Abstract

Background/Objectives: Essential oils are liquid natural volatile mixture of compounds with several bioactive properties, which make them useful in a wide range of pharmaceutical applications. The aim of this work is to explore the antimicrobial impact of Cymbopogon martini essential oil against human clinical bacterial isolates from the skin and respiratory tract while also assessing its impact on mammalian cells. Geraniol, its main component according to GC-MS analysis, was evaluated under the same conditions. Methods: The composition of the essential oil was provided by the supplier. To elucidate the antimicrobial activity, the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and the minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) were determined. The impact on mammalian hepatic cells was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Results: The essential oil showed activity against Gram-positive bacteria from the Streptococcus and Staphylococcus genera, with MIC values ranging from 125 to 250 µg mL−1 for Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus anginosus, Streptococcus disgalactiae, and Streptococcus pyogenes. It also displayed activity against some of the tested Gram-negative bacteria, namely, Escherichia coli (MIC 350 µg mL−1), Moraxella catarrhalis (MIC 250 µg mL−1), and Morganella morganii (MIC 350 µg mL−1). In most cases, the essential oil showed lower MIC values than geraniol. Additionally, palmarosa oil had a weaker impact than geraniol in HepG2 cells. Conclusions: Both the essential oil and the pure compound exhibited activity against clinical isolates obtained from skin and respiratory tract samples.

1. Introduction

Essential oils are natural products obtained by steam distillation, mechanical pressing of citrus rinds, or dry distillation from aromatic plants, characterized by the occurrence of diverse volatile compounds, mainly aliphatic and cyclic hydrocarbons belonging to the monoterpenoid class [1]. Recent studies have highlighted the bioactive properties of these products, namely, their anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal properties [2,3,4]. Only a fraction of known plant species are classified as aromatic, and they are mainly concentrated within certain botanical families such as the Lamiaceae, Rutaceae, Myrtaceae, or Poaceae [5].

Species from the Cymbopogon genus (Poaceae) have a long history in traditional medicine across Asia, South America, and Africa, where the leaves and other parts of the plant are used for herbal teas or decoctions. Traditionally, plants from this genus have been employed to treat conditions such as fevers, respiratory tract infections, or digestive and inflammatory disorders [6]. Cymbopogon martini (C. martini), commonly known as palmarosa, is cultivated in India for its essential oil and is rich in monoterpenes and monoterpenic alcohols such as geraniol, which represents around 75–80% of its composition [7]. Palmarosa essential oil has been extensively used in ancient Indian and Southeast Asian traditional medicines and has been studied in recent years, showing noteworthy biological properties [8,9,10,11]. The essential oil has been demonstrated to attenuate skin inflammation and exhibit both antioxidant and antigenotoxic activities [8,11]. Moreover, it has also exhibited antimicrobial activity against several pathogens, including the fungi Malassezia furfur and Candida albicans, bacteria such as Staphylococcus epidermidis, and mites like Rhipicephalus linnaei [9,12]. Geraniol has also demonstrated notable bioactive properties, exhibiting antimicrobial activity against several bacterial species, including Escherichia coli, Helicobacter pylori, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. In addition to its antibacterial effects, geraniol shows broad antifungal activity, further supporting its potential as a multifunctional antimicrobial compound [13,14]. Beyond its antimicrobial potential, this compound has been reported to modulate key inflammatory and antioxidant signaling pathways, and it further displays significant antinociceptive activity [15,16]. Moreover, several industries, particularly the fragrance sector, use geraniol as a high-value scent compound, underscoring the relevance of its abundance in C. martini essential oil [7].

Antimicrobial resistance represents a rapidly expanding global challenge due to the ability of bacteria, fungi, viruses, or parasites to withstand antimicrobial treatment. In particular, antibiotic resistance specifically involves decreased bacterial susceptibility or complete resistance to antibiotic treatments. Several mechanisms are involved in this phenomenon, including enzymatic inactivation of the drug, reduced permeability, modification of the antimicrobial target, and enhanced efflux pump activity, which leads to high levels of drug expulsion [17,18]. It is estimated that bacterial infections account for approximately 7.7 million deaths annually, with about 4.95 million linked to drug-resistant pathogens and 1.27 million directly attributable to bacteria that no longer respond to currently available antibiotics [19]. Furthermore, several authors have anticipated that these mortality levels will continue to increase in the coming decades, reflecting the global burden of antimicrobial resistance [20]. The World Health Organization recognizes this issue as one of the top ten threats to global health. An updated version of the Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, highlighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria that pose a serious threat to global health, was released in 2024. Within this classification, Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are listed among the high-priority pathogens, reflecting their significant clinical burden, highlighting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Streptococcus spp., including macrolide-resistant Group A Streptococci, macrolide-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, and penicillin-resistant Group B Streptococci, are categorized as medium-priority pathogens [21]. This underscores the urgent need for strengthened infection prevention strategies, continuous surveillance, and innovative antimicrobial development. In this context, natural products traditionally used for the treatment of infectious diseases have gained renewed scientific interest as potential sources of novel antimicrobial compounds.

