Abstract

To clarify the predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement in thrombocytopenic chronic hepatitis C (CHC) patients. CHC patients with baseline platelet counts of <150 × 103/μL receiving direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy with at least 12-weeks post-treatment follow-up (PTW12) were enrolled. Significant platelet count improvement was defined as a ≥10% increase in platelet counts at PTW12 from baseline. Platelet count evolution at treatment week 4, end-of-treatment, PTW12, and PTW48 was evaluated. This study included 4922 patients. Sustained virologic response after 12 weeks post-treatment was achieved in 98.7% of patients. Platelet counts from baseline, treatment week 4, and end-of-treatment to PTW12 were 108.8 ± 30.2, 121.9 ± 41.1, 123.1 ± 43.0, and 121.1 ± 40.8 × 103/μL, respectively. Overall, 2230 patients (45.3%) showed significant platelet count improvement. Multivariable analysis revealed that age (odds ratio (OR) = 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.99–1.00, p = 0.01), diabetes mellitus (DM) (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.06–1.38, p = 0.007), cirrhosis (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.58–0.75, p < 0.0001), baseline platelet counts (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99, p < 0.0001), and baseline total bilirubin level (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.71–0.91, p = 0.0003) were independent predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement. Subgroup analyses showed that patients with significant platelet count improvement and sustained virologic responses, regardless of advanced fibrosis, had a significant increase in platelet counts from baseline to treatment week 4, end-of-treatment, PTW12, and PTW48. Young age, presence of DM, absence of cirrhosis, reduced baseline platelet counts, and reduced baseline total bilirubin levels were associated with significant platelet count improvement after DAA therapy in thrombocytopenic CHC patients.

1. Introduction

Thrombocytopenia is a common manifestation of chronic hepatitis C (CHC) infection, with a prevalence of 0.16–45.4% in CHC patients. CHC patients with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis may have severe thrombocytopenia and high rates of thrombocytopenia [1,2]. Increased platelet destruction and decreased platelet production cause thrombocytopenia. The pathophysiology of thrombocytopenia includes splenomegaly-induced hypersplenism, autoimmune responses such as platelet-associated immunoglobulin G against platelet surface antigen, inadequate thrombopoietin (TPO) production due to advanced liver fibrosis, and possible bone marrow suppression by hepatitis C virus (HCV). In the era of interferon (IFN)-based therapy for CHC, achieving a sustained virologic response (SVR) improves platelet counts in patients with advanced liver fibrosis after a long-term follow-up period [3,4]. In patients without SVR, platelet counts decrease [4]. Improvement in platelet counts after a long-term follow-up period is most likely due to the improved liver fibrosis and portal hypertension, further decreasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [4,5,6]. IFN-free direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have been the standard treatment for CHC [7,8,9,10]. Platelet count improvement has also been reported, and could be observed within a short-term follow-up period [11,12,13,14,15]. Liver fibrosis status is less likely to improve rapidly and significantly immediately after initiation of DAA therapy [16]. Rapid or early platelet count improvement may be associated with other factors, such as the aforementioned viral effect [17] or autoimmune responses [11]. In thrombocytopenic CHC patients who will have an elective invasive procedure, DAA treatment might be helpful to improve platelet counts in addition to platelet transfusion alone. Our previous study that enrolled CHC patients receiving DAA therapy revealed that patients without significant platelet count improvement would have more advanced hepatic fibrosis and more liver-related complications such as HCC, splenomegaly, and ascites [15]. However, the sample size of that study was relatively small. After the long-term follow-up period, it remains unclear what pattern the platelet count evolution would follow in these DAA-treated CHC patients. Therefore, we conducted this large-scale study to clarify the predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement and the patterns of platelet count evolution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

