Abstract

Antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) therapy, an advanced therapeutic technology comprising antibodies, chemical linkers, and cytotoxic payloads, addresses the limitations of traditional chemotherapy. This study explores key elements of ADC therapy, focusing on antibody development, linker design, and cytotoxic payload delivery. The global rise in cancer incidence has driven increased investment in anticancer agents, resulting in significant growth in the ADC therapy market. Over the past two decades, notable progress has been made, with approvals for 14 ADC treatments targeting various cancers by 2022. Diverse ADC therapies for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors have emerged, with numerous candidates currently undergoing clinical trials. Recent years have seen a noteworthy increase in ADC therapy clinical trials, marked by the initiation of numerous new therapies in 2022. Research and development, coupled with patent applications, have intensified, notably from major companies like Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), AbbVie Pharmaceuticals Inc. (USA), Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Tarrytown, NY, USA), and Seagen Inc. (Bothell, WA, USA). While ADC therapy holds great promise in anticancer treatment, challenges persist, including premature payload release and immune-related side effects. Ongoing research and innovation are crucial for advancing ADC therapy. Future developments may include novel conjugation methods, stable linker designs, efficient payload delivery technologies, and integration with nanotechnology, driving the evolution of ADC therapy in anticancer treatment.

1. Background of ADC Therapeutic Technology

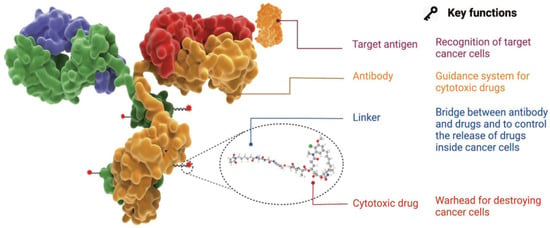

The antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) therapy technology is a next-generation therapeutic approach to overcome the limitations of conventional cancer chemotherapy. It is considered one of the next-generation anticancer treatment technologies that leverage the targeted selectivity of antibodies and the cell-killing efficacy of cytotoxic drugs to enhance therapeutic effects while minimizing side effects [1,2,3,4]. This technology involves the use of a drug composed of a low-molecular-weight cytotoxic agent (chemotherapeutic drug) chemically linked to an antibody that interacts with a specific antigen overexpressed on the surface of cancer cells through a chemical linker (Figure 1). This structure allows for the targeted delivery of the cytotoxic drug to cancer cells, enhancing the effectiveness of the anticancer treatment while minimizing adverse effects.

Figure 1.

Characteristics and structure of ADC [1]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature.

The optimal ADC therapy is characterized by its ability to maintain stability in the bloodstream, accurately reach targeted cancer cells, and ultimately release the cytotoxic payload in close proximity to the specified cancer cells for effective treatment. Essential components of ADCs in achieving these objectives encompass tumor-targeting antibodies designed to correspond to antigens expressed on cancer cells, along with linkers and cytotoxic payloads. The conjugation methods employed for these components represent a critical technological aspect in ADC manufacturing, enabling the precise assembly of these elements and ensuring optimal therapeutic outcomes.

1.1. Selection of Target Antigens

The target antigen expressed on cancer cells serves as the navigation system for ADC therapy, determining the mechanism for recognizing cancer cells and delivering the cytotoxic payload. The selection of an ideal target antigen is the first crucial consideration in this process. The criteria for the ideal selection of a target antigen typically involve its overexpression in cancer cells while being rare or very lowly expressed in normal tissues. Additionally, the antigen should be expressed on the surface of cancer cells. It is also essential that the chosen antigen is not secreted in the bloodstream to avoid unwanted binding of ADCs in undesired locations. Currently developed ADC therapies have selected target antigens such as HER2, trop2, nectin4, and EGFR for solid tumors and CD19, CD22, CD33, CD30, BCMA, and CD79b for hematologic malignancies [1,5,6]. These antigens have been chosen based on their overexpression in cancer cells and their suitability for effective ADC therapy.

1.2. Cancer Cell-Targeting Antibodies

Antibodies targeting cancer cells play a pivotal role in facilitating specific binding between the target antigen and ADCs. These antibodies should demonstrate high binding affinity to the target antigen, low immunogenicity, and an extended half-life. In the initial stages of ADC therapy development, antibodies derived from mice were commonly utilized. However, due to severe immunogenic side effects, especially associated with murine antibodies, the prevailing trend now predominantly favors the use of humanized antibodies produced through recombinant technology [7,8,9]. Humanized antibodies are generated by incorporating key regions of the mouse-derived antibody into a human antibody framework. This approach preserves the specificity and high binding affinity of the mouse antibody while minimizing the risk of immune reactions in humans. The transition towards humanized antibodies has significantly contributed to enhancing the safety and efficacy of ADC therapies.

1.3. Linkers

The linker in ADCs plays a crucial role in bridging the antibody and the cytotoxic drug, representing a critical determinant of ADC stability and the profile of payload drug release. This, in turn, significantly influences therapeutic efficacy. An ideal linker should avoid inducing ADC aggregation, prevent premature payload release in the bloodstream, and facilitate the release of active drugs precisely at the desired target. Linkers are broadly classified into two main types based on cellular metabolism processes [10,11,12,13]: cleavable linkers and non-cleavable linkers. Cleavable linkers are further subdivided into chemical cleavage linkers and enzyme cleavage linkers. These linkers offer the advantage of precisely releasing cytotoxic drugs, taking into account systemic circulation and environmental disparities between normal cells and cancer cells. On the contrary, non-cleavable linkers are connected as amino acid residues within the breakdown products of the antibody, displaying low activity in the general chemical and enzymatic environments within the body, ensuring high plasma stability. Typically, non-cleavable linkers rely on enzyme hydrolysis of the ADC’s antibody component, primarily facilitated by proteases, culminating in the release of the payload in a complex form.

1.4. Cytotoxic Payloads

The cytotoxic payload is the component of ADCs that signifies the drug’s cytotoxic effect upon penetration into cancer cells. Given that only approximately 2% of ADCs can reach the targeted tumor site after intravenous administration, it is imperative to employ a highly effective compound as the payload. This compound should demonstrate stability under physiological conditions and possess functional groups capable of binding to antibodies. Currently, cytotoxic payloads used in ADCs primarily include potent tubulin inhibitors, DNA-damaging agents, and immunomodulators [14,15]. These compounds are selected for their capacity to exert a robust therapeutic effect within cancer cells. Tubulin inhibitors disrupt microtubule dynamics, affecting cell division; DNA-damaging agents induce DNA damage to inhibit cell proliferation, and immunomodulators modulate the immune response within cancer cells. The meticulous choice of the cytotoxic payload is crucial for attaining the desired therapeutic outcomes in ADCs [16,17,18,19] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Representative small molecular cytotoxic payloads [19].

1.5. Conjugation Methods

In addition to the selection of antibodies, linkers, and payloads, the method by which the small-molecule component (e.g., linker plus payloads) is attached to the antibody is a crucial element in the successful construction of ADCs [20,21,22]. Antibodies typically contain residues for binding reactions, such as lysine and cysteine residues. In the early development of ADC drugs, conventional coupling methods often used existing lysine or cysteine residues on the antibody through appropriate coupling reactions [23,24]. One of the most commonly used methods for connecting the payload to the lysine residues of the antibody is through the amide coupling reaction, using an active carboxylic acid ester [25,26,27]. However, the abundant presence of lysine complicates the control of site selectivity, resulting in challenges such as premature payload release and the potential for off-target toxicity.

