Abstract

Cloud storage continues to experience recurring provider-side breaches, raising concerns about the confidentiality and recoverability of user data. This study addresses this challenge by introducing an Artificial Intelligence (AI)-driven hybrid architecture for secure, reconstruction-resistant multi-cloud storage. The system applies telemetry-guided fragmentation, where fragment sizes are dynamically predicted from real-time bandwidth, latency, memory availability and disk I/O, eliminating the predictability of fixed-size fragmentation. All payloads are compressed, encrypted with AES-128 and dispersed across independent cloud providers, while two encrypted fragments are retained within a VeraCrypt-protected local vault to enforce a distributed trust threshold that prevents cloud-only reconstruction. Synthetic telemetry was first used to evaluate model feasibility and scalability, followed by hybrid telemetry integrating real Microsoft system traces and Cisco network metrics to validate generalization under realistic variability. Across all evaluations, XGBoost and Random Forest achieved the highest predictive accuracy, while Neural Network and Linear Regression models provided moderate performance. Security validation confirmed that partial-access and cloud-only attack scenarios cannot yield reconstruction without the local vault fragments and the encryption key. These findings demonstrate that telemetry-driven adaptive fragmentation enhances predictive reliability and establishes a resilient, zero-trust framework for secure multi-cloud storage.

1. Introduction

As cloud storage becomes increasingly essential to enterprise and consumer systems, recurring provider-side breaches reveal that cloud vendors alone cannot guarantee data confidentiality. Incidents such as the MOVEit breach in 2023, the AT&T–Snowflake incident in 2024 and the unauthorized access within Oracle Cloud in 2025 show that large-scale cloud compromise remains a recurring risk [1,2,3]. These events highlight a structural vulnerability: once a cloud provider is breached, adversaries may obtain partial or complete access to cloud-resident data, and users have limited means to enforce confidentiality beyond basic encryption. This work adopts the operational assumption that cloud compromise is inevitable and that confidentiality must be preserved even when cloud fragments are exposed.

Multi-cloud adoption improves availability and reduces dependence on a single provider, but conventional approaches that replicate full files or distribute fixed-size fragments across providers introduce predictable storage patterns and expand the attack surface. Deterministic fragmentation produces repeatable fragment boundaries that can be inferred or correlated by attackers, and prior studies show that adversaries who acquire a sufficient subset of cloud fragments can reconstruct sensitive data [4,5,6]. Existing encryption, access-control and placement-policy mechanisms enhance confidentiality [7,8,9], yet they typically rely on static fragmentation rules and do not incorporate live telemetry into the fragmentation process. Work in machine learning for cloud automation has demonstrated the value of predictive analytics for anomaly detection, workload forecasting and orchestration [10,11,12,13,14,15], but these advancements do not extend predictive modeling to fragment-size selection or adaptive data dispersion.

A further limitation concerns trust boundaries. Most systems place all reconstruction fragments within cloud environments, simplifying management but increasing exposure when cloud compromise occurs. Although hybrid storage strategies have been explored [16,17], many lack enforced local participation or a reconstruction threshold that prevents provider-only recovery. This leaves users vulnerable to cloud-side breaches even when encryption is employed.

Telemetry realism presents an additional challenge. Many studies rely exclusively on synthetic datasets that lack the variability, noise and hardware dependencies present in real workloads. Research on anomaly detection, energy-aware scheduling and hybrid-cloud optimization underscores the need for realistic telemetry when validating predictive behavior [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. To address this gap, the present study integrates hybrid telemetry derived from enterprise monitoring repositories, including the Microsoft Cloud Monitoring Dataset [16] and the Cisco Telemetry Repository [17], which supply authentic system and network traces for realistic model evaluation.

This work proposes an AI-driven hybrid architecture for secure, reconstruction-resistant multi-cloud storage. The architecture is based on three security principles. First, fragmentation is adaptive rather than static. Fragment sizes are predicted from real-time bandwidth, latency, CPU utilization, memory availability and disk activity, eliminating the predictability associated with fixed-size fragmentation. Second, reconstruction requires participation from multiple trust domains. Two encrypted fragments are retained in a VeraCrypt-protected local vault, and full recovery requires cloud fragments, local fragments and the AES-128 encryption key. This prevents cloud-only or partial-access attacks from yielding meaningful reassembly. Third, the system assumes that cloud compromise is inevitable and therefore provides confidentiality by ensuring that compromised cloud fragments cannot be reconstructed or correlated. Unlike prior multi-cloud or hybrid storage approaches, this architecture integrates telemetry-driven fragment-size prediction with an enforced local reconstruction threshold, explicitly preventing cloud-only recovery even under provider compromise.

The predictive component integrates four regression models: Linear Regression, Neural Network, Random Forest and XGBoost. A two-phase dataset strategy is used. Synthetic telemetry is employed initially to evaluate model feasibility, stability and scalability under controlled conditions. Hybrid telemetry, created by aligning real Microsoft and Cisco traces with synthetic features at matched scales, is then used to validate generalization under realistic variability. This process ensures that the deployed predictive model reflects operational resource patterns rather than purely synthetic distributions.