Given the traditional use of Cymbopogon species in the management of colds, sore throats, and tracheitis [22], the objective of this work is to study the antimicrobial properties of C. martini essential oil on bacterial isolates form the respiratory tract. The impact on skin isolates was also assessed, given that the oil is also suitable for topical application and has anti-inflammatory properties. The effects of the product were contrasted with those of geraniol, its major constituent, also evaluating the impact of both samples on hepatic mammalian cells.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Essential Oil

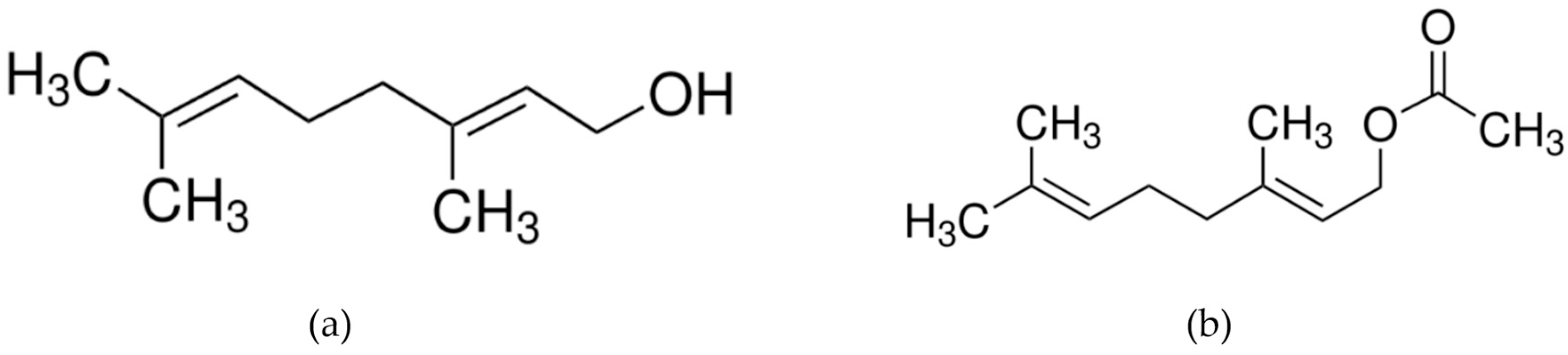

C. martini essential oil was provided by Pranarôm (Ghislenghien, Belgium), which also provided a description of its main characteristics. The essential oil was obtained by steam distillation; the batch was OF012293, obtained from the aerial parts of a C. martini var. motia (Roxb.) W. Watson cultivar from India. The essential oil was stored at room temperature and protected from light exposure. Stock solutions were prepared immediately before use. Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was also performed by the supplier under standardized conditions (Table 1). Chromatographic analyses were carried out using a TSQ92105012 instrument equipped with a 5SilMS 60-0.25-0.25 column. The temperature program consisted of an initial hold of 2 min at 40 °C, followed by a linear increase of 5 °C/min up to 320 °C, with a final hold for 10 min. Helium was employed as the carrier gas at a constant pressure of 3.2 bar. The method allowed for a detection limit of 0.01%, ensuring sensitive and reproducible quantification. The chemical structures of the main compounds identified in the essential oil can be seen in Figure 1. The chromatogram is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Phytochemical profile of C. martini essential oil provided by the supplier.

Figure 1.

Molecular structure of (a) geraniol (Mw: 154.25 g/mol) and (b) geranyl acetate (Mw: 196.29 g/mol).

