Abstract

Mobile crowd computing (MCdC) leverages the collective computational resources of nearby mobile devices to execute complex tasks without relying on remote cloud infrastructure. However, existing MCdC systems struggle with device heterogeneity and complex application dependencies, often leading to inefficient resource utilization and poor scalability. This paper presents Honeybee-Tx, a novel dependency-aware work stealing framework designed for heterogeneous mobile device clusters. The framework introduces three key contributions: (1) capability-aware job selection that matches computational tasks to device capabilities through lightweight profiling and dynamic scoring, (2) static dependency-aware work stealing that respects predefined task dependencies while maintaining decentralized execution, and (3) staged result transfers that minimize communication overhead by selectively transmitting intermediate results. We evaluate Honeybee-Tx using two applications: Human Activity Recognition (HAR) for sensor analytics and multi-camera video processing for compute-intensive workflows. The experimental results on five heterogeneous Android devices (OnePlus 5T, Pixel 6 Pro, and Pixel 7) demonstrate performance improvements over monolithic execution. For HAR workloads, Honeybee-Tx achieves up to 4.72× speed-up while reducing per-device energy consumption by 63% (from 1.5% to 0.56% battery usage). For video processing tasks, the framework delivers 2.06× speed-up compared to monolithic execution, with 51.4% energy reduction and 71.6% memory savings, while generating 42% less network traffic than non-dependency-aware approaches. These results demonstrate that Honeybee-Tx successfully addresses key challenges in heterogeneous MCdC environments, enabling efficient execution of dependency-aware applications across diverse mobile device capabilities. The framework provides a practical foundation for collaborative mobile computing applications in scenarios where cloud connectivity is limited or unavailable.

1. Introduction

The evolution of computing devices has dramatically increased their capabilities in recent decades [1]. Although cloud computing (CC) provides cost-effective solutions for on-demand resource scaling [2,3], its reliance on remote servers introduces challenges related to latency, data integrity, and dependence on reliable internet connections. Edge computing (EC) mitigates these issues by bringing computational and storage resources closer to the data source. However, the dynamic nature of EC environments, particularly with mobile devices, can lead to intermittent connectivity and potential data loss.

Smartphones, as ubiquitous data producers and processors, exemplify this challenge. Despite their growing capabilities, resource-intensive applications strain these devices. Mobile cloud computing (MCC) offers a solution by off-loading tasks to the cloud [4]. However, this approach is not a panacea. Even with MCC, modern smartphones, equipped with powerful processors and specialized hardware [5], may still face limitations when handling demanding tasks such as 4K video editing, 3D rendering, or antivirus software [6], especially when connectivity is limited or latency is critical. This trade-off between resource availability and latency is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the trade-off between resource proximity and latency.

To overcome these constraints, mobile crowd computing (MCdC) extends the concept of edge computing by emphasizing mutual resource sharing among nearby mobile devices [7]. This approach leverages the widespread presence of smartphones, tablets, and wearable technologies equipped with various sensors and significant computational capabilities. MCdC enables these devices to collaboratively participate in solving complex tasks or improving application efficiency without solely relying on distant cloud servers or individual device capabilities. The core principle behind MCdC is to create a decentralized network of mobile devices that can dynamically share computing power, storage, and data to achieve common goals.

Despite significant progress in MCdC research [8,9,10,11,12], key challenges remain, particularly in managing heterogeneous devices and handling complex task dependencies in dynamic environments.

1.1. Research Challenge

How can MCdC systems efficiently leverage a diverse and dynamic set of edge devices, including severely resource-constrained nodes, to execute inter-dependent tasks while achieving performance gains in the face of frequent device churn, variable connectivity, and volatile resource availability?

Challenge significance and rationale:

- Extreme heterogeneity: Smartphones, tablets, and wearable and low-cost IoT nodes vary by two orders of magnitude in CPU speed, memory, and battery life [13]. Naive work distribution either overloads weak devices or under-utilizes capable ones.

- Task inter-dependency: Real-world mobile workloads (activity-recognition, on-board ML inference, and AR/VR pipelines) form Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs), not self-aware-parallel bags of tasks [14]. In such DAG-based workloads, a single, stalled edge representing a dependency between tasks can block the execution of all tasks that depend on it downstream.

- High churn: Empirical traces show median session times below 7 min for opportunistic Bluetooth/Wi-Fi Direct clusters; any robust scheduler must expect mid-task departures [15].

- Resource variability: Battery-aware OS governors, background apps, and radio state changes mean that a “fast” device at time t0 may be throttled or offline at t1 [16].

This combination places MCdC beyond the reach of conventional edge schedulers, which typically assume either homogeneous hardware or stable membership. An end-to-end solution must (i) detect and classify device capability on the fly, (ii) map fine-grained dependent tasks onto the right devices, and (iii) adapt to device disconnections and connections without central infrastructure.

1.2. Proposed Approach and Contributions

To address the above challenges, we propose Honeybee-Tx, an extension of the Honeybee framework [17,18]. Honeybee is an open-source Android implementation of a work stealing model for MCdC, notable for its proactive off-loading, automatic load balancing, and fault-tolerant mechanisms.

As summarized in Table 1, the Honeybee project has evolved through several research streams, each targeting a specific challenge in MCdC. The Honeybee-T stream introduced sequential dependency awareness [19], the Honeybee-RS stream focused on result reliability [20], and the BTVMCC stream explored blockchain-based trust [21]. This paper builds upon and extends the Honeybee-T stream by introducing support for generalized, non-sequential dependencies, true device heterogeneity, and adaptive resilience.

Table 1.

Key components and contributions of Honeybee frameworks.

The specific contributions of this paper are the following:

- C1:

- Capability-aware job stealing: We introduce a mechanism that matches computational jobs to the most suitable mobile devices. Through a lightweight profiling handshake and a dynamic scoring system, the framework ensures that powerful devices are assigned intensive jobs while preventing resource-constrained devices from being overloaded.

- C2:

- Generalized DAG work stealing: We extend the classical work stealing model to support applications with complex task dependencies, represented as a static Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG). This allows the framework to correctly orchestrate multi-stage workflows in a decentralized manner, ensuring jobs are only executed after their prerequisites are met.

- C3:

- Resilience via staged result management: To ensure robustness in volatile mobile environments, we introduce a resilience mechanism featuring adaptive checkpointing and staged result transfers. By selectively transmitting intermediate results based on job criticality and worker reliability, this approach minimizes results loss from device disconnections and significantly reduces recovery time compared to a full restart.

We implement and evaluate our framework, Honeybee-Tx, on five heterogeneous Android devices using two demanding applications. Our results demonstrate that these contributions lead to significant performance gains, achieving up to 4.72× speed-up on sensor analytics workloads and a 2.06× speed-up on complex video processing pipelines, all while substantially reducing device energy and memory consumption.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we discuss the evolution of edge computing and advances in MCdC. Section 3 reviews related work in MCdC, focusing on contributions related to the challenges discussed in Section 1. Section 4 outlines our research methodology, discusses the system architecture, and introduces the Honeybee-Tx framework and its mechanisms. Section 5 discusses how developers can leverage the framework APIs and presents the key details on the application programming model. In Section 6, we introduce the Human Activity Recognition and Multi-Camera Video Encoding applications employed to validate the mechanisms. Finally, in Section 7 and Section 8, we discuss the experimental results and propose future research directions.

2. Background

Edge and mobile computing have evolved from centralized cloud execution to edge nodes and, increasingly, to the devices generating the data. This section positions Mobile Crowd Computing (MCdC) within that trajectory, distinguishes it from earlier paradigms, and outlines the technical challenges motivating this work.

2.1. Key Concepts

- Cloud computing (CC): Elastic resources hosted in data centers and accessed over the internet [2]. Centralized control, virtually unlimited resources, and high latency (50–200 ms) for mobile users [22].

- Edge computing (EC): Infrastructure nodes are placed near the access network to reduce latency [7]. Typical deployment: base stations and roadside units, reducing latency to 10–50 ms [23].

- Mobile edge computing (MEC): Telecom-oriented EC variant colocated with radio access equipment to serve nearby mobile devices [24]. Requires operator infrastructure investment [23].