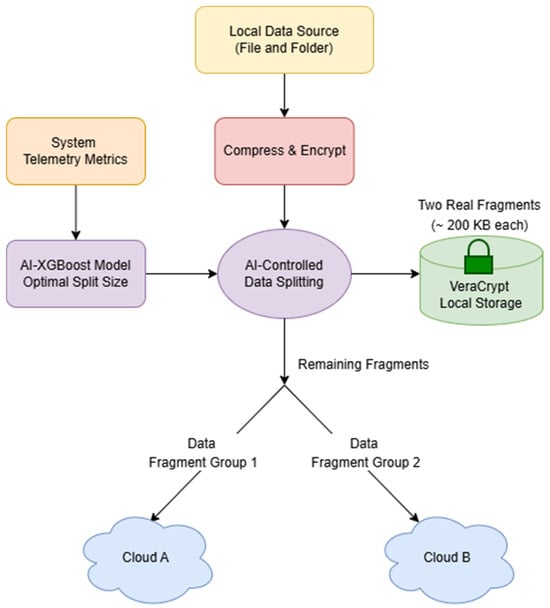

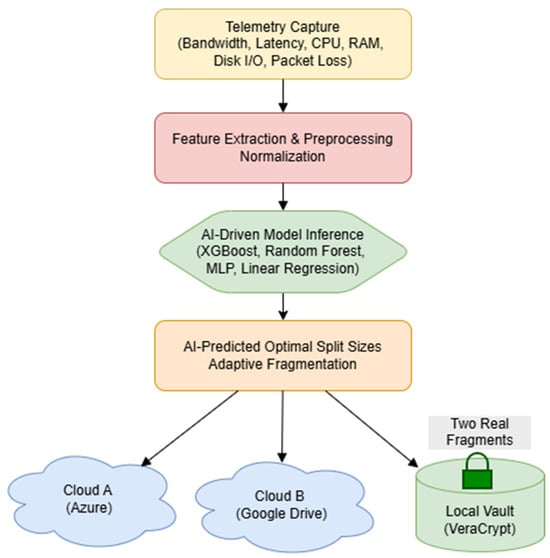

The overall architecture is summarized in Figure 1, which illustrates telemetry capture, AES-128 encryption, adaptive fragmentation, secure local retention and distribution across independent cloud providers.

Figure 1.

AI-driven hybrid storage architecture showing telemetry capture, encryption, adaptive fragmentation, local vault retention and distribution across independent cloud providers.

Adaptive fragmentation enhances both security and performance. By tailoring fragment sizes to live telemetry, the system balances upload load, reduces reconstruction exposure and strengthens confidentiality. The resulting framework increases resilience against provider compromise while demonstrating the scalability and reproducibility of telemetry-guided, AI-controlled multi-cloud data management.

The objective of this study is not to replace cryptographic primitives, but to demonstrate how AI-driven adaptive fragmentation and distributed trust can materially improve reconstruction resistance under realistic cloud-breach assumptions. To frame the security objectives, the threat model considered in this study assumes an adversary capable of compromising one or more cloud providers, acquiring unauthorized cloud-resident fragments and attempting reconstruction through structural inference, fragment correlation or other unauthorized techniques. Confidentiality is preserved through three mechanisms: dynamic, unpredictable fragmentation; a distributed reconstruction threshold requiring cloud fragments, two encrypted local fragments, and the AES-128 key; and strict integrity checks that prevent corrupted fragments from being incorporated into reassembly. Together, these mechanisms create a reconstruction-resistant model that allows users to leverage cloud services without compromising data security.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Overview

This section describes the datasets, preprocessing pipeline, feature engineering process, predictive modeling workflow, evaluation metrics, and system configuration used to implement and assess the proposed AI-driven hybrid multi-cloud storage architecture. The system integrates telemetry capture, AES-128 encryption, predictive split-size estimation, adaptive fragmentation, secure local retention, and multi-cloud distribution. Figure 2 presents the end-to-end workflow from telemetry acquisition to fragment placement across local and cloud domains.

Figure 2.

System workflow illustrating telemetry capture, AES-128 encryption, model-based split-size prediction, adaptive fragmentation, secure local retention, and multi-cloud distribution.

2.2. Datasets

Five telemetry datasets were used to train and evaluate the predictive models that support adaptive fragmentation. Four synthetic datasets containing 300, 1000, 2000, and 5000 rows were generated using seeded statistical distributions to emulate realistic operating conditions while preserving controlled variability for repeatable testing.

Hybrid datasets of matching sizes were subsequently constructed by blending synthetic feature bundles with real telemetry streams obtained from the Microsoft Cloud Monitoring Dataset [16] and the Cisco Telemetry Repository [17]. Each hybrid dataset was aligned and pivoted into a consistent tabular schema that retains the same five primary telemetry features as the synthetic datasets: upload bandwidth (Mbps), network latency (ms), CPU utilization (%), memory availability (GB), and disk activity (GB).

This structure ensures direct comparability between synthetic and hybrid datasets while preserving the heterogeneity and noise characteristics that are representative of real enterprise environments. The synthetic datasets provide controlled conditions for model feasibility and scalability analysis, and the hybrid datasets supply realistic variability for generalization testing under production-like conditions.

2.3. Pre-Processing

All datasets were preprocessed using a unified pipeline. Table 1 summarizes dataset composition, feature sets, and intended purposes for both synthetic and hybrid datasets.

Table 1.

Summarizes dataset composition, feature sets, and purposes.

All datasets underwent the following preprocessing steps:

- Missing-value imputation: feature-wise median imputation was applied to replace missing values.

- Feature scaling: normalization was applied to stabilize model behavior under heterogeneous telemetry ranges, consistent with prior findings on scaling effectiveness for regression models [26].

- Schema validation: feature order, naming, and formatting were verified to be identical across all synthetic and hybrid datasets.

- Data type uniformity: all telemetry variables were numeric, so no categorical encoding was required.

This common preprocessing pipeline ensured that performance differences were attributable to model characteristics and dataset properties rather than to inconsistencies in data preparation.

