Abstract

The fusion of viral and cell membranes is one of the basic processes in the life cycles of viruses. A number of enveloped viruses confer fusion of the viral envelope and the cell membrane using surface viral fusion proteins. Their conformational rearrangements lead to the unification of lipid bilayers of cell membranes and viral envelopes and the formation of fusion pores through which the viral genome enters the cytoplasm of the cell. A deep understanding of all the stages of conformational transitions preceding the fusion of viral and cell membranes is necessary for the development of specific inhibitors of viral reproduction. This review systematizes knowledge about the results of molecular modeling aimed at finding and explaining the mechanisms of antiviral activity of entry inhibitors. The first section of this review describes types of viral fusion proteins and is followed by a comparison of the structural features of class I fusion proteins, namely influenza virus hemagglutinin and the S-protein of the human coronavirus.

1. Surface Viral Proteins

An important step in the life cycle of an enveloped virus in the process of penetration and infection of a cell is the fusion of the viral membrane with the membrane of the target cell [1,2,3,4]. All enveloped viruses, including deadly human pathogens such as the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Ebola virus, or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) fuse the envelope of the virus and cell membrane by fusion proteins [4,5]. The main purpose of the fusion proteins of these viruses is to bind to the receptor and mediate subsequent conformational rearrangements, which finally lead to the unification of lipid bilayers and the formation of a fusion pore through which the viral genome enters the cytoplasm of the cell. Mainly, viral surface proteins have two functions: cell binding and membrane fusion. These functions can be combined in one protein or performed by different proteins.

Based on structural similarity, viral fusion proteins are divided into three main classes. The first class of fusion proteins includes surface proteins of virus families Retroviridae (human immunodeficiency virus, gp41) [6,7], Filoviridae (Ebola virus, GP2) [8], Orthomyxoviridae (influenza virus, HA) [9,10], Paramyxoviridae (parainfluenza, F-protein) [11], and Coronaviridae (coronaviruses, S-protein) [12]. These are homotrimeric formations consisting of three identical subunits. They contain α-helical structures and a fusion peptide located closer to the N-terminus and hidden in the middle of the protein trimer. The fusion mechanism for these proteins is similar and is implemented using heptad repeats (HR).

Fusion proteins of the second class are characteristic of the Flaviviridae family (E proteins of Denge virus, Zika virus, and yellow fever virus) and the Bunyavirales family (Hantaan and Puumala viruses) [3,4]. Fusion protein monomers consist of three main globular domains, which are predominantly composed of β-sheets, with the fusion peptide hidden in internal loops.

Unlike classes I and II of fusion proteins, the structure of type III fusion proteins consists of α-helices and β-sheets and includes an additional globular domain. The protein comprises of three protomers with a number of α-helices located in the center of the protein. Proteins of this class are characteristic of the families Rhabdoviridae (vesicular stomatitis virus, G protein), Herpesviridae (herpes simplex virus type I, gB protein), and Baculoviridae (baculovirus, gp64 protein) [2,3].

To fuse the viral and cellular membranes, significant internal conformational changes have to occur in most viral fusion proteins. Membrane fusion involves bringing two separate bilayers of cellular and viral membranes into close contact and then combining them [5]. Clearly, such a process proceeds by overcoming a high kinetic barrier, but from the point of view of thermodynamics, this process is valuable [4].

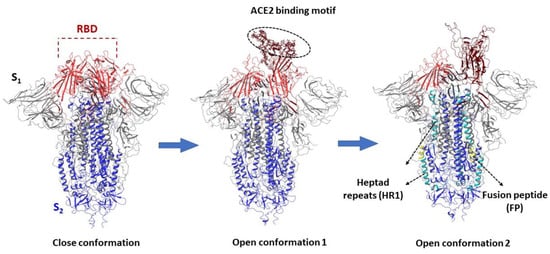

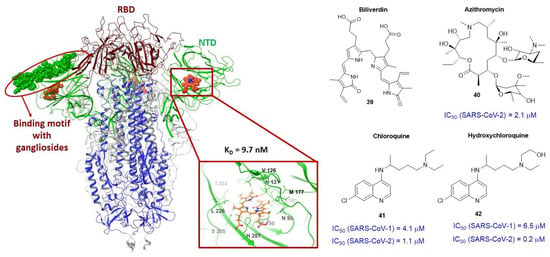

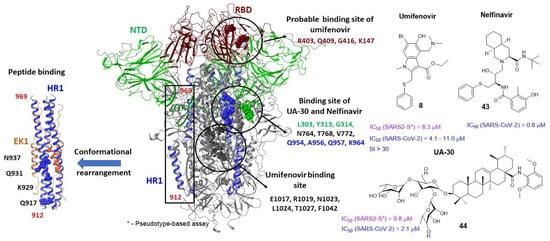

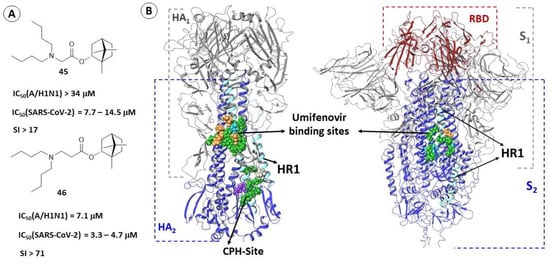

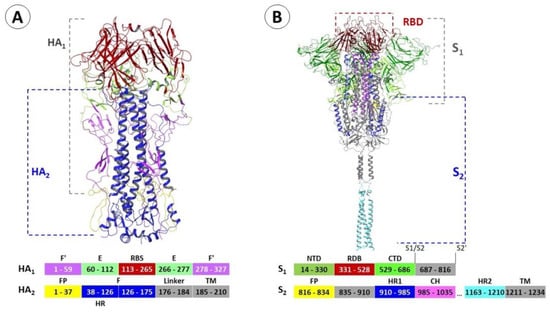

Two surface proteins of influenza virus (A) and the spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 (B) coronavirus are shown in Figure 1. Of course, the influenza virus and the coronaviruses belong to fundamentally different families of viruses. However, their surface proteins are fusion proteins of the first type. Both proteins consist of two subunits. In the first subunit, the receptor-binding site (in the case of HA) or domain (in the case of S-protein), whose key role is to bind to host cellular receptors, is localized. Heptad repeats of the second subunit are involved in structural rearrangements of proteins during the transition from pre- to post-fusion conformations, followed by the fusion of viral and cell membranes. Despite the noticeable differences between the structures of proteins, the presence of similar heptad repeats suggests that the mechanisms of fusion of viral and cell membranes for these viruses are similar.

Figure 1.

Structural features of the surface proteins of influenza virus and coronavirus according to X-ray diffraction analysis from Protein Data Bank [13]. Hemagglutinin (A) (amino acids numbering corresponds to PDB codes: 6Y5L and 1RU7 [10,14]): F’ (a. a. 1–59) and F’ (a. a. 278–327) are N- and C-terminal subdomains of HA1; E-domain [14] contains RBS—receptor-binding site, FP—fusion peptide, HR—heptad repeat, and F (a. a. 38–175) is a subdomain of HA2; TM—trans-membrane domain. S-protein (B): NTD—N-terminal domain; RBD—receptor-binding domain; CTD—C-terminal domain; S1/S2, S2′—sites of proteolysis; FP—fusion peptide; HR—heptad repeat, CH—central heptad; TM—trans-membrane domain.

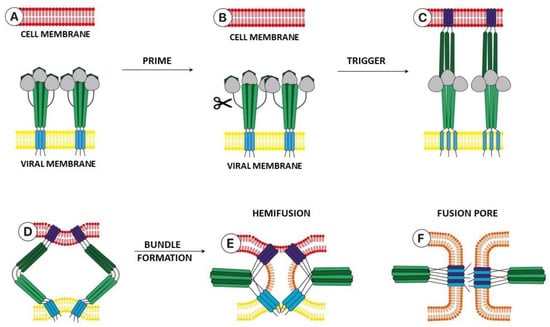

The model of the fusion process of viral and cellular membranes provided by class I fusion proteins is presented in Figure 2. Similar processes are also observed in class II and class III fusion proteins. The fusion protein is located on the surface of the viral envelope. Proteolytic cleavage or priming of a viral protein by a cellular protease is the first step (Figure 2, A→B) of the fusion mechanism that results in the opening of highly hydrophobic fusion peptides or fusion loops. In the case of class I proteins, the surface protein itself is subjected to proteolytic processing. For class II proteins, the heterodimeric partner protein “chaperone” is subjected to proteolytic cleavage [3,4]. A number of class III proteins can combine the features of the first two. However, for rhabdoviruses, whose fusion proteins belong to the class III, there is no obvious priming and most of the conformational transitions are reversible [3]. Priming transforms the protein into a metastable, i.e., thermodynamically unfavorable state B in expectation of an initiating process, for example, a decrease in the pH of the medium.

Figure 2.

Model of the fusion process of viral and cellular membranes (adapted from [4]).

Moving from pre- to post-fusion is the next key step in the process (Figure 2, B→C). In the case of influenza virus haemagglutinin activation, the protonation of the inner space of virion is a trigger: conformational changes in the protein occur at a lower pH of the medium [10]. In the case of HIV, conformational rearrangements are initiated by binding to the CD4 receptor and CCR5 or CXCR4 co-receptors [7].

Conformational rearrangements in the protein lead to the formation of an intermediate structure called pre-hairpin structure C. Evidence for the formation of such a structure based on the example of influenza virus haemagglutinin is very strong [10]. In addition, studies of other types of fusion proteins suggest that this moderately long-lived intermediate C state is characteristic of most surface proteins, taking into account their structural features [3], including the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein [15].

