Abstract

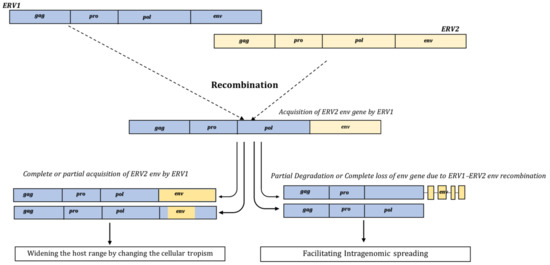

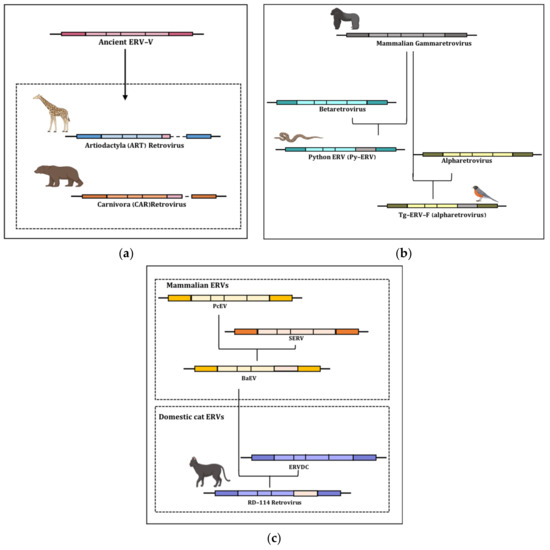

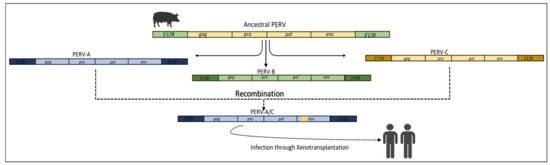

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are integrated into host DNA as the result of ancient germ line infections, primarily by extinct exogenous retroviruses. Thus, vertebrates’ genomes contain thousands of ERV copies, providing a “fossil” record for ancestral retroviral diversity and its evolution within the host genome. Like other retroviruses, the ERV proviral sequence consists of gag, pro, pol, and env genes flanked by long terminal repeats (LTRs). Particularly, the env gene encodes for the envelope proteins that initiate the infection process by binding to the host cellular receptor(s), causing membrane fusion. For this reason, a major element in understanding ERVs’ evolutionary trajectory is the characterization of env changes over time. Most of the studies dedicated to ERVs’ env have been aimed at finding an “actual” physiological or pathological function, while few of them have focused on how these genes were once acquired and modified within the host. Once acquired into the organism, genome ERVs undergo common cellular events, including recombination. Indeed, genome recombination plays a role in ERV evolutionary dynamics. Retroviral recombination events that might have been involved in env divergence include the acquisition of env genes from distantly related retroviruses, env swapping facilitating multiple cross-species transmission over millions of years, ectopic recombination between the homologous sequences present in different positions in the chromosomes, and template switching during transcriptional events. The occurrence of these recombinational events might have aided in shaping retroviral diversification and evolution until the present day. Hence, this review describes and discusses in detail the reported recombination events involving ERV env to provide the basis for further studies in the field.

1. Introduction

Retroviridae is a widely distributed family of RNA viruses that follows a replication cycle involving the reverse transcription of viral single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) into double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), which is inserted into the genome of host cells, thus enabling the expression of viral genes. Usually, retroviruses infect somatic cells but the possibility of infecting germ line cells provides a means for the colonization and fixation of retroviruses into the host genome. Such integrated retroviruses, a constitutive element of the organism genome, are termed “Endogenous Retroviruses” (ERVs) [1,2]. ERVs’ fate, their loss or persistence in the gene pool, depends on random genetic drifts and natural selection since, once integrated into the genome, ERVs follow the Mendelian inheritance pattern and accumulate in the host and thus provide a “fossil” record for ancestral retroviral diversity and their evolution within hosts [3]. One prominent example is the human ERVs (HERVs), which account for a total of 8% of the human genome. The process of such retroviral endogenization cannot just be considered as an ancient event. The present example of Koala retrovirus endogenization [4] indicates the possibility that the integration of retroviruses into the germ line can take place whenever the spread of retroviruses occurs within a host population. Such an endogenization process is not just limited to infection by one particular class of retroviruses and hence, the endogenization of different viral lineages led to the emergence of different ERV types in all vertebrate genomes accordingly [5]. The classification and nomenclature of the individual ERV groups in different vertebrates might not be fully resolved, but the similarities and differences of ERVs to exogenous retroviruses help in categorizing them into seven genera based on their phylogenetic relatedness, i.e., Alpharetroviruses, Betaretroviruses (Class II), Gammaretroviruses (Class I), Deltaretroviruses, Epsilonretroviruses, and Spumaretroviruses [6,7]. The Spumaretroviruses (Class III) are further categorized into five genera, Á., Bovispumaviruses, Equispumaviruses, Felisspumaviruses, Prosimiispumaviruses, and Simiispumaviruses [8]. Apart from the nomenclature, such classifications have also been of great help in understanding the structure of ERVs [9]. In the current review, we first describe the structure and possible role of ERVs’ env gene followed by exploring the role of recombination in its diversification.