To address these limitations, innovative strategies for ADCs, including site-specific conjugation methods, are currently in development [28,29,30,31]. Site-specific conjugation methods present a groundbreaking approach in ADC development, aiming to precisely attach the payload at specific locations and overcome challenges associated with traditional coupling methods. For example, the introduction of engineered reactive cysteine residues selectively inserted at specific positions enables precise conjugation at that site, enhancing the homogeneity of ADCs and providing tunable reactivity through the alteration of the modification site [32,33,34]. In enzymatic conjugation methods, a variety of enzymes, such as bacterial-derived formyl glycine-generating enzymes, transglutaminases, glycotransferases, and sortases, have been utilized for tag-free antibody modification techniques [35,36,37,38,39]. The reaction sites of antibodies are designed to specifically interact with the corresponding functional groups, facilitating site-specific conjugation in enzymatic methods. The incorporation of unnatural amino acids with bioorthogonal groups is also employed in site-specific conjugation [40,41,42,43]. The most common method of incorporation involves engineering transfer RNA synthetases to recognize the unnatural amino acids, resulting in the genetic coding of these unconventional building blocks. Enzymatic conjugation methods provide precise control over the site of conjugation, reducing heterogeneity and enhancing the therapeutic index of ADCs. Tag-free techniques, particularly those based on enzymatic modification, often yield conjugates with reduced immunogenicity.

2. Trends in Biopharmaceutical Market and Development of ADC Therapies

2.1. Global Trends in Biopharmaceutical Market

The global pharmaceutical market continues to grow, with a projected compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of approximately 6.9%, increasing from around USD 844 billion in 2019 to an estimated USD 1.181 trillion in 2024 [44]. The advancement in biotechnological technologies has led to a trend of focusing more on the development of biopharmaceuticals rather than synthetic drugs. Among these, the market for monoclonal antibody drugs is particularly noteworthy. The share of biopharmaceuticals in the overall pharmaceutical market has steadily increased, rising from 18% (USD 129 billion) in 2010 to 28% (USD 243 billion) in 2018. It is anticipated to continue growing, reaching an estimated 32% with a CAGR of 8.5% by 2024 [45]. The global biopharmaceutical market is led by the United States, accounting for 61% of sales in 2020. The major European countries (Germany, France, Italy, the UK, Spain) collectively hold a 17% share, while Asian countries such as Japan (5%) and China (3%) rank within the top five in market share. Within the pharmaceutical market, the oncology sector is recognized as the largest, driven by an increasing incidence of cancer worldwide [46].

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), global cancer cases reached 19.3 million in 2020, projected to rise by 47% to 28.4 million by 2040 [47]. In response to this growing cancer prevalence, global spending on oncology drugs, as estimated by IQVIA, is expected to grow at a CAGR of 9~12% from USD 164 billion in 2020 to USD 269 billion in 2025 [48]. Specifically, the ADC market witnessed substantial growth, reaching USD 7.35 billion in 2022, reflecting a 34.9% increase compared to USD 5.45 billion in the previous year [49]. The ADC market is projected to continue its robust growth at an average annual rate of 25.4%, reaching a total revenue of USD 28.53 billion by 2028.

2.2. Global Trends in Approval and Development of ADC Therapies

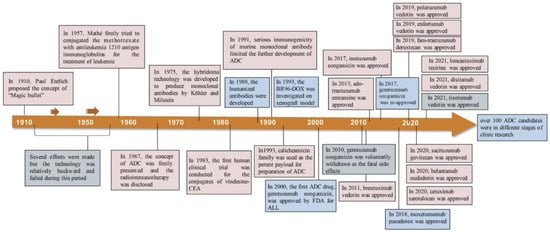

Innovative concepts and the careful design of chemical linkers for the creation of payload-conjugated therapies have led to significant advancements. In the year 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted approval for the first ADC therapy, Mylotarg®, intended for patients with acute myeloid leukemia [19]. This milestone marked the initiation of the ADC therapy market dedicated to cancer treatment. As of December 2021, a total of 14 ADC therapies have received global approval for the treatment of solid tumors and hematologic cancers. Presently, there are over 100 ADC candidates in various stages of clinical trials [19]. The evolution of the conceptualization and development processes of ADC therapies over the past century, dating back to 1910, is visually depicted in the diagram [1], as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Timeline depicting important events in the development and approval of ADC drugs over the past century since the ‘magic bullet’ was proposed by Paul Enrlich in 1910 [1]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature.

The approval status of ADC therapies for the treatment of hematologic malignancies is outlined below. Commencing with Adcetris, designed to target CD30 and granted approval in 2011, a cumulative total of seven therapies for hematologic cancers have received approval. Notable manufacturers include Seagen, GSK, and Pfizer, among others. The payload substances employed encompass Monomethyl auristatin E/F, Calicheacmicin, and others, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

ADC drugs approved for hematologic malignancies [49].

Furthermore, following the approval of Kadcyla, which targets HER2 for solid tumors, in 2013, seven ADC therapies have received approval. Prominent manufacturers involved in these approvals include Roche, Daiichi Sankyo, Immunomedics, Seagen, and others [49]. The intellectual property (IP) landscape of these major manufacturers will be delved into in more detail in the subsequent sections, as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

ADC drugs approved for solid tumors [49].

Specifically, Kadcyla has exhibited effective therapeutic outcomes in HER2-positive breast cancer by selectively delivering the drug to tumor cells, thereby minimizing its impact on surrounding normal cells [50,51]. Adcetris, employed in Hodgkin’s lymphoma and CD30-positive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, demonstrates notable efficacy against specific positive tumors while concurrently reducing the impact on normal cells [50,52]. However, severe side effects may manifest in some patients, and treatment effectiveness could vary based on the cancer type. Enhertu has proven effective in treating various cancer types, including HER2-positive breast cancer, indicating a considerable potential for diverse cancer treatments. Nevertheless, some patients may experience moderate to severe side effects, and the specificity for HER2-negative tumors may be compromised [50,53,54].

Significantly, since its approval by the U.S. FDA in 2013, Kadcyla has been administered to HER2-positive breast cancer patients, delivering effective therapeutic outcomes by amalgamating the advantages of conventional antibody treatments and chemotherapy [50,51]. The targeted delivery of the drug resulted in a significant reduction in tumor size and improved overall survival. However, common drawbacks of ADC therapies, such as potential side effects and the development of drug resistance in some patients, persist. Ongoing research and development endeavors aim to enhance efficacy and minimize adverse effects in the realm of ADC therapy [16,22,55].

The majority of ADC developers are embracing collaborative development strategies to exchange technology and resources, facilitating mutual expansion, particularly in the field of oncology therapies. The noteworthy partnerships and collaborations poised for significance in 2022 and 2023 are outlined in Table 4.

Table 4.

The majority of ADC developers and their collaborations [49,56,57,58,59,60].

