Abstract

Zingeria biebersteiniana, a grass species with the lowest known chromosome number among angiosperms (2n = 2x = 4), offers a distinctive platform for cytogenetic and grass research. Despite its unique karyotype and potential for molecular and educational applications, no transformation system has previously been reported for this species. Here, we establish a reproducible Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation protocol for Z. biebersteiniana, optimized through comparative evaluation of three tissue culture media. A modified Khromov medium with Plant Preservative Mixture supported robust callus induction and plant regeneration, enabling the successful introduction of a GFP–mouse talin1 fusion construct driven by the rice Actin-1 promoter. Transgenic lines were validated via PCR amplification of the hygromycin resistance gene, and GFP signals were observed in transformed individuals. However, the expression pattern was less specific than previously reported in rice, potentially due to species-specific differences in mouse Talin1 protein localization. Although actin filament visualization in mature pollen remained unspecific, the protocol provides a foundational tool for future molecular and functional genomics and genetics studies. This work represents the first documented genetic transformation of Z. biebersteiniana, expanding its utility as a model system in plant biology and genomics.

1. Introduction

The genome organization of Zingeria biebersteiniana makes it a potential model system to study gene functions, homologous recombination, and evolution of grasses, including cereal crops, and to be applied in classrooms for genetics and biology education. The nuclear genome of Zingeria biebersteiniana, a grass species, along with Colpodium versicolor, Ornithogalum tenuifolium, Rhynchospora tenuis, and the dicotyledons Haplopappus gracilis and Brachyscome dichromosomatica, are the only plant species known to have the lowest chromosome count, with 2 pairs of chromosomes (n = 2) identified among angiosperms [1,2,3]. The chromosome size of Z. biebersteiniana is relatively large at 4–6 µm during mitotic metaphase, and its C value was estimated at 1.90 pg [4]. With the use of chemical and fluorescent dyes, chromosomes can be distinguished through all mitotic stages [5]. The combination of a large size, ease of identification, and reduced chromosome count makes Z. biebersteiniana a unique candidate as a model species for grass studies and cytogenetic work [6,7]. Establishing a protocol to transform Z. biebersteiniana is an important approach for genetic and molecular studies while using it as a model system.

The innate ability to regenerate an entire individual from a single cell, known as totipotency, is a characteristic that offers immense opportunities for research, breeding, and conservation. With the ability to produce undifferentiated cells from differentiated cells, in this case, callus can act as a medium in which genetic material can be altered and proliferated. Plants that are recalcitrant toward more efficient methods of transformation are often capable of undergoing callus induction, offering a more adaptable and accessible route for genetic engineering.

Z. biebersteiniana was first demonstrated to successfully undergo callus induction and regeneration by Petrova et al. (1992) [8]. And the regeneration rate was significantly improved recently by Khromov and Yu Cherednichenko [9] and by Twardovska & Kunakh [10]. In this study, combinations of various media and callus induction methods were used to minimize issues typically found in vitro while optimizing callus proliferation. The transition of focus towards transformation was conducted after healthy callus and its regeneration had been established.

To establish the transformation method, we used a plasmid that was a gift from Prof. Shi-Xiong Xu at the University of Hong Kong. That plasmid was designed to facilitate the visualization of actin microfilaments within immature pollen, root epidermis, and root hair cells [11], which was tested with success in rice. The construct used a rice actin-1 promoter that drives the expression of GFP fused with mouse talin (OsActin1p::GFP-mTn) [11]. The mouse talin used in this construct includes only the C-terminal F-actin-binding domain, rather than the full-length protein. In addition to rice, GFP-mTn has previously also succeeded in visualizing actin microfilaments in Arabidopsis and tobacco [12]. The Agrobacterium strain C58 was chosen as a vector to deliver the GFP-mTn construct in transformation. Here, we report the successful transformation of Z. biebersteiniana, which was validated by genotyping and phenotypic analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

