Abstract

Objective: The objective of this study is to identify, examine, and map the literature on infection prevention and control (IPAC) education and training for visitors to long-term care (LTC) homes. Introduction: Visitor restrictions during infectious outbreaks in LTC homes aim to reduce virus transmission to vulnerable residents. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the negative impacts of such restrictions, prompting the need for IPAC education for visitors. Inclusion Criteria: This review includes research, narrative papers, and grey literature on IPAC education and training for LTC visitors. It focuses on intentional education aimed at preventing infection transmission. Studies not involving visitors or offered in other settings were excluded. Methods: Following the JBI methodology for scoping reviews, bibliographic databases (CINAHL, Embase, AgeLine, Medline, and ERIC) were searched from 1990 to present in English or French. Data were extracted by two reviewers, focusing on the educational content, delivery mode, frequency, timing, and qualifications of educators. A narrative summary and descriptive statistics were produced. Results: The 26 included documents contained guidelines, policies, educational resources, and opinion papers. Pre-2020, healthcare workers were responsible for educating visitors. Post-2020, more detailed recommendations emerged on the frequency, content, and delivery methods. Key topics included hand hygiene (92.3%), respiratory hygiene (80.8%), and PPE use (73.1%). Conclusions: IPAC education and training for LTC visitors is essential for safe visitation. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these educational interventions.

1. Introduction

Infection prevention and control (IPAC) education and training are essential for protecting residents in long-term care (LTC) homes. LTC homes house aging, frail individuals with chronic health conditions, making them particularly vulnerable to infections [1], compounded by organizational challenges, such as a limited living space and high staff turnover, further complicating IPAC efforts. Historically, visitor restrictions have been seen as critical during infectious outbreaks to protect residents [2,3,4,5]. This practice, dating back to the 1800s, stemmed from the belief that visitors are a vehicle for infections [2,6]. While visitor restrictions have been effective in reducing the risk of infection, they are associated with negative psychological impacts, such as social isolation and depression [7]. These concerns became especially pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, intensifying the debate around visitor bans [8].

During the pandemic, global visitor restrictions imposed in LTC homes negatively impacted residents and families, leading to significant efforts to balance infection control, safety, and quality of life [9]. For instance, research since the pandemic onset has highlighted the severe negative effects of visitor bans, including increased depression, agitation, and cognitive decline among residents [10,11] and family members [10,11,12]. These findings emphasize the importance of adopting a balanced approach that takes both infection control and residents’ quality of life into account.

The devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on LTC globally have led to increased efforts to introduce safer visitation strategies [12]. However, the pandemic response highlighted inconsistent regional policies due to a lack of coordination, with homes often working in isolation and struggling to share information effectively [13]. This fragmentation has made it clear that ensuring safety during times of heightened infection risks requires robust IPAC practices. Research has shown improper hand hygiene is a major contributor to the spread of infections, and LTC visitors have been identified as potential carriers of undetected infections, such as tuberculosis and influenza [14,15].

To mitigate these risks, IPAC education and training for visitors is critical. A Canadian study, for example, found notable gaps in visitors’ ability to follow hand hygiene and personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols [16]. While existing research suggests that repetitive, multi-modal education improves IPAC compliance in LTC healthcare workers [17], little is known about how visitors to LTC are educated and trained for IPAC. This scoping review aims to fill this gap by systematically exploring and mapping the various approaches to IPAC education and training for visitors in LTC homes, with a focus on understanding commonly used methods, content, and delivery strategies.

The relevance of this work to nursing is significant, as nurses are integral to the coordination and delivery of IPAC protocols in LTC settings, ensuring staff and visitors adhere to safety measures. This research directly informs nursing practice by mapping visitor IPAC education and training in LTC, which often falls under the responsibility of nursing staff and is a crucial component in safeguarding vulnerable populations. By addressing visitor IPAC education and training, this paper offers valuable insights that can inform future research, policy development, and practical interventions in LTC settings. It contributes to the literature by focusing on the visitor education aspect, an area that has received limited attention in comparison to staff-focused IPAC education and training. In doing so, the paper helps to bridge an important gap in our understanding of how best to manage infection risks in LTC homes while maintaining a safe and supportive environment for both residents and their families.

Research Questions

The overarching review question is as follows: What IPAC education and training have been recommended and/or implemented for visitors in long-term care homes? The five review sub-questions are as follows:

- What IPAC education and training policies and guidelines exist related to visitation in LTC?

- How is education and training related to IPAC delivered to visitors of LTC residents, including frequency, timing, and mode of delivery?

- What content is included in the IPAC education and training provided to visitors of LTC residents?

- What qualifications are required by staff who provide education and training to visitors of LTC residents?

- How has the education and training provided to visitors evolved over time (i.e., pre-pandemic, and throughout the pandemic)?

2. Review Criteria

2.1. Participants

This review included IPAC education and training activities and practices for visitors to LTC homes. Visitors to LTC are not a homogenous group—their IPAC education needs and visiting patterns vary, impacting the educational resources, content, and modes of delivery needed. Visitors included unpaid caregivers, essential caregivers, volunteers, care partners, family members, and/or friends who entered LTC for the sole purpose of visiting a resident. Any education and training that involved staff but also included visitors was considered. There were no limitations imposed on the age, gender, or ethnicity of a visitor to LTC.

2.2. Concept

The concepts examined in this scoping review included all planned and intentional education and training activities, practices, and/or guidelines used for IPAC with visitors in LTC homes. Education included intentional activities, such as demonstrations, to change knowledge, attitudes, or awareness of IPAC practice in LTC. Training included intentional activities to learn IPAC skills or behavior. Education and/or training included but were not limited to in-person, independent, virtual, individual, or group activities. There were no limits regarding the frequency, duration, setting, or provider of the education and training. Any IPAC education and training provided exclusively to staff was excluded.

2.3. Context

LTC homes include any setting, such as a nursing home, residential aged care facility, or skilled-nursing homes, that provide health and social services and residential accommodation to people who cannot care for themselves at home. Other settings, such as home or hospital, were not considered as they are outside the scope of this review focused on LTC facilities.

2.4. Types of Sources

All variations of mixed-methods, quantitative, and qualitative study designs were considered for inclusion in this scoping review. Any text, policy, opinion, and guidelines meeting the inclusion criteria were considered.

3. Methods

This review is registered with Open Science Framework: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/NMXUB (accessed on 31 May 2024). This review adhered to the PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines [18] (Supplementary Material Table S2), followed an a priori protocol [19], and utilized the JBI scoping review methodology [20] including five phases: (i) identifying the research questions; (ii) searching for evidence; (iii) selecting documents; (iv) extracting data; and (v) reporting findings.

3.1. Search Strategy

The search aimed to identify both published and unpublished literature. A JBI-trained librarian (RW) developed the search strategy, which was reviewed by the team. The strategy was adjusted for each database (CINAHL, ERIC, AgeLine, and MEDLINE) (Appendix A) to ensure comprehensive results while avoiding irrelevant sources. Education-related terms were initially tested but excluded to broaden the search. Results were limited to French and English language as those are the languages spoken by the research team members. Results were limited from 1990, reflecting the earliest published IPAC guidelines [21] to early 2023, reflecting the early post-COVID period. Reference lists of selected studies were also reviewed for additional.

3.2. Information Sources

The databases searched included CINAHL, Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, and AgeLine as these are large health-, nursing-, and aging-related databases (see Appendix A). Unpublished studies were sought through Google, which identified 89 relevant aging-related websites (Appendix B). Search terms from the database search strategies were used across websites by RM.

3.3. Study Selection

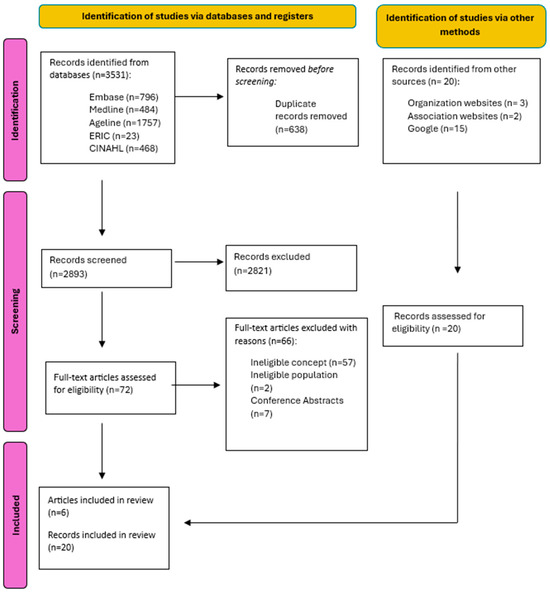

All records were managed in Covidence (Ventas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) systematic review software. As a pilot test of the screening, the authors screened 50 records together and independently screened 200 abstracts (approximately 5% of identified records) to ensure consistency among reviewers (RM, PD, RMM, LKB, CG, and NT). Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers with any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. Next, the full texts of each included document were screened by two independent reviewers. Disagreements between reviewers at this stage were resolved by a third reviewer by reading the full text of the document to decide if it should be included. Excluded studies are listed in the Supplementary Material and a PRISMA flow diagram [22] (Figure 1) was created to visualize the search and screening process.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Note: Adapted from Page et al. [22].