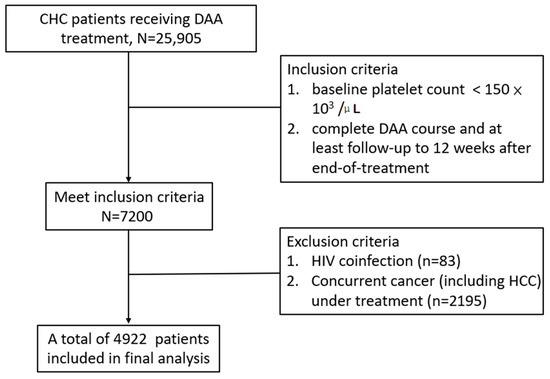

This retrospective study enrolled patients from the Taiwan Association for the Study of Liver (TASL) HCV Registry (TACR). The TACR is a nationwide registry program organized by the TASL, which sets up and manages the database of patients with HCV who receive DAA therapy in Taiwan. From May 2017 to August 2020, 38 study centers were enrolled in the registry. Individual patient records were reviewed, and data were extracted and validated at each participating study center using a standardized case report form and a unified coding dictionary. Inclusion criteria: (1) patients aged >20 years, (2) patients with positive anti-hepatitis C antibody and detectable HCV RNA levels, (3) patients with baseline thrombocytopenia (platelet counts <150 × 103 /μL) [1], and (4) patients with a complete DAA course with at least 12 weeks of post-treatment follow-up (PTW12) after end-of-treatment (EOT). Patients with human immunodeficiency virus coinfection and concurrent cancer (including HCC) receiving treatment were excluded. The treatment duration and regimens were based on the regulations of the Health and Welfare Department of Taiwan and the guidelines [7,8,18]. Among the 25,905 CHC patients registered in the TACR, 4922 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were enrolled in our study (Figure 1). This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of each participating center.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

2.2. Clinical and Laboratory Monitoring

Baseline characteristics, including age, sex, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, history of variceal bleeding, chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection, ascites, history of hepatic encephalopathy, IFN-experienced condition, and chronic kidney disease (CKD), were recorded using chart review. Liver cirrhosis was defined based on any of the following modalities: liver histology; transient elastography (FibroScan®; Echosens, Paris, France) (>12 kPa); acoustic radiation force impulse (>1.98 m/s); fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index (score > 6.5); or the presence of clinical, radiological, endoscopic, or laboratory evidence of cirrhosis and/or portal hypertension [18]. Decompensated cirrhosis was defined as the deterioration of liver function in patients with cirrhosis and was characterized by jaundice (total bilirubin levels >2 mg/dL), variceal bleeding, ascites, or hepatic encephalopathy [19]. HCC was diagnosed either by biopsy or imaging in the setting of liver cirrhosis [20]. SVR was defined as undetectable HCV RNA levels 12 weeks after EOT (PTW12) [21].

Laboratory data (serum platelet, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time with international normalized ratio (PT INR), and creatinine) were assessed at the hepatogastrointestinal outpatient clinic at baseline, EOT, PTW12, and 48 weeks after EOT (PTW48). Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level examination and abdominal ultrasonography were performed at baseline and 3–6 months after initiation of DAA therapy. HCV RNA was quantified at baseline, EOT, and PTW12. Due to variations in platelet counts at different time points of blood tests, we defined significant platelet count improvement as a ≥10% increase in platelet counts from baseline to PTW12 ((platelet counts at PTW12−platelet counts at baseline)/platelet counts at baseline) [13].

2.3. Statistical and Data Analysis

The commercial statistical software package (SAS version 9.4; SPSS, version 20) was used for all statistical analyses. Frequency was compared between groups with and without significant platelet count improvement using the X2 test with Yate’s correction or Fisher’s exact test. Group mean values (presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD)) were compared using Student’s t-test or the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test when appropriate. Stepwise logistic regression analysis using the bidirectional elimination method was performed to determine factors associated with significant platelet count improvement by analyzing the covariates in the single variable analysis (p < 0.1), with gender adjusted at the same time. A collinear test was used to determine whether the independent factors were highly correlated. All statistical analyses were based on two-sided hypothesis tests with a significance level of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics of CHC Patients

A total of 4922 patients who completed their follow-up at PTW12 were included in the final analysis. The baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Overall, 2030 patients (41.2%) were men, and the mean age of patients was 65.0 ± 10.7 years. In this cohort, 1245 patients had DM (25.3%), 2051 had cirrhosis (41.7%), 270 had decompensated cirrhosis (5.5%), 361 had HBV coinfection (7.3%), and 4859 achieved SVR12 (98.7%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the thrombocytopenic HCV patients with or without significant platelet count improvement after DAA therapy.

