvement would be positively correlated with impact perceptions and QoL. The results indicated that sport involvement showed a significant and positive effect on impact perceptions (β = 0.51, t = 7.38, p < 0.01) and QoL (β = 0.30, t = 4.42, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 and H2 were supported. H3 postulated the positive effect of impact perceptions on QoL. The results showed a statistically significant relationship of event impact perceptions with QoL (β = 0.29, t = 4.41, p < 0.01). H4 predicted that QoL would positively affect support for the Olympic Games. The results showed a significant relationship of QoL with support for the Olympic Games (β = 0.26, t = 4.45, p < 0.01). Hence, H3 and H4 were supported.

Table 6.

Hypothesis testing results and standardized path loadings.

4.3. The Mediating Effects

The mediation anlysis including BC boostrapping and the Sobel test was used to to investigate the mediating role of impact perceptions and QoL between sport involvement and support. The both methods for tesing mediation effects are more suitable than mediation analysis using a single method [70,71]. The results indicated that sport involvement had significant indirect effect toward support (sport involvement → QoL → support; β = 0.117; 95% boostrap CI (0.193 to 0.560); Z = 2.642, p < 0.01) and QoL (sport involvement → impact perceptions → QoL; β = 0.152; 95% boostrap CI (0.262 to 0.710); Z = 3.245, p < 0.01) via QoL and impact perceptions. QoL significantly mediated impact perceptions toward support (Impact perceptions → QoL→ Support; β = 0.077; 95% boostrap CI (0.077 to 0.110); Z = 2.780, p < 0.01) (see Table 7). Sport involvement and impact perceptions had no significant direct effects on support, indicating full mediating role of QoL. These results supported H5, H6 and H7. Thus, QoL can play a key role in predicting support.

Table 7.

Results of mediating role estimation of quality of life (QoL) and impact perceptions.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the effect of sport involvement on support for the Olympic Games in the pre-event stage. Specifically, we explored the structural model of support for the Olympic Games, between sport involvement, and event support and featuring impact perceptions, and QoL as mediators in the model relationships. Our exploration was based on two theories: SET and involvement.

First, although both the first-order model and the second-order model showed acceptable model fit indices, the second-order model was employed to examine the structural relationships among constructs. Our results indicated that the constructs in the first-order model are co-varying, which is inconsistent with Kaplanidou et al.’s previous study [6], which identified the differential effects of impacts on QoL. The high correlation among the constructs results in multicollinearity [8]. As noted by Ma and Kaplanidou [6], the higher-order model allows to distinguish the first-order constructs, identifying the effect of different impacts on QoL and support without facing multicollinearity issues.

Second, we found that as sport involvement increased, impact perceptions became more positive. Such a result is in line with the findings of previous studies that have identified people who were highly involved in the sport are likely to be more satisfied with a sport event [34,55]. In particular, the findings imply that a high level of sport involvement affects positively event impact perceptions. One possible explanation for this result is that prior interest and experience with sports can cause residents to positively associate with attributes of the Olympic Games, given that the Olympic Games combine various sporting events. In other words, one’s interest in sports and the meaning and importance of sports in one’s life can be linked to the positive perception of the potential benefits of hosting the Olympic Games; specifically, residents link specific attributes of the Games (as multiple sport events) to the personal value of sports. The findings of this study extend prior findings about impact perceptions of hosting a mega sport event by suggesting the effect of sport involvement on impact perceptions of the Olympic Games and QoL [8,22].

Third, we examined the structural model, including sport involvement, impact perceptions, QoL, and support. Sport involvement positively influences impact perceptions and QoL, and then QoL has an impact on support. Event impact perceptions mediated the relationship between sport involvement and QoL, which can be explained by social exchange theory. The residents who were into sports, evaluated the event impacts positively before they observed any QoL benefits. Based on social exchange theory, positive QoL expectations functioned as a platform of positive exchange. Our findings also indicated that QoL can be simultaneously influenced by sport involvement and impact perceptions. Such findings can also be interpreted through expectations regarding the benefits of the Olympic Games and past positive sports experiences [6,8]. As sport involvement grows within the individual, the events impacts are viewed more positively and evaluated to have a more positive impact on the residents’ QoL. According to SET, if residents understand that positive benefits can be gained from hosting a mega sport event, then they link this understanding with their QoL and as a result are more supportive of hosting such an event [54]. Consistent with previous studies [6,8], findings of this study indicated that QoL can be an important factor in the relationships between sport involvement, impact perceptions, and support for mega sport events. Additionally, QoL perceptions can be directly affected by sport involvement, resulting in increased support. A high level of sport involvement means that there is strong interest and some degree of participation in sports activities, which can also lead to a positive effect on QoL [36]. Because sport involvement reveals how important one considers sports and how interested one is in sports, it can affect people’s perceptions of the impact the Olympic Games may have on QoL and, in turn, generate more support.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