3.4. Data Extraction

A pilot of the data extraction tool (Supplementary Material Table S1) was conducted to ensure consistency. Two reviewers independently extracted data, including content, frequency, and delivery methods, and discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Data from grey literature were extracted into an Excel spreadsheet by RM and PD.

3.5. Data Analysis and Presentation

Extracted data were summarized narratively and presented in tables and graphs. The tables display details of included documents, and graphs highlight trends in the findings related to the research questions supported by narrative summaries.

4. Results

4.1. Study Inclusion

From a total of 3531 identified records, 638 duplicates were removed, 2824 records were excluded through the screening process, and 66 records were excluded after a full-text review. An additional 20 documents were identified through grey literature searches, bringing the total to 26 included documents.

4.2. Characteristics of Included Documents

A summary of the characteristics of the included documents is in Appendix C. Most included documents were IPAC guidelines (50%) [3,4,5,8,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31], educational resources (15.4%) [32,33,34,35], and policies (11.5%) [36,37,38]. Most documents originated from Canada (53.9%) [1,3,4,5,25,26,27,28,34,37,38,39,40,41], the USA (26.9%) [8,25,30,31,33,37,42], and Australia (7.7%) [23,35]. Eight documents (30.8%) were developed pre-COVID-19 [3,4,5,24,25,26,36,39], and eighteen (69.2%) were developed after the onset of COVID-19 [1,8,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,43]. The intended audience for most documents was healthcare workers (50%) [3,4,5,8,23,24,26,30,31,34,36,38,39], visitors (23.1%) [31,32,33,34,35,38], and healthcare/LTC organizations (23.1%) [25,27,28,29,37,41].

4.3. Review Findings

The main review question was as follows: what IPAC education and training have been recommended and/or implemented for visitors in long-term care homes? To address this, the findings are presented according to each sub-question. Detailed descriptions of the findings can be found in the Supplementary Material.

4.3.1. Sub-Question 1: What IPAC Education and Training Policies and Guidelines Exist Related to Visitation in LTC?

As depicted in Appendix C, thirteen documents (50%) were IPAC guidelines for specific infectious diseases, including COVID-19 [23,28,30,31], influenza [4], Clostridioides difficile (c. diff) [3], and healthcare-associated infections [5]. Six documents (23.1%) were general and/or implementation guidelines for IPAC in healthcare facilities, including LTC homes [8,24,25,26,27,29]. Three policy documents (11.5%) addressed preparing for infectious disease outbreaks and visitation [36,37,38]. None of the documents provided a comprehensive overview of IPAC education and training provided to visitors in LTC, including covering all aspects of IPAC training (i.e., provider, frequency, timing, delivery mode, and content).

4.3.2. Sub-Question 2: How Is Education and Training Related to IPAC Delivered to Visitors of LTC Residents, Including Frequency, Timing, and Mode of Delivery?

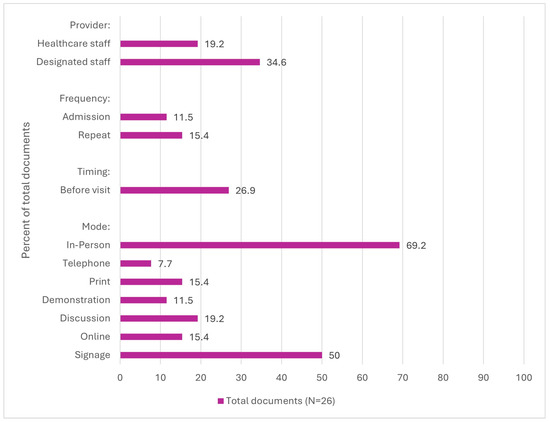

Frequency of Delivery. As displayed in Figure 2, six documents (23.1%) described the frequency of IPAC education for LTC visitors [8,27,28,31,38,41]. Recommendations included providing education during resident admission and when precautions are implemented [8,28,41], repeating the education [27,31,38,41], and having visitors complete training before their first visit and retrain if non-compliant [38].

Figure 2.

Processes recommended or addressed in documents (N = 26).

Timing of Delivery. Seven documents (26.9%) outlined recommendations for the timing of education and training [1,4,23,30,35,38,42]. Recommendations included education and training be provided before visiting a resident, such as upon arrival to an LTC home or when scheduling visitation appointments [1,4,23,30,35,38,42].

Mode of Delivery. Twenty-three documents (88.5%) discussed modes of education and training delivery [1,3,4,5,8,23,24,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43]. Recommendations included in-person delivery (69.2%) [1,3,4,5,8,23,28,29,30,31,33,35,36,37,38,39,41,42,43], signage (50.0%) [4,8,23,26,28,29,30,31,35,36,37,38,42], and discussion/information sessions (19.2%) [1,8,33,35,43]. The CDC emphasized culturally diverse materials tailored to visitors’ language comprehension and education levels [29].

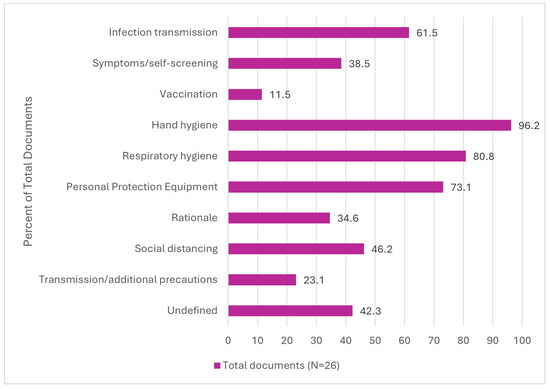

4.3.3. Sub-Question 3: What Content Is Included in the IPAC Education and Training Provided to Visitors of LTC Residents?

As outlined in Figure 3, documents included varied recommendations on content to include in the IPAC education and training provided to visitors of LTC residents. The recommended content most frequently included hand hygiene (96.2%) [1,3,4,5,8,23,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], respiratory hygiene (80.8%) [1,4,5,8,23,25,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,40,41,42,43], PPE usage (73.1%) [1,3,4,5,8,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], infection transmission (61.5%) [3,5,25,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,39,40,43], and social distancing (50.0%) [1,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,34,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. Eleven (42.3%) documents [8,23,24,25,27,29,36,37,38,41,43] included undefined IPAC content, described as “appropriate” [29,41], “other” [8,36,37], or “specific” IPAC practices [25]. The content recommended the least was vaccination (11.5%) [8,23,30].

Figure 3.

Content recommended or addressed in documents (N = 26).

4.3.4. Sub-Question 4: Who Provides the Education and Training to Visitors of LTC Residents?

The recommended education and training providers for LTC visitors in the included documents were IPAC professionals and/or designed individuals (42.3%) [8,25,27,28,30,31,33,34,37,40,41], and healthcare workers (19.2%), such as nurses [1,4,5,8,43].

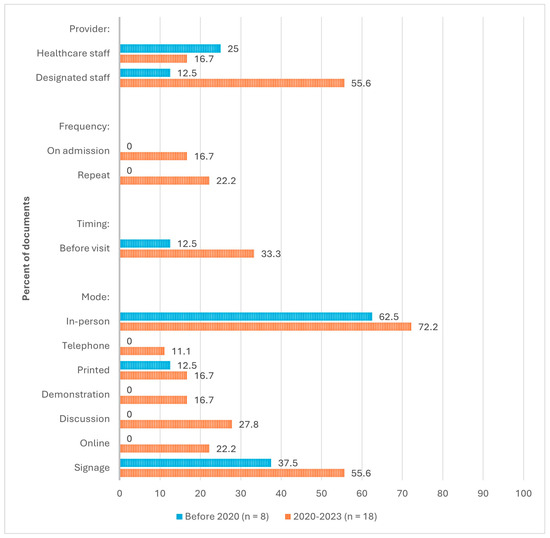

4.3.5. Sub-Question 5: How Has the Education and Training Provided to Visitors Evolved over Time (i.e., Pre-Pandemic, and Throughout the Pandemic)?