Further, conformational rearrangements in the pre-hairpin C bring together the N- and C-ends of the heptads, attracting the viral and cell membranes to each other, contributing to finding the definition of metastable state D. The heptad formation forms a bundle of six helices, with the formation of the so-called “hairpin”, and, as a result, the cell and viral membranes reach a state of hemi-fusion E. Then the process continues until the complete membrane is formed with the formation of a fusion pore F, through which the genetic material of the virus penetrates into the host cells. At the same time, the structure of the hairpin trimer D is characteristic of all infections with viral fusion proteins [3,4,5]. This review presents the results of theoretical studies by molecular modeling methods aimed at finding new inhibitors of surface viral proteins, namely influenza virus haemagglutinin and the S-protein of human coronaviruses, including the SARS-CoV-2 strain. The following are the chapters on haemagglutinin of the influenza virus and coronavirus glycoprotein. In both cases, binding sites of known entry inhibitors are described, indicating the pharmacophore profiles of the site and functional amino acid residues. In the Supplementary materials of the review (Supplementary Table S1), a list of PDB codes corresponding to the crystallographic data of the geometric parameters of protein complexes with known ligands is presented. In addition, the structures of the compounds described in this review, in combination with their antiviral activity data and the site of binding to surface proteins, are summarized in Supplementary Table S2. The chapters on the features of model surface proteins (methods, approaches, and limits of their applicability) are presented in the supplementary materials.

2. Hemagglutinin of Influenza Virus

2.1. Structure and Function of Hemagglutinin

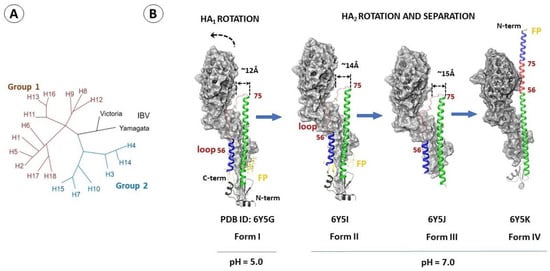

Influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) is a glycoprotein consisting of three identical subunits, each consisting of a variable HA1 globular domain binding to the cell receptor and a more conservative stem part of HA2 (Figure 1A). The key problem faced by the developers of new HA inhibitors is their high pleiomorphism [16]. Based on phylogenetic analysis, 18 antigenic subtypes of HA are described, which can be collected in 2 main groups [16,17,18]. Group 1 includes subtypes H1, H2, H5, H6, H8, H9, H11, H12, H13, H16, H17, and H18, while group 2 includes H3, H4, H7, H10, H14, and H15 (Figure 3A). In addition, there are two distinct classes of HA of influenza B viruses: the Yamagata-like and Victoria-like lineages [16]. These groups are structurally different in the regions involved in conformational rearrangements in the course of viral and cell membrane fusion [17,19].

Figure 3.

Hemagglutinin of the influenza virus. The phylogenetic tree (A). Conformational rearrangements of HA (B) the HA1 subunit is shown in gray; the short α-helix (a. a. 38–55) is highlighted in blue; the loop (a. a. 56–75) is red; the long α-helix (a. a. 76–126) is green; FP—fusion peptide is shown in yellow; the distances between the amino acids D1104 and R276 are shown in Å.

The main function of HA is to ensure the penetration of the viral genome into the cytoplasm of the host cell. Penetration of the virus begins with the binding of the HA1 globular domain to the sialic acid (SA) receptor on the cell surface [20] followed by endocytosis. The acidic environment of the endosome starts the process of conformational rearrangements in the stem part of the HA2 domain, which leads further to the fusion of the viral and cell membranes (Figure 3B) [3,4,10,17,21,22]. As a result, the so-called fusion peptide is exposed to the outside, binds to the cell membrane, and fuses the viral and endosomal membranes. According to [10], this process proceeds through the formation of intermediate conformations (forms II–IV in Figure 3B), described individually by cryo-electron microscopy methods.

The process of membrane fusion is advantageous from the point of view of thermodynamics, but proceeds rather slowly due to kinetic difficulties [21,23]. It is assumed that when the pH decreases (Figure 3B of Form I), successive conformational rearrangements of HA are triggered [10,17].

At the first step, the subunit HA1 rotates, which leads to an increase of the distance between the centers of HA1 and HA2 (Figure 3B shows the distance between the amino acids D1104 and R276) and weakening of the intermolecular contacts between the subunits (Figure 3B form II). In Form III, the distance between the domains continues to increase, accompanying conformational rearrangements in the HA2 domain. Next, the loop (the amino acid section 56–75 is highlighted in red in Figure 3B) turns by 180°, resulting in divergence of the helices. The fusion peptide at the N-end moves to become the N-end of the new α-helix (form IV) formed from an inverted short (shown in blue) and central α-helix (shown green in Figure 3B). Furthermore, the subunits HA1 and HA2, connected by a disulfide bridge, diverge and the membrane anchor is exposed [10,17,24]. According to the above observations, stabilization of the spiral loop–helix structure can be considered decisive in preventing the transition from form II to form IV [10].

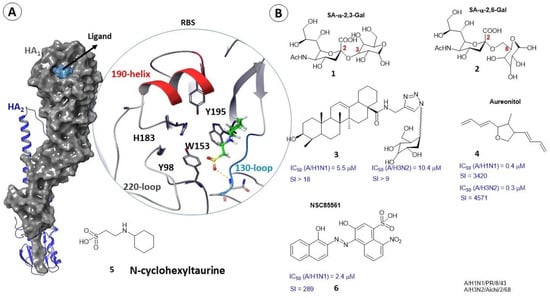

2.2. Binding Sites of Small Molecules in HA1

The receptor-binding site (RBS) is localized in the variable globular domain of HA1. It is highly variable among 16 subtypes of influenza A virus [25]. The RBS is a shallow pocket located on the surface of the globular head of HA and it consists of amino acid residues 116–261. Four amino acids (Y198, W1153, H1183 and Y1195) are conserved for all subtypes of HA except H17 and H18. Key amino acids, namely Y98 and W153, are located at the bottom of the binding pocket [26] and are surrounded by four structural elements: the 130-loop, the 150-loop, the 190-helix, and the 220-loop (Figure 4A). These elements are present in all HA subtypes, but their length and amino acid composition differ depending on the virus strain and are often key factors in the receptor recognition [25]. The mechanism of binding the key amino acids to sialic acids can be considered from the standpoint of molecular modeling [27,28]. A theoretical study by the methods of molecular dynamics showed that the amino acid Y191 on the bottom of the binding pocket HA1 forms hydrogen bonds with α-2,3 or α-2,6 bound terminal SAs in various HA subtypes. However, the specificity of recognition may depend on the HA subtype [27]. Based on the fact that SA is an HA receptor, SA-based inhibitors can be used as potential agents against HA [18] (Figure 4). Unfortunately, creating antiviral drugs from sialic acid analogs has not been successful [16,29]. The reason is the very weak binding of the sialic acid receptor itself; the value of the dissociation constant is about 3–5 μM [29]. In addition, derivatives of monovalent SA (1,2) can hardly compete with native glycans [28,30]. Alternatively, polyvalent analogs of SA [31] or inhibitors that do not contain a carbohydrate residue can be considered. Such structures include, oleic acid conjugates (3) [32], aureonitol (4) [33], and small peptides [18] that can bind within the pocket of the RBS domain, for example. Molecular docking methods for most low molecular weight inhibitors assessed their affinity for RBS and described the nature of the intermolecular interactions.

Figure 4.

Protomer of HA. The location of N-cyclohexyltaurin 5 (A) (adapted from [25]) in the receptor-binding site. Inhibitors of RBS (B). SI—selectivity index.

To develop a potential RBS inhibitor, it would undoubtedly be efficient to use the crystal structure of HA in a complex with a native ligand. The non-commercial database Protein Data Bank [13] presents two HA complexes with a small molecule of N-cyclohexyltaurin (5) located in the receptor-binding pocket (Figure 4A). According to [29], the low molecular weight compound N-cyclohexyltaurin (5) mimics the binding of the natural sialic acid receptor with the receptor-binding domain NA1 due to the formation of similar hydrogen bonds and intermolecular interactions with the polar remnants of the 130- and 220-loops (Figure 4A). It is suggested in [29] that compound 1 can be used as a scaffold structure, and structural modifications of N-cyclohexyltaurin are recommended to fill the binding pocket more tightly, thus increasing its affinity. This compound is also interesting because it can also be bound in the stem part of the HA2 domain. In other words, it can prevent HA binding to sialic acid receptors and force additional structural restrictions on the fusogenic transitions of the protein. In [34], molecular modeling techniques in conjunction with biological experiments were used to search for potential HA1 inhibitors. Based on the results of a theoretical assessment of the affinity of more than 200 compounds to the sialic acid binding site, the authors chose the lead compound NSC85561 (6) (Figure 4B). Further biological experiments to evaluate IC50 confirmed the results of molecular modeling.

Despite the fact that the first role of HA entails its binding to a cell receptor, the region close to RBS is also attractive for studying the interaction of antibodies with HA1, in particular, of influenza viruses of different strains. Thus, in [35] the methods in silico estimated the affinity of a number of antibodies to potential binding sites in the globular domain of HA. Similar studies [36] are of greater interest from the perspective of the rational design of a universal vaccine. However, for drug development, in the case of HA, binding sites located in the conservative region of the stem part of the protein are most often considered [37,38,39,40].

