Abstract

Temporal knowledge graphs (TKGs) incorporate temporal information into traditional triplets, enhancing the dynamic representation of real-world events. Temporal knowledge graph reasoning aims to infer unknown quadruples at future timestamps through dynamic modeling and learning of nodes and edges in the knowledge graph. Existing TKG reasoning approaches often suffer from two main limitations: neglecting the influence of temporal information during entity embedding and insufficient or unreasonable processing of relational structures. To address these issues, we propose DERP, a relation-aware reasoning model with dynamic evolution mechanisms. The model enhances entity embeddings by jointly encoding time-varying and static features. It processes graph-structured data through relational graph convolutional layers, which effectively capture complex relational patterns between entities. Notably, it introduces an innovative relational-aware attention mechanism (RAGAT) that dynamically adapts the importance weights of relations between entities. This facilitates enhanced information aggregation from neighboring nodes and strengthens the model’s ability to capture local structural features. Subsequently, prediction scores are generated utilizing a convolutional decoder. The proposed model significantly enhances the accuracy of temporal knowledge graph reasoning and effectively handles dynamically evolving entity relationships. Experimental results on four public datasets demonstrate the model’s superior performance, as evidenced by strong results on standard evaluation metrics, including Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), Hits@1, Hits@3, and Hits@10.