- Mobile crowd computing (MCdC): A decentralized paradigm leveraging opportunistic device-to-device (D2D) connectivity to form ephemeral compute clusters without infrastructure dependency [25,26]. Achieves sub-10 ms latency through direct device communication [27].

2.2. From Cloud to Crowd

Early mobile off-loading systems such as MAUI [28] and CloneCloud [29] overcame handset limitations by leveraging the cloud, but they suffered from wide-area latency and back-haul congestion. MEC reduced round-trip time by hosting services at the network edge [30], yet it remained dependent on operator-owned infrastructure. MCdC removes that dependency altogether: as handset processors now rival low-power servers, the collective capacity of the crowd has become a viable alternative to fixed edge nodes [31].

2.3. MCdC vs. MEC

MCdC differs from MEC in governance (centrally managed MEC vs. user-owned MCdC resources coordinated opportunistically [26]), topology (fixed MEC vs. ephemeral MCdC groups forming and dissolving as users move [31]), and resource stability (provisioned, mains-powered MEC servers vs. battery-dependent MCdC devices subject to thermal throttling and user activity [8]).

2.4. Research Motivation

Consider a large conference where multiple attendees want real-time transcription and translation of presentations. Each smartphone captures audio that, while varying slightly due to position and noise, represents the same source content. With conference Wi-Fi overloaded and cellular data congested, an MCdC application forms a collaborative cluster over device-to-device links. The framework distributes the speech processing pipeline—noise reduction, speech recognition, and translation—across nearby devices. By combining multiple audio perspectives and pooling computational resources, the system achieves more accurate transcription than any single device could provide, delivering synchronized, translated captions to each participant within seconds. Prototype studies such as DroidCluster demonstrate the feasibility of smartphone clusters for multimedia workloads [32]. This example illustrates MCdC’s potential for low-latency collaboration, bandwidth savings, and privacy preservation while hinting at the open problems of heterogeneity, churn, and verification addressed in this work.

The evolution from infrastructure-bound CC to opportunistic MCdC introduces fundamental technical challenges that existing edge computing solutions cannot adequately address. The primary challenge lies in scheduling and resource allocation—determining how to efficiently distribute tasks across heterogeneous devices with varying capabilities while respecting task dependencies and deadlines. This is compounded by fault tolerance concerns, as the system must manage frequent device disconnections while ensuring task completion in dynamic mobile environments. Furthermore, energy and communication efficiency remain critical, requiring careful minimization of battery drain and network overhead in resource-constrained settings where excessive energy consumption directly discourages user participation.

These challenges have prompted diverse research approaches, from centralized orchestration frameworks to fully decentralized work stealing algorithms. The following Section 3 reviews existing solutions across these aspects, identifying gaps that motivate our proposed Honeybee-Tx framework. Specifically, we examine how current approaches handle device heterogeneity, manage task dependencies, ensure task completion under churn, and enhance resource utilization in infrastructure-free environments.

3. Related Work

The current literature on computation off-loading strategies in MEC evaluates schemes mainly along three performance fronts: latency, energy consumption, and load balance. Lower latency improves task-completion rates and user quality of experience [28,30]; reduced energy use prolongs device operating life-a primary constraint for battery-powered devices [33]; and load balancing prevents edge servers from becoming hotspots or idling, thereby increasing overall resource utilization [8]. Because these objectives often conflict, recent studies frame off-loading as a multi-objective optimization problem and search the Pareto frontier with convex relaxation, heuristic search, or deep reinforcement learning (DRL) [34,35]. Our review adopts this metric triad while extending the review to MCdC-specific concerns, such as device mobility, effective task assignment mechanisms when dependencies exist between two or more tasks, resources, and volatility.

3.1. Fundamental Collaborative Frameworks

Early work on infrastructure-less mobile collaboration investigated whether nearby devices could reliably share computation. Serendipity [36] was one of the first prototypes to off-load small, independent tasks to proximate smartphones encountered opportunistically. Experiments with mobility traces showed measurable reductions in execution time and energy use. However, it assumed sporadic connectivity and lacked support for inter-task dependencies or completion guarantees, limiting applicability to complex workflows. Circa [37] introduced structured P2P collaboration with fairness-based static task distribution, effective for “embarrassingly parallel” jobs but unable to adapt to churn or performance variation. Honeybee [17] advanced this paradigm with decentralized work stealing: idle workers (peer devices) pull jobs from a delegator’s pool, enabling inherent load balancing and fault tolerance. Its open-source implementation [18] has become a de facto MCdC testbed, later adapted for drones [38], blockchain-based trust [21], and worker result validation [20]. Recent studies treat the vast capability spread among edge peers as a first-class scheduling signal rather than noise. Asteroid [13] partitions pipelines across CPUs, GPUs, and NPUs for up to 12× speed-ups but relies on a central planner. Adaptive Asynchronous Work Stealing (AAWS) adapts victim selection and task granularity dynamically via per-node performance counters, achieving 10% throughput gains on 400 nodes [39]. Hybrid approaches, such as CASINO [40], collaboratively combine mobile and cloud resources via a centralized scheduler that considers device capabilities and DAGs. While effective, its reliance on the global state limits applicability in fully decentralized MCdC scenarios. These frameworks illustrate a spectrum from decentralized P2P (Circa and Honeybee) to mobile–cloud hybrids (CASINO), highlighting trade-offs between decentralization and scheduling complexity.

3.2. Task Dependency Management

Many modern applications, from video processing to distributed ML, are structured as DAGs, requiring tasks to execute in a specific order. Early MCdC frameworks, such as Honeybee [17] and Circa [37], supported only independent tasks. An extension to Honeybee later enabled simple sequential chains via modified work stealing [19], but it could not handle more complex, non-linear dependencies found in general DAGs. In contrast, the MEC literature, where a base-station or cloudlet orchestrates the whole system, supports advanced DAG scheduling. Examples include HEFT-style heuristics for joint task placement and CPU tuning [41], reinforcement learning for hierarchical off-loading [42], and formal optimization for sequential dependencies [43]. Recent work, such as SDTS [14], shows that even lightweight list schedulers can support DAG precedences on heterogeneous fog clusters, but these approaches assume a global controller, making them unsuitable for ad-hoc MCdC.

Hence, a gap remains between centralized DAG scheduling in MEC and the limited dependency support in decentralized P2P systems. Our work addresses this by proposing a decentralized, DAG-aware scheduling mechanism within a P2P work stealing framework.

3.3. Dynamic Task Off-Loading and Hybrid Architectures

MCdC environments are intrinsically volatile: connectivity fluctuates, devices join and leave, and battery levels drop unpredictably, making static off-loading plans obsolete. Honeybee exemplifies a fully decentralized response to this volatility. Idle workers proactively ’pull’ work, so faster devices absorb more load, while departing devices simply stop stealing [17,25]. This organic load balancing remains robust even when every node is mobile. M-TEC [44] schedules DAG applications across devices, roadside edge, and cloud, reducing latency by 8%, but relies on a middle-tier controller and cannot tolerate spontaneous peer loss. Hybrid designs extend this idea. Ref. [45] extends Honeybee into a three-tier edge–fog–cloud architecture: a smartphone delegator can simultaneously off-load jobs to nearby peers, fog servers, or to cloud VMs, based on load. Experiments show speed-ups of up to 7.6× while preserving the automatic load balancing nature of work stealing. AI-driven approaches offer increased responsiveness. DRL models sense bandwidth, queue length, and mobility to decide per-task placement. For example, Ref. [42] used DDPG to map DAG nodes across vehicle–edge–cloud tiers, decreasing completion time by 13%, while Ref. [46] jointly minimized deadline violations and energy. However, these methods assume a global view, unlike work stealing, which offers decentralized reactivity but only via greedy heuristics, whereas DRL delivers foresight but assumes a central observer.

