Abstract

Emerging and re-emerging viruses continue to pose major threats to public health. Their ability to adapt, cross species barriers, and spread rapidly can trigger severe outbreaks or even pandemics. Strengthening preparedness with comprehensive and efficient strategies is therefore essential. Here, we explore the key components of viral outbreak preparedness, including surveillance systems, diagnostic capacity, prevention and control measures, non-pharmaceutical interventions, antiviral therapeutics, and research and development. We emphasize the increasing importance of genomic surveillance, wastewater-based surveillance, real-time data sharing, and the One Health approach to better anticipate zoonotic spillovers. Current challenges and future directions are also discussed. Effective preparedness requires transparent risk communication and equitable access to diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics. The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted both the promise of next-generation vaccine platforms and the necessity of maintaining diagnostic capacity, as early testing delays hindered containment efforts. Countries adopted various non-pharmaceutical interventions: risk communication and social distancing proved to be the most effective, while combined workplace infection-prevention measures outperformed single strategies. These experiences highlight the importance of early detection, rapid response, and multisectoral collaboration in mitigating the impact of viral outbreaks. By applying best practices and lessons learned from recent events, global health systems can strengthen resilience and improve readiness for future viral threats.

1. Introduction

The emergence of viral pathogens has led to several outbreaks worldwide during the last 20 years. Significant examples include the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) outbreak in China during 2002–2003 [1], the pandemic influenza A/H1N1 in 2009 [2], the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus that emerged in 2012 [3], the West Africa Ebola virus epidemic from 2013–2016 [4] and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) from 2018–2020, the Zika virus epidemic from 2016 to 2017 [5], the Mpox outbreak in 2022 and 2024 and the COVID-19 pandemic that originated in China in late 2019 [6]. Collectively, these outbreaks have provided recurring yet often underutilized lessons for pandemic preparedness. Table 1 summarizes selected major viral epidemics since 2009, their geographic contexts, and key preparedness lessons that inform the priorities discussed in this review.

Table 1.

Key viral outbreaks and lessons learned for public health preparedness, 2009–2025.

Zoonotic spillover accounts for ~70–80% of newly emerging infectious diseases. Transmission pathways of zoonotic viruses are diverse, including foodborne or waterborne routes, vectors such as insects or other animals, and through contact, either directly with infected animals or indirectly with contaminated surfaces (fomites). The emergence and re-emergence of these threats reflect a complex interplay of viral, human, and environmental factors.

Viral factors, notably high mutation rates, recombination, and reassortment, facilitate rapid adaptation and success of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases. For instance, RNA viruses lack proofreading activity in their RNA-dependent RNA polymerases (RdRp), resulting in a significantly elevated mutational rate of 103–105 substitutions per site per replication cycle, which promotes rapid genetic diversity and adaptation to new hosts [23]. In influenza virus, accumulating point mutations, in particular within the major surface protein, hemagglutinin (HA), constantly generate a multitude of genetic and antigenic variants [24]. Recombination and reassortment further enhance this inherent property, facilitating genomic modification and the emergence of new variants. Examples include poliovirus (PV) recombination that eliminates deleterious mutations, SARS-CoV-2 spike protein modifications through recombination, and influenza reassortment events (1957 Asian H2N2, 1968 Hong Kong H3N2, 2009 swine H1N1) that produced pandemic strains with significant global health consequences [25]. Collectively, these mechanisms result in viral quasispecies, which are diverse, dynamic groups that enhance virus adaptability under immune and environmental pressures [26].

Human factors, including globalization and urbanization, have accelerated viral spread through increased human mobility and density [27]. Air travel enables the rapid dissemination of viral pathogens across continents within 48 h, as demonstrated by the 2022 and 2024 worldwide Mpox outbreaks linked to international travel [28]. The expansion of urban areas into wildlife habitats results in increased human–animal contact. In more densely populated areas with reduced biodiversity, pathogen amplification increases as competent reservoir species become more abundant, as observed in the urban resurgence of dengue [27,29]. One behavioral factor that has hindered progress against vaccine-preventable diseases is vaccine hesitancy; in 2023, measles infections worldwide increased to 10.3 million, while vaccination coverage fell to 74% for second doses [30]. Conflict and humanitarian crises, such as those in Gaza, contributed to the PV resurgence in 2024, following a decline in vaccination rates from 99% in 2022 to 89% in 2023, which was attributed to a war-induced collapse of healthcare systems [31,32].

Environmental and ecological dynamics factors, such as deforestation and climate change, alter zoonotic risk landscapes. Habitat fragmentation forces wildlife into closer contact with the human population, leading to spillover events, as evidenced by outbreaks of Nipah virus linked to habitat destruction and bat displacement. Climate change also amplifies these risks further by altering the geographic distribution and abundance of vectors, such as mosquitoes and ticks. Given the rising temperatures, the expansion of Aedes aegypti habitats has driven dengue transmission to a record 13 million cases in 2024, a 361% increase over the 5-year cases, reflecting a long-term growth rate of 13% annually since 2000 [33].

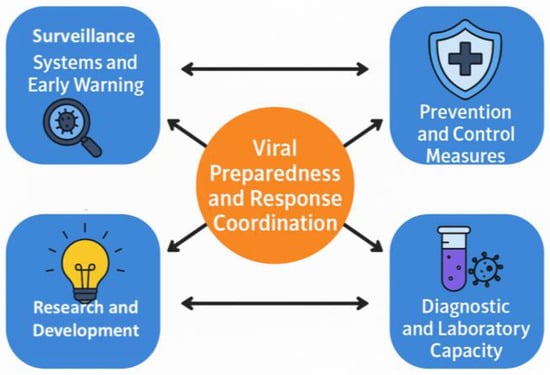

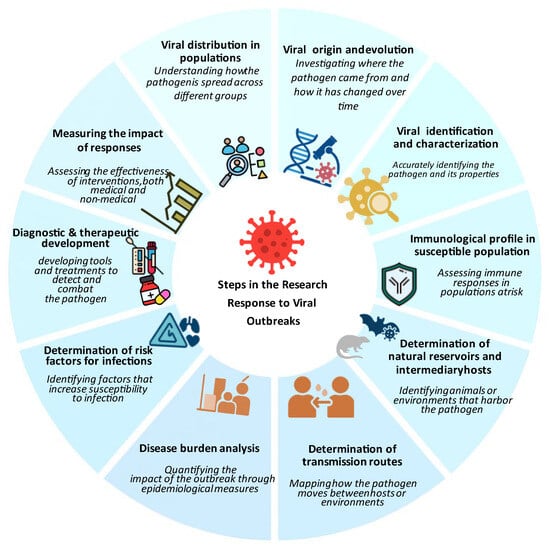

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) introduced the term “Disease X” to highlight the need for preparedness against unknown pathogens [34]. This concept was applied during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a novel betacoronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) showed that, despite advances in genomic surveillance, zoonotic spillover events could be unpredictable. Pathogen X has the potential to emerge, causing a future disease capable of causing epidemics or pandemics; therefore, there is a need to study the preparedness to develop a successful response and solutions. Moreover, in July 2024, the WHO updated the list of priority pathogens, focusing on entire families of bacteria and viruses rather than just specific entities to recognize that low-risk groups could evolve into high-risk ones. In this context, Pathogen X/Disease X refers to potential hazards that have not yet been identified. The update further incorporates “Prototype Pathogens,” which are viruses from high-risk families that will accelerate the development of vaccinations and diagnostics. Consequently, this review discusses in detail the key components of the outbreak preparedness plan, as illustrated in Figure 1 [35]. These integrated elements strengthen the ability to identify and respond to potential outbreaks before they escalate into widespread health crises.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework for viral outbreak preparedness and response. The central hub represents coordination across four interdependent pillars: (i) surveillance and early-warning systems, including event-based, genomic, and environmental monitoring; (ii) diagnostic and laboratory capacity for rapid detection and characterization of viral threats; (iii) prevention and control measures such as vaccination, antivirals, and non-pharmaceutical interventions; and (iv) research and development supporting innovation in vaccines, therapeutics, and risk-assessment tools. This framework illustrates how integrated functions enable early detection, timely response, and overall system resilience.

Command and coordination optimize resource allocation and response organization. Robust and effective surveillance and early warning systems facilitate the rapid identification of emerging pathogens. Laboratory services are important for diagnostic confirmation and epidemiological studies. Prevention and control measures, including vaccination programs and public health communication, help contain outbreaks and protect vulnerable populations. Research and innovation continually facilitate the development of new treatments, diagnostic tools, and preventive measures to maintain readiness against emerging pathogens. Investment in these preparedness measures enhances public health protection and prevents future outbreaks from causing widespread devastation.

