Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic significantly altered the circulation of respiratory viruses, including influenza. This study aimed to compare the epidemiology and clinical characteristics of paediatric influenza before, during, and after the pandemic. Methods: We retrospectively analysed 553 children aged 0–18 years hospitalised with laboratory-confirmed influenza at a paediatric infectious disease centre in Bydgoszcz, Poland, between September 2017 and August 2025. Patients were stratified into pre-pandemic (A), pandemic (B), and post-pandemic (C) periods. Epidemiological indicators, influenza type, age, sex, and hospital stay duration were assessed using χ2 and non-parametric tests. Results: Hospitalisations varied across seasons, lowest in 2021/22 (n = 18) and highest in 2024/25 (n = 175). Seasonal peaks occurred January–March in groups A and C, whereas group B showed a bimodal pattern in December and March–April. Influenza type A predominated in all periods, though less during the pandemic (56.7% vs. 89.2% pre-pandemic and 73.2% post-pandemic). Median hospital stay decreased from 5 days pre-pandemic to 4 days during and after the pandemic. None of the hospitalised children were vaccinated. Conclusions: The COVID-19 pandemic influenced influenza seasonality, virus type distribution, and hospitalisation patterns in children. Observed shifts highlight the importance of ongoing surveillance and targeted vaccination strategies to mitigate influenza burden in the post-pandemic period.

1. Introduction

Influenza is an acute infectious disease caused by influenza viruses of types A and B, with type A accounting for approximately 80% of reported cases worldwide. In recent years, the predominant circulating subtypes have been A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 [1]. Globally, influenza affects approximately one billion individuals annually, with 3–5 million cases progressing to severe disease. In the Northern Hemisphere, influenza activity typically peaks between late autumn and early spring. Transmission occurs primarily via respiratory droplets and aerosols, as well as through direct contact, with an incubation period ranging from 1 to 4 days. High transmission rates are observed in crowded environments such as childcare facilities, schools, healthcare institutions, and long-term care settings.

The clinical presentation of influenza is characterised by fever, headache, fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia, and upper respiratory tract symptoms, including rhinorrhoea, cough, and sore throat. Gastrointestinal manifestations, such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, and abdominal pain, occur less frequently. Certain paediatric populations are at increased risk of severe disease and complications, including children under 5 years of age—particularly those under 2 years—preterm infants, children with chronic cardiac, pulmonary, renal, hepatic, metabolic or haematological disorders (including obesity), oncological patients, and immunocompromised individuals [1,2]. Identification of these high-risk groups is critical when considering antiviral therapy and post-exposure prophylaxis [3].

Common complications of influenza in children include secondary bacterial infections of the respiratory tract (such as pneumonia, otitis media, laryngitis, and pharyngitis), febrile seizures in younger children, and influenza-associated myositis. Diagnostic confirmation is most frequently achieved using rapid antigen detection tests or molecular assays such as real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Although antigen tests are widely available and offer rapid results, their sensitivity and specificity are lower than those of RT-PCR assays, which are generally reserved for hospital settings due to higher costs and technical requirements [2,4]. The availability of multiplex diagnostic tests detecting influenza A and B, SARS-CoV-2, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) increased substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic, and since January 2023 such testing has been included among guaranteed services in primary healthcare facilities in Poland.

Antiviral treatment for influenza is available and includes oseltamivir, zanamivir, peramivir, and baloxavir marboxil, with maximal effectiveness achieved when therapy is initiated early after symptom onset [2]. In Poland, oseltamivir remains the most commonly used antiviral agent. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends oseltamivir due to its favourable safety profile, extensive clinical experience, and ease of administration [3].

Influenza vaccination is recommended for children aged over 6 months and requires annual administration due to the antigenic variability of circulating strains. Vaccine composition is updated annually based on World Health Organization surveillance data [1]. Antiviral treatment is not a substitute for vaccination, and preventive immunisation remains the cornerstone of influenza control [3]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several international organisations emphasised the importance of maintaining influenza vaccination programmes to reduce the burden on healthcare systems already strained by SARS-CoV-2 infections [5].