2.4. Feature Engineering

The predictive models operate on five telemetry features that directly reflect network and system dynamics that influence fragmentation efficiency and model-guided split prediction:

- Upload bandwidth (Mbps): Real-time transfer capacity between local and cloud endpoints.

- Network latency (ms): Round-trip delay affecting upload responsiveness and queue congestion.

- CPU utilization (%): Instantaneous processor load that influences encryption and compression throughput.

- Total RAM (GB): Available memory that determines concurrent buffering capacity.

- Total disk capacity (GB): Storage subsystem capability that governs fragment write and retrieval performance.

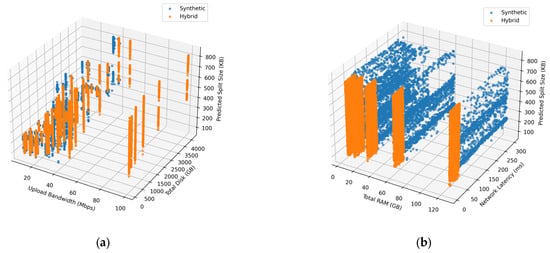

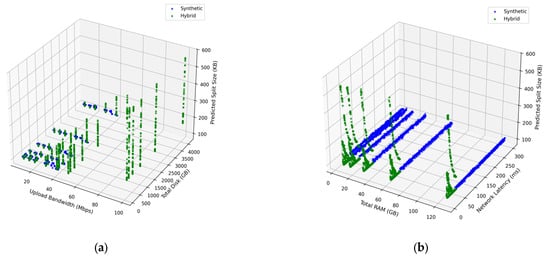

These features capture the operating conditions required for adaptive fragmentation and align with prior work showing that telemetry attributes enhance workload prediction and resource optimization accuracy [27,28,29]. Three-dimensional interaction surfaces for XGBoost and Random Forest (Figure 3a,b and Figure 4a,b) exhibit smooth, stable nonlinear behavior across synthetic and hybrid datasets, confirming consistent and reliable fragment-size predictions.

Figure 3.

XGBoost interaction surfaces showing predicted fragment size under varying telemetry conditions. (a) Upload Bandwidth and Total Disk Capacity. (b) Total RAM and Network Latency.

Figure 4.

Random Forest interaction surfaces showing predicted fragment size under varying telemetry conditions. (a) Upload Bandwidth and Total Disk Capacity. (b) Total RAM and Network Latency.

2.5. Model Development

Four supervised regression models were developed to predict optimal fragment sizes from telemetry inputs:

- Linear Regression (LR): Ordinary Least Squares baseline.

- Random Forest (RF): Ensemble of 300 decision trees.

- Neural Network (NN): Feed-forward network with 64 and 32 hidden units using ReLU activation and Adam optimizer.

- XGBoost (XGB): Gradient-boosted ensemble with 600 estimators, maximum depth 6, learning rate 0.05.

Training used the 300-row synthetic dataset (Synthetic_300) for the synthetic group and the 300-row hybrid dataset (Hybrid_300) for the hybrid group. The use of a 300-row training dataset is intended to evaluate feasibility and learning behavior under limited-data conditions representative of early-stage or resource-constrained deployments, rather than large offline training scenarios. Evaluations on the 1000-, 2000-, and 5000-row datasets measured scalability, robustness, and cross-domain generalization under increasing data volumes. Random Forest and XGBoost were selected for deeper comparison based on prior evidence of strong performance on structured telemetry and cloud prediction tasks [27,28,29]. The reported model performance comparisons are descriptive rather than inferential, and no statistical significance testing or confidence intervals are claimed. The core architectures and hyperparameter configurations of all evaluated models are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of the core configuration for each model.

2.6. Evaluation Metrics

Model accuracy was quantified using Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Coefficient of Determination (R2), standard metrics for regression analysis in telemetry-driven AI systems [27,28,29]:

MAE measures average prediction error, RMSE penalizes larger deviations more strongly and is therefore sensitive to outliers, and R2 indicates the proportion of variance in the target variable that is explained by the model. These metrics together provide a comprehensive view of accuracy, stability, and explanatory power. Because the target variable is generated deterministically from telemetry inputs, near-perfect R2 values are expected and do not indicate overfitting or target leakage.

2.7. System Configuration

The experimental environment used the following hardware and software configuration:

Hardware: HP from the USA—Intel Core i7-12700K @ 3.6 GHz, 32 GB DDR4 RAM, NVIDIA RTX 3070 GPU, 1 TB NVMe SSD. F

Software: Python 3.13 with scikit-learn and XGBoost; Tkinter/TkinterDnD for GUI; Google Drive API and Azure Blob SDK for multi-cloud operations.

Security: Two encrypted fragments (approximately 200 KB total) are stored locally in a VeraCrypt-protected vault (M:\splitFile). The retention of two local fragments represents a configurable design parameter selected to enforce a minimal reconstruction threshold while limiting local storage overhead. This design forms a mandatory local–cloud reconstruction barrier that prevents cloud-only recovery and aligns with distributed trust storage principles [30,31]. Full reconstruction requires access to cloud fragments, local fragments, and the AES-128 key. AES-128 is employed as a standardized symmetric encryption scheme offering strong security with comparatively low computational overhead, making it suitable for resource-aware, telemetry-driven architecture; alternative schemes could be substituted without altering the system design.

2.8. Ethical Statement and Use of Generative Tools

This study used public and anonymized telemetry data from Microsoft and Cisco repositories [16,17]. No human or animal subjects were involved. Generative AI tools were used solely for grammar and stylistic refinement of the manuscript text; no AI-generated data, synthetic benchmarks beyond the described synthetic datasets, or AI-generated figures were employed in the experimental evaluation. All results are based on explicitly described datasets and code.