Evolution of Provider, Frequency, Timing, and Mode of Delivery. As depicted in Figure 4, the recommended provider of IPAC education and training to visitors in LTC was healthcare staff before 2020 (25%) [4,5], and this switched to designated staff (55.6%) [8,25,27,28,30,31,33,34,37,40,41] after 2020. Before 2020, documents did not include recommendations on the frequency and timing of education and training delivery. After 2020, visitor education and training were most frequently recommended to be repeated (22.2%) [27,31,38,41] and provided before a visit occurs (33.3%) [1,23,30,35,36,42]. Before 2020, the recommended education and training delivery modes were in-person (62.5%) [3,4,5,36,39] and through signage (37.5%) [4,26,36]. After 2020, the most frequently recommended modes remained as in-person (72.2%) [1,8,23,27,28,29,33,34,36,37,38,39,41,42,43,44] and through signage (55.6%) [8,23,28,31,35,37,38,42], and recommendations for delivery via telephone, print, demonstrations, discussions, and online modes were introduced.

Figure 4.

Evolution of recommended processes (N = 26).

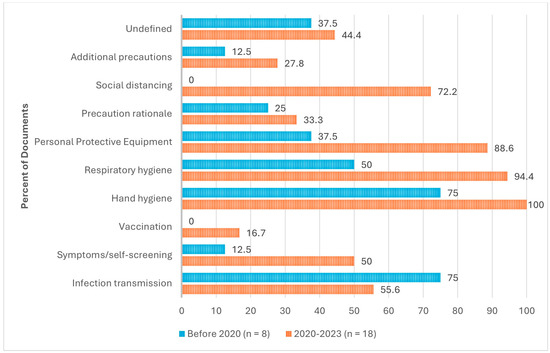

Evolution of Content. As shown in Figure 5, before 2020, the most frequently recommended content for IPAC education and training for LTC visitors was hand hygiene (75.0%) [3,4,5,25,29,39] and infection transmission (75.0%) [3,5,25,26,36,39]. After 2020, the most frequently recommended content was hand hygiene (100%), respiratory hygiene (94.4%) [1,8,23,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,40,41,42,43], and personal protective equipment usage (88.6%) [1,4,5,23,27,28,30,31,33,35,37,40,41,42]. The largest increase in content recommendation was social distancing, from zero documents before 2020 to 72.2% of documents after 2020 [1,23,27,28,31,32,34,37,38,40,41,42].

Figure 5.

Evolution of recommended content (N = 26).

5. Discussion

This paper provides new insights into the evolving landscape of IPAC education for visitors in LTC homes, highlighting both the progress and persistent gaps in education delivery. The findings suggest visitor education was typically recommended at the time of admission, during an infectious outbreak, and prior to visiting. It was predominantly delivered in person, and the core content included hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, and the use of PPE. However, significant gaps were identified in both the processes and content of IPAC education for visitors.

5.1. Changes in Education and Training Provider

Before 2020, there were no standardized recommendations regarding the qualifications of individuals responsible for visitor IPAC education and training in LTC. This review reveals a significant shift post-2020, where the responsibility has been more formally assigned to designated individuals with specialized IPAC training, such as IPAC professionals. This change reflects the increased awareness of the importance of IPAC in preventing the spread of infections, especially during outbreaks, and the growing recognition that care staff may not have the time or expertise to provide this education effectively [10,28]. In some countries, such as Canada, certified IPAC professionals are already recognized as key personnel for overseeing infection control practices [45], but LTC challenges related to staffing and financial constraints often prevent dedicated IPAC professionals from being present in all facilities, potentially leading to gaps in training delivery. Despite this, nurses remain key facilitators of IPAC initiatives in LTC, often bridging the gap between IPAC professionals, care staff, and visitors. Nurses possess clinical expertise and an established rapport with residents and visitors, making them well-positioned to ensure that IPAC education and prevention measures are effectively communicated and adhered to within the facility. They play an integral role in reinforcing IPAC guidelines, monitoring compliance, and addressing challenges in implementing IPAC practices, ultimately contributing to the safety and well-being of vulnerable residents [46].

5.2. Evolution of Timing and Frequency of Education

While the importance of repeated visitor education became clear in 2021, partway through the COVID-19 pandemic, this review underscores the need for standardized guidance on the frequency and timing of training and retraining. Evidence suggests that periodic retraining improves adherence to infection control measures [17], but there remains a lack of specificity about the optimal timing for such interventions. Future research should aim to develop best practices for training schedules, assisting LTC homes in balancing the need for effective visitor education with the practical constraints they face in resource allocation.

5.3. Delivery Methods

The methods of delivering IPAC education and training evolved significantly after 2020. Pre-2020, in-person training and signage materials were the most common methods. However, post-pandemic documents outlined varied delivery options, including online resources, telephone communication, and one-on-one sessions. This broader range of methods aligns with adult learning theory [47], recognizing that visitors in LTC homes have diverse learning preferences and needs. Offering multiple delivery modes could increase accessibility and engagement, which is especially important for addressing a wide range of literacy levels, language differences, and learning styles among visitors.

5.4. Content of IPAC Education

The content of IPAC education and training for visitors primarily focused on essential infection control measures, such as hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, and PPE usage, aligning with global public health recommendations from organizations like the World Health Organization and CDC [48]. However, a notable gap was identified in the inclusion of vaccination information—less than 12% of the documents reviewed recommended including this crucial content in visitor education and training. This is especially significant given the increasing role of vaccinations in preventing LTC infectious disease outbreaks, such as influenza, which are often associated with high resident mortality rates [4]. Including vaccination education in visitor training could strengthen infection prevention efforts, as vaccinated visitors are less likely to transmit infections [49,50].

Despite the growing evidence supporting the effectiveness of vaccines in reducing infectious diseases, vaccine hesitancy remains a major global health threat [50]. A recent systematic review highlighted that vaccine hesitancy is particularly prevalent among groups who question the necessity of vaccines, lack trust in vaccination authorities, or are unaware of the rigorous processes involved in vaccine development and their health impacts [50]. The review suggests that addressing vaccine hesitancy requires targeted education and training. This underscores the importance of incorporating vaccination information into visitor IPAC education programs, as it could help reduce the transmission of infections in LTC homes, further protecting vulnerable residents.

5.5. Lack of Standardized Curricula and Implementation Guidance

Another important finding of this review is the absence of standardized curricula or detailed guidance on implementing IPAC education and training for visitors. While guidelines exist, there is limited information on how these recommendations are translated into practice in individual facilities, leading to inconsistent implementation. The absence of detailed, standardized curricula may result in variations in the effectiveness of visitor education, which could undermine infection prevention efforts. This highlights the need for regulatory bodies to create clear, evidence-based, universal guidance on LTC visitor IPAC education and training to tackle inconsistencies across various areas and facilities.

5.6. Strengths of the Review

The timing of this review, amidst the ongoing challenges posed by COVID-19, highlights its relevance. The pandemic has raised important questions about visitor access and the role of IPAC in maintaining safe visitations during outbreaks. This review offers insights into how LTC homes can manage safe visitation while minimizing infection risks. It also provides a comprehensive overview of IPAC practices across multiple global health concerns, including influenza, SARS, Ebola, and COVID-19. By analyzing documents spanning decades, this review highlights the evolving nature of IPAC education and training for LTC visitors and identifies key gaps that need to be addressed in future research and policy.

5.7. Limitations

Despite the strengths of this scoping review, several limitations should be noted. One key limitation is the lack of international sources, with 84.6% of the reviewed documents originating from Canada and the U.S., leaving gaps in the information from other countries. To reduce the bias in source representation in future reviews, we will look into validated tools for translating sources reliably into English and collaborate with international researchers. The scoping review methodology also limits the ability to assess the quality of the evidence, preventing conclusions about the effectiveness of IPAC education and training. Additionally, some relevant sources may have been unintentionally excluded during screening. Lastly, while the review maps literature from 1990 to early 2023, the exclusion of more recent documents restricts its findings, as research on educating LTC visitors about IPAC has significantly increased in the past year.

5.8. Implications for Policy and Practice

This review highlights several important implications for policy and practice. Recently, maintaining safe visitation during infectious outbreaks, particularly during COVID-19, has become a priority. However, significant inconsistencies remain in the content, timing, frequency, and qualifications associated with delivering IPAC education and training to visitors. Given the global importance of IPAC, there is an urgent need for standardized protocols for educating LTC visitors. The lack of universally accepted guidelines presents a unique opportunity for international collaboration to share best practices, create consistency, and enhance training programs. For instance, a systematic review of LTC IPAC programs found that those incorporating educational components, along with monitoring and feedback, were effective in reducing healthcare-associated infections and promoting behavior change among healthcare workers [17]. Establishing global standards for IPAC education that includes training for visitors could ensure that all visitors are well-equipped with the knowledge necessary to minimize the spread of infections. Nursing practice is essential to achieving this, as nurses are often on the front lines, directly engaging with visitors and facilitating these important educational efforts.