In December 2019, cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology were reported in Wuhan, China, and on 7 January 2020 a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, was identified as the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [6]. The rapid global spread of SARS-CoV-2 led to unprecedented public health measures, including lockdowns, school closures, physical distancing, mandatory face coverings, and reorganisation of healthcare services. In Poland, a state of epidemic emergency was declared in March 2020 and remained in force until May 2022 [7,8,9]. On 5 May 2023, the World Health Organization declared that COVID-19 no longer constituted a Public Health Emergency of International Concern [10].

These profound societal and healthcare-related disruptions significantly affected the transmission dynamics of respiratory pathogens. Accumulating evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic not only reduced the circulation of influenza viruses but also altered their seasonal patterns and epidemiological characteristics. However, data describing how these changes translated into paediatric hospitalisation patterns before, during, and after the pandemic remain limited.

Therefore, this study was designed to test the hypothesis that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with significant modifications in paediatric influenza epidemiology, including changes in seasonality, viral type distribution, and hospitalisation burden. The objective was to compare influenza-related hospitalisations with respect to patient age and sex, influenza virus type, length of hospital stays, and seasonal incidence across pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods among children hospitalised in a tertiary paediatric infectious disease centre between 2017 and 2025.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection and Study Population

Data were collected retrospectively from 1 September 2017 to 31 August 2025 at a single tertiary paediatric infectious disease centre in Bydgoszcz, Poland. The study population consisted of 553 children aged 0–18 years hospitalised with laboratory-confirmed influenza, either as a primary or secondary diagnosis, according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10 codes J10.0, J10.1, and J10.8). Diagnosis was established through positive antigen or molecular (RT-PCR) testing for influenza A or B virus.

Each infectious season was defined as spanning from 1 September of a given year to 31 August of the following year. To examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, patients were stratified into three epidemiological groups:

- −

- Pre-pandemic—Group A: September 2017–April 2020.

- −

- Pandemic—Group B: September 2021–August 2023.

- −

- Post-pandemic—Group C: September 2023–August 2025.

Data from April 2020 to September 2021 were excluded because the hospital functioned primarily as a COVID-19 treatment centre and admitted no patients with other conditions. The period from May to August 2023, when no children were hospitalised for influenza, was pragmatically included in the pandemic-related group (Group B) to maintain continuity across infectious seasons and avoid artificial fragmentation of the pandemic period. This approach allowed for consistent seasonal comparisons and statistical analysis.

The dataset included variables such as patient age, sex, influenza virus type (A or B), and length of hospital stay. Epidemiological data from the District Sanitary and Epidemiological Station in Bydgoszcz were also considered to complement hospital records, as reporting of all confirmed influenza cases is mandatory in Poland.

2.2. Ethics

No experimental interventions were administered, and all patients received standard clinical care according to current guidelines [11]. Personal data were anonymised, and informed consent was not required under applicable regulations.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables, including age categories, sex, and influenza virus type, were summarised using counts and percentages. Continuous variables, such as length of hospital stay, were reported as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) due to non-normal distribution, as assessed by the Shapiro–Wilk test.

Comparisons between groups (A vs. B, A vs. C, B vs. C) were performed using Pearson’s χ2 test for categorical variables and the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. The Bonferroni correction was applied to account for multiple comparisons.

These pairwise comparisons were pre-specified as the primary analyses to evaluate differences in influenza epidemiology across the three defined periods. Secondary/exploratory analyses included descriptive assessment of monthly and seasonal trends, age group distribution, and potential interactions between influenza type and length of hospitalisation. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value < 0.05. Analyses were performed using Statistica v.13 (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

3. Results

During the study period, 553 children with laboratory-confirmed influenza were hospitalised at the Department of Paediatrics, Infectious Diseases and Hepatology, with an average of 79 admissions per year. The lowest number of hospitalisations occurred in the 2021/22 season, while the highest was recorded in 2024/25 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Monthly distribution of paediatric hospitalisations for influenza types A and B, stratified by infectious seasons.

