Abstract

Directive 2014/95, in force since 2017, is the first European step that requires undertakings to provide mandatory non-financial information. The regulation concerns sustainability information, such as environmental, social, and employee information, human rights, and anti-corruption and bribery matters, and the disclosure of diversity policies for board members. According to the theoretical framework of Integrated Assessment (IA), the study aims to examine the expected impact of the Directive within the analysis of empirical evidence before the mandatory approach. This allows, on the regulatory side, evaluation of the quality of the regulation, therefore, whether the law achieves its policy objectives (i.e., if it fills the gap in the sustainability disclosure) and, on the firms’ side, to identify where companies have to invest to meet the legal requirements. The oil and gas sector is chosen as a sample for the study, because it is one of the most advanced sectors in sustainability disclosure, and if the regulation could impact on this sector, it would be the same for less-informed ones. The findings reveal a fair level of completeness of non-financial information, however, there are some areas that have to be improved to achieve the requirements of the Directive. The results also show the presence of overlap between financial and sustainability reports. In conclusion, the quality of regulation is good because it will also increase sustainability disclosure in an advanced sector, such as oil and gas, even if there is an open point on the location of information; companies in this sector will have to invest more in environmental and employee information in future years to comply with the Directive.

1. Introduction

In October 2014 the European Union issued Directive 2014/95, known as the Directive on Disclosure of Non-financial Information for Large Undertakings and Groups (all “public interest entities” with more than 500 employees). The Directive, in force since 2017, amended the previous Directive 2013/34 that defined the Framework of the Management Commentary and required large-sized companies to draft and publish a non-financial statement (NFS) referring to sustainability disclosure. Briefly, the Directive has an effect on the aspects concerning information contents, thus promoting the completeness of sustainability information and, as regards the organizational aspects, requires all information to be communicated in a structured way in the companies’ reporting system, either in a section of the financial report or by means of a separate report. The theoretical framework of this study is the Integrated Assessment (IA), that is “as a tool that does not only improve the quality of legislation, but also helps to better consider consequences of the legislation on three dimensions: the economy, environment and society” [1,2].

In particular, in the sphere of accounting regulation [3,4,5,6,7], the study focuses on the expected impact of the Directive within the analysis of empirical evidence before the mandatory approach. According to this framework, the study contributes to the debate on the quality of regulation [8] because it examines whether the Directive is a good regulation, i.e., if it achieves its policy objectives of improving sustainability disclosure. Therefore, analysis consists of the study of sustainability disclosure of companies along the reference lines of the content (what) and organization of the information among the company reports (where) before the Directive. The empirical analysis has been carried out in the oil and gas sector, since it is considered evolved in terms of disclosure [9,10,11]. According to the IA, if the regulation could impact on this sector, it would be the same for less-informed ones.

To this end, the study proposes a research methodology that will be replicable also in other sectors. The analysis, therefore, sets out to reply to these RQs (research questions):

- RQ1:

- What were the degree of completeness and the organization of sustainability disclosure before the Directive came into force?

- RQ2:

- Are there sustainability matters that firms have to invest in to achieve the Directive’s requirements, and if so, what are they?

After disclosing the theoretical background and carrying out a review of the current state of research in Section 2, the objectives defined by the regulation are examined in Section 3. The methodology developed to analyze the communicative behavior of companies is explained in Section 4, and Section 5 describes the findings. The study ends with discussion, conclusions and an overview on future achievable research areas by applying the research method adopted in this paper (Section 6).

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Theoretical Framework

The Integrated Assessment (IA) derives from the Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) process. More in detail RIA is a “policy tool used to examine and measure the likely benefits, costs and effects of new or existing regulation” [12]. It was introduced in the US in the late 1970s, but it has spread with the study, promotion, and implementation activities carried out by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) since 1995 [13,14]. RIA embraces all sectors of regulatory policy [15,16,17], including accounting. The field is accounting regulation as defined by Taylor and Turley “Regulation has been defined as the imposition of constraints upon the preparation, content and form of external reports by bodies other than the preparers of the reports, or the organisations and the individual for which the reports are prepared” [18].

RIA is related to the process dimension and the outcome of policy regulation. In this regard, the OECD suggests implementing RIA as a process [12,14]. The RIA process is a rational set of policy phases that contributes to evaluating alternatives and, essentially, aims to improve the capacity of policy-makers [19]. It consists in at least five steps: (1) identify the problem and define policy context and objectives; (2) identify all possible regulatory (or non-regulatory, i.e., guidelines) options; (3) identify and measure the expected impacts (costs and benefits) of the regulation; (4) public consultation; and (5) design regulation including enforcement, compliance, and monitoring mechanisms to evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the regulation. After adoption of the regulation the ex post RIA process will be implemented [6,20].

With the diffusion of RIA, awareness of the economic, social, and environmental aspects related to regulation has increased. This has led to an integrated vision of the regulatory action resulting in the definition of Integrated Impact Assessment (IIA) which means “an ex-ante impact assessment that aims to integrate in a coherent way the multiple impacts of government intervention. It aims to inform decision-making, enable arbitration between options and provide evidence of the anticipated effects of possible decisions” [15].

In summary, RIA/IIA or synonymously widely used in the Integrated Assessment (IA) literature [6,13,15,16,20] is used to evaluate the quality of regulatory policy [6,20]. IA is nowadays implemented in its integral form or partially (in the integral form all steps described above, from (1) to (5), are fulfilled, in the partial only some of them are put in practice) in numerous jurisdictions [21]. In light of the Sustainable Development Strategies, the EU views IA “as a tool that does not only improve the quality of legislation, but also helps to better consider consequences of the legislation on three dimensions: the economy, environment and society” [1,2].

As an instrument of learning, IA is formulated on the basis of empirical evidence and a central role is reserved for the methods for obtaining suitable data to assess the quality of regulation [1,6].

The paper applies the IA framework to the EU Directive on sustainability disclosure in order to evaluate the quality of regulation, i.e., to verify whether the regulation meets its policy objectives (if it fills the gap in the sustainability disclosure) within the analysis of companies’ reports in an ex ante phase. This focus is not on compliance with the law before it came into force but study of the ex ante state of the art allows judgement of the regulatory options: to simplify, if all companies are already disclosing all matters required by the law, the regulation will not be useful and it will break the IA framework.

2.2. Literature Review

Since the regulation of accounting is the strand of interest, the first aspect to be considered is the role of accounting in sustainability disclosure. In literature this aspect is examined according to two different perspectives [22]. The first, of a critical nature, maintains that the concept of sustainability has not been fully understood by the firms: if the concept is not internalized, any accountability instrument will be of little use both inside and outside the firm [23,24]. The second perspective is the managerial one, according to which corporate social responsibility (CSR) is considered a decision-making instrument of the firm [25] that enables managers to have more information, in addition to financial information. This additional information could enable managers to take more conscious decisions. According to this second perspective, the sustainability report (SR) is an instrument of communication towards the internal and external stakeholders [26] that gives legitimacy to the corporate activity in the social context where it operates.

There is also a successive point of view, more recent than the previous ones, according to which Baker and Schaltegger [27] consider CSR in the sphere of pragmatic philosophy. According to this point of view, CSR cannot be considered univocally and be assigned only one purpose a priori; on the contrary, it must be identified with the pragmatic behavior of the company and, therefore, can take on different roles in view of the operative objective it pursues. In this sense, the SR can take on the role conferred upon it by the compiler or its role can be established in the perspective of specific users or, again, the SR can be used to create a new communication channel with the stakeholders. In other words, the SR is an instrument to understand what the firms are doing, in concrete terms, regarding the topic of CSR.