2. Structural Features of Retroviruses

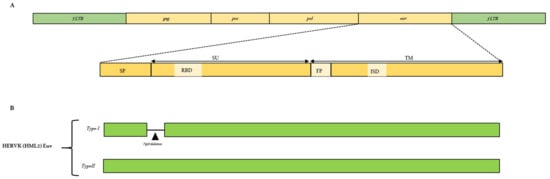

Likewise, for exogenous retroviruses, a complete proviral ERV structure possesses the gag, pro, pol, and env genes flanked by long terminal repeats (LTRs) at both ends (Figure 1A). The flanking LTRs are identical and are required to regulate transcription, while the internal regions encode viral enzymes and structural proteins. The gag gene encodes capsid (CA), matrix (MA), and nucleocapsid (NC) domains; the pro gene encodes for viral protease (PR); the pol gene encodes for reverse transcriptase (RT), ribonuclease H (RH), and integrase (IN) enzymes; and finally, the env gene includes surface unit (SU) and transmembrane unit (TM) domains (Figure 1A). Differently from the exogenous retroviruses, going through genome mutations and selection pressures, ERVs can be present as a still complete structure or, most frequently, as fragmented portions of proviruses, and they can even be present as solo LTR regions, which means that all the internal coding regions of an ERV have been deleted by recombination events [9]. In addition, even though the complete gag-pro-pol-env internal coding regions could be present, they are susceptible to mutations such as substitutions, insertions, and deletions, which might cause sequence modifications and eventually loss of function. Of note, the accumulation of gene mutations also relates to the evolutionary timespan since the beginning of ERVs’ insertion in the host germline. Among the four protein-coding genes of ERVs, gag and pol are considered to be the most conservative, while the env gene, on the other hand, is more prone to mutations and, hence, is extremely divergent [5,10]. In order to study ERVs in detail, phylogenetic analyses are performed on the pol gene and the TM region of the env gene, further comparing the pol and the env phylogenetic trees to understand the evolutionary patterns. For example, a recent study performed by Chen et al. [11] analyzed more than 30,000 ERV copies of gamma-type Env in all of the fish and amphibian genomes and transcription assemblies. Furthermore, they performed phylogenetic comparisons with the neighboring pol gene in order to study the diversification of the env gene and to detect any possible recombination event in the env gene [11]. Indeed, env divergence studies can provide insights into the emergence of retroviral evolution, such as how the new retroviral lineage emerged. Various studies have shown some evidence of cross-species transmission as well as recombination events that might have led to the generation of new viral variants of a particular class.

Figure 1.

(A) General structural features of endogenous retroviruses with a focus on the envelope protein and their main functional domains, i.e., signal peptide (SP), surface unit (SU), receptor-binding domain (RBD), fusion peptide (FP), immunosuppressive domain (ISD), and transmembrane unit (TM). (B) Structure of HML2 Env types, i.e., type I (Np9) having 292 bp deletions indicated with a black triangle and type II encoding the Rec protein.

The retroviral infection process is initiated by the Env glycoprotein encoded by the env gene that binds to the host cellular receptor(s), leading to membrane fusion. As mentioned before, the env gene encodes SU and TM subunits (Figure 1A). The SU-TM heterodimers are assembled at the cellular membrane to form an Env trimer. The SU subunit consists of a receptor-binding domain (RBD), which is responsible for the recognition of the host cellular receptor(s) and is considered more variable, making it less useful for phylogenetic analyses [12]. This is because the SU is exposed to the host immune system and, thus, is under high selective pressure [12]. While, on the other hand, the TM includes an RBD, fusion peptide (FP), heptad repeats (HR1 and HR2), ISD, and CX(6)C motif [11] and is quite conserved.

Some of the domains in the Env glycoprotein that help in such characterizations and phylogenetic analyses are the presence or absence of an immunosuppressive domain (ISD), a covalent disulfide linkage, and a hydrophobic fusion peptide (FP) which is present at the N terminal of the TM subunit. Thus, along with the RT region of the pol gene, the conserved domains of the env gene have aided in the classification of ERVs. The Env expressed on the infected cell’s surface also competes to occupy the receptor in order to prevent multiple retroviral infections within the same cell, and such a phenomenon is known as superinfection interference [13,14].