This review highlights current evidence and best practices for viral outbreak preparedness, with three main objectives: (1) to describe the key components of effective preparedness systems, including surveillance, diagnostics, prevention and control measures, research and development and response coordination; (2) to reflect on lessons learned from recent outbreaks, particularly COVID-19, to strengthen preparedness strategies; and (3) to identify gaps and future priorities in global health security. It targets public health officials, healthcare administrators, researchers, educators, policymakers, international organizations, and frontline healthcare workers involved in outbreak response. The review provides evidence-based insights to guide decision-making and support resilient health systems capable of responding effectively to future viral threats.

Several strategic frameworks for emergency preparedness have been published, including the WHO Strategic Framework for Emergency Preparedness [36], national guidance such as the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency’s incident management systems (U.S. FEMA, 2022), and international pandemic frameworks such as the WHO Pandemic Agreement [37]. These frameworks describe preparedness as a continuous cycle of anticipating hazards, mitigating impacts, responding to events, and recovering from consequences. This review does not aim to reproduce a comprehensive preparedness framework. Instead, it provides a standalone, evidence-based synthesis of viral outbreak preparedness, drawing on lessons from COVID-19, Mpox, and other viral threats. By focusing on key capacities—surveillance (including genomic and wastewater monitoring), diagnostics, vaccination and therapeutics, infection prevention and control, and research—this review provides an updated virology-specific perspective to inform national and global preparedness planning.

2. Methods

This narrative review synthesizes current evidence and best practices for viral outbreak preparedness. While it does not follow systematic frameworks such as PRISMA, a structured search was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and key public health sources including WHO and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) using keywords such as “viral preparedness,” “emerging viruses,” “genomic surveillance,” “wastewater surveillance,” “diagnostics,” “pandemic response”, “therapeutics” and “One Health.” The review prioritizes literature from 2015–2025 to reflect contemporary advances in viral preparedness, while older references are included selectively to provide historical context and a foundational understanding. Sources were evaluated for relevance, quality, and contribution to the review themes, and synthesized qualitatively to present current trends, challenges, and future directions.

3. Surveillance Systems and Early Warning

Effective viral surveillance is the cornerstone of pandemic preparedness, enabling early detection and tracking of novel threats before widespread transmission occurs. Systematic monitoring of high-risk regions and populations facilitates timely identification of emergent pathogens and zoonotic infections, supporting rapid risk assessment and preventive planning.

Beyond early warning, viral surveillance also plays a critical role in confirming and characterizing outbreaks by identifying clusters of illness or unusual disease patterns. Given the various modes of virus transmission and some viruses being zoonotic, an integrated surveillance system (One Health) is necessary, which includes the data from human, animal, and environmental sources to monitor and mitigate health risks at the interface of the human–animal environment. This approach helps in understanding disease transmission dynamics and supports coordinated response efforts.

International non-governmental organizations have developed several frameworks to address zoonotic diseases within the One Health context [38,39,40,41]. While the recent pandemics highlighted the broader applications of One Health, environmental monitoring of vector-borne viruses exemplifies its role in improving public health [42]. For example, in 2025, chikungunya cases reached approximately 240,000 worldwide, transforming from a regional concern to a global public health emergency.

While climate change and urbanization have expanded the habitat of Aedes aegypti and increased transmission potential, global spread has been facilitated by human mobility and international travel, leading to the emergence of major transmission hubs across multiple continents [43]. The Indian Ocean islands, France, and Italy have been particularly affected [44]. China has reported over 10,000 cases since July 2025, marking its largest recorded chikungunya outbreak, compared with only 519 cases between 2010 and 2019 [45].

3.1. Traditional Surveillance

3.1.1. Passive Surveillance: Routine Monitoring and Systemic Gaps

Passive surveillance remains the cornerstone of routine public health monitoring. It depends on healthcare providers to voluntarily report notifiable diseases without systematic outreach [46]. Although this approach is cost-effective and scalable, it encounters considerable limitations due to systematic underreporting, which arises from variations in healthcare access, diagnostic practices, and healthcare-seeking behavior. The limitations of passive surveillance systems are well-documented [47].

Despite these limitations, passive systems are essential for establishing baseline epidemiological trends. In the United States, influenza-like illness (ILI) is routinely monitored across more than 120,000 healthcare providers before the pandemic, providing critical early warning data [48]. Additionally, the National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) in the United States demonstrates effective passive surveillance by collecting laboratory data on viruses such as the influenza virus and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) from clinical laboratories nationwide (CDC, 2019). This structured plan provides comprehensive population surveillance and pathogen-specific verification, which forms the basis for outbreak preparedness.

3.1.2. Active Surveillance: Targeted Case-Finding and Enhanced Sensitivity

Active surveillance addresses the limitations of passive systems by employing structured, proactive case-finding strategies through engagement with healthcare providers, contact tracing, and establishing specialized testing sites or field teams. The approach can capture underreported or asymptomatic cases and generate more detailed data. In Germany, studies have shown that active surveillance identified 27% more SARS-CoV-2 infections compared to passive reporting systems alone [49,50]. Community-based house-to-house surveys identified cases overlooked by passive approaches, leading to the interruption of transmission chains and targeted interventions, demonstrating how active surveillance can complement routine reporting systems.

Although active surveillance is more sensitive, it is labor-intensive, expensive, and often requires trained personnel, laboratory capacity, and logistical coordination, making it hard to scale up, especially in low-resource settings where infrastructure gaps persist. Global surveillance networks exemplify the successful implementation of active surveillance. The Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS) combines virological and epidemiological data from over 130 countries, enabling real-time tracking of influenza variants and informing annual vaccine formulations. GISRS expanded during COVID-19 to monitor SARS-CoV-2 and RSV, demonstrating its potential for tracking other emerging threats. In addition, PV eradication relies on active surveillance for acute flaccid paralysis (AFP), with the WHO African Region conducting weekly case searches at priority health facilities to reduce the risk of undetected PV transmission in high-risk areas [51].

3.1.3. Sentinel Surveillance: High-Resolution Pathogen Monitoring

Sentinel surveillance collects detailed epidemiological and virological data from a designated network of clinics, hospitals, or laboratories that serve as representative sites. It enables the targeted monitoring of specific viruses or demographic groups, providing high-resolution information while maintaining operational feasibility. However, data may not be fully representative of broader populations, especially in underserved or rural regions.

The adaptation of the influenza sentinel network during the COVID-19 pandemic enabled the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in 7349 severe acute respiratory illness cases in Kenya, with correlation to national outbreak trends (Pearson r = 0.58) [52]. This correlation indicates that influenza surveillance networks can be helpful for early detection of new respiratory pathogens. However, the moderate strength of the relationship suggests that additional surveillance approaches are needed to fully track outbreaks. These findings in Kenya align with broader evidence that sentinel surveillance systems can serve as early warning tools for emerging pathogens by capturing shifts in pathogen circulation before they are reflected in national case-based reporting.

For instance, the European Respiratory Virus Surveillance Summary (ERVISS) collects standardized sentinel data from 38 EU countries to monitor respiratory viruses such as influenza, RSV, and SARS-CoV-2 in real time (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control) [53]. Similarly, the sentinel Enhanced Dengue Surveillance System (SEDSS) identified Zika virus circulation eight weeks earlier than passive systems in Puerto Rico, demonstrating its early warning capabilities. Nevertheless, sentinel systems may introduce geographic bias, as urban or better-resourced areas are often overrepresented [54].

The integration of genomic surveillance efforts through systems such as NREVSS and GISRS also contributes to genomic surveillance efforts and is discussed further in the Genomic Surveillance section. While traditional surveillance is widely used, approaches such as genomic surveillance, digital surveillance, and wastewater-based surveillance (WBS) are indeed considered among the most cutting-edge and innovative approaches in the field of public health surveillance; therefore, they will be covered in detail in the following sections.

3.1.4. Examples of National Surveillance Systems

While general surveillance frameworks provide the foundation for outbreak monitoring, national systems demonstrate how structural and organizational differences influence effectiveness, responsiveness, and integration with global networks. The following examples from the European Union, the United States, and China highlight contrasting approaches to centralization, data sharing, and multi-level coordination, illustrating the trade-offs inherent in national surveillance design and providing lessons for building more effective and responsive preparedness systems.