3.2. Platelet Count Evolution from Baseline to 48 Weeks after EOT (PTW48)

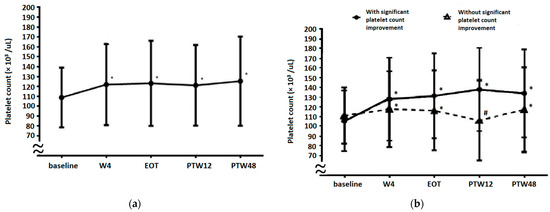

As shown in Figure 2a, the platelet counts from baseline to treatment week 4 (W4), EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 108.6 ± 30.1, 122.4 ± 41.0, 123.2 ± 43.0, 120.6 ± 40.2, and 124.4 ± 45.0 × 103/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). An increase in platelet counts was noted during the treatment and follow-up periods. We performed a subgroup analysis to investigate further whether platelet count improvement occurred before W4. Among the studied cohort, 243 patients had their platelet counts evaluated at W1, W2, and W4. Platelet counts at baseline, W1, W2, and W4 were 106.5 ± 30.7, 119.3 ± 37.2, 117.9 ± 36.7, and 121.4 ± 38.5 × 103/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W1 vs. baseline, W2 vs. baseline, and W4 vs. baseline). An increase in platelet counts occurred as early as week one after the initiation of DAA therapy.

Figure 2.

The dynamic changes in platelet counts from baseline to W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 in (a) the overall cohort and (b) patients with and without significant platelet count improvement. * Platelet counts are significantly increased when compared with baseline levels. # Platelet counts are significantly decreased compared with baseline levels (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). W4, week 4; EOT, end-of-treatment; PTW12, 12 weeks post-treatment follow-up; PTW48, 48 weeks post-treatment follow-up.

3.3. Factors Associated with Significant Platelet Count Improvement

Significant platelet count improvement was observed in 2230 (45.3%) patients with thrombocytopenic CHC who were receiving DAA therapy. Table 1 shows that between patients with and without significant platelet count improvement, age (64.6 ± 10.7 vs. 65.3 ± 10.6 years), DM (n = 598 (26.8%) vs. n = 647 (24.0%)), cirrhosis (n = 849 (38.1%) vs. n = 1202 (44.7%)), decompensated cirrhosis (n = 100 (4.5%) vs. n = 170 (6.3%)), ascites (n = 55 (2.5%) vs. n = 104 (3.9%)), baseline platelet counts (105.7 ± 31.3 vs. 111.4 ± 28.6 × 103/μL), baseline total bilirubin level (0.96 ± 0.52 vs. 1.01 ± 0.56 mg/dL), and baseline creatinine level (1.24 ± 1.78 vs. 1.13 ± 1.47 mg/dL) were associated with significant platelet count improvement after single variable analysis. Multivariable analysis (Table 2) revealed that age (odds ratio (OR) = 0.99, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.99–1.00, p = 0.01), DM (OR = 1.20, 95% CI: 1.06–1.38, p = 0.007), cirrhosis (OR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.58–0.75, p < 0.0001), baseline platelet counts (OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.98–0.99, p < 0.0001), and baseline total bilirubin level (OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.71–0.91, p = 0.0003) were independent predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement, indicating that younger age, presence of DM, absence of cirrhosis, reduced baseline platelet counts, or reduced baseline total bilirubin level are associated with significant platelet count improvement after DAA therapy.

Table 2.

Single variable and multivariable analyses associated with significant platelet count improvement in thrombocytopenic HCV patients after DAA therapy.

3.4. Platelet Count Evolution in Patients with or without Significant Platelet Count Improvement

Platelet count evolution results based on significant platelet count improvement are presented in Figure 2b. In patients with significant platelet count improvement, the platelet counts at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 105.6 ± 31.2, 128.2 ± 42.8, 131.6 ± 43.7, 138.0 ± 42.7, and 134.0 ± 45.1 × 103/µL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). In patients without significant platelet count improvement, platelet counts at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 111.2 ± 28.9, 117.8 ± 38.92, 116.4 ± 41.2, 106.4 ± 31.7, and 117.3 ± 43.7 × 103/µL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). Furthermore, platelet counts between patients with and without significant platelet count improvement were significantly different at baseline (p < 0.001), W4 (p < 0.001), EOT (p < 0.001), PTW12 (p < 0.001), and PTW48 (p < 0.001).