2.3. Binding Sites of Small Molecules in HA2

The development of numerous small molecule inhibitors of HA, aimed at blocking the fusion mechanism of viral and cell membranes, began at the end of the 20th century [16]. As a rule, experimental methods allowed an assessment of the antiviral activity of compounds and the substantiation of a potential biological target. However, the place of binding of potential HA inhibitors until this time was a mystery, and now it is often a controversial issue.

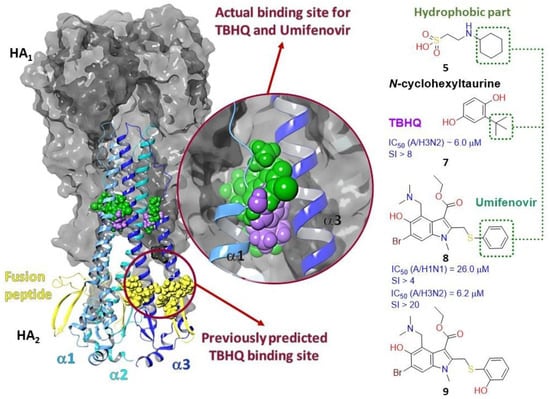

In fact, finding potential binding sites in the stem part of HA by molecular modeling methods is quite a difficult task, certainly requiring experimental evaluation. The lack of crystalline HA complexes with potential inhibitors significantly complicated the development of new drugs. It can be assumed that one of the first recorded crystals [17] with a small molecule of tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ) opened up the possibility for researchers to conduct theoretical calculations in order to search for compounds whose binding in the cavities of the second subunit of HA2 can lead to inhibition of the fusion of viral and cell membranes.

2.3.1. Binding Site of TBQH and Umifenovir

The first attempts to describe the binding site of potential HA inhibitors were made at the end of the 20th century. In 1993 and in [41], based on the results of molecular docking, it was suggested that the site of binding tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBQH) (7) is located at the site of the fusion peptide HA2 (the secondary structure is colored yellow in Figure 5). The hydrophobic cavity of the binding site is surrounded by amino acids 4, 7–19, 24, 25 of HA2, and 17, 325 of HA1 (amino acids in Figure 5 are represented as yellow spheres). In 1997, Hoffman et al. [42] estimated the affinity of small molecules to the potential binding site described in [41] including the model compound TBHQ. However, the description of the crystal structure of HA with TBHQ [17] refuted the assumption [41]. According to electron density maps, TBQH binds to HA at the interface between two trimer protomers. In other words, three molecules of TBHQ can bind to one HA trimer. Binding sites of TBHQ are formed by the residue of the long α-helix of one protomer and the short α-helix of a neighboring protomer (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Binding sites of HA inhibitors.

Interactions of TBHQ with HA are mostly of hydrophobic nature, as the binding site is saturated with hydrophobic amino acids: L129, L298, and A2101 of one protomer and L255 and L299 on another one. In addition, compound 7 forms contact with ionized amino acids R254, E257, and E297. Then, the hypothetical inhibitory mechanism of TBHQ action is to increase the stability of the complex. According to [17], the described hydrophobic binding site is formed in only one of two phylogenetic groups of HA, and crystal complexes were recorded only for strains H14N5 and H3N2, i.e., for HA of the second group.

TBHQ and Umifenovir, sold under the name Arbidol (8) which is an antiviral drug approved in Russia and China in clinical practice [43], stabilize the pre-fusion conformation of HA. The molecule binds between two α-helices of different protomers [44] and inhibits important conformational rearrangements associated with membrane fusion at low endosomal pH (Figure 5). Wright and co-authors [45] carried out a number of structural modifications of Umifenovir and obtained its structural analog (9), whose affinity to the potential binding site of TBHQ and Arbidol is an order of magnitude higher than the value characteristic of the latter. As mentioned above, according to [29], N-cyclohexyltaurin can bind to HA1 subunits at the receptor-binding site and in the stem portion of the HA2 domain between the short and long α-helixes of different protomers. Kadam and Wilson drew attention to the hydrophobic fragment of this compound, cyclohexyl, identifying it as an analog of the hydrophobic fragments (Figure 5) of tert-butyl in TBHQ and the aromatic ring in Umifenovir, which are exposed to the same hydrophobic amino acids: L129, L298, A2101, L255, and L299.

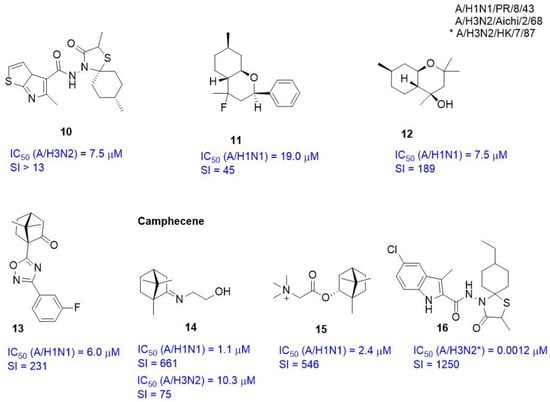

The crystallographic structures of complexes HA-TBHQ (PDB code 3EYM) and HA-Umifenovir (PDB codes 5T6N and 5T6S) formed the basis for theoretical calculations by molecular docking methods to assess the affinity of inhibitors (10–16) presented in Figure 6 to the TBHQ/Umifenovir = binding site.

Figure 6.

Inhibitors of HA binding in the TBHQ binding site.

Based on the results of molecular modeling, together with biological experimental data, the mechanism of antiviral action with a number of compounds was described: spiro-heterocyclic compounds 10 [46], isopulegol-derived substituted octahydro-2Hchromen-4-ols (11, 12) [47,48], O–acylated amidoximes and substituted 1,2,4–oxadiazoles (13) [49], camphecene (14) [50] and its analogs [51], a quaternary salt based on (-)-borneol (15) [52], and the spirothiazolidinone derivatives of indole (16) [53]. Authors used the molecular modeling methods in all these cases. They considered a hydrophobic cavity enclosed between two α-helixes of different protomers of HA (or TBHQ site) as a potential binding site. The high potential of natural terpene compounds as effective anti-viral agents should be noted [54].

2.3.2. Epitopes of HA as a Possible Binding Site for Inhibitors

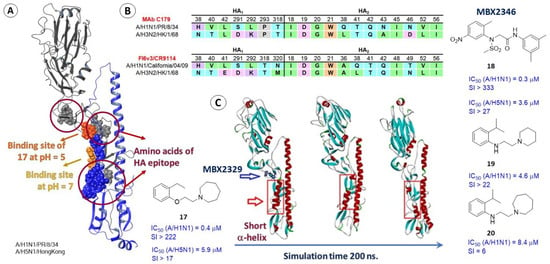

The stage of influenza virus entry into a cell can be blocked by broad-spectrum neutralizing antibodies that bind to HA epitopes [55,56] including those located on the stem part of the HA2 subunit. Various antibodies, e.g., MAb C179, CR9114, and FI6v3, come into contact with the protein surface at the interface of two subunits, forming intermolecular contacts with amino acids on the HA1 38–41, 291–293, and 318–320 and on the HA2 side 18–21 and 36, 38, 41, 42, 48, 49, 52, and 56 (Figure 7A,B). These amino acids can be considered as functional and the site of contact of HA with antibodies is the site of potential binding of HA inhibitors. Thus, in [57] the contact region of HA and antibody MAb C179 was considered as a potential binding site for two promising compounds: MBX2329 (17) and MBX2546 (18).

Figure 7.

Epitopes of HA as a possible binding site for HA inhibitors. The binding site of MBX2329 (A): the yellow and orange spheres show the location of the compound at different pH values of the medium and the amino acids of the HA epitope are shown in gray (correspond to HA1) and blue (correspond to HA2) spheres. The table (B) shows the contact between amino acids of HA and residues of antibodies MAb C179, CR9114, and FI6v3 form significant intermolecular interactions. The figure from the original paper [37] (C), where a noticeable effect of MBX2329 on the secondary structure of HA (especially on the short protomer α-helix) is visualized during 200 ns of molecular dynamic simulations.

These compounds (17 and 18) were selected from more than 106,000 chemical structures based on the results of high-throughput screening using a lentivirus-based pseudoviral system with HA on its surface. Compounds exhibit inhibitory activity against a number of strains of influenza virus in micromolar concentrations, IC50 values fall in the range from 0.30 to 3.60 μM depending on the strain of the virus. The paper [57] suggests that MBX2329 and MBX2546 bind to the stem region of HA2 and lead to disruption of the fusion process. According to NMR analysis, the binding of these compounds to HA forms a series of key contacts between atoms of these compounds and amino acids of the first and second subunits.

Subsequently, in [37] large-scale theoretical studies were carried out using molecular dynamics and showed that the most likely binding site of MBX2329 at pH = 7 is located at the border of two subunits in a hydrophobic pocket surrounded by side chains V131, L1290, T1316, I247, T248, and V251. It is noteworthy that when simulating the interaction of the ligand with the HA surface at a reduced pH, its estimated binding site is slightly higher (the molecule is shown in orange). At the same time, according to the results of molecular dynamics [37], the compound is likely to have a significant effect on the secondary structure of HA (Figure 7C), namely the short α-helix.