European Union Surveillance Systems:

The European Surveillance System (TESSy) serves as the central data repository for communicable disease surveillance, receiving standardized data from national public health authorities [55]. TESSy collects case-based data on diseases of public health importance, including mandatory reportable diseases (e.g., measles, pertussis, meningococcal disease, COVID-19) and optional surveillance targets.

Integration with the EU Early Warning and Response System (EWRS) enables rapid communication and mandatory reporting of suspected public health emergencies of international concern. Laboratory surveillance is coordinated through the European Reference Laboratory network and the European Surveillance System for Special Pathogens (ESSPnet), enabling rapid confirmation of suspected cases and tracking of laboratory-confirmed disease trends. During the COVID-19 pandemic, EU surveillance demonstrated both strengths (rapid identification of variants through TESSy data and real-time reporting) and weaknesses (initial delays in harmonizing case definitions across member states, variable testing capacity among countries). Taken together, these multi-level surveillance mechanisms highlight the challenges of harmonizing public health data across multiple member states, where centralized TESSy coordination must interact with heterogeneous national reporting systems.

United States Surveillance Systems:

The United States employs a decentralized surveillance system that involves the CDC, state health departments, and local jurisdictions. The National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) is the primary passive system [56]. Thousands of jurisdictions report notifiable diseases to state health departments, which then send the information to the CDC through the National Electronic Disease Surveillance System (NEDSS). Active surveillance for certain pathogens is performed by sentinel programs, which include networks of labs and clinics. For example, FoodNet conducts surveillance for foodborne diseases, while influenza is monitored through systems such as ILINet and FluSurv-NET. Event-based surveillance relies on the CDC’s Emergency Operations Center and international partnerships. During the COVID-19 pandemic, genomic surveillance grew quickly. The CDC’s SPHERES (SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology, and Surveillance) initiative brought sequencing data together from across the country [57]. However, decentralization creates variable reporting times and incomplete federal data aggregation, illustrating tensions between centralized coordination and decentralized implementation.

China’s Surveillance Systems:

China operates a centralized infectious disease surveillance system led by the National Health Commission and implemented through the China Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS/CNOTC). Launched in 2004, CNOTC is a web-based platform requiring rapid, standardized reporting of notifiable diseases nationwide, enabling national trend analysis and outbreak detection by the China CDC [58,59]. Laboratory surveillance includes the National Influenza Surveillance Network, with about 400 sentinel sites collecting weekly respiratory specimens. Recent innovations involve WBS for early detection of SARS-CoV-2. While the centralized approach enables swift policy responses, concerns persist regarding data accuracy, potential underreporting, and limited real-time transparency [59]. China has improved data sharing with international platforms, though occasional delays in outbreak reporting remain. Overall, China’s centralized system demonstrates the advantages of rapid reporting and policy response, and also illustrates trade-offs between centralized control and data transparency, highlighting the importance of accuracy and international data sharing for global surveillance.

EU, U.S., and Chinese surveillance systems demonstrate that centralized coordination accelerates reporting and policy action, decentralization enhances local responsiveness, and integrating genomic, digital, and environmental data is critical for robust, timely outbreak detection and global preparedness.

3.2. Genomic Surveillance

Genomic surveillance systematically tracks the viral genetic evolution to understand transmission dynamics, adaptation, and impact on public health. Enabled by rapid Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies and portable sequencing platforms, genomic surveillance has transformed outbreak response in both resource-rich and resource-limited settings.

Genomic surveillance transformed Ebola outbreak responses, particularly in resource-limited regions. During the 2018–2020 outbreak in the DRC, an end-to-end genomic surveillance system sequenced 17% of confirmed cases, revealing superspreading events and guiding ring vaccination strategies [16]. Portable technologies like the Oxford Nanopore MinION platform enabled real-time sequencing in field laboratories, reducing turnaround times to <48 h, demonstrating proof-of-concept for decentralized, rapid genomic workflows. In 2025, Ugandan scientists built on these advances to confirm a Sudan Ebola virus outbreak within 24 h using decentralized sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, demonstrating scalability in austere environments [60].

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the critical role of genomic surveillance in public health response. Through continuous sequencing, scientists have found mutations associated with changes in virulence, transmission dynamics, host range, immune escape, and therapeutic resistance [61,62]. The COVID-19 Genomics Consortium (COG-UK) in the UK was able to sequence more than 20% of confirmed cases throughout the country. This major project provided not only genetic information but also valuable data, combining sequencing findings with epidemiological trends to map and interrupt the transmission chain in near real time [63].

Similarly, during the monkeypox (MPXV) outbreak, rapid sequencing identified the virus and revealed about 20 times accelerated mutation rates compared to its animal host reservoir [64]. This finding highlights the importance of integrating genomics with epidemiological surveillance, maintaining sequencing capacity and multisectoral collaboration.

Recognizing these advantages, the WHO developed a long-term plan for genetic monitoring. Their 2022–2032 strategy aims to integrate sequencing capabilities into national public health systems. This includes linking them to existing surveillance platforms, building sequencing capacity, and fostering collaboration among stakeholders [64]. This represents a fundamental shift from reactive to proactive genomic surveillance in pandemic preparedness.

Several models demonstrate successful implementation of global data sharing initiatives. The Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) and the GISRS are two examples of platforms that are important for worldwide cooperation. GISRS, a WHO-coordinated network founded in 1952, currently includes laboratories from 149 countries. It connects virological and epidemiological data for real-time tracking of influenza variants, and annual vaccine selection [64]. These methods provide a robust framework for establishing genetic surveillance for other diseases.

By early 2024, GISAID had shared more than 14 million SARS-CoV-2 genomes, making it a real-time worldwide archive that was necessary to accelerate vaccine research and variant risk assessment [65]. WHO Global Genome Surveillance Strategy (2022–2032) aims to ensure that all 194 member nations have genome sequencing capabilities by 2032. This directly addresses the equity gaps that were exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic [35]. By 2022, networks like PAHO’s COVID-19 Genomic Surveillance Network had sequenced and exchanged more than 307,000 genomes throughout Latin America and the Caribbean, facilitating tailored public health interventions [66].

Genomic surveillance proved essential in tracking the exceptional 2024 H5N1 avian influenza epidemic in U.S. dairy calves, revealing that it began from a single wild bird importation, followed by reassortment with avian influenza viruses, generating the B3.13 genotype [67]. Whole-genome sequencing identified PB2 mutations facilitating mammalian adaptation, though no traditional HA mutations supporting human adaptation were detected [68]. The ongoing zoonotic risk, especially for occupationally exposed dairy workers, underscores the value of genomic monitoring for real-time outbreak management. Bulk milk testing for herd-level detection and real-time monitoring of viral transmission, informed by cow movement patterns, exemplifies the operational integration of genomic surveillance in One Health frameworks [67,69].

Although genomic surveillance holds promising potential, it encounters several challenges, including technical, logistical, analytical, and equity dimensions. Genomic surveillance demands substantial investment in sequencing infrastructure, reagent supply chains, specimen transport, and data systems integration; requirements that strain resource-limited laboratories. Also, false-negative sequencing results can arise from suboptimal viral loads, late-stage specimen collection, or variant-induced primer/probe mismatches [70].

Genomic surveillance logistics are even more demanding, including the timely transport of clinical specimens, maintaining high-throughput sequencing capacity, ensuring supply-chain stability for reagents and flow cells, and integrating data upload pipelines into national reporting systems. Many countries experienced substantial sequencing slowdowns during COVID-19 surges due to reagent shortages, staff burnout, or overwhelmed laboratory networks [70].

Bioinformatic infrastructure gaps severely limit genomic data utility. High-quality interpretation requires robust pipelines for genome assembly, variant calling, phylogenetic analysis, and metadata management—tools that are unevenly available across regions [71]. Limited computational infrastructure, inconsistent quality-control standards, and shortages of trained bioinformaticians delay data processing and reduce the comparability of genomic datasets [72]. The Proliferation of national pipelines fragments data interoperability, and incomplete or missing clinical-epidemiological metadata often hinders real-time analysis [73].

Country-level capability differences amplify disparities in outbreak detection equity. High-income countries often maintain extensive sequencing networks, stable funding, strong public health laboratories, and integrated data systems. Conversely, many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) rely on external partners for sequencing, experience long turnaround times, and lack sustained financing for surveillance infrastructure, and remain under-represented in global databases like GISAID [72,74]. These gaps delay variant detection, skew global genomic databases toward high-income nations, and undermine equitable pandemic preparedness.