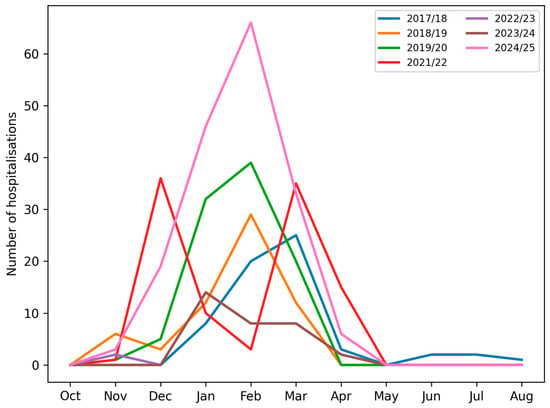

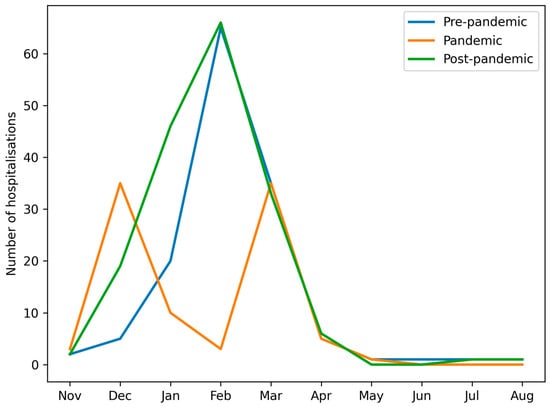

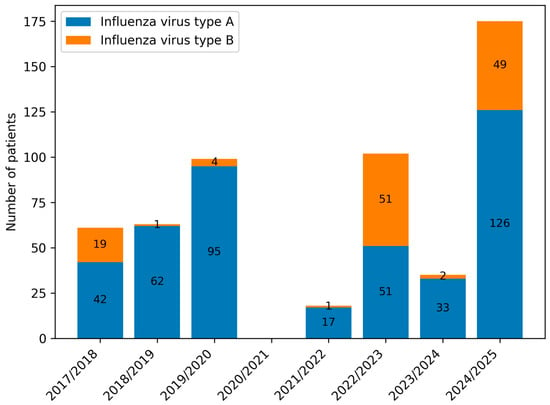

In all seasons, the lowest number of admissions was observed between June and November. Groups A (pre-pandemic) and C (post-pandemic) demonstrated typical seasonal peaks between January and March. In contrast, Group B (pandemic) displayed a bimodal pattern, with peaks in December and March, and reduced admissions in January and February (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Number of paediatric patients hospitalised with influenza virus type A or type B in consecutive months across subsequent infectious seasons.

Figure 2.

Number of paediatric patients hospitalised with influenza virus type A or type B in consecutive months in groups A, B and C.

The mean number of hospitalised patients per season was 74.33 in group A, 60 in group B and 105 in group C. The age of the patients (calculated on the first day of hospitalisation) ranged from 14 days of life to 18 years. No statistically significant differences were observed in age distribution among groups A, B, and C (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of paediatric patients infected with the influenza virus and hospitalised in groups A, B and C.

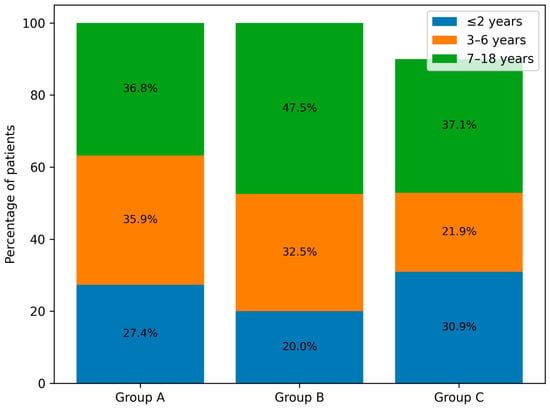

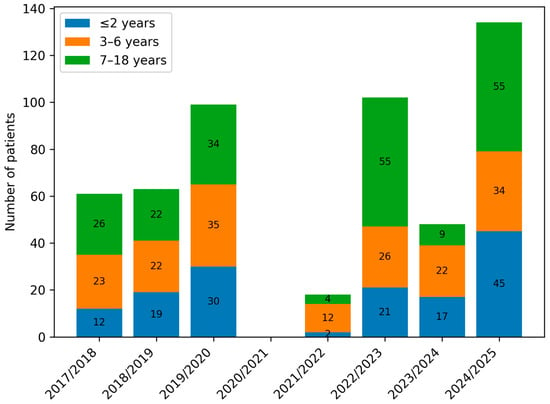

Figure 3 presents the percentage distribution of the defined age groups of patients across the analysed periods (A, B and C), while Figure 4. shows the number of children in the respective age groups in the analysed infectious seasons.