Large-scale theoretical calculations conducted using methods of molecular dynamics allowed the authors of [37] to describe the possible mechanism of the inhibitory action of MBX2329. The module of heptad repeats of HA plays a key role in conformational rearrangements, in which the loop connecting the short and long α-helices changes its secondary structure and leads to the formation of one α-helix. To control this transition, water molecules have to interact directly with hydrophilic amino acid residues [37,58]. Then, the main inhibitory effect of agent 17 is attributed to it stabilizing the bonds of two subunits and preventing water molecules from entering the HA. Interestingly, the paper [59] describes inhibitors of HA 19 and 20 (Figure 7) as compounds similar in their structural and pharmacophoric descriptors to substance MBX2329. Compounds 19 and 20 are active against influenza virus strain A/H1N1/PR/8/34 in micromolar concentrations. It is logical to assume that the binding of these compounds to HA should occur at the epitope site, as occurs with agent 17. However, the paper [59] suggests that inhibitors 19 and 20 bind in the TBHQ site (Figure 5). The influenza virus strain resistant to 19 contains the amino acid substitutions T2107I and R2153I. Authors of [59] believe that the T2107I mutation is the most significant and is located in a cavity close to the TBHQ site. The results of molecular modeling (docking and molecular dynamics) show that the studied compound can bind in the TBHQ site to form intermolecular interactions with the same residues. Why the authors did not consider alternative binding options remains a mystery.

Based on the crystal structures of complexes HA with FI6v3 and CR9114, small cyclic peptides were developed [60]. New peptides exhibit nanomolar activity by binding to a highly conserved stem epitope and blocking conformational rearrangements of HA. Crystal structures of peptide complexes with HA of the A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 virus strain (H1N1) are presented in the Protein Data Bank (a list of PDB codes is presented in SM-Table S1).

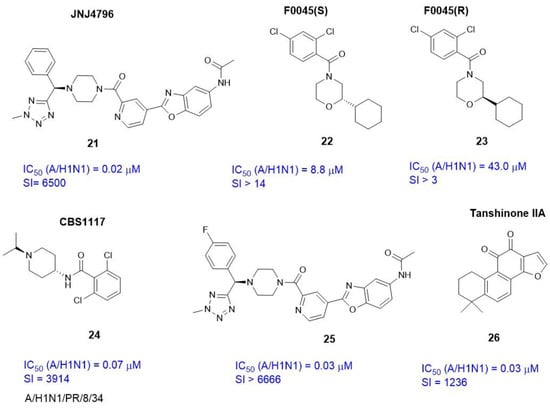

In 2009, Ekiert and co-workers [61] described the antibody bnAb CR6261. The antibody binds to the surface of the stem part of HA and neutralizes most of the influenza A viruses. The presence of the crystal complex HA-CR 6261 (PBD code 3GBN) inspired the authors of [62] to develop a low molecular weight inhibitor JNJ4796 (21) (Figure 8). The main idea of creating compound 21 was to search for small molecules that mimic the binding of CR6261 to the surface of HA. Authors of [62] screened about 500,000 low-molecular compounds that selectively targeted the CR6261 epitope on HA. As a result, within the benzylpiperazine class, the active compound JNJ4796 (21) was identified.

Figure 8.

Inhibitors of HA binding in the HA epitopes.

An epitope recognized by the small molecule 21 was similar to the epitopes associated with bnAb, namely CR6261, FI6v3, and CR9114. In other words, agent 21 binds in a hydrophobic pocket on the outer surface of HA (H1) and mimics CR6261-like intermolecular interactions with amino acids: H118, H138, L142, T1318, G220, W221, T241, and L256. Thus, the mechanism of antiviral action of 21 is to inhibit pH-sensitive conformational rearrangements that are triggered by the fusion of viral and cell membranes. The compound exhibits antiviral activity against influenza A virus strains at nanomolar concentrations (Figure 8).

The crystal structures of the complexes of HA with ligands 21–24 formed the basis for the development of new antivirals, namely potential inhibitors of HA. Thus, the paper of [63] describes temporins which are small peptides that presumably bind within the region of HA in contact with the antibodies. Molecular modeling to assess the affinity of temporins to the binding site was carried out on the basis of crystalline structures of small peptides with HA described in [60].

The design and application of a fluorescent polarization (FP) probe based on P7 peptide allowed the authors of [64] to conduct high-throughput screening (HTS) of 72,000 compounds and identify a new low molecular weight molecule F0045(S) (22) with high affinity for the stem epitope HA H1N1 (Figure 8). The crystal structure of the HA-22 complex (PDB code 6WCR) was recorded. Interestingly, the R-stereoisomer F0045(R) (23) is characterized by less pronounced antiviral activity. The authors of [64] associate such selective activity of stereoisomers with different locations of the aromatic ring in the hydrophobic pocket of the HA epitope.

The binding region of CBS1117 (24) [65] with H5 HA was described using methods of X-ray crystallography, NMR, and experiments using site-directed mutagenesis. Compound 24 binds on the protein surface and forms a number of intermolecular interactions with amino acids that play a key role in binding to antibodies.

The authors of [66] performed a structural modification of agent JNJ4796 (21) and synthesized a number of analogs containing substituents in the aromatic ring. Based on a number of biological tests, the leader-4-fluorine derivative compound was selected (25) (Figure 8). Compound 25 exhibits antiviral activity against influenza strain A/H1N1 that is commensurate with the activity of agent 21. At the same time, the introduction of a fluorine atom into position 4 of the aromatic ring 21 leads to a decrease in the cytotoxicity of the new compound 25, and as a result, to an increase in the selectivity index. For molecular docking, authors of [66] used the crystal structure of the HA-JNJ 4796 (21) complex with an estimated affinity of 25 to the binding site and described an additional hydrophobic interaction between the fluorine atom (25) and V218.

According to [67], Tanshinone IIA(26) (Figure 8), the biologically active compound isolated from redroot sage (Salvia miltiorrhiza) exhibits pronounced activity against influenza virus A/H1N1. The affinity of 26 to the binding site of HA was evaluated by molecular docking and molecular dynamics. F0045 (S) and the crystal structure of HA complex with F0045 (PDB code 6WCR) were considered as a reference compound in theoretical calculations.

2.3.3. Alternate Binding Sites

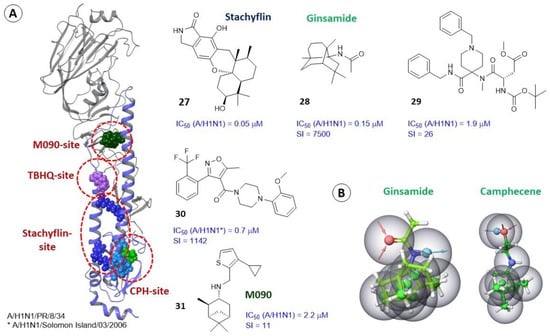

In some cases, compounds exhibiting pronounced antiviral activity against influenza and exhibiting inhibitory activity against HA can bind in alternative binding sites other than the location of previously discussed TBHQ and Umifenovir, as well as from the sites of contact of antibodies with protein surfaces. Thus, in [68] the authors described the antiviral activity of natural metabolite stachyflin (27) against a number of strains of the influenza virus (Figure 9). Stachyflin inhibits the replication of viruses of different strains, such as A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1), A/Narita/1/2009 (H1N1) pdm, A/Singapore/1/1957 (H2N2), A/duck/Hokkaido/5/1977 (H3N2), A/Hong Kong/483/1997 (H5N1), A/turkey/Italy/4580/1999 (H7N1), and others. The antiviral activity of 27 was tested against various strains of the virus corresponding to 14 types of HA. After selecting and sequencing the stachyflin-resistant strain (A/WSN/1933 (H1N1), A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (H1N1), A/chicken/Ibaraki/1/2005 (H5N2), and A/chicken/Taiwan/A703-1/2008 (H5N2)), a substitution of amino acid residues in the α-helices of the HA2 subunit, was detected. Molecular modeling allowed authors to describe the probable Stachyflin-binding site. A small cavity is located between two α-helices of one protomer HA2. In a resistant strain of the virus, the amino acids D237, L251, T2107, and L2121 are replaced, and they are the key in the binding site (Figure 9A), forming a series of intermolecular interactions with the compound under study. The proposed mechanism of inhibitory action of agent 27 is as follows: the molecule is located between two α-helices (short and long) forming a series of non-covalent interactions with amino acid residues and, as a result, keeping the α-helices in a compressed state. The binding of stachyflin increases the energy barrier required for this conformational transition and the formation of one α-helix.

Figure 9.

Binding sites of HA inhibitors. The binding sites of stachyflin, camphecene, and M090 (A). The pharmacophoric profiles of camphecene and ginsamide (B) hydrophobic regions of the molecule are shown in green and donor and acceptor regions are in blue and red, respectively. The protonated nitrogen atom is shown in blue.

New antiviral amino derivatives based on (+)-camphor are described in [50,69] in which camphecene (14) or CPH (1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo [2.2.1] heptane-2-ilidene-aminoethanol) was identified as a lead compound (Figure 6). Camphecene demonstrates high inhibitory activity against a number of strains of influenza virus, including rimantadine-resistant ones. Numerous biological experiments have shown a wide range of its anti-influenza activity at low concentrations, as well as very low toxicity. In addition, there is experimental evidence that camphecene reduces the fusogenic activity of HA. HA was considered as a biological target (Figure 9A) based on the presence of a hydrophobic fragment in camphecene similar in pharmacophoric profile to fragments of already known inhibitors of HA TBHQ and Umifenovir. Firstly, the location of TBQH/Umifenovir (or TBHQ site) was considered as a potential site for the binding of camphecene. According to the results of molecular docking, camphecene shows affinity to this site commensurate with the data characteristic of reference inhibitors. In order to confirm the mechanism of antiviral action, the work in [70] described a camphecene-resistant influenza virus obtained as a result of the propagation of influenza A/H1N1 virus for 6 passages in the presence of increasing concentrations of the drug. Sequencing of the the HA gene of the camphecene-resistant influenza virus showed the presence of V2115L amino acid substitution (the numbering of amino acids corresponds to the PBD code 4LXV [71], the original article uses the numbering of the PBD code 1RU7 [14]) in the stem portion of hemagglutinin in the HA2 subunit. Molecular modeling showed that there is a small hydrophobic cavity at the site of proteolysis of HA2 (Figure 9A) where the camphecene molecule can be embedded, thus forming hydrogen bridges with V2115 and I19. Replacing valine with leucine leads to a reduction in the size of the cavity, which affects the decrease in affinity of camphene to this binding site. It is extremely important to note that the resulting mutants are characterized by a significant decrease in virulence and pathogenicity for animals. Such a remarkable result seems to be associated with the peculiarities of hemagglutinin functioning, specifically with its interaction with cellular proteases.