These logistical and analytical barriers manifest differently depending on pathogen characteristics and outbreak context. Ebola outbreaks in remote areas face acute specimen transport challenges, while global influenza surveillance requires processing high sample volumes across hemispheres [75]. Emerging respiratory viruses like SARS-CoV-2 require rapid turnaround and extensive sequencing infrastructure, while vector-borne diseases may tolerate longer analytical windows. Consequently, pandemic preparedness requires pathogen-specific genomic strategies, sustained capacity investment, and ethical data-sharing frameworks ensuring timely, reliable outbreak intelligence.

3.3. Digital Surveillance

Digital surveillance offers a cost-efficient and time-effective alternative to traditional monitoring approaches. However, the data obtained can be noisy, making it challenging to acquire reliable and precise information compared to conventional methods. One of the pioneering entrants in digital surveillance is the Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases (ProMED), which gathers information from diverse sources, including media reports, official reports, social media, local observers, and a global network of clinicians [76]. ProMED has been instrumental in raising prompt alerts about major outbreaks, such as the Zika virus spread to the Americas and the early detection of SARS [77,78]. It gained international recognition for its thorough report and risk assessment of unusual pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China, in December 2019. HealthMap also operates alongside other prominent tools for monitoring disease outbreaks. HealthMap utilizes various sources, including news aggregators, firsthand accounts, and official and unofficial channels, to visualize alerts on interactive maps. HealthMap and ProMED have provided surveillance data to the Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources (EIOS) system developed by the WHO [79].

Additionally, modern digital systems utilize artificial intelligence and large-scale data mining to detect outbreaks earlier than traditional surveillance methods. EPIWATCH, an AI-powered epidemic intelligence system that tracks early signs of infectious disease outbreaks by searching open-source data, like news, social media, and government reports, in more than 40 languages. The system demonstrated an 88% accuracy in detecting outbreak signals. EPIWATCH reported 65 mumps outbreaks worldwide, often before WHO or CDC notifications, and it also reported early signs of Ebola and COVID-19 [80,81]. The platform is supplemented by tools such as EpiRisk, which swiftly evaluates the risk and possible severity of outbreaks using country- and pathogen-specific data, and FluCast, which predicts the severity of coming influenza seasons in real time to aid in preparedness and rapid response [82].

Other systems, such as the Global Public Health Intelligence Network (GPHIN), FluTracking, and BioSense 2.0 platforms, demonstrate the growing importance of digital surveillance in enhancing traditional disease surveillance efforts and facilitating rapid responses to emerging infectious disease threats [83]. Canada’s GPHIN, founded in 1997, employs natural language processing and machine learning to scan news, social media, and other digital sources in nine languages [84]. GPHIN enhances WHO epidemiological intelligence by approximately 20% through the filtration and prioritization of data related to public health crises. During the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, GPHIN found unusual respiratory cases in Mexico weeks before the official reports, facilitating prompt international collaboration. Nevertheless, its 2019 restructuring, which focused on local threats, temporarily reduced its global impact, highlighting the ongoing challenges of balancing resource allocation with international health security obligations.

FluTracking is an online Australian health surveillance system, launched in 2006 to detect the potential spread of influenza. It uses weekly online surveys to collect data on symptoms of influenza-like illness, vaccination status, and healthcare-seeking behaviors. With approximately 150,000 individuals in Australia and New Zealand, it provides insights into community-level transmission patterns and vaccine efficacy. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, FluTracking expanded its scope to include monitoring SARS-CoV-2 symptoms, showing that 25% of mild cases did not pursue testing. The efficiency of the platform is attributed to minimal user effort (10-second surveys) coupled with real-time analytics, which directly guide public health responses.

The BioSense 2.0 platform in the United States has been integrated into the CDC National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP), which collects electronic health information from participating emergency departments (EDs) nationwide to detect abnormalities in symptom patterns [84]. The NSSP, overseen by the CDC, employs the BioSense Platform, which has technologies such as the Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics (ESSENCE). The approach enabled the finding of localized COVID-19 clusters in early 2020 via evaluating emergency department visits with near-real-time latency, generally within 24 h, to augment conventional monitoring efforts. However, program efficacy is hampered by limitations in data exchange and system compatibility.

Moreover, several mobile apps, including Outbreaks Near Me (formerly Flu Near You), CoronaData (Robert Koch Inst), and SickWeather (US), can contribute to digital viral outbreak surveillance. Outbreaks Near Me, is an online participatory surveillance instrument used to monitor influenza-like diseases in the United States and Canada. The platform’s incorporation of vaccine locator tools significantly improves public health functionality; yet, participation bias, such as the over-representation of health-conscious populations, persists as a drawback. The CoronaData app in Germany, managed by the Robert Koch Institute, collects signs, such as heart rate and sleep patterns, from fitness trackers to detect potential COVID-19 cases [84]. This application identified presymptomatic cases during the 2020–2021 waves by analyzing deviations from baseline health values, demonstrating the potential of wearable technology in passive surveillance. Moreover, SickWeather uses AI to scan illness-related keywords in social media posts to generate maps of outbreaks in real time. During the 2017–2018 flu season, it detected regional spikes in respiratory illnesses 7–10 days before the CDC did, showing how powerful digital chatter can be at predicting things. The app also combines user-reported symptoms with Bluetooth-enabled thermometer data to enhance the surveillance network.

On the other hand, critics warn against relying too heavily on social media data that has not been verified, which could spread misinformation. Despite the advantages of digital surveillance, challenges such as data quality and standardization, privacy risks, and equity gaps may limit its effectiveness.

3.4. Wastewater-Based Surveillance

Surveillance of viruses in sewage has emerged as a valuable approach for tracking human infections and the circulation of viruses. The WHO has incorporated sewage testing for PV into its global plan to eradicate PV, working alongside existing efforts to track cases of AFP surveillance. Noteworthy instances from Finland [85], Palestine [86], and The Netherlands [86] underscore the utility of sewage monitoring in revealing the widespread geographical circulation of the virus, detecting epidemics even in areas lacking reported cases of paralysis, or even prior to the onset of poliomyelitis cases. A notable example is PV surveillance in Egypt. Egypt has implemented a comprehensive PV surveillance system since 2000, including regular training for personnel and environmental monitoring of sewage. This successful system contributed to the country achieving polio-free status in 2006, through both surveillance for AFP by healthcare workers nationwide and environmental monitoring of sewage.

At the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020), we highlighted the potential of WBS and early warning of infectious disease outbreaks, as well as for tracing the sources of COVID-19 [87]. Then, multiple studies across various countries successfully detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater. These studies include Egypt [88], Canada [89], Italy [90], the Netherlands [91], Australia [92], Germany [93], Japan [94], the United Arab Emirates [95], and the United States [96,97]. In Amersfoort, the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in wastewater six days before the first clinically confirmed cases illustrates how WBS can serve as an early-warning system. This lead time could enable public health authorities to implement targeted testing, contact tracing, and localized containment measures, potentially reducing transmission before outbreaks are recognized through conventional surveillance [91]. Ahmed et al. [92] observed varying SARS-CoV-2 RNA levels from three wastewater treatment plants in Australia, highlighting the importance of local health department collaboration for meaningful trend interpretation. Moreover, seven-week wastewater monitoring in France correlated SARS-CoV-2 levels with nationwide lockdown timing, demonstrating WBS utility for population-level outbreak tracking [98]. A study in Belgium found that wastewater sampling can help assess the community spread of respiratory viruses, such as influenza and respiratory syncytial virus [99]. This work illustrates how WBS functions as a complementary epidemiological tool to traditional clinical surveillance, providing real-time insights into subclinical and clinical virus circulation at the population level and thereby informing targeted public health interventions. A comprehensive study on WBS found that it is closely associated with COVID-19 cases in the majority of 107 US counties. These relationships were more pronounced in counties with a larger population and urban areas. In situations where routine COVID-19 surveillance data are less reliable, WBS may be employed to monitor local SARS-CoV-2 incidence trends [100].

Similarly, numerous laboratories worldwide have monitored MPXV DNA in wastewater, exploring its potential utility as a management tool for MPXV. While recent studies have shown the feasibility of monitoring MPXV using WBS, the concept remains at a proof-of-concept stage for MPXV surveillance, as most of these investigations have indicated relatively lower levels of MPXV in wastewater compared with reported levels of SARS-CoV-2 elsewhere [101]. The low detection rate of MPXV in sewage warrants investigation to determine whether it reflects a lower incidence of MPXV clinical cases or MPXV is less abundant in wastewater. Several studies on the WBS of SARS-CoV-2 and MPXV are summarized in Table 2, encompassing diverse sampling matrices, concentration methods, and detection performances.