5.9. Implications for Research

Future research should focus on the risks posed by visitors entering LTC homes during outbreaks, to inform best practices for IPAC education and training. Additionally, assessing the effectiveness of IPAC education and training in changing visitor behaviors and LTC infection rates will be important for future research. Research is needed to evaluate whether unregulated LTC staff have the skills to educate visitors, considering their infection control knowledge, access to updated resources, and ability to balance care with education responsibilities. Finally, ongoing research is essential in order to adapt IPAC training programs to evolving infectious diseases and to evaluate the sustainability of IPAC programs in LTC settings. Nursing practice is essential to achieving this, as nurses are often on the front lines, directly engaging with visitors and facilitating these important educational efforts.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review addresses the ongoing challenge of infection prevention in LTC homes. This review found there is no standardized approach to IPAC education and training for LTC visitors, providing an opportunity for significant policy reform and research development. The findings highlight the need to strengthen and standardize comprehensive IPAC education and training programs for LTC visitors. By addressing the gaps in current visitor education programs, this review provides a foundation for future research and policy development aimed at enhancing the safety and quality of life in LTC settings.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/nursrep15010017/s1, SRQR Reporting Guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.D., R.M. (Rose McCloskey), L.K.-B., P.M., C.G., N.T., and R.M. (Rachel MacLean); methodology, R.M. (Rachel MacLean), L.K.-B., and R.M. (Rose McCloskey); software, R.M. (Rose McCloskey); search strategy and database searching, R.W.; formal analysis, R.M. (Rachel MacLean); data curation, R.M. (Rachel MacLean); writing—original draft preparation, R.M. (Rachel MacLean); writing—review and editing, R.M. (Rachel MacLean) and P.D.; funding acquisition, P.D., R.M. (Rose McCloskey), and L.K.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Government of New Brunswick, grant number C0076.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No ethical approval was required for this study.

Informed Consent Statement

No informed consent was required for this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Public Involvement Statement

There was no public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews.

Use of Artificial Intelligence

AI-assisted tools were used during manuscript editing to aid in clarity.

Conflicts of Interest

This study was conducted as part of the first author’s Master’s thesis project. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A. Search Strategy

Embase (Ovid) search conducted on 15 June 2022

Date Limit: 1990 onwards

| No | Query | Results |

| #1 | ((‘old age’ OR ‘aged care’ OR elder* OR nursing) NEAR/1 (care OR residence OR residential OR environment OR home OR facility OR setting)):ab,ti | 78,055 |

| #2 | ‘long term care’:ab,ti | 29,246 |

| #3 | ‘residential home’/exp | 7951 |

| #4 | ‘nursing home’/exp | 60,556 |

| #5 | ‘home for the aged’/exp | 12,858 |

| #6 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 | 142,783 |

| #7 | handwashing:ab,ti | 3859 |

| #8 | ‘hand washing’:ab,ti | 4255 |

| #9 | ‘hand hygiene’:ab,ti | 8586 |

| #10 | sanitiz*:ab,ti | 3988 |

| #11 | sanitis*:ab,ti | 335 |

| #12 | cleanser*:ab,ti | 1694 |

| #13 | disinfect*:ab,ti | 41,531 |

| #14 | glov*:ab,ti | 16,240 |

| #15 | mask*:ab,ti | 115,698 |

| #16 | ‘patient isolat*’:ab,ti | 1815 |

| #17 | ‘no visit*’:ab,ti | 464 |

| #18 | ((guest* OR visit*) NEAR/2 (‘not allow*’ OR ‘not permit*’ OR prohibit* OR ‘closed to’)):ab,ti | 115 |

| #19 | vaccin*:ab,ti | 444,131 |

| #20 | ((infection OR virus OR covid OR ‘covid 19’) NEAR/1 (prevent* OR mitigat* OR control* OR contain* OR manag*)):ab,ti | 66,115 |

| #21 | quarantine*:ab,ti | 10,420 |

| #22 | ppe:ab,ti | 8022 |

| #23 | ‘personal protective equipment’ | 9258 |

| #24 | ‘glove’/exp | 12,053 |

| #25 | ‘mask’/exp | 49,690 |

| #26 | ‘patient isolation’/exp | 2128 |

| #27 | ‘quarantine’/exp | 11,859 |

| #28 | ‘infection prevention’/exp | 72,778 |

| #29 | ‘hand washing’/exp | 18,847 |

| #30 | ‘hand sanitizer’/exp | 1527 |

| #31 | #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 OR #23 OR #24 OR #25 OR #26 OR #27 OR #28 OR #29 OR #30 | 784,537 |

| #32 | volunteer*:ti,ab | 281,888 |

| #33 | unpaid:ti,ab | 2792 |

| #34 | ‘un paid’:ti,ab | 9 |

| #35 | ‘non paid’:ti,ab | 107 |

| #36 | ‘non staff’:ti,ab | 51 |

| #37 | ‘non employee*’:ti,ab | 57 |

| #38 | visit*:ti,ab | 446,933 |

| #39 | guest*:ti,ab | 21,467 |

| #40 | friend*:ti,ab | 135,624 |

| #41 | famil*:ti,ab | 1,531,670 |

| #42 | parent*:ti,ab | 592,030 |

| #43 | mother*:ti,ab | 318,044 |

| #44 | father*:ti,ab | 62,242 |

| #45 | daughter*:ti,ab | 34,534 |

| #46 | sibling*:ti,ab | 76,960 |

| #47 | son:ti,ab | 20,589 |

| #48 | sons:ti,ab | 119,372 |

| #49 | brother*:ti,ab | 22,333 |

| #50 | sister*:ti,ab | 49,571 |

| #51 | husband*:ti,ab | 23,580 |

| #52 | wife:ti,ab | 8772 |

| #53 | ‘significant other*’:ti,ab | 5871 |

| #54 | ‘spouse*’:ti,ab | 25,094 |

| #55 | ‘designated support*’ | 18 |

| #56 | ‘family’/exp | 578,542 |

| #57 | ‘friend’/exp | 23,654 |

| #58 | ‘health visitor’/exp | 1694 |

| #59 | ‘volunteer’/exp | 59,662 |

| #60 | #32 OR #33 OR #34 OR #35 OR #36 OR #37 OR #38 OR #39 OR #40 OR #41 OR #42 OR #43 OR #44 OR #45 OR #46 OR #47 OR #48 OR #49 OR #50 OR #51 OR #52 OR #53 OR #54 OR #55 OR #56 OR #57 OR #58 OR #59 | 3,369,651 |

| #61 | #6 AND #31 AND #60 | 796 |

Medline R (Ovid) search conducted on 15 June 2022

Date Limit: 1990 onwards

| No. | Query | Results |

| 1 | ((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) adj1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting)).ab,ti. | 62,785 |

| 2 | “long term care”.ab,ti. | 23,329 |

| 3 | Long-Term Care/ | 27,749 |

| 4 | Residential Facilities/ or Homes for the Aged/ or Nursing Homes/ | 48,686 |

| 5 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 | 122,825 |

| 6 | handwashing.ab,ti. | 2669 |

| 7 | “hand washing”.ab,ti. | 3084 |

| 8 | “hand hygiene”.ab,ti. | 5539 |

| 9 | “sanitiz*”.ab,ti. | 3416 |

| 10 | “sanitis*”.ab,ti. | 276 |

| 11 | “cleanser*”.ab,ti. | 1176 |

| 12 | “disinfect*”.ab,ti. | 33,926 |

| 13 | “glov*”.ab,ti. | 12,201 |

| 14 | “mask*”.ab,ti. | 92,883 |

| 15 | “patient isolat*”.ab,ti. | 1401 |

| 16 | “no visit*”.ab,ti. | 279 |

| 17 | ((guest* or visit*) adj2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”)).ab,ti. | 96 |

| 18 | “vaccin*”.ab,ti. | 371,756 |

| 19 | ((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) adj1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*)).ab,ti. | 48,381 |