According to Baker et al. [27], this study considers corporate social responsibility as a tool to understand “whether reports accurately represent organizational activities”. This point of view is in line with the objectives of the regulation (Directive 2014/95) which asks firms to disclose non-financial information in order to clearly explain the actual impact of business on society and on medium–long term global development (effective communication in terms of CSR). Thus, the regulation will lead firms to think about their behavior and it may inspire a change in the direction of a more sustainable way of doing things.

As described, the effective disclosure of CSR requires the evaluation of two inter-related aspects: the information content (what the firm is disclosing) and the structure of this information in the reporting system (where they are) (ref. RQ 1).

Since 1980 many surveys have been dealing with the comprehensiveness of the SR [22] besides the various initiatives promoted at international level to define non-mandatory standards on CSR subjects. Some examples are given below [11]: IFAC Sustainability Framework 2.0; ESG Framework and KPIs for ESG; SustainAbility Global Reporters Program; AccountAbility’s AA1000 Standards; ISO 26000—Guidance on social responsibility; IRCSA—Framework for Integrated Reporting; Guidelines of Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Standards; and The International Framework Integrated Reporting of International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC).

In the literature, academics have analyzed the content of the sustainability disclosure (what) under several points of analysis:

- The level of detail of the CSR information and the determinants of disclosure [28,29];

- The most emphasized areas of interest (i.e., environmental, social, diversity) and the space set aside for the main variables [30];

- The visual content of the SR, in terms of images and photos (visual communication) [31];

- The compliance of the SR with the previously mentioned guidelines [32] or compliance with specific national legislations (i.e., the French instance [33,34]);

- The quality of the disclosed information and of the SR [35,36]; and

- The relationship between the availability of data on CSR and firms’ CSR reputation [37].

These studies on the content of CSR disclosure have adopted different research methods (i.e., disclosure index, KPI—Key Performance Indicators, quality, content analysis). Nevertheless, no study on the quality of the accounting regulation on CSR has been carried out. This research area is underpinned. According to Sahabana, Buchholtz, and Carroll [38], a new research area is the analysis of the role and influence of the government (for us, the European Union) on institutionalization of the sustainability disclosure, consisting of the evaluation of whether the formal coercive pressure [39] modifies, and how, the attitude of companies towards the SR. Additionally, Hahn and Kühnen [40] indicate the role of the regulation on sustainability matters as a future research area to be examined in depth. Furthermore, Sulkowsky and Waddock [41] state that there will be benefits for firms from CSR requiring reporting throughout regulation and materiality. Finally, Habec and Wolkian [35], in their analysis on the quality of SRs in some European countries, come to the conclusion that where the national legislation imposes the legal obligation of sustainability disclosure, this will improve the quality of the SR.

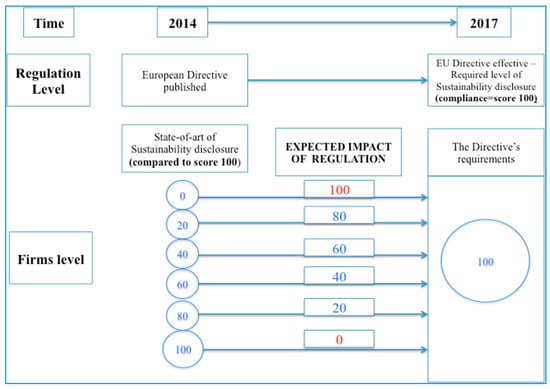

To fill the gap, the study uses the Integrated Assessment framework applied to a sustainability disclosure regulation (first RQ) in order to understand the expected impact of the Directive 2014/95 (Figure 1). Only few other studies have done the same ex ante analysis: one is a research on Italian-listed companies [42] and the other one is a recent study on Polish-listed companies in light of the Directive [43]. Compared to these papers, the current study focuses on a specific sector in a transnational perspective.

Figure 1.

Theoretical framework.

With regard to the second aspect, i.e., the structure of the information (where), there are various instruments available to communicate the sustainability information. In the literature, scholars initially studied the non-financial information stated in the financial reports (FR) [44,45]. Subsequently, research focused on stand-alone SRs and, finally, attention was directed to the integrated financial statements and the relations between the reporting systems (financial reports and sustainability reports) [10,46,47,48].

Nowadays the communication of environmental and social information occurs not only through the SRs, but also through media channels, social media, and web sites [22]. Nevertheless, for the purposes of this research, due to the requirements of the Directive, the focuses of the analysis are the written reports (financial and sustainability reports). The written reports are indeed the preferred instrument of the stakeholders [49]. This is because, being formal tools, they are characterized by higher accuracy in their preparation and they are the result of accountability systems which very often envisage recourse to national or international standards and are, therefore, considered more reliable. A large number of them are then submitted to external auditing.

In this context of different reporting systems (FR and SR) and with a proliferation of different documents (some enterprises have a separate report, others provide an embedded report) the risk is that the communication may not be transparent and clear, i.e., the decoupling of non-significant information, thus reducing the clarity of the documents for users, above all external ones, and making the comparability of information more complicated.

In fact, the Directive under examination underlines that the objectives of the regulatory intervention, as regards the structure of the information, focus on the accessibility of the non-financial information to the external users (i.e., an easy way) and it promotes accounting harmonization on sustainability topics.

The research, starting from the state of the art of where firms disclose sustainability information, aims to study whether there is an overlap between different reporting systems and what the step forward is (if there is one) from the European regulation.

3. Accounting Regulation on Sustainability in Europe

3.1. The Evolution from Voluntary Disclosure to Mandatory Disclosure

The accounting regulation on sustainability disclosure at the European Union level is recent, although the Union showed its sensitivity towards this topic some years ago (Table 1).

Table 1.

Accounting regulation in Europe on sustainability.

The definition of CSR suggested in the Green Paper (2001) [50] is: “the integration by the undertakings, on a voluntary basis, of the social and ecological concerns in their commercial operations and in their relations with the parties involved”. By this definition, which was the starting point, the regulator clearly expressed his/her will to promote an approach to “sustainable” undertakings.

In 2011, the new definition of CSR appears much more general and less accurate than the previous one “the responsibility of enterprises for their impact on society”. In 2011 the European accountability process for non-financial information starts with the Commission Communication “Single Market Act” in which companies are requested to provide more and transparent information on social and environmental aspects. The same request appears in the Communication of October 2011.

The European Parliament, in its resolutions of 2013, acknowledges that the sustainability disclosure is important to [51]:

- pinpoint the risks for sustainability and increase the confidence of investors and consumers;

- manage the transition to a global sustainable economy by combining long-term profitability, social justice, and protection of the environment; and

- measure, monitor, and manage the results of the undertakings and their important impact on society.

Additionally, the purpose of the Parliament, then set forth by issue of the Directive, consists in offering to all the investors and stakeholders a framework on sustainability policies that will be comparable at European level (accounting harmonization); for the consumers, the Directive would offer easier access to information on CSR.

This process of sustainability disclosure regulation is at seed level in Europe. Over 16 years the EU passed from a concept of voluntary CSR (2001) to the requirement (in 2014, applicable as from 2017) for a mandatory non-financial information statement for the large enterprises.