Within the structural model of support for the Olympic Games, the association of sport involvement with QoL positively influences support for the Olympic Games. Residents who have both a high QoL and high sport involvement are more likely to support the Games as a multi-sport event with various points of attachment (e.g., interest in sports and identification with sports). This means that if participation or interest in sports is strong, an individual’s QoL will be high and he or she will have a positive perception of the impact of the Games. Although the benefits of sports activity, such as improvement in health, social connections, and psychological happiness [72] might not be directly linked to the perception of impact of the Olympic Games, such positive benefits may indirectly affect the relationships among impact perceptions, QoL, and support. The results of this study add to previous findings on these relationships [34,56] by suggesting that sport involvement plays an influential role in generating support for the Olympic Games because of its impact on both impact perception and QoL in the pre-event stage.

5.2. Managerial Implications

Given the current challenge of resident resistance in cities bidding to host mega sport events (e.g., Calgary 2026 just had a referendum that rejected its bid for the 2026 Olympic Games), this study can serve as an advising tool to target or nurture societies where sport involvement is high. This approach can create support for hosting large events through appreciation for the event’s impacts. Practically, experts serving on Olympic committees must be aware that sport involvement has an effect on support for hosting a mega sport event. Generally, organizers carry out various events and promotions prior to hosting a mega sport event, such as the Olympic Games, in order to garner support and interest. During these events, using promotions and strategies to increase sport involvement, while also raising interest in the specific events within the larger event, will help create focus and support toward the mega sport event.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study has a few limitations. First, this study’s data was collected using panels maintained by an online survey company. Thus, there may be issues regarding how the population’s general characteristics can be reflected. Specifically, the panels held by the online survey company are composed of those who have access to the internet. Future studies should conduct surveys of those who actually reside in the city or country hosting the mega sport event. Furthermore, future studies could utilize secondary data to reflect actual changes in economic and sociocultural numbers in conjunction with psychological factors, such as perceptions of the Olympic Games, which would improve the study’s accuracy by combining subjective factors, such as impact perceptions and QoL, with objective figures (e.g., economic, sociocultural, and QoL values).

Second, this study measured sport involvement as general sport involvement. Because the subject of this study was the Winter Olympic Games, measuring involvement with winter sports activities may reveal a different perspective. Furthermore, future studies on the support for mega sport events should reflect the effects of past experiences of hosting mega sport events on the impact perceptions, QoL, and support of residents. In addition, consideration must also be given to the differences between the social and cultural characteristics of nations and the extent of development within each nation. For example, soccer is not simply considered a sport but a sociocultural phenomenon, and even a religion, in Brazil [73]. Thus, the level of involvement with soccer in Brazil will be higher than in other countries, which has an effect on the support for sport events, such as the 2014 World Cup [73].

Third, this study considered residents’ impact perceptions based on five event impacts because the purpose of this study was to analyze the structural relationship in the model instead of the association of sport involvement with each impact perception. Thus, we employed second-order constructs to model a generic concept of impact perceptions. Although second-order modeling in this study was effectively used to examine the relationships among constructs, the impact of sport involvement on each impact perception may vary. For example, the aspects of sport development, such as improved sport infrastructures and development of local sports teams, can be more closely associated with residents who are highly involved in sports [42]. Thus, additional research should be conducted to demonstrate the impact of sport involvement on each impact construct in the model of support for mega sport events, providing other empirical evidence of sport involvement. Furthermore, future studies examining the moderating role of sport involvement in the associations among impact perceptions, QoL, and support can provide more comprehensive outcomes in the context of mega sport events studies.

Finally, this study did not take into account the attitude of the residents toward the organizing committee or government associated with the Olympic Games. The favorable attitude of residents toward the organizing committee or government in the bidding and planning process may influence impact perceptions, arousing organizational citizenship behavior in regard to support. As explained by Zoghbi and Espino [74], the attitudinal environments associated with partners and tasks influence organizational citizenship behavior. Thus, favorable attitudinal environments connected with the organizing committee can help to increase organizational citizenship behavior among residents, in addition to affecting positive perceptions and support for the event. Thus, future study should consider organizational citizenship behavior as a crucial factor, or construct, in the model of support for mega sport events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and K.K.; data curation, C.K. and K.K.; formal analysis, C.K.; methodology, C.K.; project administration, C.K.; writing—original draft, C.K.; writing—review and editing, C.K. and K.K.

Funding

Publication of this article was funded in part by the University of Florida Open Access Publishing Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kaplanidou, K.; Karadakis, K. Understanding the legacies of a host Olympic city: The case of the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games. Sport Mark. Q. 2010, 19, 110. [Google Scholar]

- Waitt, G. Social impacts of the Sydney Olympics. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 194–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Kendall, K.W. Hosting mega events: Modeling locals’ support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2006, 33, 603–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Olympics Have a Host-City Problem. Available online: http://www.cbc.ca/sports/olympics/olympics-host-city-problem-1.4414207 (assessed on 23 November 2017).