1. Introduction

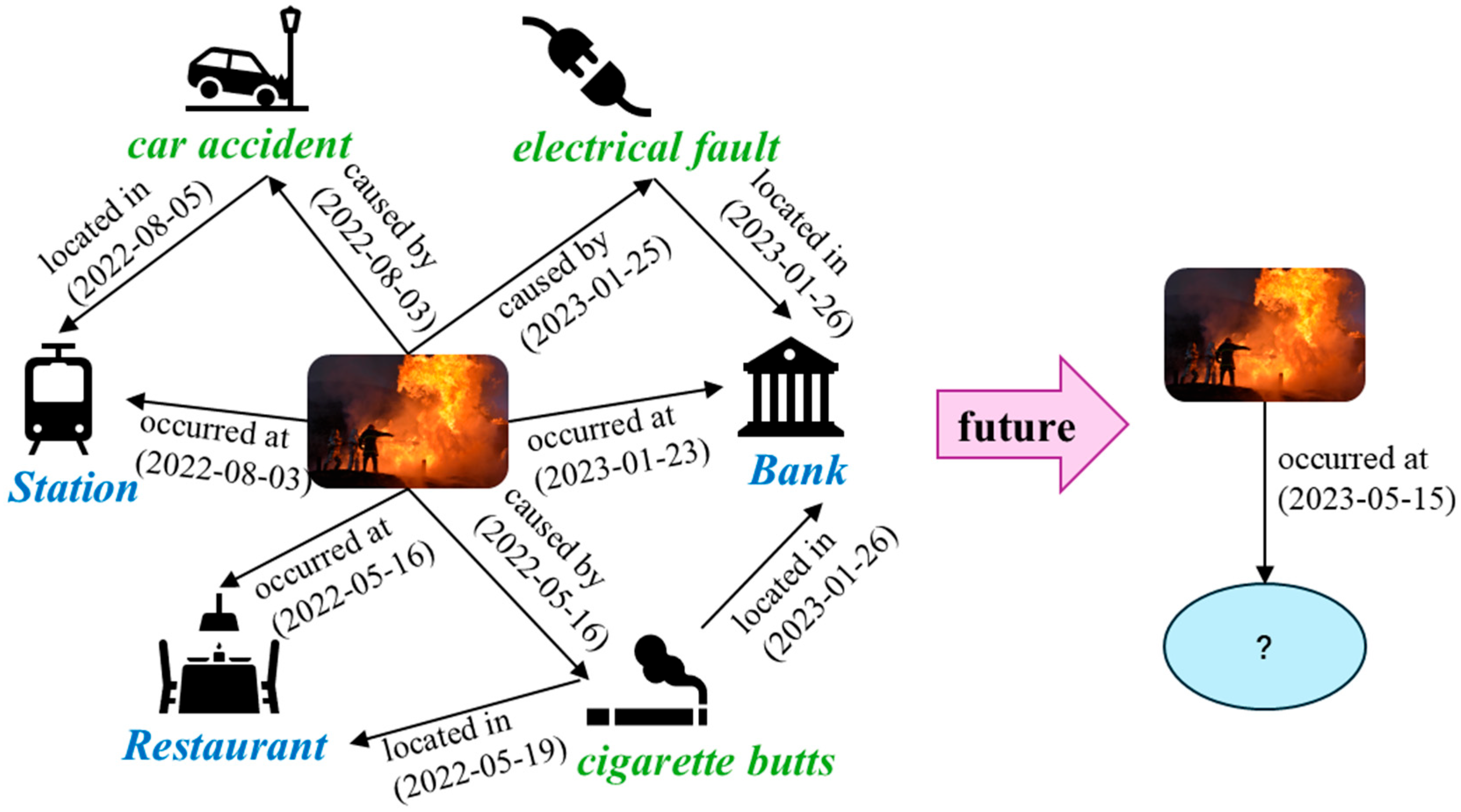

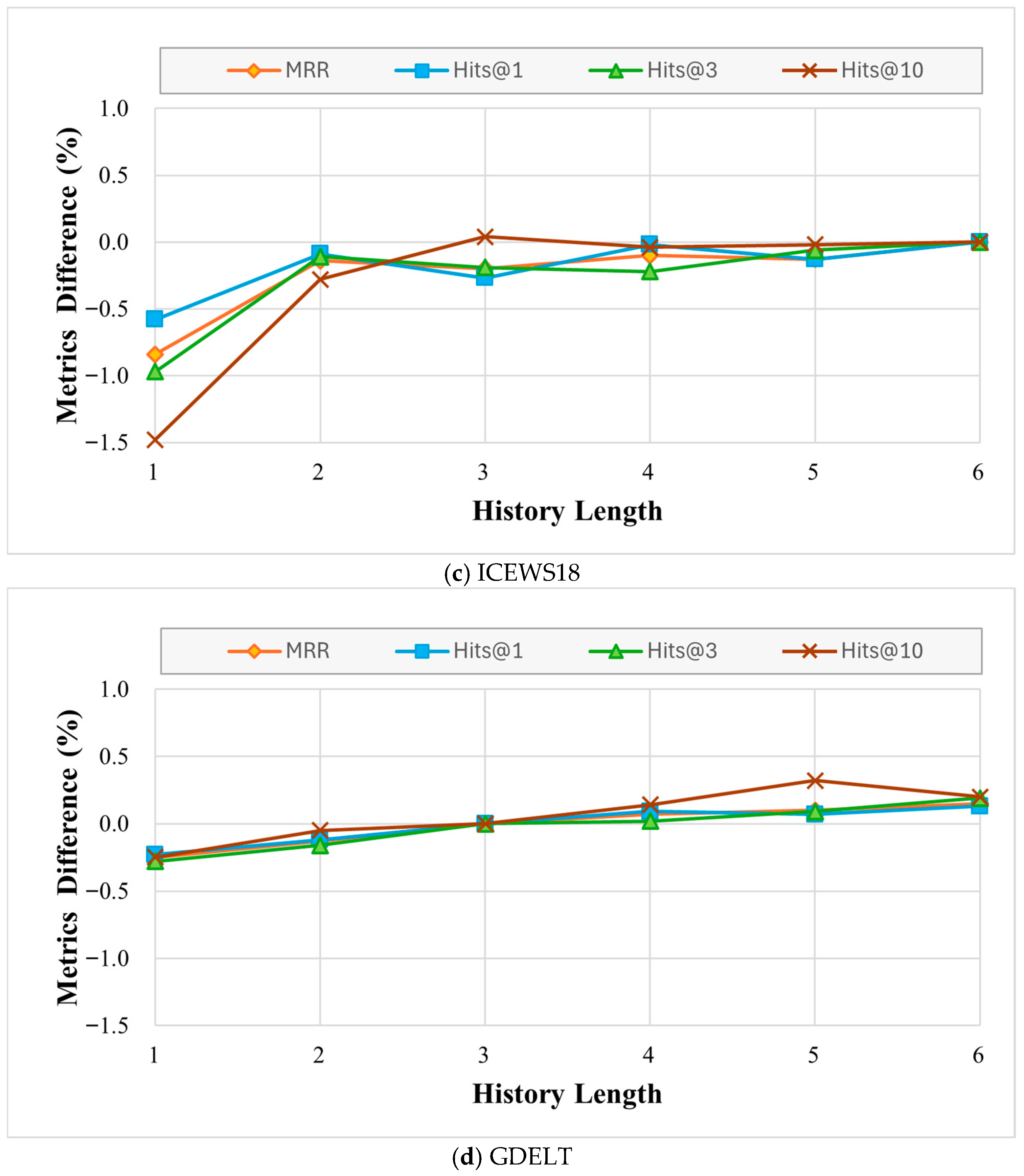

Knowledge graphs, as structured semantic networks, employ sets of triples to represent multi-dimensional relationships among concepts, events, and real-world entities. For instance, triples such as (China, capital, Beijing) are commonly used to express knowledge in static knowledge graphs. In real-world scenarios, however, relationships between entities are often dynamic and evolve over time. Traditional knowledge graphs primarily capture static commonsense knowledge and typically do not incorporate temporal information. Consequently, they are unable to handle the vast and continuously growing volume of temporal knowledge generated in cyberspace. To model such dynamic changes, researchers have developed a novel knowledge representation framework termed Temporal Knowledge Graph (TKG), which incorporates a temporal dimension into traditional triples to form quadruples. Figure 1 illustrates example subgraphs of a temporal knowledge graph. Due to their intuitive and expressive framework for representing time-varying knowledge, TKGs have attracted widespread research attention. This quadruple structure enables detailed documentation of temporal events—for instance, the quadruple (fire, occurred_at, building_X, 15 May 2023) can describe a specific fire incident. Moreover, TKGs hold significant value for applications such as machine translation, intelligent question answering, and recommendation systems. The objective of temporal knowledge graph reasoning is to infer missing components of future events based on historical quadruple data. For example, given quadruples recorded before 15 May 2023, the task is to predict the answer entity for the query (fire, occurred_at, ?, 15 May 2023). Guided by this principle, a variety of research methodologies have been proposed.

Figure 1.

Fragment of the temporal knowledge graph (TKG) for fire incidents. Our task is to predict interactions and build graphs in future times. The scenarios and events included herein are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent the actual test database used in this research.

Temporal knowledge graphs are intrinsically incomplete upon construction, regardless of whether automated extraction techniques or manual curation are employed. Consequently, the performance of downstream applications relying on such graphs is significantly constrained. Based on the temporal information of the missing data, current approaches to this problem can be divided into two categories: interpolation tasks, which infer missing entities within existing time periods using historical data, and extrapolation tasks, which predict future facts based on temporal evolution patterns. The primary advantage of extrapolation tasks over interpolation tasks lies in their ability to forecast future events, aligning more closely with the needs of dynamic reasoning in real-world scenarios. Thus, they represent a more challenging and forward-looking direction. Most existing TKG reasoning models inadequately capture the dynamic interplay between temporal information and relational structures. Such interactivity is crucial for accurately representing real-world entities and relationships that evolve over time. To address this gap, the proposed model generates initial entity embeddings by integrating long-term and short-term temporal embeddings with temporal positional encoding. It then employs relational graph convolution layers to process graph-structured data, thereby capturing temporal variations in entity interactions. Furthermore, the model proposes RAGAT, which dynamically adjusts relational weights among entities and aggregates information from neighboring nodes, significantly improving the rationality and accuracy of entity and relationship encoding. Finally, the model uses ConvTransE as the decoder to generate results for the TKG reasoning task.

The primary contributions of this study are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- We propose the DERP model for TKG reasoning, which not only effectively captures the evolution of historical facts but also learns diverse structural and temporal relationships within the TKG structure. Specifically, we introduce a dynamic embedding approach that integrates short-term and long-term temporal features with temporal positional encoding. Through dynamically modifying entity representations via a temporal weight matrix, this approach enables fine-grained modeling of entity semantic evolution over time, significantly enhancing the accuracy of dynamic relationship modeling in TKGs.

- (2)

- We introduce an innovative Relational-aware Attention Network (RAGAT) and integrate it with relational graph convolution layers. This design enables dynamic optimization of aggregation weights for different relation types, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional approaches that treat all relations uniformly, while also remedying the flaws of existing graph-attention-based models—their disregard for relational semantics and excessive reliance on local neighbors.

- (3)

- Through systematic experiments on four public datasets, this study demonstrates the DERP model’s capability to capture critical information from TKGs. The results indicate a significant advantage of the model in complex temporal reasoning tasks compared with state-of-the-art approaches.

2. Related Works

2.1. Static Knowledge Graph Reasoning

Early research in knowledge graph reasoning primarily focused on static settings. Representative approaches include DistMult [1], which learns relational semantics via bilinear target embeddings; ComplEx [2], which employs complex embeddings and a Hermitian dot product; RotatE [3], which employs a geometric mapping approach via rotations in a complex space. With the advancement of Knowledge Graph (KG) embedding learning, researchers have increasingly explored neural network-based methods. Notable examples include: ConvE [4] and ConvTransE [5], which utilize convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to capture multi-hop relational interactions and incorporate temporal gating mechanisms. In graph structure modeling, Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) capture structural features through a message passing mechanism, while R-GCN [6] further introduces relation-specific block diagonal matrices to handle multi-relational graph data. More recent studies have further explored compositional operations. For instance, CompGCN [7] enhances relational modeling by integrating the translation assumption from TransE [8] with a learnable compositional mechanism, thereby improving the representation of complex relational patterns.

However, the aforementioned methods typically lack explicit mechanisms for temporal dynamics, which limits their ability to effectively capture the complex temporal dependencies that evolve over time within knowledge graphs. When traditional static models are directly applied to temporal knowledge graphs, they typically encounter several limitations, such as failing to account for time-sensitive semantic variations and struggling to model temporal dependencies among facts. These limitations significantly constrain their effectiveness in dynamic scenarios, particularly for tasks that require fine-grained temporal reasoning.

2.2. Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning

According to the temporal properties of missing facts, temporal knowledge graph reasoning can be categorized into two types of tasks: interpolation and extrapolation. Interpolation seeks to complete missing facts within a specific time range by analyzing historical snapshots in the TKG and completing entities at intermediate timestamps where information is missing. Conversely, extrapolation focuses on forecasting potential new facts at future timestamps by capturing the dynamic evolutionary patterns of entities and relations that arise from continuous temporal progression.

2.2.1. Interpolation Setting

The interpolation reasoning task in temporal knowledge graphs aims to infer missing facts at intermediate timestamps by leveraging observed historical data. Early research primarily extended static knowledge graphs embedding frameworks by incorporating temporal information. For the interpolation reasoning, TTransE [9] extends the TransE model by treating relations and time as translations between entities. By introducing temporal order constraints into the scoring function, it incorporates time as supplementary information for evaluating the validity of a triple fact. ConT [10] introduces semantic and episodic memory mechanisms [11] by extending static representations into episodic tensors. DE-SimplE [12] captures entity characteristics across different timestamps through a diachronic entity embedding function, and uses SimplE [13] scoring function to evaluate quadruple plausibility. TcomplEx [14] extends the existing ComplEx model by introducing a temporal dimension parameter and fusing temporal information with entity-relation interaction features through a tensor decomposition strategy, achieving dynamic time modeling and accurate calculation of quadruple scores. TARGCN [15] modeled temporal structure information utilizing a functional temporal encoder. TempCaps [16] is a capsule network model that generates entity embeddings using data obtained via dynamic routing. DyERNIE [17] learns the evolving entity representations of TKGs through the product of Riemannian manifolds, capturing diverse geometric structures and evolutionary dynamics more comprehensively.

2.2.2. Extrapolation Setting

This paper focuses on the extrapolation task, which involves constructing models that analyze historical data to infer missing entities in future timestamps. Know-Evolve [18] integrates temporal point processes with deep neural network frameworks by modeling time as a random variable, learning non-linear evolution patterns of entity representations over time, and modeling fact occurrences as temporal point processes. Building on this, DyREP [19] proposes a dynamic graph representation learning framework that divides network evolution into two dimensions: relational evolution and social evolution. It models the occurrence process through a triple mechanism involving local embedding propagation, self-propagation, and external factor-driven processes. Given their strong ability to model graph-structured data, Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have been widely adopted for entity-relation modeling and temporal feature extraction. RE-NET [20] combines recurrent neural networks with neighborhood aggregators, representing historical events as sequences of subgraphs to better capture the temporal relationships and evolution patterns among events. To support reasoning, GHNN [21] also incorporates the subgraph data surrounding the searched object. TANGO [22] constructs an efficient continuous-time reasoning framework by integrating neural ordinary differential equations with diffusion models. xERTE [23] employs graph sampling and dynamic pruning to capture subgraph information relevant to queries, and jointly models temporal context to interpretable reasoning subgraphs. TITer [24] leverages a reinforcement learning framework to dynamically search and optimize reasoning over historical facts. RE-GCN [25] effectively captures structural dependencies at each timestamp through a relation-aware graph convolutional network, while incorporating global static attribute information to enhance learning quality. Tlogic [26] proposes a symbolic framework that constructs temporal logic rules via sequential random walk extraction. CEN [27] employs an ensemble of sequential GNNs with varying historical lengths. Re-Temp [28] combines explicit temporal encoding with implicit temporal modeling capabilities through a relation-aware skip information flow mechanism and a two-stage forward propagation strategy, addressing limitations in dynamic interaction modeling and query-related redundancy filtering. To anticipate future relationships in a TKG given little historical data, [29] proposes one-shot TKG extrapolation link prediction. CENET [30] utilizes the frequency of historical events and contrastive learning to capture the correlations between historical and non-historical events, facilitating the prediction of matching entities. TRCL [31] predicts target entities through the integration of recurrent encoding and contrastive learning. However, contrastive learning exhibits suboptimal performance when applied to complex datasets. TaReT [32] leverages a time-aware graph-attention network to distill the structural signatures of co-occurring facts, employs Topology-Aware Correlation Units (TACU) to encode relational interplay, and unites deep periodic rhythms with shallow sequential dynamics through a dual-gate fusion mechanism. RLAT [33] is a reinforcement learning-enhanced multi-hop reasoning model featuring an influence-factor-augmented graph attention module.