2.2. Microorganisms Tested

Human clinical bacterial isolates were obtained from skin, soft tissues, and both upper and lower respiratory tracts. All the strains were isolated and identified at the Microbiology Laboratory of the Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa. Identification was carried out with a MALDI Biotyper Sirius system (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). Antibiograms that detail the antimicrobial resistance of clinical isolates are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

2.3. Antibacterial Activity

2.3.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC)

The broth microdilution method with 96-well plates was used to determine the MIC for both the essential oil and geraniol purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). A bacterial preculture was then incubated to 0.5 McFarland. From this suspension, 10 µL was added to a 96 well plate containing 190 µL of Tryptic Soy Broth (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) or Mueller–Hinton Broth supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood media (Beckman Coulter Inc., Brea, CA, USA), according to the bacterial requirements. Samples were previously dissolved in the media with dimethyl sulfoxide (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as a cosolvent. Negative controls and solvent controls were also prepared. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C, and the MIC was defined as the lowest antimicrobial concentration at which no visible bacterial growth was observed, indicated by the absence of turbidity. Control plates were prepared to verify the bacterial concentration. Three independent replicates were included.

2.3.2. Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

To assess the MBC, aliquots from the wells were diluted in Tryptic Soy Broth or Mueller–Hinton Broth supplemented with 3% lysed horse blood and plated on Mueller–Hinton agar or chocolate agar (BioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France). The plates were incubated overnight, and colonies were counted to calculate the MBC, defined as the lowest concentration that resulted in a 99.9% reduction in bacterial growth. All experiments were carried out in triplicate. An MBC/MIC ratio ≤ 4 was used to define bactericidal activity, whereas an MBC/MIC ratio > 4 was considered indicative of bacteriostatic activity [23].

2.4. Cytotoxicity

HepG2 cells, originating from human hepatocellular carcinoma, were employed to assess the potential cytotoxic effects of C. martini essential oil. The cell line, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA), was maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium obtained from Gibco (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cytotoxicity was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, 2 × 104 cells were seeded per well in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h. The medium was then replaced with Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium containing the essential oil or geraniol at different concentrations. Control wells received only culture medium without extract. Cells were exposed to the treatment for 24 h.

Following incubation, 100 µL of MTT solution (0.4 mg/mL) was added to each well, and the plates were incubated for 2 h in the dark. After the formation of formazan crystals, the MTT solution was carefully removed, and the crystals were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorbance was measured at 550 nm using a Synergy H1 hybrid multimode reader (Biotek Instruments, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany). All experiments were carried at least in triplicate. Concentration of cytotoxicity 50% (CC50) was also determined.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism 10 was used to perform the statistical analysis. Grubbs’ test was utilized to identify significant outliers. To compare the different concentrations tested with the untreated conditions or controls, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post hoc test was performed. CC50 values were also calculated with GraphPad Prism 10 through a non-linear regression. The obtained MIC and MBC values for the bacterial isolated were analyzed descriptively.

3. Results

3.1. Antimicrobial Activity

Table 2 shows the antimicrobial potential of both the essential oil and geraniol against different bacteria isolates. For the Gram-positive bacteria, C. martini displayed MIC values ranging from 125 to 300 µg mL−1 and MBC values from 250 to 500 µg mL−1. Those isolates with a lower MIC were Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus anginosus, both isolates having MICs of 125 µg mL−1 and an MBC of 250 µg mL−1, while the pure compound showed higher values. For both Streptococcus pyogenes isolates, the essential oil showed MIC and MBC values of 250 µg mL−1, while the values for geraniol could not be calculated. The MIC and MBC values of C. martini essential oil against both Staphylococcus species tested were 300 and 400 µg mL−1 respectively.

Table 2.

Antibacterial effect of palmarosa (C. martini) essential oil and geraniol expressed as MIC and MBC (µg mL−1) values on clinical isolates. All experiments were conducted in triplicate, with each assay comprising at least three technical replicates. Reported values correspond to the mean of the obtained results. Standard deviation (SD) is not shown in the table for MIC and MBC values. because these endpoints were determined in discrete concentration steps, and identical values were obtained across replicates.

For the Gram-negative bacteria, higher MIC and MBC values were found for the oil and geraniol, from 250 and 300 µg mL−1, respectively, to values higher than 1000 µg mL−1 and therefore were not determined. The lowest MIC values were determined for Moraxella catarrhalis (C. martini, 250 µg mL−1; geraniol, 300 µg mL−1). None of the tested products were active against Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates (MIC > 1000 µg mL−1). Klebsiella oxytoca and Achromobacter xylosoxidans were the only isolates where the MIC and MBC values were lower for geraniol (300 µg mL−1) than the essential oil (450 µg mL−1). For both Escherichia coli isolates, MIC values were lower for the essential oil (400 µg mL−1 surgical wound; 350 µg mL−1 tracheal aspirate) than geraniol (500 µg mL−1). As the MBC/MIC ratio was <4 for all strains showing activity, both the essential oil and geraniol were considered bactericidal for those isolates.