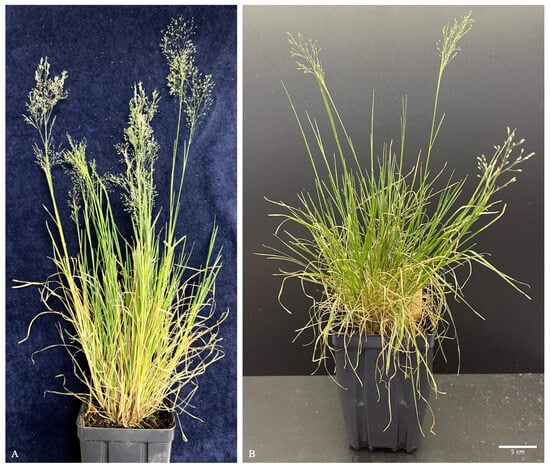

Germplasm of Zingeria biebersteiniana was initially obtained from the USDA-ARS Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN), station W6, under accession number 19209. The germplasm was propagated in a greenhouse prior to experimentation (Figure 1A). Plants and regeneration were carried out in controlled growth chambers under a light intensity of 500–600 µmol·m−2·s−1 (PPFD), with a photoperiod of 16 h light and 8 h dark, relative humidity maintained at 60–70%, and temperatures set to 22 °C during the day and 20 °C at night.

Figure 1.

Z. biebersteiniana plants. (A) Wild-type Z. biebersteiniana with inflorescences; (B) Regenerated Z. biebersteiniana with inflorescences (bar = 5 cm).

2.2. Regeneration Media and Tissue Culture

Three media formulations were used for regeneration and transformation experiments (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cultural media used for Z. biebersteiniana regeneration and transformation.

The original Petrova medium was used to conduct regeneration experiments. It consisted of agarose (10 g/L), Murashige and Skoog basal medium (MS, 1.33 g/L), sucrose (30 g/L), and casein hydrolysate (10 g/L) [8]. The phytohormones included 2,4-D (2.2 mg/L) and 6-BAP (0.56 mg/L) (Table 1) [8].

We modified the Petrova medium by replacing casein hydrolysate with Plant Cell Technology’s plant preservative mixture (PPM). The modified Petrova medium contained agarose (10 g/L), MS (1.33 g/L), sucrose (30 g/L), and PPM (2 mL/L; Plant Cell Technology, Washington DC, USA) [4]. The phytohormone treatment included 2,4-D at 2.2 mg/L for the first 7 days, followed by 1.1 mg/L until transplantation (Table 1). Seeds were germinated, and callus proliferation was maintained under dark conditions for the first 4 weeks.

We also modified the Khromov medium, recently developed by Khromov [9]. The medium consisted of agarose (10 g/L), MS (4 g/L), sucrose (30 g/L), and PPM (2 mL/L) [9]. The phytohormone treatment included 2,4-D at 4 mg/L for the first 14 days, 0.4 mg/L until regeneration began, and 0.04 mg/L thereafter (Table 1) [9]. Seeds were cold- and dark-stratified on the medium, removed from 4 °C after 4 days, and transferred to light conditions after 4 weeks [9]. For transformation experiments, the media were supplemented with hygromycin (50 mg/L) and cefoxitin (200 mg/L).

Seeds were sterilized in a 1:1 solution of 70% ethanol and hydrogen peroxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA, #516813-500 mL) for 3 min, followed by rinsing with sterile deionized water [9,10]. Sterilized seeds were placed on a sterile paper towel prior to plating on medium containing 2,4-D at 4 mg/L. After plating, the plates were sealed with micropore tape (3M, St. Paul, MN, USA), wrapped in aluminum foil, and stored at 4 °C for 4 days (Figure 2).