3.4. Energy-Aware Scheduling and Load Balancing

Energy efficiency is critical for battery-powered devices, which constitute the majority of MCdC nodes. While off-loading saves CPU cycles, data transmission incurs energy. Hence, MCdC frameworks need to balance both factors. MAUI extended device battery life by profiling each method at run time and off-loading only when the projected energy savings exceeded the radio cost [28]. Follow-up measurements confirmed that short-range Wi-Fi Direct links consume markedly less energy per bit than LTE, strengthening the case for local peer-to-peer execution [47]. In MEC, energy is mainly addressed via centralized optimization. DRL-E2D [48] learns policies to minimize energy while meeting deadlines, while Ref. [49] formulates off-loading as a multi-agent game with provable convergence to energy-efficient equilibria. Battery health is explicitly addressed in [50], which prioritizes off-loading for low-battery devices to prolong collective uptime.

Conversely, fully decentralized frameworks, such as Honeybee, achieve only implicit energy balancing: workers steal until they finish or leave the session [17]. A phone at 5% charge can still steal jobs, drain out, and damage the efforts. A lightweight, battery-aware method for MCdC remains an open challenge.

3.5. Fault Tolerance in Volatile Peer-to-Peer Environments

MCdC environments are inherently volatile. Hence, an MCdC framework must have fault tolerance methods to avoid losing the entire computation if/when failures happen. Task replication is a common method [51,52], but its high cost of redundant resource consumption makes it impractical for mobile devices. Partial off-loading methods such as [53] reduce overhead by routing intermediate results along alternative paths. Their findings support our decision to stage bulky intermediates (e.g., FFT coefficients) until the final stage, saving up to 38% radio energy in our prototype. Mutable checkpoints [54] further limit rollback overhead by retaining interim state in RAM. The original Honeybee framework [17] offers a lightweight, reactive method. Each task is split into many small jobs, and in case of worker failure, the allocated jobs are simply reassigned to the delegator’s job pool. While resilient, it is not proactive; failure during a long-running job can stall the critical path in latency-sensitive pipelines. Recent work, such as UNION [55] models, uses reliability to apply selective replication, balancing reliability and overhead, but at the cost of increased complexity and infrastructure reliance.

In this paper, we enhance the original Honeybee’s reactive fault tolerance via lightweight checkpointing for long-running tasks and selective replication for critical-path jobs.

3.6. Critical Synthesis and Research Gaps

While substantial progress has been made in mobile collaborative computing, as summarized in Table 2, there remains critical research gaps for fully decentralized MCdC:

- Reliance on centralized control: Many advanced algorithms for DAG scheduling, dynamic adaptation, and energy optimization depend on a centralized controller with a global view of the system [40,42,56]. This model is incompatible with truly ad-hoc mobile environments.

- Limited support for complex applications: Existing P2P frameworks are largely restricted to independent or simple sequential tasks [17,37]. There is a lack of solutions for executing applications with general DAG-based dependencies in a fully decentralized manner.

- True heterogeneity compatibility: Current solutions do not adequately support true device heterogeneity. They are often designed for homogeneous or narrowly defined device capabilities, failing to incorporate the diverse range of computational resources-from high-performance smartphones to low-power sensors-available in a dynamic mobile environment. This prevents the system from fully leveraging the collective power of all proximate devices.

These gaps motivate our work on extending decentralized work stealing to support static DAG dependencies, heterogeneous devices, and energy-aware stealing mechanisms. The next section presents our framework design.

Table 2.

Summary of the literature on decentralized MCdC approaches.

Table 2.

Summary of the literature on decentralized MCdC approaches.

| Approach (Year) | Collaboration Scope | Scheduling Approach/ Dep. Handling | Dynamic Adaptation | Energy-Awareness | Fault Tolerance | Key Limitations for Fully Decentralized MCdC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAUI [28] (2010) | Mobile → Cloud | Centralized decision/ No explicit dep. | Static | Yes (code profiling) | No | Purely centralized off-loading to infrastructure |

| CloneCloud [29] (2011) | Mobile → Cloud (VM migration) | Centralized decision/ Basic object dep. | Static | Yes (VM state) | Limited (VM state consistency) | Centralized VM approach, not P2P task sharing |

| Serendipity [36] (2012) | Local devices (P2P) | Opportunistic off-load/ No (independent tasks) | Limited adaptivity | Implicit (local exec saves energy) | Limited (retry on disconnect) | Required intermittent connectivity, no complex dep. or guarantees |

| Circa [37] (2018) | Local devices (P2P, no infra) | Decentralized (fairness-based allocation)/No (independent tasks) | Static allocation | Implicit (local exec saves energy) | Limited (initial reliable peer selection) | Restricted to independent tasks, static allocation |

| Honeybee [17] (2016) | Local devices (P2P mesh) | Decentralized work stealing/Partial (sequential via extension [19]) | Yes (proactive work stealing) | No (focus on performance) | Yes (reassign on disconnect) | Limited dependency support, no explicit energy optimization |

| CASINO [40] (2018) | Mobile + Cloud (Hybrid) | Centralized heuristic scheduler/Yes (job/device graph) | Limited (batch schedule) | Partial (device battery profile) | No (assumes stable execution) | Centralized control, assumes stable resources |

| Centralized heuristic [42] (2022) | Vehicular + Edge + Cloud | Centralized RL scheduler/Yes (DAG model) | Yes (dynamic RL decisions) | No (latency primary focus) | No (no churn modeled) | Centralized control point (edge/cloud), specific IoV domain |

| Centralized RL scheduler [41] (2020) | Mobile + Edge | Centralized heuristic (dependency-aware HEFT variant)/Yes (general DAG) | Static plan, regenerated on topology change | No (energy not modelled) | No | Central controller assumed; edge helpers must stay reachable |

| UNION [55] (2023) | Opportunistic devices + Edge | Distributed (probabilistic + reactive)/Yes (reliability model influences schedule) | Yes (proactive & reactive) | No (focus on reliability) | Yes (replication, migration) | Dependency handling tied to reliability, not general DAG optimization |

| [45] (2025) | Edge + Fog + Cloud (3-tier) | Extended Honeybee work stealing/No (independent jobs) | Yes (stealing across tiers) | No (focus on throughput) | Yes (inherits Honeybee mechanisms) | Focus on independent jobs across tiers; general task graphs not fully supported |

4. The Honeybee-Tx Framework

This section introduces Honeybee-Tx, our proposed framework for opportunistic MCdC. Motivated by the research challenges identified in Section 1.1, Honeybee-Tx extends and advances the Honeybee framework streams by addressing critical gaps in prior designs. Table 3 introduces and summarizes the symbols and key terms used in the section.

Table 3.

Summary of key symbols in the Honeybee-Tx framework.

Honeybee-Tx addresses MCdC challenges through three integrated contributions that fulfill two overarching design objectives: Managing extreme heterogeneity is achieved through capability-aware job stealing (C1), which matches jobs to devices according to computational capacity. Ensuring resilience despite volatility relies on two complementary mechanisms: generalized DAG work stealing (C2), which handles complex inter- and intra-task dependencies, and resilience via staged result management, which preserves progress even under device disconnections (C3).

Table 4 details how each contribution advances beyond existing approaches. The following subsections examine each innovation in depth.

Table 4.

Core contributions and innovations of the Honeybee-Tx framework.

4.1. System Architecture

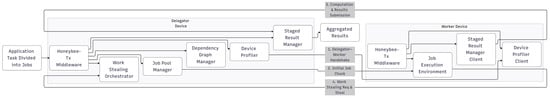

The Honeybee-Tx framework is built on a delegator–worker architectural model, enabling opportunistic collaboration among heterogeneous mobile devices. As illustrated in Figure 2, the delegator orchestrates the computation, while workers contribute resources by executing assigned tasks.

Figure 2.

Honeybee-Tx architecture diagram showing the four-stage interaction flow between the delegator and worker devices.

The operational flow begins with a Delegator–Worker Handshake, where the delegator’s Device Profiler assesses a worker’s capabilities, including its CPU, memory, and energy status, to inform scheduling decisions. On the delegator, the Job Pool Manager decomposes the main application task into smaller, computable jobs, which are managed in a central job pool. The dependencies between these jobs are represented as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) maintained by the Dependency Graph Manager, ensuring the correct execution order.