- Jones, C. Mega-events and host-region impacts: Determining the true worth of the 1999 Rugby World Cup. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2001, 3, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Karadakis, K.; Gibson, H.; Thapa, B.; Walker, M.; Geldenhuys, S.; Coetzee, W. Quality of life, event impacts, and mega-event support among South African residents before and after he 2010 FIFA world cup. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 631–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.; Var, T. Resident attitudes toward tourism impacts in Hawaii. Ann. Tour. Res. 1986, 13, 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Kaplanidou, K. Legacy perceptions among host Tour de Taiwan residents: The mediating effect of quality of life. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Kaplanidou, K. Effects of Event Service Quality on the Quality of Life and Behavioral Intentions of Recreational Runners. Leis. Sci. 2018, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Látková, P.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ attitudes toward existing and future tourism development in rural communities. J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 50–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Host perceptions of tourism: A review of the research. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.C.; James, J. The psychological continuum model: A conceptual framework for understanding an individual’s psychological connection to sport. Sport Manag. Rev. 2001, 4, 119–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balduck, A.L.; Maes, M.; Buelens, M. The social impact of the Tour de France: Comparisons of residents’ pre-and post-event perceptions. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2011, 11, 92–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions on tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 1992, 19, 665–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriotis, K.; Vaughan, R.D. Urban residents’ attitudes toward tourism development: The case of Crete. J. Travel Res. 2003, 42, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andereck, K.L.; Valentine, K.M.; Knopf, R.C.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ perceptions of community tourism impacts. Ann. Tour. Res. 2005, 32, 1056–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Chi, C.G.; Dyer, P. Locals’ attitudes toward mass and alternative tourism: The case of Sunshine Coast, Australia. J. Travel Res. 2010, 49, 381–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Ramkissoon, H. Power, trust, social exchange and community support. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 997–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Ap, J. Residents’ perceptions towards the impacts of the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games. J. Travel Res. 2009, 48, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGehee, N.G.; Andereck, K.L. Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. J. Travel Res. 2004, 43, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Nunkoo, R.; Alders, T. London residents’ support for the 2012 Olympic Games: The mediating effect of overall attitude. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Gursoy, D. Residents’ support for tourism: An identity perspective. Ann. Tour. Res. 2012, 39, 243–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Jaafar, M.; Kock, N.; Ramayah, T. A revised framework of social exchange theory to investigate the factors influencing residents’ perceptions. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2015, 16, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.; Roese, N.; Zanna, M. Expectancies; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 211–238. [Google Scholar]