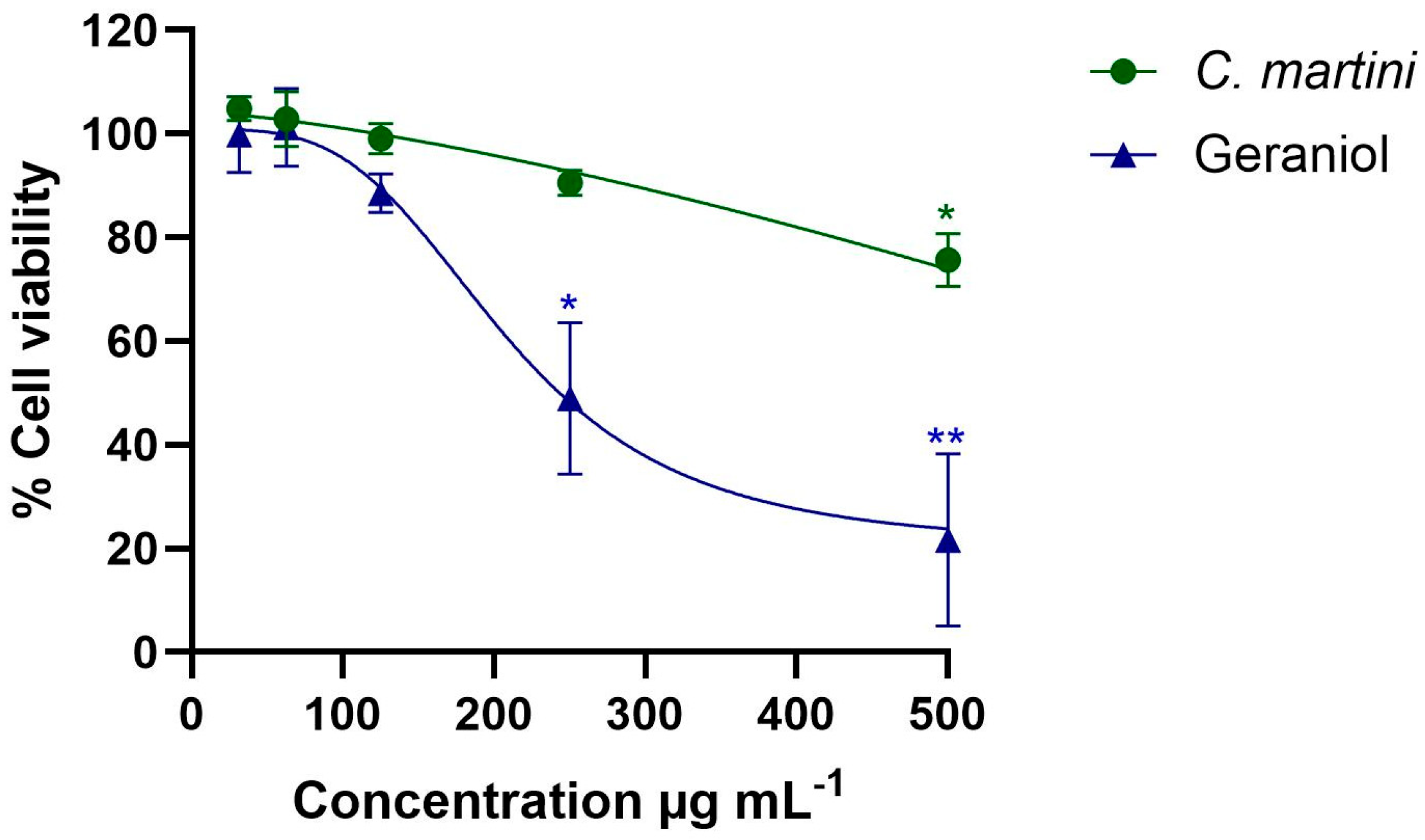

3.2. Impact on Mammalian Cells

The impact of both the essential oil and geraniol in the range of concentrations from 62.5 to 500 µg mL−1 on mammalian cells is presented in Figure 2. C. martini essential oil significantly reduced the viability of HepG2 cells at the highest concentration tested, 500 µg mL−1 (75.64% viability; p < 0.05). Geraniol also significantly reduced the viability at 250 µg mL−1 and 500 µg mL−1. The essential oil showed a higher CC50 value (761 ± 69 µg mL−1), than the pure compound tested under the same conditions (205 ± 8 µg mL−1)

Figure 2.