The core of the framework is a worker-initiated, dynamic process. When idle, a worker sends a STEAL_REQ packet to the delegator’s Work Stealing Orchestrator. The orchestrator evaluates this request by verifying that all of a job’s prerequisites in the DAG are met and that the worker’s capabilities match the job’s requirements. If approved, the orchestrator sends a dynamically sized chunk (bundle of jobs) to the worker.

During computation, the worker’s Staged Result Manager ensures resilience by incrementally sending partial results back to the delegator at defined checkpoints. This preserves progress against unexpected device disconnections and allows the delegator to aggregate the final results upon job completion. This continuous, worker-initiated cycle of stealing, computing, and reporting results provides adaptive load balancing throughout the collaborative session.

4.2. Core Mechanism 1: Heterogeneity-Aware Job Stealing

Honeybee-Tx introduces a capability-aware handshake during device discovery to profile worker resources. This enables dynamic, capability- and availability-driven job stealing, in contrast to static or semi-static scheduling in conventional MCdC frameworks.

4.2.1. Device Capability Assessment

The device capability assessment process consolidates multiple performance-related metrics into a singular, unified capability score, denoted as for device i. This score is computed as a weighted sum:

where , , and represent the normalized scores (scaled to ) for CPU performance, memory availability, and energy status of device i, respectively.

The individual scores are computed through distinct metrics tailored to each resource dimension. The is derived from a combination of CPU frequency, core count, and current utilization levels, providing a comprehensive assessment of processing capability. The represents the ratio of available to total memory while accounting for system reserves, ensuring that the score reflects actual usable memory rather than theoretical capacity. The incorporates battery level weighted by power consumption rate and charging status, offering a nuanced view of the device’s energy availability that considers both current state and consumption patterns.

The weighting parameters (with , all non-negative) can be configured to align with specific application requirements or system objectives, such as prioritizing energy efficiency () or execution speed (). This assessment is initially performed during the handshake protocol and is subsequently updated periodically (every 30 s by default) or in response to significant state changes (>20% change in any component score) to accurately reflect the dynamic conditions of each device.

4.2.2. Capability-Aware Job Selection

Honeybee-Tx ensures efficiency in heterogeneous MCdC settings through its capability-aware job-selection procedure. It is invoked in two places: (1) during initial delegation and (2) whenever a delegator evaluates a STEAL_REQ:

In both cases, the routine must select, from a candidate set , a job whose demand vector matches the worker’s capability vector . Algorithm 1 presents the refined logic. Weights mirror those of (1) and are updated every k seconds by the delegator’s Adaptation Thread to favor either energy longevity () or makespan ().

Algorithm 1 treats matching as a weighted resource ratio score between the job’s demand vector and the worker’s capability vector . The score (Line 5) increases when a device has surplus resources in dimensions that the job consumes heavily; the tunable weights bias the match towards either performance () or energy longevity (). Only jobs whose score exceeds a global accept threshold are considered, enforcing a quality floor and avoiding steals that would inevitably timeout.

| Algorithm 1 Capability–aware job selection. |

| Require: Candidate set , worker profile , minimum score Ensure: Best matching job or Null

|

Complexity

The routine is in time complexity, where is the number of candidate Jobs. The space complexity is , as it only maintains a constant number of variables, regardless of input size. The overhead is negligible because in practice-candidate sets are filtered by dependency satisfaction and state checks, typically with , even for large job pools with jobs. Only jobs in the READY state with satisfied dependencies enter the candidate pool, dramatically reducing the search space.

Performance Considerations

Empirical analysis shows that this capability-aware job-selection algorithm completes within 1–2 ms on typical mobile devices, ensuring responsiveness for rapid job allocation.

4.3. Core Mechanism 2: Generalized DAG Work Stealing

Honeybee-Tx employs a dependency-aware work stealing mechanism that allows idle workers to opportunistically acquire jobs from the delegator while strictly enforcing DAG constraints to preserve workflow integrity. Algorithm 2 outlines the delegator’s process for handling steal requests.

| Algorithm 2 Dependency and capability-aware job stealing on delegator. |

|

The work stealing mechanism in Honeybee-Tx includes the following features:

- Generalized DAG-aware work stealing: Our work stealing algorithm differs from classical work stealing algorithms, such as [57], which are designed for fully strict computations, and dependencies are limited to parent–child relationships in a structured tree. They do not support general task graphs with complex dependencies. In contrast, our approach works with arbitrary DAG-based workloads. It checks all dependencies before allowing a job to be stolen (Algorithm 2, Line 6). This ensures that a worker only steals jobs for which all prerequisite jobs have been completed, thereby preventing deadlocks or wasted computation.

- Capability-driven job matching: The selection of a job to steal involves matching on the delegator (Algorithm 2, Line 6) that considers the specific computational and resource requirements of available jobs against the profiled capabilities (Equation (1)) of the prospective worker device.

- Dynamic chunk sizing: In contrast to fixed-size chunks in the original Honeybee [17], Honeybee-Tx adaptively determines the number of jobs in a chunk for a requesting worker (Algorithm 2, Line 3) based on the worker’s performance metrics, allowing more powerful devices to steal larger chunks and improving overall throughput.

- Centralized job pool with work stealing: The framework utilizes a centralized job pool on the delegator, structured as a double-ended queue, from which workers can steal jobs. This work stealing model allows workers to voluntarily and opportunistically pull work when idle, ensuring intrinsic load balancing.

4.3.1. Dependency Management and DAG Operations

While the work stealing mechanism (Section 4.3) ensures dependency-aware job selection, this section details the underlying DAG management mechanism that enables complex workflow orchestration in Honeybee-Tx.

4.3.2. DAG Management

Job dependencies are represented as a Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG), , where V is the set of jobs, and an edge signifies that job must complete before job can begin. For any job , its immediate prerequisites are

The Dependency Graph Manager provides three core operations:

The Dependency Graph Manager provides three core operations essential for workflow orchestration. First, it performs dependency verification by ensuring that before any job can be stolen, all prerequisite jobs have reached the COMPLETED state in the DAG. Second, it enables dynamic DAG updates upon job completion or failure by setting the job’s state and identifying newly ready jobs whose dependency sets have become empty. Third, it exposes an interface for querying the DAG’s current state, providing real-time visibility into execution progress and enabling bottleneck detection and operational oversight.

Algorithm A1 in Appendix A ensures the global dependency graph G remains consistent whenever any job terminates. On completion, the routine (i) marks the job’s state, (ii) unlocks successor jobs whose prerequisite list Dep() is now empty, and (iii) moves those ready jobs back into the JobPool for immediate stealing. If a job fails, the same procedure rolls the job back for re-stealing while keeping a failure counter so that errors can be escalated. This guarantees the at-most-once execution of every edge in the DAG and prevents deadlock cycles by never exposing a job until all inbound edges are satisfied.

4.4. Core Mechanism 3: Resilience via Staged Result Management

To counter device volatility and ensure correctness in MCdC, Honeybee-Tx incorporates a multi-faceted adaptive resilience.

4.4.1. Staged Result Transfer and Job Recovery

Unlike typical MCdC frameworks that transfer results only upon job completion, Honeybee-Tx’s staged transfer mechanism incrementally sends partial results back to the delegator at defined checkpoints. Let be the progress threshold (e.g., a percentage of the total work). When job progress increases by at least , a checkpoint is sent:

Mobile connections are dynamic and intermittent; sending only a final result risks losing all progress. Algorithm 3, therefore, checkpoints a running job whenever the fractional progress increases . Each checkpoint is assigned a monotonic ID (chkID) so that the delegator can discard duplicates and resume from the last acknowledged offset. Because the worker sleeps between polls, network and energy overheads stay bounded, while long-running jobs (e.g., inference jobs) regain minutes of work after a transient drop-out. When a worker fails, the delegator resumes from the last checkpoint rather than restarting from zero.

| Algorithm 3 Staged result transfer from worker to delegator. |

|

When a worker disappears, the delegator consults the most recent tuple , where c is the latest checkpoint blob (saved state of the job) and the associated progress ratio. If one or more alternative workers satisfy the job’s resource vector, the delegator encapsulates a recovery job and allows the best-ranked candidate to steal it (Line 8). Otherwise, it either executes the job locally or queues it until resources return. Hence, recovery time is proportional to the checkpoint interval rather than the full job duration, greatly improving the makespan under churn.