Despite their growing importance, both WBS and genomic surveillance face inherent limitations that can compromise early detection. False negatives in WBS may arise from low viral shedding at the population level, dilution effects during heavy rainfall, chemical degradation of viral nucleic acids in sewer systems, and variability in sampling frequency or catchment size [102]. These limitations underscore the need for multipronged surveillance architectures rather than reliance on any single modality. However, data interpretation should be carefully discussed because sampling protocols such as grab, composite, traditional active, and passive sampling may influence the results [103]. Since WBS primarily relies on qPCR, PCR-inhibitory substances present in the wastewater samples may interfere with the qPCR, leading to an underestimation of the potential public health hazards of waterborne viral pathogens [104].

Beyond technical sensitivity, logistical challenges remain a significant barrier to scalable surveillance. WBS programs require standardized sampling protocols, temperature-controlled transport systems, and consistent laboratory turnaround times—conditions that are difficult to maintain during large outbreaks.

Table 2.

Wastewater-Based Epidemiology Studies for SARS-CoV-2 and Monkeypox Virus (MPXV).

Table 2.

Wastewater-Based Epidemiology Studies for SARS-CoV-2 and Monkeypox Virus (MPXV).

| Study Location | Sample Type | Concentration Method | Detection Rate | SARS-CoV(-2) Titre | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARS-CoV-2 | ||||||

| New Haven, USA | Primary sewage sludge | Direct extraction by RNeasey PowerSoil Total RNA Kit | 100% (10-week study) | 3.23–5.66 log10 gc/mL | Viral RNA tracked clinical cases 6–8 days ahead; correlated with hospitalizations. | [105] |

| Murcia, Spain | WWTP influent | Aluminum hydroxide adsorption | 84% (35/42) WWTPs | Avg (5.1–5.6 log10 gc/L) | Detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA 12–16 days before clinical confirmation in low-prevalence regions. | [106] |

| Secondary treated | 11%(2/18) | Avg(5.4 log10 gc/L) | ||||

| Porto, Portugal | Untreated/treated | PEG 8000 precipitation | 81% (39/48) in untreated liquid samples, 0% in treated samples | 0–0.15 gc/ng RNA | Wastewater-based surveillance to complement clinical testing | [107] |

| Milan, Rome, Italy | WWTP influent | a two-phase (PEG-dextran) separation | 50% (6/12 samples) | The virus was found in Italian wastewaters, even before the first reported clinical case in the country | [90] | |

| Finland | municipal wastewater influent | ultrafiltration | 79% | 6.62–8.72 log10 gc/day/person | WBS tracks SARS-CoV-2 trends at the community level | [108] |

| Madrid, Spain | Network-wide sewage | Not reported | Not reported | 0–7 log10 gc/L | Strong correlation (3–8-day lead) with hospitalizations; identified regional transmission waves. | [109] |

| Japan | Weekly/biweekly influent | PEG 8000 | 46.7% (21/45(Omicron wave) | 4.08–4.54 log10 gc/L | SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater increased when the number of confirmed cases exceeded 10 per 100,000 people. | [94] |

| Japan | Weekly influent wastewater | PEG 8000 | 67% (88 out of 132) | 3.5–6.3 log10 gc/L | Significantly higher SARS-CoV-2 RNA concentrations were detected during the Omicron variant phase | [110] |

| Northern California USA | Wastewater settled solids | - | 100% (974/974) | 6.57 log10 gc/g dry weight | Both grab and composite samples performed similarly for SARS-CoV-2 quantification in settled solid | [111] |

| Egypt | WWTP influent | PEG 6000 precipitation | 62.5% (30/48) | - | Highlighted value for LMICs surveillance. | [88] |

| Canada | Primary clarified sludge, post-grit solids | PEG-8000 PPT | N1 gene: 92.7%, N2 gene 90.6% N1 gene 79.2%, N2 gene 82.3% | 3.23–5.58 log10 gc/L | PMMoV normalization improved correlation with clinical data (r = 0.84). | [112] |

| Netherlands | WWTP influent | Ultracentrifugation | 69% (for late-epidemic rounds, 100%) | 3.4–4.3 log10 gc/L | Detected SARS-CoV-2 RNA 6 days before the first clinical cases in Amersfoort. | [91] |

| Australia | WWTP influent (3 plants) | Electronegative membrane filtration and ultrafiltration | N1 gene 30.1% E: 3.17% N2: 0% | 3.05 log10 gc/L–5.08 log10 gc/L | Early detection, 3 weeks before the first clinical case; highlighted the need for public health collaboration. | [113] |

| Germany | WWTP influent and effluent | centrifugal ultrafiltration | 77% (17/22 samples) | Inlet: 3.48–4.30 log10 gene equivalents/L Outlet: 3.43 to 4.57 log10 gene equivalents/L | The replication potential tests were negative for wastewater samples. | [93] |

| UAE | Municipal wastewater (Influents and effluents) | Ultrafiltration/PEG 8000 PPT | 85% (untreated) | 2.88 log10 gc/L–4.53 log10 gc/L | WBE can help authorities take prompt actions to contain a potential outbreak | [95] |

| USA (Montana) | Municipal wastewater(influent) | Centrifugal ultrafiltration | 53% (9/17) | 2.85–4.12 log10 gc/L | Viral titers correlated with case numbers; provided an early warning. | [97] |

| USA (Massachusetts) | Municipal wastewater | PEG precipitation | 100% (all samples) | 1.76– 2.48 log10 gc/mL | Viral titers anticipated clinical trends by 4–10 days. | [96] |

| France | WWTP influent (3 plants) | Centrifugation | 100% | 4.70–6.48 log10 gc/L | Viral RNA trends mirrored the national lockdown and resurgence. | [98] |

| Veneto, Italy | Raw wastewater | PEG precipitation. | High correlation with clinical cases | 0–2.85 log10 gc/µL | Wastewater peaks preceded clinical cases by 5.2 days; CUSUM charts are effective for early outbreak detection | [114] |

| Chengdu, China | A composite Wastewater treatment plant influent | PEG precipitation | 0.012–3.27% | 0.21–1.62 log10 gc/mL | Model predicted infections using viral load and population size; provided early warning for FISU Games. | [115] |

| Arkansas, USA | Wastewater treatment plant samples | filtered and eluted to approximately 500 µL using a column-based system | >1 log10 gc/mL–6 log10 gc/mL | Amplicon sequencing tracked variants effectively; S-gene detection was lost with JN.1 predominance. | [116] | |

| Denmark | Influent wastewater | NanoTrap Microbiome A particles | consistent detection (LoD: 4 copies/reaction for N1, 2 for N2) | Including wastewater SARS-CoV-2 levels in models improved the prediction accuracy of COVID-19 hospital admissions up to 2 weeks in advance | [117] | |

| Monkeypox Virus | ||||||

| Study Location | Sample Type | Concentration Method | Detection Rate | MPXV Titre | Key Findings | Reference |

| Netherlands | Wastewater 24-h composite | Centrifugation | 42% (45/108 samples) | Not quantified | The detection patterns in wastewater aligned with the confirmed monkeypox cases | [118] |

| Baltimore, USA | Grab, 24-h composite | PEG precipitation, adsorption-elution | 72% (13/18 samples) | Not quantified | PEG precipitation is more effective than AE; no correlation between wastewater MPXV and clinical cases | [119] |

| Paris, France | 24-h composite | Centrifugation | 10.6% (34/321) | 3.30−4.60 log10 gc/L | Strong correlation between MPXV concentration and weekly MPXV cases; early detection demonstrated | [120] |

| California, USA | 24-h composite influent, solids | Nanotrap particles (liquid), buffer suspension (solids) | 26.5 (76/287) | 4.4 log10 gc/g (103-fold higher in solids) | MPXV DNA is more concentrated in solids; positive correlation with reported cases | [121] |

| Miami, USA | Grab, Wastewater | Electronegative filtration | 3.1% (1/32, hospital Wastewater) 38.5% (5/13 regional WWTP | 3.8 log10 gc/L 4.0–4.42 log10 gc/L | First detection in July 2022; positivity increased during the study period; detected in hospital and municipal wastewater | [122] |