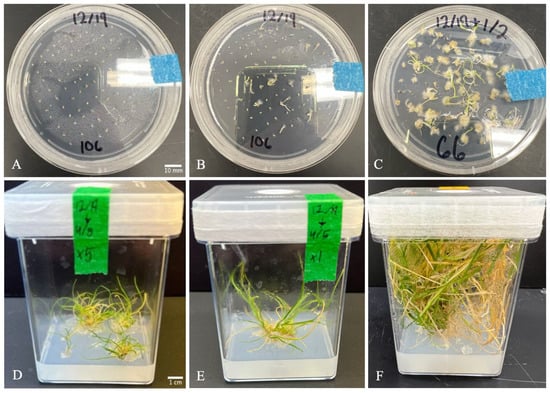

Figure 2.

Z. biebersteiniana regeneration through tissue culture in modified Khromov medium. (A) Seeds on day 1 of being plated (bar = 1 cm); (B) 1 week of growth; (C) 2 weeks of growth; (D,E) 4 months of growth (bar = 1 cm); (F) 6 months of growth.

Following stratification, plates were transferred to a 22 °C growth chamber with a 16/8 h light/dark cycle. After 14 days, seeds and germinated seedlings were moved to fresh medium with a reduced 2,4-D concentration of 0.4 mg/L, which was maintained until regeneration began (Figure 2). At three weeks, shoots, roots, and seed coats were excised, leaving only callus tissue on the medium. After 4 weeks, the aluminum foil was removed, and callus was cultured under direct light. Once regenerated shoots/leaves appeared, the 2,4-D concentration was reduced further to 0.04 mg/L.

At 8–12 weeks, when leaves reached 2–3 cm in length, regenerated plantlets were transferred to culture jars. Healthy shoots and roots were typically observed at 20–24 weeks (Figure 2). Shoots were carefully separated from the shoot mass using forceps and transferred to fresh medium to avoid damaging new growth. Once a well-developed root system was established, regenerated plants were transplanted to soil. Transplanted seedlings were maintained under a humidome for one week, with vent holes gradually opened each day to acclimate plants to ambient humidity.

2.3. Agrobacterium-Mediated Transformation

The plasmid (A005, pActin1::GFP-mTn) used for transformation was obtained from Shi-Xiong Xu’s laboratory at the University of Hong Kong and introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 [11]. The transformed Agrobacterium was cultured on LB medium (25 g/L) supplemented with kanamycin (50 mg/L) at 28 °C for 24 h, then stored at 4 °C. Strains were validated and replated onto fresh selective media every four weeks to maintain viability.

To prepare the Agrobacterium culture, 2–3 colonies were inoculated into 5 mL of LB broth containing kanamycin (50 mg/L) and incubated at 28 °C with shaking at 100 rpm for 20 h. After incubation, 1 mL of the bacterial suspension was transferred into 20 mL of fresh LB broth with kanamycin (50 mg/L) and incubated under the same conditions for an additional 8 h. The resulting culture was adjusted to an optical density (OD600) of 0.6–0.8, then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 25 mL of sterilized water containing 50 mg of Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal salts (0.5× MS broth).

Calli were immersed in the Agrobacterium suspension for 1 min, then blotted dry using sterilized paper towels to remove excess liquid. The calli were subsequently transferred to coculture medium (MS agar plates) and incubated in the dark at 22 °C for 2 days according to previous Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. After coculture, calli were transferred to selection medium containing hygromycin (50 mg/L) and cefoxitin (200 mg/L).

To enhance selection stringency, a selection wash (broth) was applied during each replating step. Calli were immersed in the wash for 1 min, blotted dry, and then placed onto fresh selection medium.

Fresh selection medium (MS agar plates) was prepared biweekly. Calli and developing plantlets were transferred to 10 cm Petri dishes containing selection medium and maintained until plantlets reached approximately 1 cm in height, exhibiting standard post-coculture development. Once plantlets reached ~1 cm, they were transferred to culture jars containing selection medium and grown until root formation was observed.