Key Resilience Features

The framework’s resilience mechanism incorporates several key features that work synergistically to ensure reliable execution. Progress-aware resumption allows jobs to restart from their last checkpoint, significantly reducing wasted computational effort. This capability is complemented by capability-conscious re-delegation, where recovery prioritizes workers with the best current capability match for stealing jobs. When no suitable worker is available, the system provides graceful fallback by either resuming execution locally on the delegator or queuing the job until resources become available. Furthermore, the checkpoint threshold can be dynamically tuned based on job criticality, network conditions, or worker performance, providing adaptive resilience that responds to changing environmental conditions.

4.4.2. Heartbeat-Based Liveness Monitoring

To detect silent failures promptly, Honeybee-Tx employs lightweight heartbeat signals that flow from each worker to the delegator. Every s, a worker piggy-backs a 12-byte liveness frame on either a data packet (preferred) or a thin UDP keep-alive:

If the delegator misses consecutive heartbeats from , it marks as OFFLINE and triggers the recovery routine in Algorithm A2. Conversely, a worker drops its connection and re-initiates the handshake if it receives no HB_ACK for the same interval, ensuring symmetric failure detection in partitioned networks.

4.4.3. Resilience Optimization: Adaptive Checkpointing

Staged transfer (Algorithm 3) trades transfer overhead for recovery granularity. Algorithm 4 computes an adaptive progress threshold . The algorithm normalizes three factors to compute an adaptive checkpoint interval.

| Algorithm 4 Adaptive progress threshold for checkpointing. |

|

The first factor, worker performance , represents the historical job completion rate of each worker device, with slower workers requiring more frequent checkpoints to minimize potential work loss. The second factor, job criticality , provides a DAG-based metric where jobs with many dependent successors receive higher scores, reflecting their importance to overall workflow completion. The third factor, job size , captures the normalized execution time estimate, with larger jobs checkpointing less frequently to reduce the overhead associated with state preservation and transfer.

The normalization ensures consistent scaling across heterogeneous devices and workloads. Each factor is computed as

4.5. Worker Operational Model

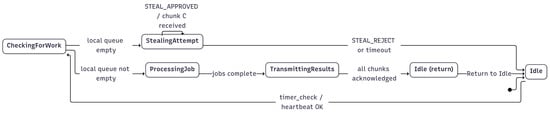

A state machine, shown conceptually in Figure 3, governs each worker’s behavior. The worker’s lifecycle is managed through this state machine with transitions triggered by events such as job completion, timeouts, or receipt of control packets. Figure 3 does not represent only the first job chunk. Because the transitions form a closed loop, the same process applies to every subsequent chunk until the job pool is exhausted at the delegator.

Figure 3.

Honeybee-Tx worker lifecycle. Subsequent chunks are delivered by the delegator, as presented in (Algorithm A5), and the chunk size is determined by worker capability. A worker repeatedly cycles through idle, checking for work, stealing (if the local queue is empty), processing jobs, and transmitting results. The loop covers both the initial chunk received and any subsequent job chunks until all jobs are acknowledged.

The conceptual states and transitions can be described as follows. The worker operates through five distinct states that collectively manage its participation in the collaborative computing process. The Idle state represents periods when the worker has no local work to process. From this state, the worker transitions to CheckingForWork, where it examines its local queue for available jobs. When the local queue is empty, the worker enters the StealingAttempt state, acting as a steal request listener to acquire new work from the delegator. Upon successfully obtaining jobs, the worker moves to the ProcessingJob state, where actual computation occurs. Finally, the TransmittingResults state handles the transfer of completed work back to the delegator before returning to the idle state to begin the cycle anew.

Transitions between these states are event-driven by triggers such as job completion, timeouts, or the receipt of a packet. These transitions respect the delegator’s global feature flags, namely and . Advertised during the capability handshake, these flags allow a delegator to toggle advanced functionality at runtime without modifying worker binaries. Algorithm A4 details the worker’s lifecycle. Each worker first drains its local queue; only when idle does it consult its -periodic delegator steal request and invoke the dependency-aware stealing protocol.

4.5.1. Concurrency Remark

In Algorithm A5, Lines 6–10 run in dedicated “execution” threads, enabling the main loop to remain responsive to incoming steal approvals or cancellations.

Delegator-Side Steal-Request Handler

When a delegator receives a STEAL_REQ from a worker device, it executes the handler detailed in Algorithm A5 to intelligently arbitrate the request. This process ensures that off-loading work is beneficial to the overall system performance and respects all job and device constraints. The handler’s logic proceeds as follows:

- Initial sanity check: First, the delegator assesses its own state to decide if it should even consider off-loading work. It measures its current computational load factor () and checks for any critically stalled jobs. The request is immediately rejected if either the delegator’s own load is below a configurable threshold (), meaning it is under-utilized, or if it has a high-priority job stalled in its local queue that requires immediate attention. This prevents the delegator from giving away work when it could be completing tasks itself or when a critical dependency is blocked locally.

- Filtering for stealable jobs: If the initial check passes, the delegator filters its central JobPool to create a set of currently stealable jobs (E). A job is considered stealable only if it is dependency-safe (i.e., all its prerequisite jobs in the DAG have been completed) and is not already being processed by another worker. If this set is empty, the delegator does not respond with any job chunk.

- Capability-aware matching: If stealable jobs exist, the handler retrieves the capability profile (p) of the requesting worker, which contains its CPU, memory, and energy characteristics. Using the SelectForStealing routine (defined in Algorithm 1), it then finds the most suitable job () from the stealable set that best matches the worker’s specific capabilities.

- Job transfer and state update: If a suitable job is found, the delegator attempts to transfer it to the worker. If the network transfer is successful, the delegator atomically updates the job’s state in the DAG to indicate execution by the requesting worker and returns an APPROVED status, ensuring the job is not offered elsewhere. Conversely, if the transfer fails (e.g., due to network issues) or if no suitable job was found during the matching phase, the handler returns a FAILED status, and the job remains in the delegator’s pool to be stolen later.

4.6. Application-Specific Parallelization: Video Processing Case

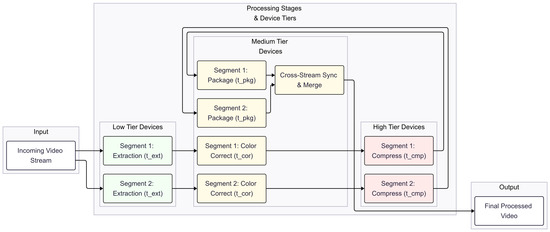

To illustrate how domain knowledge complements Honeybee-Tx, we consider a multi-camera video analytics pipeline (evaluated further in Section 6). This example demonstrates how even a simple tier-aware first-fit heuristic can accelerate the early stages of execution before the normal work stealing loop takes over. Figure 4 depicts the processing stages mapped across low, medium, and high device tiers, while Algorithm A6 shows the corresponding initial placement routine.

Figure 4.

Heuristic first-fit partitioning for a video pipeline.

4.6.1. Pipeline Initialization

The input stream is divided into equal-duration segments , each treated as an independent unit of work. Four jobs are created per segment: extraction (t_ext), colour-correction (t_cor), compression (t_cmp), and packaging (t_pkg). Devices are grouped into three capability tiers using their CapScore. Workers with hardware encoders/accelerators are placed in High, recent mid-range smartphones in Med, and legacy/low-power devices in Low.

4.6.2. Heuristic Assignment

The first-fit mapping (Lines 7–10 of Algorithm A6) greedily assigns each stage to the lightest tier capable of meeting its demand vector. For example, extraction (t_ext) is pushed to low-tier devices, colour-correction (t_cor) and packaging (t_pkg) go to mid-tier devices, and compression (t_cmp), the most compute- and energy-intensive stage, is reserved for high-tier devices. This preserves scarce high-tier capacity for the bottleneck stage.

Although the mapping is simple, it ensures that, from the very first segment, the pipeline is well balanced across available resources, reducing cold-start latency and minimizing initial queue imbalances. After this seeding phase, Honeybee-Tx’s dependency- and capability-aware stealing can still re-shuffle jobs dynamically, ensuring resilience to churn and better long-term utilization. Thus, the example demonstrates how domain knowledge (tier-aware heuristics) and the general framework (dynamic stealing) work together.