3. Method

3.1. Problem Formulation

Traditional knowledge graphs are collections of triple facts represented as , where (head entity) and (tail entity) belong to the entity set , and belongs to the relations set. Temporal knowledge graphs extend traditional knowledge graphs by incorporating a temporal dimension. Their core structure comprises a sequence of static knowledge graph snapshots at discrete timestamps, represented as , where denotes the historical subgraph at timestamp , containing facts occurring at . Each triple can be extended into a fact quadruple by adding the timestamp , where belongs to the set of timestamps. Temporal knowledge graph reasoning aims to infer the missing tail entity in an incomplete query quadruple event , given the historical sequence of events .

3.2. DERP Model

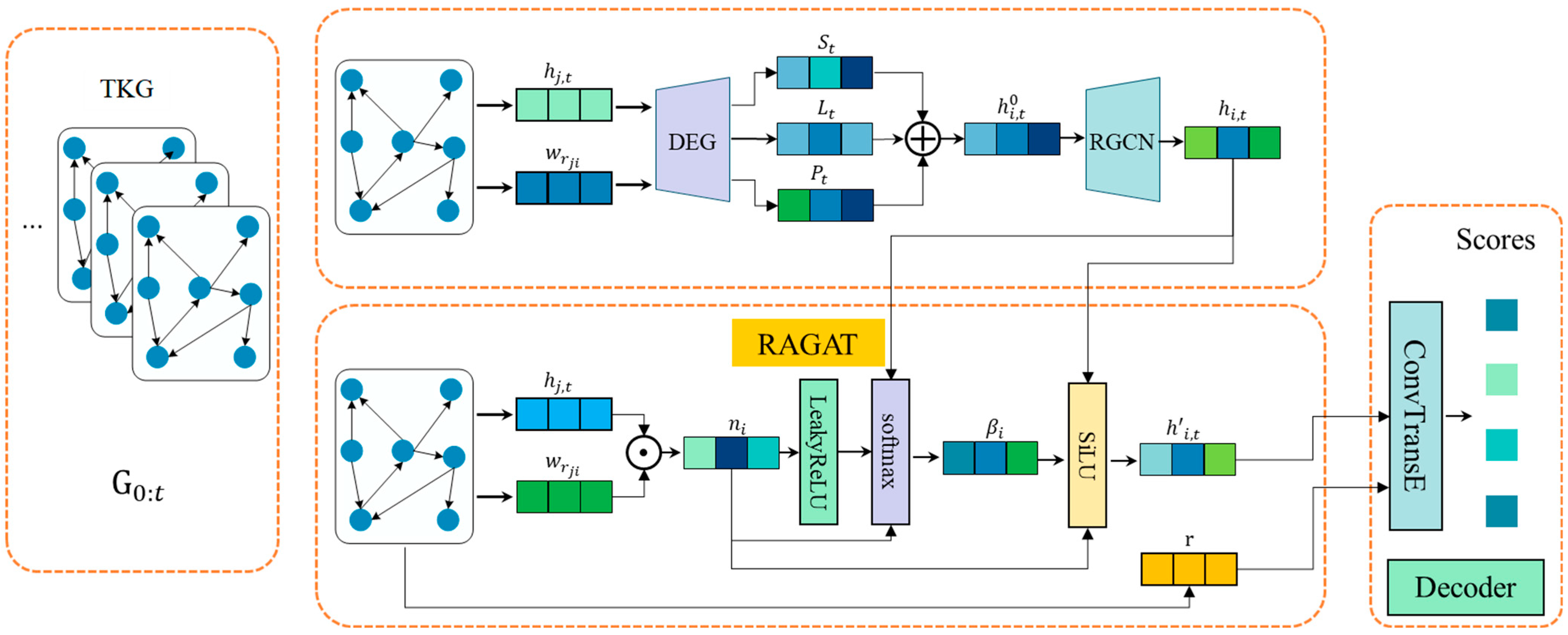

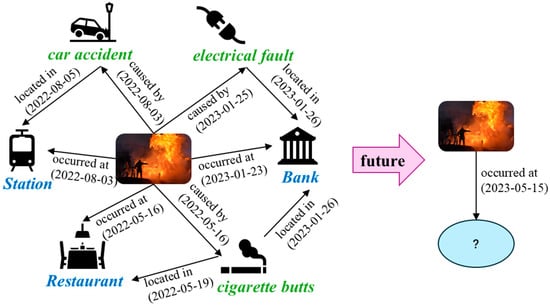

This paper proposes a temporal knowledge graph reasoning model named DERP, which integrates dynamic evolution and relation perception mechanisms. The model consists of four main components: (1) Dynamic embedding generation module (DEG), (2) Dynamic relational graph encoding module (DRG), (3) Relational-aware Attention Network (RAGAT), and (4) Scoring decoder. that implements the core relation-aware component.

The overall framework of the proposed model is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Illustration of Encoding and Decoding process in DERP. DEG represents Dynamic Embedding Generation, RAGAT represents the core implementation of the relation perception component. denotes entity short-term temporal features, denotes entity long-term temporal features, and denotes entity event location information. This yields an embedding representation incorporating temporal features, which is fed into RGCN to obtain . denotes the aggregated feature vector of node ’s neighbors, denotes relation-aware attention coefficients, and represents the final entity embedding representation. Then the decoder measures the score of all candidates.

3.2.1. Dynamic Embedding Generation Module (DEG)

In knowledge graph reasoning tasks, the semantic representation of the same entity can change across different timestamps due to variations in connected entities or relations. The model must capture and model these temporal variations. To characterize entity representations at each timestamp , we design a dynamic embedding generation module aimed at capturing the temporal evolution of entities along the temporal dimension. Unlike RE-NET, which does not explicitly separate short-term and long-term temporal features; RE-GCN, which lacks the ability to handle multi-scale temporal information, and TANGO, which lacks explicit modeling of linear and quadratic terms, hindering the capture of trend-based feature changes. We construct a dynamic embedding representation that captures entity evolutionary patterns by integrating static entity features with time-varying dynamic features (short-term, long-term, and temporal positional encoding). First, short-term temporal features are denoted by , capturing immediate trends via a linear term and repetitive short-term fluctuations using a periodic sine function. Second, the long-term temporal features are denoted by , modeled by a quadratic term to simulate acceleration or deceleration over time, combined with a periodic cosine function to capture slower, longer-term cyclical patterns. Third, position-time encoding employs a sequence of sine and cosine functions to map a time point into a high-dimensional vector, thereby capturing its positional information. These dynamic entity embeddings are subsequently utilized in other model components to capture temporal characteristics of nodes/graphs. This approach enables the model to dynamically adjust the entity embedding representations based on changes and intrinsic entity attributes, thereby enhancing the capture of temporal relations in the knowledge graph. As shown in Equation (1), the embedding representation of a dynamic entity considers both intrinsic entity features and time-varying characteristics.

where is the static embedding representation of the entity, and is the temporal weight matrix, represents the linear effect and periodic variation in time and serves as the short-term temporal vector. represents the quadratic effect and periodic variation in time and serves as the long-term temporal vector. denotes the temporal positional encoding, the concatenation operation is symbolized by . The short-term and long-term vectors, together with the temporal positional encoding, are concatenated to form the complete dynamic embedding. The definitions are given in Equations (2)–(4):

where is a fixed hyperparameter that controls the trade-off between short-term and long-term temporal features, determining their contribution ratio in the dynamic temporal embedding, and is set to 0.5 based on ablation studies (Section 4.5.2). is a learnable weight matrix that enables the model to adaptively adjust the contribution of linear/quadratic terms versus periodic terms for each entity. dynamically controls the frequency of temporal feature variations, enabling the model to adapt to time dynamics of varying speeds. is the maximum time range used to define the temporal positional encoding.