| Canada | 24-h composite | Centrifugation | G2R_G: 16%, G2R_WA: 22%, G2R_NML: 76% | Not specified | In-house G2R_NML assay outperformed CDC assays for MPXV surveillance | [123] |

| Italy | Airport Wastewater 24-h composite | PEG/NaCl precipitation | 15% (3/20) | Not quantified | Detection using N3R, F3L, CDC G2R_G; airport wastewater also analyzed | [124] |

| Thailand | Grab | Centricon Plus-70 ultrafilter | 9.52% (6/63) | 4.2−4.9 log10 gc/L | Feasibility demonstrated in Southeast Asia; positivity increased over the monitoring period | [125] |

| Spain | Grab | Aluminum adsorption-precipitation | 18% (56/312 samples) | 3.3−4.9 log10 gc/L | Large-scale study; aluminum-based concentration effective for MPXV detection | [126] |

| Multiple US States | 24-h composite untreated | Vacuum filtration + pre-amplification | 13% (8/60 samples) | Not quantified | Pre-amplification reduced false negatives by 87%; detected in multiple states; detection during case increases and waning. | [127] |

| Slovenia | 24 h composite untreated Wastewater | affinity-based capture using Nanotrap particles | 0% during the monitoring period | Not detected | No MPXV detected June–September 2023; validated methods for emergency response. | [128] |

| Zibo, China | Wastewater at high-risk sites | Magnetic beads, PEG, ultrafiltration | 14.3 (1/7) Detected September 2023 | 3.1 log10 gc/mL | First MPXV detection in Chinese wastewater; NGS confirmed IIb branch C.1 lineage; suggested hidden transmission | [129] |

| United States | Composite/Grab Wastewater samples | Various methods | 2.7% (95/3492) | Not specified | Sensitivity increased with case number; high predictive value; useful complement to case surveillance | [130] |

| USA | Composite | Adsorption extraction | 3.8% (5/131) | 3.2 log10 gc/L | Same-day result is feasible with the affinity capture method and microfluidic digital PCR | [131] |

| Poland | Composite | Not specified | 20.5% (9/44) | Not specified | The MPXV virus detection does not correlate with the number of hospitalizations in Poznan, Poland | [132] |

| Korea, Seoul | Grab&composite | Dyna beads of the KingFisher equipment | 1.2% (1/82) | Not specified | Wastewater-based surveillance is feasible for tracking low-prevalence, socially stigmatized pathogens at the community | [133] |

While WBS and other surveillance tools provide valuable early warning, coverage remains fragmented and delayed, particularly in low-resource settings. Global health assessments have noted incomplete data reporting, limited laboratory capacity, and underutilized environmental and One Health data streams. Addressing these gaps requires expanding lab and field capacity, improving data sharing, and integrating human–animal surveillance networks (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Key surveillance tools across domains and their corresponding gaps in coverage, capacity, and integration.

3.5. A Coordinated International Effort and Data Sharing

The WHO established a global disease surveillance infrastructure through its International Health Regulations (IHR), adopted in 1951 and updated in 2005 to ensure coordinated outbreak response [137]. GISRS provides standardized communication protocols and reporting frameworks to prevent disease spread and address specific pandemic threats [12].

The emergence of COVID-19 prompted the WHO’s swift declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and the implementation of a global surveillance system. This action was built upon lessons learned from previous outbreaks such as SARS (2003) and H1N1 (2009) [138], highlighting the crucial role of timely and extensive data for decision-making supported by evidence. Projects such as the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework, adopted in 2011, reinforce this principle by ensuring equitable access to vaccines through virus-sharing agreements. WHO employs standardized methods and continuously updates guidance to maintain data consistency across diverse sources.

The 2009 H1N1 pandemic demonstrated critical gaps in real-time data exchange, which led to the development of GISAID. By removing obstacles to pre-publication data access, GISAID, introduced in 2008, has transformed genomic data sharing and enabled real-time genomic surveillance of influenza [139]. Moreover, during the COVID-19 pandemic, GISAID facilitated the sharing of over 15 million SARS-CoV-2 sequences, as of mid-2023, hence aiding in the tracking of variants and informing vaccine development [64].

The WHO Health Emergencies Programme, Epidemic Intelligence from Open Sources (EIOS) system, launched in 2017, supplements these efforts by using AI to scan over 150,000 news and social media posts daily across more than 40 languages. Its evaluation in Africa found that EIOS detected 81% of public health events, often before the official reporting, with 47.4% sensitivity in identifying outbreaks like Ebola and COVID-19 before national notifications [135,140].

In addition, the Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN, https://goarn.who.int) (accessed on 10 August 2025) mobilizes resources and experts during public health emergencies. It consists of more than 200 technical institutions and networks worldwide, by sending field epidemiologists, boosting laboratory networks, and improving risk communication. GOARN played an essential role during the 2018 Ebola outbreak in the DRC. Similarly, the CDC Global Disease Detection (GDD) Operations Center, a more specific program that plays a pivotal role in outbreak response, conducts event-based surveillance. It acts upon rumors and signals, even when governments hesitate to disclose information, utilizing media reports and other open-source data. For example, in 2017, media reports alerted the GDD center to a potential dengue outbreak in Egypt, enabling early action [141].

The GDD collaborative approach prioritizes information sharing through established platforms, fostering collaboration among stakeholders. This was exemplified during the 2018 Ebola outbreak in the DRC, where a shared data portal facilitated a coordinated response. The GDD swift response and ability to debunk misinformation were also demonstrated in 2014 during Ebola outbreak in Guinea and in 2022, smallpox rumors in Yemen [141].

4. Diagnostic and Laboratory Capacity

In crafting a comprehensive preparedness plan for viral outbreaks, diagnostics play a crucial role in rapidly detecting epidemic pathogens and guiding efficient public health interventions aimed at effective outbreak containment. Governments should ensure that readily accessible, cost-effective, and high-performing diagnostic tests are available on a large scale within weeks of identifying an emerging outbreak. This requires systematic investment in adaptable diagnostic platforms, robust laboratory infrastructure, and coordinated response frameworks, ensuring tests are rapid, sensitive, and deployable across various settings, including homes, Point-of-Care (POC) facilities, and central laboratories. These technologies should also be affordable and accessible to support national requirements for regular diagnostic testing, screening, and surveillance during prolonged periods of mass demand.

During major outbreaks, global supply chains quickly collapsed, causing widespread shortages of extraction kits, enzymes, lateral-flow membranes, cartridges, and even basic consumables [142]. These constraints were intensified by export bans, competition between countries, and dependence on a small number of manufacturers. Many POC assays also require cold-chain storage, making them difficult to use consistently in low-resource or remote settings where high temperatures degrade reagents and reduce test sensitivity [143]. Cartridge-based systems faced manufacturing bottlenecks that prevented them from meeting the demand required during large-scale surges [144].

Regulatory pathways, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) and the WHO’s Emergency Use Listing, accelerated the approval of new assays, allowing for the rapid expansion of testing early in the pandemic. However, differences in approval criteria across countries, occasional adoption of suboptimal tests, and variable regulatory capacity highlighted the need for coordinated global regulatory frameworks, shared validation standards, and stronger infrastructure in lower-resource settings [145].

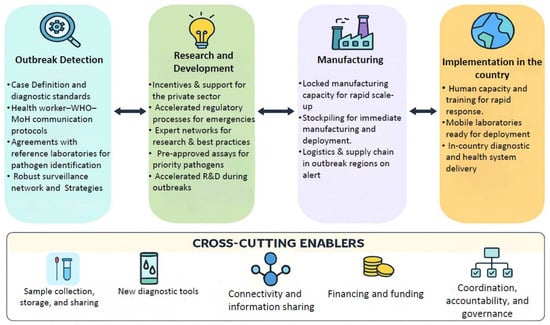

A preparedness framework encompasses key components such as the value chain stages of outbreak detection, confirmation, and response, along with cross-cutting enablers like financing, coordination, and human capacity (Figure 2). It emphasizes the importance of research, manufacturing, and in-country implementation for diagnostic readiness based on Perkins et al. [146]. Furthermore, it underscores the need to address both known and unknown pathogens with tailored activities and effective outbreak response measures. As a result, various industries and academic institutions are working on the development of quick, user-friendly, and POC diagnostic kits to ensure sensitive and specific viral detection. These diagnostic approaches can be categorized into two main groups: nucleic acid-based diagnosis and serology-based diagnosis. While diagnostics are a fundamental component of outbreak preparedness, this review offers a strategic overview rather than detailed technical specifications of individual diagnostic methodologies. We present a broad summary of key approaches—such as nucleic acid-based tests, serological assays, and emerging technologies—to illustrate their roles in early detection, surveillance, and coordinated response efforts. More detailed discussions of specific diagnostic methods are reviewed in [147,148].