5. Application Programming Model

Having established the framework’s core mechanisms in Section 4, we now describe how developers leverage these capabilities through Honeybee-Tx’s programming model and API. This section further details how computational workloads are decomposed, specified, and orchestrated across heterogeneous mobile devices. Honeybee-Tx requires applications to specify their computational structure statically before execution, enabling efficient dependency verification and resource matching at runtime. This section describes how applications are prepared for distributed execution within our framework.

5.1. Job Execution Environment

Worker devices execute jobs within a sandboxed Android runtime that provides resource isolation, progress monitoring, and controlled termination. The execution environment allocates memory and CPU resources to each job based on its declared demand vector, enforcing these limits through Android’s process management APIs. During execution, the environment monitors job progress at regular intervals of s, as specified in Algorithm 3. This monitoring serves dual purposes: it enables the framework to detect stalled or failed jobs for recovery, and it triggers checkpoint operations when sufficient progress has been made. The sandbox ensures that jobs can serialize their intermediate state for checkpointing through standard Java serialization mechanisms while also providing controlled termination capabilities if workers disconnect unexpectedly or if jobs exceed their allocated time limits, as defined in Section 4.1.

5.2. Application Preparation and Resource Specification

Applications must decompose their workload into discrete computational jobs, each annotated with a demand vector that specifies normalized resource requirements on a scale from 0 to 1. These demand vectors are obtained through three complementary approaches that balance accuracy with development effort. The first approach involves profiling initial runs on reference devices to measure actual resource consumption, providing the most accurate estimates but requiring additional development time. The second approach allows developers to annotate jobs based on their algorithmic complexity, such as specifying higher CPU demands for O() operations compared to O(n) operations. The third approach employs stage-based estimation using predefined profiles for common operation types; for instance, video encoding stages typically require , while simple data extraction operations need only . These normalized values enable the capability matching mechanism described in Algorithm 1 to effectively match jobs to appropriate devices.

Each job specification also declares its input data requirements, including the size and format of expected inputs, the estimated output size for network planning, and any intermediate data products that will be generated for consumption by dependent jobs. This comprehensive specification enables the framework to perform accurate resource allocation and network bandwidth planning during the work stealing process.

5.3. Data Transfer and Dependency Management

The framework manages data movement between devices through three interconnected mechanisms that operate transparently to the application developer, ensuring efficient data flow while maintaining dependency correctness.

When a worker device successfully steals a job through the dependency-aware protocol detailed in Algorithm 2, the delegator must transfer the necessary input data to enable job execution. The framework automatically identifies the required input data from the job’s specification and packages it with the job metadata in the STEAL_APPROVED response packet. The data transfer occurs for chunks of jobs, as defined in the global configuration, with the chunk size determined dynamically based on worker capability and performance history, as described in Algorithm 2 (Line 3). This chunking strategy balances between minimizing communication overhead and ensuring that workers receive sufficient work to remain productive.

Dependencies between jobs are declared as a static Directed Acyclic Graph , where vertices represent individual jobs and edges encode both precedence constraints and data flow relationships. Each edge in the graph carries dual semantics: it indicates that job must complete successfully before job can begin execution, and it specifies that the output data produced by will be consumed as input by . The framework leverages these edge annotations to automatically route intermediate results between jobs, implementing a caching strategy at the delegator when multiple downstream jobs require the same intermediate data. This approach eliminates the need for manual data transfer specification while ensuring correct execution order across the distributed device pool, as verified through the dependency checking process in Line 6 of Algorithm 2.

The identification of intermediate results for transfer requires careful consideration of both correctness and efficiency. Jobs implement a getIntermediateResults() callback method that returns data to be transferred at checkpoint boundaries. The framework determines what data to transfer based on the job’s output specification and the DAG structure, ensuring that any data required by waiting downstream jobs is prioritized for transfer according to the staged result mechanism described in Algorithm 3.

5.4. Runtime Progress Evaluation and Checkpointing

Progress evaluation forms a critical component of the framework’s resilience mechanism, enabling both failure recovery and adaptive load balancing. Applications implement progress callbacks that return normalized values in the range , representing the fraction of work completed. The framework supports three common progress evaluation patterns that cover most application scenarios. Iteration-based progress calculation divides the current iteration count by the total expected iterations, suitable for applications with fixed computational loops. Data-based progress tracking computes the ratio of bytes processed to total input size, ideal for streaming or batch processing applications. Frame-based progress monitoring, specifically designed for video processing applications, tracks the number of frames completed relative to the total frame count in the video sequence.

The framework queries these progress callbacks at regular intervals of seconds, as specified in Algorithm 3, using the returned values to make checkpoint decisions. The progress threshold that triggers checkpoint operations adapts dynamically based on runtime conditions, as formalized in Algorithm 4. This adaptation considers three key factors that influence checkpoint frequency. Worker reliability , computed as the historical job completion rate, increases checkpoint frequency for devices with poor track records, ensuring that progress is preserved, even if unreliable devices disconnect. Job criticality , determined by counting the number of dependent jobs in the DAG, triggers more frequent checkpoints for jobs on the critical path to minimize the impact of failures on overall completion time. Network quality , measured through latency and packet loss metrics, adjusts checkpoint frequency to balance between progress preservation and network overhead, with poor connections paradoxically requiring more frequent but smaller checkpoints to ensure successful transmission.

When the accumulated progress since the last checkpoint exceeds the adaptive threshold , the framework initiates a checkpoint transfer using the staged result mechanism described in Section 4.4. This transfer includes both the intermediate computational state and any partial results generated since the last checkpoint, enabling efficient recovery from the most recent progress point rather than restarting from the beginning.

5.5. Execution Orchestration

At runtime, the framework coordinates execution through the work stealing protocol detailed in Section 4.2. The delegator maintains a central job pool populated with application-defined jobs, from which idle workers request work through STEAL_REQ messages. The framework filters candidates based on dependency satisfaction and capability matching, bundles selected jobs into appropriately-sized chunks based on worker performance history, and manages all data routing according to the DAG specification. Throughout execution, regular progress monitoring triggers adaptive checkpointing, while the delegator assembles final results from completed jobs according to the application’s output specification.

5.6. Design Constraint

All dependencies and data flows must be declarable before runtime. Dynamic dependency discovery during execution is not supported, ensuring predictable verification overhead and enabling the static optimizations described in Section 4.6.

Section 6 presents a comprehensive experimental evaluation of this implementation using two representative applications, Human Activity Recognition and multi-camera video processing, demonstrating how these implementation choices translate into measurable performance improvements: a total of 4.72× speed-up with 63% energy reduction for HAR tasks, and 2.06× speed-up with 51.4% energy savings for video processing workloads, validating the effectiveness of our heterogeneity-aware and dependency-driven approach to MCdC.

6. Application and Evaluation

To evaluate the efficacy of Honeybee-Tx, we developed two complementary applications: (i) Human Activity Recognition (HAR), which demonstrates the framework’s resilience and performance maximization mechanisms, and (ii) a multi-camera video-processing pipeline, which demonstrates dependency-aware stealing. These applications represent key MCdC use cases of fine-grained sensor analytics and compute-intensive media workflows.

6.1. Application Scenarios

6.1.1. Human Activity Recognition (HAR)

This scenario centers on a fitness enthusiast tracking workout patterns to optimize training routines. The user’s smartphone collects motion data to detect and classify activities like running, cycling, or weight training. To process this data efficiently without draining the battery, nearby smartphones at the gym form a ‘mobile computing crowd’, contributing computational resources for real-time analysis.

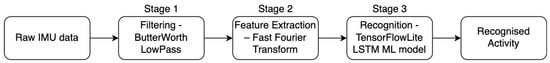

In our experiment, we use the UCI HAR dataset [58] as the sensor dataset. The participating smartphones in the ‘mobile computing crowd’ classify six daily activities from tri-axial accelerometer and gyroscope traces. The job graph contains four stages (Figure 5): beginning with feature extraction that derives temporal and frequency-domain characteristics from raw sensor data, followed by pre-processing operations that normalize and filter the extracted features. The pipeline then performs classification using multiple machine learning models, including Random Forest, SVM, and small CNNs to identify activity patterns; it concludes with result aggregation, which combines predictions from different classifiers to produce a final activity label.