3.2.2. Dynamic Relational Graph Encoding Module

In knowledge graph reasoning tasks, capturing and utilizing relational information between nodes is a key research focus. In traditional graph convolutional networks, the connections typically represent either a single relation type or merely indicate connectivity. In contrast, relational graph convolutional networks (RGCNs) introduce a mechanism to differentiate relation types of neighbors. In DERP, the relational graph convolutional network serves as the foundational module for evolution, responsible for propagating and updating entity embeddings within the knowledge graph, thereby providing the model with robust graph structure learning capabilities. Regarding the RGCN architecture, an excessive number of relational layers can introduce substantial irrelevant neighboring information, compromising the quality of entity embeddings. Therefore, this paper adopts a two-layer RGCN structure. By limiting the number of layers, the encoder effectively avoids excessive noise interference while aggregating neighboring node information, thereby enhancing the accuracy and semantic expressiveness of the entity embeddings. In this framework, information aggregation for each node is achieved by aggregating nodes according to different edge types. The model structure is formulated as follows:

where and are the two propagation weights of the network layer; are the updated embedding representation of the -th entity .

3.2.3. Relational-Aware Attention Network (RAGAT)

In temporal knowledge graphs, different relations vary in importance for reasoning tasks, and this task-specific importance dynamically evolves with time and context. Traditional Graph Attention Network (GAT) [34] calculates attention weights exclusively on node features, neglecting the influence of edge relation types on information importance. To address this limitation, we propose a Relational-aware Attention Network (RAGAT), which explicitly integrates relational weights in both the message weighting and attention score computation stages. This design enables adaptive adjustment of the contribution from edges with different semantic meanings to the target node, allowing the model to more accurately capture node-to-node associations and their varying significance, emphasize the impact of key neighboring nodes on the central node, and consequently refine the final node embeddings.

First, an adaptive relationship adjustment mechanism is used to learn a global importance coefficient for each relationship type. Specifically, we introduce a learnable parameter for each relation type , and compute normalized importance weights via softmax normalization. These weights are subsequently used to pre-weighting edge messages during the graph propagation phase, as shown in the following equation:

Next, we perform relation-weighted neighbor aggregation, as shown in the following equation:

where denotes the set of all neighbor nodes of node (excluding itself), represents the relationship weight on the edge from node to node , and denotes the current embedding vector of neighbor node . Then, for each node , compute the average of the weights of all its incoming edge relationships:

Next, we calculate the relation-aware attention coefficients, as shown in the following equation:

where is the LeakyReLU activation function. is a learnable parameter vector that assigns importance weights to each dimension of the concatenated features. is a learnable scaling scalar that adaptively adjusts the influence of the average relationship weight in the relationship-aware attention calculation.

Finally, the aggregated neighbors are re-weighted using the attention coefficients and added to the linear transformation of the node itself to update the output:

where is a trainable parameter.

3.2.4. Scoring Decoder

Existing studies demonstrate that ConvTransE achieves strong performance in knowledge graph reasoning tasks, effectively capturing complex interactions between entities and relations, and thereby improving reasoning accuracy and efficiency. In our model, ConvTransE is employed as the scoring decoder. Specifically, the query entity embedding and the query relation embedding are first concatenated. Then, a convolutional neural network (Conv1D) and a fully connected layer (FC) are used to learn the feature representations of entities and relations, integrating temporal information to predict the triple’s confidence score. The score for each candidate entity is obtained by computing the dot product between the entity’s embedding vector and the entity representation processed by ConvTransE. The process for computing the candidate entity ’s score is as follows:

After obtaining the score for each candidate entity using ConvTransE, we train the model as a classification problem. The loss function for each query is as follows:

where is 1 if classified correctly, and 0 otherwise. The training objective is to minimize the loss across all queries.

4. Experimental Analysis

4.1. Datasets

In this study, four widely used public datasets were selected for entity reasoning experiments to evaluate the model’s performance: ICEWS14 [17], ICEWS05-15 [35], ICEWS18 [23], and GDELT [36]. The statistical details of the datasets are presented in Table 1. All datasets were split chronologically into training, validation, and test sets. For example, in ICEWS14, timestamps are divided into three intervals: 1–304 for training, 305–334 for validation, and 335–365 for testing. ICEWS14, ICEWS05-15, and ICEWS18 are subsets of the integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS), where each timestamp corresponds to a specific point in time. ICEWS14 and ICEWS18, respectively, cover international news events occurring from January to December 2014 and from January to October 2018. ICEWS05-15 is an updated version of the ICEWS dataset, containing more international event data. The GDELT dataset, derived from the Global Database of Events, Language and Tone, is a temporal knowledge graph dataset comprising global political events.

Table 1.

Detailed statistics of the dataset.

4.2. Evaluation Indicators

This study uses common evaluation metrics in knowledge graph reasoning models: Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) and Hits@K [37]. Specifically, Hits@K represents the probability of a correct prediction within the top K inference results, with common values being Hit@1, Hit@3, and Hit@10. The detailed calculation methods for these two metrics are shown in Equations (12) and (13):

where represents the set of quadruples in the test set, and rank denotes the rank of the true result among all predicted results.

4.3. Performance Comparison

To evaluate the inference performance of the DERP model, this paper selects a range of baseline models, including static knowledge graph reasoning models—DistMult [1] and ComplEx [2], R-GCN [6], ConvE [4], and ConvTransE [5]—as well as temporal knowledge graph reasoning models: RE-NET [20], xERTE [23], TITer [24], RE-GCN [25], Tlogic [26], CEN [27], CENET [30], RPC [38], LMS [39], TaReT [32] and TRCL [31].

The temporal knowledge graph reasoning models used for comparison are briefly described below:

- (1)

- RE-NET [20] addresses extrapolation by combining graph-based and sequential modeling to capture both temporal and structural relationships between entities.

- (2)

- xERTE [23] proposes a temporal relation attention mechanism and a reverse representation update strategy to effectively capture temporal dynamics and graph structural information.

- (3)

- TimeTraveler (TITer) [24] searches for the temporal evidence chain for prediction using reinforcement learning techniques.

- (4)

- RE-GCN [25] captures factual and temporal dependencies in temporal knowledge graphs through a relation-aware graph convolutional network combined with a recursive modeling mechanism, exhibiting strong joint modeling capabilities.

- (5)

- Tlogic [26] utilizes the high confidence rules to determine the target entities after extracting the temporal rule from the TKG.

- (6)

- CEN [27] enhances predictive accuracy by capturing temporal dynamics and length diversity of local facts and enhances its understanding of complex factual evolution patterns through an online learning strategy.

- (7)

- CENET [30] uses historical event frequency and contrast learning to forecast matching entities by establishing the correlation between historical and non-historical occurrences.

- (8)

- RPC [38] employs two correspondence units to capture intra-snapshot graph structure and periodic inter-snapshot temporal interactions.

- (9)

- LMS [39] improves prediction accuracy and generalization by learning multi-graph structures and using a time-aware mechanism, effectively modeling diverse time dependencies.

- (10)

- TaReT [32] operates reasoning by combining temporal fusion information with topological relation graphs.

- (11)

- TRCL [31] combines recurrent encoding with contrastive learning to enhance the accuracy and robustness of TKG extrapolation, addressing limitations related to irrelevant historical information and weak temporal dependency modeling.

- (12)

- DERP: The model proposed in this study.

Results on Public KGs: For ICEWS14 and GDELT, the history length was set to 3; for ICEWS05-15, it was set to 4; and for ICEWS18, it was set to 6. The impact of history length is discussed in Section 4.5. Table 2 and Table 3 present the performance comparisons of all the baseline models. The DERP model outperforms the other baseline models in terms of MRR and Hit@N metrics across all datasets, demonstrating its superior prediction accuracy. As shown in Table 1. Detailed statistics of the dataset, our DERP achieves the smallest MRR improvement of 2.53% on the ICEWS18 dataset and the largest MRR improvement of 7.55% on the ICEWS05-15 dataset. This is because the ICEWS18 dataset is highly dense: models can already learn many facts through pre-training, resulting in a relatively high baseline MRR. Consequently, the improvement margin brought by DERP is compressed, leading to a smaller performance gain. While ICEWS05-15 contains a large total number of facts, it has the lowest average number of facts per snapshot (32.2), indicating that individual snapshots are sparser. This suggests that our model can effectively learn from TKGs with limited information per timestamp, demonstrating its robustness in sparse temporal settings.

Table 2.

Performance (in percentage) for the entity prediction task on ICESW14 and ICEWS05-15. The highest value is bold.

Table 3.

Performance (in percentage) for the entity prediction task on ICESW18 and GDELT. The highest value is bold.