- Taifel, H. Social Categorization, Social Identity, and Social Comparison; Academic Press: London, UK, 1978; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Measuring the involvement construct. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiesz, T.B.; Bont, C. Do we need involvement to understand consumer behavior? Adv. Consum. Res. 1995, 22, 448–452. [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel, S.R.; Chalip, L. Effects of commercialism and nationalism on enjoyment of an event telecast: Lessons from the Atlanta Olympics. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2002, 2, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Beeler, C. An investigation of predictors of satisfaction and future intention: Links to motivation, involvement, and service quality in a local festival. Event Manag. 2009, 13, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, M.J.; Brown, G. An empirical structural model of tourists and places: Progressing involvement and place attachment into tourism. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, G.; Chick, G. The social nature of leisure involvement. J. Leis. Res. 2002, 34, 426–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, D.C.; Ridinger, L.L.; Moorman, A.M. Exploring origins of involvement: Understanding the relationship between consumer motives and involvement with professional sport teams. Leis. Sci. 2004, 26, 35–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, G.; Smith, A.; Assaker, G. Revisiting the host city: An empirical examination of sport involvement, place attachment, event satisfaction and spectator intentions at the London Olympics. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, A.A.; Funk, D.C.; Ridinger, L.; Jordan, J. Sport involvement: A conceptual and empirical analysis. Sport Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 126–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Jordan, J.S.; Funk, D.C. The role of physically active leisure for enhancing quality of life. Leis. Sci. 2014, 36, 293–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.J.; Halpenny, E.; Spiers, A.; Deng, J. A prospective panel study of Chinese Canadian immigrants’ leisure participation and leisure satisfaction. Leis. Sci. 2011, 33, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dishman, R.K.; Sallis, J.F.; Orenstein, D.R. The determinants of physical activity and exercise. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplanidou, K. The importance of legacy outcomes for Olympic Games four summer host cities residents’ quality of life: 1996–2008. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2012, 12, 397–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. The contribution of the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games to green economy. Sustainability 2013, 5, 3581–3600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Henry, I. Evaluating the London 2012 Games’ impact on sport participation in a non-hosting region: A practical application of realist evaluation. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 685–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiller, H.H.; Wanner, R.A. The psycho-social impact of the Olympics as urban festival: A leisure perspective. Leis. Stud. 2015, 34, 672–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.C.; de Sousa-Mast, F.R.; Gurgel, L.A. Rio 2016 and the sport participation legacies. Leis. Stud. 2014, 33, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansero, E.; Puttilli, M. Mega-events tourism legacies: The case of the Torino 2006 Winter Olympic Games—A territorialisation approach. Leis. Stud. 2010, 29, 321–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.; Mjelde, J.W.; Kwon, Y.J. Estimating the economic impact of a mega-event on host and neighbouring regions. Leis. Stud. 2017, 36, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preuss, H. A framework for identifying the legacies of a mega sport event. Leis. Stud. 2015, 34, 643–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Page, S.J. Progress and prospects for event tourism research. Tour. Manag. 2016, 52, 593–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.C.; Rotherham, I.D. Residents’ changed perceptions of sport event impacts: The case of the 2012 Tour de Taiwan. Leis. Stud. 2016, 35, 616–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.M.; Barbanti, V.J.; Chelladurai, P. Support of local residents for the 2016 Olympic Games. Event Manag. 2017, 21, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gursoy, D.; Sharma, B.; Panosso Netto, A.; Ribeiro, M.A. 2014 FIFA World Cup in Brazil: Local residents’ perceptions of impacts, emotions, attachment, and their support for the event. In Proceedings of the 5th Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management Conference, Beppu, Japan, 18–21 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pappas, N. Hosting mega events: Londoners’ support of the 2012 Olympics. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2014, 21, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorde, T.; Greenidge, D.; Devonish, D. Local residents’ perceptions of the impacts of the ICC Cricket World Cup 2007 on Barbados: Comparisons of pre-and post-games. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Shipway, R.; Cleeve, B. Resident perceptions of mega-sporting events: A non-host city perspective of the 2012 London Olympic Games. J. Sport Tour. 2009, 14, 143–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Gursoy, D.; Lee, S.B. The impact of the 2002 World Cup on South Korea: Comparisons of pre-and post-games. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnitzer, M.; Walde, J.; Scheiber, S.; Nagiller, R.; Tappeiner, G. Does the young residents’ experience with the Youth Olympic Games influence the support for staging the Olympic Games? Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 30, 220–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, L.N.; Thapa, B.; Ko, Y.J. RESIDENTS’PERSPECTIVES OF A WORLD HERITAGE SITE: The Pitons Management Area, St. Lucia. Ann. Tour. Res. 2009, 36, 390–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havitz, M.E.; Mannell, R.C. Enduring involvement, situational involvement, and flow in leisure and non-leisure activities. J. Leis. Res. 2005, 37, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.; Park, N.; Seligman, M.E. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: The full life versus the empty life. J. Happiness Stud. 2005, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y. Leisure and quality of life in an international and multicultural context: What are major pathways linking leisure to quality of life? Soc. Indic. Res. 2007, 82, 233–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G.; Alders, T. Residents’ Perceptions on Event Impacts and Relocation Intentions. In Proceedings of the Meeting of Mobilities and Sustainable Tourism, Gréoux les Bains, France, 24–27 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Priebe, S.; Huxley, P.; Knight, S.; Evans, S. Application and results of the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA). Int. J. Soc. Psychiatr. 1999, 45, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, T.M.; Feinstein, A.R. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA 1994, 272, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective, 7th ed.; Pearson: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA; London, UK, 2010; pp. 629–686. [Google Scholar]

- Rindskopf, D.; Rose, T. Some theory and applications of confirmatory second-order factor analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1988, 23, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hocevar, D. Application of confirmatory factor analysis to the study of self-concept: First-and higher order factor models and their invariance across groups. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 97, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koufteros, X.; Babbar, S.; Kaighobadi, M. A paradigm for examining second-order factor models employing structural equation modeling. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 633–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Software review: Software programs for structural equation modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulaik, S.A.; James, L.R.; Van Alstine, J.; Bennett, N.; Lind, S.; Stilwell, C.D. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol. Bull. 1989, 105, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Hoffman, J.M.; West, S.G.; Sheets, V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruseski, J.E.; Humphreys, B.R.; Hallman, K.; Wicker, P.; Breuer, C. Sport participation and subjective well-being: Instrumental variable results from German survey data. J. Phys. Act. Health 2014, 11, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.M.; Barbanti, V.J. Support for the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. J. Phys. Educ. 2015, 2, 66–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Zoghbi Manrique de Lara, P.; Espino Rodríguez, T.F. Organizational anomie as moderator of the relationship between an unfavorable attitudinal environment and citizenship behavior (ocb). An empirical study among university administration and services personnel. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 843–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).