Figure 5.

Four-stage HAR job graph executed atop Honeybee-Tx.

HAR is ideal for evaluating framework scalability because (i) workload can be precisely partitioned across devices; (ii) performance metrics are easily measurable; and (iii) parallel execution across multiple sensor windows tests the work stealing mechanism. This scenario specifically stress-tests our contributions in adaptive resilience through staged transfers (C1) and (C3).

Building on the HAR evaluation in Section 6.1.1, which demonstrated the framework’s scalability across five heterogeneous Android devices and its ability to reduce energy consumption through adaptive checkpointing, we now examine performance on compute-intensive video processing with complex inter-frame dependencies.

6.1.2. Multi-Camera Video Pipeline

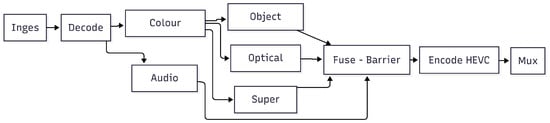

This scenario models a video analytics workflow with branching and joining, as shown in Figure 6. The DAG, instantiated per segment of length , has 10 stages: Ingest→Decode→ColourCorrect→, three parallel branches {ObjectDetect, OpticalFlow, SuperRes}, and an auxiliary AudioAlign branch; the results Fuse at a barrier, followed by EncodeHEVC and Mux. The barrier uses the same listener pattern as our inter-device synchronization (Algorithm A3).

Figure 6.

DAG of a video analytics application.

In our experiment, the video workload consumes synchronized streams from EPFL [59] and Stanford MVVA [60]. Its DAG comprises a five-stage processing pipeline that begins with frame decoding to extract individual frames from compressed video streams, followed by pre-processing operations that normalize and enhance frame quality. The pipeline then performs object detection and analysis using computer vision algorithms to identify relevant events or anomalies, after which the processed frames undergo H.265 re-compression to reduce storage and transmission requirements. Finally, the mixing stage combines the processed streams into a unified output format suitable for storage or further analysis.

The dependencies span within each stream (sequential) and across cameras (scene stitching), providing a stringent test bed for Honeybee-Tx’s dependency-aware stealer. This use case is designed to rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of our heterogeneity-aware and static DAG-aware stealing mechanisms (C1 and C2), as well as to measure the resulting performance gains on a complex workload (C3).

6.2. Experimental Setup

All experiments were run on the devices listed in Table 5. The experimental test bed comprises five Android devices with heterogeneous capabilities, connected via Wi-Fi Direct (5 GHz; 80 MHz). These worker devices were linked via Wi-Fi Direct (5 GHz; 80 MHz). The JobPool started with 10,000 jobs for HAR application and 100 videos for the multi-camera video pipeline application, heartbeat s, and adaptive checkpoint base .

Table 5.

Experimental device specifications.

6.3. Evaluation Methodology

6.3.1. Performance Metrics

Speed-up is calculated as

where is the execution time when the delegator processes all jobs alone, and is the execution time using Honeybee-Tx with worker devices. A speed-up greater than 1 indicates performance improvement through collaboration.

Average battery usage represents the mean battery percentage consumed by the delegator device across multiple experimental runs:

where m is the number of experimental runs (), and and are the delegator’s battery percentages at the start and end of experiment i. This metric captures the energy cost incurred by the delegator for orchestrating the collaborative computation.

Average memory usage represents the mean peak memory consumption of the delegator device across experimental runs:

where is the maximum memory usage (in MB) recorded on the delegator during experiment i. This metric captures the memory overhead of managing the distributed computation.

Average network traffic quantifies the mean data transfer volume handled by the delegator across experimental runs:

where and are the total bytes sent and received by the delegator during experiment i. This metric measures the communication overhead of coordination and data exchange.

Average energy consumption measures the mean electrical energy consumed by the delegator device:

where is the energy consumed (in mAh) by the delegator during experiment i, calculated from battery discharge and device voltage. This provides a hardware-independent measure of energy cost.

Each application targets different Honeybee-Tx facets:

6.3.2. HAR (Performance and Scalability Focus)

The HAR application evaluation emphasizes four key performance dimensions. First, heterogeneous device utilization measures how effectively the framework leverages different device capabilities across the worker pool, from high-end devices with ML acceleration to resource-constrained older phones. Second, the scalability analysis quantifies the speed-up achieved as the number of worker devices increases, demonstrating the framework’s ability to efficiently coordinate growing collaborative networks. Third, the evaluation of staged transfers reveals the impact on the performance vs. resilience trade-off, showing how incremental result transmission affects both system throughput and recovery capabilities. Finally, energy efficiency measurements compare per-device power consumption between collaborative and monolithic execution modes, validating the framework’s ability to reduce individual device energy expenditure through workload distribution.

6.3.3. Video Pipeline (Dependency Focus)

The video processing pipeline evaluation concentrates on three critical aspects of dependency management and resource allocation. The assessment of dependency-aware stealing validates correct job scheduling on the DAG, ensuring that temporal dependencies between video frames are properly maintained throughout distributed execution. Evaluation of capability matching demonstrates how the framework effectively aligns computationally intensive H.265 encoding and computer vision stages with high-end phones possessing appropriate hardware acceleration. The analysis of dynamic chunking explores the relationship between throughput and chunk size, revealing optimal configurations for balancing communication overhead with work distribution efficiency.

Metrics: Common to both workloads are overall completion time, mean job turnaround, energy usage, delegator memory, network traffic, and validation accuracy (HAR only).

6.4. Results and Analysis

6.4.1. HAR: Speed-Up and Energy

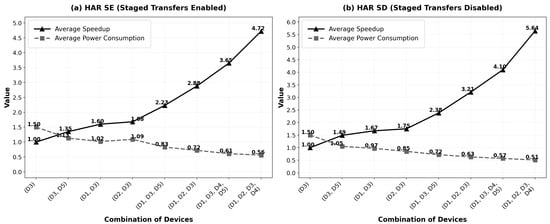

The performance of the HAR application was evaluated in two configurations: Honeybee-Tx’s staged transfer mechanism enabled (for resilience) and disabled (for baseline performance). Figure 7 presents the results, showing the trade-off between execution speed, energy consumption, and reliability.

Figure 7.

Avg. speed-up and power consumption vs. combination of devices running HAR app in Honeybee-Tx; (a) staged transfers enabled; (b) staged transfers disabled.

This evaluation of the HAR application demonstrates the framework’s scalability and the explicit performance trade-offs of its resilience features. As defined in Equation (5), speed-up measures the performance gain from collaborative execution. The average battery usage was measured by recording the percentage of battery consumed by each device during the complete execution of 10,000 HAR classification jobs.

As shown across both figures, the framework scales effectively: the speed-up increases near-linearly as more workers are added, while the average energy burden per device consistently decreases. This shows that Honeybee-Tx successfully distributes the computational load to both accelerate the task and conserve power on individual devices.

As shown in Figure 7, the framework demonstrates two key findings:

- Scalability: The speed-up increases near-linearly with additional workers, proving that Honeybee-Tx effectively parallelizes the HAR workload across heterogeneous devices. The near-linear scaling from 1× (monolithic) to 4.72× (4 workers with staged transfers) validates the efficiency of our capability-aware job stealing mechanism (Algorithm 1).

- Delegator energy efficiency: The average battery consumption of the delegator device consistently decreases as more workers join the collaboration, dropping from 1.5% (monolithic execution) to 0.56% (with 4 workers). This proves that distributing work to nearby devices significantly reduces the energy burden on the delegator, even though it continues to orchestrate the computation. The delegator’s reduced workload more than compensates for its coordination overhead.