2.4. Transplanting and Genotyping

Once selected plantlets developed roots, they were transplanted into soil pots. From acclimated plants, ~200 mg of leaf tissue was collected, frozen at −70 °C, and homogenized in liquid nitrogen. The powder was suspended in 1 mL CTAB buffer, incubated at 60 °C for 30 min, and treated with RNase A. After chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (24:1) extraction, DNA was precipitated with ice-cold isopropanol, washed with 70% ethanol, and resuspended in TE buffer for storage at −70 °C or direct use in genotyping [8,13].

For Agrobacterium DNA isolation, 2–3 colonies were suspended in 100 µL of molecular-grade water for 10 min, diluted, vortexed, and centrifuged; the supernatant was stored at −70 °C or used as a positive control template [14].

Genotyping targeted the hygromycin resistance gene (HPT) using the following oligonucleotide primers: Forward: 5′-CTACAAAGATCGTTATGTTTATCGGCA-3′, Reverse: 5′-AGACCAATGGGGAGCATATAGG-3′ [11]. The PCR master mix consisted of 2 µL of 10× buffer, 2 µL of 2 mM dNTPs, 5 µL of 2 µM forward primer, 5 µL of 2 µM reverse primer, 1 unit/µL of Taq polymerase, 4 µL of molecular-grade water, and 1 µL of template DNA [15].

PCR amplification was performed using the following thermal cycling conditions: Initial denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, 35 cycles of: Denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s; Annealing at 56 °C for 40 s; Extension at 72 °C for 2 min. Final extension at 72 °C for 10 min [15].

Gel electrophoresis was used to visualize DNA extracted and PCR-amplified products. The gel was prepared with 1× TAE buffer (50 mL), agarose (0.5 g), and ethidium bromide (4 µL). Wells were loaded with either 6 µL of genomic DNA or 9 µL of PCR product.

2.5. Phenotypic Analysis

Anthers were collected once spikelets began to open, with both closed and opened spikelets harvested from the same inflorescence. Anthers were dissected and placed directly into two drops of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) on a microscope slide [5]. Using a hypodermic needle, anthers were cut and gently pressed while submerged. After processing all anthers, debris was removed, leaving only suspended pollen grains on the slide. A coverslip was then applied, and pollen was analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse Ni-E microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA) equipped with a GFP filter and the Iris 15 imaging system.

2.6. Computational Analysis of Actin1/Talin 1 Proteins

The Zingeria biebersteiniana actin1 sequence was identified using the Oryza sativa actin1 gene as a query against the Zingeria genome via Sequence Server 2.0.0 (BLASTN 2.12.0+) [16]. Genomic coordinates of the single hit were extracted with bedtools getfasta, and the sequence was analyzed for open reading frames. The longest ORF (ORF9; 666 nt/221 aa) was selected and subjected to BLASTP. Predicted protein sequences of ZbActin1, OsActin1 (GeneID: 4338914), and mouse Talin1 (GeneID: 21894) were modeled using SWISS-MODEL (EXPASY), and models were chosen based on GMQE values [17]. Structural superimposition was performed in ChimeraX using Matchmaker to compare ZbActin1–OsActin1, ZbActin1–MmTalin1, and OsActin1–MmTalin1 [18]. To evaluate potential interactions, AlphaFold2 (ColabFold v1.5.5, MMseqs2) was used for heterodimer modeling of these protein pairs, with confidence assessed by pLDDT and predicted aligned error (pAE) [19].

3. Results and Discussion

By comparing three different media formulations for tissue culture-based regeneration, we found that regeneration efficiency varies significantly (Table 2). The Modified Khromov medium showed a higher callus formation rate, with 27 out of 57 germinated seeds producing callus, and 11 of them regenerated plants (Table 2).

Table 2.