Impact of C. martini essential and geraniol on HepG2 cells after 24 h of exposure to different concentrations (from 31.25 µg mL−1 to 500 µg mL−1) using the MTT assay. All data were normalized relative to the untreated control group. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA (statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01). A higher concentration range (62.5 to 1000 µg mL−1) than the represented one was used to determine the CC50 values. The CC50 values were obtained by regression analysis following a non-linear curve fitting. C. martini essential oil CC50 = 761 ± 69 µg mL−1. Geraniol CC50 = 205 ± 8 µg mL−1.

4. Discussion

C. martini essential oil holds considerable commercial relevance across multiple industries, including the perfumery, cosmetics, agri-food and pharmaceutical industries, due to its persistent, rose-like fragrance that enhances product quality and consumer acceptance [7]. Additionally, it is also considered a valuable product due to its high geraniol content. In palmarosa oil, geraniol is the main component, representing 82.83% of the volatile fraction. Other compounds found were geranyl acetate (7.21%), linalool (7.71), and beta-caryophyllene (1.89%) (Table 1). This composition aligns with those in previous reports [7,24,25].

Geraniol is a monoterpenic alcohol employed in commercial formulations, particularly within the cosmetic and household product industries. This compound is a naturally occurring constituent of numerous essential oils such as Thymus daenensis, Aframomum citratum, Elettariopsis elan or those of the genus Cymbopogon [14]. In addition, recent reports have highlighted its antimicrobial properties, aligning with the results of this work (Table 2) [26]. Table 2 shows the antimicrobial potential of both the oil and geraniol against different bacteria isolates. Surprisingly, the oil showed potential against the genus Streptococcus, with an MIC value of 125 µg mL−1 for both Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus anginosus and 250 µg mL−1 for Streptococcus dysgalactiae and the two isolates of Streptococcus pyogenes. This genus includes over a hundred microbial species that colonize mucosal surfaces in humans and animals. Streptococcus pyogenes alone causes around 700 million infections each year, while Streptococcus agalactiae is associated with miscarriages, preterm births, and severe neonatal infections such as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis [27]. Streptococcus anginosus, usually a commensal of the oral, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary tracts, is often involved in abscesses and other purulent infections, and more recent research has implicated this species in gastric carcinogenesis through chronic gastric inflammation and progression to cancer [28]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the effects of C. martini essential oil on these bacteria. For geraniol, the results align with a previous report that studied the potential of this pure compound against Streptococcus pyogenes [29]. Both the oil and geraniol were also active against Staphylococcus aureus, aligning with previous reports [29,30].

Escherichia coli is a Gram-negative bacterium that constitutes part of the normal intestinal microbiota. However, under certain conditions, it can behave as an opportunistic pathogen, capable of causing severe infections beyond the gastrointestinal tract. In the present study, the isolates were obtained from tracheal aspirates and surgical wound samples. In cutaneous wounds, Escherichia coli may lead to skin and soft tissue infections that can progress and become life-threatening, particularly in patients who are immunocompromised [31,32]. The detection of Escherichia coli in tracheal aspirates is also significant, as this organism can act as an etiological agent of lower respiratory tract infections, including ventilator-associated pneumonia. In addition, such isolates often exhibit multidrug resistance and complex virulence profiles, posing major therapeutic challenges [33,34]. In this work, the oil and geraniol showed effects on Escherichia coli, with MIC values of 400 µg mL−1 and 350 µg mL−1 for the surgical wound and tracheal aspirate samples, respectively.

C. martini was also active against other Gram-negative bacteria relevant in clinical settings, namely, Morganella morganii (MIC 350 µg mL−1; MBC 500 µg mL−1), Moraxella catarrhalis (MIC 250 µg mL−1; MBC 250 µg mL−1), Serratia marcescens (MIC 350 µg mL−1; MBC 400 µg mL−1), and Klebsiella oxytoca (MIC 450 µg mL−1; MBC 450 µg mL−1). However, neither of the samples showed activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, with MIC values higher than 1000 µg mL−1 and therefore were not determined.