Table 5 exhibits the summary of key patents for 11 FDA-approved ADC drugs. Among the ADC drugs approved by the FDA, four drugs (Adcetris, Polivy, Padcev, and Tivdak) utilized vedotin, comprising the MC-VC-PABC linker and MMAE cytotoxin, as outlined in US Patent 7,659,241 filed in 2003. Blenrep employed the MMAF cytotoxin (US Patent 7,662,387 filed in 2004), an analog of MMAE found in vedotin. On the other hand, ozogamicin was used as a linker cytotoxin in Mylotag and Besponsa drugs. In 2013, two patents, US Patent 10,195,288 and 9,028,833, were filed for the camtothecin-based deruxtecan and govitecan used in Enhertu and Trodelvy drugs [61].

Table 5.

Patent landscapes of 11 FDA-approved ADC drugs [61].

Notably, while the four ADC drugs employed the same vedotin, they are each covered by distinct patents for their unique ADC formulas, which include different antibodies and target antigens. The filing years for these formula patents span a decade, with the earliest being US Patent 7,659,241 filed in 2004 and the latest being US Patent 10,617,764 filed in 2014. Additionally, the Mylotag and Besponsa drugs, both based on ozogamincin, were each protected by different formula patents (US Patent 5,712,374 filed in 1995 and 8,153,768 filed in 2003). Furthermore, additional patents for the ozogamin-based ADC formula were filed in 2012 and 2014.

The patent filing trends for the vedotin- and ozogamicin-based ADC drugs demonstrate that, although the individual components such as linkers, cytotoxins, and antibodies may originate from established technologies, the innovation can be achieved by developing novel ADC formulas through the combination of these elements. This strategy has the potential to advance the ADC technology and broaden its practical uses.

The general duration of patent protection is 20 years from the filing date. Therefore, it can be assumed that the patents for the ADC drugs with FDA approvals listed in Table 5 and filed before 2003 have expired as of January 2024. However, various strategies such as patent term extension, dosage patents [62], and second medical use patents [63] can be employed to secure exclusive rights beyond the initial patent duration for the ADC drugs.

For example, US Patent 7,659,241, filed on 31 July 2003, for the Adcetris drug, had its duration extended until July 15, 2026, through the patent term extension [64]. On the other hand, Roche filed a new dosage patent for the Kadcyla drug with the EPO in 2010 and received European Patent 2,459,167B1 in 2013 [62,65]. This allowed Roche to extend its exclusive rights for Kadcyla in Europe until 2030. The University of California has discovered a second medical use for an antibody produced by the hybridoma deposited as ATCC Deposit No. PTA-5817, resulting in the grant of European Patent 1,734,996B1 [63,66].

2.3. The Recent Clinical Status and Innovative Studies of ADCs

Between 2019 and 2022, the FDA granted approval to eight ADC drugs. In the year 2022 alone, 57 novel ADCs commenced phase 1 clinical trials, reflecting a notable 90% surge in comparison to the previous year, 2021. Additionally, the initiation of 249 new clinical trials to assess ADCs in 2022 represented a substantial 35% increase compared to the activities in 2021 [67].

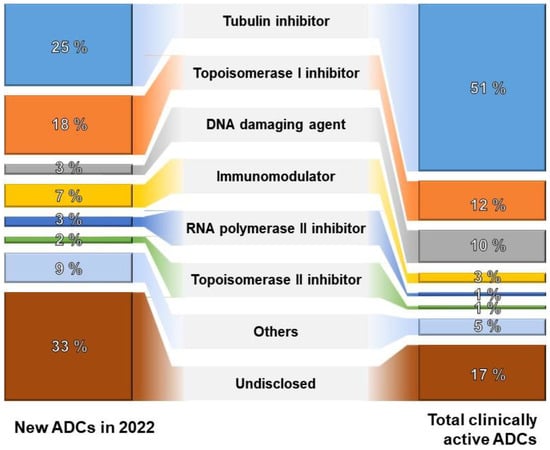

Over the last two decades, substantial investments have been allocated to various components of antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), encompassing antibodies, conjugation methods, linkers, and payloads. Conjugation methods aim to produce stable and uniform ADC products, with the field of linkers experiencing significant innovation, currently employing 33 in ongoing clinical trials. Moreover, there is notable interest in investing in over 60 novel payloads at the clinical stages of ADC development. As of 2022, merely 25% of emerging ADCs employ tubulin inhibitors as their primary mechanism of action. This trend signifies a diversification of technologies and suggests potential advancements in more effective mechanisms of action, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The proportion of ADCs by mechanism of action [67].

On the contrary, a pivotal factor associated with the adverse effects of ADC therapy pertains to the premature liberation of the payload within the organism. Inadequate antigen expression on tumors leads to insufficient toxin delivery and drug resistance. Meanwhile, excessive antigen expression on normal healthy tissues causes on-target but off-tumor toxicity. Furthermore, ADC antibodies may induce immune-related adverse effects. Prevalent toxicities noted in clinical observations encompass thrombocytopenia, anemia, neutropenia, and leukopenia, with hepatotoxicity being the most predominant [68].

To address these side effects and enhance therapeutic efficacy, various emerging ADC formats have been developed, including bispecific ADCs, conditionally active ADCs known as probody–drug conjugates, immune-stimulating ADCs, and protein-degrader ADCs [69]. Each ADC format offers unique capabilities for addressing different challenges. For instance, probody therapeutics represent a novel class of recombinant antibody-based therapeutics targeting antibody activity to the tumor by exploiting the dysregulation of proteases in disease tissues. Probody–drug conjugates consist of several components, including a parental antibody, the prodomain (comprising a masking peptide linked to the N-terminus of the light chain of the parental antibody via a protease substrate), and finally, the linker/toxin [70,71]. Bispecific ADCs involve a bispecific antibody, allowing simultaneous engagement of two different targets by a single antibody-like molecule, and an ADC, facilitating the cancer-selective delivery of potent cytotoxic payloads [72,73]. Probody–drug conjugates are anticipated to improve tumor specificity, while bispecific ADCs have the potential to combat drug resistance and tumor heterogeneity. In the near future, a combination of technologies may be required to achieve the broadest therapeutic window.

Furthermore, the development of new payloads has paved the way for innovative non-cytotoxic payloads in ADCs. Examples of such payloads include RNA inhibitors, immune agonists, and apoptosis-promoting Bcl-xL inhibitors. In particular, immune agonists, such as Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists, stimulators of the interferon gene (STING) agonists, and glucocorticoid receptor modulators, represent a promising class of payloads aiming to achieve therapeutic effects through the precision of antibody-guided targeting with the immunomodulatory capabilities of small molecules [74,75,76]. Immune-agonist ADCs leverage antibodies to deliver immune agonists to the tumor microenvironments and release them locally. This approach is anticipated to enhance the antitumor immune response. Notably, TLRs, STING, and other immune agonists play crucial roles in modulating the immune system [77,78,79]. The preliminary clinical results of these immune-agonist ADCs have shown promising potential for a novel therapeutic approach but simultaneously underscored the necessity for meticulous investigation to confirm their safety. For example, 209P interim results for the phase I/Ib study of SBT6050, which comprised a TLR8 agonist linker payload-conjugated to a HER2-directed antibody, indicated a manageable safety profile and pharmacodynamics suggestive of myeloid, NK, and T-cell activation when SBT6050 was administered alone or in combination with pembrolizumab [80]. The phase 1 clinical trial of XMT-2056, which consisted of a HER2-targeted antibody conjugated with a STING agonist payload, was voluntarily suspended in March 2023 due to a significant Grade 5 adverse event [81]. Subsequently, the trial suspension was lifted in October 2023 after reducing the starting dose in the phase 1 dose escalation design of XMT-2056 [82]. Therefore, continued research and clinical development are imperative to comprehensively comprehend and harness the therapeutic advantages of these emerging payloads in ADCs.