Based on these experimental outcomes, the following conclusions can be drawn. The DERP model significantly outperforms static KG reasoning methods (DistMult, ComplEx, R-GCN, ConvE, ConvTransE) by accounting for sequential patterns across different timestamps. Among existing advanced TKG extrapolation models (RE-NET, xERTE, RE-GCN, TITer, TLogic, CEN, CENET, RPC, LMS, TaReT and TRCL), all demonstrate markedly better performance on benchmark tests, confirming the importance of temporal evolution information and dynamic relationship modulation in TKG feature modeling and future prediction. These results provide compelling evidence and highlight the superiority of DERP. Specifically, while models such as RE-NET, xERTE, RE-GCN, and CEN models consider adjacent timestamps, DERP further enhances its ability to capture structural features and historical dependencies through its two-layer R-GCN encoder and RAGAT, leading to improved performance over these approaches. Furthermore, the DERP model outperforms the xERTE model because the latter utilizes subgraph-based search for target entity prediction, which has limitations in exploiting long-term information and hence limits its capacity to recognize complex temporal relationships. In contrast, DERP incorporates richer temporal and relational knowledge, yielding higher prediction precision. CENET utilizes the frequency of historical events and contrastive learning to capture the correlations between historical and non-historical events for predicting matching entities. However, it neglects the evolution of historical facts, resulting in suboptimal performance. In contrast, DERP emphasizes the evolution of historical facts, achieving a significant improvement in performance. RPC introduces two corresponding units to capture structural and temporal dependencies from relation and snapshot views. However, it lacks explicit modeling of the periodic semantics and structural relatedness in temporal vectors. LMS predicts target entities through multi-graph structure learning and a time-aware mechanism. Although it introduces a temporal graph, it only implicitly models global dependencies via periodic node connections, still falling short in explicitly capturing long-term temporal patterns compared to DERP. TRCL predicts target entities by combining recurrent encoding and contrastive learning. However, contrastive learning performs poorly when dealing with complex datasets. TimeTraveler (TITer) proposes a reinforcement learning-based approach that incorporates relative time encoding and a Dirichlet distribution-based temporal pattern reward function to model temporal information and guide policy learning. The method also supports inductive reasoning about unknown entities through an Inductive Mean (IM) mechanism. However, it focuses more on path reasoning and does not explicitly model historical evolution or periodic patterns, limiting its ability to capture long-term temporal dependencies. TLogic introduces a symbolic framework for constructing temporal logic rules based on sequential random walk extraction. It provides interpretable predictions by applying learned rules to forecast future links. However, TLogic does not explicitly model entity evolution or periodic temporal patterns, which are crucial for accurate forecasting. TaReT captures structural information of co-occurrence facts through time-aware GAT, models relational associations using Topology-Aware Correlation Units (TACU) and integrates deep (periodic) and shallow (sequential) temporal information via a dual-gate fusion mechanism. Compared to DERP, TaReT places greater emphasis on the topological structure and temporal fusion at the relational level, while DERP focuses on modeling the evolution of historical facts and periodicity perception at the entity level.