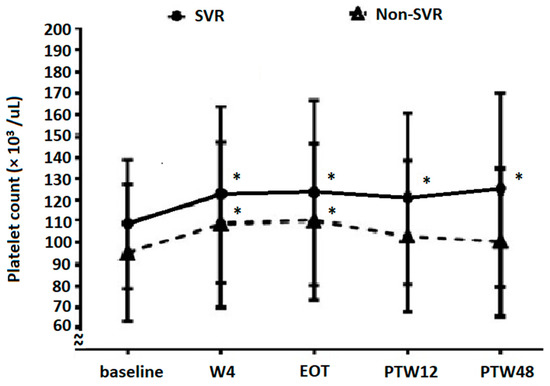

3.5. Platelet Count Evolution Based on DAA Treatment Response

Only 45 patients (1.2%) with platelet counts examined at EOT and PTW12 did not achieve SVR. Platelet count evolution based on the DAA treatment response is reported in Figure 3. Platelet counts in patients without SVR at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 95.0 ± 31.8, 108.7 ± 38.9, 110.2 ± 36.9, 103.1 ± 35.4, and 100.4 ± 34.8 × 103/µL, respectively (W4 vs. baseline, p < 0.05; EOT vs. baseline, p = 0.003; PTW12 vs. baseline, p = 0.115; and PTW48 vs. baseline, p = 0.290). After DAA treatment, non-SVR patients showed a significant increase in platelet counts until EOT, but this increase became insignificant at and after PTW12. In contrast, platelet counts in SVR patients at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 108.8 ± 30.1, 122.6 ± 41.1, 123.4 ± 43.0, 120.9 ± 40.2, and 124.9 ± 45.1 × 103/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). Furthermore, platelet counts between non-SVR and SVR patients were significantly different at baseline (p = 0.006), W4 (p = 0.030), EOT (p = 0.021), PTW12 (p = 0.002), and PTW48 (p = 0.004).

Figure 3.

The evolution of platelet counts in patients with SVR12 and without SVR12. * Platelet counts are significantly increased compared with baseline levels (in SVR patients, p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline; in non-SVR patients, W4 vs. baseline, p < 0.05; EOT vs. baseline, p = 0.003; PTW12 vs. baseline, p = 0.115; and PTW48 vs. baseline, p = 0.290). W4, week 4; EOT, end-of-treatment; PTW12, 12 weeks post-treatment follow-up; PTW48, 48 weeks post-treatment follow-up.

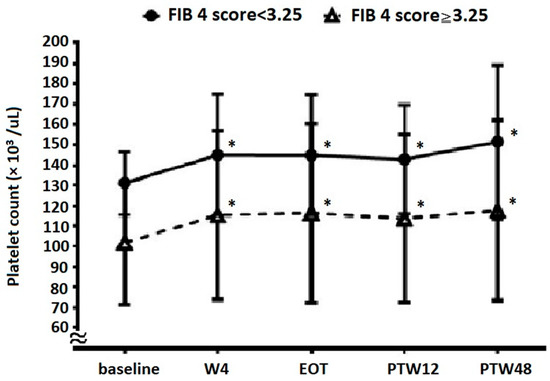

3.6. Platelet Count Evolution Based on Baseline Fibrosis Status

A total of 2782 (76.2%) patients with platelet counts examined at EOT and PTW12 had advanced fibrosis according to FIB-4 scores (cutoff value, 3.25). Platelet count evolution results based on fibrosis status are shown in Figure 4. In patients with non-advanced fibrosis, platelet counts at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 131.1 ± 15.5, 145.1 ± 29.7, 145.0 ± 29.5, 142.9 ± 26.9, and 151.4 ± 37.9 × 103/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). In patients with advanced fibrosis, platelet counts at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 were 101.7 ± 30.1, 115.4 ± 41.4, 116.4 ± 44.1, 113.7 ± 41.2, and 117.8 ± 44.3 × 103/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). Patients showed a significant increase in platelet counts at W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 compared with those at baseline, regardless of the fibrosis status. Furthermore, platelet counts between the non-advanced and advanced fibrosis groups were significantly different at baseline (p < 0.001), W4 (p < 0.001), EOT (p < 0.001), PTW12 (p < 0.001), and PTW48 (p < 0.001).

Figure 4.

The evolution of platelet count in patients with and without advanced liver fibrosis. * Platelet counts are significantly increased compared with baseline levels (p < 0.001 for W4 vs. baseline, EOT vs. baseline, PTW12 vs. baseline, and PTW48 vs. baseline). W4, week 4; EOT, end-of-treatment; PTW12, 12 weeks post-treatment follow-up; PTW48, 48 weeks post-treatment follow-up.