Z. biebersteiniana regeneration and transformation efficiency across three media.

Petrova medium successfully induced callus formation and direct regeneration within four weeks. However, calli and regenerated plants cultured on Petrova medium exhibited several undesirable traits (Figure 3). These included elevated contamination rates, small and darkened callus morphology, abnormal shoot and leaf phenotypes characterized by tightly curled structures, and a shortened callus proliferation window prior to regeneration.

Figure 3.

Callus at 2–3 weeks cultured in modified Petrova medium, before cutting shoot and root tissue. (A,C) Typical callus growth. (B) Unhealthy callus (bar = 1 mm). (D) Two individuals, with the individual on the left displaying hairy root callus and the individual on the right displaying typical growth.

Previously, a casein hydrolysate-containing medium, 523, consisting of 10 g/L sucrose, 8 g/L casein hydrolysate, 4 g/L yeast extract, 2 g/L KH2PO4, and 0.15 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, was developed and used to distinguish the explants by showing bacterial growth when streaked on 523 medium. This screening method demonstrates explants contaminated with bacteria, which can then be removed at the earlier steps [20]. To address the contamination issue, casein hydrolysate was removed from the formulation, and Plant Preservative Mixture (PPM) was introduced. This adjustment aligns with improvements reported in a recent regeneration protocol [9]. Casein hydrolysate consistently precipitated following autoclave sterilization, rendering the available stock unreliable and unsuitable for continued use. Its removal, combined with the addition of PPM, a proprietary broad-spectrum biocide, led to a marked reduction in contamination across cultures.

The small and darkened appearance of calli grown on Petrova medium raised concerns for subsequent transformation efforts. This phenotype, often accompanied by tissue degradation, was attributed to prolonged exposure to high concentrations of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D). To mitigate this, the concentration of 2,4-D was reduced from 2.2 g/L to 1.1 g/L on day 7 of germination. Cultures were maintained in darkness for 4 weeks prior to light exposure, which promoted callus expansion and the emergence of hairy root-like structures—likely influenced by the small seed size and low seed weight (0.2728 mg per 1000 seeds; Figure 3).

The abnormal phenotype observed in regenerated individuals was suspected to result from exposure to 6-benzylaminopurine (6-BAP) in the medium (Figure 3). Exclusion of 6-BAP from subsequent formulations led to regenerated plants with morphology more consistent with soil-grown individuals. Despite these improvements, the limited callus proliferation period remained unresolved. Once callus formation was initiated, the working window before spontaneous regeneration consistently ranged from 3 to 5 weeks, posing challenges for downstream transformation and regeneration control. The shorter callus proliferation windows than typical monocots are caused by its physiological characteristics, mainly because its seeds/embryos are very small with limited nutrient reserves, which cause its callus to differentiate quickly.

These alterations to the original Petrova medium led to the development of a modified formulation, which became the predominant medium used during the early stages of this study. However, following the publication of work by Khromov and Yu Cherednichenko [9], use of the modified Petrova medium was discontinued. The Khromov medium introduced several key changes: an increased MS concentration (4 g/L), a cold stratification step of 4 days at 4 °C, and a revised 2,4-D regimen beginning with 4 mg/L for the first 14 days, followed by 0.4 mg/L. A third concentration of 0.04 mg/L was later added after regeneration commenced. This modified Khromov medium produced pale white to yellow calli that were notably larger than those generated on other media (Figure 3), and it subsequently became the preferred medium for callus induction and the default for transformation experiments (Figure 2).

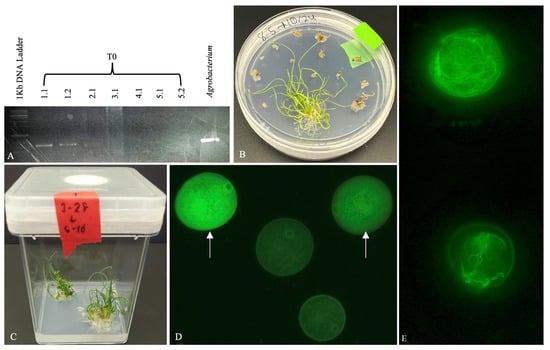

Transformation efforts yielded five potential transgenic lines, which were propagated into a total of 14 plants. Of these, two individuals were confirmed by PCR genotyping to carry the hygromycin phosphotransferase (HPT) gene (Figure 4). Seeds were successfully harvested from both verified transgenic individuals following senescence.

