Abstract

The epitranscriptomic modification m6A is a prevalent RNA modification that plays a crucial role in the regulation of various aspects of RNA metabolism. It has been found to be involved in a wide range of physiological processes and disease states. Of particular interest is the role of m6A machinery and modifications in viral infections, serving as an evolutionary marker for distinguishing between self and non-self entities. In this review article, we present a comprehensive overview of the epitranscriptomic modification m6A and its implications for the interplay between viruses and their host, focusing on immune responses and viral replication. We outline future research directions that highlight the role of m6A in viral nucleic acid recognition, initiation of antiviral immune responses, and modulation of antiviral signaling pathways. Additionally, we discuss the potential of m6A as a prognostic biomarker and a target for therapeutic interventions in viral infections.

Keywords:

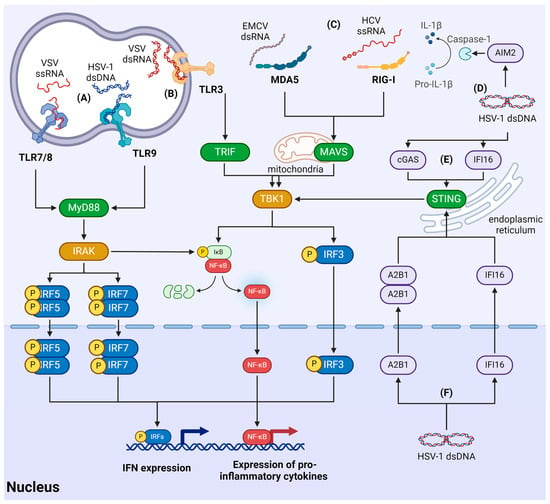

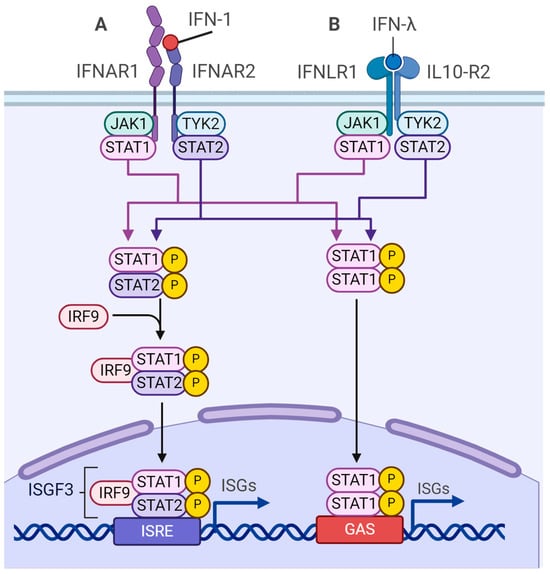

TLR; RLR; herpesviruses; hepatitis viruses; coronaviruses; retroviruses; flaviviruses; adenoviruses 1. Introduction

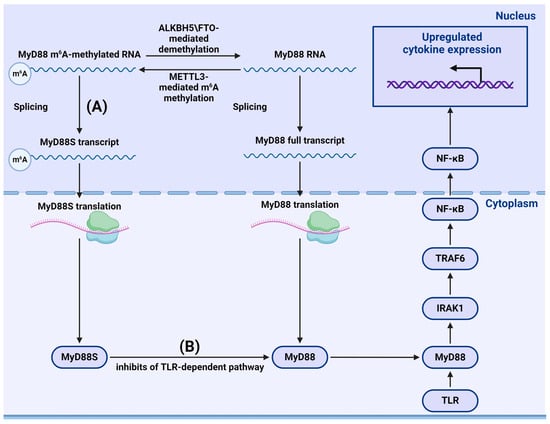

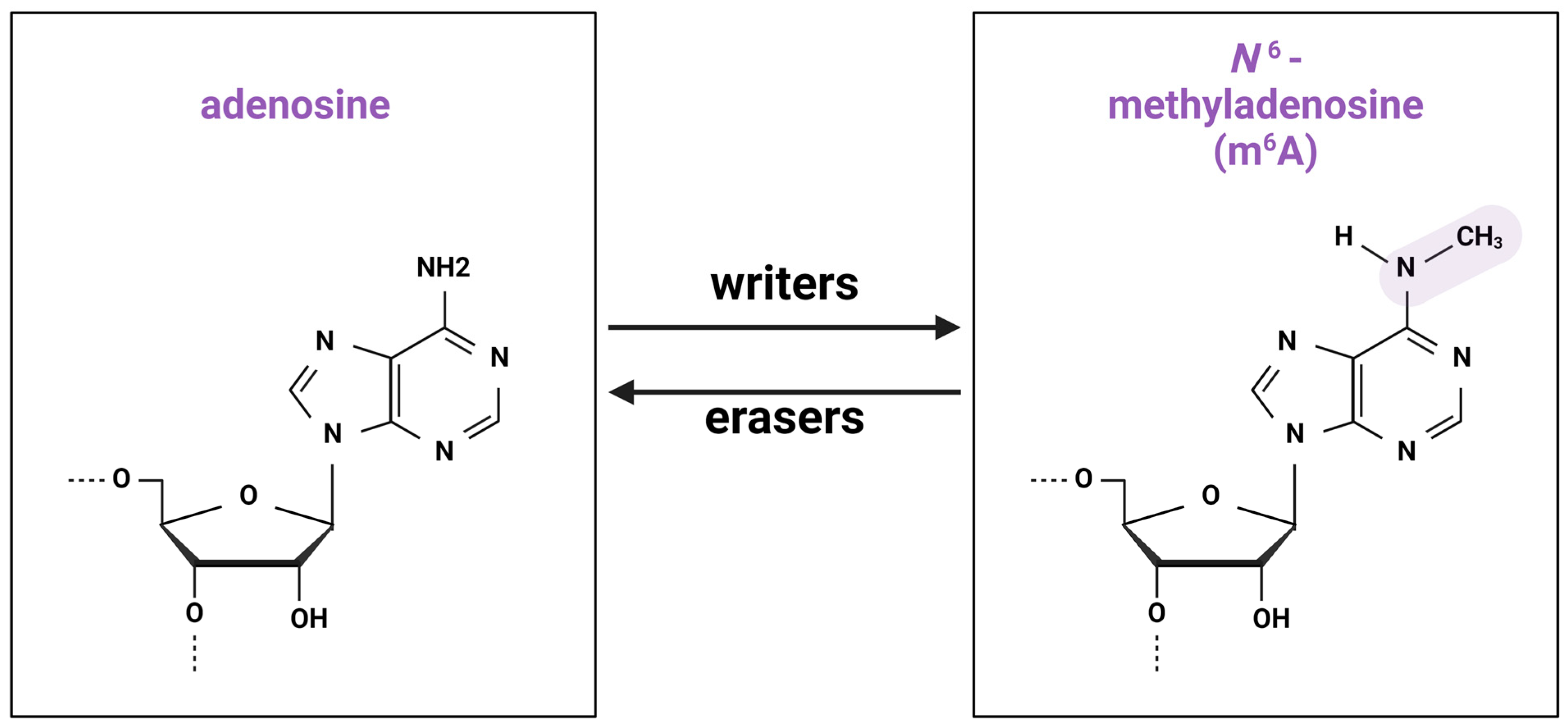

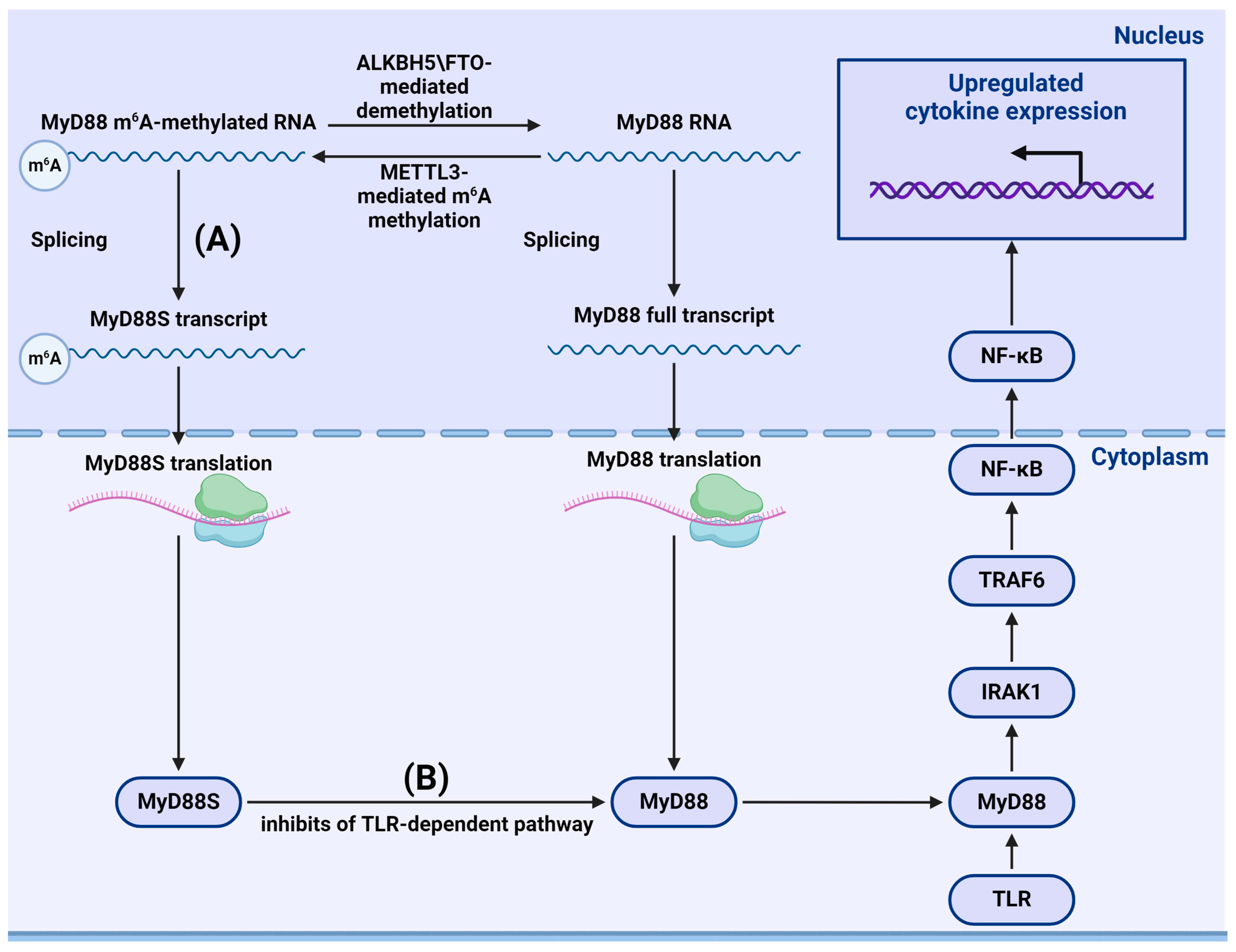

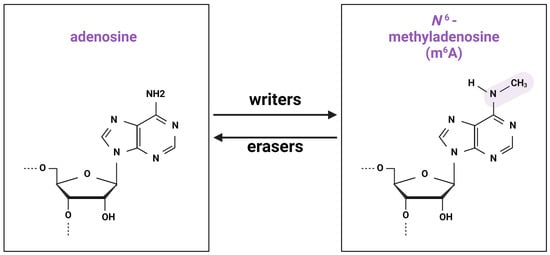

In 1974, Desrosiers, Friderici, and Rottman described a new modification of RNA, N6-methyladenosine (m6A), in Novikov’s hepatoma cells [1]. m6A is a post-transcriptional RNA modification involving the addition of an extra methyl group to nitrogen 6 of adenosine. Currently, more than 150 types of RNA modifications are identified [2], of which m6A is the most prevalent (Figure 1) [3].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of m6A modification. Methylation and demethylation is implemented by groups of “writers” and “erasers”, correspondingly.