Figure 2.

A framework for diagnostic preparedness. The figure illustrates the diagnostics preparedness value chain, highlighting phase-specific activities and five cross-cutting enablers that collectively strengthen rapid outbreak detection and response. Bidirectional arrows highlight the continuous feedback and interdependence between phases, ensuring adaptability and improvement across the system. The figure was prepared using Microsoft PowerPoint and Icons adapted from Flaticon (www.flaticon.com) (accessed on 1 September 2025).

Diagnostic development can be characterized by Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs), a scale (1–9) for maturity from basic research to fully proven products (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, n.d.). In pandemic preparedness, high TRL (≈9) means widely available, licensed tools; whereas lower TRL indicates early or prototype stages. For example, the COVID-19 experience shows SARS-CoV-2 diagnostics (PCR and rapid tests) reached TRL ≈ 9, while many other pathogens lack such readiness. Table 4 summarizes representative viral categories, demonstrating that mature diagnostic platforms (PCR, antigen tests) score high, whereas novel or emerging diagnostic tools score lower.

Table 4.

Technology readiness of diagnostics and vaccines by major viral category. “TRL ≈ 9” indicates widely deployed tools (e.g., PCR tests or licensed vaccines), lower values indicate earlier stages.

4.1. Nucleic Acid-Based Diagnosis

The gold standard method for detecting viral nucleic acid is (RT)-qPCR. However, its technical accuracy has not yet resulted in effective SARS-CoV-2 containment during the early pandemic phase, highlighting the complexity of outbreak control beyond diagnostic capability [150]. In February 2020, the FDA expanded the EUA to enable qualified laboratories to develop and deploy in-house SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic assays [151], primarily performed in hospital and reference laboratory settings [152]. While RT-qPCR demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity under optimal conditions, its performance can be compromised by several factors. Significant variations in viral RNA sequences can influence results from RT–qPCR utilizing different primer sets targeting various parts of the viral genome, potentially leading to false negatives due to viral evolution. Also, PCR sensitivity might be reduced in the case of multiplex detection.

Another format is droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), which offers the absolute quantification of the target gene in samples without a standard curve. The technique relies on partitioning samples into thousands of individual droplets, enabling more precise quantification than conventional methods. Moreover, research indicates that ddPCR demonstrates superior sensitivity and specificity in identifying viruses within samples with low RNA abundance [153]. A comparative study examining the sensitivity of RT-qPCR versus ddPCR of ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 revealed positive ddPCR signals in 26 samples that were negative via RT-qPCR [154]. Similarly, Yu et al. [155] studied the ORF1ab and N genes of SARS-CoV-2 in different samples. They found that ddPCR was better than RT-qPCR at identifying the virus in samples with low viral loads. Nonetheless, it is important to note that ddPCR entails expensive instrumentation and longer turnaround times compared to RT-qPCR for obtaining results.

Isothermal amplification of nucleic acid is an alternative to nucleic acid amplification based on thermal cycling. The isothermal process makes the amplification method in POC diagnostic equipment possible and helps to develop virus RNA detection methods in resource-limited areas. Isothermal amplification reactions can be classified into three types depending on the reaction kinetics, including linear, exponential and cascade amplification. Among these isothermal amplification reactions, exponential amplification has a higher efficiency and detection sensitivity. Many exponential amplification methods have been proposed, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP), strand displacement amplification (SDA), and rolling circle amplification (RCA). Taking the hand-foot-and-mouth disease (HFMD) virus as an example, we systematically summarized the current status of isothermal nucleic acid amplification techniques for HFMD and discussed the advantages and drawbacks of various isothermal amplification processes [156].

The LAMP technique has attracted considerable attention because it enables rapid, sensitive, and specific detection under constant temperature, thereby eliminating the need for complex thermal cycling equipment. In this context, Abbott Diagnostics has introduced a POC device utilizing RT-LAMP for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in respiratory swabs [157]. LAMP method offers rapid results, with a turnaround time of just 13 min. However, its limitation to processing only one sample per run hinders the scalability of the technique. Numerous studies have highlighted the superior or comparable performance of LAMP compared to RT-qPCR for COVID-19 diagnosis. Coupled with its simplicity, speed, and POC capabilities, RT-LAMP stands out as an outstanding alternative to RT-qPCR [158]. Notably, smartphone-based LAMP assay demonstrates comparable sensitivity and quantitative accuracy to RT-qPCR for both SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus detection [159]. Apart from smartphones, different isothermal approaches can be combined with the amplification reaction in a multichannel readout, such as microfluidic devices.

Due to the high-fidelity recognition of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas technology, which offers single-base resolution and powerful, flexible signal transduction through efficient trans-cleavage, such as CRISPR/Cas13a for virus RNA recognition, it has become a promising method for virus detection. However, the sensitivity of CRISPR/Cas may be insufficient for viral detection in environmental samples due to low viral concentrations. Therefore, some studies have attempted to combine CRISPR/Cas with isothermal amplification, utilizing the specificity of CRISPR/Cas to solve the false positive problem of isothermal amplification and using the high sensitivity of isothermal amplification to improve the LOD of CRISPR/Cas. For example, we developed a portable paper device based on CRISPR/Cas12a and RT-LAMP with 97.7% sensitivity and 82% semiquantitative accuracy for SARS-CoV-2 detection in wastewater, highlighting a promising point-of-use approach for WBS [160].

4.2. Immunological Assays

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is the most commonly used technique for serological testing across various diseases. However, cross-reactivity among antibodies elicited by closely related pathogens can complicate interpretation, and ELISA results should be considered preliminary rather than confirmatory. As demonstrated by Maeki et al. [161], cross-reactivity among flavivirus antibodies can produce false-positive ELISA results, and the use of paired serum neutralization tests is essential for accurate interpretation [161], illustrating the importance of confirmatory testing beyond standard ELISA [162].

ELISA allows for the identification of multiple antigenic proteins or various pathogens (referred to as multiplexing). Automation of this method enables high-throughput analysis and the capability for POC detection [163]. High-throughput automated ELISA demonstrates superior performance for large-scale diagnostic applications. Examples of high-throughput automated ELISA include Luminex X-Map and Simoa technologies that can be adapted for the multiplex detection of viral antigens or antibodies. Luminex X-Map technology represents a revolutionary advancement in multiplex immunoassay, utilizing spectrally distinct fluorescent microspheres to enable the simultaneous detection of multiple targets, including both proteins and nucleic acids [164,165,166]. Single Molecule Array (Simoa) technology provides unprecedented sensitivity enhancement, improving detection capabilities over 1200-fold compared to conventional ELISA. Simoa platforms achieve single-molecule sensitivity in the attomolar range (10−16 M) compared to conventional immunoassay detection limits in the femtomolar range (10−13 M). Automated Simoa instruments demonstrate throughput of 66 samples per hour with coefficients of variation below 10% [167].

The lateral Flow Assay (LFA) is a rapid diagnostic technique for qualitative serological analysis. Results can typically be obtained within 10–30 min, making it feasible for testing in POC setting. The rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and minimal need for specialized personnel make LFA well-suited for the extensive sample screening demanded during a pandemic [168,169]. It is also a self-testing antigen (Ag) test that played a significant role in the containment of COVID-19. Systematic reviews of COVID-19 lateral flow devices reveal sensitivity ranging from 64% to 76% across different commercial assays, while specificity consistently remains high, with 4 out of 5 LFAs achieving 100% specificity [170].

Generally, serological tests provide swift, cost-efficient, and on-site detection capabilities, making them ideal for high-throughput testing during outbreaks. As a result, (qRT)-PCR is often used as a confirmatory test, particularly when serological tests yield negative results in symptomatic cases. Despite these limitations, serological tests provide valuable insights into population-level immunity status and remain essential components of comprehensive diagnostic preparedness strategies.