Another compound, ginsamide (28) [72], exhibiting pronounced activity against influenza virus can bind at the CPH site by contacting V2115. This binding site was selected based on the similarity of the pharmacophoric profiles of camphecene and ginsamide (Figure 9B) as well as based on the result of sequencing a ginsamide-resistant influenza A virus. Serial passages of the influenza virus in the presence of ginsamide resulted in the selection of the V2115L mutation in HA2. In other words, both camphecene [70] and ginsamide [72] can induce virus resistance using the same mutation in HA2.

Interestingly, [73] describes a hydrophobic cavity surrounded by amino acid residues K2123, E2120, Y2119, and F19 which are located close to V2115 (Figure 9A). Based on the data obtained by molecular docking and molecular dynamics methods, it is assumed that the compound (29) (Figure 9) will exhibit its antiviral activity precisely by binding at the described binding site or at the camphecene-binding site. The presence of a hydrophobic cavity at the site of proteolysis that is suitable for binding small molecules was mentioned earlier in [70]. However, [73] describes this site as a fundamentally new binding site for potential HA inhibitors.

In [74], new compounds active against the influenza virus were identified. Based on a number of biological experiments, Kim and co-authors identified one leading compound IY7640 (30). The molecular target of agent 30 is the highly conserved stem region of HA. Using molecular docking methods, the authors searched for a potential binding site of substance 30 considering the HA epitopes and the TBHQ site. Agent 30 binds between two key α-helixes close to the viral membrane.

Finally, it is necessary to mention another binding site of HA inhibitors on the example of substance M090 (31), located between the long α-helix and the loop connecting the short and long α-helixes [75]. The binding of M090 (Figure 9) can prevent a transition in which two α-spirals turn into one. The binding of 31 was also predicted on the basis of molecular modeling.

The selection of the binding site and inhibitors of HA is one of the most difficult tasks of molecular modeling in the development of anti-influenza drugs. The presence of crystal structures of HA complexes with ligands and probable inhibitors facilitates the task of researchers greatly. However, here it is necessary to consider the difference in structural descriptors and pharmacophoric profiles of the studied compounds.

Typically, in most scientific publications describing alternative binding sites, molecular modeling methods are presented in conjunction with data from physical and biological experiments, such as NMR studies and/or mutagenesis. Of course, to confirm the alternative locations of potential HA inhibitors, it is desirable to have a crystal structure of the HA-inhibitor complex.

2.4. Differences in the Binding Sites of HA2 of Different Phylogenetic Groups

The antiviral activity of most known HA inhibitors is evaluated against different strains of the influenza virus. A number of the studied compounds show activity against strains of influenza belonging to either the first or the second HA types. Thus, spirocyclic derivatives 10 [46] show pronounced activity against the A/H3N2 virus and are not active against A/H1N1. In contrast, agent 27 [68] is active against strains that belong to the first group of HA: IC50(H1) = 0.05–1.95 μM, IC50(H2) = 0.16 μM, IC50(H5) = 0.17–4.70 μM, and IC50(H6) = 0.44–0.65 μM; however, IC50 values against viruses bearing HA of the second group (H3, H4, and H7–H16) were above 6.50 μM. This compound [74] inhibits influenza viruses of A/H1N1, A/H1N1pdm09, A/H5N1, and A/H6N2 subtypes at concentrations of 0.7 up to 59.6 μM, while A/H3N2 and A/H7N9 viruses were inhibited with IC50′s of 83.0–221.0 μM. Clearly, this selective activity of HA inhibitors is most likely related to the structural features of the protein. Despite conservatism of the stem part of the HA domain, the amino acids surrounding the described binding sites may differ.

For example, in [17] when describing the binding site of TBHQ, it is assumed that such a hydrophobic region can only be found in HA2 of the second phylogenetic group. The crystal structures of HA with TBHQ and Umifenovir are recorded for H3, H7, and H14 subtypes. In fact, in [45] it is shown that Umifenovir binds with higher affinity to HA of the second group (KD = 5.6–7.9 μM) than with HA of the first group (KD = 18.8–44.3 μM). In [40], molecular modeling methods evaluated the affinity of Umifenovir to various binding sites in HA. The paper notes that Umifenovir can interact with all subtypes of HA, but with different affinities. Umifenovir shows the greatest affinity to the H7 binding site.

In a recently published paper [49], the authors compared the amino acid sequences of the binding sites for M090, TBHQ, and CPH for influenza viruses of H1 and H7 subtypes. Although the pharmacophoric profiles of the described binding sites are similar, in all cases hydrophobic amino acids predominate. Indeed, a number of a. a. substitutions are observed. In this case, it can be expected that the affinity of potential inhibitors to the binding sites of different types may differ [49,52]. Investigations [68,74] also take into account the difference in amino acid residues of potential binding sites of substances 27 and 30, which explains their different antiviral activity against different subtypes of influenza virus.

Based on the analysis of the literature data, it can be noted that HA inhibitors are characterized by different structural descriptors and different pharmacophoric profiles. It is very difficult to divide them into any groups and associate their structure with the place of binding in the HA. Moreover, inhibitors vary even in size and molecular weight. One would assume that small molecules, such as substances 11–15 (Figure 6), should bind only in small hydrophobic pockets, such as the TBHQ or CPH site, while large molecules such as JNJ4796 can bind to the surface of the HA on the epitope side. However, it is not that simple. Small molecules such as 17, 18, 22, 23, 24, and 26 (Figure 8) inhibit the function of HA by binding to the epitope surface, and bigger molecules, namely 8–10, 16, and 29 (Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 8), can localize to the stem part of the protein, thus preventing conformational rearrangements. Objectively, the search for new inhibitors of entry is impossible without understanding the mechanism of HA action. It is necessary to clearly understand what specific conformational rearrangements occur during the transition from pre- to post-fusion conformation and when it occurs. Fortunately, this process is well studied and described. In addition, many scientific publications and, of course, the presence of geometric parameters of HA complexes with various ligands greatly help in solving the problem. Moreover, the use of molecular modeling methods allows one not only to predict the binding site or describe the mechanism of antiviral action, but also to substantiate the biological properties of the virus carrying certain amino acid substitutions. Such properties include, for example, the pathogenicity of the virus, the spectrum of target cells, sensitivity or resistance to potential or used inhibitors, etc.

4. Conclusions

In this review, we described inhibitors of influenza virus and coronavirus fusion proteins. Of course, these viruses belong to different families. The similarity lies only in the mechanism of fusion of the viral and cell membranes, the key role of which is played by the surface proteins hemagglutinin and spike protein. However, the choice of these two proteins is not accidental. Firstly, we describe two almost borderline cases. The HA protein is well described. The mechanism of its action is clear. The protein data base contains the geometric parameters of the protein with ligands in various binding sites. The spike protein was also studied and its mechanism of action was described, but with some contradictions. However, during two years of the ongoing pandemic, there are still no data on geometric parameters of the protein in combination with small molecular weight ligands. For this reason, it is extremely difficult to describe the mechanism of antiviral action of compounds. Secondly, despite the structural differences of proteins, some cavities considered as potential inhibitor binding sites have a similar pharmacophoric profile. This explains the antiviral activity of Umifenovir and borneol esters against the influenza virus and the S-protein of coronavirus. In addition, this fact may be a loophole for the search and development of broad-spectrum antiviral drugs.

Molecular modeling (docking or molecular dynamic simulations) and quantum-chemical calculations are powerful tools that, with the right approach, can greatly help the task of finding and developing antiviral drugs. However, in order to find the binding site of the entry inhibitors and to create an adequate model for theoretical calculations, data from biological experiments are needed, at a minimum to confirm the choice of a potential biological target, such as an experiment on the time of addition. Obtaining resistant strains of the virus followed by sequencing and localization of amino acid substitutions and NMR studies suggest a likely binding site. As a rule, after that molecular modeling methods are used to visualize and describe the mechanism of antiviral activity of the studied compounds, including the selective one. A clear understanding of the mechanism of fusion, indicating which specific amino acid residues are involved in conformational rearrangements, can help researchers to determine the binding sites of potential entry inhibitors. We hope that the results of scientific publications described in this review will be useful to researchers for finding a “magic” molecule and creating a non-toxic antiviral drug with a broad spectrum of activity.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/v15040902/s1. Table S1: PDB codes of complexes HA of influenza virus and S-protein of coronavirus with ligands and Table S2: Inhibitors of the surface protein of influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2. References [17,28,29,30,32,33,34,37,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,57,59,60,61,62,72,73,74,75,86,87,89,91,92,95,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,118,119] were cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B. and O.I.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.B.; writing—review and editing, O.I.Y., V.V.Z., D.N.S. and N.F.S.; visualization, S.S.B.; supervision, N.F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation (no 122031400255-3 and 1021051703312-0-1.4.1) and by the program of Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (Agreement No. 075-15-2021-1355 dated 12 October 2021) as part of the implementation of certain activities of the Federal Scientific and Technical Program for the Development of Synchrotron and Neutron Research and Research Infrastructure for 2019–2027.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the theoretical group “Quanta and Dynamics”: https://monrel.ru/ accessed on 31 July 2022.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviation

| a. a. | amino acids |

| ACE2 | angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 |

| CoV | coronavirus |

| CTD | C-terminal domain |

| CPH | camphecene |

| F | fusion protein |

| FP | fusion peptide |

| G | glycoprotein |

| HA | influenza virus hemagglutinin |

| HA1 | first subunits of influenza virus hemagglutinin (global head) |

| HA2 | second subunits of influenza virus hemagglutinin (stem part) |

| HIV-1 | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| HR | heptad repeat |

| HTS | High-throughput screening |

| LA | linoleic acid |

| MERS-CoV | middle east respiratory syndrome |

| RBD | receptor binding domain of coronavirus |

| RBS | hemagglutinin receptor binding site |

| NTD | N-terminal domain |

| PIV | parainfluenza virus |

| QM | quantum mechanic |

| S | S-protein or glycoprotein of coronavirus |

| S1 | first subunit of coronavirus S-protein |

| S2 | second subunit of coronavirus S-protein |

| SI | selectivity index |

| SARS | severe acute respiratory syndrome |

| TBEV | tick-borne encephalitis virus |

| TMD | trans-membrane domain |

| VSV | vesicular stomatitis virus |

References

- White, J.M.; Whittaker, G.R. Fusion of Enveloped Viruses in Endosomes. Traffic 2016, 17, 593–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, S.C. Viral membrane fusion. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.C. Viral membrane fusion. Virology 2015, 479, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, C.T.; Dutch, R.E. Viral Membrane Fusion and the Transmembrane Domain. Viruses 2020, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, J.M.; Delos, S.E.; Brecher, M.; Schornberg, K. Structures and Mechanisms of Viral Membrane Fusion Proteins: Multiple Variations on a Common Theme. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 43, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denolly, S.; Cosset, F.-L. HIV fusion: Catch me if you can. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.E.; Kiessling, V.; Pornillos, O.; White, J.M.; Ganser-Pornillos, B.K.; Tamm, L.K. HIV-cell membrane fusion intermediates are restricted by Serincs as revealed by cryo-electron and TIRF microscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15183–15195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniac, D.R.; Timothy, B.F. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein spike within the virion envelope at 11 Å resolution. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blijleven, J.S.; Boonstra, S.; Onck, P.R.; van der Giessen, E.; van Oijen, A.M. Mechanisms of influenza viral membrane fusion. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2016, 60, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.J.; Gamblin, S.J.; Rosenthal, P.B.; Skehel, J.J. Structural transitions in influenza haemagglutinin at membrane fusion pH. Nature 2020, 583, 150–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.-S.; Paterson, R.G.; Wen, X.; Lamb, R.A.; Jardetzky, T.S. Structure of the uncleaved ectodomain of the paramyxovirus (hPIV3) fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 9288–9293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, C.B.; Farzan, M.; Chen, B.; Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, H.M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamblin, S.J.; Haire, L.F.; Russell, R.J.; Stevens, D.J.; Xiao, B.; Ha, Y.; Vasisht, N.; Steinhauer, D.A.; Daniels, R.S.; Elliot, A.; et al. The structure and receptor binding properties of the 1918 influenza hemagglutinin. Science 2004, 303, 1838–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.; Xu, W.; Liu, S. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Cui, Q.; Caffrey, M.; Rong, L.; Du, R. Small molecule inhibitors of influenza virus entry. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.J.; Kerry, P.S.; Stevens, D.J.; Steinhauer, D.A.; Martin, S.R.; Gamblin, S.J.; Skehel, J.J. Structure of influenza hemagglutinin in complex with an inhibitor of membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17736–17741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, M.; Shen, X.; Liu, S. Influenza A Virus Entry Inhibitors Targeting the Hemagglutinin. Viruses 2013, 5, 352–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, V.N.; Russell, C.A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matrosovich, M.; Herrler, G.; Klenk, H.D. Sialic acid receptors of viruses. Top. Curr. Chem. 2015, 367, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Wilson, I.A. Structural Characterization of an Early Fusion Intermediate of Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 5172–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, B.S.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Influenza Virus-Mediated Membrane Fusion: Determinants of Hemagglutinin Fusogenic Activity and Experimental Approaches for Assessing Virus Fusion. Viruses 2012, 4, 1144–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernomordik, L.V.; Kozlov, M.M. Protein-Lipid Interplay in Fusion and Fission of Biological Membranes. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2003, 72, 175–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.J.; Nans, A.; Calder, L.J.; Turner, J.; Neu, U.; Lin, Y.P.; Ketelaars, E.; Kallewaard, N.L.; Corti, D.; Lanzavecchia, A.; et al. Influenza hemagglutinin membrane anchor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 10112–10117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazniewski, M.; Dawson, W.K.; Szczepińska, T.; Plewczynski, D. The structural variability of the influenza A hemagglutinin receptor-binding site. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2018, 17, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M. Influenza Virus Entry. In Viral Molecular Machines; Springer Science+Business Media, LLC: Berlin, Germany, 2012; pp. 201–221. [Google Scholar]