| 20 | “quarantine*”.ab,ti. | 10,346 |

| 21 | ppe.ab,ti. | 6155 |

| 22 | “personal protective equipment”.ab,ti. | 7521 |

| 23 | masks/ or gloves, protective/ | 8857 |

| 24 | Patient Isolation/ | 4425 |

| 25 | Quarantine/ | 5906 |

| 26 | Infection Control/ | 28,378 |

| 27 | Hand Disinfection/ | 6229 |

| 28 | 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 | 598,980 |

| 29 | “volunteer*”.ab,ti. | 208,286 |

| 30 | unpaid.ab,ti. | 2202 |

| 31 | “un paid”.ab,ti. | 5 |

| 32 | “non paid”.ab,ti. | 60 |

| 33 | “non staff”.ab,ti. | 34 |

| 34 | “non employee*”.ab,ti. | 36 |

| 35 | “visit*”.ab,ti. | 276,560 |

| 36 | “guest*”.ab,ti. | 21,026 |

| 37 | “friend*”.ab,ti. | 111,047 |

| 38 | “famil*”.ab,ti. | 1,203,235 |

| 39 | “parent*”.ab,ti. | 462,426 |

| 40 | “mother*”.ab,ti. | 245,932 |

| 41 | “father*”.ab,ti. | 46,440 |

| 42 | “daughter*”.ab,ti. | 27,679 |

| 43 | “sibling*”.ab,ti. | 54,316 |

| 44 | son.ab,ti. | 19,290 |

| 45 | sons.ab,ti. | 18,109 |

| 46 | “brother*”.ab,ti. | 14,803 |

| 47 | “sister*”.ab,ti. | 42,602 |

| 48 | “husband*”.ab,ti. | 19,794 |

| 49 | “wife*”.ab,ti. | 6569 |

| 50 | “significant other*”.ab,ti. | 4491 |

| 51 | “spouse*”.ab,ti. | 19,043 |

| 52 | “designated support*”.ab,ti. | 6 |

| 53 | Friends/ | 6333 |

| 54 | Family/ | 82,568 |

| 55 | Visitors to Patients/ | 2267 |

| 56 | Volunteers/ | 10,571 |

| 57 | 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 | 2,429,737 |

| 58 | 5 and 28 and 57 | 484 |

CINAHL with Full-text (EBSCOhost) search conducted on 15 June 2022

Date Limit: 1990 onwards

| No | Query | Results |

| S1 | TI (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting))) OR AB (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting))) | 76,468 |

| S2 | TI “long term care” OR AB “long term care” | 18,483 |

| S3 | (MH “Long Term Care”) | 27,483 |

| S4 | (MH “Residential Care”) | 7052 |

| S5 | (MH “Residential Facilities+”) | 34,654 |

| S6 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 | 122,958 |

| S7 | TI handwashing OR AB handwashing | 1431 |

| S8 | TI “hand washing” OR AB “hand washing” | 1383 |

| S9 | TI “hand hygiene” OR AB “hand hygiene” | 4125 |

| S10 | TI sanitiz* OR AB sanitiz* | 849 |

| S11 | TI sanitis* OR AB sanitis* | 86 |

| S12 | TI cleanser* OR AB cleanser* | 537 |

| S13 | TI disinfect* OR AB disinfect* | 5919 |

| S14 | TI glov* OR AB glov* | 4200 |

| S15 | TI mask* OR AB mask* | 19,169 |

| S16 | TI “patient isolat*” OR AB “patient isolat*” | 263 |

| S17 | TI “no visit*” OR AB “no visit*” | 129 |

| S18 | TI (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”))) OR AB (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”))) | 354 |

| S19 | TI vaccin* OR AB vaccin* | 63,340 |

| S20 | TI (((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*))) OR AB (((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*))) | 28,224 |

| S21 | TI quarantine* OR AB quarantine* | 2151 |

| S22 | TI PPE OR AB PPE | 2641 |

| S23 | TI “personal protective equipment” OR AB “personal protective equipment” | 3714 |

| S24 | (MH “Personal Protective Equipment”) OR (MH “Masks”) OR (MH “Gloves”) | 9309 |

| S25 | (MH “Patient Isolation”) | 2677 |

| S26 | (MH “Quarantine”) | 1645 |

| S27 | (MH “Infection Control”) OR (MH “Handwashing”) OR (MH “Immunization”) OR (MH “Sterilization and Disinfection”) | 72,053 |

| S28 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 OR S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 | 168,327 |

| S29 | TI volunteer* OR AB volunteer* | 48,653 |

| S30 | TI unpaid OR AB unpaid | 1511 |

| S31 | TI “un paid” OR AB “un paid” | 5 |

| S32 | TI “non paid” OR AB “non paid” | 36 |

| S33 | TI “non staff” OR AB “non staff” | 19 |

| S34 | TI “non employee” OR AB “non employee” | 7 |

| S35 | TI visit* OR AB visit* | 119,467 |

| S36 | TI guest* OR AB guest* | 9863 |

| S37 | TI friend* OR AB friend* | 41,910 |

| S38 | TI famil* OR AB famil* | 309,983 |

| S39 | TI parent* OR AB parent* | 161,981 |

| S40 | TI mother* OR AB mother* | 94,869 |

| S41 | TI father* OR AB father* | 18,984 |

| S42 | TI daughter* OR AB daughter* | 6113 |

| S43 | TI sibling* OR AB sibling* | 11,926 |

| S44 | TI son OR AB son | 29,077 |

| S45 | TI sons OR AB sons | 29,077 |

| S46 | TI brother* OR AB brother* | 2767 |

| S47 | TI sister* OR AB sister* | 4953 |

| S48 | TI husband* OR AB husband* | 6118 |

| S49 | TI wife* OR AB wife* | 2864 |

| S50 | TI “significant other*” OR AB “significant other*” | 2996 |

| S51 | TI spouse* OR AB spouse* | 10,129 |

| S52 | TI “designated support*” OR AB “designated support*” | 3 |

| S53 | (MH “Family”) | 45,323 |

| S54 | (MH “Visitors to Patients”) | 2337 |

| S55 | (MH “Volunteer Workers”) | 14,910 |

| S56 | S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48 OR S49 OR S50 OR S51 OR S52 OR S53 OR S54 OR S55 | 727,132 |

| S57 | S6 AND S28 AND S56 | 468 |

ERIC (EBSCOhost) search conducted on 15 June 2022

Date Limit: 1990 onwards

| No | Query | Results |

| S1 | TI (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting))) OR AB (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting))) | 2306 |

| S2 | TI “long term care” OR AB “long term care” | 828 |

| S3 | DE “Nursing Homes” | 1246 |

| S4 | DE “Residential Institutions” | 1087 |

| S5 | DE “Residential Care” | 1268 |

| S6 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 | 5041 |

| S7 | TI handwashing OR AB handwashing | 84 |

| S8 | TI “hand washing” OR AB “hand washing” | 89 |

| S9 | TI “hand hygiene” OR AB “hand hygiene” | 28 |

| S10 | TI sanitiz* OR AB sanitiz* | 120 |

| S11 | TI sanitis* OR AB sanitis* | 13 |

| S12 | TI cleanser* OR AB cleanser* | 7 |

| S13 | TI disinfect* OR AB disinfect* | 132 |

| S14 | TI glov* OR AB glov* | 248 |

| S15 | TI mask* OR AB mask* | 2295 |

| S16 | TI “patient isolat*” OR AB “patient isolat*” | 1 |

| S17 | TI “no visit*” OR AB “no visit*” | 6 |

| S18 | TI (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”))) OR AB (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”))) | 94 |

| S19 | TI vaccin* OR AB vaccin* | 707 |

| S20 | TI (((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*))) OR AB (((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*))) | 397 |

| S21 | TI quarantine* OR AB quarantine* | 100 |

| S22 | TI PPE OR AB PPE | 61 |

| S23 | TI “personal protective equipment” OR AB “personal protective equipment” | 65 |

| S24 | S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 | 4262 |

| S25 | TI volunteer* OR AB volunteer* | 13,750 |

| S26 | TI unpaid OR AB unpaid | 552 |

| S27 | TI “un paid” OR AB “un paid” | 3 |

| S28 | TI “non paid” OR AB “non paid” | 14 |

| S29 | TI “non staff” OR AB “non staff” | 6 |

| S30 | TI “non employee” OR AB “non employee” | 5 |

| S31 | TI visit* OR AB visit* | 21,111 |

| S32 | TI guest* OR AB guest* | 2129 |

| S33 | TI friend* OR AB friend* | 19,941 |

| S34 | TI famil* OR AB famil* | 128,316 |

| S35 | TI parent* OR AB parent* | 126,111 |

| S36 | TI mother* OR AB mother* | 25,378 |

| S37 | TI father* OR AB father* | 9012 |

| S38 | TI daughter* OR AB daughter* | 2539 |

| S39 | TI sibling* OR AB sibling* | 4082 |

| S40 | TI son OR AB son | 2449 |

| S41 | TI sons OR AB sons | 2449 |

| S42 | TI brother* OR AB brother* | 1412 |

| S43 | TI sister* OR AB sister* | 1355 |

| S44 | TI husband* OR AB husband* | 1933 |

| S45 | TI wife* OR AB wife* | 1261 |

| S46 | TI “significant other*” OR AB “significant other*” | 957 |

| S47 | TI spouse* OR AB spouse* | 2480 |

| S48 | TI “designated support*” OR AB “designated support*” | 4 |

| S49 | DE “Family (Sociological Unit)” OR DE “African American Family” OR DE “Daughters” OR DE “Dependents” OR DE “Heads of Households” OR DE “Homemakers” OR DE “One Parent Family” OR DE “Parents” OR DE “Siblings” OR DE “Sons” OR DE “Spouses” OR DE “Widowed” | 26,255 |