The m6A modification has been observed in almost all types of RNA, including messenger RNA (mRNA) [4], ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [5], and microRNA [6]. m6A typically occurs at the consensus motif RRm6ACH ([G/A/U][G/A]m6AC[U/A/C]). Ke et al. demonstrated that 93% of m6A modifications in partially spliced chromatin-associated RNA were found within exonic regions, although intronic sequences are three-fold more abundant [7]. In addition, Dominissi et al. showed that 87% of m6A were located in exons longer than 400 nucleotides. Most m6A markers (37%) were found in coding sequences; 28% were localized in the 400-nucleotide window centered on stop codons; 20% were located in the 3′ untranslated region (3′-UTR); and 12% in transcription start sites (TSS). The relative enrichment of m6A bases was highest in the stop codon region and TSS [8].

The m6A modification plays a role in almost all biochemical processes related to RNA metabolism, influencing RNA stability [9] and regulating nuclear export of mRNA [10], splicing [11], and translation [12].

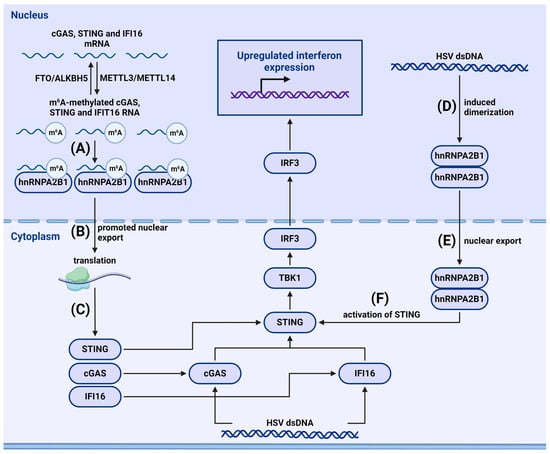

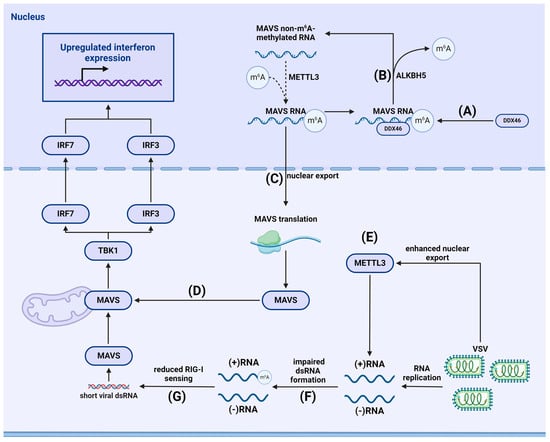

Viral RNA can also undergo methylation [13], and m6A influences various processes that regulate the viral cycle [14]. Thanks to m6A markers, cells can recognize their RNA as “self” and protect it from the innate immune system, whereas the genetic material of viruses can frequently be recognized as foreign because it does not bear m6A-modified nucleotides [15]. However, viruses have learned to evade cellular immunity by utilizing m6A modifications [16].

In this manuscript, we provide a focused review of the role of m6A in regulating innate immunity and shaping antiviral defenses. We consolidate recent results demonstrating the role of m6A methylation in viral immune evasion and antiviral immune signaling.