2.9. Reproducibility and Data Availability

All datasets, scripts, and trained models will be released upon publication to support reproducibility, in accordance with MDPI policies and emerging AI reproducibility frameworks for cloud storage research [32]. The release package will include synthetic and hybrid telemetry datasets at all scales, model training and evaluation scripts, configuration files, and plotting utilities corresponding to the results presented in Section 3, Section 4 to Section 5.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Experimental Outcomes

This section presents the predictive evaluation of the AI-Controlled Multi-Cloud DataVault using synthetic and hybrid telemetry datasets. As described in Section 2, all models were trained on 300-row datasets and evaluated on larger sets of 1000, 2000, and 5000 rows to assess generalization from limited training data to broader telemetry distributions. Synthetic and hybrid evaluations were conducted separately to represent controlled and realistic operating conditions.

Across all evaluations, predictive accuracy improved as dataset size increased. Random Forest and XGBoost consistently achieved the strongest performance, Neural Network improved at larger scales but showed variability in smaller hybrid sets, and Linear Regression remained the weakest model. The following subsections detail results for each dataset type.

3.2. Model Performance on Synthetic Datasets

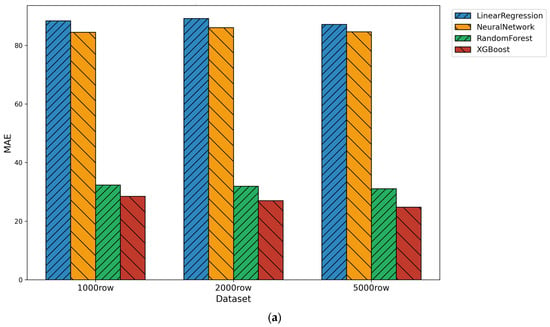

Performance across the synthetic datasets remained relatively stable as evaluation size increased from 1000 to 5000 rows. As shown in Figure 5a–c, MAE, RMSE, and R2 for all models changed only modestly across the synthetic evaluation sizes, indicating that the synthetic telemetry offered limited variability for model differentiation.

Figure 5.

(a) Mean Absolute Error (MAE) across models for synthetic datasets. (b) Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) across models for synthetic datasets. (c) Coefficient of Determination (R2) across models for synthetic datasets.

XGBoost and Random Forest achieved the strongest performance on the synthetic datasets, consistently producing the lowest MAE and RMSE values and the highest R2 across all three evaluation sizes. Linear Regression showed the weakest performance, with high MAE and RMSE and the lowest R2 values, reflecting its inability to capture the nonlinear structure of the synthetic telemetry. Neural Network performance improved slightly with larger synthetic datasets but remained less accurate than the ensemble models.

These findings suggest that the synthetic telemetry lacks the complexity and noise needed for more pronounced performance gains. Ensemble methods maintained consistent accuracy, while Linear Regression continued to struggle due to its linear modeling assumptions.

3.3. Model Performance on Hybrid Dataset

To evaluate model robustness under realistic operating conditions, performance was compared across both synthetic and hybrid telemetry. The hybrid evaluations incorporated real system variability, including fluctuations in bandwidth, latency, and resource load, which produced more pronounced performance differences than those observed in the synthetic datasets. The following comparisons are descriptive in nature and are intended to illustrate relative performance trends across models rather than to provide inferential statistical conclusions.

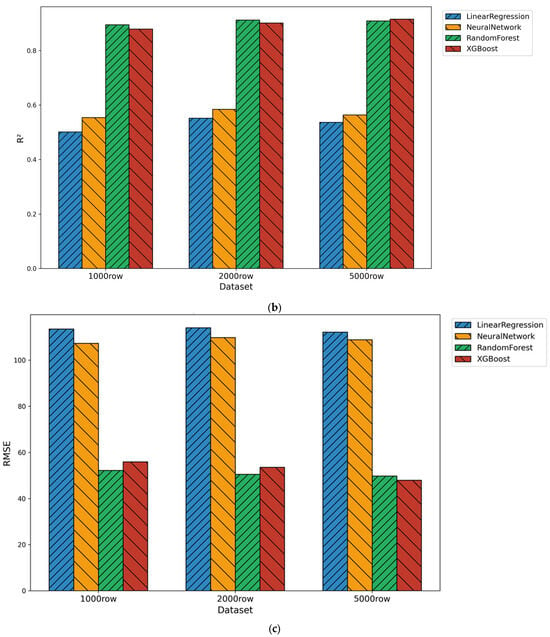

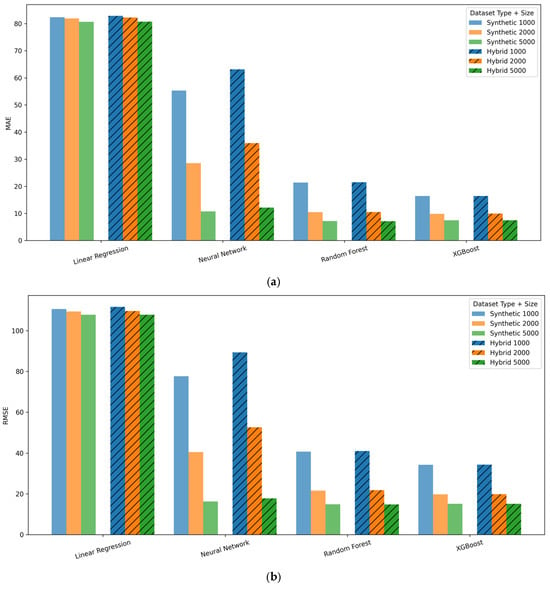

3.3.1. MAE Comparison (Figure 6a)

Hybrid MAE results show clear improvements for the nonlinear models. Random Forest and XGBoost achieve the lowest errors (≈2–3), while Neural Network also shows substantial reductions compared to its synthetic values. Linear Regression exhibits only minor improvement and remains the least accurate model.