| S50 | DE “Volunteers” OR DE “Student Volunteers” | 6442 |

| S51 | S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32 OR S33 OR S34 OR S35 OR S36 OR S37 OR S38 OR S39 OR S40 OR S41 OR S42 OR S43 OR S44 OR S45 OR S46 OR S47 OR S48 OR S49 OR S50 | 277,745 |

| S52 | S6 AND S24 AND S51 | 23 |

AgeLine (EBSCOhost) search conducted on 14 December 2022

Date Limit: 1990 onwards

| No | Query | Limiters/ Expanders | Last Run Via | Results |

| S1 | (((TI (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting))) OR AB (((“old age” or “aged care” or elder* or nursing) N1 (care or residence or residential or environment or home or facility or setting)))) OR (TI “long term care” OR AB “long term care”))) AND ((TI handwashing OR AB handwashing) OR (TI “hand washing” OR AB “hand washing”) OR (TI “hand hygiene” OR AB “hand hygiene”) OR (TI sanitiz* OR AB sanitiz*) OR (TI sanitis* OR AB sanitis*) OR (TI cleanser* OR AB cleanser*) OR (TI disinfect* OR AB disinfect*) OR (TI glov* OR AB glov*) OR (TI mask* OR AB mask*) OR (TI “patient isolat*” OR AB “patient isolat*”) OR (TI “no visit*” OR AB “no visit*”) OR (TI (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”))) OR AB (((guest* or visit*) N2 (“not allow*” or “not permit*” or prohibit* or “closed to”)))) OR (TI vaccin* OR AB vaccin*) OR (TI (((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*))) OR AB ( ((infection or virus or covid or “covid 19”) N1 (prevent* or mitigat* or control* or contain* or manag*)))) OR (TI quarantine* OR AB quarantine*) OR (TI PPE OR AB PPE) OR (TI “personal protective equipment” OR AB “personal protective equipment”))) AND ((TI volunteer* OR AB volunteer*) OR (TI unpaid OR AB unpaid) OR (TI “un paid” OR AB “un paid”) OR (TI “non paid” OR AB “non paid”) OR (TI “non staff” OR AB “non staff”) OR (TI “non employee” OR AB “non employee”) OR (TI visit* OR AB visit*) OR (TI guest* OR AB guest*) OR (TI friend* OR AB friend*) OR (TI famil* OR AB famil*) OR (TI parent* OR AB parent*) OR (TI mother* OR AB mother*) OR (TI father* OR AB father*) OR (TI daughter* OR AB daughter*) OR (TI sibling* OR AB sibling*) OR (TI son OR AB son) OR (TI brother* OR AB brother*) OR (TI sister* OR AB sister*) OR (TI husband* OR AB husband*) OR (TI wife* OR AB wife*) OR (TI “significant other*” OR AB “significant other*”) OR (TI spouse* OR AB spouse*) OR (TI “designated support*” OR AB “designated support*”))) | Expanders—Apply equivalent subjects Search modes—Boolean/Phrase | Interface—EBSCOhost Research Databases Search Screen—Advanced Search | 1757 |

Appendix B. Grey Literature Search Strategy

Table A1.

Grey Literature Search of Long-Term Care Home Associations.

Table A1.

Grey Literature Search of Long-Term Care Home Associations.

| Association | Country | Relevant Documents Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Aged and Community Services Australia | Australia | |

| Aged Care Guild | Australia | |

| Agency for Integrated Care | Singapore | Agency for Integrated Care Caregiver Training Course Summary |

| Alberta Caregivers Association | Canada | |

| Alberta Continuing Care Association | Canada | |

| American Health Care Association | USA | Sample Policy for Emergent Infectious Diseases for Skilled Nursing Care Centers |

| Assisted Living Federation of America | USA | |

| Association of Healthcare Providers India | India | |

| British Columbia Care Providers Association | Canada | |

| Canadian Association for Long Term Care | Canada | |

| Canadian Caregiver Coalition | Canada | |

| Care England | England | |

| Caregiver Action Network | USA | |

| Caregiver India Foundation | India | |

| Caregiver Saathi | India | |

| Caregivers Alberta | Canada | |

| Caregivers Association of Nigeria | Nigeria | |

| Caregivers Nova Scotia | Canada | |

| Carers Alliance | Hong Kong | |

| Carers Australia | Australia | |

| Carers NSW | Australia | |

| Carers NZ | New Zealand | |

| Carers Queensland | Australia | |

| Carers Trust | United Kingdom | |

| Carers UK | United Kingdom | |

| Carers Victoria | Australia | |

| Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services | USA | |

| Eldercare Locator | USA | |

| Family Caregiver Alliance | USA | |

| Family Caregivers of British Columbia | Canada | |

| Family Carers Ireland | Ireland | |

| HelpAge India | India | |

| Irish Association of Social Care Worker | Ireland | |

| Leading Age Services Australia | Australia | |

| LeadingAge | USA | |

| Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program | USA | |

| Malaysian Caregivers Association | Malaysia | |

| Manitoba Association of Residential and Community Care | Canada | |

| National Alliance for Caregiving | USA | |

| National Association of Aged Care Providers | Australia | |

| National Care Association | England | |

| National Center for Assisted Living | USA | |

| National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care | USA | |

| New Brunswick Association of Nursing Homes | Canada | |

| New Zealand Aged Care Association | New Zealand | |

| Northern Ireland Association of Homes for the Aged | Ireland | |

| Nursing Homes Ireland | Ireland | |

| Nursing Homes of Nova Scotia Association | Canada | |

| Ontario Caregiver Organization | Canada | |

| Ontario Long Term Care Association | Canada | |

| PEI Association for Community Long Term Care Homes | Canada | |

| PEI Association of Licensed Community Care Facilities | Canada | |

| Saskatchewan Association of Long-Term Care Providers | Canada | |

| Scottish Care | Scotland | |

| Seniors Newfoundland and Labrador | Canada | |

| South African Care Forum | South Africa | |

| South African Care Forum | South Africa | |

| South African Care Workers Association | South Africa | |

| The Princess Royal Trust for Carers | United Kingdom | |

| Well Spouse Association | USA | |

| Yukon Department of Health and Social Services | Canada | |

| Total Documents Identified | 2 |

Table A2.

Grey Literature Search of Long-Term Care Home Organizations and Research Centers.

Table A2.

Grey Literature Search of Long-Term Care Home Organizations and Research Centers.

| Organization | Country | Relevant Documents Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Agency for Research in Healthcare Quality | USA | |

| Australian Association of Gerontology | Australia | |

| Australian Institute of Health and Welfare | Australia | |

| Brown University Center for Gerontology and Healthcare Research | USA | |

| Canadian Centre for Elder Law | Canada | |

| Canadian Institute for Health Information | Canada | |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | USA | IPAC Recommendations for LTC Updated 2023 |

| Centre for Excellence in Population Ageing Research | Australia | |

| Centre for Gerontology and Rehabilitation | Ireland | |

| Centre for Learning, Research and Innovation in LTC | Canada | New IPAC eLearning course |

| Institute for Health System Solutions and Virtual Care | Canada | |

| Institute for Research on Aging | Canada | |

| International Long Term Care Policy Network | International | |

| Irish Centre for Social Gerontology | Ireland | |

| Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing | Ireland | |

| Manitoba Centre for Health Policy | Canada | |

| Marcus Institute for Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife | USA | |

| Massey University, Health and Ageing Research Team | New Zealand | |

| National Ageing Research Institute | Australia | |

| National Institute on Aging | Canada | |

| National Institute on Aging | USA | |

| New Zealand Aged Care Association Research Center | New Zealand | |

| Rand Corporation Center for the Study of Aging | USA | |

| South African Medical Research Council | South Africa | |

| Stanford Center on Longevity | USA | |

| University of Auckland, School of Nursing | New Zealand | |

| University of Cape Town, Division of Geriatric Medicine | South Africa | |

| University of East Anglia, Centre for Research on Ageing and Gender | England | |

| University of Leeds, Centre for Research in Nursing and Midwifery | England | |

| University of Otago, New Zealand Institute for Research on Aging | New Zealand | |

| University of Oxford, Oxford Institute of Population Ageing | England | |

| University of Sheffield, School of Nursing and Midwifery | United Kingdom | |

| University of Southampton, Centre for Research on Ageing | England | |

| World Health Organization | International | Infection Prevention and Control for Long-Term Care Facilities in the Context of Covid 19 |

| Total Documents Identified | 3 |

Note. USA = United States of America; LTC = Long-term care; IPAC = Infection prevention and control.

Table A3.

Grey Literature Obtained via the Google Search Engine.

Table A3.