2. Regulation of m6A Modification

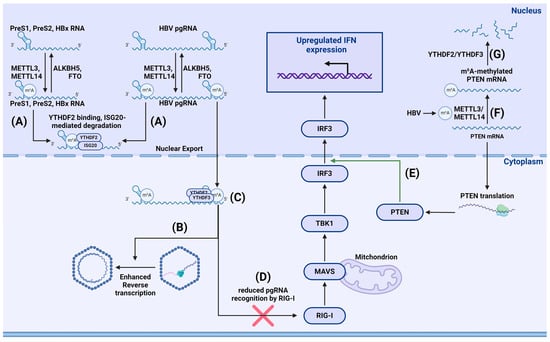

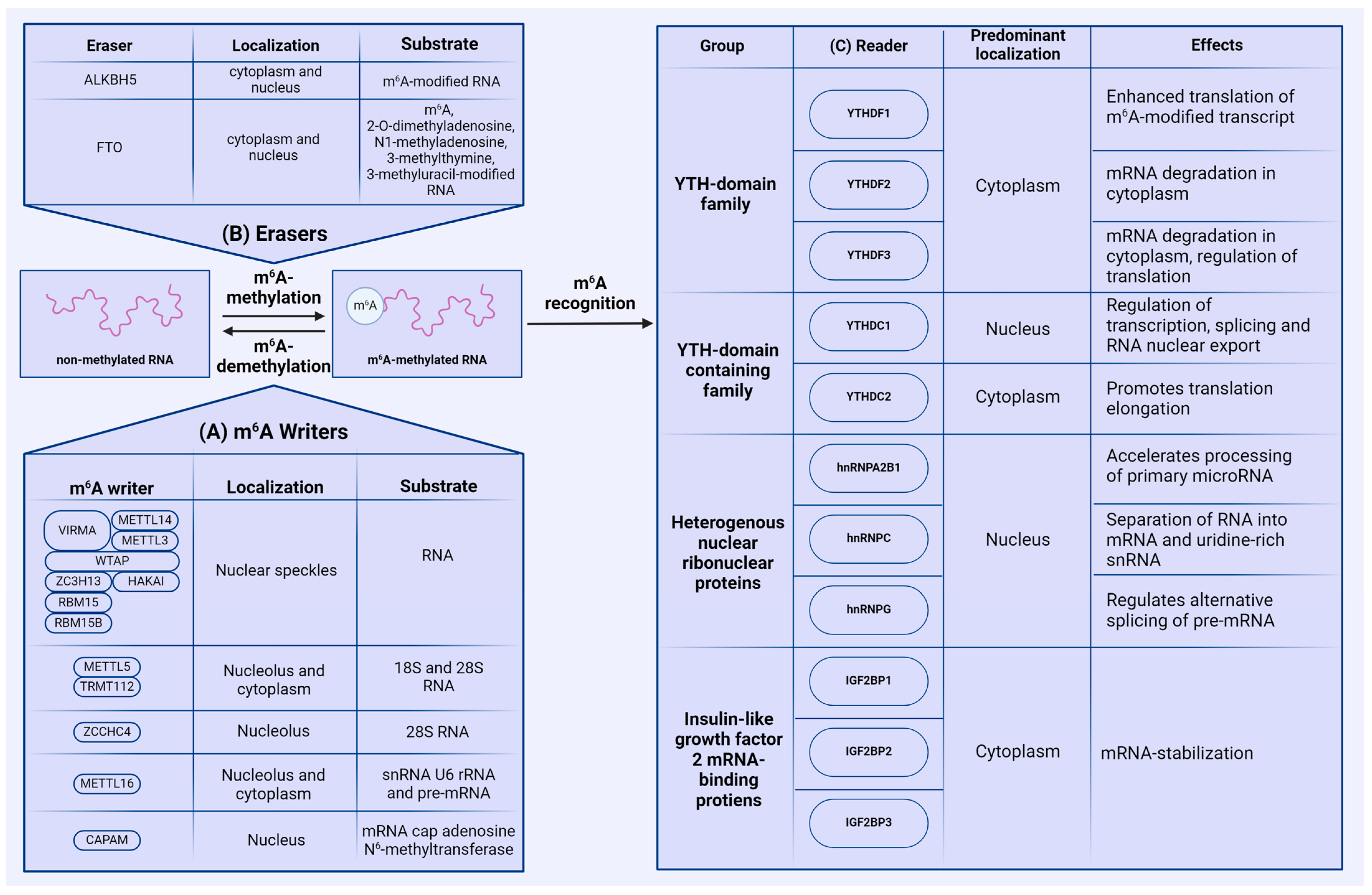

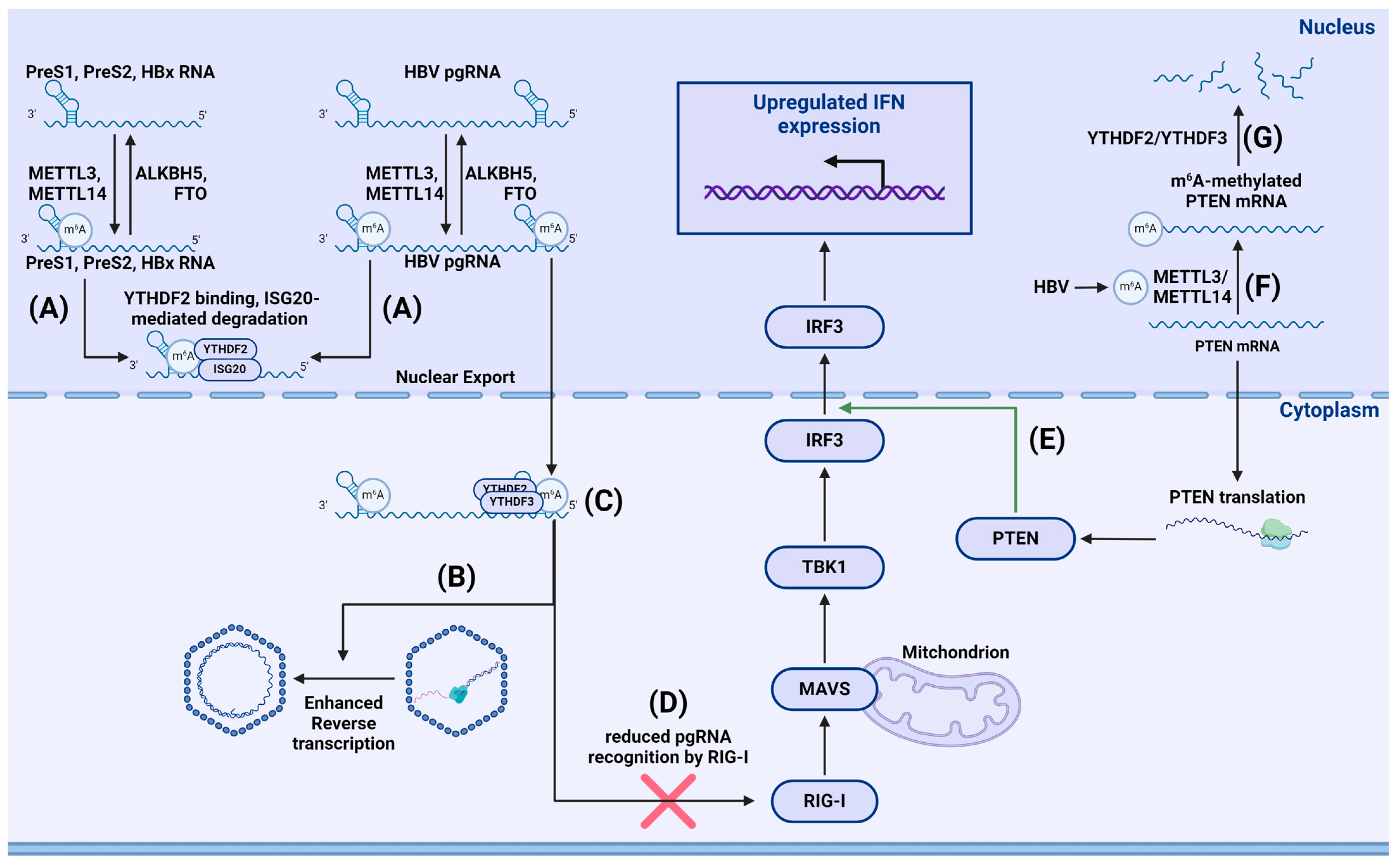

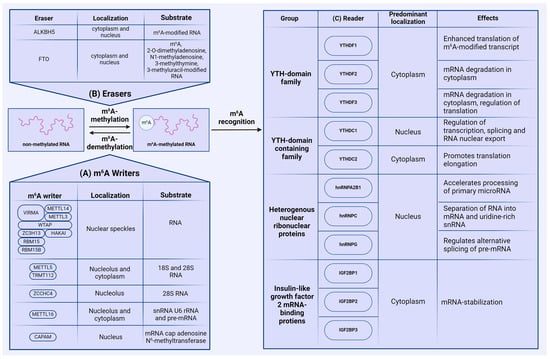

The m6A modification is dynamically reversible by three groups of enzymes: methyltransferases (writers), demethylases (erasers), and proteins that recognize m6A-modified RNA (readers). The reversibility of m6A methylation is controlled by writers and erasers, while reader proteins recognize the modified adenosines and regulate the associated biological functions (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mammalian m6A machinery. (A) RNA methylation is performed by groups of N6-methyltransferases (writers), with most of the m6A modification carried out by the methyltransferase complex, containing METTL3 and METTL14. (B) m6A demethylation is executed by demethylases (erasers) ALKBH5 and FTO. (C) m6A-methylated RNA is recognized by a plethora of reader proteins that play a crucial role in the fate of m6A-modified RNA.

2.1. Writers

So far, four main genes encoding methyltransferases have been identified in the human genome—methyltransferase-like (METTL) 3 (METTL3), METTL5, METTL16, and zinc finger CCHC-type containing 4 (ZCCHC4). In addition to these methyltransferases, other proteins participating in m6A catalysis perform collaborative functions, including METTL14, Wilms tumor 1-associating protein (WTAP), Vir-like m6A methyltransferase associated (VIRMA), Cbl proto-oncogene like 1 (HAKAI), zinc finger CCCH-type containing 13 (ZC3H13), and RNA-binding motif 15/15B (RBM15/15B). In most cases, m6A methylation is catalyzed by the methyltransferase complex (MTC) consisting of METTL3, METTL14, WTAP, RBM15/15B, ZC3H13, VIRMA, and HAKAI, which is typically localized in the nucleus, except for in certain cancer cell lines [17,18]. METTL3 directly adds m6A modifications onto RNA, and METTL14 stabilizes the conformation of METTL3’s catalytic center. METTL14 is also crucial for substrate recognition [19]. In addition, Liu et al. have also identified that both METTL14 and METTL3 individually exhibit methyltransferase activity; however, the activity of the METTL3–METTL14 complex is markedly higher [20]. The remaining proteins of this complex perform various specific functions: WTAP targets the METTL3–METTL14 complex to nuclear speckles [17,21], and RBM15/15B binds to the m6A complex and interacts with specific U-rich sites in XIST RNA. Data show that knockdown of both RBM15 and RBM15B results in impaired XIST-mediated gene silencing, suggesting that RBM15 and RBM15B are necessary for MTC recruitment to XSIT RNA. Additionally, WTAP is essential for facilitating the interaction between RBM15/RBM15B and the methylation complex [22]. ZC3H13 regulates MTC’s localization to the nucleus, as knocking down ZC3H13 results in cytoplasmic localization of METTL3, METTL14, VIRMA, WTAP, and HAKAI, the latter of which bridges WTAP to the mRNA-binding factor NITO [23]. VIRMA also plays a crucial role in preferential 3′-UTR m6A modification, but has no impact on long-exon-preferential methylation [24]. Studies on Drosophila melanogaster have shown that HAKAI is crucial for MTC stabilization, as its knockout results in decreased methylation activity. We were unable to find studies regarding the role of HAKAI in mammals, but HAKAI is considered to be conserved between humans and Drosophila [25].

Methylation of 18S and 28S rRNA, as well as small nuclear RNA (snRNA) U6, is carried out by the heterodimeric methyltransferase complex METTL5 and the stabilizing coactivator protein TRMT112 [26]. m6A modification of 28S rRNA is regulated by methyltransferase ZCCHC4. ZCCHC4 is localized in nucleoli, where it interacts with RNA-binding proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis and RNA metabolism [27]. The methyltransferase METTL16 is distributed to both the nucleus and the cytoplasm [28,29], and interacts with snRNA U6, rRNA, and pre-mRNA [30,31]. Notably, METTL16 can regulate the expression of MAT2A, which is directly responsible for the synthesis of S-adenosylmethionine [32].

In addition to the main methyltransferases, m6A modification can be added on mRNA cap-adjacent Am-modified nucleotides by cap-specific adenosine-N6-MTase (CAPAM). Using RNA-MS, Akichika S. et al., demonstrated that CAPAM catalyzes N6-methylation of m6Am in capped mRNA in an S-adenosylmethionine (SAM)-dependent manner. Additionally, CAPAM specifically recognizes the cap structure 7-methylguanosine (m7G) and N6-methylates m7GpppAm [33].

2.2. Erasers

Protein erasers act as demethylases, removing m6A modifications from RNA. Currently, only two demethylases from the FeII/α-KG-dependent dioxygenase AlkB family associated with m6A methylation have been described. The first demethylase, identified in 2011, is the fat mass- and obesity-associated protein (FTO) [34], which regulates processing and alternative splicing in adipocytes through m6A demethylation [35]. Mathiyalagan et al. discovered that FTO-dependent demethylation of m6A regulates intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and sarcomeres in cardiomyocytes [36]. FTO’s activity as an m6A methyltransferase is interrelated with lipid accumulation control in muscle, as this enzyme plays a regulatory role in activating AMP kinase (AMPK) [37]. Wu et al. demonstrated that suppressing FTO significantly reduces the expression of Cyclin A2 (CCNA2) and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (CDK2) genes, which play a key role in cell cycle regulation. This leads to the delayed transitioning of cells exposed to insulin into the G2 phase of the cell cycle. Moreover, the level of m6A methylation of CCNA2 and CDK2 mRNA is substantially increased upon FTO suppression [38].

Another demethylase is the related alpha-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), described in 2013 [10]. ALKBH5 primarily interacts with m6A in RNA and is most highly expressed in the testes and lungs. ALKBH5 is believed to regulate the assembly of mRNA processing factors [10]. Notably, m6A sites are the only substrates for ALKBH5, whereas FTO can erase other modifications like 2-O-dimethyladenosine, N1-methyladenosine, 3-methylthymine, and 3-methyluracil [39,40].

2.3. Readers

Reader proteins are the major factors that execute biological functions in m6A-modified RNA by recognizing and binding to methylated transcripts. Three major groups of reader proteins regulate m6A-mediated functions. The first group is proteins containing the conservative YT521-B homology (YTH) domain [41], which consists of approximately 150 amino acids distributed across three α-helices and six β-sheets [42]. In humans, five proteins with the YTH domain have been identified: three paralogs of the YTH domain family 1–3 (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3) and distinct proteins of the YTH domain containing 1–2 (YTHDC1 and YTHDC2). All of these proteins have structural differences. In particular, YTHDC1 contains the YTH domain surrounded by charged regions containing glutamic acid, arginine, or proline residues. YTHDC2 is the most complex protein in this group, containing not only the YTH domain, but also several helicase domains and two ankyrin repeats, possessing ATPase and 3′→5′-helicase activity [43]. The YTHDF family of proteins, together with the YTH domain, also consist of disordered regions enriched in proline, glutamine, and asparagine [42].

YTHDF1–3 and YTHDC2 mainly localize in the cytoplasm, while YTHDC1 is predominantly distributed in the nucleus. YTHDF1 enhances the translation of m6A-modified RNAs by a yet unclarified mechanism; YTHDF1 binds RNA near the stop codon and interacts with translation initiation factor complex 3, which is part of the translation initiation complex [12]. YTHDF2’s functions are primarily associated with mRNA degradation in the cytosol. It can activate the carbon catabolite repression 4-negative on the TATA-less (CCR4-NOT) deadenylase complex, involved in mRNA deadenylation and degradation [44], and the P/MRP ribonuclease complex, which initiates endoribonucleolytic cleavage of mRNA. YTHDF3 is the least studied of this group. Li et al. noted that YTHDF3 regulates translation by interacting with YTHDF1 and with the 40S and 60S ribosome subunits [45]. However, it has also been determined that YTHDF3, along with YTHDF2, can participate in degrading RNA [46]. YTHDC1 actively participates in the regulation of transcription, splicing, and RNA export from the nucleus [47], while YTHDC2 contributes to enhancing translation efficiency and mRNA degradation through its helicase activity [48].

The second group of readers includes several heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins (HNRNP): HNRNPC, HNRNPG, and HNRNPA2B1. HNRNPC selectively binds to unstructured RNA regions during pre-mRNA processing and separates transcripts into mRNA and uridine-rich snRNA [49]. HNRNPG binds to arginine-glycine-glycine (RGG) regions and regulates alternative splicing of pre-mRNA by interacting with the phosphorylated C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II [50]. HNRNPA2B1 accelerates the processing of primary microRNAs by interacting with the microprocessor complex subunit DGCR8 [51].