Figure 6.

(a) Mean Absolute Error (MAE) across models for synthetic and hybrid datasets. (b) RMSE across models for synthetic and hybrid datasets. (c) Coefficient of Determination (R2) across models for synthetic and hybrid datasets.

3.3.2. RMSE Comparison (Figure 6b)

Hybrid RMSE results show strong ensemble performance, with Random Forest and XGBoost achieving RMSE values of approximately 4–5. Neural Network RMSE improves markedly compared to its synthetic values, while Linear Regression remains the least accurate model.

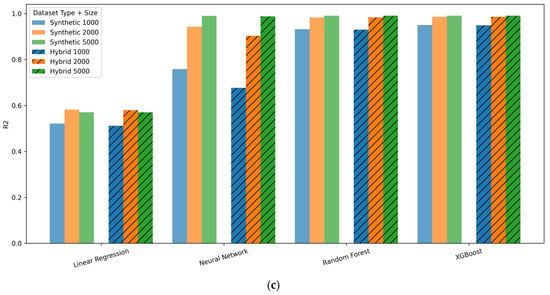

3.3.3. R2 Comparison (Figure 6c)

Hybrid R2 values approach 1.0 for Random Forest, XGBoost, and Neural Network, indicating near-perfect explanatory power. Linear Regression continues to show low R2, demonstrating its limited ability to capture real telemetry patterns. The near-perfect R2 values observed for ensemble models are expected due to the deterministic, policy-based construction of the target variable, which yields a bounded output space and does not reflect noisy or independently measured labels.

3.4. Comparative Analysis

Table 3 summarizes consolidated MAE, RMSE, and R2 results across all models and evaluation sizes. Random Forest and XGBoost consistently achieved the lowest errors and highest accuracy across both synthetic and hybrid datasets. In the hybrid evaluations, both models produced very low MAE values (approximately 2–3) and R2 values approaching 1.0, while synthetic results showed smaller but consistent advantages. Neural Network performance became competitive at larger evaluation sizes, particularly in the hybrid dataset, whereas Linear Regression consistently showed the poorest results across all conditions.

Table 3.

Consolidated MAE, RMSE, and R2 metrics for all models across synthetic and hybrid datasets.

These results confirm that ensemble learners provide the most reliable foundation for adaptive fragmentation within the DataVault architecture. Their stability under diverse telemetry conditions aligns with the requirements of secure and consistent multi-cloud storage.

Overall, the consolidated results indicate that ensemble learners offer the most reliable foundation for adaptive fragmentation under both synthetic and hybrid telemetry conditions within the evaluated telemetry regimes.

3.5. Statistical Validation and Error Analysis

Model reliability was assessed using the evaluation metrics defined in Section 2.5. Across all datasets, the ensemble models Random Forest and XGBoost exhibited the most stable error behavior, with consistently low MAE and RMSE values and R2 scores above 0.90 for synthetic data and near 1.0 for hybrid evaluations. These results indicate strong predictive accuracy and reliable convergence under diverse telemetry conditions.

Error distributions for the ensemble models showed minimal bias and limited variability between synthetic and hybrid datasets, highlighting their strong generalization capability. In contrast, Linear Regression and Neural Network displayed larger variance and occasional outliers, reflecting their sensitivity to nonlinear feature interactions and reduced robustness at smaller evaluation sizes.

Collectively, these outcomes validate the stability and reproducibility of the predictive models. The low residual error and consistent statistical behavior demonstrate that the AI-driven components of the Multi-Cloud DataVault architecture deliver reliable, data-adaptive predictions essential for effective fragmentation control. The robustness of the ensemble models ensures stable behavior even when bandwidth, latency, and system load fluctuate, reinforcing their suitability as the core predictive mechanism for secure and resilient multi-cloud operation.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Predictive Outcomes

The predictive evaluation demonstrated consistent and reliable model behavior across both synthetic and hybrid telemetry datasets. Random Forest and XGBoost maintained low error values and high determination coefficients at all evaluation sizes, indicating that these ensemble methods captured the nonlinear structure of fragmentation patterns with limited sensitivity to environmental noise. Neural Network performance improved substantially at larger dataset sizes, although its variability in the smaller hybrid evaluations suggests a greater dependence on distribution breadth. Linear Regression consistently produced the highest error values, reflecting its limited ability to represent nonlinear dependencies among bandwidth, latency, memory, and storage features. The consistently high R2 values observed for ensemble models should be interpreted in light of the deterministic, policy-based construction of the target variable, which constrains output variance and supports stable learning even under noisy telemetry inputs.

These findings align with recent studies demonstrating that ensemble models maintain strong accuracy when learning from complex and variable telemetry signals [33]. This stability is critical for the DataVault architecture, which depends on accurate predictions under fluctuating resource conditions to support adaptive, telemetry-driven fragmentation. From an interpretability perspective, ensemble decision structures indicate that bandwidth and latency features exert the strongest influence on predicted fragment size, followed by memory and storage utilization, which is consistent with system-level performance intuition.

4.2. Role of Synthetic vs. Hybrid Datasets

The complementary behavior of synthetic and hybrid evaluations highlights the importance of incorporating both controlled and realistic data sources into the predictive pipeline. Synthetic datasets enabled stable baseline assessment, while hybrid datasets introduced fluctuations in throughput, latency, and system load that more closely resemble real multi-cloud environments. Ensemble models maintained accuracy across both dataset types, confirming their robustness to heterogeneous telemetry conditions.