The European context is also characterized by different situations of the member states. As a matter of fact, in most European countries there are no legal SR requirements, whereas other countries have introduced some disclosure requirements regarding sustainability in their national legislation; some examples are France, UK, Sweden, and Denmark, where a regulatory sustainability disclosure obligation already existed.

The early stage of the Directive 2014/95 was the Modernization Directive of 2003. This Directive states that: “large undertakings shall—to the extent necessary for a good understanding of their financial position—include in their annual reports the most important non-financial performance indicators for the company’s business, such as information on environmental and employee interests, in the company’s analysis of the development of its business and of its financial position” [52] but, according to a survey conducted by the Federation of European Accountants in 2008, this early regulation did not improve the sustainability disclosure in financial reports [53], because it was perceived as a “non-coercive” rule.

In this European scenario, the objective of the Directive 2014/95 is that of harmonizing the sustainability reporting system at European level both in terms of what information is to be communicated (what) and where it must be arranged (where). The following paragraph describes the regulation in detail.

3.2. Directive 2014/95

According to the theoretical framework, the study analyses the regulatory process and the specific requirements of the Directive 2014/95 in order to reply to the research questions.

Firstly, the analysis focuses on the regulatory process of the Directive. All documents published by the EU Commission on this process were studied [54,55,56,57]. The outcome is that the regulatory process of the Directive could be described as the following (authors’ formulation):

- 1.

- Public consultations (public consultation on disclosure of non-financial information; multi-stakeholder roundtables; constitution of expert group; external study on the topic).

- 2.

- Problem definition:

- inadequate transparency of non-financial information (both in terms of quantity and quality information);

- lack of diversity in the board.

- 3.

- Policy objectives:

- increase the number of companies reporting on sustainability issues;

- increase the quality of information; and

- enhance the board diversity.

- 4.

- Regulatory options. The study of the Commission Services provides the different impacts of these possible policy options: (a) no policy change; (b) Non-financial Statement in the Annual Report with minimum requirements on the content; (c) detailed reporting (mandatory, report or explain, voluntary); and (d) creation of an EU Reporting Standard.

Preferred one out of a, b, c, and d: b.

- 5.

- Analysis of the impact assessment of the regulatory policy chosen:

- expected benefit;

- estimated costs (derived from the external study); and

- other impacts (i.e., social, environmental, etc.).

- 6.

- Monitoring and evaluation: Directive’s implementation in each Member State (i.e., different choices/approaches of Member States), compliance with EU requirements and the evaluation of the anticipated impacts (i.e., whether they occur or not, and the market reaction).

This process, except for point 6, is an ex ante assessment that aims to understand the need for a new regulatory tool to improve sustainability information at European level and if necessary, how to design it.

In the IA framework the paper applies an ex ante impact assessment that will clarify, firstly, if there is the problem of low transparency of non-financial information in the oil and gas sector and its entity (point 2 above—what) and secondly the state of the art of where companies decide to disclose their sustainability information (where). This second point leads to reflect on the regulatory options (point 4 above).

The final design of the Directive is then described. The recipients of the regulatory requirement are the “public interest entities” who have a minimum number of 500 employees. This is because, in the EU’s opinion, their impact is higher on the community and involves more Member States. This point is validated in the literature in the first theoretical contribution on the social responsibility of economic activities, i.e., H. R. Bowen’s thought expressed in 1953 and who has been unanimously recognized as the father of corporate social responsibility; he raises awareness that firms, above all the large ones, are centers of power and, through strategies, decisions, and pursued actions, they involve and influence the whole of the surrounding society [58].

In terms of content of the Directive (what), the document states: “The undertakings affected will be required to disclose information on several non-financial matters, to the extent necessary for an understanding of the undertaking’s development, performance and position, and of the impact of its activities” [51]. The minimum level of non-financial information should concern the following matters or topics:

- a. Environmental;

- b. Social and employee;

- c. Respect for human rights;

- d. Anti-corruption and bribery;

- e. Diversity; and

- f. Business model.

For each one of the topics (a–d) companies shall provide:

- a. The description of the policies, including due diligence processes implemented;

- b. The outcomes of these policies;

- c. The risks relating to those matters and how the company manages those risks; and

- d. The non-financial key performance indicators relevant to the particular business.

For any information envisaged by the Directive, the principle is “comply or explain”.

The concept of materiality is the basis of non-financial disclosure which means, as pointed out in paragraph 8 of the preamble to the Directive [51], that information should be provided in “relation to matters that stand out as being most likely to bring about the materialization of principal risks of severe impacts, along with those that have already materialized. The severity of such impacts should be judged by their scale and gravity”. The materiality concept is explained in the Guidelines on non-financial reporting published by the European Commission (“Guidelines”) [59]; it refers to the goal that “A company should focus on providing the breadth and depth of information that will help stakeholders understand its development, performance, position and the impact of its activities. The non-financial statement is also expected to be concise, and avoid immaterial information”.

Moreover, the European legislator requires a disclosure on diversity policy according to which companies shall provide, in relation to administrative, management and supervisory bodies:

- a. The information relating to age, gender, educational and professional backgrounds;

- b. The objectives of that diversity policy and how it has been implemented; and

- c. The results of its implementation in the reporting period.

This requirement is not dependent on any level of significance or materiality.

The Directive does not provide any specific disclosure framework but allows the use of national, European, or international frameworks, even though “details of the framework(s) relied upon should be disclosed”. For international frameworks, it specifically mentions (in paragraph no. 9 of the preamble): the Global Reporting Initiative G.R.I. G4; the UN’s Global Compact; the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; the International Labour Organization’s Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning multinational enterprises and social policy. The purpose of this approach is to create a link between European regulation and international reporting in order to make non-financial disclosure comparable [50]. The final goal is accounting harmonization.

However, critical comments on this last point should also be underlined. Szabo and Sorensen [60] claim that an approach to non-financial reporting based “on minimum harmonization, not supported by detailed rules and standards on the collection and the processing of information, is not likely to have a significant effect”, above all as regards the aim of improving the CSR.

Regarding the structure of information (where), the Directive requires the non-financial statement to be included in the management report. However, this claim is not final because the Directive also makes it possible to use a separate report, but “the report must be published at the same time as the management report or not later than 6 months after the balance sheet date and is referred to in the management report”. In other words, the external reader must understand clearly the path to follow for gaining access to the information. In conclusion, the Directive allows two reporting systems to be maintained (FR and SR), with a reference in the management report to publication of the SR. On this point the Guidelines clarify that this approach is based on the connectivity of information, so there could be different sources of information but they must be inter-related. For example, the NFS “may include internal cross references or signposting in order to be concise, limit repetition, and provide links to other information … but cross referencing and signposting should be smart and user-friendly, for instance, by applying a practical rule of ‘maximum one ‘click’ out of the report’”.

4. Research Method

4.1. The Methodology Applied

The first stage of the research activity was aimed at analyzing different documents and studies in order to find out and better define the information requested by the Directive. In this way, we managed to lay the foundation for the subsequent analysis and identify the theoretical reference framework that firms have to face in these first steps of the accounting harmonization process in the field of non-financial disclosure.