3. Biopharmaceutical Patent Trends and ADC Therapy Technology

3.1. Worldwide Biopharmaceutical Patent Trends

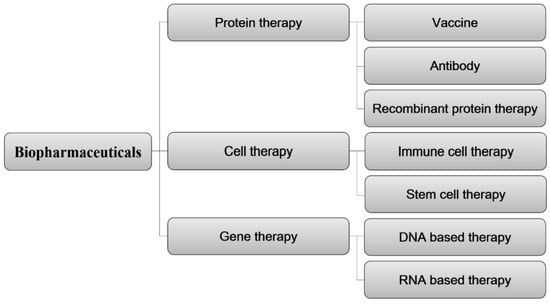

Biopharmaceuticals are broadly classified based on the biological materials employed as active ingredients, as depicted in Figure 4. This classification includes protein therapies, cell therapies, and gene therapies. Within the realm of protein therapies, further distinctions can be made, encompassing vaccines, antibodies, and recombinant protein therapies. From a material standpoint in the patent technology classification, ADC therapies are considered part of the protein therapy technology.

Figure 4.

Classification of biopharmaceutical patent technology based on core technologies of biological materials.

To analyze patent trends in biopharmaceuticals, key keywords were identified for protein recombinants, antibodies, vaccines, and cell therapies. Subsequently, patent information was categorized based on these key terms, as detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Core technologies of biopharmaceutical patents and search keywords.

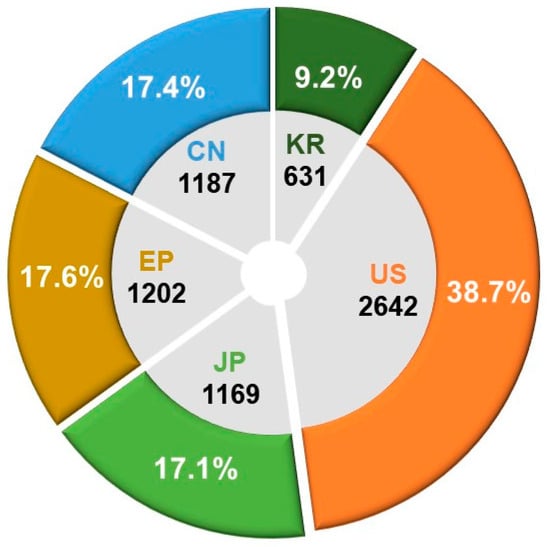

An in-depth analysis was conducted on the patent application trends over the past two decades at the primary patent offices of the United States (USPTO), Europe (EPO), China (CNIPA), Japan (JPO), and South Korea (KIPO). The objective was to gain insights into overall market trends and conduct a comprehensive analysis of the technological landscape in the field. Among a total of 6831 patent applications, the United States (US) constituted 38.7% of the overall applications, with Europe (EP), China (CN), and Japan (JP) holding 17.6%, 17.4%, and 17.1%, respectively. South Korea (KR) contributed 9.2% to the total application count. Figure 5 visually depicts the distribution and proportion of patent applications for biopharmaceutical technologies across the major countries’ patent offices during the last two decades.

Figure 5.

Patent office-specific counts and proportions of patent applications for biopharmaceutical technologies.

In the examination of technology-specific distribution, the CPC classification code A61K48/00, involving medicinal preparations containing genetic material for the treatment of genetic diseases through insertion into living body cells, holds the highest number of patents, totaling 3941. Additionally, A61P35/00 (antitumor agents) and C12N15/86 (DNA related to mutations or genetic engineering, encompassing recombinant DNA technology and vectors for introducing foreign genetic material, specifically designed for host cells, especially eukaryotic cells, and virus vectors) show distributions of 2713 and 2033 patents, respectively. Following closely, A61K38/00 (medicinal preparations containing peptides) and A61K2039/505 (composition of antibodies, pharmaceutical compositions containing antigens or antibodies) exhibit distributions of 1528 and 1429 patents, respectively. This suggests the dominance of gene therapy and protein therapy technologies in the patent landscape.

An analysis of the recent research and development activities in biopharmaceuticals reveals Switzerland leading with the highest activity at 49.5%, followed by Germany at 41.8% and South Korea at 40.3%. Recent activity serves as an indicator of changes in patent application activity over the past four years within the overall twenty-year analysis period, offering insights into the concentration of research and development based on the recent activities of patent applicants.

3.2. Global Patent Landscape in ADC Therapies

An analysis was conducted on patent applications and registrations pertaining to ADC therapies spanning from 1 January 2000 to 13 November 2023. The examination utilized publicly available data from the patent offices of the United States, Japan, Europe, China, and Korea. The technological classification system for ADC therapies comprises the primary category ‘antibody drug conjugates’ with sub-technologies focusing on ‘linker and payload’. A comprehensive patent trend analysis was performed, leveraging pertinent and effective patent data for each classification.

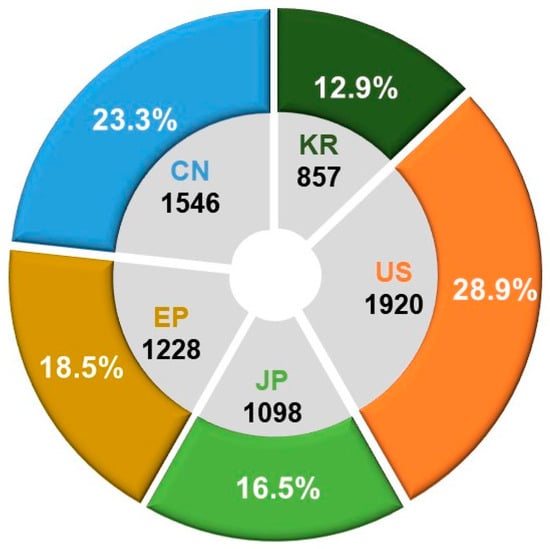

The key terms employed for technology classification and search criteria are delineated in Table 7. In our annual analysis of patent application trends across major patent offices, we aimed to understand overall technological market trends and conduct a comparative analysis of the technological positions held by each country in the specified field. Based on a total of 6649 patent applications, the findings indicate that the United States dominates with the highest share at 28.9%, followed by China at 23.3%, Europe at 18.5%, Japan at 16.5%, and Korea at 12.9%. This analysis contributes insights into the global technological landscape and the relative positions of countries within the designated technology domain (see Figure 6).

Table 7.

Core technologies of ADC patents and search keywords.

Figure 6.

Patent office-specific counts and proportions of patent applications for ADC technologies.

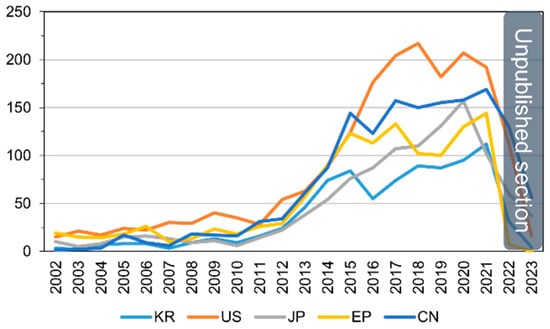

Analyzing the annual patent application trends, a total of 6649 applications were filed over the past two decades. There is an average annual increase of 15.3%, with applications growing from 38 in 2002 to 719 in 2021. Notably, for patents simultaneously filed in three or more of the countries (United States, Europe, China, Japan, and Korea), the trend reflects the overall increase in patent applications, exhibiting an average annual growth of 15.5%, rising from 23 in 2002 to 354 in 2021. The trajectory of patent applications by major countries for ADC therapies over the years is visually presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Patent application trends for ADC therapies by patent office.