Figure 3.

Age distribution of paediatric patients infected with the influenza virus and hospitalised in groups A, B and C.

Figure 4.

Number of paediatric patients hospitalised with influenza by age group (≤2 years, 3–6 years, and 7–18 years) across consecutive infectious seasons (2017/2018–2024/2025).

Sex distribution differed across periods, with a predominance of boys in the pre-pandemic group and more balanced proportions in Groups B and C. The difference between Groups A and C reached statistical significance (p = 0.03) (Table 2).

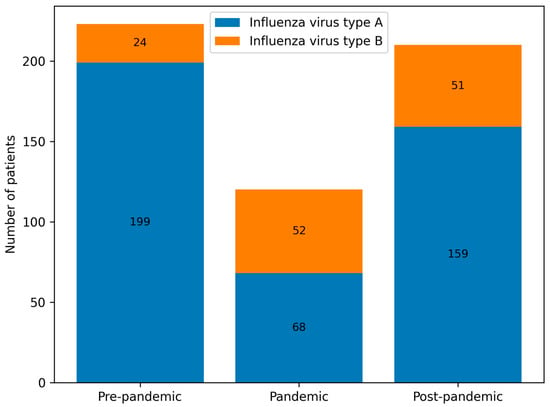

Influenza virus type A predominated across all periods, although its proportion decreased markedly during the pandemic (Group B) compared with the pre- and post-pandemic periods (Groups A and C). Statistically significant differences were observed in all pairwise comparisons (A vs. B, A vs. C, B vs. C; p < 0.001) (Table 2, Figure 5 and Figure 6). The 2022/23 season was notable for an equal distribution of influenza types A and B.

Figure 5.

Number of paediatric patients infected with influenza virus types A and B in consecutive infectious seasons.

Figure 6.

Number of paediatric patients infected with influenza virus types A and B in groups A, B and C.

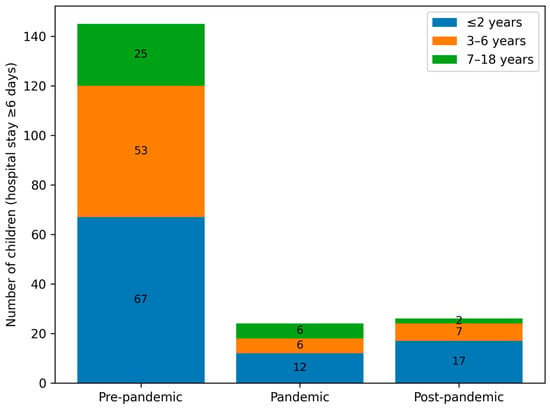

The median length of hospital stay decreased from 5 days pre-pandemic to 4 days during and after the pandemic (Groups B and C), with a statistically significant difference between Groups A and C (p = 0.03). Longer hospitalisations (≥6 days) were more common in the pre-pandemic period, particularly among children aged ≤2 years, whereas shorter stays (3–4 days) predominated in the post-pandemic period. Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of prolonged hospitalisations (≥6 days) across age groups in the pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic periods.

Figure 7.

Number of children with prolonged hospitalisation (≥6 days) stratified by epidemiological period (pre-pandemic, pandemic, and post-pandemic) and age group (≤2 years, 3–6 years, and 7–18 years).

Epidemiological data from the District Sanitary and Epidemiological Station confirmed a marked increase in influenza testing after January 2023, following the introduction of free antigen testing in outpatient clinics. This increase likely contributed to higher numbers of confirmed and reported cases, particularly in 2023–2025 (Table 3). It should be noted that some children admitted to our hospital were from other districts; in these cases, reporting obligations apply to the patient’s district of residence.

Table 3.

Number of positive antigen tests, positive RT-PCR tests, number of hospitalised children and reported influenza cases in the Bydgoszcz district.

Medical history review revealed that none of the hospitalised children had received influenza vaccination during the respective season. This observation reflects persistently low vaccination coverage in the paediatric population rather than vaccine failure.

Overall, the data indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with altered influenza seasonality, a shift in viral type distribution, shorter hospitalisations, and minor changes in sex distribution among hospitalised children. The temporal patterns observed highlight the impact of pandemic-related public health measures and altered healthcare-seeking behaviour on influenza epidemiology.