In greater detail, the EU Directive 2014/95 and the specific requirements in terms of disclosure (what) and structure of the information (where) were analyzed initially. Due to the low level of specification of the EU Directive, other studies and international guidelines were examined in depth. Particularly, we considered the GRI G4 Guidelines [61] and the IPIECA/API [62,63]. These guidelines were used in a previous study [10,64] and are also widely used by extractive petroleum companies for drawing up sustainability reports. Furthermore, the EU Legislator also recognizes these guidelines as important references for compliance with the regulation. Finally, previous research on the extractive petroleum companies [65,66,67,68,69,70] was studied in order to better qualify the information on the business model required by the EU Directive (Section 3.2, letter f).

To analyze the contents of the reports (what) we used a disclosure-scoring system [71,72], i.e., an analysis technique that provides for classification of the information in pre-selected categories and sub-categories and subsequent measurement of the related disclosure level. This technique is considered a partial form [73] of content analysis [74,75].

More specifically, the research consisted of the following phases [71,76]:

- analysis of the previous studies and official documents mentioned above, in primis, the EU Directive 2014/95;

- identification, by the research group, of the information categories and sub-categories, in light of the findings of the previous study phase;

- construction of the disclosure-scoring sheet and definition of the rules for identification of the individual variables related to categories and sub-categories;

- application of the investigation technique by two researchers on the same sample of financial reports—with particular reference to the sustainability section and the corporate governance section—and the SR, by highlighting any differences in the findings. In this pre-analysis phase, in order to make the behavior of the researchers as uniform as possible, some modifications had to be made to the basic scheme, and only after achieving 90% identity between the results did we actually direct our efforts to analysis of the study reports;

- analysis of the reports and application of the detailed rules defined in the pre-analysis phase, by attributing the score 0/1 to each variable and considering all equally important in terms of disclosure. The Code Unit for classifying the variables is the sentence. Within the compass of this analysis we, therefore, decided to ascribe the same importance to each piece of information, in order to achieve “non-weighted” medium disclosure indices, unlike the methods adopted by many other authors [77]. This choice, elected also by other academics [78], was made considering that: firstly, the establishment of “weighted” indices would have introduced subjective additional elements in the analysis; besides, at present, there seems to be no generally accepted classification to report the most important information disclosed by the firms; and

- identification of the data and subsequent processing of the results with the creation of a disclosure index and an overlapping index, in order to measure the level of information and the level of overlapping between the financial report and the sustainability report. The disclosure index is calculated for the financial report and for the sustainability report:where:

- is the x variables disclosed in the report by the i company (financial report or sustainability report);

- X is the maximum number of variables (in our case 148); and

- n is the company analyzed;

- N is the number of the companies selected.

where:- is the variables disclosed jointly in the financial report and in the sustainability report by the i company (financial report or sustainability report);

- is the x variables disclosed in the reports by the i company (financial report or sustainability report); and

- n is the company analyzed;

- N is the number of the companies selected.

The information categories are established by the Directive (Table 2): (1) environmental (24 variables); (2) employee (28 variables); (3) social (nine variables); (4) human rights (six variables); (5) anti-corruption and bribery (nine variables); (6) diversity (three variables); and (7) business model (69 variables). Categories from (1) to (5) are subdivided into the following four sub-categories: (a) policy pursued; (b) outcome; (c) risks; and (d) non-financial key performance indicators, whereas category no. (6) is subdivided into the three sub-categories required by the Directive: (a) policy pursued; (b) outcome; and (c) background. The business model has no sub-categories.

Table 2.

The model of disclosure.

The total individual variables used for the analysis of financial reports and sustainability reports [10] amount to a total of 148 (see Appendix A, Table A1 and Table A2 for examples).

Various research on the disclosure indices are based on the general principles of content analysis. With regard to these indices, the most important problem is to evaluate the relations between quantity and quality of the disclosure. Indeed, some authors affirms “although important, assessment of the quality of the information is very difficult” [77]. In this research, we shall not investigate the quality of the disclosure [79] but the level of disclosure [80], by taking into account both the completeness of company information (what) and the structure of information (where), by underlining the overlapping level between the two reports under examination. While the completeness is measured by the presence of the variables in the reports investigated, the overlap is measured by the joint presence of the same information in both FR and SR.

4.2. Research Sample and Documents Analyzed

Oil and gas companies have been selected because of their special attention to the financial and sustainability disclosures.

According to some authors [38]: “Member firms in industries with higher environmental impact would be more scrutinized by the general public. To be responsive to such challenges, they would be more likely to utilize sustainability report as a tool to manage their legitimacy challenges”. Thus, these companies are largely involved in sustainability reporting and, due to the important social and environmental externalities they generate, these companies often draw up sustainability reports, over and in addition to the financial report. Thus, the oil and gas sector will have a great deal of information on sustainability disclosure [37].

Furthermore, the oil and gas companies, since they operate in different geographical areas, are subject to different national disclosure regulations. In fact, this sector has frequently been the subject of analysis by the bodies having powers of accounting regulation [67,81].

It follows that the sector enables us to test ex ante the requirements of the Directive in terms of completeness and overlapping, in order to apply the IA framework in a context that can be regarded as already mature in terms of communication [9].

The choice of only one sector is then linked to the concept of materiality, since the material issues of only one sector should be more homogeneous with respect to those of various different sectors. This is also reflected in the Guidelines that point out “Similar issues are likely to be material to companies operating in the same sector, or sharing supply chains” or “It may therefore be appropriate to directly compare relevant non-financial disclosures among companies in the same sector”.

The exploratory study was conducted on the European extractive petroleum companies listed in the DJSTOXX 600 Europe index from 30 June 2015. The analyzed companies are reported in Table 3. Since there are no indices that encompass all European listed companies, DJSTOXX has been selected to avoid subjectivity in the selection of the sample and to allow the reliability of the results. The use of this index is recognized in the literature [10].

Table 3.

The companies analyzed.

The analysis was performed on the 2014 FR and SR published on the companies’ web sites. The year 2014 was selected because it is consistent with the objectives of the analysis, since it is the year of publication of the Directive (before the national transposition) and according to the IA framework this allows application of an ex ante impact assessment of the Directive. To assure homogeneity, the authors have checked that all the SRs have been drawn up following the same guidelines (GRI G4).

The research in this sector could be replicated for others, using the same methodology and empirical analysis to generalize the conclusion of the present work.

5. Results

The results of the analysis are illustrated in Table 4 where in bold we report the results for categories.

Table 4.

The disclosure indices results.

The analysis highlights a fair degree of completeness (RQ1) of the sustainability report on environmental, social, employee-related topics, safeguarding of human rights, and anti-corruption matters. The diversity is examined in greater depth in the financial report. Finally, the information on the business model is dealt with in greater detail in the financial report, whereas in the sustainability report the business model information serves exclusively as a framework for a better comprehension of the previously mentioned information categories [82]. However, this is a preliminary assessment because there is a remarkable overlap between the two reports (FR and SR), i.e., a great deal information is in both reports. The information overlapping appears limited only for social category and business model. For the other categories, i.e., environmental, employee, human rights, and anti-corruption, the overlapping degree is about 34% on average, as evidence that the topics are dealt with both in the sustainability and in the financial report.