The improvement observed in Neural Network performance at larger evaluation sizes further supports the role of hybrid telemetry in broadening feature diversity and reducing bias. These patterns are consistent with findings in hybrid-learning research demonstrating that combining real and synthetic signals mitigates overfitting and strengthens operational reliability [34]. Together, the two dataset modalities provide a balanced and realistic framework for evaluating adaptive fragmentation mechanisms.

4.3. Implications for Adaptive Fragmentation

The predictive results confirm the practical value of telemetry-guided adaptation for fragment-size regulation. Ensemble learners consistently adjusted fragment size according to observed bandwidth and system load, enabling the architecture to scale fragment granularity dynamically during operation. This telemetry-responsive behavior contrasts with static fragmentation schemes that rely on fixed thresholds and cannot adapt to fluctuating resource conditions.

Accurate prediction enables the system to increase fragment size during periods of high throughput and reduce fragment size during constrained resource conditions, improving both upload efficiency and dispersion security. The requirement to retain two encrypted fragments within a secure local vault further ensures that reconstruction remains infeasible without local access. These observations reinforce the system’s design principle of integrating adaptive intelligence with distributed trust to achieve secure, stable multi-cloud operation [35]. While adaptive fragment-size regulation improves efficiency and reconstruction resistance, potential side-channel leakage through access-pattern observation or traffic analysis is outside the assumed threat model of this work and is identified as an important direction for future research.

4.4. Relevance to Multi-Cloud Security and Deployment

The decentralized and cloud-agnostic structure of the DataVault system supports balanced distribution across independent providers while preserving consistent fragmentation logic. In adversarial scenarios such as credential compromise or provider-side breach, reconstruction remains impossible without access to both the local fragments and the encryption key. This approach aligns with emerging multi-factor resilience and distributed trust models [36].

Telemetry-driven fragmentation also reduces redundancy overhead relative to full-duplication storage strategies. By predicting optimal fragment sizes instead of relying on fixed or replicated fragments, the architecture achieves more predictable throughput while maintaining confidentiality. These behaviors indicate that predictive fragmentation can support secure, performance-aware operation even under volatile network and system conditions.

4.5. Practical Recommendations and Future Directions

Several practical recommendations emerge from these findings. Ensemble learners such as Random Forest and XGBoost provide the most stable predictive foundation and should serve as the core models for real-time fragmentation control. Training pipelines benefit from the incorporation of hybrid telemetry, which strengthens model generalization and reduces variance. Retaining two encrypted local fragments within a secured vault is essential for enforcing distributed trust and preventing cloud-only reconstruction. Telemetry-guided fragmentation is preferable to static schemes because it adapts more effectively to bandwidth, latency, memory, and disk fluctuations while improving both confidentiality and performance.

Future research may extend the architecture to additional cloud providers and explore reinforcement learning techniques that adjust fragmentation policies in response to real-time telemetry drift. Integrating anomaly detection for proactive threat mitigation and investigating energy-aware fragmentation strategies also represent promising directions for enhancing the intelligence, efficiency, and resilience of multi-cloud storage systems.

The next section presents the security and resilience validation experiments that complement the predictive evaluation and demonstrate the system’s ability to operate within a secure multi-cloud framework.

5. Security Validation and Attack Resilience

This section evaluates the resilience of the proposed architecture against data loss, unauthorized reconstruction, and integrity compromise. Validation was performed across three layers: (1) reconstruction resistance, (2) partial-access resilience, and (3) fault-recovery integrity. Together, these tests demonstrate that encrypted payloads cannot be reconstructed or decrypted without all authentic fragments and the AES-128 key, regardless of an adversary’s computational capability.

5.1. Reconstruction Resistance

Controlled reconstruction trials confirmed that recovery cannot proceed when any authentic fragment is absent. Complete reconstruction was successful only when all authentic splits and the AES-128 key were simultaneously available. The removal of even a single fragment, whether 1 percent or 90 percent of the total, consistently resulted in failure through either decryption rejection or checksum mismatch. Table 4 summarizes the reconstruction outcomes observed when authentic fragments were selectively omitted.

Table 4.

Summary of the outcomes when authentic fragments were selectively removed.

Each reconstruction result reflects multiple independent trials conducted under both random and systematic fragment-removal strategies to verify that reconstruction failure was not dependent on fragment position or selection order.

These findings underscore the strict dependency between cloud-resident fragments and the locally retained vault fragments, reinforcing the zero-trust reconstruction principle outlined earlier. The architecture is deliberately designed so that no individual storage domain contains sufficient information to initiate or advance the recovery process. The absence of any authentic fragment breaks the reconstruction path entirely, preventing adversaries from exploiting partial cloud exposure and ensuring that full restoration is possible only when all required trust domains participate.

5.2. Partial-Access Resilience

To evaluate adversarial conditions, several scenarios were constructed in which an attacker obtained partial fragment sets, the encryption key alone, or combinations that lacked the complete set of authentic components. In all configurations with incomplete access, the fragments disclosed no meaningful information. Entropy analysis confirmed that each fragment functioned as an independent high-entropy unit, exhibiting no cross-fragment correlation that could support inference or reconstruction. Successful recovery occurred only in the authorized configuration, which requires simultaneous access to all cloud fragments, the local vault fragments, and the AES-128 key. Fragment entropy was evaluated using Shannon entropy computed over encrypted fragment payloads of uniform size. The analysis was performed across all authentic fragments generated per file, confirming consistently high entropy values with no observable cross-fragment correlation. Reconstruction feasibility across these partial-access scenarios is summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Reconstruction feasibility under partial-access scenarios.