4. Discussion

In this study, overall platelet counts in thrombocytopenic CHC patients improved after DAA therapy. The predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement included younger age, presence of DM, absence of cirrhosis, reduced baseline platelet counts, and reduced baseline total bilirubin levels. Besides, significantly improved platelet counts are noted as early as one week after the initiation of DAA therapy. Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with significant platelet count improvement would consistently improve from baseline to PTW48. SVR patients showed a significant increase in platelet counts from baseline to PTW48. However, non-SVR patients showed a significant increase until EOT, and the changes became insignificant at and after PTW12 compared with the baseline. Patients would have a significant increase in platelet counts from baseline to PTW48 after DAA therapy, regardless of the fibrosis status.

Platelet counts can improve immediately after DAA treatment in CHC patients [11,12,13,14,15]. Some of these studies did not investigate the predictive factors of significant platelet count improvement. Besides, our previous studies only showed that the fatty liver, baseline platelet counts, and baseline thrombopoietin level were related to significant platelet count improvement [13,15]. In this larger-scale study, we found that age, baseline platelet counts, baseline total bilirubin levels, and cirrhosis were negatively correlated, but the presence of DM was positively correlated with significant platelet count improvement (Table 2). Several mechanisms may account for these improvements after HCV eradication. Platelet count improvement is more likely to be related to a decrease in HCV-induced platelet-associated immunoglobulin G levels [11], improvement of hypersplenism [14], and resolution of HCV-related myelosuppression [14,22]. Older age, higher total bilirubin levels, and the presence of cirrhosis at baseline are associated with more severe liver fibrosis, which is related to the poorer liver capacity to produce TPO [23], and splenomegaly may be more prevalent in them [24]. Reduced serum TPO levels and splenomegaly-related hypersplenism could partly account for the absence of significant platelet count improvement even after DAA therapy. DM was positively associated with significant platelet count improvement. Metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance are associated with elevated platelet counts [25,26], and may partly account for the role of DM in platelet count improvement. This does not mean metabolic syndrome is beneficial because it involves chronic inflammation state and cardiovascular disease [27]. Our previous study found that fatty liver is associated with significant platelet count improvement [13]. Fatty liver is related to metabolic syndrome [28]. However, a study showed no correlation between hyperglycemia and platelet count [29]. In the present study, fatty liver could not be known from primary data. Therefore, we could not evaluate the relationship between DM and fatty liver. Hence, further studies are required to explore the underlying mechanism.

Platelet count improvement was observed at W4 (Figure 2a). After subgroup analysis, we further found that a significant increase in platelet counts would begin just one week after initiation of DAA treatment. HCV RNA levels decreased significantly from baseline to W4 (log HCV RNA, baseline 5.90 ± 0.97 IU/mL, W4 1.23 ± 0.27 IU/mL, p < 0.05), which is compatible with previous studies [30,31,32]. Besides, HCV RNA levels significantly decreased within 1–2 weeks after DAA therapy initiation and were even undetectable at EOT, independent of the presence or absence of SVR12 [32]. Hence, this phenomenon suggests that the HCV-induced decrease in platelet counts is ameliorated within several weeks of HCV eradication by DAAs. To determine whether significant platelet count improvement could be observed after a long-term follow-up period (at PTW48), we analyzed changes in platelet counts from baseline to PTW48 between patients with and without significant platelet count improvement (Figure 2b). We found that platelet counts in both subgroups increased before EOT, but this increase only continued in patients with significant platelet count improvement. This indicates that significant platelet count improvement (at PTW12) predicts a similar improvement at PTW48. In patients without significant platelet count improvement, platelet counts decreased at PTW12 through an unknown mechanism, but increased again at PTW48 compared with baseline levels. We also demonstrated the importance of SVR in patients with thrombocytopenic CHC (Figure 3). Patients who achieved SVR had a significant increase in platelet counts from baseline to PTW48, whereas the platelet counts of those without SVR increased significantly at EOT, but the change was insignificant at PTW12 and PTW48 compared with baseline levels. This phenomenon may be explained by the reappearance of HCV after EOT in patients without SVR.