Going into the substance of the information categories, and in order to comment on the results referring to the sub-categories (what and where), we noticed that in the sustainability report the closest attention is paid to the environment and, in particular, to policies (0.83). Less attention is paid to information completeness of the outcomes and the key performance indicators. The risks area, generally dealt with adequately also in the sustainability report (0.50), is addressed more thoroughly in the financial report (0.70). As regards the environment, the results highlight a considerable overlap for the sub-categories: policies, risks, and key performance indicators. The joint reading of the two reports—financial and sustainability—contributes instead to improving the disclosure degree of the outcome.

With regard to the employees, companies tend to make use of the sustainability report to provide information on policies, key performance indicators, and the outcomes, although—as regards the latter—the degree of completeness could be improved. Conversely, less attention is focused on risks. Additionally, in this case, the information completeness on the risks related to the employees is improved by joint reading of the sustainability (0.34) and financial reports (0.52). With reference to the employee category, the overlap is present and widespread in all the sub-categories.

As regards the social matters, the most addressed category is that of the outcome, particularly emphasized in the sustainability report (0.75). Completeness of the remaining information subcategories is very poor (policy pursued), or even absent (risks and non-financial KPI). As regards the outcome in the social category, a high rate of overlapping appears (0.32) and this denotes that companies describe the same information in the SR and in the FR.

The degree of completeness on the policies pursued for the protection of human rights and the non-financial KPI are definitely high in the sustainability report. The remaining sub-categories are neglected. The outcomes are mainly addressed in the financial report, whereas the information on risks, where there is room for improvement, is presented in the sustainability report. As regards human rights, the overlap rate is high in the policy pursued (0.74) and non-financial key performance indicators (0.67) which are, however, the most complete. Conversely, the overlap is limited in the outcome and risks sub-categories, which also show a lower degree of completeness.

With reference to anti-corruption matters, the degree of completeness of the sustainability report is generally high for all the sub-categories, even if the prevailing attention is on the outcomes (0.60). Risks and policies are, anyway, treated in-depth. The key performance indicators are more thoroughly disclosed in the SR. As regards anti-corruption matters, the presence of a high level of overlap in the risks (0.51) and non-financial KPI (0.50) subcategories suggests the need to come up with a more effective organization of the information for the external users.

As to the diversity, the degree of completeness of all the sub-categories is higher in the FR. The information that can be found exclusively in the financial report as regards the background and in the sustainability report disclosure pertain also to the outcomes and policies. Anyway, for these last two categories there is a high level of overlap (0.67 and 0.40), which emphasizes that joint reading of the two reports results in a limited increase in the level of information completeness.

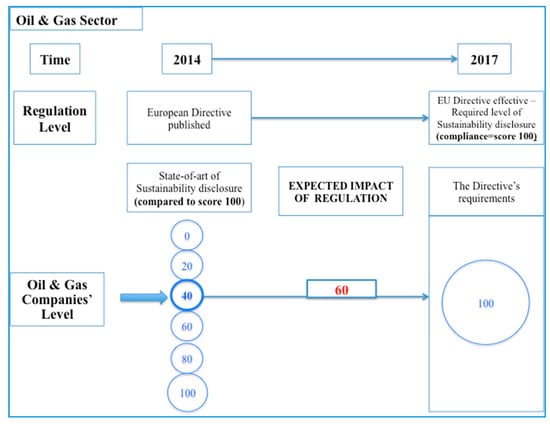

Regarding the RQ1, the results reveal that oil and gas companies disclose a fair amount of sustainability information (total average of 0.39 in FR and 0.41 in SR) compared to the Directive requirements. However, this means that companies will have to increase sustainability disclosure to reach the Directive goal (i.e., 1) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expected impact of regulation in the oil and gas sector.

Answering RQ2, the results suggest that oil and gas companies will have to invest more in disclosing environmental and employee matters, and also in the business model’s communication (these are the only three categories with less than 0.50 in both reports). Moreover, the level of overlap has to be reduced to achieve the easy and clear readability of reports required by the Directive.

6. Conclusions

According to the IA framework, the paper analyzed the disclosure degree of the sustainability and financial reports (referring to the EU Directive requirements). The study was conducted in the oil and gas sector, which is considered evolved in terms of disclosure. The analysis model has been developed on the basis of the Framework GRI G4 and, as regards the business model, on the basis of the studies and specific research for the sector under examination.

To answer RQ1, two elements are studied: firstly, we examined the content (what) both of the sustainability and the financial report, with reference to the information required by the Directive; secondly, we examined the structure of information (where), that is to say, the information overlapping between the two reports. The research model allows us to analyze the information gaps, if any, and whether the European Directive will achieve its policy objective (i.e., improve sustainability disclosure).

Based on the disclosure scoring system, the results confirm the fair degree of completeness of the environmental, social, employee-related, human rights, and anti-corruption information provided by the sustainability report. Nevertheless, the results have shown that there is some information, even in a particularly information-sensitive sector on sustainability, such as oil and gas, that is still poorly disclosed (RQ2): the outcomes concerning environmental matters (one of the “material” topics of the sector under examination) and employee-related matters, the risks related to social and human rights matters and the KPI on anti-corruption and bribery, whereas diversity and the business model are disclosed in the FR. Currently, that is to say before the Directive came into force, fairly complete information on sustainability was, therefore, achieved only by combined reading of the two documents, the financial and the sustainability report. This result is not consistent with the findings of the Polish study [43] where “Polish-listed companies use at least one channel to communicate CSR activity, with greater importance placed on annual reports (and the Internet) as disclosure media compared to CSR reports”.

The different behaviors among companies were also observed. Certainly, with reference to the sustainability report, companies tend to be more homogeneous in terms of communication (thanks to the adoption of the same International Standard GRI G4), whereas the heterogeneity is more evident with reference to the financial report. The social and diversity subject areas continue to be characterized by extremely different communication choices among companies.

Finally, the results underline the presence of information overlapping—sometimes very pronounced—between the two reports.

According to the IA framework, the quality of the Directive is good because its obligation will also increase the sustainability disclosure (one of its policy objectives) in an advanced sector such as oil and gas. The results have also shown that these companies will have to invest in their sustainability reporting system to comply with the law (Figure 2). This conclusion is consistent with two previous studies: one concerned the Italian-listed companies [42], and the other one, the Polish-listed companies [43], even if these analyses focused on one country and not on one sector, as in our research. The average level of compliance of our sample is 40%, low compared to the score of the Italian companies (49%) [42], higher compared to that of Polish companies (36%) [43].

The same consideration could also be made for other sectors: if one of the most advanced has to struggle on this theme, for the others it will be a new challenge.

The Directive is flexible on the information overlap as a regulatory policy choice (ref. Section 3.2). However, the authors’ opinion is that this is a starting point and the regulation could be more specific on “where” to publish this information in order to achieve a European comparability on sustainability disclosure and reduce the amount of the same information replicated in different documents. This is because different reporting scenarios can be found, e.g., a company with two reports (FR and SR), a company with an embedded one, and maybe from 2017 company with FR plus a non-financial statement (according to the Directive), and a SR.

In fact, on the one hand, the Directive requires a plurality of information on sustainability, thus eliciting a reflection on the completeness and thoroughness of the published reports. In the sector we examined, the Directive could decrease the standard deviation for the human rights and diversity areas. On the other hand, the Directive requires sustainability disclosure to be either directly provided in the financial report or in a separate, well-structured document.