Co-Option of ERVs’ Env

Co-option is the term used for the evolution of ERVs’ viral proteins, formerly used for viral infection and replication which has been subsequently repurposed to benefit a variety of host biological functions. Various molecular processes, cellular mechanisms, and biological pathways have appeared to have repeatedly benefited from such viral co-option events [15]. One recurrent ERV co-option is related to antiviral functions, in which the ERV protein interferes with any step of viral infection by acting as a restriction factor. To date, various ERV proteins have been reported to confer resistance to viral infections such as EV3, EV6, and EV9, which are three endogenous loci of chickens that provide entry-level blockage to ALV (avian leukosis virus) infection by receptor interference [16]. Two additional examples of restriction factors are Rcmf (Rcmf and Rcmf2) [17,18] and the Fv4 gene, also known as Akvr-1. The earlier gene confers resistance to polytropic MLV strains and is incapable of expressing infectious viruses, while the latter, i.e., the Fv4 gene, confers resistance to infection by ecotropic murine leukemia virus (MLV) in laboratory mice [19]. Studies have revealed that the Fv4 gene consists of a defective MLV provirus with an intact env gene but lacks the 5′ half of the provirus as well as 5′LTR, and hence, its expression is mediated by the cellular genes close to the proviral insertion [20]. Until recently, no human ERVs were reported to be involved in resistance to infections caused by current exogenous retroviruses. However, recent studies have reported the antiviral effect of the HERV-T and HERV-R env gene. A study demonstrated the antiviral activity of HasHTenv, which is a fusion-defective HERV-T env in the human genome [21]. In order to understand HasHTenv’s role in entry restriction, a functional HERV-T Env was reconstructed and used for the identification of the entry receptor. The HasHTenv was observed to block the infection by virions consisting of a fully functional HERV-T env by receptor interference [21], thus suggesting that this HERV-T env might have evolved over time and might have led to the extinction of the retrovirus that infected our ancestors [21]. In addition to HERV-T, a recent study reported the antiviral activity of the HERV-R env gene [22]. The overexpression of HERV-R Env showed an inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2 replication, and its silencing promoted viral replication. HERV-R Env has been previously reported to stimulate the immune system and trigger inflammatory pathways. It has also been reported to be involved in autoimmunity and to be upregulated in many cancers. The study showed that the HERV-R Env activates the ERK pathway which controls the synthesis and activation of AP1 transcription factors such as c-Fos and c-Jun. One of the reasons for the ERK pathway’s activation is that the HERV-R Env contains the CKS-17-like immunosuppressive motif that is responsible for the activation of this particular pathway [23,24]. Even though the exact mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 inhibition by the HERV-R Env remains unclear, there is a clear indication of an inverse correlation between HERV-R Env protein levels and viral load. Hence, these recent findings highlight a possible evolutionary benefit of ERVs in the human genome.

One of the most studied co-opted ERV Envs are the “syncytins” proteins that are expressed in the human placenta and are known to play a crucial role in human development and thus contribute to placental syncytial structures. The syncytins are of major interest because of their domestication by hosts in different mammal lineages that co-opted different retroviral env genes for placentation [25]. The two well-characterized syncytins are syncytin-1 and syncytin-2, which are encoded by HERV-W (ERVWE1) and HERVFRD-1 (ERVFRD-1), respectively [26]. ERVWE1 was first acquired in primates approximately 25 million years ago, and while it has coding-defective gag and pol genes, it retains the env ORF, producing a protein with pregnancy-related functions, i.e., syncytin-1 [27,28]. Syncytin-1 is a 538 amino acid (aa) protein located at the 7q21.2 locus of the human chromosome consisting of a signal peptide (SP), SU, and TM [29,30]. It is highly fusogenic and actively involved in trophoblast cell fusion and differentiation, thus playing an important role in human morphogenesis, which is crucial in placental functions along with its immunomodulatory activity during pregnancy [29]. Interaction with the type-D mammalian retrovirus receptor known as hASCT-1/2 (human sodium-dependent neutral amino acid transporter type 2) aids in the activation of syncytin fusogenic activity [26,30,31]. Ever since the characterization of syncytin-1, its expression in various pathological conditions has been studied to understand its role in diseases such as multiple sclerosis and different types of cancer [31]. Similar to synctin-1 is syncytin-2 Env, encoded by a HERV-FRD provirus located on the 6p24.1 locus of the human chromosome and present in the species of both Catarrhini and Platyrrhini parvorders, indicating that its acquisition occurred more than 40 million years ago. It also has all the same functional domains as that of syncytin 1, coding for a 538 aa protein. Similar to syncytin-1, syncytin-2 also codes for 538 aa and is expressed as a precursor that is associated with forming homotrimeric complexes and has the same domains as that of syncytin-1.

Syncytin-2 is also required for functional placental syncytia and is expressed in villous cytotrophoblasts [32]. The receptor identified for syncytin-2 is the major facilitator superfamily domain containing 2a (MFSD2a), which is a transporter for an essential omega-3 fatty acid [26,32,33]. The syncytins are an example of convergent evolution, having evolved independently across the mammalian lineages. Even though not related to convergent evolution, some other Env products that are also detected in placental trophoblasts are ERVV-1, ERVV-2, ERVH48-1, ERVMER34-1, and ERV3-1 [34]. Of note, syncytins along with the other mentioned ERVs belong to the class I gamma-type Envs. In order to develop animal models to investigate the role of syncytins in placental development, syncytin-encoding genes have also been searched for in mouse genomes. This led to the identification of two retroviral envelope proteins, i.e., syncytin-A and syncytin-B [35]. Even though the syncytins identified in mouse genomes are different from that of the human genome, they still share the same characteristics, i.e., being specifically expressed in the placenta, having fusogenic properties, and being conserved since their integration into the ancestor mouse genome. In mice, the fetal capillaries are separated from the maternal blood lacunae by two different layers of syncytiotrophoblasts (ST-I and ST-II) [36]. Although distinct from the human placental structure, the ST-I and ST-II layers of the mouse placenta are still proposed as being functionally analogous to the single syncytiotrophoblast layer of the human placenta. Syncytin-A was found to be expressed in ST-I while syncytin-B was detected in the ST-II layer. Both layers coordinate to preserve the structural and functional integrity of the maternal–fetal interface [25]. Even though primate and muroid syncytins share similar characteristics, they are not orthologous and are the result of independent gene capture events in each lineage. The fifth syncytin identified is Syincytin-Ory1 [37]. Syncytin-Ory1 was identified in the Leporidae family, i.e., rabbits and hares. This syncytin gene encodes a placenta-specific Env protein with fusogenic activity that is conserved for over 12 mya. Syncytin-Ory1 has the same receptor as that of the human syncytin-1, i.e., ASCT-2 [37]. Its expression was detected in the placental junction zone, where the placental syncytia come into contact with the maternal decidua, suggesting putative involvement in syncytiotrophoblast function. A more recent functional syncytin gene reported was the sixth gene, i.e., syncytin-Car1, which was detected in 26 carnivore species [38]. Carnivores belong to the superorder Laurasiatheria and diverged from Euarchontoglires more than 80 mya. Hence, syncytin-Car1 is the oldest syncytin gene reported so far [38]. The seventh syncytin gene was the most recently discovered in the suborder Ruminantia, in those species that lack the syncytium but display synepitheliochorial placentation [39]. The cell fusion process is very limited, in which only trinucleated cells are being formed, with evidence of heterologous fusion between cells of fetal and maternal origin, a feature that is not found in any other eutherian mammals. This was identified in cows and termed as syncytin-Rum1. This syncytin was also detected in sheep genomes as well as 14 other higher ruminant species, indicating that this gene has been conserved for more than 30 mya [39]. Overall, these studies suggest that the retroviral env genes have been co-opted independently through the course of evolution.