- Priyadarzini, T.R.K.; Selvin, J.F.A.; Gromiha, M.M.; Fukui, K.; Veluraja, K. Theoretical Investigation on the Binding Specificity of Sialyldisaccharides with Hemagglutinins of Influenza A Virus by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 34547–34557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Wang, B. Computational studies of H5N1 hemagglutinin binding with SA-α-2, 3-Gal and SA-α-2, 6-Gal. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 347, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.U.; Wilson, I.A. A small-molecule fragment that emulates binding of receptor and broadly neutralizing antibodies to influenza A hemagglutinin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 4240–4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, Y.; Yao, S.; Ge, H.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, W.; Wang, H.Y.; et al. Discovery of potential small molecular SARS-CoV-2 entry blockers targeting the spike protein. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 43, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Du, W.; Somovilla, V.J.; Yu, G.; Haksar, D.; De Vries, E.; Boons, G.J.; De Vries, R.P.; De Haan, C.A.M.; Pieters, R.J. Enhanced Inhibition of Influenza A Virus Adhesion by Di- and Trivalent Hemagglutinin Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6398–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Su, Y.; Yang, F.; Xiao, S.; Yin, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhong, J.; Zhou, D.; Yu, F. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of amino acids-oleanolic acid conjugates as influenza virus inhibitors. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 2019, 27, 115147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacramento, C.Q.; Marttorelli, A.; Fintelman-Rodrigues, N.; De Freitas, C.S.; De Melo, G.R.; Rocha, M.E.N.; Kaiser, C.R.; Rodrigues, K.F.; Da Costa, G.L.; Alves, C.M.; et al. Aureonitol, a fungi-derived tetrahydrofuran, inhibits influenza replication by targeting its surface glycoprotein hemagglutinin. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-J.; Yeh, C.-Y.; Cheng, J.-C.; Huang, Y.-Q.; Hsu, K.-C.; Lin, Y.-F.; Lu, C.-H. Potent sialic acid inhibitors that target influenza A virus hemagglutinin. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.P.; Do, P.-C.; Amaro, R.E.; Le, L. Molecular Docking of Broad-Spectrum Antibodies on Hemagglutinins of Influenza A Virus. Evol. Bioinforma. 2019, 15, 1176934319876938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauch, E.M.; Bernard, S.M.; La, D.; Bohn, A.J.; Lee, P.S.; Anderson, C.E.; Nieusma, T.; Holstein, C.A.; Garcia, N.K.; Hooper, K.A.; et al. Computational design of trimeric influenza-neutralizing proteins targeting the hemagglutinin receptor binding site. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 667–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, S.; Wang, T.; Kuai, Z.; Qian, M.; Tian, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, H.; et al. Exploration of binding and inhibition mechanism of a small molecule inhibitor of influenza virus H1N1 hemagglutinin by molecular dynamics simulation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Zhu, Z.; Ding, Y.; Wu, W.; Yang, J.; Liu, S. An oligothiophene compound neutralized influenza A viruses by interfering with hemagglutinin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Biomembr. 2018, 1860, 784–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, R.; Cheng, H.; Cui, Q.; Peet, N.P.; Gaisina, I.N.; Rong, L. Identification of a novel inhibitor targeting influenza A virus group 2 hemagglutinins. Antivir. Res. 2021, 186, 105013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Abouzid, M. Arbidol targeting influenza virus A Hemagglutinin; A comparative study. Biophys. Chem. 2021, 277, 106663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodian, D.L.; Yamasaki, R.B.; Buswell, R.L.; Stearns, J.F.; White, J.M.; Kuntz, I.D. Inhibition of the Fusion-Inducing Conformational Change of Influenza Hemagglutinin by Benzoquinones and Hydroquinones. Biochemistry 1993, 32, 2967–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, L.R.; Kuntz, I.D.; White, J.M. Structure-based identification of an inducer of the low-pH conformational change in the influenza virus hemagglutinin: Irreversible inhibition of infectivity. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 8808–8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boriskin, Y.; Leneva, I.; Pecheur, E.-I.; Polyak, S. Arbidol: A Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Compound that Blocks Viral Fusion. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008, 15, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadam, R.U.; Wilson, I.A. Structural basis of influenza virus fusion inhibition by the antiviral drug Arbidol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, Z.V.F.; Wu, N.C.; Kadam, R.U.; Wilson, I.A.; Wolan, D.W. Structure-based optimization and synthesis of antiviral drug Arbidol analogues with significantly improved affinity to influenza hemagglutinin. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3744–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderlinden, E.; Göktaş, F.; Cesur, Z.; Froeyen, M.; Reed, M.L.; Russell, C.J.; Cesur, N.; Naesens, L. Novel Inhibitors of Influenza Virus Fusion: Structure-Activity Relationship and Interaction with the Viral Hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 4277–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyina, I.V.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Lavrentieva, I.N.; Shtro, A.A.; Esaulkova, I.L.; Korchagina, D.V.; Borisevich, S.S.; Volcho, K.P.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Highly potent activity of isopulegol-derived substituted octahydro-2H-chromen-4-ols against influenza A and B viruses. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2018, 28, 2061–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyina, I.V.; Patrusheva, O.S.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Misiurina, M.A.; Slita, A.V.; Esaulkova, I.L.; Korchagina, D.V.; Gatilov, Y.V.; Borisevich, S.S.; Volcho, K.P.; et al. Influenza antiviral activity of F- and OH-containing isopulegol-derived octahydro-2H-chromenes. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 31, 127677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshov, V.V.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Esaulkova, I.L.; Sinegubova, E.; Borisevich, S.S.; Popadyuk, I.I.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Novel O–acylated amidoximes and substituted 1,2,4–oxadiazoles synthesised from (+)–ketopinic acid possessing potent virus-inhibiting activity against phylogenetically distinct influenza A viruses. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 55, 128465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarubaev, V.V.; Garshinina, A.V.; Tretiak, T.S.; Fedorova, V.A.; Shtro, A.A.; Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Broad range of inhibiting action of novel camphor-based compound with anti-hemagglutinin activity against influenza viruses in vitro and in vivo. Antivir. Res. 2015, 120, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borisevich, S.S.; Gureev, M.A.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Kostin, G.A.; Porozov, Y.B.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Can molecular dynamics explain decreased pathogenicity in mutant camphecene-resistant influenza virus? J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021, 40, 5481–5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Baranova, D.V.; Galochkina, A.V.; Shtro, A.A.; Kireeva, M.V.; Borisevich, S.S.; Gatilov, Y.V.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Quaternary ammonium salts based on (-)-borneol as effective inhibitors of influenza virus. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 1965–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cihan-Üstündağ, G.; Zopun, M.; Vanderlinden, E.; Ozkirimli, E.; Persoons, L.; Çapan, G.; Naesens, L. Superior inhibition of influenza virus hemagglutinin-mediated fusion by indole-substituted spirothiazolidinones. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarovaya, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Mono- and sesquiterpenes as a starting platform for the development of antiviral drugs. Russ. Chem. Rev. 2021, 90, 488–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laursen, N.S.; Wilson, I.A. Broadly neutralizing antibodies against influenza viruses. Antivir. Res. 2013, 98, 476–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dreyfus, C.; Ekiert, D.C.; Wilson, I.A. Structure of a Classical Broadly Neutralizing Stem Antibody in Complex with a Pandemic H2 Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7149–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, A.; Antanasijevic, A.; Wang, M.; Li, B.; Mills, D.M.; Ames, J.A.; Nash, P.J.; Williams, J.D.; Peet, N.P.; Moir, D.T.; et al. New Small Molecule Entry Inhibitors Targeting Hemagglutinin-Mediated Influenza A Virus Fusion. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1447–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Korte, T.; Rachakonda, P.S.; Knapp, E.-W.; Herrmann, A. Energetics of the loop-to-helix transition leading to the coiled-coil structure of influenza virus hemagglutinin HA2 subunits. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2009, 74, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, R.; Barniol-Xicota, M.; Codony, S.; Ginex, T.; Vanderlinden, E.; Montes, M.; Caffrey, M.; Luque, F.J.; Naesens, L.; Vázquez, S. Aniline-Based Inhibitors of Influenza H1N1 Virus Acting on Hemagglutinin-Mediated Fusion. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 98–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, R.U.; Juraszek, J.; Brandenburg, B.; Buyck, C.; Schepens, W.B.G.; Kesteleyn, B.; Stoops, B.; Vreeken, R.J.; Vermond, J.; Goutier, W.; et al. Potent peptidic fusion inhibitors of influenza virus. Science 2017, 358, 496–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekiert, D.C.; Bhabha, G.; Elsliger, M.-A.; Friesen, R.H.E.; Jongeneelen, M.; Throsby, M.; Goudsmit, J.; Wilson, I.A. Antibody Recognition of a Highly Conserved Influenza Virus Epitope. Science 2009, 324, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dongen, M.J.P.; Kadam, R.U.; Juraszek, J.; Lawson, E.; Brandenburg, B.; Schmitz, F.; Schepens, W.B.G.; Stoops, B.; van Diepen, H.A.; Jongeneelen, M.; et al. A small-molecule fusion inhibitor of influenza virus is orally active in mice. Science 2019, 363, eaar6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Angelis, M.; Casciaro, B.; Genovese, A.; Brancaccio, D.; Marcocci, M.E.; Novellino, E.; Carotenuto, A.; Palamara, A.T.; Mangoni, M.L.; Nencioni, L. Temporin g, an amphibian antimicrobial peptide against influenza and parainfluenza respiratory viruses: Insights into biological activity and mechanism of action. FASEB J. 2021, 35, e21358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Y.; Kadam, R.U.; Lee, C.C.D.; Woehl, J.L.; Wu, N.C.; Zhu, X.; Kitamura, S.; Wilson, I.A.; Wolan, D.W. An influenza A hemagglutinin small-molecule fusion inhibitor identified by a new high-throughput fluorescence polarization screen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18431–18438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antanasijevic, A.; Durst, M.A.; Cheng, H.; Gaisina, I.N.; Perez, J.T.; Manicassamy, B.; Rong, L.; Lavie, A.; Caffrey, M. Structure of avian influenza hemagglutinin in complex with a small molecule entry inhibitor. Life Sci. Alliance 2020, 3, e202000724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, A.; Li, Y.; Lv, K.; Gao, R.; Wang, A.; Yan, H.; Qin, X.; Xu, S.; Ma, C.; Jiang, J.; et al. Optimization and SAR research at the piperazine and phenyl rings of JNJ4796 as new anti-influenza A virus agents, part 1. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 222, 113591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elebeedy, D.; Badawy, I.; Elmaaty, A.A.; Saleh, M.M.; Kandeil, A.; Ghanem, A.; Kutkat, O.; Alnajjar, R.; Abd El Maksoud, A.I.; Al-karmalawy, A.A. In vitro and computational insights revealing the potential inhibitory effect of Tanshinone IIA against influenza A virus. Comput. Biol. Med. 2022, 141, 105149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motohashi, Y.; Igarashi, M.; Okamatsu, M.; Noshi, T.; Sakoda, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Ito, K.; Yoshida, R.; Kida, H. Antiviral activity of stachyflin on influenza A viruses of different hemagglutinin subtypes. Virol. J. 2013, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Shernyukov, A.V.; Gatilov, Y.V.; Razumova, Y.V.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Tretiak, T.S.; Pokrovsky, A.G.; Kiselev, O.I.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Discovery of a new class of antiviral compounds: Camphor imine derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 105, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarubaev, V.V.; Pushkina, E.A.; Borisevich, S.S.; Galochkina, A.V.; Garshinina, A.V.; Shtro, A.A.; Egorova, A.A.; Sokolova, A.S.; Khursan, S.L.; Yarovaya, O.I.; et al. Selection of influenza virus resistant to the novel camphor-based antiviral camphecene results in loss of pathogenicity. Virology 2018, 524, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chang, J.C.; Guo, Z.; Carney, P.J.; Shore, D.A.; Donis, R.O.; Cox, N.J.; Villanueva, J.M.; Klimov, A.I.; Stevens, J. Structural Stability of Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Virus Hemagglutinins. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 4828–4838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volobueva, A.S.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Kireeva, M.V.; Borisevich, S.S.; Kovaleva, K.S.; Mainagashev, I.Y.; Gatilov, Y.V.; Ilyina, M.G.; Zarubaev, V.V.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Discovery of New Ginsenol-Like Compounds with High Antiviral Activity. Molecules 2021, 26, 6794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Castro, S.; Ginex, T.; Vanderlinden, E.; Laporte, M.; Stevaert, A.; Cumella, J.; Gago, F.; Camarasa, M.J.; Luque, F.J.; Naesens, L.; et al. N-benzyl 4,4-disubstituted piperidines as a potent class of influenza H1N1 virus inhibitors showing a novel mechanism of hemagglutinin fusion peptide interaction. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 194, 112223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.Y.; Park, S.; Bae, J.-Y.; Heo, J.; Kim, H.-Y.; Woo, S.-H.; Lee, H.U.; Ahn, C.A.; et al. Novel Small Molecule Targeting the Hemagglutinin Stalk of Influenza Viruses. J. Virol. 2019, 93, e00878-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, M.; Ma, C.; Yang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Du, Q.; Yang, C.; Jiang, H.; et al. Discovery of Highly Potent Pinanamine-Based Inhibitors against Amantadine- and Oseltamivir-Resistant Influenza A Viruses. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 61, 5187–5198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, T.; Bidon, M.; Jaimes, J.A.; Whittaker, G.R.; Daniel, S. Coronavirus membrane fusion mechanism offers a potential target for antiviral development. Antivir. Res. 2020, 178, 104792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casalino, L.; Gaieb, Z.; Goldsmith, J.A.; Hjorth, C.K.; Dommer, A.C.; Harbison, A.M.; Fogarty, C.A.; Barros, E.P.; Taylor, B.C.; McLellan, J.S.; et al. Beyond Shielding: The Roles of Glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 2020, 6, 1722–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carino, A.; Moraca, F.; Fiorillo, B.; Marchianò, S.; Sepe, V.; Biagioli, M.; Finamore, C.; Bozza, S.; Francisci, D.; Distrutti, E.; et al. Hijacking SARS-CoV-2/ACE2 receptor interaction by natural and semi-synthetic steroidal agents acting on functional pockets on the receptor binding domain. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 572885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, D.J.; Wrobel, A.G.; Roustan, C.; Borg, A.; Xu, P.; Martin, S.R.; Rosenthal, P.B.; Skehel, J.J.; Gamblin, S.J. The effect of the D614G substitution on the structure of the spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2022586118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.C.; Park, Y.-J.; Tortorici, M.A.; Wall, A.; McGuire, A.T.; Veesler, D. Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantuti-Castelvetri, L.; Ojha, R.; Pedro, L.D.; Djannatian, M.; Franz, J.; Kuivanen, S.; van der Meer, F.; Kallio, K.; Kaya, T.; Anastasina, M.; et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and infectivity. Science 2020, 370, 856–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Z.; Deng, Y.; Lian, J.Q.; Du, P.; Wei, D.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.X.; Gong, L.; et al. CD147-spike protein is a novel route for SARS-CoV-2 infection to host cells. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, S.; Dick, A.; Ju, H.; Mirzaie, S.; Abdi, F.; Cocklin, S.; Zhan, P.; Liu, X. Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 Entry: Current and Future Opportunities. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 63, 12256–12274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