In our analysis of the detailed distribution of ADC therapy technologies using the CPC classification, the majority of patents, totaling 4264, fall under A61P35/00 (antitumor agents). Furthermore, patents are distributed across specific categories: 3443 under A61K47/6803 (pharmaceutical preparations with characteristics in the active ingredients used: drug–antibody defined by pharmacological or therapeutic activity), 2333 under A61K47/6849 (pharmaceutical preparations with characteristics in the active ingredients used: antibodies targeting receptors, cell surface antigens, or cell surface determinants), 1890 under A61K2039/505 (composition of antibodies: pharmaceutical compositions containing antigens or antibodies, substances for immune analysis), and 1841 under A61K47/6851 (pharmaceutical preparations with characteristics in the active ingredients used: antibodies targeting determinants of tumor cells).

3.3. Analysis of Key Patent Applicants and Market Viability in ADC Therapy

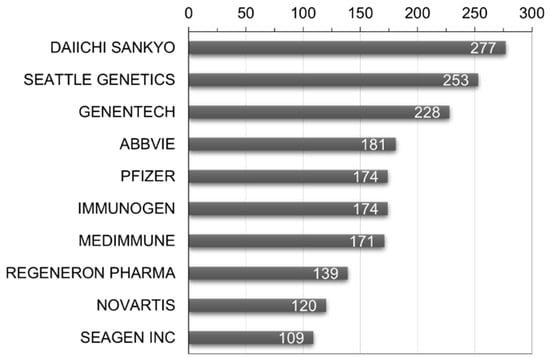

To identify key players in the ADC therapy field, a global patent applicant analysis was conducted. As shown in Figure 8, Daiichi Sankyo Inc. leads with 277 patent filings, followed by Seattle Genetics Inc. (Bothell, WA, USA) with 253 and Genentech Inc. with 228. To analyze market viability, the ratio of triadic patents and its relevance as an indicator of major market presence was examined. The results indicate that Japan has the highest ratio at 77.4%, suggesting the strongest inclination for international market penetration. Denmark follows at 77.0% and France at 73.9%. This analysis provides insights into the extent of global rights acquisition.

Figure 8.

World’s major patent applicants and number of patent filings in ADC therapy.

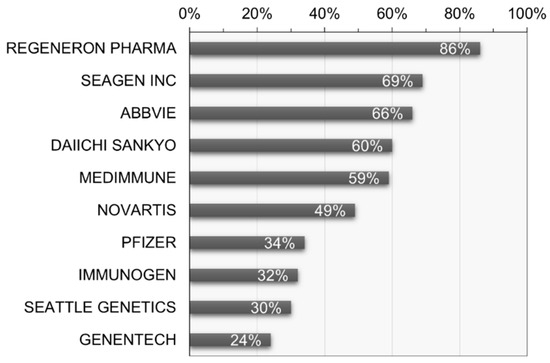

Furthermore, analysis of the recent activity reveals that Denmark exhibits the highest research and development activity at 70.5%, followed by Japan at 61.7% and Korea at 55.6%. In terms of recent activity by applicant, Regeneron Pharma Inc. (Tarrytown, NY, USA) stands out with the highest activity at 85.6%, followed by Seagen Inc. (USA) and AbbVie Inc. (Chicago, IL, USA) at 68.8% and 66.3%, respectively (see Figure 9). This allows for an understanding of the research and development concentration based on the recent activity of key applicants.

Figure 9.

Recent research and development activity of key patent applicants in ADC therapy.

3.4. Analysis of Key Technological Patent Portfolios in ADC Therapy

An analysis of technological capabilities based on the major patent portfolios of the world’s key patent applicants in ADC therapy was conducted. Firstly, Regeneron Pharma Inc. (USA) has filed a total of 4576 patents over 20 years, holding 132 patents in the field of ADC therapy, indicating a research and development concentration of 2.88% in the ADC therapy field. In the recent 5 years, they have filed 119 patents in the ADC therapy field, suggesting ongoing research and development and patent rights activities. The research and development concentration in the last 5 years is calculated at 57.98%. The calculation formula and the patent holding status of Regeneron Pharma Inc. are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Regeneron Pharma Inc. (USA) patent portfolio and degree of technology and R&D concentration.

Regeneron Pharma Inc. holds various patents related to ADC therapy, encompassing Verrucarin A derivatives and ADCs, protein–drug conjugates, Rifamycin analogs and ADCs, cyclodextrin protein–drug conjugates, and anti-MUC16 ADCs. These patents cover diverse drug payloads and conjugation technologies with specific antibodies. Regeneron Pharma Inc. has applied for or holds patents in the United States, Japan, Korea, and other countries for ADC formulations utilizing these technologies. The primary patents held by Regeneron Pharma Inc. are detailed in Table 9.

Table 9.

List of ADC-therapy-related patents held by Regeneron Pharma Inc. (USA).

Looking at the patent portfolio of Seagen Inc. related to ADC therapy, they have filed a total of 167 patents over the past 20 years. In the field of ADC therapy, they hold 91 patents, indicating a technological concentration of 54.49%. Particularly noteworthy is their recent activity, with 76 patent applications in the ADC therapy field over the last 5 years, suggesting ongoing research and development efforts and active patenting. The degree of R&D concentration in the ADC therapy field for the recent 5-year period is calculated at 83.52% (see Table 10).

Table 10.

Seagen Inc. (USA) patent portfolio and degree of technology and R&D concentration.

Examining the recent patents held by Seagen Inc. reveals a focus on various improvements and inventions related to different elements of ADC therapy. These include combination therapy, modulating the immune response, hydrophilic antibody–drug conjugates, B7-H4 ADCs, anti-PD-1 antibody in combination with anti-CD30 antibody, and β-glucuronidase-linker–drug conjugates. Seagen Inc.’s major patent list is provided in Table 11.

Table 11.

List of ADC-therapy-related patents held by Seagen Inc. (USA).

An analysis of the status of patent rights transfers has revealed a unique aspect of Seagen Inc. The company has established collaborative relationships with several research institutions for the development of ADC therapies. Seagen Inc. maintains cooperative research relationships through patent rights transfers with Seattle Genetics (USA) and Agensys Inc. (USA). The current status of patents related to collaborative research and joint research institutions for Seagen Inc. is presented in Table 12.

Table 12.

Seagen Inc.’s joint research patents and collaborative research institutions related to ADC therapies.

Next, we examined the patent portfolio of AbbVie Pharmaceuticals Inc. (USA), one of the major applicants, related to ADC therapies. AbbVie Pharmaceuticals has filed a total of 2851 patents over 20 years, possessing 170 patents in the field of ADC therapies, indicating a technological concentration of 5.96%. In particular, in the last 5 years, the number of patent applications in the ADC therapy field was 121, representing a recent research and development concentration of 71.18%. This suggests a notable focus on research and development in the field of ADC therapies (see Table 13).