Non-advanced fibrosis patients (FIB-4 score < 3.25) had significantly higher platelet counts at baseline, W4, EOT, PTW12, and PTW48 than advanced fibrosis patients (FIB-4 score ≥ 3.25). Still, both these subgroups would have significantly improved platelet counts at time points after initiation of DAA treatment. This finding is similar to that reported by another study [12], wherein significantly increased platelet counts were noted in CHC patients with HCV elimination, regardless of the presence of cirrhosis. This phenomenon reminds us not to interpret early platelet count improvement as a short-term improvement in liver fibrosis.

This study has some limitations. Using large-scale data of the TACR, two important factors—fatty liver and splenomegaly—could not be analyzed. However, this big data still provided some important results. For example, total bilirubin was negatively associated with significant platelet count improvement in this study. Still, this association was not observed in our previous study, possibly due to the small sample size [13]. Second, a serial evaluation of spleen size, the severity of liver fibrosis, or TPO levels were not performed in many patients in our study. Hence, we are unsure whether platelet count improvement at long-term follow-up time points is related to fibrosis improvement alone. Third, platelet counts improved progressively from baseline to PTW12 and PTW48. Whether such progress reaches a plateau after PTW12 should be clarified in future studies with an even longer-term follow-up period (such as data at PTW96 and PTW144). Fourth, we did not check all patients’ resistance-associated substitutions (RAS). RAS is significantly associated with advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis [33]. Cirrhosis is a negative factor predicting significant platelet count improvement in our study. Therefore, we could not know whether there exists any correlation between them or not.

5. Conclusions

Thrombocytopenic CHC patients treated with DAAs generally had a significant increase in platelet counts. Younger age, presence of DM, absence of cirrhosis, and reduced baseline platelet counts and total bilirubin levels can predict significant platelet count improvement. Patients with significant platelet count improvement show persistent improvement at PTW48. The absence of SVR negatively affected platelet count improvement. Regardless of liver fibrosis, patients would have improved platelet counts after DAA treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-C.C. and T.-S.C.; data curation, C.-H.C., P.-N.C., C.-C.L., L.-R.M., C.-T.C., C.-F.H., H.-T.K., Y.-H.H., C.-M.T., C.-Y.P., M.-J.B., M.-L.Y. (Ming-Lun Yeh), C.-L.L. (Chih-Lang Lin), C.-Y.L., P.-L.L., L.-W.C., C.-H.H., J.-F.H., C.-C.Y., J.-T.H., C.-W.L., C.-C.W., W.-W.S., T.-Y.H., C.-L.L. (Chih-Lin Lin), W.-L.T., T.-H.L., G.-Y.C., S.-J.W., C.-C.C., S.-S.Y., W.-C.W., C.-S.H., C.-K.H., C.-N.K., P.-C.T., C.-H.L., M.-H.L., C.-Y.D., J.-H.K., W.-L.C., H.-C.L., C.-Y.C. and K.-C.T.; funding acquisition, M.-L.Y. (Ming-Lung Yu); methodology, K.-C.T.; resources, M.-L.Y. (Ming-Lung Yu); supervision, K.-C.T. and M.-L.Y. (Ming-Lung Yu); writing–original draft, Y.-C.C.; writing–review and editing, T.-S.C.; critical review and approval of the manuscript: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study is supported by grants of TASL and TASLF, and partly funded by Kaohsiung Medical University with plans: KMU-DK(B)110002; Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant, Center for Liquid Biopsy and Cohort Research: KMU-TC109B05; Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant, Center for Cancer Research: KMU-TC109A04; Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital: KMUH110-0R06, KMUH-DK(C)109002, KMUH-DK(C)110011, KMUH-DK(C)111006, KMUH-DK(C)110004, KMUH-DK(C)111004. The sponsors played no role in the study design, the interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dalin Tzu Chi Hospital (approval number B11002024) and each study site.

Informed Consent Statement

All patients provided written informed consent before enrollment.

Data Availability Statement

All the data were obtained upon the request to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Taiwan Association for the Study of Liver (TASL) and the Taiwan Association for the Study of the Liver Foundation (TASLF) for grant support and the TACR study group for data collection. We also thank the Center for Medical Informatics and Statistics of Kaohsiung Medical University for providing administrative and funding support.