Apart from the gamma-type Envs, one of the most studied Env proteins among the class II or beta-type ERVs is the HERV-K group HML2, which has been active and infectious for about 30 million years and makes up to 1% of all of the classified ERVs [40]. The envelope of HML2 has been divided into two subtypes, i.e., type I and type II, based on the presence or absence of 292 bp deletions in the env gene, respectively (Figure 1B). Accordingly, the two types provide alternative splicing variants of env: type I encodes for the Np9 protein in the SU region that predominantly shows nuclear localization and is suggested to act as an oncoprotein that interferes with the PLZF (promyelocytic leukemia zinc-finger protein) repression of c-myc [41]. Type II encodes a Rec protein which is similar to the Rev protein of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the Rex protein of human T cell leukemia virus (HTLV) [9,42]. It has been shown that an HML2 Env is expressed in villous and extravillous cytotrophoblasts during the whole gestation period but is found in neither placental syncytiotrophoblasts nor associated with any specific HML2 provirus at the genomic level [43]. Since HML2 proviruses are evolutionarily the youngest HERVs, their residual activity has gained a significant amount of attention, and various studies have focused on expressing their Envs to better understand their potential role in physiological and pathological conditions. Apart from HERVW, HERV-FRD, and HML2, the Env of other ERV groups even though known is not very well understood, and hence, its characterization might help in unveiling its possible functional roles [26].

4. Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, the retroviral envelope has gone through several modifications during the ERVs’ endogenization process, of which one factor was the multiple recombination events that have hence influenced ERVs’ evolution. The recombination in the env gene not only leads to the emergence of novel retroviral variants but it also aids in widening viruses’ host range and eventually the co-evolution of these retroviral elements within vertebrate genomes. Overall, it can be inferred that the env recombination events highlighted in this review have been a driving force for the genetic diversification of ERVs over the course of evolution.

Author Contributions

S.C. and N.G. drafted and edited the manuscript. S.C. generated all of the figures and tables. E.T. and L.-T.L. conceived and coordinated the study. All authors contributed to the review article and approved the submitted version. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by EU funding within the NextGenerationEU-MUR PNRR Extended Partnership initiative on Emerging Infectious Diseases (project no. PE00000007, INF-ACT). ET was supported by Bilateral Agreement CNR/NSTC Joint Research Projects 2023–2024. LTL was supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (NSTC110-2320-B-038-041-MY3) and NSTC-CNR (National Research Council of Italy) Joint Research Project (NSTC112-2927-I-038-501; NSTC113-2927-I-038-501).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aiewsakun, P.; Katzourakis, A. Endogenous viruses: Connecting recent and ancient viral evolution. Virology 2015, 479–480, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.E. Origins and evolutionary consequences of ancient endogenous retroviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, R.A. Human endogenous retroviruses: Friend or foe? APMIS 2016, 124, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarlinton, R.; Meers, J.; Young, P. Endogenous retroviruses: Biology and evolution of the endogenous koala retrovirus. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3413–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, W.E. Endogenous Retroviruses in the Genomics Era. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2015, 2, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gifford, R.J.; Blomberg, J.; Coffin, J.M.; Fan, H.; Heidmann, T.; Mayer, J.; Stoye, J.; Tristem, M.; Johnson, W.E. Nomenclature for endogenous retrovirus (ERV) loci. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blomberg, J.; Benachenhou, F.; Blikstad, V.; Sperber, G.; Mayer, J. Classification and nomenclature of endogenous retroviral sequences (ERVs). Problems and recommendations. Gene 2009, 448, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sluis-Cremer, N. Retroviral reverse transcriptase: Structure, function and inhibition. In Enzymes; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; ISBN 9780323900164. [Google Scholar]