Table 13.

AbbVie Pharmaceuticals Inc. (USA) patent portfolio and degree of technology and R&D concentration.

We have also examined the recent technological content of AbbVie Pharmaceuticals’ patent holdings. The company has shown a focus on research and development, particularly in improving antibody technologies and drug conjugates. Specific areas of concentration include anti-EGFR antibody–drug conjugates, anti-c-Met ADCs, anti-EGFR ADC formulations, anti-CD98 ADCs, and anti-c-met ADCs. The key patent list held by AbbVie Pharmaceuticals is presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

List of ADC-therapy-related patents held by AbbVie Pharmaceuticals Inc. (USA).

Pfizer Inc. (USA), a company with multiple approved ADC therapy products and a stronghold on core strategic technologies in this field, has a significant patent portfolio. Over the last 20 years, Pfizer has filed 7555 patents, with 172 patents in the ADC therapy domain, indicating a technology concentration of 2.28%. Notably, in the recent five years, Pfizer has filed 60 patents in the ADC therapy domain, reflecting a recent R&D concentration of 34.88%. While the recent technology concentration may seem relatively low, Pfizer holds a substantial quantitative competitiveness and technological advantage. This suggests that Pfizer maintains a focus on research and development in the ADC therapy field (Table 15).

Table 15.

Pfizer Inc. (USA) patent portfolio and degree of technology and R&D concentration.

Analyzing the recent technological content of Pfizer’s patents reveals a concentration on the research and development of therapeutic antibodies and their applications, including cytotoxic peptides and antibody–drug conjugates, anti-PTK7 ADCs, bifunctional cytotoxic agents, therapeutic antibodies, spliceostatin analogs, and methods. Pfizer’s major patent holdings are presented in Table 16.

Table 16.

List of ADC-therapy-related patents held by Pfizer Inc. (USA).

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) therapy emerges as a transformative technology, surmounting the constraints of traditional chemotherapy by leveraging targeted antibodies. Through extensive research and development, the fusion of diverse antibodies and cytotoxic payloads provides avenues for treating various cancer types. Presently, numerous pharmaceutical entities are leveraging ADC therapy to advance novel drugs, progressing through clinical trials. Over the last two decades, ADC therapy has witnessed remarkable strides, securing approvals for diverse cancer targets. The development of numerous ADC therapies, addressing hematologic and solid tumors, is reflected in the multitude of candidates currently undergoing clinical trials, pivotal for assessing efficacy and safety. The past five years have marked a substantial upswing in research and development concentration and patent filings concerning ADC therapy. Leading this technological frontier are notable patent applicants, including Pfizer Inc. (USA), AbbVie Pharmaceuticals Inc. (USA), Regeneron Pharma Inc. (USA), and Seagen Inc. (USA), steering advancements in the field.

ADC technology, while brimming with promise for cancer treatment, faces significant challenges that impact its clinical success. These challenges encompass antigen expression discrepancies, tumor heterogeneity, off-target toxicities, immunogenicity, and pharmacokinetic hurdles. Effectively addressing these issues necessitates a multidisciplinary approach involving molecular biology, pharmacology, and clinical medicine. Ongoing research and innovations in ADC technology strive to overcome these obstacles by reinforcing antibody stability, optimizing payload selection, refining linker conjugation methods, and exploring synergies with nanotechnologies. Collaborative efforts across scientific disciplines are indispensable, playing a pivotal role in unlocking the full potential of ADCs in cancer treatment. This sustained collaboration aims to deepen our understanding of challenges and opportunities, ultimately driving advancements that elevate the efficacy and safety of ADCs in the battle against cancer.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.; literature study, Y.C. (Youngbo Choi) and Y.C. (Youbeen Choi); methodology and analysis, Y.C. (Youngbo Choi); investigation, S.H. and Y.C. (Youngbo Choi); data curation, S.H. and Y.C. (Youngbo Choi); writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.C. (Youngbo Choi); visualization, Y.C. (Youbeen Choi); supervision, S.H.; project administration, S.H.; funding acquisition, S.H. and Y.C. (Youngbo Choi). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research described in this work received support from the National Research Foundation of Korea (2022R1F1A10738471212782127670102, 2022R1F1A1074443) and the Korea Technology and Information Promotion Agency for SMEs (TIPA), funded by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (G21S330218702).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The manuscript submitted here has not been published or presented elsewhere, either in part or in its entirety, and is not currently under consideration by any other journal. We have thoroughly reviewed and understood the policies of your journal, and we affirm that this manuscript and the study described within it comply with these policies. Additionally, we declare that there are no conflicts of interest associated with this submission.