Beyond manual lateral flow rapid antigen tests, analyzer-based immunochromatographic platforms offer automated signal interpretation and improved standardization. The Sofia 2 SARS Antigen Fluorescent Immunoassay (FIA) represents the primary widely deployed analyzer system that employs optical fluorescence detection with algorithmic interpretation of signal intensity, thereby reducing operator subjectivity and eliminating visual misreading that can occur with colorimetric lateral flow tests [171,172]. While Abbott Binax NOW is a rapid point-of-care immunochromatographic antigen test, it is a manual lateral flow assay that requires visual interpretation rather than an automated instrument-based system.

In terms of performance, analyzer-based systems like Sofia 2 FIA demonstrate performance substantially dependent on sample viral load and symptom status. Overall sensitivity ranges from 60.5% to 94.2% across populations, with sensitivity reaching 87–99.1% in samples with high viral loads (RT-PCR Ct ≤ 25) but declining to 28.7% or lower for low viral load samples (Ct > 30) [171,173]. Asymptomatic individuals demonstrate particularly low sensitivity: Sofia 2 achieved 41.2% sensitivity in asymptomatic populations despite specificity >98% [174]. When compared directly to high-quality manual lateral flow tests, analyzer-based fluorescence detection shows modest superiority primarily at high viral loads; both formats achieve >90% sensitivity in high viral load samples and <30% sensitivity in low viral load samples [175]. Critically, antigen test sensitivity declines over the course of infection: Abbott Binax NOW demonstrated 96.3% sensitivity in initial testing but declined to 48.4% in repeat testing 7–14 days later, reflecting waning viral shedding during recovery [176].

Regarding deployment, analyzer-based systems have been deployed in healthcare facilities, occupational health settings, and high-volume screening venues during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, these systems require more substantial infrastructure compared to manual rapid antigen tests, including electrical power, instrument calibration, maintenance contracts, and initial capital investment ($3000–$10,000), substantially limiting deployment in resource-limited settings where rapid diagnostic capacity is most needed [172,177].

Looking ahead, emerging technologies for antigen detection include electrochemical impedance spectroscopy-based biosensors, surface plasmon resonance sensors, and other label-free detection platforms that measure changes in electrical properties or optical signals when an antigen binds to immobilized antibodies. These platforms offer potential advantages of high sensitivity (detection limits from 0.99 picogram/mL to 200 nanogram/mL depending on platform design, with select systems achieving sensitivity approaching or exceeding conventional ELISA), rapid analysis (typically 10–30 min), and minimal sample preparation [178,179]. While certain systems have achieved clinical validation in laboratory settings, demonstrating 99% sensitivity and 100% specificity, most diagnostic platforms remain in development or early clinical validation phases and have not yet transitioned to routine point-of-care implementation or widespread clinical deployment.

The WHO’s prioritized research agenda for diagnostic technologies, including the Blueprint Pathogen X Research Agenda (2022) and the July 2024 updated priority pathogen list, targets ‘Prototype Pathogens’ to accelerate the development of point-of-care diagnostics and therapeutics. This approach reflects a strategic recognition that timely detection of unknown or emerging pathogens is essential for global health security. By emphasizing rapid, accessible diagnostics, particularly in resource-limited settings where zoonotic spillovers are most likely, the agenda directly informs capacity-building priorities, resource allocation, and the design of surveillance systems to mitigate outbreak risk before widespread transmission occurs.

4.3. Impact of Poor Diagnostic Capacity

Limited diagnostic capabilities in healthcare systems can seriously impede outbreak control efforts. This was evident during the 2016–2017 yellow fever (YFV) outbreak in Central Africa [180]. Despite the endemic nature of YFV across Africa and the availability of an effective vaccine for nearly eight decades, the preparedness for the outbreaks in Angola and Nigeria during this period was inadequate [181]. Although detecting YFV through ELISA was technically possible at the national level, the shortage of crucial reagents prevented labs from testing most suspected cases. The minimal case reproduction numbers observed during the Ebola outbreak indicate that even slight enhancements in interrupting transmission can significantly impact disease control. Additionally, during the 2013–2016 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, it took three months from the emergence of the index case to the identification of the causative agent. A post-epidemic modeling study found that if 60% of Ebola patients were diagnosed within a day instead of five days, the percentage of people infected in the population (attack rate) could have dropped from 80% to nearly zero [182]. These findings underscore that even modest improvements in diagnostic speed can dramatically enhance transmission interruption and disease control outcomes.

Influenza research has led to numerous laboratory tests for identifying influenza and its subtypes, allowing for rapid development of testing for novel strains, particularly for pre-pandemic strains. Human cases of pre-pandemic strains are quickly identified and monitored to contain potential pandemic outbreaks. Despite this success, the delayed development and distribution of diagnostic testing kits for SARS-CoV-2 led to delayed case identification and contact tracing, causing widespread viral transmission. Interestingly, SARS-CoV-2 detection in the USA occurred two months after its initial identification in China, resulting in delays in implementing RT-qPCR tests and facilitating viral transmission. Hence, there is a need for unbiased detection methods that do not rely on viral sequence data to diagnose infections, such as metagenomics analysis [183]. This approach could potentially identify unknown pathogens during the critical early phases of outbreaks when conventional sequence-based diagnostics are unavailable. However, implementation of this technology requires significant infrastructure investment and technical expertise, which may be lacking in resource-limited settings where many outbreaks originate.

Together, the absence of accessible and definitive diagnostic tools has been identified as a critical gap in global health security infrastructure. The lack of accessible and definitive diagnostic tools is especially critical for outbreaks that emerge in rural areas, such as Lassa fever, or affect mobile populations, like MERS-CoV, where limited infrastructure and rapid population movement exacerbate transmission risks. Common critical obstacles to diagnostic preparedness and potential remedies are presented in Table 5, modified from Kelly-Cirino et al. [184], summarizing key challenges in research, development, logistics, and healthcare systems along with proposed solutions.

Table 5.

The challenges to diagnostic preparedness and potential solutions.

5. Prevention and Control Measures

5.1. Vaccination

Vaccines fall into two main categories: conventional and next-generation platforms. Conventional vaccines utilize traditional approaches, including live-attenuated, inactivated, or subunit formulation derived from weakened or killed pathogens. While these platforms are effective for numerous diseases, they exhibit limitations when confronting complex pathogens and require extended development timelines. Next-generation vaccines represent a paradigm shift in vaccine development, employing advanced biotechnological approaches including genetic engineering, viral vectors, and nucleic acid-based platforms. These approaches offer a faster, potentially more effective and adaptable solution to emerging pathogens, exemplified by rapid COVID-19 vaccine development [185,186].

The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines can be attributed to two decades of focused research on coronaviruses following the 2002 SARS-CoV outbreak in Asia and the 2012 MERS-CoV emergence in the Middle East. Reflecting on the SARS-CoV-1 outbreak in 2002, it is evident that despite its relatively low number of deaths and infections, its high mortality rate and ease of transmission resulted in substantial global disruption. The epidemic concluded, coinciding with the commencement of vaccine development efforts. Subsequently, with the closure of wet markets and the cessation of human-to-human transmission from civets, the disease has not resurfaced. Consequently, research on SARS-CoV-1 vaccines was discontinued, and funding for such efforts was reduced.

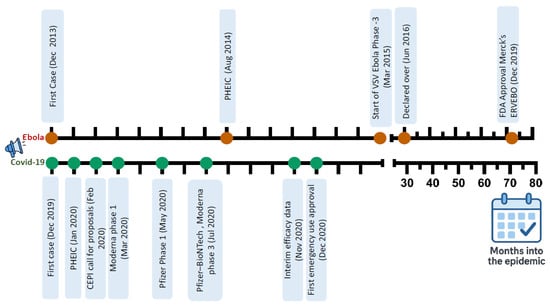

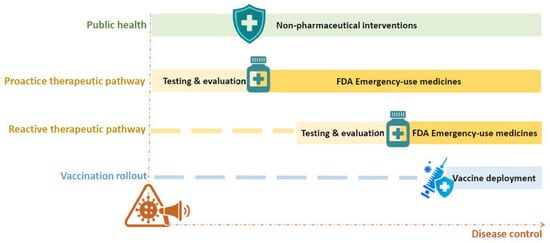

While the 2014 Ebola epidemic lasted over two years and caused over 11,000 deaths, it allowed sufficient time for the development and clinical evaluation of various vaccines (Figure 3). By the epidemic’s end, one of these vaccines, the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine, demonstrated high efficacy in ring vaccination trials. In contrast, the COVID-19 pandemic presented an unprecedented timeline challenge: the entire process, from identifying the virus and genome sequencing to analyzing early data on vaccine efficacy, was completed remarkably quickly, within a year [187].

Figure 3.