Grey Literature Obtained via the Google Search Engine.

| Website | Country | Relevant Documents Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Australian Government | Australia | Visiting an aged care home during an outbreak |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Canada | Core Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Safe Healthcare Delivery in All Settings |

| Fraser Health | Canada | Infection Control Manual—Residential Care |

| Ministry of Long-Term Care | Canada | Infection prevention and control program guidance |

| Missouri Department of Health Services | USA | Infection Control Guidelines for Long-Term Care Facilities |

| Ontario Health | Canada | Infection Prevention and Control Standard for Long-Term Care Homes |

| Ontario Public Health | Canada | Visitors’ policy in long-term care homes during COVID-19 pandemic |

| Provincial Infection Control Network | Canada | Residential care infection prevention and control manual. |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Canada | Prevention and Control of Influenza during a Pandemic for All Healthcare Settings |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Canada | The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2013 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Canada | Clostridium Difficile Infection |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Canada | Routine Practices and Additional Precautions for Preventing the Transmission of Infection in Healthcare Settings Part B |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | Canada | Infection prevention and control for COVID-19: Interim guidance for long-term care homes |

| ResCare Community Living | USA | Patient & Family Education Package |

| UniversalCare | Canada | Infection Prevention and Control Policy |

| Total Documents Identified | 15 |

Note. USA = United States of America.

Appendix C. Characteristics of Included Studies

Table A4.

Document Characteristics for IPAC Education and Training for LTC Visitors (N = 26).

Table A4.

Document Characteristics for IPAC Education and Training for LTC Visitors (N = 26).

| Author, Year | Country | Type | Audience/Sample | Setting(s) | Phenomena/Purpose | Relevant Findings/Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency for IntegratedCare, 2023 [32] | SG | Education Resource | Family | LTCF | Training course on providing safe care. | The course requires attendees to understand standard precautions to prevent infection spread. |

| American Healthcare Association, 2015 [35] | US | Policy | Healthcare workers | LTCF | Guide preparation for infectious diseases. | Families should be provided with education about the outbreak and the center’s response strategy. |

| Australian Government, 2021 [22] | AU | Guideline | Healthcare workers | LTCF | Guide IPAC practices based on COVID-19 status in the community. | Visitors are essential to aged care to prevent resident deconditioning. IPAC education should be provided to visitors during all phases of COVID-19 outbreaks. |

| Australian Government, 2023 [34] | AU | Education Resources | Visitors | LTCF | Education on key practices to carry out when visiting LTC during an infectious outbreak. | Visitors are prompted on what to do before, during, and after a visit for safety during an infectious outbreak. |

| Augustin & Barry, 2021 [39] | CA | Position Statement | IPAC Professionals | LTCF | Describe and recommended IPAC practices. | IPAC education should be provided to all visitors of LTC homes. |

| Bergman, 2020 [42] | US; CA | Consensus Paper | Experts—LTC | LTCF | Generate consensus to guide visitation by essential family caregivers and visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic. | Consensus was reached on 12 statements related to visitor guidance including IPAC strategies. |

| CDC, 2022 [28] | US | Guideline | Healthcare Organizations/ Policy Makers | All * | Core IPAC guidelines for safe healthcare delivery in all healthcare settings. | Visitors to all healthcare facilities should be provided with IPAC education. |

| CDC, 2023 [29] | US | Guideline | Healthcare workers | All | Introduce a framework to guide selection and implementation of specific IPAC practices based on individual circumstances (e.g., universal source control). | Facilities should provide instruction before a visitor enters a patient’s room on IPAC practices and should refrain from visiting if sick. |

| Centers for Learning, Research, &Innovation, 2023 [33] | CA | Education Resource | Healthcare workers/ Visitors | LTCF | Educate and practice applying IPAC principles to care. | Focus on breaking the chain of transmission through routine practices, best practices, and hand hygiene. |

| Fraser Health, 2013 [25] | CA | Guideline | Healthcare workers | LTCF | Guidelines for IPAC for residential care. | Visitors should be educated on IPAC |

| Missouri Health & Senior Services, 2005 [23] | US | Guideline | Healthcare workers | LTCF | Guide for establishing high-quality IPAC in MDHS LTC. | Visitor education is recommended when there is a suspected or known disease or organism in the facility. |

| Ontario Health, 2022 [40] | CA | Standard | IPAC Professionals/ LTCF | LTCF | Standard of current evidence-based IPAC practices in LTC. | LTC should have IPAC professional and IPAC program that includes educating visitors. |

| Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care, 2021 [26] | CA | Guideline | LTCF | LTCF | Guide implementation of IPAC programs in LTC. | IPAC programs need to contain education for visitors. |

| Ontario Public Health, 2022 [38] | CA | Policy | Healthcare workers /Visitors | LTCF | Visitor policy during COVID-19 pandemic. | All visitors to Ontario LTC homes are to be educated on IPAC practices. |

| PHAC, 2011 [4] | CA | Guideline | Healthcare workers | All | Guide IPAC and occupational health planning and management of pandemic Influenza. | During an influenza outbreak, visitors should only visit LTC if they’ve already had influenza or were immunized. If visitors have symptoms, they should be educated. |

| PHAC, 2013 [38] | CA | Report | Healthcare workers | All | Describe state of HAIs; educate, raise awareness, and provide recommendations to prevent HAIs. | 80% of infections are spread by visitors, patients, and healthcare workers (ie., MRSA, C. difficile, staph). Facilities need to educate visitors on IPAC. |

| PHAC, 2013 [3] | CA | Guideline | Healthcare workers | LTCF | Guide IPAC for management of residents with C. difficile infection. | Recommend visitors be educated about the IPAC precautions in place. Any visitor participating in resident care should be educated on personal-protective equipment (PPE). |

| PHAC, 2017 [5] | CA | Guideline | Healthcare workers/ IPAC Professionals | All | Guide routine practices and additional precautions for preventing transmission of HAIs. | Healthcare workers should educate visitors on IPAC practices as indicated. Visitors participating in care should be educated about PPE. |

| PHAC, 2021 [27] | CA | Guideline | LTCF | LTCF | Update and guide IPAC for COVID-19. | Visitors should be instructed on IPAC practices and refrain from visiting if sick. |

| Provincial Infection Control Network, 2011 [24] | CA | Guideline | LTCF | LTCF | Guide LTC homes on the current best practices for preventing and controlling infections. | The basis of good IPAC practice is through educating staff, residents, and visitors. |

| ResCare CommunityLiving, 2020 [31] | US | Education Resources | Visitors | Alternate Level of Care Facilities | Describe and evaluate methods to mitigate the spread of COVID-19, e.g., visitor education resources. | Visitor education package provides information on COVID-19 IPAC practices. |

| Siegel, 2023 [8] | US | Guideline | Healthcare workers/ Policy Makers | All | Guide isolation precautions, IPAC program development, implementation, and evaluation. | Visitors are sources of many HAIs (i.e., pertussis, influenza, and SARS-CoV). Visitors should be educated on IPAC practices. |

| Stefanacci, 2020 [41] | US | Opinion Paper | Policy Makers | LTCF | Discuss a 4S process for safer visitations based on CDC recommendations. | The 4S process for safer visitations to LTC includes scheduling and education, screening, social distancing. and PPE, and an outside setting. |

| Tupper, 2020 [1] | CA | Opinion Paper | Policy Makers | LTCF | Describe importance of visitors and indications for clinical practice. | Prioritization of IPAC without ensuring resident psychosocial needs are protected is a short-sighted approach that will lead to harm. |

| UniversalCare, 2022 [36] | CA | Policy | LTCF | LTCF | Policy for pandemics, epidemics, and outbreaks. | Visitors to LTC homes need to be educated and trained on IPAC and be compliant with practices. |

| WHO, 2021 [30] | INT | Guideline | Healthcare workers/ Visitors | LTCF | Guide IPAC to prevent COVID-19 and support safe visiting for residents’ well-being. | Adequate visitor IPAC training and education by an IPAC professional is essential to reduce the risk of COVID-19 among LTC residents. |

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; WHO = World Health Organization; SG = Singapore; CA = Canada, US = United States of America; AU = Australia; INT = International; LTCF = Long-term care facilities; IPAC = Infection prevention and control. * “All” settings includes long-term care and acute care.