The results of the research undoubtedly suffer from some limitations. The analysis is an exploratory study conducted on only one sector and the reduced number of observations does not allow any generalization of the conclusions. However, the model proposed in the research could be replicated in other areas. Future research is needed. In fact, the regulation of accounting develops both in the ex ante phase and in the ex-post phase [5,7]. This paper focuses on the ex-ante phase, aimed at understanding the quality of the new regulation. The analysis model suggested in the study can, therefore, be used also in the ex post assessment phase, i.e., in the time following introduction of the new regulation. Application of the model developed in the reports over the years following entry into force of the Directive will be required in order to obtain a useful benchmark to assess the real effect of the accounting regulation.

Secondly, it will be useful to replicate the research method used in the study for sectors other than oil and gas, which is generally considered among the most evolved in terms of communication.

Thirdly, the suggested analysis model can be used for national comparative analysis. In fact, the Directive has been transposed into the regulation of the various European countries, thus giving rise to different choices and solutions.

Another application of the present model could be to companies that are not subject to the Directive but have an important impact on society, for example listed firms with less than 500 employees or private firms in certain sectors (i.e., steel sector), because it could lead to an analysis of whether the cost of adapting to normative pressure could be more than the benefit derived from it.

Lastly, it will be interesting to understand whether companies will decide to adopt the non-financial statement as a document by itself, in addition to the documents already produced, or if they will prefer to integrate the information in only one document and the reasons for their choices, in order to further understand the outcomes resulting from the approach to “sustainability regulation”.

Author Contributions

Cristian Carini and Laura Rocca studied and wrote the theoretical framework; Laura Rocca wrote the literature review and the Section on the sustainability regulation in Europe; Monica Veneziani designed and wrote the research method; Cristian Carini and Claudio Teodori collected data and analyzed the findings; all the authors developed and wrote the introduction and conclusions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Variables analyzed.

Table A1.

Variables analyzed.

| Categories | Subcategories | No. | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental | |||

| Policy pursued | 3 | Initiatives to use renewable energy sources and to increase energy efficiency. | |

| Objectives, programmes, and targets for protecting and restoring native ecosystems and species in degraded areas. | |||

| Initiatives aimed at reduction of emissions | |||

| Outcome | 5 | Environmental investments and expenditure | |

| Description of the major impacts on biodiversity associated with activities and/or products and services in terrestrial, freshwater, and marine environments. | |||

| Changes to natural habitats resulting from activities and operations and percentage of habitat protected or restored. | |||

| Total amount of waste by type and destination | |||

| Water sources and related ecosystems/habitats significantly affected by discharges of water and runoff. | |||

| Risks | 4 | Type of risk: environmental risks | |

| Time horizon/degree of probability/entity of impact: environmental risks | |||

| Ways of dealing with environmental risks | |||

| Adoption of protocols or adherence to conventions on the environment | |||

| Non-financial KPI | 12 | Total materials use other than water, by type. | |

| Percentage of materials used that are wastes (processed or unprocessed) from sources external to the reporting organisation | |||

| Direct and indirect energy use segmented by primary source. | |||

| Total water use. | |||

| Water sources and related ecosystems/habitats significantly affected by the use of water. | |||

| Total recycling and reuse of water. | |||

| Total amount of land owned, leased, or managed for production activities or extractive use. | |||

| Location and size of land owned, leased, or managed in biodiversity-rich habitats. | |||

| Emissions of greenhouse gas (direct and indirect), of ozone-depleting substances, of NOx, SOx, and other significant air emissions by type. | |||

| Recycled waste | |||

| Significant spills of chemicals, oils, and fuels in terms of total number and total volume. | |||

| Accidents and fines for environmental damage | |||

| Total Environmental variables | 24 | ||

| Employee | |||

| Policy pursued | 10 | Description of human resources management policy | |

| Recruitment policies | |||

| Training policies (hours, interventions per project, etc.) | |||

| Local Employment opportunities | |||

| Descriptions of incentive policies | |||

| Initiatives for monitoring employee satisfaction | |||

| Initiatives for improving the work environment | |||

| Description of policies or programmes for health and safety at work | |||

| Involvement in the decision-making process | |||

| Restructuring plans (sale of business units, outsourcing) involving personnel mobility | |||

| Outcome | 6 | Information on employees | |

| Employment type (full time/part time), contract (indefinite or permanent/fixed term or temporary). | |||

| Employee benefits beyond those legally mandated. | |||

| Compliance with human resources management standards (SA8000, ILO) | |||

| Performance bonuses | |||

| Presence of trade union representatives | |||

| Risks | 5 | Type of risk: safety at work risks | |

| Time horizon/degree of probability/entity of impact: safety at work risks | |||

| Ways of dealing with safety at work risks | |||

| Disputes and complaints with/of employees | |||

| Compliance with voluntary codes, social responsibility bonuses awarded to the company | |||

| Non-financial KPI | 7 | New recruitments/dismissals | |

| Absenteeism | |||

| Hours on strike | |||

| Employee turnover | |||

| Number of accidents/injuries | |||

| Illness Rates | |||

| % women employed | |||

| Total Employee variables | 28 | ||

| Social | |||

| Policy pursued | 1 | Information on future objectives in relations with the stakeholders | |

| Outcome | 6 | General information on relations with the stakeholders | |

| Involvement of the stakeholders | |||

| Investments in the social field | |||

| Support and/or financing of no-profit or humanitarian organizations | |||

| Social/cultural development interventions and initiatives | |||

| Donations to the community, civil society, and other groups | |||

| Risks | 1 | Social risks: operations that could negatively impact on society (local community) | |

| Non-financial KPI | 1 | Percentage or number of operations with local communities | |

| Total Social Variables | 9 | ||

| Human rights | |||

| Policy pursued | 2 | Global policies and procedures for preventing all forms of discrimination in the organization's business activities | |

| Description of policies and programmes to ensure respect for human rights in the company's business activities | |||

| Outcome | 1 | Actions and programmes for aid to minorities and underprivileged categories | |

| Risks | 2 | Any disputes in progress for discrimination | |

| Verification of compliance with laws on child and forced labour | |||

| Non-financial KPI | 1 | Hours of training on human rights policies and procedures | |

| Total Human Rights Variables | 6 | ||

| Anti-corruption and bribery | |||

| Policy pursued | 2 | Description of policies, procedures and control systems for the company and the workers concerning corruption | |

| Description of policies, procedures and control systems for management of political pressures and contributions to political parties | |||

| Outcome | 1 | Transparency of payments to governments | |

| Risks | 5 | Management systems implemented | |

| Objectives of management systems | |||

| Status of certifications obtained (ISO 140001, etc.) | |||

| Existence of revisions for certifications | |||

| Involvement of suppliers and contractors in the management systems | |||

| Non-financial KPI | 1 | Number or percentage of verification operations on anticorruption policies | |