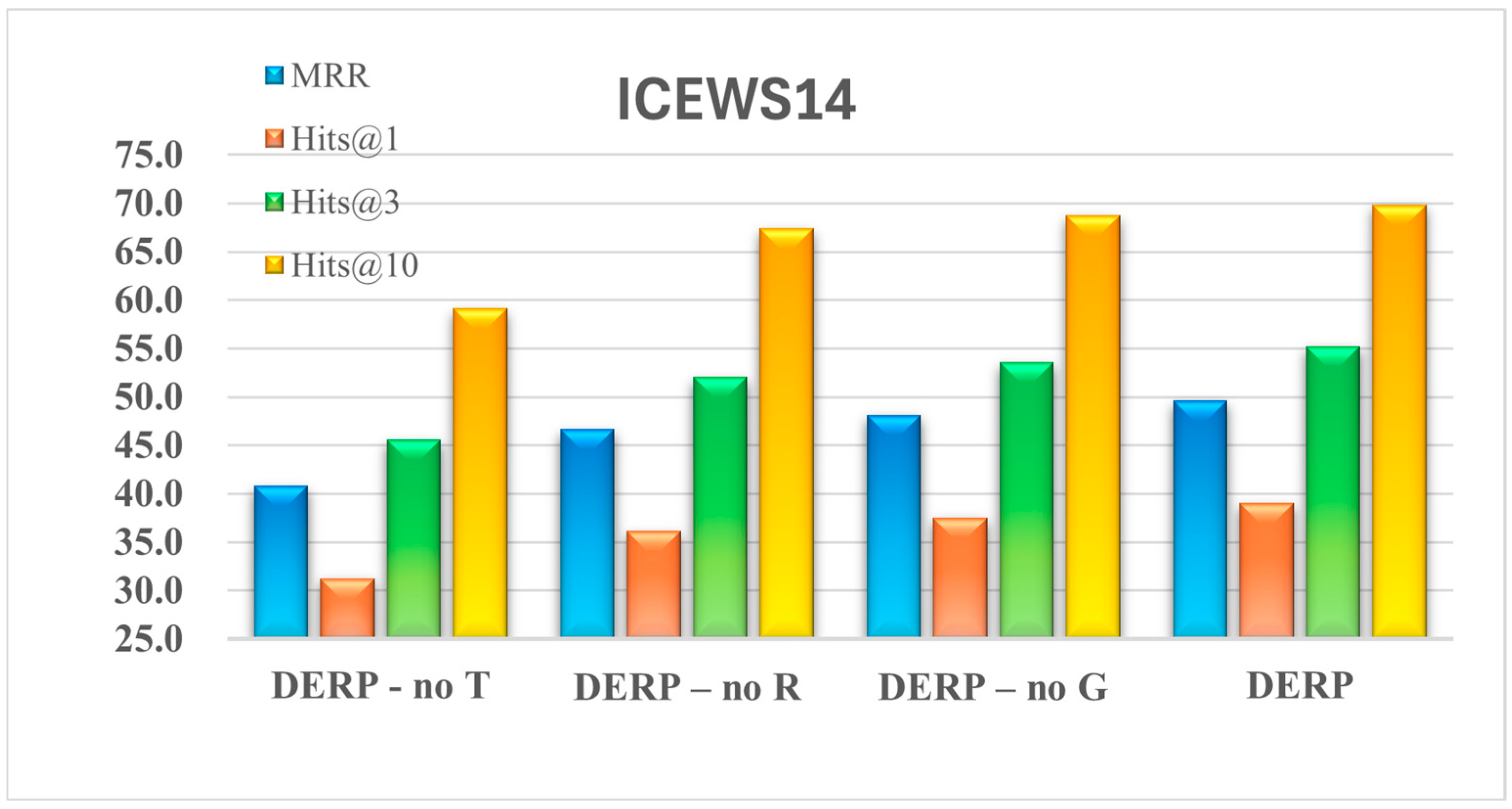

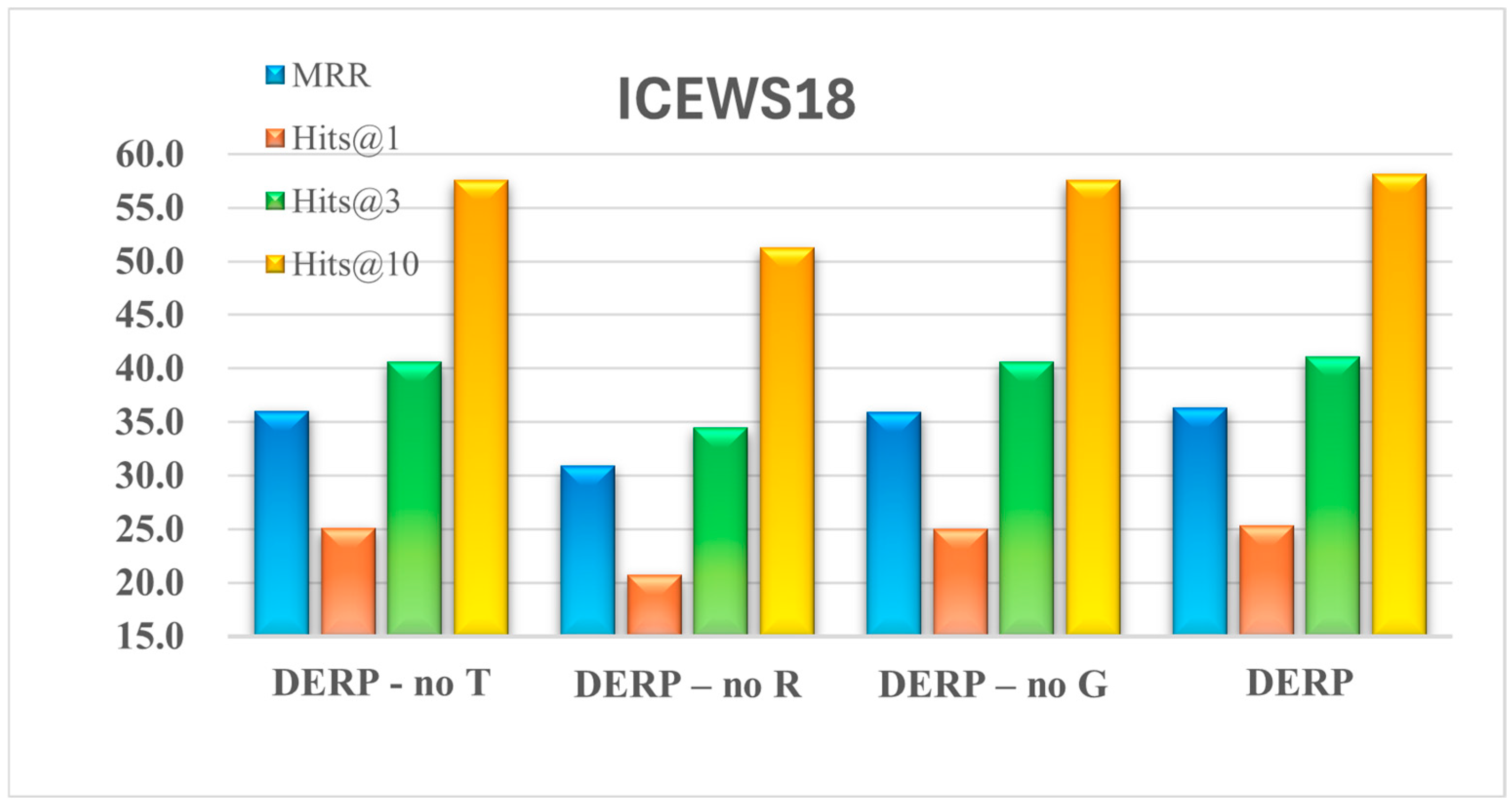

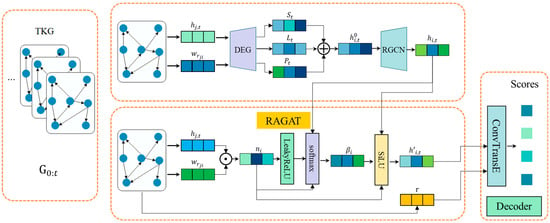

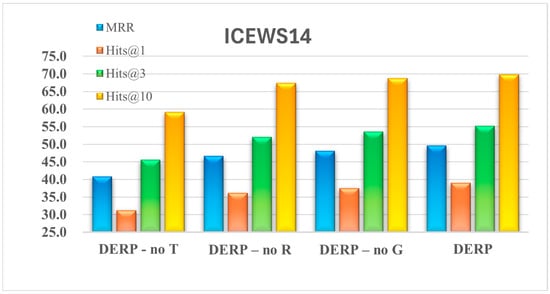

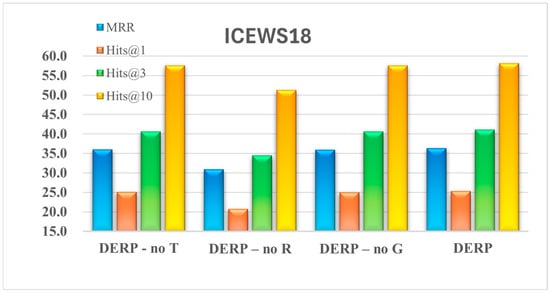

4.4. Ablation Study

To investigate the impact of entity embedding dynamics over time, the adaptive relation adjustment mechanism, and the RAGAT encoder incorporating dynamic relation weights on the DERP model, this paper compares different DERP variants based on four metrics: MRR and Hit@1, Hit@3, Hit@10. The variant DERP-no T removes features related to the temporal variation in entity embeddings—specifically, the long-term and short-term temporal embeddings as well as the positional time encodings—retaining only static entity features. DERP-no R replaces the adaptive relation adjustment mechanism with a fixed, uniform relation-weighting scheme, thereby eliminating dynamic relation weighting. DERP-no G removes the RAGAT encoder. Table 4 presents the results of variant models on the ICEWS14 and ICEWS18 datasets. As visually demonstrated in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the full DERP model significantly outperforms the DERP-no T, DERP-no R, and DERP-no G variants across all metrics, validating that its integration of temporally evolving entity embeddings, an adaptive relationship adjustment mechanism, and RAGAT enhances entity prediction capabilities.

Table 4.

Ablation experiments on ICEWS14 and ICEWS18. The highest value is bold.

Figure 3.

The performance of the ablation experiments on ICEWS14.

Figure 4.

The performance of the ablation experiments on ICEWS18.

Considering the impact of time-evolving features in entity embeddings, the results are shown in Table 4. From the perspective of the MRR metric, compared with DERP -no T, DERP improves by approximately 8.79% on ICEWS14 and about 0.32% on ICEWS18. Regarding Hits@3, compared with DERP -no T, DERP increases by around 9.67% on ICEWS14 and 0.45% on ICEWS18. It can be observed that the DERP -no T variant consistently underperforms DERP, demonstrating the necessity of incorporating time-evolving features of entity embeddings—namely, long-term and short-term temporal embeddings and temporal positional embeddings. Incorporating these features enriches the evolutionary representation of entities, facilitating subsequent encoding processes. Next, we analyze how removing dynamic embeddings significantly impacts the performance on ICEWS14 but has a lesser effect on ICEWS18. For ICEWS14: This dataset features a short time span (365 days) and sparse events (245.8 events per day on average), resulting in limited structural information within individual time snapshots. Consequently, the model must heavily rely on cross-temporal dynamic embeddings to capture the slow evolutionary patterns of entities and relationships over time. Removing dynamic embeddings effectively eliminates critical temporal clues for understanding event sequences, leading to a significant performance drop (−8.79%). For ICEWS18: This dataset features a longer time span (approximately 4 years) and extremely high fact density (1541.3 events per day). Each temporal snapshot contains abundant structural co-occurrence patterns, enabling static structural embeddings to learn rich, near-instantaneous relationship representations. Here, temporal evolution signals within event sequences become relatively weak compared to the robust static structural signals (i.e., low signal-to-noise ratio). Consequently, the information lost by removing dynamic embeddings can be partially compensated for by strong static embeddings, resulting in a negligible performance decline (−0.32%).

Impact of the adaptive relationship adjustment mechanism: In terms of MRR, compared with DERP -no R, DERP improves by approximately 2.93% on ICEWS14 and about 5.45% on ICEWS18. Regarding Hits@3, DERP surpasses DERP-no R by about 3.22% on ICEWS14 and 6.61% on ICEWS18. This indicates that in ICEWS18, where fact density is higher, some relations are repeatedly used with evolving semantics. If the same set of weights is applied to all relations, these “popular relations” dominate attention, making it harder to capture less frequent relations and resulting in increased errors. In contrast, relations in ICEWS14 exhibit more uniform usage. Hence, as data density and relational bias increase, the need for dynamic adjustment of relation weights over time becomes more pronounced for effective entity reasoning. These findings further underscore the critical role of relational information in the entity reasoning process.

Impact of the RAGAT encoder: The ablation results indicate that removing this module leads to a performance decline. Specifically, in terms of MRR, DERP outperforms DERP-no G by approximately 1.47% on ICEWS14 and 0.42% on ICEWS18. Regarding Hits@3, DERP achieves an improvement of about 3.22% on ICEWS14 and 6.61% on ICEWS18 compared to DERP-no G. These observations illustrate that in ICEWS14, which exhibits sparser neighborhood structures, the module substantially enhances the ranking of the first correctly predicted entity by precisely weighting neighbors according to relational semantics. In ICEWS18, with denser neighbor structures, it focuses on aggregating candidate neighbors of the same relation type, increasing the probability of correct entities entering the top three, but exhibits limited marginal gain for the ranking of the top position. The role of the RAGAT encoder exhibits certain differential characteristics as the graph density changes.