Geraniol and palmarosa essential oil seem to exert their antibacterial activity primarily by disrupting bacterial cell membrane integrity. Geraniol has been described as inducing membrane disintegration, causing ion leakage and altered fatty acid composition, which compromise membrane fluidity and leads to cell death [35,36]. Palmarosa oil may additionally generate reactive oxygen species and inhibit bacterial efflux pumps, further enhancing antimicrobial activity [12]. Overall, their activity may reflect a multifaceted mode of action primarily centered on membrane disruption. Additionally, it is worth noting that in most cases the essential oil displayed lower MIC values than those of geraniol (Table 2). This could be a result of the synergistic effect of the different compounds found in the oil (Table 1) since geranyl acetate, linalool, and beta-caryophyllene have demonstrated antimicrobial effects in other works [37,38,39]. Both the essential oil and geraniol reduced the viability of the HepG2 cells at the highest concentrations (Figure 2); however, the essential oil displayed a broader safety range for mammalian cells while, as mentioned, also displaying lower MIC values.

5. Conclusions

Plants from the Cymbopogon genus have a long history in traditional medicine. In this work, the essential oil obtained from the aerial parts of C. martini as well as its main constituent, geraniol, showed potential activity on clinical isolates from the skin and respiratory tract, being particularly strong against Streptococcus spp. and Staphylococcus spp. For most of the clinical bacteria tested, the essential oil showed lower MIC values and therefore higher antibacterial potency. This seems to indicate that the potential of other compounds found in the essential oil such as geranyl acetate, linalool or beta-caryophyllene cannot be overlooked. Additionally, the essential oil was less cytotoxic to HepG2 cells when compared with the pure compound. These results highlight the potential of C. martini for pharmaceutical uses and applications, particularly as an antimicrobial.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/pharmaceutics18010039/s1, Table S1: Antibiogram of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B) isolated from a diabetic foot ulcer; Table S2: Antibiogram of Streptococcus anginosus isolated from a surgical wound; Table S3: Antibiogram of Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from a pharyngeal sample; Table S4: Antibiogram of Streptococcus pyogenes isolated from a pharyngeal sample; Table S5: Antibiogram of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from a non-surgical wound; Table S6: Antibiogram of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from an ulcer; Table S7: Antibiogram of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a non-surgical wound; Table S8: Antibiogram of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from a sputum; Table S9: Antibiogram of Morganella morganii isolated from a non-surgical wound; Table S10: Antibiogram of Escherichia coli isolated from a surgical wound; Table S11: Antibiogram of Escherichia coli isolated from a tracheal aspirate; Table S12: Antibiogram of Moraxella catarrhalis isolated from an otic swab; Table S13: Antibiogram of Moraxella catarrhalis isolated from an otic swab; Table S14: Antibiogram of Serratia marcescens isolated from a sputum; Table S15: Antibiogram of Klebsiella oxytoca isolated from a sputum; Figure S1: Chromatogram of C. martini EO analyzed by GC-MS.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L. and C.S.; methodology, C.S.; software, P.C.; validation, V.L., E.A. and C.S.; formal analysis, P.C.; investigation, P.C.; resources, V.L. and C.S.; data curation, P.C.; writing—original draft preparation, P.C.; writing—review and editing, V.L., E.A. and C.S.; visualization, C.S.; supervision, V.L.; project administration, V.L.; funding acquisition, V.L. and C.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was financially supported by Cátedra Pranarom-Universidad San Jorge. The funders had no role in the study design, results, analysis, or conclusions. We also acknowledge 355 Government of Aragon for financial support of the Phyto-Pharm group (ref. B44_20R).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Gobierno de Aragón (Subvenciones para la contratación de personal investigador predoctoral en formación—Convocatoria 2023–2027) for providing a P.C. PhD grant.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| C. martini | Cymbopogon martini |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