4. Discussion

Our study is one of the few that compares the epidemiology of influenza in paediatric patients before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. For influenza incidence in the Polish population, the National Institute of Public Health–National Institute of Hygiene–National Research Institute provides data on reported and suspected cases across successive infectious seasons. In the last full season before the COVID-19 pandemic (1 September 2018 to 31 August 2019), 3,954,235 influenza cases were registered in Poland. In the following seasons, the numbers were: 2019/20–3,769,480 cases; 2020/21–1,616,258 cases; 2021/22–2,934,496 cases; and in the 2022/23 season, 5,515,237 cases were reported [12].

Considering the number of children hospitalised with influenza in each infectious season in our analysis, a clear decrease in hospitalisations was observed in the 2021/22 season. It is important to note that during this period, our hospital was designated primarily for the treatment of COVID-19 patients, and routine admissions for other infectious diseases—including influenza—were largely suspended. Therefore, the observed decrease in hospitalisations in our cohort reflects both a true reduction in influenza circulation and the temporary reorganisation of healthcare services rather than a complete absence of influenza cases in the community. In contrast, the 2022/23 season—when most COVID-19-related restrictions in Poland had been lifted—showed an incidence comparable to pre-pandemic levels. Excluding the 2020/21 season, which was omitted due to the specific function of our ward at that time, the national population-level data align with our findings: the fewest children were hospitalised in 2021/22, followed by a marked increase in admissions in the subsequent season. The most recent analysed season, 2024/25, is exceptional—the number of hospitalisations (175) is more than double the average number recorded in pre-pandemic seasons (74 children per season).

When considering influenza type distribution across groups A, B, and C, we observed a marked shift during the pandemic. In groups B and C, influenza type B accounted for a higher proportion of cases compared with pre-pandemic seasons. In particular, the 2022/23 season showed equal proportions of influenza types A and B (50% each), and in 2024/25 influenza type B represented 28% of cases. Prior to the pandemic, influenza type B accounted for less than 6% of cases in most seasons, except for 2017/18 (31%) [13,14]. These findings are consistent with other reports, such as Kondratiuk et al., who identified influenza type B in approximately 1% of Polish children in the 2018/19 season [13]. The shifting dominance of virus types underscores the impact of pandemic-related changes on viral circulation dynamics, including altered exposure patterns and potential viral interference.

In groups A and C, the peak incidence consistently occurred between January and March. However, in group B, we observed a shift in influenza seasonality—the peak incidence occurred earlier (December) and later (March–April) than in groups A and C. This temporal change is likely influenced by both behavioral and healthcare-related factors, including school closures, stay-at-home orders, mask use, reduced social contacts, and changes in healthcare provision, as well as biological or ecological mechanisms, such as viral interference between SARS-CoV-2 and influenza viruses and altered population immunity due to reduced exposure [15,16,17,18]. The pandemic period can thus be conceptualised as a phase of profound systemic disruption, affecting healthcare organisation, public health priorities, and population-level exposure patterns, consistent with observations from Italy and other European countries, where non-pharmaceutical interventions and healthcare system stress reshaped infectious disease circulation at a population level [19]. Figure 2 and Table 1 illustrate these seasonal shifts in hospitalisation numbers and monthly distribution of influenza types.

Analysis of the age of hospitalised patients revealed a decrease in admissions among young children up to 2 years of age and an increase among children over 7 years in group B. In the infectious seasons within group C, children aged 3–6 years represented, for the first time, the smallest proportion of hospitalised patients. Despite these shifts, no statistically significant differences were found between the numbers of children in individual age categories across groups A, B, and C (Table 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4).

The sex distribution of hospitalised children showed the greatest disparity in group A, with boys being hospitalised more frequently than girls (21.98 percentage points). In groups B and C, these differences were substantially smaller: 3.34 percentage points in favour of boys in group B, and 1.9 percentage points in favour of girls in group C. These differences were statistically significant when comparing groups A and C (p = 0.03) (Table 2).

The median length of hospital stay was longest in group A (5 days, IQR 3–6), compared with 4 days (IQR 3–5) in groups B and C. Longer stays (≥6 days) affected 32.74% of children in group A, 20.83% in group B, and 18.1% in group C (Figure 7). The shorter hospitalisations observed during and after the pandemic may reflect changes in clinical management, healthcare system pressures, and altered patterns of disease severity.