Figure 4.

Validation of transformants. (A) PCR confirmation of the HPT gene in individual transgenic lines; each whole number denotes a distinct line. Agrobacterium carries OsActin1p::GFP:mTn is included as the positive control. (B,C) Regenerated plantlets growing on selection medium. (D) Pollen grains (haploid) from T0 line 1.1 showing differential GFP expression: approximately half exhibit less or non-specific GFP localization (indicated by arrows), while the other half lack GFP signal, suggesting a heterozygous transformation event in line 1.1. (E) Wild-type control pollen grains stained with Phalloidin-iFluor 488 (Abcam, ab176753) exhibit distinct actin filament structures.

Building on Shi-Xiong Xu’s work in rice, immature pollen from potentially transformed lines of Zingeria biebersteiniana was screened for fluorescence-associated pollen development. In validated T0 transgenic lines, pollen was available for analysis. Approximately half of the haploid pollen grains exhibited GFP fluorescence; however, the signal was not specifically associated with the Actin1 protein. Instead, GFP localization appeared diffuse and non-specific, similar to patterns of OsActin1p::GFP without mouse Talin1 that was previously observed in rice, and actin microfilaments did not exhibit the expected GFP expression in pollen (Figure 4D). As a result, distinct actin microfilament structures were not visualized in the transgenic lines displaying GFP signal with the expression of OsActin1p::GFP:mTn. Wild-type pollen grains stained with phalloidin revealed the presence of actin microfilaments within the pollen (Figure 4E).