References

- Kaspute, G.; Ivaskiene, T.; Ramanavicius, A.; Ramanavicius, S.; Prentice, U. Terpenes and Essential Oils in Pharmaceutics: Applications as Therapeutic Agents and Penetration Enhancers with Advanced Delivery Systems for Improved Stability and Bioavailability. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan, A.; Yarmolinsky, L.; Nakonechny, F.; Semenova, O.; Khalfin, B.; Ben-Shabat, S. Etrog Citron (Citrus medica) as a Novel Source of Antimicrobial Agents: Overview of Its Bioactive Phytochemicals and Delivery Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosilha, D.; Trigo, G.; Coelho, M.; Lehmann, I.; Melosini, M.; Serro, A.P.; Reis, C.P.; Gaspar, M.M.; Santos, S. Valorization of Thyme Combined with Phytocannabinoids as Anti-Inflammatory Agents for Skin Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahal, G.; Donmez, H.G.; Woerdenbag, H.J.; Taner, A.; Beksac, M.S. The Potential of Thymus zygis L. (Thyme) Essential Oil Coating in Preventing Vulvovaginal Candidiasis on Intrauterine Device (IUD) Strings. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Asbahani, A.; Miladi, K.; Badri, W.; Sala, M.; Aït Addi, E.H.; Casabianca, H.; El Mousadik, A.; Hartmann, D.; Jilale, A.; Renaud, F.N.R.; et al. Essential Oils: From Extraction to Encapsulation. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 483, 220–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibenda, J.J.; Yi, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Q. Review of Phytomedicine, Phytochemistry, Ethnopharmacology, Toxicology, and Pharmacological Activities of Cymbopogon Genus. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 997918, Erratum in Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 1109233. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2022.1109233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Sharma, N.; Gupta, A.K.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Lal, R.K. The Aromatic Crop Rosagrass (Cymbopogon martinii (Roxb.) Wats. Var. Motia Burk.) Its High Yielding Genotypes, Perfumery, and Pharmacological Potential: A Review. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2024, 32, 100280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, S.; Biswas, D.; Mukherjee, A. Antigenotoxic and Antioxidant Activities of Palmarosa and Citronella Essential Oils. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2011, 137, 1521–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, R.B.; Lima, K.R.d.; Assis-Silva, Z.M.d.; Ramos, D.G.d.S.; Monteiro, C.M.d.O.; Braga, Í.A. Acaricidal Potential of Essential Oils on Rhipicephalus linnaei: Alternatives and Prospects. Vet. Parasitol. 2024, 331, 110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Z.; Bai, L.; Xu, X.; Feng, B.; Cao, R.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Xing, W.; Yang, X. The Diverse Enzymatic Targets of the Essential Oils of Ilex purpurea and Cymbopogon martini and the Major Components Potentially Mitigated the Resistance Development in Tick Haemaphysalis longicornis. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2025, 208, 106271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Bhatt, D.; Singh, M.K.; Maurya, A.K.; Israr, K.M.; Chauhan, A.; Padalia, R.C.; Verma, R.S.; Bawankule, D.U. P-Menthadienols-Rich Essential Oil from Cymbopogon martini Ameliorates Skin Inflammation. Inflammopharmacology 2022, 30, 895–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, K.U.; Imam, M.W.; Kushwaha, S.; Khaliq, A.; Meena, A.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Yadav, N.P.; Tandon, S.; Chanda, D.; Luqman, S. Palmarosa Essential Oil Inhibits the Growth of Dandruff-Associated Microbes by Increasing ROS Production and Modulating the Efflux Pump. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 200, 107323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidrim, J.J.C.; Martins, D.V.; da Rocha, M.G.; dos Santos Araújo, G.; de Aguiar Cordeiro, R.; de Melo Guedes, G.M.; de Aquino Pereira-Neto, W.; de Souza Collares Maia Castelo-Branco, D.; Rocha, M.F.G. Geraniol Inhibits Both Planktonic Cells and Biofilms of the Candida parapsilosis Species Complex: Highlight for the Improved Efficacy of Amphotericin B, Caspofungin and Fluconazole plus Geraniol. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maczka, W.; Winska, K.; Grabarczyk, M. One Hundred Faces of Geraniol. Molecules 2020, 25, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnazar, S.M.; Mohagheghi, M.; Rahimi, S.; Dabiri, S.; Shahrokhi, N.; Shafieipour, S. Geraniol Modulates Inflammatory and Antioxidant Pathways to Mitigate Intestinal Ischemia–Reperfusion Injury in Male Rats. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch. Pharmacol. 2025, 398, 8713–8727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Viljoen, A.M. Geraniol—A Review Update. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 150, 1205–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauba, A.; Rahman, K.M. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestinaci, F.; Pezzotti, P.; Pantosti, A. Antimicrobial Resistance: A Global Multifaceted Phenomenon. Pathog. Glob. Health 2015, 109, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke, I.N.; de Kraker, M.E.A.