A particularly notable observation was that none of the hospitalised children had been vaccinated against influenza during the seasons in which they were admitted. This finding should be interpreted with caution, as it primarily reflects persistently low vaccination coverage in the paediatric population in Poland, rather than vaccine failure [19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. According to data from the National Institute of Public Health regarding influenza vaccination, in the years 2017–2019, vaccination coverage in the age groups 0–4 years and 5–14 years did not exceed 1%. A slight increase in the number of vaccinated children has been observed since 2020:

- −

- 2020: approximately 1.2% in children aged 0–4 years and approximately 2.2% in children aged 5–14 years.

- −

- 2021: approximately 1.3% in children aged 0–4 years and approximately 1.3% in children aged 5–14 years.

- −

- 2022: approximately 1.5% in children aged 0–4 years and approximately 1.2% in children aged 5–14 years.

- −

- 2023: approximately 3.2% in children aged 0–4 years and approximately 1.9% in children aged 5–14 years [20].

Shmueli et al. reported that disruptions to routine childhood immunisation programmes during the COVID-19 pandemic, including reduced access to primary care visits, led to decreased vaccination rates and increased vaccine hesitancy [21]. Influenza vaccination is recommended but not mandatory in Poland, and coverage remains suboptimal despite free vaccination for children aged 6 months to 18 years since September 2021. Internationally, influenza vaccination rates are higher; for example, in the United States, coverage among children aged 6 months to 18 years reached 63.7% in 2019/20 and remained above 57% in subsequent seasons, although a slight downward trend has been observed [22]. Evidence from meta-analyses indicates that influenza vaccination provides substantial protection against hospitalisation, with Boddington et al. reporting 53.2% protection (95% CI: 47.1–58.6) and Kalligeros et al. reporting 57.48% protection (95% CI: 49.46–65.49) [23,24]. The importance of vaccination is further emphasised by Ozsurekci et al., who highlighted that children under 2 years of age constitute a high-risk group for severe influenza, comparable to those with congenital heart defects or oncological conditions [25]. Collectively, these findings underscore the critical need to improve influenza vaccination coverage to reduce hospitalisations and severe disease in children.

Numerous scientific societies and institutions issue recommendations and educational materials regarding influenza vaccination: internationally, WHO, ECDC (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control), ACIP (Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, USA) and AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics, USA); and in Poland, the National Institute of Public Health–National Research Institute (NIZP-PZH–PIB), the Polish Paediatric Society and the Polish Vaccinology Society. Across all recommendations, particular emphasis is always placed on the paediatric population [26,27].

Our results highlight the complex interplay between public health interventions, behavioural changes, and biological mechanisms during the COVID-19 pandemic, which collectively influenced the epidemiology of influenza in children. The observed shifts in seasonality, virus type prevalence, age distribution, and hospitalisation patterns illustrate that the pandemic’s impact extends beyond SARS-CoV-2, affecting the circulation of other respiratory viruses. These findings support ongoing surveillance and targeted vaccination strategies to mitigate the burden of influenza in the post-pandemic period.

Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the monocentric design may limit the generalisability of the results. Second, potential changes in hospital admission criteria over time and the possibility of underdiagnosis of influenza in pre-pandemic seasons may have affected observed trends. Third, data on viral co-infections were not consistently available. Finally, the inclusion of the May–August 2023 period within the pandemic group, while pragmatic to preserve seasonal continuity and avoid artificial fragmentation, may appear arbitrary. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable insight into temporal trends and factors influencing paediatric influenza during a period of profound epidemiological change.

5. Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic had a multifaceted impact on the epidemiology of infectious diseases in the paediatric population. Changes in social behaviour, the introduction of mobility restrictions, isolation from educational institutions, and reduced access to healthcare services—including limited preventive visits and disruptions to routine vaccination schedules—affected both the incidence and clinical course of influenza among children. These effects were observed in multiple dimensions, including altered seasonal peaks, shifts in virus type distribution, variations in age and sex patterns among hospitalised children, and changes in the length of hospitalisation.