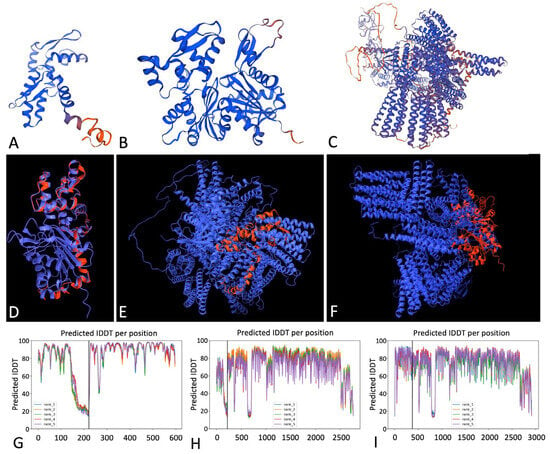

To investigate the lack of specific GFP labeling of Zingeria actin microfilaments using the OsActin1p::GFP:mTn construct, we compared the predicted 3D structures of ZbActin1, OsActin1, and mouse Talin-1 using AlphaFold2 [19] (Figure 5). Structural superimposition [18] and heterodimer modeling [17] were employed to assess homology and potential interactions between ZbActin1 and mouse Talin1, as well as OsActin1 and mouse Talin1. The Zingeria biebersteiniana actin1 sequence was identified on Chromosome 1 with 86.1% identity to rice actin1, and the longest ORF (666 nt/221 aa) showed 89.99% identity to Oryza sativa actin-2. Structural modeling yielded GMQE values of 0.73 (ZbActin1), 0.95 (OsActin1), and 0.77 (MmTalin1). ChimeraX superimposition demonstrated strong conservation between ZbActin1 and OsActin1 (alignment score 808.8; RMSD 0.383 Å), while comparisons with mouse Talin1 revealed only small local motifs and poor global alignment. AlphaFold2 heterodimer modeling predicted high confidence for ZbActin1–OsActin1 complexes (pLDDT > 90, reliable folds), whereas Talin1 showed mixed confidence (70–90, with flexible regions <50), resulting in moderate reliability for actin–Talin1 complexes. Overall, ZbActin1 and OsActin1 share a highly conserved core fold, while Talin1 exhibits only partial structural compatibility. The analysis revealed notable structural differences among the three proteins, which may explain why GFP fused to mouse Talin1 successfully visualizes OsActin1 microfilaments in rice but fails to do so with ZbActin1 in Zingeria. The diffuse GFP signal in pollen might be attributed to partial protein misfolding, not due to lack of actin-binding affinity between ZbActin1 and Mouse Talin1.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of species-specific Actin1/Talin1 proteins using structural modeling and alignment [17,18,19]. (A–C) Predicted 3D structures of ZbActin1 (A), OsActin1 (B), and Mouse Talin1 (MmTalin1) (C), generated using SWISS-MODEL via the EXPASY server. (D–F) Structural superimposition of monomers: ZbActin1 (red) overlaid on OsActin1 (blue) (D), ZbActin1 on mouse Talin1 (blue) (E), and OsActin1 (red) on mouse Talin1 (blue) (F). (G–I) confidence and alignment metrics from alphafold2: predicted local distance difference test (PLDDT) and predicted aligned error (PAE) for ZbActin1 vs. OsActin1 (G), ZbActin1 vs. mouse Talin1 (H), and OsActin1 vs. mouse Talin1 (I). in each panel, the left and right sides of the chart correspond to the respective proteins being compared.

Despite this limitation, a distinctive pollen phenotype was consistently observed in transformed Z. biebersteiniana. Mature pollen exhibited a non-specific GFP signal pattern, differing from the expected microfilament-associated fluorescence (Figure 4). This observation supports that the OsActin1 promoter effectively drives GFP expression during corresponding developmental stages in Zingeria, as it does in rice. Although the GFP signal did not mark actin structures, the unique pollen morphology may serve as a useful visual marker for transformation in future studies, pending further validation using a construct such as ZbActin1p::GFP:ZbActin1, GFP fused with the native Zingeria Actin1.

Although the desired phenotype was not observed, the transformed Zingeria biebersteiniana plants were successfully seeded. The resulting T1 generation may enable homologous transformation of the OsActin1p::GFP:mTn construct, increasing the likelihood of visualizing actin microfilaments. Furthermore, future investigations using ZbActin1p::GFP:ZbActin1 expression in Zingeria could help establish a reliable system for visualizing microfilament dynamics during pollen development and cell division. This transformation marks the first known successful protocol for Z. biebersteiniana, providing a valuable foundation for advancing our understanding of this unique species, particularly its chromosome behavior and cytoskeletal organization.