The third group of readers consists of three highly conserved insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BP): IGF2BP1, IGF2BP2, and IGF2BP3. At the N-terminus, IGF2BP proteins have two RNA recognition motifs (RRM); four hnRNP-K homology (KH) domains are located at the C-terminus [52]. KH domains are mainly responsible for protein–RNA binding. RRM domains regulate the stability of IGF2BP–RNA complexes [53]. The primary function of IGF2BP proteins is maintaining stability of target RNAs [54]. It is suggested that virtually any cellular protein can act as reader for m6A, enabling highly tunable and diverse control of RNA metabolism [55].

2.4. m6A Modifications and Viruses

m6A methylation has been shown to influence the life cycle of viruses by affecting viral replication and evasion of the innate immune response. To date, there is a large body of research focused on the role of m6A in regulating replication of viruses from many different families. For example, Lu W et al. demonstrated that m6A modification at two sites in the 5′ leader sequence of HIV-1 genomic RNA (gRNA) promotes viral replication. Mutations in these sites resulted in HIV-1 with lower infectivity compared to wild-type virus. Additionally, overexpression of m6A reader proteins YTHDF1-3 in target cells reduces the levels of HIV-1 gRNA, inhibiting early and late reverse transcription processes [56].

Ye et al., revealed that Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) can also manipulate the host m6A machinery to its own advantage by switching from latency to lytic infection. It was demonstrated that most transcripts of KSHV and their levels increase upon lytic infection. This effect was mediated by the interaction of m6A sites with YTHDC1 reader proteins in conjunction with two splicing factors: serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 3 (SRSF3) and SRSF10. Mutating m6A sites blocked splicing of pre-mRNA (RTA—replication transcription activator) that encodes a key KSHV protein, required for lytic infection. Therefore, m6A modification plays an important role in viral splicing [57]. Similarly, m6A modification accelerates replication of enterovirus 71 (EV71) due to complex interactions between m6A-modified viral RNA, m6A machinery, and RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 3D [58]. These and other effects of m6A modifications in viral RNA on viral life cycle are discussed in detail in the next chapters.

5. The Role of the m6A Modifications in the Genetic Material of Viruses

In addition to its involvement in cellular processes, the RNA modification has been shown to impact the regulation of the viral life cycle. There is substantial evidence that modifications other than m6A can affect the replication of various viruses such as 5-methylcytidine (m5C) [128], N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) [129], and 2′O-methylation of the ribose fragment of all four ribonucleosides (Nm), etc. [130]. However, m6A modifications are the most prevalent. The presence of m6A markers in viruses has been recognized for several decades, but its functional significance has been poorly understood until just recently. Initially identified in nuclear viral DNA, the role of m6A was later described for RNA viruses. Upon infection, writer and eraser proteins can translocate from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, where they regulate methylation of viral nucleic acids. Further investigation of m6A methylation in viruses is crucial for understanding how it influences the viral epitranscriptome and may provide insights for developing novel prognostic biomarkers and antiviral therapies.

5.1. Retroviruses

HIV-1, a representative of the Retroviridae family, is a positive ssRNA virus that replicates in the nucleus and is susceptible to m6A methylation. Tirumuru et al. demonstrated that METTL3 and METTL14 knockdown resulted in inhibited HIV-1 Gag protein expression. Conversely, knocking down ALKBH5 and FTO resulted in higher HIV protein expression; notably, FTO knockdown caused a significant increase in HIV protein expression. m6A modifications in the HIV-1 genome can interact with cellular YTHDF1–3 reader proteins. Partially knocking down YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 in Jurkat cells resulted in a three- to four-fold increase in HIV-1 infection, while only a slight increase was observed after YTHDF2 knockdown. Overexpressing each of the YTHDF1–3 proteins significantly reduced the level of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase products by four- to ten-fold. This downregulation of reverse transcription was attributed to mRNA degradation, mediated by YTHDF1–3 [131]. In contrast, in the study by Tsai et al., a three-fold increase was observed in the overall expression of HIV-1 viral RNA in cells with YTHDF2 protein overexpression 24 h after infection. The authors noted that YTHDF2 and another reader, YTHDC1, bind to m6A sites in HIV-1 transcripts. Knockdown of YTHDC1 increased viral Gag expression, while overexpressing YTHDC1 reduced viral RNA expression. Deep sequencing of splice forms demonstrated that YTHDC1 can regulate alternative splicing of HIV-1 transcripts [132]. Chen et al. assessed HIV content in cells with different levels of expression of FTO and ALKBH5 eraser proteins, finding that decreasing methylation levels enhanced binding to RIG-I [133].

5.2. Orthomyxoviruses

Influenza A virus (IAV) belongs to the Orthomyxoviridae family, characterized by negative-sense segmented RNA genomes that replicate in the host cell nucleus. Courtney et al. investigated how m6A affects the expression and replication of IAV genes. The authors demonstrated that METTL3 knockout and chemical inhibition of methylation using 3-deazaneplanocin A in A549 cells reduced IAV replication levels by suppressing viral mRNA and protein expression. The study also showed that increased regulation of the reader protein YTHDF2 significantly enhanced IAV replication and viral particle production. Additionally, the locations of m6A residues on viral mRNA were mapped using RNA–protein crosslinking and immunoprecipitation. These mapping data were confirmed by generating mutant forms of IAV, in which eight prominent m6A sites on the plus-strand mRNA/cRNA of hemagglutinin (HA) or nine m6A sites on the minus-strand vRNA of HA were mutated. In these IAV mutants, selectively lower levels of mRNA and HA protein were expressed, while the expression of other IAV mRNA and proteins remained unaffected [134]. Additionally, Zhu et al. identified the involvement of another reader protein, YTHDC1, which was found to be upregulated in IAV-infected cells. Using mass spectrometry and co-immunoprecipitation experiments, the authors showed that YTHDC1 interacts with the non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of IAV, thereby promoting viral replication. Mutations in NS1 (NS1 R38A and K41A) disrupted its ability to inhibit NS segment splicing and hindered its interaction with YTHDC1. Knockdown of YTHDC1 enhanced NS segment splicing, while restoring YTHDC1 reversed this effect. The study concluded that the interaction between NS1 and YTHDC1 plays a critical role in regulating NS mRNA splicing during IAV infection [11].

5.3. Flaviviruses

Flaviviruses are a group of viruses characterized by positive-sense ssRNA genomes that replicate in the cytoplasm. This viral family includes pathogens such as yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, dengue virus, tick-borne encephalitis virus, Zika virus (ZIKV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Lichinchi et al. observed that ZIKV can undergo m6A methylation mediated by host METTL3 and METTL14 as well as by ALKBH5 and FTO. m6A methylation was shown to negatively regulate ZIKV production. Knockdown of YTHDF1–3 readers increased viral RNA levels, while overexpressing YTHDF1-3 decreased levels of extracellular viral RNA [135]. Gokhale et al. conducted a comprehensive study mapping m6A modification sites in HCV, dengue virus, yellow fever virus, ZIKV, and West Nile virus. In addition to mapping, the authors investigated the role of m6A methylation in HCV and noted that depleting METTL3 and METTL14 increased the rate of HCV infection, promoting the formation of infectious viral particles without affecting viral RNA replication. Depleting the m6A demethylase FTO had the opposite effect. Additionally, YTHDF readers reduced the production of HCV particles and localized to viral assembly sites. All three YTHDF proteins bound to HCV RNA at the same sites, and their depletion increased the production of HCV particles [136]. The role of the YTHDC2 reader was established in the study by Kim and Siddiqui. Using cells with a knockout of the YTHDC2 helicase domain (YTHDC2-E332Q), they showed that the expression levels of HCV core protein were higher in cells transfected with wild-type YTHDC2 but significantly lower in cells transfected with YTHDC2-E332Q. Additionally, in the same study, the authors noted that suppressing METTL3 and METTL14 increased the stability of HCV RNA [137]. In experiments with HBV and HCV, Kim et al. showed that METTL3/METTL14 depletion led to increased viral RNA recognition by RIG-I with subsequent increases in IFN1 production. Furthermore, RNA binding by YTHDF2 and YTHDF3 was found to be the reason for decreased RIG-I sensing [138]. The mechanism behind the evasion of the RIG-I-mediated antiviral response through m6A methylation and mimicry of cellular RNAs has been identified in representatives of the Pneumoviridae, Paramyxoviridae, and Rhabdoviridae viral families [139,140].

Gokhale et al. found negative regulation of HCV viral particle production by METTL3/METTL14 methyltransferases and YTHDF1, YTHDF2, and YTHDF3 readers. Additionally, FTO demethylase positively regulated HCV particle production, while ALKBH5 levels did not affect viral particle production [136]. Further, m6A methylation of HCV RNA was shown to downregulate viral particle production and reduce the efficiency of RIG-I-mediated viral RNA sensing.

5.4. Coronaviruses

SARS-CoV-2, a β-coronavirus with positive-sense ssRNA, contains eight m6A modifications in its genome, as shown via m6A-seq and miCLIP analysis conducted by Liu et al. The authors also demonstrated that m6A RNA methylation negatively regulates the life cycle of SARS-CoV-2. In Huh7 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2, abundant METTL14 and ALKBH5 relocated to the cytoplasm, where coronavirus genomic RNA replication occurs. Virus replication and the percentage of SARS-CoV-2-positive cells significantly increased after METTL3 and METTL14 knockdown. Knocking down YTHDF2, but not YTHDF1 or YTHDF3, promoted viral infection and replication. SARS-CoV-2 can influence host cell m6A methylation, as the overall intensity of m6A significantly increased in Huh7 cells infected with SARS-CoV-2 compared to uninfected Huh7 cells [141]. Burgess et al. demonstrated that METTL3, YTHDF1, and YTHDF3 are necessary for the replication of human β-coronaviruses. The catalytic function of METTL3 plays a crucial role in the efficient synthesis of viral RNA within the first 24 h post infection, leading to subsequent accumulation of viral proteins [142]. Liu et al. conducted a systematic analysis of m6A in different strains of SARS-CoV-2 causing mild or severe forms of COVID-19, and concluded that the presence of more m6A modifications in the N region of SARS-CoV-2 correlated with weaker pathogenicity. The authors described several methylation sites that may be associated with viral pathogenicity, such as site 74 located in the transcription regulatory sequence of the 5′-UTR of SARS-CoV-2, and a similar site, 29 707, in the 3′-UTR [143].