6.4.2. Multi-Camera Video Pipeline

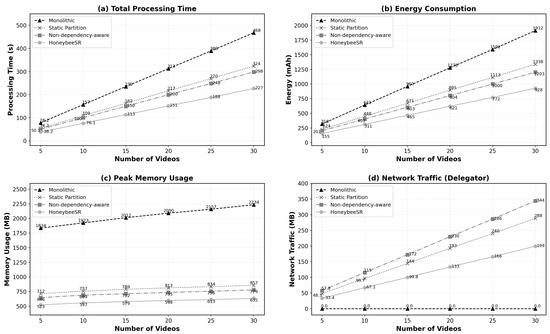

To provide a comprehensive performance benchmark, the Honeybee-Tx framework was evaluated against three distinct baseline approaches: a Monolithic execution (all tasks on one device), a Static Partition approach, and a Non-dependency-aware work stealing model. The evaluation was carried out by processing an increasing number of video streams, with results captured across four critical metrics: total processing time, energy consumption, maximum memory usage, and network traffic, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Video pipeline performance of Honeybee-Tx vs. baselines.

6.4.3. Processing Time and Energy Consumption

The results for processing time (Figure 8a) and energy consumption (Figure 8b) demonstrate a clear and consistent advantage for Honeybee-Tx. Both metrics show a linear increase for all approaches as the number of videos grows. However, Honeybee-Tx consistently achieves the lowest processing time and consumes the least energy. This highlights the efficiency of its dependency-aware scheduling and dynamic load balancing, which lead to a significant speed-up and energy savings. This efficiency is crucial for MCdC, where prolonging device battery life is a primary constraint.

6.4.4. Peak Memory and Network Traffic

The memory and network results (Figure 8c,d) illustrate key architectural trade-offs. The monolithic approach, while incurring zero network traffic, consumes a substantially higher amount of memory, making it unsuitable for resource-constrained mobile devices. In contrast, Honeybee-Tx maintains the lowest maximum memory usage among all frameworks.

While distributed approaches inherently introduce network traffic, Honeybee-Tx is shown to be the most conservative, generating significantly less traffic than both the static and non-dependency-aware models. This shows that Honeybee-Tx achieves an effective balance, achieving substantial performance gains at a minimal and well-managed communication cost.

Collectively, these results validate the core contributions of the Honeybee-Tx framework. In all key metrics, it consistently outperforms the baseline approaches. Delivers the fastest processing times, the lowest energy consumption, and the most efficient memory footprint. The modest network overhead it introduces is a worthwhile trade-off for the significant, multi-faceted performance improvements it provides, confirming its suitability for executing complex, dependency-aware tasks in dynamic and opportunistic mobile environments.

7. Discussion

The experimental evaluation demonstrates that Honeybee-Tx successfully addresses the research challenge posed in Section 1.1, reliably leveraging heterogeneous edge devices for inter-dependent task execution despite device churn and resource variability. This section interprets the results in the context of the framework’s contributions and discusses their broader implications for mobile crowd computing.

7.1. Validation of Core Mechanisms

The near-linear speed-up observed in the HAR application validates the effectiveness of capability-aware job stealing (Algorithm 1). The framework successfully matched computational demands to device capabilities, as evidenced by the consistent performance gains when adding workers with varying specifications from the Snapdragon 835 delegator to Tensor-equipped workers. This heterogeneity-aware approach contrasts with static partitioning schemes that cannot adapt to runtime device characteristics. The video pipeline results further demonstrate the importance of dependency-aware scheduling (Algorithm 2). By respecting the DAG structure during work distribution, Honeybee-Tx achieved superior performance compared to non-dependency-aware approaches, particularly in memory efficiency, where the framework’s selective job assignment prevented resource exhaustion on constrained devices.

7.2. Energy and Resource Efficiency

A particularly significant finding is the delegator’s battery consumption pattern. The reduction from 1.5% to 0.56% demonstrates that the energy saved through computational off-loading substantially outweighs the coordination overhead. This validates a key assumption of MCdC: orchestration costs can be amortized across distributed execution. The staged result transfer mechanism (Algorithm 3) contributes to this efficiency by minimizing redundant data transmission while maintaining progress guarantees. The 71.6% memory reduction in video processing highlights another critical advantage. By leveraging the collective memory pool across devices rather than concentrating all data on a single node, Honeybee-Tx enables execution of workloads that would be infeasible on individual devices. This memory distribution, combined with the 42% reduction in network traffic compared to naive approaches, demonstrates the framework’s communication efficiency.

7.3. Trade-Offs and Design Decisions

The 16% performance penalty when enabling staged transfers (5.64× vs. 4.72× speed-up) quantifies the cost of resilience in dynamic environments. This trade-off is acceptable for most MCdC scenarios, where device disconnections are common. The adaptive checkpointing mechanism (Algorithm 4) allows applications to tune this balance based on their specific requirements. The choice of Wi-Fi Direct for device communication proved effective for the experimental workloads, providing sufficient bandwidth (80 MHz) for both control messages and data transfer. However, the network traffic measurements suggest that bandwidth-constrained scenarios might benefit from more aggressive data compression or result caching strategies.

7.4. Practical Deployment Considerations

The experiments reveal several insights for real-world deployment:

- Device selection: The performance differences between device models (particularly between Snapdragon and Tensor architectures) suggest that capability profiling during the handshake phase is crucial. Applications should implement device-specific optimizations, particularly for ML-accelerated workloads.

- Workload characteristics: The framework excels with workloads exhibiting natural parallelism (HAR’s sliding windows) or clear pipeline structures (video processing stages). Applications with tighter coupling between tasks may experience reduced benefits.

- Scale considerations: While our experiments used up to five devices, the near-linear scaling suggests larger device clusters could yield proportionally greater benefits, limited primarily by coordination overhead and network topology constraints.

7.5. Limitations and Future Directions

Several experimental constraints merit consideration. First, the controlled Wi-Fi Direct environment may not reflect the variability of real-world wireless conditions. Second, the specific device models used, while representative of current Android ecosystems, may not capture the full spectrum of heterogeneity in deployed systems. The static dependency model, while sufficient for the evaluated applications, may limit applicability to workloads with dynamic task graphs. Future work could explore adaptive DAG restructuring based on runtime conditions. Additionally, investigating the framework’s behavior under extreme churn rates would provide insights for highly mobile scenarios.

The results validate MCdC as a viable paradigm for edge computing scenarios where infrastructure is unavailable or impractical. By demonstrating efficient execution across heterogeneous devices with minimal coordination overhead, Honeybee-Tx provides a foundation for new classes of collaborative mobile applications. The framework’s ability to leverage device diversity as a strength rather than a limitation represents a significant advance in opportunistic computing. The quantified trade-offs between performance, energy efficiency, and resilience provide system designers with concrete guidance for deploying MCdC solutions. As mobile devices continue to increase in computational capability while maintaining energy constraints, frameworks like Honeybee-Tx will become increasingly valuable for harnessing collective computational resources.

8. Conclusions

We present Honeybee-Tx, a dependency-aware work stealing framework for heterogeneous mobile crowd computing. Through capability-aware job stealing, DAG-based dependency management, and staged result transfers, the framework enables efficient collaborative execution across diverse mobile devices without infrastructure support.

Experimental evaluation on real Android devices demonstrated significant performance gains. With five devices (one delegator plus four workers), our HAR workloads achieved 4.72× speed-up, representing 94.4% of the theoretical maximum linear speed-up. This near-ideal scaling is particularly noteworthy, given the heterogeneous nature of our test bed (Snapdragon 835 delegator with Tensor-equipped workers) and the overhead of resilience mechanisms. As established by the authors of [57] in their foundational work on work stealing algorithms, achieving near-linear speed-up in distributed systems is challenging due to inherent scheduling overheads and synchronization costs. Our results demonstrate that Honeybee-Tx effectively mitigates these overheads through capability-aware job distribution.

The HAR application achieved a 63% reduction in delegator battery consumption, validating the energy efficiency of distributed execution in mobile contexts. The video processing pipeline achieved 2.06× speed-up with 71.6% memory savings and 42% less network traffic than non-dependency-aware approaches. While lower than HAR, this speed-up remains substantial for dependency-constrained workloads where inter-frame dependencies and cross-camera synchronization inherently limit parallelization potential, consistent with the constraints identified in prior work on DAG-based task scheduling in edge computing [61,62].