4. Future Perspectives

Building on the successful transformation of Zingeria biebersteiniana, the following directions offer promising avenues to expand its genomic toolkit and deepen biological understanding: (1) deployment of ZbActin1p::GFP:ZbActin1 for high-resolution, species-specific visualization of actin filaments and dynamic cytoskeletal remodeling in living cells; (2) application of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing to dissect recombination mechanisms and structural variation within the paracentric regions of Zingeria chromosomes; and (3) implementation of promoter–reporter assays to unravel the regulatory architecture governing chromosome dynamics and cytoskeletal organization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and R.K.; methodology, C.C. and R.K.; validation, C.C., R.K. and C.J.R.; formal analysis, R.K. and S.H.S.; investigation, R.K. and S.H.S.; resources, C.C.; data curation, R.K. and C.J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.K.; writing—review and editing, C.C., R.K., S.H.S. and C.J.R.; visualization, C.C., S.H.S. and R.K.; supervision, C.C.; project administration, C.C.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed in this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Lu Yin, Tania Hernandez, Kathleen Pigg, and three reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank Elisabeth Burnquist for her dedicated technical support. This work was supported by faculty startup funding from Arizona State University awarded to C.C., and by the SOLS MS graduate assistantship awarded to R.K.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bennett, M.D.; Smith, J.B.; Seal, A.G. The karyotype of the grass Zingeria biebersteiniana (2n = 4) by light and electron microscopy. Can. J. Genet. Cytol. 1986, 28, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiglione, M.R.; Cremonini, R. A fascinating island: 2n = 4. Plant Biosyst. 2012, 146, 711–726. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S.; Bolsheva, N.L.; Samatadze, T.E.; Nosov, N.N.; Nosova, I.V.; Zelemin, A.V.; Punina, E.O.; Muravenko, O.V.; Rodionov, A.V. The unique genome of two-chromosome grasses Zingeria and Colpodium, its origin, and evolution. Russ. J. Genet. 2009, 45, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.D.; Smith, J.B. Nuclear DNA amounts in angiosperms. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 1991, 334, 309–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.T.; Leitch, I.J.; Bennett, M.D. Chromosome identification and mapping in the grass Zingeria biebersteiniana (2n = 4) using fluorochromes. Chromosome Res. 1995, 3, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotseruba, V.; Gernand, D.; Meister, A.; Houben, A. Uniparental loss of ribosomal DNA in the allotetrapoid grass Zingeria trichopoda (2n = 8). Genome 2003, 46, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeth, R. Establishing Zingeria biebersteiniana (n = 2) as a Model System for Plant Biology. Master’s Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 2024. Available online: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/195318 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Petrova, T.F.; Kulinich, A.V.; Abramova, V.M.; Doklady, V.M. Use of Zingeria biebersteiniana (2n = 4) grown in vivo and in vitro as a model species for genetic studies. Biol. Sci. 1992, 319, 432–435. [Google Scholar]

- Khromov, A.V.; Cherednichenko, M.Y. In vitro culture of Zingeria biebersteiniana (Claus) P. Smirn as a method of conservation and expanding its biodiversity. IOP Conf. Series. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 981, 042070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardovska, M.O.; Kunakh, V.A. In vitro culture of Zingeria biebersteiniana (claus) p. smirn. as a method for conservation and restoration of genetic diversity. Factors Exp. Evol. Org. 2022, 30, 109–115. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Wang, L.; Qiu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Yu, X. Actin visualization in living immature pollen of rice using of GFP-mouse Talin fusion protein. Acta Botanica Sinica 2002, 44, 642. Available online: https://www.jipb.net/EN/Y2002/V44/I6/642 (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Kost, B.; Spielhofer, P.; Chua, N.-H. A GFP-mouse talin fusion protein labels plant actin filaments in vivo and visualizes the actin cytoskeleton in growing pollen tubes. Plant J. 1998, 16, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, M.G.; Thompson, W.F. Rapid isolation of high molecular weight plant DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980, 8, 4321–4326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, O.B.; Dablool, A.S. Quality improvement of the DNA extracted by boiling method in gram negative bacteria. Int. J. Bioassays 2017, 6, 5347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, E.L. Polymerase Chain Reaction Protocol; American Society for Microbiology, Microbiology Resource Library: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://asm.org/asm/media/protocol-images/polymerase-chain-reaction-protocol.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Altschul, S.F.; Madden, T.L.; Schäffer, A.A.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Miller, W.; Lipman, D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25, 3389–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; de Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W296–W303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, E.C.; Goddard, T.D.; Pettersen, E.F.; Couch, G.S.; Pearson, Z.J.; Morris, J.H.; Ferrin, T.E. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirdita, M.; Schütze, K.; Moriwaki, Y.; Heo Lim Ovchinnikov, S.; Steinegger, M. ColabFold: Making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 2022, 19, 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viss, P.R.; Brooks, E.M.; Driver, J.A. A simplified method for the control of bacterial contamination in woody plant tissue culture. In Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Plant 1991, 27, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).