References

- Tupper, S.; Ward, H.; Parmar, J. Family presence in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic: Call to action for policy, practice, and research. CGJ 2020, 23, 335–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. A systematic review on the causes of the transmission and control measures of outbreaks in long-term care facilities: Back to basics of infection control. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Clostridium Difficile Infection: Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Management in Long-Term Care Facilities. PHAC. 2013. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/infectious-diseases/nosocomial-occupational-infections/clostridium-difficile-infection-prevention-control-guidance-management-long-term-care-facilities.html#a17 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Prevention and Control of Influenza During a Pandemic for All Healthcare Settings. PHAC. 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/migration/phac-aspc/cpip-pclcpi/assets/pdf/ann-f-eng.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Routine Practices and Additional Precautions for Preventing the Transmission of Infection in Healthcare Settings. PHAC. 2017. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/routine-practices-precautions-healthcare-associated-infections/part-b.html#B (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Smith, L.; Medves, J.; Harrison, M.B.; Tranmer, J.; Waytuck, B. The impact of hospital visiting hour policies on pediatric and adult patients and their visitors. JBI Libr. Syst. Rev. 2009, 7, 38–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sizoo, E.M.; Monnier, A.A.; Bloemen, M.; Hertogh, C.M.P.M.; Smalbrugge, M. Dilemmas with restrictive visiting policies in Dutch nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis of an open-ended questionnaire with elderly care physicians. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.D.; Rhinehart, E.; Jackson, M.; Chiarello, L. 2007 guideline for isolation precautions: Preventing transmission of infectious agents in health care settings. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2023, 35, S65–S164. [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooks, C.; Ewa, V.; Keefe, J.; Straus, S. The predictable crisis of COVID-19 in Canada’s long-term care homes. BMJ 2023, 382, e075148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iyamu, I.; Plottel, L.; Snow, M.E.; Zhang, W.; Havaei, F.; Puyat, J.; Sawatzky, R.; Salmon, A. Culture change in long-term care-post COVID-19: Adapting to a new reality using established ideas and systems. Can. J. Aging. 2022, 42, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Mansfield, J.; Meschiany, G. Direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on long-term care residents and their family members. Gerontology 2022, 68, 808–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, C.; Yee, A.; Stamatopoulos, V. “It’s the worst thing I’ve ever been put through in my life”: The trauma experienced by essential family caregivers of loved ones in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Int. J. Qual. Health Well. 2022, 17, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keefe, J.M.; Cranley, L.; Berta, W.B.; Taylor, D.; Beacom, A.M.; McAfee, E.; MacEachern, L.E.; Boudreau, D.; Hall, J.; Thompson, G.; et al. Role of policy in best practice dissemination: Informal professional advice networks in Canadian long-term care. CJA 2021, 40, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, F.M.; Ong, L.T.; Seavy, D.; Medina, D.; Correa, A.; Starke, J.R. Tuberculosis Among Adult Visitors of Children with Suspected Tuberculosis and Employees at a Children’s Hospital. Infect. Control. Hosp Epidemiol. 2002, 23, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sfeir, M.; Simon, M.S.; Banach, D. Isolation precautions for visitors to healthcare settings. Infect. Prev. 2017, 10, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons, C.; Durepos, P.; Taylor, N.; Keeping-Burke, L.; Rogers, M.W.; Furlong, K.E.; McCloskey, R.M. Knowledge and skills in infection prevention and control measures amongst visitors to long-term care homes: A mixed methods study. Nurs. Res. Rev. 2024, 2024, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, G.; Lee, S.; Park, Y. Effectiveness and core components of infection prevention and control programmes in long-term care facilities: A systematic review. J. Hosp Infect. 2019, 102, 377–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, R.; Durepos, P.; Gibbons, C.; Morris, P.; Witherspoon, R.; Taylor, N.; Keeping-Burke, L.; McCloskey, R. Education and training for infection prevention and control provided by long-term care homes to family caregivers: A scoping review protocol. JBI Evid. 2023, 21, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; 2020 ed.; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Australia, 2021; pp. 406–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Disease Control. Prevention and Control of Tuberculosis in Facilities Providing Long-Term Care to the Elderly. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for Elimination of Tuberculosis. In CDC; 1990. Available online: https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/prevguid/p0000185/P0000185.asp (accessed on 9 July 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. Visitation Guidelines for Residential Aged Care Facilities; Australian Government: Canberra, Australia, 2021.

- Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services. Infection Control Guidelines for Long Term Care Facilities. Missouri; 2005. Available online: https://health.mo.gov/seniors/nursinghomes/pdf/Infection_Control_Guidelines.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Provincial Infection Control Network of British Columbia. Residential Care Infection Prevention and Control Manual: For Non-Affiliated Residential Care Facilities; PICNet: Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser Health. Infection Control Manual—Residential Care. Fraser Health. 2013. Available online: https://www.fraserhealth.ca/-/media/Project/FraserHealth/FraserHealth/Health-Topics/Long-term-care-licensing/Clinical-and-Safety-Information/IC2-0400-Resident-Education-2013.pdf?rev=a940bc6dd95744ce8011753dedbcba3 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Ontario Ministry of Long-Term Care. Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) Program Guidance. Ont Min LTC. 2021. Available online: https://hpepublichealth.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/20210114-Ministry-of-Long-Term-Care-Infection-prevention-and-control-IPAC-January-2021.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Infection Prevention and Control for COVID-19: Interim Guidance for Long-Term Care Homes. PHAC. 2021. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/prevent-control-covid-19-long-term-care-homes.html#a10 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC’s Core Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Safe Healthcare Delivery in All Settings. CDC; 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/infection-control/hcp/core-practices/index.html (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. CDC; 2023. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/114001/cdc_114001_DS1.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control Guidance for Long-Term Care Facilities in the Context of COVID-19 Update. WHO. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC_long_term_care-2021.1 (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- ResCare Community Living. Patient & Family Education Package. BrightSpring Health Services: ResCare Com Liv. 2023. Available online: https://www.brightspringhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/Family-Education-Packet12-3-20.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Agency for Integrated Care. Caregiver Training Course Summary. AIC. 2023. Available online: https://www.aic.sg/caregiving/caregiver-training-course/Documents/PN_Caregiver%20Training%20Course.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Centres for Learning Research & Innovation in Long-Term Care. New IPAC eLearning Course Released. CLRI. 2023. Available online: https://clri-ltc.ca/2023/04/new-ipac-elearning-course-released/ (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Australian Government. Visiting an Aged Care Home During an Outbreak: Key Things to Remember for Partners in Care. Australian Government; 2023. Available online: https://www.agedcarequality.gov.au/sites/default/files/media/visiting-an-aged-care-home-during-an-outbreak-poster.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- American Health Care Association. Sample Policy for Emergent Infectious Diseases for Skilled Nursing Care Centers. Washington: AHCA. 2015. Available online: https://www.ahcancal.org/Survey-Regulatory-Legal/Emergency-Preparedness/Documents/EID_Sample_Policy.pdf#search=sample%20policy%20emergent%20infectious (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- UniversalCare. Pandemic, Epidemic & Outbreak Policy. Univ Care. 2022. Available online: https://villamarconi.com/sites/villamarconi.com/files/villa/villa_marconi_pandemic_epidemic_outbreak_plan.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Ontario Public Health. Visitor Policy Long Term Care Homes During COVID-19 Pandemic; Ontario Public Health: Toronto, ON, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2013—Healthcare-Associated Infections—Due Diligence. PHAC. 2013. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/chief-public-health-officer-report-on-state-public-health-canada-2013-infectious-disease-never-ending-threat/healthcare-associated-infections-due-diligence.html (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Augustin, A.; Barry, C. Position Statement: Infection prevention and control program components for long-term care homes. CJIC 2021, 36, 125–128. [Google Scholar]

- Ontario Health. Infection Prevention and Control (IPAC) Standard for Long-Term Care Homes. Ont Health. 2022. Available online: https://ltchomes.net/LTCHPORTAL/Content/12.%20IPAC%20Standard%20-%20EN.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Stefanacci, R. Drawing from the CDC for the four S’s for safer LTC visitations. Car. Ages 2020, 21, 16–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, C.; Stall, N.M.; Haimowitz, D.; Aronson, L.; Lynn, J.; Steinberg, K.; Wasserman, M. Recommendations for welcoming back nursing home visitors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a delphi panel. JAMDA 2020, 21, 1759–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control During Health Care When Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Is Suspected or Confirmed. WHO. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-IPC-2021.1 (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Infection Prevention Control Canada Definition of an, I.C.P. Infection Prevention and Control Canada. Available online: https://ipac-canada.org/definition-of-an-icp (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Benson, S.; Powers, J. Your role in infection prevention. Nurs. Made Incred. Easy. 2011, 9, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creech, A.; Hallam, S. Critical geragogy: A framework for facilitating older learners in community music. Lond. Rev. Educ. 2015, 13, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Public Health Milestones Through the Years. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/campaigns/75-years-of-improving-public-health/milestones#year-1945 (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Bolcato, M.; Aurilio, M.T.; Di Mizio, G.; Piccioni, A.; Feola, A.; Bonsignore, A.; Tettamanti, C.; Ciliberti, R.; Rodriguez, D.; Aprile, A. The difficult balance between ensuring the right of nursing home residents to communication and their safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascini, F.; Pantovic, A.; Al-Ajlouni, Y.; Failla, G.; Ricciardi, W. Attitudes, acceptance and hesitancy among the general population worldwide to receive the COVID-19 vaccines and their contributing factors: A systematic review. Clin. Med. 2021, 40, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).