| Total Anti-corruption and bribery Variables | 9 | ||

| Diversity | |||

| Policy pursued | 1 | Diversity: policy | |

| Outcome | 1 | Organizational chart and structure | |

| Background | 1 | Indication of CV of board members and principal managers | |

| Total Diversity Variables | 3 | ||

| Business Model | |||

| Summary of company history | |||

| Countries of operations | |||

| Expression of company identity | |||

| Expression of mission and strategic plan | |||

| Company vision and values | |||

| Profile of year | |||

| Comparison with main competitors | |||

| Relations with main competitors | |||

| Collaboration agreements | |||

| Indication of main drivers of company efficiency | |||

| Initiatives concerning acquisition of oilfelds | |||

| Initiatives concerning disposal of oilfields | |||

| Initiatives concerning acquisition of exploration rights | |||

| Recovery initiatives | |||

| Initiatives for development of existing oilfields | |||

| Exploration initiatives with positive outcome | |||

| Exploration initiatives with negative outcome | |||

| Discovery of new oilfields | |||

| Description of extraction activity | |||

| Description of reserve revision | |||

| Description of Product Sharing Agreement | |||

| Availability of transport channels for extracted resources | |||

| Description of overall strategy | |||

| Volumes/revenues/market share objectives | |||

| Margins/profit results/profitability/value creation objectives | |||

| Strategic collaboration agreements | |||

| Planned exploration initiatives | |||

| Costs of exploration initiatives | |||

| Initiatives concerning acquisition of exploration rights | |||

| Costs of initiatives concerning acquisition of exploration rights | |||

| Drilling programmes of major oilfields | |||

| Costs of drilling programmes of major oilfields | |||

| Initiatives for development of oilfields | |||

| Costs of development initiatives | |||

| Initiatives for recovery of additional crude oil | |||

| Costs of recovery initiatives | |||

| Programmes for acquisition of new oilfields | |||

| Costs of acquisition initiatives | |||

| Programmes for disposal of oilfields | |||

| Expected proceeds from disposals | |||

| Estimated growth of reserves | |||

| Extraction programmes budgeted | |||

| Description of timeline of most important projects | |||

| Presentation of projects and previous objectives achieved | |||

| Presentation of projects and previous objectives not achieved | |||

| Presentation of projects and previous objectives deferred | |||

| General description of risk management policy | |||

| General description of risk management structure | |||

| Type of risk: operating risks | |||

| Time horizon/degree of probability/entity of impact: operating risks | |||

| Ways of dealing with operating risks | |||

| Type of risk: risks from contractual disputes | |||

| Time horizon/degree of probability/entity of impact - Risks from contractual disputes | |||

| Ways of dealing with risks from contractual disputes | |||

| Extraction wells (number) | |||

| Development wells (number) | |||

| Success rate of exploration initiatives | |||

| Reserve replacement rate | |||

| Extraction rate | |||

| Extraction rate due to new oilfields | |||

| Productivity of major oilfields | |||

| Reserve life | |||

| Reserve replacement cost | |||

| Existence of company culture geared to technological innovation | |||

| Description of policies for investment in technology | |||

| Description of technologies used in the company | |||

| Details of technologies and patents launched by the company over the last few years | |||

| Technological partnership relations | |||

| Objectives and main benefits of technological projects | |||

| Total Business Model Variables | 69 | ||

Table A2.

Examples of categorization.

Table A2.

Examples of categorization.

| Examples from Reports | Category | Sub-Category |

|---|---|---|

| Our annual engagement survey, “Engage xxx”, gives employees the opportunity to provide feedback on their experience of working for xxx. | Employee | Policy pursued |

| We report GHG emissions from all xxx’s consolidated entities, as well as our share of equity-accounted entities other than xxx’s share of xxx. Our direct GHG emissions were 48.9 million tonnes (Mte) in 2015 (2014 48.6 Mte, 2013 50.3 Mte). | Environmental | Non-financial KPI |

| In 2014, all of the material investment agreements and contracts were analyzed from a human rights perspective. | Human Rights | Outcome |

References

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Sustainability in Impact Assessments. A Review of Impact Assessment Systems in Selected OECD Countries and the European Commission; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Impact Assessment Guidelines. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/smart-regulation/impact/key_docs/key_docs_en.htm (accessed on 19 June 2017).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Framework for Regulatory Policy Evaluation; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coglianese, C. Measuring Regulatory Performance, Evaluating the Impact of Regulation and Regulatory Policy, Expert Paper n. 1; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, D.; Kirkpatrick, C. Measuring Regulatory Performance, The Economic Impact of Regulatory Policy: A Literature Review of Quantitative Evidence, Expert Paper n. 3; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli, C.; Oliver, F. Measuring Regulatory Performance, Evaluating Regulatory Management Tools and Programmes, Expert Paper n. 2; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Radaelli, C. Diffusion without convergence: How political context shapes the adoption of regulatory impact assessment. J. Eur. Public Policy 2005, 12, 924–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilling, P.F.A. Reporting on Long Term Value Creation. The Example of Public Canadian Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carini, C.; Chiaf, E. The relationship between annual and sustainability, environmental and social reports. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2015, 13, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepankiewicz, E.I.; Mucko, P. CSR Reporting Practices of Polish Energy and Mining Companies. Sustainability 2016, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. Indicators of Regulatory Management Systems; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R. Regulatory Impact Assessment. Manag. Focus 2006, 24, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. The Economic Appraisal of Environmental Projects and Policies: A Practical Guide; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marchand, J.S.; Brunet, M. The emergence of post-NPM initiatives: Integrated Impact Assessment as a hybrid decision-making tool. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achtnich, M.; Rennings, K.; Hertin, J. Experiences with Integrated Impact Assessment—Empirical Evidence from a Survey in Three European Member States. Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radaelli, C. The diffusion of regulatory impact analysis—Best practice or lesson-drawing? Eur. J. Polit. Res. 2014, 43, 723–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.; Turley, S. The Regulation of Accounting; Basil Blacwell: Oxford, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Keyworth, T.; Yarrow, G. Revising the Regulatory Impact Assessment: Response to BRE’s Consultation; Regulatory Policy Institute: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Allio, L. Keeping the Centre of Gravity Work: Impact Assessment Scientific Advice and Regulatory Reform. Eur. J. Risk Reg. 2010, 1, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Montecchia, A.; Giordano, F.; Grieco, C. Communicating CSR: Integrated approach or Selfie? Evidence from the Milan Stock Exchange. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 136, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R. Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for Sustainability … and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet. Account. Organ. Soc. 2010, 35, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Corporate sustainability reporting: A study in disingenuity? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaltegger, S.; Burritt, R.L. Sustainability accounting for companies: Catchphrase or decision support for business leaders? J. World Bus. 2010, 45, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Dwyer, B. Stakeholder democracy: Challenges and contributions from social accounting. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2005, 14, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.; Schaltegger, S. Pragmatism and new directions in social and environmental accountability research. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 263–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamerschlag, R.; Möller, K.; Verbeeten, F. Determinants of voluntary CSR disclosure: Empirical evidence from Germany. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2010, 5, 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roca, L.C.; Searcy, C. An analysis of indicators disclosed in corporate sustainability reports. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 20, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, O.S.; Towler, A.B. A comparative study of the contents of corporate social responsibility reports of UK companies. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2004, 15, 420–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rämö, H. Visualizing the Phronetic Organization: The Case of Photographs in CSR Reports. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiral, O. Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2013, 26, 1036–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvey, J.N.; Giordano-Spring, S.; Cho, C.H.; Putten, D.M. The Normativity and Legitimacy of CSR Disclosure: Evidence from France. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.H.; Michelon, G.; Patten, D.M.; Roberts, R.W. CSR disclosure: The more things change … ? Account. Audit. Account. J. 2015, 28, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habek, P.; Wolniak, R.; Quant, Q. Assessing the quality of corporate social responsibility reports: The case of reporting practices in selected European Union member states. Qual. Quant. 2016, 50, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, S.P.; Martell, T.F.; Demir, M.J. An evaluation of the quality of corporate social responsibility reports by some of the world’s largest financial institutions. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 787–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughey, C.; Sulkowski, A.J. More Disclosure = Better CSR Reputation? An Examination of CSR Reputation Leaders and Laggards in the Global Oil & Gas Industry. J. Acad. Bus. Econ. 2012, 12, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- Shabana, K.M.; Buchholtz, A.K.; Carroll, A.B. The Institutionalization of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 1107–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.; Powell, W. The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. Am. Soc. Rev. 1983, 48, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research Review Article. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulkowski, A.J.; Waddock, S. Beyond Sustainability Reporting: Integrated Reporting Is Practiced, Required & More Would Be Better. UST Law Rev. 2014, 10, 1060–1123. [Google Scholar]