These results demonstrate strong information-theoretic protection. Without complete access to all authentic fragments, the system reveals no structural, statistical, or semantic information about the original payload. Each fragment remains an isolated, high-entropy block with no recoverable patterns or contextual cues, even when subjected to advanced analytical techniques [37].

5.3. Fault-Recovery Integrity

Integrity validation was evaluated under simulated corruption scenarios, including bit flips, additive bytes, and byte removal. In all cases, the corrupted fragments were detected and rejected during pre-decryption validation, achieving a 100 percent detection rate across all trials. The results of the integrity validation under simulated corruption scenarios are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Integrity validation under simulated corruption tests.

These results demonstrate that neither accidental corruption nor adversarial manipulation can produce a usable fragment or induce partial or falsified reconstruction. The integrity verification layer reliably prevents malformed data from progressing to decryption, consistent with prior observations on corruption and anomaly detection in distributed cloud environments [20].

5.4. Security Implications

Across all validation layers, the architecture demonstrates strong confidentiality, resilience, and operational integrity. Reconstruction cannot proceed without the complete set of authentic fragments and the AES-128 key. Partial-access attempts disclose no meaningful information, and corrupted fragments are consistently rejected during integrity verification. Collectively, these results confirm that telemetry-guided fragmentation combined with secure local retention establishes a verifiable zero-trust reconstruction model. This security foundation supports scalable and resilient operation across multi-cloud environments.

6. Conclusions

This study introduced an AI-driven hybrid architecture for secure and reconstruction-resistant multi-cloud storage, demonstrating through predictive evaluation and security experiments that telemetry-guided control can enhance both confidentiality and operational efficiency. The system integrates AES-128 encryption, model-based adaptive fragmentation, and mandatory local vault participation, ensuring that no single trust domain, whether cloud or local, holds sufficient information to reconstruct the protected data independently. This distributed trust boundary strengthens resilience against provider-side compromise and cloud-only reconstruction attempts.

Predictive evaluations using synthetic and hybrid telemetry showed that ensemble models, particularly Random Forest and XGBoost, deliver consistently low-error and stable fragment-size predictions across heterogeneous operating conditions. Their generalization under real telemetry variability supports the feasibility of deploying adaptive fragmentation in production environments where bandwidth, latency, and system load fluctuate over time. Security validation further confirmed reconstruction resistance, confidentiality under partial-access conditions, and fault-recovery integrity. These results demonstrate that the architecture preserves confidentiality even when cloud-resident fragments are exposed.

Although the implementation was evaluated using two cloud providers and a defined telemetry scope, the framework itself imposes no inherent limits on scalability or provider diversity. Future work may explore extended reinforcement learning for continuous fragmentation policy adjustment, broader multi-provider orchestration to increase deployment flexibility, and telemetry-driven anomaly detection to support autonomous operation. The hybrid architecture presented in this study provides a verifiable foundation for secure and resilient multi-cloud storage, enabling stronger assurances of confidentiality, integrity, and reconstruction control.

Author Contributions

M.A.: conceptualization, methodology, system design and implementation, data collection and analysis, software development, visualization, and manuscript preparation. J.-S.Y.: supervision, validation, methodological guidance, manuscript review, and final approval. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data, trained models, and evaluation scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Article processing charges were provided in part by the UCF College of Graduate Studies Open Access Publishing Fund. The authors extend appreciation to the University of Central Florida for providing academic and technical support. Various digital tools were used responsibly to assist with formatting, data visualization, and language refinement. All outputs were carefully reviewed and verified by the authors, who assume full responsibility for the final manuscript content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- MOVEit Transfer Critical Vulnerability. Progress Community. 31 May 2023. Available online: https://community.progress.com/s/article/MOVEit-Transfer-Critical-Vulnerability-31May2023 (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Kapko, M. Massive Snowflake-Linked Attack Exposes Data on Nearly 110M AT&T Customers. 2024. Available online: https://www.cybersecuritydive.com/news/att-cyberattack-snowflake-environment/721235/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