Conflicts of Interest

Ming-Lung Yu has received research support from Abbott, BMS, Gilead, and Merck; served as a consultant of Abbvie, Abbott, Ascletis, BMS, Gilead, Merck, and Roche; served as a speaker of Abbvie, Abbott, BMS, Gilead, Merck, and IPSEN. Chia-Yen Dai has served as a consultant of Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, Merck, Pharmaessential; served as a speaker of Abbvie, BMS, Gilead, Merck, Pharmaessential. Wan-Long Chuang: Consultation: Gilead, AbbVie, BMS, PharmaEssentia. Speaker: Gilead, AbbVie, BMS, PharmaEssentia. All other authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Louie, K.S.; Micallef, J.M.; Pimenta, J.M.; Forssen, U.M. Prevalence of thrombocytopenia among patients with chronic hepatitis C: A systematic review. J. Viral Hepat. 2011, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.-Y.; Ho, C.-K.; Huang, J.-F.; Hsieh, M.-Y.; Hou, N.-J.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Wang, L.-Y.; Chang, W.-Y.; Yu, M.-L.; et al. Hepatitis C virus viremia and low platelet count: A study in a hepatitis B & C endemic area in Taiwan. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruoka, D.; Imazeki, F.; Arai, M.; Kanda, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Yokosuka, O. Longitudinal changes of the laboratory data of chronic hepatitis C patients with sustained virological response on long-term follow-up. J. Viral Hepat. 2012, 19, e97–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Meer, A.J.; Maan, R.; Veldt, B.J.; Feld, J.J.; Wedemeyer, H.; Dufour, J.-F.; Lammert, F.; Duarte-Rojo, A.; Manns, M.P.; Zeuzem, S.; et al. Improvement of platelets after SVR among patients with chronic HCV infection and advanced hepatic fibrosis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 31, 1168–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, K.-M.; Wang, J.-H.; Hung, C.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Lee, C.-M.; Lu, S.-N. Improvement of thrombocytopenia in hepatitis C-related advanced fibrosis patients after sustained virological response. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2013, 58, 556–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, M.-L.; Huang, C.-I.; Huang, C.-F.; Hsieh, M.-H.; Hsieh, M.-Y.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Huang, J.-F.; Kuo, P.-L.; Kuo, H.-T.; et al. Post-treatment alpha fetoprotein and platelets predict hepatocellular carcinoma development in dual-infected hepatitis B and C patients after eradication of hepatitis C. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12240–12249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pawlotsky, J.M.; Negro, F.; Aghemo, A.; Berenguer, M.; Dalgard, O.; Dusheiko, G.; Marra, F.; Puoti, M.; Wedemeyer, H.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: Final update of the series. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1170–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghany, M.G.; Morgan, T.R.; AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2019 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology 2020, 71, 686–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-L.; Chen, P.-J.; Dai, C.-Y.; Hu, T.-H.; Huang, C.-F.; Huang, Y.-H.; Hung, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Liu, C.-J.; et al. Taiwan consensus statement on the management of hepatitis C: Part (I) general population. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1019–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-L.; Chen, P.-J.; Dai, C.-Y.; Hu, T.-H.; Huang, C.-F.; Huang, Y.-H.; Hung, C.-H.; Lin, C.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Liu, C.-J.; et al. Taiwan consensus statement on the management of hepatitis C: Part (II) special populations. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2020, 119, 1135–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honma, Y.; Shibata, M.; Hayashi, T.; Kusanaga, M.; Ogino, N.; Minami, S.; Kumei, S.; Oe, S.; Miyagawa, K.; Senju, M.; et al. Effect of direct-acting antivirals on platelet-associated immunoglobulin G and thrombocytopenia in hepatitis C virus-related chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 1641–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyar, M.; Saidi, M.; Zapatka, S.; Deng, Y.; Ciarleglio, M.; Garcia-Tsao, G. Platelet count increases after viral elimination in chronic HCV, independent of the presence or absence of cirrhosis. Liver Int. 2019, 39, 2061–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Tseng, C.W.; Tseng, K.C. Rapid platelet count improvement in chronic hepatitis C patients with thrombocytopenia receiving direct-acting antiviral agents. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e20156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizu, Y.; Ishigami, M.; Hayashi, K.; Honda, T.; Kuzuya, T.; Ito, T.; Fujishiro, M. Rapid increase of platelet counts during antiviral therapy in patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatol. Res. 2020, 50, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Ko, P.H.; Lee, C.C.; Tseng, C.W.; Tseng, K.C. Baseline thrombopoietin level is associated with platelet count improvement in thrombocytopenic chronic hepatitis C patients after successful direct-acting antiviral agent therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvaruso, V.; Craxi, A. Hepatic benefits of HCV cure. J. Hepatol. 2020, 73, 1548–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.-F.; Yeh, M.-L.; Huang, C.-I.; Lin, Z.-Y.; Chen, S.-C.; Dai, C.-Y.; Huang, J.-F.; Yu, M.-L. Interference of hepatitis B virus dual infection in platelet count recovery in chronic hepatitis C patients with curative antiviral therapy. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 33, 1108–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Huang, C.; Cheng, P.; Tseng, K.; Lo, C.; Kuo, H.; Huang, Y.; Tai, C.; Peng, C.; Bair, M.; et al. Factors associated with treatment failure of direct-acting antivirals for chronic hepatitis C: A real-world nationwide hepatitis C virus registry programme in Taiwan. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, G.; Morabito, A.; D’Amico, M.; Pasta, L.; Malizia, G.; Rebora, P.; Valsecchi, M.G. New concepts on the clinical course and stratification of compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. Hepatol. Int. 2018, 12, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlotsky, J.-M.; Negro, F.; Aghemo, A.; Berenguer, M.; Dalgard, O.; Dusheiko, G.; Marra, F.; Puoti, M.; Wedemeyer, H. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 461–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peck-Radosavljevic, M. Thrombocytopenia in chronic liver disease. Liver Int. 2017, 37, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannini, E.; Borro, P.; Botta, F.; Fumagalli, A.; Malfatti, F.; Podestà, E.; Romagnoli, P.; Testa, E.; Chiarbonello, B.; Polegato, S.; et al. Serum thrombopoietin levels are linked to liver function in untreated patients with hepatitis C virus-related chronic hepatitis. J. Hepatol. 2002, 37, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, M.; Merkel, C.; Sacerdoti, D.; Nava, V.; Gatta, A. Role of spleen enlargement in cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Dig. Liver Dis. 2002, 34, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesri, A.; Okonofua, E.C.; Egan, B.M. Platelet and white blood cell counts are elevated in patients with the metabolic syndrome. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2005, 7, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.M.; Lee, J.W.; Shim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.J. Relationship Between Platelet Count and Insulin Resistance in Korean Adolescents: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Metab. Syndr. Relat. Disord. 2018, 16, 470–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, E.; Fuentes, F.; Vilahur, G.; Badimon, L.; Palomo, I. Mechanisms of chronic state of inflammation as mediators that link obese adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome. Med. Inflamm. 2013, 2013, 136584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Bugianesi, E.; Forlani, G.; Cerrelli, F.; Lenzi, M.; Manini, R.; Natale, S.; Vanni, E.; Villanova, N.; Melchionda, N.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver, steatohepatitis, and the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology 2003, 37, 917–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatta, S.; Singh, S.; Gautam, S.; Osti, B.P. Mean Platelet Volume and Platelet Count in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Impaired Fasting Glucose. J. Nepal. Health Res. Counc. 2019, 16, 392–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poordad, F.; Dieterich, D. Treating hepatitis C: Current standard of care and emerging direct-acting antiviral agents. J. Viral Hepat. 2012, 19, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghemo, A.; Degasperi, E.; De Nicola, S.; Bono, P.; Orlandi, A.; D’Ambrosio, R.; Soffredini, R.; Perbellini, R.; Lunghi, G.; Colombo, M. Quantification of Core Antigen Monitors Efficacy of Direct-acting Antiviral Agents in Patients With Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 14, 1331–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perpiñán, E.; Caro-Pérez, N.; García-González, N.; Gregori, J.; González, P.; Bartres, C.; Soria, M.E.; Perales, C.; Lens, S.; Mariño, Z.; et al. Hepatitis C virus early kinetics and resistance-associated substitution dynamics during antiviral therapy with direct-acting antivirals. J. Viral Hepat. 2018, 25, 1515–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Stefano, M.; Faleo, G.; Mohamed, A.M.F.; Morella, S.; Bruno, S.R.; Tundo, P.; Fiore, J.R.; Santantonio, T.A. Resistance Associated Mutations in HCV Patients Failing DAA Treatment. New Microbiol. 2021, 44, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).