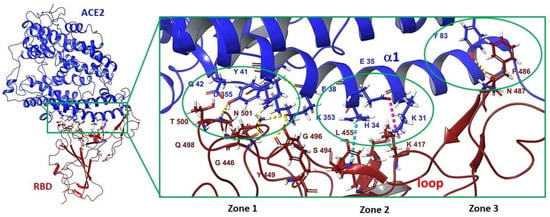

- Yan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 2020, 367, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, J.; Ye, G.; Shi, K.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Aihara, H.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature 2020, 581, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adedeji, A.O.; Severson, W.; Jonsson, C.; Singh, K.; Weiss, S.R.; Sarafianos, S.G. Novel Inhibitors of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus Entry That Act by Three Distinct Mechanisms. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 8017–8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

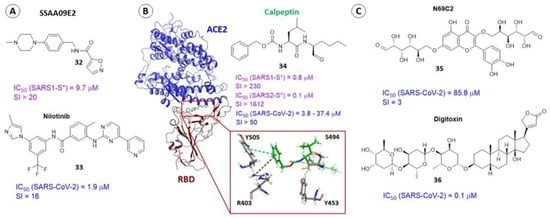

- Razizadeh, M.; Nikfar, M.; Liu, Y. Small molecule therapeutics to destabilize the ACE2-RBD complex: A molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 2793–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagno, V.; Magliocco, G.; Tapparel, C.; Daali, Y. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib inhibits SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2021, 128, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Yadav, S.; Banerjee, S.; Fakayode, S.O.; Parvathareddy, J.; Reichard, W.; Surendranathan, S.; Mahmud, F.; Whatcott, R.; Thammathong, J.; et al. Drug Repurposing to Identify Nilotinib as a Potential SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease Inhibitor: Insights from a Computational and In Vitro Study. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 5469–5483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, S.; Danielli, A. Rapid and sensitive inhibitor screening using magnetically modulated biosensors. Sensors 2021, 21, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deganutti, G.; Prischi, F.; Reynolds, C.A. Supervised molecular dynamics for exploring the druggability of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2021, 35, 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Z.; Liu, C.; Guo, Y.; He, Z.; Huang, X.; Jia, X.; Yang, T. SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV: Virtual screening of potential inhibitors targeting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity (NSP12). J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galimberti, S.; Petrini, M.; Baratè, C.; Ricci, F.; Balducci, S.; Grassi, S.; Guerrini, F.; Ciabatti, E.; Mechelli, S.; Di Paolo, A.; et al. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Play an Antiviral Action in Patients Affected by Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: A Possible Model Supporting Their Use in the Fight Against SARS-CoV-2. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchlarhem, A.; Haddar, L.; Lamzouri, O.; Onci-Es-Saad; Nasri, S.; Aichouni, N.; Bkiyar, H.; Mebrouk, Y.; Skiker, I.; Housni, B. Multiple cranial nerve palsies revealing blast crisis in patient with chronic myeloid leukemia in the accelerated phase under nilotinib during severe infection with SARS-COV-19 virus: Case report and review of literature. Radiol. Case Rep. 2021, 16, 3602–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mediouni, S.; Mou, H.; Otsuka, Y.; Jablonski, J.A.; Adcock, R.S.; Batra, L.; Chung, D.-H.; Rood, C.; de Vera, I.M.S.; Rahaim, R., Jr.; et al. Identification of potent small molecule inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 entry. SLAS Discov. 2022, 27, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lan, J.; Ge, J.; Yu, J.; Shan, S.; Zhou, H.; Fan, S.; Zhang, Q.; Shi, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; et al. Structure of the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature 2020, 581, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalhor, H.; Sadeghi, S.; Abolhasani, H.; Kalhor, R.; Rahimi, H. Repurposing of the approved small molecule drugs in order to inhibit SARS-CoV-2 S protein and human ACE2 interaction through virtual screening approaches. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 40, 1299–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Wang, H.; Wu, X.Q.; Lu, Y.; Guan, S.H.; Dong, F.Q.; Dong, C.L.; Zhu, G.L.; Bao, Y.Z.; Zhang, J.; et al. In Silico Screening of Potential Spike Glycoprotein Inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 with Drug Repurposing Strategy. Chin. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 26, 663–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherfi, S.; Pradines, B.; Devaux, C.; Honore, S.; Colson, P.; La Scola, B.; Raoult, D. Drug repurposing against SARS-CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV. Future Microbiol. 2021, 16, 1341–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

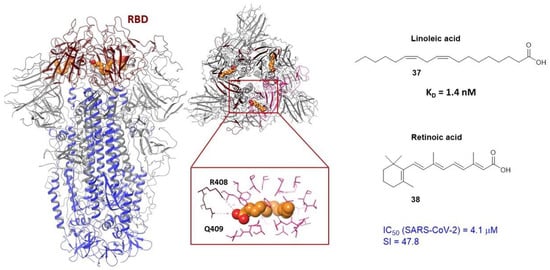

- Toelzer, C.; Gupta, K.; Yadav, S.K.N.; Borucu, U.; Davidson, A.D.; Williamson, M.K.; Shoemark, D.K.; Garzoni, F.; Staufer, O.; Milligan, R.; et al. Free fatty acid binding pocket in the locked structure of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Science 2020, 370, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.; Pye, V.E.; Graham, C.; Muir, L.; Seow, J.; Ng, K.W.; Cook, N.J.; Rees-Spear, C.; Parker, E.; dos Santos, M.S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 can recruit a heme metabolite to evade antibody immunity. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabg7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantini, J.; Di Scala, C.; Chahinian, H.; Yahi, N. Structural and molecular modelling studies reveal a new mechanism of action of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fantini, J.; Chahinian, H.; Yahi, N. Synergistic antiviral effect of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in combination against SARS-CoV-2: What molecular dynamics studies of virus-host interactions reveal. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braz, H.L.B.; de Moraes Silveira, J.A.; Marinho, A.D.; de Moraes, M.E.A.; de Moraes Filho, M.O.; Monteiro, H.S.A.; Jorge, R.J.B. In silico study of azithromycin, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine and their potential mechanisms of action against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colson, P.; Rolain, J.-M.; Lagier, J.-C.; Brouqui, P.; Raoult, D. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine as available weapons to fight COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 55, 105932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, S.; Yan, L.; Xu, W.; Agrawal, A.S.; Algaissi, A.; Tseng, C.-T.K.; Wang, Q.; Du, L.; Tan, W.; Wilson, I.A.; et al. A pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting the HR1 domain of human coronavirus spike. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cao, R.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Hu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W.; Sun, X.; et al. The anti-influenza virus drug, arbidol is an efficient inhibitor of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, L.; Guo, X.; Cao, Y.; Ying, P.; Hong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, G.; Fu, M. Determining available strategies for prevention and therapy: Exploring COVID-19 from the perspective of ACE2 (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 47, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vankadari, N. Arbidol: A potential antiviral drug for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 by blocking trimerization of the spike glycoprotein. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 105998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padhi, A.K.; Seal, A.; Khan, J.M.; Ahamed, M.; Tripathi, T. Unraveling the mechanism of arbidol binding and inhibition of SARS-CoV-2: Insights from atomistic simulations. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2021, 894, 173836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisevich, S.S.; Khamitov, E.M.; Gureev, M.A.; Yarovaya, O.I.; Rudometova, N.B.; Zybkina, A.V.; Mordvinova, E.D.; Shcherbakov, D.N.; Maksyutov, R.A.; Salakhutdinov, N.F. Simulation of Molecular Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 S-Protein in the Presence of Multiple Arbidol Molecules: Interactions and Binding Mode Insights. Viruses 2022, 14, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, T.; Wang, H.; Luan, B. In Silico Exploration of the Molecular Mechanism of Clinically Oriented Drugs for Possibly Inhibiting SARS-CoV-2’s Main Protease. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 4413–4420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemlou, A.; Uskoković, V.; Sefidbakht, Y. Exploration of potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Mpro considering its mutants via structure-based drug design, molecular docking, MD simulations, MM/PBSA, and DFT calculations. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2022, 70, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musarrat, F.; Chouljenko, V.; Dahal, A.; Nabi, R.; Chouljenko, T.; Jois, S.D.; Kousoulas, K.G. The anti-HIV drug nelfinavir mesylate (Viracept) is a potent inhibitor of cell fusion caused by the SARSCoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein warranting further evaluation as an antiviral against COVID-19 infections. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2087–2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]