- Venturelli, A.; Caputo, F.; Cosma, S.; Leopizzi, R.; Pizzi, S. Directive 2014/95/EU: Are Italian Companies Already Compliant? Sustainability 2017, 9, 1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak, L.; Rózanska, E. CSR Disclosure in Polish-Listed Companies in the Light of Directive 2014/95/EU Requirements: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Kouhy, R.; Lavers, S. Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1995, 8, 47–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, F.A.; Amran, A.; Zainuddin, Y. Sustainability disclosure in annual reports and websites: A study of the banking industry in Bangladesh. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 23, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incollingo, A.; Bianchi, M. The Connectivity of Information in Integrated Reporting. Empirical Evidence from International Context. Financ. Rep. 2016, 2, 55–78. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, D.M. Lessons from the Third Wave: A reflection on the rediscovery of Corporate Social Responsibility by the mainstream accounting research community. Financ. Rep. 2013, 2, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, P.L.; Tibiletti, V. Bilancio Sociale e Valori di Impresa; Edizioni Monte Università Parma: Parma, Italy, 2004; ISBN 978878470929. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.; Hur, W.M.; Yeo, J. Corporate Brand Trust as a Mediator in the Relationship between Consumer Perception of CSR, Corporate Hypocrisy, and Corporate Reputation. Sustainability 2015, 7, 3683–3694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Green Paper on “Promoting a European Framework for Corporate Social Responsibility”; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 Amending Directive 2013/34/EU as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Undertakings and Groups. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32014L0095 (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- Federation of European Accountants. EU Directive on Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information. Achieving Good Quality and Consistent Reporting, Position Paper. 2016. Available online: https://www.accountancyeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/FEE_position_paper_EU_NFI_Directive_final.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2017).

- Federation of European Accountants. Sustainability Information in Annual Reports—Building on Implementation of the Modernisation Directive, Discussion Paper. 2008. Available online: https://www.accountancyeurope.eu/publications/discussion-paper-sustainability-information-in-annual-reports-building-on-implementation-of-the-modernisation-directive (accessed on 10 February 2017).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Council Directives 78/660/EEC and 83/349/EEC as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Companies and Groups, 2013. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A52013PC0207 (accessed on 24 May 2015).

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document, Impact Assessment, Accompanying the Document “Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council Amending Council Directives 78/660/EEC and 83/349/EEC as Regards Disclosure of Non-Financial and Diversity Information by Certain Large Companies and Groups”. 2013. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52013SC0127 (accessed on 26 June 2017).

- European Commission. Directorate General for the Internal Market and Services. Summary Report of the Responses Received to the Public Consultation on Disclosure of Non-Financial Information by Companies. April 2011. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/finance/consultations/2010/non-financial-reporting/docs/summary_report_en.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- European Commission. Directorate General for the Internal Market and Services. Final Report of Disclosure of Non-Financial Information by Companies, Centre for Strategy & Evaluation Services. December 2011. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/accounting/docs/non-financial-reporting/com_2013_207-study_en.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibilities of the Businessman; Harper: NewYork, NY, USA, 1953; ISBN 978-1-60938-196-7. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission. Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting—Methodology for Reporting Non-Financial Information. Draft, 2017. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/170626-non-financial-reporting-guidelines_en (accessed on 15 June 2017).

- Szabó, D.G.; Sorensen, K.E. New EU Directive on the Disclosure of Non-Financial Information (CSR). Eur. Co. Financ. Law Rev. 2015, 12, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Reporting Initiative. G4 Sustainability Report Guidelines. May 2013. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/g4/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association. Report No. 437. Oil and Gas Industry Guidance on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting, 2nd ed.; IPIECA: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative. G4 Sector Disclosure Oil and Gas. May 2013. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/information/g4/sector-guidance/sector-guidance/oil-and-gas/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Brammer, S.; Pavelin, S. Voluntary Environmental Disclosure by Large UK Companies. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 2006, 37, 133–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PricewaterhouseCoopers. Drilling Deeper. Managing Value and Reporting in the Petroleum Industry. Available online: https://www.csun.edu/~hfact004/352/1petroleumaccounting.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2016).

- Quagli, A.; Teodori, C. L’informativa Volontaria per Settori di Attività; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2005; ISBN 88-464-6938-0. [Google Scholar]

- Security and Exchange Commission. Regulation S-X, Rule 4-10 Financial Accounting and Reporting for Oil and Gas Producing Activities Pursuant to the Federal Securities Laws and the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975. 2005. Available online: https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2008/33-8995.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2015).

- Canadian Security Administrators. National Instrument 51–101 Standards of Disclosure for Oil and Gas Activities. 2006. Available online: http://www.osc.gov.on.ca/en/13338.htm (accessed on 10 February 2015).

- Carini, C. Il Business Report di Settore. Ruolo Informativo e Principi di Predisposizione; Giappichelli: Torino, Italy, 2009; ISBN 9788834897355. [Google Scholar]

- World Intellectual Capital Initiative. Oil and Gas Sector WIKI KPIs. 2016. Available online: http://www.wici-global.com/kpis (accessed on 22 June 2017).

- Robb, S.W.G.; Single, L.E.; Zarzeski, A. Nonfinancial Disclosure Across Anglo-American Countries. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2001, 17, 30–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanstraelen, A.; Zarzeski, M.T.; Robb, S.W.G. Corporate Nonfinancial Disclosure Practices and Financial Analysis Forecast Ability Across Three European Countries. J. Int. Financ. Manag. Account. 2003, 14, 249–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, V.; McInnes, B.; Fearnley, S. A Methodology for Analysing and Evaluating Narratives in Annual Reports: A Comprehensive Descriptive Profile and Metrics for Disclosure Quality Attributes. Account. Forum 2004, 28, 205–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content Analysis in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krippendorff, K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9781412983150. [Google Scholar]

- Bendotti, G.; Carini, C.; Teodori, C.; Veneziani, M. Content and quality of information: Analysis of the management discussion session in the Italian financial reports in the period 2003-2008. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2013, 10, 248–264. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C.A. Disclosure Level and the Cost of Equity Capital. Account. Rev. 1997, 72, 323–349. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, T.E. Disclosure in the Corporate Annual Reports of Swedish Companies. Account. Bus. Res. 1989, 19, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.W.; Verrecchia, R.E. Disclosure, liquidity and the cost of capital. J. Financ. 1991, 66, 1325–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, C.L.; Shrives, O.J. The use of disclosure indices in accounting research: A review article. Br. Account. Rev. 1991, 23, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]