Based on the data analysed in our study, the observed differences in influenza epidemiology in hospitalised paediatric patients during the COVID-19 pandemic can be linked to a combination of behavioral, healthcare-related, and biological factors. Prior to the pandemic, the predominance of influenza type A was associated with longer hospital stays and was more frequently observed in male patients. During the pandemic, a shift in seasonal patterns was noted, with the typical pre- and post-pandemic peaks in January and February absent, likely reflecting the implementation of stricter sanitary measures, school closures, reduced social contacts, and changes in healthcare provision. In addition, viral interference and reduced population immunity may have contributed to these epidemiological changes.

A notable observation was that none of the children hospitalised in our department during the analysed years had been vaccinated against influenza. This finding highlights persistently low vaccination coverage in the paediatric population in Poland and underscores the importance of promoting influenza vaccination as an effective preventive measure to reduce hospitalisations and severe disease in children.

Further research, including multifactorial analyses of variables influencing the course of influenza and the dynamics of its seasonality, is essential—particularly in the context of the changes triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and their potential long-term consequences. Continuous monitoring of influenza epidemiology, vaccination coverage, and clinical outcomes in children is necessary to inform public health strategies and to prepare for future seasonal and pandemic influenza threats.

In conclusion, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a phase of profound systemic disruption with long-lasting effects on paediatric infectious disease patterns. Our findings emphasize the need for integrated public health interventions, ongoing surveillance, and improved vaccination coverage to mitigate the burden of influenza in children in the post-pandemic period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and Z.W.; methodology, M.P. and Z.W.; software and formal analyses K.D.; validation, M.P. and M.S.-P.; investigation, Z.W., J.M. and J.F.; resources, Z.W., J.M. and J.F.; data curation, K.D. and Z.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.W.; writing—review and editing, M.P. and M.S.-P.; visualization, Z.W. and K.D.; supervision, M.P.; project administration, M.P. and Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Bioethics Committee (protocol code KB 117/2025, 12 February 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the scope of the analyzed data does not allow for human identification.

Data Availability Statement

The data obtained for the purposes of the above publication are available from the first author after e-mail contact.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| IQR | Interquartile range |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ECDC | European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control |

| ACIP | Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices |

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| NIZP-PZH–PIB | National Institute of Public Health—National Research Institute |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| RSV | Respiratory Syncytial Virus |