5.5. Hepadnaviruses

HBV is a hepatotropic DNA virus from Hepadnaviridae family, characterized by a complex life cycle involving a stage of reverse transcription. Imam et al. used m6A-seq analysis to identify m6A methylation sites within a conserved motif located in the epsilon stem loop at the 3′ end of all HBV mRNA, as well as at the 5′ and 3′ ends of pregenomic RNA (pgRNA). Their results showed that m6A methylation in the 5′-epsilon stem loop of pgRNA was necessary for pgRNA reverse transcription, while m6A methylation in the 3′-epsilon stem loop of pgRNA destabilized all HBV transcripts [144]. Moreover, m6A RNA modification of HBV is necessary for efficient replication of the virus in hepatocytes. As shown by Murata et al., m6A modifications primarily occur in the coding region of HBx, and mutating m6A sites decreased HBV and HBs RNA levels. The authors also assessed the impact of the m6A methylation inhibitor cycloleucine on HBV. Cycloleucine reduced HBV RNA levels in cells and HBs levels in a dose-dependent manner, while 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) analysis showed that cell viability was unaffected. METTL3 knockdown also reduced HBV and HBs RNA levels, indicating the crucial role of m6A in the HBV life cycle [145]. Kim et al. found that m6A methylation of HBV transcripts regulates their intracellular distribution. Transcripts of HBV in cells transfected with m6A mutant plasmids predominantly accumulated in the nucleus compared to wild-type cells. The authors also noted that knocking out YTHDC1 and fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP) affected the nuclear export of m6A-modified HBV transcripts. MeRIP analysis showed that most m6A-modified viral RNAs located to the cytoplasm, but when cells are depleted of YTHDC1 or FMRP, m6A-methylated viral RNAs accumulated in the nucleus [146].

Studies by Imam et al. demonstrated that depleting METTL3 and METTL14 resulted in increased expression of HBV HBs and HBc proteins. Similarly, depleting FTO and ALKBH5 demethylases decreased expression of said proteins, suggesting that m6A methylation downregulates HBV protein expression. Notably, depleting YTHDF2 and YTHDF3 also resulted in increased expression of HBs and HBc proteins. Further investigations uncovered a more than two-fold increase in pgRNA stability in cells depleted of either YTHDF2 or METTL3/METTL14; this was ruled to be due to reduced stability of m6A-modified HBV RNA. This effect might be due to YTHDF2-mediated RNA degradation. The role of m6A methylation in the interaction between HBV and cells is further discussed by Kostyusheva et al. [147].

Zhang et al. conducted a bioinformatics analysis of m6A regulators associated with immune infiltration in HBV-related HCC. The authors demonstrated that m6A influences oncogenesis, tumor microenvironment, and patient prognosis in HBV-related HCC [148].

5.6. Adenoviruses

Adenoviruses (AdV), dsDNA viruses, undergo replication in the nucleus utilizing cellular RNA polymerase II. It was demonstrated that methyltransferases METTL3, METTL14, and WTAP, and the reader protein YTHDC1, translocate to sites of viral RNA biosynthesis in A549 cells infected with AdV5 within 18 h of infection, suggesting that m6A modification may play a role in regulating late viral RNA splicing efficiency. Knockout of METTL3 or WTAP did not affect the splicing efficiency of the E1A gene, expressed during early infection stages, but significantly reduced splicing efficiency of the fiber gene, expressed later. Similar changes were observed in cells lacking YTHDC1, albeit to a lesser extent [149]. Hajikhezri et al. noted that the absence of FXR1 reduced the accumulation of viral capsid protein during human AdV-5 infection in cell culture. The authors found that the FXR1 protein accumulates at a late stage of human AdV-5 infection and forms distinct subcellular condensates. CLIP-qPCR revealed that the endogenous FXR1 protein binds to m6A-modified viral capsid mRNA [150].

5.7. Herpesviruses

Transcripts of the HSV-1 genome can contain 12 sites of m6A methylation. Feng et al. noted that the expression of methyltransferases METTL3 and METTL14 and readers YTHDF1–3 increased in the early stages of HSV-1 infection and decreased in the later stages; the expression of demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 was reduced [151]. Hesser and Walsh also observed that the infection time of HSV1 suppresses YTHDF proteins [112]. Jansens et al. found that suppressing m6A-methylated HSV transcripts depended on the YTHDF reader protein family and correlated with the localization of these proteins to enlarged P-bodies [152]. Wang et al. identified that METTL3 is aberrantly expressed in mouse corneal endothelial cells and human umbilical vein endothelial cells infected with HSV1. HSV-1 infection may lead to increased levels of m6A in endothelial cells, but this does not always correlate with METTL3 levels [153]. Xu et al. demonstrated that the level of m6A RNA modification changed after infection of oral epithelial cells with HSV-1, likely regulated by changes in the expression of demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 [154].

6. Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite RNA methylation being described over forty years ago, the expanding significance of epitranscriptomic markers is still to be understood. m6A methylation is the most common and well-studied of these markers, but its role in virology was practically unstudied until recently. Now, viral epitranscriptomics has actively started to develop. Increasing attention is given to the role of m6A in regulating the reverse transcription and translation of viral genetic material, as well as the mechanisms of viral evasion of the host organism’s immune system. m6A modifications can determine the strength and duration of the activation of the innate immune response. Studying the impact of m6A methylation on innate antiviral immunity, viral life cycles, and the ability of viruses to mask and evade sensor cells holds numerous perspectives and practical applications.

Investigating how m6A methylation can influence the expression of genes involved in the innate immune response may provide a comprehensive answer to how m6A modifications regulate the transcription and translation of key genes associated with immunity.

Understanding the role of m6A modifications in the recognition of viral RNA by PRRs and the subsequent activation or inhibition of antiviral pathways warrants further investigation. Some factors recognizing viral DNA may be present not only in the cytosol but also in the nucleus [85]. This raises additional questions: how can proteins associated with innate immunity differentiate between host and viral DNA, and what role does m6A play in these processes?

Studying the functions of proteins linked to m6A methylation is also crucial. Since m6A is a dynamic regulation, understanding the role of the proteins regulating these modifications can provide an overall insight into the regulation of m6A modification during immune reactions and, consequently, the dynamism of immune responses.

Recently, the role of lncRNAs in the organization of intracellular immunity was actively investigated [155]. Exploring the influence of m6A methylation on lncRNAs associated with innate immunity will allow understanding of how m6A modifications in lncRNAs can affect their stability, localization, and interactions with other cellular components.

m6A is not the only modification to play a role in the organization of intercellular immunity [118]. Researching the interaction between m6A methylation and other epigenetic modifications in the context of innate immunity, such as how m6A interacts with DNA methylation, histone modifications, and other RNA modifications during the formation of immune responses, will establish additional mechanisms for regulating antiviral immune reactions.

An important direction is exploring the potential impact of m6A regulators as a therapeutic strategy for activating innate immune responses. Understanding regulatory mechanisms could open opportunities for developing interventions aimed at enhancing or suppressing immune reactions in various viral diseases. Studying how disrupting regulation of m6A modifications is linked to impairments in signaling pathways of antiviral immunity will help identify new diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets.

Investigating the involvement of m6A methylation in the innate immune response holds great prospects for further research into host–pathogen interactions and immune regulation. Studying m6A methylation’s role may have broad implications for the development of therapeutic agents related to modulating immune responses and treating viral diseases.

Recent studies have highlighted the potential of specific RNA modifications as valuable diagnostic and prognostic indicators in viral infections. For instance, Nagayoshi Y et al. reported an elevation in the levels of RNA modifications, including N1-methyladenosine (m1A), N2,N2-dimethylguanosine (m22G), N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A), 2-methylthio-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (ms2t6A), N6-methyl-N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (m6t6A), and N6,2′-O-dimethyladenosine (m6Am), following SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The abundance of RNA modifications, specifically t6A and ms2t6A, exhibited a notable increase exceeding four-fold levels in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Through liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis of biological samples, the researchers proposed the potential utility of m6t6A and t6A as diagnostic biomarkers for COVID-19. Furthermore, the study demonstrated a positive correlation between the severity of COVID-19 and elevated levels of serum ms2t6A, suggesting the prognostic value of this RNA modification as a predictive marker for coronavirus infection [156].