- Vargiu, L.; Rodriguez-Tomé, P.; Sperber, G.O.; Cadeddu, M.; Grandi, N.; Blikstad, V.; Tramontano, E.; Blomberg, J. Classification and characterization of human endogenous retroviruses mosaic forms are common. Retrovirology 2016, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksakova, I.A.; Mager, D.L.; Reiss, D. Endogenous retroviruses—Keeping active endogenous retroviral-like elements in check: The epigenetic perspective. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008, 65, 3329–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liao, M.-E.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.-Y.; Cui, J. Evolution and Genetic Diversity of the Retroviral Envelope in Anamniotes. J. Virol. 2022, 96, e0207221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancino, G.; Ellerbrok, H.; Sitbon, M.; Sonigo, P. Conserved framework of envelope glycoproteins among lentiviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 1994, 188, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henzy, J.E.; Johnson, W.E. Pushing the endogenous envelope. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bénit, L.; Dessen, P.; Heidmann, T. Identification, Phylogeny, and Evolution of Retroviral Elements Based on Their Envelope Genes. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 11709–11719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, J.A.; Feschotte, C. Co-option of endogenous viral sequences for host cell function. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 25, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, H.L.; Astrin, S.M.; Senior, A.M.; Salazar, F.H. Host Susceptibility to endogenous viruses: Defective, glycoprotein-expressing proviruses interfere with infections. J. Virol. 1981, 40, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, Y.T.; Lyu, M.S.; Buckler-White, A.; Kozak, C.A. Characterization of a Polytropic Murine Leukemia Virus Proviral Sequence Associated with the Virus Resistance Gene Rmcf of DBA/2 Mice. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 8218–8224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Yan, Y.; Kozak, C.A. Rmcf2, a Xenotropic Provirus in the Asian Mouse Species Mus castaneus, Blocks Infection by Polytropic Mouse Gammaretroviruses. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 9677–9684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, H.; Odaka, T. A cell membrane “gp70” associated with Fv-4 gene: Immunological characterization, and tissue and strain distribution. Virology 1984, 133, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaguma, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Ikeda, H. Scheme for the generation of a truncated endogenous murine leukaemia virus, the Fv-4 resistance gene. J. Gen. Virol. 1992, 73, 1925–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Melo, D.; Gifford, R.J.; Bieniasz, P.D. Co-option of an endogenous retrovirus envelope for host defense in hominid ancestors. eLife 2017, 6, e22519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, S.; Gupta, N.; Verma, R.; Singh, O.N.; Gupta, J.; Kumar, A.; Yadav, M.K.; Binayke, A.; Tiwari, M.; Periwal, N.; et al. Antiviral activity of the human endogenous retrovirus-R envelope protein against SARS-CoV-2. EMBO Rep. 2023, 24, e55900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, M.; Palmarini, M. Multitasking: Making the most out of the retroviral envelope. Viruses 2010, 2, 1571–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, A.; Day, N.K.; Luangwedchakarn, V.; Good, R.A.; Haraguchi, S. A Retroviral-Derived Immunosuppressive Peptide Activates Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinases. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 6771–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavialle, C.; Cornelis, G.; Dupressoir, A.; Esnault, C.; Heidmann, O.; Vernochet, C.; Heidmann, T. Paleovirology of “syncytins”, retroviral env genes exapted for a role in placentation. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20120507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandi, N.; Tramontano, E. HERV envelope proteins: Physiological role and pathogenic potential in cancer and autoimmunity. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blond, J.-L.; Lavillette, D.; Cheynet, V.; Bouton, O.; Oriol, G.; Chapel-Fernandes, S.; Mandrand, B.; Mallet, F.; Cosset, F.-L. An Envelope Glycoprotein of the Human Endogenous Retrovirus HERV-W Is Expressed in the Human Placenta and Fuses Cells Expressing the Type D Mammalian Retrovirus Receptor. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 3321–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sha, M.; Lee, X.; Li, X.P.; Veldman, G.M.; Finnerty, H.; Racie, L.; LaVallie, E.; Tang, X.Y.; Edouard, P.; Howes, S.; et al. Syncytin is a captive retroviral envelope protein involved in human placental morphogenesis. Nature 2000, 403, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, J.; Mallet, F. ERVWE1 (endogenous retroviral family W, Env(C7), member 1). Atlas Genet. Cytogenet. Oncol. Haematol. 2011, 12, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, R.; Peng, X.; Kang, S.; Feng, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Lin, D.; Tien, P.; Xiao, G. Structural characterization of the fusion core in syncytin, envelope protein of human endogenous retrovirus family W. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 331, 1193–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandi, N.; Tramontano, E. Type W human endogenous retrovirus (HERV-W) integrations and their mobilization by L1 machinery: Contribution to the human transcriptome and impact on the host physiopathology. Viruses 2017, 9, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, M.; Varela, P.F.; Letzelter, C.; Duquerroy, S.; Rey, F.A.; Heidmann, T. Crystal structure of a pivotal domain of human syncytin-2, a 40 million years old endogenous retrovirus fusogenic envelope gene captured by primates. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 352, 1029–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, C.Y.; Wang, L.J.; Chen, C.P.; Chen, L.F.; Chen, Y.H.; Chen, H. GCM1 regulation of the expression of syncytin 2 and its cognate receptor MFSD2A in human placenta. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 83, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durnaoglu, S.; Lee, S.K.; Ahnn, J. Syncytin, envelope protein of human endogenous retrovirus (HERV): No longer ‘fossil’ in human genome. Animal Cells Syst. 2021, 25, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupressoir, A.; Marceau, G.; Vernochet, C.; Bénit, L.; Kanellopoulos, C.; Sapin, V.; Heidmann, T. Syncytin-A and syncytin-B, two fusogenic placenta-specific murine envelope genes of retroviral origin conserved in Muridae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgiades, P.; Fergyson-Smith, A.C.; Burton, G.J. Comparative developmental anatomy of the murine and human definitive placentae. Placenta 2002, 23, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidmann, O.; Vernochet, C.; Dupressoir, A.; Heidmann, T. Identification of an endogenous retroviral envelope gene with fusogenic activity and placenta-specific expression in the rabbit: A new “syncytin” in a third order of mammals. Retrovirology 2009, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornelis, G.; Heidmann, O.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Reynaud, K.; Véron, G.; Mulot, B.; Dupressoir, A.; Heidmann, T. Ancestral capture of syncytin-Car1, a fusogenic endogenous retroviral envelope gene involved in placentation and conserved in Carnivora. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E432–E441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelis, G.; Heidmann, O.; Degrelle, S.A.; Vernochet, C.; Lavialle, C.; Letzelter, C.; Bernard-Stoecklin, S.; Hassanin, A.; Mulot, B.; Guillomot, M.; et al. Captured retroviral envelope syncytin gene associated with the unique placental structure of higher ruminants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E828–E837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, R.P.; Wildschutte, J.H.; Russo, C.; Coffin, J.M. Identification, characterization, and comparative genomic distribution of the HERV-K (HML-2) group of human endogenous retroviruses. Retrovirology 2011, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denne, M.; Sauter, M.; Armbruester, V.; Licht, J.D.; Roemer, K.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Physical and Functional Interactions of Human Endogenous Retrovirus Proteins Np9 and Rec with the Promyelocytic Leukemia Zinc Finger Protein. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 5607–5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armbruester, V.; Sauter, M.; Roemer, K.; Best, B.; Hahn, S.; Nty, A.; Schmid, A.; Philipp, S.; Mueller, A.; Mueller-Lantzsch, N. Np9 Protein of Human Endogenous Retrovirus K Interacts with Ligand of Numb Protein X. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 10310–10319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Kämmerer, U.; Germeyer, A.; Stengel, S.; Kapp, M.; Denner, J. Human endogenous retrovirus K (HERV-K) is expressed in villous and extravillous cytotrophoblast cells of the human placenta. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2011, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Losada, M.; Arenas, M.; Galán, J.C.; Palero, F.; González-Candelas, F. Recombination in viruses: Mechanisms, methods of study, and evolutionary consequences. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2015, 30, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.M.C. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol. Rev. 1992, 56, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.P.; Biagini, P.; Lefeuvre, P.; Golden, M.; Roumagnac, P.; Varsani, A. Recombination in eukaryotic single stranded DNA viruses. Viruses 2011, 3, 1699–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon-Loriere, E.; Holmes, E.C. Why do RNA viruses recombine? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 617–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, E.S.; Vandewoude, S. Endogenous Retroviruses Drive Resistance and Promotion of Exogenous Retroviral Homologs. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 9, 225–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alamgir, A.S.M.; Owens, N.; Lavignon, M.; Malik, F.; Evans, L.H. Precise Identification of Endogenous Proviruses of NFS/N Mice Participating in Recombination with Moloney Ecotropic Murine Leukemia Virus (MuLV) To Generate Polytropic MuLVs. J. Virol. 2005, 79, 4664–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, L.H.; Alamgir, A.S.M.; Owens, N.; Weber, N.; Virtaneva, K.; Barbian, K.; Babar, A.; Malik, F.; Rosenke, K. Mobilization of Endogenous Retroviruses in Mice after Infection with an Exogenous Retrovirus. J. Virol. 2009, 83, 2429–2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamunusinghe, D.; Liu, Q.; Plishka, R.; Dolan, M.A.; Skorski, M.; Oler, A.J.; Yedavalli, V.R.K.; Buckler-White, A.; Hartley, J.W.; Kozak, C.A. Recombinant Origins of Pathogenic and Nonpathogenic Mouse Gammaretroviruses with Polytropic Host Range. J. Virol. 2017, 91, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuhlmann, H.; Berg, P. Homologous recombination of copackaged retrovirus RNAs during reverse transcription. J. Virol. 1992, 66, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffin, J.M. Structure, replication, and recombination of retrovirus genomes: Some unifying hypotheses. J. Gen. Virol. 1979, 42, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anai, Y.; Ochi, H.; Watanabe, S.; Nakagawa, S.; Kawamura, M.; Gojobori, T.; Nishigaki, K. Infectious Endogenous Retroviruses in Cats and Emergence of Recombinant Viruses. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 8634–8644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, L.S. Advances in understanding molecular determinants in FeLV pathology. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2008, 123, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, J.A.; Chiu, E.S.; Kraberger, S.J.; Roelke-Parker, M.; Lowery, I.; Erbeck, K.; Troyer, R.; Carver, S.; VandeWoude, S. Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) Disease Outcomes in a Domestic Cat Breeding Colony: Relationship to Endogenous FeLV and Other Chronic Viral Infections. J. Virol. 2018, 92, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erbeck, K.; Gagne, R.B.; Kraberger, S.; Chiu, E.S.; Roelke-Parker, M.; VandeWoude, S. Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) Endogenous and Exogenous Recombination Events Result in Multiple FeLV-B Subtypes during Natural Infection. J. Virol. 2021, 95, e0035321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, E.S.; Hoover, E.A.; Vandewoude, S. A retrospective examination of feline leukemia subgroup characterization: Viral interference assays to deep sequencing. Viruses 2018, 10, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, A.S.; Terry, A.; Tzavaras, T.; Cheney, C.; Rojko, J.; Neil, J.C. Defective endogenous proviruses are expressed in feline lymphoid cells: Evidence for a role in natural resistance to subgroup B feline leukemia viruses. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 2151–2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, I.M.; Andersen, P.R.; Aaronson, S.A.; Tronick, S.R. Molecular cloning of the unintegrated squirrel monkey retrovirus genome: Organization and distribution of related sequences in primate DNAs. J. Virol. 1983, 47, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Kuyl, A.C.; Mang, R.; Dekker, J.T.; Goudsmit, J. Complete nucleotide sequence of simian endogenous type D retrovirus with intact genome organization: Evidence for ancestry to simian retrovirus and baboon endogenous virus. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 3666–3676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan der Kuyl, A.C.; Dekker, J.T.; Goudsmit, J. Distribution of baboon endogenous virus among species of African monkeys suggests multiple ancient cross-species transmissions in shared habitats. J. Virol. 1995, 69, 7877–7887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, S.; Matsuo, K.; Takahashi, N.; Takano, T.; Nishimura, N. The entire nucleotide sequence of baboon endogenous virus DNA: A chimeric genome structure of murine type C and simian type D retroviruses. Japanese J. Genet. 1987, 62, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedavalli, V.R.K.; Patil, A.; Parrish, J.; Kozak, C.A. A novel class III endogenous retrovirus with a class I envelope gene in African frogs with an intact genome and developmentally regulated transcripts in Xenopus tropicalis. Retrovirology 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewannieux, M.; Dupressoir, A.; Harper, F.; Pierron, G.; Heidmann, T. Identification of autonomous IAP LTR retrotransposons mobile in mammalian cells. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löber, U.; Hobbs, M.; Dayaram, A.; Tsangaras, K.; Jones, K.; Alquezar-Planas, D.E.; Ishida, Y.; Meers, J.; Mayer, J.; Quedenau, C.; et al. Degradation and remobilization of endogenous retroviruses by recombination during the earliest stages of a germ-line invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8609–8614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chabukswar, S.; Grandi, N.; Tramontano, E. Prolonged activity of HERV-K(HML2) in Old World Monkeys accounts for recent integrations and novel recombinant variants. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1040792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henzy, J.E.; Gifford, R.J.; Johnson, W.E.; Coffin, J.M. A Novel Recombinant Retrovirus in the Genomes of Modern Birds Combines Features of Avian and Mammalian Retroviruses. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 2398–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huder, J.B.; Böni, J.; Hatt, J.-M.; Soldati, G.; Lutz, H.; Schüpbach, J. Identification and Characterization of Two Closely Related Unclassifiable Endogenous Retroviruses in Pythons (Python molurus and Python curtus ). J. Virol. 2002, 76, 7607–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scobie, L.; Takeuchi, Y. Porcine endogenous retrovirus and other viruses in xenotransplantation. Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2009, 14, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsangaras, K.; Mayer, J.; Alquezar-Planas, D.E.; Greenwood, A.D. An evolutionarily young polar bear (Ursus maritimus) endogenous retrovirus identified from next generation sequence data. Viruses 2015, 7, 6089–6107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denner, J. Porcine endogenous retroviruses and xenotransplantation, 2021. Viruses 2021, 13, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimsa, M.C.; Strzalka-Mrozik, B.; Kimsa, M.W.; Gola, J.; Nicholson, P.; Lopata, K.; Mazurek, U. Porcine endogenous retroviruses in xenotransplantation-molecular aspects. Viruses 2014, 6, 2062–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J.; Tönjes, R.R. Infection barriers to successful xenotransplantation focusing on porcine endogenous retroviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 25, 318–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patience, C.; Switzer, W.M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Griffiths, D.J.; Goward, M.E.; Heneine, W.; Stoye, J.P.; Weiss, R.A. Multiple Groups of Novel Retroviral Genomes in Pigs and Related Species. J. Virol. 2001, 75, 2771–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denner, J.; Schuurman, H.J. High prevalence of recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses (Perv-a/cs) in minipigs: A review on origin and presence. Viruses 2021, 13, 1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halecker, S.; Krabben, L.; Kristiansen, Y.; Krüger, L.; Möller, L.; Becher, D.; Laue, M.; Kaufer, B.; Reimer, C.; Denner, J. Rare isolation of human-tropic recombinant porcine endogenous retroviruses PERV-A/C from Göttingen minipigs. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klymiuk, N.; Müller, M.; Brem, G.; Aigner, B. Recombination analysis of human-tropic porcine endogenous retroviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 2003, 84, 2729–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; McGrath, C.M. Mammary neoplasia in mice. Adv. Cancer Res. 1973, 17, 353–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkina, T.V.; Piazzon, I.; Nepomnaschy, I.; Buggiano, V.; de Olano Vela, M.; Ross, S.R. Generation of a tumorigenic milk-borne mouse mammary tumor virus by recombination between endogenous and exogenous viruses. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 3895–3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovkina, T.V.; Chervonsky, A.; Dudley, J.P.; Ross, S.R. Transgenic mouse mammary tumor virus superantigen expression prevents viral infection. Cell 1992, 69, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorkinis, G.; Gifford, R.J.; Katzourakis, A.; De Ranter, J.; Belshaw, R. Env-less endogenous retroviruses are genomic superspreaders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 7385–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delviks-Frankenberry, K.; Galli, A.; Nikolaitchik, O.; Mens, H.; Pathak, V.K.; Hu, W.S. Mechanisms and factors that influence high frequency retroviral recombination. Viruses 2011, 3, 1650–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, I.M.; Callahan, R.; Tronick, S.R.; Schlom, J.; Aaronson, S.A. Major pol gene progenitors in the evolution of oncoviruses. Science 1984, 223, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiu, C.N.; Mitra, R.; Chiu, I.M. Exchange of genetic sequences of long terminal repeat and the env gene by a promiscuous primate type D retrovirus. Virus Res. 2003, 96, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mang, R.; Goudsmit, J.; van der Kuyl, A.C. Novel Endogenous Type C Retrovirus in Baboons: Complete Sequence, Providing Evidence for Baboon Endogenous Virus gag-pol Ancestry. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 7021–7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Kuyl, A.C.; Dekker, J.T.; Goudsmit, J. Discovery of a New Endogenous Type C Retrovirus (FcEV) in Cats: Evidence for RD-114 Being an FcEV Gag-Pol /Baboon Endogenous Virus BaEV Env Recombinant. J. Virol. 1999, 73, 7994–8002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henzy, J.E.; Gifford, R.J.; Kenaley, C.P.; Johnson, W.E. An intact retroviral gene conserved in spiny-rayed fishes for over 100 my. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 634–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igonet, S.; Vaney, M.C.; Vonhrein, C.; Bricogne, G.; Stura, E.A.; Hengartner, H.; Eschli, B.; Rey, F.A. X-ray structure of the arenavirus glycoprotein GP2 in its postfusion hairpin conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19967–19972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; Sattler, R.; Grossman, I.R.; Bell, A.J.; Skerrett, D.; Baxi, L.; Bank, A. A stable murine-based RD114 retroviral packaging line efficiently transduces human hematopoietic cells. Mol. Ther. 2003, 8, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, G.; Young, P.; Hanger, J.; Jones, K.; Clarke, D.; Mckee, J.; Meers, J. Prevalence of koala retrovirus in geographically diverse populations in Australia. Aust. Vet. J. 2012, 90, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappell, K.J.; Brealey, J.C.; Amarilla, A.A.; Watterson, D.; Hulse, L.; Palmieri, C.; Johnston, S.D.; Holmes, E.C.; Meers, J.; Young, P.R. Phylogenetic Diversity of Koala Retrovirus within a Wild Koala Population. J. Virol. 2017, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, U.; Keller, M.; Möller, A.; Timms, P.; Denner, J. Lack of antiviral antibody response in koalas infected with koala retroviruses (KoRV). Virus Res. 2015, 198, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lower, R.; Lower, J.; Kurth, R. The viruses in all of us: Characteristics and biological significance of human endogenous retrovirus sequences (reverse transcriptase/retroelements/human teratocarcinoma-derived virus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 5177–5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Balles, E.; Robertson, D.L.; Chen, Y.; Rodenburg, C.M.; Michael, S.F.; Cummins, L.B.; Arthur, L.O.; Peeters, M.; Shaw, G.M.; et al. Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 1999, 397, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huet, T.; Cheynier, R.; Meyerhans, A.; Roelants, G.; Wain-Hobson, S. Genetic organization of a chimpanzee lentivirus related to HIV-1. Nature 1990, 345, 356–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayward, A.; Grabherr, M.; Jern, P. Broad-scale phylogenomics provides insights into retrovirus—Host evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 20146–20151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, J.Z.; Kozak, C.A.; Boso, G. Cross-species transmission of an ancient endogenous retrovirus and convergent co-option of its envelope gene in two mammalian orders. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Cui, J. Discovery of endogenous retroviruses with mammalian envelopes in avian genomes uncovers long-term bird-mammal interaction. Virology 2019, 530, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasko, J.E.J.; Battini, J.L.; Gottschalk, R.J.; Mazo, I.; Miller, A.D. The RD114/simian type D retrovirus receptor is a neutral amino acid transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 2129–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Johnson, W.E. Retroviruses of the RDR superinfection interference group: Ancient origins and broad host distribution of a promiscuous Env gene. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 25, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malicorne, S.; Vernochet, C.; Cornelis, G.; Mulot, B.; Delsuc, F.; Heidmann, O.; Heidmann, T.; Dupressoir, A. Genome-Wide Screening of Retroviral Envelope Genes in the Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus, Xenarthra) Reveals an Unfixed Chimeric Endogenous Betaretrovirus Using the ASCT2 Receptor. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8132–8149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).