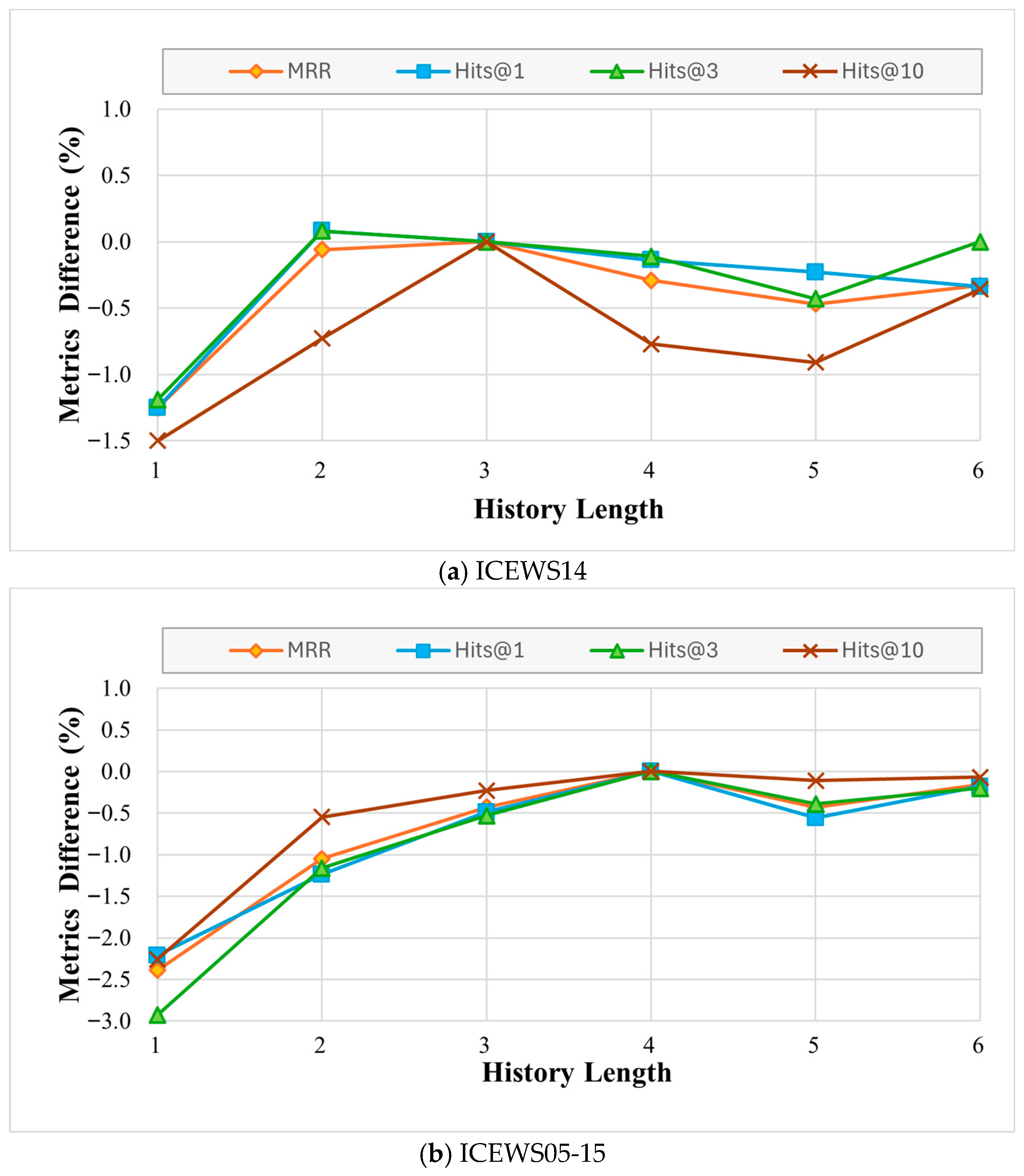

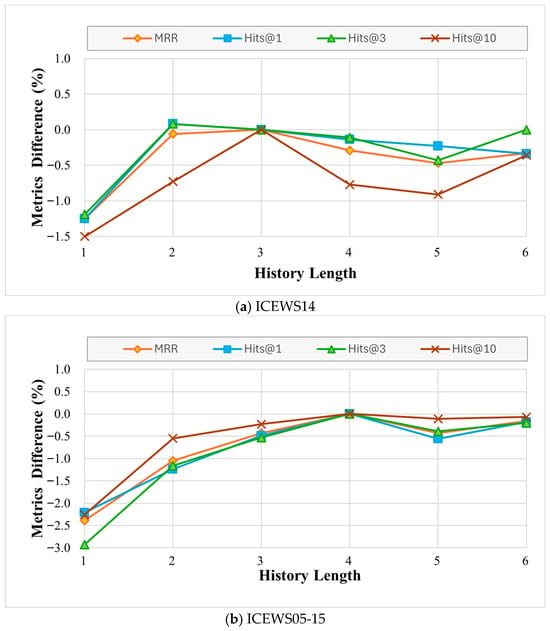

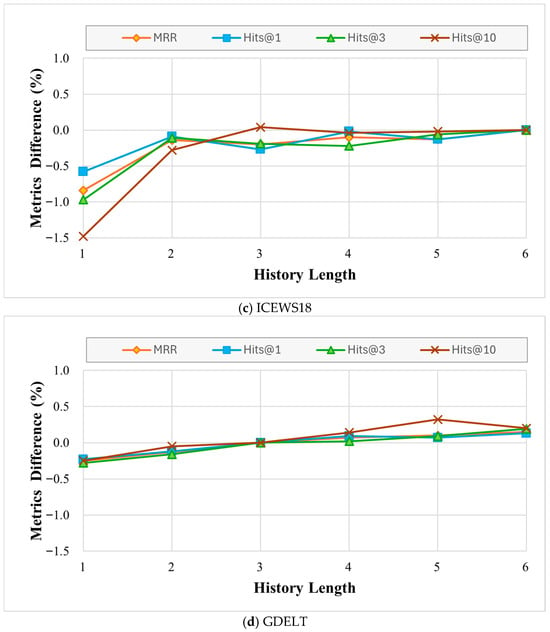

4.5. Hyper-Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

There are two hyperparameters, history length and , in DERP. We adjust the values of history length and respectively, to observe the performance change in DERP on ICEWS14, ICEWS05-15, ICEWS18 and GDELT datasets. The results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Evaluation indicators (%) change in DERP with the history lengths.

4.5.1. Impact of History Length

Experiments were carried out on datasets with varying historical lengths to investigate the impact of historical length on various datasets. The default value of the history length is 3. Figure 5 displays the percentage change in MRR across historical lengths from 1 to 6. Two primary observations are noted: (1) The MRR increases with historical length for the ICEWS18 and GDELT datasets. Performance can be considerably improved by extending the historical length for shorter lengths. However, for GDELT, the impact diminishes as the length increases, and improvements become marginal beyond a length of 3. Considering both performance and computational cost, the history length was set to 6 for ICEWS18 and 3 for GDELT. (2) Figure 5 illustrates that the ICEWS14 dataset performs best when the historical length is 3. On the other hand, performance declines as historical length increases. This indicates that incorporating longer history of this dataset, irrelevant information rather than beneficial signals, thereby degrading performance. The ICEWS05-15 dataset, except for its ideal historical length of 4, exhibits similar trends.

4.5.2. Impact of

To investigate the impact of hyperparameter on model performance, we conducted a controlled experiment. α is used to adjust the weight distribution between linear and quadratic trend terms and periodic terms in the temporal dynamic embedding. As shown in Table 5, the results consistently reveal a discernible pattern of performance variation with respect to .

Table 5.

Impact of hyperparameter on MRR (%). The highest value is bold.

Overall, when α ranges from 0.3 and 0.7, the MRR metric across all four datasets remains relatively stable, indicating that the DERP model is generally robust and not highly sensitive to moderate changes in . Specifically, peak performance is observed at for multiple datasets, and the model retains robust, stable performance within the interval of 0.4–0.6. Based on these findings, we set the default value of to 0.5 in subsequent experiments and applications to achieve optimal balance between trend and cyclical components.

4.6. Implementation Details

All the models are trained by using Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-8265U CPU @ 1.60 GHz 1.80 GHz and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090.Following prior research [27], the input dimension is set to 200. The batch size is set to the number of quadruples in each timestamp. We employ a 2-layer graph neural network with a dropout rate of 0.2. The Adam optimizer [40] is used for parameter learning with a learning rate of 0.001. For the ConvTransE, the hyperparameters are configured as follows: 50 channels, 2 input channels, a kernel size of 3, a dropout rate of 0.2, and a learning rate of 0.001. The historical length hyperparameter is set to 3 for the ICEWS14 and GDELT datasets, 6 for ICEWS18, and 4 for ICEWS05-15. For all datasets, hyperparameter is set to 0.5. The model is trained on the training set for a maximum of 30 epochs, and training is halted early if the validation performance shows no improvement over five consecutive epochs. The final model is evaluated on the test set. Table 6 illustrates the runtime and the number of parameters of the DERP model, evaluated across multiple datasets under default hyperparameter settings.

Table 6.

DERP running time, number of parameters, and memory usage.

4.7. Efficiency Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the practicality and computational efficiency of the DERP model, as shown in Table 7, we compared the performance metrics of DERP with xERTE, TITer, and TRCL across three dimensions: number of parameters, training time, and inference time. To achieve optimal results, xERTE employs a graph unfolding mechanism and a temporal relation graph attention layer, performing local representation aggregation for each step, resulting in longer training times and lower computational efficiency. Compared to xERTE, TITer reduces the number of parameters by at least half, but its complex temporal modeling capabilities and reinforcement learning framework led to lower computational efficiency. TRCL suffers from reduced computational efficiency due to its multi-module complex architecture. In summary, the DERP model achieves a favorable balance among computational efficiency, memory requirements, and model performance. Its fast training and inference speeds, coupled with moderate memory consumption, make it highly practical for processing large-scale temporal knowledge graphs.

Table 7.

Comparison of computational efficiency and number of parameters on ICEWS14.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper proposes a relation-aware reasoning model with dynamic evolution mechanisms. The model learns entity and relation embedding by capturing multi-faceted features of evolving facts. By integrating short-term and long-term temporal dynamics with positional time encoding, it dynamically revises entity representations to accurately reflect their states across different timestamps. A relational graph convolutional layer processes the graph-structured data to model complex entity interactions, while RAGAT aggregates neighbor information, substantially improving the capture of local structural patterns. A convolutional decoder finally produces the prediction scores. Comprehensive experiments on four public datasets demonstrate significant improvements over strong baselines on entity reasoning tasks, confirming the model’s effectiveness and superiority.