- Jones, D. Hacker Linked to Oracle Cloud Intrusion Threatens to Sell Stolen Data. Cybersecurity Dive. 31 March 2025. Available online: https://www.cybersecuritydive.com/news/hacker-linked-to-oracle-cloud-intrusion-threatens-to-sell-stolen-data/743981/ (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Alonso, J.; Orue-Echevarria, L.; Casola, V.; Torre, A.I.; Huarte, M.; Osaba, E.; Lobo, J.L. Understanding the Challenges and Novel Architectural Models of Multi-Cloud Native Applications—A Systematic Literature Review. J. Cloud Comput. 2023, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Huo, Z.; Fan, Y. DRA: A data reconstruction attack on vertical federated k-means clustering. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 250, 123807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yuan, X.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, K.; Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Ma, J. FuzzyDedup: Secure Fuzzy Deduplication for Cloud Storage. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2022, 20, 2466–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiyza, A.I.; Korany, N.O.; Banawan, K.; Hassan, H.A.; Sheta, W.M. VTGAN: Hybrid Generative Adversarial Networks for Cloud Anomaly Detection. J. Cloud Comput. 2023, 12, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoda Parast, F.; Sindhav, C.; Nikam, S.; Yekta, H.; Al-Sadoon, M.; Matrawy, A. Cloud Computing Security: A Survey on Service-Based Models. Comput. Secur. 2021, 114, 102580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.; Kumar, J.; Singh, A.K.; Schmid, S. Performance Analysis of Machine Learning Centered Workload Prediction Models for Cloud. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2023, 34, 1313–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Tian, W.; Buyya, R.; Xue, R.; Song, L. Deep Reinforcement Learning-Based Methods for Resource Scheduling in Cloud Computing: A Review and Future Directions. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S. Random Forest-Based Load Prediction for Cloud Data Centers. In Proceedings of the IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Systems and Computer Aided Education (ICISCAE), Dalian, China, 27–29 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizar, N.A.; Raj, K.P.M.; Kumar, V.B. Anomaly Detection in Telemetry Data Using Ensemble Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Computing and Communication Technologies (CONECCT), Bangalore, India, 8–10 July 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.; Shen, C.; Cao, L.; Van Den Hengel, A. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection: A Review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, A.; Gulia, P.; Gill, N.S. Advancing Cloud Anomaly Detection: A Machine Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT), Hubbali, India, 20–22 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harish, G.N.; Annapurna, H.S. Survey on Machine Learning Based Anomaly Detection in Cloud Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge Engineering and Communication Systems (ICKECS), Chickballapur, India, 18–19 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Cloud Monitoring Dataset. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/microsoft/cloud-monitoring-dataset (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cisco. Cisco IE Telemetry Dataset. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/cisco-ie/telemetry (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Saurav, S.K.; Benedict, S. Energy Aware Scheduling Algorithms for Cloud Environments—A Survey. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference on Advances in Computing, Communication, Embedded and Secure Systems (ACCESS), Ernakulam, India, 2–4 September 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardebili, A.A.; Hasidi, O.; Bendaouia, A.; Khalil, A.; Khalil, S.; Luceri, D.; Longo, A.; Abdelwahed, E.H.; Qassimi, S.; Ficarella, A. Enhancing Resilience in Complex Energy Systems through Real-Time Anomaly Detection: A Systematic Literature Review. Energy Inform. 2024, 7, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madabhushi, S.; Dewri, R. A Survey of Anomaly Detection Methods for Power Grids. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 22, 1799–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, M.; Meyer, V.; Zorzo, A.; De Rose, C.A.F. A Modular Architecture and a Cost-Model to Estimate the Overhead of Implementing Confidentiality in Cloud Computing Environments. In Anais do XXV Simpósio em Sistemas Computacionais de Alto Desempenho (SSCAD), São Carlos, SP, Brazil, 23–25 October 2024; Sociedade Brasileira de Computação: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, Z. Rearchitecting Approximation-First Cloud Telemetry. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGCOMM 2025 Posters and Demos, Coimbra, Portugal, 8–11 September 2025; pp. 140–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śliwko, L. Cluster Workload Allocation: A Predictive Approach Leveraging Machine Learning Efficiency. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 194091–194107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorantla, V.A.K.; Gude, V.; Sriramulugari, S.K.; Yuvaraj, N.; Yadav, P. Utilizing Hybrid Cloud Strategies to Enhance Data Storage and Security in E-Commerce Applications. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Disruptive Technologies (ICDT), Greater Noida, India, 15–16 March 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, R.; Supriya, M. RLPRAF: Reinforcement Learning-Based Proactive Resource Allocation Framework for Resource Provisioning in Cloud Environment. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 95986–96007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phukseng, T.; Nanuam, J.; Thongnim, P. Feature Scaling Optimization for Durian Characteristic Prediction using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the International Technical Conference on Circuits/Systems, Computers, and Communications (ITC-CSCC), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 7–10 July 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yekta, M.; Shahhoseini, H.S. A Review on Machine Learning Methods for Workload Prediction in Cloud Computing. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computer and Knowledge Engineering (ICCKE), Mashhad, Iran, 1–2 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoj, M.; Remya, M.; Mishra, P.C.; Vadrevu, R.; Raza, M.T.; Reddy, M.K. AI-Based Load Forecasting And Resource Optimization for Energy-Efficient Cloud Computing. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 2957–2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Meng, F. An Improvement on “CryptCloud++: Secure and Expressive Data Access Control for Cloud Storage”. IEEE Trans. Serv. Comput. 2023, 16, 1662–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Q.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wei, Z. Multi-Authority Attribute-Based Searchable Encryption in Cloud Storage. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology (ICCSNT), Dalian, China, 21–22 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, P.; Li, X.; Gangopadhyay, A.; Busart, C.E.; Freeman, J.; Wang, J. Reproducible and Portable Big Data Analytics in the Cloud. IEEE Trans. Cloud Comput. 2023, 11, 2966–2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, N.; Khan, M.A.; Alsuhibany, S.A.; Diyan, M.; Tan, Z.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, J. Ensemble Learning-Based IDS for Sensors Telemetry Data in IoT Networks. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2022, 19, 10550–10580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Bengio, S.; Hardt, M.; Recht, B.; Vinyals, O. Understanding Deep Learning (Still) Requires Rethinking Generalization. Commun. ACM 2021, 64, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Jia, Z.; Liu, W.; Liu, C. Design and Implementation of Secure Cloud Storage System based on Hybrid Cryptographic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Algorithms for Computational Intelligence Systems (IACIS), Hassan, India, 23–24 August 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldani, D.; Nahi, P.; Bour, H.; Jafarizadeh, S.; Soliman, M.F.; Di Giovanna, L.; Monaco, F.; Ognibene, G.; Risso, F. eBPF: A New Approach to Cloud-Native Observability, Networking and Security for Current (5G) and Future Mobile Networks (6G and Beyond). IEEE Access 2023, 11, 57174–57202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- fragmentiX. Secret Sharing in Practice for Scalable, Robust, and Future-Proof Data Protection. (Part 2: Beyond Shamir). fragmentiX Blog 2024. Available online: https://fragmentix.com/secret-sharing-in-practice/ (accessed on 12 February 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.