| USA | United States of America |

| UNICEF | United Nations Children’s Fund |

References

- Influenza (Seasional). World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/influenza-(seasonal) (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Wolf, R.M.; Antoon, J.W. Influenza in Children and Adolescents: Epidemiology, Management, and Prevention. Pediatr. Rev. 2023, 44, 605–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Recommendations for Prevention and Control of Influenza in Children, 2025–2026: Policy Statement. Pediatrics 2025, 156, e2025073620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitt, E.; Drew, R.J.; Cunney, R.; Beekmann, S.E.; Polgreen, P.; Butler, K.; Zaoutis, T.; Coffin, S.E. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Influenza in the Era of Rapid Diagnostics. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2020, 9, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.-L.; Namazova-Baranova, L.; Yang, Y.-H.; Wong, G.W.K.; Rosenwasser, L.J.; Rodewald, L.E.; Goh, A.E.N.; Kerem, E.; O’Callaghan, C.; Kinane, T.B.; et al. Global Pediatric Pulmonology Alliance (GPPA) Expert Panel on Infectious Diseases & COVID-19. Global Pediatric Pulmonology Alliance recommendation to strengthen prevention of pediatric seasonal influenza under COVID-19 pandemic. World J. Pediatr. 2020, 16, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Zhao, X.; Li, J.; Niu, P.; Yang, B.; Wu, H.; Wang, W.; Song, H.; Huang, B.; Zhu, N.; et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: Implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 2020, 395, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suder, M.; Wójtowicz, T.; Kusa, R.; Gurgul, H. Challenges for ATM management in times of market variability caused by the COVID-19 pandemic crisi. Central Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2023, 31, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coronavirus: Information and Recommendations, Official Portal of the Republic of Poland. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/wiadomosci (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Mirska, B.; Zenczak, M.; Nowis, K.; Stolarek, I.; Podkowiński, J.; Rakoczy, M.; Marcinkowska-Swojak, M.; Koralewska, N.; Zmora, P.; Onyekaa, E.L.; et al. The landscape of the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland emerging from epidemiological and genomic data. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Statement on the Fifteenth Meeting of the IHR (2005) Emergency Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-05-2023-statement-on-the-fifteenth-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-%282005%29-emergency-committee-regarding-the-coronavirus-disease-%28covid-19%29-pandemic?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Sybilski, A.J.; Mastalerz-Migas, A.; Jackowska, T.; Woroń, J.; Kuchar, E.; Doniec, Z. Rekomendacje postępowania w grypie u dzieci—KOMPAS GRYPA 23/24. Aktualizacja na sezon 2023/2024. Paediatr. Fam. Med. Pediatr. I Med. Rodz. 2023, 19, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influenza Cases and Suspected Cases in Poland. National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene, Department of Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases and Surveillance, Epidemiological Situation Monitoring and Analysis Unit. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/grypa/index.htm (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Kondratiuk, K.; Hallmann, E.; Łuniewska, K.; Szymański, K.; Brydak, L. Epidemiology of Influenza Viruses and Viruses Causing Influenza-Like Illness in Children Under 14 Years Old in the 2018-2019 Epidemic Season in Poland. Med. Sci. Monit. 2021, 27, e929303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuniewska, K.; Szymański, K.; Hallmann-Szelińska, E.; Kowalczyk, D.; Sałamatin, R.; Masny, A.; Brydak, L.B. Infections Caused by Influenza Viruses Among Children in Poland During the 2017/18 Epidemic Season. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1211, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Facciolà, A.; Laganà, A.; Genovese, G.; Romeo, B.; Sidoti, S.; D’Andrea, G.; Raco, C.; Visalli, G.; DI Pietro, A. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the infectious disease epidemiology. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2023, 64, E274–E282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaatz, M.; Springer, S.; Zieger, M. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic measures on incidence and representation of other infec-tious diseases in Germany: A lesson to be learnt. J. Public Health 2022, 31, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. Influenza’s Unprecedented Low Profile During COVID-19 Pandemic Leaves Experts Wondering What This Flu Season Has in Store. JAMA 2021, 326, 899–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoy, G.; Maier, H.E.; Kuan, G.; Sánchez, N.; López, R.; Meyers, A.; Plazaola, M.; Ojeda, S.; Balmaseda, A.; Gordon, A. Increased influenza severity in children in the wake of SARS-CoV-2. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2023, 17, e13178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’AMbrosio, F.; Lanza, T.E.; Messina, R.; Villani, L.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Ricciardi, W.; Rosano, A.; Cadeddu, C. Influenza vaccination coverage in pediatric population in Italy: An analysis of recent trends. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2022, 48, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protective vaccinations in Poland. National Institute of Public Health—National Institute of Hygiene, Department of Epidemiology of Infectious Diseases and Surveillance, Epidemiological Situation Monitoring and Analysis Unit. Available online: https://wwwold.pzh.gov.pl/oldpage/epimeld/index_p.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Shmueli, M.; Lendner, I.; Ben-Shimol, S. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pediatric infectious disease landscape. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2024, 183, 1001–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC, FluVaxViev. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/fluvaxview/coverage-by-season/index.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Boddington, N.L.; Pearson, I.; Whitaker, H.; Mangtani, P.; Pebody, R.G. Effectiveness of Influenza Vaccination in Preventing Hospi-talization Due to Influenza in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1722–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalligeros, M.; Shehadeh, F.; Mylona, E.K.; Dapaah-Afriyie, C.; van Aalst, R.; Chit, A.; Mylonakis, E. Influenza vaccine effectiveness against influenza-associated hospitalization in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2020, 38, 2893–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozsurekci, Y.; Aykac, K.; Bal, F.; Bayhan, C.; Basaranoglu, S.T.; Alp, A.; Cengiz, A.B.; Kara, A.; Ceyhan, M. Outcome predictors of influenza for hospitalization and mortality in children. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 6148–6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Official Journal of the Polish Minister of Health, Announcement of the Chief Sanitary Inspector of 31 October 2025, Vaccination Program. Available online: https://dziennikmz.mz.gov.pl/DUM_MZ/2025/85/akt.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Portal Under the Patronage of the Chief Sanitary Inspector in Poland. Educational Materials. Available online: https://szczepienia.pzh.gov.pl/szczepionki/grypa/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 30 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.