References

- Fu, Z.; Li, S.; Han, S.; Shi, C.; Zhang, Y. Antibody drug conjugate: The “biological missile” for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khongorzul, P.; Ling, C.J.; Khan, F.U.; Ihsan, A.U.; Zhang, J. Antibody–drug conjugates: A comprehensive review. Mol. Cancer Res. 2020, 18, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafeez, U.; Parakh, S.; Gan, H.K.; Scott, A.M. Antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Molecules 2020, 25, 4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan, N.; Setua, S.; Kashyap, V.K.; Khan, S.; Jaggi, M.; Yallapu, M.M.; Chauhan, S.C. Antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy: Chemistry to clinical implications. Pharmaceuticals 2018, 11, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esapa, B.; Jiang, J.; Cheung, A.; Chenoweth, A.; Thurston, D.E.; Karagiannis, S.N. Target antigen attributes and their contributions to clinically approved antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) in haematopoietic and solid cancers. Cancers 2023, 15, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammood, M.; Craig, A.W.; Leyton, J.V. Impact of endocytosis mechanisms for the receptors targeted by the currently approved antibody-drug conjugates (ADCS)—A necessity for future adc research and development. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Zhang, H.; Guan, R. Bioactivity of recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody against HER2 in-vivo and in-vitro and its mechanism of action in ovarian cancer. Transl. Cancer Res. 2023, 12, 1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Fang, L.; McGowen, K.; Yin, J.; Bowman, J.; Ku, A.T.; Alilin, A.N.; Corey, E.; Roudier, M.P.; True, L.D.; et al. Tumor-derived biomarkers predict efficacy of B7H3 antibody-drug conjugate treatment in metastatic prostate cancer models. J. Clin. Investig. 2023, 133, e162148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Huang, J.; Zhu, B.; Huang, A.C.; Jiang, L.; Fang, J.; Moses, M.A. A rationally designed ICAM1 antibody drug conjugate eradicates late-stage and refractory triple-negative breast tumors in vivo. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eabq7866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargh, J.D.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Parker, J.S.; Spring, D.R. Cleavable linkers in antibody–drug conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 4361–4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobson, A.D.; Xu, J.; Marvin, C.C.; McPherson, M.J.; Hollmann, M.; Gattner, M.; Dzeyk, K.; Fettis, M.M.; Bischoff, A.K.; Wang, L.; et al. Optimization of Drug-Linker to Enable Long-term Storage of Antibody–Drug Conjugate for Subcutaneous Dosing. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 9161–9173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheyi, R.; de la Torre, B.G.; Albericio, F. Linkers: An Assurance for Controlled Delivery of antibody-drug conjugate. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Z.; Xiao, D.; Xie, F.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, S. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in linker chemistry. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3889–3907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Gou, L.; Li, W.; Wang, Y. Antibody–drug conjugates: Recent advances in payloads. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 4025–4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, S.; Ma, P.; Jiang, Y.; Cheng, K.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Miao, H.; Tang, Q.; Liu, F.; et al. Drug conjugate-based anticancer therapy-Current status and perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2023, 552, 215969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, J.Z.; Modi, S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the potential of antibody–drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurwitz, J.; Haggstrom, L.R.; Lim, E. Antibody–drug conjugates: Ushering in a new era of cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anami, Y.; Otani, Y.; Xiong, W.; Ha, S.Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Rivera-Caraballo, K.A.; Zhang, N.; An, Z.; Kaur, B.; Tsuchikama, K. Homogeneity of antibody-drug conjugates critically impacts the therapeutic efficacy in brain tumors. Cell Rep. 2022, 39, 110839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J. Review of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Korean J. Med. 2023, 98, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, P.M.; Rabuka, D. Recent developments in ADC technology: Preclinical studies signal future clinical trends. BioDrugs 2017, 31, 521–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillow, T.H.; Sadowsky, J.D.; Zhang, D.; Yu, S.F.; Rosario, G.D.; Xu, K.; He, J.; Bhakta, S.; Ohri, R.; Kozak, K.R.; et al. Decoupling stability and release in disulfide bonds with antibody-small molecule conjugates. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghoubi, S.; Karimi, M.H.; Lotfinia, M.; Gharibi, T.; Mahi-Birjand, M.; Kavi, E.; Hosseini, F.; Sineh Sepehr, K.; Khatami, M.; Bagheri, N.; et al. Potential drugs used in the antibody–drug conjugate (ADC) architecture for cancer therapy. J. Cell. Physiol. 2020, 235, 31–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiki, A.; Vaidya, S.R.; Abdollahi, M.; Bhardwaj, G.; Dolan, M.E.; Turna, H.; Arora, V.; Sanjeev, A.; Robinson, T.D.; Koid, A.; et al. Site-specific conjugation of native antibody. Antib. Ther. 2020, 3, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyer, B.; Schuster, M.; Jungbauer, A.; Lingg, N. Microheterogeneity of recombinant antibodies: Analytics and functional impact. Biotechnol. J. 2018, 13, 1700476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuchikama, K.; An, Z. Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries. Protein Cell 2018, 9, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heh, E.; Allen, J.; Ramirez, F.; Lovasz, D.; Fernandez, L.; Hogg, T.; Riva, H.; Holland, N.; Chacon, J. Peptide Drug Conjugates and Their Role in Cancer Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidi, F.; Jenjob, R.; Crespy, D. Designing smart polymer conjugates for controlled release of payloads. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3965–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q. Site-Specific Antibody Conjugation with Payloads beyond Cytotoxins. Molecules 2023, 28, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.; Forte, N.; Baker, J.R. Site-selective lysine conjugation methods and applications towards antibody–drug conjugates. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 10689–10702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.J.; Bargh, J.D.; Dannheim, F.M.; Hanby, A.R.; Seki, H.; Counsell, A.J.; Ou, X.; Fowler, E.; Ashman, N.; Takada, Y.; et al. Site-selective modification strategies in antibody–drug conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 1305–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okojie, J.; McCollum, S.; Barrott, J. The Future of Antibody Drug Conjugation by Comparing Various Methods of Site-Specific Conjugation. Discov. Med. 2023, 35, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Haight, A.; Welch, D.; Han, L. Selective Reduction of Cysteine Mutant Antibodies for Site-Specific Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Bioconjug. Chem. 2023, 34, 2293–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Qiu, D.; Shi, J.; Wang, N.; Li, M.; Wu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Bu, X.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Y.; et al. In-Depth Structure and Function Characterization of Heterogeneous Interchain Cysteine-Conjugated Antibody–Drug Conjugates. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 7, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, W.; Maza, J.C.; Chernyak, N.; Flygare, J.A.; Krska, S.W.; Toste, F.D.; Francis, M.B. Modification of Cysteine-Substituted Antibodies Using Enzymatic Oxidative Coupling Reactions. Bioconjug. Chem. 2023, 34, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamazaki, S.; Matsuda, Y. Tag-free enzymatic modification for antibody-drug conjugate production. ChemistrySelect 2022, 7, e202203753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debon, A.; Siirola, E.; Snajdrova, R. Enzymatic Bioconjugation: A Perspective from the Pharmaceutical Industry. JACS Au 2023, 3, 1267–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Seki, T.; Shikida, N.; Iwai, Y.; Ooba, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Isokawa, M.; Kawaguchi, S.; Hatada, N.; et al. AJICAP Second Generation: Improved Chemical Site-Specific Conjugation Technology for Antibody–Drug Conjugate Production. Bioconjug. Chem. 2023, 34, 728–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaramillo, M.L.; Sulea, T.; Durocher, Y.; Acchione, M.; Schur, M.J.; Robotham, A.; Kelly, J.F.; Goneau, M.F.; Robert, A.; Cerepo-Donates, Y.; et al. A glyco-engineering approach for site-specific conjugation to Fab glycans. In Mabs; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2023; Volume 15, p. 2149057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nittoli, T.; Degrado, S.J.; Afsari, H.S.; Anand, P.; Bos, J.; Choi, S.; Mallett, E.; Markotan, T.; Spink, J.; Vega, M.; et al. Site-specific antibody conjugations using bacterial transglutaminase and the Diels-Alder cycloaddition reaction. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyak, E.L.; Alferova, V.A.; Korshun, V.A.; Sapozhnikova, K.A. Introduction of Carbonyl Groups into Antibodies. Molecules 2023, 28, 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, C.; Sauter, P.F.; Klasen, B.; Waldmann, C.; Pektor, S.; Bausbacher, N.; Lemke, E.A.; Miederer, M. Genetic Code Expansion for Site-Specific Labeling of Antibodies with Radioisotopes. ACS Chem. Biol. 2023, 18, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Luo, F.; Guan, M.; Xu, M.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W. A simple and efficient method to generate dual site-specific conjugation ADCs with cysteine residue and an unnatural amino acid. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32, 1094–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, A.; Ohtake, K.; Tanaka, Y.; Yokoyama, S.; Sakamoto, K.; Shiraishi, Y. An expanded genetic code facilitates antibody chemical conjugation involving the lambda light chain. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021, 546, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesik-Brodacka, M. Progress in biopharmaceutical development. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2018, 65, 306–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Kang, K.G.; Jung, J.Y.; Ha, S.J.; Lim, K.S. Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Development and Advances. Korean Soc. Biotechnol. Bioeng. J. 2021, 36, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CHO Alliance. Prospects and Technological Developments in the 2022 Next-Generation Biopharmaceutical Market; CHO Alliance: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2022; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korea Pharmaceutical and Bio-Pharma Manufacturers Association. Immuno-Oncology Drug Market Trends; Korea Pharmaceutical and Bio-Pharma Manufacturers Association: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021; p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Koreabio. Global Antibody Drug Conjugate Approval and Development Status; KBIOIS: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2023; Volume 60. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, J.T.; Harris, P.W.; Brimble, M.A.; Kavianinia, I. An insight into FDA approved antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 5847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dean, A.Q.; Luo, S.; Twomey, J.D.; Zhang, B. Targeting Cancer with Antibody-Drug Conjugates: Promises and Challenges; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2021; Volume 13, No. 1; p. 1951427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogia, P.; Ashraf, H.; Bhasin, S.; Xu, Y. Antibody–drug conjugates: A review of approved drugs and their clinical level of evidence. Cancers 2023, 15, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mckertish, C.M.; Kayser, V. Advances and limitations of antibody drug conjugates for cancer. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.W.; Khare, S.K. Benefits and challenges of antibody drug conjugates as novel form of chemotherapy. J. Control. Release 2022, 341, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponziani, S.; Di Vittorio, G.; Pitari, G.; Cimini, A.M.; Ardini, M.; Gentile, R.; Iacobelli, S.; Sala, G.; Capone, E.; Flavell, D.J.; et al. Antibody-drug conjugates: The new frontier of chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BeiGene and DualityBio Announce Partnership to Advance Differentiated Antibody Drug Conjugate (ADC) Therapy for Solid Tumors. Available online: https://ir.beigene.com/news/beigene-and-dualitybio-announce-partnership-to-advance-differentiated-antibody-drug-conjugate-adc-therapy-for-solid/8420cc36-bac6-4716-85e6-92db7b665f9b/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- GSK Enters Exclusive License Agreement with Hansoh for HS-20093. Available online: https://www.gsk.com/en-gb/media/press-releases/gsk-enters-exclusive-license-agreement-with-hansoh-for-hs-20093/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Endeavor BioMedicines Enters License Agreement with Hummingbird Bioscience for Worldwide Rights to HMBD-501, a Next Generation HER3-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC). Available online: https://hummingbirdbioscience.com/endeavor-biomedicines-enters-license-agreement-with-hummingbird-bioscience-for-worldwide-rights-to-hmbd-501-a-next-generation-her3-targeted-antibody-drug-conjugate-adc/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Nona Biosciences Enters into a Global License Agreement with Pfizer for HBM9033, an MSLN-Targeted Antibody-Drug Conjugate (ADC). Available online: https://www.nonabio.com/newsd/23-Nona-Biosciences-Enters-into-a-Global-License-Agreement-with-Pfizer-for-HBM9033,-an-MSLN-Targeted-Antibody-Drug-Conjugate-(ADC) (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- SystImmune and Bristol Myers Squibb Announce a Global Strategic Collaboration Agreement for the Development and Commercialization of BL-B01D1. Available online: https://news.bms.com/news/details/2023/SystImmune-and-Bristol-Myers-Squibb-Announce-a-Global-Strategic-Collaboration-Agreement-for-the-Development-and-Commercialization-of-BL-B01D1/default.aspx (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Chia, C.S.B. A patent review on FDA-approved antibody-drug conjugates, their linkers and drug payloads. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, U. Extending the market exclusivity of therapeutic antibodies through dosage patents. MABS 2016, 8, 841–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Storz, U. Antibody-drug conjugates: Intellectual property considerations. MABS 2015, 7, 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senter, P.D.; Doronina, S.O.; Toki, B.E. Drug Conjugates and Their Use for Treating Cancer, an Autoimmune Disease or an Infectious Disease. US Patent 7659241, 9 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, M.; Grauschopf, U.; Mahler, H.-C.; Stauch, O.B. Subcutaneous Anti-her2 Antibody Formulation. EP Patent 2459167B1, 15 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, D.; Atakilit, A. Methods and Compositions for Treating and Preventing Disease Associated with Alpha v Beta 5 Integrin. EP Patent 1734996B1, 22 May 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Koreabio. Current Clinical Status of Antibody Drug Conjugates as of 2022; Koreabio: Seongnam-si, Republic of Korea, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Samantasinghar, A.; Sunildutt, N.P.; Ahmed, F.; Soomro, A.M.; Salih, A.R.C.; Parihar, P.; Memon, F.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kang, I.S.; Choi, K.H. A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of antibody drug conjugate. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 161, 114408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuchikama, K.; Anami, Y.; Ha SY, Y.; Yamazaki, C.M. Exploring the next generation of antibody-drug conjugates. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.; Serwer, L.; DuPage, A.; Elkins, K.; Chauhan, N.; Ravn, M.; Buchanan, F.; Wang, L.; Krimm, K.; Wong, K.; et al. Nonclinical efficacy and safety of CX-2029, an Anti-CD71 probody–drug conjugate. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2022, 21, 1326–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.; Ahnert, J.R.; Lakhani, N.; Sanborn, R.E.; El-Khoueiry, A.; Hafez, N.; Mamdani, H.; Boni, V.; Castro, H.; Hannah, A.L.; et al. P01. 06 CX-2029, A probody drug conjugate targeting CD71 in patients with selected tumor types: PROCLAIM-CX-2029 dose expansion phase. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2021, 16, S238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruani, A. Bispecific and antibody-drug conjugates: A positive synergy. Drug Discov. Today Technol. 2018, 30, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Nam, S.-M.; Moon, A. Antibody–drug conjugates and bispecific antibodies targeting cancers: Applications of click chemistry. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2023, 46, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conilh, L.; Sadilkova, L.; Viricel, W.; Dumontet, C. Payload diversification: A key step in the development of antibody–drug conjugates. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolò, E.; Giugliano, F.; Ascione, L.; Tarantino, P.; Corti, C.; Tolaney, S.M.; Cristofanilli, M.; Curigliano, G. Combining antibody-drug conjugates with immunotherapy in solid tumors: Current landscape and future perspectives. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2022, 106, 102395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.H.; Jeong, M.; In, H.; Kim, J.H.; Lin, C.-W.; Han, K.H. Trends in the development of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer therapy. Antibodies 2023, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Brems, B.M.; Olawode, E.O.; Miller, J.T.; Brooks, T.A.; Tumey, L.N. Design and characterization of immune-stimulating imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline antibody-drug conjugates. Mol. Pharm. 2022, 19, 3228–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, F.; Su, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, T. Activation of STING inhibits cervical cancer tumor growth through enhancing the anti-tumor immune response. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2021, 476, 1015–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duvall, J.R.; Thomas, J.D.; Bukhalid, R.A.; Catcott, K.C.; Bentley, K.W.; Collins, S.D.; Eitas, T.; Jones, B.D.; Kelleher, E.W.; Lancaster, K.; et al. Discovery and optimization of a STING agonist platform for application in antibody drug conjugates. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 10715–10733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klempner, S.J.; Beeram, M.; Sabanathan, D.; Chan, A.; Hamilton, E.; Loi, S.; Oh, D.-Y.; Emens, L.A.; Patnaik, A.; Kim, J.E.; et al. 209P Interim results of a phase I/Ib study of SBT6050 monotherapy and pembrolizumab combination in patients with advanced HER2-expressing or amplified solid tumors. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersana Therapeutics Announces Clinical Hold on XMT-2056 Phase 1 Clinical Trial. Available online: https://ir.mersana.com/news-releases/news-release-details/mersana-therapeutics-announces-clinical-hold-xmt-2056-phase-1 (accessed on 29 January 2024).

- Mersana Therapeutics Announces FDA Has Lifted Clinical Hold on Phase 1 Clinical Trial of XMT-2056. Available online: https://ir.mersana.com/news-releases/news-release-details/mersana-therapeutics-announces-fda-has-lifted-clinical-hold (accessed on 29 January 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).