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Kumar, C.K.; Schmitt, H.; Gales, A.C.; Bertagnolio, S.; Sharland, M.; Laxminarayan, R. The Scope of the Antimicrobial Resistance Challenge. Lancet 2024, 403, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Fan, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Kennelly, E.J.; Long, C. Ethnobotanical Uses, Phytochemistry and Bioactivities of Cymbopogon Plants: A Review. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2024, 330, 118181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishak, A.; Mazonakis, N.; Spernovasilis, N.; Akinosoglou, K.; Tsioutis, C. Bactericidal versus Bacteriostatic Antibacterials: Clinical Significance, Differences and Synergistic Potential in Clinical Practice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 80, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajeswara Rao, B.R.; Rajput, D.K.; Patel, R.P.; Purnanand, S. Essential Oil Yield and Chemical Composition Changes during Leaf Ontogeny of Palmarosa (Cymbopogon martinii var. motia). Nat. Prod. Commun. 2010, 5, 1947–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smitha, G.R.; Rana, V.S. Variations in Essential Oil Yield, Geraniol and Geranyl Acetate Contents in Palmarosa (Cymbopogon martinii, Roxb. Wats. var. motia) Influenced by Inflorescence Development. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 66, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lira, M.H.P.d.; Andrade Júnior, F.P.d.; Moraes, G.F.Q.; Macena, G.d.S.; Pereira, F.d.O.; Lima, I.O. Antimicrobial Activity of Geraniol: An Integrative Review. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2020, 32, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyściak, W.; Pluskwa, K.K.; Jurczak, A.; Kościelniak, D. The Pathogenicity of the Streptococcus Genus. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 32, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, K.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, W.; Cai, Y. Streptococcus anginosus: The Potential Role in the Progression of Gastric Cancer. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 151, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangol, S.; Poudel, D.K.; Ojha, P.K.; Maharjan, S.; Poudel, A.; Satyal, R.; Rokaya, A.; Timsina, S.; Dosoky, N.S.; Satyal, P.; et al. Essential Oil Composition Analysis of Cymbopogon Species from Eastern Nepal by GC-MS and Chiral GC-MS, and Antimicrobial Activity of Some Major Compounds. Molecules 2023, 28, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, N.; Cassola, F.; Gambero, A.; Sartoratto, A.; Gómez Castellanos, L.M.; Ribeiro, G.; Ferreira Rodrigues, R.A.; Duarte, M.C.T. Control of Pathogenic Bacterial Biofilm Associated with Acne and the Anti-Inflammatory Potential of an Essential Oil Blend. Microb. Pathog. 2024, 194, 106834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janny, S.; Bert, F.; Dondero, F.; Nicolas Chanoine, M.H.; Belghiti, J.; Mantz, J.; Paugam-Burtz, C. Fatal Escherichia coli Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Liver Transplant Recipients: Report of Three Cases. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2013, 15, E49–E53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovšek, Ž.; Eleršič, K.; Gubina, M.; Žgur-Bertok, D.; Erjavec, M.S. Virulence Potential of Escherichia coli Isolates from Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.S.; Gan, H.M.; Yap, K.P.; Balan, G.; Yeo, C.C.; Thonga, K.L. Genome Sequence of Multidrug-Resistant Escherichia coli EC302/04, Isolated from a Human Tracheal Aspirate. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 6691–6692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filipic, B.; Kojic, M.; Vasiljevic, Z.; Sovtic, A.; Dimkic, I.; Wood, E.; Esposito, A. A Longitudinal Study of Escherichia coli Clinical Isolates from the Tracheal Aspirates of a Paediatric Patient—Strain Type Similar to Pandemic ST131. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, A.C.; Meireles, L.M.; Lemos, M.F.; Guimarães, M.C.C.; Endringer, D.C.; Fronza, M.; Scherer, R. Antibacterial Activity of Terpenes and Terpenoids Present in Essential Oils. Molecules 2019, 24, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prashara, A.; Hili, P.; Veness, R.G.; Evans, C.S. Antimicrobial Action of Palmarosa Oil (Cymbopogon martinii) on Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, F.; Chen, Q.; Liang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Chen, W.; Chen, H.; Yun, Y.; Zhong, Q.; Chen, W. Antimicrobial Activity and Proposed Action Mechanism of Linalool Against Pseudomonas fluorescens. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 562094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Yusoff, K.; Ajat, M.; Wee, C.Y.; Yap, P.S.X.; Lim, S.H.E.; Lai, K.S. Combinatorial Antimicrobial Efficacy and Mechanism of Linalool Against Clinically Relevant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 635016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celuppi, L.C.M.; Capelezzo, A.P.; Cima, L.B.; Zeferino, R.C.F.; Carniel, T.A.; Zanetti, M.; de Mello, J.M.M.; Fiori, M.A.; Riella, H.G. Microbiological, Thermal and Mechanical Performance of Cellulose Acetate Films with Geranyl Acetate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 228, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.