Future work will deeply integrate the cutting-edge ideas [41,42,43,44] and advance along two directions: On one hand, we will extend embedded learning to temporal hypergraphs capable of representing complex constraints, while introducing generative explanations to enhance interpretability; on the other hand, we will explore synergistic frameworks that combine the structured, temporal reasoning strengths of DERP with the vast factual knowledge and semantic understanding of large language models (LLMs), aiming to bridge structured temporal dynamics with unstructured textual context for richer knowledge representation. Building on this integrated architecture, we will conduct targeted application validation across diverse real-world domains—including urban agriculture, event prediction, and recommendation systems—thereby demonstrating the practical utility of this hybrid approach in addressing complex, dynamic scenarios. Through systematic benchmark evaluations, we will robustly demonstrate the broad adaptability and practical value of the DERP model, thereby contributing to the further development of temporal knowledge graphs.

6. Limitations

DERP has limited modeling capabilities for the more prevalent complex constraints and multi-party relationships in the real world, such as scenarios described by temporal hypergraphs. Moreover, DERP still adopts the traditional encoder–decoder framework structure with its overall design approach yet departs from this classical paradigm. Consequently, it has not explored more diversified and innovative approaches to model architecture. Although the model demonstrates superiority on benchmark public datasets, its practical utility has not been thoroughly examined in specific application scenarios, and a systematic error analysis has yet to be conducted. Therefore, its broader adaptability and practical value require further demonstration. Additionally, the model currently lacks effective reasoning and generalization capabilities for new entities not encountered during training. Future work could integrate Dynamic Time Warping and RAGAT with cutting-edge dynamic representation learning techniques to enhance the model’s capabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S. and Y.H.; methodology, P.S.; software, P.S.; validation, P.S.; formal analysis, P.S.; investigation, P.S.; resources, P.S.; data curation, P.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.S.; writing—review and editing, P.S. and Y.H.; visualization, P.S.; supervision, Y.H., P.S., X.Z. and R.Y.; project administration P.S.; funding acquisition, P.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, B.; Yih, W.; He, X.; Gao, J.; Deng, L. Embedding Entities and Relations for Learning and Inference in Knowledge Bases. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1412.6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trouillon, T.; Welbl, J.; Riedel, S. Complex Embeddings for Simple Link Prediction. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.06357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Deng, Z.-H.; Nie, J.-Y.; Tang, J. RotatE: Knowledge Graph Embedding by Relational Rotation in Complex Space. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1902.10197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dettmers, T.; Minervini, P.; Stenetorp, P.; Riedel, S. Convolutional 2D Knowledge Graph Embeddings. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.; Tang, Y.; Huang, J.; Bi, J.; He, X.; Zhou, B. End-to-End Structure-Aware Convolutional Networks for Knowledge Base Completion. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 January–1 February 2019; Volume 33, pp. 3060–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlichtkrull, M.; Kipf, T.N.; Bloem, P.; van den Berg, R.; Titov, I.; Welling, M. Modeling Relational Data with Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.06103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashishth, S.; Sanyal, S.; Nitin, V.; Talukdar, P. Composition-Based Multi-Relational Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1911.03082. [Google Scholar]

- Bordes, A.; Usunier, N.; Garcia-Duran, A.; Weston, J.; Yakhnenko, O. Translating Embeddings for Modeling Multi-Relational Data. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Bangkok, Thailand, 23–27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leblay, J.; Chekol, M.W. Deriving Validity Time in Knowledge Graph. In Proceedings of the Companion of The Web Conference 2018 on The Web Conference 2018—WWW ’18, Lyon, France, 23–27 April 2018; ACM Press: Lyon, France, 2018; pp. 1771–1776. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Tresp, V.; Daxberger, E. Embedding Models for Episodic Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.00228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tresp, V.; Ma, Y.; Baier, S.; Yang, Y. Embedding Learning for Declarative Memories. In The Semantic Web; Blomqvist, E., Maynard, D., Gangemi, A., Hoekstra, R., Hitzler, P., Hartig, O., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10249, pp. 202–216. ISBN 978-3-319-58067-8. [Google Scholar]

- Goel, R.; Kazemi, S.M.; Brubaker, M.; Poupart, P. Diachronic Embedding for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 3988–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, S.M.; Poole, D. SimplE Embedding for Link Prediction in Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacroix, T.; Obozinski, G.; Usunier, N. Tensor Decompositions for Temporal Knowledge Base Completion. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.04926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Ma, Y.; He, B.; Tresp, V. A Simple But Powerful Graph Encoder for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2112.07791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, G.; Meng, Z.; Han, Z.; Ding, Z.; Ma, Y.; Schubert, M.; Tresp, V.; Wattenhofer, R. TempCaps: A Capsule Network-Based Embedding Model for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Structured Prediction for NLP, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2022; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Ma, Y.; Chen, P.; Tresp, V. DyERNIE: Dynamic Evolution of Riemannian Manifold Embeddings for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, R.; Dai, H.; Wang, Y.; Song, L. Know-Evolve: Deep Temporal Reasoning for Dynamic Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 6–11 August 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, R.; Farajtabar, M.; Biswal, P.; Zha, H. DyRep: Learning Representations over Dynamic Graphs. In Proceedings of the International conference on learning representations, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6–9 May 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W.; Qu, M.; Jin, X.; Ren, X. Recurrent Event Network: Autoregressive Structure Inference over Temporal Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Günnemann, S.; Tresp, V. Graph Hawkes Neural Network for Forecasting on Temporal Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Ding, Z.; Ma, Y.; Gu, Y.; Tresp, V. Learning Neural Ordinary Equations for Forecasting Future Links on Temporal Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 8352–8364. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Chen, P.; Ma, Y.; Tresp, V. Explainable Subgraph Reasoning for Forecasting on Temporal Knowledge Graphs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2012.15537. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.; Zhong, J.; Ma, Y.; Han, Z.; He, K. TimeTraveler: Reinforcement Learning for Temporal Knowledge Graph Forecasting. In Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Jin, X.; Li, W.; Guan, S.; Guo, J.; Shen, H.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, X. Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning Based on Evolutional Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual, Montréal, QC, Canada, 11–15 July 2021; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 408–417. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hildebrandt, M.; Joblin, M.; Tresp, V. TLogic: Temporal Logical Rules for Explainable Link Forecasting on Temporal Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtually, 22 February–1 March 2022; Volume 36, pp. 4120–4127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Guan, S.; Jin, X.; Peng, W.; Lyu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, L.; Li, W.; Guo, J.; Cheng, X. Complex Evolutional Pattern Learning for Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, 22–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, K.; Han, S.C.; Poon, J. Re-Temp: Relation-Aware Temporal Representation Learning for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP, Singapore, 6–10 December 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; He, B.; Ma, Y.; Han, Z.; Tresp, V. Learning Meta Representations of One-Shot Relations for Temporal Knowledge Graph Link Prediction. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2205.10621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ou, J.; Xu, H.; Fu, L. Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning with Historical Contrastive Learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference On Artificial Intelligence, Washington DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; Volume 37, pp. 4765–4773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Hasikin, K.; Khairuddin, A.S.M.; Liu, M.; Zhao, X. A Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning Model Based on Recurrent Encoding and Contrastive Learning. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2025, 11, e2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Tresp, V. Time-Dependent Entity Embedding Is Not All You Need: A Re-Evaluation of Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion Models under a Unified Framework. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online and Punta Cana, Dominican Republic, 7–11 November 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 8104–8118. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, L.; Chai, D.; Zhu, L. RLAT: Multi-Hop Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning Based on Reinforcement Learning and Attention Mechanism. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 269, 110514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- García-Durán, A.; Dumančić, S.; Niepert, M. Learning Sequence Encoders for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Brussels, Belgium, 31 October–4 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Ao, X.; Zhuang, F.; Xu, Y.; He, Q. Along the Time: Timeline-Traced Embedding for Temporal Knowledge Graph Completion. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–21 October 2022; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 2529–2538. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, A.; Ouyang, G.; Huang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xie, H. RLGNet: Repeating-Local-Global History Network for Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.00586. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K.; Meng, L.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Tu, W.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Liu, X. Learn from Relational Correlations and Periodic Events for Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–27 July 2023; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1559–1568. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Hui, B.; Mu, C.; Tian, L. Learning Multi-Graph Structure for Temporal Knowledge Graph Reasoning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.P.; Saadi, A.A.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. Encoding Higher-Order Logic in Spatio-Temporal Hypergraphs for Neuro-Symbolic Learning. In Proceedings of the ESANN 2025 Proceedings, Bruges, Belgium, 23–25 April 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyan, B.P.; Singh, T.P.; Tomar, R.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. NeSyKHG: Neuro-Symbolic Knowledge Hypergraphs. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 235, 1278–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.P.; Singh, T.P.; Tomar, R.; Meraihi, Y.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. A Monadic Second-Order Temporal Logic Framework for Hypergraphs. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 22081–22118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, B.P.; Tomar, R.; Singh, T.P.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. UrbanAgriKG: A Knowledge Graph on Urban Agriculture and Its Embeddings. Open Agric. 2024, 9, 20220265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.