Despite the abundance of data on the involvement of m6A in viral infections and other infectious diseases, there is a lack of comprehensive studies regarding their prognostic significance in terms of disease progression or therapeutic decision-making. In contrast, m6A has received considerable attention as a prognostic biomarker in oncology and other medical fields, facilitating the selection of optimal therapeutics, evaluation of disease progression risks, assessment of remission duration, and prediction of relapse risks.Additional investigation is warranted to advance the development of potential m6A-based prognostic biomarkers for infectious diseases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.K., A.K. (Artyom Kachanov), A.K. (Anastasiya Kostyusheva) and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.K., A.K. (Artyom Kachanov), M.D., N.P., S.B., A.K. (Anastasiya Kostyusheva), V.C. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, I.K., A.K. (Artyom Kachanov), A.L., S.B., V.S.P., V.C. and D.K.; visualization, I.K., A.K. (Artyom Kachanov), A.K. (Anastasiya Kostyusheva) and D.K.; supervision, A.K. (Anastasiya Kostyusheva) and D.K.; project administration, V.C., D.K.; funding acquisition, A.K. (Anastasiya Kostyusheva). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Desrosiers, R.; Friderici, K.; Rottman, F. Identification of methylated nucleosides in messenger RNA from Novikoff hepatoma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1974, 71, 3971–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccaletto, P.; Machnicka, M.A.; Purta, E.; Piątkowski, P.; Baginski, B.; Wirecki, T.K.; De Crécy-Lagard, V.; Ross, R.; Limbach, P.A.; Kotter, A.; et al. MODOMICS: A database of RNA modification pathways. 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, D303–D307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beemon, K.; Keith, J. Localization of N6-methyladenosine in the Rous sarcoma virus genome. J. Mol. Biol. 1977, 113, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaccara, S.; Ries, R.J.; Jaffrey, S.R. Reading, writing and erasing mRNA methylation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2019, 20, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maden, B. Identification of the locations of the methyl groups in 18 S ribosomal RNA from Xenopus laevis and man. J. Mol. Biol. 1986, 189, 681–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berulava, T.; Rahmann, S.; Rademacher, K.; Klein-Hitpass, L.; Horsthemke, B. N6-adenosine methylation in MiRNAs. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Pandya-Jones, A.; Saito, Y.; Fak, J.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Geula, S.; Hanna, J.H.; Black, D.L.; Darnell, J.E.; Darnell, R.B. m(6)A mRNA modifications are deposited in nascent pre-mRNA and are not required for splicing but do specify cytoplasmic turnover. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 990–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominissini, D.; Moshitch-Moshkovitz, S.; Schwartz, S.; Salmon-Divon, M.; Ungar, L.; Osenberg, S.; Cesarkas, K.; Jacob-Hirsch, J.; Amariglio, N.; Kupiec, M.; et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature 2012, 485, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Gomez, A.; Hon, G.C.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Fu, Y.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Jia, G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine-dependent regulation of messenger RNA stability. Nature 2014, 505, 117–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Dahl, J.A.; Niu, Y.; Fedorcsak, P.; Huang, C.-M.; Li, C.J.; Vågbø, C.B.; Shi, Y.; Wang, W.-L.; Song, S.-H.; et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol. Cell 2013, 49, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, R.; Zou, J.; Tian, S.; Yu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Ran, Y.; Jin, M.; Chen, H.; Zhou, H. N6-methyladenosine reader protein YTHDC1 regulates influenza A virus NS segment splicing and replication. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, B.S.; Roundtree, I.A.; Lu, Z.; Han, D.; Ma, H.; Weng, X.; Chen, K.; Shi, H.; He, C. N(6)-methyladenosine Modulates Messenger RNA Translation Efficiency. Cell 2015, 161, 1388–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavi, S.; Shatkin, A.J. Methylated simian virus 40-specific RNA from nuclei and cytoplasm of infected BSC-1 cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 2012–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, M.J.; McIntyre, A.B.; Mourelatos, H.; Abell, N.S.; Gokhale, N.S.; Ipas, H.; Xhemalçe, B.; Mason, C.E.; Horner, S.M. Post-transcriptional regulation of antiviral gene expression by N6-methyladenosine. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, M.J.; Horner, S.M. N(6)-Methyladenosine Regulates Host Responses to Viral Infection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2021, 46, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, M.; Zhao, B.S.; Harder, O.; Li, A.; Liang, X.; Gao, T.Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, J.; et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modification enables viral RNA to escape recognition by RNA sensor RIG-I. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 584–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schöller, E.; Weichmann, F.; Treiber, T.; Ringle, S.; Treiber, N.; Flatley, A.; Feederle, R.; Bruckmann, A.; Meister, G. Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the m(6)A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA 2018, 24, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choe, J.; Lin, S.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Ramirez-Moya, J.; Du, P.; Kim, W.; Tang, S.; Sliz, P.; et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature 2018, 561, 556–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Doxtader, K.A.; Nam, Y. Structural Basis for Cooperative Function of Mettl3 and Mettl14 Methyltransferases. Mol. Cell 2016, 63, 306–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yue, Y.; Han, D.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Jia, G.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Deng, X.; et al. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, X.-L.; Sun, B.-F.; Wang, L.; Xiao, W.; Yang, X.; Wang, W.-J.; Adhikari, S.; Shi, Y.; Lv, Y.; Chen, Y.-S.; et al. Mammalian WTAP is a regulatory subunit of the RNA N6-methyladenosine methyltransferase. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, D.P.; Chen, C.-K.; Pickering, B.F.; Chow, A.; Jackson, C.; Guttman, M.; Jaffrey, S.R. m(6)A RNA methylation promotes XIST-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature 2016, 537, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Lv, R.; Ma, H.; Shen, H.; He, C.; Wang, J.; Jiao, F.; Liu, H.; Yang, P.; Tan, L.; et al. Zc3h13 Regulates Nuclear RNA m(6)A Methylation and Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell Self-Renewal. Mol. Cell 2018, 69, 1028–1038.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; Cui, X.; Cao, J.; Luo, G.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, T.; Gao, M.; Shu, X.; Ma, H.; et al. VIRMA mediates preferential m(6)A mRNA methylation in 3′UTR and near stop codon and associates with alternative polyadenylation. Cell Discov. 2018, 4, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawankar, P.; Lence, T.; Paolantoni, C.; Haussmann, I.U.; Kazlauskiene, M.; Jacob, D.; Heidelberger, J.B.; Richter, F.M.; Nallasivan, M.P.; Morin, V.; et al. Hakai is required for stabilization of core components of the m(6)A mRNA methylation machinery. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkalj, E.M.; Vissers, C. The emerging importance of METTL5-mediated ribosomal RNA methylation. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 1617–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R.; Vågbø, C.B.; Jakobsson, M.E.; Kim, Y.; Baltissen, M.P.; O’donohue, M.-F.; Guzmán, U.H.; Małecki, J.M.; Wu, J.; Kirpekar, F.; et al. The human methyltransferase ZCCHC4 catalyses N6-methyladenosine modification of 28S ribosomal RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, 830–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Kinzig, C.G.; DeGregorio, S.J.; Steitz, J.A. Methyltransferase-like protein 16 binds the 3′-terminal triple helix of MALAT1 long noncoding RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14013–14018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nance, D.J.; Satterwhite, E.R.; Bhaskar, B.; Misra, S.; Carraway, K.R.; Mansfield, K.D. Characterization of METTL16 as a cytoplasmic RNA binding protein. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warda, A.S.; Kretschmer, J.; Hackert, P.; Lenz, C.; Urlaub, H.; Höbartner, C.; Sloan, K.E.; Bohnsack, M.T. Human METTL16 is a N(6)-methyladenosine (m(6)A) methyltransferase that targets pre-mRNAs and various non-coding RNAs. EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 2004–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, R.; Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Gao, M.; He, P.C.; Liu, W.; Wei, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, L.; Han, L.; et al. METTL16 exerts an m(6)A-independent function to facilitate translation and tumorigenesis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2022, 24, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pendleton, K.E.; Chen, B.; Liu, K.; Hunter, O.V.; Xie, Y.; Tu, B.P.; Conrad, N.K. The U6 snRNA m(6)A Methyltransferase METTL16 Regulates SAM Synthetase Intron Retention. Cell 2017, 169, 824–835.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akichika, S.; Hirano, S.; Shichino, Y.; Suzuki, T.; Nishimasu, H.; Ishitani, R.; Sugita, A.; Hirose, Y.; Iwasaki, S.; Nureki, O.; et al. Cap-specific terminal N (6)-methylation of RNA by an RNA polymerase II-associated methyltransferase. Science 2019, 363, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, G.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Dai, Q.; Zheng, G.; Yang, Y.; Yi, C.; Lindahl, T.; Pan, T.; Yang, Y.-G.; et al. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011, 7, 885–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Sun, B.-F.; Shi, Y.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Hao, Y.-J.; Ping, X.-L.; Chen, Y.-S.; Wang, W.-J.; et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. 2014, 24, 1403–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyalagan, P.; Adamiak, M.; Mayourian, J.; Sassi, Y.; Liang, Y.; Agarwal, N.; Jha, D.; Zhang, S.; Kohlbrenner, E.; Chepurko, E.; et al. FTO-Dependent N(6)-Methyladenosine Regulates Cardiac Function During Remodeling and Repair. Circulation 2019, 139, 518–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Feng, J.; Jiang, D.; Zhou, X.; Jiang, Q.; Cai, M.; Wang, X.; Shan, T.; Wang, Y. AMPK regulates lipid accumulation in skeletal muscle cells through FTO-dependent demethylation of N(6)-methyladenosine. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Liu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Liu, Q.; Cai, M.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; et al. FTO regulates adipogenesis by controlling cell cycle progression via m(6)A-YTHDF2 dependent mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2018, 1863, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Liu, F.; Lu, Z.; Fei, Q.; Ai, Y.; He, P.C.; Shi, H.; Cui, X.; Su, R.; Klungland, A.; et al. Differential m(6)A, m(6)A(m), and m(1)A Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 973–985.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.; Yang, C.-G.; Yang, S.; Jian, X.; Yi, C.; Zhou, Z.; He, C. Oxidative demethylation of 3-methylthymine and 3-methyluracil in single-stranded DNA and RNA by mouse and human FTO. FEBS Lett. 2008, 582, 3313–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoilov, P.; Rafalska, I.; Stamm, S. YTH: A new domain in nuclear proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2002, 27, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Roundtree, I.A.; Tempel, W.; Li, Y.; Lu, Z.; He, C.; Min, J. Structural basis for selective binding of m 6 A RNA by the YTHDC1 YTH domain. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 927–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojtas, M.N.; Pandey, R.R.; Mendel, M.; Homolka, D.; Sachidanandam, R.; Pillai, R.S. Regulation of m(6)A Transcripts by the 3′→5′ RNA Helicase YTHDC2 Is Essential for a Successful Meiotic Program in the Mammalian Germline. Mol. Cell 2017, 68, 374–387.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; He, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, H.; Liu, M.; Ma, J.; Wu, L. YTHDF2 destabilizes m(6)A-containing RNA through direct recruitment of the CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Chen, Y.-S.; Ping, X.-L.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W.; Yang, Y.; Sun, H.-Y.; Zhu, Q.; Baidya, P.; Wang, X.; et al. Cytoplasmic m(6)A reader YTHDF3 promotes mRNA translation. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 444–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, H.; Wang, X.; Lu, Z.; Zhao, B.S.; Ma, H.; Hsu, P.J.; Liu, C.; He, C. YTHDF3 facilitates translation and decay of N(6)-methyladenosine-modified RNA. Cell Res. 2017, 27, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roundtree, I.A.; Luo, G.-Z.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, T.; Cui, Y.; Sha, J.; Huang, X.; Guerrero, L.; Xie, P.; et al. YTHDC1 mediates nuclear export of N(6)-methyladenosine methylated mRNAs. Elife 2017, 6, e31311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Dong, L.; Liu, X.-M.; Guo, J.; Ma, H.; Shen, B.; Qian, S.-B. m(6)A in mRNA coding regions promotes translation via the RNA helicase-containing YTHDC2. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCloskey, A.; Taniguchi, I.; Shinmyozu, K.; Ohno, M. hnRNP C tetramer measures RNA length to classify RNA polymerase II transcripts for export. Science 2012, 335, 1643–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Zhou, K.I.; Parisien, M.; Dai, Q.; Diatchenko, L.; Pan, T. N6-methyladenosine alters RNA structure to regulate binding of a low-complexity protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 6051–6063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, C.R.; Goodarzi, H.; Lee, H.; Liu, X.; Tavazoie, S.; Tavazoie, S.F. HNRNPA2B1 Is a Mediator of m(6)A-Dependent Nuclear RNA Processing Events. Cell 2015, 162, 1299–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, J.L.; Wächter, K.; Mühleck, B.; Pazaitis, N.; Köhn, M.; Lederer, M.; Hüttelmaier, S. Insulin-like growth factor 2 mRNA-binding proteins (IGF2BPs): Post-transcriptional drivers of cancer progression? Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2013, 70, 2657–2675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Hung, L.-H.; Aziz, M.; Wilmen, A.; Thaum, S.; Wagner, J.; Janowski, R.; Müller, S.; Schreiner, S.; Friedhoff, P.; et al. Combinatorial recognition of clustered RNA elements by the multidomain RNA-binding protein IMP3. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N(6)-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manners, O.; Baquero-Perez, B.; Whitehouse, A. m6A: Widespread regulatory control in virus replication. Biochim. Biophys Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 2019, 1862, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.; Tirumuru, N.; St. Gelais, C.; Koneru, P.C.; Liu, C.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; He, C.; Wu, L. N(6)-Methyladenosine-binding proteins suppress HIV-1 infectivity and viral production. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 12992–13005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Chen, E.R.; Nilsen, T.W. Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Utilizes and Manipulates RNA N(6)-Adenosine Methylation To Promote Lytic Replication. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10-1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, H.; Hao, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, B.; Qiu, J.; Deng, F.; et al. N6-methyladenosine modification and METTL3 modulate enterovirus 71 replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walsh, D.; McCarthy, J.; O’driscoll, C.; Melgar, S. Pattern recognition receptors--molecular orchestrators of inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013, 24, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eletto, D.; Mentucci, F.; Voli, A.; Petrella, A.; Porta, A.; Tosco, A. Helicobacter pylori Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns: Friends or Foes? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roh, J.S.; Sohn, D.H. Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns in Inflammatory Diseases. Immune Netw. 2018, 18, e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehwinkel, J.; Gack, M.U. RIG-I-like receptors: Their regulation and roles in RNA sensing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lind, N.A.; Rael, V.E.; Pestal, K.; Liu, B.; Barton, G.M. Regulation of the nucleic acid-sensing Toll-like receptors. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 22, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS-STING pathway as a therapeutic target in inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 548–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFadden, M.J.; Gokhale, N.S.; Horner, S.M. Protect this house: Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 22, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dempsey, A.; Bowie, A.G. Innate immune recognition of DNA: A recent history. Virology 2015, 479–480, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoneyama, M.; Kikuchi, M.; Yonehara, S.; Kato, A.; Fujita, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Imaizumi, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Taira, K.; Foy, E.; et al. Shared and unique functions of the DExD/H-box helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in antiviral innate immunity. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 2851–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Kohlway, A.; Pyle, A.M. Duplex RNA activated ATPases (DRAs): Platforms for RNA sensing, signaling and processing. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goubau, D.; Schlee, M.; Deddouche, S.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Zillinger, T.; Goldeck, M.; Schuberth, C.; Van der Veen, A.G.; Fujimura, T.; Rehwinkel, J.; et al. Antiviral immunity via RIG-I-mediated recognition of RNA bearing 5′-diphosphates. Nature 2014, 514, 372–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Hato, S.V.; Langereis, M.A.; Zoll, J.; Virgen-Slane, R.; Peisley, A.; Hur, S.; Semler, B.L.; van Rij, R.P.; van Kuppeveld, F.J. MDA5 detects the double-stranded RNA replicative form in picornavirus-infected cells. Cell Rep. 2012, 2, 1187–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, L.; Xu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Lian, Z.; Liu, P.; Li, X. LGP2 Promotes Type I Interferon Production To Inhibit PRRSV Infection via Enhancing MDA5-Mediated Signaling. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0184322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisien, J.; Lenoir, J.J.; Mandhana, R.; Rodriguez, K.R.; Qian, K.; Bruns, A.M.; Horvath, C.M. RNA sensor LGP2 inhibits TRAF ubiquitin ligase to negatively regulate innate immune signaling. EMBO Rep. 2018, 19, e45176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Kohlway, A.; Vela, A.; Pyle, A.M. Visualizing the determinants of viral RNA recognition by innate immune sensor RIG-I. Structure 2012, 20, 1983–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civril, F.; Bennett, M.; Moldt, M.; Deimling, T.; Witte, G.; Schiesser, S.; Carell, T.; Hopfner, K. The RIG-I ATPase domain structure reveals insights into ATP-dependent antiviral signalling. EMBO Rep. 2011, 12, 1127–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Sun, L.; Zheng, H.; Skaug, B.; Jiang, Q.-X.; Chen, Z.J. MAVS forms functional prion-like aggregates to activate and propagate antiviral innate immune response. Cell 2011, 146, 448–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, R.B.; Sun, L.; Ea, C.-K.; Chen, Z.J. Identification and characterization of MAVS, a mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein that activates NF-kappaB and IRF 3. Cell 2005, 122, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, E.; Boulant, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lee, A.S.; Odendall, C.; Shum, B.; Hacohen, N.; Chen, Z.J.; Whelan, S.P.; Fransen, M.; et al. Peroxisomes are signaling platforms for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 2010, 141, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabeta, K.; Hoebe, K.; Janssen, E.M.; Du, X.; Georgel, P.; Crozat, K.; Mudd, S.; Mann, N.; Sovath, S.; Goode, J.; et al. The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. Nat. Immunol. 2006, 7, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botos, I.; Segal, D.M.; Davies, D.R. The structural biology of Toll-like receptors. Structure 2011, 19, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Akira, S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: Update on Toll-like receptors. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 373–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.-C.; Chathuranga, K.; Lee, J.-S. Intracellular sensing of viral genomes and viral evasion. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP synthase is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates the type I interferon pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ablasser, A.; Goldeck, M.; Cavlar, T.; Deimling, T.; Witte, G.; Röhl, I.; Hopfner, K.-P.; Ludwig, J.; Hornung, V. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature 2013, 498, 380–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Oste, V.; Gatti, D.; Giorgio, A.G.; Gariglio, M.; Landolfo, S.; De Andrea, M. The interferon-inducible DNA-sensor protein IFI16: A key player in the antiviral response. New Microbiol. 2015, 38, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hornung, V.; Ablasser, A.; Charrel-Dennis, M.; Bauernfeind, F.; Horvath, G.; Caffrey, D.R.; Latz, E.; Fitzgerald, K.A. AIM2 recognizes cytosolic dsDNA and forms a caspase-1-activating inflammasome with ASC. Nature 2009, 458, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, B.; Bao, M.; Lu, N.; Kim, T.; Liu, Y.-J. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nat. Immunol. 2011, 12, 959–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.-H.; MacMillan, J.B.; Chen, Z.J. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell 2009, 138, 576–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalet, A.; Gatti, E.; Pierre, P. Integration of PKR-dependent translation inhibition with innate immunity is required for a coordinated anti-viral response. FEBS Lett. 2015, 589, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornung, V.; Hartmann, R.; Ablasser, A.; Hopfner, K.-P. OAS proteins and cGAS: Unifying concepts in sensing and responding to cytosolic nucleic acids. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014, 14, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.; Yi, G.; Watts, T.; Kao, C.C.; Li, P. Structure of STING bound to cyclic di-GMP reveals the mechanism of cyclic dinucleotide recognition by the immune system. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2012, 19, 722–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Z.J.; Bai, X.-C.; Zhang, X. Cryo-EM structures of STING reveal its mechanism of activation by cyclic GMP-AMP. Nature 2019, 567, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Shang, G.; Gui, X.; Zhang, X.; Bai, X.-C.; Chen, Z.J. Structural basis of STING binding with and phosphorylation by TBK1. Nature 2019, 567, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Cai, X.; Wu, J.; Cong, Q.; Chen, X.; Li, T.; Du, F.; Ren, J.; Wu, Y.-T.; Grishin, N.V.; et al. Phosphorylation of innate immune adaptor proteins MAVS, STING, and TRIF induces IRF3 activation. Science 2015, 347, aaa2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lester, S.N.; Li, K. Toll-like receptors in antiviral innate immunity. J. Mol. Biol. 2014, 426, 1246–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, K.; Shibata, T.; Fukui, R.; Sato, R.; Saitoh, S.-I.; Murakami, Y. Nucleic Acid Sensing by Toll-Like Receptors in the Endosomal Compartment. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 941931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Ghosh, A.; Kumar, B.; Chandran, B. IFI16, a nuclear innate immune DNA sensor, mediates epigenetic silencing of herpesvirus genomes by its association with H3K9 methyltransferases SUV39H1 and GLP. Elife 2019, 8, 49500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzalli, M.H.; Broekema, N.M.; Diner, B.A.; Hancks, D.C.; Elde, N.C.; Cristea, I.M.; Knipe, D.M. cGAS-mediated stabilization of IFI16 promotes innate signaling during herpes simplex virus infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E1773–E1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wen, M.; Cao, X. Nuclear hnRNPA2B1 initiates and amplifies the innate immune response to DNA viruses. Science 2019, 365, eaav0758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, S.; Aiello, D.; Atianand, M.K.; Ricci, E.P.; Gandhi, P.; Hall, L.L.; Byron, M.; Monks, B.; Henry-Bezy, M.; Lawrence, J.B.; et al. A long noncoding RNA mediates both activation and repression of immune response genes. Science 2013, 341, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentili, M.; Lahaye, X.; Nadalin, F.; Nader, G.P.; Lombardi, E.P.; Herve, S.; De Silva, N.S.; Rookhuizen, D.C.; Zueva, E.; Goudot, C.; et al. The N-Terminal Domain of cGAS Determines Preferential Association with Centromeric DNA and Innate Immune Activation in the Nucleus. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 2377–2393.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, S.; Yu, Q.; Chu, L.; Cui, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, C. Nuclear cGAS Functions Non-canonically to Enhance Antiviral Immunity via Recruiting Methyltransferase Prmt5. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justice, J.L.; Kennedy, M.A.; Hutton, J.E.; Liu, D.; Song, B.; Phelan, B.; Cristea, I.M. Systematic profiling of protein complex dynamics reveals DNA-PK phosphorylation of IFI16 en route to herpesvirus immunity. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, 6680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkl, P.E.; Knipe, D.M. Role for a Filamentous Nuclear Assembly of IFI16, DNA, and Host Factors in Restriction of Herpesviral Infection. MBio 2019, 10, e02621-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunphy, G.; Flannery, S.M.; Almine, J.F.; Connolly, D.J.; Paulus, C.; Jønsson, K.L.; Jakobsen, M.R.; Nevels, M.M.; Bowie, A.G.; Unterholzner, L. Non-canonical Activation of the DNA Sensing Adaptor STING by ATM and IFI16 Mediates NF-κB Signaling after Nuclear DNA Damage. Mol. Cell 2018, 71, 745–760.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, M.S.; Cristea, I.M. Human Antiviral Protein IFIX Suppresses Viral Gene Expression during Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1) Infection and Is Counteracted by Virus-induced Proteasomal Degradation. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2017, 16, S200–S214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, L.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Yang, G.; Luo, Y.; Li, S.; Du, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, J.; et al. The Nuclear Matrix Protein SAFA Surveils Viral RNA and Facilitates Immunity by Activating Antiviral Enhancers and Super-enhancers. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 369–384.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lahaye, X.; Gentili, M.; Silvin, A.; Conrad, C.; Picard, L.; Jouve, M.; Zueva, E.; Maurin, M.; Nadalin, F.; Knott, G.J.; et al. NONO Detects the Nuclear HIV Capsid to Promote cGAS-Mediated Innate Immune Activation. Cell 2018, 175, 488–501.e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchikh, M.; Cribier, A.; Raffel, R.; Amraoui, S.; Cau, J.; Severac, D.; Dubois, E.; Schwartz, O.; Bennasser, Y.; Benkirane, M. HEXIM1 and NEAT1 Long Non-coding RNA Form a Multi-subunit Complex that Regulates DNA-Mediated Innate Immune Response. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 387–399.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, R.M.; Depledge, D.P.; Bianco, C.; Thompson, L.; Mohr, I. RNA m(6) A modification enzymes shape innate responses to DNA by regulating interferon β. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1472–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Hou, J.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z.; Cao, X. The RNA helicase DDX46 inhibits innate immunity by entrapping m(6)A-demethylated antiviral transcripts in the nucleus. Nat. Immunol. 2017, 18, 1094–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesser, C.R.; Walsh, D. YTHDF2 Is Downregulated in Response to Host Shutoff Induced by DNA Virus Infection and Regulates Interferon-Stimulated Gene Expression. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0175822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Cai, B.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, L.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, B.; Gao, C. Methyltransferase-Like Protein 14 Attenuates Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein Expression to Negatively Regulate Antiviral Immunity via N(6)-methyladenosine Modification. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2100606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Hui, H.; Bray, B.; Gonzalez, G.M.; Zeller, M.; Anderson, K.G.; Knight, R.; Smith, D.; Wang, Y.; Carlin, A.F.; et al. METTL3 regulates viral m6A RNA modification and host cell innate immune responses during SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Rep. 2021, 35, 109091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Lu, Y.; Wang, X.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z.; Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. N(6)-methyladenosine RNA modification suppresses antiviral innate sensing pathways via reshaping double-stranded RNA. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Li, Q.; Meng, R.; Yi, B.; Xu, Q. METTL3 regulates alternative splicing of MyD88 upon the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response in human dental pulp cells. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2018, 22, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Wu, G.; Wu, Q.; Peng, L.; Yuan, L. METTL3 overexpression aggravates LPS-induced cellular inflammation in mouse intestinal epithelial cells and DSS-induced IBD in mice. Cell Death Discov. 2022, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karikó, K.; Buckstein, M.; Ni, H.; Weissman, D. Suppression of RNA recognition by Toll-like receptors: The impact of nucleoside modification and the evolutionary origin of RNA. Immunity 2005, 23, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Ren, X.; Wang, A.; Chen, Z.; Yao, J.; Mao, K.; Liu, T.; Meng, F.-L.; et al. Pooled CRISPR screening identifies m(6)A as a positive regulator of macrophage activation. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabd4742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Huang, M.; Liu, J.; Gu, Y.; Ma, L.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, X. Mettl3-mediated mRNA m6A methylation promotes dendritic cell activation. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S.; Zheng, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, T. METTL3-Mediated m6A Modification of TRIF and MyD88 mRNAs Suppresses Innate Immunity in Teleost Fish. Miichthys miiuy. J. Immunol. 2023, 211, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balzarolo, M.; Engels, S.; de Jong, A.J.; Franke, K.; Berg, T.K.v.D.; Gulen, M.F.; Ablasser, A.; Janssen, E.M.; van Steensel, B.; Wolkers, M.C. m6A methylation potentiates cytosolic dsDNA recognition in a sequence-specific manner. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 210030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; Maimaiti, M.; Sun, J.; Hu, J.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Hu, H. m(6)A-mediated modulation coupled with transcriptional regulation shapes long noncoding RNA repertoire of the cGAS-STING signaling. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 1785–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Y.; Ling, T.; Wang, Y.; Jia, X.; Xie, X.; Chen, R.; Chen, S.; Yuan, S.; Xu, A. Degradation of WTAP blocks antiviral responses by reducing the m(6) A levels of IRF3 and IFNAR1 mRNA. EMBO Rep. 2021, 22, e52101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, H.; Kim, G.-W.; Mir, S.A.; Khan, M.; Siddiqui, A. Interferon-stimulated gene 20 (ISG20) selectively degrades N6-methyladenosine modified Hepatitis B Virus transcripts. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.; Imam, H.; Khan, M.; Mir, S.A.; Kim, S.; Yoon, S.K.; Hur, W.; Siddiqui, A. HBV-Induced Increased N6 Methyladenosine Modification of PTEN RNA Affects Innate Immunity and Contributes to HCC. Hepatology 2021, 73, 533–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, L.; Cao, X. RNA-binding protein YTHDF3 suppresses interferon-dependent antiviral responses by promoting FOXO3 translation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, D.G.; Tsai, K.; Bogerd, H.P.; Kennedy, E.M.; Law, B.A.; Emery, A.; Swanstrom, R.; Holley, C.L.; Cullen, B.R. Epitranscriptomic Addition of m(5)C to HIV-1 Transcripts Regulates Viral Gene Expression. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 26, 217–227.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, K.; Vasudevan, A.A.J.; Campos, C.M.; Emery, A.; Swanstrom, R.; Cullen, B.R. Acetylation of Cytidine Residues Boosts HIV-1 Gene Expression by Increasing Viral RNA Stability. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 28, 306–312.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringeard, M.; Marchand, V.; Decroly, E.; Motorin, Y.; Bennasser, Y. FTSJ3 is an RNA 2’-O-methyltransferase recruited by HIV to avoid innate immune sensing. Nature 2019, 565, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirumuru, N.; Zhao, B.S.; Lu, W.; Lu, Z.; He, C.; Wu, L. N 6-methyladenosine of HIV-1 RNA regulates viral infection and HIV-1 Gag protein expression. Elife 2016, 5, e15528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-L.; Pan, C.-Y.; Tseng, Y.-T.; Chen, F.-C.; Chang, Y.-C.; Wang, T.-C. Acute effects of high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous exercise on BDNF and irisin levels and neurocognitive performance in late middle-aged and older adults. Behav. Brain Res. 2021, 413, 113472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Kumar, S.; Espada, C.E.; Tirumuru, N.; Cahill, M.P.; Hu, L.; He, C.; Wu, L. N 6-methyladenosine modification of HIV-1 RNA suppresses type-I interferon induction in differentiated monocytic cells and primary macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtney, D.G.; Kennedy, E.M.; Dumm, R.E.; Bogerd, H.P.; Tsai, K.; Heaton, N.S.; Cullen, B.R. Epitranscriptomic Enhancement of Influenza A Virus Gene Expression and Replication. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 22, 377–386.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lichinchi, G.; Zhao, B.S.; Wu, Y.; Lu, Z.; Qin, Y.; He, C.; Rana, T.M. Dynamics of Human and Viral RNA Methylation during Zika Virus Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokhale, N.S.; McIntyre, A.B.R.; McFadden, M.J.; Roder, A.E.; Kennedy, E.M.; Gandara, J.A.; Hopcraft, S.E.; Quicke, K.M.; Vazquez, C.; Willer, J.; et al. N6-Methyladenosine in Flaviviridae Viral RNA Genomes Regulates Infection. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 20, 654–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-W.; Siddiqui, A. The role of N6-methyladenosine modification in the life cycle and disease pathogenesis of hepatitis B and C viruses. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-W.; Imam, H.; Khan, M.; Siddiqui, A. N (6)-Methyladenosine modification of hepatitis B and C viral RNAs attenuates host innate immunity via RIG-I signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 13123–13133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, M.; Xue, M.; Wang, H.-T.; Kairis, E.L.; Ahmad, S.; Wei, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; et al. Nonsegmented Negative-Sense RNA Viruses Utilize N(6)-Methyladenosine (m(6)A) as a Common Strategy To Evade Host Innate Immunity. J. Virol. 2021, 95, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Kairis, E.L.; Lu, M.; Ahmad, S.; Attia, Z.; Harder, O.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, J.; et al. Viral RNA N6-methyladenosine modification modulates both innate and adaptive immune responses of human respiratory syncytial virus. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1010142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Y.-P.; Li, K.; Ye, Q.; Zhou, H.-Y.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Deng, Y.-Q.; Li, R.-T.; et al. The m(6)A methylome of SARS-CoV-2 in host cells. Cell Res. 2021, 31, 404–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burgess, H.M.; Depledge, D.P.; Thompson, L.; Srinivas, K.P.; Grande, R.C.; Vink, E.I.; Abebe, J.S.; Blackaby, W.P.; Hendrick, A.; Albertella, M.R.; et al. Targeting the m(6)A RNA modification pathway blocks SARS-CoV-2 and HCoV-OC43 replication. Genes Dev. 2021, 35, 1005–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Yin, H.; Yu, L.-L.; Cui, J.-J.; Yin, J.-Y.; Luo, C.-H.; Guo, C.-X. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 m6A modification sites correlate with viral pathogenicity. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imam, H.; Khan, M.; Gokhale, N.S.; McIntyre, A.B.R.; Kim, G.-W.; Jang, J.Y.; Kim, S.-J.; Mason, C.E.; Horner, S.M.; Siddiqui, A. N6-methyladenosine modification of hepatitis B virus RNA differentially regulates the viral life cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8829–8834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murata, T.; Iwahori, S.; Okuno, Y.; Nishitsuji, H.; Yanagi, Y.; Watashi, K.; Wakita, T.; Kimura, H.; Shimotohno, K. N6-methyladenosine Modification of Hepatitis B Virus RNA in the Coding Region of HBx. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.-W.; Imam, H.; Siddiqui, A. The RNA Binding Proteins YTHDC1 and FMRP Regulate the Nuclear Export of N(6)-Methyladenosine-Modified Hepatitis B Virus Transcripts and Affect the Viral Life Cycle. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0009721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostyusheva, A.; Brezgin, S.; Glebe, D.; Kostyushev, D.; Chulanov, V. Host-cell interactions in HBV infection and pathogenesis: The emerging role of m6A modification. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2021, 10, 2264–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, W.; Liu, Z.; Yu, S.; Jian, H.; Hou, Z.; Zeng, P. Comprehensive analysis of m6A regulators associated with immune infiltration in Hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023, 23, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, A.M.; Hayer, K.E.; McIntyre, A.B.R.; Gokhale, N.S.; Abebe, J.S.; Della Fera, A.N.; Mason, C.E.; Horner, S.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Depledge, D.P.; et al. Direct RNA sequencing reveals m(6)A modifications on adenovirus RNA are necessary for efficient splicing. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajikhezri, Z.; Kaira, Y.; Schubert, E.; Darweesh, M.; Svensson, C.; Akusjärvi, G.; Punga, T. Fragile X-Related Protein FXR1 Controls Human Adenovirus Capsid mRNA Metabolism. J. Virol. 2023, 97, e0153922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Zhou, F.; Tan, M.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Xu, W.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Deng, X.; He, M.-L. Targeting m6A modification inhibits herpes virus 1 infection. Genes Dis. 2021, 9, 1114–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansens, R.J.; Olarerin-George, A.; Verhamme, R.; Mirza, A.; Jaffrey, S.; Favoreel, H.W. Alphaherpesvirus-mediated remodeling of the cellular transcriptome results in depletion of m6A-containing transcripts. IScience 2023, 26, 107310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Ye, W.; Chen, S.; Tang, Y.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Huang, Z.; Ge, Y. METTL3-mediated m(6)A RNA modification promotes corneal neovascularization by upregulating the canonical Wnt pathway during HSV-1 infection. Cell Signal. 2023, 109, 110784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Qi, Y.; Ju, Q. Promotion of the resistance of human oral epithelial cells to herpes simplex virus type I infection via N6-methyladenosine modification. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walther, K.; Schulte, L.N. The role of lncRNAs in innate immunity and inflammation. RNA Biol. 2021, 18, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayoshi, Y.; Nishiguchi, K.; Yamamura, R.; Chujo, T.; Oshiumi, H.; Nagata, H.; Kaneko, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakata, H.; Sakakida, K.; et al. t(6)A and ms(2)t(6)A Modified Nucleosides in Serum and Urine as Strong Candidate Biomarkers of COVID-19 Infection and Severity. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).